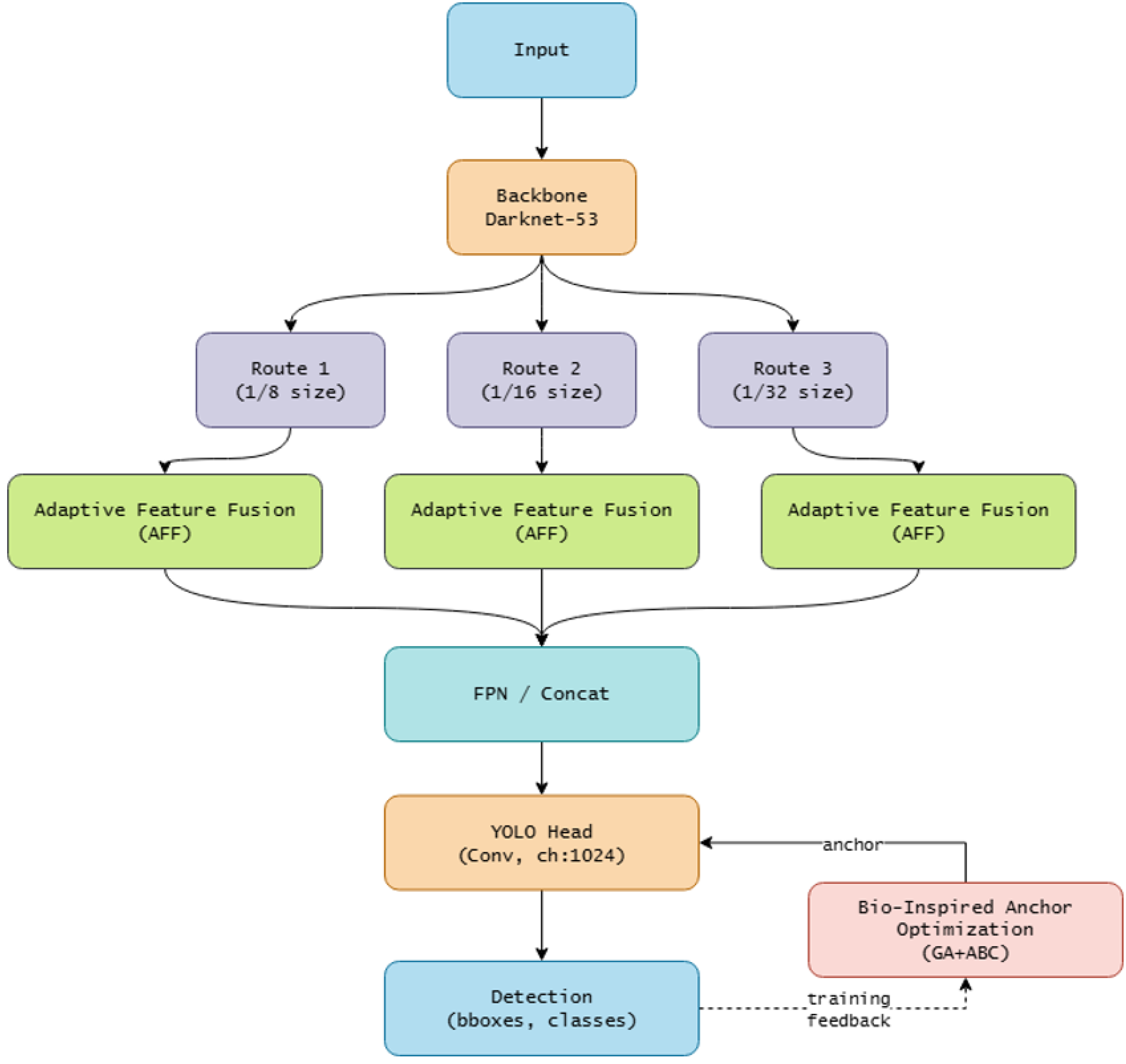

2.2.3. Proposed YOLOv3-Based Classification Method

In the YOLOv3 architecture, multi-scale feature maps are integrated using static concatenation, in which all levels are treated equally. This approach leads to the suppression of detailed features of low-level maps by signals from high-level structures, reducing the sensitivity of the model to minor defects that are critical in the maintenance of wind turbine structures.

To overcome this drawback, we propose the introduction of Adaptive Feature Fusion (AFF) [

40], which provides dynamic redistribution of control coefficient weights between levels during training. Let

be a set of features of level

l, then for each set, the global context descriptor

is calculated by averaging over spatial dimensions:

Next, the vector

is fed into a trainable weight normalization mechanism, which includes a fully connected layer and a softmax function that forms the coefficients

:

where

w is a model parameter optimized jointly with the network. Thus, the final fusion map is calculated as a weighted combination:

As a result, the coefficients

are formed individually for each image, ensuring the amplification of the contribution of low-level maps in the presence of minor defects, while preserving the context of high-level structures. Unlike known attention modules (SENet, CBAM, BiFPN) [

41,

42,

43], the proposed mechanism is focused on improving the accuracy of image processing with minor defects without losing semantic information, which is critical for wind farm maintenance tasks.

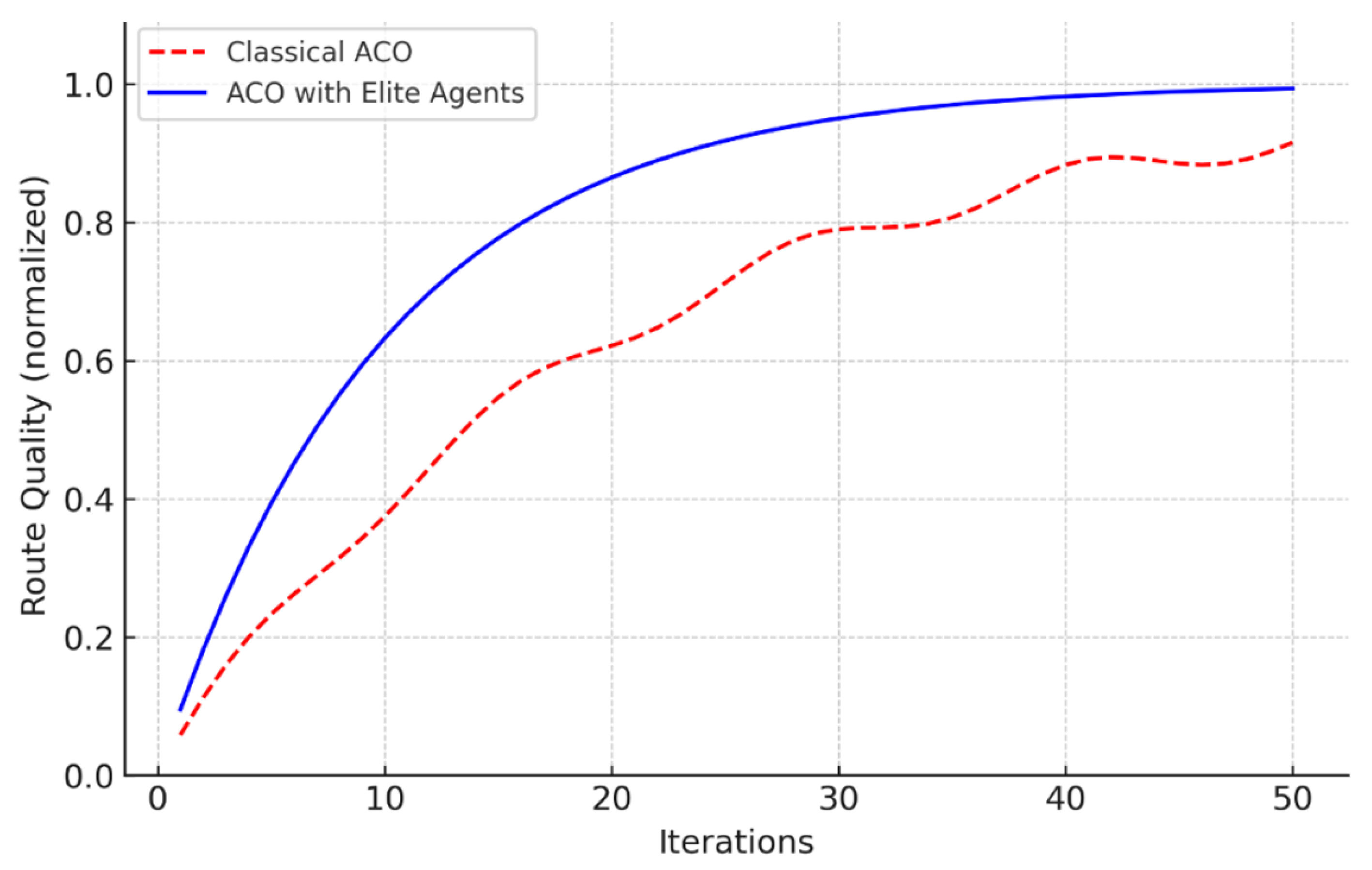

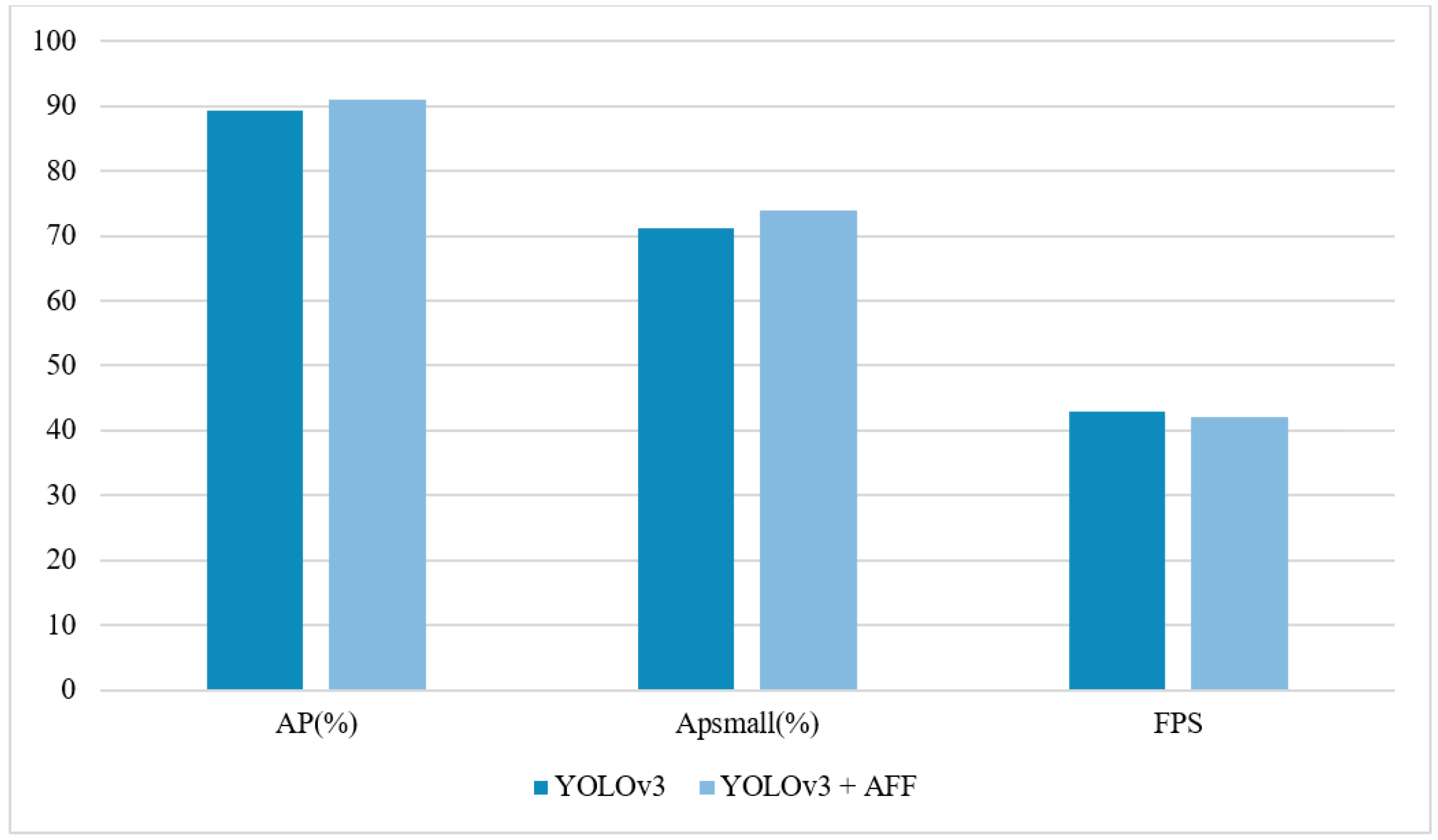

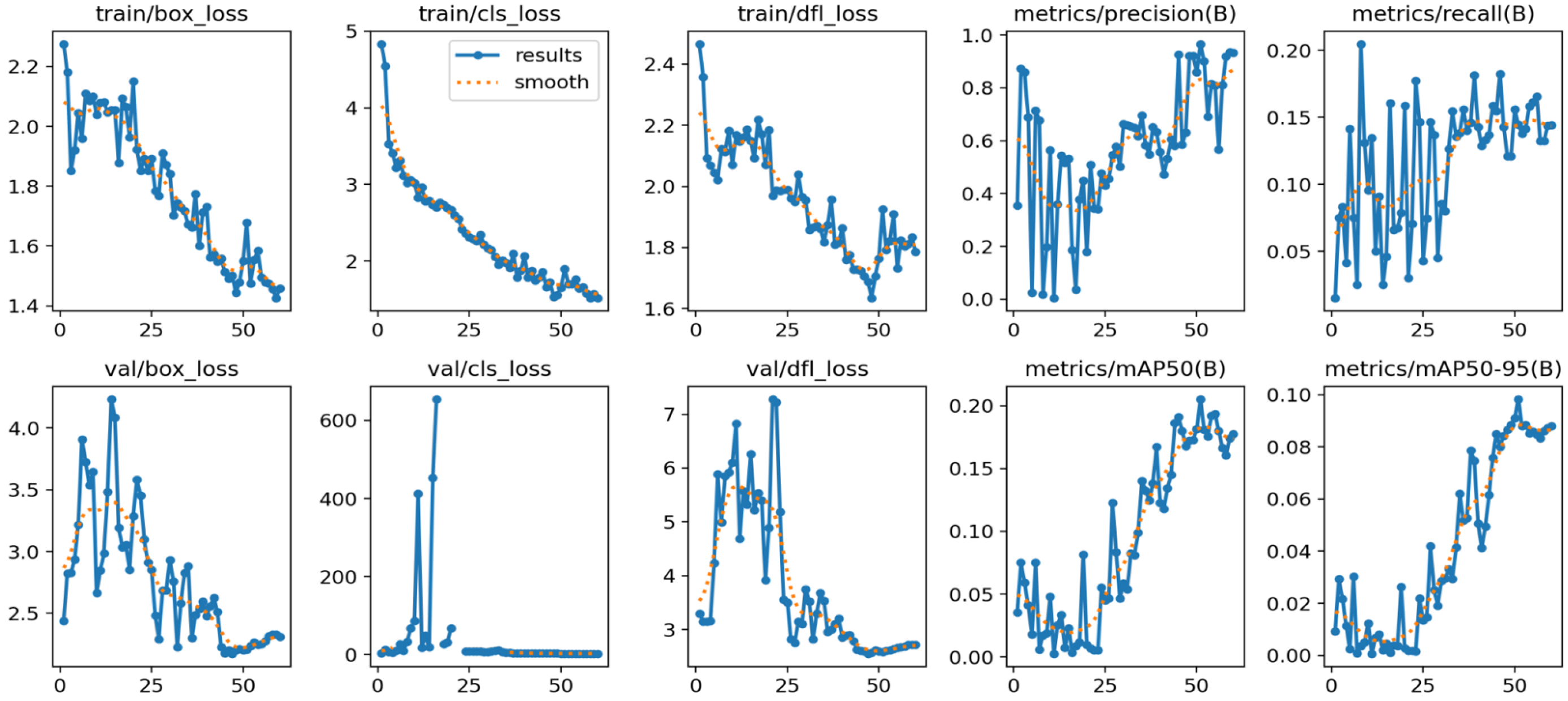

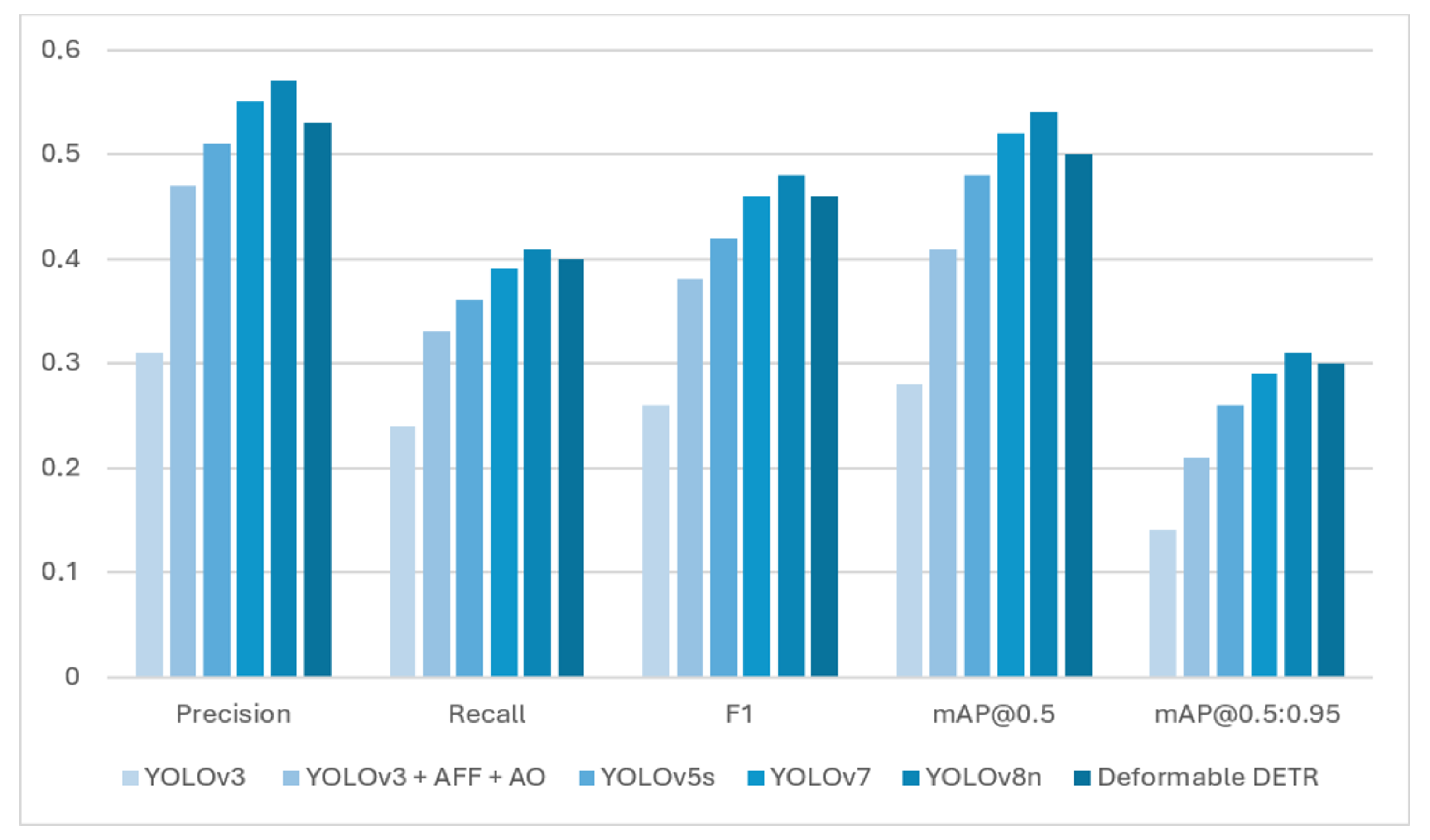

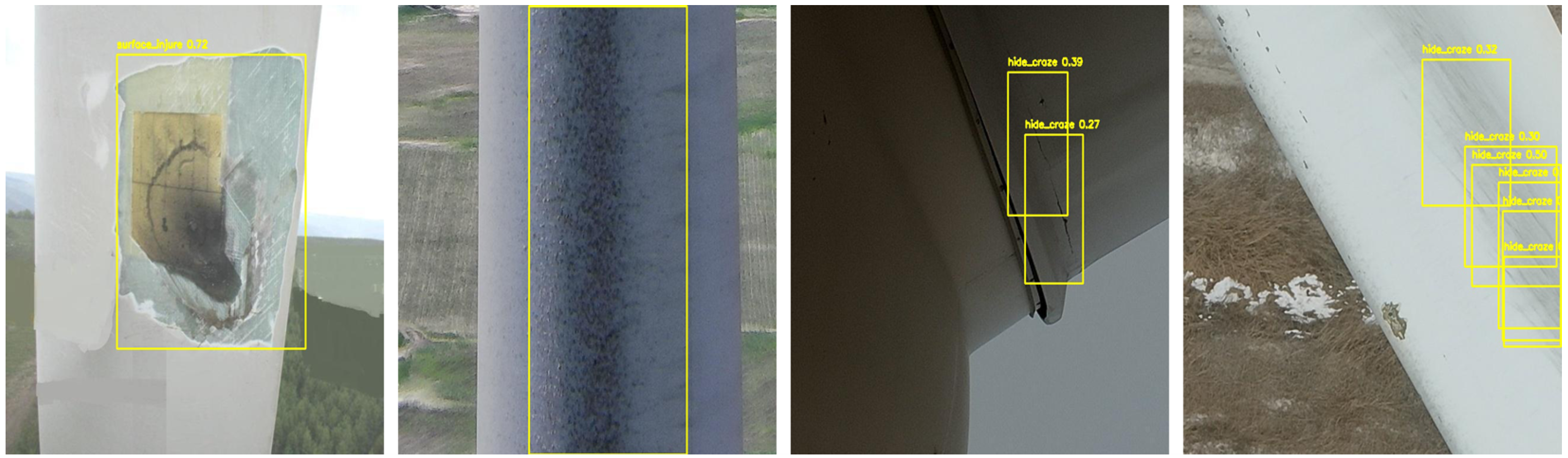

The effectiveness of the approach is confirmed by experimental results (

Table 1), where the average precision (AP) increased by 1.7%, and the precision for small objects (

) increased by 2.7% while maintaining the processing speed. The visualization of the presented results is shown in

Figure 8.

The results show that AFF integration improves the detection quality of small objects without significantly reducing performance. However, the use of an additional fully connected layer increases the number of model parameters and slightly reduces the processing speed (less than 2%). It should be noted that this compromise is justified by the increase in accuracy when solving wind farm maintenance tasks.

2.2.4. Bio-Inspired Anchor Box Optimization

Optimization of anchor frame parameters in object detection architectures is determined by the task of minimizing the discrepancy between anchor frames and actual bounding boxes in the training set. The k-means method used in YOLOv3 provides a basic approximation of parameters, characterized by low stability with high variability in the shapes and sizes of defects.

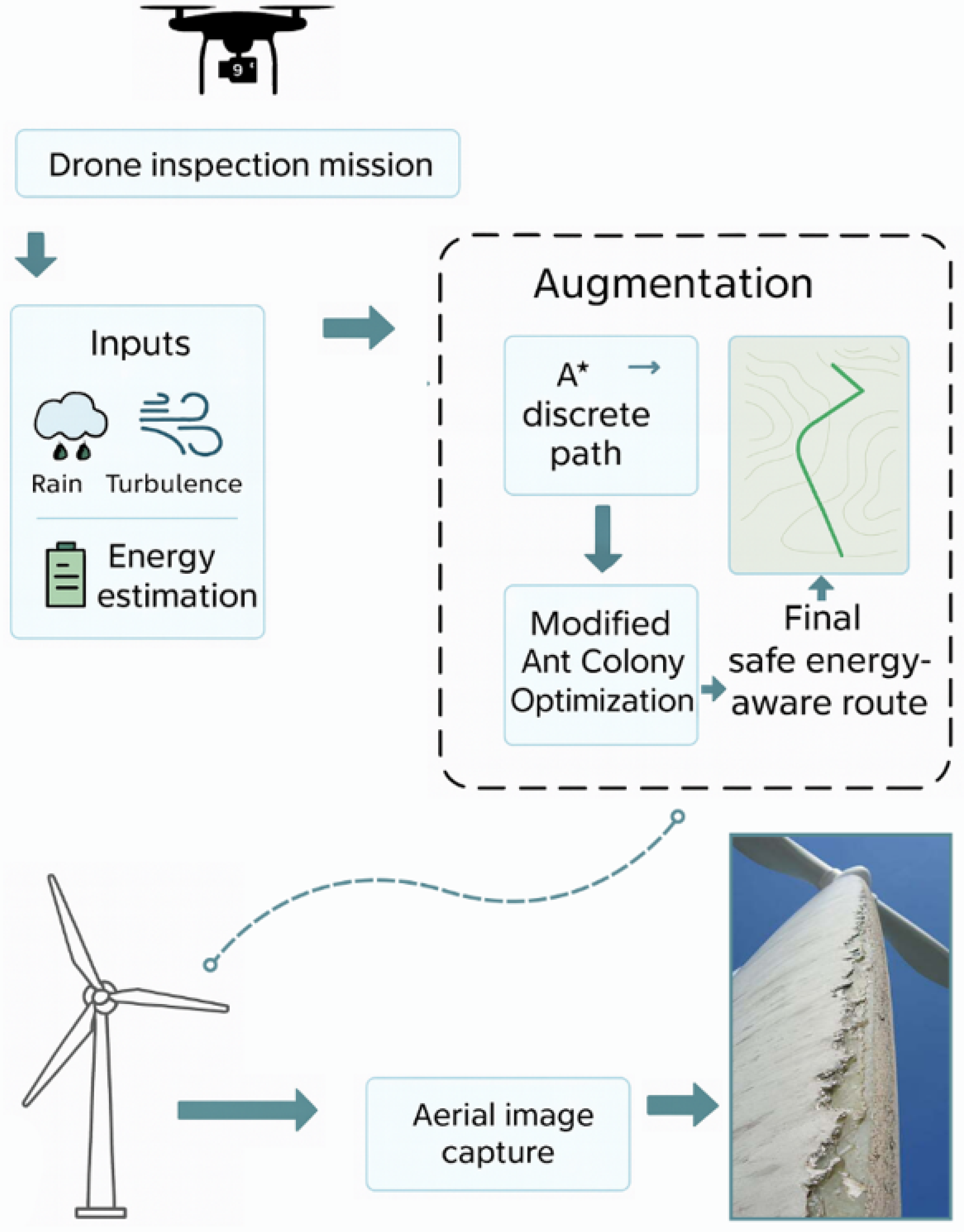

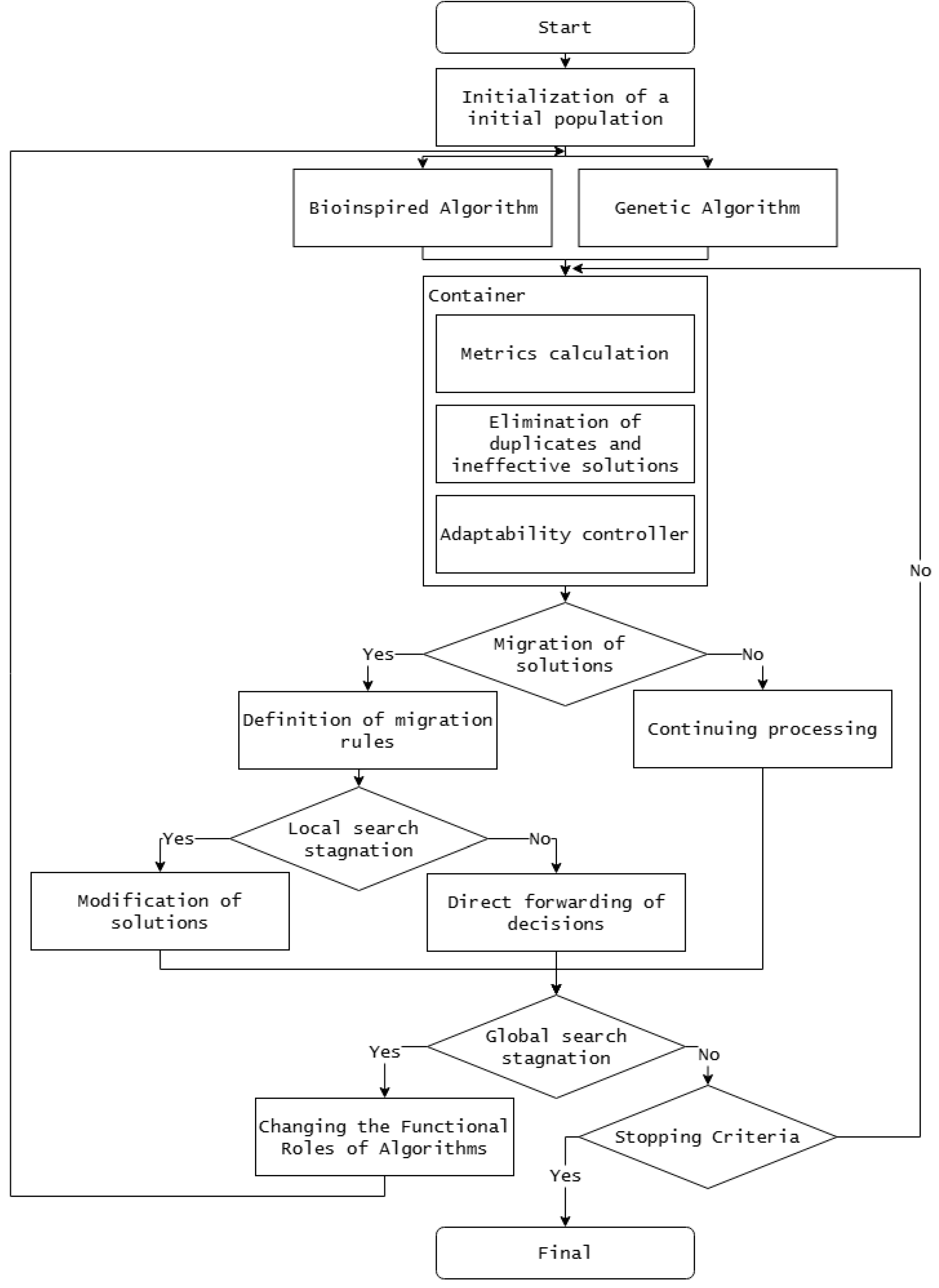

As part of this study, the authors have developed a bio-inspired optimization strategy based on the interaction of evolutionary and swarm search mechanisms operating within a hybrid-parallel architecture that ensures the coordinated execution of global search and local adaptation procedures with dynamic redistribution of computational resources. A structural diagram of the proposed architecture is shown in

Figure 9.

The conceptual novelty of the proposed optimization module lies in the integration of evolutionary refinement and swarm-based diversification within a multi-level clustering framework that dynamically adapts anchor frame parameters to the geometric heterogeneity of visual defects. In contrast to traditional techniques that rely on static anchor initialization or single-stage clustering, the hybrid strategy introduces an adaptive exchange of intermediate solutions between the genetic algorithm and the bio-inspired search subsystem. This ensures a balanced combination of global exploration and local exploitation, enabling the anchor configuration to follow the real distribution of object shapes and facilitating stable optimization under high data variability [

44].

Analyzing the presented architecture, we will describe the main stages. At the first stage, the initial populations are initialized, after which two complementary components are launched in parallel: a genetic algorithm that implements evolutionary parameter refinement, and a bio-inspired algorithm that ensures the generation and diversification of a set of solutions. Information exchange between algorithms is carried out through a universal container that accumulates intermediate results, calculates metrics, excludes duplicate and ineffective solutions, and forms control signals for the adaptability controller.

The adaptability controller analyzes the state of the computational process based on a set of metrics: the convergence rate

, the population diversity

, and the decision quality improvement dynamics

. In this case, the functional roles of the algorithms change depending on the ratio of these metrics if the following condition is met:

where

,

are threshold values that determine local search stagnation. A decrease in the convergence rate

with a simultaneous decrease in diversity

is interpreted as a sign of excessive population concentration and exhaustion of the local search potential, leading to the migration of solutions and the redistribution of the functional roles of algorithms.

Thus, a continuous self-adaptation loop is implemented, ensuring a coordinated distribution of computational resources between global and local optimization processes. Thus, at the global search stage, an evolutionary mechanism for refining anchor frame configurations is implemented by a genetic algorithm, whose main function is to explore the parameter space and generate a set of promising solutions, with each solution in the population encoded by a vector of parameters:

where

and

are the width and height of the

k-th frame of the

m-th solution, and

K is the number of anchor frames. In turn, the quality of chromosomes is determined by the fitness function, which includes the intersection metric (IoU) and parameter variance regularization:

where

is the real bounding box,

is the anchor box, and

is the coefficient that regulates the ratio of approximation accuracy and solution diversity. Although the value of

was selected empirically, its choice was further validated by sensitivity assessments conducted in the range

, which is typical for regularization principles in evolutionary swarm processes. Preliminary tests showed that

leads to an increase in the variance of the anchor frame parameters and a decrease in convergence stability, while

leads to a reordering of solutions and an outlier in IoU coverage. The value

was adopted as a compromise that provides a balance between the variability of candidate solutions and the stabilization of the optimization process.

The selection of parent chromosomes

and

is carried out in proportion to the value of the fitness function

f (

19), maintaining the priority of effective solutions, while new offspring are formed by means of arithmetic crossover [

45]:

and maintaining population diversity and preventing premature convergence is performed by a mutation operator that adds random Gaussian noise to each gene [

42]:

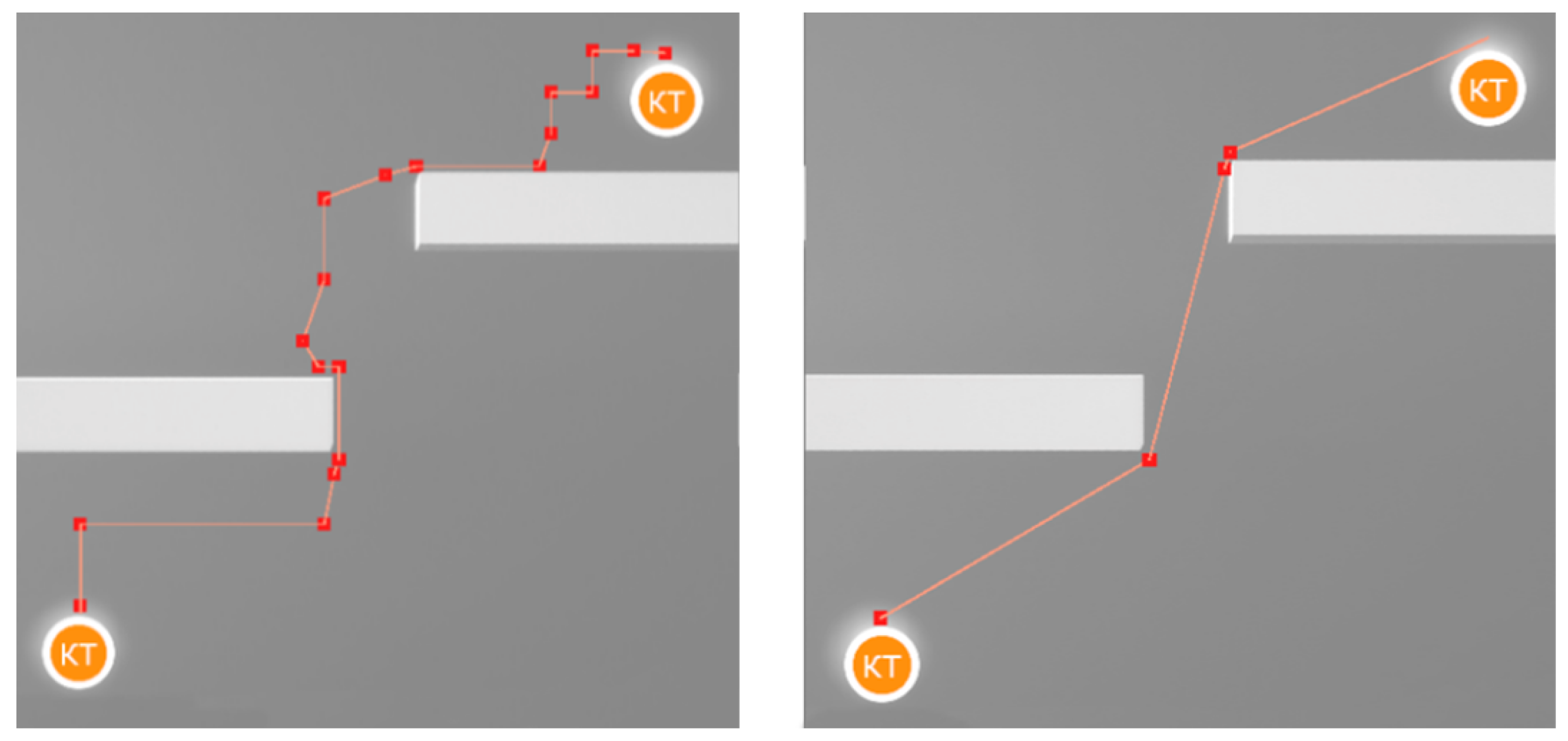

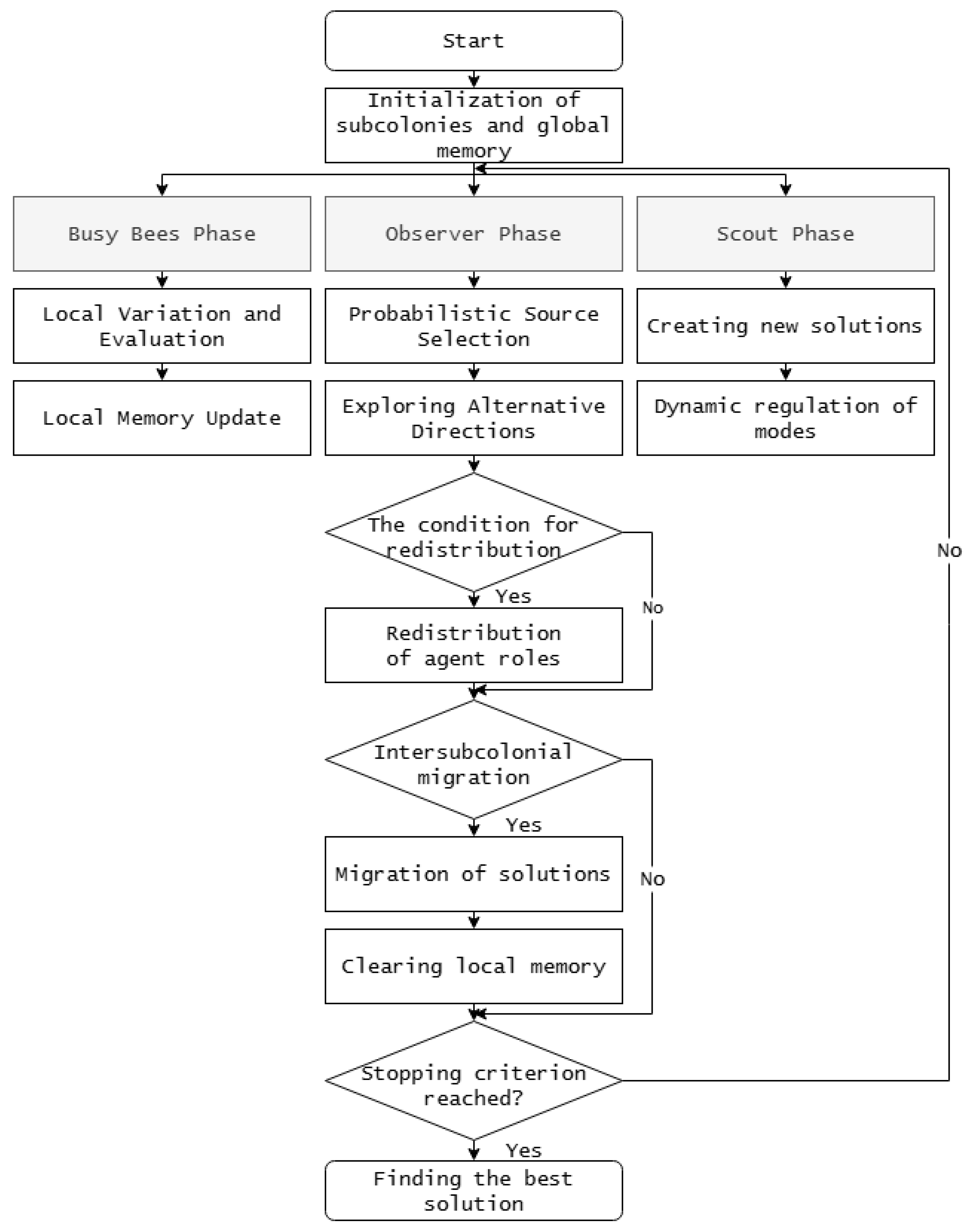

In parallel with the genetic algorithm, a modified artificial bee colony (ABC) algorithm functions, including a multi-colony structure and adaptive redistribution of agent roles. The structure of the proposed modification of the bee colony algorithm is shown in

Figure 10.

Formally, the population of agents

is divided into a set of autonomous subcolonies, each of which functions in its own feature subspace. The division into subcolonies is performed by the adaptability controller based on the current diversity metric

. Within each subcolony, decisions are represented as feature vectors:

where

,

are the width and height of the

k-th anchor frame, respectively. Three phases are implemented during the optimization process: busy bees, observers, and scouts. The busy bees phase is characterized by the execution of local variations of fixed solutions, accompanied by an evaluation of the objective function, in order to refine the parameters of the anchor frames in the vicinity of the current positions. The update of the solution is described by the expression

where

is a randomly selected solution of the current subcolony,

is a parameter that regulates the scale of local changes, dynamically transformed depending on the diversity of the population:

where

is the diversity metric,

is the centroid of the current solutions.

In the observer phase, a probabilistic selection of food sources is implemented, determined by the combined influence of the objective function and the uniqueness metric of solutions, which characterizes the degree of difference between individuals within the subcolony:

where

is the value of the objective Function (

19) as applied to a particular solution,

is the uniqueness index reflecting the degree of difference between the solution and the other elements of the subcolony, determined by the inverse dependence on the average distance to neighboring solutions:

where

is the Mahalanobis distance,

is the covariance matrix of the parameters of the current subcolony. The application of this mechanism prevents the concentration of computational resources on a limited set of solutions, supporting the diversification of search directions and increasing the probability of discovering new promising areas.

In turn, the explorer phase is activated when the efficiency of local search procedures decreases and is aimed at exploring poorly studied regions of the parametric space. New solutions are generated using the expression

where

and

are the best, random, and least effective solutions of the current iteration, respectively. This form of updating provides a stochastically directed shift of the search trajectory from areas of low performance to promising regions of the feature space.

At the same time, information exchange between subcolonies and the evolutionary component is carried out through the global memory of the container:

where the operator

saves the

P most effective solutions,

implements the selection of elements with probability

.

After executing the GA and ABC operators, the updated solutions are consolidated into a combined set

, from which a new population is formed:

Thus, the final set of solutions represents a balanced set of anchor frames, characterized by uniform distribution of parameters and resistance to stochastic disturbances, forming a consistent parametric space. The procedure description of the algorithm is provided in

Appendix A.