The Impact of Firefighters’ Emotional Labor on Job Performance: The Moderating Effects of Transactional and Transformational Leadership

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. The Impact of Emotional Labor on Job Performance

2.2. Moderating Effects of Transactional and Transformational Leadership

3. Model Specification

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Data Sources and Sample

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. Dependent Variable

3.3.2. Independent Variables

3.3.3. Moderating Variables

3.3.4. Controls

3.4. Measurement Reliability and Validity

4. Findings

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

5.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Igboanugo, S.; Bigelow, P.L.; Mielke, J.G. Health Outcomes of Psychosocial Stress within Firefighters: A Systematic Review of the Research Landscape. J. Occup. Health 2021, 63, e12219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.D.; Dyal, M.-A.; DeJoy, D.M. Firefighter Stress, Anxiety, and Diminished Compliance-Oriented Safety Behaviors: Consequences of Passive Safety Leadership in the Fire Service? Fire 2023, 6, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verble, R.; Granberg, R.; Pearson, S.; Rogers, C.; Watson, R. Mental Health and Traumatic Occupational Exposure in Wildland Fire Dispatchers. Fire 2024, 7, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.D.; An, Y.S.; Kim, D.H.; Jeong, K.S.; Ahn, Y.S. An Overview of Compensated Work-Related Injuries among Korean Firefighters from 2010 to 2015. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 30, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Byun, H.; Kang, T. Firefighters’ Exposures to Polynuclear Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Volatile Organic Compounds by Tasks in Some Fire Scenes in Korea. J. Korean Soc. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2019, 29, 477–487. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, K.M. Reexamining Fire Emergency Management in Korea. Int. J. Bus. Contin. Risk Manag. 2020, 10, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Lee, D.; Kim, J.; Jeon, K.; Sim, M. Duty-Related Trauma Exposure and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in Professional Firefighters. J. Trauma. Stress 2017, 30, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, M.; Im, M. Firefighters’ Perceptions of Psychological Intervention Programs in South Korea during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Korean Acad. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 31, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, I.-K.; Lee, H.S.; Song, K.; Ahmed, O.; Lee, D.; Kim, J.; Cho, E.; Jang, S.; Kim, J.-H.; Chung, S. Assessing Stress and Anxiety in Firefighters during the Coronavirus Disease-2019 Pandemic: A Comparative Adaptation of the Stress and Anxiety in the Viral Epidemic–9 Items and Stress and Anxiety in the Viral Epidemics–6 Items Scales. Psychiatry Investig. 2023, 20, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Kwon, K.T.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.-W.; Chang, H.-H.; Kim, Y.; Bae, S.; Cheong, H.S.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, B. Correlates of Burnout among Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic in South Korea. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hasselt, V.B.; Bourke, M.L.; Schuhmann, B.B. Firefighter Stress and Mental Health: Introduction to the Special Issue. Behav. Modif. 2022, 46, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandey, A.A. Emotional Regulation in the Workplace: A New Way to Conceptualize Emotional Labor. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülsheger, U.R.; Schewe, A.F. On the Costs and Benefits of Emotional Labor: A Meta-Analysis of Three Decades of Research. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 361–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources: A New Attempt at Conceptualizing Stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B.; Neveu, J.-P.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Westman, M. Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the Role of Resources in Conservation of Resources Theory. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, G.; Bentley, M.A.; Eggerichs-Purcell, J. Testing the Impact of Emotional Labor on Work Exhaustion for Three Distinct Emergency Medical Service (EMS) Samples. Career Dev. Int. 2012, 17, 626–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Moon, K.-K. The Effect of Emotional Labor on Psychological Well-Being in the Context of South Korean Firefighters: The Moderating Role of Transformational Leadership. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alabak, M.; Hülsheger, U.R.; Zijlstra, F.R.; Verduyn, P. More than One Strategy: A Closer Examination of the Relationship between Deep Acting and Key Employee Outcomes. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seery, B.L.; Corrigall, E.A. Emotional Labor: Links to Work Attitudes and Emotional Exhaustion. J. Manag. Psychol. 2009, 24, 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.-Y.; Hur, W.-M.; Kim, M. The Relationship of Coworker Incivility to Job Performance and the Moderating Role of Self-Efficacy and Compassion at Work: The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) Approach. J. Bus. Psychol. 2017, 32, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletzer, J.L.; Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.B. Constructive and Destructive Leadership in Job Demands-Resources Theory: A Meta-Analytic Test of the Motivational and Health-Impairment Pathways. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 14, 131–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.B. Daily Job Demands and Employee Work Engagement: The Role of Daily Transformational Leadership Behavior. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katou, A.A.; Koupkas, M.; Triantafillidou, E. Job Demands-Resources Model, Transformational Leadership and Organizational Performance: A Multilevel Study. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2022, 71, 2704–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, A.J.; Biggs, A.; Hegerty, E. Work Engagement: Investigating the Role of Transformational Leadership, Job Resources, and Recovery. J. Psychol. 2017, 151, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochschild, A.R. The Managed Heart. In Working in America; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1983; pp. 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Humphrey, R.H. Emotional Labor in Service Roles: The Influence of Identity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1993, 18, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.A.; Feldman, D.C. The Dimensions, Antecedents, and Consequences of Emotional Labor. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 986–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Wang, W.; Huang, S.; Li, H. Psychological Capital, Emotional Labor and Exhaustion: Examining Mediating and Moderating Models. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 37, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvey, R.W.; Renz, G.L.; Watson, T.W. Emotionality and Job Performance: Implications for Personnel Selection. Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1998, 16, 103–147. [Google Scholar]

- Grandey, A.A. When “the Show Must Go on”: Surface Acting and Deep Acting as Determinants of Emotional Exhaustion and Peer-Rated Service Delivery. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.K.; Walter, F.; Lawrence, S.A. Emotion Suppression and Perceptions of Interpersonal Citizenship Behavior: Faking in Good Faith or Bad Faith? J. Organ. Behav. 2021, 42, 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, F.; Anwar, M.M.; Bashir, T.; Qurrahtulain, K.; Iqbal, Z. Performing in Bank Means Performing Emotional Labor: A Case of Front-Line Female Service Providers in Public Sector Banks. J. Public Aff. 2022, 22, e2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauman, S.; Malik, S.Z.; Saleem, F.; Ashraf Elahi, S. How Emotional Labor Harms Employee’s Performance: Unleashing the Missing Links through Anxiety, Quality of Work-Life and Islamic Work Ethic. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 35, 2131–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Groth, M.; Johnson, A. When the Going Gets Tough, the Tough Keep Working: Impact of Emotional Labor on Absenteeism. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 615–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ok, C.M. Understanding Hotel Employees’ Service Sabotage: Emotional Labor Perspective Based on Conservation of Resources Theory. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotheridge, C.M.; Lee, R.T. Testing a Conservation of Resources Model of the Dynamics of Emotional Labor. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2002, 7, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liao, H.; Zhan, Y.; Shi, J. Daily Customer Mistreatment and Employee Sabotage Against Customers: Examining Emotion and Resource Perspectives. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 312–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Guy, M.E. Emotional Labor, Performance Goal Orientation, and Burnout from the Perspective of Conservation of Resources: A United States/China Comparison. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2019, 42, 685–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, N.S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Ziwei, Y. The Impact of Surface and Deep Acting on Employee Creativity. Creat. Res. J. 2020, 32, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chen, Y.-C.; Umstattd Meyer, M.R. A Moderated Mediation Model of Emotional Labor and Service Performance: Examining the Role of Work–Family Interface and Physically Active Leisure. Hum. Perform. 2020, 33, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation: Affective, Cognitive, and Social Consequences. Psychophysiology 2002, 39, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-J. Managing Emotional Labor for Service Quality: A Cross-Level Analysis among Hotel Employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uy, M.A.; Lin, K.J.; Ilies, R. Is It Better to Give or Receive? The Role of Help in Buffering the Depleting Effects of Surface Acting. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 1442–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L.S.; Grandey, A.A. Display Rules versus Display Autonomy: Emotion Regulation, Emotional Exhaustion, and Task Performance in a Call Center Simulation. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Hur, W.-M.; Moon, T.-W.; Jun, J.-K. Is All Support Equal? The Moderating Effects of Supervisor, Coworker, and Organizational Support on the Link between Emotional Labor and Job Performance. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2017, 20, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gelderen, B.R.; Konijn, E.A.; Bakker, A.B. Emotional Labor among Police Officers: A Diary Study Relating Strain, Emotional Labor, and Service Performance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 852–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sun, H.; Lam, W.; Hu, Q.; Huo, Y.; Zhong, J.A. Chinese Hotel Employees in the Smiling Masks: Roles of Job Satisfaction, Burnout, and Supervisory Support in Relationships between Emotional Labor and Performance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 826–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenhall, R.H.; Langfield-Smith, K. The Relationship between Strategic Priorities, Management Techniques and Management Accounting: An Empirical Investigation Using a Systems Approach—ScienceDirect. Account. Organ. Soc. 1998, 23, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, J.M.; Martínez, I.; Munduate, L.; Medina, F.J. A Contingency Perspective on the Study of the Consequences of Conflict Types: The Role of Organizational Culture. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2005, 14, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, N.-W.; Wang, I.-A. The Relationship between Newcomers’ Emotional Labor and Service Performance: The Moderating Roles of Service Training and Mentoring Functions. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 2729–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, S.-C.J.; Chen, S.-H.S.; Yuan, K.-S.; Chou, W.; Wan, T.T.H. Emotional Labor in Health Care: The Moderating Roles of Personality and the Mediating Role of Sleep on Job Performance and Satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 574898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Huang, S.; Yin, H.; Ke, Z. Employees’ Emotional Labor and Emotional Exhaustion: Trust and Gender as Moderators. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2018, 46, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, N.; Chao, R.-F. How Emotional Labor Affects Job Performance in Hospitality Employees: The Moderation of Emotional Intelligence. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansfield, J. Confidence, Competence and Commitment: Public Health England’s Leadership and Workforce Development Framework for Public Mental Health. J. Public Ment. Health 2015, 14, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Is There Universality in the Full Range Model of Leadership? Int. J. Public Adm. 1996, 19, 731–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northouse, P.G. Leadership: Theory and Practice; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership and Performance beyond Expectations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J.; Jung, D.I.; Berson, Y. Predicting Unit Performance by Assessing Transformational and Transactional Leadership. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakis, J.; House, R.J. Instrumental Leadership: Measurement and Extension of Transformational–Transactional Leadership Theory. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 746–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, S.E. The Role of Transformational and Transactional Leadership in Creating, Sharing and Exploiting Organizational Knowledge. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2003, 9, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, J.E.; Judge, T.A. Personality and Transformational and Transactional Leadership: A Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Hughes, L.W.; Norman, S.M.; Luthans, K.W. Using Positivity, Transformational Leadership and Empowerment to Combat Employee Negativity. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2008, 29, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loon, M.; Mee Lim, Y.; Heang Lee, T.; Lian Tam, C. Transformational Leadership and Job-Related Learning. Manag. Res. Rev. 2012, 35, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Piccolo, R.F. Transformational and Transactional Leadership: A Meta-Analytic Test of Their Relative Validity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Job Demands-Resources Model of Burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.-J. From Emotional Labor to Customer Loyalty in Hospitality: A Three-Level Investigation with the JD-R Model and COR Theory. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3742–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernet, C.; Austin, S.; Vallerand, R.J. The Effects of Work Motivation on Employee Exhaustion and Commitment: An Extension of the JD-R Model. Work Stress 2012, 26, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.; Hetland, J.; Demerouti, E.; Olsen, O.K.; Espevik, R. Daily Transactional and Transformational Leadership and Daily Employee Engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 87, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprea, B.; Miulescu, A.; Iliescu, D. Followers’ Job Crafting: Relationships with Full-Range Leadership Model. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 4219–4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teetzen, F.; Bürkner, P.-C.; Gregersen, S.; Vincent-Höper, S. The Mediating Effects of Work Characteristics on the Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Employee Well-Being: A Meta-Analytic Investigation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Hetland, J.; Olsen, O.K.; Espevik, R. Daily Transformational Leadership: A Source of Inspiration for Follower Performance? Eur. Manag. J. 2023, 41, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillier, J.G. Factors Affecting Job Performance in Public Agencies. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2010, 34, 139–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G.A.; Selden, S.C. Why Elephants Gallop: Assessing and Predicting Organizational Performance in Federal Agencies. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2000, 10, 685–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Guy, M.E. Comparing Public Servants’ Behavior in South Korea and the United States: How Emotional Labor Moderates the Relationship between Organizational Commitment and Job Performance. Public Adm. 2023, 101, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G.A. All Measures of Performance Are Subjective: More Evidence on US Federal Agencies. In Public Service Performance: Perspectives on Measurement and Management; Boyne, G.A., Meier, K.J., O’Toole, L.J., Walker, R.M., Eds.; Cambrudge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, J.A.; Pihl-Thingvad, S. Managing Employee Innovative Behaviour through Transformational and Transactional Leadership Styles. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 918–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.K.; Davis, R.S.; Pandey, S.; Peng, S. Transformational Leadership and the Use of Normative Public Values: Can Employees Be Inspired to Serve Larger Public Purposes? Public Adm. 2016, 94, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katebi, A.; HajiZadeh, M.H. The Relationship between “Job Satisfaction” and “Job Performance”: A Meta-Analysis | Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2022, 23, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, H.H.M.; Chiu, W.C.K. Transformational Leadership and Job Performance: A Social Identity Perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2827–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwingmann, I.; Wolf, S.; Richter, P. Every Light Has Its Shadow: A Longitudinal Study of Transformational Leadership and Leaders’ Emotional Exhaustion. J. Appl. Soc. Pyschol. 2016, 46, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean | S.D. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job performance | 4.060 | 0.608 | 1 | 5 |

| Surface acting | 2.472 | 0.796 | 1 | 5 |

| Deep acting | 2.829 | 0.822 | 1 | 5 |

| Transactional leadership | 3.833 | 0.710 | 1 | 5 |

| Transformational leadership | 3.606 | 0.701 | 1 | 5 |

| Job satisfaction | 3.948 | 0.666 | 1 | 5 |

| Gender | 0.135 | 0.341 | 0 | 1 |

| Age | 2.341 | 0.967 | 1 | 4 |

| Education | 2.319 | 0.825 | 1 | 4 |

| Job grade | 2.655 | 1.401 | 1 | 7 |

| Tenure | 1.594 | 0.802 | 1 | 4 |

| Annual income | 3.849 | 2.209 | 1 | 10 |

| Model | df | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Six-factor model | 1096.07 *** | 215 | 0.05 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.03 |

| Five-factor model (JS and JP combined) | 5304.94 *** | 220 | 0.12 | 0.83 | 0.8 | 0.08 |

| Four-factor model (JS, JP, and TAL combined) | 10,220.92 *** | 224 | 0.17 | 0.66 | 0.61 | 0.12 |

| Three-factor model (JS, JP, TAL, and TFL combined) | 11,508.25 *** | 227 | 0.18 | 0.62 | 0.57 | 0.14 |

| Two-factor model (JS, JP, TAL, TFL, and DA combined) | 14,493.36 *** | 229 | 0.20 | 0.51 | 0.46 | 0.16 |

| One-factor model | 16,241.51 *** | 230 | 0.21 | 0.45 | 0.4 | 0.17 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | S.E. | β | S.E. | β | S.E. | |

| Gender (female = 1) | –0.010 | 0.039 | –0.007 | 0.038 | −0.005 | 0.038 |

| Age | 0.040 | 0.025 | 0.032 | 0.020 | 0.029 | 0.024 |

| Education | 0.034 ** | 0.016 | 0.034 ** | 0.016 | 0.034 ** | 0.016 |

| Job grade | 0.033 * | 0.019 | 0.030 | 0.019 | 0.028 | 0.019 |

| Tenure | –0.045 | 0.033 | –0.040 | 0.033 | –0.035 | 0.032 |

| Annual income | –0.002 | 0.007 | –0.004 | 0.007 | –0.001 | 0.007 |

| Job satisfaction | 0.317 *** | 0.031 | 0.283 *** | 0.031 | 0.284 *** | 0.030 |

| Transactional leadership (TAL) | 0.101 *** | 0.034 | 0.093 *** | 0.034 | 0.096 | 0.171 |

| Transformational leadership (TFL) | 0.124 *** | 0.038 | 0.101 *** | 0.037 | 0.229 | 0.175 |

| Surface acting (SA) | –0.125 *** | 0.021 | 0.070 | 0.109 | ||

| Deep acting (DA) | 0.006 | 0.017 | 0.018 | 0.103 | ||

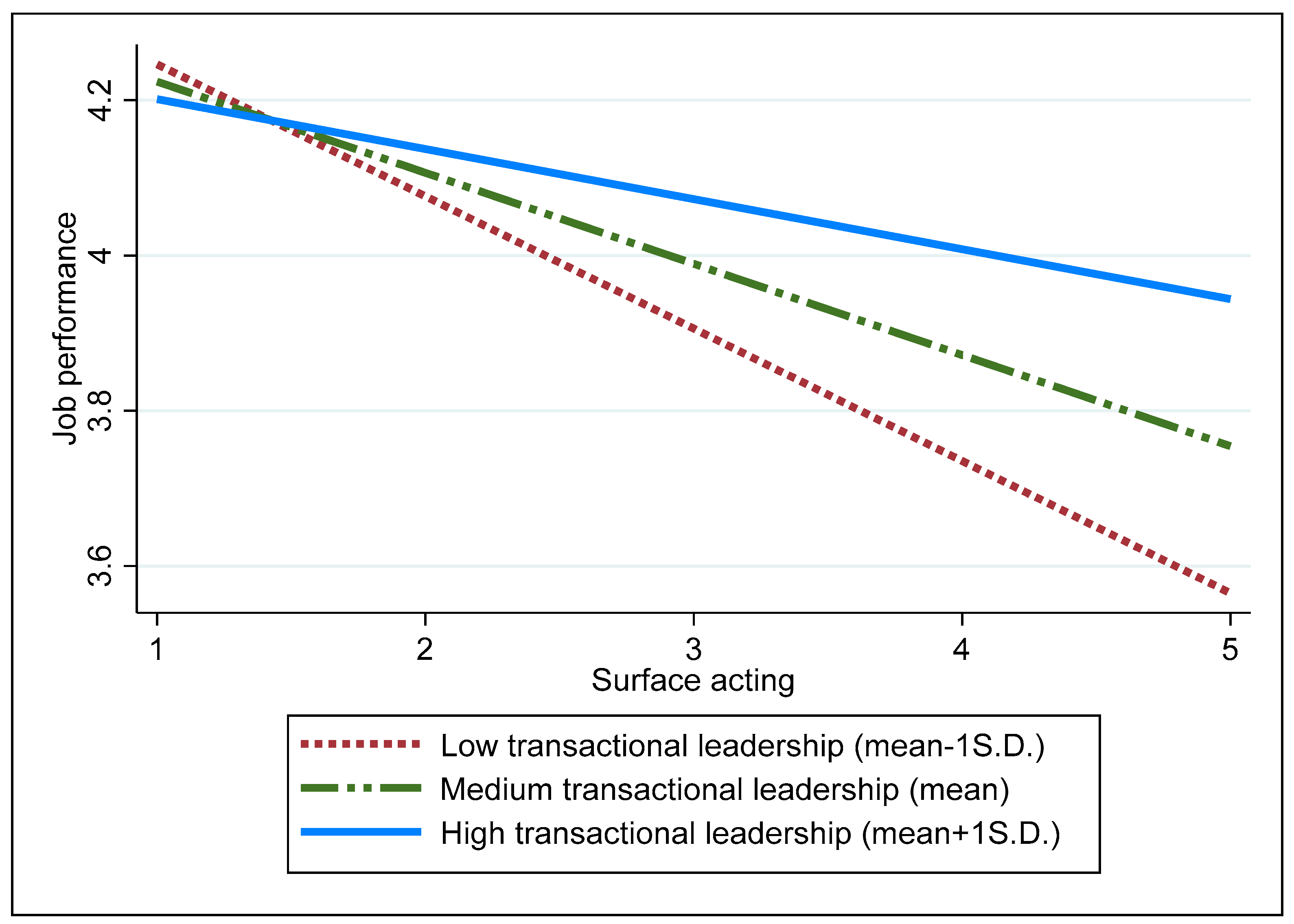

| TAL × SA | 0.075 * | 0.044 | ||||

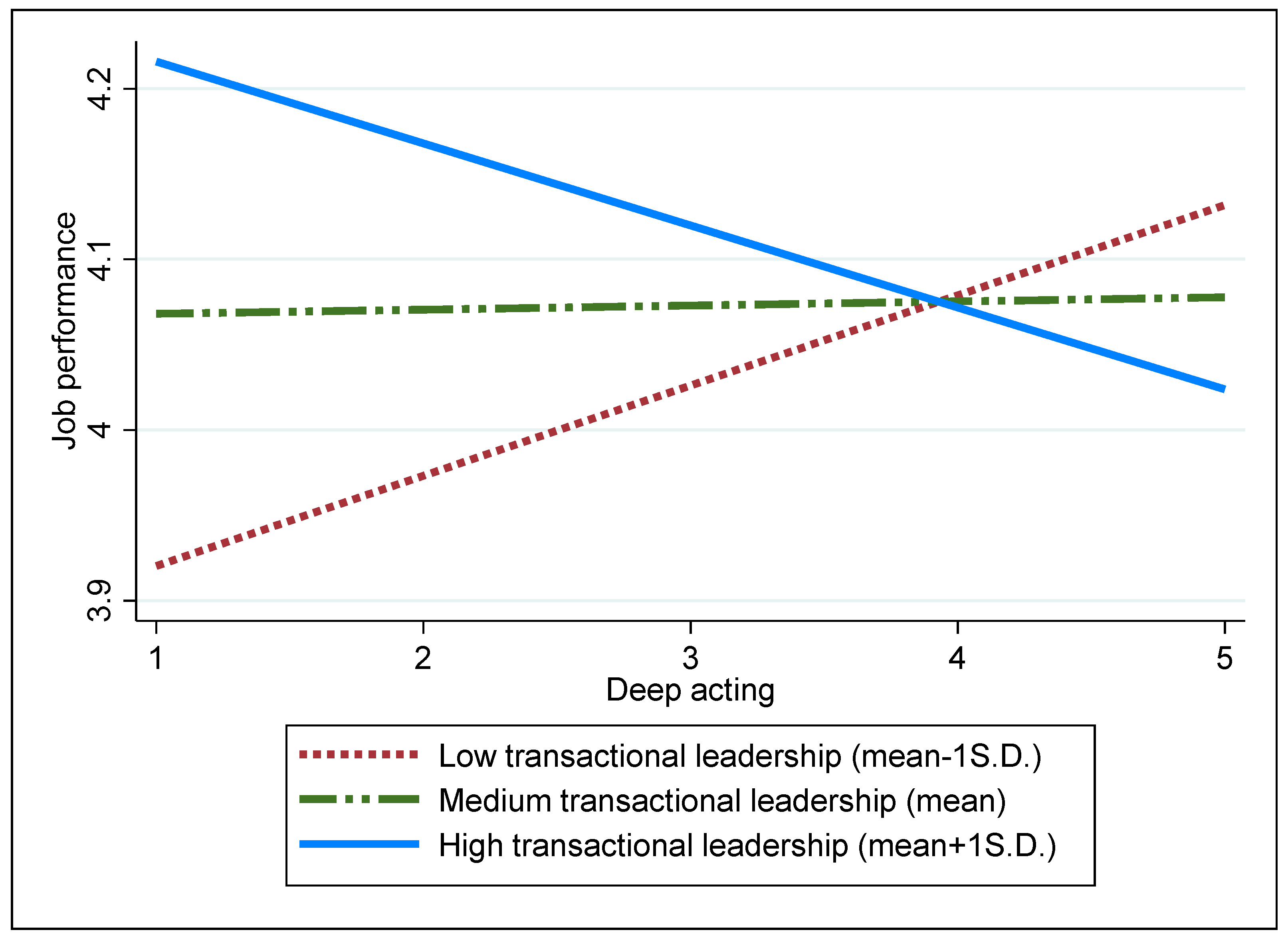

| TAL × DA | –0.072 * | 0.041 | ||||

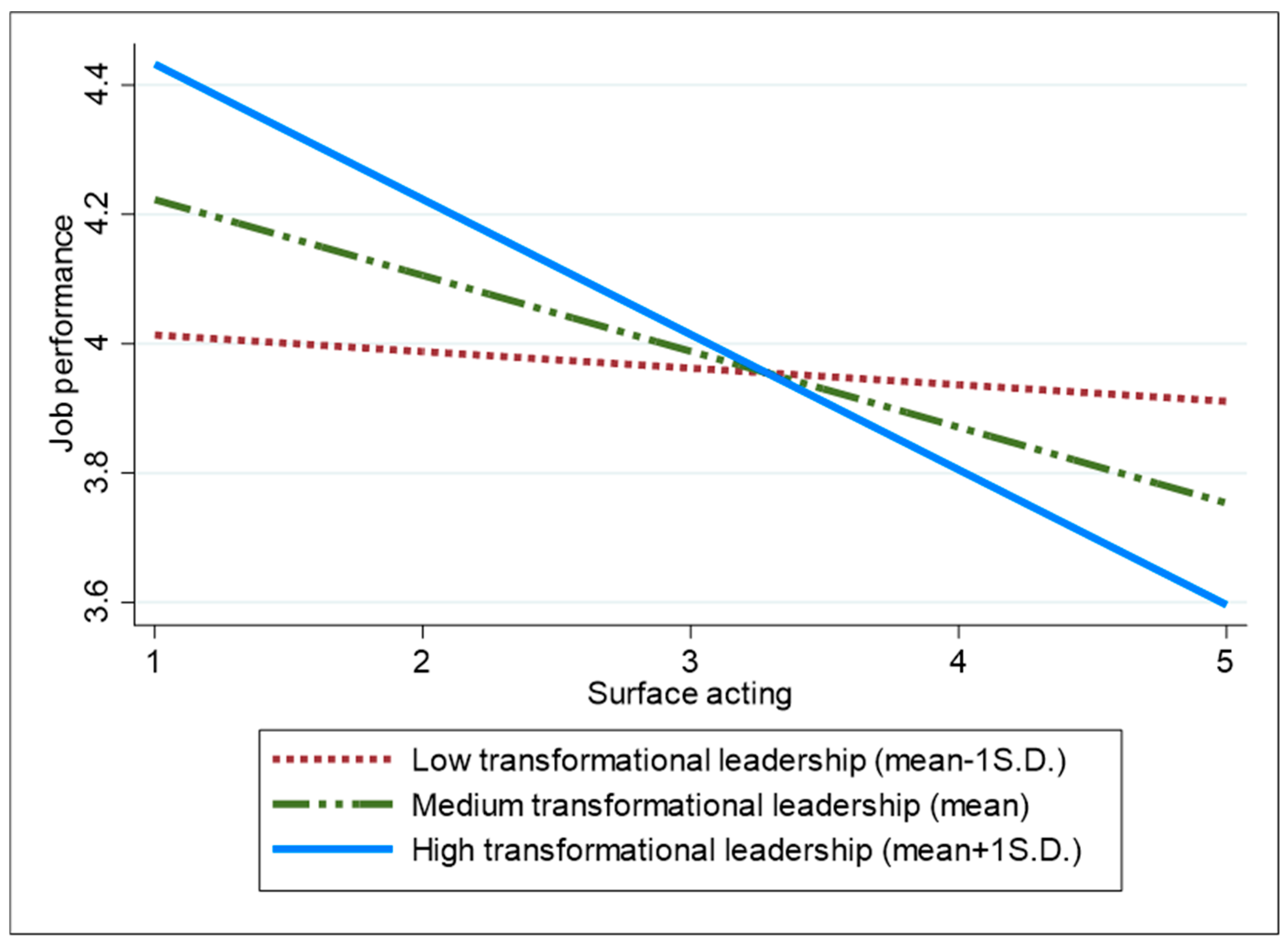

| TFL × SA | –0.132 *** | 0.045 | ||||

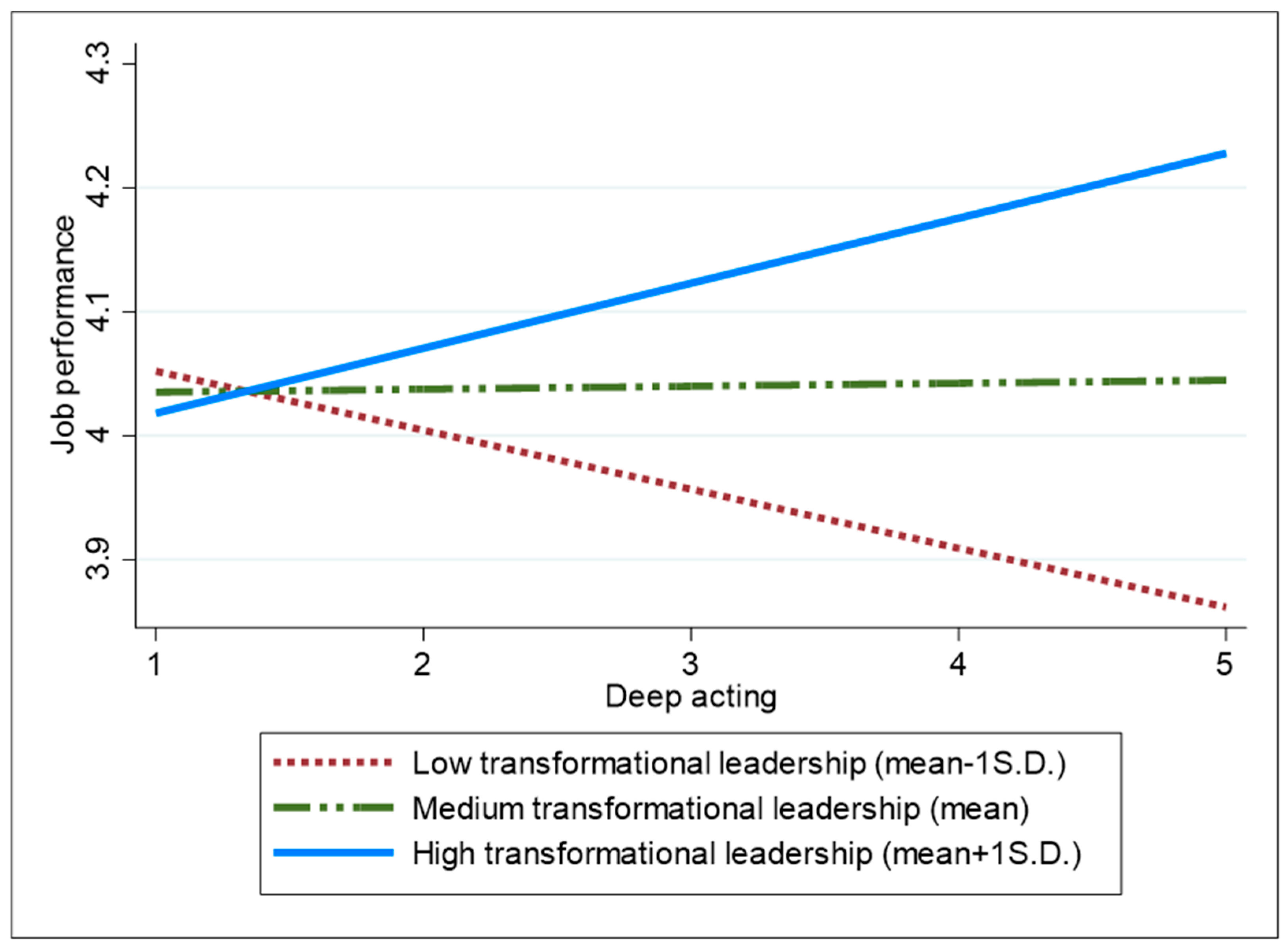

| TFL × DA | 0.072 * | 0.039 | ||||

| Constant | 1.797 *** | 0.118 | 2.354 *** | 0.164 | 1.860 *** | 0.416 |

| R-squared | 0.265 | 0.287 | 0.295 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, H.-S.; Moon, K.-K.; Ha, T.-S. The Impact of Firefighters’ Emotional Labor on Job Performance: The Moderating Effects of Transactional and Transformational Leadership. Fire 2024, 7, 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire7080291

Park H-S, Moon K-K, Ha T-S. The Impact of Firefighters’ Emotional Labor on Job Performance: The Moderating Effects of Transactional and Transformational Leadership. Fire. 2024; 7(8):291. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire7080291

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Hyeong-Su, Kuk-Kyoung Moon, and Tae-Soo Ha. 2024. "The Impact of Firefighters’ Emotional Labor on Job Performance: The Moderating Effects of Transactional and Transformational Leadership" Fire 7, no. 8: 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire7080291

APA StylePark, H.-S., Moon, K.-K., & Ha, T.-S. (2024). The Impact of Firefighters’ Emotional Labor on Job Performance: The Moderating Effects of Transactional and Transformational Leadership. Fire, 7(8), 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire7080291