High Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety in Patients with Chronic Respiratory Diseases Admitted to Intensive Care in a Low-Resource Setting

Abstract

:Highlights

- Depression and anxiety were highly prevalent among ICU patients with chronic respiratory diseases (CRDs), with over 80% experiencing depressive symptoms and up to 100% experiencing anxiety.

- Severe depression was notably more frequent in female patients and those of older age, while anxiety symptoms showed a strong correlation with depression and were more frequent in females.

- Routine mental health screening in critical-care settings for patients with CRDs is essential for early detection and holistic management.

- Integrating psychiatric support into ICU care pathways may improve patient outcomes and reduce the long-term burden of untreated psychological comorbidities.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Design and Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics and HDRS Scores by Respiratory Disease Categories

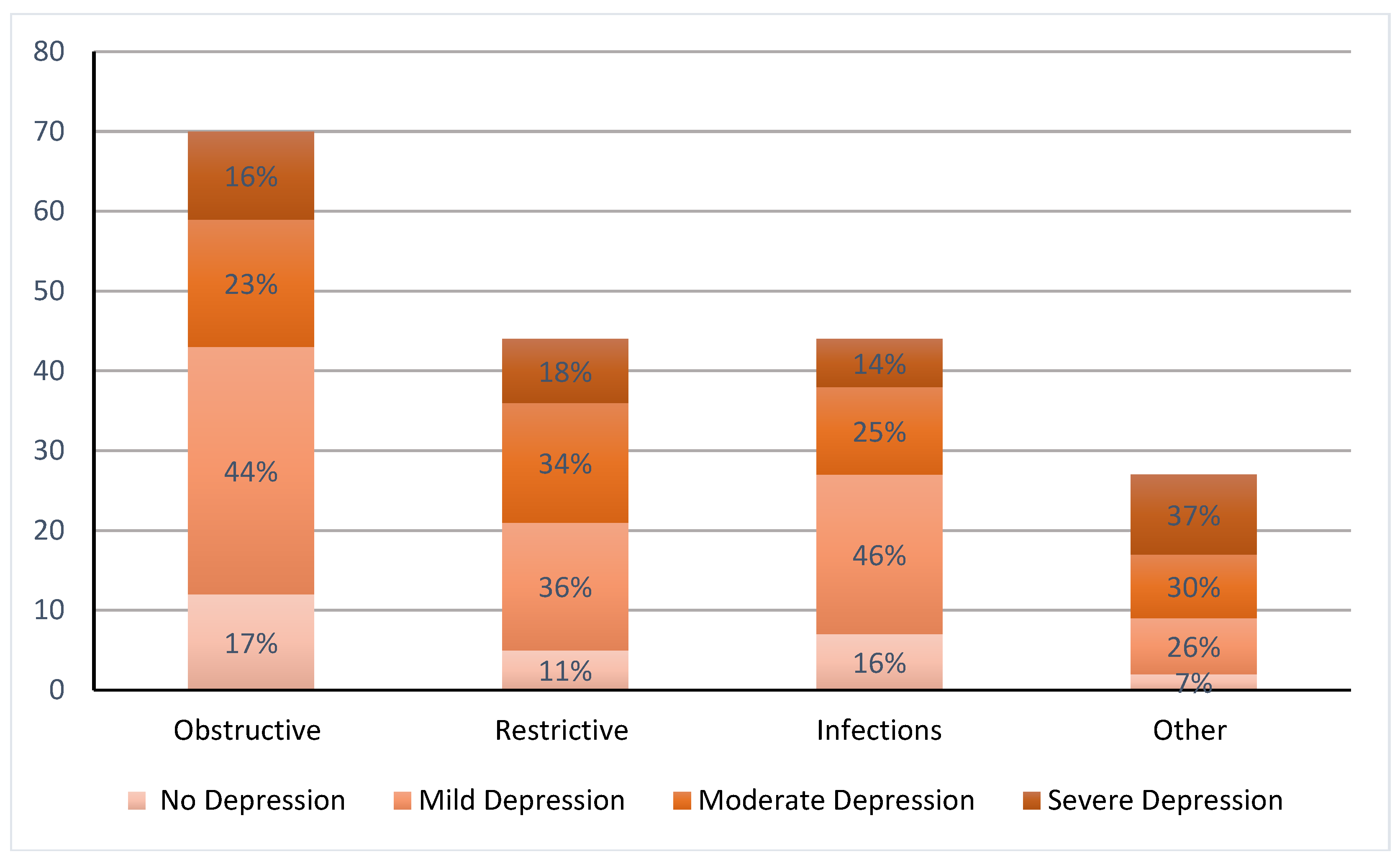

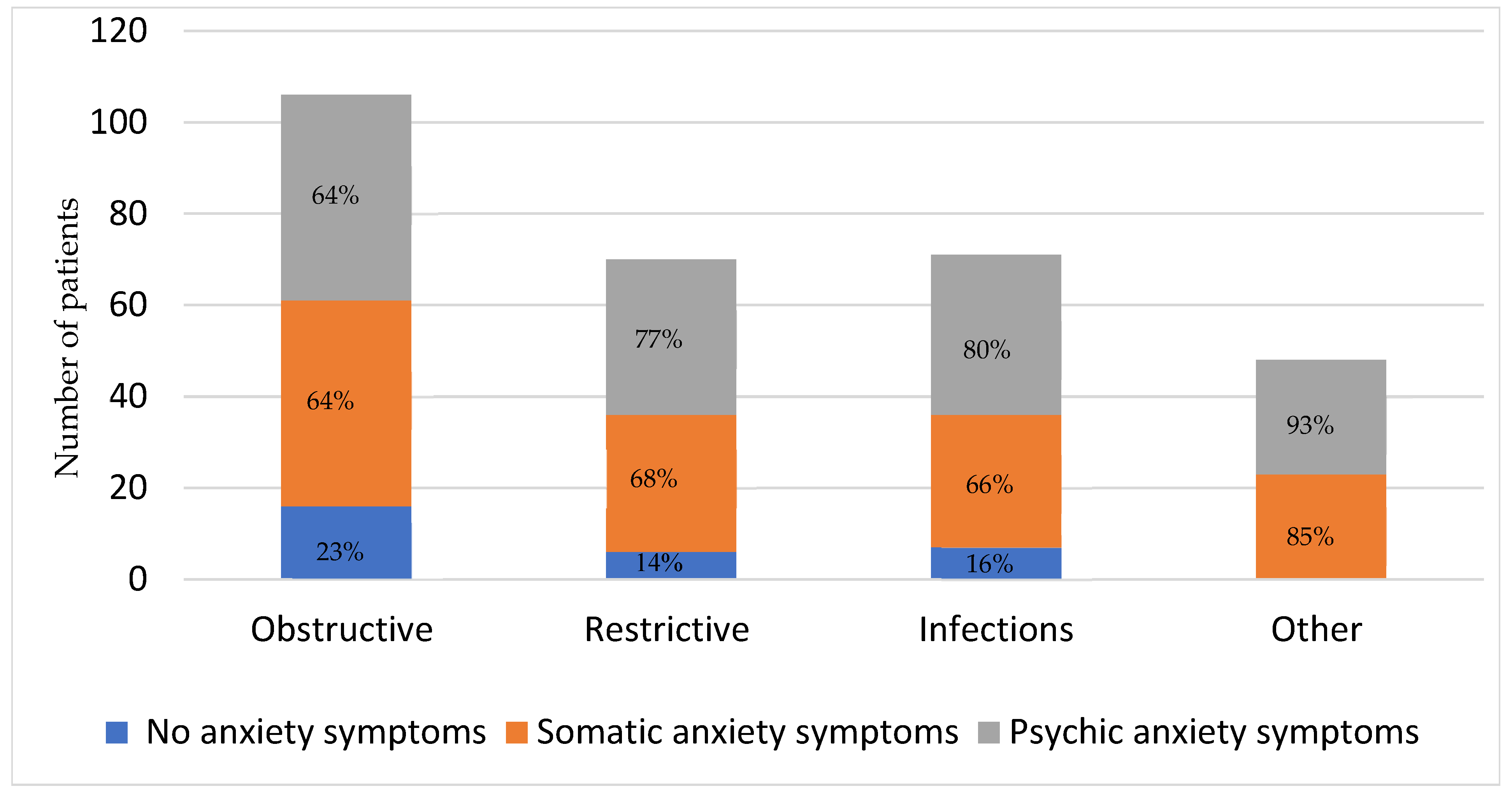

3.2. Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety by Respiratory Disease Categories

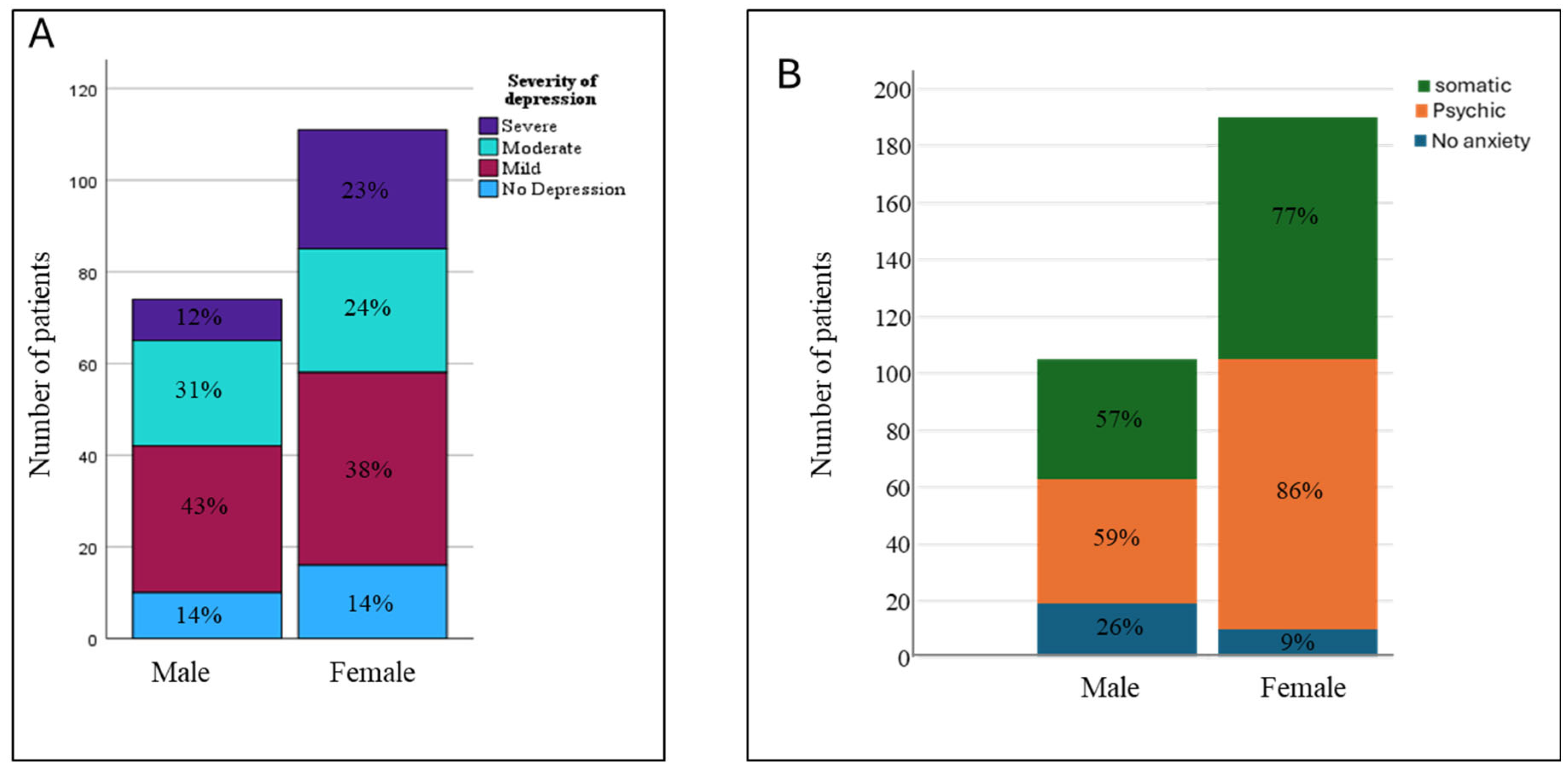

3.3. Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety by Gender and Age

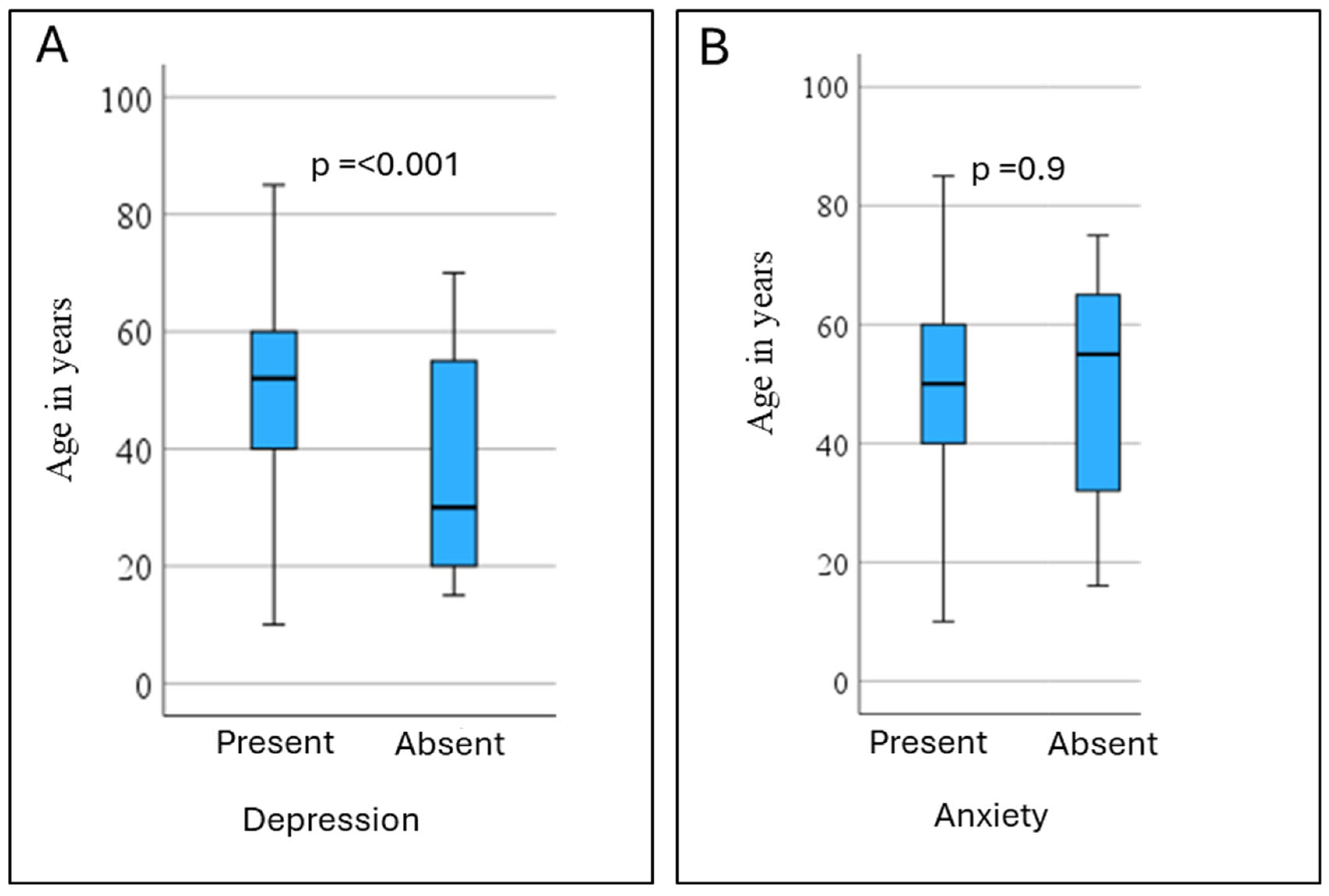

3.4. Factors Associated with Depression or Anxiety

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. 2024. Available online: https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/GINA-2024-Strategy-Report-24_05_22_WMS.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPD; The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: Deer Park, IL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, G.L. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacasse, Y.; Rousseau, L.; Maltais, F. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and depression in patients with severe oxygen-dependent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2001, 21, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpato, E.; Toniolo, S.; Pagnini, F.; Banfi, P. The Relationship Between Anxiety, Depression and Treatment Adherence in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2021, 16, 2001–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunik, M.E.; Roundy, K.; Veazey, C.; Souchek, J.; Richardson, P.; Wray, N.P.; Stanley, M.A. Surprisingly high prevalence of anxiety and depression in chronic breathing disorders. Chest 2005, 127, 1205–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Yoon, J.Y.; Kim, I.; Jeong, Y.H. The effects of personal resources and coping strategies on depression and anxiety in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart Lung 2013, 42, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, P.I.; Blumenthal, J.A.; Babyak, M.A.; Merrill, K.; Carney, R.M.; Davis, R.D.; Palmer, S.M.; Investigators, I. Psychiatric disorder and quality of life in patients awaiting lung transplantation. Chest 2003, 124, 1682–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahi, M.S.; Thilagar, B.; Balaji, S.; Prabhakaran, S.Y.; Mudgal, M.; Rajoo, S.; Yella, P.R.; Satija, P.; Zagorulko, A.; Gunasekaran, K. The Impact of Anxiety and Depression in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Adv. Respir. Med. 2023, 91, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, M.J.; Yohannes, A.M. The impact of depression in older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma. Maturitas 2016, 92, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohannes, A.M.; Alexopoulos, G.S. Depression and anxiety in patients with COPD. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2014, 23, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beekman, A.T.; de Beurs, E.; van Balkom, A.J.; Deeg, D.J.; van Dyck, R.; van Tilburg, W. Anxiety and depression in later life: Co-occurrence and communality of risk factors. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamdar, B.B.; Needham, D.M.; Collop, N.A. Sleep deprivation in critical illness: Its role in physical and psychological recovery. J. Intensive Care Med. 2012, 27, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1960, 23, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, J.H. Handbook of Biological Statistics, 3rd ed.; Sparky House Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bahra, N.; Amara, B.; Bourkhime, H.; El Yaagoubi, S.; Otmani, N.; Tachfouti, N.; Berraho, M.; Serraj, M.; Benjelloun, M.C.; El Fakir, S. Anxiety and Depression in Patients With Chronic Respiratory Diseases in the Fes-Meknes Region of Morocco. Cureus 2023, 15, e48349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansing, R.W.; Gracely, R.H.; Banzett, R.B. The multiple dimensions of dyspnea: Review and hypotheses. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2009, 167, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattouh, N.; Hallit, S.; Salameh, P.; Choueiry, G.; Kazour, F.; Hallit, R. Prevalence and factors affecting the level of depression, anxiety, and stress in hospitalized patients with a chronic disease. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2019, 55, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, M.O.; Chaudhry, I.B.; Blakemore, A.; Shakoor, S.; Husain, M.A.; Lane, S.; Kiran, T.; Jafri, F.; Memon, R.; Panagioti, M.; et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their association with psychosocial outcomes: A cross-sectional study from Pakistan. SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9, 20503121211032813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Qiu, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wu, K.; Ruan, X.; Wang, N.; Fu, C. Prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms and their associated factors in mild COPD patients from community settings, Shanghai, China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusmann, H.; Schulze, L.; Engel, S.; Bucklein, E.; Daehn, D.; Lozza-Fiacco, S.; Geiling, A.; Meyer, C.; Andersen, E.; Knaevelsrud, C.; et al. HPA axis activity across the menstrual cycle—A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2022, 66, 100998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudielka, B.M.; Kirschbaum, C. Sex differences in HPA axis responses to stress: A review. Biol. Psychol. 2005, 69, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M.P.; Bethencourt, J.M.; Ibanez, I. Gender differences in psychological distress in Spain. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2015, 61, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, S.; Babaei Khorzoughi, K.; Rahmati, M. The association between intergenerational relationships and depression among older adults: A comprehensive systematic literature review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2024, 119, 105313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moussavi, S.; Chatterji, S.; Verdes, E.; Tandon, A.; Patel, V.; Ustun, B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: Results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet 2007, 370, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Meena, R.; Sharma, R.; Yadav, N.; Mathur, A.; Jain, G. Study of Predictors of Quality of Life and its Association with Anxiety and Depression in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Industrial Workers. Indian. J. Community Med. 2020, 45, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hynninen, K.M.; Breitve, M.H.; Wiborg, A.B.; Pallesen, S.; Nordhus, I.H. Psychological characteristics of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2005, 59, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, C.; Thornicroft, G. Stigma and discrimination in mental illness: Time to Change. Lancet 2009, 373, 1928–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borak, J.; Sliwinski, P.; Tobiasz, M.; Gorecka, D.; Zielinski, J. Psychological status of COPD patients before and after one year of long-term oxygen therapy. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 1996, 51, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Aydin Sayilan, A.; Kulakac, N.; Sayilan, S. The effects of noise levels on pain, anxiety, and sleep in patients. Nurs. Crit. Care 2021, 26, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Respiratory Disease Categorization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obstructive | Restrictive | Infections | Other | p-Value | |

| (n = 70) | (n = 44) | (n = 44) | (n = 27) | ||

| Age—years median (IQR) | 55 (14) | 56 (22) | 43 (28) | 45 (24) | 0.001 |

| Sex | 0.001 | ||||

| 50 | 13 | 9 | 2 | |

| 20 | 31 | 35 | 25 | |

| Illness duration—years median (IQR) | 3 (4) | 2 (4) | 1.3 (1) | 1.4 (1) | 0.001 |

| Admission duration—days median (IQR) | 7(7) | 7 (7.5) | 17 (8) | 7 (4) | 0.031 |

| HDRS total score median (IQR) | 14 (9) | 18 (12) | 14 (13) | 20 (15) | 0.021 |

| Depression | Anxiety | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | p Value | Yes | No | p Value | |

| Age—years median (IQR) | 55 (20) | 30 (35) | <0.001 | 50 (20) | 55 (35) | 0.1 |

| Sex, n | 0.45 | 0.04 | ||||

| 64 | 10 | 55 | 19 | ||

| 95 | 16 | 101 | 10 | ||

| Respiratory disease category, n | 0.02 | 0.08 | ||||

| Obstructive (n = 70) | 58 | 12 | 54 | 16 | ||

| Restrictive (n = 44) | 39 | 5 | 38 | 6 | ||

| Infections (n = 44) | 37 | 7 | 37 | 7 | ||

| Other (n = 27) | 25 | 2 | 27 | 0 | ||

| Illness duration—years median (IQR) | 2 (3) | 1.4 (1) | 0.2 | 1.9 (3) | 2 (2.5) | 0.4 |

| Admission duration—days median (IQR) | 7 (7) | 5.5 (4.7) | 0.6 | 5(7) | 7 (8) | 0.8 |

| Depression | Anxiety | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p Values | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p Values | |

| Age | 1.09 (1.04–1.14) | <0.001 | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) | 0.360 |

| Sex | 0.75 (0.14–4.02) | 0.733 | 4.17(1.11–15.65) | 0.034 |

| Disease category | ||||

| (ref) | 0.557 | (ref) | 0.964 |

| 1.13 (0.21–6.20) | 0.886 | 1.19 (0.31–4.55) | 0.793 |

| 3.33 (0.54–20.61) | 0.195 | 0.78 (0.20–3.17) | 0.735 |

| 2.45 (0.28–21.77) | 0.422 | 19 (0-) | 0.998 |

| Illness duration—years | 1.08 (0.90–1.31) | 0.406 | 1.01 (0.87–1.17) | 0.886 |

| Admission duration—days | 1.04 (0.94–1.16) | 0.437 | 1.00 (0.97–1.04) | 0.830 |

| Psychic or somatic anxiety | 47.07 (9.86–224.69) | <0.001 | ||

| Depression | 46.89 (10.41–211.25) | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Polish Respiratory Society. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mustafa, A.; Karamat, A.; Toor, W.M.; Mustafa, T. High Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety in Patients with Chronic Respiratory Diseases Admitted to Intensive Care in a Low-Resource Setting. Adv. Respir. Med. 2025, 93, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm93030012

Mustafa A, Karamat A, Toor WM, Mustafa T. High Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety in Patients with Chronic Respiratory Diseases Admitted to Intensive Care in a Low-Resource Setting. Advances in Respiratory Medicine. 2025; 93(3):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm93030012

Chicago/Turabian StyleMustafa, Amun, Asifa Karamat, Wajeeha Mustansar Toor, and Tehmina Mustafa. 2025. "High Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety in Patients with Chronic Respiratory Diseases Admitted to Intensive Care in a Low-Resource Setting" Advances in Respiratory Medicine 93, no. 3: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm93030012

APA StyleMustafa, A., Karamat, A., Toor, W. M., & Mustafa, T. (2025). High Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety in Patients with Chronic Respiratory Diseases Admitted to Intensive Care in a Low-Resource Setting. Advances in Respiratory Medicine, 93(3), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm93030012