1. Introduction

Deep learning has emerged as the dominant paradigm in anomaly detection due to its unique capability to automatically extract features and recognize complex patterns, enabling effective handling of high-dimensional, nonlinear data [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Such methods typically construct a latent representation space of normal data, using deep neural networks and defining decision boundaries through the distribution learning mechanisms of generative models, thereby accurately identifying samples that deviate from normal patterns. This technology has found broad applications in industrial product quality inspection [

1], detection of anomalous network activities [

2], medical health monitoring [

3], and identification of suspicious financial transactions [

4], underscoring its significant research value and practical utility. Nevertheless, current anomaly detection approaches face critical challenges, including high computational complexity on high-dimensional data, high sensitivity to noise, suboptimal detection accuracy, scarcity of anomalous samples, inflexible noise injection strategies that fail to adapt to complex data distributions, and training instability.

Based on whether labeled data are required during training, anomaly detection methods can be categorized into supervised, semi-supervised, and unsupervised learning approaches.

Supervised anomaly detection methods [

5,

6,

7,

8] train models using explicitly labeled normal and anomalous data, achieving high accuracy when sufficient labeled samples are available. Representative approaches include decision tree-based methods [

5], adaptive radius strategies [

6], graph neural network architectures [

7], and multi-domain feature fusion techniques [

8]. These methods demonstrate a strong discriminative capability on balanced datasets [

5,

6] and excel at capturing complex feature patterns and correlations [

7,

8]. However, supervised approaches suffer from poor performance on sparse data [

5], overfitting due to class imbalance [

6], high computational costs [

7], and heavy reliance on abundant labeled defect information [

8], limiting their generalization capability in real-world scenarios where labeled anomalies are scarce.

Semi-supervised anomaly detection methods [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] leverage a small set of labeled samples together with a large pool of unlabeled data to enhance detection accuracy. These approaches employ graph-based augmentation [

9], multi-modal integration strategies [

10], divergence-based distribution quantification [

11], clustering-guided detection [

12], and reinforcement learning optimization [

13]. While semi-supervised methods reduce dependence on labeled data [

9,

11] and improve localization accuracy [

10], they are hindered by high model complexity and parameter sensitivity [

9], instability on complex data [

10,

11], poor performance on non-normal distributions [

12], and computational scalability issues on large datasets [

13].

Unsupervised anomaly detection methods [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33] identify anomalies by analyzing intrinsic data patterns and structures without relying on labels, making them particularly suitable for real-world applications where labeled anomalies are unavailable. The existing unsupervised approaches can be broadly categorized into three groups. Reconstruction-based methods [

14,

15,

16] employ autoencoders and generative models to learn normal data distributions, detecting anomalies through reconstruction errors. These methods demonstrate effectiveness in capturing data manifolds [

15,

16] but suffer from limited generalizability on multimodal datasets [

14], performance degradation on highly complex data [

15], and poor adaptation to imbalanced distributions [

16]. Statistical and distance-based methods [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27] leverage empirical distributions, nearest neighbor relationships, and clustering techniques for anomaly identification. Representative approaches include cumulative distribution function estimation [

17,

19], memory-contrastive learning [

18], density-based detection [

20,

26], internal relative evaluation [

21], graph neural network architectures [

22], attribute-based characterization [

23,

31], mutual information fusion [

24], chain-based connections [

25], and particle swarm optimization [

27]. While these methods achieve high detection accuracy without labels [

17,

19,

20] and demonstrate high computational efficiency [

25], they face limitations including feature independence assumptions, noise sensitivity [

19], high computational complexity on large-scale data [

21,

24,

27], dependence on feature extraction quality [

22], restriction to discrete data [

23], and extensive hyperparameter tuning requirements [

20,

26,

32]. Hybrid and ensemble methods [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33] combine multiple techniques to enhance detection robustness. These approaches integrate turning point analysis [

28], fuzzy rough set theory [

29], autoencoder–SVM fusion [

30], distributed parallelization [

31], density-clustering integration [

32], and vision-language models [

33]. Although hybrid methods improve detection capability [

28,

29] and achieve excellent speed [

30], they struggle with simultaneous detection of multiple anomaly types [

28], poor scalability to large datasets [

29], degraded performance on imbalanced data [

30], susceptibility to noise [

31], and dependence on auxiliary label quality [

33].

In summary, the existing unsupervised anomaly detection methods commonly suffer from insufficient parameter precision, poor robustness to noise, and inadequate generalization—limitations that severely hinder their practical utility in complex real-world scenarios. To address these challenges, this paper proposes an Adaptive Diffusion Adversarial Evolutionary Network (ADAEN) for unsupervised anomaly detection in tabular data.

Notably, the landscape of tabular anomaly detection has been reshaped by breakthroughs in generative AI and sequence modeling. For instance, Livernoche et al. [

34] introduced a diffusion time estimation framework that significantly accelerates inference by directly modeling the diffusion step distribution of anomalies, offering a scalable alternative to traditional iterative denoising. In parallel, Thimonier et al. [

35] leveraged non-parametric Transformers (NPTs) to capture both feature-level and sample-level dependencies via self-attention, effectively identifying contextual anomalies in complex tabular data. More recently, Sattarov et al. [

36] proposed diffusion-scheduled denoising autoencoders, which integrate dynamic noise scheduling with representation learning to enhance robustness against irregular data distributions. Despite these strides, these methods often face challenges in adaptively regulating noise intensity for heterogeneous features or maintaining parameter precision under complex multi-modal distributions.

Furthermore, recent advancements in signal processing and affective computing have demonstrated the critical role of attention mechanisms and deep feature fusion in capturing complex, non-linear dependencies. For instance, MemoCMT introduced a cross-modal Transformer architecture that effectively fuses heterogeneous feature sets through attention-based weighting, while MSER [

37] demonstrated the superiority of cross-attention mechanisms in deep fusion paradigms. Similarly, AAD-Net [

38] utilized attention-based deep echo state networks to achieve robust signal processing with high computational efficiency. These methodologies highlight the potential of attention-driven feature evolution in modeling complex data distributions: a principle we adapt herein for unsupervised anomaly detection in tabular data. The principal contributions are as follows:

- (1)

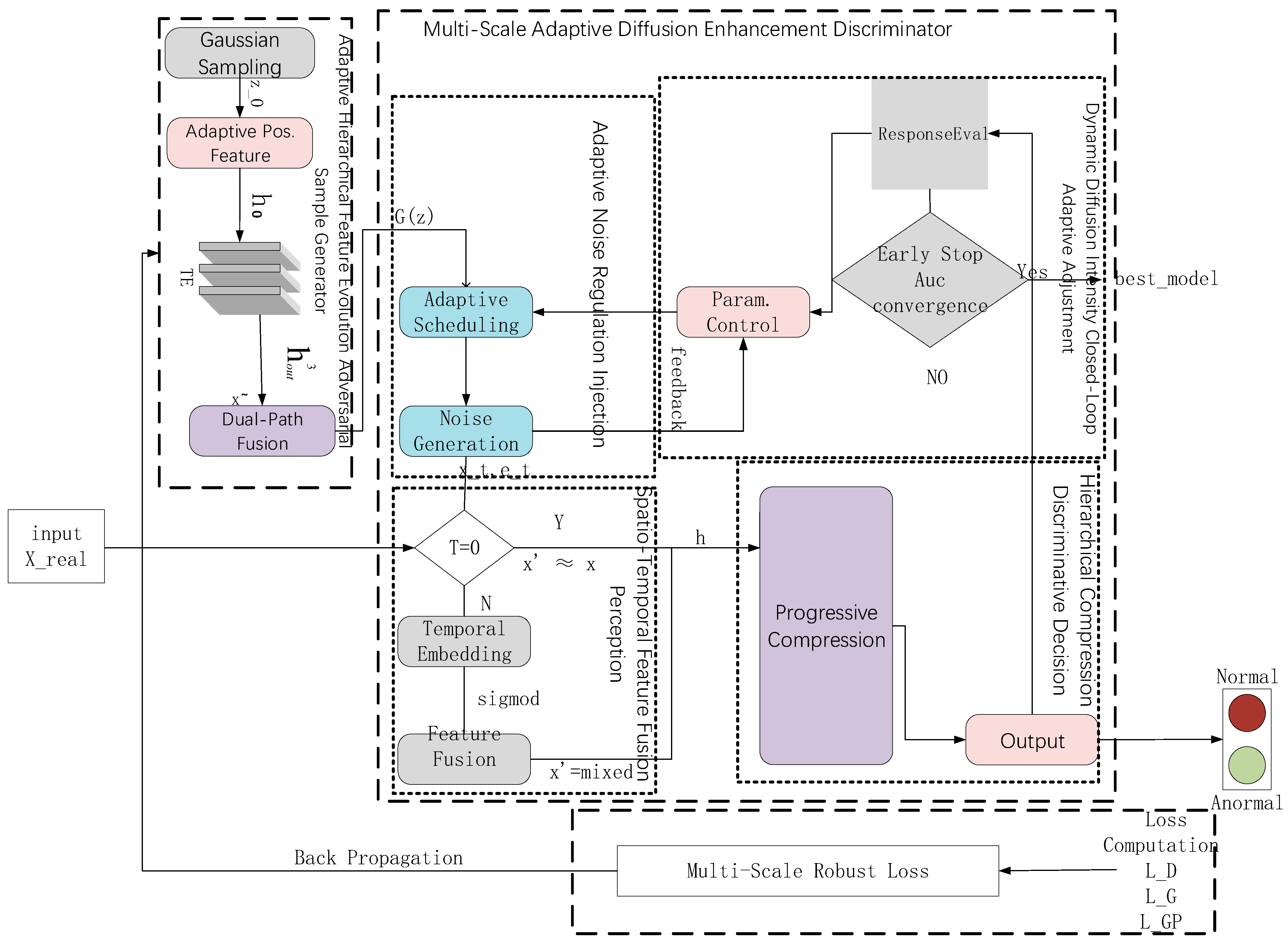

Comprehensive framework design: ADAEN integrates an adaptive hierarchical feature evolution generator, a multi-scale diffusion-augmented discriminator, and a robust adversarial gradient loss function. This architecture achieves precise modeling of complex feature patterns through a diffusion–adversarial co-evolution mechanism and attains state-of-the-art detection performance across 14 UCI benchmark datasets, effectively mitigating the limitations of the existing unsupervised approaches, including excessive reliance on hyperparameter tuning, noise sensitivity, and poor generalization.

- (2)

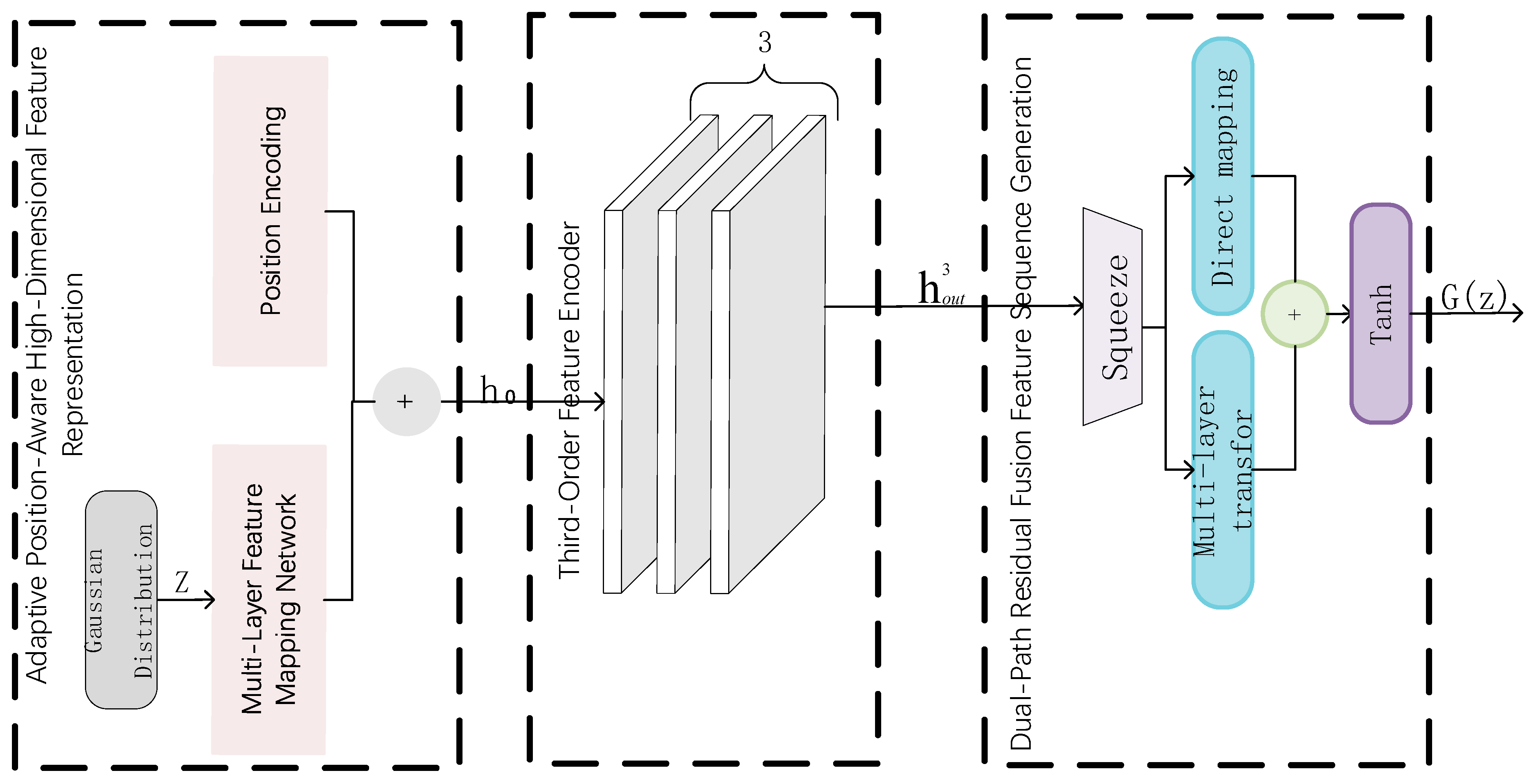

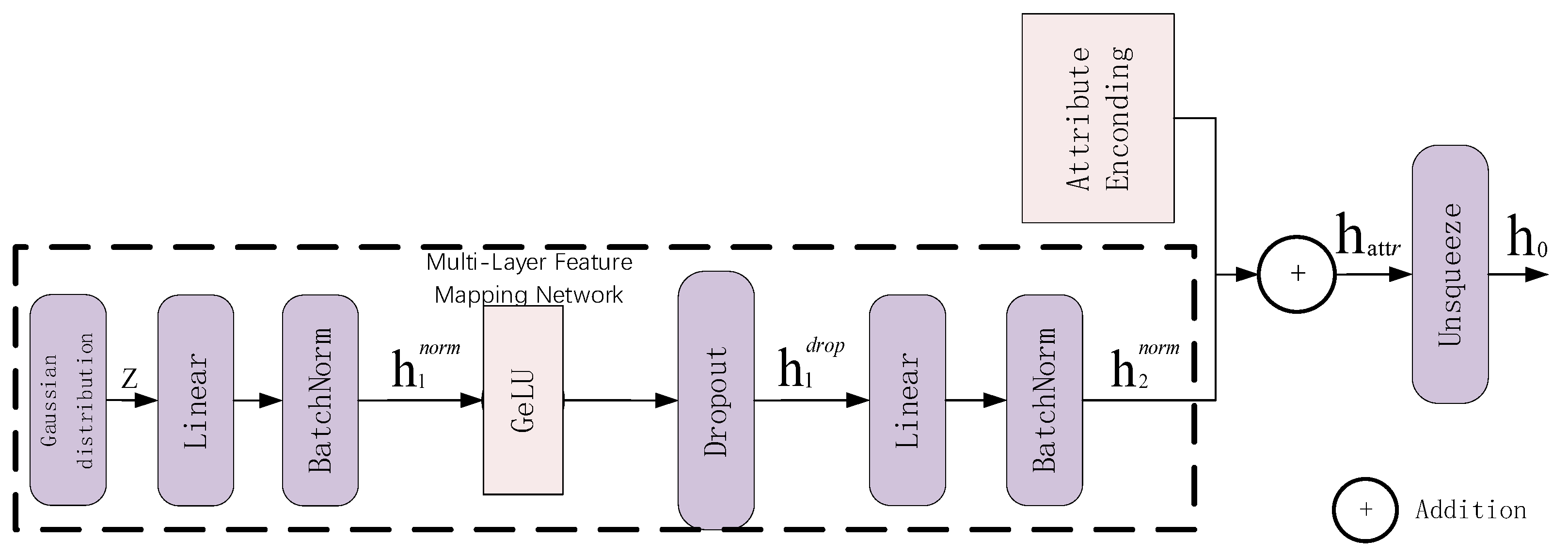

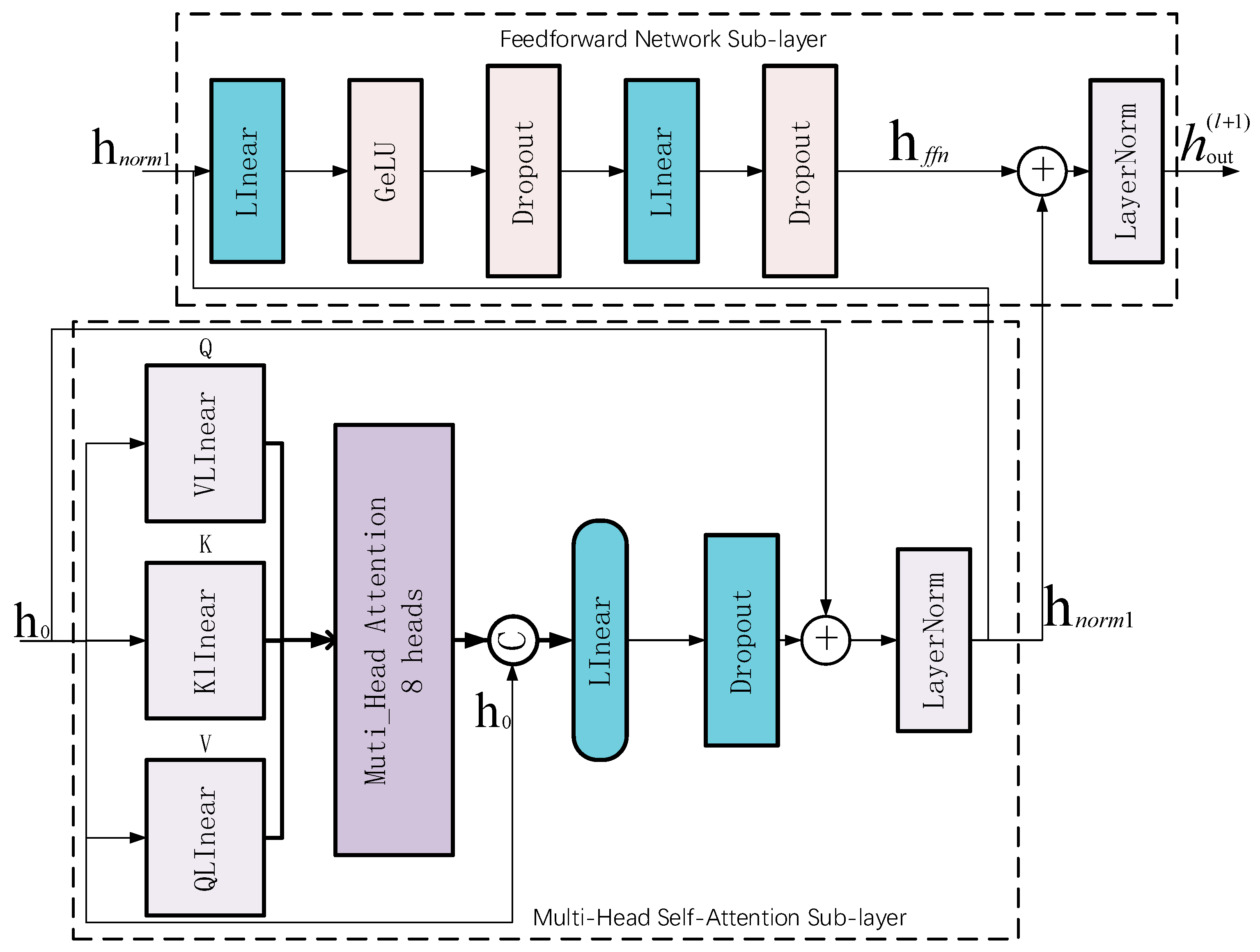

Adaptive hierarchical feature evolution generator: We introduce an adaptive attribute-aware mechanism employing learnable encodings to capture structured inductive bias, overcoming the spatial information deficiency that is inherent in single latent vector representations. A third-order Transformer encoder captures multi-granularity feature dependencies via multi-head attention, while a dual-path residual fusion mechanism ensures information integrity during deep feature extraction. These components collectively address the sharp decline in detection accuracy exhibited by conventional generators on non-uniformly distributed data, thereby enhancing model generalization.

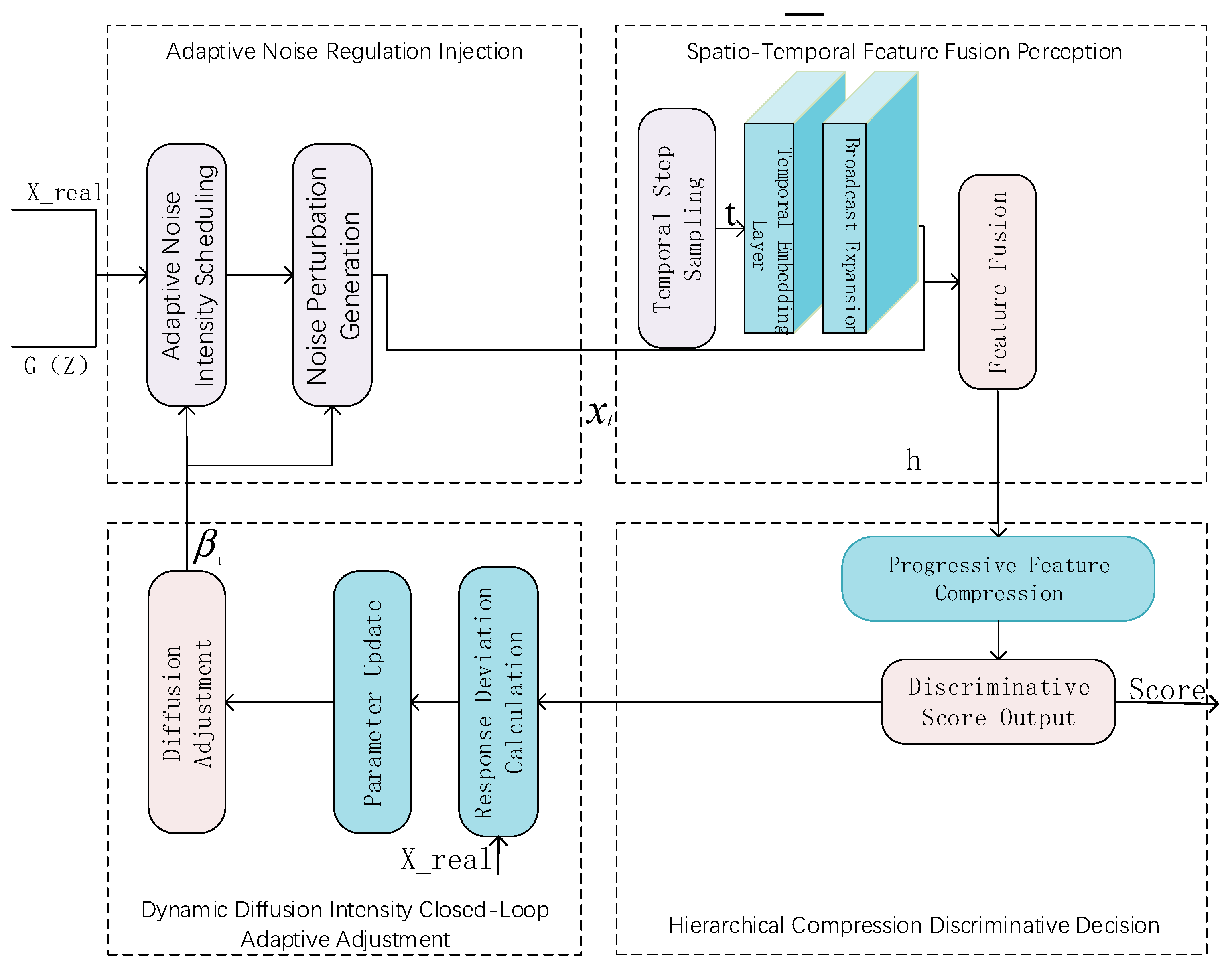

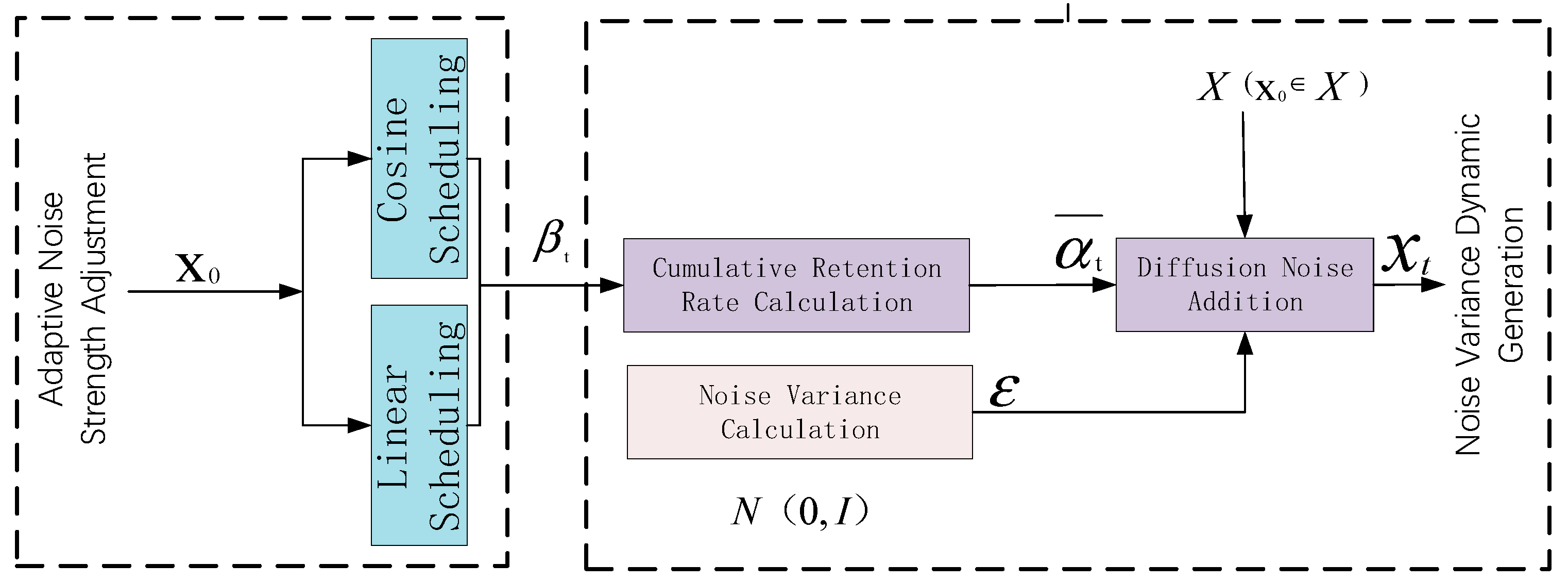

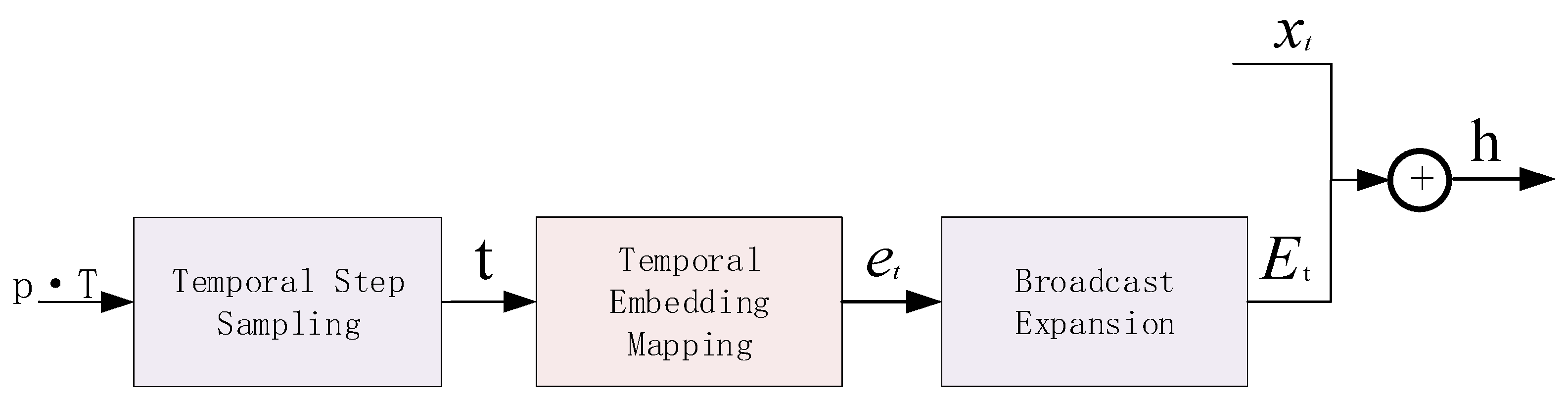

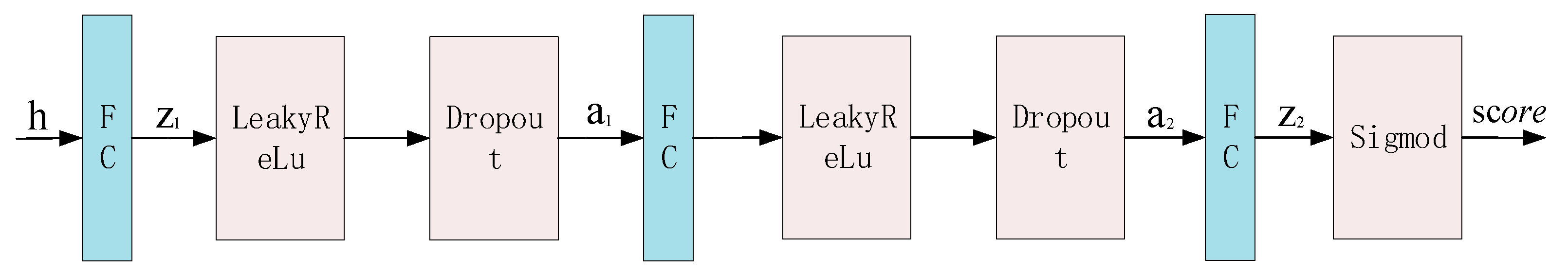

- (3)

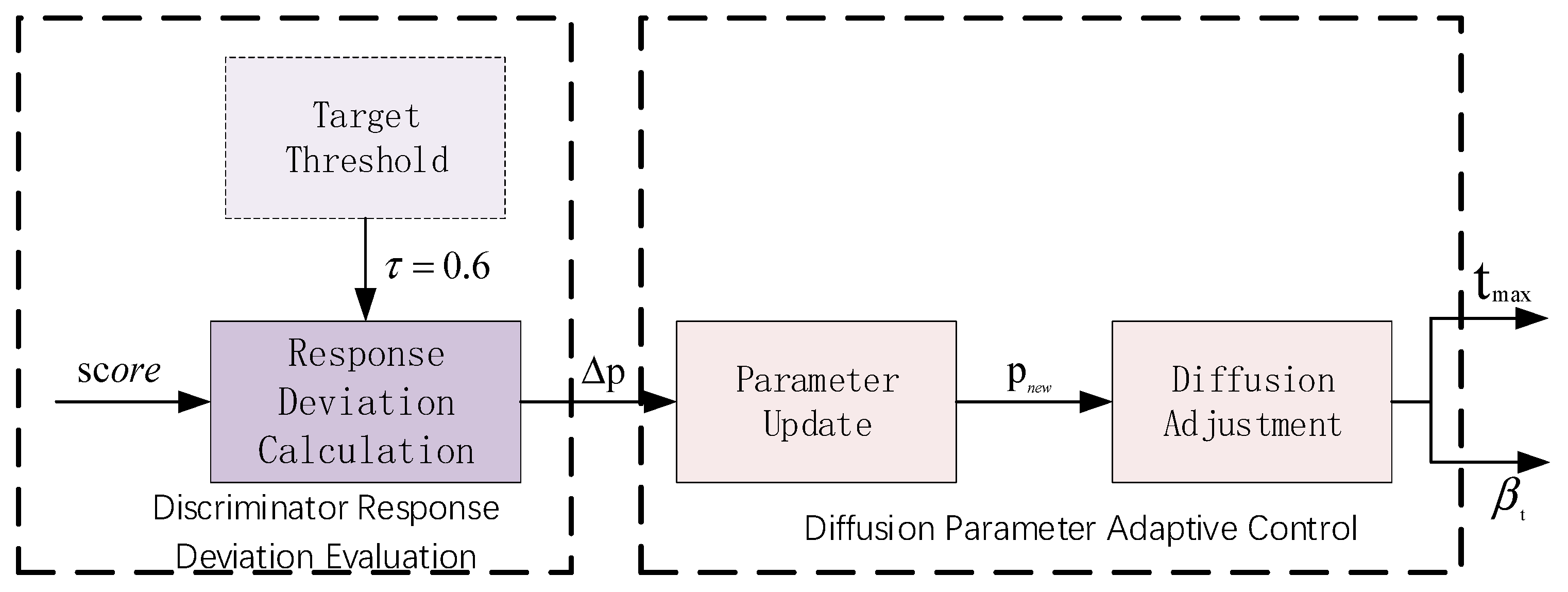

Multi-scale adaptive diffusion-augmented discriminator: We design a discriminator that preserves scale-specific features across distinct diffusion stages through cosine-scheduled adaptive noise injection, transcending the limitations of single-scale feature learning. A diffusion-conditional feature fusion perception mechanism deeply couples diffusion step information with data features, endowing the discriminator with diffusion-stage awareness. A closed-loop feedback regulator dynamically optimizes diffusion parameters based on discriminator performance, enabling co-evolution between the diffusion process and discriminator training, thereby significantly improving detection accuracy.

- (4)

Multi-scale robust adversarial gradient loss function: We formulate a loss function that optimizes the distributional distance between real and generated data across multiple noise, scales using diffusion-step-conditional Wasserstein loss. Gradient penalty enforces Lipschitz continuity of the discriminator via soft constraints, effectively preventing gradient explosion or vanishing. An adaptive weighting mechanism dynamically adjusts the contributions of individual loss components according to training dynamics. Together, these components resolve the training instability and mode collapse that is commonly observed in GAN-based methods on high-dimensional tabular data, thereby enhancing algorithmic robustness.

This work directly addresses the challenges of unsupervised anomaly detection in machine learning applications, contributing to the advancement of monitoring systems across multiple domains, including healthcare monitoring, network security, and industrial quality control.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the ADAEN framework and its three core components: the adaptive hierarchical feature evolution generator, the multi-scale adaptive diffusion enhancement discriminator, and the multi-scale robust adversarial gradient loss function.

Section 3 describes the experimental setup, including the 14 UCI benchmark datasets and implementation details, and presents comprehensive performance comparisons through decision boundary visualization, quantitative metrics, and ablation studies.

Section 4 summarizes the paper and discusses future research directions.

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1. Datasets

The proposed anomaly detection method in tabular data is trained and validated on datasets containing both normal and abnormal samples. This paper employs 14 widely used static anomaly detection benchmark datasets for experimental validation, sourced from the UCI machine learning database.

The experimental datasets are Pima, Shuttle, Stamps, PageBlocks, PenDigits, Annthyroid, Waveform, WDBC, Ionosphere, SpamBase, APS, Arrhythmia, HAR, and p53Mutant. These 14 datasets cover diverse application domains, including medical diagnosis, image recognition, text classification, and network security. The feature dimensions range from 8 to 5408, with sample sizes varying from 150 to 20,000. These samples are treated as independent and identically distributed observations without temporal dependencies.

This paper categorizes the 14 datasets by dimensions into three groups for comparative performance evaluation. Low-dimensional datasets (dimension < 20) include Pima (eight dimensions), Shuttle (nine dimensions), and Stamps (nine dimensions). Medium-dimensional datasets (dimension 20–100) include Waveform (21 dimensions), WDBC (30 dimensions), Ionosphere (32 dimensions), and SpamBase (57 dimensions). High-dimensional datasets (dimension > 100) include APS (170 dimensions), Arrhythmia (279 dimensions), HAR (561 dimensions), and p53Mutant (5408 dimensions).

3.2. Experimental Implementation

Experimental Environment: The experimental hardware environment employs NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 Laptop GPU graphics card (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with 8 GB storage space. The CPU model is an Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-10300H processor (Intel, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with main frequency 2.50 GHz. The system memory is 16 GB. The operating system adopts Windows 10 and Python (version 3.5). The deep learning framework uses PyTorch(version 2.0.0) and employs CUDA and GPU optimization acceleration.

Training parameter configuration: This paper conducts comparative experiments on 14 widely used anomaly detection benchmark datasets, using the proposed Transformer-based anomaly detection model for training. Models are dynamically adjusted according to the dataset scales, with the batch size set to 32 or 64. Training adopts the Adam gradient descent learning rate strategy. The initial learning rates for the generator and discriminator are set to 0.0001. Model training lasts 300–500 epochs, followed by feature dependency discriminator anomaly detection evaluation. The diffusion model adopts a fixed scheduling strategy with values linearly increasing from 0.0001 to 0.02. Diffusion step ranges from 10 to 100. The Transformer generator’s attention head count is set to eight, the encoder layer count is three, and the feedforward network dimension is 512 for effective extraction of feature representations. All models employ the Adam optimizer with parameter settings (\beta_1 = 0.5), (\beta_2 = 0.999). Training processes adopt network regularization strategies with a cutoff threshold set to 1.0. Discriminator dropout rates are set to 0.3 to avoid overfitting. Models employ early stopping: when AUC metrics show no improvement for 50 consecutive epochs exceeding 0.001, training automatically terminates.

Noise schedule configuration:

Table 2 details the specific noise strategies for each experiment. We employ the linear schedule (Equation (13)) for low-dimensional uniform datasets and the cosine schedule for complex medium-to-high dimensional data to preserve semantic features. Adaptive feedback (Equations (23)–(26)) is enabled for all main comparisons (

Table 2) to dynamically optimize the global intensity scalar,

.

Table 2 is the configuration of noise schedules and adaptive feedback for experiments.

3.3. Metrics

Evaluation metrics: For anomaly detection tasks, the ROC curve area (AUC, area under the ROC curve), accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-Score are quantitatively employed to evaluate the proposed method’s performance.

AUC calculates the true positive rate,

, and the false positive rate,

, at different threshold values, as shown in Equation (37). This metric is insensitive to class imbalance and is particularly suitable for anomaly detection tasks:

AUC metric values range from [0, 1], with higher values indicating better model performance.

Accuracy calculates the proportion of correct predictions made by the model, computing the ratio of correctly predicted anomalous samples,

, and normal samples,

, to total samples, as shown in Equation (38):

where

represents false positive samples, i.e., incorrectly identified anomalous normal samples.

represents false negative samples, i.e., incorrectly identified normal anomalous samples.

Precision calculates the proportion of true anomalous samples among samples predicted as being anomalous by the model, primarily reflecting the model’s accuracy capability, as shown in Equation (39):

Recall calculates the proportion of correctly identified

among all anomalous samples,

, as shown in Equation (40). This metric reflects the model’s completeness capability:

The F1-Score represents the harmonic mean of the precision and recall, as shown in Equation (41). This metric comprehensively considers both model accuracy and completeness. When both precision and recall are high, the F1-Score will be high:

3.4. Performance Comparison and Analysis

3.4.1. Decision Boundary Visualization Analysis

In anomaly detection tasks, the decision boundary is the boundary surface that distinguishes between normal and abnormal samples. It defines which regions in the feature space belong to normal patterns and which regions should be identified as anomalous. Unlike traditional classification tasks, anomaly detection primarily challenges learning an accurate decision boundary based on normal samples alone. When normal data distribution encompasses both rising and surrounding unknown regions, the proposed ADAEN method learns the complex distribution patterns of normal samples through adaptive hierarchical feature evolution and utilizes discriminator–diffusion cooperative models to optimize decision boundaries at multiple scales, achieving stability and robustness through adaptive response loss function boundary optimization. This enables accurate detection of various anomaly patterns. The effectiveness of this method will be validated through the detailed experimental results below.

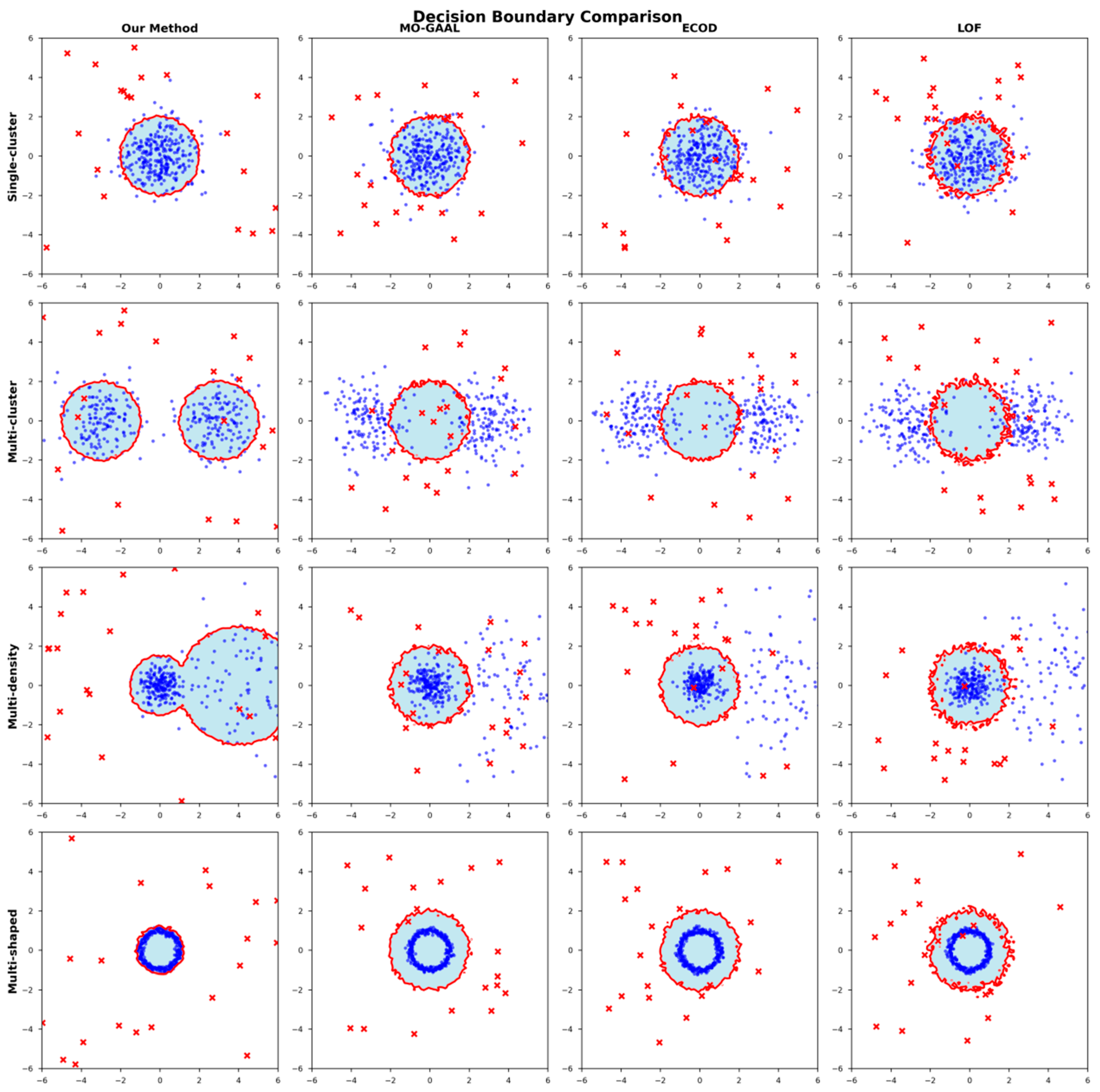

To further validate the superior performance of the proposed ADAEN method in handling different data distribution scenarios, particularly its adaptability in complex data structures and multi-modal distributions, we designed decision boundary visualization experiments based on synthetic datasets. We used scikit-learn library to generate four synthetic two-dimensional datasets, each containing 1000 samples. The four datasets separately simulate single-cluster, multi-cluster, multi-density, and complex geometric shape distribution scenarios.

Figure 10’s visualization results clearly demonstrate that this method can generate more accurate decision boundaries, particularly showing remarkable performance improvements when handling non-uniform and multi-cluster scenario distributions.

Figure 10 shows the decision boundary visualization results of this paper’s ADAEN method and three other representative MO-GAAL [

42], ECOD [

17], and LOF [

40] methods on four different datasets. Through comparative analysis, we can clearly observe the distinctive characteristics of different methods when handling various data distributions. On single-cluster datasets, this paper’s method can form more compact and accurate decision boundaries, effectively encompassing normal data points while maintaining appropriate boundary margins. In contrast, the LOF method’s boundaries are too loose, easily misclassifying anomalous points as normal, while ECOD and MO-GAAL show better performance, but their boundary smoothness and tightness are inferior to this paper’s method.

To elucidate the fundamental reasons behind ADAEN’s superior boundary quality, we analyze the inductive biases and architectural limitations of the competing frameworks from a theoretical perspective. LOF relies on local reachability distances in the raw feature space, making it susceptible to the “curse of dimensionality” and sampling noise, which manifests as jagged, irregular boundaries in

Figure 10. MO-GAAL, though adversarially trained, suffers from mode collapse—a common pathology in GAN-based methods where the generator fails to cover multi-modal distributions, which is evident in its inability to separate bimodal clusters. ECOD assumes feature independence, forcing it into axis-aligned rectangular boundaries that cannot capture non-convex topologies like the ring structure. Deep SVDD imposes a unimodal hypersphere assumption, which is inherently incapable of modeling hollow geometries. In contrast, ADAEN addresses these deficiencies through three synergistic mechanisms: (1) the AHFE generator maps data into a learned latent manifold, avoiding raw-space distance concentration; (2) the MSAD discriminator’s multi-scale diffusion enables simultaneous global separation (high-noise regime) and local refinement (low-noise regime); and (3) Transformer-based multi-head attention captures non-linear feature dependencies without positional constraints, enabling precise modeling of complex, non-convex data topologies.

In single-cluster distribution scenarios, the proposed ADAEN method generates ideal circular decision boundaries that tightly encompass normal samples while maintaining appropriate boundary margins. In contrast, MO-GAAL’s boundaries are too loose, with multiple anomalous points mistakenly being included in normal regions; ECOD generates irregular multi-boundary situations with obvious concavities at boundaries; and LOF shows naturally reasonable boundary shapes but has overly circular boundary regions, unable to fully distinguish normal sample distributions.

When facing bimodal distributions, this paper’s ADAEN method successfully identifies and encompasses two independent normal regions, with each having precise elliptical boundary packages. MO-GAAL completely fails to identify bimodal structures, generating single large-scale boundaries; ECOD, although partially identifying bimodal characteristics, has two boundaries existing in severe overlap; and the LOF method divides data space through degrees, generating multiple fragmented small boundaries.

In density difference scenarios, this paper’s ADAEN method demonstrates excellent adaptive capability, generating compact boundaries for dense regions while providing more relaxed boundary packages for low-density regions. MO-GAAL uses unified boundary strategies, resulting in poor detection effectiveness; ECOD shows considerable performance in high-density regions but cannot effectively adapt to low-density distributions; and LOF, due to dependence on local density ratios, generates erroneous judgments in density variation regions.

Ring-shaped distribution serves as the most challenging non-convex shape data, fully validating this paper’s method’s superiority. This paper’s method perfectly learns ring-shaped decision boundaries, accurately identifying central cavity regions as anomalous. MO-GAAL generates boundaries encompassing entire regions, treating central cavity regions as normal and completely ignoring ring-shaped structural characteristics; ECOD generates fragmented irregular boundaries, unable to accurately carve complete ring-shaped structures; and LOF shows considerable recognition of ring-shaped outlines, but decision boundaries exhibit obvious local fluctuations and irregularities, with insufficient boundary smoothness and accuracy.

Therefore, ADAEN maintains stable and superior detection performance across different data distribution patterns and datasets. This superior performance capability stems from adaptive hierarchical feature evolution and multi-scale robust adversarial gradient loss function cooperation. Generation achieves effective mapping to high-dimensional feature representation through an adaptive position awareness mechanism, with third-order feature encoding multi-head self-attention mechanisms, enabling the parallel processing of different feature sub-spaces. Dual-path residual fusion ensures effective combination of deep features and original information. Simultaneously, the multi-scale robust adversarial gradient loss function enables large-scale data through diffusion-conditional Wasserstein loss optimization at multi-noise scales. The gradient penalty mechanism ensures that the discriminator satisfies the Lipschitz continuity conditions, effectively preventing gradient explosion problems during training. Generator optimization loss provides stable gradient signals through a negative Wasserstein distance. The adaptive weighting mechanism dynamically balances gradient loss components according to training status, further enhancing model convergence stability. Generator feature optimization capability complements the discriminator stability optimization mechanisms, enabling generators to gradually learn and generate complex data patterns. This framework design enables ADAEN to demonstrate outstanding adaptability and robustness across different-dimensional datasets.

Regarding computational overhead, ADAEN makes certain trade-offs for higher accuracy compared to other methods (see

Table 3). On high-dimensional datasets in Arrhythmia (>100 dims), ADAEN requires 4.5 h for training compared to Mamba-AD’s 2.8 h (+60.7%), and 25.8 ms inference latency versus 18.3 ms (+40.9%). This additional cost stems mainly from the Transformer block (multi-head projections and FFN/residual refinement) used to model complex cross-feature interactions in permutation-invariant tabular data. However, this investment yields substantial returns: a 2.4% AUC improvement (0.842 → 0.862) and a 15.7% reduction in false positive rate. Notably, ADAEN achieves 53.6% faster inference than diffusion-based DiffusionAD (55.7 ms) by leveraging direct discriminator scoring instead of iterative denoising.

Specifically, the normalized total time is computed by summing the per-dataset training time and the inference time required for 10,000 samples, with inference latency being converted from milliseconds to hours for fair comparison across methods.

3.4.2. Performance Metric Comparison

To objectively demonstrate that our proposed ADAEN architecture’s anomaly detection performance surpasses other methods, we conducted comprehensive comparative experiments on 14 UCI benchmark datasets. The comparison methods include traditional statistical-based LOF, deep-learning-based Deep SVDD [

41], generative adversarial network-based MO-GAAL, diffusion-model-based DiffusionAD [

43], and state-space-model-based Mamba-AD [

44]. Experimental results are shown in

Table 4.

ADAEN effectively bridges the performance gap between traditional methods and deep learning approaches. On low-, medium-, and high-dimensional datasets, Deep SVDD achieved AUC values of 0.818, 0.803, and 0.788, respectively. Our method improved the AUC to 0.928, 0.936, and 0.862, respectively, representing improvements of 13.4%, 16.6%, and 9.4%.

On low-dimensional datasets (<20 dimensions), ADAEN achieved an average AUC and F1-Score of 0.928. The method’s MAE was 0.087 and the MSE was 0.015. Compared to Mamba-ADs 0.095 and 0.017, ADAEN’s MAE decreased by 8.42% and MSE decreased by 11.76%. ADAEN’s AUC and F1 improved by 2.0% compared to Mamba-AD’s 0.910.

On medium-dimensional datasets (20–100 dimensions), ADAEN achieved an AUC of 0.936 and an F1-Score of 0.935. The method’s MAE was 0.092 and the MSE was 0.017. Compared to Mamba-AD’s 0.103 and 0.020, ADAEN’s MAE decreased by 10.68% and the MSE decreased by 15.00%. ADAEN’s AUC improved by 2.6% compared to Mamba-ADs 0.912, and the F1 improved by 1.5% compared to 0.921.

On high-dimensional datasets (>100 dimensions), ADAEN achieved an AUC of 0.862 and an F1-Score of 0.862. The method’s MAE was 0.128 and the MSE was 0.031. Compared to Mamba-AD’s 0.142 and 0.036, ADAEN’s MAE decreased by 9.86% and the MSE decreased by 13.89%. ADAEN’s AUC and F1 both improved by 2.4% compared to Mamba-AD’s 0.842.

ADAEN’s high detection accuracy primarily stems from the innovative design of the multi-scale adaptive diffusion enhancement discriminator. This discriminator dynamically adjusts noise intensity across different diffusion stages through cosine-scheduled adaptive noise injection strategies. This enables the discriminator to preserve critical feature information at multiple scales. Adaptive noise regulation injection deeply couples diffusion step information with data features, endowing the discriminator with diffusion-stage awareness. The dynamic diffusion intensity closed-loop adaptive adjustment dynamically optimizes diffusion parameters based on discriminator performance. This mechanism achieves collaborative evolution between diffusion processes and discriminative training. Experiments show that introducing this discriminator alone can improve AUC by 5.0%, demonstrating the core role of multi-scale diffusion mechanisms in accuracy enhancement.

ADAEN’s stable performance across different dimensional datasets reflects its strong generalization capability. This generalization capability stems from the collaborative design of the adaptive hierarchical feature evolution generator and multi-scale discriminator. The generator captures the multi-granularity feature through third-order feature encoders and dual-path residual fusion mechanisms. The discriminator’s multi-scale diffusion strategy enables the model to flexibly adapt to data distribution characteristics across different dimensions. On low-dimensional (<20 dimensions), medium-dimensional (20–100 dimensions), and high-dimensional (>100 dimensions) datasets, ADAEN achieved AUC values of 0.928, 0.936, and 0.862, respectively. This stable performance across dimensions demonstrates the generalization capability of the architectural design. Although DiffusionAD employs diffusion models, it lacks adaptive feature evolution capability. Mamba-AD is inferior to ADAEN’s multi-head self-attention mechanism in complex pattern recognition. However, it is worth noting that the relative performance improvement on high-dimensional data will decrease as the data dimensionality and imbalance increase.

ADAEN’s robustness in complex data scenarios is primarily attributed to adaptive adjustment mechanisms and robust loss functions. The multi-scale diffusion strategy in the discriminator addresses the limitations of fixed noise methods that cannot adapt to complex data distributions. This enables ADAEN to maintain high-precision detection when handling non-uniform distributions and multi-modal data. Hierarchical compression discriminative decision-making further enhances the discriminator’s feature extraction efficiency and interference-resistance capability. The multi-scale robust adversarial gradient loss function ensures training stability through Wasserstein distance and gradient penalty mechanisms. This loss function effectively prevents gradient explosion and mode collapse problems. Ablation experiments show that on the non-uniformly distributed multi-density dataset, ADAEN’s MAE decreased by 10.68%, demonstrating the method’s robustness advantages.

3.4.3. Ablation Experiments

The effectiveness of the overall framework has been validated in all previous experiments. In the ablation experiment section, we focus on analyzing the independent contributions of each module and comparing the effects of different module combinations, loss function configurations, and diffusion strategies.

- (1)

Architectural components and key sub-module ablation experiments

To verify the independent roles and synergistic effects of the adaptive hierarchical feature evolution generator, multi-scale adaptive diffusion enhancement discriminator, and multi-scale robust adversarial gradient loss function, experimental results on the Arrhythmia dataset are shown in

Table 5.

Base represents the baseline model using only traditional GAN architecture, AHFE represents the adaptive hierarchical feature evolution adversarial sample generator, MSAD represents the multi-scale adaptive diffusion enhancement discriminator, and MSAG represents the multi-scale robust adversarial gradient loss function.

From the architectural module ablation experiments, it can be observed that all three core modules make significant contributions to model performance. Compared to the Base model, after independently introducing AHFE (adaptive hierarchical feature evolution adversarial sample generator), the AUC improved from 0.798 to 0.826 (3.5% improvement), and Abs Rel decreased from 0.158 to 0.142 (10.1% reduction), indicating that the adaptive hierarchical feature evolution adversarial sample generator effectively enhanced the model’s ability to capture complex high-order correlations among attributes. After independently introducing the MSAD (multi-scale adaptive diffusion enhancement discriminator), the AUC improved to 0.838 (5.0% improvement), demonstrating that the diffusion mechanism enhanced the model’s multi-scale feature learning capability. Although independently introducing the MSAG (multi-scale robust adversarial gradient loss function) showed relatively smaller improvement (1.8% AUC increase), it contributed significantly to the training stability, reducing training time by approximately 15%.

When combining two modules, performance further improved. The AHFE + MSAD combination achieved an AUC of 0.871, improving by 5.4% and 3.9% compared to using AHFE or MSAD alone, respectively, indicating the complementary effects between the adaptive hierarchical feature evolution adversarial sample generator and multi-scale adaptive diffusion enhancement discriminator. The complete model (AHFE + MSAD + MSAG) demonstrated optimal performance, with an AUC of 0.892, representing an 11.8% improvement over the Base model, and the F1-Score improved from 0.735 to 0.827 (12.5% improvement). Although the parameter count increased from 28.6 M to 48.1 M (68.2% increase), this resulted in significant performance gains, proving the efficiency of the architectural design.

To further verify the necessity of internal technical designs within each architectural component, we systematically removed key sub-modules from the complete model and analyzed their impact on the overall performance. These sub-modules include the following: diffusion module and diffusion step encoding (internal components of MSAD), attribute encoding, multi-head attention, and residual connections (internal components of AHFE). Through this fine-grained ablation analysis, we can gain a deep understanding of each technical detail’s contribution to the final performance. Experimental results are shown in

Table 6.

w/o indicates the removal of the corresponding component. Diffusion module, diffusion step encoding, adaptive feature attribute encoding, multi-head attention, and residual connections, respectively, correspond to key technical components in the innovations.

Sub-module ablation experiments validated the importance of each component across four datasets with different characteristics: Pima, SpamBase, PenDigits, and Arrhythmia. After removing the diffusion module, all datasets showed significant performance degradation, with the high-dimensional Arrhythmia dataset’s AUC decreasing from 0.892 to 0.835 (6.4% decline), and the low-dimensional Pima dataset decreasing from 0.851 to 0.782 (8.1% decline), demonstrating the universal effectiveness of the diffusion component across different dimensional data.

Removal of the diffusion step encoding component resulted in an average performance decrease of 4.5%, with particularly pronounced impact on the SpamBase text dataset (5.1% AUC reduction), illustrating the importance of diffusion stage information for the generative diffusion process. Although learnable attribute encoding contributed relatively less (average decline of 3.2%), it still provided a 2.5% performance improvement on the PenDigits image dataset, indicating the auxiliary role of the attribute identity information for distinguishing heterogeneous features. Removal of multi-head attention and residual connection components resulted in average performance decreases of 2.3% and 1.5%, respectively. While the impact was smaller, these components are indispensable for the model’s expressive capability and training stability.

- (2)

Loss function ablation experiments

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed multi-scale robust adversarial gradient loss function in improving anomaly detection performance, we conducted ablation studies on Wasserstein adversarial loss,

, gradient penalty loss,

, and generator optimization loss,

, based on the Pima and SpamBase datasets, as shown in

Table 7.

represents the Wasserstein adversarial loss, represents the gradient penalty loss, represents the generator optimization loss, and represents the adaptive feedback adjustment mechanism.

Table 7 provides a detailed demonstration of the roles of the three individual components,

, in the adaptive objective loss function. On the Pima dataset, when no specialized loss function was used, the AUC was only 0.612. After introducing the Wasserstein adversarial loss,

, it improved to 0.745 (21.7% improvement), indicating that the adversarial loss provided the model with a fundamental discriminative learning capability. After adding the generator optimization loss,

, the AUC further improved to 0.792 (6.3% improvement), showing that negative Wasserstein distance optimization helps to improve generation quality and stabilize training gradients.

The introduction of the gradient penalty loss, , significantly improved training stability, with the combination showing a 7.8% improvement compared to alone. The combination of all three loss functions () achieved an AUC of 0.828, approaching the performance of the complete model.

Similar trends were observed on the SpamBase dataset, where the complete loss function showed a 32.5% AUC improvement compared to the unconstrained case (from 0.698 to 0.925), demonstrating the universality of the loss function design across different data types.

- (3)

Diffusion strategy ablation experiments

To demonstrate the superiority of the cosine scheduling diffusion strategy, we conducted experiments on the PenDigits dataset to examine the impact of different scheduling strategies on the model performance. The noise scheduling strategy during the diffusion process directly affects the training effectiveness and anomaly detection performance. The experimental results are shown in

Table 8.

The diffusion strategy experiments demonstrate that the cosine scheduling strategy adopted in this paper achieved optimal performance (AUC = 0.987), representing a 1.96% improvement over linear scheduling. Cosine scheduling increases noise slowly in low-noise regimes, preserving more original features, while rapidly increasing noise in later stages to generate diverse samples. The experimental training time of 3.6 h falls within a reasonable range and achieved the fastest convergence (210 epochs). This diffusion strategy realizes the optimal balance between performance and efficiency.

To validate the necessity of the “Adaptive” mechanism, we compared the proposed method against three fixed strategies: no diffusion, fixed intensity (

p = 0.5), and fixed intensity (

p = 1.0). As shown in

Table 9, the no diffusion baseline yields the lowest performance (AUC 0.835), confirming the fundamental value of the diffusion module. The fixed

p = 1.0 strategy employs maximum noise intensity throughout training, which disrupts the feature’s semantic integrity, resulting in suboptimal performance (AUC 0.848). While the fixed

p = 0.5 strategy achieves respectable results (AUC 0.872), it fails to adapt to the changing difficulty of the discriminator during training. In contrast, our adaptive (closed-loop) strategy dynamically adjusts

p based on the discriminator’s dynamic training feedback. This not only achieves the highest detection accuracy (AUC 0.892) but also accelerates convergence, reaching equilibrium 50 epochs earlier (Epoch 160) compared to the fixed strategy (Epoch 210).