1. Introduction

Silicon is the most important semiconductor material used in photovoltaic cells, electronic devices, and energy storage devices [

1,

2,

3]. Currently, Si is produced by carbothermic reduction of SiO

2 in a submerged arc furnace at 1700 °C or above [

4]. The Si produced from this process is called metallurgical-grade silicon (MG-Si) and has a purity of around 98–99%. Thus, to obtain high-purity silicon (≥99.9999 wt.%), MG-Si needs to be further purified using the Siemens method, a process that is highly energy-intensive. An alternative method would be to produce Si in molten salts electrochemically. Chloride melts have been extensively used in Si electrodeposition on various substrates [

5]. High-purity Si (99.9999 wt.%) with different morphologies can be electrodeposited in CaCl

2-CaO melts with a SiO

2 precursor on a graphite substrate [

6]. In most cases, the anode material used for the Si electrodeposition is graphite [

7]. Use of graphite would mean that the oxygen ions released during the reaction would react with the carbon, resulting in the release of CO or CO

2 gas. Moreover, the CO

2 gas generated at the anode could partially dissolve in the electrolyte and be reduced at the cathode (reaction 1). This would lead to cathode product impurity, reduce the current efficiency, and increase energy consumption [

8].

CO

2 emissions can be avoided by replacing the carbon anode with a non-consumable oxygen-evolving anode. Reaction 2 would occur at the anode surface if inert anodes were used. A lot of different materials, including oxides, metal-based alloys, and precious metals have been tested as anodes in CaCl

2-based melts, and they have shown stability during electrolysis [

9,

10,

11]. However, none of them have been used in Si electrolysis. Tin oxide has demonstrated stable anode behaviour in LiCl-KCl melts [

12]. SnO

2 has shown promising performance in CaCl

2-NaCl-CaO-AgCl during Ag electrowinning at 680 °C [

13]. SnO

2-based anodes showed stability in highly corrosive cryolite melt during aluminium electrolysis [

14]. Recently, Wang et al. [

15] investigated SnO

2 anode behaviour in a NaCl-KCl-based melt at 750 °C, and found that SnO

2 exhibited stable anode behaviour. During galvanostatic polarisation, the drift in anodic potential was limited, indicating stability.

Pure CaCl

2 melt (containing CaO and SiO

2) has been extensively studied in Si electrodeposition, and has been well documented [

16]. Adding NaCl to the CaCl

2-based melt would reduce the liquidus temperature and improve the ionic conductivity of the mixture [

17]. Eutectic CaCl

2-NaCl melt (52 mol%:48 mol%) has a liquidus temperature of 512.8 °C [

18], which is an advantageous parameter as the anode (primarily metallic) can operate for longer durations without dissolution. The role of CaO would be to supply O

2− to the melt, which would help to generate silicate ions (reaction 3) and, at the same time, provide O

2− to anodes for the oxygen evolution reaction (reaction 2), thereby preventing Cl

2 evolution and avoiding the continuous dissolution of anode material.

In this present paper, we examine the electrochemical behaviour of Pt, graphite, and tin oxide electrodes in CaCl2-NaCl-CaO-SiO2 melts. Electrochemical methods, including linear sweep voltammetry (LSV), cyclic voltammetry (CV), and chronoamperometry (CA), were used to examine the anode behaviour of tin oxide. SEM and EDS were performed on the film deposited during electrolysis on the cathode and the tin oxide anode.

2. Experimental Section

Electrochemical measurements were obtained using a standard three-electrode cell under a N

2 atmosphere. Three electrode materials were tested: platinum, graphite, and tin oxide. The counter electrode was a graphite rod, and the reference electrode was a Ag wire immersed in a mullite tube containing 90 wt.% (CaCl

2 (90 mol%)–NaCl (10 mol%))-10 wt.% AgCl (a similar type of reference electrode was employed in Haarberg et al. [

12]). Analytical-grade CaCl

2, NaCl, CaO, and SiO

2 (supplied by Carl Roth GmbH & Co., Karlsruhe, Germany) was used in this study. All the salts were dried at 200 °C to remove moisture. The salts were then transferred to a graphite crucible, which also acted as an electrochemical cell. The crucible containing the salts was then transferred to a vertical furnace and heated at 300 °C in a nitrogen atmosphere for 18 h. The furnace temperature was raised to achieve the melt temperature of 850 °C (the working temperature). The electrolyte (with a total mass of 200 g) consisted of 90 mol% CaCl

2 and 10 mol% NaCl. After melting, 2 wt.% CaO and 2.2 wt.% SiO

2 (CaO:SiO

2 = 1 mol ratio) were added to the melt. The electrolyte temperature was monitored using a K-type thermocouple and maintained at 850 °C (±2 °C) throughout the experiments. The electrodes were polished with fine-grade SiC paper and cleaned with ethanol before being immersed in the electrolyte.

Electrochemical measurements were performed using an Ivium XP40 potentiostat, controlled by Iviumsoft. Before the studies, pre-electrolysis was performed using two graphite electrodes at a 2.5 V cell voltage to remove the impurities present in the electrolyte. Electrochemical techniques, including cyclic voltammetry, linear sweep voltammetry, and chronoamperometry were employed to study the anodic behaviour of Pt, graphite, and SnO

2 electrodes. The SnO

2 and graphite electrodes were rod-shaped, with radii of 0.4 cm and 0.25 cm, respectively, while the Pt electrode was a wire with a radius of 0.05 cm. The corresponding apparent active surface areas of electrodes during the electrochemical measurements (CV, LSV, and CA) were 1.25 cm

2 (SnO

2), 0.981 cm

2 (graphite), and 0.408 cm

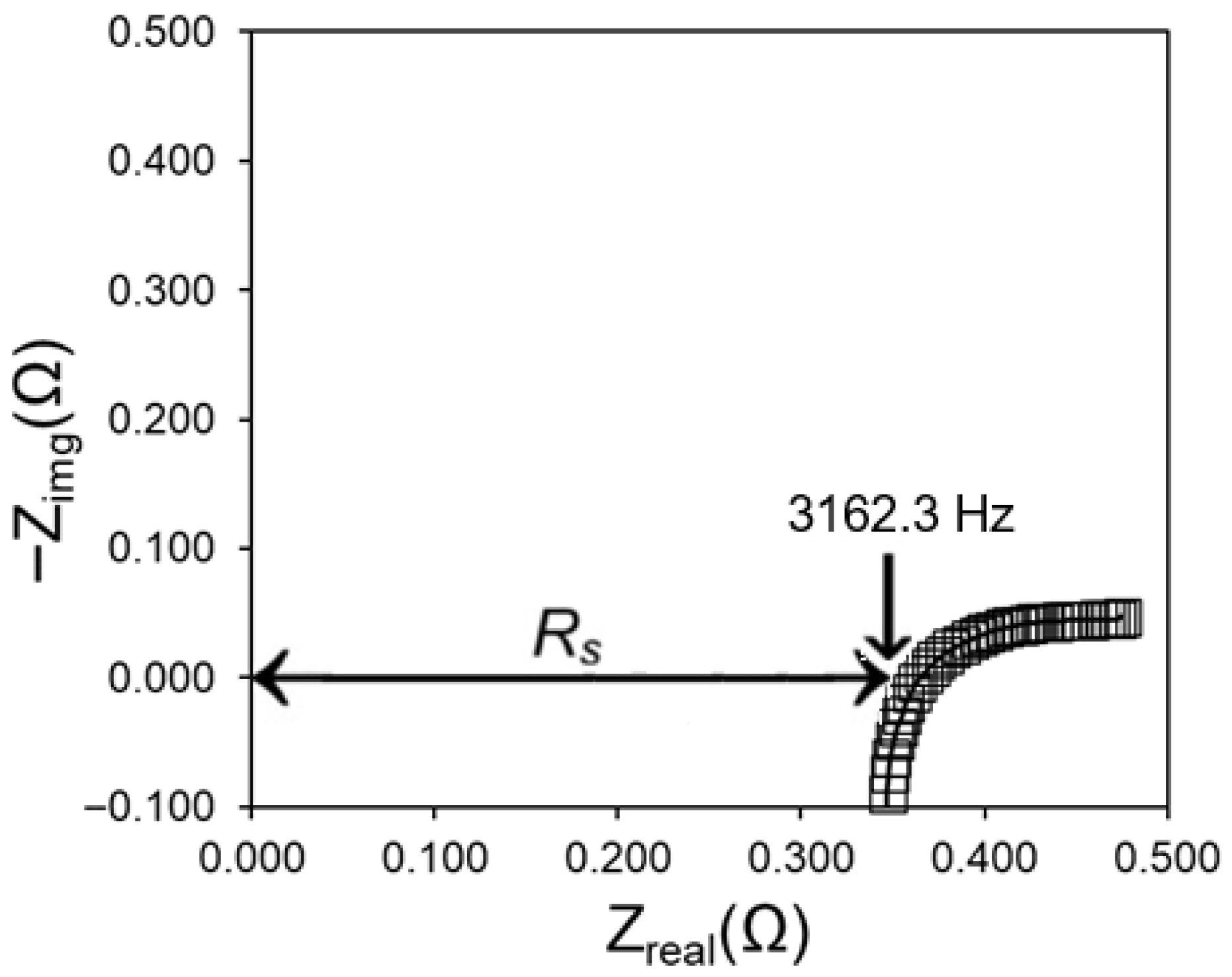

2 (Pt), respectively. All these measurements were IR-compensated, where the electrolyte resistance was determined using impedance spectroscopy. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was performed at open-circuit potential to determine the uncompensated resistance (R

s). The measurements were carried out in a frequency range of 100 kHz–1 Hz with a 10 mV perturbation. The Nyquist plot obtained while using a SnO

2 electrode is shown in

Figure 1. The total ohmic drop is around 0.365 Ω, which accounts for the electrolyte, connection, and reference-junction resistances. The ohmic drop was compensated for by 85% during all the subsequent measurements. The R

s values varied when Pt and graphite electrodes were used as the current leads/connections, and when the electrode geometries differed. Electrolysis was performed using a tin oxide anode and a graphite cathode for 8 h in potentiostatic mode (two-electrode configuration) with a cell voltage of 2.5 V. The active surface areas of the SnO

2 anode and the graphite cathode during electrolysis were 2.51 cm

2 and 2.1 cm

2, respectively. The cell voltage was set to 2.5 V because calcium co-deposition occurs at 2.7 V (at 850 °C) [

19]. The electrolysis was performed using a two-electrode system, with a SnO

2 anode and a graphite cathode. SnO

2 was electrically connected using a Ni wire which was wrapped around the SnO

2 cylindrical rod. After the electrolysis, the cathode was cooled to room temperature under an N

2 atmosphere and rinsed with deionised water to remove the salts present on the cathode surface. Si deposited on the graphite cathode and the SnO

2 anode was examined using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Carl Zeiss AG Supra 25, with an accelerating voltage of 20 kV) coupled with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS, Oxford Instruments, Osaka, Japan) for elemental analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

Alkali metal halide molten salts have wide electrochemical windows, high electrical conductivity, and low melting points, making them potential electrolyte mixtures for metal production. Here, we utilise HSC Chemistry software to calculate the Gibbs free energy for the possible reactions that occur during electrolysis. The theoretical standard reversible decomposition potentials of the compounds present in the electrolyte mixture can be estimated using the following equation:

where

is the standard potential (V), Δ

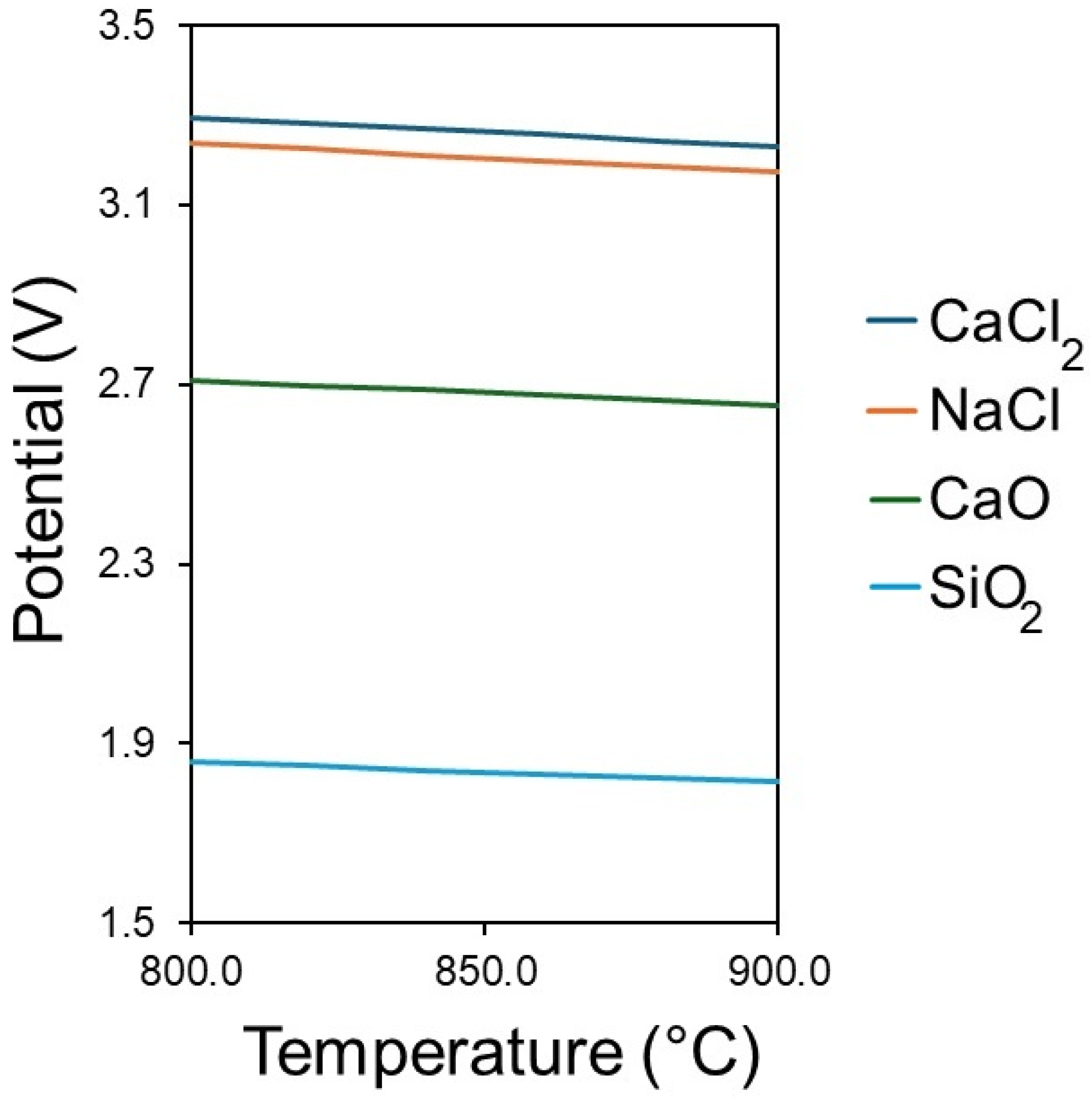

GΘ is the standard Gibbs free energy (kJ/mol), n is the number of electrons transferred during the reaction, and F is Faraday’s constant (96,485 C/mol). The theoretical decomposition potentials of salts and SiO

2 between the temperatures of 800 °C and 900 °C are shown in

Figure 2. The decomposition potentials decrease with an increase in the electrolyte temperature. The decomposition potential of SiO

2 is 1.82 V at 850 °C; this is lower than the decomposition potentials of NaCl and CaCl

2 salts, which are 3.21 V and 3.26 V, respectively. The decomposition potential of CaO is 2.68 V; therefore, the cell voltage should not exceed 2.68 V, or co-deposition of Ca along with Si will occur. This means that the practical electrochemical window is 2.68 V.

The potentials in

Figure 2 are standard thermodynamic decomposition values derived from ΔG°, and they assume pure phases and standard states. In the mixed CaCl

2–NaCl–CaO–SiO

2 system at 850 °C, the measurable onset potentials depend on interfacial kinetics, mass transport, activities, and possible phase changes. Therefore, experimental onsets may deviate from the baselines. Accordingly,

Figure 2 should be treated as a thermodynamic reference, whereas the polarisation data (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) reflect the kinetics under experimental conditions.

Before examining the polarisation behaviour, the ohmic resistance was estimated using the EIS method (see

Figure 1). All the measurements hereafter are IR-compensated by 85%.

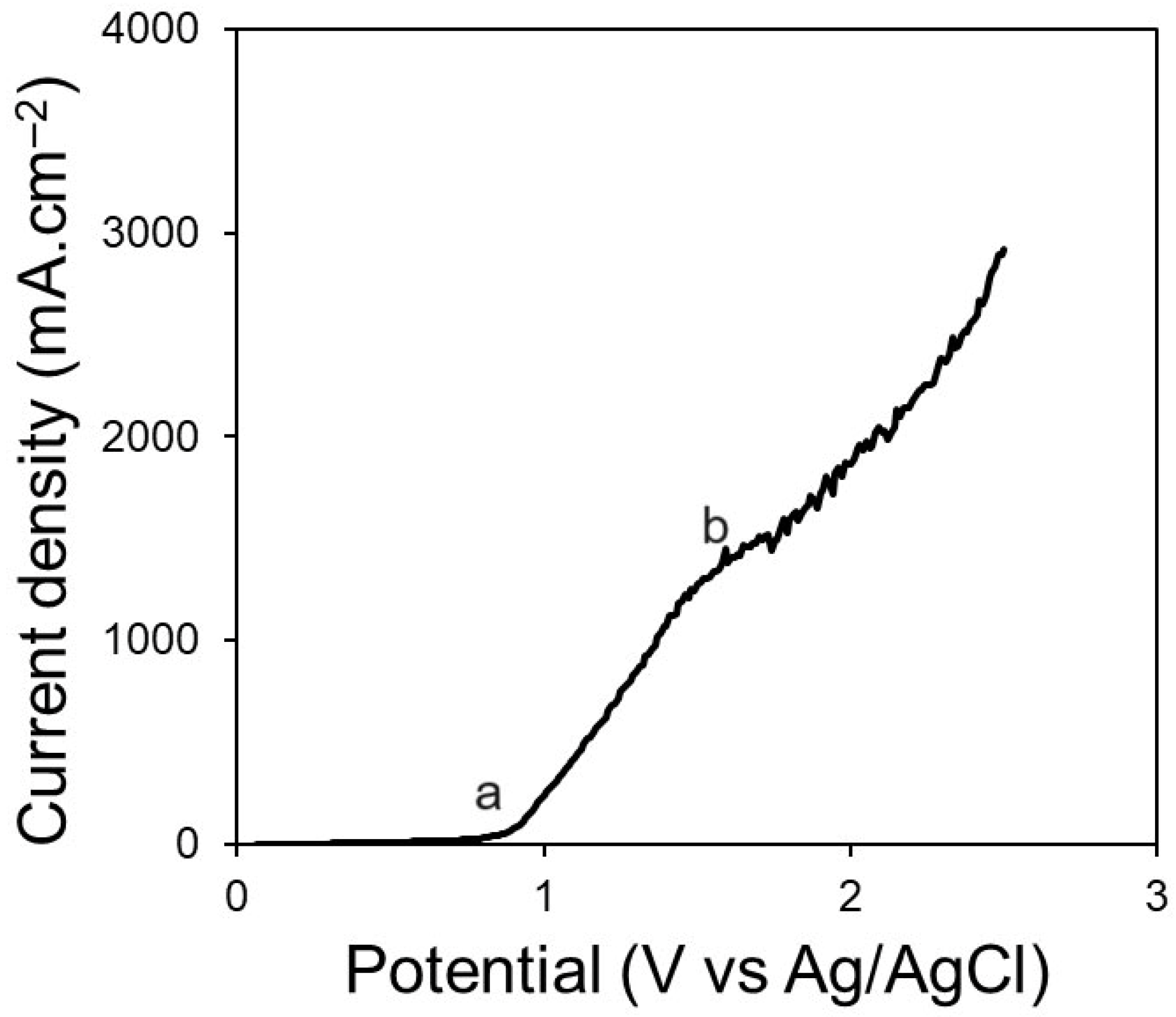

Figure 3 represents the polarisation curve obtained for the Pt electrode in CaCl

2–NaCl–CaO–SiO

2 at 850 °C. The linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) was run between the OCP (vs. Ag/AgCl) and 2.5 V (vs. Ag/AgCl). No peaks were seen on the voltammogram recorded on Pt. A significant increase in current can be observed at 0.85 V (point a) which is associated with oxygen evolution. The O

2 evolution is between points a and b. Point b (at 1.65 V vs. Ag/AgCl) is the onset potential of Cl

2 evolution on Pt. Thus, the anodic potential should not exceed 1.65 V, as Cl

2 gas evolution occurs, indicating the decomposition of chloride salt compounds. A similar phenomenon, where Cl

2 evolution is followed by O

2 evolution, was observed by Hu et al. [

20] and by Mukherjee and Kumaresan [

21].

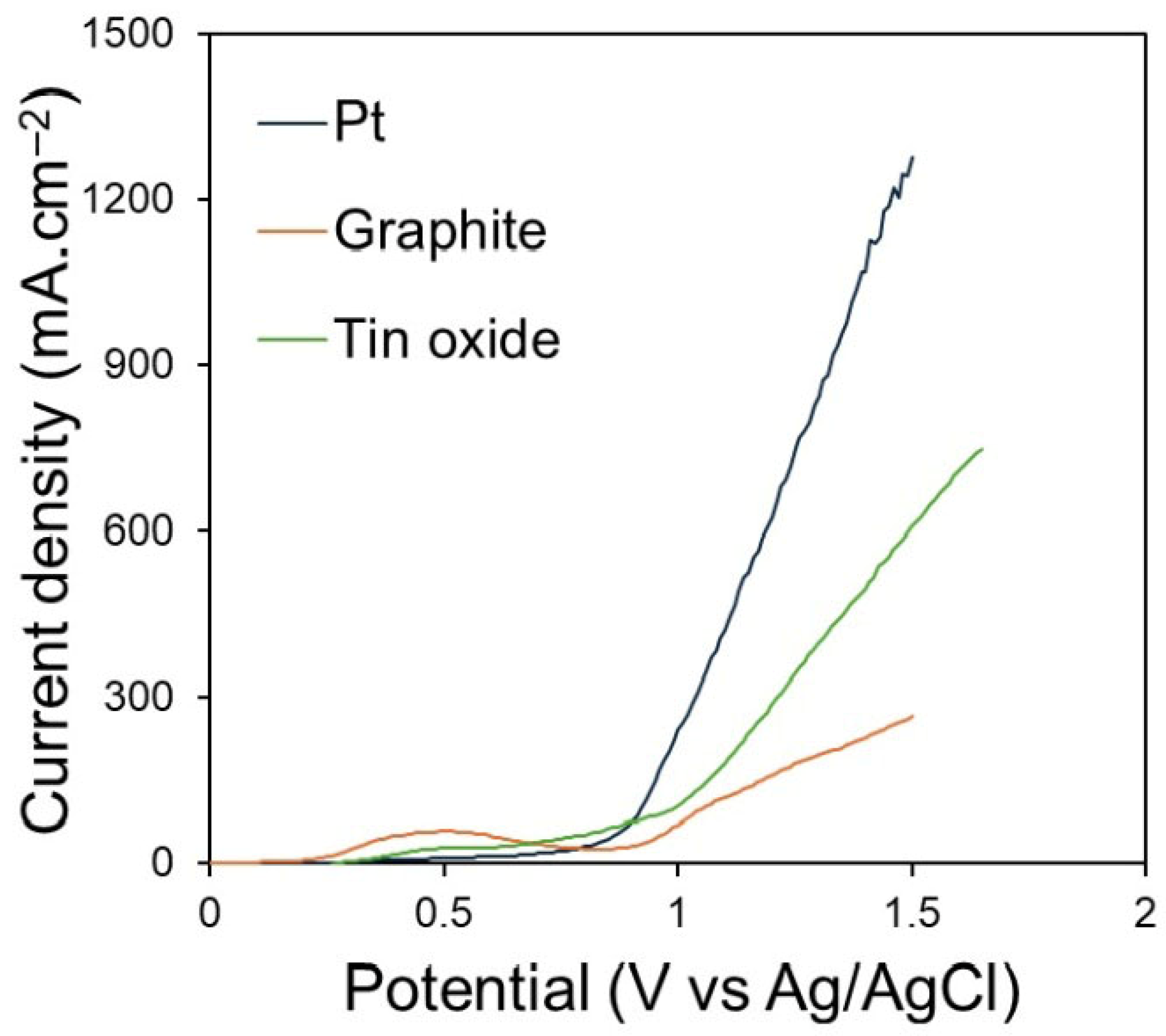

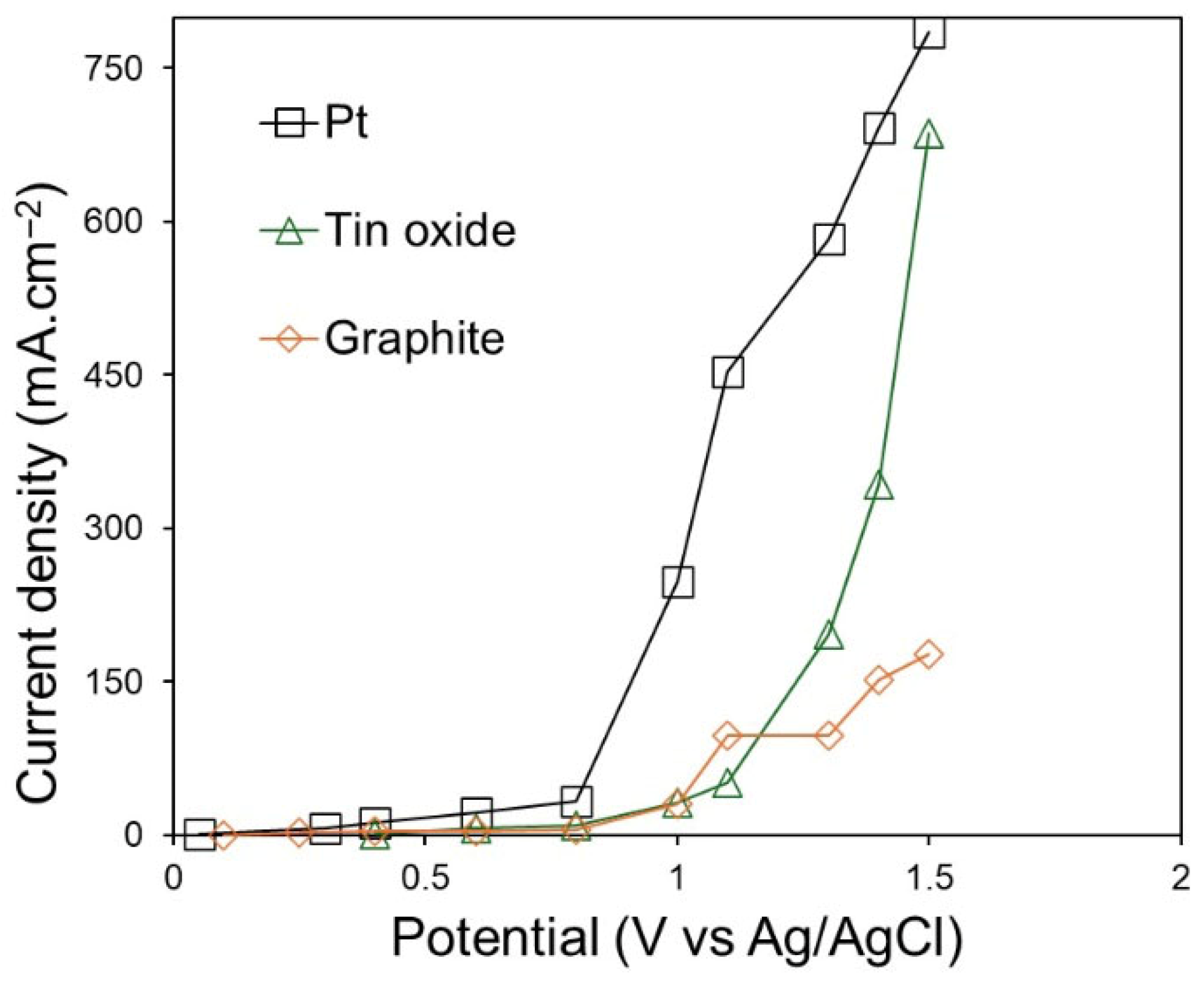

Figure 4 shows the polarisation curves obtained on Pt, graphite, and SnO

2 electrodes in CaCl

2–NaCl–CaO–SiO

2 at 850 °C with a sweep rate of 50 mV∙s

−1. The polarisation was performed between the OCP and 1.5 V (vs. Ag/AgCl). The polarisation was not performed beyond 1.5 V, to avoid Cl

2 evolution. The shape of the polarisation curve of each electrode reflects its intrinsic electrochemical behaviour and gas evolution kinetics. On the Pt electrode, no peaks were observed, and the O

2 started at 0.85 V. A smooth and rapid increase in the current density is characteristic of facile charge transfer on Pt and the absence of passivation. On the graphite electrode, the current begins to rise at 0.25 V, which is attributed to the formation of CO and/or CO

2. An increase in current from 0.8 V on the graphite electrode is related to the continuous evolution of CO and/or CO

2 gas, resulting in electrode consumption. The irregular curve shape at high potentials reflects the lowering of the active surface area due to bubble coverage on the graphite. A small anodic peak at 0.5 V is observed on the SnO

2 electrode. This is related to oxidisation of O

2− ions or adsorption of O. From 1.0 V, a steep increase in anodic current on SnO

2 can be observed. This is related to oxygen evolution. The broader transition region and delayed onset of oxygen evolution potential (approximately 0.2 V compared to Pt) indicate the slower interfacial kinetics and lower electronic conductivity of SnO

2 compared to Pt. According to the polarisation curves, the overpotentials for oxygen evolution are higher for SnO

2 compared to Pt, indicating that the catalytic activity of the former is limited by charge transfer processes rather than surface area effects. Thus, more energy is consumed as a function of current density when using SnO

2 anodes during electrolysis.

Figure 5 shows the steady-state polarisation (SSP) curves obtained for Pt, SnO

2 and graphite electrodes in CaCl

2–NaCl–CaO–SiO

2 at 850 °C. The onset potential for oxygen evolution (vs. Ag/AgCl) on the Pt electrode is 0.8 V. The low current densities observed before oxygen evolution suggest that the Pt is stable without any dissolution. Pt is an ideal and stable electrode for the oxygen evolution reaction; however, the main drawback of Pt is its cost and scarcity. Similar to the Pt electrode, SnO

2 produces O

2 gas. Oxygen evolution on SnO

2 proceeds at 1.1 V (vs. Ag/AgCl), which is due to SnO

2’s semiconducting nature and lower electrical conductivity compared to Pt. SnO

2 remains stable, like the Pt anode, before the oxygen evolution reaction, as no significant currents are passed (suggesting no dissolution of SnO

2). The oxygen evolution reaction on SnO

2 follows a multi-step mechanism (oxide-ion adsorption, electron transfer, O–O coupling, O

2 desorption), with the rate likely limited by the O

2 diffusion or the O

2-release step at the oxide surface. The steady-state polarisation curve obtained on graphite has a completely different mechanism compared to the other two materials. There are two rate-determining steps, one being the formation of CO (C + O

2− → CO + 2e

−), which happens at lower potentials, and the other being the oxidation of CO to CO

2 (CO + O

2− → CO

2 + 2e

−). Overall, there is continuous consumption of graphite anode during the electrolysis. In both LSV and SSP curves of graphite, an increase in the anodic current density is observed at around 0.9 V (vs. Ag/AgCl), which is related to CO

2 evolution. In general, the potentials required for CO

2 are lower than the potentials required for O

2 evolution (on Pt and SnO

2). This suggests that CO

2 evolution on graphite in this melt composition takes place at high overpotentials.

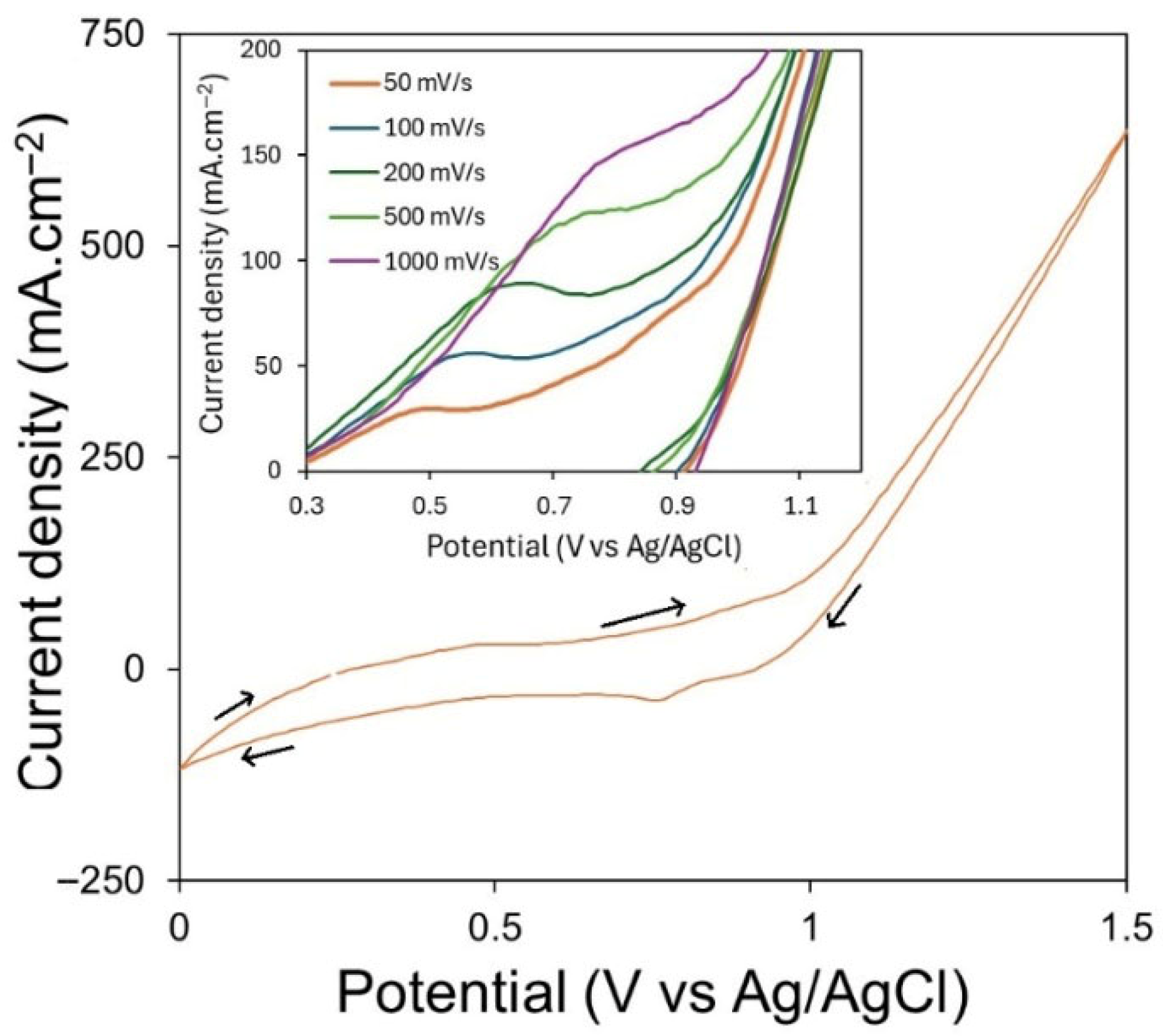

Figure 6 presents the cyclic voltammetry curve obtained for a SnO

2 anode in CaCl

2–NaCl–CaO–SiO

2 at 850 °C. In the inset of

Figure 6, voltammograms obtained with different sweep rates are shown. A single peak was observed at 0.5 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) on SnO

2 during the polarisation. This is likely associated with the adsorption of oxygen ions on the electrode surface (the peak is similar to the one observed on SnO

2 during polarisation). The oxygen evolution onset potential is approximately 0.9 V. It is challenging to define the exact mechanism occurring on the electrode surface. Kvalheim et al. [

22] reported two peaks in CVs obtained on tin oxide in chloride melts, with the first peak being associated with the adsorption of O

2− and the second peak with O

2 evolution. However, the peak associated with oxygen evolution is not observed in this study. At the onset, the peak current (related to O

2− adsorption) increases with an increase in the sweep rate. The peak potential shifts to the positive side, indicating that the reaction associated with this peak is irreversible.

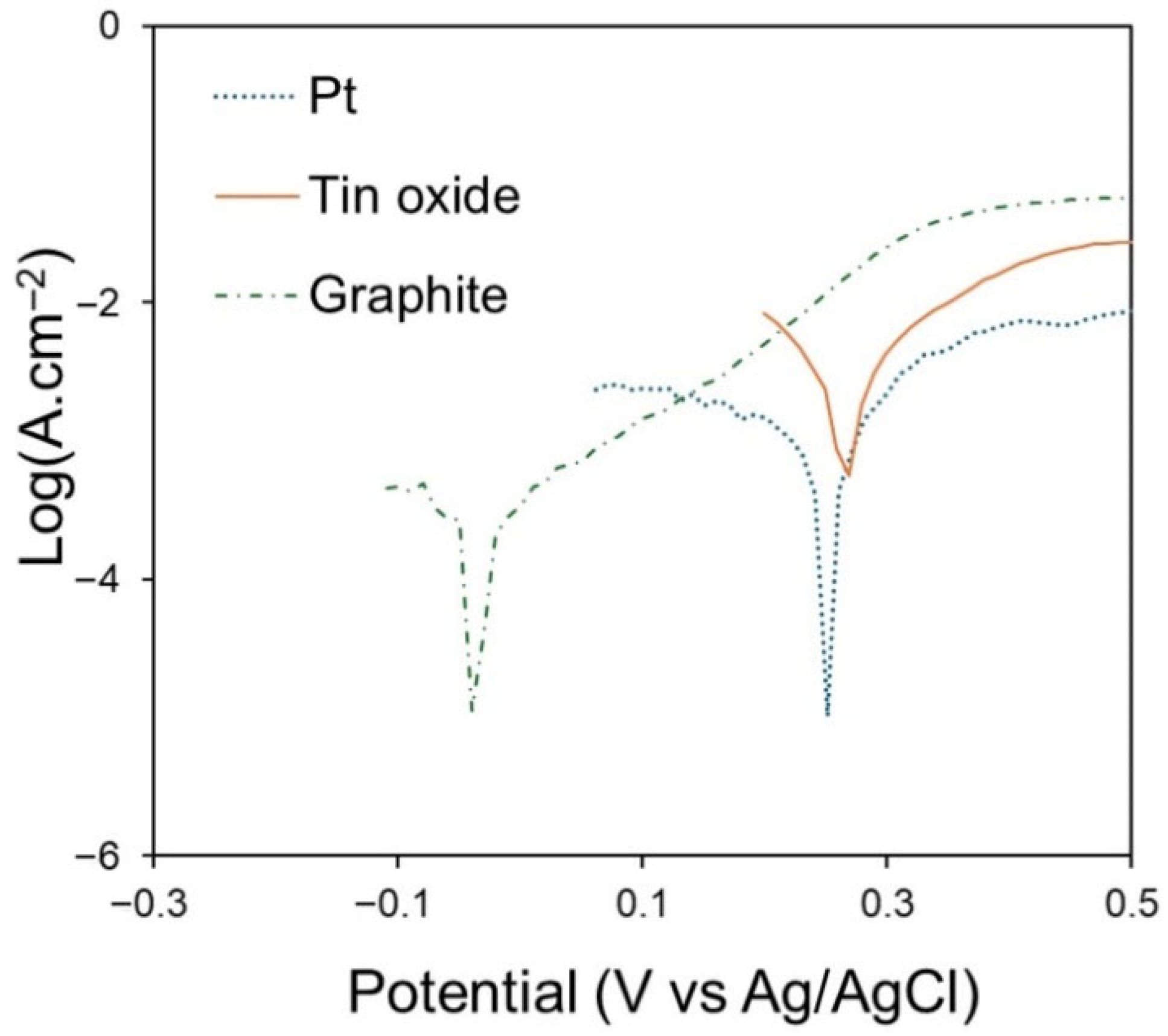

The electrodes were subjected to potentiodynamic polarisation in CaCl

2-NaCl-CaO-SiO

2 melt at 850 °C (50 mV∙s

−1). Tafel plots are shown in

Figure 7. As shown in the plots, the corrosion potentials for graphite, Pt, and SnO

2 are −0.04 V, 0.25 V, and 0.26 V, respectively. SnO

2 exhibits a higher corrosion potential (E

corr) compared to the other two materials. However, the difference in corrosion potential values between Pt and SnO

2 is very small, and the corrosion current densities appear to be significantly lower for the Pt electrode than for the SnO

2 electrode. The corrosion current densities of graphite, SnO

2, and Pt are 0.212 mA∙cm

−2, 1.84 mA∙cm

−2 and 0.796 mA∙cm

−2, respectively. Typically, the corrosion current densities are in the range of µA∙cm

−2, but in this case the values are in mA∙cm

−2 because the polarisation was performed at a higher sweep rate. Nevertheless, the corrosion potentials of the electrode materials remain unchanged, as they are largely independent of the scan rate. The corrosion potential of SnO

2 is more positive than that of graphite, an observation similar to that made by Wang et al. [

15]. The combination of data on corrosion potential and corrosion current densities indicates that the Pt electrode is the most corrosion-resistant material in the CaCl

2–NaCl–CaO–SiO

2 melt, compared to the other two materials, a result which was expected due to its high stability and inertness at high temperatures in molten salts.

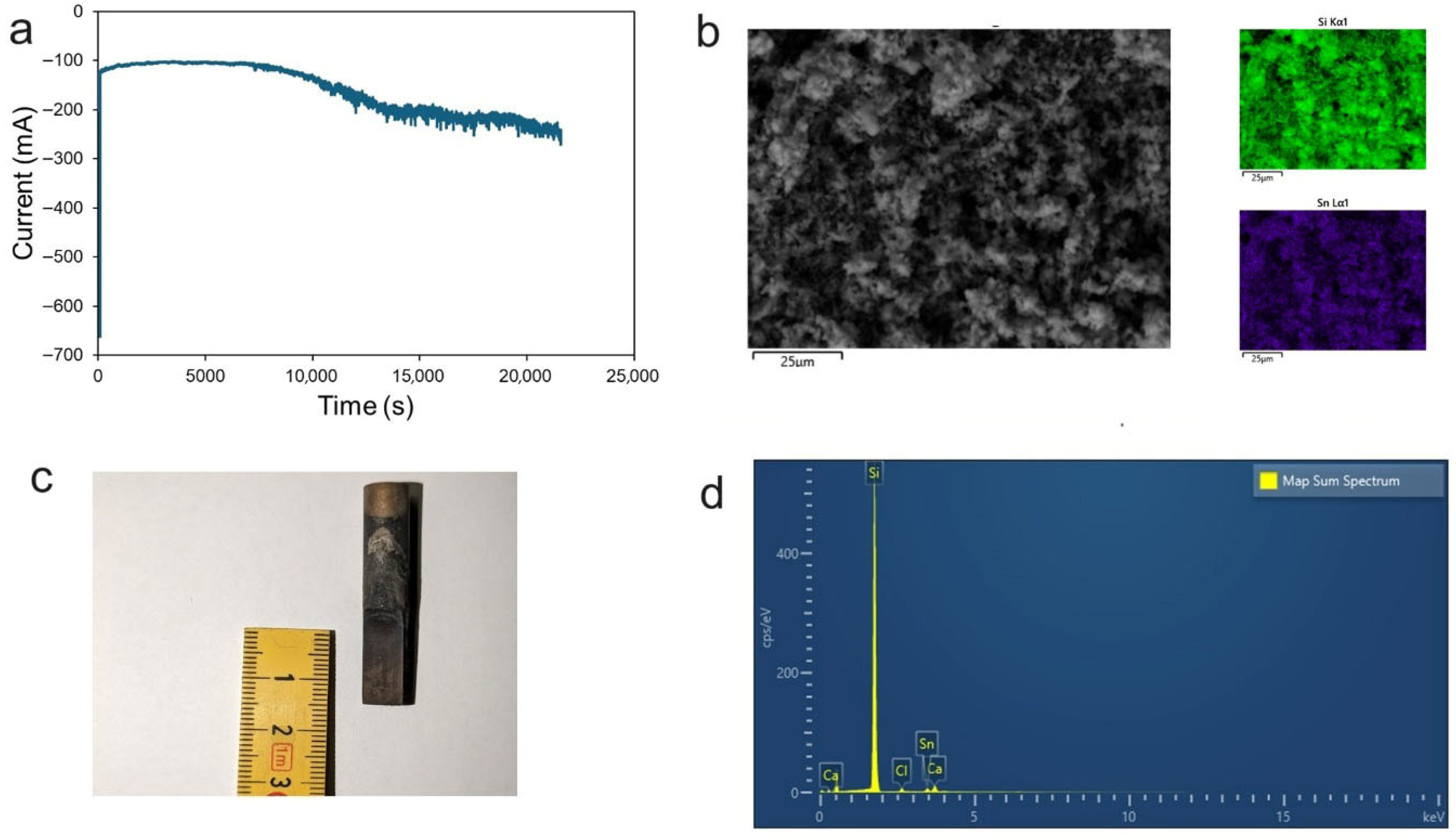

Figure 8a shows the current vs. time plot for the potentiostatic electrolysis at −2.5 V where a SnO

2 anode and a graphite cathode were used. The current passing through the electrode is constant for the first 2 h, after which a continuous increase in the current is observed. There could be a side reaction other than silicon deposition occurring on the cathode. The change in the current could be attributed to either of the following reasons: (a) dissolution of Sn at the anode (contributing to an increase in the current passed); or (b) an increase in the cathode surface due to the deposition of Si.

Figure 8b shows the cathode after 8 h of electrolysis. A thin deposit was formed on the cathode. The SEM images (

Figure 8c) show that the cathode product was in the form of powder.

Figure 8d shows the EDS spectrum of the total area in

Figure 8c. One strong peak is observed, which is related to Si, while three other peaks with low intensity can also be seen, these being related to Ca, Cl, and Sn. The cathode deposit composition, as determined by elemental analysis, was 88.60 wt.%.% Si, 5.80 wt.% Sn, 3.37 wt.% Ca, and 2.22 wt.% Cl. Ca and Cl impurities could be due to the small amounts of electrolyte present in the cathode. A complete removal of Ca and Cl could be easily achieved if the cathode is rinsed for a longer period. An abrupt increase in the current (

Figure 8a) after 2 h of electrolysis could be due to partial Sn dissolution. Silicate ions are preferentially reduced at the cathode; however, an insufficiency of silicate ions in the melt would lead to the partial dissolution of SnO

2. Irrespective of that, SnO

2 anodes can still be used if we want to produce Si-Sn thin films, as Si-Sn thin films can be used as anode material in Li-ion batteries, and they perform better than pure Si anodes [

23]. The cathode product composition was evaluated only using SEM/EDS, which provides reliable information on morphology and major elements. However, detailed phase identification and quantitative analysis were not performed in this study; these shortcomings will be addressed in future work.

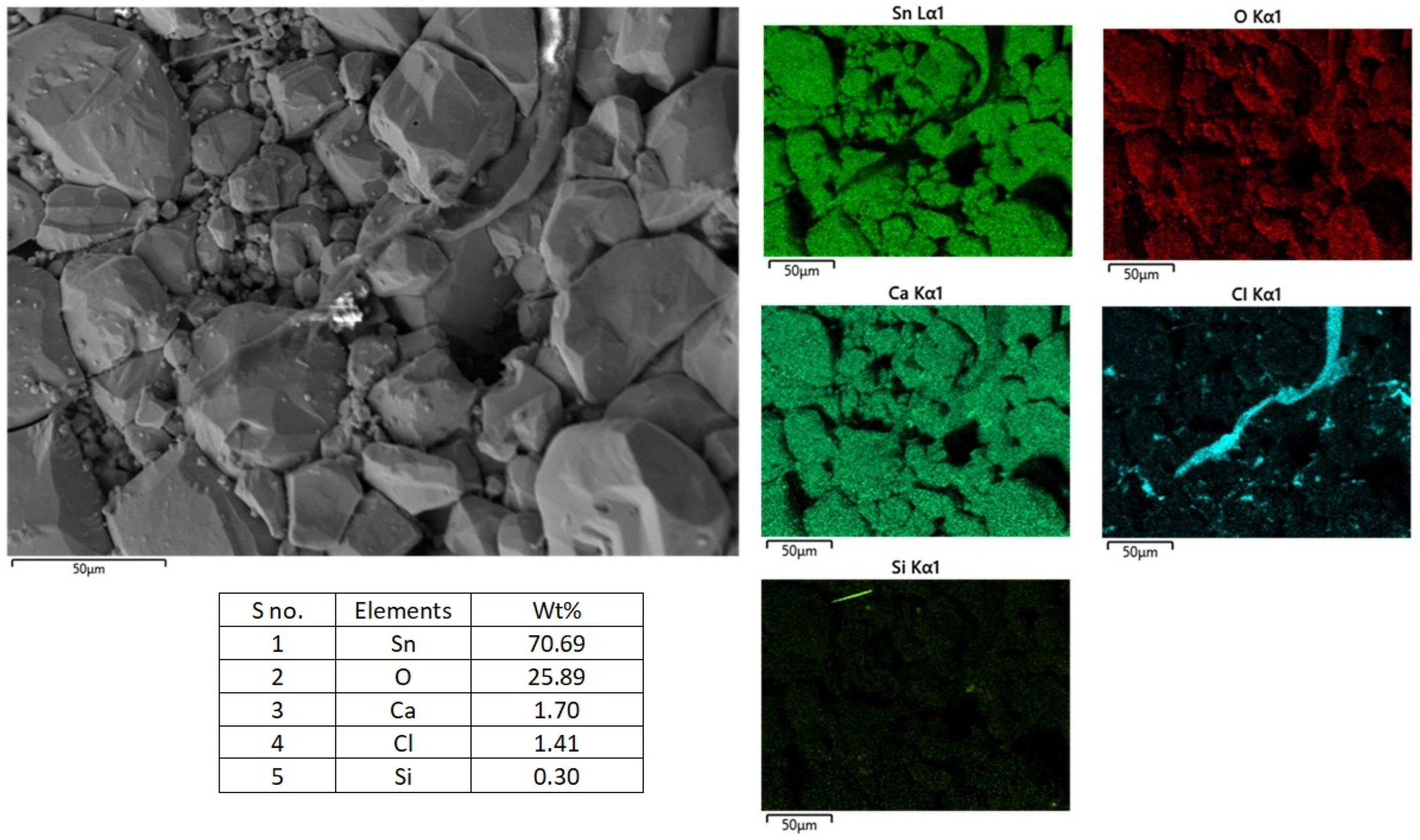

Figure 9 shows the surface SEM image of the SnO

2 anode after 8 h of electrolysis. The SnO

2 remained unchanged in shape but was slightly darker in colour, a similar observation to that made by Haarberg et al. [

12]. The EDS data indicate that the anode primarily consists of Sn (70.69 wt.%) and O (25.89 wt.%), with small amounts of Ca (1.70 wt.%), Cl (1.41 wt.%), and Si (0.30 wt.%). Elemental mapping shows that the tin and oxygen are evenly distributed, consistent with the initial anode composition. Calcium is also evenly distributed. Small amounts of Cl and Si are also seen, with non-uniform distributions. The formation of trace amounts of CaSnO

3 is possible, as there is an even distribution of Ca. However, low Ca content and a lack of strong and localised calcium signals suggest the reaction between CaO and SnO

2 is weak. A stable SnO

2 anode structure indicates that the dissolution of Sn into the melt during the anodic process is slow, and that Sn deposition at the cathode is due to the slow chemical process involving the formation of soluble stannate species (e.g., SnO

32− or SnO

44−). Although the SnO

2 anode maintained its structural integrity after 8 h polarisation, the partial dissolution of Sn and its subsequent deposition at the cathode indicate that SnO

2 is not suitable for preparation of high-purity Si.