Parcel-Level Risk Affects Wildfire Outcomes: Insights from Pre-Fire Rapid Assessment Data for Homes Destroyed in 2020 East Troublesome Fire

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Parcel-Level Wildfire Risk Assessment

2.1. Parcel-Level Hazard

2.2. Defensible Space

2.3. Access

2.4. Structure

2.5. Overall Risk

3. Materials and Methods

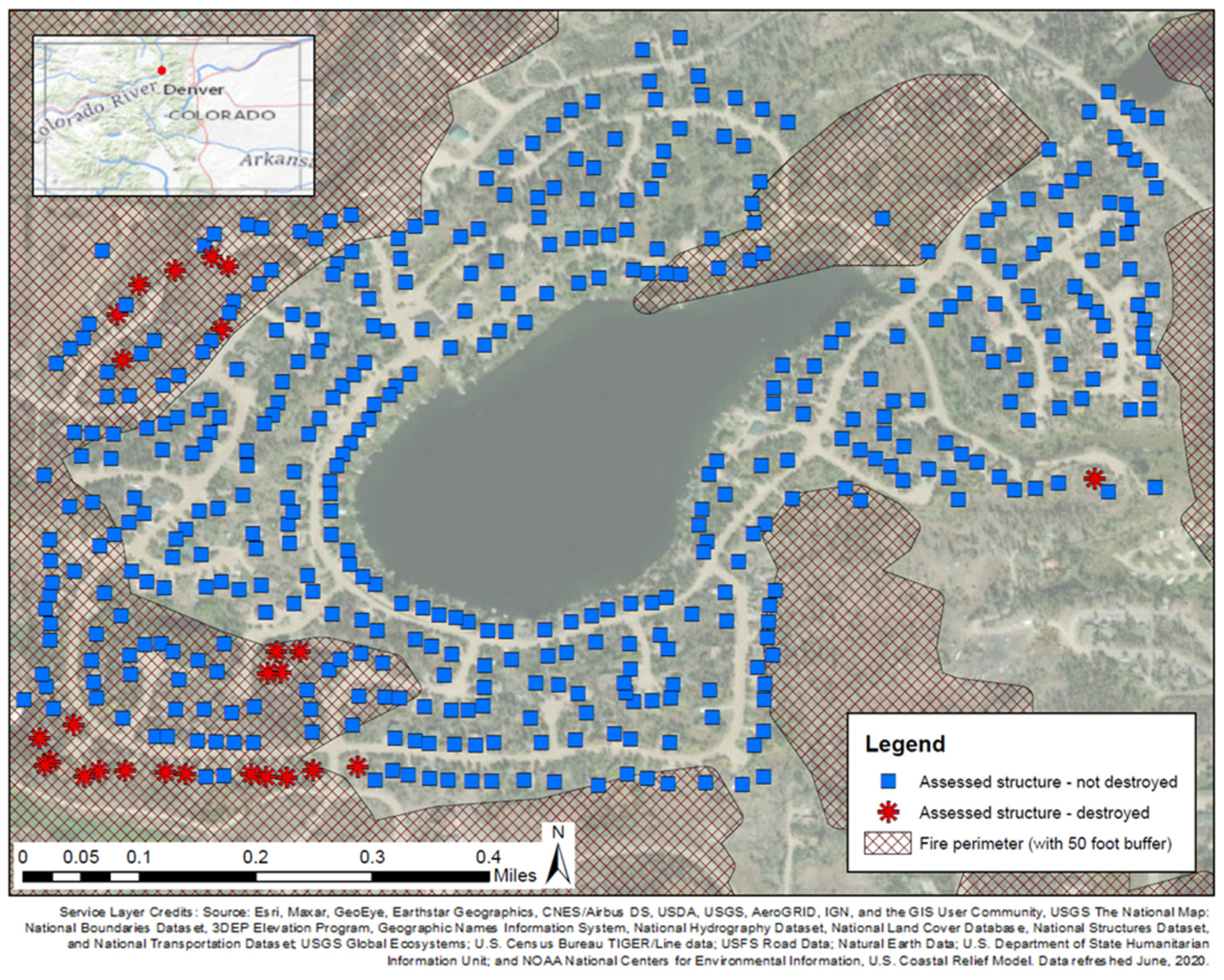

3.1. Study Context

3.2. Data

3.3. Empirical Analysis

4. Results: Risk Assessment Data Help Explain Destroyed Structures

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gill, A.M.; Stephens, S.L. Scientific and social challenges for the management of fire-prone wildland–urban interfaces. Environ. Res. Lett. 2009, 4, 034014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoennagel, T.; Balch, J.K.; Brenkert-Smith, H.; Dennison, P.E.; Harvey, B.J.; Krawchuk, M.A.; Mietkiewicz, N.; Morgan, P.; Moritz, M.A.; Rasker, R.; et al. Adapt to more wildfire in western North American forests as climate changes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 4582–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moritz, M.A.; Batllori, E.; Bradstock, R.A.; Gill, A.M.; Handmer, J.; Hessburg, P.F.; Leonard, J.; McCaffrey, S.; Odion, D.C.; Schoennagel, T.; et al. Learning to coexist with wildfire. Nature 2014, 515, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeloff, V.C.; Helmers, D.P.; Kramer, H.A.; Mockrin, M.H.; Alexandre, P.M.; Bar-Massada, A.; Butsic, V.; Hawbaker, T.J.; Martinuzzi, S.; Syphard, A.D.; et al. Rapid growth of the US wildland-urban interface raises wildfire risk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 3314–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Caggiano, M.D.; Hawbaker, T.J.; Gannon, B.M.; Hoffman, C.M. Building Loss in WUI Disasters: Evaluating the Core Components of the Wildland–Urban Interface Definition. Fire 2020, 3, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syphard, A.D.; Bar Massada, A.; Butsic, V.; Keeley, J.E. Land use planning and wildfire: Development policies influence future probability of housing loss. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Westerling, A.L.; Hidalgo, H.G.; Cayan, D.R.; Swetnam, T.W. Warming and earlier spring increase western U.S. forest wildfire activity. Science 2006, 313, 940–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abatzoglou, J.T.; Williams, A.P. Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 11770–11775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Finney, M.A. The challenge of quantitative risk analysis for wildland fire. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 211, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.P.; Calkin, D.E. Uncertainty and risk in wildland fire management: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 1895–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.H.; Thompson, M.P.; Calkin, D.E. A Wildfire Risk Assessment Framework for Land and Resource Management; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2013; p. 83.

- Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: Sendai, Japan, 2015; p. 32.

- Ludwig, K.A.; Ramsey, D.W.; Wood, N.J.; Pennaz, A.B.; Godt, J.W.; Plant, N.G.; Luco, N.; Koenig, T.A.; Hudnut, K.W.; Davis, D.K.; et al. Science for a Risky World—A U.S. Geological Survey Plan for Risk Research and Applications; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2018; p. 57.

- Caton, S.E.; Hakes, R.S.P.; Gorham, D.J.; Zhou, A.; Gollner, M.J. Review of Pathways for Building Fire Spread in the Wildland Urban Interface Part I: Exposure Conditions. Fire Technol. 2016, 53, 429–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syphard, A.D.; Rustigian-Romsos, H.; Keeley, J.E. Multiple-Scale Relationships between Vegetation, the Wildland–Urban Interface, and Structure Loss to Wildfire in California. Fire 2021, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAC-LN. Promoting Fire Adapted Communities through Property Assessments: Data & Tools. Fire Adapted Community Learning Network: A Quick Guide for Community Leaders, Number 2.1. 2015, p. 2. Available online: https://fireadaptednetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/FACQuickGuide2.1.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Hakes, R.S.P.; Caton, S.E.; Gorham, D.J.; Gollner, M.J. A Review of Pathways for Building Fire Spread in the Wildland Urban Interface Part II: Response of Components and Systems and Mitigation Strategies in the United States. Fire Technol. 2016, 53, 475–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarles, S.L.; Valachovic, Y.; Nakamura, G.M.; Nader, G.A.; De Lasaux, M.J. Home Survival in Wildfire-Prone Areas: Building Materials and Design Considerations; Publication 8393; University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources: St. Davis, CA, USA, 2010; 22p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champ, P.; Barth, C.; Brenkert-Smith, H.; Falk, L.; Gomez, J.; Meldrum, J. Putting people first: Using social science to reduce risk. Wildfire Magazine. International Association of Wildland Fire, Missoula, MT, USA. 2021, pp. 30–34. Available online: https://www.iawfonline.org/article/putting-people-first-using-social-science-to-reduce-risk/ (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Maranghides, A.; McNamara, D.; Mell, W.; Trook, J.; Toman, B. A Case Study of a Community Affected by the Witch and Guejito Fires: Report# 2: Evaluating the Effects of Hazard Mitigation Actions on Structure Ignitions; National Institute of Standards and Technology, US Department of Commerce and US Forest Service: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2013.

- Duff, T.J.; Penman, T.D. Determining the likelihood of asset destruction during wildfires: Modelling house destruction with fire simulator outputs and local-scale landscape properties. Saf. Sci. 2021, 139, 105196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syphard, A.D.; Brennan, T.J.; Keeley, J.E. The role of defensible space for residential structure protection during wildfires. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2014, 23, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuy, J. Slope and Fuel Load Effects on Fire Behavior: Laboratory Experiments in Pine Needles Fuel Beds. Int. J. Wildland Fire 1995, 5, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.; Ribeiro, C.; Raposo, J.; Viegas, D.X.; André, J. Effect of Canyons on a Fire Propagating Laterally Over Slopes. Front. Mech. Eng. 2019, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Viegas, D.X.; Simeoni, A. Eruptive Behaviour of Forest Fires. Fire Technol. 2011, 47, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alexandre, P.M.; Stewart, S.I.; Keuler, N.S.; Clayton, M.K.; Mockrin, M.H.; Bar-Massada, A.; Syphard, A.D.; Radeloff, V.C. Factors related to building loss due to wildfires in the conterminous United States. Ecol. Appl. 2016, 26, 2323–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syphard, A.D.; Brennan, T.J.; Keeley, J.E. The importance of building construction materials relative to other factors affecting structure survival during wildfire. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 21, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, R.T. Hayman Fire Case Study; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2003.

- Penman, S.H.; Price, O.F.; Penman, T.D.; Bradstock, R.A. The role of defensible space on the likelihood of house impact from wildfires in forested landscapes of south eastern Australia. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2019, 28, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, E.E.; Valachovic, Y.S.; Quarles, S.L.; Johnson, N.G. Housing arrangement and vegetation factors associated with single-family home survival in the 2018 Camp Fire, California. Fire Ecol. 2021, 17, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.D.; Stratton, R.D. Home Destruction Examination: Grass Valley Fire, Lake Arrowhead, California; Technol Paper R5-TP-026b; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Region (Region 5): Vallejo, CA, USA, 2008; 26p.

- Kolden, C.A.; Henson, C. A socio-ecological approach to mitigating wildfire vulnerability in the wildland urban interface: A case study from the 2017 Thomas fire. Fire 2019, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, J.D. Preventing disaster: Home ignitability in the wildland-urban interface. J. For. 2000, 98, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M.E.; Stocks, B.J.; Wotton, B.M.; Flannigan, M.D.; Todd, J.B. The international crown fire modelling experiment: An overview and progress report. In Proceedings of the Second Symposium on Fire and Forest Meteorology, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 11–16 January 1998; pp. 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, P.; Van Bommel, L.; Gill, A.M.; Cary, G.J.; Driscoll, D.A.; Bradstock, R.A.; Knight, E.; Moritz, M.A.; Stephens, S.L.; Lindenmayer, D.B. Land management practices associated with house loss in wildfires. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, O.F.; Whittaker, J.; Gibbons, P.; Bradstock, R. Comprehensive Examination of the Determinants of Damage to Houses in Two Wildfires in Eastern Australia in 2013. Fire 2021, 4, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cova, T.J.; Theobald, D.M.; Norman, J.B.; Siebeneck, L.K. Mapping wildfire evacuation vulnerability in the western US: The limits of infrastructure. GeoJournal 2013, 78, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cova, T.J. Public safety in the urban–wildland interface: Should fire-prone communities have a maximum occupancy? Nat. Hazards Rev. 2005, 6, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, T.K.; McFarlane, B.L.; Varghese, J. An examination of the influence of hazard experience on wildfire risk perceptions and adoption of mitigation measures. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2009, 22, 308–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.C.; Monroe, M.C.; Johnson, J.F. The Look of the Land: Homeowner Landscape Management and Wildfire Preparedness in Minnesota and Florida. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2005, 18, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Cova, T.J.; Dennison, P.E.; Wan, N.; Nguyen, Q.C.; Siebeneck, L.K. Why do we need a national address point database to improve wildfire public safety in the U.S.? Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 39, 101237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhaver, A. Why Some Homes Survived: Learning from the Fort Mcmurray Wildland/Urban Interface Fire Disaster; Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Quarles, S.L.; Standoher-Alfano, C.D. Wildfire Research: Ignition Potential of Decks Subjected to an Ember Exposure; Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety: Richburg, SC, USA, 2018; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Quarles, S.; Pohl, K. Costs of WUI Codes and Standards for New Construction. In Encyclopedia of Wildfires and Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) Fires; Manzello, S.L., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calkin, D.E.; Cohen, J.D.; Finney, M.A.; Thompson, M.P. How risk management can prevent future wildfire disasters in the wildland-urban interface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- InciWeb. East Troublesome Fire Information. Available online: https://inciweb.nwcg.gov/incient/7242 (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- NIFC. Interagency Fire Perimeter History—All Years. National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC). 2021. Available online: https://data-nifc.opendata.arcgis.com/datasets/nifc::interagency-fire-perimeter-history-all-years/about (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Warziniack, T.; Champ, P.; Meldrum, J.; Brenkert-Smith, H.; Barth, C.M.; Falk, L.C. Responding to Risky Neighbors: Testing for Spatial Spillover Effects for Defensible Space in a Fire-Prone WUI Community. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2018, 73, 1023–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L. Spatial Econometrics: Methods and Models; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 1988; p. 284. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- LeSage, J.; Pace, R.K. Introduction to Spatial Econometrics; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- CSFS. The Home Ignition Zone: A Guide to Preparing Your Home for Wildfire and Creating Defensible Space; Colorado State University: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2021; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Butry, D.; Donovan, G.H. Protect thy neighbor: Investigating the spatial externalities of community wildfire hazard mitigation. For. Sci. 2008, 54, 417–428. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.H.; Burgan, R.E. Standard Fire Behavior Fuel Models: A Comprehensive Set for Use with Rothermel’s Surface Fire Spread Model; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2005; p. 72.

- LANDFIRE. LANDFIRE 1.4.0 Scott and Burgan Fire Behavior Fuel Models (FBMF40) and Existing Vegetation Type (EVT) layers. 2017. Available online: https://landfire.gov/ (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Sisante, A.M.; Taylor, M.H.; Rollins, K.S. Understanding homeowners’ decisions to mitigate wildfire risk and create defensible space. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2019, 28, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meldrum, J.R.; Brenkert-Smith, H.; Champ, P.; Gomez, J.; Falk, L.; Barth, C. Interactions between resident risk perceptions and wildfire risk mitigation: Evidence from simultaneous equations modeling. Fire 2019, 2, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paveglio, T.B.; Stasiewicz, A.M.; Edgeley, C.M. Understanding support for regulatory approaches to wildfire management and performance of property mitigations on private lands. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, B.; Kyle, G.T.; Absher, J.D. An examination of the social-psychological drivers of homeowner wildfire mitigation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 70, 101442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attribute Name and Description | Attribute Levels | Points | Not Destroyed (n = 329) | Destroyed (n = 23) | Moran Test p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Distance to hazardous topography Distance from residence to ridge, steep drainage, or narrow canyon | More than 150 feet | 0 | 87.8% | 91.3% | <0.001 |

| Between 50 and 150 feet | 25 | 8.2% | 8.7% | ||

| Less than 50 feet | 50 | 4.0% | 0.0% | ||

| 2: Slope Overall slope of the property near the residence | Gentle—Less than 20% | 0 | 81.8% | 100.0% | <0.001 |

| Moderate—Between 20% and 45% | 10 | 17.3% | 0.0% | ||

| Steep—Greater than 45% | 20 | 0.9% | 0.0% | ||

| 3: Adjacent fuels Dominant vegetation on the property and those properties immediately surrounding it | Light—Grasses | 10 | 0.6% | 0.0% | <0.001 |

| Medium—Light brush and/or isolated trees | 20 | 75.7% | 87.0% | ||

| Dense—Dense brush and/or dense trees | 40 | 23.7% | 13.0% | ||

| 4: Distance to nearest home Closest distance to a neighboring residence | More than 100 feet | 0 | 1.8% | 0.0% | <0.001 |

| Between 30 and 100 feet | 50 | 59.3% | 47.8% | ||

| Between 10 and 30 feet | 100 | 35.6% | 39.1% | ||

| Less than 10 feet | 200 | 3.3% | 13.0% | ||

| 5: Defensible space (vegetation) Distance to overgrown, dense, or unmaintained vegetation | More than 150 feet | 0 | 10.3% | 8.7% | <0.001 |

| Between 31 and 150 feet | 50 | 43.5% | 52.2% | ||

| Between 10 and 30 feet | 75 | 33.4% | 13.0% | ||

| Less than 10 feet | 100 | 12.8% | 26.1% | ||

| 6: Defensible space (other combustibles) Distance to other combustible items (e.g., lumber, firewood, propane tank, hay bales) | More than 30 feet | 0 | 30.4% | 13.0% | 0.694 |

| Between 10 and 30 feet | 40 | 45.3% | 43.5% | ||

| Less than 10 feet | 80 | 24.3% | 43.5% | ||

| 7: Ingress/egress Roads available in case one is blocked | Two or more roads in/out | 0 | 62.9% | 60.9% | <0.001 |

| One road in/out | 10 | 37.1% | 39.1% | ||

| 8: Driveway clearance Width of the driveway at the narrowest point | More than 26 feet wide | 0 | 9.4% | 4.4% | 0.881 |

| Between 20 and 26 feet wide | 5 | 31.6% | 34.8% | ||

| Less than 20 feet wide | 10 | 59.0% | 60.9% | ||

| 9: Address visibility Visibility of house number at the end of the driveway | House number is visible and reflective | 0 | 8.5% | 4.4% | <0.001 |

| House number is visible but not reflective | 5 | 36.8% | 34.8% | ||

| House number is not visible | 10 | 54.7% | 60.9% | ||

| 10: Roof material Most vulnerable roofing material | Tile, metal, or asphalt shingles | 0 | 99.7% | 95.7% | 0.436 |

| Wood (shake shingles) | 300 | 0.3% | 4.4% | ||

| 11: Siding material Most vulnerable siding material | Noncombustible (e.g., stucco, brick, stone) | 0 | 2.7% | 0.0% | 0.223 |

| Log or heavy timbers | 35 | 13.4% | 21.7% | ||

| Wood or vinyl siding | 70 | 83.9% | 78.3% | ||

| 12: Attachments Combustible items attached to structure | No balcony, deck, porch, or fence | 0 | 5.8% | 8.7% | 0.444 |

| Combustible balcony, deck, porch, or fence | 100 | 94.2% | 91.3% |

| Attribute Name and Description | Attribute Levels | Not Destroyed (n = 329) | Destroyed (n = 23) | Moran Test p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13: Category score: Parcel-level hazard | Sum of points for attributes 1 through 4 | 102.5 | 113.9 | 0.166 |

| 14: Category score: Defensible space | Sum of points for attributes 5 and 6 | 97.1 | 114.1 | 0.064 |

| 15: Category score: Access | Sum of points for attributes 7 through 9 | 18.9 | 19.6 | 0.672 |

| 16: Category score: Structure | Sum of points for attributes 10 through 12 | 158.5 | 166.7 | 0.644 |

| 17: Overall risk score | Sum of points for attributes 1 through 12 | 277.1 | 414.3 | <0.001 |

| y = 1 If Structure Destroyed; y = 0 Otherwise n = 352 | Constant (α) | Independent Variable (X) | Spatial Lag on Independent Variable (WX) | Spatial Lag on Dependent Variable (Wy) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| coef. | std.err. | p > |z| | coef. | std.err. | p > |z| | coef. | std.err. | p > |z| | coef. | std.err. | p > |z| | |

| 1: Distance to hazardous topography | −0.149 | 0.053 | 0.005 | −0.0015 | 0.0008 | 0.077 | 0.0178 | 0.0110 | 0.104 | 2.473 | 0.470 | <0.001 |

| 2: Slope | 0.000 | 0.031 | 0.998 | −0.0024 | 0.0017 | 0.155 | −0.0201 | 0.0167 | 0.229 | 1.654 | 0.337 | <0.001 |

| 3: Adjacent fuels | 0.506 | 0.112 | <0.001 | −0.0005 | 0.0011 | 0.635 | −0.0261 | 0.0054 | <0.001 | 3.036 | 0.448 | <0.001 |

| 4: Distance to nearest home | 0.253 | 0.065 | <0.001 | 0.0004 | 0.0004 | 0.273 | −0.0062 | 0.0013 | <0.001 | 3.670 | 0.584 | <0.001 |

| 5: Defensible space (vegetation) | 0.348 | 0.124 | 0.005 | 0.0007 | 0.0005 | 0.138 | −0.0083 | 0.0023 | <0.001 | 2.392 | 0.410 | <0.001 |

| 6: Defensible space (other combustibles) | 0.304 | 0.085 | <0.001 | 0.0006 | 0.0004 | 0.101 | −0.0129 | 0.0028 | <0.001 | 3.550 | 0.575 | <0.001 |

| 7: Ingress/egress | 0.142 | 0.062 | 0.021 | 0.0086 | 0.0026 | 0.001 | −0.0580 | 0.0177 | 0.001 | 1.545 | 0.334 | <0.001 |

| 8: Driveway clearance | 0.403 | 0.095 | <0.001 | 0.0014 | 0.0028 | 0.607 | −0.0749 | 0.0150 | <0.001 | 3.125 | 0.471 | <0.001 |

| 9: Address visibility | 0.303 | 0.093 | 0.001 | 0.0069 | 0.0033 | 0.038 | −0.0647 | 0.0147 | <0.001 | 2.738 | 0.465 | <0.001 |

| 10: Roof material | −0.033 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 0.0013 | 0.0011 | 0.239 | −0.0142 | 0.0068 | 0.036 | 1.942 | 0.443 | <0.001 |

| 11: Siding material | 0.439 | 0.116 | <0.001 | −0.0001 | 0.0008 | 0.922 | −0.0091 | 0.0018 | <0.001 | 3.036 | 0.491 | <0.001 |

| 12: Attachments | 0.419 | 0.105 | <0.001 | −0.0003 | 0.0006 | 0.584 | −0.0058 | 0.0012 | <0.001 | 3.209 | 0.484 | <0.001 |

| 13: Category score: Parcel-level hazard | 0.337 | 0.082 | <0.001 | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | 0.572 | −0.0051 | 0.0011 | <0.001 | 3.547 | 0.546 | <0.001 |

| 14: Category score: Defensible space | 0.337 | 0.112 | 0.003 | 0.0006 | 0.0003 | 0.071 | −0.0054 | 0.0013 | <0.001 | 2.969 | 0.466 | <0.001 |

| 15: Category score: Access | 0.356 | 0.105 | 0.001 | 0.0034 | 0.0015 | 0.019 | −0.0285 | 0.0060 | <0.001 | 2.611 | 0.411 | <0.001 |

| 16: Category score: Structure | 0.335 | 0.126 | 0.008 | 0.0005 | 0.0006 | 0.425 | −0.0035 | 0.0007 | <0.001 | 3.169 | 0.479 | <0.001 |

| 17: Overall risk score (100 points) | 0.284 | 0.120 | 0.018 | 0.0366 | 0.0216 | 0.090 | −0.1525 | 0.0311 | <0.001 | 3.260 | 0.502 | <0.001 |

| y = 1 If Structure Destroyed; y = 0 Otherwise n = 352 | Total Impact | Direct Impact | Indirect Impact | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dy/dx | std.err. | p > |z| | dy/dx | std.err. | p > |z| | dy/dx | std.err. | p > |z| | |

| 1: Distance to hazardous topography | −0.0115 | 0.0060 | 0.053 | −0.0003 | 0.0161 | 0.987 | −0.0113 | 0.0170 | 0.508 |

| 2: Slope | 0.0286 | 0.0307 | 0.352 | −0.0027 | 0.0018 | 0.131 | 0.0313 | 0.0294 | 0.287 |

| 3: Adjacent fuels | 0.0132 | 0.0023 | <0.001 | 0.0003 | 0.0052 | 0.959 | 0.0129 | 0.0042 | 0.002 |

| 4: Distance to nearest home | 0.0022 | 0.0003 | <0.001 | 0.0004 | 0.0006 | 0.496 | 0.0018 | 0.0004 | <0.001 |

| 5: Defensible space (vegetation) | 0.0057 | 0.0018 | 0.002 | 0.0005 | 0.0008 | 0.524 | 0.0052 | 0.0018 | 0.004 |

| 6: Defensible space (other combustibles) | 0.0049 | 0.0011 | <0.001 | 0.0009 | 0.0021 | 0.690 | 0.0041 | 0.0015 | 0.005 |

| 7: Ingress/egress | 0.0813 | 0.0587 | 0.166 | 0.0083 | 0.0024 | <0.001 | 0.0730 | 0.0592 | 0.218 |

| 8: Driveway clearance | 0.0347 | 0.0060 | <0.001 | 0.0020 | 0.0053 | 0.706 | 0.0327 | 0.0063 | <0.001 |

| 9: Address visibility | 0.0340 | 0.0075 | <0.001 | 0.0067 | 0.0041 | 0.104 | 0.0273 | 0.0087 | 0.002 |

| 10: Roof material | 0.0286 | 0.2200 | 0.897 | 0.0023 | 0.0153 | 0.879 | 0.0262 | 0.2047 | 0.898 |

| 11: Siding material | 0.0046 | 0.0010 | <0.001 | 0.0002 | 0.0021 | 0.926 | 0.0044 | 0.0019 | 0.021 |

| 12: Attachments | 0.0027 | 0.0005 | <0.001 | −0.0003 | 0.0007 | 0.649 | 0.0031 | 0.0009 | <0.001 |

| 13: Category score: Parcel-level hazard | 0.0020 | 0.0005 | <0.001 | 0.0003 | 0.0010 | 0.769 | 0.0017 | 0.0006 | 0.007 |

| 14: Category score: Defensible space | 0.0025 | 0.0007 | <0.001 | 0.0011 | 0.0140 | 0.936 | 0.0014 | 0.0135 | 0.919 |

| 15: Category score: Access | 0.0160 | 0.0040 | <0.001 | 0.0038 | 0.0025 | 0.128 | 0.0122 | 0.0041 | 0.003 |

| 16: Category score: Structure | 0.0014 | 0.0004 | <0.001 | 0.0005 | 0.0006 | 0.419 | 0.0009 | 0.0009 | 0.305 |

| 17: Overall risk score (100 points) | 0.0512 | 0.0120 | <0.001 | 0.0363 | 0.0222 | 0.101 | 0.0149 | 0.0321 | 0.643 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meldrum, J.R.; Barth, C.M.; Goolsby, J.B.; Olson, S.K.; Gosey, A.C.; White, J.; Brenkert-Smith, H.; Champ, P.A.; Gomez, J. Parcel-Level Risk Affects Wildfire Outcomes: Insights from Pre-Fire Rapid Assessment Data for Homes Destroyed in 2020 East Troublesome Fire. Fire 2022, 5, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire5010024

Meldrum JR, Barth CM, Goolsby JB, Olson SK, Gosey AC, White J, Brenkert-Smith H, Champ PA, Gomez J. Parcel-Level Risk Affects Wildfire Outcomes: Insights from Pre-Fire Rapid Assessment Data for Homes Destroyed in 2020 East Troublesome Fire. Fire. 2022; 5(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire5010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeldrum, James R., Christopher M. Barth, Julia B. Goolsby, Schelly K. Olson, Adam C. Gosey, James (Brad) White, Hannah Brenkert-Smith, Patricia A. Champ, and Jamie Gomez. 2022. "Parcel-Level Risk Affects Wildfire Outcomes: Insights from Pre-Fire Rapid Assessment Data for Homes Destroyed in 2020 East Troublesome Fire" Fire 5, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire5010024

APA StyleMeldrum, J. R., Barth, C. M., Goolsby, J. B., Olson, S. K., Gosey, A. C., White, J., Brenkert-Smith, H., Champ, P. A., & Gomez, J. (2022). Parcel-Level Risk Affects Wildfire Outcomes: Insights from Pre-Fire Rapid Assessment Data for Homes Destroyed in 2020 East Troublesome Fire. Fire, 5(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire5010024