1. Introduction

The virtual cathode oscillator has been studied for many years as one of the promising sources of high-power microwaves [

1,

2]. It has potential advantages over other types of microwave devices, especially in compactness and high-power capabilities. The compactness stems from both its relatively simple structure and the omission of an external magnetic field. The high-power capability of the virtual cathode oscillator is closely associated with its operation principle that depends on the space charge effects of the high-current electron beam.

On the other hand, the virtual cathode oscillator has seemingly inevitable shortcomings, such as relatively low efficiency, unstable oscillation frequency, and relatively short electrode lifetime. These roadblocks have hardly budged in recent decades, despite of enduring efforts on experimental investigation, theoretical analysis, and numerical simulation [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. The difficulty that hinders our progress on the virtual cathode oscillator is believed to be related to the lack of a convincing physical model that can describe the microwave generation mechanism in the virtual cathode oscillator.

It is commonly suggested that microwaves are generated in virtual cathode oscillators by two mechanisms: the electron oscillation in the potential well and the intrinsic oscillation of the virtual cathode. The potential well is the electron trap formed between the cathode and the virtual cathode, with the anode mesh or foil at the center. If we look at a single electron with certain kinetic energy in this potential well, it will certainly oscillate back and forth and, as a result, emit some electromagnetic radiation. However, if a continuous electron beam covers the whole potential well, all radiations should cancel out each other and there will be no net energy transfer between the electrons and the electromagnetic field, unless the electron density is properly modulated. There have been conceptual suggestions about the modulation scenario in the potential well, but none of them can describe the interaction in a quantitative manner. Furthermore, this interaction mechanism requires a stable potential well, which contradicts electron density modulation because half of the potential well is actually formed by the space charge of the electrons.

The second mechanism, virtual cathode oscillation, has received increased attention in recent years. In fact, most of the latest virtual cathode oscillators are designed so that the microwave energy is extracted only from the virtual cathode side of the anode, excluding the diode from the interaction area. It is generally believed that virtual cathode oscillation creates some kind of beam current modulation that interacts with the electromagnetic field on the background, resulting in field enhancement. This physical picture is largely supported by experimental and simulation studies, although the interaction’s specifics have never been given in physical detail.

This tutorial article is aimed at providing an introductory description for the beam-field interaction in the virtual cathode oscillator. It is the third article of a three-article series on the virtual cathode oscillator. The first article [

25] presented a one-dimensional theoretical description for the space-charge effect and the steady-state virtual cathode. The second article [

26] introduced a simulation method that can be used to study the time-dependent behavior of virtual cathode oscillation.

This third article is devoted to the interaction between the electron beam and the electromagnetic field in the virtual cathode oscillator. The numerical method described in the second article is used to find the average energy variation in the electrons, which leads us to the conditions of electromagnetic field enhancement.

Section 2 provides a brief summary of the method and previously obtained simulation results.

Section 3 reports on the interaction between the oscillating virtual cathode and a very weak oscillating field in the background.

Section 4 considers the situation when the field intensity is increased. The conclusion and some discussions are provided in

Section 5.

2. Virtual Cathode Oscillation

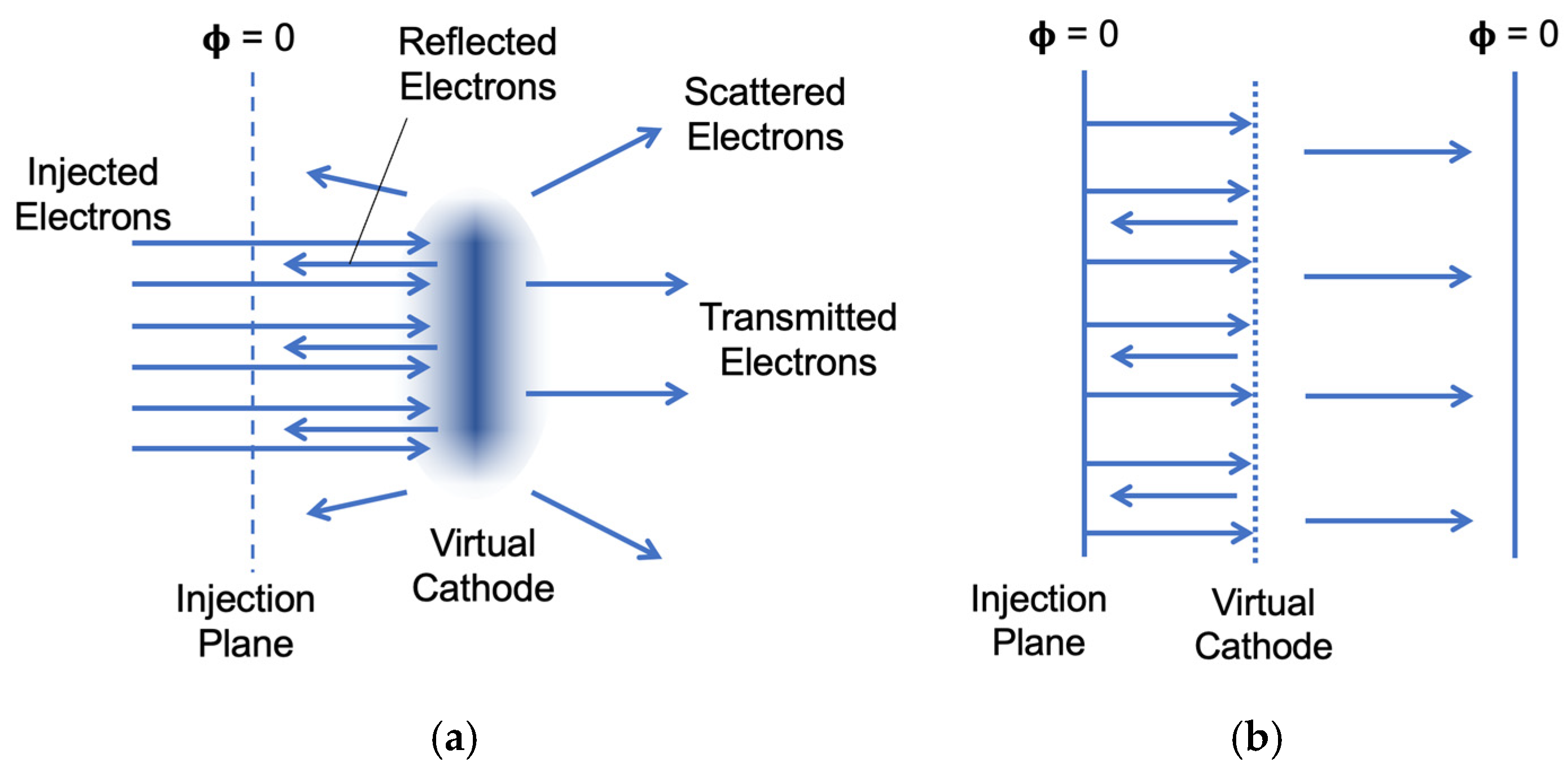

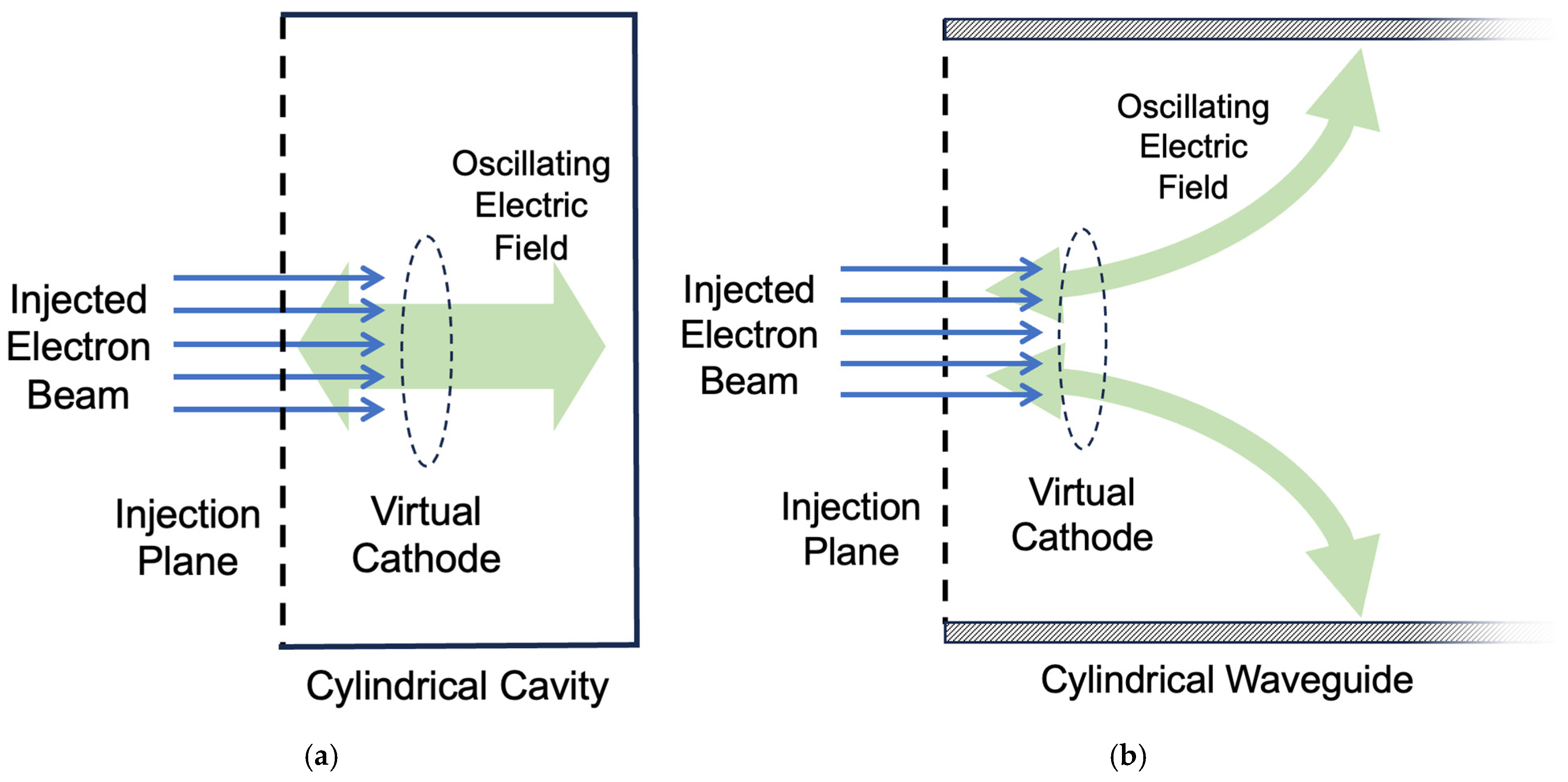

A typical virtual cathode is illustrated in

Figure 1a, where an electron beam with initial electron kinetic energy passes through a conducting plane, such as a thin foil or a wired mesh, and enters a void space. Here, the space charge of the electron beam causes spatial variation in the electric potential and, as a result, in the electron kinetic energy. The degree of this variation depends mainly on the electron-beam current density and the boundary condition of the space. If the potential variation reaches the point that the electron kinetic energy drops to zero, we call the corresponding location a virtual cathode. Near the virtual cathode, the electrons can be reflected, transmitted, or scattered to other directions.

If we consider the virtual cathode in a one-dimensional manner, which is commonly used for near-one-dimensional situations and for simplifying the problem when trying to understand the mechanism, the model is reduced to that shown in

Figure 1b. Here, the virtual cathode splits the incoming electron beam into two parts, the reflected beam and the transmitted beam. For this situation, a theoretical description of the steady-state virtual cathode has been obtained, although it is also recognized that the virtual cathode is unstable [

25].

For the time-dependent behavior of the virtual cathode, there is no analytical theory, even for a one-dimensional description. However, numerical simulations can provide us with a comprehensive picture about the dynamic behavior of the virtual cathode [

26]. It turned out that the virtual cathode oscillates periodically which results in current modulation in both the reflected beam and the transmitted beam.

It is noted that there are different mechanisms that may lead to virtual cathode oscillation. As has been observed in one-dimensional simulations [

26], the virtual cathode is intrinsically unstable and tends to oscillate even when the injected beam current is constant. However, this oscillation results in a modulation in the reflected electron beam which, due to its space-charge effect in the diode region, can cause a modulation in the injected electron beam. Since this modulation is delayed by the time-of-flight of the electrons, it may also interfere with, or even dominate, the intrinsic virtual cathode oscillation. Nevertheless, in this tutorial article, the effect of the diode is not considered, in order to concentrate on the virtual cathode. In other words, this article deals with a stand-alone virtual cathode driven by a constant electron beam.

When the mechanism of a beam-driven microwave source is considered, it always comes down to the beam current modulation and its interaction with the electromagnetic field. From this point view, the current modulation created by the virtual cathode oscillation certainly provides an important clue about the mechanism of the virtual cathode oscillator. This article is an attempt to follow this lead and to study the beam-field interaction using the numerical method published before [

26]. In this section, for the reader’s convenience, this numerical approach is briefly summarized.

In one-dimensional simulations, the model that is used is shown in

Figure 1b. An electron beam, with initial electron energy of eV

0 and beam current density of J

in, is injected into a space, which is defined by two grounded planes of gap D. It is important to note that the numerical simulations are carried out for normalized variables so that the specific values of beam parameters (V

0 and J

in) are not required by the calculation. In other words, the simulation is not run for a particular set of given parameters, but for their dimensionless counterparts instead. For this reason, the simulation is considered to be general to a certain extent, and the results are valid for a wide range of parametric conditions.

The normalization relations are given below.

where

d is defined as following,

The simulations are carried out only for the normalized (dimensionless) variables, E′, ϕ′, n′, J′, v′, z′, and t′. For any given values of parameters V0 and Jin, the simulation results, expressed in physical variables (E, ϕ, n, J, v, z and t), can be obtained by using the above relations. In fact, as will be seen below, we have presented and interpreted the simulation results in ratios of the same physical quantities so that the actual values of V0 and Jin are not required.

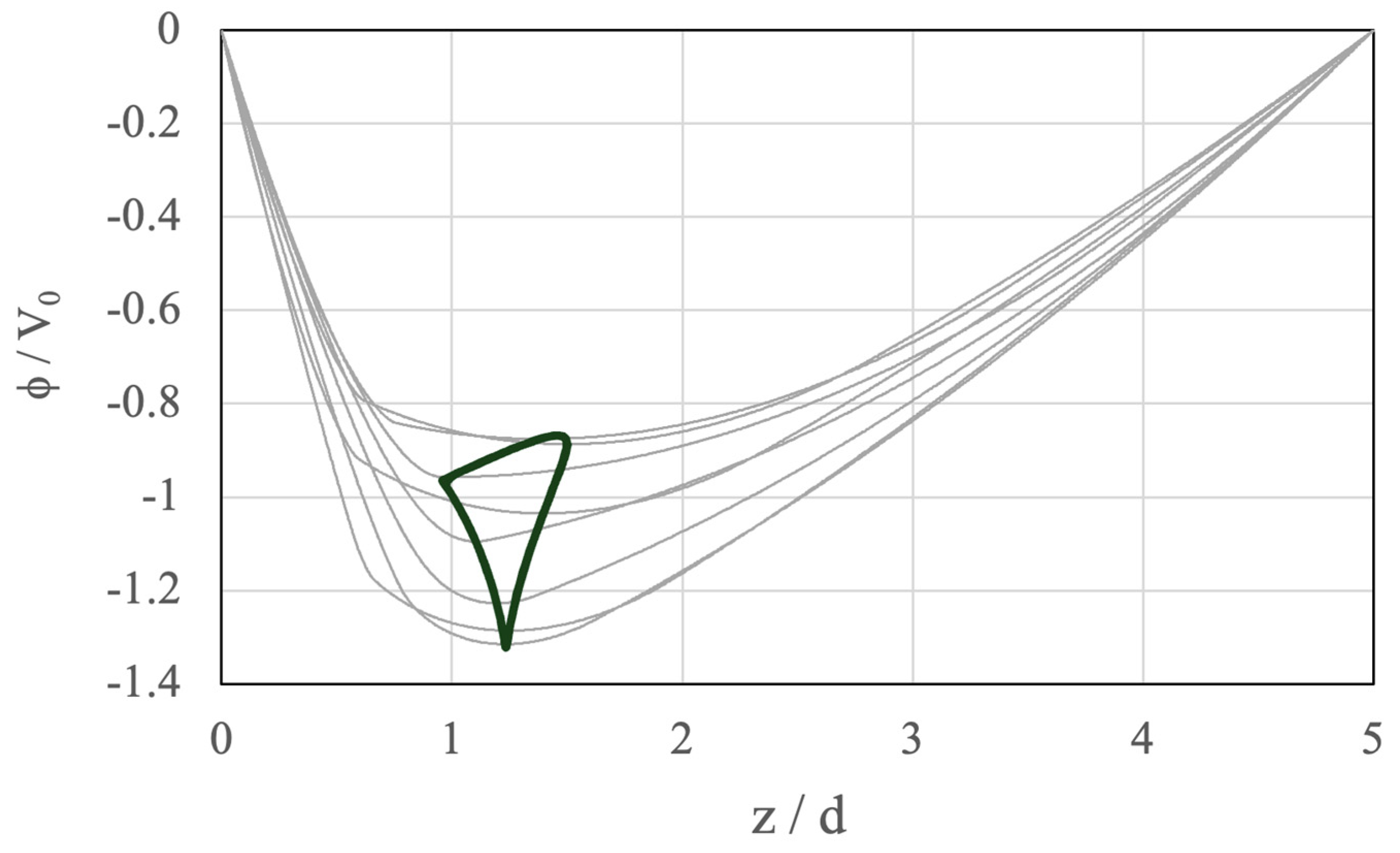

For example,

Figure 2 shows the simulation results of the electric potential distributions obtained at a sequence of timings, for D/d = 5. The timings were chosen so that they could roughly represent a period of oscillation. The bold line in

Figure 2 shows the trajectory of the potential minimum in one cycle, which is the same as that shown in Figure 7c of [

26].

The oscillatory behavior observed in

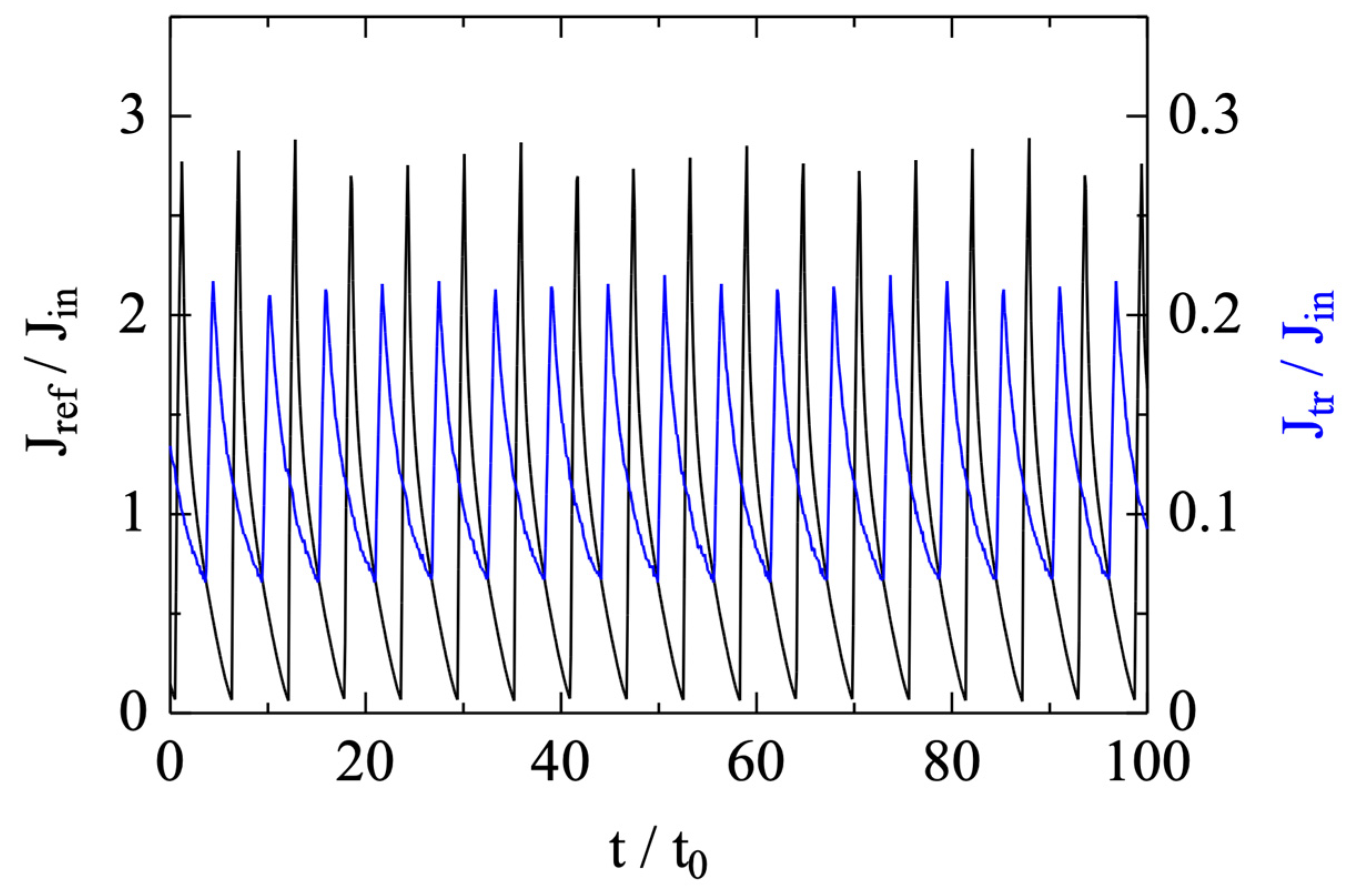

Figure 2 causes current modulations in both the reflected and the transmitted electron beams.

Figure 3 shows the waveforms of the current densities for the reflected beam and the transmitted beam, obtained at corresponding boundaries, respectively. Strong current modulations in both beams are clearly observed. The average current ratio between the reflected and the transmitted beams is about 0.88/0.12.

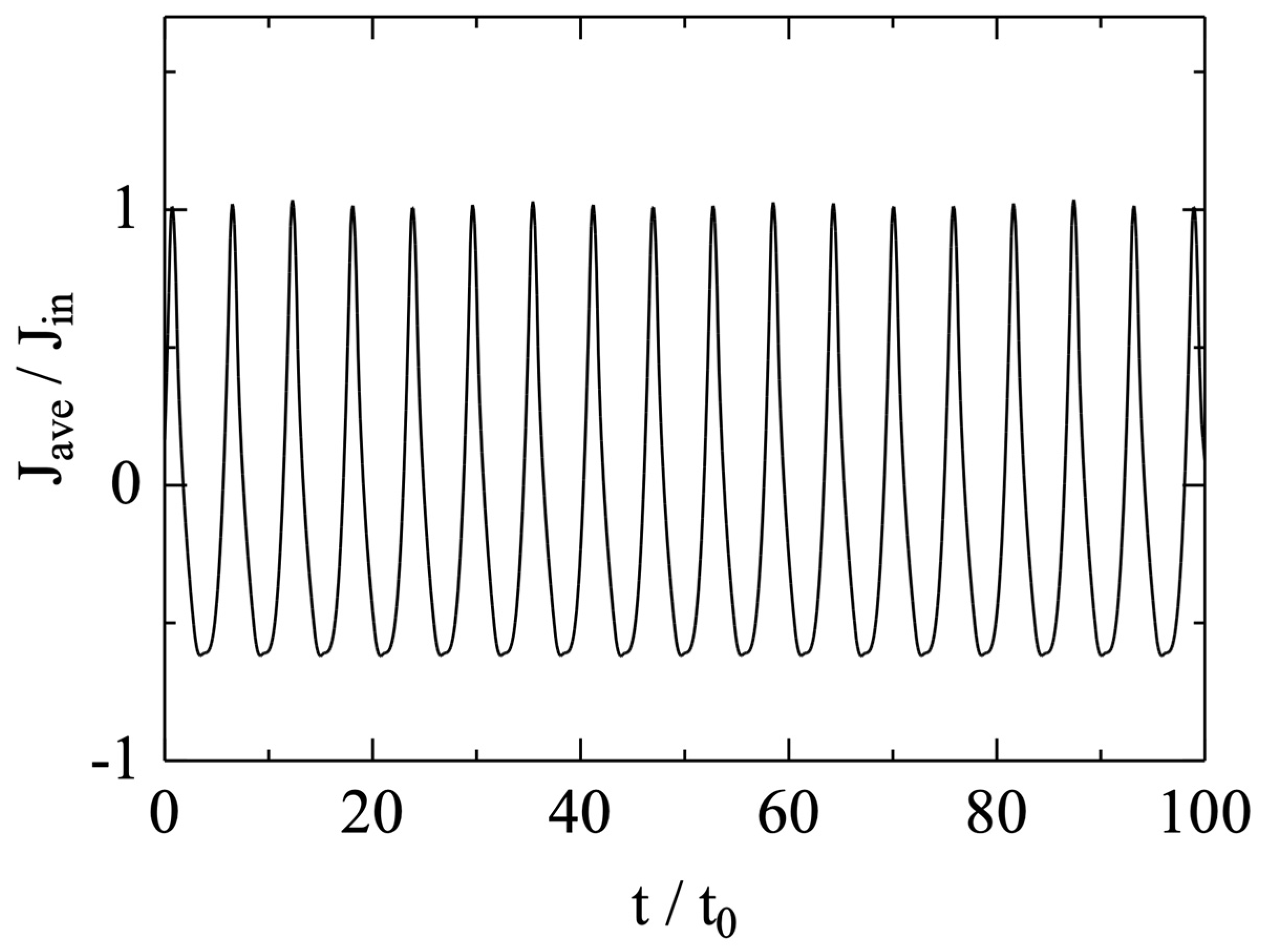

Figure 4 shows the waveform of the spatially averaged current density between the virtual cathode and the injection plane (the lefthand-side boundary), which is important to the beam-field interaction, as will be explained in the next section. The beam current in this region has two components, the injected beam and the reflected beam. Since the injected beam current is constant, the oscillation seen in

Figure 4 is caused by that of the reflected beam.

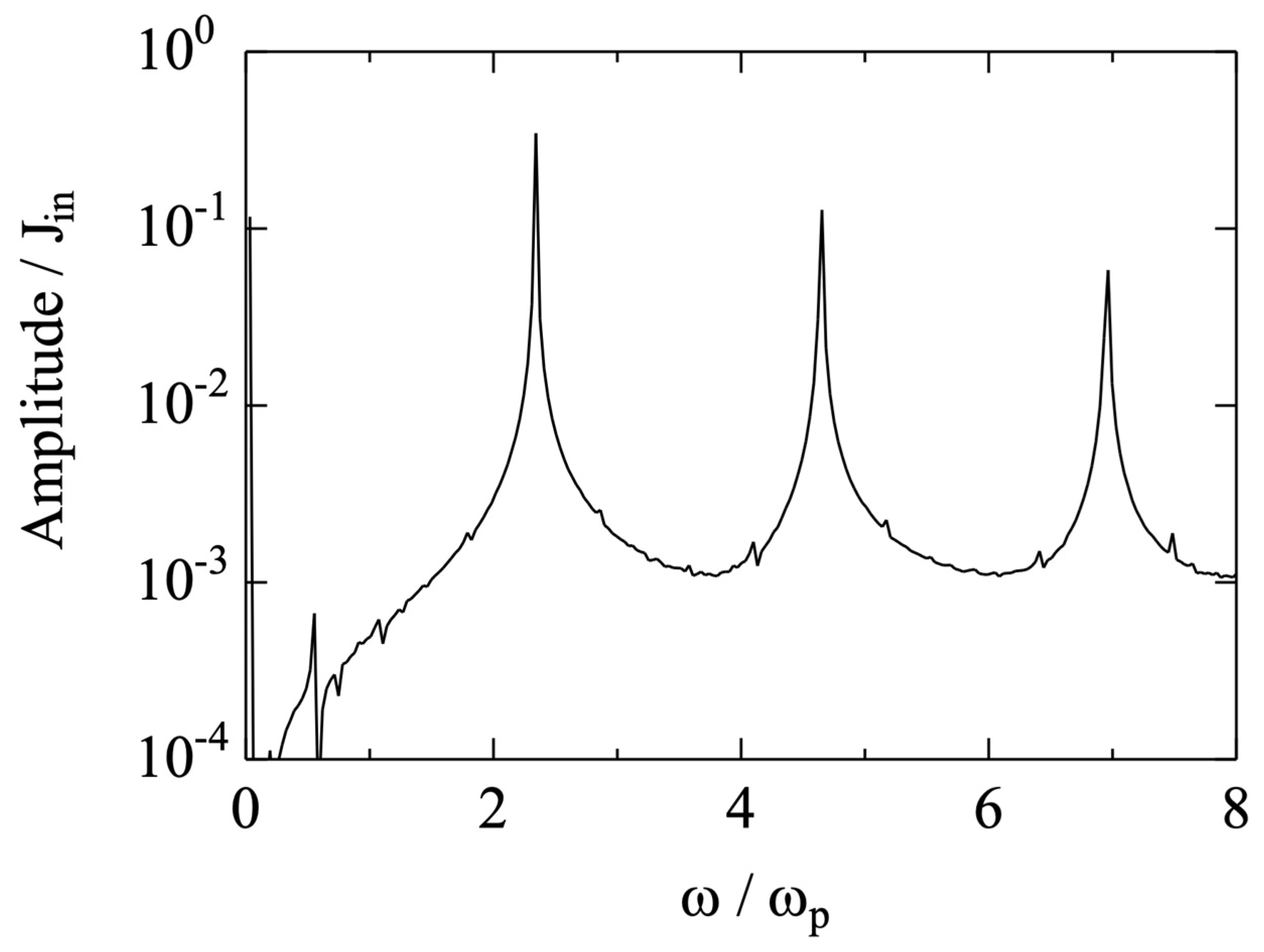

The fast Fourier transformation (FFT) of the current waveform shown

Figure 4 provides the result of

Figure 5. The frequency is normalized by the plasma frequency (ω

p) using Equation (31) of [

26]. The main component of the oscillation frequency is about ω/ω

p ≈ 2.3, which corresponds to the period we see in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. Regarding the higher-frequency peaks, the mathematical explanation is that the original waveform is not purely sinusoidal, although they may carry some unknown physical information.

3. The Interaction Between Electron Beam and Electromagnetic Field

For microwave generation, there must be some kind of interaction between the electron beam and the microwave. In general, it is the electric field component of the electromagnetic wave that interacts with the electron beam, resulting in net energy exchange. Given the oscillatory behavior of the electromagnetic field, the beam current must be modulated and the modulation frequency must be consistent with that of the microwave so that net energy transfer can occur.

Different microwave devices use different methods to generate beam current modulation. For the virtual cathode oscillator, the electron beam is modulated by the virtual cathode oscillation, as we have seen in the last section.

Still, there are two modulated beams in the virtual cathode oscillator, the reflected beam and the transmitted beam. Some may suggest that the transmitted electron beam can interact with the electromagnetic mode in the downstream structure and contribute to microwave radiation. However, there are two problems with the transmitted beam. First, the transmitted electrons travel at a lower velocity than the electromagnetic wave unless a slow-wave structure is used. Second, the injected beam current is usually much higher than the space-charge-limited current so that the transmitted beam current is only a small fraction of the original electron beam, as seen in

Figure 3.

The reflected electron beam, which carries most of the injected electrons and is strongly modulated, moves toward the injection plane. If there is an interaction between the reflected beam and the electromagnetic field, it happens in the space between the virtual cathode and the injection plane. Since the injection plane, usually the anode for the electron-beam diode on the other side, is conductive, the electric field component of the electromagnetic field on the virtual cathode side must be perpendicular to its surface, which is parallel to the electrons’ movement. In this case, every reflected electron sees an oscillating electric field and is either accelerated or decelerated, depending on its timing relative to field oscillation. It is made apparent that the net energy transfer depends on how many electrons are accelerated relative to those decelerated and this is why beam modulation is necessary.

The situation is illustrated in

Figure 6.

Figure 6a shows a virtual cathode in a pillbox-shaped cavity, where the TM mode of the cavity forms an axial electric field that covers the virtual cathode area. If the resonant frequency of the cavity mode matches that of the virtual cathode oscillation, it should interact with the reflected beam, as described above.

On the other hand, if the virtual cathode is formed in a cylindrical waveguide or a relatively long cylindrical cavity without an externally applied magnetic field, which is more commonly used in experimental devices, the electric field distribution near the injection plane should look like that depicted in

Figure 6b. In this case, the electric field configuration in the interaction area, which is the space between the virtual cathode and the injection plane, is similar to that of

Figure 6a and, therefore, the same interaction can be expected.

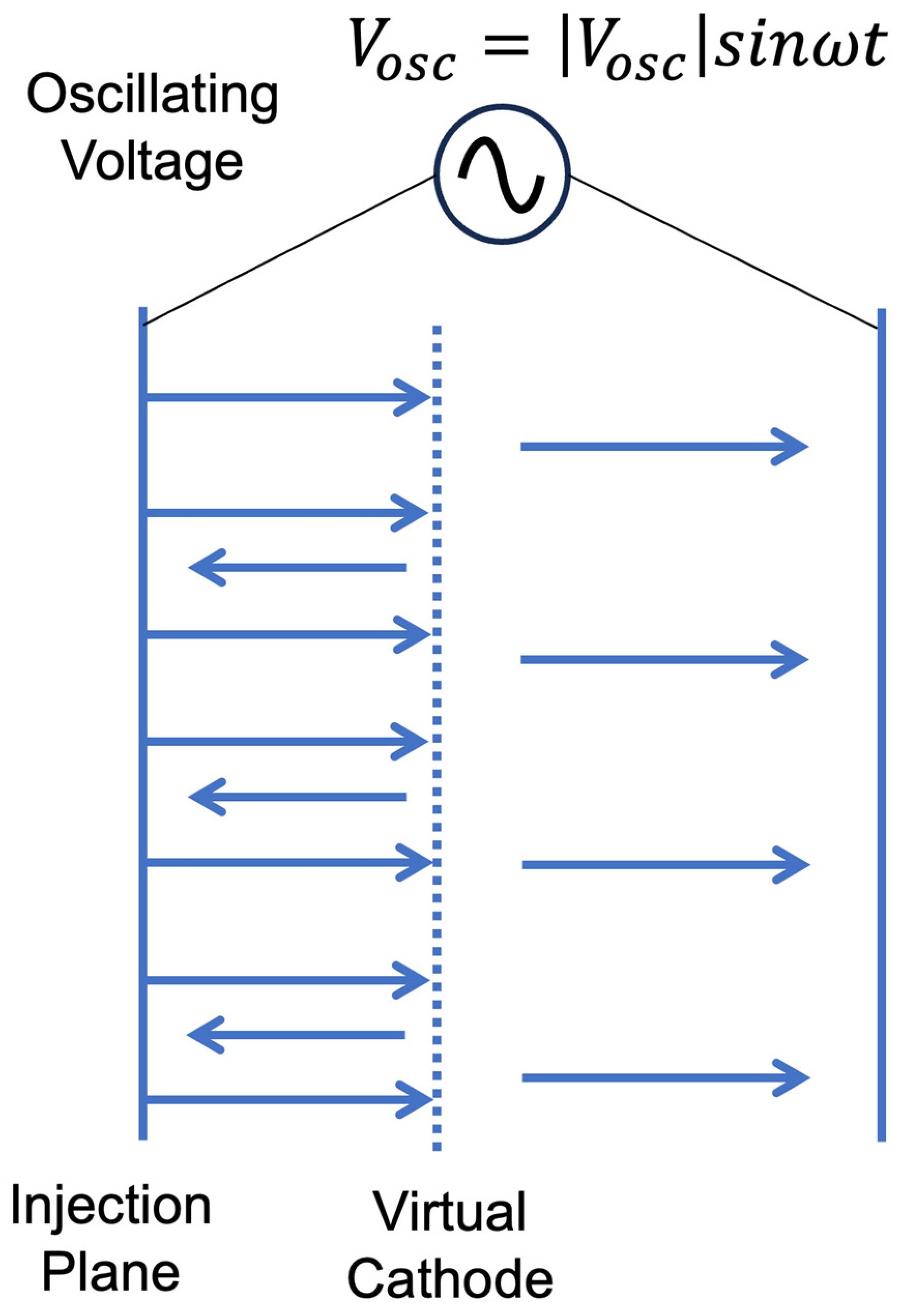

To study this interaction in a one-dimensional manner, the model shown in

Figure 7 has been used. Basically, it is the model shown in

Figure 1b combined with an oscillating voltage applied between two boundaries.

This oscillating voltage effectively creates an oscillating electric field over the whole area. The model practically represents the situation of

Figure 6a, except for its one-dimensional nature. It should also provide us with information about the interaction for the case of

Figure 6b, because we only look at the reflected electron beam. The fact that the transmitted electrons may also interact with the externally applied electric field is not important as long as the field does not turn them back to the virtual cathode.

The basic approach is to apply an oscillating electric field over the interaction region and see how the average electron energy changes. In an ideal beam-field interaction, there are only two participants, the electron beam and the microwave. If one of them loses some energy, the other must gain the same amount of energy, in order to satisfy the energy conservation law. Based on this principle, in the studies of this article, we equate electron energy loss with microwave energy gain.

To begin, we first apply a very weak oscillating field of the same frequency as the virtual cathode oscillation. Here, the applied field is so low that it does not have any effect on the behavior of the virtual cathode. However, the field can cause slight variation in the electron energy, from which we can tell how the energy is flowing.

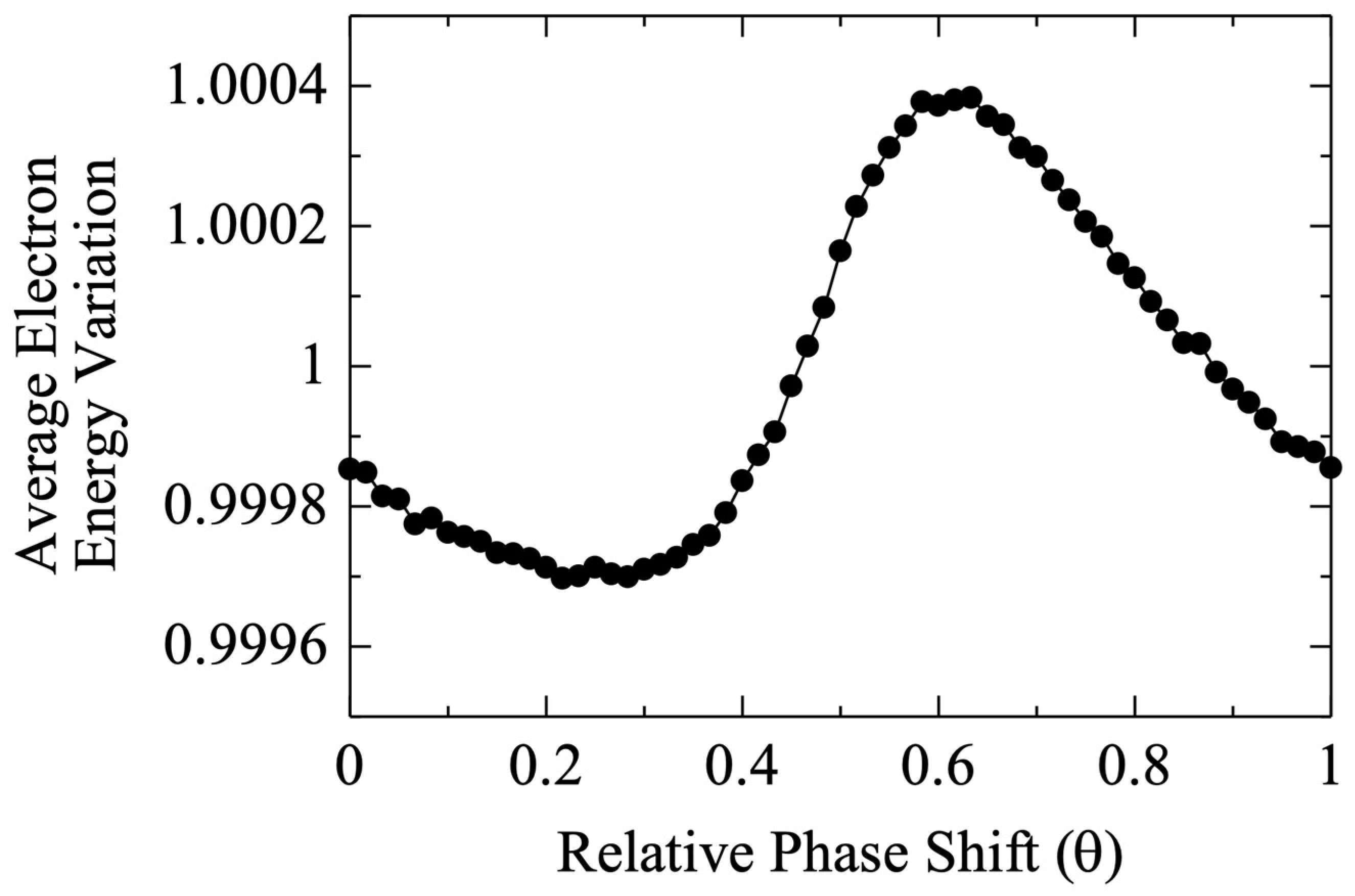

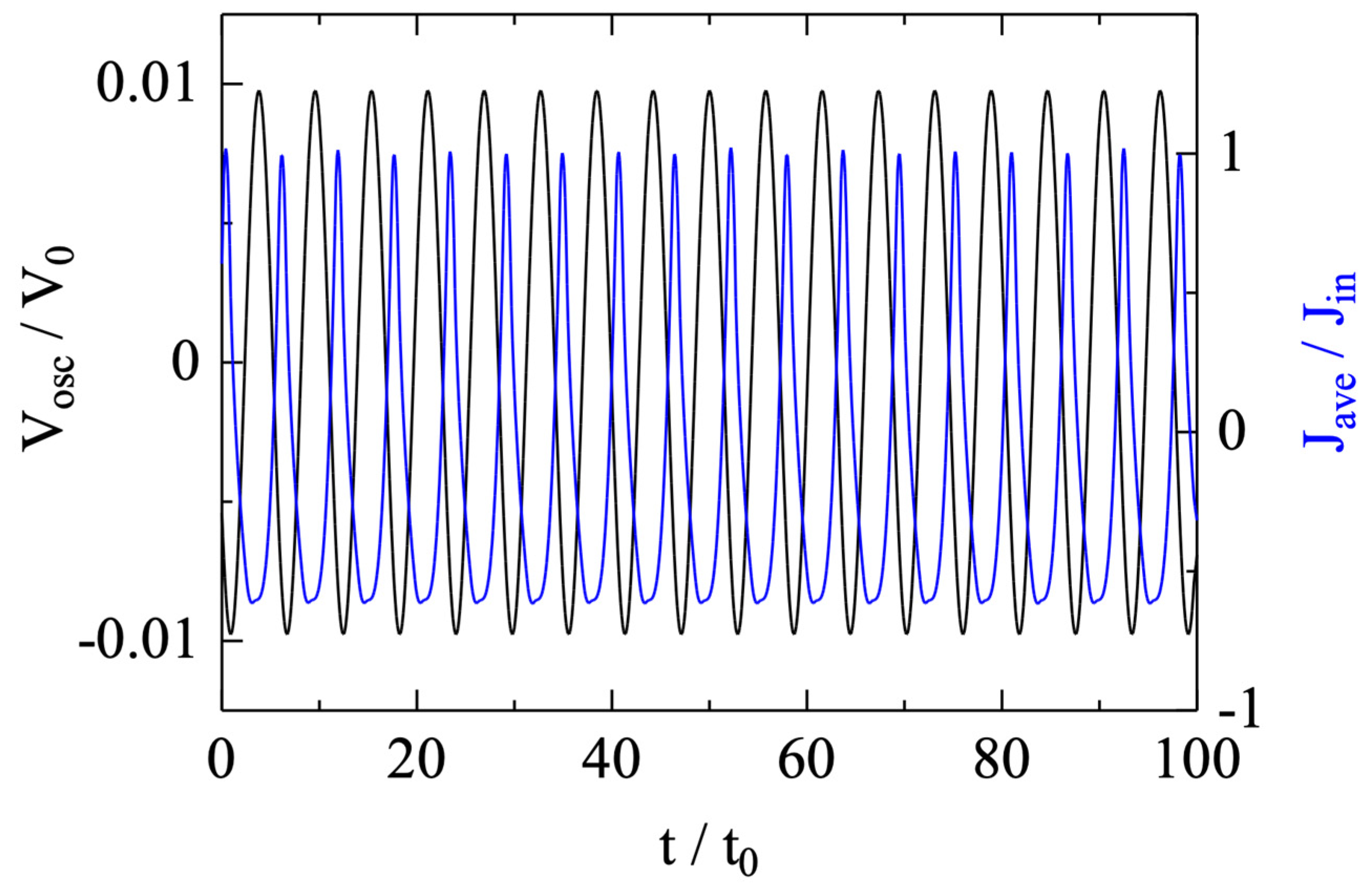

Figure 8 shows the simulation results obtained with |V

osc| = 0.01V

0, where |V

osc| is the amplitude of the externally applied oscillating voltage. In

Figure 8, the average electron energy of the reflected beam is plotted as a function of the relative phase difference between the oscillation of the applied voltage and that of the virtual cathode. The results were obtained by carrying out a number of simulations while changing the starting phase of the oscillating voltage over a cycle. Since the virtual cathode oscillates independently, this phase shift results in different phase relations between two oscillations.

Because the beam current is modulated, depending on its relative timing to the electric field, it may lose or gain energy on average. In

Figure 8, the positive part represents electron beam energy gain or microwave energy loss, and the negative part represents the opposite, which is where our interest is when we consider microwave generation. For the condition of the minimum point of the curve shown in

Figure 8, the waveform of the applied voltage is plotted in

Figure 9, together with that of the current waveform shown in

Figure 4. Since the field is uniformly applied across the entire region, it is only the spatially averaged current that really matters when we consider the energy exchange. From

Figure 9, it is seen that the field is mostly in an opposite phase relative to the current, indicating average energy loss of the electron beam.

As an approximate approach, the interaction described above has been quantitatively evaluated as follows. Assume that the spatially averaged current oscillation can be written as

where θ is the phase difference with that of the externally applied oscillating voltage.

The average energy exchange between two oscillations is obtained as

The sinusoidal dependence of Equation (11) on θ is roughly consistent with that seen in

Figure 8. From

Figure 5, we see that the amplitude of the fundamental frequency is about 0.2

Jin. In addition, with D/d = 5, we estimate that the amplitude of the oscillating voltage between the virtual cathode and the injection plane is about 1/5 of that of the whole space, which is therefore obtained as 0.002V

0. Consequently, the amplitude of Equation (11) has been estimated to be 0.0002V

0J

in. This result suggests the average electron energy variation to be within ±0.02%, which is in general agreement with that of

Figure 8.

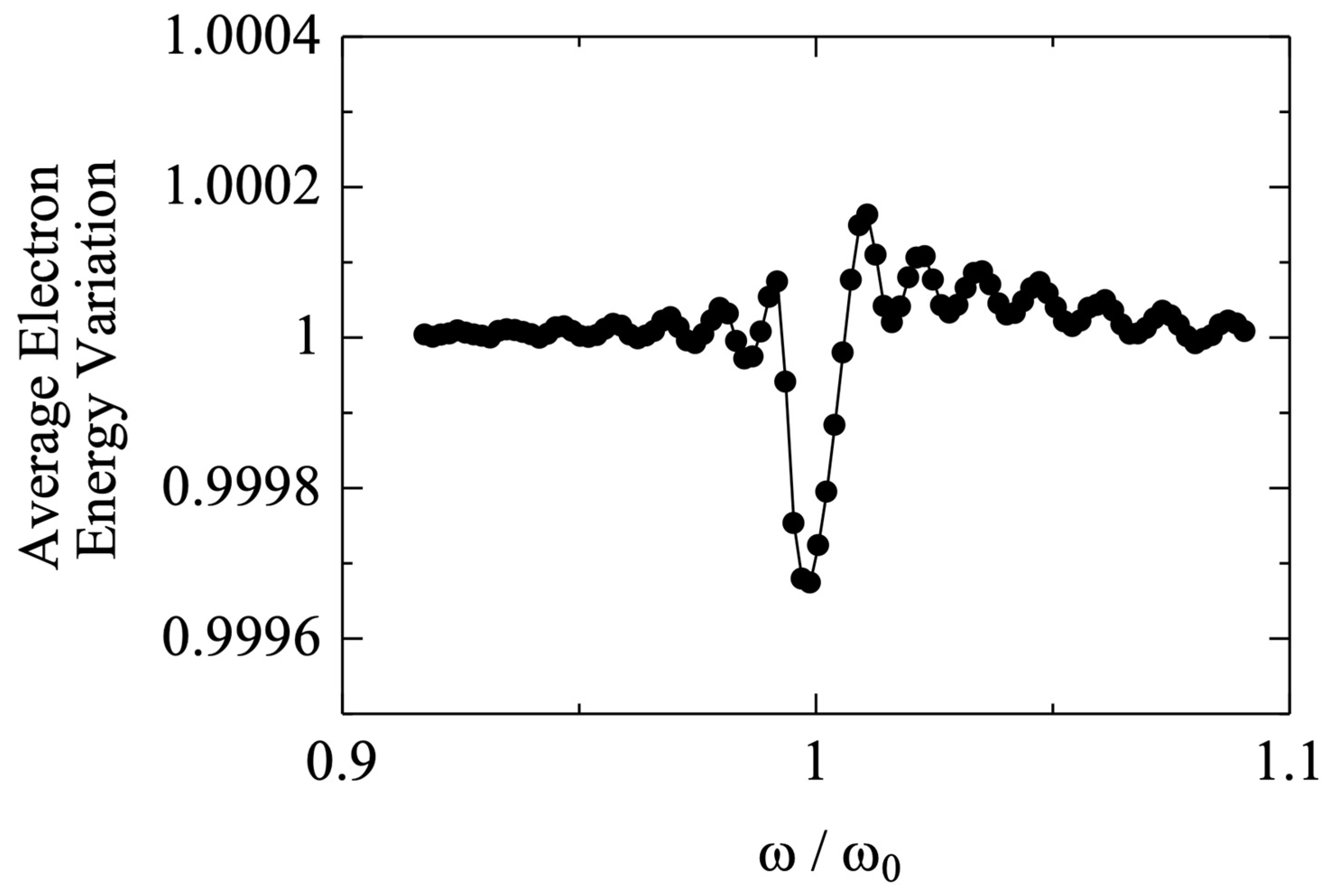

To further confirm the interaction process, the oscillating frequency of the apply voltage has been changed from 0.9ω

0 to 1.1ω

0, where ω

0 is the frequency of virtual cathode oscillation, and the results are shown in

Figure 10. The relative phase between two oscillations is the same as

Figure 9, although the phase relation does not matter much in the case of different frequencies. From

Figure 10, we see that the oscillating field can extract energy from the modulated beam only when their frequencies match with each other. Although this conclusion looks obvious, it may tell us how microwaves are generated in most virtual cathode oscillators.

It is noted that, in a real virtual cathode oscillator, in contrast to an amplifier, we do not have control over either the frequency or the phase relation, at least for the small-signal regime. The dominating wave frequency should be the same as that of the beam modulation and the phase relation should stay optimum before saturation occurs.

4. The Relation Between Frequency and Efficiency

In the last section, considered an independent virtual cathode that oscillates in the background of an oscillating electric field. Under favorable conditions, which means an identical frequency and optimum phase relation between the two oscillations, the electron beam can yield energy to the electromagnetic field, through a process that is physically consistent and quantitatively confirmed.

If the phenomena described in the last section is what is really behind the beam-field interaction in virtual cathode oscillators, we only need to increase the field intensity and try to extract more energy from the electron beam. Of course, in a real device, it is the extracted energy from the electron beam that feeds the electromagnetic field and increases its intensity.

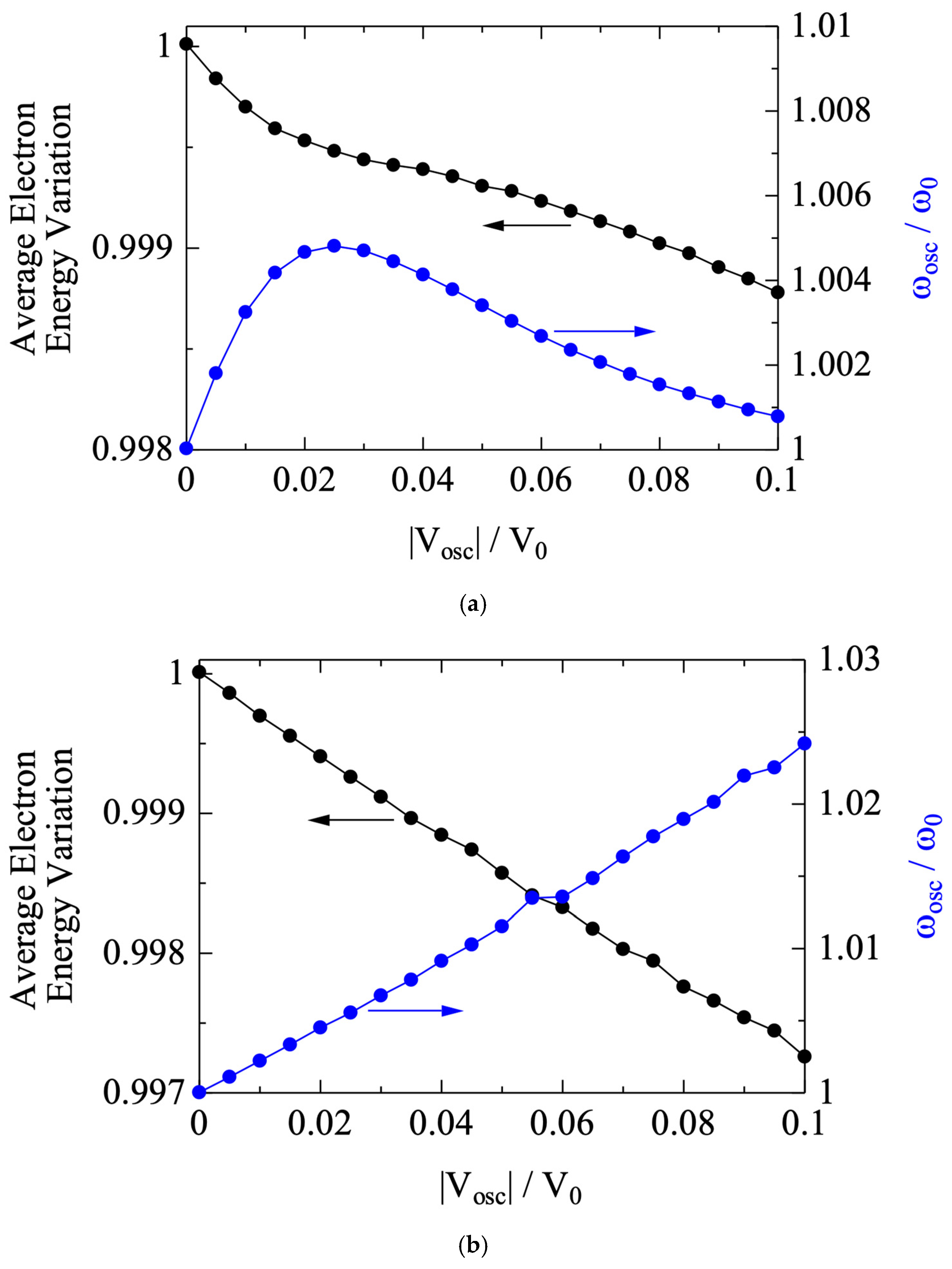

Equation (11) predicts that the energy loss of the electron beam, which is considered to be equivalent to the energy gain of the electromagnetic field, should be proportional to the amplitude of the oscillating field. Our first attempt is to confirm this dependency using one-dimensional simulation.

Figure 11a shows the simulation results obtained with different values of field intensity. The oscillation frequency of the externally applied voltage has been kept constant, which is that of virtual cathode oscillation at |V

osc| = 0, and the phase relation has been kept optimum for energy extraction from the electron beam. The average electron energy variation in the reflected beam is plotted by the black dots, and the frequency of the virtual cathode oscillation is plotted by the blue dots. It is seen from

Figure 11a that the electron energy tends to drop at the beginning, but soon its dependency on the field intensity departs from the linear relation. Meanwhile, the frequency of the virtual cathode oscillation started to increase at the beginning and then fell back to the original value.

It is noted that, as the field intensity increases, we can no longer assume an independent virtual cathode. In other words, the externally applied oscillating field may act on the virtual cathode and change its behavior. From

Figure 11a, it looks as if the frequency of virtual cathode oscillation may have increased at the beginning, when the field intensity started to increase. It fell back to its original value only because the field oscillation frequency was kept constant and, as the field intensity increased, it eventually dominated the process and forced the virtual cathode to oscillate at the same frequency. To confirm this hypothesis, the frequency of the applied field has been changed accordingly, following that of the virtual cathode oscillation. Of course, in a real device, the field frequency should always follow that of the beam oscillation because the field is a result of the beam oscillation, at least in most cases.

Figure 11b shows the simulation results obtained with different values of field intensity, of which the oscillation frequency has been kept the same as that of virtual cathode oscillation. In contrast to that shown in

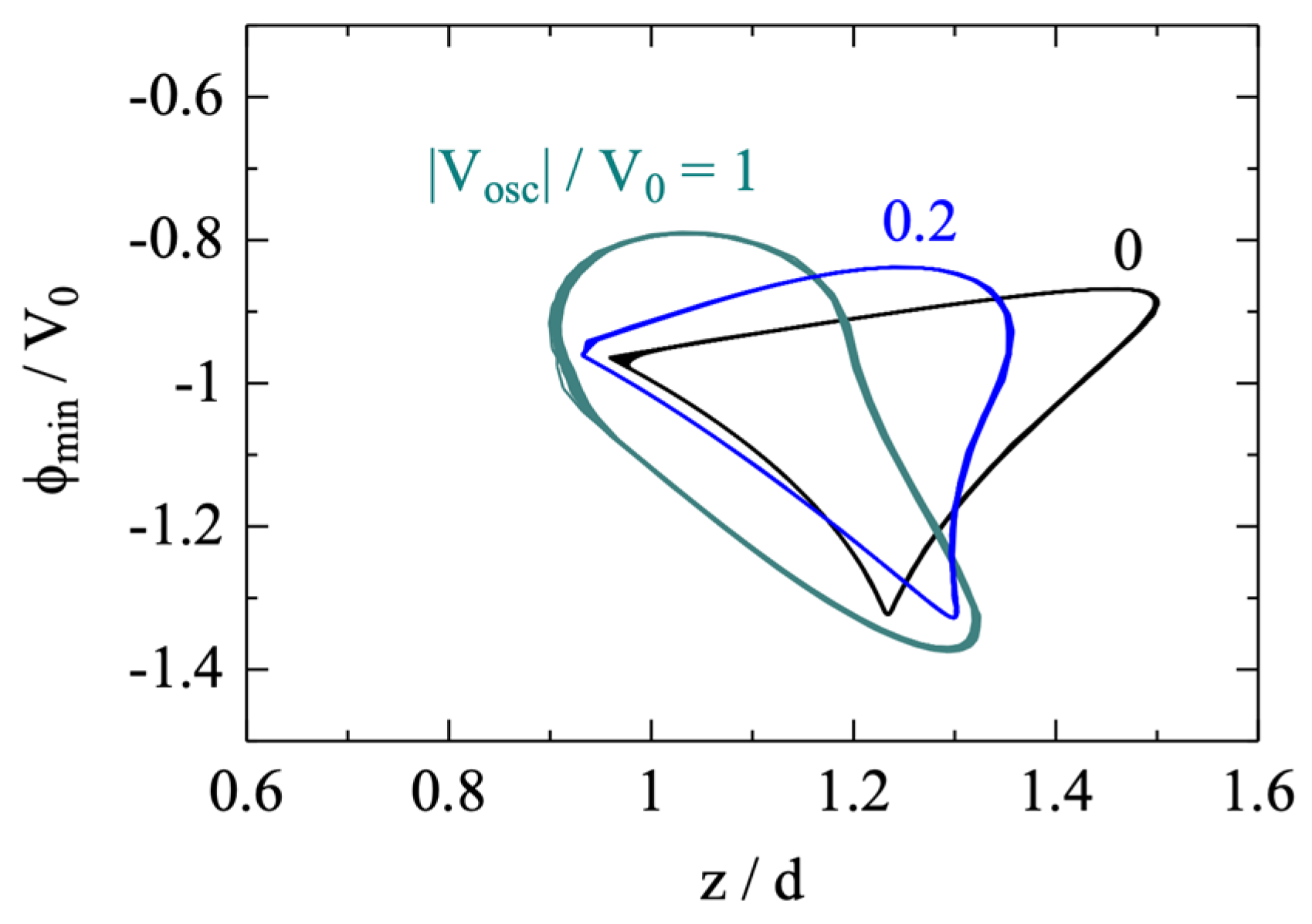

Figure 11a, we see an almost linear increase in beam energy variation and an increase in oscillation frequency.

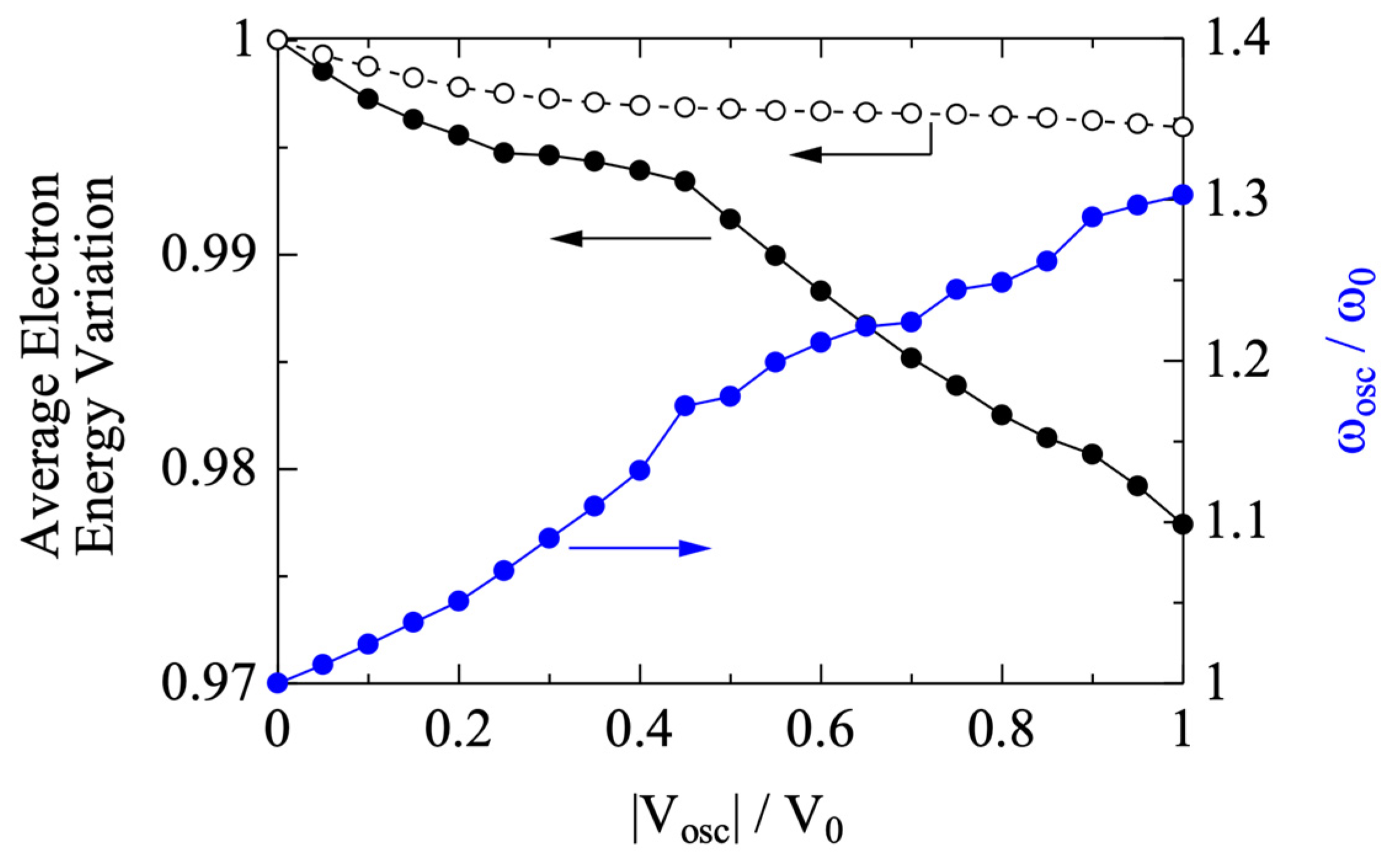

Figure 12 shows the simulation results obtained with the field intensity further increased. It is basically an extension of

Figure 11 and the result of the electron energy obtained with a fixed field-oscillation frequency is plotted by white dots. At the voltage oscillation amplitude that equals V

0, the electron beam dropped its energy by about 2%. This value is close to that of the microwave efficiency reported by many experimental studies. On the other hand, it is seen from

Figure 12 that the oscillation frequency has increased by about 30% at that point.

The direct conclusion from

Figure 12 is that, if we want to increase microwave efficiency, we just need to increase the intensity of the electromagnetic field that interacts with the electron beam. However, this strategy comes with a condition, which requires that the frequency of the field oscillation must follow that of the virtual cathode oscillation. The problem is that we cannot achieve both of them well enough at the same time.

Let us see how this dilemma plays out in an imaginary device. To increase the electromagnetic field intensity, we can use a resonant cavity, such as that shown in

Figure 6a. If the cavity’s Q value is high enough, we can expect that the virtual cathode oscillation eventually builds a strong electromagnetic field in it. However, the higher the Q value is, the narrower the resonant bandwidth becomes. As soon as the virtual cathode oscillation moves out of this frequency range, which is bound to happen according to

Figure 12, the field intensity stops growing. On the other hand, if the cavity resonant frequency was set to match with that corresponding to a higher field intensity, the field would not grow in the first place, as can be seen from

Figure 10, because the field grows from virtually zero in oscillators. It is unfortunate that the resonant frequency cannot be changed without changing the cavity structure. What we can do is to have a wider one that can cover a certain range of frequency variation of the virtual cathode oscillation, which also means a lower Q value and, therefore, a lower field intensity.

It might be interesting to find out why the virtual cathode oscillation frequency increases as the field intensity is increased, as seen in

Figure 12.

Figure 13 shows the simulation results of the trajectories of the potential minimum obtained with different field intensities. It is seen that, as the field oscillation amplitude is increased, the virtual cathode tends to move closer toward the injection plane. The closer the virtual cathode is, the shorter it takes for the electrons to reach the virtual cathode from the injection plane. Although this analysis does not provide a quantitative explanation for the shift in oscillation frequency, it has clearly shown the effect of the externally applied field on the behavior of the virtual cathode. Given the difference seen in

Figure 13, it would be a surprise if the oscillation frequency had not changed.

5. Conclusions and Discussions

In this tutorial article, the interaction process between the electron beam and electromagnetic field in a virtual cathode oscillator was studied by using numerical simulations. It is assumed that the interaction happens mostly in the area between the virtual cathode and the injection plane and it occurs between the reflected electron beam and the electric field component of the electromagnetic wave. Using a simplified one-dimensional model, this interaction has been observed and investigated in detail by means of evaluating the energy loss of the electron beam.

With the understanding obtained in this article, the microwave generation process in a virtual cathode oscillator is generally described as follows. When an electron beam is injected into a space and the beam current exceeds its space-charge-limited current, a virtual cathode is formed and it oscillates due to its intrinsic instability. The oscillation creates beam current modulation which emits electromagnetic radiation. The conductive boundary of the space supports an electromagnetic mode that interacts with the electron beam, especially in the area between the virtual cathode and the injection plane. This interaction results in net energy transfer from the electron beam to the electromagnetic field, resulting in further field enhancement. The field stops growing when its gain is balanced by the microwave extraction from the system.

To increase the microwave output, we need to increase the microwave gain. To increase the microwave gain, we need to increase the field intensity around the virtual cathode, and this is the difficult part because the oscillation frequency of the virtual cathode moves when the electromagnetic field grows. This problem leads us to a trade-off between building a strong field and covering a wide frequency range. The electromagnetics apparently do not allow us to do both, because cavity Q is inversely proportional to its bandwidth.

Therefore, in most experimental devices, we achieve a relatively low microwave efficiency because of the relatively low field feedback to the virtual cathode. Even though we tried to enhance the field by using some resonant structures, the frequency of virtual cathode oscillation may leave the resonance as soon as the field grows. This also explains the relatively unstable output frequency from the virtual cathode oscillator, because the frequency depends on the field intensity, even for constant electron energy and current density.