Developing a Decision-Making Framework to Improve Healthcare Service Quality during a Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What are the important criteria involved to enhance service quality in the ICU during this pandemic?

- What are the effective solutions that can be applied to improve the quality of service received by ICU patients during this pandemic?

- How can multiple stakeholders and their preferences be included in the decision-making process?

- i)

- It identifies a comprehensive list of factors for improving service quality in ICUs based on a detailed review of the relevant COVID-19-related literature.

- ii)

- It presents the development of a systematic decision-making framework that integrates the BWM, MAMCA, and MOLP methods.

- iii)

- The proposed framework can guide decision makers in situations where there are competing demands and enable them to select the best option for improving the quality of patient service within the context of COVID-19.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Decision-Making Methods Used

2.2. Research Related to ICU Service Quality Improvement

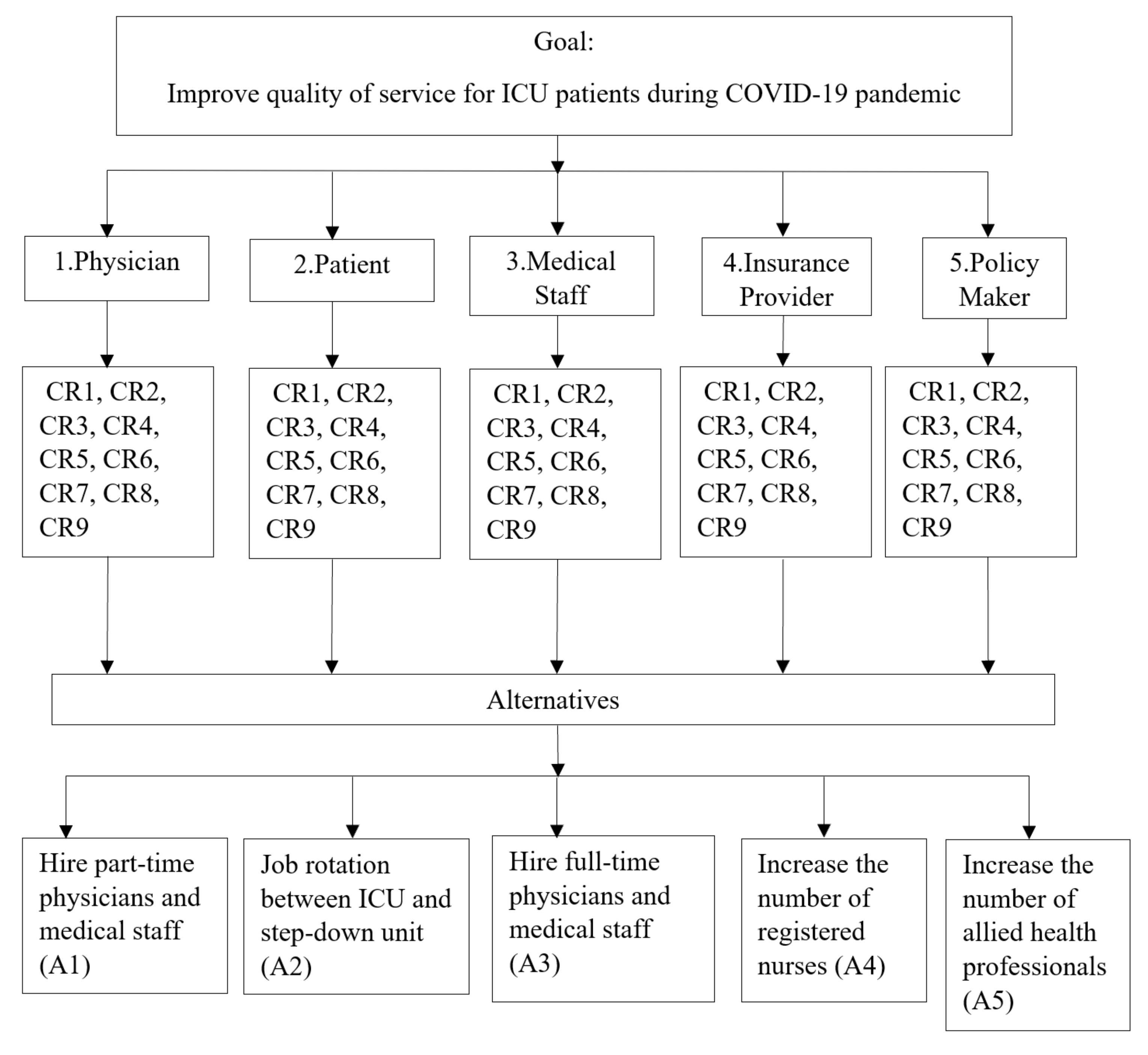

2.3. ICU Service Quality Improvement Criteria, Alternatives, and Stakeholders

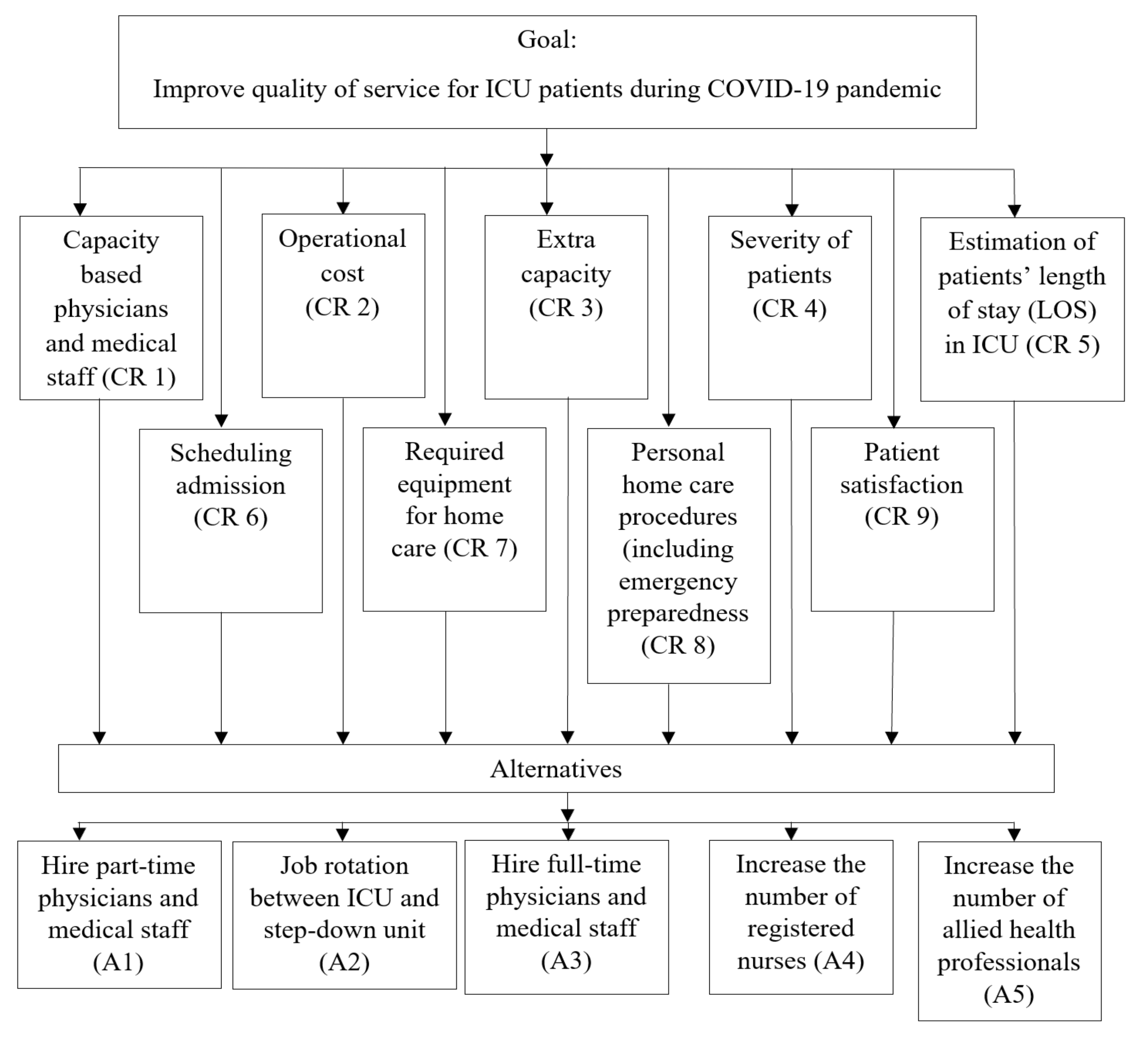

2.3.1. Criteria

2.3.2. Alternatives

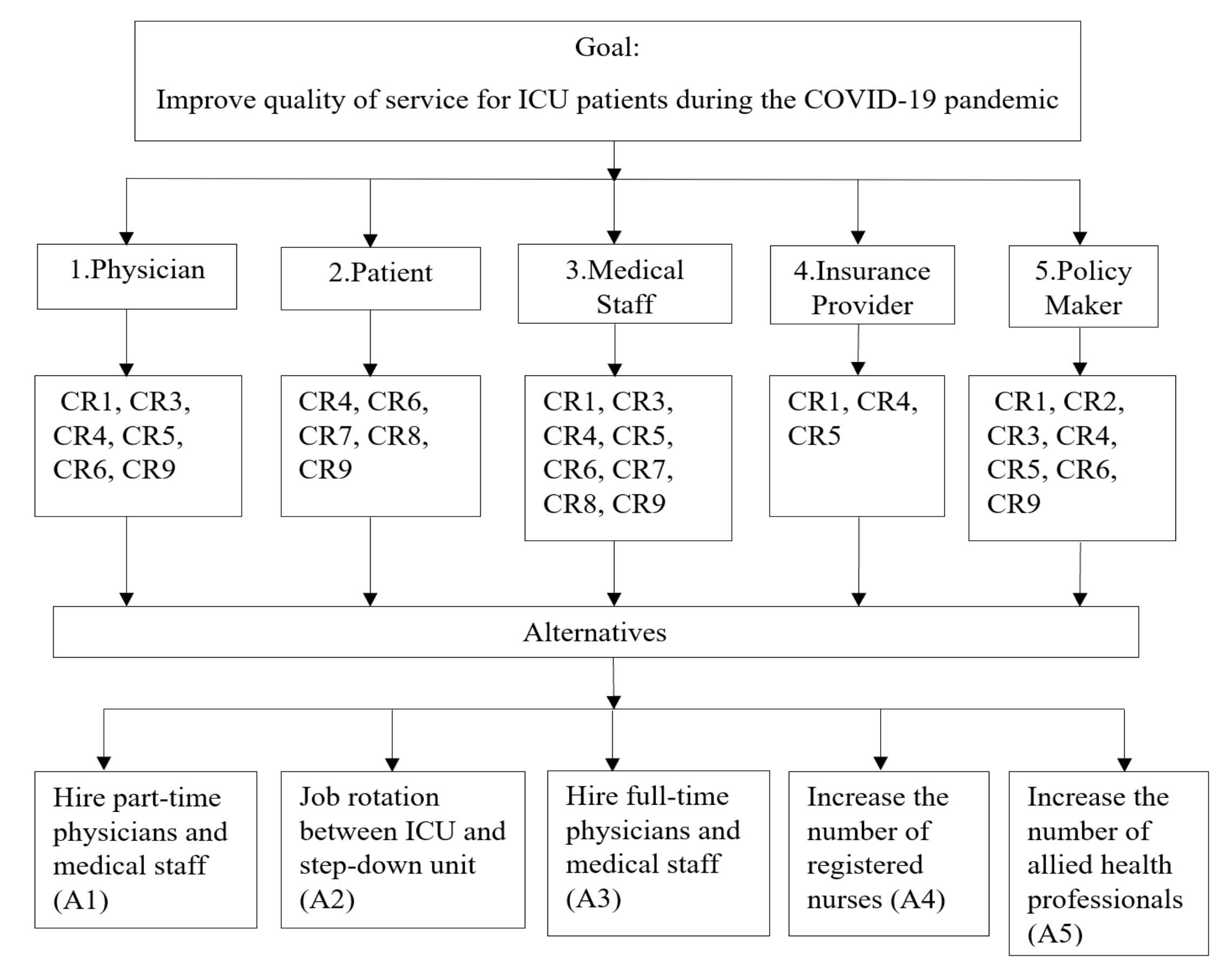

2.3.3. Identification of Stakeholders

- a)

- Internal Stakeholders: people who are responsible for tending to the organization’s everyday business. In a hospital context, internal stakeholders include physicians, nurses, management teams, and other professional staff.

- b)

- Interface Stakeholders: people who work between the hospital and the external environment. Fottler et al. [47] have argued that, compared to internal and external stakeholders, interface stakeholders are the major driving stakeholders in hospital management. This group includes some of the medical staff, corporate office, board of trustees, and others.

- c)

- External Stakeholders: can be broken down into three subcategories based on their relationship with the hospital sector. The first sub-category includes patients, medical suppliers, and others who provide input to the hospital. The second sub-category includes competitors (i.e., other hospitals) who focus on revenue and other experienced staff. The third sub-category consists of special interest groups who have a direct relation to hospital operations (i.e., policymakers, professional associations, labour unions, and others) [47].

3. Method

3.1. Best-Worst Method (BWM)

3.2. Multi-Actor Multi-Criteria Analysis (MAMCA)

3.3. Multi-Objective Linear Programming

4. Results

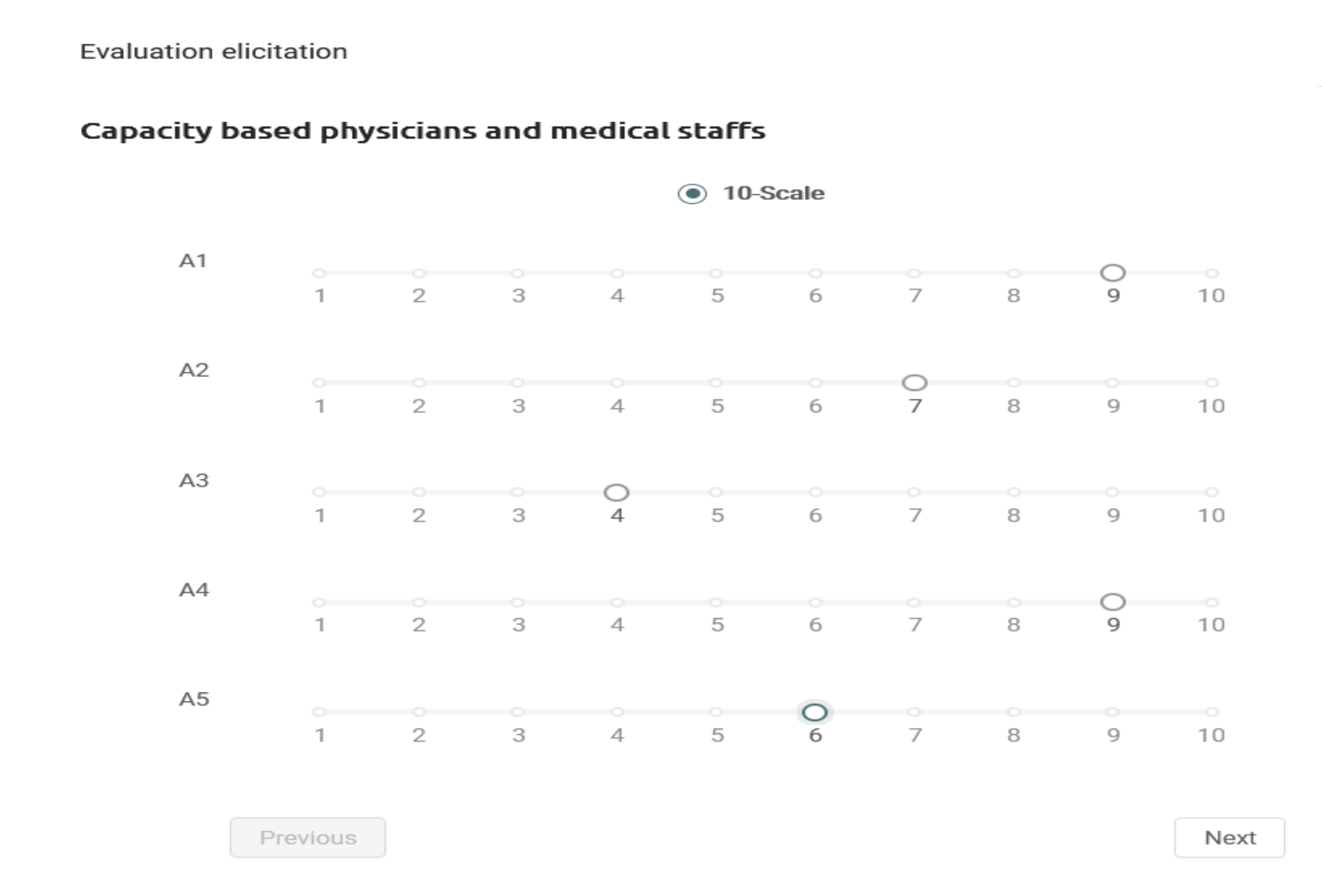

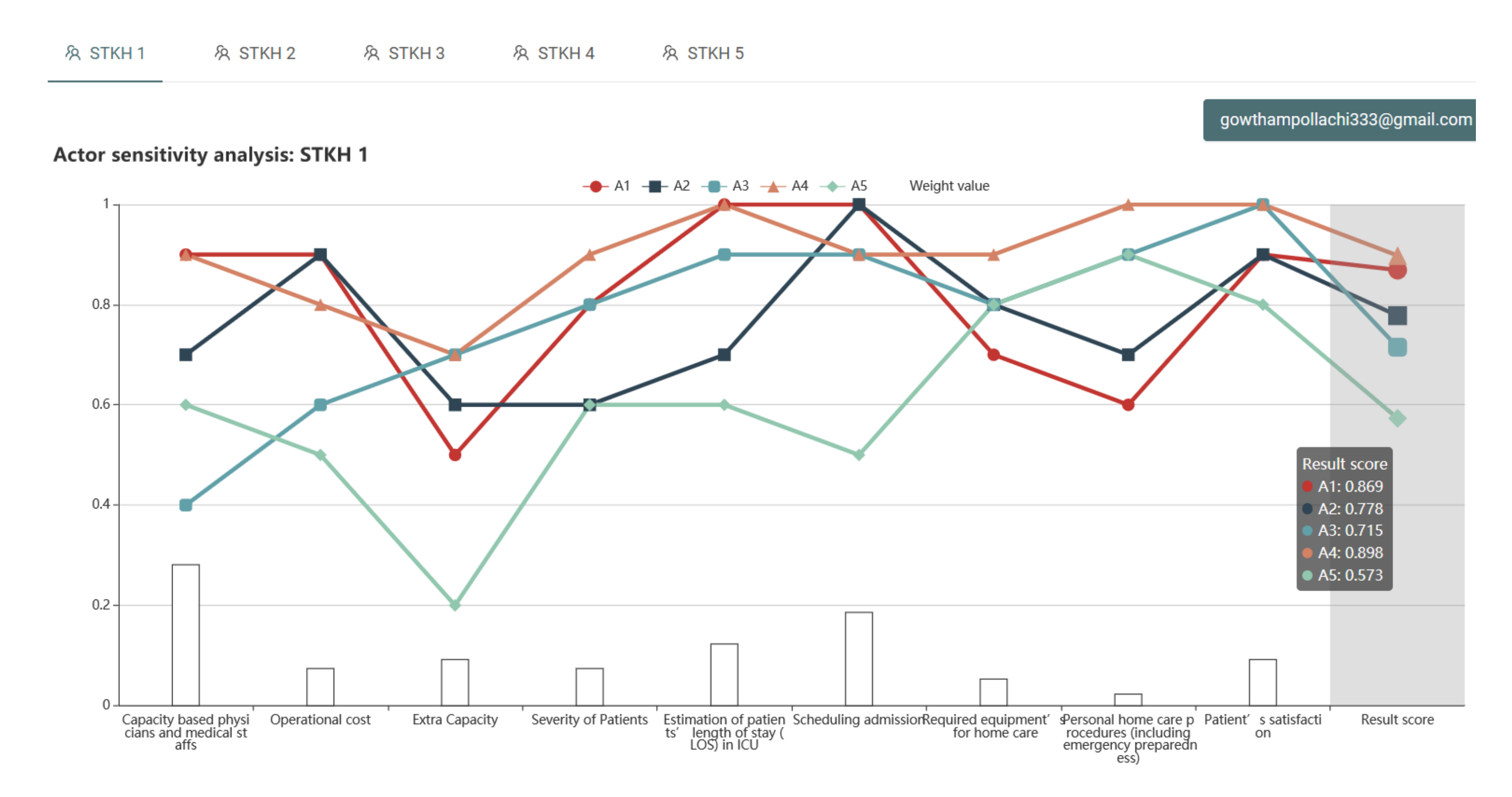

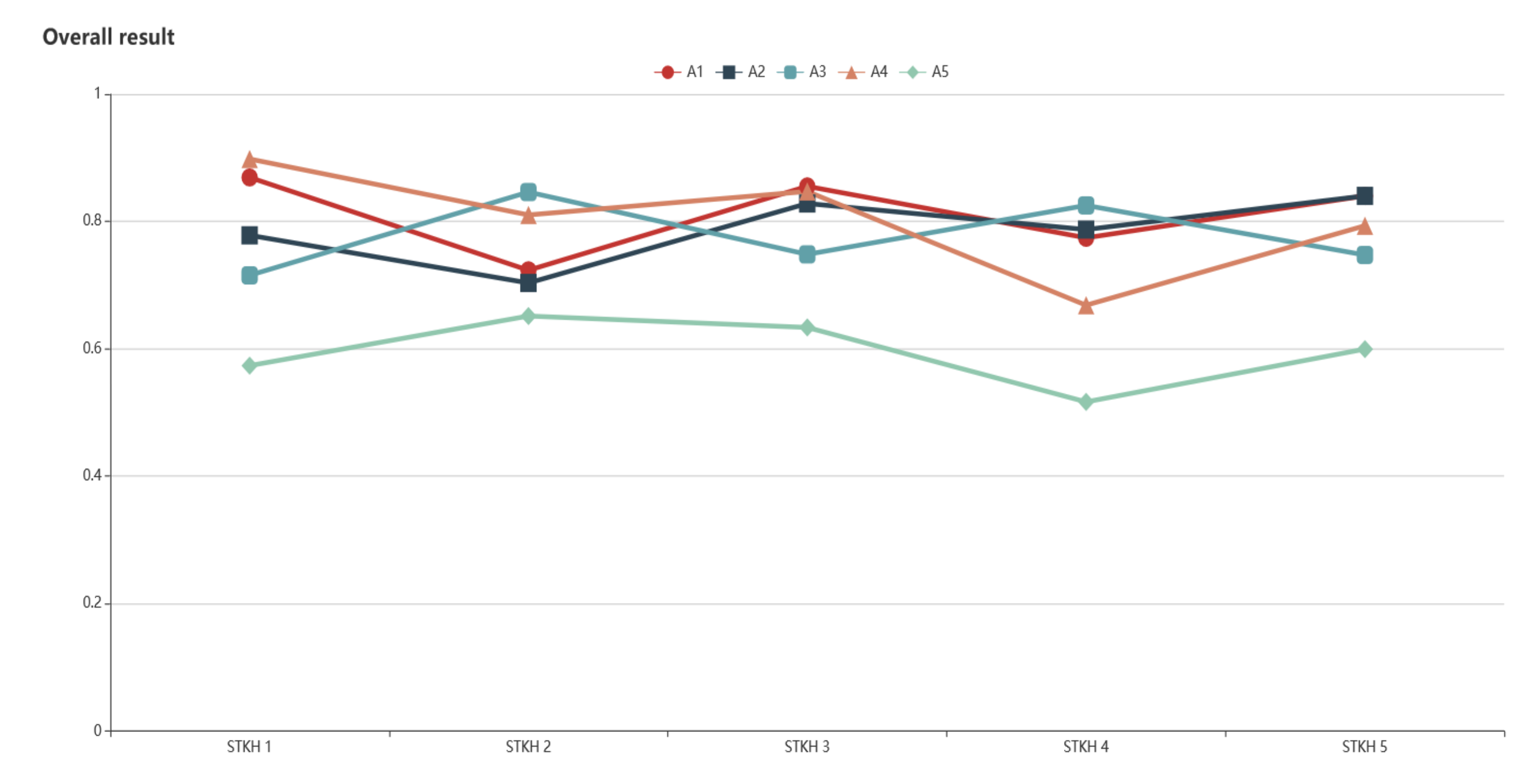

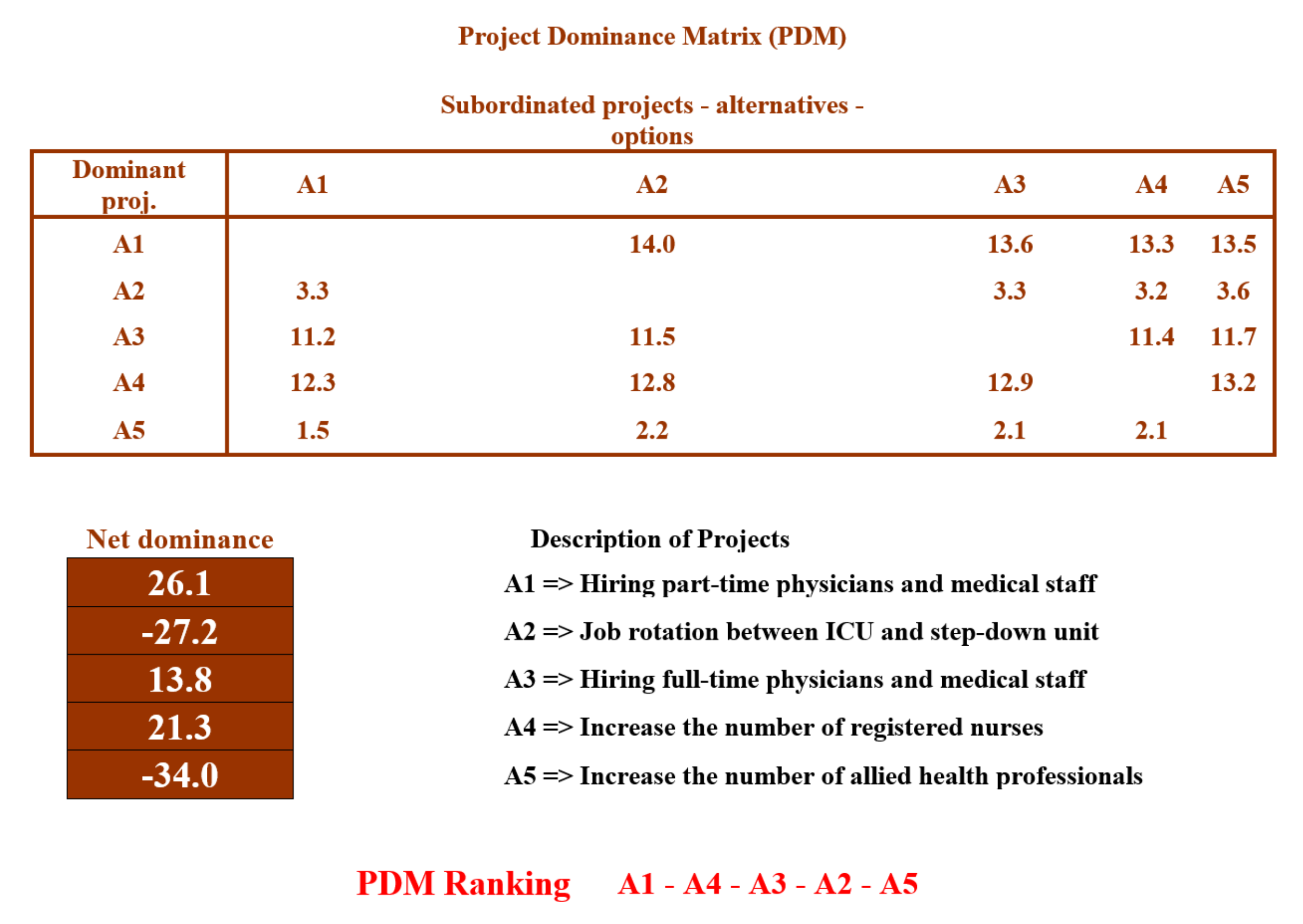

4.1. Scenario 1

4.2. Scenario 2

5. Discussion

Implications of This Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Best | CR 1 | CR 2 | CR 3 | CR 4 | CR 5 | CR 6 | CR 7 | CR 8 | CR 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STKH1 | CR 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 8 | 4 |

| STKH2 | CR 6 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| STKH3 | CR 1 | 1 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 5 |

| STKH4 | CR 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 3 |

| STKH5 | CR 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 5 |

| Others to Worst | STKH 1 (CR 8) | STKH (CR 2) | STKH (CR 2) | STKH (CR 7) | STKH (CR 8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR 1 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 8 |

| CR 2 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 9 |

| CR 3 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 |

| CR 4 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 7 |

| CR 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| CR 6 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 7 | 8 |

| CR 7 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 3 |

| CR 8 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 1 |

| CR 9 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 4 |

| STKH 1 | STKH 2 | STKH 3 | STKH 4 | STKH 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternatives | Alternative Weight | ||||

| A1 | 0.869 | 0.723 | 0.855 | 0.774 | 0.840 |

| A2 | 0.778 | 0.703 | 0.828 | 0.787 | 0.840 |

| A3 | 0.715 | 0.846 | 0.748 | 0.825 | 0.747 |

| A4 | 0.898 | 0.810 | 0.847 | 0.668 | 0.793 |

| A5 | 0.573 | 0.651 | 0.633 | 0.516 | 0.599 |

| Best | CR 1 | CR 2 | CR 3 | CR 4 | CR 5 | CR 6 | CR 7 | CR 8 | CR 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STKH 1 | CR 1 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | |||

| STKH 2 | CR 6 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 7 | ||||

| STKH 3 | CR 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 5 | |

| STKH 4 | CR 1 | 1 | 5 | 6 | ||||||

| STKH 5 | CR 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 5 |

| Others to Worst | STKH 1 (CR 3) | STKH 2 (CR 8) | STKH 3 (CR 3) | STKH 4 (CR 4) | STKH 5 (CR 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR 1 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 7 | |

| CR 2 | 8 | ||||

| CR 3 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| CR 4 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 7 |

| CR 5 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 1 | |

| CR 6 | 8 | 9 | 2 | 5 | |

| CR 7 | 5 | 6 | |||

| CR 8 | 1 | 7 | |||

| CR 9 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 |

References

- Adunlin, G.; Diaby, V.; Xiao, H. Application of multicriteria decision analysis in health care: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. Health Expect. 2015, 18, 1894–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Glaize, A.; Duenas, A.; Di Martinelly, C.; Fagnot, I. Healthcare decision-making applications using multicriteria decision analysis: A scoping review. J. Multi-Criteria Decis. Anal. 2019, 26, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alban, A.; Chick, S.E.; Dongelmans, D.A.; Vlaar AP, J.; Sent, D.; van der Sluijs, A.F.; Wiersinga, W.J. ICU capacity management during the COVID-19 pandemic using a process simulation. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 1624–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phua, J.; Weng, L.; Ling, L.; Egi, M.; Lim, C.M.; Divatia, J.V. Intensive care management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Challenges and recommendations. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.; Kaminsky, D.B. COVID-19′s Crushing Mental Health Toll on Health Care Workers. Cancer Cytopathol. 2020, 128, 597–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaukat, N.; Ali, D.M.; Razzak, J. Physical and mental health impacts of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: A scoping review. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 96, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altuntas, S.; Kansu, S. An innovative and integrated approach based on SERVQUAL, QFD and FMEA for service quality improvement: A case study. Kybernetes 2019, 49, 2419–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afkham, L.; Abdi, F.; Rashidi, A. Evaluation of service quality by using fuzzy MCDM: A case study in Iranian health-care centers. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2012, 2, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; De Smet, Y.; Macharis, C.; Doan, N.A.V. Collaborative decision-making in sustainable mobility: Identifying possible consensuses in the multi-actor multi-criteria analysis based on inverse mixed-integer linear optimization. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 28, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.T.; Lin, S.W.; Tzeng, G.H. Improving RFID adoption in Taiwan’s healthcare industry based on a DEMATEL technique with a hybrid MCDM model. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 56, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sałabun, W. The Characteristic Objects Method: A New Distance-based Approach to Multicriteria Decision-making Problems. J. Multi-Criteria Decis. Anal. 2015, 22, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamučar, D.; Ćirović, G. The selection of transport and handling resources in logistics centers using Multi-Attributive Border Approximation area Comparison (MABAC). Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 3016–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J. Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method. Omega 2015, 53, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezert, J.; Tchamova, A.; Han, D.; Tacnet, J.M. The SPOTIS rank reversal free method for multi-criteria decision-making support. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), Rustenburg, South Africa, 6–9 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kizielewicz, B.; Wątróbski, J.; Sałabun, W. Identification of relevant criteria set in the MCDA process—Wind farm location case study. Energies 2020, 13, 6548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Naim, I.; Ahmadi, H.B.; Oyedijo, A. A best-worst-method-based performance evaluation framework for manufacturing industry. Kybernetes 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fartaj, S.R.; Kabir, G.; Eghujovbo, V.; Ali, S.M.; Paul, S.K. Modeling transportation disruptions in the supply chain of automotive parts manufacturing company. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 222, 107511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moktadir, M.A.; Ali, S.M.; Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Shaikh, M.A.A. Assessing challenges for implementing Industry 4.0: Implications for process safety and environmental protection. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 117, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Brunelli, M.; Rezaei, J. Consistency issues in the best worst method: Measurements and thresholds. Omega 2020, 96, 102175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacHaris, C.; Turcksin, L.; Lebeau, K. Multi actor multi criteria analysis (MAMCA) as a tool to support sustainable decisions: State of use. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 54, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munier, N.; Hontoria, E.; Jiménez-Saez, F. Strategic Approach in Multi-Criteria Decision Making; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nigim, K.; Munier, N.; Green, J. Pre-feasibility MCDM tools to aid communities in prioritizing local viable renewable energy sources. Renew. Energy 2004, 29, 1775–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoilova, S.D. A multi-criteria selection of the transport plan of intercity passenger trains. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 664, 012031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimons, J. Quality and safety in the time of Coronavirus: Design better, learn faster. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2020, 33, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesterreich, S.; Cywinski, J.B.; Elo, B.; Geube, M.; Mathur, P. Quality improvement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2020, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaboyer, W.; Lin, F.; Foster, M.; Retallick, L.; Panuwatwanich, K.; Richards, B. Redesigning the ICU Nursing Discharge Process: A Quality Improvement Study. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2012, 9, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McWilliams, D.; Weblin, J.; Atkins, G.; Bion, J.; Williams, J.; Elliott, C.; Whitehouse, T.; Snelson, C. Enhancing rehabilitation of mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit: A quality improvement project. J. Crit. Care 2015, 30, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Needleman, J.; Buerhaus, P.; Mattke, S.; Stewart, M.; Zelevinsky, K. Nurse-staffing levels and the quality of care in hospitals. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 1715–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, J.S.; Rothschild, J.M.; Bendavid, E.; Sprivulis, P.; Cook, E.F.; Evans, R.S.; Kaganova, Y.; Bender, M.; David-Kasdan, J.; Haug, P.; et al. Hospital workload and adverse events. Med. Care 2007, 45, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, A.; Savin, S.; Savva, N. Physician workload and hospital reimbursement: Overworked physicians generate less revenue per patient. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2012, 14, 512–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weiss, A.J.; Elixhauser, A. Overview of Hospital Stays in the United States. 2014; pp. 1–14. Available online: http://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/st425/stat425.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2019).

- COVID-19 Pandemic Guidance for the Health Care Sector. 2020; Retrieved from Public Health Agency of Canada Website. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/health-professionals/covid-19-pandemic-guidance-health-care-sector.html (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Pérez, A.; Chan, W.; Dennis, R.J. Predicting the length of stay of patients admitted for intensive care using a first step analysis. Health Serv. Outcomes Res. Methodol. 2006, 6, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Krinsley, J.S.; Wasser, T.; Kang, G.; Bagshaw, S.M. Pre-admission functional status impacts the performance of the APACHE IV model of mortality prediction in critically ill patients. Crit. Care 2017, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wassef, M.; Trépanier, M.-O.; Mayrand, J.; Martine Habra, M.; Beauchamp, S. Effectiveness of discharge planning and transitional care interventions in reducing hospital readmissions for the elderly. In HTA Report; 2018. Available online: www.ciusss-ouestmtl.gouv.qc.ca (accessed on 2 August 2020).

- How To: Discharge Summaries—McMaster PA Student Resource. (n.d.) Available online: http://mcmasterpa.weebly.com/how-to-discharge-summaries.html (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Henrich, N.J.; Dodek, P.; Heyland, D.; Cook, D.; Rocker, G.; Kutsogiannis, D.; Ayas, N. Qualitative analysis of an intensive care unit family satisfaction survey. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 39, 1000–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Abri, R.; Al-Balushi, A. Patient satisfaction survey as a tool towards quality improvement. Oman Med. J. 2014, 29, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bin Traiki, T.A.; AlShammari, S.A.; AlAli, M.N.; Aljomah, N.A.; Alhassan, N.S.; Alkhayal, K.A.; Zubaidi, A.M. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patient satisfaction and surgical outcomes: A retrospective and cross sectional study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2020, 58, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kc, D.S.; Terwiesch, C. Impact of workload on service time and patient safety: An econometric analysis of hospital operations. Manag. Sci. 2009, 55, 1486–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Part-Time Doctors Defend Their Work: “It Doesn’t Make Us Any Less Valuable”|CBC Radio. 2020. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/radio/whitecoat/part-time-doctors-defend-their-work-it-doesn-t-make-us-any-less-valuable-1.5030656 (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Ho, W.H.; Chang, C.S.; Shih, Y.L.; Liang, R.D. Effects of job rotation and role stress among nurses on job satisfaction and organizational commitment. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2009, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gaba, D.M.; Howard, S.K. Fatigue among clinicians and the safety of patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 1249–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Haar, J.; Hoes, L.R.; Coles, C.E.; Seamon, K.; Fröhling, S.; Jäger, D.; Valenza, F.; De Braud, F.; De Petris, L.; Bergh, J.; et al. Caring for patients with cancer in the COVID-19 era. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kutney-Lee, A.; Sloane, D.M.; Aiken, L.H. An increase in the number of nurses with baccalaureate degrees is linked to lower rates of postsurgery mortality. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seeing an Allied Health Professional—Better Health Channel. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/servicesandsupport/seeing-an-allied-health-professional (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Fottler, M.D.; Blair, J.D.; Whitehead, C.J.; Laus, M.D.; Savage, G.T. Assessing key stakeholders: Who matters to hospitals and why? Hosp. Health Serv. Adm. 1989, 34, 525–546. [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar, G.; Almehdawe, E.; Kabir, G. Development of a Collaborative Decision-Making Framework to Improve the Patients’ Service Quality in the Intensive Care Unit. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Applications (DASA’20), Sakheer, Bahrain, 8–9 November 2020; pp. 597–600. [Google Scholar]

| Notation | Criteria | Explanation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CR1 | Physicians and medical staff capacity | Identifying an optimal number of physicians and staff is a critical task. Physicians and other medical staff need to be hired based on the unit’s capacity (i.e., number of beds). | [24,28,29] |

| CR2 | Operational cost | The cost incurred to run the facility, including the cost to operate the equipment, wages for staff, power sources, and other miscellaneous associated costs. | [30,31] |

| CR3 | Extra capacity | It is difficult for ICUs to accommodate all incoming patients during peak periods. The trauma department provides extra capacity where high-risk patients can be held until a bed becomes available in the ICU. | [4,25,30,32] |

| CR4 | Severity of patients | Severity is determined based on the patients’ medical complications and CTAS score. | [30,32] |

| CR5 | Estimation of patient length of stay | Patient length of stay is approximated based on the severity of their condition. | [32,33] |

| CR6 | Scheduling admission | Scheduling admission performed based on the severity of the patient is one of the key approaches to reduce congestion in the ICU. | [24,32,34] |

| CR7 | Required equipment for home care | Necessary medical equipment is required to treat patients safely in their homes. | [35] |

| CR8 | Personal home care procedures | Procedures to be followed after discharge, including emergency preparedness, drug consumption regimens, regular monitoring of body condition, and consulting appointments with physicians and others. | [32,33,36] |

| CR9 | Patient satisfaction | Feedback is an invaluable tool for improving treatment quality. Patients and their families are requested to provide feedback regarding the service that they received, as it provides an index of patient satisfaction. | [37,38,39] |

| Notation | Alternative | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | Hire part-time physicians and medical staff | [3,41] |

| A2 | Job rotation between ICU and step-down unit | [4,42] |

| A3 | Hire full-time physicians and medical staff | [43,44] |

| A4 | Increase the number of registered nurses | [24,45] |

| A5 | Increase the number of allied health professionals | [32,46] |

| Stakeholder | Best Criteria | Worst Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| STKH 1 | CR 1 | CR 8 |

| STKH 2 | CR 5 | CR 2 |

| STKH 3 | CR 1 | CR 2 |

| STKH 4 | CR 5 | CR 7 |

| STKH 5 | CR 2 | CR 8 |

| CR 1 | CR 2 | CR 3 | CR 4 | CR 5 | CR 6 | CR 7 | CR 8 | CR 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STKH1 | 0.280 | 0.074 | 0.092 | 0.074 | 0.123 | 0.185 | 0.053 | 0.023 | 0.092 |

| STKH2 | 0.140 | 0.032 | 0.070 | 0.084 | 0.308 | 0.140 | 0.070 | 0.070 | 0.084 |

| STKH3 | 0.267 | 0.021 | 0.067 | 0.101 | 0.134 | 0.202 | 0.067 | 0.057 | 0.080 |

| STKH4 | 0.143 | 0.143 | 0.095 | 0.143 | 0.223 | 0.095 | 0.022 | 0.035 | 0.095 |

| STKH5 | 0.115 | 0.268 | 0.086 | 0.086 | 0.173 | 0.115 | 0.057 | 0.023 | 0.069 |

| STKH 1 | STKH 2 | STKH 3 | STKH 4 | STKH 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternatives | Ranking of Alternatives | ||||

| A1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| A2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| A3 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| A4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| A5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Decision Makers | Best Criteria | Worst Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| STKH 1 | CR 1 | CR 3 |

| STKH 2 | CR 6 | CR 8 |

| STKH 3 | CR 1 | CR 3 |

| STKH 4 | CR 1 | CR 4 |

| STKH 5 | CR 2 | CR 5 |

| STKH 1 | STKH 2 | STKH 3 | STKH 4 | STKH 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternatives | Ranking of Alternatives | ||||

| A1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| A2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| A3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| A4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| A5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BWM–MAMCA | MOLP | BWM–MAMCA | MOLP | ||

| Stakeholder | Rank | Rank | Stakeholder | Rank | Rank |

| STKH 1 | A4 | A1 | STKH 1 | A1 | A1 |

| STKH 2 | A3 | A4 | STKH 2 | A3 | A3 |

| STKH 3 | A1 | A3 | STKH 3 | A1 | A4 |

| STKH 4 | A3 | A2 | STKH 4 | A4 | A5 |

| STKH 5 | A1 and A2 | A5 | STKH 5 | A1 | A2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sivakumar, G.; Almehdawe, E.; Kabir, G. Developing a Decision-Making Framework to Improve Healthcare Service Quality during a Pandemic. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2022, 5, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/asi5010003

Sivakumar G, Almehdawe E, Kabir G. Developing a Decision-Making Framework to Improve Healthcare Service Quality during a Pandemic. Applied System Innovation. 2022; 5(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/asi5010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleSivakumar, Gowthaman, Eman Almehdawe, and Golam Kabir. 2022. "Developing a Decision-Making Framework to Improve Healthcare Service Quality during a Pandemic" Applied System Innovation 5, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/asi5010003

APA StyleSivakumar, G., Almehdawe, E., & Kabir, G. (2022). Developing a Decision-Making Framework to Improve Healthcare Service Quality during a Pandemic. Applied System Innovation, 5(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/asi5010003