Abstract

Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic has delayed screening, diagnostic workup, and treatment in prostate cancer (PCa) patients. Our purpose was to review PCa screening, diagnostic workup, active surveillance (AS), radical prostatectomy (RP), radiotherapy (RT), androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and systemic therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Materials and Methods: We performed a systematic literature search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, LILACS, and Web of Science, according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) statement for relevant material published from December 2019 to February 2021. Results: Prostate biopsy can be delayed, except when high-risk PCa is suspected or the patient is symptomatic. Active surveillance is appropriate for patients with very low risk, low risk (LR) and favorable intermediate risk (FIR). RP and RT for high risk and very high risk can be safely postponed up to 3 months. Hypofractionated external beam RT (EBRT) is recommended when RT is employed. ADT should be used according to standard PCa-based indications. Chemotherapy should be postponed until the pandemic is contained. Conclusions: The international urological community was not prepared for such an acute and severe pandemic. PCa patients can be adequately managed according to risk stratification. During the COVID-19 pandemic, LR and FIR patients can be followed with active surveillance. Delaying RP and RT in high risk and locally advanced disease is justified.

1. Introduction

In December 2019, a series of acute atypical respiratory diseases occurred in Wuhan, China, caused by a novel coronavirus, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), responsible for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic [1]. By the end of July 2020, 11.456 million confirmed COVID-19 cases and 530 937 deaths had been reported globally, and by mid-March 2021, 120 million cases and 2.6 million deaths had been reported, according to the COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University [2]. Some studies have suggested that men with COVID-19 have a higher risk than women for SARS-CoV-2-related complications and death [3,4].

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most frequently diagnosed urogenital neoplasm and is currently the second leading cause of cancer deaths in men in the United States and Europe [5,6].

COVID-19 remains a challenge for health care professionals all around the globe. Radical treatment, such as radiotherapy with curative intent and surgical procedures, has been affected by this pandemic. Bhat et al. reported an increase of approximately 22% of PCa patients on the waiting list of radical prostatectomies in a robotic oncological center, revealing the negative effect of COVID-19 on surgical PCa treatment [7]. We performed a systematic review of the best management recommendations for PCa patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, and sought to establish a foundation for PCa management in future pandemics. Our primary aim was to assess the evidence published to date with respect to the management of PCa with surgery, radiotherapy, androgen deprivation and systemic therapy, for all stages and risk stratification categories, since the beginning of COVID-19 pandemic. We also sought to determine whether studies on changes in PCa workup and management made because of the pandemic have provided adequately robust evidence to establish guidelines for PCa management in future pandemics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol development and registration

We registered our systematic review protocol in PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, registration number CRD42020193332), following the PRISMA-P (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- analyses Protocols) statement [8].

2.2. Eligibility criteria and literature search

We performed a systematic literature search using MEDLINE and EMBASE, Scopus, LILACS (Literatura Latinoamericana y del Caribe en Ciencias de la Salud), and Web of Science, including all indexed publications in English, Spanish, and French. We included recom- mendations, systematic reviews, clinical trials, and case- control, cohort, and cross-sectional studies related to the workup and management of PCa, patients (such as screening, diagnosis, any modality of treatment, radical prostatectomy (RP), radiation therapy (RT), androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), chemotherapy (ChT) and follow-up), from December 1, 2019, to February 28, 2021. Editorials, letters, and opinion articles were excluded.

2.3. Study selection and data extraction

Two independent investigators (AJMS and JSMA) performed the systematic literature search and screened all identified paper titles and abstracts. The full text of each identified article was reviewed by 3 independent investigators (AJMS, JSMA, INR). Any disagreement about individual study inclusion was resolved by a fourth investigator (EARG).

Information on included studies was entered into an Excel database. Information included the authors, country of research, publication title, date of publication, study design, indexed databases, management options studied in the publication methodology, outcome, and recommendations.

2.4. Risk of bias and quality assessment

Individual study quality assessment was performed using the appropriate tool for the study design and methodology: STROBE (Strengthening the Report of Observational Studies in Epidemiology-II) for cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies [9], AGREE II (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation) for guidelines and recommendations [10], and AMSTAR-2 (A Measurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews) for systematic reviews and meta-analysis [11]. The risk of bias (RoB) was assessed using the ROBINS-I [12] for individual included non-randomized studies, and the ROBIS [13] for systematic reviews. All recommendations based on non-systematic reviews were managed as expert consensus; therefore, no RoB was evaluated for such publications.

2.5. Outcome and synthesis methods

We performed data synthesis for each element of PCa management, including screening and diagnosis, surgical treatment, radiation therapy, androgen deprivation therapy, and systemic therapy. This synthesis was conducted for each PCa risk group in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Prostate Cancer Guidelines Risk Stratification as well as for each stage group (localized, locally advanced, and metastatic PCa) [14].

To determine adequate level of evidence and quality of recommendations for each different PCa management strategy, publication quality of evidence was established, using the SIGN statement for the level of evidence [15]. The priority of management recommendations was based on the European Urological Association Rapid Reaction Group level of priority for COVID-19 pandemic [16]: emergency priority, labeled as black (cannot be postponed > 24 hours because of life- threatening condition); high priority, red (should not be delayed > 6 weeks, since clinical harm such as progression, metastasis, loss of organ function, and death may occur); intermediate priority, yellow (cancel, but reconsider in case of increased capacity; delay of > 3 months may result in clinical harm and should therefore not be recommended); and low priority, green (clinical harm is very unlikely with delay of > 6 months).

3. Results

3.1. Literature search and study selection

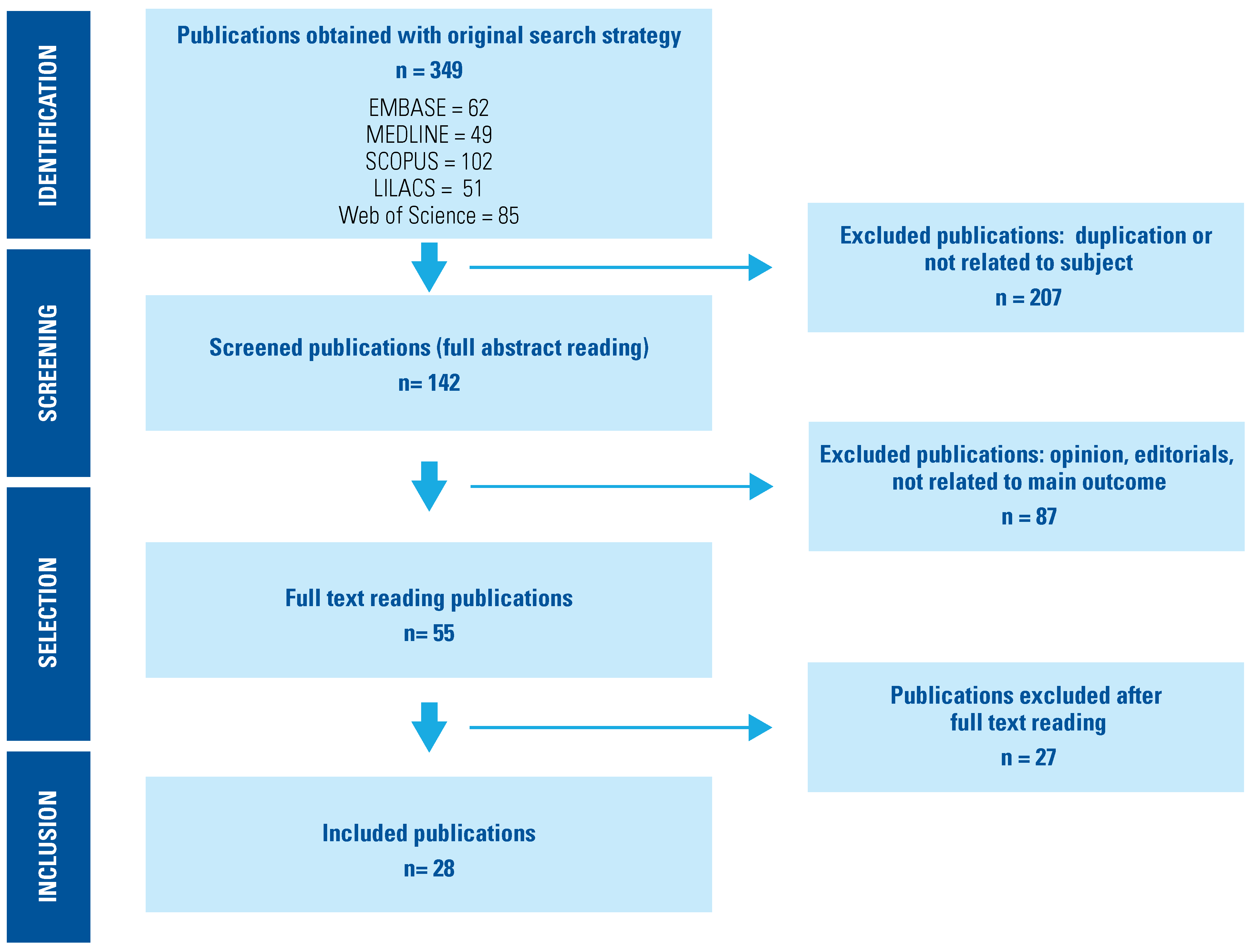

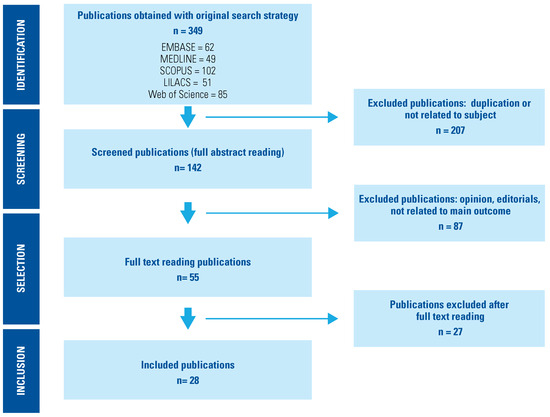

The literature search identified 349 papers from the different databases. After duplicates and articles not eligible for screening were eliminated, a total of 142 abstracts were screened, and 55 potentially eligible full text articles retrieved. Of these, 27 papers were excluded since outcomes were not documented; therefore, 28 publications were included in our systematic review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

3.2. Study characteristics, quality, and level of evidence

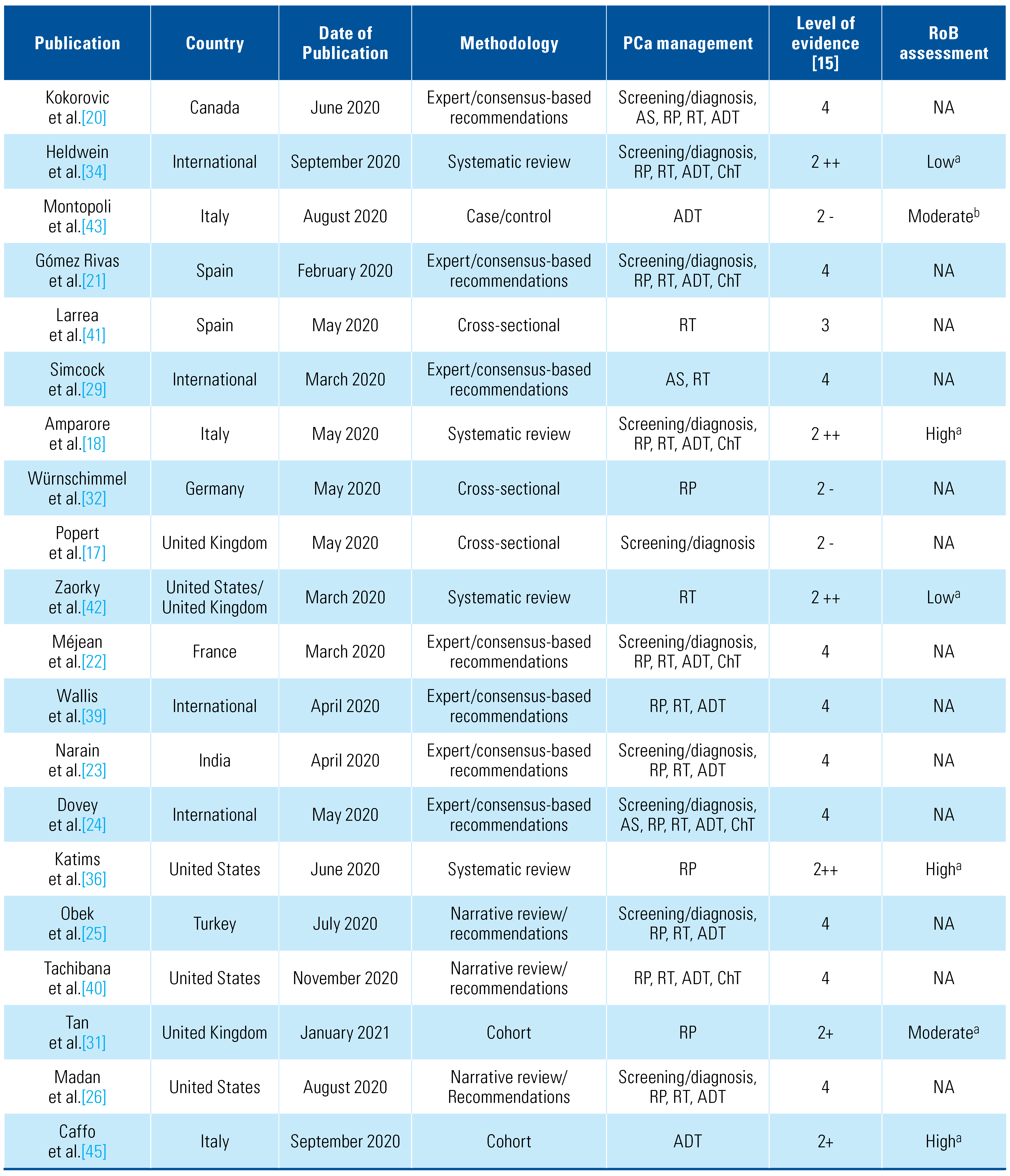

Of the included publications, 4 were systematic reviews, 16 expert opinion and consensus-based recommendations (non-systematic reviews), 1 case-control, and 3 cross-sectional and 4 cohort studies. Regarding quality of evidence, most of the studies complied with more than two-thirds of the corresponding tool items. Table 1 summarizes characteristics, study design, PCa management approached during the COVID-19 pandemic, results and recommendations, and SIGN level of evidence for each publication [15].

Table 1.

Characteristics of included publications.

3.3. Screening and diagnosis of PCa

Popert et al. [17] undertook a prospective cohort study of patients managed with prostate biopsy during the pandemic (April 2020) in the United Kingdom. They established a 3-level risk stratification:

- High risk (red): PSA density > 0.2ng/mL/cc and MRI suspicious lesions (Likert/PI-RADS 3, 4 and 5); biopsy should be performed within a month.

- Intermediate risk (amber): PSA density < 0.2 and suspicious lesions; biopsy within 3 months.

- Low risk (green): PSA density < 0.2 and no suspicious lesion; biopsy safely postponed indefinitely.

Amparore et al. [18] performed a systematic search of all urological association and society websites between April 8, and April 18, 2020, for guidelines on the management of urological pathologies during the pandemic. They concluded that prostate biopsies should be performed in men with suspected high-risk, locally advanced, or symptomatic PCa and this should be done without preceding MRI [19]. The remaining publications related to prostate biopsy are expert consensus recommendations [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]; most authors recommend that new PSA screening and continuation of diagnostic workup should not be performed until the pandemic is contained and suggest delaying prostate biopsy except in symptomatic patients [21,22,23], PSA > 10ng/mL [31,34,39], suspicion of cT3 disease, PSA doubling time (PSADT) < 6 months [24,27], or in case of medullary compression or obstructive renal failure secondary to PCa suspicion [22,27]. A summary of recommendations for screening and diagnosis is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of prostate cancer screening and diagnostic evaluation recommendations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.4. Active surveillance in PCa

Six papers (all of them being either narrative reviews or consensus-based recommendations) addressed the role of active surveillance (AS) in PCa patients and concluded that in very low risk (VLR), low risk (LR), and favorable intermediate risk (FIR) PCa patients, AS is an adequate management strategy [20,24,27,29,30]. For LR and FIR patients, Rodriguez-Sanchez et al. and Caicedo-Martinez et al. suggest implementation of AS while delaying RP and RT until the pandemic is controlled [27,30], and Kokorovic et al. suggest either AS or delaying RP up to 12 months [20]. Detti et al. recommend multi-parametric MRI (mpMRI) of the prostate instead of re-biopsy in patients on AS [28]. A summary of recommendations for AS is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of active surveillance recommendations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.5. Surgical management of PCa

Tan et al. performed a retrospective analysis of 282 patients who underwent RP between March and May 2020, 99% by robotic surgery, and none of the patients had developed SARS-CoV-2 infection at the 30-day follow-up after surgery [31].

In Germany, Würnschimmel et al. performed a retrospective analysis of all surgically treated Pca patients, reporting a total of 784 patients, 447 (57%) patients before the pandemic (January and February 2020) and 337 (43%) patients in the first month and a half of the pandemic before operating room shutdown (March and April 2020) [32]. Of a total of 784 patients, 623 (79%) patients were ISUP (International Society of Urological Pathology) grades group 1, 2, and 3 [33], corresponding to very low risk, low risk, favorable intermediate risk, and unfavorable intermediate risk. Of these, 352 patients were treated before the pandemic, and 271 during the first month of the outbreak. The authors reported no statistical difference related to complications and outcomes and no COVID-19 infection amongst the patients treated during the pandemic, and therefore concluded that performing surgery in these patients is feasible when adequate safety measures are in place [32].

Heldwein et al. performed a systematic review of all urological management recommendations issued during the first months of the pandemic, including both consensus-based recommendations and opinion- based recommendations. On the basis of a previous European Association of Urology (EAU) rapid reaction group statement [16], they proposed a 5-level, color-based triage for urological procedures priority: zero (red) for emergency: survivorship compromised if surgery not performed within hours; 1 (brown) proceed as planned, do not postpone: survivorship compromised if surgery nor performed within days; 2 (yellow), consider delaying up to 1 month: patient condition can deteriorate or survivorship be compromised if surgery not performed within 30 days or proceed as planned if COVID-19 trajectory not in rapid escalation phase; 3 (green) safe delay 1 to 3 months: proceed as planned if COVID-19 not in rapid escalation phase; 4 (blue) safe to delay > 3 months. For VLR, LR, FIR, and UIR prostate cancer, radical prostatectomy was considered blue level priority; therefore, delaying > 6 months is justified [34].

In a systematic search of rapid response recommen- dations and guidelines issued by European urological associations and societies, Amparore et al. found that all recommended delaying surgical management for low- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer [18]. Méjean et al. recommend delaying of RP in low- and intermediate-risk PCa for at least 2 months [22], Narain et al. and Shinder et al. recommend delaying for up to 6 months [23,35], and 3 consensus-based recommenda- tions state non-specific time delay of surgical treatment on LR and FIR PCa until the COVID-19 pandemic is controlled [21,27,36].

In 2020, Diamand et al. and Ginsburg et al. published retrospective cohort studies of intermediate- and high-risk PCa patients who underwent RP before the COVID-19 pandemic [37,38]. Diamand et al. performed a European multicenter study of 926 patients who had a delay of surgical treatment after PCa diagnosis and found no upgrading, lymph node involvement, or biochemical recurrence (BCR) associated with a 3-month delay of RP in intermediate- and high-risk PCa [37]. Ginsburg et al. studied 129 062 patients with the same characteristics and found no increase in adverse oncological outcomes after RP (upgrading, positive lymph nodes or need of adjuvant therapies) even after a 12-month delay [38].

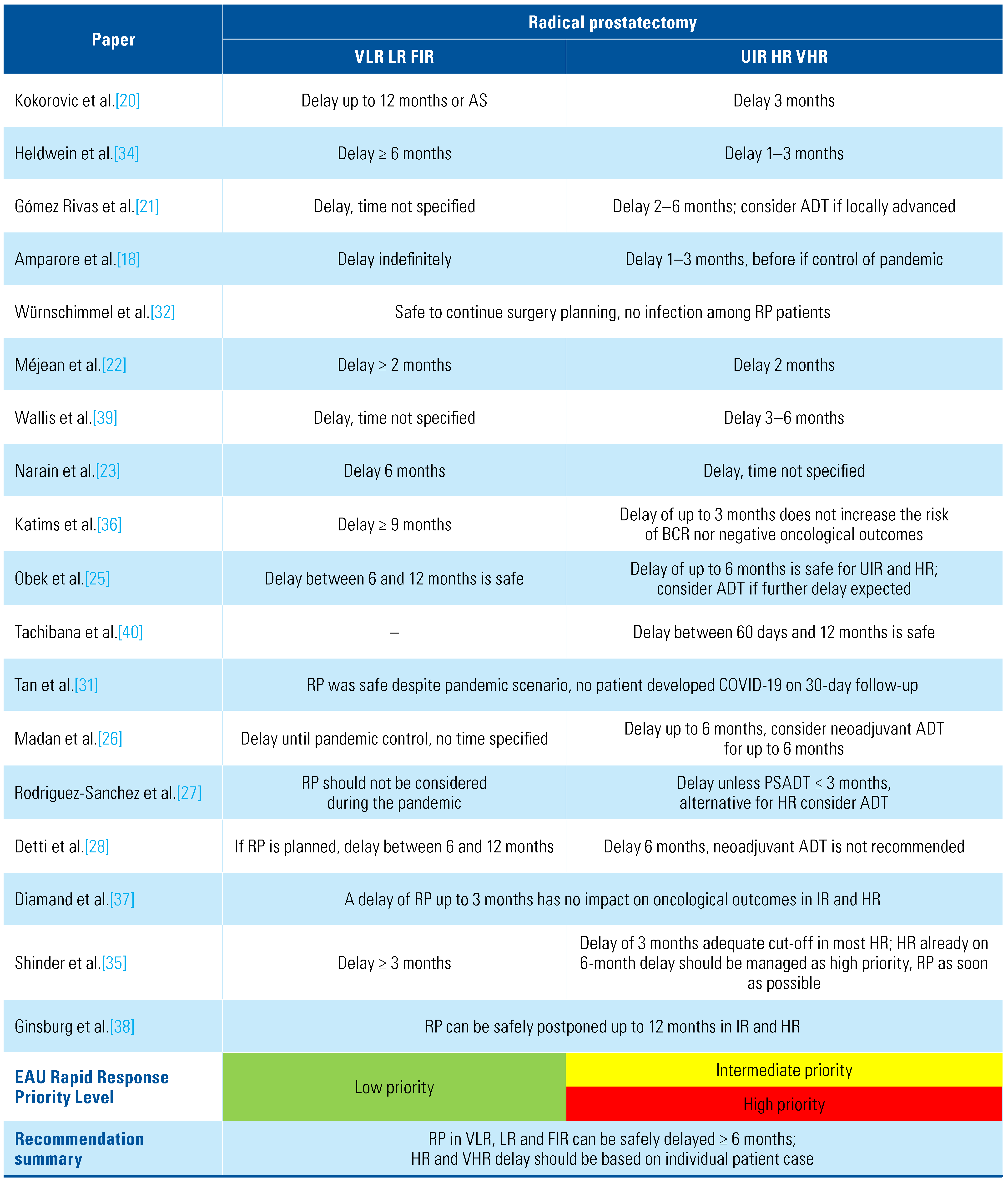

For high-risk (HR) and very high-risk (VHR) PCa patients, Würnschimmel et al., included 148 (19%) high-risk patients (ISUP 4 and 5) managed with radical prostatectomy, 83 (56%) before the pandemic and 65 (44%) during the first month of the pandemic. They reported no COVID-19 infections, and therefore suggested continuation of RP in high-risk patients with adequate COVID-19 safety measures [32]. Amparore et al. suggest not to continue RP for HR and locally advanced disease if possible [18]. Heldwein et al. concluded that RP for high-risk patients can be safely delayed between 1 and 3 months. If there is a delay of more than 3 months because of the pandemic, or if there is suspicion of lymph node involvement, ADT with or without RT can be initiated [34]. Most expert consensus-based published recommendations conclude that RP for high-risk patients can be safely delayed for between 2 and 6 months [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,35,39,40]. If further delay is expected, ADT should be considered until surgical management can be undertaken [21,22,23,24,25,26,40]. Katims et al., however, report that in high-risk patients there may be an increased risk of biochemical recurrence (HR 2.19; CI 95% 1.24 to 3.87; P = 0.007) and positive surgical margins (OR 4.08; CI 95% 1.52 to 10.9; P = 0.005) in case of > 9-month delay [36]. Summary of recommendations for surgical management is provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of radical prostatectomy recommendations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.6. Radiation therapy in PCa

Larrea et al. retrospectively reported on 100 oncology patients treated with external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). Only 9 had PCa. No stage or risk stratification of these patients is specified; however, 7 were treated with hypofractionated EBRT with curative intent, and the remaining 2 because of BCR, with no reports of COVID-19 infection in these patients [41].

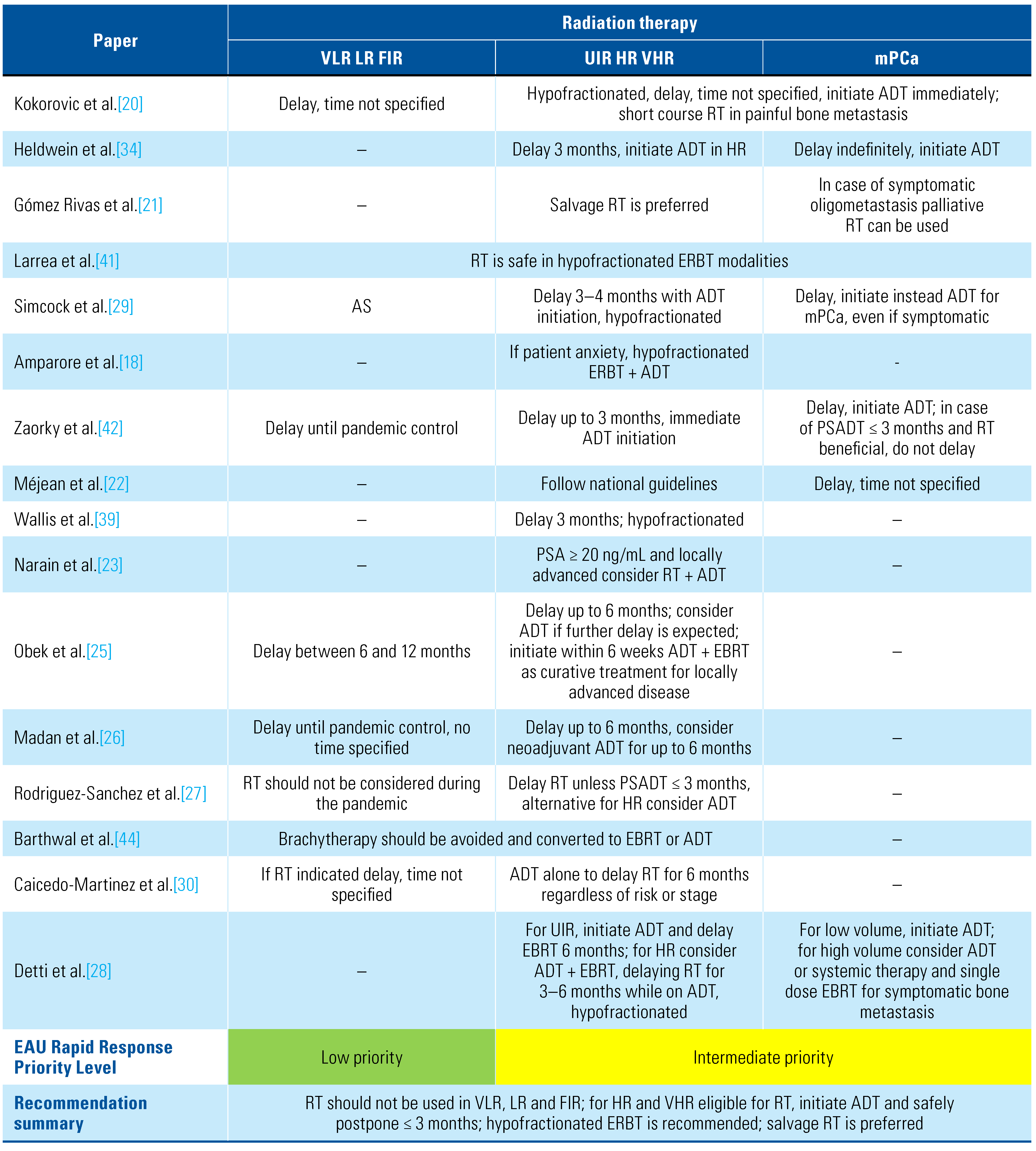

For low- and intermediate-risk PCa patients, all publications agree on active surveillance and delay of any modality of treatment [18,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,34,39,40]. For high- risk patients and locally advanced disease, 3 systematic reviews [18,34,42] conclude that if primary curative RT is planned, delay between 1 and 3 months is feasible. However, initiation of ADT should be immediate or as soon as possible: according to EAU priority, RT is considered level 2 (yellow) [34]. Three expert consensus- based recommendations suggest the use of RT with ADT in HR localized and locally advanced disease for patients not eligible for RP, with immediate initiation of long deposit ADT [20,21]. A delay of up to 3 months is considered safe and feasible [16]; however, most expert consensus documents recommend delays of up to 6 months, with initiation of ADT while waiting for RT [25,26,27,28,30,41]. For postprostatectomy RT, adjuvant RT should not be initiated; instead, salvage RT is recommended [18,20,22,28,29,34,39,42,43]. Metastatic disease requiring palliative RT management should be undertaken as soon as possible on the basis of symptomatic disease or risk of fracture and medullary compression [20,21,28]. Regardless of PCa risk and stage, brachytherapy is not recommended, and the ideal EBRT treatment should be either hypofractionated or ultra-hy pofractionated [18,20,21,22,25,26,27,28,29,30,34,39,41,44]. Follow-up with PSA testing after RT may be at 6-month intervals to reduce hospital exposure [27,30]. A summary of recommendations is provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of radiation therapy recommendations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.7. Androgen deprivation therapy in PCa

Montopoli et al. [43] performed a retrospective analytical study of all prostate cancer patients in Veneto, Italy, reporting a total of 118 SARS-CoV-2-positive cases: 4 were on ADT, and the remaining 114 were not. No PCa risk or stage was specified, but the authors concluded that PCa patients on ADT have a significantly lower risk of COVID-19 infection (OR 4.05; 95% CI 1.55 to 10.59). Caffo et al. [45] performed a multicenter retrospective study in Italy (20 oncological centers), including 1433 men with metastatic castration-resistant PCa (mCRPC), who continued oncological consultation during the pandemic (February to June 2020); 34 (2.3%) developed SARS-CoV-2 infection, all of them with ADT, 9 with concomitant chemotherapy, and 19 with concomitant androgen-receptor-axis-targeted therapies (ARAT). Thirteen patients (38.2%) died, 85.7% of whom had previously received 2 or more mCRPC therapies. The authors therefore concluded that mCRPC patients were at increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and mortality, regardless of ADT [38]. All included recommendations and systematic reviews conclude that ADT in VLR, LR, and FIR prostate cancer is not recommended [18,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,34,35,39,42,43,46]. For UIR and HR, as well as for locally advanced disease (N1) eligible for radical curative treatment, when RP is delayed, ADT can be safely initiated when pandemic-related delay is expected to surpass 3 to 6 months and in cases of patient cancer-related anxiety [18,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,34,35,39,42,43,46]. Immediate ADT, preferably a long depot (3- or 6-month duration) formulation, is recommended for hormone sensitive metastatic prostate cancer (mHSPC) [18,20,21,22,23,28,29,34,39,42,43,46]. For non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC), ADT plus ARAT, such as abiraterone, enzalutamide, apalutamide, or darolutamide is recommended. Madan et al. recommend enzalutamide, since no concomitant steroid is needed [26]. For mCRPC, when no previous second-generation hormone therapy has been used, ARAT (except abiraterone) is recommended. In both cases (nmCRPC and mCRPC), ARAT should be initiated as soon as possible [18,20,21,22,23,29,34,39,42,43,46]. The use of corticosteroids is controversial, and Méjean et al. do not recommend it [22]. If indicated, the lowest possible dose should be used: prednisone 5 mg twice daily, decreasing to once daily if there are individual concerns, has been suggested [23,46]. A summary of recommendations for ADT is provided in Table 6.

Table 6.

Summary of androgen deprivation therapy recommendations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.8. Chemotherapy in PCa

Five publications broached the subject of ChT in PCa patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, all of them consensus-based recommendations, advising against the use of docetaxel in metastatic disease. Méjean et al. recommend that in case of mCRPC, docetaxel or cabazitaxel may be used, but at a reduced dosage and with the concomitant use of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) [20,21,22,26]. Lalani et al. recommend the use docetaxel in case of mCRPC patients who have previously received ADT + ARAT with inadequate response, and in case of bone metastasis prefer only the use of Radium-223 [46]. A summary of recommendations is provided in Table 7.

Table 7.

Summary of chemotherapy recommendations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

4. Discussion

At the beginning of the pandemic, most institutions and countries issued non-specific and rapid response recommendations; however, as the pandemic continued, new evidence and complete reviews and recommendations were published. The main objective of each country and individual health system during the COVID-19 pandemic has been to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Despite this, however, it is still necessary to provide individual management for urological oncology patients. Although Popert et al. reported no COVID-19-related infection in prostate biopsy patients, all systematic reviews and recommendations support delaying biopsy and diagnostic workup in PCa until the pandemic is contained [17]. Würnschimmel et al. and Tan et al. published studies about RP during the pandemic, and even though no SARS-CoV-2 infection occurred, it is evident that at least for patients with low- or intermediate-risk PCa, active surveillance can be an adequate and safe alternative [31,32]. For high-risk patients, a delay of 6 months may be safe. In cases of patient anxiety or symptomatic PCa, treatment may be indicated, either ADT alone or ADT + RT. For mHSPC, ADT is also recommended, while in nmCRPC and mCRPC, immediate ARAT is the treatment of choice.

The PIVOT and ProtecT trials proved that in localized PCa, particularly in low- and intermediate- risk disease, curative treatment does not affect long-term mortality and survival on localized PCa, yet the ProtecT trial did find that active surveillance was associated with a higher incidence of biochemical recurrence and metastasis [47,48]. Although these studies report good outcomes in patients with non-metastatic PCa, oncological curative treatment in cases of UIR, HR and VHR, continues to be the desired treatment but the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has in many cases delayed its provision. We can conclude from this systematic review that all modalities of radical treatment for non- metastatic PCa can be safely delayed, and that ADT can be used as an alternative treatment during the pandemic in order to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The sudden onset of the COVID-19 pandemic led to the rapid publication of papers and recommendations, sometimes with inadequate methodology and low levels of evidence, as well as expert consensus-based recommendations. Because of this, few papers met our criteria, leaving a fairly small sample. The main limitation of our study is the lack of RoB analysis of expert consensus-based recommendations. This is due to absence of an adequate tool, as well as the absence of clinical trials and the impossibility of performing any meta-analysis because of the scarce information in each study.

5. Conclusions

The international urological community was not prepared for such a sudden and unprecedented global pandemic. Evidently an immediate emergency response was necessary to prevent and control SARS-CoV-2 infections in patients with urological comorbidities needing treatment, such as prostate cancer patients; however, COVID-19 paralyzed urologic oncology departments in most countries. This systematic review suggested that low-risk and intermediate-risk PCa patients can be managed with active surveillance, that delaying surgical and radiation therapy treatment in high-risk and locally advanced disease is justified, and that ADT is an adequate treatment option for HR and metastatic disease.

It is very likely that there will be new pandemics with implications, effects, and long-term outcomes similar to those of COVID-19. We hope that the present review will establish a foundation for the management of prostate cancer in future emergency scenarios and pandemics.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Abbreviations

| ADT | androgen deprivation therapy |

| ARAT | androgen-receptor-axis-targeted therapies |

| AS | active surveillance |

| BCR | biochemical recurrence |

| ChT | chemotherapy |

| EBRT | external beam radiation therapy |

| FIR | favorable intermediate risk |

| HR | high risk |

| LR | low risk |

| mCRPC | metastatic castrate resistant Pca |

| mpMRI | multi-parametric MRI |

| nmCRPC | non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer |

| Pca | prostate cancer |

| PSADT | PSA doubling time |

| RoB | risk of bias |

| RP | radical prostatectomy |

| RT | radiation therapy |

| UIR | unfavorable intermediate risk |

| VHR | very high risk |

| VLR | very low risk |

References

- Yuki, K.; Fujiogi, M.; Koutsogiannaki, S. COVID-19 pathophysiology: a review. Clin Inmunol. 2020, 215, 108427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- Jin, J.-M., Bai; He, W.; Wu, F.; Liu, W.-F.; Han, D.-M.; et al. Gender differences in patients with COVID-19: focus on severity and mortality. Front Public Health. 2020; 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, S.; Yu, M.; Wang, K.; Tao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID-19 inpatients in Wuhan. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020; Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.N. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015, 16, 5137–5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García de Paredes-Esteban, J.C.; Alegre-del Rey, E.J.; Asensi-Diéz, R. Docetaxel in hormone-sensitive advanced prostate cancer; GENESIS-SEFH evaluation report. Farm Hosp. 2017, 41, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, K.R.S.; Moschovas, M.C.; Rogers, T.; Onol, F.F.; Corder, C.; Shannon, R.; et al. COVID-19 model-based practice changes in managing a large prostate cancer practice: following the trends during a month-long ordeal. J Robot Surg. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; et al.; PRISMA-P Group Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwers, M.; Kho, M.E.; Browman, G.P.; Cluzeau, F.; Feder, G.; Fervers, B.; et al. on behalf of the AGREE next steps consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare. CMAJ. 2010, 182, E839–E842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, J.A.C.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savovic, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, P.; Savovic, J.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Caldwell, D.M.; Reeves, B.C.; Shea, B.; et al. ROBIS: a new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016, 69, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Prostate Cancer (Version2.2020). Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/ physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Harbour, R.; Miller, J. A new system for grading recommendations in evidence-based guidelines. BMJ. 2001, 323, 334–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribal, M.J.; Cornford, P.; Briganti, A.; Knoll, T.; Gravas, S.; Babjuk, M.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines Office Rapid Reaction Group: an organisation-wide collaborative effort to adapt the European Association of Urology Guidelines Recommendations to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Era. Eur Urol. 2020, 78, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popert, R.; Kum, F.; MacAskill, F.; Stroman, L.; Zisengwe, G.; Rusere, J.; et al. Our first month of delivering the prostate cancer diagnostic pathway within the limitations of COVID-19 using local anaesthetic transperineal biopsy. BJU Int. 2020, 126, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amparore, D.; Campi, R.; Checcucci, E.; Sessa, F.; Pecoraro, A.; Minervini, A.; et al. Forecasting the future of urology practice: a comprehensive review of the recommendations by International and European Associations on priority procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Urol Focus. 2020, 6, 1032–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Available online: http://uroweb.org/guideline/prostate-cancer/ (accessed on 8 August 2020).

- Kokorovic, A.; So, A.I.; Hotte, S.J.; Black, P.C.; Danielson, B.; Emmenegger, U.; et al. A Canadian framework for managing prostate cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic: recommendations from the Canadian Urologic Oncology Group and the Canadian Urological Association. Can Urol Assoc, J. 2020, 14, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez Rivas, J.; Domínguez, M.; Gaya, J.M.; Ramírez-Backhaus, M.; Puche-Sanz, I.; de Luna, F.; et al. Cáncer de próstata y la pandemia COVID-19. Recomendaciones ante una nueva realidad. Arch Esp Urol. 2020, 73, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Méjean, A.; Rouprêt, M.; Rozet, F.; Bensalah, K.; Murez, T.; Game, X.; et al. Recommandations CCAFU sur la prise en charge des cancers de l’appareil urogenital en période d’épidémie au Coronavirus COVID- 19. Prog Urol. 2020, 30, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narain, T.A.; Gautam, G.; Seth, A.; Panwar, V.K.; Rawal, S.; Dhar, P.; et al. Uro-oncology in times of COVID-19: the evidence and recommendations in the Indian scenario. Indian J Cancer. 2020, 57, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovey, Z.; Mohamed, N.; Gharib, Y.; Ratnani, P.; Hammouda, N.; Nair, S.S.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on prostate cancer management: guidelines for urologists. Eur Urol Open Sci. 2020, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obek, C.; Doganca, T.; Burak Argun, O.; Riza, A. Management of prostate cancer patients during COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Urol. 2020, 23, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan, A.; Siglin, J.; Khan, A. Comprehensive review of implications of COVID-19 on clinical outcomes of cancer patients and management of solid tumors during the pandemic. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 9205–9218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, L.R.; Cathelineau, X.; Pinto, A.M.A.; Borque-Fernando, Á.; Gil, M.J.; Yee, C.H.; et al. Clinical and surgical assistance in prostate cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic: implementation of assistance protocols. Int Braz J Urol. 2020, 46 (Suppl. 1), 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detti, B.; Ingrosso, G.; Becherini, C.; Lancia, A.; Olmetto, E.; Alì, E.; et al. Management of prostate cancer radiotherapy during the COVID- 19 pandemic: a necessary paradigm change. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2021, 27, 100331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simcock, R.; Thomas, T.V.; Estes, C.; Filippi, A.R.; Katz, M.S.; Pereira, I.J.; et al. COVID-19: global radiation oncology’s targeted response for pandemic preparedness. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2020, 22, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caicedo-Martinez, M.; González-Motta, A.; Gil-Quiñonez, S.; Galvis, J.C. Prostate cancer management challenges due to COVID-19 in countries with low-to-middle-income economies: A radiation oncology perspective. Rev Mex Urol. 2020, 0, 1–14 ISSN: 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.S.; Arianayagam, R.; Khetrapal, P.; Rowe, E.; Kearley, S.; Mahrous, A.; et al. Major urological cancer surgery for patients is safe and surgical training should be encouraged during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multicentre analysis of 30-day outcomes. Eur Urol Open Sci. 2021, 25, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Würnschimmel, C.; Maurer, T.; Knipper, S.; von Breunig, F.; Zoellner, C.; Thederan, I.; et al. Martini-Klinik experience of prostate cancer surgery during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. BJU Int. 2020, 126, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egevad, L.; Delahunt, B.; Srigley, J.R.; Samaratunga, H. International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) grading of prostate cancer—an ISUP consensus on contemporary grading. APMIS. 2016, 124, 433–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heldwein, F.L.; Loeb, S.; Wroclawski, M.L.; Sridhar, A.N.; Carneiro, A.; Lima, F.S.; et al. A systematic review on guidelines and recommendations for urology standard of care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Urol Focus. 2020, 6, 1070–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinder, B.M.; Patel, H.V.; Sterling, J.; Tabakin, A.L.; Kim, I.Y.; Jang, T.L.; et al. Urologic oncology surgery during COVID-19: a rapid review of current triage guidance documents. Urol Oncol. 2020, 38, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katims, A.B.; Razdan, S.; Eilender, B.M.; Wiklund, P.; Tewari, A.K.; Kyprianou, N.; et al. Urologic oncology practice during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review on what can be deferrable vs. nondeferrable. Urol Oncol. 2020, 38, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamand, R.; Ploussard, G.; Roumiguié, M.; Oderda, M.; Benamran, D.; Fiard, G.; et al. Timing and delay of radical prostatectomy do not lead to adverse oncologic outcomes: results from a large European cohort at the times of COVID-19 pandemic. World J Urol. 2020, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginsburg, K.B.; Curtis, G.L.; Timar, R.E.; George, A.K.; Cher, M.L. Delayed radical prostatectomy is not associated with adverse oncologic outcomes: implications for men experiencing surgical delay due to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Urol. 2020, 204, 720–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, C.J.D.; Novara, G.; Marandino, L.; Bex, A.; Kamat, A.M.; Karnes, R.J.; et al. Risks from deferring treatment for genitourinary cancers: a collaborative review to aid triage and management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Urol. 2020, 78, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tachibana, I.; Ferguson, E.L.; Mahenthiran, A.; Natarajan, J.P.; Masterson, T.A.; Bahler, C.; et al. Delaying cancer cases in urology during COVID- 19: review of the literature. J Urol. 2020, 204, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrea, L.; López, E.; Antonini, P.; González, V.; Berenguer, M.A.; Baños, M.C.; et al. COVID-19: hypofractionation in the radiation oncology department during the ‘state of alarm’: first 100 patients in a private hospital in Spain. ecancer. 2020, 14, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaorky, N.G.; Yu, J.B.; McBride, S.M.; Dess, R.T.; Jackson, W.C.; Mahal, B.A.; et al. Prostate cancer radiation therapy recommendations in response to COVID-19. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020, 5, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montopoli, M.; Zumerle, S.; Vettor, R.; Rugge, M.; Zorzi, M.; Catapano, C.V.; et al. Androgen-deprivation therapies for prostate cancer and risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2: a population-based study (N = 4532). Ann Oncol. 2020, 31, 1040–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthwal, M.; Pareek, V.; Mallick, S.; Sharma, D.N. Brachytherapy practice during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review on the practice changes. J Contemp Brachytherapy. 2020, 12, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffo, O.; Gasparro, D.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Volta, A.D.; Guglielmini, P.; Zucali, P.; et al. Incidence and outcomes of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in patients with metastatic castration- resistant prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2020, 140, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalani, A.A.; Chi, K.N.; Heng, D.Y.C.; Kollmannsberger, C.K.; Sridhar, S.S.; Blais, N.; et al. Prioritizing systemic therapies for genitourinary malignancies: Canadian recommendations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can Urol Assoc, J. 2020, 14, E154–E158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilt, T.J.; Jones, K.M.; Barry, M.J.; Adriole, G.L.; Culkin, D.; Wheeler, T.; et al. Follow-up of prostatectomy versus observation for early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017, 377, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdy, F.C.; Donovan, J.L.; Lane, J.A.; Mason, M.; Metcalfe, C.; Holding, P.; et al. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016, 375, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

This is an open access article under the terms of a license that permits non-commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. © 2021 The Authors. Société Internationale d'Urologie Journal, published by the Société Internationale d'Urologie, Canada.