Abstract

The chronology of the Petralona hominid remains a key issue in European Middle Pleistocene paleoanthropology. The recent study by Falguères et al., which reports new U-series ages of approximately 300 ka for travertines associated with the Petralona cranium, provides an important opportunity to reassess this long-standing debate. This commentary critically evaluates the strengths and limitations of that contribution, with particular attention to the treatment of analytical precision, geological uncertainties, and stratigraphic constraints inherent to speleothem dating. While the new data represent a valuable analytical advance and independently support a Middle Pleistocene age, the reported narrow error margins warrant cautious interpretation. When broader sources of uncertainty are considered, the results are best viewed as a confirmation rather than a fundamental revision of the established chronological framework. Overall, this commentary situates the findings of the new study within their broader methodological and historical context and underscores their significance for refining, but not redefining, the age and evolutionary placement of the Petralona hominid.

1. Introduction

The chronological position of the Petralona hominid has long been a subject of scientific debate, involving a complex interplay of stratigraphic observations, paleoanthropological interpretations, and geochronological approaches. A recent study [1] triggered the present report. Earlier studies proposed age estimates ranging broadly within the Middle Pleistocene, often relying on indirect stratigraphic correlations, faunal assemblages, or early dating techniques with substantial uncertainties. These efforts established a general temporal framework but left unresolved questions regarding the precise relationship between the hominid-bearing layer and dated carbonate formations within the cave [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11].

In this context, the recent U-series dating study by [1] represents a significant attempt to refine the chronological framework of Petralona Cave by applying modern analytical techniques to travertine deposits. Their work has been presented as providing a more constrained numerical age for the hominid, potentially narrowing long-standing uncertainties. However, the implications of these new dates can only be properly assessed when considered within the broader stratigraphic, sedimentological, and geochemical context of the cave system.

The present study does not aim to dismiss the analytical precision of the U-series measurements reported by [1], but rather to critically evaluate the extent to which these measurements can be interpreted as providing a definitive age for the hominid fossil itself. To this end, we integrate previous stratigraphic observations, documented excavation records, and established methodological limitations of U-series dating in carbonate systems. By situating the new data within this broader evidential framework, we seek to distinguish between numerical dating results and their geological and archeological significance.

Accordingly, this paper proceeds by first reviewing the stratigraphic relationships relevant to the hominid-bearing deposits and the dated travertines, emphasizing points of uncertainty and discontinuity. It then examines the assumptions underlying closed-system behavior in the applied U-series models and evaluates the sensitivity of the proposed ages to potential uranium mobilization and detrital contamination. Through this structured approach, the study aims to provide a coherent reassessment of the chronological implications of the new dating results, rather than a mere juxtaposition of old and new data.

2. Methodological Advances and Cautions

The present manuscript maintains a deliberate focus on critically evaluating the contribution of [1] highlighting both its methodological strengths and its potential limitations. Their study represents a valuable advance through the application of high-precision MC-ICP-MS U–Th measurements and careful sample selection, providing an important independent confirmation of a Middle Pleistocene age for the Petralona cranium. At the same time, particular caution is warranted in the interpretation of the reported narrow error margins, which primarily reflect analytical reproducibility rather than the full spectrum of geological and stratigraphic uncertainties inherent to speleothem dating. Factors such as detrital thorium correction, possible open-system behavior, and stratigraphic consistency can substantially broaden the realistic uncertainty envelope. When these considerations are taken into account, the results of [1] are best viewed not as a definitive chronological refinement, but as a robust corroboration of an already well-established age range of approximately 250–300 ka for the Petralona hominid.

From the outset, we should emphasize that the reliability of U–Th determinations is compromised by detrital contamination and by open-system behavior of calcites. The paper in [1] introduced a procedure to better detect and correct for detrital thorium, improving confidence in results. At the time, these technical concerns were not widely integrated into hominid chronologies, leading to conflicting claims for the Petralona skull ranging from less than 100 ka to more than half a million years (including a luminescence age of burnt sediment of the cave [3].

The reliability of U-series ages obtained from carbonate deposits depends critically on the assumption of long-term closed-system behavior with respect to uranium and thorium isotopes. In the present case, the assessment of such behavior is limited by the absence of published petrographic observations, micro-geochemical characterization, or isotopic depth-profile data for the dated travertine samples. In particular, no 234U/238U activity ratio profiles, high-resolution μ-XRF imaging, or trace-element distribution data are provided that would allow evaluation of post-depositional uranium mobility or secondary alteration.

As has been widely documented in the literature, speleothems and travertines are susceptible to open-system processes, including uranium gain or loss during diagenesis, which can significantly bias apparent U-series ages even when analytical precision is high [12,13,14,15]. Without independent petrographic or geochemical evidence demonstrating isotopic equilibrium and structural integrity over geological timescales, closed-system behavior cannot be assumed a priori.

Accordingly, while the U-series measurements reported by [1] exhibit high analytical precision, the lack of supporting micro-analytical data introduces an additional source of uncertainty that is not fully captured by the reported error estimates. This distinction between analytical precision and geological reliability is well recognized in U–Th geochronology and underscores the need for cautious interpretation of numerical ages derived from carbonate deposits in complex cave environments [12] and corals [16].

In the 1984 review article [8], it was urged patience and critical evaluation: radiometric results must be scrutinized against stratigraphic integrity and geochemical behavior, not accepted uncritically. This “cautionary” stance was meant to prevent both premature minimization of the fossil’s antiquity and unwarranted inflation of its age (Figure 1). While these are important considerations, specific evidence below shows that the most precise reporting of the age affects the error margins of the new dates which are particularly helpful. The present short note questions the treatment of uncertainties by [1] and offers the explanation of why the most “robust” chronology should be 250–300 ka.

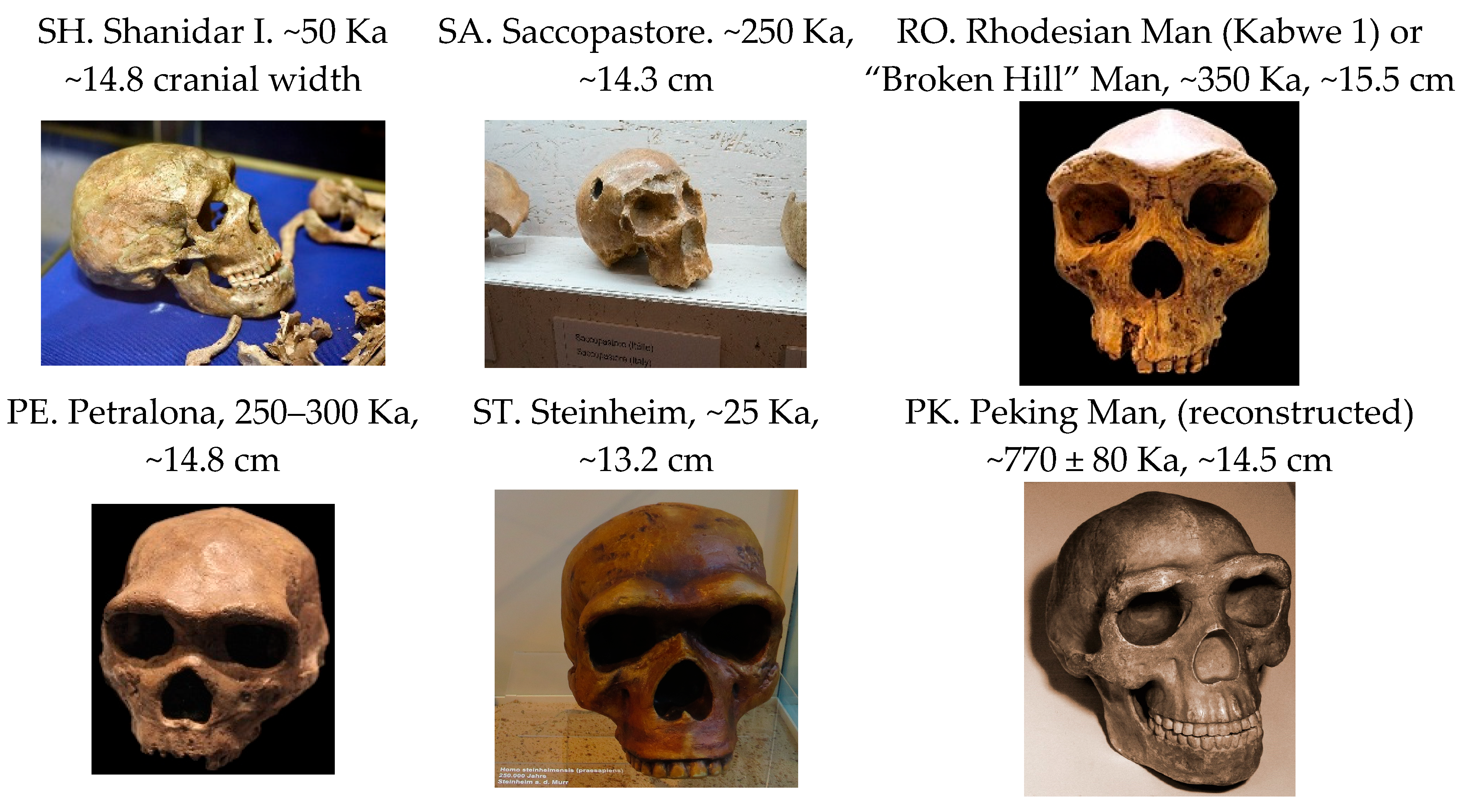

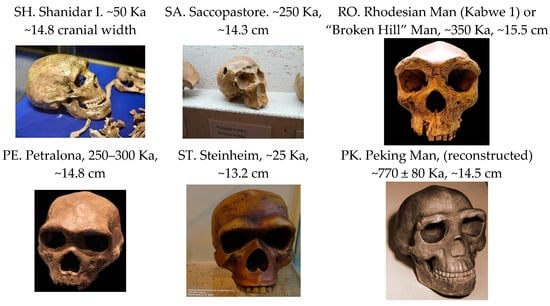

Figure 1.

Comparative placement of the Petralona cranium within the Middle Pleistocene European hominin record. The figure illustrates the morphological and chronological context of Petralona relative to selected Middle and Late Pleistocene hominins, emphasizing its probable age range of approximately 250–300 ka and its position within the broader evolutionary transition between Homo heidelbergensis and early Neanderthals. Scale concerns approx. cranial width (see Section 5, for details) (credit: Wikimedia) (see more on [17]).

3. Chronological Background

The age of the Petralona hominid has been the subject of sustained debate for more than four decades, reflecting both the methodological challenges of dating cave contexts and the diversity of materials sampled within the site. Chronological estimates have varied widely, ranging from less than 150 ka to more than 600–700 ka. This section reviews the principal dating studies undertaken at Petralona, organized by dating method, dated material, and reported age range, in order to reconstruct a coherent framework for understanding these discrepancies.

3.1. U–Th Dating of Travertines and Speleothems

Uranium–thorium (U–Th) disequilibrium dating has played a central role in the chronological discussion of Petralona. Early U–Th studies focused on travertines and speleothems associated with the Mausoleum chamber and adjacent stratigraphic units, including calcite layers overlying and surrounding the findspot of the cranium. These analyses produced a wide range of ages, reflecting varying degrees of detrital contamination and open-system behavior. While some samples yielded very old apparent ages exceeding 600 ka, these were generally associated with heavily contaminated travertines or complex growth histories and were interpreted cautiously even at the time (Figure 2). In the Petralona Cave stratigraphic scheme, the A1/A2 sections and the so-called “Mausoleum” refer to excavation areas, not independent stratigraphic levels. Their stratigraphic attribution depends on the layers exposed within those areas. A1 and A2 are excavation sectors located in the central part of the cave, close to where the skull was reportedly found. Stratigraphically, they mainly expose Middle Pleistocene deposits, corresponding to: Layers 10–11 (sensu Poulianos) or their equivalents in later correlations. These levels include: Cemented breccias, Flowstone-intercalated sediments, Faunal remains and lithics. The Mausoleum is a constructed feature/display area, not a natural stratigraphic unit. It was built after the skull’s removal, directly on top of Middle Pleistocene deposits. Therefore, it does not belong to any stratigraphic level in the geological sense. Stratigraphically, it overlies Layers 10–11–type deposits, but is historical/modern in age.

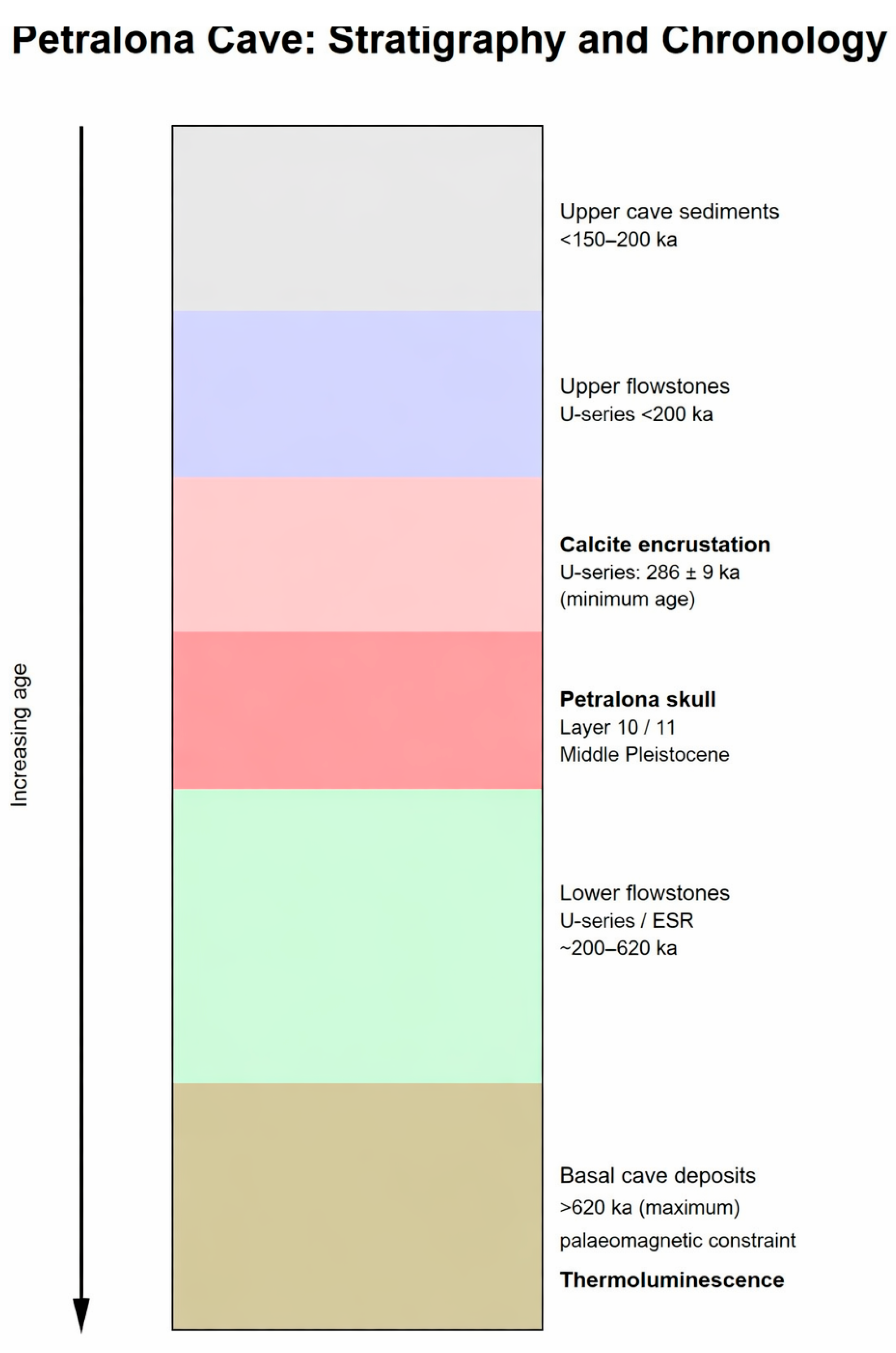

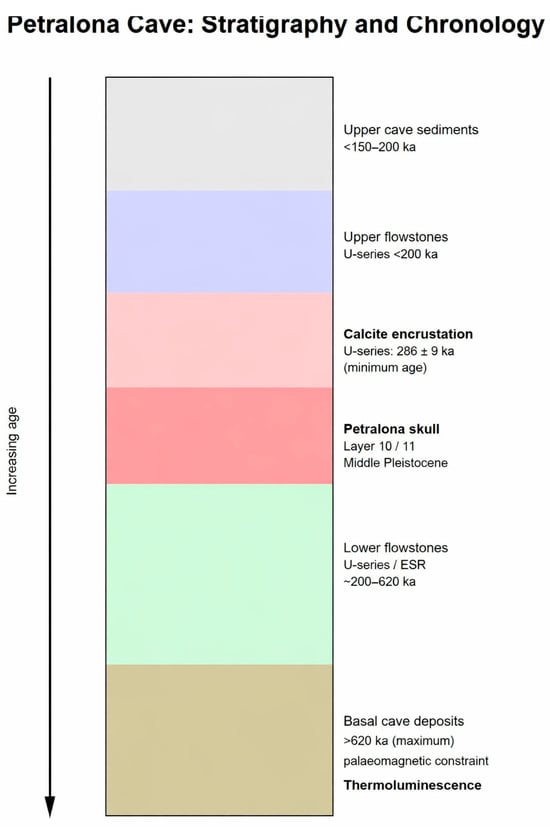

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the stratigraphic relationships within Petralona Cave, illustrating the relative positions of the hominid-bearing sedimentary deposits (Petralona skull) and the travertine formations dated by U-series methods (calcite encrustations) in [1]. The travertine horizons correspond to carbonate precipitations developed along cave walls and ceilings and are shown in stratigraphic association with, but not demonstrably sealing, the fossil-bearing layer. The figure emphasizes the spatial separation between the dated travertines and the hominid-bearing sediments, highlighting that the U-series ages constrain phases of speleothem formation within the cave rather than directly dating the depositional context of the hominid remains (© the author).

More consistent and stratigraphically coherent U–Th results were obtained from cleaner travertine layers sealing the hominid-bearing deposits. These studies converged on ages above ~230 ka, with most reliable estimates clustering between approximately 250 and 300 ka. Importantly, the dating of calcite layers stratigraphically overlying the skull demonstrated that the hominid could not be younger than these sealing deposits, thereby excluding Late Pleistocene ages. The recent MC-ICP-MS U–Th measurements reported by [1] fall within this same range, yielding a minimum age of ~286 ka, and thus broadly confirm the Middle Pleistocene placement indicated by earlier U–Th work, albeit with more precise analytical measurements.

3.2. ESR Dating of Tooth Enamel and Associated Materials

Electron spin resonance (ESR) dating has also been applied at Petralona, primarily to faunal tooth enamel recovered from cave sediments. ESR ages have generally produced intermediate to older Middle Pleistocene estimates, often overlapping with or slightly exceeding the U–Th travertine ages. Some ESR results suggested ages approaching or exceeding 400 ka, depending on assumptions about uranium uptake history. While these results contributed to arguments for an older chronology, their interpretation remains sensitive to model assumptions and the complex depositional history of the cave sediments [11].

3.3. Thermoluminescence and Luminescence Dating of Sediments

Thermoluminescence (TL) and related luminescence methods were applied to burnt sediments and cave deposits in attempts to directly date human activity within the cave. These studies yielded some of the youngest reported ages for Petralona, in the range of ~100–150 ka and much older ~700 ka where minerals satisfied dose growth criteria but some others may suffer from anomalous fading (3, 6, 9, 10). However, such results date the last heating or exposure of sediments rather than the age of the hominid fossil itself. As a result, these younger and older ages were increasingly interpreted as reflecting either later cave use or localized thermal events rather than the time of deposition of the skull. Consequently, luminescence ages do not provide a reliable constraint on the antiquity of the Petralona cranium and are best viewed as evidence for episodic Late Pleistocene activity within the cave.

3.4. Reconciling Older and Younger Age Estimates

The coexistence of very old (>600–700 ka) and much younger (~100–150 ka) age estimates is best explained by the complex stratigraphy and multi-phase depositional history of Petralona Cave. Extremely old U–Th ages are largely associated with contaminated or reworked carbonate deposits and cannot be directly linked to the hominid-bearing horizon. Conversely, younger luminescence ages reflect later sedimentary or thermal events unrelated to the emplacement of the skull. When attention is restricted to stratigraphically relevant, well-characterized travertines and speleothems sealing the findspot, a coherent chronological framework emerges (Figure 2).

The stratigraphic relationship between the dated travertine formations and the hominid-bearing deposits constitutes a critical element in assessing the chronological significance of the U-series results. As illustrated in the stratigraphic figures provided by [1], the travertine samples subjected to U-series dating are spatially associated with carbonate formations developed along the cave walls and ceilings, rather than being demonstrably interbedded with, or directly sealing, the sedimentary layer from which the hominid fossil was recovered.

In the published stratigraphic sections, the hominid-bearing deposits are shown to belong to a distinct sedimentary unit within the cave infill, whereas the dated travertines occur in positions that are stratigraphically adjacent but not unequivocally superposed upon the fossiliferous layer. This spatial arrangement implies that the U-series ages obtained from these travertines constrain the timing of carbonate precipitation events within the cave rather than directly dating the depositional context of the hominid remains themselves.

Consequently, while the dated travertines provide valuable chronological information regarding phases of speleothem formation, their stratigraphic position—as depicted in the figures of [1]—does not conclusively demonstrate a direct chronological linkage to the hominid-bearing sediments. The distinction between stratigraphic association and stratigraphic sealing is therefore essential. Without clear evidence that the dated travertines postdate and physically cap the fossil-bearing layer, the resulting ages should be interpreted as providing a terminus within the cave’s depositional history rather than a definitive numerical age for the hominid fossil.

Taken together, the most robust geochronological evidence consistently supports a minimum age of >230 ka and a most probable age range of approximately 250–300 ka for the Petralona hominid. In this context, the new results of [1] should be regarded as a methodological refinement and independent confirmation of this Middle Pleistocene chronology, rather than as a resolution that overturns earlier interpretations.

4. Interpretation of the Errors

In addition, three points should be cleared up regarding the new confirmation of the age of the skull:

(a) Earlier analyses have demonstrated a wide spread of ages, ranging from ~170 ka to ~700 ka. This variability, also restated by [1], underscores the difficulty of assigning a single consensus age to the Petralona hominid. Rather, these results reflect the episodic growth of speleothems formed at different times in association with various human and faunal remains within the cave.

(b) The analytical error reported from this method (e.g., ±0.5% at 2σ) reflects the precision of the isotope ratio measurement for that aliquot. The true age error must also include:

- o

- Detrital correction uncertainty.

- o

- Open-system uncertainties.

- o

- Stratigraphic consistency checks (layer order).

Therefore, a quoted error of ±9 ka (~3%) for a Middle Pleistocene sample (~286 ka) is likely too optimistic, because it ignores the compounded uncertainties beyond instrumental statistics.

In this context, it is important to evaluate the recent U–Th measurements of [1] who reported a minimum age of 286 ± 9 ka for the Petralona travertines. While their new dataset is valuable, the quoted error margin of only ~3% appears conspicuously precise. Such tight confidence limits reflect primarily the analytical reproducibility of isotope ratios (obtained by MC-ICP-MS), but they do not adequately account for the broader uncertainties that affect speleothem dating: detrital thorium correction, potential open-system behavior, initial 234U disequilibrium, and the heterogeneity of carbonate growth layers. As discussed in earlier methodological papers (e.g., [2,6,12,16], these factors can enlarge the true uncertainty beyond the narrow instrumental error bars, to some dozens of thousands of years. Therefore, while the central value of ~286 ka is broadly consistent with my earlier evaluations, the apparent precision of ±9 ka should be regarded cautiously. A more realistic treatment of uncertainties would recognize that single aliquot errors cannot capture the full variability of the system, and that overall age ranges (≥230 ka, most likely 250–300 ka) remain the most robust way to frame the antiquity of the Petralona hominid [6,7]. For a ~286 ka sample like the Petralona travertine, a more realistic total uncertainty that incorporates just the initial 234U and detrital Th corrections would likely be in the range of ±20–30 ka as calculated and critically discussed by earlier publications [2,4,5,7,8,10]. This corresponds to a relative uncertainty of ~7–10%, not the reported ~3%. Therefore, a more cautiously reported age would be 286 ± 20 ka or even 286 ± 30 ka. Let us assume a sample with an uncorrected age of ~300 ka. Table 1 shows how the corrected age and its uncertainty change with different levels of detrital contamination. In earlier calculated ratios they range from 3 to 4, 13 to 15 and up to 50 (Table 1 in [6]), i.e., high to clean/moderate. There the corrected ages were calculated by applying the novel correction method which assumes the thorium and uranium to be leached from the detritus in proportion to their content in the detritus and avoids the assumption of secular equilibrium. Such information on the thorium and uranium content of the detrital component of the travertine was sought by analysis of the nitric acid insoluble residue from the dissolution of the calcium carbonate. In particular, samples P-4-1 and P-12 top, both came from the top layer of travertine at positions separated by about 5 m. Their uncorrected ages are quite different while their corrected ages agree as might be expected for the same layer of travertine deposit, due to the new correction method (see, relevant equations and Table 1 in [6]).

Table 1.

Impact on age from practical scenarios of 230Th/232Th ratios for a ~300 ka sample.

5. Discussion and Implications for the Evolutionary Stage of the Petralona Hominid

The comparative framework illustrated in Figure 1 draws on a selection of well-documented Pleistocene hominin crania in order to contextualize the Petralona specimen both chronologically and morphologically. Middle Pleistocene fossils such as Steinheim and Saccopastore, generally dated to Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 7, provide close analogs in terms of cranial robusticity and intermediate morphology, reflecting populations often attributed to Homo heidelbergensis or early Neanderthals. Kabwe (Broken Hill), with an estimated age approaching ~300 ka, similarly exhibits a mosaic of archaic and derived traits, underscoring the variability characteristic of this evolutionary phase. In contrast, later specimens such as Shanidar I, securely dated to the Late Pleistocene (MIS 3), display fully developed Neanderthal morphology and serve as a temporal and anatomical endpoint against which earlier forms can be evaluated. More archaic Asian material, exemplified by Zhoukoudian (Homo erectus), highlights the deeper evolutionary roots of Middle Pleistocene populations but also emphasizes the distinct evolutionary trajectories in Europe and East Asia. Viewed within this continuum, the Petralona cranium—characterized by a combination of primitive and derived features—fits most coherently within a Middle Pleistocene timeframe of approximately 250–300 ka. This comparative perspective reinforces the importance of integrating morphology with robust geochronological evidence and supports the interpretation of Petralona as part of a transitional population preceding the emergence of classic Neanderthals. (see more comparisons in [17]).

5.1. Plausibility and Significance of the New U-Series Results

The new U-series ages reported by [1] represent a valuable analytical contribution to the long-standing chronological debate surrounding the Petralona hominid. Their minimum age estimate of approximately 286 ka does not contradict, but rather falls squarely within, the previously supported age range of about 250–300 ka. In this sense, the new results provide an independent confirmation of a Middle Pleistocene chronology rather than departure from earlier interpretations.

It is important to acknowledge the technical advances underlying this study. The application of high-precision MC-ICP-MS instrumentation, combined with careful minute sampling strategies, reflects the current state of the art in U-series geochronology and offers improved analytical reproducibility compared with earlier measurements. These methodological improvements enhance confidence in the measured isotope ratios themselves and strengthen the value of the new dataset as a benchmark for future work at Petralona and comparable cave sites.

5.2. Analytical Precision Versus Total Chronological Uncertainty

Despite these advances, a clear distinction must be made between analytical precision and total chronological uncertainty. The reported uncertainty of ±9 ka (approximately 3%) primarily reflects the reproducibility of isotope ratio measurements under controlled laboratory conditions. While such precision is technically impressive, it does not capture the full uncertainty budget associated with U-series dating of cave carbonates.

Total age uncertainty must also account for geological and geochemical factors that are not reflected in instrumental statistics alone. These include uncertainties related to detrital thorium correction, assumptions regarding initial uranium isotopic composition, stratigraphic integrity, and the long-term geochemical behavior of the dated material. When these factors are considered, the effective uncertainty of Middle Pleistocene speleothem ages commonly exceeds the narrow analytical error margins reported for individual aliquots.

5.3. Uranium Mobility and Open-System Behavior in Cave Carbonates

A fundamental limitation of U-series geochronology in cave environments is the potential mobility of uranium within carbonate systems. Speleothems and travertines may experience post-depositional uranium gain or loss due to groundwater circulation, changing redox conditions, or micro-fracturing, even when samples appear macroscopically well preserved. Such processes can alter apparent ages without leaving obvious petrographic evidence.

In this context, it is appropriate to ask whether closed-system behavior has been conclusively demonstrated for the dated samples. Although sampling from the “innermost layers” of carbonate deposits reduces the likelihood of later alteration, it does not necessarily exclude all subsequent water–rock interactions over timescales of several hundred thousand years. Demonstrating long-term closed-system behavior remains one of the most challenging aspects of U-series dating in caves and warrants explicit consideration when interpreting highly precise age estimates.

5.4. Additional Factors Affecting Dating Reliability

Beyond uranium mobility, several additional factors may influence the reliability of U-series ages and their associated uncertainties. Intra-sample isotopic heterogeneity can arise from complex growth histories or variable detrital incorporation within a single carbonate layer. Radiation damage accumulated over long timescales may subtly affect uranium distribution, while differences in analytical approach and correction models can lead to systematically different age estimates.

Groundwater chemistry and broader environmental dynamics within the cave, including episodic flooding, shifts in hydrology, and changes in sedimentation patterns, further complicate the long-term geochemical stability of carbonate deposits. These processes underscore the difficulty of assigning very narrow error margins to Middle Pleistocene cave samples and highlight the importance of integrating multiple lines of evidence rather than relying on analytical precision alone.

5.5. Implications for the Chronology of the Petralona Hominid

When these considerations are taken into account, the results of [1] are best interpreted as a robust corroboration of an already well-established chronological framework. Their reported age of ~286 ka aligns closely with earlier U-series, ESR, and stratigraphic evidence indicating a minimum age greater than 230 ka and a most probable range of 250–300 ka for the Petralona cranium [2,3,4,5,6,7,10,11].

Accordingly, the principal contribution of the new study lies not in redefining the age of the fossil, but in confirming its Middle Pleistocene placement using modern analytical tools. A cautiously framed age range that reflects both analytical precision and geological uncertainty remains the most scientifically defensible approach. Within such a framework, the Petralona hominid continues to occupy a key position in discussions of European human evolution during the critical transition from Homo heidelbergensis to early Neanderthals.

An age of ~250–300 ka securely situates the Petralona hominid within the Middle Pleistocene, a critical phase in European human evolution. This time span corresponds to the later part of the Homo heidelbergensis or “archaic Homo sapiens” stage, preceding but approaching the emergence of classic Neanderthal morphology in Europe. Petralona therefore represents a valuable member of the European Middle Pleistocene hominin record, comparable in antiquity to fossils such as Steinheim, and Swanscombe and others (see Figure 1).

This placement has broader significance:

- It supports the view that Europe in the mid-Pleistocene was inhabited by transitional populations between early H. heidelbergensis and later Neanderthals.

- It highlights the evolutionary depth of hominid occupation in southeastern Europe, adding to the geographic diversity of Middle Pleistocene humans.

- It shows that geochronology, when carefully applied with attention to geochemical pitfalls, can resolve controversies that have persisted for decades.

6. Conclusions

Our synthesis indicates that the Petralona fossil most likely dates to >230 ka, with the most credible range between 250 and 300 ka. The ~286 ka result reported by [1] provides an independent confirmation of this established chronological framework rather than representing a disruptive new finding. This reinforces the reliability of previous U–Th and related dating studies while contextualizing the Petralona remains within the Middle Pleistocene.

We further emphasize the need for the academic community to clearly distinguish between analytical precision and true geological uncertainty when applying high-precision MC-ICP-MS U–Th dating. Recognizing this distinction is essential for enhancing cross-laboratory comparability and reproducibility, ensuring that reported ages reflect both instrumental capability and natural variability. Adopting consistent practices in uncertainty reporting will strengthen the robustness of Middle Pleistocene chronologies and support more reliable interpretations of human evolution and paleoenvironmental reconstructions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

Not applicable.

Author’s Note

This review was prepared with the assistance of AI language models (ChatGPT 5.2/DeepSeek) for proofreading and language polishing. The ideas, calculations, original writing, interpretations and opinions expressed are my own.

References

- Falguères, C.; Shao, Q.; Perrenoud, C.; Stringer, C.; Tombret, O.; Garbé, L.; Darlas, A. New U-series dates on the Petralona cranium, a key fossil in European human evolution. J. Hum. Evol. 2025, 206, 103732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liritzis, Y. Some 230Th/234U dates on detrital travertines from Petralona Cave, Greece. Rev. D’archéométrie 1980, 4, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liritzis, Y. Potential use of thermoluminescence in dating speleothems. Anthropos 1980, 7, 242–251. [Google Scholar]

- Liritzis, Y. 230Th/234U dating of speleothems in Petralona. Anthropos 1980, 7, 215–241. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarcz, H.P.; Liritzis, Y.; Dixon, A. Absolute dating of travertines from Petralona Cave. Anthropos 1980, 7, 152–173. [Google Scholar]

- Liritzis, Y.; Galloway, R.B. The 230Th/234U disequilibrium dating of cave travertines. Nucl. Instrum. Methods 1982, 201, 507–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liritzis, Y. 234U/230Th dating contribution to the resolution of the Petralona controversy. Nature 1983, 299, 280–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liritzis, Y. A critical dating revaluation of the Petralona hominid: A caution for patience. Athens Ann. Archaeol. 1984, XV, 285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Bangert, U.; Hennig, G.J. Effects of sample preparation and the influence of clay impurities on the TL-dating of calcitic cave deposits. PACT 1979, 3, 281–289. [Google Scholar]

- Hennig, G.J.; Bangert, U.; Herr, W.; Poulianos, A.N. Uranium-series dating and TL ages of speleothems from Petralona Cave. Anthropos 1980, 7, 174–214. [Google Scholar]

- Hennig, G.; Herr, W.; Weber, E.; Xirotiris, N.I. ESR-dating of the fossil hominid cranium from Petralona Cave, Greece. Nature 1981, 292, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorale, J.A.; Edwards, R.L.; Alexander, C.A., Jr.; Shen, C.-C.; Richards, D.A.; Cheng, H. Uranium-series dating of speleothemes: Current techniques, limits & applications. In Studies of Cave Sediments: Physical and Chemical Records of Paleoclimate; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, D.; Hoffmann, D.L. StalAge—An algorithm designed for construction of speleothem age models. Quat. Geochronol. 2011, 6, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Edwards, R.L.; Shen, C.-C.; Polyak, V.J.; Asmerom, Y.; Woodhead, J.; Hellstrom, J.; Wang, Y.; Kong, X.; Spötl, C.; et al. Improvements in 230Th dating, 230Th and 234U half-life values, and U–Th isotopic measurements by multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2013, 371–372, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellstrom, J. Rapid and accurate U–Th dating using parallel ion-counting MC-ICP-MS. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2003, 18, 1346–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, D.; Hoffmann, D.L. 230Th/U-dating of fossil corals and speleothems. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2011, 30, 3088–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brace, C.L.; Nelson, H. Atlas of Fossil Man; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.