Abstract

We hypothesize that megafauna extinctions throughout the Pleistocene, that led to a progressive decline in large prey availability, were a primary selecting agent in key evolutionary and cultural changes in human prehistory. The Pleistocene human past is characterized by a series of transformations that include the evolution of new physiological traits and the adoption, assimilation, and replacement of cultural and behavioral patterns. Some changes, such as brain expansion, use of fire, developments in stone-tool technologies, or the scale of resource intensification, were uncharacteristically progressive. We previously hypothesized that humans specialized in acquiring large prey because of their higher foraging efficiency, high biomass density, higher fat content, and the use of less complex tools for their acquisition. Here, we argue that the need to mitigate the additional energetic cost of acquiring progressively smaller prey may have been an ecological selecting agent in fundamental adaptive modes demonstrated in the Paleolithic archaeological record. We describe several potential associations between prey size decline and specific evolutionary and cultural changes that might have been driven by the need to adapt to increased energetic demands while hunting and processing smaller and smaller game.

1. Introduction

The potential role of human overhunting in megafauna (>45 kg) extinctions during the Pleistocene is a subject of long debate. However, the effect of megafauna extinctions on humans has been seldom discussed.

The genus Homo underwent an extensive set of physiological, cultural, and behavioral changes during the Pleistocene (roughly 2.6 million to 11.7 thousand years ago). At the end of this period, humans had established themselves as a species of unprecedented ecological dominance. Most notable among these changes was the directional increase in brain volume in the lineages leading to H. sapiens, the habitual use of fire, periodical change of stone-tool technologies, big-game hunting, resource intensification, food production, and animal and plant domestication.

We hypothesize that large prey’s declining availability was a prominent agent of selection (sensu MacColl [1]) in human evolution and cultural change. We argue that H. erectus evolved to become a carnivore, specializing in large prey beginning 2 million years ago. Later, as prey size declined, humans adapted to acquire and consume smaller and smaller prey while adapting to maintain a constrained bioenergetic budget.

We first review the decline in prey size throughout the Pleistocene. We then discuss two sub-hypotheses at the base of the master hypothesis—1. acquiring animal-sourced food was critical to human survival and 2. humans preferred and adapted to acquire and consume large prey. The sub-hypotheses were presented in detail in three papers, which we briefly review here [2,3,4]. Having established the prey size decline and its potential effect on humans, we speculate on evolutionary and cultural adaptations in human prehistory that could have been caused by prey decline as an agent of selection.

Full testing of such a wide-ranging hypothesis requires many years of work, gathering and analyzing quantitative data about prey size dynamics in specific periods and places and quantifications of tempospatially associated specific evolutionary and cultural changes. Here, we present the hypothesis in broad brushstrokes with the intention of it generating interest and further exploration.

2. Pleistocene Decline in Prey Size

In recent years, it has become clear that the Late Quaternary megafauna extinction (LQE) is not the first megafauna extinction event that humans faced or caused. A long-term decline in megaherbivore (>1000 kg) diversity in Africa, beginning ~4.6 million years ago (Mya), was identified by Faith, Rowan, and Du [5]. Size 5 (>1000 kg) herbivore richness declined throughout the period, while size 4 (350–1000 kg) and size 3 (80 = 350 kg) herbivores began to decline around 1 Mya (Figure 2 in [5]). Faith et al. attributed the initial change to a drying climate and only later declines to H. sapiens’ hunting pressure. All size-decline trends continued throughout the Pleistocene. Smith et al. [6] also identified a reduction in African terrestrial mammals’ mean body weight during the Pleistocene, abruptly reversing a continuous growth trend of 65 million years. Particularly relevant to our hypothesis is that by the beginning of the Late Pleistocene, 126 thousand years ago (Kya), the mean body mass of mammals in Africa had declined to 50% of the expected value for such a large continent. This means that a substantial decline in the diversity and number of large herbivores occurred during the Middle Pleistocene. Smith et al. [6] attributed this substantial decline in diversity and number of large herbivores to the presence of the carnivorous humans on the continent during the Pleistocene (but see [7]).

In East Africa, a significant faunal turnover that resulted in prey size decline was identified between 500 and 400 Kya in Lainyamok, Kenya [8] and before 320 Kya in Olorgesailie, Kenya, during the period leading to the transition to the Middle Stone Age (MSA), and the subsequent appearance of H. Sapiens [9]. A continuous decline in the weighted mean mass of mammals in archaeological sites is also evident in the Levant starting at 400 Kya, where it is not associated with climate change [10,11]. The decline in megafauna continued or resumed globally during the Late Quaternary [12] and the Holocene [13]. In summary, in Africa, the Levant, and Europe, there was a continuous decline in prey size from the late Early and Middle Pleistocene, and a Late Pleistocene decline followed the arrival of H. sapiens to new continents and islands [14,15]. It is difficult not to feel that the temporal and geographical spread of the decline in the largest prey and its unidirectionality at each time and place is a result not of a changing factor (climate) but rather a constant factor (humans’ preference for large prey). The current risk of extinction is also skewed towards larger fauna [16]. Studies of hunting by recent indigenous populations who rely on subsistence hunting show that they extend their hunts to smaller prey only when large prey got depleted. This behavior often results in declines and local extinctions of large-bodied mammals [17,18].

The debate over the anthropogenic nature of extinctions remains active [7,19,20].

Zooarchaeologists often question whether archaeological faunal assemblages reflect prey selection or prey abundance. Hypothesizing that humans specialized in large prey (see Section 4), a decline in prey size in the assemblages cannot reflect changing prey selection, because if large prey animals were abundant, people would preferentially acquire them (see [21] for recent support).

In a 2014 book chapter Wilkinson writes, “The first task of the prehistorian must be to decide which trophic level the population he is studying occupied” [22] (p. 544). A solid estimate of the human trophic level throughout the period that we discuss here is essential in order to judge the strength of the effect on humans of prey size decline.

3. The Trophic Position of Humans

We recently published a multidisciplinary review of the evidence regarding the human trophic level evolution based on 25 lines of evidence. We adapted a palaeobiological approach, including human metabolism and genetics, body morphology, dental pathology, and life history. We also reviewed archaeological, ethnographic, paleontological, and zoological literature to identify changing patterns in faunal abundance, flora, lithic industries, stable isotopes, and other geoarchaeological data, and human behavioral adaptations to carnivory or omnivory that reflected past human trophic levels [4].

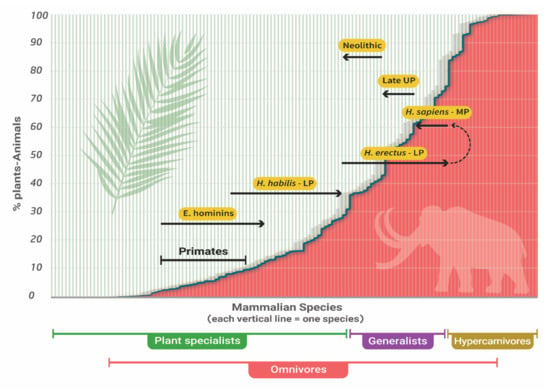

The review finds support for the notion that humans were carnivores starting from H. erectus. An analogy with other social carnivores indicates that carnivorous humans would have been hypercarnivores, consuming over ~70% of their calories from animal sources. A trend of declining trophic level (an increase in the plant component of the diet) is evident at the end of the MSA in Africa and the Upper Paleolithic (UP) period, and especially towards the end of the UP in the rest of the old world.

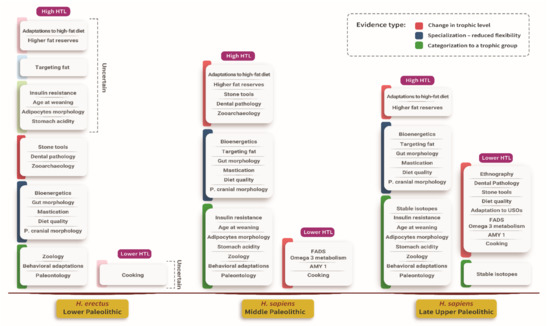

Figure 1 lists the evidence by human species and period. The full description of each line of evidence and a full list of references can be found in the source paper [4].

Figure 1.

A list of evidence by trophic level, human species, period, and type of evidence. The evidence was divided into three types–1 (red): evidence for a change in the trophic level, 2 (blue): evidence for specialization, and 3 (green): categorization to a trophic group. Uncertain association of an item with H. erectus appears in muted color.

Figure 2 draws the trophic level route that humans experienced during the Pleistocene according to the thesis in [4].

Figure 2.

Proposed evolution of the human trophic level during the Pleistocene. LP–Lower Paleolithic; MP–Middle Paleolithic; UP–Upper Paleolithic; E. hominins–Early hominins, (Australopithecus, Paranthropus). Background and position of primates adapted from [23]. Each line corresponds to the plants and animals’ food-source ratio of one mammalian species. Plant specialists and hypercarnivores–mammals that obtain over 70% of their food from plants and animals, respectively. Omnivores–any mammal that obtains food from both plants and animals.

4. Specialization in Large Prey

In [2], we claimed that 20th-century hunter-gatherers might be analogous in terms of ecological conditions and technology to humans at the end of the Paleolithic, after the Late Quaternary megafauna extinction, rather than to earlier Paleolithic humans. The late UP technology of bows and arrows, dogs, and grinding stones can be explained by the need to hunt smaller, fleeing animals and obtain an additional portion of the energy from plants at acceptable energetic costs. Thus, the 20th-century hunter-gatherers (HGs) hunting mix, dietary variability, and high plant consumption cannot be used as analogs for humans’ diets in earlier Paleolithic periods.

In [4], we argued that large animals are underrepresented in archaeological assemblages. We analyzed an actual case containing 60 hunts of the Hadza to find that giraffes contributed 57% of the hunts’ true total biomass, while their minimum number of individuals (MNI) was 14% of the total MNI and the number of identified specimens (NISP) was 7% of the total. However, only 8 of 11 giraffes were represented in the assemblage’s MNI, therefore, weighting the MNI’s by biomass still left a markable underrepresentation of the largest animal, pointing to potential substantial underrepresentation of very large animals such as elephants in archaeological assemblages.

Calculating and comparing the relative biomass abundance by prey size of a sample of sites from the Acheulian and Acheulo-Yabrudian, Early and Middle Stone Age, Middle Paleolithic Mousterian, Upper Paleolithic, and Aurignacian, we found that prey animals of a size above 200 kg provided 60–100% of the biomass in every sample. In each of the three comparisons, we found a decline in the relative biomass of the >200 kg animals in the later periods [4].

We reviewed four factors that made megaherbivores critically important to humans—1. High ecological biomass density, 2. Lower complexity of acquisition, 3. Higher net energetic return, and 4. High-fat content. Here we provide a summary of each factor; all references for the next section can be found in [2].

4.1. High Relative Biomass

Hempson et al. [24] estimated that 1000 years ago in Africa, the “nonruminants” group, which contains mainly megaherbivores, had a biomass density that is six times higher than the second densest group of “water-dependent grazers”. They predicted that “elephants dominated the African herbivore biomass, often having biomasses equivalent to those of all other [herbivores] species combined”. Even presently, after suffering extreme hunting pressure, studies find that megaherbivores, and in particular elephants, sustain high biomass densities. Elephants form 80–89% of the herbivores’ biomass in several African nature reserves.

4.2. Not Escaping–Easier Tracking and Less Complex Hunting Tools

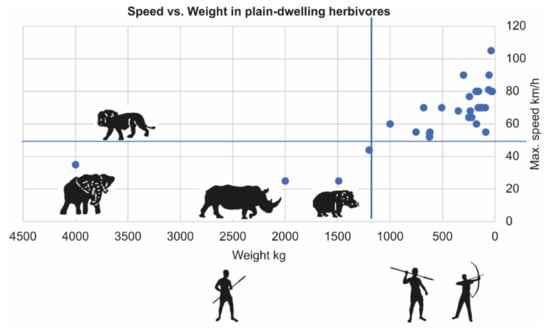

Megaherbivores do not rely on escape as a predator protection strategy, as evident by their low maximum speed compared to that of a lion (Figure 3). Unlike ungulates, megaherbivores lack specific predation risk alarm signals. When humans approach, they tend to stand still and may flee or charge when humans get closer. This behavior has several implications that make their acquisition by humans relatively energetically more profitable and technologically less complex (albeit not less courageous) than hunting smaller, fleeing prey. A common ethnographic method of hunting megaherbivores is to limit the movement in mud, a forest, or a pit, for example, and dispatch them with a thrusting spear [25,26]. Hunting faster, fleeing animals usually requires hunting from a distance by the use of more complex projectile weapons.

Figure 3.

Hunting methods as a function of prey weight and maximum speed. Megaherbivores (>1000 kg) are slower than a lion (horizontal line), so they do not rely on escape as a predation prevention strategy. Data in [27]. Composite projectile weaponry is required to hunt smaller and faster animals.

4.3. Larger Prey Contains Higher Body Fat Levels

Protein consumption in humans is limited to around 35–50% of the daily calories due to the liver and kidney’s limited ability to remove large quantities of the toxic nitrogen by-product of protein metabolism [28]. Thus, depending on the relative energetic returns and abundance of plants and animal fat, humans have to obtain 50–65% of their calories from either animal fat or plant fat and carbohydrates. According to ethnographic studies, the energetic return per hour on plant gathering is about one-tenth of medium-sized animals (Tables 3.3 and 3.4 in [29]); thus, it is expected that humans had an important obligatory requirement for animal fat [10].

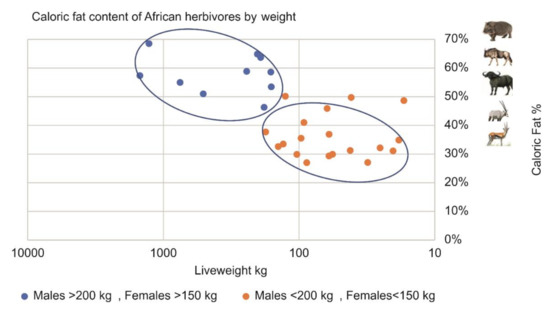

Pitts and Bullard [30] were the first to find that larger mammals contain relatively more fat than smaller animals. Our analysis of a dataset of 257 animals from 19 African herbivore species [31] confirmed this phenomenon in Table 1 and Figure 4.

Table 1.

Adjusted caloric fat percentage (E%) of African and non-African prey animals, based on [31] (Details of adjustments in [27]).

Figure 4.

Percent of fat content as a function of body weight in African herbivores. Based on [31]. Data in [27].

In the dataset, male herbivores weighing over 200 kg and female herbivores weighing over 150 kg contained, on average, 44% more body fat relative to body weight than smaller animals. Large African herbivores such as hippo, buffalo, and eland contain 55–70% fat, while smaller herbivores such as impala and gazelle contain 30–35% fat. This means that the smaller animals’ protein cannot be fully exploited unless plants or additional animals are acquired in which only the fat is consumed. In any event, to complete the obligatory fat requirement, a significant additional energetic expense is expected when the abundance of large animals declines.

Equally important, large herbivores lose less fat than smaller herbivores during periods of low forage. Thus, since humans mostly occupied seasonal environments, large animals became even more essential during low forage periods.

4.4. Larger Animals Provide a Higher Energetic Return

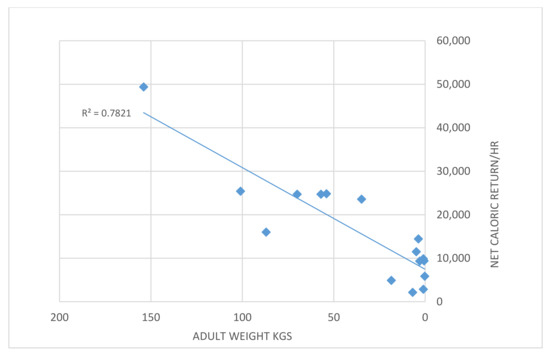

According to classic optimal foraging theory, an animal would specialize in the highest-ranking (highest energetic return) type if the encounter rate is high enough [32]. Data in [29] (Tables 3.3 and 3.4) show that medium-sized animals provide a net caloric return of 25–50,000 calories/hour compared to one-fifth to one-half of that in small animals (Figure 5); plant food returns are similar to those of very small animals. With such a difference in foraging efficiency, a decline in prey size also causes significant energetic pressure on humans.

Figure 5.

Net caloric return per hour as a function of prey size. Data in [27].

Opposition to the economic basis for large prey selection comes from the proponents of costly signaling as a choice criterion [33]. For example, based on data from the Hadza of Tanzania, Hawkes et al. [34] argued that the low hunting success rate and the need to share large prey prove that males hunt large game as a costly signal to attract mates. Wood and Marlowe [35], however, concluded, based on later data from the Hadza, that food economics rather than “show-off” signaling was at the base of the Hadza men’s hunting preferences. Other researchers of recent hunter-gatherer groups also found that economic considerations are paramount in large prey selection [36]. In an archaeological context, Dominguez-Rodrigo et al. [37] reached a similar conclusion regarding the supremacy of economic considerations in the selection of large prey, based on analysis of the Upper Bed II, Olduvai Gorge (BK4B) faunal assemblage.

4.5. Evidence for Specialization in Large Prey

In [4], we explored evidence for humans’ specialization in large prey acquisition, which is summarized in Table 2. All the references and detailed descriptions of the evidence can be found in the source paper.

Table 2.

Evidence for humans’ specialization in the acquisition of large prey during the Paleolithic.

5. Anthropogenic Contribution to Prey Size Decline

To the generally discussed arguments in support of anthropogenic prey-size decline, we would like to add the potential role of the need for fat to complete the non-protein portion of the diet in raising the risk for humans’ prey extinction. In addition to the biased selection for large prey discussed in Section 4.3., the need for fat can also be satisfied by selecting prime-adults and partial consumption of only the fatty body parts of the prey.

Preference for hunting prime-adult animals has been identified as beginning 400 Kya [38] and perhaps 800 Kya [39], or even 1.8 Mya [40]. This phenomenon, which is unique among predators [41], is also prevalent in Neandertals’ faunal assemblages throughout their wide-ranging habitat (e.g., [42,43,44]). Immature animals invest resources in growth at the expense of fat reserves [45]. Consequently, during most of the year, prime-adult animals will have a higher fat content than immature animals. Fat reserves also fluctuate differently between prime-adult males and females causing prime-adult females’ preference during about half of the year (see [46] (Figure 5) regarding caribou).

Biased transport of fatty parts, including marrow-baring bones, is a common phenomenon in faunal assemblages indicating partial exploitation of prey [47,48,49,50,51].

Large prey is relatively more susceptible to extinction than smaller animals because of their low fecundity [52], and herds rely on a stable component of prime-adults, especially that of prime-adult females, for population stability [53]. Partial exploitation is a normal phenomenon in other carnivores in time of plenty [54] but the need for fat for humans is greater in time of ecological stress because of probable concomitant plant resources’ scarcity, so it represents an increased risk for overhunting at times of stress for the prey populations [55]. To summarize this point, uniquely to humans, the need for fat increases the predation pressure on vulnerable prey populations and thus the risk for extirpation or extinction of their prey.

It should be noted that the actual extirpation or extinction of specific prey species may depend on a local co-occurrence of high human predation pressure and stochastic external ecological deleterious conditions. Thus, spatial and temporal differences in the expirations and extinctions of the various prey species are expected, and thus the timing of the appearance of the humans’ adaptations to the smaller prey species community.

6. The Decline in Prey Size as an Agent of Selection: Preliminary Case Studies

Given the significant difference in energetic return per hour between smaller and larger prey acquisition (Figure 5), human survival must have depended on adaptations that would mitigate the additional energetic cost of replacing the acquisition of extinct larger animals with smaller ones. Thus, we view the progressive decline in prey size as a selecting agent, and we view the progressivity of the adaptations as associated with that decline. We discuss several human biological, cultural, and behavioral transformations, and demonstrate how these might have been either dependent on large game availability or oriented toward mitigating the additional energetic cost of acquiring smaller prey during the Pleistocene.

6.1. Brain Size, Language, Stone-Tools, and Fire

The predominantly directional increase in brain size in the lineages leading to H. sapiens over more than two million years, during most of the Pleistocene (~2.6 Mya to ~0.3 Mya) and across several human species [56], is puzzling from an evolutionary theory point of view. A reversal of the growth trend at the end of the Pleistocene [57,58] also requires explanations. In present-day humans, larger cortical size is robustly associated with higher IQ [59]; a large brain relative to body mass has been shown to predict problem-solving ability in mammalian carnivores [60].

Increased social complexity was hypothesized to be the cognitive challenge that drove brain size growth [61]. Recently, however, ecological challenges, and in particular those related to foraging, have been proposed to better explain the need for brain expansion among primates [62,63,64,65,66,67]. A reduction in gut size, muscle mass, or redirection of energy from locomotion, growth, and reproduction may compensate for the increased energetic cost of a larger brain [65,68,69]. However, these compensations do not explain why a larger brain provided better fitness in the first place. Stanford and Bunn [70] proposed that the initial increase in the Homo brain size was driven by the need to develop hunting skills. Brain [71] attributed the brain size increase to the need to avoid predation; however, the question remains what drove the further ~50% increase in brain size from H. erectus to H. sapiens. Establishing the energetic pressure that the decline in prey size inflicted on humans, we propose that the expansion of various cognitive abilities met the ecological challenge of obtaining calories and fat from smaller prey at acceptable energetic costs. Brain expansion allowed humans to partly or wholly mitigate the potential additional energetic expenses on locomotion by tracking and linguistic communication of prey location, and facilitating economic smaller prey acquisition and exploitation by accumulating and transferring knowledge, and maintaining fire, and producing shaped and complex tools.

As indicated in several HG studies, movement on the landscape represents the largest discrete energetic expenditure of HG groups [72,73]. Therefore, tracking prey instead of relying on random encounters is a standard energy-saving behavior that could only have come about with an increase in cognitive skills, or the ability to deal with new information [74,75]. Blurton Jones and Konner [76] claimed that tracking is a cognitive process that mimics the scientific process, and used ethnographic research to argue that while tracking, hypotheses are formed and revised based on spoors’ information.

Liebenberg [77] describes two methods of tracking—systematic and speculative. Systematic trackers track successive spoors, a conceivably more efficient strategy for tracking larger animals because they naturally leave more conspicuous signs of their passage and do not flee (Figure 3). On the other hand, speculative trackers skip some potential spoors and proceed to where they speculate that the animal has headed, such as a water hole, an area of shade, or a food patch. Speculative tracking is more suitable for hunting smaller animals, which leave less conspicuous signs of their passage. Speculative tracking advances the hunter more rapidly on a shorter route and improves the tracking process’s energetic efficiency. Liebenberg [78] states that “Speculative tracking requires much experience. So, most trackers start as systematic trackers and only become speculative trackers once they have mastered the basic skills”. Additionally, the ability to identify fat-bearing animals, a critical ability when hunting smaller animals, also requires considerable experience and cognitive capacity [79] (pp. 42, 43).

Language is a large consumer of cognitive resources [80] and, hence, energy. We suggest that language increased fitness by facilitating energy savings in the face of prey size decline. Corballis [81] argues that language evolved in humans to communicate events “displaced in space and time from the present”. A significant amount of energy can be saved by the quick and accurate exchange of information by group members about prey’s recent sightings; information that could not be communicated appropriately without language.

Interestingly, bees use “dance language” to point to a food source that is not evenly distributed and displaced in space from where they are at the time [82]. In humans, the ability to also describe sighting time is essential as prey is more dynamic in the landscape than flower nectar. Additionally, language could help in the long-term retention and transfer of critical information concerning prey animals’ behavior and countless details regarding the nature of the world in which hunters operate, all of which help save energy during tracking and hunting. Much of the fireside conversation of hunters’ centers around natural phenomena and specific hunting experiences [76]. In summary, we propose that the evolution of a larger, energetically costly brain was driven to a significant extent by selection for energetic savings capabilities that secured smaller animals’ acquisition at acceptable energetic costs.

Several researchers have claimed that increased mental capabilities facilitated technological innovations, such as the Lower Paleolithic cleavers or later multi-component projectile tools during the Pleistocene (e.g., [83,84,85]), and were most probably oriented toward the acquisition and processing of large game. The bow and arrow, atlatl, and fluted points [86] may represent inventions that were already improved by the initial expansion in H. sapiens brain size. These hunting technologies were mostly employed to target relatively small animals [26,87,88]. Transformations in stone-tool technologies could also be related to cognitive developments triggered by the need to acquire smaller and smaller prey.

The control of fire has been hypothesized as the reason for brain expansion in H. erectus [89]; however, evidence for fire’s habitual use is much more common post-400 Kya (e.g., [90,91,92]. A central hearth that was continuously and intensively used is a prominent feature in the late Lower Paleolithic site of Qesem Cave, Israel (dated 420–200 Kya), where dental remains of post-H. erectus human lineage were discovered. Qesem Cave’s faunal assemblage is dominated by the ~100 kg fallow deer (Dama cf. mesopotamica) and is devoid of elephants, common in earlier Lower Paleolithic sites [93]. It was argued that fire for roasting and cooking was intended to utilize the smaller animals more efficiently and was critical to the inhabitants’ adaptation. The control of fire is considered part of a suite of innovative behaviors at Qesem Cave that demonstrate a new level of cognitive complexity, triggered by the disappearance of megaherbivores. One of these behaviors, the production of tiny sharp flint items utilizing lithic recycling to execute high-precision cutting tasks, was recently also associated with a new strategy for processing small game [94]. Moreover, the use of fire for roasting meat and extracting as many calories as possible from every food item continued progressively throughout the Paleolithic [95], correlating with the decline in prey size. Finally, sharing of smaller animals might have required a higher level of inhibitory control, another improved capability of a larger brain [67].

Neandertals also had a large brain, although they hunted large game alongside smaller animals. The comparison of cognitive abilities between Neandertals and H. sapiens is a subject of continuous research. There is little argument that Neandertals’ brain structure was different, to some extent, from H. sapiens (e.g., [96,97,98], suggesting different functionality, which is the expected result of evolution under different ecological conditions.

Our mechanistic explanation for the correlation between the pace of brain growth and a decline in prey size during the Pleistocene can benefit from further testing. Initial indications of such a correlation can be found in East Africa where “brain expansion, independent of body size, appears to be most strongly expressed later, between 800 and 200 thousand years ago” [99] (p. 10), roughly correlating with a decline in prey size during the East African Middle Pleistocene [6,8,9,100].

Associating brain size increase with the mitigation of extra energetic costs that come with the need to hunt smaller prey can also explain the decline in brain size at the end of the Paleolithic period and beyond [57,58]. In that period, plant consumption increased [2], culminating in the domestication of plants and animals. Plants and domesticated animals do not escape so their acquisition does not require the same degree of knowledge and decision making under time pressure as hunting small prey does hence the lower cognitive requirements.

6.2. Hunting of Large Animals by H. erectus (sensu lato)

We concentrate here on the H. erectus (sensu lato) of Africa only and treat the species as a general representative of pre-H. sapiens species; as in most cases, due to the lack of human fossils, it is impossible to assign specific faunal assemblages to distinct pre-H. sapiens species. Determining that H. erectus had a carnivorous trophic level (Section 3) and accounting for the protein constraint (Section 4.3), it follows that H. erectus was dependent on large animals to provide the obligatory fat requirements. Although not related to the decline in prey size, this test case can help us understand the persistence of a mode of adaptation based on large animals’ availability.

Recent analyses of the archeozoological and paleontological East African records portray H. erectus as a habitual hunter of large prey [101,102]. Preference for large prey animals during the Early Pleistocene is a conventional interpretation of archaeological assemblages [37,103,104,105]. Interestingly, Bunn and Gurtov [106] attribute to H. erectus a preference for prime-adult animal acquisition at FLK Zinji, 1.8 Mya. A similar preference is attributed by Bunn [107] to H. heidelbergensis in Elansfontain. Prime-adult animals always contain more fat than juveniles and older adults [45]; thus, it can be interpreted that this costly prey selection pattern was driven by a need for animal fat.

6.3. The Evolution of H. sapiens

The emergence of H. sapiens in Africa around 300 Kya [108] are contemporaneous with the onset of the Middle Stone Age mode of adaptation and, in East Africa, with the extinction of large-bodied grazing lineages and their replacement with related taxa of smaller body size [9]. Potts et al. [9] focused on the wet-dry climate variability, and the consequent need to cope with fluctuating resources as the drivers of changes at the onset of the MSA. However, we see carnivory specialization as a plausible solution to this and previous events of severe climate fluctuation [109]. Environmental variation can initiate specialization rather than flexibility in animals’ behavior to reduce the experienced variation [110], as a predator’s food sources are available in dry and wet conditions. Thus, the evolution of cognitive and cultural means of specializing in prey acquisition may be a viable and less costly solution to environmental variability than flexibility, which also has its costs [111]. In support, reviewing 1087 extant taxa from 28 phyla, Román-Palacios, Scholl, and Wiens [112] found that 63% are carnivores, and only 3% are omnivores. They state that their results “suggest that animals often specialize for carnivorous or herbivorous diet rather than being omnivores”.

Regarding mammals, analysis of a large (N = 139) dataset of mammals’ trophic levels [23] shows that 80% of the mammals in the dataset are omnivores, but most of the omnivores (75%) consume more than 70% of their food from either plants or animals, leaving only 20% of the mammals in the dataset to be omnivore-generalists. Interestingly, while all of the 16 primates in the dataset were omnivores, 15 of the 16 were specialists. According to this somewhat counterintuitive point of view, the decline in prey size identified by Potts et al. [9] might be the most significant phenomenon in the transition to the MSA. As mentioned, an identical phenomenon, the appearance of a new human lineage and a new cultural complex temporally coupled with the disappearance of the largest herbivore (the straight-tusked elephant), is evident in the Levant 400 Kya [10]. The emergence of H. Sapiens in Africa, a new, post-H. erectus lineage in the Levant, and the concomitant new cultures in both places may represent adaptations to the acquisition and processing of smaller animals. Many physiological and behavioral characteristics of H. Sapiens may also have been directed toward saving energy when hunting prey.

The increase in brain size as an adaptation towards efficient tracking and hunting of smaller game has already been discussed. Increased locomotive energetic efficiency may have been achieved by the lighter, agile body, which produced long lower limbs relative to bodyweight [113,114]. Increased mobility can be a response to environmental variability as purportedly experienced at the onset of the MSA. For many animals, increased mobility “can functionally decrease environmental variation, especially if movement is coupled with choice behavior” [110] (p. 149). Thus, in humans, increased locomotive efficiency may have partly mitigated the additional energetic expenditures associated with hunting a greater number of smaller prey animals. Better locomotive efficiency also leads to an improved endurance running capability when hunting smaller, fleeing animals. However, it is possible that despite the more efficient locomotion, H. sapiens still had to adapt to higher metabolic expenses when prey size declined. The substantially greater basal metabolic rate and total energetic expenditures of H. sapiens [115] may be, in part, an adaptation to the additional energetic expenses that were imposed on H. sapiens by the need to obtain energy and fat from smaller prey.

Some of the face gracilization features in H. sapiens [116] may have also been enabled by the decline in prey size. Neandertals’ robust frame has been attributed to the need to hunt large animals in close encounters [117], and it can be argued that a robust brow ridge is a part of this robusticity suite in pre-sapiens. Indeed, the reduced size of brow ridges in the Homo genus over time [116] could have been enabled by the decreased need to take down large animals at close encounters [26].

The habitual control of fire was discussed in the post-H. erectus context and applies to H. sapiens as well. It was also mentioned that the development of projectile technology by H. sapiens might have been intended for more energy-efficient hunting of smaller animals [26].

6.4. The Extinction of the Neandertal

Until recently, many researchers agreed that in Europe, the Neandertal diet had a narrow breadth and focused on larger prey [117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126]. A higher dietary plant content was postulated in more southern regions of the Neandertal’s presence, such as the Levant [127,128]. Further, MIS 3 (~59–24 Kya) was a cold period leading to the Glacial Maximum, and cold regions such as tundra and taiga experience long periods of minimal vegetation, so it is reasonable to assume that Neandertals were also exposed to long periods of minimal vegetation in MIS 3 Europe.

Several researchers published a reconstruction of the Neandertal diet [121,124,129,130]. Large and medium-sized herbivores dominate the Neandertal archaeological faunal record in Europe, including proboscideans and rhinoceroses [51,120,121,131].

Stable isotope research (e.g., [118,123,126,132,133,134,135] unilaterally supports a carnivorous profile for the Neandertal diet in western Europe (but see discussion and some reservations in [129]). However, small animals and birds were also consumed by Neandertals (e.g., [136]).

In recent years, evidence for consumption of plants and cooking has emerged, based on plant residues in Neandertal dental plaque taken from fossils in Europe and Asia [124,137,138,139]. A single study of five sediment samples of Neandertal coprolites from El Salt (Spain), around 50 Kya, found that Neandertals predominantly consumed meat but also had a significant plant intake [140].

The Neandertal became extinct during Marine Isotope Stage 3 [141] in parallel with Europe’s LQE [12]. Because of the Neandertal’s heavier bodyweight and the cold weather, Neandertal total energetic expenditure (TEE) was estimated to be significantly higher than that of H. sapiens (e.g., [142]). In our model, higher TEE leads to higher obligatory fat consumption, especially in very cold, snow-covered conditions, when the availability of plant food is limited. For this reason, the Neandertal was more dependent on large animals with a high-fat level [143] that lose less fat compared to smaller animals during periods of low primary production [144]. Thus, in agreement with Geist [145] and Stewart [146], we hypothesize that the decline in prey size in Europe during the LQE was a significant driver of Neandertal extinction. It should be noted that there are many other hypotheses that attempt to explain the Neandertals’ extinction. They cover cultural and other aspects of their complex way of living and some of them remain plausible and can co-exist side by side with ours.

6.5. Increased Plant Food Consumption from the Upper Paleolithic Onward

Although we know that plants were consumed, to some extent, whenever available (e.g., [147]), substantial archaeological evidence for increased plant consumption first appears in the Upper Paleolithic period [148,149,150,151,152]. The decreased availability of fat from large prey during the LQE may have led humans to develop technologies and behaviors that enabled them to obtain carbohydrates from plants as an alternative to animal fat, complementing their physiologically-limited protein consumption. Thus, we argue that the ubiquitous presence of plant food in post-Upper Paleolithic archaeological contexts is an effect of better preservation conditions and a reflection of the need to mitigate the energetic pressure and the reduction in fat availability due to the constant reduction in animal size.

6.6. Dog Domestication

Dogs were domesticated toward the end of the Pleistocene, during or after the LQE [153]. Since carnivores can utilize higher quantities of protein than humans [154], we agree with the hypothesis by Lahtinen et al. [155] that dog domestication was a form of “joint venture” between humans and wolves/dogs, in which humans contributed surplus meat protein from relatively fat-depleted animals that dogs could utilize but humans could not. In return, dogs helped humans save energy by helping to track and chase smaller animals. We add that in most ethnographic cases, dogs are employed to aid in hunting smaller animals [156,157]; thus, it is conceivable that dogs were domesticated as a behavioral adaptation to the increased energetic demands of hunting a larger number of smaller preys as prey size declined.

6.7. Plant and Animal Domestication at Different Times and Places

The continuing decline in the supply of animal fat during the Terminal Pleistocene may have led humans to domesticate plants and animals to secure an adequate supply of carbohydrates and fat to compensate for the ceiling on protein utilization. In the Levant, the small 25 kg Gazella gazella dominates the faunal assemblages of the Terminal Pleistocene, just before the Neolithic period and the Holocene, and large animals became negligible in comparison to previous periods [158,159]. A new pattern of hunting juvenile gazelles, which have a very low level of fat [45], then appeared [160]. Fat was extracted from gazelle bones [161], a possible nutritional stress marker [162] and, naturally, the cause for fat shortage. Local and global prey declines in the Late Paleolithic may explain domestication’s appearance at this time. It may also explain this phenomenon’s temporal variability and its independent appearance in different locations [163,164,165]. As previously stated, domestication and agriculture mark a clear departure from Paleolithic lifeways and must have necessitated a significant modification in work time, division of labor, and social structure and hierarchy. Thus, resource intensification following these transformations must have been triggered by a forceful mechanism. Moreover, because humans interacted with animals and plants for many millennia before the advent of agriculture, ancient ecological knowledge was most likely available long before it was applied as a direct result of the continuous decline in prey size.

7. Conclusions

Our unifying hypothesis suggests one driver for many key physiological and cultural phenomena in human prehistory—the decline in prey size. Any unifying hypothesis is broad in scope and takes many years of testing before presenting a full set of supporting evidence and is also bound to touch on many long-standing debates in paleoanthropology. Here, we provided preliminary support for our contention that humans were hypercarnivores during most of the Pleistocene, starting with H. erectus and ending just before the end of the Pleistocene, possibly in the Neolithic. While the decline in prey size itself is well-documented, its temporal and geographical association with each explained phenomenon was proposed here with thick brushstrokes and should be extensively tested.

It is important to note that our proposed unifying ecological agent of selection was likely accompanied by other local ecological agents of selection for each studied evolutionary and cultural phenomenon that require identification. While we posit that the reduction in prey size indeed triggered human adaptation, we also wish to emphasize that some of the changes were fostered by a profound acquaintance with the environment coupled with ancient ecological and technological knowledge. As humans interacted with animals, plants, fire, and stone for over 3 million years, they became aware of the potential of these elements and could use this knowledge to survive in adverse circumstances. Moreover, we wish to clarify that the view presented in this paper is not deterministic, because humans may have played a central role in the prey size reduction by hunting large and medium-size mammals for hundreds of thousands of years, possibly cutting the branch on which they were sitting. Thus, these changes were not forced upon early humans but may have been an unavoidable human action outcome.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.-D. and R.B.; methodology, M.B.-D. and R.B.; data curation, M.B.-D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.-D.; writing—review and editing, R.B.; visualization, M.B.-D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available at Mendeley Data http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/mmjfj488j3.2.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Maria Rita Polombo for the opportunity to participate in this special issue and to the editors and the reviewers for their wise and timely contribution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- MacColl, A.D. The ecological causes of evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2011, 26, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Dor, M.; Barkai, R. The importance of large prey animals during the Pleistocene and the implications of their extinction on the use of dietary ethnographic analogies. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2020, 59, 101192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Dor, M.; Barkai, R. Supersize does matter: The importance of large prey in Paleolithic subsistence and a method for measurement of its significance in zooarchaeological assemblages. In Human-Elephant Interactions: From Past to Present; Konidaris, G., Barkai, R., Tourloukis, V., Harvati, K., Eds.; Tübingen University Press: Tübingen, Germany, in press.

- Ben-Dor, M.; Sirtoli, R.; Barkai, R. The evolution of the human trophic level during the Pleistocene. Yb. Phys. Anthropol. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Faith, J.T.; Rowan, J.; Du, A. Early hominins evolved within non-analog ecosystems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 21478–21483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, F.A.; Smith, R.E.E.; Lyons, S.K.; Payne, J.L. Body size downgrading of mammals over the late Quaternary. Science 2018, 360, 310–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faith, J.T.; Rowan, J.; Du, A.; Barr, W.A. The uncertain case for human-driven extinctions prior to Homo sapiens. Quat. Res. 2020, 96, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faith, J.T.; Potts, R.; Plummer, T.W.; Bishop, L.C.; Marean, C.W.; Tryon, C.A. New perspectives on middle Pleistocene change in the large mammal faunas of East Africa: Damaliscus hypsodon sp. nov.(Mammalia, Artiodactyla) from Lainyamok, Kenya. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2012, 361, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, R.; Behrensmeyer, A.K.; Faith, J.T.; Tryon, C.A.; Brooks, A.S.; Yellen, J.E.; Deino, A.L.; Kinyanjui, R.; Clark, J.B.; Haradon, C.M. Environmental dynamics during the onset of the Middle Stone Age in eastern Africa. Science 2018, 360, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Dor, M.; Gopher, A.; Hershkovitz, I.; Barkai, R. Man the fat hunter: The demise of Homo erectus and the emergence of a new hominin lineage in the Middle Pleistocene (ca. 400 kyr) Levant. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembitzer, J.; Barkai, R.; Ben-Dor, M.; Meiri, S. 1.5 Million Years of Hunting Down the Body Size Distribution in the Paleolithic Southern Levant. Unpublished work. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, P.L.; Barnosky, A.D. Late Quaternary Extinctions: State of the Debate. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2006, 37, 215–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, N.L.; Zeder, M.A.; Fuller, D.Q.; Crowther, A.; Larson, G.; Erlandson, J.M.; Denham, T.; Petraglia, M.D. Ecological consequences of human niche construction: Examining long-term anthropogenic shaping of global species distributions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 6388–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandom, C.; Faurby, S.; Sandel, B.; Svenning, J.-C. Global late Quaternary megafauna extinctions linked to humans, not climate change. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 281, 20133254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, F.A.; Smith, R.E.E.; Lyons, S.K.; Payne, J.L.; Villaseñor, A. The accelerating influence of humans on mammalian macroecological patterns over the late Quaternary. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2019, 211, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirzo, R.; Young, H.S.; Galetti, M.; Ceballos, G.; Isaac, N.J.; Collen, B. Defaunation in the Anthropocene. Science 2014, 345, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodmer, R.E. Managing Amazonian wildlife: Biological correlates of game choice by detribalized hunters. Ecol. Appl. 1995, 5, 872–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerozolimski, A.; Peres, C.A. Bringing home the biggest bacon: A cross-site analysis of the structure of hunter-kill profiles in Neotropical forests. Biol. Conserv. 2003, 111, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andermann, T.; Faurby, S.; Turvey, S.T.; Antonelli, A.; Silvestro, D. The past and future human impact on mammalian diversity. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabb2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, D.J. Overkill, glacial history, and the extinction of North America’s Ice Age megafauna. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 28555–28563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendu, W.; Renou, S.; Soulier, M.-C.; Rigaud, S.; Roussel, M.; Soressi, M. Subsistence strategy changes during the Middle to Upper Paleolithic transition reveals specific adaptations of Human Populations to their environment. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, P. Ecosystem models and demographic hypotheses: Predation and prehistory in North America. In Models in Archaeology; Clark, D., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 543–576. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda-Munoz, S.; Alroy, J. Dietary characterization of terrestrial mammals. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 281, 20141173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempson, G.P.; Archibald, S.; Bond, W.J. A continent-wide assessment of the form and intensity of large mammal herbivory in Africa. Science 2015, 350, 1056–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agam, A.; Barkai, R. Elephant and mammoth hunting during the Paleolithic: A Review of the relevant archaeological, ethnographic and ethno-historical records. Quaternary 2018, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, S.E. Weapon technology, prey size selection, and hunting methods in modern hunter-gatherers: Implications for hunting in the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic. Archeol. Pap. Am. Anthropol. Assoc. 1993, 4, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Dor, M. Data file—Supersize does matter. The importance of large prey in Paleolithic subsistence and a method for measuring its significance in zooarchaeological assemblages. Mendeley Data 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speth, J.D.; Spielmann, K.A. Energy source, protein metabolism, and hunter-gatherer subsistence strategies. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 1983, 2, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.L. The Lifeways of Hunter-Gatherers: The Foraging Spectrum; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pitts, G.C.; Bullard, T.R. Some interspecific aspects of body composition in mammals. In Body Composition in Animals and Man; National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 1967; pp. 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ledger, H.P. Body composition as a basis for a comparative study of some East African mammals. Symp. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1968, 21, 289–310. [Google Scholar]

- Futuyma, D.J.; Moreno, G. The evolution of ecological specialization. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1988, 19, 207–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speth, J.D. Big-Game Hunting: Protein, Fat, or Politics. In The Paleoanthropology and Archaeology of Big-Game Hunting; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 149–161. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, K.; O’Connell, J.F.; Blurton Jones, N.G.; Bell, D.; Bird, R.; Bird, D.; Hames, R.; Ivey, P.; Judge, D.; Kazankov, A. Hunting and nuclear families: Some lessons from the Hadza about mens work. Curr. Anthropol. 2001, 42, 681–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, B.M.; Marlowe, F.W. Household and kin provisioning by Hadza men. Hum. Nat. 2013, 24, 280–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurven, M.; Hill, K. Hunting as subsistence and mating effort? A re-evaluation of “Man the Hunter”, the sexual division of labor and the evolution of the nuclear family. In Proceedings of IUSSP Seminar on Male Life History; University of California: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Rodrigo, M.; Bunn, H.T.; Mabulla, A.Z.P.; Baquedano, E.; Uribelarrea, D.; Perez-Gonzalez, A.; Gidna, A.; Yravedra, J.; Diez-Martin, F.; Egeland, C.P.; et al. On meat eating and human evolution: A taphonomic analysis of BK4b (Upper Bed II, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania), and its bearing on hominin megafaunal consumption. Quat. Int. 2014, 322, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiner, M.C.; Gopher, A.; Barkai, R. Hearth-side socioeconomics, hunting and paleoecology during the late Lower Paleolithic at Qesem Cave, Israel. J. Hum. Evol. 2011, 60, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladié, P.; Huguet, R.; Díez, C.; Rodríguez-Hidalgo, A.; Cáceres, I.; Vallverdú, J.; Rosell, J.; de Castro, J.M.B.; Carbonell, E. Carcass transport decisions in Homo antecessor subsistence strategies. J. Hum. Evol. 2011, 61, 425–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, H.T.; Pickering, T.R. Bovid mortality profiles in paleoecological context falsify hypotheses of endurance running–hunting and passive scavenging by early Pleistocene hominins. Quat. Res. 2010, 74, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiner, M.C. The use of mortality patterns in archaeological studies of hominid predatory adaptations. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 1990, 9, 305–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castel, J.-C.; Discamps, E.; Soulier, M.-C.; Sandgathe, D.; Dibble, H.L.; McPherron, S.J.; Goldberg, P.; Turq, A. Neandertal subsistence strategies during the Quina Mousterian at Roc de Marsal (France). Quat. Int. 2016, 433, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, D. Ahead of the game. Curr. Anthropol. 2006, 47, 89–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudzinski, S.; Roebroeks, W. Adults only. Reindeer hunting at the Middle Palaeolithic site Salzgitter Lebenstedt, Northern Germany. J. Hum. Evol. 2000, 38, 497–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen-Smith, R.N. Adaptive Herbivore Ecology: From Resources to Populations in Variable Environments; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cordain, L.; Eaton, S.B.; Sebastian, A.; Mann, N.; Lindeberg, S.; Watkins, B.A.; O’Keefe, J.H.; Brand-Miller, J. Origins and evolution of the Western diet: Health implications for the 21st century. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speth, J.D. Bison Kills and Bone Counts: Decision Making by Ancient Hunters; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Binford, L.R. Nunamiut Ethnoarchaeology; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, E. Fat composition and Nunamiut decision-making: A new look at the marrow and bone grease indices. JAS 2007, 34, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Oz, G.; Munro, N.D. Gazelle bone marrow yields and Epipalaeolithic carcass exploitation strategies in the southern Levant. JAS 2007, 34, 946–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiner, M.C. An Unshakable Middle Paleolithic? Trends versus Conservatism in the Predatory Niche and Their Social Ramifications. Curr. Anthropol. 2013, 54, S288–S304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, M.L. Extinction vulnerability and selectivity: Combining ecological and paleontological views. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1997, 28, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, J.-M.; Festa-Bianchet, M.; Yoccoz, N.; Loison, A.; Toigo, C. Temporal variation in fitness components and population dynamics of large herbivores. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2000, 31, 367–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, A.E.; Quinn, T.P. Optimal foraging or surplus killing: Selective consumption and discarding of salmon by brown bears. Behav. Ecol. 2019, 30, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speth, J.D.; Clark, J.L. Hunting and overhunting in the Levantine Late Middle Palaeolithic. Before Farm. 2006, 2006, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Wolpoff, M.H. The pattern of evolution in Pleistocene human brain size. Paleobiology 2003, 29, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawks, J. Selection for smaller brains in Holocene human evolution. arXiv preprint 2011, arXiv:1102.5604. [Google Scholar]

- Henneberg, M. Decrease of human skull size in the Holocene. Hum. Biol. 1988, 60, 395–405. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon, P.; Seidlitz, J.; Vandekar, S.; Liu, S.; Patel, R.; Park, M.T.M.; Alexander-Bloch, A.; Clasen, L.S.; Blumenthal, J.D.; Lalonde, F.M. Normative brain size variation and brain shape diversity in humans. Science 2018, 360, 1222–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson-Amram, S.; Dantzer, B.; Stricker, G.; Swanson, E.M.; Holekamp, K.E. Brain size predicts problem-solving ability in mammalian carnivores. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 2532–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, R. The social brain hypothesis. Evol. Anthropol. Issues News Rev. 1998, 6, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burini, R.C.; Leonard, W.R. The evolutionary roles of nutrition selection and dietary quality in the human brain size and encephalization. Nutrire 2018, 43, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCasien, A.R.; Williams, S.A.; Higham, J.P. Primate brain size is predicted by diet but not sociality. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 0112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Forero, M.; Gardner, A. Inference of ecological and social drivers of human brain-size evolution. Nature 2018, 557, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, W.R.; Snodgrass, J.J.; Robertson, M.L. Effects of brain evolution on human nutrition and metabolism. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2007, 27, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, L.E.; Isler, K.; Barton, R.A. Re-evaluating the link between brain size and behavioural ecology in primates. Proc. R. Soc. B 2017, 284, 20171765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosati, A.G. Foraging cognition: Reviving the ecological intelligence hypothesis. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2017, 21, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, L.C.; Wheeler, P. The expensive-tissue hypothesis: The brain and the digestive system in human and primate evolution. Curr. Anthropol. 1995, 36, 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, A.; Schaik, C.P.V.; Isler, K. Energetics and the evolution of human brain size. Nature 2011, 480, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, C.B.; Bunn, H.T. Meat-Eating & Human Evolution; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brain, C.K. Do we owe our intelligence to a predatory past? James Arthur Lect. Evol. Hum. Brain 2000, 70, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, S.E.; Walker, C.S.; Schwartz, A.M. Home-range size in large-bodied carnivores as a model for predicting neandertal territory size. Evol. Anthropol. Issues News Rev. 2016, 25, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontzer, H. Constrained total energy expenditure and the evolutionary biology of energy balance. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2015, 43, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flinn, M.V.; Geary, D.C.; Ward, C.V. Ecological dominance, social competition, and coalitionary arms races: Why humans evolved extraordinary intelligence. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2005, 26, 10–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geary, D.C. Evolution and cognitive development. In Evolutionary Perspectives on Human Development; Burgess, R.L., MacDonald, K., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Blurton Jones, N.; Konner, M.J. Kung knowledge of animal behavior. In Kalahari Hunter-Gatherers; Lee, B.R., DeVore, I., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1976; pp. 325–348. [Google Scholar]

- Liebenberg, L. Persistence hunting by modern hunter-gatherers. Curr. Anthropol. 2006, 47, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebenberg, L. The Origin of Science—The Evolutionary Roots of Scientific Reasoning and Its Implications for Citizen Science; CyberTracker: Cape Town, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brink, J. Imagining Head-Smashed-in Aboriginal Buffalo Hunting on the Northern Plains; Athabasca University Press: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, I. Cognitive evolution and origins of language and speech. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology; Smith, C., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1530–1543. [Google Scholar]

- Corballis, M.C. The gradual evolution of language. HUMANA MENTE J. Philos. Stud. 2014, 7, 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Dornhaus, A.; Chittka, L. Why do honey bees dance? Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2004, 55, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzlinger, G.; Wynn, T.; Goren-Inbar, N. Expert cognition in the production sequence of Acheulian cleavers at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov, Israel: A lithic and cognitive analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putt, S.S. Human Brain Activity During Stone Tool Production: Tracing the Evolution of Cognition and Language; The University of Iowa: Iowa City, IA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vaesen, K. The cognitive bases of human tool use. Behav. Brain Sci. 2012, 35, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.L.; Goebel, T. Origins and spread of fluted-point technology in the Canadian Ice-Free Corridor and eastern Beringia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4116–4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gärdenfors, P.; Lombard, M. Causal cognition, force dynamics and early hunting technologies. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiner, M.C.; Kuhn, S.L. Changes in the “Connectedness” and resilience of paleolithic societies in Mediterranean ecosystems. Hum. Ecol. 2006, 34, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrangham, R. Control of Fire in the Paleolithic Evaluating the Cooking Hypothesis. Curr. Anthropol. 2017, 58, S303–S313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowlett, J. The discovery of fire by humans: A long and convoluted process. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20150164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimelmitz, R.; Kuhn, S.L.; Jelinek, A.J.; Ronen, A.; Clark, A.E.; Weinstein-Evron, M. ‘Fire at will’: The emergence of habitual fire use 350,000 years ago. J. Hum. Evol. 2014, 77, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roebroeks, W.; Villa, P. On the earliest evidence for habitual use of fire in Europe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 5209–5214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkai, R.; Blasco, R.; Rosell, J.; Gopher, A. A land of flint and fallow deer: Human persistence at Middle Pleistocene Qesem Cave. In Crossing the Human Threshold; Pope, M., McNabb, J., Gamble, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 82–104. [Google Scholar]

- Venditti, F.; Cristiani, E.; Nunziante-Cesaro, S.; Agam, A.; Lemorini, C.; Barkai, R. Animal residues found on tiny Lower Paleolithic tools reveal their use in butchery. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkai, R.; Rosell, J.; Blasco, R.; Gopher, A. Fire for a reason: Barbecue at Middle Pleistocene Qesem Cave, Israel. Curr. Anthropol. 2017, 58, S314–S328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, E.; Stringer, C.; Dunbar, R.I. New insights into differences in brain organization between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 20130168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, T.; Overmann, K.A.; Coolidge, F.L. The false dichotomy: A refutation of the Neandertal indistinguishability claim. J. Anthropol. Sci. 2016, 94, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lombard, M.; Högberg, A. Four-field co-evolutionary model for human cognition: Variation in the Middle Stone Age/Middle Palaeolithic. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 2021, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Antón, S.C.; Potts, R.; Aiello, L.C. Evolution of early Homo: An integrated biological perspective. Science 2014, 345, 1236828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, R.B.; Muiruri, V.M.; Lowenstein, T.K.; Renaut, R.W.; Rabideaux, N.; Luo, S.; Deino, A.L.; Sier, M.J.; Dupont-Nivet, G.; McNulty, E.P. Progressive aridification in East Africa over the last half million years and implications for human evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 11174–11179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-Rodrigo, M.; Pickering, T.R. The meat of the matter: An evolutionary perspective on human carnivory. Azania Archaeol. Res. Afr. 2017, 52, 4–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, N.T.; Du, A.; Hatala, K.G.; Ostrofsky, K.R.; Reeves, J.S.; Braun, D.R.; Harris, J.W.; Behrensmeyer, A.K.; Richmond, B.G. Pleistocene animal communities of a 1.5 million-year-old lake margin grassland and their relationship to Homo erectus paleoecology. J. Hum. Evol. 2018, 122, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, H.T.; Ezzo, J.A. Hunting and scavenging by Plio-Pleistocene hominids: Nutritional constraints, archaeological patterns, and behavioural implications. JAS 1993, 20, 365–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, G.L. The archaeology of human origins: Studies of the Lower Pleistocene in East Africa, 1971–1981. Adv. World Archaeol. 1984, 3, 1–86. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, R.G. The archaeological significance of animal bones from Acheulean sites in southern Africa. Afr. Archaeol. Rev. 1988, 6, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, H.T.; Gurtov, A.N. Prey mortality profiles indicate that Early Pleistocene Homo at Olduvai was an ambush predator. Quat. Int. 2014, 322, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, H.T. Large ungulate mortality profiles and ambush hunting by Acheulean-age hominins at Elandsfontein, Western Cape Province, South Africa. JAS 2019, 107, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hublin, J.-J.; Ben-Ncer, A.; Bailey, S.E.; Freidline, S.E.; Neubauer, S.; Skinner, M.M.; Bergmann, I.; Le Cabec, A.; Benazzi, S.; Harvati, K. New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens. Nature 2017, 546, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potts, R. Variability selection in hominid evolution. Evol. Anthropol. Issues News Rev. 1998, 7, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell-Rood, E.C.; Steck, M.K. Behaviour shapes environmental variation and selection on learning and plasticity: Review of mechanisms and implications. Anim. Behav. 2019, 147, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, R.J.; Donelson, J.M.; Schunter, C.; Ravasi, T.; Gaitán-Espitia, J.D. Beyond buying time: The role of plasticity in phenotypic adaptation to rapid environmental change. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Palacios, C.; Scholl, J.P.; Wiens, J.J. Evolution of diet across the animal tree of life. Evol. Lett. 2019, 3, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHenry, H.M. Body size and proportions in early hominids. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1992, 87, 407–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steudel-Numbers, K.L.; Tilkens, M.J. The effect of lower limb length on the energetic cost of locomotion: Implications for fossil hominins. J. Hum. Evol. 2004, 47, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontzer, H.; Brown, M.H.; Raichlen, D.A.; Dunsworth, H.; Hare, B.; Walker, K.; Luke, A.; Dugas, L.R.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.; Schoeller, D. Metabolic acceleration and the evolution of human brain size and life history. Nature 2016, 533, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacruz, R.; Stringer, C.; Kimble, W.; Wood, B.; Harvati, K.; O’Higgins, P.; Arsuaga, J.-L. The evolutionary history of the human face. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.H. The fate of the neandertals. J. Anthropol. Res. 2013, 69, 167–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocherens, H. Neanderthal dietary habits: Review of the isotopic evidence. In Evolution of Hominin Diets: Integrating Approaches to the Study Paleolithic Subsistence; Hublin, J.J., Richards, M.P., Eds.; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, S.E. Thin on the Ground: Neandertal Biology, Archeology and Ecology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudzinski, S. Monospecific or species-dominated faunal assemblages during the Middle Paleolithic in Europe. In Transitions before the Transition: Evolution and Stability in the Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age; Hovers, E., Kuhn, S., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Hockett, B.; Haws, J.A. Nutritional ecology and the human demography of Neandertal extinction. Quat. Int. 2005, 137, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, J.F. How did modern humans displace Neanderthals? Insights from hunter-gatherer ethnography and archaeology. In When Neanderthals and Modern Humans Met; Conard, N.J., Ed.; Kerns Verlag: Tübingen, Germany, 2006; pp. 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, M.P.; Trinkaus, E. Isotopic evidence for the diets of European Neanderthals and early modern humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 16034–16039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Garcia, D.C.; Power, R.C.; Serra, A.S.; Villaverde, V.; Walker, M.J.; Henry, A.G. Neanderthal diets in central and southeastern Mediterranean Iberia. Quat. Int. 2013, 318, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, P.; Roebroeks, W. Neandertal Demise: An Archaeological Analysis of the Modern Human Superiority Complex. PLoS ONE 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissing, C.; Rougier, H.; Crevecoeur, I.; Germonpré, M.; Naito, Y.I.; Semal, P.; Bocherens, H. Isotopic evidence for dietary ecology of Late Neandertals in North-Western Europe. Quat. Int. 2015, 10, 327–345. [Google Scholar]

- Lev, E.; Kislev, M.E.; Bar-Yosef, O. Mousterian vegetal food in Kebara Cave, Mt. Carmel. JAS 2005, 32, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madella, M.; Jones, M.K.; Goldberg, P.; Goren, Y.; Hovers, E. The exploitation of plant resources by Neanderthals in Amud Cave (Israel): The evidence from Phytolith studies. JAS 2002, 29, 703–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorenza, L.; Benazzi, S.; Henry, A.G.; Salazar-Garcia, D.C.; Blasco, R.; Picin, A.; Wroe, S.; Kullmer, O. To Meat or Not to Meat? New Perspectives on Neanderthal Ecology. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2015, 156, 43–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudzinski-Windheuser, S.; Niven, L. Hominin Subsistence Patterns During the Middle and Late Paleolithic in Northwestern Europe. In Evolution of Hominin Diets: Integrating Approaches to the Study of Palaeolithic Subsistence; Hublin, J.J., Richards, M.P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panera, J.; Rubio-Jara, S.; Yravedra, J.; Blain, H.-A.; Sese, C.; Perez-Gonzalez, A. Manzanares Valley (Madrid, Spain): A good country for Proboscideans and Neanderthals. Quat. Int. 2014, 326, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocherens, H. Diet and Ecology of Neanderthals: Implications from C and N Isotopes. In Neanderthal Lifeways, Subsistence and Technology: One Hundred Fifty Years of Neanderthal Study; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocherens, H.; Drucker, D.G.; Billiou, D.; Patou-Mathis, M.; Vandermeersch, B. Isotopic evidence for diet and subsistence pattern of the Saint-Césaire I Neanderthal: Review and use of a multi-source mixing model. J. Hum. Evol. 2005, 49, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocherens, H.; Drucker, D.G. Dietary competition between Neanderthals and modern humans: Insights from stable isotopes. In When Neanderthals and Modern Humans Met; Conard, N.J., Ed.; Kerns Verlag: Tübingen, Germany, 2006; pp. 129–143. [Google Scholar]

- Naito, Y.I.; Chikaraishi, Y.; Drucker, D.G.; Ohkouchi, N.; Semal, P.; Wißing, C.; Bocherens, H. Ecological niche of Neanderthals from Spy Cave revealed by nitrogen isotopes of individual amino acids in collagen. J. Hum. Evol. 2016, 93, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasco, R.; Fernández Peris, J. A uniquely broad spectrum diet during the Middle Pleistocene at Bolomor Cave (Valencia, Spain). Quat. Int. 2012, 252, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, K.; Buckley, S.; Collins, M.J.; Estalrrich, A.; Brothwell, D.; Copeland, L.; García-Tabernero, A.; García-Vargas, S.; de la Rasilla, M.; Lalueza-Fox, C.; et al. Neanderthal medics? Evidence for food, cooking, and medicinal plants entrapped in dental calculus. Naturwissenschaften 2012, 99, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, A.G.; Brooks, A.S.; Piperno, D.R. Plant foods and the dietary ecology of Neanderthals and early modern humans. J. Hum. Evol. 2014, 69, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weyrich, L.S.; Duchene, S.; Soubrier, J.; Arriola, L.; Llamas, B.; Breen, J.; Morris, A.G.; Alt, K.W.; Caramelli, D.; Dresely, V. Neanderthal behaviour, diet, and disease inferred from ancient DNA in dental calculus. Nature 2017, 544, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sistiaga, A.; Mallol, C.; Galvan, B.; Everett Summons, R. The Neanderthal Meal: A New Perspective Using Faecal Biomarkers. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, T.; Douka, K.; Wood, R.; Ramsey, C.B.; Brock, F.; Basell, L.; Camps, M.; Arrizabalaga, A.; Baena, J.; Barroso-Ruiz, C.; et al. The timing and spatiotemporal patterning of Neanderthal disappearance. Nature 2014, 512, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehle, A.W.; Churchill, S.E. Energetic Competition Between Neandertals and Anatomically Modern Humans. Paleo Anthropol. 2009, 96, 116. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Dor, M.; Gopher, A.; Barkai, R. Neandertals’ large lower thorax may represent adaptation to high protein diet. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2016, 160, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstedt, S.L.; Boyce, M.S. Seasonality, fasting, endurance, and body size in mammals. Am. Nat. 1985, 125, 873–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geist, V. Neanderthal the hunter. Nat. Hist. 1981, 90, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, J.R. Neanderthal extinction as part of the faunal change in Europe during Oxygen Isotope Stage 3. Acta Zool. Cracoviensia Ser. A Vertebr. 2007, 50A, 93–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larbey, C.; Mentzer, S.M.; Ligouis, B.; Wurz, S.; Jones, M.K. Cooked starchy food in hearths ca. 120 kya and 65 kya (MIS 5e and MIS 4) from Klasies River Cave, South Africa. J. Hum. Evol. 2019, 131, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranguren, B.; Becattini, R.; Lippi, M.M.; Revedin, A. Grinding flour in Upper Palaeolithic Europe (25000 years bp). Antiquity 2007, 81, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Yosef, O. Upper Paleolithic hunter-gatherers in Western Asia. In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Hunter-Gatherers; Cummings, V., Jordan, P., Zvelebil, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 252–278. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, S.L.; Stiner, M.C. The antiquity of hunter-gatherers. In Hunter–Gatherers: Interdisciplinary Perspectives; Panter-Brick, C., Layton, R., Rowley-Conwy, P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; pp. 99–142. [Google Scholar]

- Revedin, A.; Aranguren, B.; Becattini, R.; Longo, L.; Marconi, E.; Lippi, M.M.; Skakun, N.; Sinitsyn, A.; Spiridonova, E.; Svoboda, J. Thirty thousand-year-old evidence of plant food processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 18815–18819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soffer, O. Storage, sedentism and the Eurasian Palaeolithic record. Antiquity 1989, 63, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germonpré, M.; Sablin, M.V.; Lázničková-Galetová, M.; Després, V.; Stevens, R.E.; Stiller, M.; Hofreiter, M. Palaeolithic dogs and Pleistocene wolves revisited: A reply to Morey (2014). JAS 2015, 54, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, M.L.; Rogers, Q.R.; Morris, J.G. Nutrition of the domestic cat, a mammalian carnivore. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1984, 4, 521–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahtinen, M.; Clinnick, D.; Mannermaa, K.; Salonen, J.S.; Viranta, S. Excess protein enabled dog domestication during severe Ice Age winters. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupo, K.D. When and where do dogs improve hunting productivity? The empirical record and some implications for early Upper Paleolithic prey acquisition. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2017, 47, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeomans, L.; Martin, L.; Richter, T. Close companions: Early evidence for dogs in northeast Jordan and the potential impact of new hunting methods. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2019, 53, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, N.; BarOz, G.; Dayan, T.; Broughton, J.; Ugan, A.; Davis, S.; Hayden, B.; Jones, E.; Lyman, R.L.; Valla, F. Zooarchaeological measures of hunting pressure and occupation intensity in the Natufian: Implications for agricultural origins. Curr. Anthropol. 2004, 45, S5–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, N.D.; Bar-Oz, G.; Meier, J.S.; Sapir-Hen, L.; Stiner, M.C.; Yeshurun, R. The emergence of animal management in the Southern Levant. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.J. Why domesticate food animals? Some zoo-archaeological evidence from the Levant. JAS 2005, 32, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, N.D.; Bar-Oz, G. Gazelle bone fat processing in the Levantine Epipalaeolithic. JAS 2005, 32, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outram, A.K. Identifying dietary stress in marginal environments: Bone fats, optimal foraging theory and the seasonal round. In Colonisation, Migration and Marginal Areas: A Zooarchaeological Approach; Miondini, M., Munoz, S., Wickler, S., Eds.; Oxford Books: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Yosef, O. Multiple origins of agriculture in Eurasia and Africa. In On Human Nature: Biology, Psychology, Ethics, Politics, and Religion; Tibayrenc, M., Francisco, J.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 297–331. [Google Scholar]

- Price, T.D.; Bar-Yosef, O. The origins of agriculture: New data, new ideas: An introduction to supplement 4. Curr. Anthropol. 2011, 52, S163–S174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigne, J.-D. The origins of animal domestication and husbandry: A major change in the history of humanity and the biosphere. C. R. Biol. 2011, 334, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).