1. Introduction

SCP is a procedure performed to remove the urinary bladder and prostate in patients for whom definitive therapy for localised bladder and prostate cancer has failed. SCPs are technically challenging procedures and are not without complications. One of the primary concerns is the occurrence of rectal injury, with reported incidence rates ranging from 1% to 10% [

1,

2,

3].

Pelvic irradiation for prostate cancer treatment can induce acute proctitis and may subsequently lead to a progressive inflammatory–fibrotic condition and radiation-induced desmoplastic adhesions [

2]. This makes creating a safe plane of dissection between the anterior rectal wall and prostate during SCP difficult, leaving the rectum more susceptible to injury. Rectal spacers have been used increasingly in the field of radiation oncology. Due to the anatomical proximity of the two structures, it is highly susceptible to rectal side effects such as loose stools, reduced quality of life (QoL) and rectal injury [

4]. As such, rectal spacers are inserted anterior to the rectal wall to reduce the radiation dose to the rectum [

5,

6].

New HA-based rectal spacers have been used in prostate cancer treatment outside of radiation therapy [

1]. The main aim of HA rectal spacer infiltration before surgery is to create a temporary displacement of the rectum away from the prostate, lowering the risk of rectal injury intraoperatively. However, HA rectal spacers have not been used in SCP previously. We present a patient with a new diagnosis of muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) who was planned for SCP. He had an HA rectal spacer injected into the Denonvilliers’ space two weeks before surgery. This is the first known case of the use of HA rectal spacers for rectal protection in an SCP.

2. Case Presentation

A male patient in his late 70s was referred to our urology clinic for investigation of iron deficiency anaemia and macroscopic haematuria with associated clot retention. The patient has a background of stage IIB (cT2b, cN0, cM0, Grade Group 2) prostate cancer 10 years ago, managed with external beam radiotherapy. He underwent multiple rigid cystoscopies for bladder clot evacuation, which showed only mild radiation changes, with no obvious bladder tumour. CT IVP at the time did not demonstrate any hydroureteronephrosis or filling defect. Urine cytology was negative for malignancy, with one specimen demonstrating atypical cells. Macroscopic haematuria was resolved with two instillations of intravesical prostaglandin, and anaemia was managed with blood transfusions.

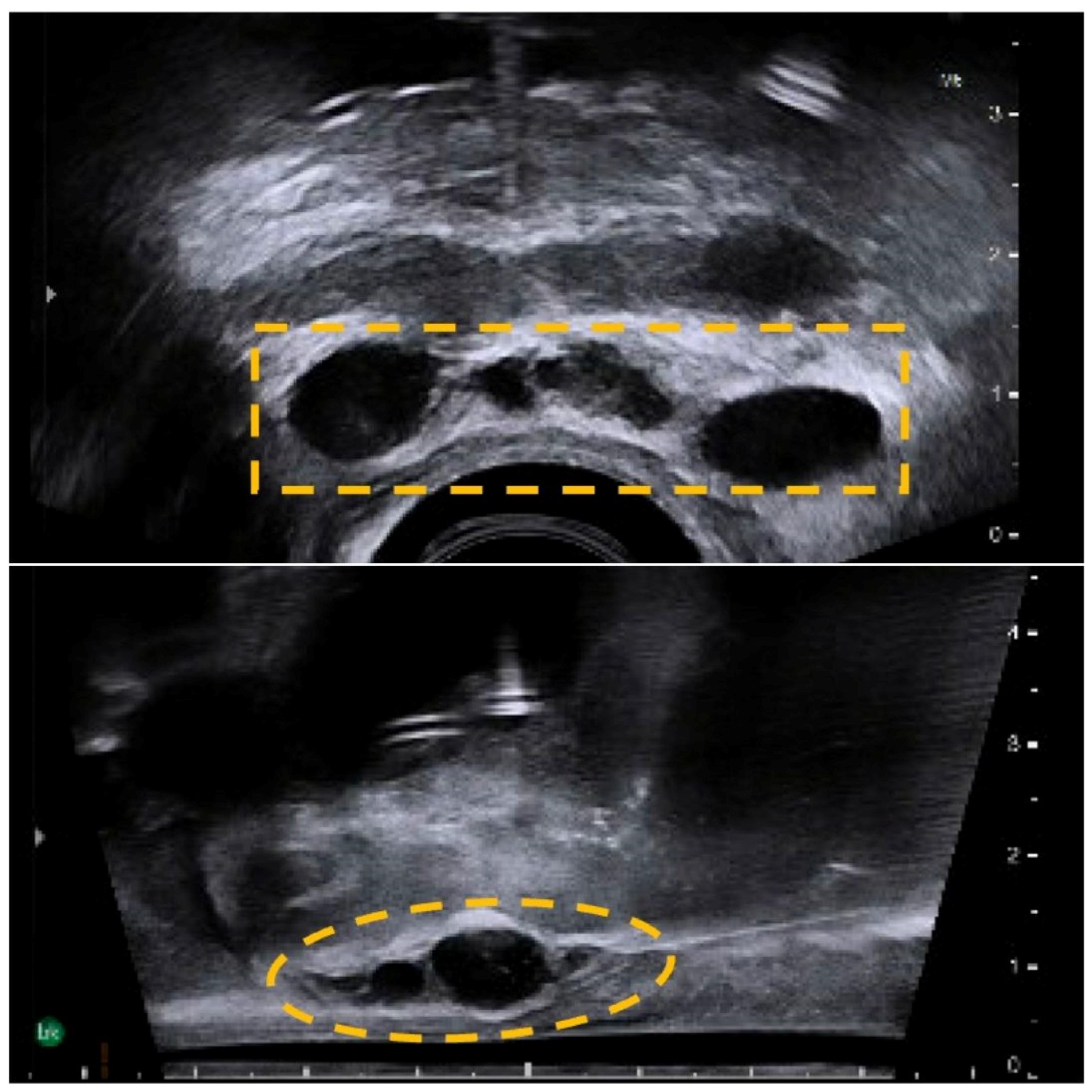

An interval CT KUB performed three months after showed new acalculous bilateral mild hydroureteronephrosis with apparent eccentric irregular thickening of the superior urinary bladder wall, suggestive of urinary bladder neoplasm. This was confirmed on histology (TURBT) as a pT2 muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). Post-multidisciplinary team discussion, the decision was made to perform an SCP with HA rectal spacer infiltration into the Denonvilliers’ space two weeks prior, for rectal protection. The HA rectal spacer was injected into the perirectal fat under sagittal TRUS guidance using a midline 18G needle inserted transperineally, which showed good separation of the perirectal tissue at the base and mid-gland of the prostate (

Figure 1).

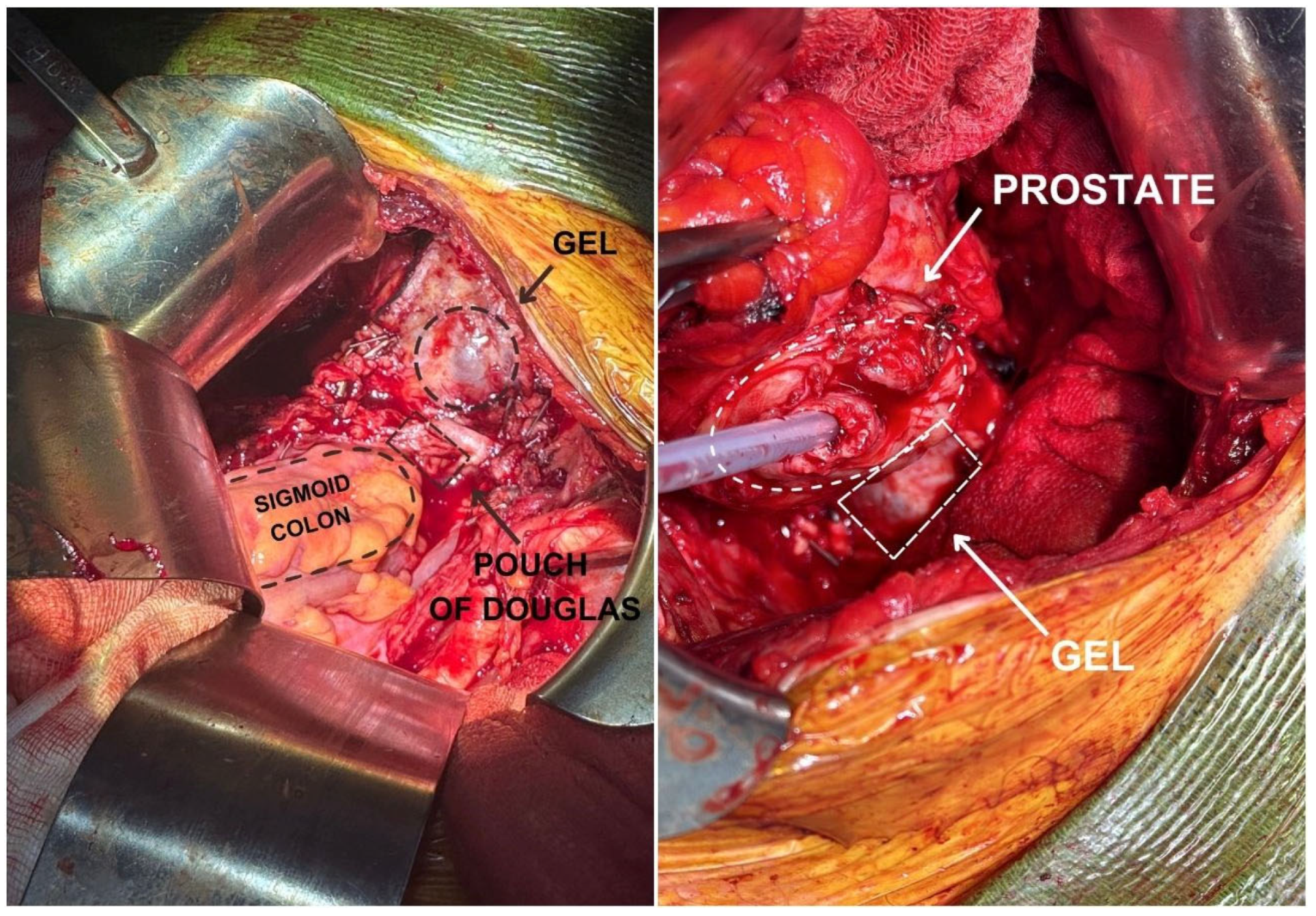

Intraoperatively, intrafascial dissection of the posterior prostate gland was performed, and the position of the rectal spacer was noted as a cystic structure anterior to the rectum (

Figure 2). This guided the dissection of the prostate while ensuring the protection of the rectum. The patient did not experience any symptoms related to rectal injury and had full bowel continence postoperatively. At 3 months after SCP, the patient was readmitted for antegrade stenting due to bilateral distal ureteric strictures with positive margins. The patient had full bowel continence and normal bowel motion. The patient was closely followed up by the oncology team and was planned for systemic therapy. However, the patient’s condition deteriorated, and he passed away at 4 months postoperatively due to early liver metastasis and failure to thrive. While we cannot comment on the long-term effects of hyaluronic acid rectal spacers in this context, this case is proof of concept that HA rectal spacers can make surgery technically easier and ensure GI-related quality of life.

3. Discussion

Surgical resection post-pelvic radiotherapy is associated with more complex resection and higher surgical morbidity [

1]. Tissue adhesion between the rectum and the prostate due to radiotherapy scarring increases the risk of rectal injury from 0.5% in primary prostatectomy to 6.9% during prostatectomy in an irradiated pelvis [

1] and 9.6% in radical cystectomy to 27% in patients undergoing radical cystectomy with previous pelvic radiation [

7]. As such, HA rectal spacers may emerge as a valuable tool in providing rectal protection during surgical procedures, particularly in cases where the rectum is at risk of injury. Our case highlights the feasibility of using an HA rectal spacer in an SCP for rectal protection. HA is a polysaccharide found in human tissues as a component of the connective tissue [

5] and was first approved for use as a cosmetic filler in 2003. In 2007, Prada et al. performed the first study looking into the use of HA perirectal spacers to reduce rectal toxicity from radiation for prostate cancer patients [

6].

Prior to the advent of HA rectal spacers, hydrogels and balloon spacers were the mainstay rectal spacers used to reduce the radiation dose to the rectum in prostate cancer treatment. However, balloon spacers have been associated with rectal perforation [

8]. Hydrogel spacers are non-reversible if inadvertently infiltrated into an incorrect target area and are also known to cause rectal wall erosions and recto-urethral fistulas [

9]. The main advantage of using HA as a rectal spacer is that it is reversible with hyaluronidase [

10] and fully sculptable, which allows ease of accurate placement. It is also clearly visible with TRUS imaging and can be fully absorbed by the body within twelve months post-injection [

1]. The status of the spacer was observed in follow-up restaging CT scans at 1 and 3 months postoperatively. In both of these scans, the hypodense rectal spacer was captured anterior to the rectum and remained unchanged. The rectum appeared intact. However, the manufacturers of the HA rectal spacers have quoted a 12- to 18-month period to full spacer resorption. It would be interesting to study the long-term effects of these rectal spacers on bowel continence and QOL.

The use of HA rectal spacers in cases of confirmed T3 disease has not been tested, and it is unknown how the histopathology would be affected. Posterior bladder tumours of T3 or higher staging are indeed a concern in this technique. In our case, a preoperative MRI scan was obtained to ensure no rectal invasion. This MRI demonstrated suspected invasion into the seminal vesicles, but not the rectum. The final histopathology confirmed that while there was posterior disease superior to the seminal vesicles, it was confined to the bladder. As such, it is advisable to obtain a preoperative MRI to allow for patient selection and preoperative planning.

Although the utility of HA rectal spacers for rectal protection in complex urological surgeries is still in its infancy, we believe that it has immense potential, and future prospective studies need to be undertaken to evaluate how HA rectal spacers affect patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, D.T.S.W.; methodology, B.N.X.W. and A.H.; validation, D.T.S.W., D.B. and B.N.X.W.; data curation, B.N.X.W. and Z.A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.N.X.W.; writing—review and editing, D.T.S.W., A.H. and Z.A.; supervision, D.T.S.W. and D.B.; project administration, B.N.X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this case report as the patient has provided written informed consent for the retrospective data collection, production and publication of this case report. Thus, only observational data has been collected. All patient identifiers have been omitted.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the participant.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the anatomical pathology department for following up with the final histology report and all allied health staff for their great care and support for the patient.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Tempo, J.; Hong, A.; Woon, D.; Bolton, D. Hyaluronic Acid as a Tissue Spacer Between Prostate and Rectum to Aid Dissection During Radical Prostatectomy. Videourology 2023, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.F.; Sebo, T.J.; Blute, M.L.; Zincke, H. Salvage surgery for radiorecurrent prostate cancer: Contemporary outcomes. J. Urol. 2005, 173, 1156–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leibovici, D.; Kamat, A.M.; Pettaway, C.A.; Pagliaro, L.; Rosser, C.J.; Logothetis, C.; Pisters, L.L. Cystoprostatectomy for Effective Palliation of Symptomatic Bladder Invasion by Prostate Cancer. J. Urol. 2005, 174, 2186–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krol, R.; Smeenk, R.J.; van Lin, E.N.; Hopman, W.P. Impact of late anorectal dysfunction on quality of life after pelvic radiotherapy. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2013, 28, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björeland, U.; Notstam, K.; Fransson, P.; Söderkvist, K.; Beckman, L.; Jonsson, J.; Nyholm, T.; Widmark, A.; Thellenberg Karlsson, C. Hyaluronic acid spacer in prostate cancer radiotherapy: Dosimetric effects, spacer stability and long-term toxicity and PRO in a phase II study. Radiat. Oncol. 2023, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prada, P.J.; Fernández, J.; Martinez, A.A.; De La Rua, A.; Gonzalez, J.M.; Fernandez, J.M.; Juan, G. Transperineal injection of hyaluronic acid in anterior perirectal fat to decrease rectal toxicity from radiation delivered with intensity modulated brachytherapy or EBRT for prostate cancer patients. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol.* Biol.* Phys. 2007, 69, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozminski, M.; Konnak, J.W.; Grossman, H.B. Management of rectal injuries during radical cystectomy. J. Urol. 1989, 142, 1204–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, S.; Roseira, J.; Caldeira, P.; Vaz, A.M.; Guerreiro, H.; Codon, O. Rectal Perforation by a Balloon Spacer: A Rare Cause of Rectal Perforation Addressed Endoscopically. GE-Port. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 28, 416–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardekani, M.A.; Ghaffari, H. Optimization of prostate brachytherapy techniques with polyethylene glycol–based hydrogel spacers: A systematic review. Brachytherapy 2020, 19, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, A.; Ischia, J.; Chao, M. Case Report: Reversal of Hyaluronic Acid Rectal Wall Infiltration with Hyaluronidase. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 870388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Société Internationale d’Urologie. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).