Abstract

Background: An early treatment start with disease modifying therapies (DMT) and long-term adherence is crucial in the treatment of people with multiple sclerosis (PwMS) to prevent future disability. Objectives: To gain information on the diagnostic process, decision making, treatment start and adherence with regard to DMT as well as satisfaction in PwMS in Switzerland to optimize management of PwMS. Methods: A survey was conducted between June 2017 and March 2018 in six hospital-based MS centres and eight private practices in Switzerland. PwMS according to the 2010 McDonald criteria, aged 18–60 years, having a clinical isolated syndrome, relapsing remitting MS, or secondary progressive MS were eligible. The survey contained 40 questions, covering participants’ background and circumstances, treatment decisions, therapy start, treatment adherence, and satisfaction (EKNZ Req-2016-00701). Results: 212 questionnaires were returned for analysis. Of these, 125 (59.0%) were answered by patients treated by practice-based neurologists and 85 (40.1%) by patients treated in hospitals. That PwMS were satisfied overall with current medical care, that they were free of relapses and disease progression, and that they were able to live independently were the main goals of patients. Satisfaction was reflected by an early therapy start and a high adherence to DMT in our cohort. The treating neurologist played a major role in this regard. Furthermore, a satisfactory first diagnostic consultation (FDC) was crucial for successful long-term patient care positively influencing an early treatment start, longer duration of the initial therapy, as well as adherence to treatments and general satisfaction. Conclusion: The treating neurologist and especially a satisfactory FDC play a major role for the successful long-term treatment of PwMS. Detailed information on various aspects of the disease and time with the treating neurologist seems to be of major importance.

1. Introduction

Treatment options in multiple sclerosis (MS) increased steadily over the past years with more and more available potent disease modifying therapies (DMT) positively influencing the disease course [1,2,3,4,5,6].

Early treatment start is crucial in the treatment of MS to prevent future disability because existing drugs take effect especially in the early, predominately inflammatory phase of the disease [7,8,9]. To treat people with MS (PwMS) early is therefore of major interest besides choosing the most optimal drug. To achieve this goal, the diagnostic criteria of MS were constantly refined over the past decades [10,11]. In addition, an increased MRI availability, increasing treatment options, and herewith, increasing disease awareness lead to an earlier diagnosis and therapy start over the last decades [12].

Nevertheless, a substantial number of patients still experience significant delays in the diagnosis and treatment start. A Swiss study by Kaufmann and colleagues found that, even in recent time periods, 40% of newly diagnosed persons with MS reported a delay of more than two years between first symptoms and MS diagnosis [13].

The reasons for delays are not fully understood. A population-based study from Canada found that onset at a younger age and having primary-progressive MS (PPMS) were associated with longer times to diagnosis [14]. A Swiss study by Barin and colleagues found that gait problems as initial symptoms, being diagnosed with primary progressive MS and having concomitant depression prolonged the time to diagnosis and treatment start [15].

Besides an early treatment start, long-term adherence to DMT is essential to obtain best possible treatment effects. Adherence to DMT and satisfaction have been shown to be associated with a reduced rate of relapses, emergency room (ER) visits, hospitalizations, neuropsychological issues, costs, and increased likelihood of higher quality of life (QoL) compared with non-adherent patients [16,17,18].

The aim of the current study was therefore to gain information on the diagnostic process, decision making with regard to treatment, treatment start and adherence as well as satisfaction in the care of PwMS in Switzerland. This information could improve the understanding of the current Swiss therapeutic landscape and lead to an optimization of the management of MS patients with regard to therapy start and maintenance as well as satisfaction with treatment and general care of PwMS.

2. Methods

Between June 2017 and March 2018, a survey was conducted in Switzerland. To obtain a cohort that best represented the Swiss MS population, six were hospital-based MS centres and eight were private practices. Inclusion criteria were patients diagnosed with MS according to the 2010 McDonald criteria, aged 18–60 years, having a clinical isolated syndrome (CIS), relapsing remitting MS (RRMS), or secondary progressive MS (SPMS) [10]. Main exclusion criteria were diagnosis of primary progressive MS due to the lack of approved therapies at the time of the survey as well as any diseases or conditions that would affect the adequate performance of the study procedures.

2.1. Questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed by the first author (principal investigator) and designed by an independent company (Appletree CI Group AG [ACG+], Winterthur, Switzerland) for paper and online data collection in German and French language. Printed questionnaires were transmitted to the MS centres in sealed envelopes, each having a unique study number that was associated with an MS centre to facilitate questionnaire tracking. The questionnaires were distributed to eligible patients during routine appointments at the MS centres. Questionnaires answered on paper were sent directly to ACG+ in post-paid envelopes. Alternatively, patients could answer questionnaires online using a unique code that was printed on the questionnaire envelopes. The exact return rate was not evaluated and reminders were not sent due to the anonymised nature of the questionnaire.

The survey contained 40 questions. The first 12 questions determined the participants’ background and circumstances. Questions 13–40 established treatment decisions, therapy start, treatment adherence, and satisfaction. The disease course of each participant was provided by their neurologists (question 5). The final English version of the questionnaire is shown as Supplementary Material.

The study design was discussed with the responsible ethics committee (Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz, EKNZ) and the decision was made that no written patient information or patient consent forms were required given that the questionnaire was anonymised (EKNZ Req-2016-00701).

2.2. Statistical Analysis

For the descriptive evaluation of the survey, categorical variables have been expressed as number of cases and percentages. In principle, all questions in the survey were captured in terms of categories. However, a number of variables were ordinally scaled, often using a Likert scale (1–5). Mean (and standard deviation) were shown for some of these Likert scale variables because it makes level differences somewhat easier to see than using the median.

Kendall’s tau-b, a nonparametric rank correlation coefficient, has been used in order to assess bivariate association between variables. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA (Version 15.2 or later, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

In total, 212 questionnaires were returned for analysis (185 questionnaires were answered on paper; and 27 online). Of these, 125 (59.0%) questionnaires were answered by patients treated by practice-based neurologists and 85 (40.1%) questionnaires by patients treated in hospitals. 76.1% came from the German speaking part and 23.9% from the French speaking part of Switzerland.

3.1. Patient Characteristics

The characteristics of the study population are outlined in Table 1. Most patents were female (72.8%) and had relapsing-remitting MS (89.6%). Age and time since diagnosis were well distributed over the different categories. Most patients (>90%) had completed professional school/apprenticeship or higher educations. Being free of relapses and disease progression and living independently were the most significant factors for patients with regard to the disease and most patients had a medium to high general safety need (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients characteristics (n = 212).

3.2. Treatment Decision

Most MS diagnoses were made in hospitals (65%) compared to private practices and in the majority of cases (59.43%), two or more consultations for the first diagnostic consultation (FDC), in which the diagnosis was communicated, and treatment decision were performed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Treatment decision (n = 212).

The quality of the FDC was rated mostly good with 56.9% rating 1 and 2 on a lickert scale from 1–5. However, approximately 30% of patients were unsatisfied with the FDC.

Patients felt mostly well informed about treatment options, and 60.4% of patients felt that all possible treatment options were discussed by the neurologist. In 75.5%, the neurologist recommended a certain therapy.

Patients received information about therapeutic options mainly from the treating neurologist (82.1%). Frequent additional sources were the internet (52.4%), talking to other patients (24.1%), talking to the family doctor (20.3%) or to MS-Nurses (20.3%).

However, MS-Nurses played a very important role in the final treatment decision in only 13% of patients although 75% had support by a MS-nurse (Table 2).

Key goals to initiate therapy after the first diagnosis were being free from relapses, delaying disability, and being independent. With regard to the influence of side effects on treatment decisions, there was no outstanding factor.

Overall, patients felt safe with regard to their treatment decision; however, approximately 25% of patients felt unsafe or very unsafe (Supplementary Table S1).

50% of patients stated that more time with the neurologist and more information on side effects and safety profile would have been helpful with regard to treatment decisions.

Approximately 1/5 of patients obtained a second opinion after receiving the diagnosis of MS, which was perceived useful to 65% of them (Table 2).

If patients would have retrospectively opted for the same DMT after their initial diagnosis correlated significantly with the satisfaction with the FDC (tau-b = 0.18, p = 0.008), the initial medication (not being interferon, tau-b = 0.23, p = 0.002), information on treatment options provided by the physicians (tau-b = 0.23, p < 0.001), and the confidence in treatment decision (tau-b = 0.21, p = 0.002).

3.3. Treatment Start

After the first diagnosis of MS, 32.8% started a disease-modifying therapy within 4 weeks and 71% within 3 months. 14.7% started with a delay over 12 months (Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment start (n = 212).

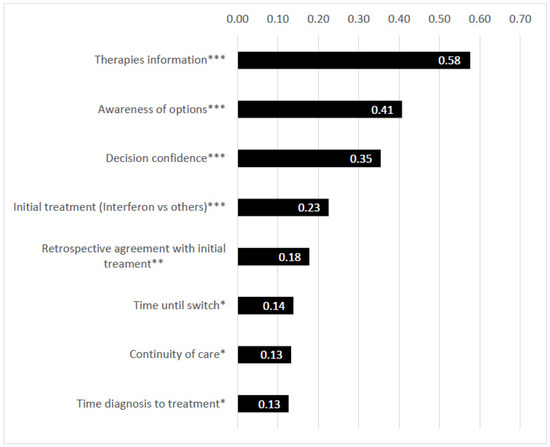

The time from diagnosis to therapy start was shorter the more recent the MS diagnosis was made (p < 0.001), in younger patients (tau-b = 0.22, p < 0.001), RRMS compared to SPMS (tau-b = 0.19, p = 0.003) and the more the patients were satisfied with the FDC (tau-b = 0.13, p = 0.033). In retrospect, patients were satisfied with the FDC if they felt informed about the different therapy options (tau-b = 0.58, p < 0.001), if all possible therapies were presented (tau-b = 0.41, p < 0.001), the safer the patient felt during the decision (tau-b = 0.35, p < 0.001) and if the initial therapy was not interferon (Avonex, Betaferon, Rebif) (tau-b = 0.23, p < 0.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Correlations in terms of satisfaction with the first diagnostic consultation (FDC). Legends *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001. Numbers in the bar charts of the graphic: Kendall’s tau-b (rank correlation, abs. values).

3.4. Treatment Adherence

60% of patients were currently treated in private practices and 40% in hospital-based centres. Visits were performed unevenly with most of the patients (93%) consulting the treating neurologist at least once a year, and 63% at least twice a year. Most patients changed their DMT during the course of the disease with around 25% of patients staying on the initial therapy, however 40% being on second therapy and 22% on the third or more DMT (Table 4). With regard to current DMTs, Gilenya and Tysabri were prescribed most frequently.

Table 4.

Treatment adherence.

More than 33% switched the DMT within 3 years and most patients (60.3%) switched from injectables to other therapies. The most common reasons for switching the DMT were lack of efficacy, undesirable side effects and the type of drug-application.

Overall, 70% of the patients reported, that they had been on continuous treatment since first diagnosis, defined as being treated 75–100% of the time since the first diagnosis. Satisfaction with the FDC correlated significantly with a longer duration of the initial therapy (tau-b = 0.14, p = 0.019) an overall treatment adherence over time (tau-b = 0.13, p = 0.037).

As additional factors positively influencing treatment adherence, the efficacy of the medication, the treating neurologist, and self-motivation were predominantly mentioned by patients.

3.5. Treatment Satisfaction

The satisfaction with current medical care was high with 81.6% being satisfied or very satisfied. Similar results were seen for satisfaction with the current DMT.

64.1% described their QoL as good or very good, 12.6% as bad or very bad (Supplementary Table S2). QoL was higher if patients satisfied with the current DMT (tau-b = 0.48, p < 0.001) as well as the overall treatment and care (tau-b = 0.44, p < 0.001), if patients were of younger age (tau-b = 0.15, p = 0.009), felt informed about the different therapy options (tau-b = 0.15, p = 0.011), and were satisfied with the FDC (tau-b = 0.14, p = 0.014). In addition, satisfaction with the FDC was higher if the initial (tau-b = 0.16, p = 0.014) and current (tau-b = 0.13, p = 0.048) therapy was not interferon (Avonex, Betaferon, Rebif). Having not obtained a second opinion after their diagnosis (tau-b = 0.14, p = 0.040) was positively correlated to QoL as well (tau-b = 0.14, p = 0.040).

4. Discussion

In this cross-sectional Swiss survey we describe the treatment landscape of MS patients in Switzerland focusing on treatment decision, treatment start, treatment adherence and satisfaction and factors influencing these aspects.

As expected, the majority of participants were females above 30 years and the most common form was RRMS followed by SPMS and CIS as PPMS was an exclusion criterion of the study. Age and the time since the first diagnosis were well distributed. Participants were in general not willing to take high risks with a medium to high general security necessity (Table 1).

The first diagnosis of MS was mostly made in hospitals but afterwards, most patients received care from outpatient neurologists. The most important reasons to initiate a therapy were being free from relapses, delaying disability progression, and independence while participants were initially mostly unconcerned with regard to side effects and generally felt safe with regard to DMT.

In the majority of cases two or more consultations were performed for the FDC and treatment decision.

Satisfaction with the FDC was in general high, independent of the place the FDC was performed, i.e., hospital or private practice. Patients felt mostly well informed about treatment options and safe with regard to their treatment decision, which positively influenced satisfaction with regard to the FDC and the choice of initial DMT. This was shown in prior studies as well in which shared decision making and information about different MS related topics led to a higher patient satisfaction with the FDC [19].

However, patients with RRMS and with more recent diagnosis felt better informed than older patients (above 40 years) with lower education (obligatory school education) which is probably at least partly due to the growing knowledge of the disease and the increasing therapeutic options in RRMS in recent years [1], while there were no significant differences regarding the MS type.

A large number of patients would have desired more time with the treating neurologists at the FDC and to have more information about the potential side effects and long-term data of therapies. These results are again in line with previous analysis showing that patient satisfaction with the FDC is driven by the duration of FDC and the number of discussed topics [19], and dissatisfaction in urban family physician care is mainly driven by short durations of service [20]. It however has to be pointed out that in our experience, approximately 30–60 min are usually allocated for an initial consultation in Switzerland, which is usually longer compared to other countries; however, there are not enough MS-specific data available on the subject [21]. Therefore, the results cannot be directly transferred to other countries and the influence of duration of MS consultations on the satisfaction with the FDC compared internationally would be of interest. These aspects could therefore be taken into account to improve future consultations and especially the FDC. For example, informing patients and relatives via not only booklets, but also professional homepages such as from MS patient organisations, which could facilitate the discussion during the consultation. In addition, modern technology such as wearable devices (watches etc.) could be increasingly used to gain more information about disease aspects outside the consulting hours for a more directed and productive discussion with patients [22,23,24,25].

The primary source of information was the treating neurologist, which highlights its role despite various other options of information. MS nurses didn’t seem to play a crucial role in the treatment decisions; however, they did play an important role as therapy companion over time. It must, however, be noted that 1/3 of patients didn’t have any support from an MS-nurse probably because MS-nurses are only available in bigger MS centers in Switzerland and usually not in private practices.

A second opinion was opted by PwMS that by trend had higher educational qualifications and prolonged MS-diagnosis for more than 15 years. There were no gender-specific differences and the majority of the patients were satisfied by obtaining a second opinion. However, treatment start was delayed by obtaining a second opinion. Therefore, a second opinion should be supported, however in a timely manner.

DMT initiation was quite fast in our opinion with around 70% of participants starting within 3 months after the FDC. Younger age of patients, a high satisfaction with the FDC, and having RRMS/CIS compared to SPMS led to an earlier therapy start. These findings corroborate with previous data by Kaufmann et.al 2018, in particular with regard to age and more recent time of diagnosis [13], and can be explained by the constantly revised diagnostic criteria in recent years resulting in a faster diagnosis of MS after initial symptoms [26], the increasing number of approved DMT for RRMS and the lack of potent therapeutic options as well as problems in diagnosing SPMS [26]. We did not examine the reasons for not having any DMT as this group was very small in our cohort.

Adherence to DMT is essential for a successful treatment as nonadherence or nonpersistence is associated with poorer clinical outcomes, including higher rates of relapse and disease progression, and higher medical resource use including the need of hospitalisations [27,28,29,30]. Previous studies showed adherence rates of 41% to 88% depending on the medication [31,32].

Therefore, an adherence rate of approx. 70% in our cohort seems to be in line, especially as adherence rates in chronic diseases tend to become less over time [33].

As major factors influencing adherence, the treating neurologist, efficacy of the treatment and self-motivation were mentioned by patients. In addition, a satisfactory FDC resulted in longer treatment duration of the initial DMT and longer overall adherence. Around 44% of the participants switched their DMT within 3 years of treatment with higher rates seen in younger patients up to 40 years probably due to the advanced therapeutic options. As expected, a longer disease duration was associated with more frequent DMT changes. The common reasons for non-adherence were side effects, lack of efficacy and practical issues. Main reasons for switching medication were practical inconvenience of the injectables, improved efficacy and tolerance of oral or intravenous drugs that were approved in recent years. Therefore, it is not surprising that switching was highest in patients initially treated with injectables that were the first approved MS-drugs in the market.

The overall satisfaction regarding medical treatment and current medical care was high, however only 60% of participants stated their QoL as high or very high. Satisfaction with the FDC, current DMT, overall treatment and care, and being younger was favourable for QoL.

5. Limitations

This survey has some limitations. The survey was performed in Switzerland. Therefore, the results cannot directly be transferred to other countries. Patients were mostly recruited in specialized MS centres or practicing physicians specialized in MS which could lead to a shift towards a well-treated patient cohort. In addition, the study design might have favored well educated and younger patients with more interest in participating in a survey and the patients that were more satisfied with the attending neurologist. Due to anonymity reasons, no data were collected of which patient groups took part in the study and the return rate was not evaluated. Another important limitation is the missing data of PPMS-patients, as there were no approved therapies including Ocrevus and Mavenclad during the recruitment period. Remembrance errors are possible, the longer ago the diagnosis was made. This questionnaire was completed by the participants only except for the type of the disease that was filled in by the treating neurologist. Therefore, perceptions of the treating neurologists were not considered in this study.

6. Conclusions

PwMS were satisfied overall with current medical care, with being free of relapses and disease progression, as well as with living independently as the main goals of patients. Satisfaction is reflected by an early therapy start and a high adherence to DMT in our cohort. The treating neurologist plays a major role in this regard. Furthermore, a satisfactory FDC is crucial for a successful long-term patient care positively influencing an early treatment start, longer duration of the initial therapy as well as adherence to treatments and general satisfaction. Overall, patients would like to spend more time with the treating neurologist, especially with regard to detailed information on various aspects of the disease.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ctn6010004/s1, Questionnaire, Table S1: Treatment decision (n = 212), Table S2: Treatment satisfaction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P.K. and P.M.; methodology, C.P.K.; software, D.L.; validation, M.W., A.C. and N.K. and T.V.; formal analysis, C.P.K., P.M. and D.L.; investigation, C.P.K.; resources, C.P.K.; data curation, C.P.K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.P.K. and P.M.; writing—review and editing, P.M.; visualization, C.P.K. and P.M.; supervision, C.P.K.; project administration, C.P.K.; funding acquisition, C.P.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Merck (Schweiz) AG, Zug, Switzerland, an affiliate of Merck KGaA (CrossRef Funder ID: 10.13039/100009945).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study design was discussed with the responsible ethics committee (Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz, EKNZ) and the decision was made that no written patient information or patient consent forms were required given that the questionnaire was anonymised (EKNZ Req-2016-00701).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed Consent was not required based on the decision of the ethics committee.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in Supplementary Material.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients and their families, investigators, co-investigators, and the study teams at each of the participating centres, and at Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, as well as Appletree CI Group AG, Winterthur, Switzerland (supported by Merck (Schweiz) AG*) for the technical set up of the survey and data analysis. In addition, the authors would like to acknowledge Ludwig Schelosky, Andreas Bock, Natalia Vokatch, Joseph-André Ghika, Verena Blatter, Filippo Donati, Serge Roth, Christophe Henny, Petra Stellmes, Yvonne Spiess, Adam Czaplinski, and Stefanie Müller for data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

A.C. has received speakers’/board honoraria from Actelion (Janssen/J&J), Almirall, Bayer, Biogen, Celgene (BMS), Genzyme, Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany), Novartis, Roche, and Teva, all for hospital research funds. He received research support from Biogen, Genzyme, and UCB, the European Union, and the Swiss National Foundation. He serves as associate editor of the European Journal of Neurology, on the editorial board for Clinical and Translational Neuroscience and as topic editor for the Journal of International Medical Research. C.P.K. has received honoraria for lectures as well as research support from Biogen, Novartis, Almirall, Bayer Schweiz AG, Teva, Merck, Genzyme, Roche and the Swiss MS Society (SMSG). N.K. received travel and/or speaker honoraria and served on advisory boards for Alexion, Biogen, Merck, Sanofi Genzyme and Roche and received research support by Biogen not related to this work. P.M., D.L. and T.V. have nothing to disclose.

References

- Kamm, C.P.; Uitdehaag, B.M.; Polman, C.H. Multiple Sclerosis: Current Knowledge and Future Outlook. Eur. Neurol. 2014, 72, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.A.; Coles, A.J.; Arnold, D.L.; Confavreux, C.; Fox, E.J.; Hartung, H.P.; Havrdova, E.; Selmaj, K.W.; Weiner, H.L.; Fisher, E.; et al. Alemtuzumab versus interferon beta 1a as first-line treatment for patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2012, 380, 1819–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, A.J.; Twyman, C.L.; Arnold, D.L.; Cohen, J.A.; Confavreux, C.; Fox, E.J.; Hartung, H.P.; Havrdova, E.; Selmaj, K.W.; Weiner, H.L.; et al. Alemtuzumab for patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis after disease-modifying therapy: A randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2012, 380, 1829–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannoni, G.; Comi, G.; Cook, S.; Rammohan, K.; Rieckmann, P.; Soelberg Sørensen, P.; Vermersch, P.; Chang, P.; Hamlett, A.; Musch, B.; et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral cladribine for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalban, X.; Hauser, S.L.; Kappos, L.; Arnold, D.L.; Bar-Or, A.; Comi, G.; de Seze, J.; Giovannoni, G.; Hartung, H.P.; Hemmer, B.; et al. Ocrelizumab versus Placebo in Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, S.L.; Bar-Or, A.; Comi, G.; Giovannoni, G.; Hartung, H.P.; Hemmer, B.; Lublin, F.; Montalban, X.; Rammohan, K.W.; Selmaj, K.; et al. Ocrelizumab versus Interferon Beta-1a in Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodin, D.S.; Reder, A.T.; Ebers, G.C.; Cutter, G.; Kremenchutzky, M.; Oger, J.; Langdon, D.; Rametta, M.; Beckmann, K.; DeSimone, T.M.; et al. Survival in MS: A randomized cohort study 21 years after the start of the pivotal IFNβ-1b trial. Neurology 2012, 78, 1315–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmer, T.A.; Baggesen, L.M.; Nørgaard, M.; Magyari, M.; Sorensen, P.S.; on behalf of the Danish Multiple Sclerosis Group. Early versus later treatment start in multiple sclerosis: A register-based cohort study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2018, 25, 1262-e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannoni, G.; Butzkueven, H.; Dhib-Jalbut, S.; Hobart, J.; Kobelt, G.; Pepper, G.; Sormani, M.P.; Thalheim, C.; Traboulsee, A.; Vollmer, T. Brain health: Time matters in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2016, 9, S5–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polman, C.H.; Reingold, S.C.; Banwell, B.; Clanet, M.; Cohen, J.A.; Filippi, M.; Fujihara, K.; Havrdova, E.; Hutchinson, M.; Kappos, L.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 69, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.J.; Baranzini, S.E.; Geurts, J.; Hemmer, B.; Ciccarelli, O. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2018, 391, 1622–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comi, G.; Radaelli, M.; Soelberg Sørensen, P. Evolving concepts in the treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2017, 389, 1347–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, M.; Kuhle, J.; Puhan, M.A.; Kamm, C.P.; Chan, A.; Salmen, A.; Kesselring, J.; Calabrese, P.; Gobbi, C.; Pot, C.; et al. Factors associated with time from first-symptoms to diagnosis and treatment initiation of Multiple Sclerosis in Switzerland. Mult. Scler. J. Exp. Transl. Clin. 2018, 4, 2055217318814562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingwell, E.; Leung, A.L.; Roger, E.; Duquette, P.; Rieckmann, P.; Tremlett, H.; the UBC MS Neurologists. Factors associated with delay to medical recognition in two Canadian multiple sclerosis cohorts. J. Neurol. Sci. 2010, 292, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barin, L.; Kamm, C.P.; Salmen, A.; Dressel, H.; Calabrese, P.; Pot, C.; Schippling, S.; Gobbi, C.; Müller, S.; Chan, A.; et al. How do patients enter the healthcare system after the first onset of multiple sclerosis symptoms? The influence of setting and physician specialty on speed of diagnosis. Mult. Scler. 2020, 26, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Cai, Q.; Agarwal, S.; Stephenson, J.J.; Kamat, S. Impact of adherence to disease-modifying therapies on clinical and economic outcomes among patients with multiple sclerosis. Adv. Ther. 2011, 28, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devonshire, V.; Lapierre, Y.; Macdonell, R.; Ramo-Tello, C.; Patti, F.; Fontoura, P.; Suchet, L.; Hyde, R.; Balla, I.; Frohman, E.M.; et al. The Global Adherence Project (GAP): A multicenter observational study on adherence to diseasemodifying therapies in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2011, 18, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, J.I.; Bergman, R.E.; Birnbaum, H.G.; Phillips, A.L.; Stewart, M.; Meletiche, D.M. Impact of medication adherence to disease-modifying drugs on severe relapse, and direct and indirect costs among employees with multiple sclerosis in the U.S. J. Med. Econ. 2012, 15, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamm, C.P.; Barin, L.; Gobbi, C.; Pot, C.; Calabrese, P.; Salmen, A.; Achtnichts, L.; Kesselring, J.; Puhan, M.A.; von Wyl, V. Swiss Multiple Sclerosis Registry (SMSR). Factors influencing patient satisfaction with the first diagnostic consultation in multiple sclerosis: A Swiss Multiple Sclerosis Registry (SMSR) study. J. Neurol. 2020, 267, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imanieh, M.H.; Mirahmadizadeh, A.; Imani, B. Factors affecting public dissatisfaction with urban family physician plan: A general population based study in Fars Province. Electron. Physician 2017, 9, 5676–5681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Irving, G.; Neves, A.L.; Dambha-Miller, H.; Oishi, A.; Tagashira, H.; Verho, A.; Holden, J. International variations in primary care physician consultation time: A systematic review of 67 countries. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e017902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzola, G.; Losiouk, E.; Del Favero, S.; Facchinetti, A.; Galderisi, A.; Quaglini, S.; Magni, L.; Cobelli, C. Remote Blood Glucose Monitoring in mHealth Scenarios: A Review. Sensors 2016, 16, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, F.A.C.; Dagostini, C.M.; Bicca, Y.A.; Falavigna, V.F.; Falavigna, A. Remote Patient Monitoring: A Systematic Review. Telemed. e-Health 2020, 26, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.L.; Thomas, E.E.; Snoswell, C.L.; Smith, A.C.; Caffery, L.J. Does remote patient monitoring reduce acute care use? A systematic review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e040232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, C.C.; Deyell, M.W. Remote Monitoring of Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices. Can. J. Cardiol. 2018, 34, 941–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.J.; Banwell, B.L.; Barkhof, F.; Carroll, W.M.; Coetzee, T.; Comi, G.; Correale, J.; Fazekas, F.; Filippi, M.; Freedman, M.S.; et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burks, J.; Marshall, T.S.; Ye, X. Adherence to disease-modifying therapies and ist impact on relapse, health resource utilization, and costs among patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin. Outcomes Res. 2017, 9, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, B.; Cowling, T.; Chen, G.; Yeung, M.; Duquette, P.; Haddad, P. The impact of treatment adherence on clinical and economic outcomes in multiple sclerosis: Real world evidence from Alberta, Canada. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2017, 18, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yermakov, S.; Davis, M.; Calnan, M.; Fay, M.; Cox-Buckley, B.; Sarda, S.; Duh, M.S.; Iyer, R. Impact of increasing adherence to disease-modifying therapies on healthcare resource utilization and direct medical and indirect work loss costs for patients with multiple sclerosis. J. Med. Econ. 2015, 18, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lizan, L.; Comellas, M.; Paz, S.; Poveda, J.L.; Meletiche, D.M.; Polanco, C. Treatment adherence and other patient-reported outcomes as cost determinants in multiple sclerosis: A review of the literature. Patient Pref. Adherence 2014, 8, 1653–1664. [Google Scholar]

- Heesen, C.; Bruce, J.; Feys, P.; Sastre-Garriga, J.; Solari, A.; Eliasson, L.; Matthews, V.; Hausmann, B.; Perrin Ross, A.; Asano, M.; et al. Adherence in multiple sclerosis (ADAMS): Classification, relevance, and research needs. A meeting report. Mult. Scler. 2014, 20, 1795–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholas, J.A.; Edwards, N.C.; Edwards, R.A.; Dellarole, A.; Grosso, M.; Phillips, A.L. Real-world adherence to, and persistence with, once- and twice-daily oral disease-modifying drugs in patients with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. 2020, 20, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, J.A.; Scheyer, R.D.; Mattson, R.H. Compliance declines between clinical visits. Arch. Intern. Med. 1990, 150, 1509–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).