Assessing and Prioritizing Service Innovation Challenges in UAE Government Entities: A Network-Based Approach for Effective Decision-Making

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To analyze and visualize the interrelationships between challenges impacting innovation in public services by UAE government entities to understand better how these challenges influence each other.

- To provide decision-makers with a tool to swiftly distinguish the most critical challenges and the root causes of innovation ineffectiveness.

- To recommend actionable strategies for tackling the most critical challenges identified through the analysis.

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Literature Review

3.1. Innovation in the Public Sector

3.2. Public Sector Innovation Within the UAE

3.3. Challenges in the Public Sector

4. Methodological Approach

4.1. Identification of Challenges

4.2. Correlation Analysis of Challenges

4.3. Network Centrality Analysis

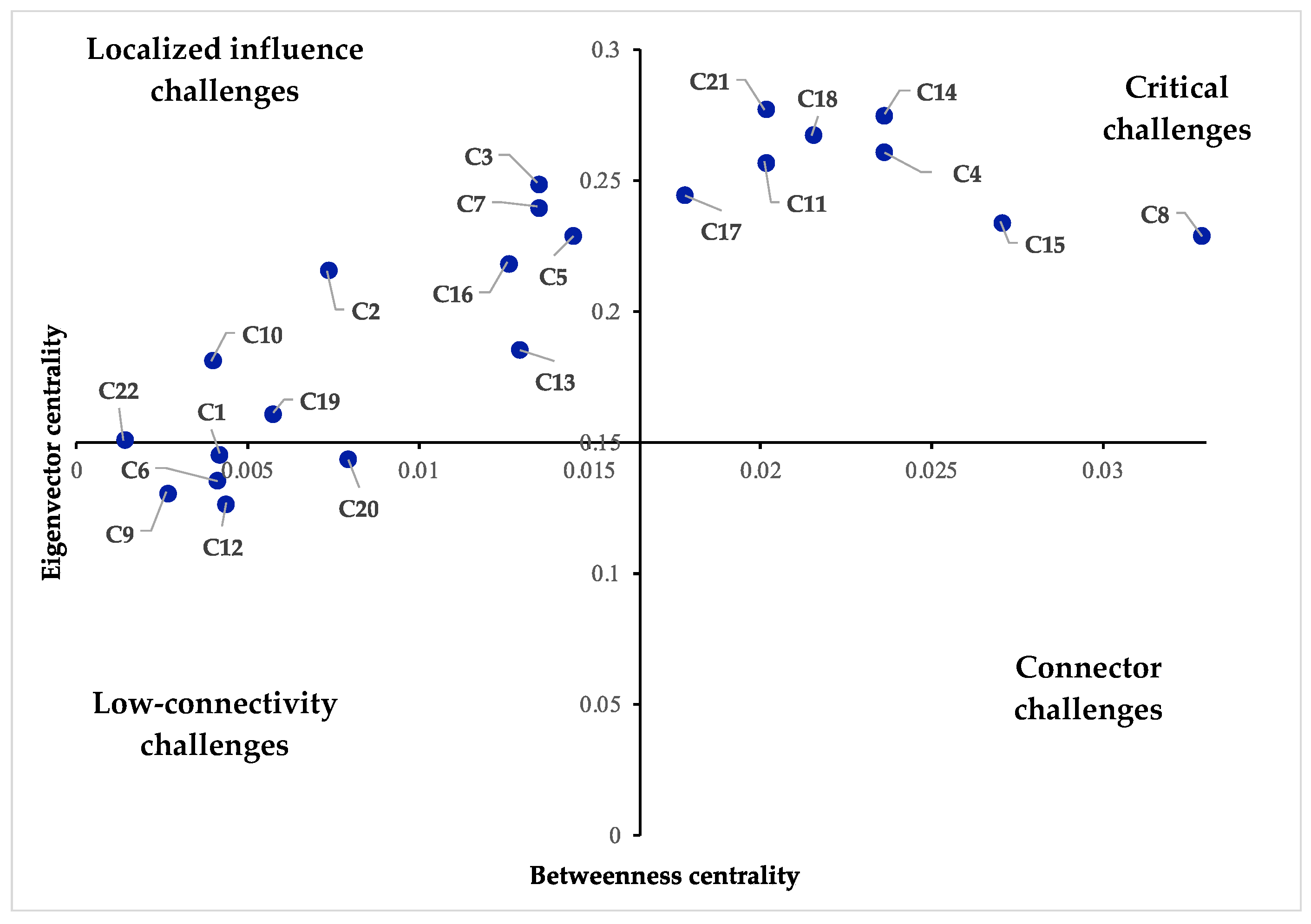

| Challenges | Betweenness Centrality | Eigenvector Centrality |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | 0.004171 | 0.145685 |

| C2 | 0.007325 | 0.215564 |

| C3 | 0.013472 | 0.248666 |

| C4 | 0.023597 | 0.260626 |

| C5 | 0.014524 | 0.228622 |

| C6 | 0.004112 | 0.135462 |

| C7 | 0.013472 | 0.239897 |

| C8 | 0.032888 | 0.228611 |

| C9 | 0.002640 | 0.130718 |

| C10 | 0.003959 | 0.181190 |

| C11 | 0.020128 | 0.257091 |

| C12 | 0.004352 | 0.126861 |

| C13 | 0.012937 | 0.185349 |

| C14 | 0.023597 | 0.275147 |

| C15 | 0.027013 | 0.234005 |

| C16 | 0.012617 | 0.218545 |

| C17 | 0.017781 | 0.244437 |

| C18 | 0.021492 | 0.267401 |

| C19 | 0.005730 | 0.161052 |

| C20 | 0.007918 | 0.143626 |

| C21 | 0.020128 | 0.277100 |

| C22 | 0.001385 | 0.151082 |

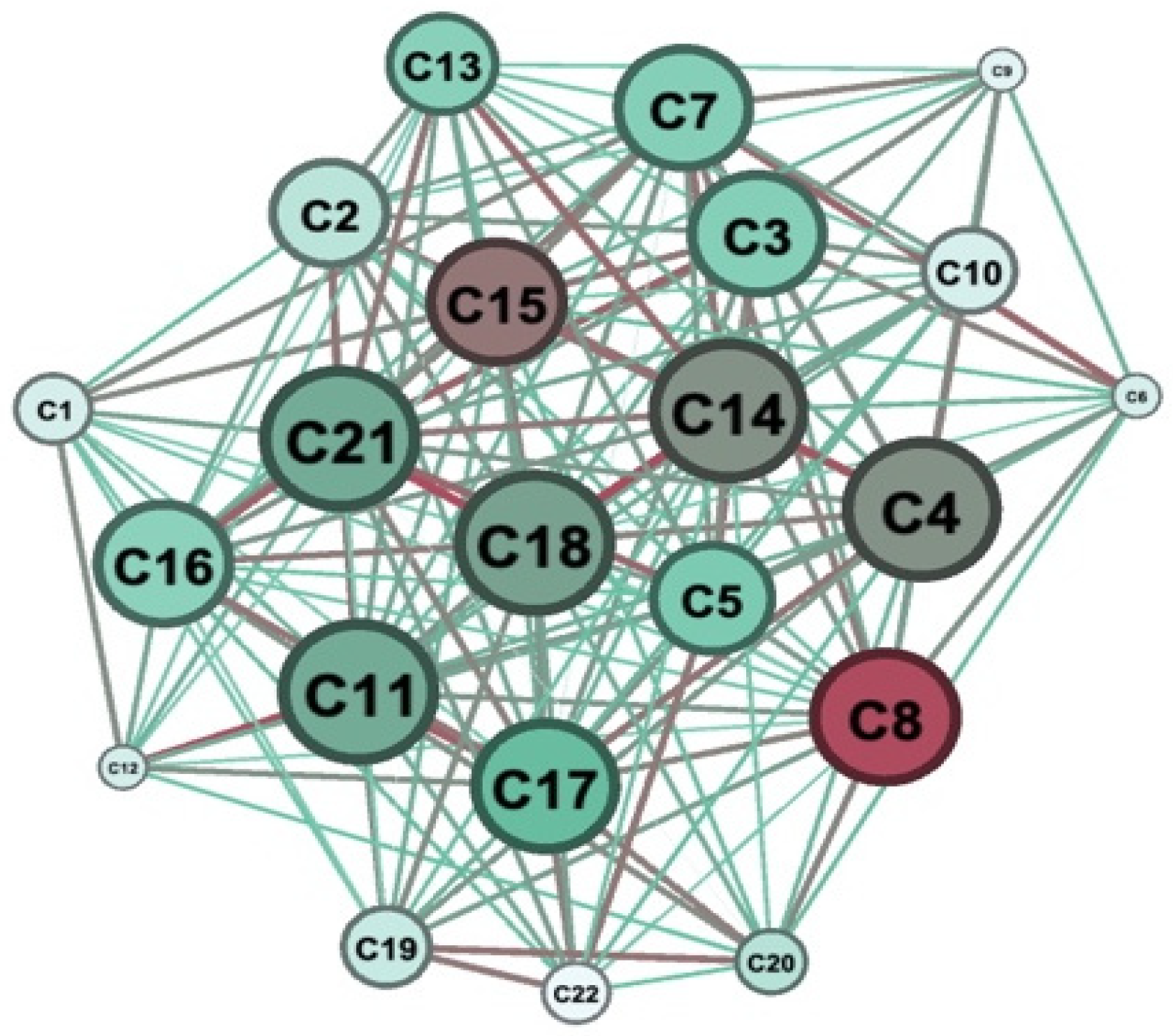

4.4. Visualization of Relationships

4.5. Classification of Challenges

5. Discussion

5.1. Bridging Challenges in the Network

- C8 bridges between C11, C18, and C21: “Resistance to change among employees” (C8) reinforces demotivation (C11) as employees feel disengaged from or resistant to new initiatives. This resistance also intensifies coordination problems (C18), as employees may resist collaborating effectively. Furthermore, resistance hinders the adoption of structured innovation processes (C21), making formalizing efforts to drive innovation difficult.

- C15 bridges between C18, C7, and C20: “Overlapping functions between departments” (C15) often lead to poor internal coordination and communication (C18) as employees struggle to navigate unclear roles and responsibilities. This overlap is compounded by rigid rules and processes (C7), which prevent departments from adopting flexible approaches to collaboration. The lack of integration between government entities (C20) further intensifies this issue, as interdepartmental inefficiencies spill over into external collaborations. Together, these challenges create a cycle of disorganization and inefficiency that significantly hinders innovation.

- C4 bridges between C3, C12, and C20: The “lack of information about technology to innovate in services” (C4) acts as a bottleneck that impacts employees’ ability to apply knowledge gained from training (C3). Even well-trained employees may find themselves ill-equipped to innovate effectively without adequate technological information. Additionally, this lack of information weakens employees’ incentives and rewards (C12), as their inability to utilize new technologies diminishes motivation and recognition for innovation. Furthermore, “poor integration between government entities for shared services” (C20) exacerbates this challenge, as fragmented systems fail to provide the technological insights or shared resources necessary for driving service innovation.

- C14 bridges between C9, C8, and C13: The “service-oriented-thinking gap between managers and employees” (C14) creates misalignment in innovation efforts, notably when top management lacks commitment and support (C9). This gap reinforces “a culture of resistance to change” (C8), as employees perceive a misalignment between managerial expectations and practical realities. Additionally, “the absence of a customer-centric mindset” (C13) further widens this gap, as neither managers nor employees are aligned on addressing the needs of current and future customers. This misalignment undermines innovation efforts, creating systemic inefficiencies and limiting the government entity’s ability to adapt to evolving service demands.

- C18 bridges between C15, C8, and C21: Coordination and communication issues (C18) often arise from overlapping departmental functions (C15), where unclear roles and responsibilities create inefficiencies. Poor coordination also deepens cultural resistance (C8), as employees struggle to align with unclear communication processes. Additionally, without addressing C18, efforts to implement formalized innovation processes (C21) often fail, as coordination is crucial for systemic alignment and execution.

5.2. Highly Interconnected Challenges

5.3. Classifying Challenges

5.3.1. Critical Challenges

5.3.2. Connector Challenges

5.3.3. Localized Influence Challenges

5.3.4. Low-Connectivity Challenges

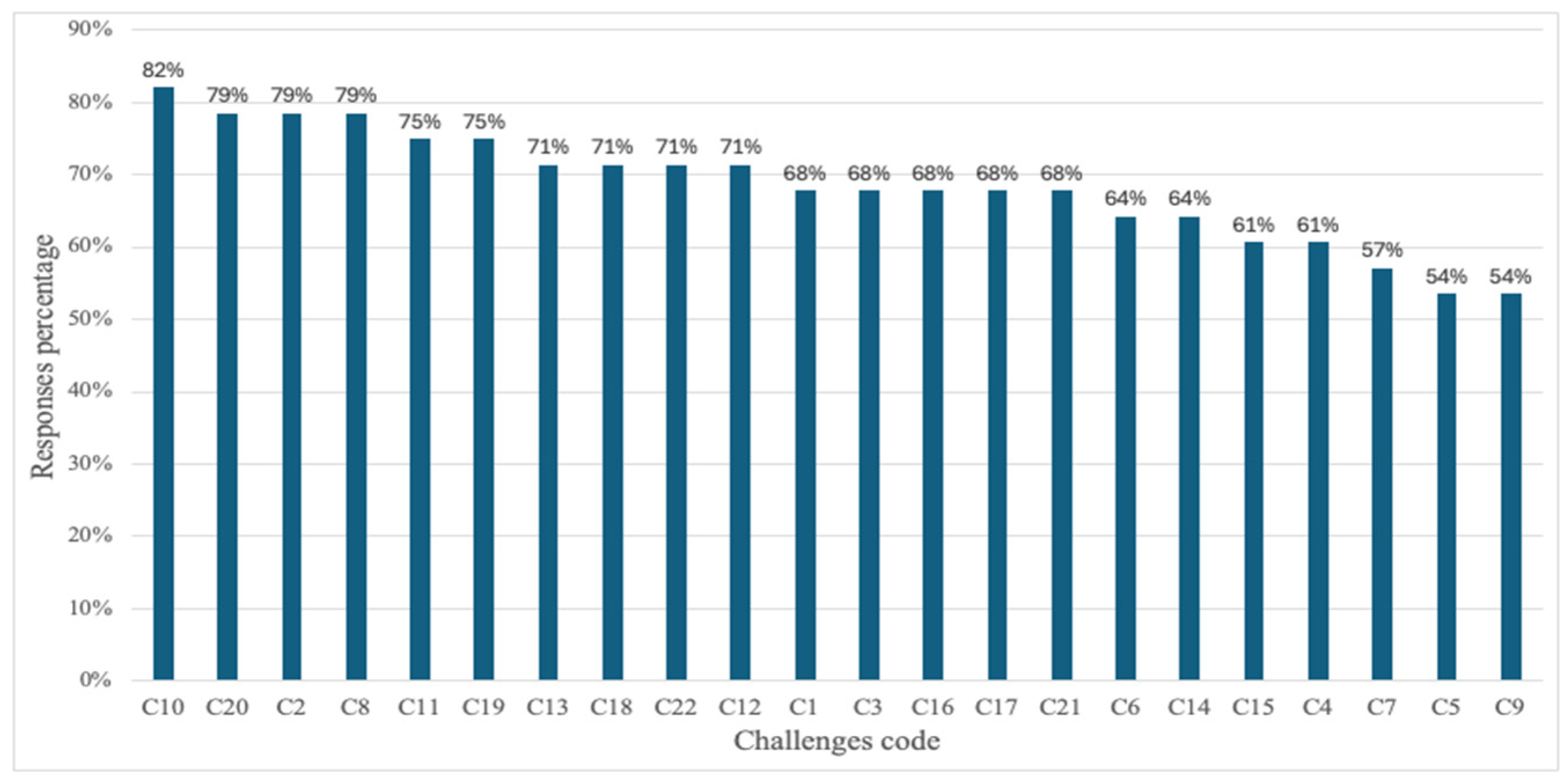

5.4. Prioritizing Challenges: Survey Results vs. Network Analysis

5.5. Strategies for Addressing Critical Challenges

5.6. Leveraging Open Innovation to Address Critical Challenges

6. Conclusions

6.1. Concluding Remarks

6.2. Public Service Innovation Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Setyawan, A.A.; Misidawati, D.N.; Aryatama, S.; Jaya, A.A.N.A.; Wiliana, E. Exploring Innovative Strategies for Sustainable Organizational Growth. Global 2024, 2, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yin, X.; Mei, L. Holistic Innovation: An Emerging Innovation Paradigm. Int. J. Innov. Stud. 2018, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldo, A.; Messeni Petruzzelli, A. Origins of Knowledge and Innovation in R&D Alliances: A Contingency Approach. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2015, 27, 461–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, H.R.; Wang, W.; Wei, C.-P.; Hsu, S.H.-Y.; Chiu, H.-C. Service Innovation Readiness: Dimensions and Performance Outcome. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 53, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmarkar, U. Will You Survive the Services Revolution? Harv. Bus. Rev. 2004, 82, 100–107+138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Helkkula, A.; Kowalkowski, C.; Tronvoll, B. Archetypes of Service Innovation: Implications for Value Cocreation. J. Serv. Res. 2018, 21, 284–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-H.; Wang, C.-H.; Huang, S.-Z.; Shen, G.C. Service Innovation and New Product Performance: The Influence of Market-Linking Capabilities and Market Turbulence. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 172, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, S.; Ojiako, U.; Papadopoulos, T.; Shafti, F.; Koh, L.; Kanellis, P. Synchronicity and Alignment of Productivity: The Real Value from Service Science? Prod. Plan. Control 2012, 23, 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansury, M.A.; Love, J.H. Innovation, Productivity and Growth in US Business Services: A Firm-Level Analysis. Technovation 2008, 28, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapiyi, S.; Suradi, N.R.M.; Mustafa, Z. Major Trends in Public Sector Innovation: A Bibliometric Analysis. J. Kejuruter. 2024, 36, 709–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, G.; Mulgan, G.; Muers, S. Creating Public Value: An Analytical Framework for Public Service Reform; Strategy Unit, Cabinet Office: London, UK, 2002; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, R.M. Innovation Type and Diffusion: An Empirical Analysis of Local Government. Public Adm. 2006, 84, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinar, E.; Trott, P.; Simms, C. A Systematic Review of Barriers to Public Sector Innovation Process. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 264–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzanjal, A.; Bashir, H. Service Innovation Challenges in UAE Government Entities: Identification and Examination of the Impact of Organizational Size and Excellence Model Implementation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. 2024, 10, 100364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H. The Logic of Open Innovation: Managing Intellectual Property. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2003, 45, 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demircioglu, M.A. Public Sector Innovation: Sources, Benefits, and Leadership. Int. Public Manag. J. 2024, 27, 190–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petchenko, M.; Telnova, H.; Yakushev, O.; Kuzminova, O. The Evolution of the Theory of Innovation Ecosystems in the Context of Strategisation. Econ. Ecol. Socium 2024, 8, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.L. The Role of Interorganizational Relationships in Public Sector Innovation: The Case of the Community Risk Intervention Teams; Leiden University: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Uhl-Bien, M.; Marion, R.; McKelvey, B. Complexity Leadership Theory: Shifting Leadership from the Industrial Age to the Knowledge Era. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, F.; Magni, D.; Papa, A.; Corsi, C. Knowledge Hiding in Socioeconomic Settings: Matching Organizational and Environmental Antecedents. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 135, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. The Resource-Based Theory of the Firm. Organ. Sci. 1996, 7, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, F.; Bigliardi, B. Does Different NPD Project’s Characteristics Lead to the Establishment of Different NPD Networks? A Knowledge Perspective. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2017, 29, 1196–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. Toward a Knowledge-Based Theory of the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuotto, V.; Le Loarne Lemaire, S.; Magni, D.; Maalaoui, A. Extending Knowledge-Based View: Future Trends of Corporate Social Entrepreneurship to Fight the Gig Economy Challenges. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqdliyan, R.; Setiawan, D. Antecedents and Consequences of Public Sector Organizational Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. 2023, 9, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkader, B.; Magni, D.; Cillo, V.; Papa, A.; Micera, R. Aligning Firm’s Value System and Open Innovation: A New Framework of Business Process Management Beyond the Business Model Innovation. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2020, 26, 999–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callender, G. Public Sector Organizations. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Smelser, N.J., Baltes, P.B., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 12581–12585. ISBN 978-0-08-043076-8. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Fostering Innovation in the Public Sector; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017; ISBN 978-92-64-27087-9. [Google Scholar]

- Saragih, J. Innovation in Government: Strategies for Effective Public Service Delivery. Int. J. Sci. Res. Manag. 2024, 12, 6661–6671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulgan, G.; Albury, D. Innovation in the Public Sector; Strategy Unit, Cabinet Office: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wipulanusat, W.; Panuwatwanich, K.; Stewart, R.A.; Sunkpho, J. Drivers and Barriers to Innovation in the Australian Public Service: A Qualitative Thematic Analysis. Eng. Manag. Prod. Serv. 2019, 11, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raipa, A.; Giedraityte, V. Innovation Process Barriers in Public Sector: A Comparative Analysis in Lithuania and the European Union. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 9, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Powering European Public Sector Innovation: Towards a New Architecture: Report of the Expert Group on Public Sector Innovation; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Masuku, M.M.; Jili, N.N. Public Service Delivery in South Africa: The Political Influence at Local Government Level. J. Public Aff. 2019, 19, e1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batley, R.; Mcloughlin, C. The Politics of Public Services: A Service Characteristics Approach. World Dev. 2015, 74, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwan, K.R.; Markland, R.E. Integrating Service Design Principles and Information Technology to Improve Delivery and Productivity in Public Sector Operations: The Case of the South Carolina DMV. J. Oper. Manag. 2006, 24, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterson, W.; Ebbers, W.; Van Dijk, J. Personalization in the Public Sector: An Inventory of Organizational and User Obstacles Towards Personalization of Electronic Services in the Public Sector. Gov. Inf. Q. 2007, 24, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceder, A.A.; Jiang, Y. Route Guidance Ranking Procedures with Human Perception Consideration for Personalized Public Transport Service. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. 2020, 118, 102667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Tao, D. The Roles of Trust, Personalization, Loss of Privacy, and Anthropomorphism in Public Acceptance of Smart Healthcare Services. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 127, 107026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, C.; Bugge, M.M. Public Sector Innovation—From Theory to Measurement. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2013, 27, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demircioglu, M.A.; Audretsch, D.B. Conditions for Innovation in Public Sector Organizations. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Busisman, H.; Bekker, A.; McCulloch, C. Innovative Capacity of Governments: A Systemic Framework; OECD Working Papers on Public Governance; OECD: Paris, France, 2022; Volume 51. [Google Scholar]

- Pólvora, A.; Nascimento, S. Foresight and Design Fictions Meet at a Policy Lab: An Experimentation Approach in Public Sector Innovation. Futures 2021, 128, 102709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlborg, P.; Kindström, D.; Kowalkowski, C. The Evolution of Service Innovation Research: A Critical Review and Synthesis. Serv. Ind. J. 2014, 34, 373–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, K. What Can Open Innovation Be Used for and How Does It Create Value? Gov. Inf. Q. 2020, 37, 101459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, M.; Dumay, J.; Garlatti, A. Public Sector Knowledge Management: A Structured Literature Review. J. Knowl. Manag. 2015, 19, 530–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K. Managing Innovation in Government Organizations: Identifying and Overcoming Barriers; Institute of Management Studies: Ghaziabad, India, 2014; Discussion paper. [Google Scholar]

- Yusof, N.A.M.; Rafee, S.A.; Ishak, A.A.; Razali, M.R.; Saimy, I.S. Challenges and Barriers in Public Services Innovations in Malaysia. STIPM J. 2022, 7, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodolica, V.; Spraggon, M.; Saleh, N. Innovative Leadership in Leisure and Entertainment Industry: The Case of the UAE as a Global Tourism Hub. Int. J. Islam. Middle East. Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prime Minister’s Office UAE. National Innovation Strategy; Prime Minister’s Office: Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2015.

- Ministry of Cabinet Affairs. UAE Centennial Plan 2071. Available online: https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/strategies-initiatives-and-awards/strategies-plans-and-visions/innovation-and-future-shaping/uae-centennial-2071 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Zero Government. Bureaucracy Programme. Available online: https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/strategies-initiatives-and-awards/strategies-plans-and-visions/government-services-and-digital-transformation/zero-government-bureaucracy-programme (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Brown, L.; Osborne, S.P. Risk and Innovation: Towards a Framework for Risk Governance in Public Services. Public Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 186–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.A.; Arantes, A.; Valadares Tavares, L. Evidence of the Impacts of Public E-Procurement: The Portuguese Experience. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2013, 19, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, J.R.; Wilson, W.J. Poverty, Politics, and a “Circle of Promise”: Holistic Education Policy in Boston and the Challenge of Institutional Entrenchment. J. Urban Aff. 2013, 35, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agolla, J.E.; Van Lill, J. Assessment of Innovation in Public Sector Organisations in Kenya. In Proceedings of the Academic Conferences International Limited, Belfast, UK, 17 September 2014; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Biesbroek, G.R.; Termeer, C.J.A.M.; Klostermann, J.E.M.; Kabat, P. Rethinking Barriers to Adaptation: Mechanism-Based Explanation of Impasses in the Governance of an Innovative Adaptation Measure. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 26, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, H.; Dewulf, G.; Voordijk, H. The Barriers to Govern Long-Term Care Innovations: The Paradoxical Role of Subsidies in a Transition Program. Health Policy 2014, 116, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzamel, M.; Hyndman, N.; Johnsen, A.; Lapsley, I. Reforming Central Government: An Evaluation of an Accounting Innovation. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2014, 25, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, F.; Brunori, G.; Di Iacovo, F.; Innocenti, S. Co-Producing Sustainability: Involving Parents and Civil Society in the Governance of School Meal Services. a Case Study from Pisa, Italy. Sustainability 2014, 6, 1643–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovseiko, P.; O’Sullivan, C.; Powell, S.; Davies, S.; Buchan, A. Implementation of Collaborative Governance in Cross-Sector Innovation and Education Networks: Evidence from the National Health Service in England. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, P91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocque, M.; Welsh, B.C.; Greenwood, P.W.; King, E. Implementing and Sustaining Evidence-Based Practice in Juvenile Justice: A Case Study of a Rural State. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2014, 58, 1033–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strand, Ø.; Alnes, R.E.; Schaathun, H.G. Drivers and Barriers in Public Sector Innovations, Regional Perspectives and Lessons Learned from the ALV Project. In Proceedings of the Fjord Conference 2014, Loen, Norway, 19–20 June 2014; pp. 155–177. [Google Scholar]

- Susha, I.; Grönlund, Å. Context Clues for the Stall of the Citizens’ Initiative: Lessons for Opening up e-Participation Development Practice. Gov. Inf. Q. 2014, 31, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, A. E-Governance Innovation: Barriers and Strategies. Gov. Inf. Q. 2015, 32, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelkonen, A.; Valovirta, V. Can Service Innovations Be Procured? An Analysis of Impacts and Challenges in the Procurement of Innovation in Social Services. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 28, 384–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotnikof, M. Negotiating Collaborative Governance Designs: A Discursive Approach. Innov. J. 2015, 20, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Van Buuren, A.; Eshuis, J.; Bressers, N. The Governance of Innovation in Dutch Regional Water Management: Organizing Fit Between Organizational Values and Innovative Concepts. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 17, 679–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenbabic, D. Fostering Innovation Through Innovation Friendly Procurement Practices: A Case Study of Danish Local Government Procurement. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 28, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agolla, J.E.; Van Lill, J.B. An Empirical Investigation into Innovation Drivers and Barriers in Public Sector Organisations. Int. J. Innov. 2016, 8, 404–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caloghirou, Y.; Protogerou, A.; Panagiotopoulos, P. Public Procurement for Innovation: A Novel Egovernment Services Scheme in Greek Local Authorities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 103, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, H.; Bekkers, V.; Tummers, L. Innovation in the Public Sector: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda. Public Adm. 2016, 94, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moonesar, I.A.; Stephens, M.; Batey, M.; Hughes, D.J. Government Innovation and Creativity: A Case of Dubai. In Future Governments; Actions and Insights—Middle East North Africa; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2019; Volume 7, pp. 135–155. ISBN 978-1-78756-359-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cinar, E.; Trott, P.; Simms, C. An International Exploration of Barriers and Tactics in the Public Sector Innovation Process. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 326–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozioł-Nadolna, K.; Beyer, K. Barriers to Innovative Activity in the Sustainable Development of Public Sector Organizations. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 192, 4376–4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, D.; Waldorff, S.B.; Steffensen, T. Public Value through Innovation: Danish Public Managers’ Views on Barriers and Boosters. Int. J. Public Adm. 2021, 44, 1264–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolhosseinzadeh, M.; Mohammadi, F.; Abdolhamid, M. Identifying and Prioritizing Barriers and Challenges of Social Innovation Implementation in the Public Sector. Eur. Public Soc. Innov. Rev. 2023, 8, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singler, S.; Guenduez, A.A. Barriers to Public Sector Innovation in Switzerland: A Phase-Based Investigation. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2025, 84, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saatçioğlu, Ö.Y.; Özmen, Ö.N.T. Analyzing the Barriers Encountered in Innovation Process Through Interpretive Structural Modelling: Evidence from Turkey. Yönetim Ekon. Derg. 2010, 17, 207–225. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, J.L. The Sociometry Reader; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1960; p. 773. [Google Scholar]

- Bashir, H.; Alsyouf, I.; Alshamsi, H.; Abdel-Razek, R.H.; Gardoni, M. The Association Between Structural Organization Characteristics and Innovation in the Context of the UAE Service Sector: An Empirical Investigation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 7th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Applications (ICIEA), Bangkok, Thailand, 16–18 April 2020; pp. 1060–1064. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, K.Y.; Shen, G.Q.; Yang, R.J.; Li, C.Z. Investigating Key Challenges in Major Public Engineering Projects by a Network-Theory Based Analysis of Stakeholder Concerns: A Case Study. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryke, S.; Badi, S.; Soundararaj, B.; Addyman, S. Self-Organizing Networks in Complex Infrastructure Projects. Proj. Manag. J. 2016, 49, 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaabi, H.A.; Bashir, H. Analyzing Interdependencies in a Project Portfolio Using Social Network Analysis Metrics. In Proceedings of the 2018 5th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Applications (ICIEA), Singapore, 26–28 April 2018; pp. 490–494. [Google Scholar]

- Marin, A.; Wellman, B. Social Network Analysis: An Introduction. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Network Analysis; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2011; pp. 11–25. ISBN 978-1-84787-395-8. [Google Scholar]

- Warfield, J.N. Toward Interpretation of Complex Structural Models. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1974, SMC-4, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duperrin, J.-C.; Godet, M. Hierarchization Method for the Elements of a System. An Attempt to Forecast a Nuclear Energy System in Its Societal Context; French Atomic Energy Commission (CEA): Paris, France, 1973; p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- Fontela, E.; Gabus, A. The DEMATEL Observer; Battelle Geneva Research Center: Geneva, Switzerland, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Shaqiri, M.; Iljazi, T.; Kamberi, L.; Ramani-Halili, R. Differences Between the Correlation Coefficients Pearson, Kendall and Spearman. J. Nat. Sci. Math. UT 2023, 8, 392–397. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, S. Weighted Network Analysis: Applications in Genomics and Systems Biology, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 1-4419-8819-X. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, D.L.; Shneiderman, B.; Smith, M.A.; Himelboim, I. Social Network Analysis: Measuring, Mapping, and Modeling Collections of Connections. In Analyzing Social Media Networks with NodeXL; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 31–51. ISBN 978-0-12-817756-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, S.; Faust, K. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications, 1st ed.; Structural Analysis in the Social Sciences; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994; ISBN 978-0-521-38707-1. [Google Scholar]

- Junior, A.; Emmendoerfer, M.; Silva, M. Innovation Labs in the Light of the New Public Service Model. RAM Rev. Adm. Mackenzie 2024, 25, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UAE Hackathon. UAE Hackathon Journey. Available online: https://hackathon.ae (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Damawan, A.H.; Azizah, S. Resistance to Change: Causes and Strategies as an Organizational Challenge. In Proceedings of the 5th ASEAN Conference on Psychology, Counselling, and Humanities (ACPCH 2019), Gelugor, Malaysia, 2–3 November 2019; Atlantis Press: Penang, Malaysia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Warrick, D.D. Revisiting Resistance to Change and How to Manage It: What Has Been Learned and What Organizations Need to Do. Bus. Horiz. 2023, 66, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, S.; Marin-Cadavid, C. A Practice Approach to Fostering Employee Engagement in Innovation Initiatives in Public Service Organisations. Public Manag. Rev. 2022, 25, 2027–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, M.; Vorobyova, K.; Rauf, M. The Effect of Total Rewards System on the Performance of Employees with a Moderating Effect of Psychological Empowerment and the Mediation of Motivation in the Leather Industry of Bangladesh. Eng. Lett. 2021, 29, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.; Santos, E.; Santos, T.; Oliveira, M. The Influence of Empowerment on the Motivation of Portuguese Employees—A Study Based on a Structural Equation Model. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, M.L.; Kjeldsen, A.M.; Pallesen, T. Distributed Leadership and Performance-Related Employee Outcomes in Public Sector Organizations. Public Adm. 2023, 101, 500–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahto, R.V.; Davis, P.S. Information Flow and Strategic Consensus in Organizations. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowarczyk, Z. Knowledge Sharing in Distributed Teams—The Impact of Virtual Collaboration Tools. Int. Multidiscip. Sci. GeoConf. SGEM 2024, 2024, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, Z.Z.; Arham, A.F.; Abdul, S.A.; Ahmad, H.M. Towards Malaysia Madani: Do Leadership Styles Influence Innovative Work Behavior? A Conceptual Framework for the Malaysian Public Sector. Inf. Manag. J. 2024, 16, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriyani, Y.; Suripto; Yohanitas, W.A.; Kartika, R.S.; Marsono. Adaptive Innovation Model Design: Integrating Agile and Open Innovation in Regional Areas Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. 2024, 10, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, F.; Jantan, A. Beyond Barriers: Innovative Collaboration for Enhancing Malaysia’s Healthcare Future. Int. Bus. Manag. 2024, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desouza, K.C.; Dombrowski, C.; Awazu, Y.; Baloh, P.; Papagari, S.; Jha, S.; Kim, J.Y. Crafting Organizational Innovation Processes. Innov.-Manag. Policy Pract. 2009, 11, 6–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.; Ince, H.; Imamoglu, S.Z. Effects of Standardized Innovation Management Systems on Innovation Ambidexterity and Innovation Performance. Sustainability 2024, 17, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunphy, S.M.; Herbig, P.R.; Howes, M.E. The Innovation Funnel. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 1996, 53, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhaverbeke, W.; Cloodt, M. Theories of the Firm and Open Innovation. In New Frontiers in Open Innovation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 256–278. ISBN 978-0-19-968246-1. [Google Scholar]

- Palavesh, S. The Role of Open Innovation and Crowdsourcing in Generating New Business Ideas and Concepts. Int. J. Res. Publ. Semin. 2019, 10, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Torfing, J. Co-Creation: The New Kid on the Block in Public Governance. Policy Politics 2021, 49, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figenschou, T.; Li-Ying, J.; Tanner, A.; Bogers, M. Open Innovation in the Public Sector: A Literature Review on Actors and Boundaries. Technovation 2024, 131, 102940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergel, I. Open Innovation in the Public Sector: Drivers and Barriers for the Adoption of Challenge. Gov. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 726–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fan, Y.; Nie, L. Making Governance Agile: Exploring the Role of Artificial Intelligence in China’s Local Governance. Public Policy Adm. 2025, 40, 276–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldoseri, A.; Al-Khalifa, K.N.; Hamouda, A.M. Methodological Approach to Assessing the Current State of Organizations for AI-Based Digital Transformation. ASI 2024, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Shang, K.; Small, M.; Chao, N. Information Overload: How Hot Topics Distract from News-Covid-19 Spread in the US. NSO 2023, 2, 20220051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Prior Studies Targeted Population/Year of Study | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [42] Public sector institutions, Nordic countries/2013 | [55] Public services organizations, UK/2013 | [56] Public sector e-procurement, Portugal/2013 | [57] Municipalities, USA/2013 | [58] Public sector organizations, Kenya/2014 | [59] Municipality, The Netherlands/2014 | [60] Public sector (healthcare), The Netherlands/2014 | [61] Central government—Scottish Parliament, Scotland/2014 | [62] Public services (education), Italy/2014 | [63] Healthcare and education, England/2014 | [34] Public sector in Lithuania and European Union/2014 | [64] Public sector (justice), USA/2014 | [65] Public sector organizations (healthcare), Norway/2014 | [66] European parliament/2014 | [67] Government organizations, The Netherlands/2015 | [68] Public services in municipalities, Finland/2015 | [69] Local government, Denmark/2015 | [70] Water management, The Netherlands/2015 | [71] Municipality, Denmark/2015 | [72] Public sector organizations, Kenya/2016 | [73] Government/municipalities, Greece/2016 | [74] Public sector innovation, USA and UK/2016 | [75] Government of Dubai, UAE/2019 | [76] Public sector in Italy, Japan, and Turkey/2021 | [77] Public institution, Poland/2021 | [78] Public sector, Denmark/2021 | [79] Public sector (justice), Iran/2023 | [27] Organization units—Central Bureau of Statistics, Indonesia/2023 | [14] Government entities, UAE/2024 | [80] Public sector innovation, Switzerland/2024 | ||

| No | Challenge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | “Administrative burdens” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | “Bureaucratic culture” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | “Communication issues” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | “Complexity challenges” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | “Environmental challenges” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | “Geographical challenges” | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | “Government policy issues” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | “Inadequate public involvement” | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | “Inadequate resources” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | “Incompatibility issues” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | “Individual/employees level challenges” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | “Issues related to businesses” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | “Issues related to NGOs” | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | “Issues related to political entities” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | “Lack of accountability” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | “Lack of commitment” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | “Lack of cooperation” | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | “Lack of funding” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | “Lack of human resources” | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | “Lack of incentives and rewards” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21 | “Lack of innovation support” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22 | “Lack of interoperability” | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 23 | “Lack of knowledge” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24 | “Lack of motivation/empowerment” | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25 | “Lack of mutual benefits” | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26 | “Lack of shared understanding” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 27 | “Lack of skills/unqualified employees” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28 | “Lack of standardization” | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 29 | “Lack of technological compatibility/information” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 30 | “Lack of top management support” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 31 | “Lack of trust” | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 32 | “Laws and regulations challenges” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 33 | “Leadership issues” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 34 | “Legal barriers to innovation” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 35 | “There are no good practices to follow.” | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 36 | “Organizational issues” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 37 | “Platform/software problems” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 38 | “Problems with training” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 39 | “User’s resistance” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40 | “Resistance to change” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 41 | “Risk avoidance/aversion” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||

| 42 | “Short-term budgets” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 43 | “Short-term focus on results” | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 44 | “Structural issues/rigidity” | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 45 | “Cost issues and longer payback” | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 46 | “Policy issues/lack of intellectual property policy” | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 47 | “Financial challenges” | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 48 | “Lack of transparency and data-sharing” | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 49 | “Partial and short-sighted mindset” | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 50 | “Absence of innovation strategy/strategy management” | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 51 | “Lack of time to innovate” | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 52 | “Rigid rules and processes” | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 53 | “Absence of customer-centric mindset” | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 54 | “Service-oriented-thinking gap” | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 55 | “Overlapping department functions” | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 56 | “Unclear value proposition” | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 57 | “Lack of integration between shared service entities” | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 58 | “Absence of innovation process” | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Code | Challenges |

|---|---|

| C1 | “Rigid budgeting process” |

| C2 | “Lack of qualified employees” |

| C3 | “Lack of training and knowledge about service innovation” |

| C4 | “Lack of information about technology to innovate in services” |

| C5 | “Lack of time dedicated to service innovation” |

| C6 | “Rigid and formal organization structure” |

| C7 | “Rigid rules and processes within the government entity” |

| C8 | “A culture of resistance to change among employees” |

| C9 | “Lack of commitment and support from top management” |

| C10 | “Managers’ tendencies to avoid risk” |

| C11 | “Lack of motivation and empowerment for employees” |

| C12 | “Lack of incentives and rewards” |

| C13 | “An absence of a customer-centric mindset to gauge and meet current and future needs” |

| C14 | “The service-oriented-thinking gap between managers and employees” |

| C15 | “Overlapping functions between departments” |

| C16 | “Absence of innovation strategy” |

| C17 | “Unclear value proposition for the new or improved service” |

| C18 | “Lack of coordination and poor internal communication between government entity departments” |

| C19 | “A gap in marketing internally for new or improved services” |

| C20 | “Lack of integration between government entities for the shared services” |

| C21 | “Absence of clear and formalized innovation process” |

| C22 | “Regulations and legislation that limit service innovation” |

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | C7 | C8 | C9 | C10 | C11 | C12 | C13 | C14 | C15 | C16 | C17 | C18 | C19 | C20 | C21 | C22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 1 | 0.418 | 0.349 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.553 | 0.388 | 0 | 0 | 0.435 | 0.546 | 0 | 0 | 0.561 | 0.382 | 0.358 | 0.352 | 0.393 | 0 | 0.495 | 0 |

| C2 | 0.418 | 1 | 0.528 | 0.609 | 0.452 | 0 | 0.483 | 0.399 | 0.367 | 0 | 0.450 | 0 | 0.527 | 0.640 | 0.431 | 0.464 | 0.479 | 0.557 | 0 | 0 | 0.627 | 0 |

| C3 | 0.349 | 0.528 | 1 | 0.602 | 0.633 | 0.579 | 0.736 | 0.472 | 0.541 | 0.526 | 0.402 | 0 | 0.386 | 0.545 | 0.603 | 0.533 | 0.513 | 0.447 | 0 | 0 | 0.670 | 0 |

| C4 | 0 | 0.609 | 0.602 | 1 | 0.514 | 0.458 | 0.526 | 0.513 | 0.445 | 0.591 | 0.460 | 0 | 0.465 | 0.712 | 0.589 | 0 | 0.621 | 0.579 | 0.517 | 0.432 | 0.525 | 0.414 |

| C5 | 0 | 0.452 | 0.633 | 0.514 | 1 | 0.517 | 0.515 | 0.509 | 0 | 0.442 | 0.528 | 0.483 | 0.512 | 0.551 | 0 | 0.396 | 0.528 | 0.503 | 0 | 0 | 0.655 | 0.611 |

| C6 | 0 | 0 | 0.579 | 0.458 | 0.517 | 1 | 0.659 | 0.537 | 0.449 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.444 | 0.418 | 0 | 0 | 0.347 | 0 | 0.417 | 0 | 0 |

| C7 | 0.553 | 0.483 | 0.736 | 0.526 | 0.515 | 0.659 | 1 | 0.592 | 0.575 | 0.492 | 0.439 | 0 | 0.386 | 0.631 | 0.556 | 0.442 | 0.325 | 0.511 | 0 | 0 | 0.595 | 0 |

| C8 | 0.388 | 0.399 | 0.472 | 0.513 | 0.509 | 0.537 | 0.592 | 1 | 0.557 | 0.492 | 0.524 | 0.345 | 0 | 0.530 | 0 | 0.381 | 0.575 | 0.374 | 0.504 | 0.568 | 0.344 | 0.350 |

| C9 | 0 | 0.367 | 0.541 | 0.445 | 0 | 0.449 | 0.575 | 0.557 | 1 | 0.535 | 0 | 0 | 0.372 | 0.478 | 0.439 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C10 | 0 | 0 | 0.526 | 0.591 | 0.442 | 0 | 0.492 | 0.492 | 0.535 | 1 | 0.458 | 0 | 0.375 | 0.477 | 0.362 | 0 | 0.433 | 0.502 | 0 | 0 | 0.482 | 0 |

| C11 | 0.435 | 0.450 | 0.402 | 0.460 | 0.528 | 0 | 0.439 | 0.524 | 0 | 0.458 | 1 | 0.722 | 0.491 | 0.469 | 0.473 | 0.540 | 0.683 | 0.540 | 0.564 | 0.556 | 0.627 | 0.467 |

| C12 | 0.546 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.483 | 0 | 0 | 0.345 | 0 | 0 | 0.722 | 1 | 0.375 | 0 | 0.351 | 0.476 | 0.541 | 0 | 0 | 0.402 | 0.447 | 0 |

| C13 | 0 | 0.527 | 0.386 | 0.465 | 0.512 | 0 | 0.386 | 0 | 0.372 | 0.375 | 0.491 | 0.375 | 1 | 0.647 | 0.436 | 0.347 | 0 | 0.484 | 0.165 | 0 | 0.605 | 0 |

| C14 | 0 | 0.640 | 0.545 | 0.712 | 0.551 | 0.444 | 0.631 | 0.530 | 0.478 | 0.477 | 0.469 | 0 | 0.647 | 1 | 0.640 | 0.524 | 0.430 | 0.738 | 0.400 | 0.385 | 0.607 | 0.398 |

| C15 | 0.561 | 0.431 | 0.603 | 0.589 | 0 | 0.418 | 0.556 | 0 | 0.439 | 0.362 | 0.473 | 0.351 | 0.436 | 0.640 | 1 | 0.516 | 0.471 | 0.595 | 0.449 | 0.417 | 0.564 | 0 |

| C16 | 0.382 | 0.464 | 0.533 | 0.340 | 0.396 | 0 | 0.442 | 0.381 | 0 | 0 | 0.540 | 0.476 | 0.347 | 0.524 | 0.516 | 1 | 0.620 | 0.597 | 0.362 | 0 | 0.675 | 0.420 |

| C17 | 0.358 | 0.479 | 0.513 | 0.621 | 0.528 | 0 | 0 | 0.575 | 0 | 0.433 | 0.683 | 0.541 | 0 | 0.430 | 0.471 | 0.620 | 1 | 0.534 | 0.451 | 0.593 | 0.581 | 0.590 |

| C18 | 0.352 | 0.557 | 0.447 | 0.579 | 0.503 | 0.347 | 0.511 | 0.374 | 0 | 0.502 | 0.540 | 0 | 0.484 | 0.738 | 0.595 | 0.597 | 0.534 | 1 | 0.543 | 0.461 | 0.739 | 0.493 |

| C19 | 0.393 | 0 | 0 | 0.517 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.504 | 0 | 0 | 0.564 | 0 | 0 | 0.400 | 0.449 | 0.362 | 0.451 | 0.543 | 1 | 0.622 | 0.366 | 0.608 |

| C20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.432 | 0 | 0.417 | 0 | 0.568 | 0 | 0 | 0.556 | 0.402 | 0 | 0.385 | 0.417 | 0 | 0.593 | 0.461 | 0.622 | 1 | 0 | 0.400 |

| C21 | 0.495 | 0.627 | 0.670 | 0.525 | 0.655 | 0 | 0.595 | 0.344 | 0 | 0.482 | 0.627 | 0.447 | 0.605 | 0.607 | 0.564 | 0.675 | 0.581 | 0.739 | 0.366 | 0.244 | 1 | 0.502 |

| C22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.414 | 0.611 | 0 | 0 | 0.350 | 0 | 0 | 0.467 | 0 | 0 | 0.398 | 0 | 0.420 | 0.590 | 0.493 | 0.608 | 0.400 | 0.502 | 1 |

| Critical Challenge | Proposed Strategies |

|---|---|

| “Lack of information about technology to innovate in services” (C4) | Addressing this challenge requires a multifaceted approach. Bridging the gap in knowledge and expertise requires building knowledge networks and partnerships with academic institutions and private technology providers. Open innovation platforms and peer learning initiatives foster idea-sharing and collaboration across departments, while innovation labs and technology demonstration projects offer safe spaces to test and showcase new solutions [95]. Establishing technology scouting units in governmental entities ensures the constant evaluation of emerging trends, complemented by continuous training programs to enhance employee technological literacy. Participation in initiatives such as hackathons [96] can help to stay informed about emerging technologies and advancements while possessing the essential tools and skills to innovate and design effective solutions in technological disciplines. The access to technology fosters innovation by enabling more efficient processes, expedites the flow of information, and strengthens a government entity’s capacity to innovate [31]. |

| “A culture of resistance to change among employees” (C8) | To overcome resistance to change in government entities, Damawan and Azizah (2020) [97] proposed seven key strategies: (1) gradual implementation of changes allows employees to gather more information and identify needs to adjust; (2) involving employees and encouraging participation; (3) cultivating psychological ownership, where individuals develop a strong sense of connection and engagement with the government entity; (4) communicating the value and advantages of the change and preparing the employees prior to actual implementation; (5) building trust and clarifying and reassuring regarding concerns that the employees have to ease their understanding of the purpose of change; (6) training, reducing workload, and considering employees’ input during the process of change; and (7) introducing a “change agent” who has the skills to facilitate change among employees with transparency about the occurring changes. In addition, effective communication [31] and awards and incentives for additional workloads [98] can mitigate employees’ tendency to resist change. |

| “Lack of motivation and empowerment for employees” (C11) | Implementing a reward system to recognize employee contributions and acknowledge their support for change can enhance engagement and motivation [99,100]. Moreover, empowerment has a positive influence; when leaders appreciate and recognize their skills and contributions, employees feel more valued, which enhances their sense of meaning and competence [101]. Providing opportunities for professional growth, such as upskilling programs and leadership development initiatives, empowers employees with the confidence to participate and add significant value. Engaging employees in organizational decision-making and co-creation initiatives, such as innovation workshops, builds a sense of ownership and accountability. Government entities can cultivate a motivated workforce that drives positive change by fostering a supportive work environment and recognizing innovation efforts. |

| “The service-oriented-thinking gap between managers and employees” (C14) | Bridging this gap requires strategies that foster alignment and collaboration. Organizing collaborative workshops and training programs centered on customer-focused strategy can promote a unified understanding of service objectives among managers and employees. Distributed leadership is a dynamic framework that fosters collaboration and narrows the gap between those in leadership and employees by delegating leadership tasks and fostering greater engagement and alignment among employees in achieving organizational goals and strategies [102]. Engaging employees in decision-making processes and ensuring transparent information flow fosters alignment, enhances their sense of ownership, promotes their engagement, and strengthens their commitment to achieving shared objectives [103]. These initiatives contribute to a more integrated approach and enhance collective commitment to delivering exceptional customer experiences. |

| “Overlapping functions between departments” (C15) | Preventing overlapping responsibilities requires clear communication and consistent collaboration. Transparency in tasks and clearly defined responsibilities and administrative roles are essential for maintaining clarity. Establishing well-defined processes and workflows further minimizes confusion. Utilizing virtual collaboration or knowledge-sharing tools fosters teamwork, facilitates efficient information exchange, and ensures everyone stays informed, creating a cohesive and efficient working environment [104]. Additionally, fostering a culture of interdepartmental collaboration through joint training and shared goals strengthens alignment and improves operational efficiency. |

| “Unclear value proposition for the new or improved service” (C17) | This ambiguity arises from insufficient communication regarding the objectives and underlying purpose of a new or improved service. Leaders should effectively convey the importance and advantages of the change and improvements in services [98]. Transformational leaders foster innovation and critical thinking by inspiring employees to align their personal values with organizational objectives; they effectively motivate individuals to embrace change, promote analytical reasoning, and nurture an innovative organizational culture, thereby driving both individual growth and overall organizational success [105]. |

| “Lack of coordination and poor internal communication between organization departments” (C18) | Inadequate organizational coordination and communication flow require a strategic focus on fostering collaboration and transparency. Encouraging cross-functional teams promotes a cooperative culture, allowing departments to work more cohesively toward innovative outcomes [106]. The range of expertise, alignment on shared objectives, strong long-term relationships, transparent communication, and ongoing opportunities for learning significantly enhance and promote collaboration within the government entity [107]. This facilitates the flow of information related to responsibilities, ensuring consistency and minimizing misunderstandings. |

| “Absence of clear and formalized innovation process” (C21) | Addressing this issue requires the implementation of structured and systematic frameworks that guide innovation activities. Developing a formal innovation process with defined goals, roles, and responsibilities ensures clarity and alignment [108]. Implementing standardized innovation systems has been proven to positively impact innovation performance [109]. Tools such as the Innovation Funnel [110] and Open Innovation Funnel [106,111] can systematically generate and evaluate ideas within the government entity and learn from external best practices. Regular training on innovation methodologies equips employees with the skills to participate effectively. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Institute of Knowledge Innovation and Invention. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abuzanjal, A.; Bashir, H. Assessing and Prioritizing Service Innovation Challenges in UAE Government Entities: A Network-Based Approach for Effective Decision-Making. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2025, 8, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/asi8040103

Abuzanjal A, Bashir H. Assessing and Prioritizing Service Innovation Challenges in UAE Government Entities: A Network-Based Approach for Effective Decision-Making. Applied System Innovation. 2025; 8(4):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/asi8040103

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbuzanjal, Abeer, and Hamdi Bashir. 2025. "Assessing and Prioritizing Service Innovation Challenges in UAE Government Entities: A Network-Based Approach for Effective Decision-Making" Applied System Innovation 8, no. 4: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/asi8040103

APA StyleAbuzanjal, A., & Bashir, H. (2025). Assessing and Prioritizing Service Innovation Challenges in UAE Government Entities: A Network-Based Approach for Effective Decision-Making. Applied System Innovation, 8(4), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/asi8040103