Abstract

The acquisition of large prey by hominins living during the Marine Isotope Stage 3, including Neanderthals and Anatomically Modern Humans, had nutritional and bioenergetic implications: these contain high fat amounts, provide a high energy return, and the strategies and skills required to acquire small prey were different from those required to acquire the former. Vitamin C availability at several MIS 3 periods could have had a strong seasonal variability and would have been decisive for hominin groups’ survival. During the cold periods of the MIS 3, Paleolithic hominins had variable available amounts of vitamin C-containing plants only in the short summers, and for the remainder of the year, viscera would have been their best source of vitamin C. Meanwhile, the dependence on small mammals could have caused an erratic distribution of viscera to be consumed by such hominins, thus leading to chronic scurvy, and compromising their survival. Then, the hunting of large mammals would have helped to meet the daily vitamin C needs, besides an efficient energy supply. Therefore, the decline of large prey during the MIS 3 could have been critical for hominins survival, and thus the efficient exploitation of alternative vitamin C-rich food resources such as birds and aquatic animals could have favored the evolutionary success of hominin populations.

1. Introduction

Hominins living during the Marine Isotope Stage 3 (M3H, ~60–20 ka) were Anatomically Modern Humans (AMH), Denisovans, and Neanderthals. The latter inhabited Western Eurasia from approximately ~430 ka [1], and their demise took place after Anatomically Modern Humans’ (AMH) dispersal, at ~42 ka [2,3]. Different hypotheses have been formulated for this event: abrupt climate and vegetation change [4,5], competitive exclusion [6], pathogens [7], assimilation [8,9], demographic weakness [10], and volcanic eruptions [11]. The proposed mechanisms are not mutually exclusive, and their relative roles may have also varied regionally and temporally [12]. Mitochondrial DNA nucleotide sequence differences among Neanderthals suggest three different geographical populations occurring in Western Europe, Southern Europe, and West Asia [13], while the earliest AMH in Europe are thought to have appeared around ~46 ka, and thus were directly contemporary with the latest European Neanderthals [14].

The demise of Neanderthals could have been linked to the paleoecology of other mammals. The biogeographical analysis of a database of European mammalian fossils for MIS 3 revealed the ecological conditions of this period, in which Neanderthals appear to belong to the extinct southern grouping of Late Pleistocene Megafaunal elements [15]. The geographical distribution of large mammals (>500 kg, corresponding to Bunn’s criteria [16], levels 4–) at MIS 3 confirms a retreat toward the south and west of Neanderthals [15], although it has been proposed that some millennia before their demise, about 59–49 ka, Neanderthals entered southern Siberia [17].

1.1. Controversy in the Diet of M3H

Northern European M3H had to face a medium with a great shortage of edible plants, with seasonal intensity, so they relied mainly on foods of animal origin for most of the year. For instance, Neanderthals seem to have had a predilection for large- and mega-faunal elements, and the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius Blumenbach, 1799) was the more prominent animal belonging to the Megafaunal complex. Its extinction is largely attributed to the worldwide wave of extinction of megafauna, which took place prior to the Holocene [18].

Both lithic and faunal assemblages and stable isotope analysis provide a measure of human diets in the past and support the idea that M3H subsistence was based mainly on the consumption of large herbivores [19,20,21,22]. Stable isotope analysis of human skeletons has been used successfully for years to determine the type of food animals consumed by M3H. For instance, the use of Ca isotopes allowed the dietary reconstruction of an OIS 5 Neandertal fossil from Southwest France, pointing out a predominantly carnivorous diet, composed of a mixture of various herbivorous prey [23]. The diet of Neanderthals was also assessed by the strontium–calcium (Sr/Ca) and barium–calcium (Ba/Ca) ratios of bones, which predicted that such a diet was composed of about 97% of meat with a weak contribution of vegetables or fish [24]. Recently, the evaluation of C and N stable isotope ratios in bone collagen allowed the assessment of the Paleolithic diet of Siberia and Eastern European hominins, and it was found that the Neanderthal diet in Siberia was based on the consumption of terrestrial animal protein, while for a Neanderthal/Denisovan hybrid the contribution of aquatic food like freshwater fish was suggested [25]. Overall, Paleolithic AMH in Siberia and Eastern Europe procured mainly terrestrial herbivores, such as reindeer, horses, and bison. Moreover, there is evidence that the oldest AMH individuals supplemented their diet with a certain amount of aquatic food [25]. In this context, isotopic analyses suggest that mammoths and plants were important contributors to the diets of the oldest AMH from far Southeast Europe [26], and that both Neanderthals and AMH relied on the same terrestrial herbivores, whereas mobility strategies indicate considerable differences between Neandertal groups, as well as in comparison to AMH, who exploited their environment to a greater extent than Neanderthals [27].

The use of plants as foods by Neanderthals, whether it was seasonal or occasional, has been documented [28,29]. Such use was inferred from the analyses of dental calculus, which has led to the argument that Neanderthals ate as many plants and used as many species of plants as modern humans do [30]. However, it is likely that a combination of mobility, energetics, and fatty acids requirements prevented high plant use by Neanderthals [31]. It must be taken into account that the consumption of herbivores’ stomach contents, which contain high amounts of carbohydrates, should be considered as a possible source of plant foods, including “medicinal” ones, in the archeological and fossil records [32]. Furthermore, the possible cooking of plant foods by Neanderthals is a hot topic, which currently promotes much debate among researchers.

Another means of reconstructing the diet and behavior of Neanderthals is dental macrowear analysis. Based on comparisons with modern hunter–gatherer populations, Neanderthals shows high dietary variability in Mediterranean evergreen habitats but a more restricted diet in upper latitude steppe/coniferous forest environments, suggesting a significant consumption of high-protein meat resources in this environment [33,34].

Overall, all the evidence points to the fact that Neanderthals were adapted to an essentially carnivorous diet, which was more marked for Northern European populations. This fact is supported by some morphological features of Neanderthals, such as their large lower thorax, which may represent an adaptation to a high-protein diet [35]. In addition to terrestrial mammals, various studies prove the use of birds and fish by Neanderthals, especially in the northwestern Mediterranean [36,37,38,39,40], but in all cases the most appreciated part of the prey by hunter–gatherers, given their high-protein diet with little access to carbohydrates, would always have been the fat [41,42].

Coexistence and hybridization between AMH and Neanderthals are known to have taken place in the Near and Middle East [43]. Therefore, it is more than likely that in some areas of the Neanderthal range, the coexistence of AMH and Neanderthals led to a reduction in their resource pool, and the technologies and cognitive abilities of the former allowed them to access a wider range of resources [44].

All these facts suggest a complex food scenario at the time of the replacement of Neanderthals by AMH. Another factor of uncertainty regarding food use in this period derives from the fact that assemblages checked from the most careful excavations are likely to have been affected by the mixing of materials during their very long curatorial histories [45]; therefore, some fossil finds may be biased and lead to inferences regarding M3H’s use of food.

1.2. Prevalence of Scurvy in M3H Populations

Ascorbic acid, or vitamin C (Vit C), has antioxidant functions as a free radical scavenger and allows the synthesis of collagen [46,47]. Today, there is ample consensus that scurvy can be prevented with a Vit C intake of 10 mg/day [48,49]. Scurvy shows a great variety of symptoms, such as arthralgias, bruising, or joint swelling, and common signs include pedal edema, bruising, mucosal changes, general fatigue, and myalgias [50]. Scurvy for M3H could have been more frequent than supposed. The most important diagnostic features are related to changes in soft tissues. Since these features are often difficult to diagnose in bone, obtaining archeological evidence for this condition is likely to be problematic [51]. Scurvy occurred in earlier human populations, and the subperiosteal lesions associated with scurvy assist in the differential diagnosis [52]. Scurvy’s cranial symptoms consist of porous and hypertrophic lesions of the vault, affecting frontal and parietal bosses, and related signs have been discovered in Paleolithic hominins’ bones. However, most cases of scurvy could have gone unnoticed, given that it is very difficult to attribute some doubtful pathological cases to scurvy since lesions of porotic hyperostosis are also linked to some type of anemia, infections, and/or poor nutrition [53]. In any case, pathologies related to scurvy have been unequivocally identified in some M3H skeletal remains, and some cases can be attributed to omnivorous populations, whether climatic features are considered. So, scurvy probably occurred in long winters, during which Vit C supply would have depended exclusively on animal food sources. Thereby, pathologies attributable to Vit C deficiency in several Neanderthal skeletons from Kiik-Koba (Crimea) have been described [54]. The diagnosis of an adult Neanderthal man in La Ferrassie indicated that he may have suffered scurvy in addition to lung disease [55]. Gardner and Smith [56] inventoried all the pathologies found in Neanderthal bones at the Krapina site, and some cases of porotic hyperostosis were found, which were attributed to scurvy. Other findings in human fossil assemblages from the early Upper Paleolithic (UP) in Mladec (Central Europe) were hemorrhagic processes due to scurvy [57]. In another report on three Neanderthal bones found in the French cave of Combe-Grenal, bony lesions were interpreted as the result of a reaction to chronic hemorrhages, as a possible result of scurvy [58].

1.3. Vit C Status of Arctic Populations: Implications for MIS 3 Hominins

Human groups that are supposed to have a diet more or less similar to that of Northern European M3H, such as Inuit people, may offer clues as to their Vit C-dependent nutritional status. This human group constitutes the current exception to the reliance on plant foods. For most of the year, Inuit people depend on mammals and fish for subsistence, and their survival is possible due to some amounts of Vit C found in mammal organs, while the gathering of plants is possible only in the short Arctic summers, although some Inuit groups never practice this [59].

Specifically, in the Arctic environment, it was found that Vit C requirements are similar to those in temperate climates, and both Inuit and Caucasoids can subsist on ascorbic acid intakes of less than 15 mg daily without showing clinical evidence of Vit C deficiency [60]. Some studies have suggested that the Inuit are able to obtain a minimum level of Vit C from a diet of frozen/raw, fermented, and dried animal food [61]. Moreover, the daily needs of Vit C also depend on genetic factors: Inuit are genetically characterized by a high Haptoglobin 1 allele frequency, which provides them with a greater antioxidant capacity, and therefore they are less likely to suffer from scurvy [62].

Adaptation to a low intake of Vit C offers a clear evolutionary advantage. The metabolism of Vit C, including absorption and its uptake by several cell types, is inhibited by increasing glucose concentration due to a glucose–ascorbate antagonism: due to their molecular similarity, glucose hinders the entry of Vit C into cells [63]. Thus, Arctic populations that are largely dependent on foods of animal origin, whose diets are low in carbohydrates, would need significantly lower amounts of Vit C than are recommended for Western societies. Then, an evolutionarily adapted human diet based on meat, fat and offal would provide enough Vit C to cover physiological needs and to ward off diseases associated with Vit C deficiency [63]. However, according to Høygaard and Rasmusson [64], who performed studies on the nutrition and physiopathology of Eskimos, analyses of Vit C in their blood reflected hypovitaminosis C and scurvy levels for 47% and 18% of their population, respectively. Other researchers indicated that it is highly probable that Inuit with a traditional nutrition live on the edge of scurvy [65]. It has been stated that a reliance on some animals, such as reindeer (Rangifer tarandus L.), which has been widely cited for both Inuit and several North European M3H populations, could have caused the onset of scurvy. In this regard, Geraci and Smith [59] described the occurrence of subacute scurvy in several Inuit children when consuming frozen reindeer for several days. Consistently, Vit C availability could have been a bottleneck for the survival of M3H, especially in the long winters, when there is a notable shortage of food plants.

Long ago, Levine [66] and Stefansson [67] reported that by following an exclusive animal food diet, it is possible to prevent the onset of scurvy. Interestingly, in all reported cases, such diet included viscera or meat from marine mammals or birds, such as penguins. In this regard, it was argued that the antiscorbutic properties of the meat in the diet of Arctic explorers and inhabitants of the polar regions lie in the fact that the meat was obtained almost entirely from seals and bears, and included not only muscle tissue but other tissues, such as liver [68]. As discussed below, marine mammals and birds are adequate Vit C sources, able to prevent the appearance of scurvy. However, marine mammals were marginally available for M3H, and there are only reports on their exploitation in Gibraltar [69].

1.4. The Bottleneck of Vitamin C for the Survival of M3H

The reliance of hominins on the acquisition of large mammals during most of the Pleistocene had nutritional and bioenergetic implications: large prey contain high fat amounts, provide a high energy return, and the strategies and skills required to acquire small prey are different from those required to acquire larger prey. Thus, the increased use of plant foods and technological changes that appear in the UP could be explained as adaptations to the decline in large prey in the context of late Quaternary faunal extinction, and the resulting need to acquire smaller prey efficiently and to process higher quantities of plant foods [22,41,70,71,72].

As for Inuit, the availability of Vit C for M3H could have had a strong seasonal component. However, unlike M3H, Inuit people have regularly available fish all year round, and in some cases, seals, and cetaceans for hunting [59], which are notable Vit C sources, so Inuit people would have rarely suffered deficiency symptoms of this essential nutrient. The problem for the survival of M3H in Northern Europe was that under a very cold climate most of the year, there is an absence of plant foods to obtain Vit C. In this scenario, viscera have been identified as sources of this vitamin, which could have supplied the daily amounts necessary to survive [73]. However, the regular consumption of viscera would have had many added problems. First, this resource is limited because the highest proportion of the edible weight of any hunted mammal corresponds to meat and fat, and thus the dependence on animals supplying minor amounts of viscera, i.e., small prey, could have caused an erratic distribution of viscera to be consumed by the hominin groups. Secondly, viscera contain large amounts of water and bacteria, and therefore are subject to rapid spoilage, so their consumption is a priority after any hunting episode.

This work clarifies how mammal’s food resources could have supplied to M3H the daily amount of Vit C needed to maintain good health. I hypothesize that the acquisition of viscera from large- and megafaunal elements by M3H had, besides other physiological roles, the function of totally or partially supplying the daily amount of Vit C needed for hominin groups’ survival, and that obtaining this essential nutrient from small prey would not have been as effective as from the previous ones. This fact could have played a crucial role in the size and survival of hominin populations during several Paleolithic periods.

2. Material and Methods

Data were acquired from databases such as Scopus, Google Scholar, and similar resources.

The body weight for M3H was set at 65 kg, considering average values given for M3H both male and female individuals [73]. The total energy expenditure for hominins was computed following previous calculations for both male and female M3H adults, which was set at ~4500 kcal/day, following Guil-Guerrero’s calculations [73], which agrees with the other values recently calculated fir this [74]. However, the influence of daily energy requirements on Vit C status will be discussed for a 3000–4500 kcal/day range, according to recent calculations for Neanderthals’ energy expenditure [75].

The average protein content of meat from free range mammals was set at ~22 g/100 g, and the protein content of fatty tissues was ~7 g/100 g, which is the average value for several food mammals previously calculated [73]; thus, estimates from both tissues have been considered to calculate daily protein intake. The daily intakes of both meat and fatty tissues are conditioned by protein intake, for which the safe range was between 52 and 162 g daily, following Paddon-Jones and Rasmussen’s [76] and Bilsborough and Mann’s calculations [77]. Then, the maximum daily protein intake was set at 2.5 g/kg·day. This value corresponds to the maximum safe intake of meat, which also entails the highest intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) and Vit C [73]. Considering a muskox, for optimal nutrition, the maximum consumption of meat supplemented with fatty tissues was set at ~585 g of meat and ~485 of fatty tissues (e.g., subcutaneous fat), for a consumption of 2.5 g of protein per kg and day, and such proportions provide ~4500 kcal [73]. For the remaining animals, these amounts of meats and fatty tissues had small variations, given slight differences in energy provided by the meat and fatty tissues among the various mammals. Furthermore, the influences of possible adaptations to higher amounts of protein intake on Vit C status have also been considered for calculations.

The ascorbic acid content of the main organs of grass-fed mammals usually consumed by Paleolithic hominins is detailed in Table 1, and the ascorbic acid contents of farmed food animals are shown in Table 2. The energy (kcal) and ascorbic acid content of the subcutaneous fat, meat, and viscera of the animals that are evaluated in the present work were taken from previous works, as detailed in Table 3 and the Supporting Tables S1–S6. The average energy content and protein of viscera from the various mammals were considered to be similar to those of meat, as previously reported [73]. For extinct animals, such as the giant deer, woolly rhinoceros, and woolly mammoth, the data for the energy of the different organs and body proportions have been taken from their closest relatives, as indicated in the corresponding supporting tables.

Energy derived from carbohydrates was considered negligible as compared with that from fat and meat, assuming a consumption of ~50 g daily (~187 kcal, considering 3.75 kcal/g), as noted in the traditional Inuit diet [78]. For an adult, such energy represents ~4% of the daily energy, and thus this amount has not been considered in energy calculations.

The Vit C contents of the main organs of free-range mammals usually consumed by M3H are summarized in Table 1. Data on the Vit C content of farmed mammals are detailed in Table 2. Data on the Vit C content of muskox organs were calculated following data on Vit C concentrations and body organs’ weights, as detailed in Table 3. The Vit C contents of aquatic resources available to M3H are displayed in Table 4. Supporting Tables S1–S6 summarize data for organ weights, Vit C, and energy content of free-range mammals commonly consumed by M3H.

The size data of the M3H group were taken from previous calculations [79,80,81]. The size of the hunter group was taken from Smith [82]. The energy/meat/fatty tissues necessary to fulfill the daily needs of the hominin group was computed using paleodemographic data for M3H populations [83,84], and weighting food amounts for the different age groups proportionally, following the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee [85], as detailed in Supporting Table S7.

Table 1.

Ascorbic acid contents of the main organs of grass-fed mammals usually consumed by Paleolithic hominins.

Table 1.

Ascorbic acid contents of the main organs of grass-fed mammals usually consumed by Paleolithic hominins.

| Species | mg/100 g Fresh wt | Method of Vitamin C Determination | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow | |||

| Caribou/Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus L.) | 0.00 | Microfluorometric | [86] |

| Brain | |||

| Musk ox (Ovibos moschatus Zimmermann) | 12.80 | Tritation with 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol | [87] |

| Depot fat | |||

| Caribou/Reindeer (R. tarandus L.) | 1.80 | Spectrophotometric with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine | [59] |

| Caribou/Reindeer (R. tarandus L.) | 0.00 | Microfluorometric | [86] |

| Hearth | |||

| Caribou/Reindeer (R. tarandus L.) | 2.60 | HPLC-ED | [88] |

| Muskox (O. moschatus Zimmermann) | 1.50 | Tritation with 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol | [87] |

| Kidney | |||

| Caribou/Reindeer (R. tarandus L.) | 8.88 | HPLC-ED | [88] |

| Muskox (O. moschatus Zimmermann) | 5.90 | Tritation with 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol | [87] |

| Liver | |||

| Caribou/Reindeer (R. tarandus L.) | 23.76 | HPLC-ED | [88] |

| Caribou/Reindeer (R. tarandus L.) | 11.88 | Microfluorometric | [86] |

| Mean for caribou/reindeer liver | 17.82 ± 8.40 | ||

| Muskox (O. moschatus Zimmermann) | 10.40 | Tritation with 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol | [87] |

| Meat | |||

| Bear, polar (Ursus maritimus Phipps) | 1.00 | Spectrophotometric with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine | [59] |

| Bear, polar (U. maritimus Phipps) | 2.00 | - | [89] FDC ID: 169794 |

| Mean for polar bear meat | 1.5 ± 0.7 | ||

| Bear, brown (Ursus arctos L.) | 0.00 | - | [89] FDC ID: 173845 |

| Beaver (Castor spp. L.) | 2.00 | - | [89] FDC ID: 175294 |

| Bison (Bison bison L.) | 0.00 | HPLC-FD | [90] |

| Bison (B. bison L.) | 0.00 | Tritation with 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol | [91] |

| Bison (B. bison L.) | 0.00 | - | [89] FDC ID: 175293 |

| Mean for bison meat | 0.00 | ||

| Caribou/Reindeer (R. tarandus L.) | 0.86 | HPLC-ED | [88] |

| Caribou/Reindeer (R. tarandus L.) | 1.40 | Spectrophotometric with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine | [59] |

| Caribou/Reindeer (R. tarandus L.) | 0.00 | Microfluorometric | [86] |

| Caribou/Reindeer (R. tarandus L.) | 0.00 | - | [89] FDC ID: 173853 |

| Mean for caribou meat | 0.56 ± 0.69 | ||

| Horse (Equus ferus caballus L.) | 0.00 | Tritation with 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol | [92] |

| Horse (E. ferus caballus L.) | 1.00 | - | [89] FDC ID: 175086 |

| Mean for horse meat | 0.50 ± 0.71 | ||

| Moose (Alces alces L.) | 4.00 | - | [89] FDC ID: 174344 |

| Muskox (O. moschatus Zimmermann) | 1.50 | Spectrophotometric with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine | [59] |

| Muskox (O. moschatus Zimmermann) | 0.80 | Tritation with 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol | [87] |

| Mean for muskox meat | 1.15 ± 0.49 | ||

| Red deer (Cervus elaphus L.) | 0.00 | - | [89] FDC ID: 173855 |

| Wild boar (Sus scrofa L.) | 0.00 | - | [89] FDC ID: 175297 |

| Stomach | |||

| Caribou/Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus L.) | 0.45 | HPLC-ED | [88] |

Table 2.

Ascorbic acid contents of farmed food animals.

Table 2.

Ascorbic acid contents of farmed food animals.

| Organ/Animal | mg/100 g | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Red bone marrow | ||

| Beef | 1.0–3.7 | [93] |

| Brain | ||

| Beef | 19.20 | [94] |

| Lamb/sheep/mutton | 19.40 | [94] |

| Pork | 13.50 | [94] |

| Mean for brain | 17.37 ± 3.35 | |

| Heart | ||

| Beef | 7.00 | [94] |

| Lamb/sheep/mutton | 7.30 | [94] |

| Pork | 0.60 | [95] |

| Pork | 2.54 | [96] |

| Pork | 5.00 | [94] |

| Mean for hearth | 4.49 ± 2.89 | |

| Kidney | ||

| Beef | 10.40 | [94] |

| Lamb/sheep/mutton | 12.90 | [94] |

| Pork | 2.52 | [95] |

| Pork | 14.20 | [94] |

| Mean for kidney | 10.01 ± 5.23 | |

| Liver | ||

| Beef | 22.40 | [94] |

| Beef | 21.80 | [97] |

| Beef | 25.00 | [98] |

| Beef | 32.00 | [99] |

| Lamb/sheep/mutton | 25.00 | [94] |

| Lamb/sheep/mutton | 46.00 | [99] |

| Pork | 8.35 | [95] |

| Pork | 14.66 | [96] |

| Pork | 21.60 | [94] |

| Pork | 12.00 | [99] |

| Mean for liver | 22.88 ± 10.68 | |

| Lung | ||

| Beef | 38.50 | [94] |

| Lamb/sheep/mutton | 31.40 | [94] |

| Lamb/sheep/mutton | 24.50 | [100] |

| Pork | 13.10 | [94] |

| Pork | 27.00 | [100] |

| Rabbit | 29.00 | [100] |

| Mean for lung | 27.25 ± 8.42 | |

| Meat | ||

| Beef | 0.00 | [101] |

| Beef | 2.53 | [102] |

| Beef | 0.00 | [103] |

| Beef | 1.60 | [98] |

| Buffalo | 0.00 | [104] |

| Camel | 0.00 | [103] |

| Lamb/sheep/mutton | 0.60 | [105] |

| Mutton | 0.00 | [103] |

| Pork | 0.27 | [95] |

| Pork | 0.90 | [96] |

| Mean for meat | 0.66 ± 0.89 | |

| Pancreas | ||

| Lamb/sheep/mutton | 17.50 | [94] |

| Pork | 15.30 | [94] |

| Mean for pancreas | 16.40 ± 1.56 | |

| Spleen | ||

| Beef | 45.50 | [94] |

| Lamb/sheep/mutton | 23.20 | [94] |

| Pork | 19.51 | [95] |

| Pork | 27.22 | [96] |

| Pork | 30.00 | [94] |

| Mean for spleen | 29.09 ± 10.00 | |

| Tonge | ||

| Beef | 3.30 | [94] |

| Lamb/sheep/mutton | 6.80 | [94] |

| Pork | 4.40 | [94] |

| Mean for tonge | 4.83 ± 1.79 | |

| Tripe/intestines | ||

| Beef | 3.40 | [94] |

| Lamb/sheep/mutton | 6.60 | [94] |

| Mean for tripe/intestines | 5.00 ± 2.26 | |

| Subcutaneous fat | ||

| Beef raw | 0.00 | [89] FDC ID: 173091 |

| Lamb raw | 0.00 | [89] FDC ID: 174435 |

| Pork | 0.00 | [95] |

| Pork | 0.00 | [89] FDC ID: 167813 |

| Mean for subcutaneous fat | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| Thymus | ||

| Beef | 34.00 | [94] |

Table 3.

Organ weights, energy, and ascorbic acid contents of a medium-sized muskox (285 kg) a.

Table 3.

Organ weights, energy, and ascorbic acid contents of a medium-sized muskox (285 kg) a.

| Body% | g | Energy kcal/g | Total kcal | Vit C mg/g | Total Vit C in Organ, mg | Reference for Vit C | Reference for Organ wt.% | Reference for Energy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viscera | |||||||||

| Adrenal | 0.0209 | 59.5 | 0.680 | 40 | 0.392 | 23.3 | [87] b | [106] c | Estimated as testes |

| Bile | 0.0522 | 148.7 | 0.045 | 7 | 0.01 | 1.5 | [87] b | [107] c | Derived from [108] d |

| Blood | 3.4052 | 9704.7 | 0.700 | 6793 | 0.0007 | 6.8 | [109] e | [110] e | [111] e |

| Brain | 0.2210 | 629.8 | 1.234 | 777 | 0.128 | 80.6 | [87] b | [106] f | [73] g |

| Digestive tract | 5.3000 | 15,105.0 | 0.960 | 14,501 | 0.074 | 1117.8 | [86] b | [106] e | [112] f |

| Epididymis | 0.1098 | 312.9 | 0.680 | 213 | 0.042 | 13.1 | [87] b | [113] i | Estimated as testes |

| Eyes | 0.0393 | 112.0 | 3.260 | 365 | 0.007 | 0.8 | [87] b | [106] c | [89] FDC ID: 169801f |

| Heart | 0.4400 | 1254.0 | 1.120 | 1404 | 0.015 | 18.8 | [87] b | [114] b | [112] f, [115] f |

| Kidney | 0.1855 | 528.7 | 0.917 | 485 | 0.059 | 31.2 | [87] b | [114] b | [73] g |

| Liver | 1.0382 | 2958.9 | 1.240 | 3669 | 0.104 | 307.7 | [87] b | [114] b | [115] f |

| Lung | 1.3528 | 3855.5 | 1.090 | 4202 | 0.081 | 312.3 | [87] b | [106] c | [112] f |

| Pancreas | 0.1405 | 400.4 | 2.350 | 941 | 0.039 | 15.6 | [87] b | [116] e | [89] FDC ID: 169452 h |

| Spleen | 0.2284 | 650.9 | 0.900 | 586 | 0.06 | 39.1 | [87] b | [106] c | [73] g |

| Testes | 0.5160 | 1470.6 | 0.680 | 1000 | 0.182 | 267.6 | [87] b | [107] c | [89] FDC ID: 172619 c |

| Tongue | 0.1891 | 538.9 | 2.60 | 1401 | 0.01 | 5.4 | [87] b | [107] c | [89] FDC ID: 168985 f |

| Thyroid | 0.0196 | 55.9 | 0.680 | 38 | 0.038 | 2.1 | [87] b | [107] c | Estimated as testes |

| Total viscera | 13.2584 | 37,786.4 | - | 36,423 | - | 2243.8 | - | - | - |

| Bones | 14.2748 | 40,683.2 | 0.000 | - | - | - | - | [114] b | - |

| Bone marrow | 2.5000 | 7125.0 | 4.837 | 34,464 | 0.000 | 0.000 | [86] f | [117] f | [73] g |

| Dissectible fat | 17.7099 | 50,473.2 | 7.894 | 398,436 | 0.000 | 0.000 | [87] b | [114] b | [73] b |

| Total fat | 57,715.5 | - | 432,899 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Muscles | 41.9084 | 119,438.9 | 1.132 | 135,205 | 0.0115 | 1373.5 | [87] b; [59] b | [114] b | [73] b |

| Skin | 9.0043 | 25,662.3 | 5.440 | 139,603 | 0.0050 | 128.3 | [89] FDC ID: 234130 j | [110] e | [89] FDC ID: 2341308 j |

| Rest k | 3.6675 | 10,452.4 | 1.000 | 10,452 | 0.0010 | 10.5 | Estimated | Estimated | Estimated |

a Body weight was taken from Knott et al. [118]; b muskox sample; c sheep sample; d based on 0.51% fats in bile; e goat sample; f Rangifer sample; g mean for several food animals; h beef sample; i macaco sample; j pork skin rinds; k tendon, blood vessels, etc.

Table 4.

Vitamin C contents of birds and aquatic food resources available to Paleolithic hominins.

Table 4.

Vitamin C contents of birds and aquatic food resources available to Paleolithic hominins.

| Scientific Name | Organ | mg/100 g Fresh wt | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birds | ||||

| Duck | Anas platyrhynchos | Flesh | 6.2 | [89] FDC ID: 174469 |

| Goose | Anser anser | Flesh | 7.2 | [89] FDC ID: 172413 |

| Pigeon | Columba livia | Flesh | 7.2 | [89] FDC ID: 171079 |

| Quail | Perdix perdix | Flesh | 7.2 | [89] FDC ID: 172419 |

| Seaweeds | ||||

| Dulse | Palmaria palmata | Thallus | 0.61 | [119] |

| Irishmoss | Chondrus crispus | Thallus | 3 | [89] FDC ID: 168456 |

| Kelp | Laminariales | Thallus | 3 | [89] FDC ID: 168457 |

| Kombu | Laminaria sp. | Thallus | 1.34 | [119] |

| Laver | Porphyra umbilicalis | Thallus | 39 | [89] FDC ID: 168458 |

| Laver | P. umbilicalis | Thallus | 33.29 | [119] |

| Sea spaghetti | Himanthalia elongata | Thallus | 46.66 | [119] |

| Wakame | Undaria pinnatifida | Thallus | 3 | [89] FDC ID: 170496 |

| Invertebrates | ||||

| Abalone | Haliotidae | Edible portion | 2 | [89] FDC ID: 174212 |

| Crab | Clibanarius vittatus | Whole body | 1.8 | [120] |

| Eastern Oysters | Crassostrea virginica | Edible portion | 3 | [121] |

| Eastern Oysters | Crassostrea virginica | Edible portion | 4.7 | [89] FDC ID: 175172 |

| Mussels | Mytilus edulis | Edible portion | 8 | [89] FDC ID: 174216 |

| Octopus, common | Octopus vulgaris | Edible portion | 5 | [89] FDC ID: 174218 |

| Polychaete | Neanthes virens | Whole body | 1.56 | [122] |

| Sea urchin | Paracentrotus lividus | Gonad | 26.57 | [123] |

| Squid, mixed species | Cephalopods | Edible portion | 4.7 | [89] FDC ID: 174223 |

| Shrimp | Palaemonetes pugio | Edible portion | 1.64 | [122] |

| Snail | Polinices duplicatus | Kidney | 2.34 | [120] |

| Whelk, unspecified | Mollusk | Edible portion | 4 | [89] FDC ID: 171983 |

| Freshwater fish | ||||

| Arctic char | Salvelinys alpinus | Whole fish | 5.8 | [59] |

| Arctic char | Salvelinys alpinus | Flesh | 1.8 | [59] |

| Arctic char | Salvelinusalpinus | Flesh | 1.3 | [88] |

| Bass, fresh water, mixed species | Perciformes | Flesh | 2 | [89] FDC ID: 174184 |

| Broad whitefish | Coregonos nasus | Flesh | 2.83 | [88] |

| Carp | Cyprinidae | Flesh | 1.6 | [89] FDC ID: 171952 |

| Carp | Cyprinus carpio | Flesh | 1.14 | [124] |

| Cisco | Coregonos nasus | Eggs | 49.6 | [87] |

| European catfish | Silurus glanis | Flesh | 2.15 | [124] |

| Pike, northern, raw | Esox lucius | Flesh | 3.8 | [89] FDC ID: 173680 |

| Pike perch | Sander lucioperca | Flesh | 1.91 | [124] |

| Whitefish | Coregonus clupeaformis | Eggs | 12 | [89] FDC ID: 167643 |

| Salmon, chinook | Oncorhynchus tshawytscha | Flesh | 4.0 | [89] FDC ID: 173688 |

| Sculpin | Myoxocephalus spp. | Flesh | 1.05 | [88] |

| Trout, rainbow | Oncorhynchus mykiss | Flesh | 2.4 | [89] FDC ID: 175154 |

| Trout, rainbow | Oncorhynchus mykiss | Flesh | 1.8 | [121] |

| Marine fish | ||||

| Mullet | Fam. Mugilidae | Flesh | 1.2 | [89] FDC ID: 175123 |

| Needlefish | Fam. Belonidae | Brain | 29.5 | [122] |

| Gill | 3.88 | [122] | ||

| Kidney | 2.93 | [122] | ||

| Flesh | 1.41 | [122] | ||

| Liver | 2.13 | [122] | ||

| Snapper, mixed species | - | Flesh | 1.6 | [89] FDC ID: 173698 |

| Marine mammals | ||||

| Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | Mattak | 36.02 | [88] |

| Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | Mattak | 31.51 | [88] |

| Ringed seal | Phoca hispida | Brain | 14.86 | [88] |

| Liver | 23.8 | [88] | ||

| Liver | 35 | [59] | ||

| Meat | 1.55 | [88] | ||

| Meat | 3 | [59] |

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sources of Vitamin C for M3H

The Vit C contents of several organs of free-range mammals usually consumed by M3H are summarized in Table 1. Notice that most muscles contain negligible amounts of, or lack, Vit C. The best Vit C-supplying meats are those of moose and beaver (4 and 2 mg/100 g of fresh weight, [89]). However, no analytical data have been found in the literature supporting such relatively high figures. In any case, moose and beaver bone remains are not very frequent in Paleolithic faunal assemblages (e.g., [125,126]; thus, such meats can be considered marginal in M3H diets. Among meats, that of muskox contains small amounts of Vit C, ~1 mg/100 g, which would need to be taken in large amounts (>1 kg) to reach the 10 mg daily amount needed to prevent scurvy [48,49]

As for Vit C data in Table 1, those corresponding to Geraci and Smith [59] should be considered with caution. This is because the method used for Vit C determination was the spectrophotometric approach, using 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine, and this usually produces an overestimation of total Vit C in the analyzed samples [127].

Unlike meat, viscera constitute an appropriate source of this vitamin (Table 1). For instance, ~110 g of kidney from caribou could have fulfilled the daily needs of Vit C for M3H. Although nutritional data on viscera of free-range mammals are very scarce, data on viscera and meats of farm animals are better known, and those on commonly consumed mammals are shown in Table 2. Notice that Vit C contents in the viscera of these animals do not differ from those of wild ones. Interestingly, the Vit C contents of each organ are quite similar among the various species.

Nowadays, there are discrepancies in global Vit C recommendations for optimal health, ranging from 40 to 220 mg Vit C per day [128]. Such differences are due to the variety of recommendations; for instance, to prevent scurvy or for optimizing health. Scurvy can be effectively prevented with ~10 mg Vit C/day [48,49,129]. However, subclinical Vit C deficiency may be much more common than overt disease, and it is difficult to recognize, because the early symptoms of deficiency are unremarkable and nonspecific [130]. Examination of the data in Table 1 and Table 2 suggests that viscera, not meat, would have allowed M3H to survive on a carnivorous diet. Moreover, for obtaining the daily needs of ~4500 kcal at such times only from lean meat, almost ~4 kg would have been necessary. The toxicity of nitrogen inherent to high levels of meat consumption would have made this option unfeasible and, given an absence of Vit C in most meats, in no case would the daily amount of Vit C required to avoid the deficiency status have been obtained. The better strategy to achieve the daily energy needs for M3H survival would have involved consuming the higher toxicologically safe amount of meat, supplemented with fatty tissues [73]. This would have allowed for obtaining the maximum amounts of essential omega-3 PUFA and in some cases minor amounts of Vit C. However, the only way to acquire the Vit C required for survival would have been supplementing the diet with viscera from mammals or, when available, by eating plant foods, fish, or birds.

Although a strictly carnivorous diet has been cited for human groups, the consumption of some vegetable organs during the winter by M3H could have been marginally practiced, perhaps as famine foods. In this regard, some plant foods, particularly underground storage organ (USOs), have been proposed as valuable resources to foragers in the late winter and early spring, and it was speculated that such organs would have been carbohydrates and Vit C suppliers during the winter for Paleolithic hominins [131]. For instance, chicory (Cichorium intybus L.) roots contain 5 mg/100 g of Vit C ([89] FDC ID: 169993); thus, USOs could have acted as antiscorbutic foods. However, it is difficult to consider the consumption of USOs in winter by M3H: most of them are cryptic in winter; thus, efficient harvesting is unlikely as this activity would have had high energy costs. This way, given the low energy content of USOs (e.g., 72 kcal/100 g for chicory ([89] FDC ID 169993), the energy return derived from their collecting would have been very low. Another possibility would have been to freeze plant organs to be consumed in winter. Although the preservation of frozen foods has been reported for some traditional Arctic societies, the possibility that this was done by M3H for the long-term preservation of foods seems remote, as there is no archeological evidence to support it. Other plant foods resistant to spoilage and therefore storable during the winter are seeds, such as those of poppies, oak, cereals, and flax. However, all of these contain negligible amounts of Vit C [89].

Recently, pine and juniper needles have been proposed as winter sources of ascorbic acid for Pleistocene hominins in northern Eurasia [132]. This possibility seems to be highly unlikely. Even though, like most plant organs, they contain Vit C, their potential toxicity makes their consumption on a constant basis unfeasible, although these could have been drunk occasionally as a therapeutic remedy [66]. However, most of these vegetable organs contain turpentine and other toxic compounds that can cause various health problems, including hepatotoxicity [133]. Moreover, in pregnant women, both juniper and pine needles can pose risks to the developing fetus as the toxic substances present in needles can cross the placenta and potentially cause harm, while laboratory and animal studies have suggested that Juniperus and Pinus species share similar chemistries and have antifertility effects in both males and females [134]. Therefore, the presence of charcoal derived from pine or other coniferous wood and phytoliths in hominin sites is probably a reflection of the suitability of this material as a rapid fire-starter due to its high resin content, instead of a proof of pine tea-making.

3.2. M3H Viscera, a Valuable Food Resource Hard to Equally Distribute among M3H

Most viscera are nutritionally advantageous over lean meat. For example, caribou liver in addition to Vit C contains at least twice as much fat as meat from the same animal. As muscles, viscera contain high moisture amounts, although the latter ones have a slightly lower protein and higher fat contents than meat [135]. The consumption of viscera has been widely practiced by past and present peoples. Brain, kidneys, liver, heart, and lungs, in addition to Vit C, provide valuable amounts of essential PUFA [73], folacin, and vitamin A [136]. Usually, most viscera are immediately consumed after hunting. This is because these contain large amounts of water and nutrients, which favor the rapid development of microorganisms coming from the digestive tract. For instance, buffalo liver has been evaluated as microbiologically and organoleptically acceptable up to the third day at 4 °C storage [137]. Priority given to the consumption of viscera has been reported for all hunter groups belonging to native cultures, and for chimpanzees. As the animal corpse is completely corrupted in a very short time if not disburdened of its viscera, hunters have no choice but to start by consuming these [138]. This is universally described. For instance, at the Howard Goodhue site, central Iowa, late prehistoric exploitation by Plains Indians of bison, elk, and deer was described by McHugh [139]: “As they worked, most of the participants snacked on raw morsels taken still warm from the slain buffalo, including livers, kidneys, tongues, eyes, testicles, belly fat, parts of the stomach, gristle from snouts, marrow from leg bones, and the hoofs of tiny unborn calves as well as tissue from their sacs.”

A more recent case has been exhaustively described. Inuit people from Kivalina, the northwestern coast of Alaska, develop a well-established protocol for the consumption of caribou viscera. After killing, the stomachs and kidneys were immediately eaten raw, while kidneys were sometimes saved, though they were mostly eaten raw. In the same way, the heart and liver were also eaten as soon as they become available [140].

Several authors reported evisceration activities through direct ethnographic observations for understanding carcass acquisition and butchery by M3H. Evisceration processes have been detected through cutmarks occurring on the ventral surface of the ribs [141,142]. It is commonly reported that viscera were the first animal organs eaten in the consumption sequence, while a great number of authors have reported that viscera are highly valued organs by all current and past hunting peoples (e.g., [143]). Previously, through a nutritional model, it was calculated that the daily meal for Paleolithic hunters should have consisted of ~1250 g of animal food, including both meat/viscera and fatty tissues [73]. This value agrees with previous observations about the daily amount of food consumed by Inuit peoples [59], which reaches ~1200 g daily for males and somewhat less for women, corresponding to the ingestion of a mix of flesh, marrow, and selected viscera from several animals.

Considering the high content of Vit C in viscera, priority in consumption would also have bene determined by this vitamin. However, viscera provide a low fraction of the total caloric content of the prey, and whether small- or medium-sized animals were hunted, it would have been difficult to make viscera distribution equitable among the whole hominin group.

3.3. Paleolithic Mammals as Vitamin C Suppliers

Table 3 and Supporting Tables S1–S6 detail the organ weights, Vit C and energy content of most representative mammals whose remains are usually found in Paleolithic sites. Data for Vit C content of the various mammal organs are well known for muskox [87], while for other hunted mammals, data are incomplete. However, as deduced from Table 1 and Table 2, the Vit C contents in the organs of all mammalian species are quite similar, and, in the absence of specific data, figures for the Vit C of extinct species could be considered very similar to those of their current relatives.

Bone marrow in this work has been computed considering the energy contribution of its fat content. Many authors have cited the predilection of M3H for this nutritional resource (e.g., [144]), and there is evidence of the storage and delayed consumption of bone marrow at the Middle Pleistocene in Qesem Cave, Israel [145]. The nutritional content of bone marrow is highly variable depending on the age of the animal, the bone considered and the target tissue (red marrow vs. yellow marrow). The limited data available regarding the bone marrow of grass-fed Paleolithic mammals indicate negligible amounts of Vit C contained therein (Table 1). Although this topic is worthy of detailed studies, for now, it is assumed that the fat content of the bones was the target of M3H.

The nutritional and energy needs of hominins should be computed as a group rather than at the individual level, since a small-sized group of Paleolithic hunters would have survived whether the group was able to respond to the nutritional needs of each of its individuals. Calculations for Vit C intake have been undertaken for a 22-individual hominin group, as detailed in the Material and Methods Section. Estimates of Vit C intake are also performed for bigger groups, considering a 20–50-individual range for M3H groups [80], and for both higher daily protein and lower energy intakes.

Muskox (Ovibos moschatus Zimmermann, 1780) is probably the best-known animal in relation to the Vit C content in its various organs [87]. Given that this mammal was also studied in detail regarding its body and organ weights [114], both sets of data allowed for computing the total content of Vit C in the different organs of a real animal (Table 3). Some gaps in the data for the Vit C content of minor organs have been filled in by establishing analogies with similar free-range mammals, as detailed in this table. The main organs for food purposes are viscera, muscles, and fatty tissues (subcutaneous fat, marrow, and visceral fat), while other organs of the animal would be wasted and thus not regularly consumed (skin, some bones, blood vessels, etc.).

Modeling the consumption of muskox will help us to understand the features of the distribution of Vit C among an M3H group. A case of a 285 kg hunted animal was selected from the literature (Table 3). The whole viscera would have provided about ~36,000 kcal and ~2244 mg of Vit C, the muscles would yield ~135,000 kcal and ~1400 mg of Vit C, and the fatty tissues ~433,000 kcal and no Vit C.

Considering a 22-individual group, according to paleodemographic data for Paleolithic populations [83,84], the energy needs are ~76,000 kcal (Supporting Table S7), and a minimum of 220 mg of Vit C daily would also have been needed [48,49,129] (this last value is for short-term survival). As implied, the optimal consumption of each individual would have been that which allowed the ingestion of the maximum safe amount of proteinaceous and visceral tissues (sources of essential PUFA and Vit C).

Obviously, the equitable distribution of viscera would have been of crucial importance since the consumption of extra amounts of Vit C-rich organs by some individuals would have had deleterious effects on the remaining individuals. Whether viscera of muskox were equally distributed among the 22-people group on the hunting day, the group would still have had a deficit of ~40,000 kcal, which should have been fulfilled by variable amounts of meat and fatty tissues. Such a deficit could have been covered by ~5.2 kg of meat (~5900 kcal) and the remainder would have been fulfilled with ~4.3 kg of fatty tissues (~34,000 kcal). Then, on the hunting day, ~2300 mg of Vit C would have been available for the 22-hominin group, and an intake of ~105 mg of Vit C for each individual was expected. From the second day, the remaining energy content (~129,000 kcal from meat and ~400,000 kcal from fatty tissues) of the muskox carcass would have allowed enough energy for about 12 days (considering meat) and 6 days (considering fatty tissues), according to calculations detailed in Supporting Table S7. Thus, it is likely that an absence of fatty tissues in the diet would have forced a new hunting episode, given a surplus of meat over fatty tissues during the 6-day period. Within such a viscera-free period, Vit C intake would have been ~6 mg daily, all of which would have been obtained from the animal’s muscles. Obviously, for larger hominin groups, the amount of Vit C consumed by each individual on the hunting day would be less, although probably sufficient for the whole group, and after a Vit C-deficiency period it is likely that a new hunting episode would occur earlier.

Considering daily protein intake higher than the 2.5 g safe value used for previous calculations, i.e., 3.5 g/kg·day, as indicated for well-adapted athletes [146], and similar energy needs, ~440 g of fatty tissues and ~895 g of meat would have been needed to achieve 4500 kcal for adults. This situation would have allowed a longer period for consuming the whole carcass, which would have delayed the start of a new hunting event and thus scurvy would have been more likely. As for muskox, the consumption of its meat would allow for obtaining ~10 mg of Vit C daily, which is on the threshold of a satisfactory Vit C intake. However, it is necessary to consider that the meat of this mammal is the richest source of Vit C among all considered free-range mammals, and such Vit C intake would be unattainable by consuming meat from other mammals. Then, at the protein level of 3.5 g/kg·day, the amount of Vit C ingested daily from the meats of reindeer, horse, red deer, giant deer, and bison, would have been about 4, 4, 0.0, 0.0, and 0.0 mg, respectively, according to calculations made with data detailed in Table 1. Thus, except for muskox, the amounts obtainable of Vit C are lower than needed. Clearly, all meats from free-range mammals, except those of moose and beaver, contain Vit C amounts unable to provide 10 mg daily, the above-indicated threshold necessary to prevent the onset of scurvy. Then, higher protein intakes, including values up to 5.0 mg/kg·day, would marginally modify the above-described situation.

Concerning a lower daily energy expenditure than previously set, as suggested by Venner [75], it is likely that the daily intake of fatty tissues would progressively decrease to reduce energy expenditure, but protein intake would probably remain at a similar level. Thus, the effect of this situation on the daily intake of Vit C would be negligible. Furthermore, in the event that meat intake was reduced, Vit C status would be negative, accentuating the previously described deficit situations.

Unlike the previous case, the most realistic form of prey consumption would have been similar to the one that is detailed today for native hunter peoples; that is, viscera would have been consumed only by some preferential individuals. On the hunting day, the caloric content of muskox viscera would have been enough to feed around nine individuals—the group of hunters, probably adults. In the case of the exclusive consumption of viscera, these individuals would have obtained ~250 mg of Vit C each. The remaining individuals would have consumed muscles and fatty tissues, and each of them would have just fulfilled their daily needs of Vit C by consuming meat, as previously explained. Obviously, there are intermediate situations between those previously discussed, corresponding to cases where the viscera would have been partially transported to the base camp; however, all of them are unsatisfactory regarding Vit C status for all free-range mammals except for the muskox case. For all the remaining animal cases (see supporting Tables S1–S6), in the event of an insufficient viscera intake, all of them would have provided unsatisfactory nutritional results regarding the daily supply of Vit C, which would have led to chronic subacute scurvy, and thus to increased mortality.

Of course, several prey could have been captured in the same hunting episode, and this would have prevented the previously discussed situation of a Vit C deficit. In late Mousterian sites, communal hunting involved deferred consumption in anticipation of future needs. For instance, at the Les Pradelles site, the preferential introduction of nutritionally rich elements onto the site is consistent with the slaughter of several reindeer during the same hunting event [147]. Assuming this scenario, considering the low energy contents of the viscera of all prey, the hunters would have needed to catch several animals to ensure the equitable distribution of viscera and therefore an adequate intake of Vit C for the whole hominin group. However, considering the surplus of meat and fat once the viscera was consumed, it is likely that such food availability would have retarded a new hunting episode, and that latent scurvy occurrence would have been more than frequent.

For instance, when a medium-sized prey, such as a reindeer ( Supporting Table S1), had been caught, about ~76,000 kcal from its viscera would have been needed to meet the daily caloric needs of the 22-individual group ( Supporting Table S7), and considering that a reindeer specimen of about 135 kg provides ~19,500 kcal from its viscera ( Supporting Table S1), more than three prey would be necessary to this end. This would have involved the hunting and complete transport of at least four animals from the hunting site to the base camp. However, as previously exposed, not all viscera from medium-sized animals are transported to the base camp, and thus the actual amount of viscera consumed would have been less than the actual content in the prey. Moreover, considering the surplus of meat and fatty tissues available for the entire hominin group, these organs would have been used to meet the daily energy needs for several days, instead of Vit C-rich visceral organs. In any case, although not totally satisfactory, this last possibility seems the most feasible regarding the supply of Vit C to M3H groups, since the amount of viscera available would have been greater and it therefore would have been better distributed.

3.4. The Importance of Large Prey for Paleolithic Hominins

A predilection for large mammals by Paleolithic hominins has been widely reported. Driver and Maxwell [148] demonstrated that Old World Paleolithic hunters who lived in markedly seasonal environments conducted the killing of animals with high fat levels, such as bison. The acquisition of large prey was vital for M3H since they provided large amounts of fat, which constituted an energy reserve for the hominin group [71,149]. Considering large mammals, it is more than likely that big visceral organs were transported to the base camp, in addition to muscles and fat, since the hunting group would not have been able to consume all viscera completely. This would have favored an equitable distribution of visceral organs among all members of the hominin group for short-term consumption. Moreover, other parts of the carcass would have been transported from the hunting camp to the residential camp, i.e., fatty tissues, meat and large bones, and other high-utility elements of the animals, such as hides, to make clothes and other useful objects [150]. This implies high-energy expenditure and delayed consumption [151].

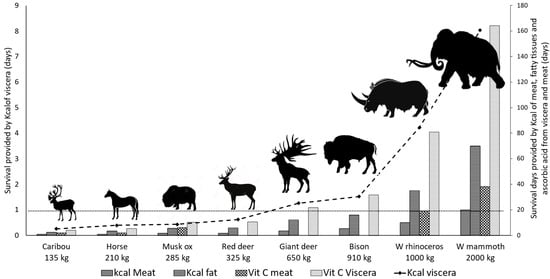

The survival of a 22-individual M3H group (days) facilitated by the caloric content of viscera, meat, and fatty tissues, and by the Vit C content of the viscera and meat from the typically hunted different-sized Paleolithic mammals, is plotted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Survival (days) of a 22-individual hominin group provided by typically hunted Paleolithic mammals, assessed by the energy content of viscera, meat, and fatty tissues, and by Vit C from viscera and meat. Daily needs were set at 76,000 kcal and 220 mg of Vit C. Data were obtained from Table 3 and Supporting Tables S1–S6. Data for giant deer were scaled from those of red deer. Note that the energy content of viscera provides at least one day of survival to the hominin group only when the size of the animal is approximately that of the giant deer.

As for energy needs, meat and fatty tissues provide longer survival to the hominin group, but these organs effectively lack Vit C. Concerning viscera, only those of giant deer and bigger animals contain enough energy for more than one day of survival, thus simultaneously fulfilling the daily needs of Vit C for the whole M3H group. On the other hand, the viscera of medium- and small-sized animals—for instance, horses and reindeer—can fulfill the needs for Vit C of the M3H group for more than one day, although without covering its energy needs. This causes a significant nutritional imbalance for the hominin group because it can survive for many days using the energy content of fatty tissues and meat from medium-size animals, although without obtaining enough Vit C for preserving good nutritional status. Furthermore, as previously described, the surplus of carcasses would have discouraged hunters from obtaining new prey, and therefore the M3H group would be doomed to consume foods lacking significant amounts of Vit C for several days.

Conversely, the hunting of a single large mammal, e.g., a mammoth, would have provided viscera to the M3H group more effectively than that of a large number of medium- and small-sized animals. From this mammal, just the liver (~65 kg) would have provided the ~9.890 kg daily requirement of a proteinaceous organ for ~7 days to a 22-individual M3H group, while providing energy-rich fatty tissues, and it would also have been enough to meet the energy needs of larger hominin groups for some days (see Supporting Table S6). Besides the daily needs of Vit C, this organ would have fulfilled the daily requirements for several essential nutrients, such as omega-3 and omega-6 PUFA and vitamin A, for the whole M3H group. Considering the presence of other large viscera in mammoths, such as kidneys (~11 kg) and brain (~3.6 kg), which contain high amounts of Vit C and omega-3 PUFA, good-quality nutrients for the whole hominin groups are expected from a single specimen. Viscera would have been preserved below 4 °C (for example, stored under ice), to be consumed in short- or medium-periods, probably in moderate amounts and supplemented with meat and fatty tissues to avoid possible toxicities due to excesses of vitamin A. So, the advantages of hunting large animals over small ones are clear, not only considering energy acquisition. Concerning viscera, the hunting of a medium-size mammoth would have been equivalent to that of approximately 30 reindeers, and viscera, not meat, would have contributed to fulfilling the daily needs of Vit C for the M3H group for several days. Additionally, when large prey was caught, there could have been a surplus of meat and fat after the consumption of the viscera. However, it is more than likely that not all parts of the carcasses from such large prey would have been transported to the base camp. Logically, the hunter group would have transported the optimal amount to subsist on based on the longevity of the meat and viscera, leaving the rest at the hunting site. The transport of elements of large carcasses would have also been conditioned by the number of carriers, damage sustained when the animal was wounded, and by the nutritional status of the individual animal [152]. In this regard, in studies on walrus exploitation during the Paleoeskimo period at the Tayara site, Arctic Canada, it has been described that in the process of walrus butchering, which animals reach 675 kg on average, all the abdominal viscera were recovered and transported in parts or consumed locally [153].

Considering small-sized animals, meeting Vit C needs would have required intense hunting activity, beyond covering the energy needs of the hominin group. Furthermore, food acquisition would not have focused on viscera, and once they had achieved the required amount of meat and fatty tissues for several days, the hunting activity would have stopped, thus depriving the M3H group of the Vit C needed to survive during the extreme winters of the cold events characteristic of the MIS 3.

3.5. The Decline of in Mammals during the Marine Isotope Stage 3: Differential Consequences for the Vit C Status of M3H

MIS 3 was an interstadial stage, a relatively warm climatic period that developed roughly between 60 and 50 and 30 ka. Several very cold periods, known as Heinrich (H) events, developed during the MIS 3 as a result of a partial collapse of the North American ice sheet margins [154]. The early UP is included in this period, which corresponds to an episode of significant climatic deterioration associated with a reduction in mammalian and plant species diversity. Then, the rapid cooling characteristic of H events could have produced drastic periodic reductions in food resources [155]. All the previous suggests the extreme difficulty of obtaining Vit C within the H events from the progressively declining plant foods [21], and from large-size animals, as a consequence of their decline [22,156], which could have led to the gradual onset of chronic scurvy-induced malnutrition. Specifically, mammoth decline is confirmed by the more frequent use of ivory at Châtelperronian sites than at the later Aurignacian ones [157]. In this regard, it has been demonstrated that hominins extirpated megafauna throughout the Pleistocene, and when the largest species were depleted, the next-largest were targeted [70]. Eeuwes [158] collected spatiotemporal data on all archeological and paleontological finds of megafauna weighing above 2000 kg and hominin species between 71.5 ka and the present. Among others, several mammoth species and woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis Blumenbach) were selected. Interestingly, he found fewer megaherbivore species per time frame before 40 ka, and after that, an increasing number of AMH sites were found. However, both woolly rhinoceros and woolly mammoth recovered some millennia after this decrease, and their records increased in numbers, particularly for the woolly mammoth. Later, the gradual increase in the records of AMH coincides with a decrease in the records of these megafaunal elements till around 20 ka. Regardless of what caused such a decrease in large fauna (overkilling, climate change, or other causes), the underrepresentation of large fauna before 40 ka coincided with the disappearance of Neanderthals in Eurasia.

In Eastern Europe, climate change has been held responsible for the demise of Neanderthals. Cooling events in the late Paleolithic contributed to shifts from a periglacial moderate cold and wet climate to a colder and drier climate, and the opening of the landscape, involving shifts in seasonality, plant phenology, reindeer body size and animal population densities across Central and Western Europe. Overall, abrupt climate oscillations during the MIS 3 contributed to the decline of Neanderthal populations, notably because of habitat fragmentation [159]. M3H, especially Northern European animal food-adapted populations, could have faced difficulty adapting to environments with less big game. For instance, faunal data from the Saint-Césaire site, France, suggest that reliance on reindeer during this period would also have promoted declines in human population densities, and the MP/Upper Paleolithic (M/UP) transition represented for hominins a period of significant niche contraction in Western Europe [160]. In the open grasslands resulting from the cooling events characteristic of late Paleolithic, the Neanderthal diet was mainly based on meat from terrestrial animals, whereas Aurignacian’s AMH, whose dispersal in Europe took place during the MIS 3, exploited plants and aquatic foods more frequently than the former [19,161]. Furthermore, resource competition between both hominins may have accelerated the disappearance of the Neanderthal populations [12,162].

Recent studies of human subsistence strategies from the lower Paleolithic onwards have shown that hunter–gatherers in the western Mediterranean area had broader diets than those from adjacent, colder regions [39]. Thus, reliance on large mammals to obtain the necessary daily amount of Vit C could have been less marked for Neanderthals inhabiting the southernmost regions, as they would have regularly obtained this vitamin from wild edible plants. However, the cold steppe that southern Europe became during several H events, such as the H4 one, would have caused the decline in most of the plant foods sources of Vit C. In this regard, the cooling of a geographical area, the reduction in plant species, and this fact could have been decisive in the decline of Southern European Neanderthals. For instance, during the H4 event, an expansion of aridity over the Iberian Peninsula and the desertification of the south demonstrate that such events led to drastic changes over southern Iberia [163].

The situation of the decline in large prey during the OIS 3 period and the consequent effects on the survival of Neanderthals were preceded by similar ones. For instance, Earth’s climate experienced major warming during the Eemian, OIS 5e, 128–114 ka. The rapid climate change in this period altered ecosystems and the human population collapsed, maintaining itself only in a few regions. Evidence from a well-preserved archeological layer at Baume cave (Moula-Guercy, southeastern France) shows environmental upheavals, including the depletion of prey biomass at the beginning of the Upper Pleistocene, which contributed to the rise of cannibalistic behavior in Neanderthals [164].

3.6. Vitamin C-Rich Food Resources Available to M3H

In addition to the use of viscera, especially from large prey, M3H may have exploited other Vit C-rich foods. The use of aquatic food resources by Neanderthals and AMH is controversial. AMH in South Africa around 164 ka had the ability to fish and hunt marine mammals, thus it is likely that such knowledge traveled North into Europe with the AMH as they moved [44]. It has been argued that the diet breadth at MP and early UP should be assessed by C and N stable isotope ratios in fossil bone collagen when establishing the intake of aquatic foods, and by zooarcheological evidence too. This is because the interpretation of a human’s isotopic signature does not necessarily imply a significant proportion of aquatic-derived protein in the diet [165]. In this regard, an intensification in freshwater fish exploitation by AMH has been verified, in comparison with Neanderthals, which is supported by isotopic analyses of human bone (e.g., [166]).

The assemblages of fish bone provide evidence for a shift to new resources in connection with the colonization of most of Europe by AMH and the local extinction of Neanderthals. For instance, in Geißenklösterle (southwestern Germany), five species of fish from the Danube were identified, all of them belonging to the MP-Gravettian transition. Excavators identified fish bones and fish scales in the Aurignacian and Gravettian deposits [167]. This, however, was not the case in the MP deposits, which contained only a few fish remains [168], and this discovery associated with human sites took place after the occupation of Europe by AMH [169]. Moreover, the analysis of the fauna of the Swabian Jura (southwestern Germany), which contains some of the oldest and richest Aurignacian assemblages in Europe, show an increase in the exploitation of birds and hares, starting with the Aurignacian [45]. This fact could have been due to an incipient shortage of large mammals and to the necessity to hunt smaller and smaller game, which was possible thanks to modifications in hunting technology. Overall, this situation led to a diversification of the diet by AMH [70].

Marine resources have been part of the subsistence of Paleolithic hominins since very ancient times. In the Mediterranean Basin, the use and consumption of littoral resources (mollusks, fish, and marine mammals) has been documented from the MP [170], although the record of marine food remains has increased progressively in later times [171]. This fact proves the early diversification of the diet from the early UP onwards. Overall, the consumption of coastal resources from MP to UP contributes to a progressive change in the consideration of these resources from “marginal” to “usual” in the hunter–gatherers’ economy. The use of coastal seaweed resources leaves no remains, although these could have been used by M3H. Costal algae could have been harvested in parallel with mollusks, echinoderms, and fish, and would have contributed to balancing the diet, not just in terms of Vit C. However, evidence of this activity has been found mostly on the European Mediterranean coasts. Algae, echinoderms, mollusks, fish, and marine mammals contain Vit C in concentrations much higher than those found in terrestrial mammalians (Table 4).

Many algae contain Vit C in concentrations similar to fruits. Furthermore, invertebrates such as mussels, seashells, crabs, squid, and urchins are Vit C-rich sources. Table 4 summarizes the Vit C contributions of aquatic resources, determined by maximum daily protein intake. Notice that, unlike meat and fatty tissues, most of these resources can fulfill the daily needs of Vit C, as discussed above.

As for the fish from rivers and lakes, these would have been available to both AMH and Neanderthals. However, as previously discussed, the last hominins hardly left any traces of their consumption. Likewise, fish appear to have been more restricted to Southern European hominins. As noted in Table 4, the Vit C content of this resource is much higher than that of meat, and considering the daily amounts that were safe, whole fish consumption would have fulfilled the daily needs of Vit C for hominins. For example, consuming just 250 g of Atlantic salmon, which contains 4 mg of Vit C per 100 g of edible tissue, would have provided the daily amount of Vit C needed to prevent the development of scurvy.

In Western Europe, archeozoological analyses of Mousterian collections have shown that Neandertals regularly obtained large mammals and, to a lesser extent, small fast game such as rabbits [39], while in Iberia this hominin exploited birds [4]. The use of marine mammals would have provided significant benefits in terms of nutritional status. These, in addition to viscera, contain exceptionally Vit C-rich large organs—the skin and subcutaneous tissues. For instance, the concentration of Vit C in raw mattak from beluga (Delphinapterus leucas Pallas) is 36.02 mg/100 g [88]. Another important fact to be considered is that Vit C-rich organs of the terrestrial animals, such as the liver and kidney, represent a modest weight percentage of the total live weight of any mammal, thus, small- and medium-sized land mammals could have only offered a limited amount of Vit C to M3H. This is not the case of marine mammals; for instance, up to a quarter of the live weight of beluga is mattak [172]. However, as previously stated, there are only reports on the exploitation of marine mammals in Gibraltar [69].

The capture of fish and birds, whose meats are rich in Vit C (Table 4) and additionally contain omega-3 PUFA, requires strategies and skills different from those required to acquire large prey. Access to small quick game is limited by technical skills, but this skill is usually learned in late childhood [173]. Although it is documented that Neanderthals made use of such resources, AMH were more adapted to this type of complex hunting, thanks to newer and more effective learning strategies [174]. In this regard, AMH have more than 200 unique non-protein-coding genes regulating the co-expression of many more protein-coding genes in coordinated networks that underlie their capacities for self-awareness, creativity, prosocial behavior, and healthy longevity, which are not found in chimpanzees or Neanderthals [175]. Such cognitive capacities could have helped the domestication of dogs. There is evidence that the dogs or incipient dog remains found at some sites were from sub-Arctic and Arctic environments. In fact, the domestication of dogs may have predated what is traditionally accepted [176]. Considering that food animals contain much more meat than fat, AMH in Eurasia would have used the previously discussed surplus of meat from carcasses to share with incipient dogs [177]. This strategy would have favored the survival of AMH populations as compared to Neanderthal ones, since dogs would have helped the former in hunting and other well-known related tasks that still remain prevalent in current societies.

4. Conclusions

The results of this study underscore the importance of the viscera of large mammals as a source of vitamin C for Paleolithic hominins. Until now, the exploitation of large mammals by Paleolithic hunters was considered exclusively as a consequence of the high energetic return derived from their hunting. As demonstrated in this work, the meat and fatty tissues of terrestrial mammals could hardly have provided the daily amount of vitamin C that Paleolithic hominins needed to survive. Conversely, viscera from food animals could have supplied the Vit C needed for optimal health, while the regular intake of such a source of Vit C had key features. This food resource is limited because the highest proportion of the edible weight of any hunted mammal corresponds to meat and fatty tissues, and thus, reliance on small- and medium-sized animals supplying minor amounts of viscera could have caused an erratic intake of Vit C within the whole hominin group.

Paleolithic hominins experienced abrupt, large-magnitude changes in climate during the cold stages, known as Heinrich events, that occurred during the MIS 3 period, which caused changes in the biomes from which such hominins obtained plant and animal foods. In this context, the progressive decline of large mammals detected during such a period would have deprived Paleolithic hominins of a considerable proportion of the Vit C needed for survival, so they would have experienced a progressive deterioration in their nutritional status. In this context, there are proofs that Anatomically Modern Humans exploited birds and aquatic resources more successfully than Neanderthals, which allowed the former to develop a better Vit C-dependent nutritional status than Neanderthals during Heinrich events. However, in light of the current knowledge, more studies are needed to delve into the use of differential food resources between both types of hominins. This would help us to discern to what extent the decline in large mammals could have contributed to the demise of Neanderthals and to the evolutionary success of Anatomically Modern Humans.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/quat6010020/s1, File S1: Supporting Table S1. Organ weights, kcal and ascorbic acid content of a medium-sized reindeer (135 kg); File S2: Supporting Table S2. Organ weights, kcal, and ascorbic acid content of a medium-sized horse (210 kg); File S3: Supporting Table S3. Organ weights, kcal, and ascorbic acid content of a medium-sized reed deer (325 kg); File S4: Supporting Table S4. Organ weights, kcal, and ascorbic acid content of a medium-sized bison (910 kg); File S5: Supporting Table S5. Organ weights, kcal, and ascorbic acid content of a medium-sized woolly rhinoceros (2000 kg); File S6: Supporting Table S6. Organ weights, kcal, and ascorbic acid content of a medium-sized woolly mammoth (4000 kg); File S7: Supporting Table S7. Daily needs of energy, meat, and fatty tissues for a 2.5 g protein/kg·day muskox-fed 22-individualss M3H group.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support of Junta de Andalucía (Proyect P20_00806), Campus de Excelencia Internacional Agroalimentario (ceiA3), and Centro de Investigación en Agrosistemas Intensivos Mediterráneos y biotecnología Agroalimentaria (CIAMBITAL).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article and Supplementary Material.

Conflicts of Interest

The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

References

- Arsuaga, J.L.; Martínez, I.; Arnold, L.J.; Aranburu, A.; Gracia-Téllez, A.; Sharp, W.D.; Quam, R.M.; Falguères, C.; Pantoja-Pérez, A.; Bischoff, J.; et al. Neandertal roots: Cranial and chronological evidence from Sima de los Huesos. Science 2014, 344, 1358–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devièse, T.; Abrams, G.; Hajdinjak, M.; Pirson, S.; De Groote, I.; Di Modica, K.; Toussaint, M.; Fischer, V.; Comeskey, D.; Spindler, L.; et al. Reevaluating the timing of Neanderthal disappearance in Northwest Europe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2022466118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guil-Guerrero, J.L.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Worldwide research trends on Neanderthals. J. Quat. Sci. 2022, 38, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, C.; Carrión, J.S. Rapid ecological turnover and its impact on Neanderthal and other human populations. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staubwasser, M.; Drăgușin, V.; Onac, B.P.; Assonov, S.; Ersek, V.; Hoffmann, D.L.; Veres, D. Impact of climate change on the transition of Neanderthals to modern humans in Europe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 9116–9121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, W.E.; d’Errico, F.; Peterson, A.T.; Kageyama, M.; Sima, A.; Sánchez-Goñi, M.F. Neanderthal extinction by competitive exclusion. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houldcroft, C.; Underdown, S.J. Neanderthal genomics suggests a pleistocene time frame for the first epidemiologic transition. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2016, 160, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.H.; Janković, I.; Karavanić, I. The assimilation model, modern human origins in Europe, and the extinction of Neandertals. Quat. Int. 2005, 137, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalueza-Fox, C. Neanderthal assimilation? Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 5, 711–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degioanni, A.; Bonenfant, C.; Cabut, S.; Condemi, S. Living on the edge: Was demographic weakness the cause of Neanderthal demise? PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]