Working Memory Training Improves Cognitive and Clinical ADHD Symptoms in Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Process

2.2. Outcome Measures

- The clinical outcomes were the Vanderbilt Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Rating Scale and Vanderbilt ADHD Parent Rating Scale scores.

- The cognitive outcome was the CANTAB assessment (Cambridge Cognition, Cambridge, UK). The CANTAB is a widely used computer-based neuropsychological assessment for identifying cognitive deficits in children with ADHD [25]. It has also been previously explored in a Saudi Arabian child population [26]. The participants were assessed using three cognitive tests: the spatial WM (SWM) test for executive functions, the reaction time (RTI) test for impulsivity, and the rapid visual information processing (RVP) test for sustained attention. Impairments in the VWM and VSWM, in particular, are associated with inattentiveness and failure to filter out irrelevant stimuli [27]. Reaction times are typically faster in children with ADHD compared to those without; this reflects in difficulty in social interaction as they tend to interrupt or impulsively disrupt their surroundings [28]. Finally, the RVP test reflects decreased sustained attention ability among ADHD patients that is not easily reversed by simple coping techniques and remains the hallmark of the neurocognitive profile of the disease [29].

2.3. The Cogmed Intervention Program

2.4. Cogmed Parameters

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Baseline Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Cogmed Indices

3.3. ADHD Clinical Outcome Measures

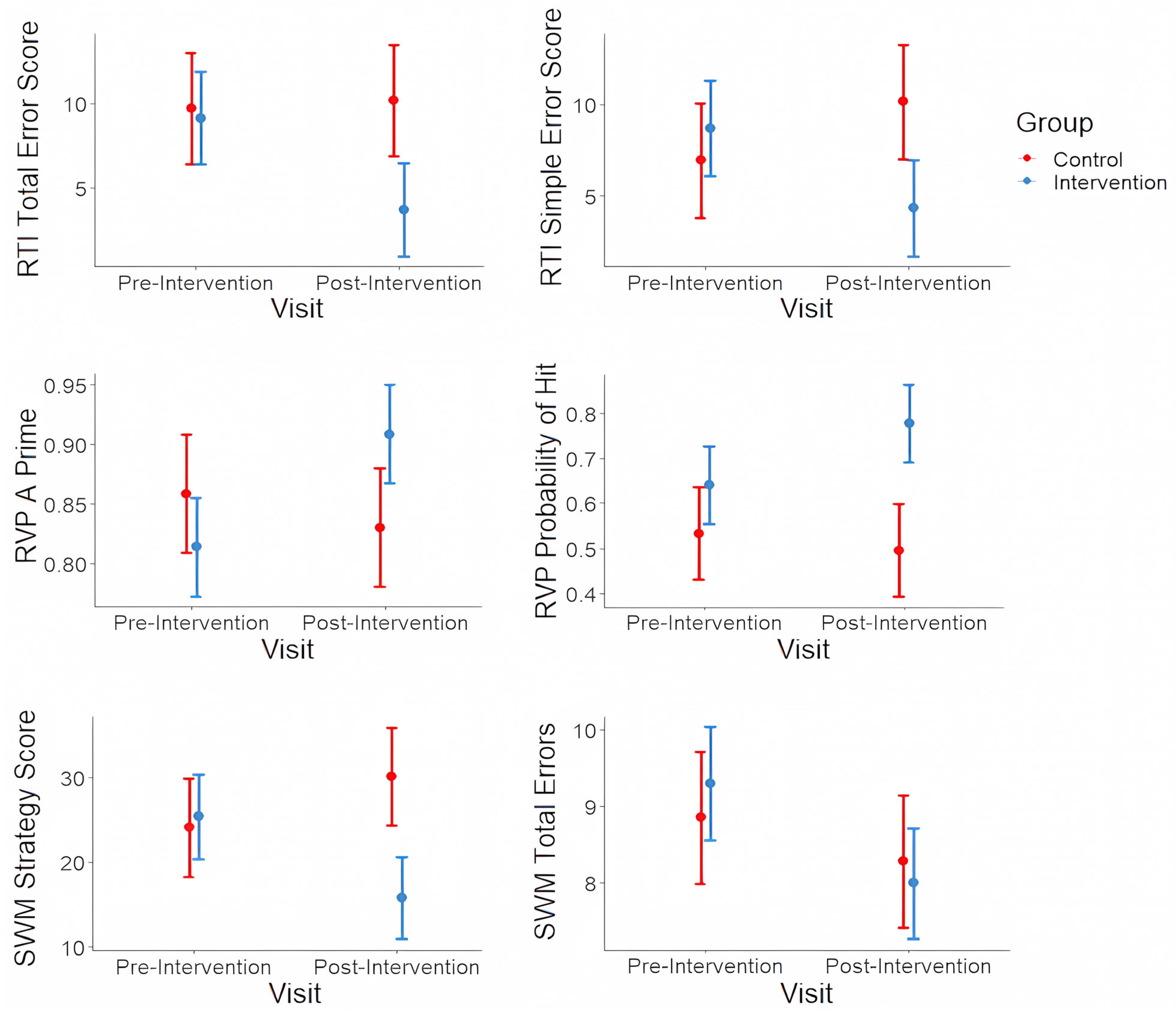

3.4. Cognitive Outcome Measures

3.5. Associations of Clinical and Demographic Characteristics with ADHD Clinical Outcomes Following Intervention

3.6. Associations of Clinical and Demographic Characteristics with ADHD Cognitive Outcomes Following Intervention

3.7. Associations of ADHD Clinical Outcomes (Inattention and Hyperactivity) with Cognitive Outcomes: Spatial Working Memory (SWM), Reaction Time (RTI), and Rapid Visual Information Processing (RVP)

3.8. Sensitivity and Power Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Associations of Clinical and Demographic Characteristics with ADHD Clinical Outcomes

4.2. Associations of Clinical and Demographic Characteristics with Cognitive Outcomes

4.3. Associations of ADHD Clinical Outcomes with Cognitive Outcomes

5. Limitations of This Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coghill, D.R.; Seth, S.; Matthews, K. A comprehensive assessment of memory, delay aversion, timing, inhibition, decision making and variability in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Advancing beyond the three-pathway models. Psychol. Med. 2014, 44, 1989–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, A.; Hong, D.S.; Shepard, S.; Moore, T. Linking ADHD to the neural circuitry of attention. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2017, 21, 474–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y. Chapter 8—Cognitive function in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. In ADHD: New Directions in Diagnosis and Treatment; Jill, M.N., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kofler, M.J.; Harmon, S.L.; Aduen, P.A.; Day, T.N.; Austin, K.E.; Spiegel, J.A.; Irwin, L.; Sarver, D.E. Neurocognitive and behavioral predictors of social problems in ADHD: A Bayesian framework. Neuropsychology 2018, 32, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veloso, A.; Vicente, S.G.; Filipe, M.G. Effectiveness of cognitive training for school-aged children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.C.; Gaynor, A.; Bessette, K.L.; Pearlson, G.D. A preliminary study of the effects of working memory training on brain function. Brain Imaging Behav. 2016, 10, 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.E.; Charach, A.; Bélanger, S.A. ADHD in children and youth: Part 2-treatment. Paediatr. Child Health 2018, 23, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingberg, T.; Fernell, E.; Olesen, P.J.; Johnson, M.; Gustafsson, P.; Dahlström, K.; Gillberg, C.G.; Forssberg, H.; Westerberg, H. Computerized training of working memory in children with ADHD-A randomized, controlled trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2005, 44, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J.; Gathercole, S.E.; Place, M.; Dunning, D.L.; Hilton, K.A.; Elliott, J.G. Working memory deficits can be overcome: Impacts of training and medication on working memory in children with ADHD. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2009, 24, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksayli, N.D.; Sala, G.; Gobet, F. The cognitive and academic benefits of Cogmed: A meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 2019, 27, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, S.; Ferrin, M.; Brandeis, D.; Buitelaar, J.; Daley, D.; Dittmann, R.W.; Holtmann, M.; Santosh, P.; Stevenson, J.; Stringaris, A.; et al. Cognitive training for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Meta-analysis of clinical and neuropsychological outcomes from randomized controlled trials. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 54, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapport, M.D.; Orban, S.A.; Kofler, M.J.; Friedman, L.M. Do programs designed to train working memory, other executive functions, and attention benefit children with ADHD? A meta-analytic review of cognitive, academic, and behavioral outcomes. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 1237–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, B.; Pennington, B.F.; Willcutt, E.G.; Dmitrieva, J.; Samuelsson, S.; Byrne, B.; Olson, R.K. Cross-country differences in parental reporting of symptoms of ADHD. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2019, 50, 806–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widding-Havneraas, T.; Markussen, S.; Elwert, F.; Lyhmann, I.; Bjelland, I.; Halmøy, A.; Chaulagain, A.; Ystrom, E.; Mykletun, A.; Zachrisson, H.D. Geographical variation in ADHD: Do diagnoses reflect symptom levels? Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 32, 1795–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. Hyperactive around the world? The history of ADHD in global perspective. Soc. Hist. Med. 2017, 30, 767–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mohsin, Z.J.; Al-Saffar, H.A.; Al-Shehri, S.Z.; Shafey, M.M. Saudi mothers’ perception of their children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in Dammam, Al-Qatif, and Al-Khobar cities, Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Community Med. 2020, 27, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, R. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Discourses in Saudi Arabia. Master’s Thesis, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Munshi, A.M.A. Knowledge and misperceptions towards diagnosis and management of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) among primary school and kindergarten female teachers in Al-Rusaifah district, Makkah city, Saudi Arabia. Intern. J. Med. Sci. Public Health 2014, 3, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis and Management; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng87 (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Bashiri, F.A.; Albatti, T.H.; Hamad, M.H.; Al-Joudi, H.F.; Daghash, H.F.; Al-Salehi, S.M.; Varnham, J.L.; Alhaidar, F.; Almodayfer, O.; Alhossein, A.; et al. Adapting evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in Saudi Arabia: Process and outputs of a national initiative. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2021, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almarzouki, A.F.; Bellato, A.; Al-Saad, M.S.; Al-Jabri, B. COGMED working memory training in children with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A feasibility study in Saudi Arabia. Appl. Neuropsychol. Child 2022, 12, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacko, A.; Bedard, A.C.; Marks, D.J.; Feirsen, N.; Uderman, J.Z.; Chimiklis, A.; Rajwan, E.; Cornwell, M.; Anderson, L.; Zwilling, A.; et al. A randomized clinical trial of Cogmed Working Memory Training in school-age children with ADHD: A replication in a diverse sample using a control condition. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2014, 55, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolraich, M.L.; Hagan, J.F., Jr.; Allan, C.; Chan, E.; Davison, D.; Earls, M.; Evans, S.W.; Flinn, S.K.; Froehlich, T.; Frost, J.; et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20192528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, R.; DiSalvo, M.; Kelberman, C.; Biederman, J. Can the CANTAB identify adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? A controlled study. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2021, 28, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashir, S.; Al Backer, N.; Alharbi, K.A.; Alfahadi, A.; Habib, S.S. Assessment of the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery test in Saudi children with learning disabilities: A case-control study. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Educational Neuroscience, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 11–12 March 2018; Available online: https://f1000research.com/articles/7-323/v1 (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- de Lima Ferreira, T.; Brites, C.; Azoni, C.A.S.; Ciasca, S.M. Evaluation of working memory in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychology 2015, 6, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korolczuk, I.; Burle, B.; Casini, L.; Gerc, K.; Lustyk, D.; Senderecka, M.; Coull, J.T. Leveraging time for better impulse control: Longer intervals help ADHD children inhibit impulsive responses. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0319621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somogyi, S.; Kilencz, T.; Szőcs, K.; Klein, I.; Balogh, L.; Molnár, R.; Bálint, S.; Pulay, A.J.; Nemoda, Z.; Baradits, M.; et al. Differential neurocognitive profiles in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder subtypes revealed by the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 274, 1741–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, D.; Maechler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S.; Christensen, R.H.B.; Singmann, H.; Dai, B.; Scheipl, F.; Grothendieck, G.; Green, P.; et al. Package “lme4”: Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using S4 Classes R Package Version. 2011. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lme4/lme4.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Bigorra, A.; Garolera, M.; Guijarro, S.; Hervas, A. Impact of working memory training on hot executive functions (decision-making and theory of mind) in children with ADHD: A randomized controlled trial. Neuropsychiatry 2016, 6, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capodieci, A.; Re, A.M.; Fracca, A.; Borella, E.; Carretti, B. The efficacy of a training that combines activities on working memory and metacognition: Transfer and maintenance effects in children with ADHD and typical development. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2019, 41, 1074–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, M.; Tannock, R. Working memory and inattentive behaviour in a community sample of children. Behav. Brain Funct. 2007, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waschbusch, D.A. A meta-analytic examination of comorbid hyperactive-impulsive-attention problems and conduct problems. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 118–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.M.H.; Butzbach, M.; Fuermaier, A.B.M.; Weisbrod, M.; Aschenbrenner, S.; Tucha, L.; Tucha, O. Basic and complex cognitive functions in Adult ADHD. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Donk, M.; Hiemstra-Beernink, A.-C.; Tjeenk-Kalff, A.; van der Leij, A.; Lindauer, R. Cognitive training for children with ADHD: A randomized controlled trial of cogmed working memory training and ‘paying attention in class’. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingberg, T. Training and plasticity of working memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2010, 14, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradov, S.; Fisher, M.; de Villers-Sidani, E. Cognitive Training for Impaired Neural Systems in Neuropsychiatric Illness. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 37, 43–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Saad, M.S.H.; Al-Jabri, B.; Almarzouki, A.F. A Review of Working Memory Training in the Management of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 686873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, F.; Sun, L.; Qian, Y.; Liu, L.; Ma, Q.G.; Yang, L.; Cheng, J.; Cao, Q.J.; Su, Y.; Gao, Q.; et al. Cognitive function of children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and learning difficulties: A developmental perspective. Chin. Med. J. 2016, 129, 1922–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overbeek, G.J.; van der Donk, M. Cognitive training for children with ADHD. Individual differences in training and transfer gains. Kind en Adolesc. 2016, 37, 256–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; King, M.D.; Jennings, J. ADHD remission, inclusive special education, and socioeconomic disparities. SSM—Popul. Health 2019, 8, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentz, A.; Guay, M.C.; Parent, V.; Romo, L. Working memory training for adults with ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2020, 24, 918–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattfeld, A.T.; Whitfield-Gabrieli, S.; Biederman, J.; Spencer, T.; Brown, A.; Fried, R.; Gabrieli, J.D. Dissociation of working memory impairments and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the brain. NeuroImage Clin. 2016, 10, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gau, S.S.F.; Shang, C.Y. Improvement of executive functions in boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: An open-label follow-up study with once-daily atomoxetine. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010, 13, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Full Sample | Control | Intervention | Group Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-intervention Sample (No.) | 47 | 14 | 33 | |

| Post-intervention Sample (No.) | 34 | 14 | 20 | |

| Age (Mean, SD) | 9.1 (2.1) | 10.0 (2.0) | 8.5 (2.0) | t(28) = 2.14, p = 0.041 * |

| Sex (No., %) | ||||

| Male | 21 (62%) | 8 (57%) | 15 (75%) | χ2 = 1.19, p = 0.273 |

| Female | 13 (38%) | 6 (43%) | 5 (25%) | |

| ADHD Subtype (No., %) | ||||

| Inattention | 9 (26%) | 5 (36%) | 4 (20%) | χ2 = 3.26, p = 0.195 |

| Hyperactivity/Impulsivity | 9 (26%) | 5 (36%) | 4 (20%) | |

| Combined | 16 (47%) | 4 (29%) | 12 (60%) | |

| Clinical Care (No., %) | ||||

| None | 14 (41%) | 8 (57%) | 8 (40%) | χ2 = 3.78, p = 0.286 |

| Medical | 9 (26%) | 2 (14%) | 7 (35%) | |

| Behavioral | 10 (29%) | 6 (43%) | 4 (20%) | |

| Combined | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) | |

| Co-occurring Conditions (No., %) | ||||

| ODD | 10 (29%) | 1 (7%) | 9 (45%) | χ2 = 7.43, p = 0.059 |

| CD | 4 (12%) | 1 (7%) | 3 (15%) | |

| Anxiety/Depression | 6 (18%) | 1 (7%) | 5 (25%) | |

| Learning Disabilities | 22 (65%) | 12 (86%) | 10 (50%) | |

| Education (No., %) | ||||

| Regular Education | 23 (68%) | 13 (93%) | 10 (50%) | χ2 = 6.91, p = 0.008 * |

| Special Education | 11 (32%) | 1 (7%) | 10 (50%) | |

| Parental Education (No., %) | ||||

| High School Diploma | 6 (18%) | 2 (14%) | 4 (20%) | χ2 = 0.79, p = 0.671 |

| Bachelor’s Degree/Diploma | 24 (71%) | 11 (79%) | 13 (65%) | |

| Master’s Degree/PhD | 4 (12%) | 1 (7%) | 3 (15%) | |

| Parental Occupation (No., %) | ||||

| Employed | 24 (71%) | 8 (57%) | 16 (80%) | χ2 = 3.72, p = 0.155 |

| Unemployed | 9 (26%) | 6 (43%) | 3 (15%) | |

| Student | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) |

| Full Sample | Control | Intervention | Group Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VADRS (Mean, SD) | 1.1 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.4) | F(1,32) = 5.86, p = 0.021 * |

| Inattention (Mean, SD) | ||||

| Pre-intervention | 1.9 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.8) | 2.0 (0.5) | F(1,32) = 2.29, p = 0.140 |

| Post-intervention | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.9) | 1.4 (0.6) | F(1,32) = 1.19, p = 0.284 |

| Hyperactivity (Mean, SD) | ||||

| Pre-intervention | 1.9 (0.8) | 1.8 (0.9) | 1.9 (0.7) | F(1,32) = 0.15, p = 0.698 |

| Post-intervention | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.9) | 1.6 (0.6) | F(1,32) = 0.52, p = 0.476 |

| Pre-Intervention | Post-Intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Task | Measure | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention |

| SWM | Strategy score (six to eight boxes) | 8.9 (2.1) | 9.3 (1.3) | 8.3 (1.0) | 8.0 (1.8) |

| Total errors (all boxes) | 24.1 (10.9) | 25.4 (6.7) | 30.1 (12.9) | 15.8 (12.5) | |

| Total errors (six boxes) | 6.9 (3.5) | 7.5 (2.6) | 10.4 (5.7) | 5.0 (4.0) | |

| Total errors (eight boxes) | 15.1 (7.4) | 15.3 (4.5) | 17.2 (9.5) | 8.9 (7.8) | |

| RTI | Mean movement time | 360.7 (136.4) | 424.6 (63.0) | 368.5 (331.2) | 378.5 (242.2) |

| Mean reaction time | 641.9 (184.4) | 729.8 (247.8) | 515.1 (186.3) | 593.1 (229.7) | |

| Total error score (five choices) | 9.7 (6.1) | 9.2 (7.6) | 10.2 (4.4) | 3.7 (5.7) | |

| Simple error score (all) | 6.9 (4.1) | 8.7 (7.3) | 10.1 (3.9) | 4.3 (6.5) | |

| RVP | A prime | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) |

| Mean response latency | 536.3 (118.6) | 664.6 (178.6) | 515.1 (86.5) | 517.3 (244.7) | |

| Probability of hit | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.2) | |

| Task | Measure | Intervention Effect |

|---|---|---|

| SWM | Strategy score (six to eight boxes) | Group-by-time interaction: F(1,32) = 1.27, p = 0.448 |

| Total errors (all boxes) | Group-by-time interaction: F(1,63) = 8.42, p = 0.039 * | |

| Intervention group: t(63) = −2.75, p = 0.039 * | ||

| Control group: t(63) = 1.47, p = 0.337 | ||

| Total errors (six boxes) | Group-by-time interaction: F(1,63) = 9.38, p = 0.039 * | |

| Intervention group: t(63) = −2.01, p = 0.125 | ||

| Control group: t(63) = 2.31, p = 0.080 | ||

| Total errors (eight boxes) | Group-by-time interaction: F(1,63) = 5.37, p = 0.080 | |

| RTI | Mean movement time | Group-by-time interaction: F(1,32) = 1.49, p = 0.231 |

| Mean reaction time | Group-by-time interaction: F(1,32) = 0.01, p = 0.911 | |

| Total error score (five choices) | Group-by-time interaction: F(1,32) = 6.88, p = 0.078 | |

| Simple error score (all) | Group-by-time interaction: F(1,32) = 14.96, p = 0.010 * | |

| Intervention group: t(32) = −3.48, p = 0.010 * | ||

| Control group: t(32) = 2.13, p = 0.176 | ||

| RVP | A prime | Group-by-time interaction: F(1,32) = 9.71, p = 0.025 * |

| Intervention group: t(32) = 3.73, p = 0.019 * | ||

| Control group: t(32) = −0.94, p = 0.420 | ||

| Mean response latency | Group-by-time interaction: F(1,32) = 2.27, p = 0.225 | |

| Probability of hit | Group-by-time interaction: F(1,32) = 4.50, p = 0.100 |

| Measure | Term | Mean | SE | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VADRS | Sex | F(1,19) = 12.02, p = 0.003 * | ||

| Female | 1.26 | 0.17 | ||

| Male | 1.42 | 0.21 | ||

| ADHD Subtype | F(2,19) = 0.77, p = 0.001 * | |||

| Combined | 1.48 | 0.14 | ||

| Hyperactive | 1.31 | 0.24 | ||

| Inattentive | 1.23 | 0.23 | ||

| ODD | F(1,19) = 8.31, p = 0.010 * | |||

| No | 1.18 | 0.21 | ||

| Yes | 1.49 | 0.19 | ||

| Inattention | ADHD Subtype | F(2,19) = 5.94, p = 0.010 * | ||

| Combined | 1.31 | 0.33 | ||

| Hyperactive | 0.38 | 0.56 | ||

| Inattentive | 1.20 | 0.53 | ||

| Hyperactivity | Sex | F(1,19) = 6.15, p = 0.023 * | ||

| Female | 0.90 | 0.29 | ||

| Male | 1.23 | 0.35 | ||

| ADHD Subtype | F(2,19) = 12.12, p < 0.001 * | |||

| Combined | 1.42 | 0.24 | ||

| Hyperactive | 1.81 | 0.40 | ||

| Inattentive | −0.04 | 0.38 | ||

| Medical Clinical Care | F(1,19) = 7.55, p = 0.013 * | |||

| No | 0.85 | 0.24 | ||

| Yes | 1.27 | 0.37 | ||

| Learning Disability | F(1,19) = 17.26, p = 0.001 * | |||

| No | 0.64 | 0.32 | ||

| Yes | 1.48 | 0.30 |

| Task | Measure | Term | Mean | SE | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWM | Total errors | Medical clinical care | F(1, 20) = 9.96, p = 0.015 * | ||

| No | 10.97 | 5.59 | |||

| Yes | 26.30 | 8.13 | |||

| Learning disability | F(1, 20) = 19.54, p < 0.001 * | ||||

| No | 7.08 | 7.20 | |||

| Yes | 30.18 | 6.71 | |||

| Total errors (four boxes) | Medical clinical care | F(1, 20) = 8.73, p = 0.016 * | |||

| No | 0.43 | 1.04 | |||

| Yes | 2.57 | 1.51 | |||

| Total errors (six boxes) | Learning disability | F(1, 20) = 6.90, p = 0.032 * | |||

| No | 2.85 | 3.35 | |||

| Yes | 9.56 | 3.11 | |||

| Total errors (eight boxes) | Medical clinical care | F(1, 20) = 10.04, p = 0.015 * | |||

| No | 6.20 | 3.45 | |||

| Yes | 15.64 | 5.01 | |||

| Learning disability | F(1, 20) = 23.00, p < 0.001 * | ||||

| No | 3.33 | 4.44 | |||

| Yes | 18.52 | 4.13 | |||

| RTI | Simple error score (all) | Learning disability | F(1, 20) = 14.20, p = 0.006 * | ||

| No | 3.80 | 2.91 | |||

| Yes | 12.21 | 2.71 | |||

| Simple error score (all) | Education type | F(1, 20) = 8.57, p = 0.048 * | |||

| Regular | 10.67 | 3.31 | |||

| Special | 5.35 | 2.35 | |||

| RVP | A prime | Learning disability | F(1, 20) = 9.51, p = 0.024 * | ||

| No | 0.99 | 0.07 | |||

| Yes | 0.85 | 0.06 | |||

| Probability of hit | Learning disability | F(1, 20) = 7.27, p = 0.028 * | |||

| No | 0.83 | 0.15 | |||

| Yes | 0.56 | 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Swiss Federation of Clinical Neuro-Societies. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alsaad, M.S.; Almarzouki, A.F.; Ghoneim, S.H.; Al-Jabri, B.A.; Suliman, S. Working Memory Training Improves Cognitive and Clinical ADHD Symptoms in Children. Clin. Transl. Neurosci. 2025, 9, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/ctn9040055

Alsaad MS, Almarzouki AF, Ghoneim SH, Al-Jabri BA, Suliman S. Working Memory Training Improves Cognitive and Clinical ADHD Symptoms in Children. Clinical and Translational Neuroscience. 2025; 9(4):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/ctn9040055

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlsaad, Maha S., Abeer F. Almarzouki, Solafa H. Ghoneim, Basma A. Al-Jabri, and Samraa Suliman. 2025. "Working Memory Training Improves Cognitive and Clinical ADHD Symptoms in Children" Clinical and Translational Neuroscience 9, no. 4: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/ctn9040055

APA StyleAlsaad, M. S., Almarzouki, A. F., Ghoneim, S. H., Al-Jabri, B. A., & Suliman, S. (2025). Working Memory Training Improves Cognitive and Clinical ADHD Symptoms in Children. Clinical and Translational Neuroscience, 9(4), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/ctn9040055