Structure–Function Effect of Heat Treatment on the Interfacial and Foaming Properties of Mixed Whey Protein Isolate/Persian Gum (Amygdalus scoparia Spach) Solutions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Aqueous Solutions

2.2. Turbidity Measurement

2.3. DLS and Zeta-Potential Measurements

2.4. Measurements of the Dynamic Surface Tension and Surface Dilatational Rheology

2.5. Interfacial Shear Rheology at the Air/Water Surface

2.6. Bulk Viscosity Measurements

2.7. Measurements of the Hydrophobicity of Aggregated Proteins

2.8. Foam Properties

2.9. Image Analysis: Foam Bubble Size Distribution

2.10. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Influence of WPI/PG Interactions on Heat-Induced Protein Aggregation

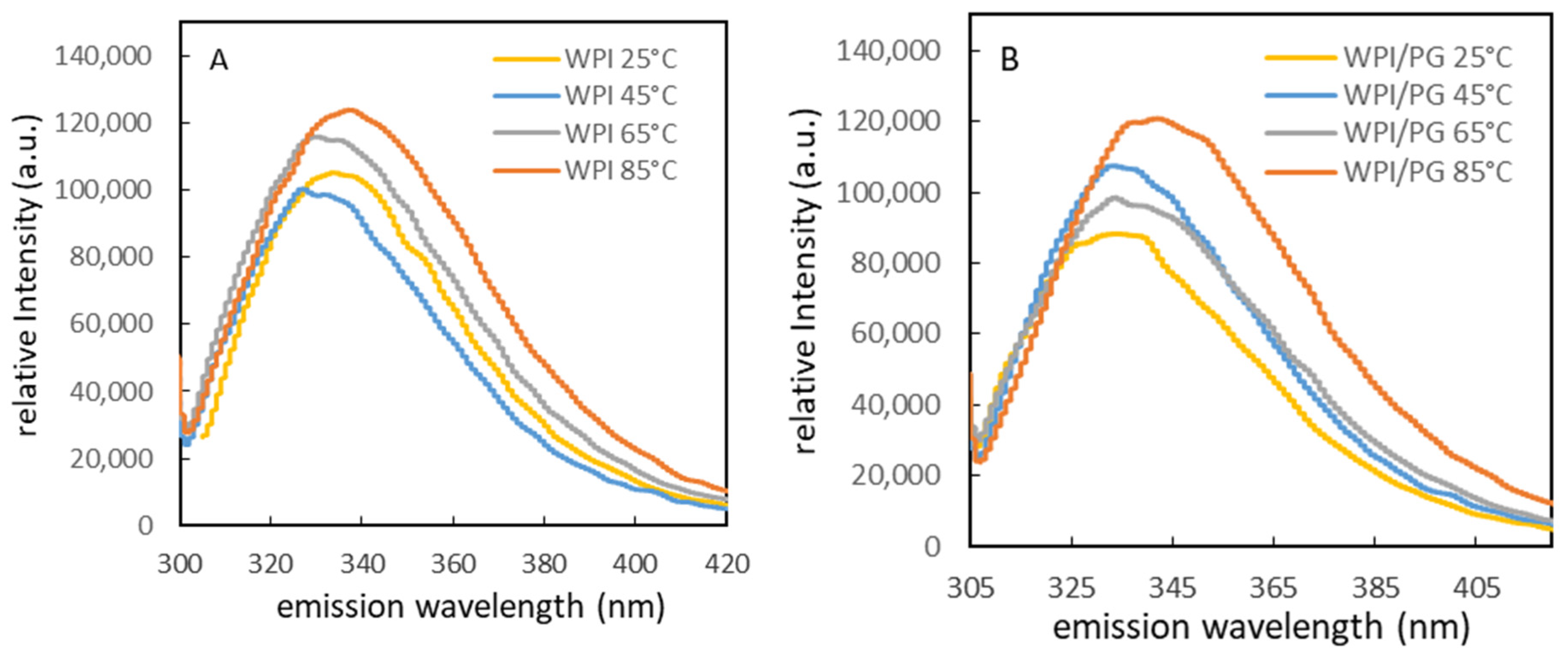

3.2. Influence of WPI/PG Interactions on Intrinsic Fluorescence

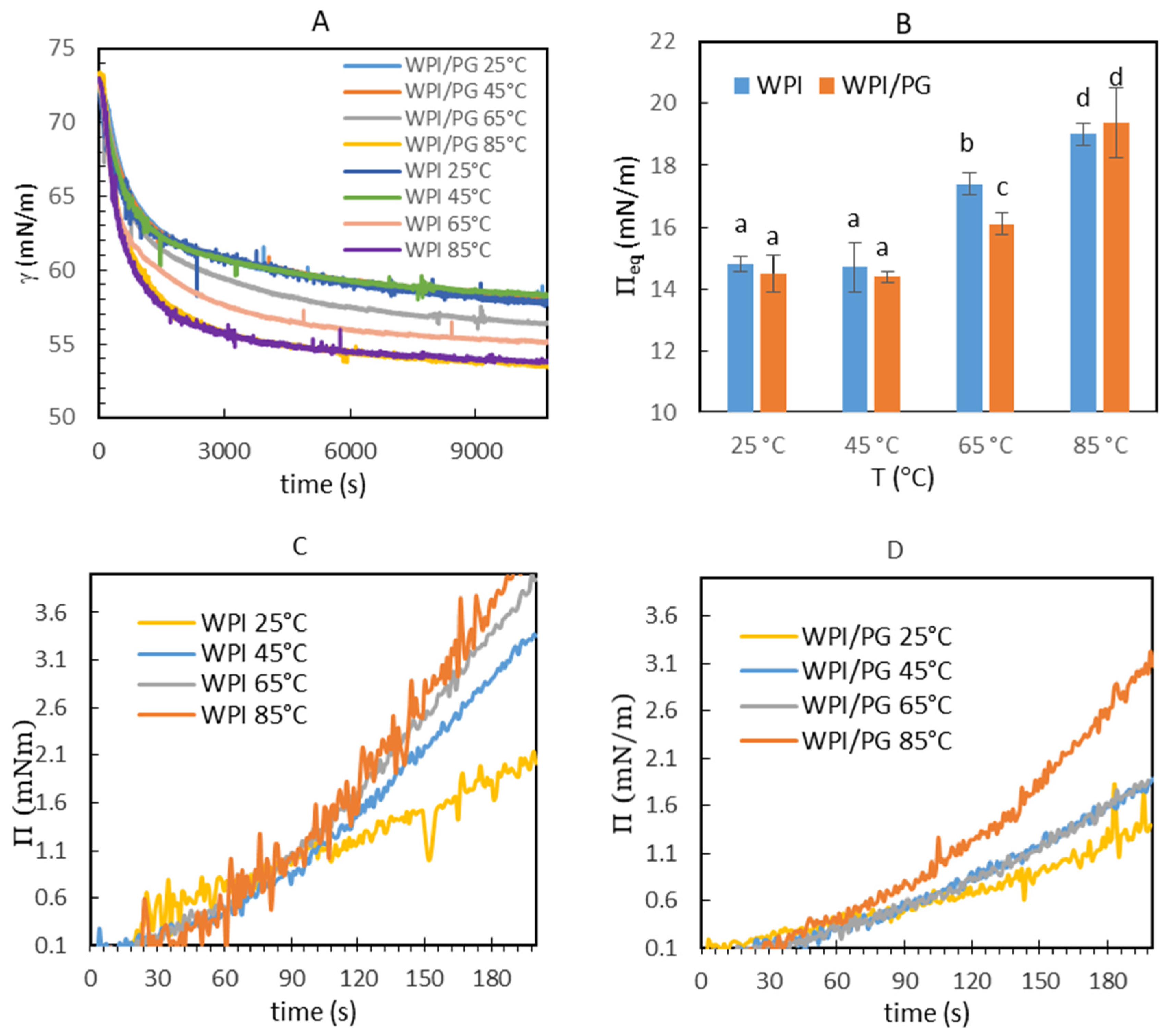

3.3. Dynamic Interfacial Properties of Mixed WPI/PG Solutions

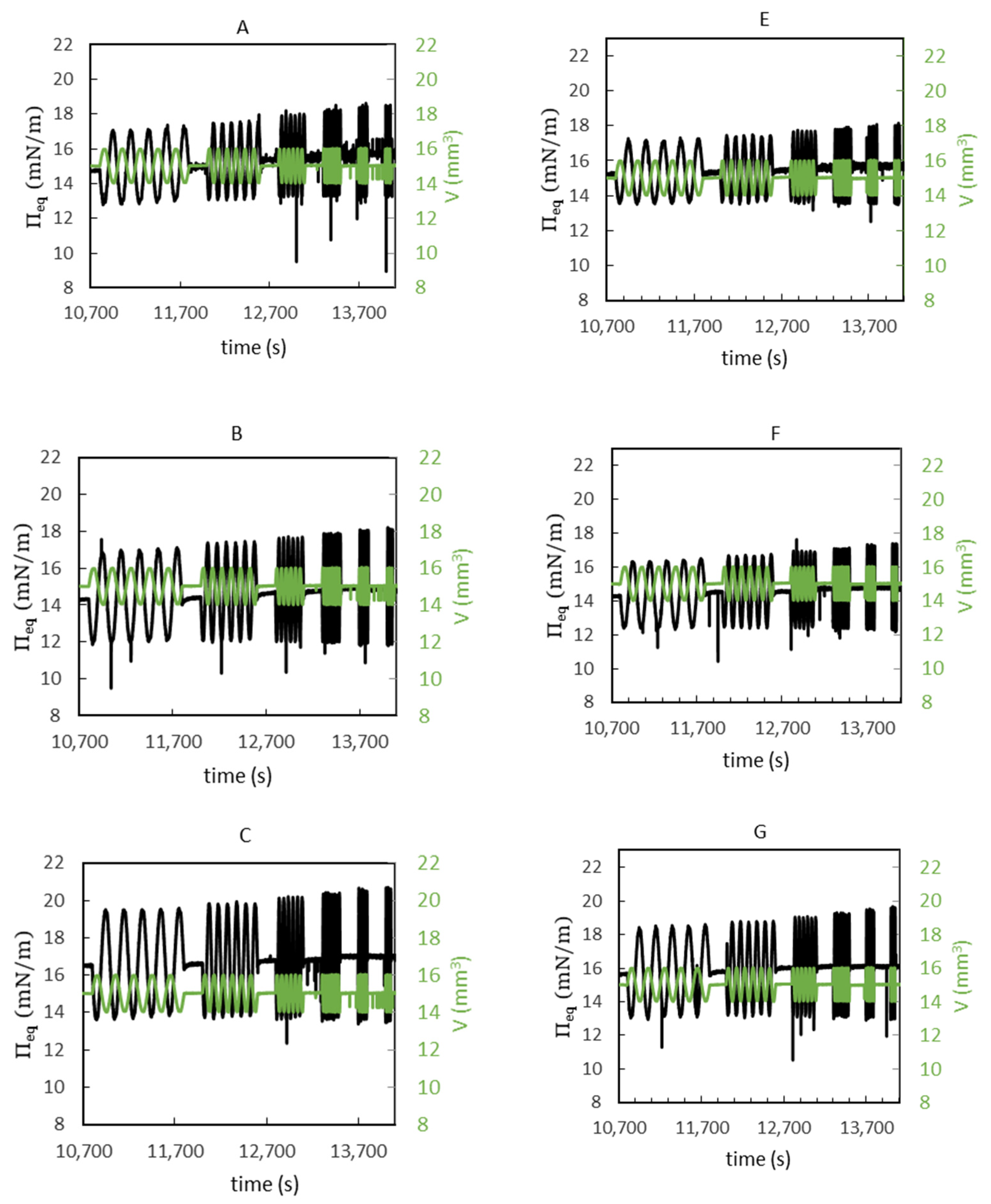

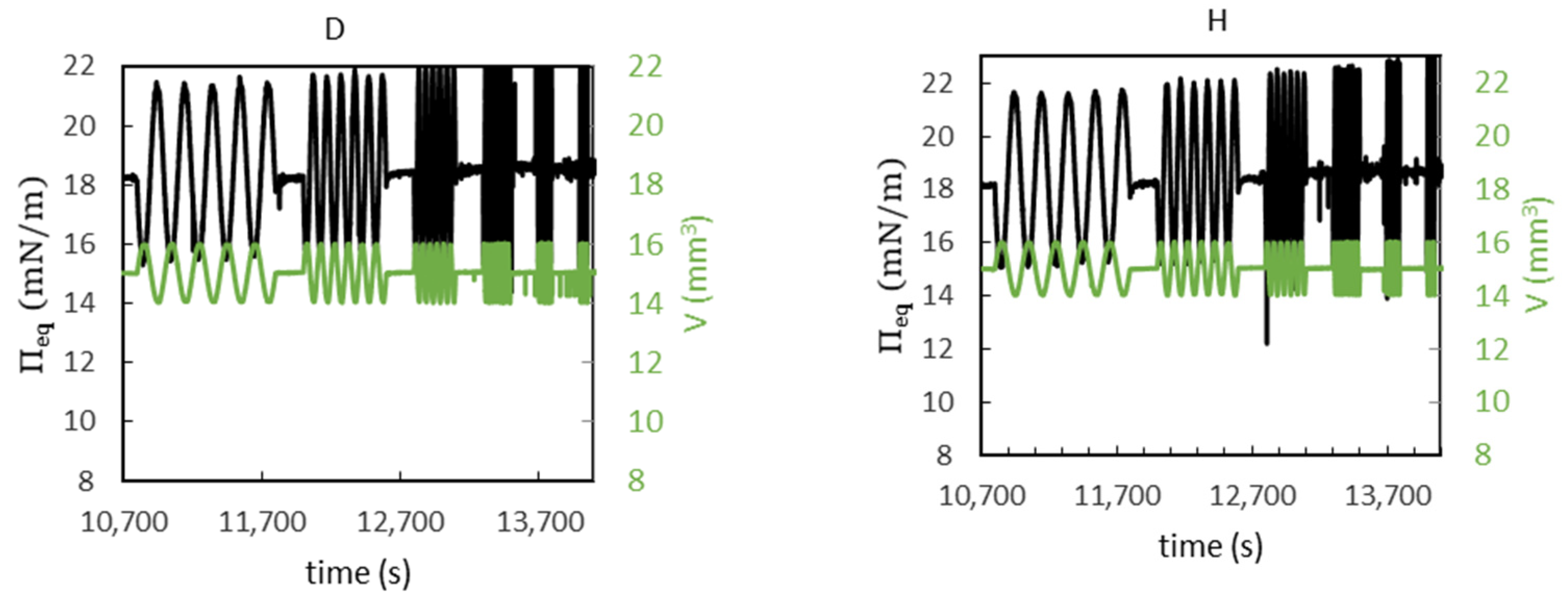

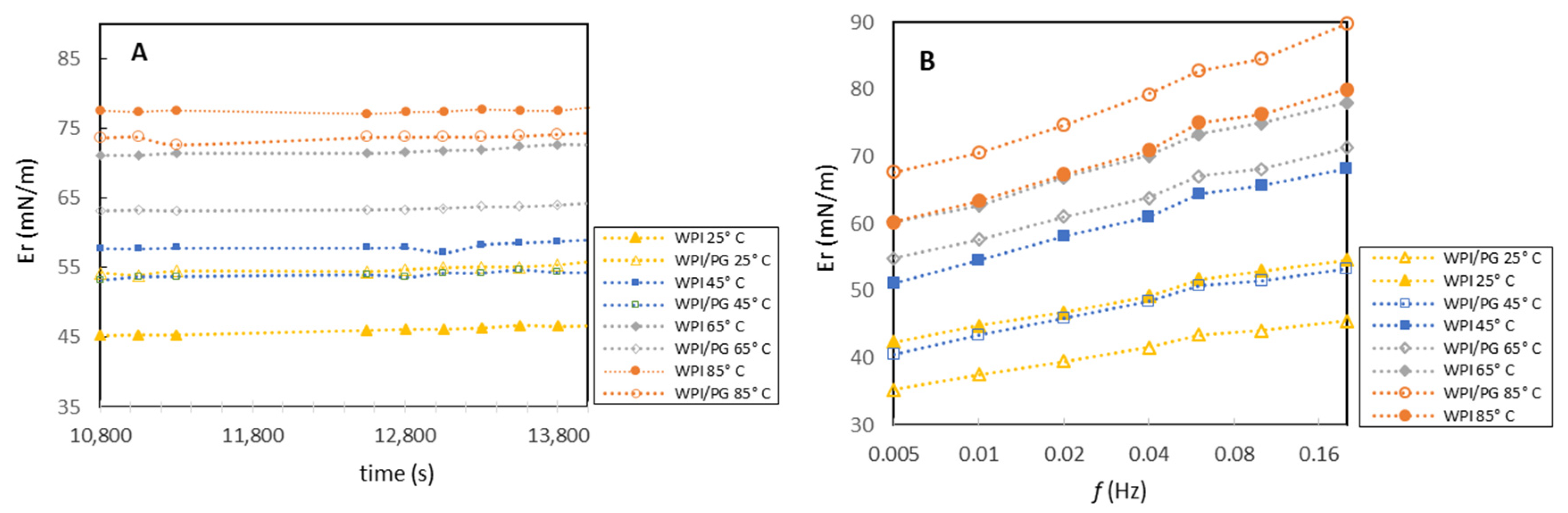

3.4. Interfacial Dilatational Rheology

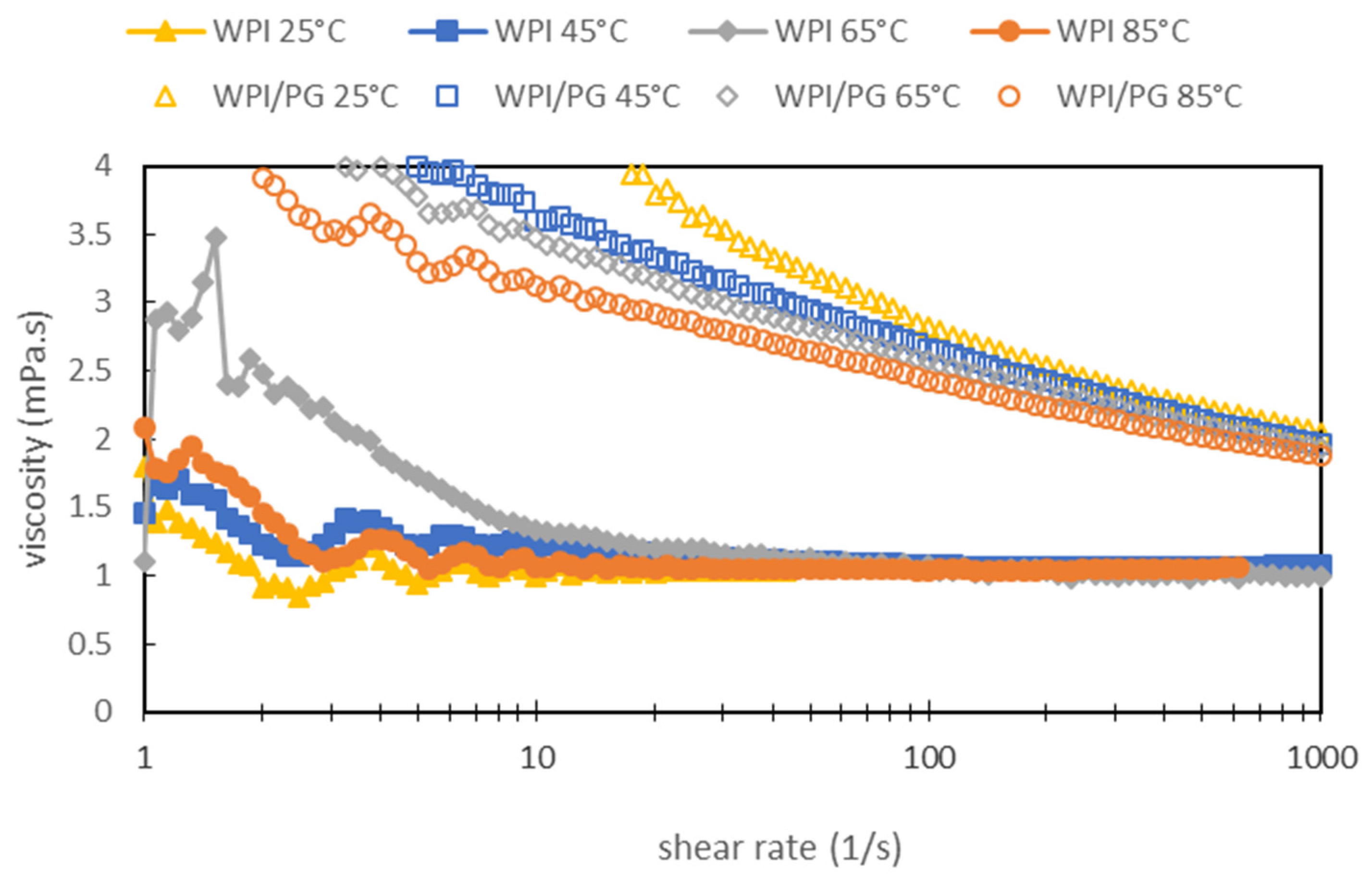

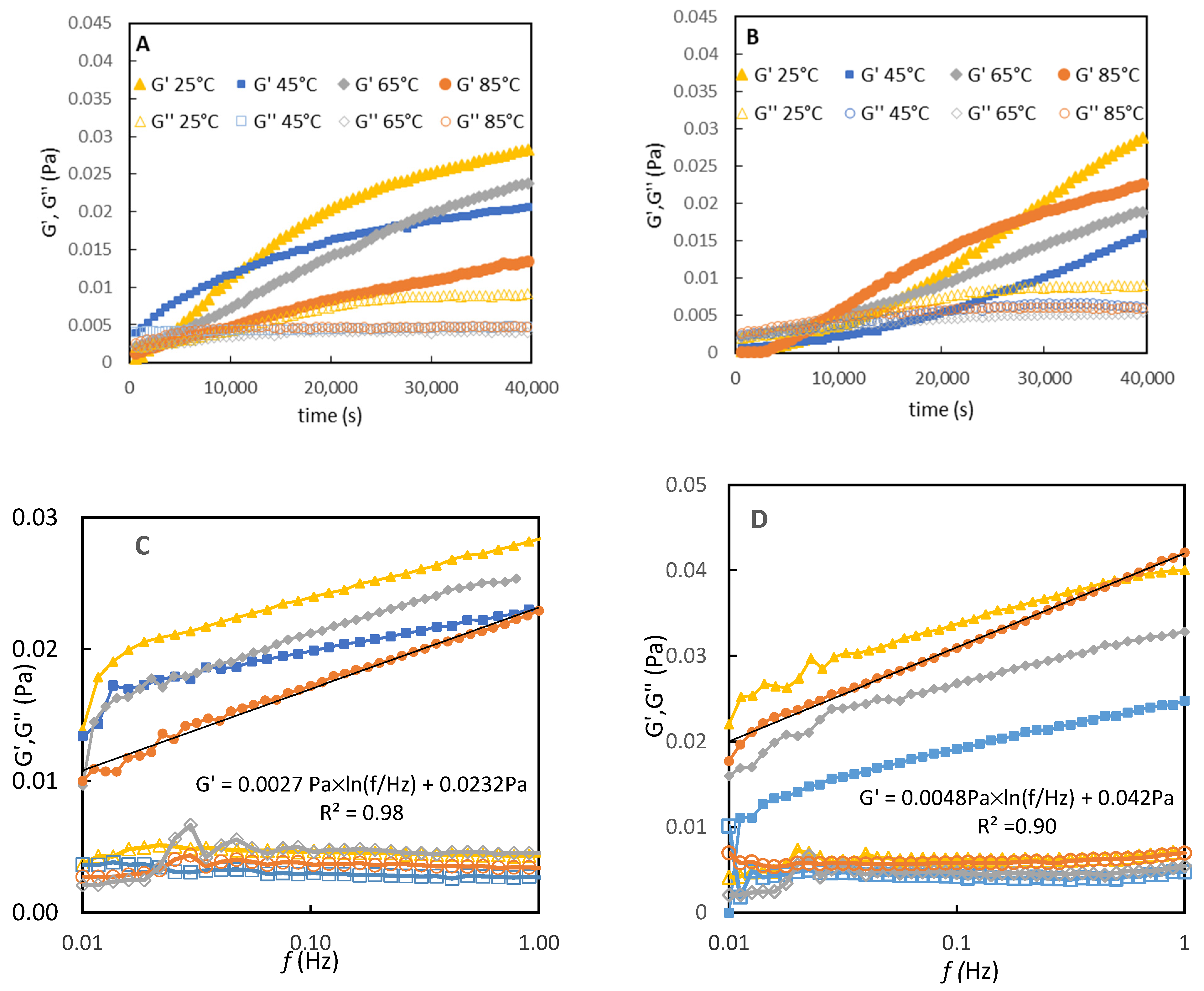

3.5. Interfacial Shear Rheology

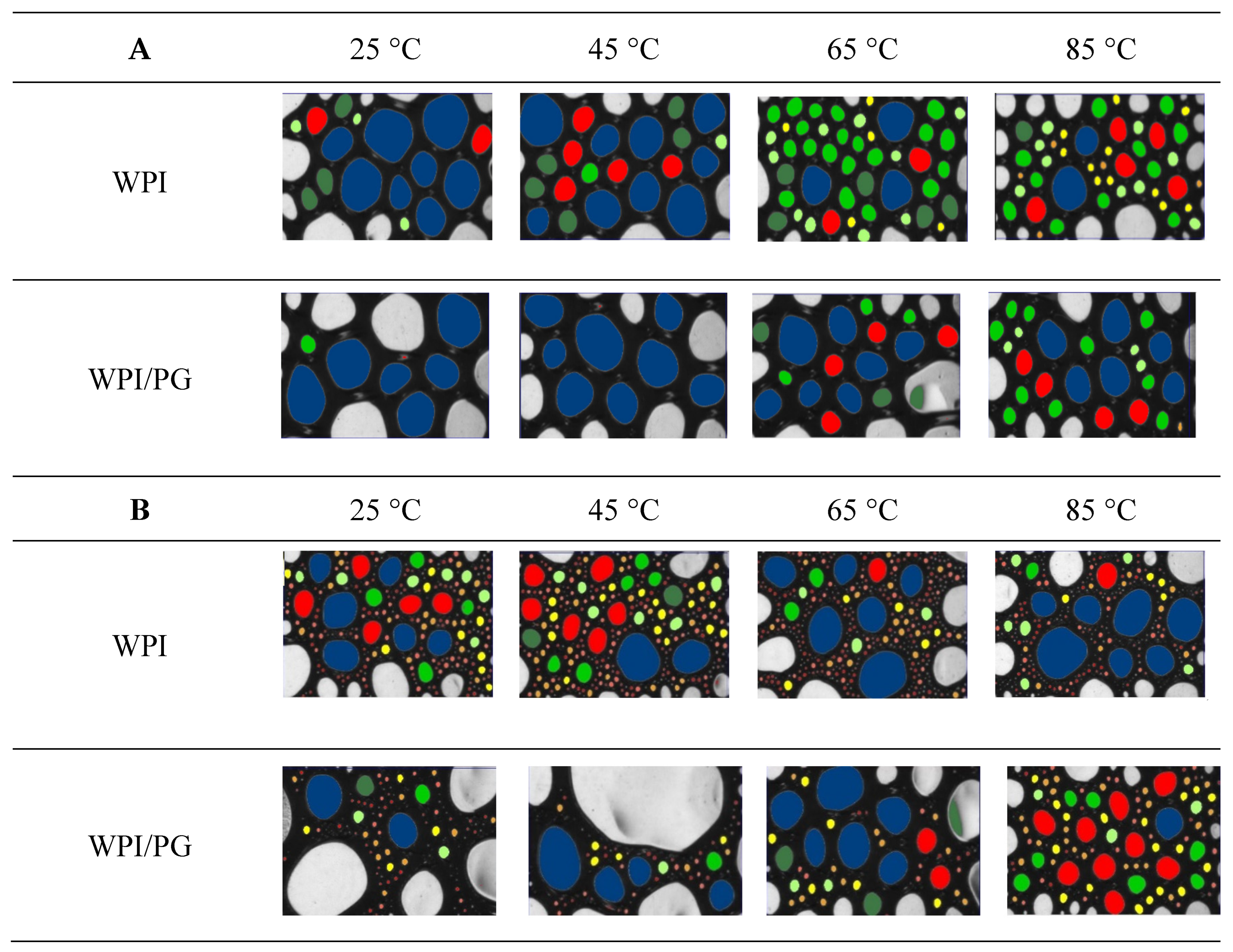

3.6. Foamability and Foam Stability

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benichou, A.; Aserin, A.A.; Garti, N. Protein-polysaccharide interactions for stabilization of food emulsions. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2002, 23, 93–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bealer, E.J.; Onissema-Karimu, S.; Rivera-Galletti, A.; Francis, M.; Wilkowski, J.; la Cruz, D.S.-D.; Hu, X. Protein–polysaccharide composite materials: Fabrication and applications. Polymers 2020, 12, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bealer, E.J.; Kavetsky, K.; Dutko, S.; Lofland, S.; Hu, X. Protein and polysaccharide-based magnetic composite materials for medical applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 12, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodea-González, D.A.; Cruz-Olivares, J.; Román-Guerrero, A.; Rodríguez-Huezo, M.E.; Vernon-Carter, E.J.; Pérez-Alonso, C. Spray-dried encapsulation of chia essential oil (Salvia hispanica L.) in whey protein concentrate-polysaccharide matrices. J. Food Eng. 2012, 111, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Song, C.; Zhang, S.; Ren, J.; Udenigwe, C.C. Maillard-Type Protein–Polysaccharide Conjugates and Electrostatic Protein–Polysaccharide Complexes as Delivery Vehicles for Food Bioactive Ingredients: Formation, Types, and Applications. Gels 2022, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernon-Carter, E. Viscoelastic properties and overall sensory acceptability of reduced-fat Petit-Suisse cheese made by replacing milk fat with complex coacervate. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2012, 92, 383–398. [Google Scholar]

- Laneuville, S.I.; Paquin, P.; Turgeon, S.L. Formula optimization of a low-fat food system containing whey protein isolate-xanthan gum complexes as fat replacer. J. Food Sci. 2005, 70, s513–s519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgeon, S.L.; Laneuville, S.I. Protein+ polysaccharide coacervates and complexes: From scientific background to their application as functional ingredients in food products. In Modern Biopolymer Science; Academis Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 327–363. [Google Scholar]

- Le, X.T.; Rioux, L.-E.; Turgeon, S.L. Formation and functional properties of protein–polysaccharide electrostatic hydrogels in comparison to protein or polysaccharide hydrogels. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 239, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstoguzov, V.B. Functional properties of food proteins and role of protein-polysaccharide interaction. Food Hydrocoll. 1991, 4, 429–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, C.; Sanchez, C.; Desobry-Banon, S.; Hardy, J. Structure and technofunctional properties of protein-polysaccharide complexes: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1998, 38, 689–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J. Food Emulsions: Principles, Practices, and Techniques; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann, L.; Beicht, M.; Reichert, C.; Weiss, J. Foaming properties of heat-aggregated microparticles from whey proteins. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 579, 123572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan-Xuan, T.; Durand, D.; Nicolai, T.; Donato, L.; Schmitt, C.; Bovetto, L. Heat induced formation of beta-lactoglobulin microgels driven by addition of calcium ions. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 34, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterhaslberger, G.; Schmitt, C.; Shojaei-Rami, S.; Sanchez, C. Lactoglobulin aggregates from heating with charged cosolutes: Formation, characterization and foaming. In Food Colloids: Self-Assembly and Material Science; RSC Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 175–191. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, R.W.; Farkas, B.E.; Jones, O.G. Dynamic and viscoelastic interfacial behavior of β-lactoglobulin microgels of varying sizes at fluid interfaces. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 466, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Damodaran, S. Heat-induced conformational changes in whey protein isolate and its relation to foaming properties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1994, 42, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnsilawat, T.; Pongsawatmanit, R.; McClements, D.J. Stabilization of model beverage cloud emulsions using protein− polysaccharide electrostatic complexes formed at the oil−water interface. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 5540–5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leman, J.; Dolgan, T. Effects of heating and pressurization on foaming properties of beta-lactoglobulin. Electron. J. Pol. Agric. Univ. 2004, 7, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Gräff, K.; Stock, S.; Mirau, L.; Bürger, S.; Braun, L.; Völp, A.; Willenbacher, N.; von Klitzing, R. Untangling effects of proteins as stabilizers for foam films. Front. Soft Matter. 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, C.; Bovay, C.; Rouvet, M. Bulk self-aggregation drives foam stabilization properties of whey protein microgels. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 42, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.A.; Carrara, C.R.; Sánchez, C.C.; Santiago, L.G.; Patino, J.M.R. Interfacial dynamic properties of whey protein concentrate/polysaccharide mixtures at neutral pH. Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 1253–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.A.; Sánchez, C.C.; Patino, J.M.R.; Rubiolo, A.C.; Santiago, L.G. Surface adsorption behaviour of milk whey protein and pectin mixtures under conditions of air–water interface saturation. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2011, 85, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, E. Hydrocolloids at interfaces and the influence on the properties of dispersed systems. Food Hydrocoll. 2003, 17, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, E.; Radford, S.J.; Golding, M. Stability and rheology of emulsions containing sodium caseinate: Combined effects of ionic calcium and non-ionic surfactant. Food Hydrocoll. 2003, 17, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza, R.; Sanchez, C.C.; Pilosof, A.M.R.; Patino, J.M.R. Interactions of polysaccharides with β-lactoglobulin adsorbed films at the air–water interface. Food Hydrocoll. 2005, 19, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza, R.; Carrera, C.; Patino, J.M.R.; Pilosof, A.M.R. Interactions between b-lactoglobulin and polysaccharides at the air-water interface and the influence on foam properties. In Food Colloids; RSC Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 301–316. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, M.; Aserin, A.; Ishai, P.B.; Garti, N. Interactions between whey protein isolate and gum Arabic. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2010, 79, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Rahimi, S. Persian gum. In Encyclopedia of Biomedical Polymers and Polymeric Biomaterials; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 5919–5928. [Google Scholar]

- Dabestani, M.; Yeganehzad, S. Effect of Persian gum and Xanthan gum on foaming properties and stability of pasteurized fresh egg white foam. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 87, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarikia, F.; Abbasi, S. Mechanism of soluble complex formation of milk proteins with native gums (tragacanth and Persian gum). Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 59, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadian, M.; Hosseini, S.M.H.; Farahnaky, A.; Mesbahi, G.R.; Yousefi, G.H.; Saboury, A.A. Isothermal titration calorimetric and spectroscopic studies of β-lactoglobulin-water-soluble fraction of Persian gum interaction in aqueous solution. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 55, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, S.M.; Beheshti, P.; Assadpoor, E. Rheological behavior and stability of D-limonene emulsions made by a novel hydrocolloid (Angum gum) compared with Arabic gum. J. Food Eng. 2012, 109, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardhanabhuti, B.; Yucel, U.; Coupland, J.N.; Foegeding, E.A. Interactions between β-lactoglobulin and dextran sulfate at near neutral pH and their effect on thermal stability. Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 1511–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, C.; Bovay, C.; Rouvet, M.; Shojaei-Rami, S.; Kolodziejczyk, E. Whey protein soluble aggregates from heating with NaCl: Physicochemical, interfacial, and foaming properties. Langmuir 2007, 23, 4155–4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppel, D.E. Analysis of macromolecular polydispersity in intensity correlation spectroscopy: The method of cumulants. J. Chem. Phys. 1972, 57, 4814–4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, R.J. Zeta Potential in Colloid Science: Principles and Applications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ganzevles, R.A.; Stuart, M.A.C.; van Vliet, T.; de Jongh, H.H.J. Use of polysaccharides to control protein adsorption to the air–water interface. Food Hydrocoll. 2006, 20, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.; Fainerman, V.B.; Makievski, A.V.; Krägel, J.; Grigoriev, D.O.; Kazakov, V.N.; Sinyachenko, O.V. Dynamics of protein and mixed protein/surfactant adsorption layers at the water/fluid interface. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2000, 86, 39–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, C.F.; Fuller, G.G.; Frank, C.W.; Robertson, C.R. An interfacial stress rheometer to study rheological transitions in monolayers at the air− water interface. Langmuir 1999, 15, 2450–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffe, J.F. Rheological Methods in Food Process Engineering; Freeman Press: Dallas, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Biviano, M.D.; Böni, L.J.; Berry, J.D.; Fischer, P.; Dagastine, R.R. Viscoelastic characterization of the crosslinking of β-lactoglobulin on emulsion drops via microcapsule compression and interfacial dilational and shear rheology. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 583, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghisaidoobe, A.B.T.; Chung, S.J. Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence in the detection and analysis of proteins: A focus on Förster resonance energy transfer techniques. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 22518–22538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühnhammer, M.; Widmann, T.; Kreuzer, L.P.; Schmid, A.J.; Wiehemeier, L.; Frielinghaus, H.; Jaksch, S.; Bögershausen, T.; Barron, P.; Schneider, H. Flexible sample environments for the investigation of soft matter at the European Spallation Source: Part III—The macroscopic foam cell. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.J.; Atwell, W.A. Starches; Eagan Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, A.; Takahashi, A.; Matsudomi, N.; Kobayashi, K. Determination of Foaming Properties of Proteins by Conductivity Measurements. J. Food Sci. 1983, 48, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanford, C.; Bunville, L.G.; Nozaki, Y. The reversible transformation of β-lactoglobulin at pH 7.51. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1959, 81, 4032–4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.L.; Brownlow, S.; Holt, C.; Sellers, P. Thermal denaturation of β-lactoglobulin: Effect of protein concentration at pH 6.75 and 8.05. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol. 1995, 1248, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, J.N. Thermal behaviour of bovine β-lactoglobulin at temperatures up to 150 C—A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 20, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havea, P.; Singh, H.; Creamer, L.K. Characterization of heat-induced aggregates of β-lactoglobulin, α-lactalbumin and bovine serum albumin in a whey protein concentrate environment. J. Dairy Res. 2001, 68, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, G.C.; Ottewill, R.H. Reversible aggregation Part I. Reversible flocculation monitored by turbidity measurements. Colloid Polym. Sci. 1988, 266, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Polozova, A. Biophysical Techniques for Protein Size Distribution Analysis. In Biophysics for Therapeutic Protein Development; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Vardhanabhuti, B.; Foegeding, E.A. Rheological properties and characterization of polymerized whey protein isolates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 3649–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinbreck, F.; Nieuwenhuijse, H.; Robijn, G.W.; de Kruif, C.G. Complex formation of whey proteins: Exocellular polysaccharide EPS B40. Langmuir 2003, 19, 9404–9410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalesi, H.; Emadzadeh, B.; Kadkhodaee, R.; Fang, Y. Whey protein isolate-Persian gum interaction at neutral pH. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 59, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, E.O.; Yeganehzad, S.; Hesarinejad, M.A.; Dabestani, M.; Schneck, E.; Miller, R. Effects of Various Types of Vacuum Cold Plasma Treatment on the Chemical and Functional Properties of Whey Protein Isolate with a Focus on Interfacial Properties. Colloids Interfaces 2023, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.Y.; Bewley, M.C.; Creamer, L.K.; Baker, H.M.; Baker, E.N.; Jameson, G.B. Structural basis of the Tanford transition of bovine b-lactoglobulin. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 14014–14023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantaloni, D. Etude de la Transition R to S de la Beta-Lactoglobuline par Spectropolarimetrie et par Spectrophotometrie de Differences. C. R. Hebd. Seances Acad Sci. 1964, 258, 5753. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perez, A.A.; Carrara, C.R.; Sánchez, C.C.; Patino, J.M.R.; Santiago, L.G. Interactions between milk whey protein and polysaccharide in solution. Food Chem. 2009, 116, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftink, M.R.; Ghiron, C.A. Fluorescence quenching studies with proteins. Anal. Biochem. 1981, 114, 199–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teale, F.W.J. The ultraviolet fluorescence of proteins in neutral solution. Biochem. J. 1960, 76, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patino, J.M.R.; Sanchez, C.C.; Niño, M.R.R. Implications of interfacial characteristics of food foaming agents in foam formulations. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2008, 140, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicorescu, I.; Riaublanc, A.; Loisel, C.; Vial, C.; Djelveh, G.; Cuvelier, G.; Legrand, J. Impact of protein self-assemblages on foam properties. Food Res. Int. 2009, 42, 1434–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möbius, D.; Miller, R. Proteins at Liquid Interfaces; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Erni, P.; Fischer, P.; Windhab, E.J.; Kusnezov, V.; Stettin, H.; Läuger, J. Stress-and strain-controlled measurements of interfacial shear viscosity and viscoelasticity at liquid/liquid and gas/liquid interfaces. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2003, 74, 4916–4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelebioğlu, H.Y.; Kmiecik-Palczewska, J.; Lee, S.; Chronakis, I.S. Interfacial shear rheology of β-lactoglobulin—Bovine submaxillary mucin layers adsorbed at air/water interface. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 102, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronteltap, A.D.; Damsté, B.R.; De Gee, M.; Prins, A. The role of surface viscosity in gas diffusion in aqueous foams. I. Theoretical. Colloids Surf. 1990, 47, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walstra, P. Principles of Foam Formation and Stability. In Foams: Physics, Chemistry and Structure; Wilson, A., Ed.; Springer: Londin, UK, 1989; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, E. Interfacial, emulsifying and foaming properties of milk proteins. In Advanced Dairy Chemistry: Volume 1: Proteins, Parts A&B; Fox, P.F., McSweeney, P.L.H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 1229–1260. [Google Scholar]

- Damodaran, S. Protein stabilization of emulsions and foams. J. Food Sci. 2005, 70, R54–R66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, E. Adsorbed protein layers at fluid interfaces: Interactions, structure and surface rheology. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 1999, 15, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, M.A.; Van Vliet, T. Interfacial rheological properties of adsorbed protein layers and surfactants: A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2001, 91, 437–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühnhammer, M.; Gräff, K.; Loran, E.; Soltwedel, O.; Löhmann, O.; Frielinghaus, H.; von Klitzing, R. Structure formation of PNIPAM microgels in foams and foam films. Soft Matter 2022, 18, 9249–9262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bals, A.; Kulozik, U. Effect of pre-heating on the foaming properties of whey protein isolate using a membrane foaming apparatus. Int. Dairy J. 2003, 13, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croguennec, T.; Renault, A.; Bouhallab, S.; Pezennec, S. Interfacial and foaming properties of sulfydryl-modified bovine β-lactoglobulin. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2006, 302, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rullier, B.; Novales, B.; Axelos, M.A.V. Effect of protein aggregates on foaming properties of β-lactoglobulin. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2008, 330, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besagni, G.; Inzoli, F.; De Guido, G.; Pellegrini, L.A. The dual effect of viscosity on bubble column hydrodynamics. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2017, 158, 509–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| WPI | WPI/PG | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (°C) | * Size (nm) | PDI | Absorbance | ζ-Potential (mV) | * Size (nm) | PDI | Absorbance | ζ-Potential (mV) |

| 25 | 109 | 0.6 | 0.1 | −26 ± 2 | 242 | 0.4 | 0.14 | −27 ± 2 |

| 45 | 270 | 0.5 | 0.14 | −26 ± 1 | 197 | 0.4 | 0.11 | −28 ± 1 |

| 65 | 308 | 0.5 | 0.15 | −25 ± 2 | 170 | 0.5 | 0.13 | −28 ± 2 |

| 85 | 294 | 0.4 | 0.13 | −27 ± 2 | 197 | 0.4 | 0.08 | −28 ± 2 |

| A | (mL) | (μS) | (s) | (s) | (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WPI-25 °C | 160.6 ± 5 a | 6.7 ± 0.3 a | 374.6 ± 123 a | 35.3 ± 4 a | 38.3 ± 6 a |

| WPI-45 °C | 168.7 ± 3 b | 10.0 ± 1.1 b | 775.6 ± 140 b | 43.6 ± 2 b | 51.0 ± 7 b |

| WPI-65 °C | 170.6 ± 5 b | 12.2 ± 0.4 c | 624.6 ± 121 b | 51.6 ± 3 c | 73.0 ± 4 c |

| WPI-85 °C | 191.0 ± 37 c | 14.8 ± 0.6 d | 280.0 ± 78 a | 55.6 ± 5 d | 72.0 ± 9 c |

| WPI/PG-25 °C | 167.0 ± 7 b | 9.2 ± 3.0 b | 684.6 ± 375 b | 37.0 ± 3 a | 38.3 ± 4 a |

| WPI/PG-45 °C | 172.0 ± 5 b | 14.1 ± 1.0 d | 1444.0 ± 234 d | 40.0 ± 2 b | 36.0 ± 3 a |

| WPI/PG-65 °C | 171.0 ± 4 b | 21.5 ± 3.0 e | 607.3 ± 150 b | 46.3 ± 3 c | 48.4 ± 4 b |

| WPI/PG-85 °C | 175.0 ± 6 c | 21.0 ± 2.0 e | 399.7 ± 100 a | 49.6 ± 6 c | 57.6 ± 4 d |

| B | (mL) | (μS) | (s) | (s) | (s) |

| WPI-25 °C | 232.0 ± 1.1 a | 116.2 ± 8 a | 1487.0 ± 240 a | 66.3 ± 1.5 a | 142.6 ± 1.5 a |

| WPI-45 °C | 232.0 ± 0.5 a | 102.7 ± 4.3 b | 1290.0 ± 24 b | 69.6 ± 7.6 b | 143.0 ± 7.9 a |

| WPI-65 °C | 231.6 ± 0.5 a | 101.3 ± 2.7 b | 874.6 ± 13.6 c | 89.0 ± 4.0 c | 184.0 ± 6.0 b |

| WPI-85 °C | 232.0 ± 0.5 a | 117.3 ± 3.8 a | 668.3 ± 12.3 d | 75.3 ± 11.7 d | 186 ± 6.5 b |

| WPI/PG-25 °C | 225.0 ± 0.6 b | 84.8 ± 11.8 c | 1238.6 ± 68.9 b | 47.3 ± 6.0 e | 90.3 ± 2.0 c |

| WPI/PG-45 °C | 232.6 ± 0.5 a | 92.4 ± 2.8 d | 1851.0 ± 141 e | 62.0 ± 7.0 b | 93.3 ± 9.2 c |

| WPI/PG-65 °C | 231.0 ± 0.4 a | 96.2 ± 7.8 d | 972.0 ± 28 f | 51.6 ± 4.7 f | 87.3 ± 11.0 c |

| WPI/PG-85 °C | 232.0 ± 0.0 a | 83.9 ± 4.5 c | 376.0 ± 13 g | 48.6 ± 6.4 e | 76.3 ± 6.0 d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ommat Mohammadi, E.; Yeganehzad, S.; von Klitzing, R.; Miller, R.; Schneck, E. Structure–Function Effect of Heat Treatment on the Interfacial and Foaming Properties of Mixed Whey Protein Isolate/Persian Gum (Amygdalus scoparia Spach) Solutions. Colloids Interfaces 2026, 10, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids10010002

Ommat Mohammadi E, Yeganehzad S, von Klitzing R, Miller R, Schneck E. Structure–Function Effect of Heat Treatment on the Interfacial and Foaming Properties of Mixed Whey Protein Isolate/Persian Gum (Amygdalus scoparia Spach) Solutions. Colloids and Interfaces. 2026; 10(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids10010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleOmmat Mohammadi, Elham, Samira Yeganehzad, Regine von Klitzing, Reinhard Miller, and Emanuel Schneck. 2026. "Structure–Function Effect of Heat Treatment on the Interfacial and Foaming Properties of Mixed Whey Protein Isolate/Persian Gum (Amygdalus scoparia Spach) Solutions" Colloids and Interfaces 10, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids10010002

APA StyleOmmat Mohammadi, E., Yeganehzad, S., von Klitzing, R., Miller, R., & Schneck, E. (2026). Structure–Function Effect of Heat Treatment on the Interfacial and Foaming Properties of Mixed Whey Protein Isolate/Persian Gum (Amygdalus scoparia Spach) Solutions. Colloids and Interfaces, 10(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids10010002