1. Introduction

CO

2 emissions are complex due to the interactions of multiple factors, including economic activity, technological innovation, policy interventions, and seasonal consumption variations. Therefore, the process of handling data has to be comprehensive enough to catch nonlinear temporal dependencies, even over extended periods of time [

1].

Traditional statistical methods have their place in revealing the emissions trends, but they have limitations when confronted with high-dimensional, non-stationary characteristics typical of modern environmental data [

2,

3].

Deep learning technologies have significantly transformed the face of time series forecasting. The main features of these technologies include automated feature extraction and complex pattern recognition, which are difficult or impossible with previous traditional methods [

4,

5]. Out of different recurrent neural network architectures, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks [

6] and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) [

7] are most compelling for this application. They model temporal dependencies similarly to traditional methods, but they use a more complex gating mechanism to make the storage and retrieval of information more selective, thus enabling them to handle longer sequences [

8,

9,

10,

11].

From a practical perspective, these architectures can be viewed as extensions of familiar regression models that have been adapted to handle sequences instead of isolated data points. LSTM and GRU networks keep a short memory of past values and update it at each time step, deciding what information to keep or discard through their gates. CNN–LSTM models first use convolutional filters to detect local patterns such as seasonal cycles or short-lived shocks before feeding a summarized sequence into an LSTM layer. Finally, the Dense Neural Network (DNN) baseline treats each input window as a static feature vector, which is intuitive but ignores the ordering of observations over time. This section-by-section comparison aims to guide readers who may not specialize in deep learning by connecting each architecture to its intuitive role in forecasting CO2 emissions.

Though researchers have made significant progress with their methodologies, there are still many gaps in the research. One such gap is that there are very few studies that comprehensively compare various deep learning architectures using the same datasets and standardized evaluation protocols, specifically in the context of long-term emissions forecasting [

11,

12]. Additionally, existing research that analyzes forecasting performance across different prediction horizons is limited and often focuses on a single short-term horizon, providing insufficient practical guidance for policy planning that requires multiple temporal perspectives [

13,

14]. Computational efficiency issues such as training time, inference speed, and memory requirements are typically mentioned only briefly or treated as secondary aspects, despite their importance for deployment in low-resource institutional environments [

15,

16]. Moreover, proper statistical significance testing of performance differences between architectures is very seldom carried out, which reduces confidence that the chosen models are truly superior [

13,

17].

One of the significant changes concerning the use of transformer architectures [

18] came about through the application of attention-based methods for time series forecasting. This method has been extensively used, especially in climate prediction [

19,

20] and carbon emissions monitoring [

17,

21]. Even though transformers excel in capturing long-range dependencies, their high computational complexity and large data requirements still hinder them from being widely used. Because of the trade-off between efficiency and performance, hybrid models that combine convolutional and recurrent components have been proposed [

22,

23]. However, such models are still not fully subjected to systematic evaluations in different forecasting scenarios.

Taken together, these limitations define the starting point for this study: there is a need for a unified experimental setting in which multiple deep learning architectures are evaluated on the same multivariate CO2 emissions data, across several policy-relevant forecasting horizons, with both accuracy and computational aspects assessed in a statistically rigorous way. Our objective is therefore to (i) provide a standardized, multivariate comparison of four widely used architectures (LSTM, GRU, CNN–LSTM, and DNN) on the U.S. EIA dataset, (ii) analyze how their performance degrades with increasing forecast horizon at both aggregate and category levels, and (iii) examine statistical significance and computational efficiency to derive practical model selection guidance for emissions forecasting. The fundamental contributions of our research are as follows:

Conducting a rigorously standardized multivariate comparison of four deep neural architectures (LSTM, GRU, CNN–LSTM, and DNN) on a 52-year, eight-category CO2 emissions dataset from the U.S. EIA, using identical preprocessing, training, and evaluation protocols.

Evaluating forecasting performance across five policy-relevant horizons (1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months ahead), and analyzing how accuracy degrades with the horizon for both aggregate and category-level emissions.

Providing detailed, category-specific results that reveal how different architectures respond to varying pattern complexities (e.g., stable vs. volatile emission sources).

Combining forecasting accuracy with statistical significance testing and residual diagnostics to assess whether observed differences between architectures are robust.

Comparing computational efficiency (training time, parameter counts, convergence behavior, and inference considerations) to derive practical guidance on model selection for resource-constrained environmental and policy applications.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work on statistical and deep learning methods for emissions forecasting.

Section 3 presents the research methodology.

Section 4 reports the experimental results across the various evaluation dimensions.

Section 5 provides a detailed discussion of the findings and their potential policy implications.

Section 6 concludes the study and outlines future directions for deep learning–based environmental forecasting research.

2. Deep Learning Applications to Emissions Forecasting: Related Work

In this section, the goal is not only to list prior work but also to explain how different model families (statistical, recurrent, convolutional, and transformer-based) contribute to emissions forecasting. To support readers who may not be familiar with all these architectures, each group of methods is briefly characterized in terms of what kind of patterns it can capture and what trade-offs it introduces.

Deep learning has rapidly become the leading paradigm that prevails over all other traditional methods for forecasting the emission of CO

2. The statistical and econometric models that were considered the main approach just a couple of years ago have been surpassed by deep learning methods in terms of their accuracy, adaptability, and scope. Their main advantage is their ability to effectively model the nonlinear and dynamic relationships between emissions and different types of drivers like economic activity, technological change, energy structure, and policy interventions [

24,

25].

Early research surveys significantly influenced the theoretical and empirical grounds of such improvements, pointing out how the use of hierarchical feature learning on high-dimensional datasets made the automated discovery of patterns possible [

4,

5]. This established the superiority of deep learning in time series analysis in environmental sciences, where interactions between several factors are often nonlinear and non-stationary.

2.1. Recurrent Neural Network Models

Several studies demonstrate that recurrent neural networks (RNNs) significantly outperform statistical models in emissions and energy-demand forecasting [

10,

11]. LSTM-based approaches, in particular, have been shown to capture daily and seasonal cycles in energy demand, heating and cooling requirements, and transportation, thereby modeling recurring patterns that traditional ARIMA-type models often miss [

12]. Their reliability is especially evident under structural changes—policy shifts, energy crises, or pandemic disruptions—where classical time series models typically perform poorly [

2,

26]. Similar advantages have been observed in related air-quality and environmental monitoring applications, where LSTMs handle non-stationary time series more effectively than conventional methods [

14].

Efficiency aspects also affect the spread of recurrent model usage. GRUs, designed as a simplified and more efficient alternative to LSTMs, tend to provide almost the same accuracy as LSTMs but at a significantly lower training cost. For example, in [

15], the authors reported that GRUs achieve more than 90% of LSTM forecasting accuracy while using substantially less training time, which is critical for operational forecasting systems that must be retrained frequently. Subsequent works highlight the relevance of GRUs in climate-resilient and operational monitoring settings, where deployment constraints and robustness are central [

27]. However, most of these studies evaluate a single recurrent architecture or compare models on different datasets and preprocessing procedures, which makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions about their relative strengths and weaknesses.

2.2. Hybrid CNN–LSTM Models

Compared to purely recurrent models, hybrid architectures show significant growth in emissions-related forecasting. Such models exploit the combined strengths of different methods, allowing them to capture both short-term local changes and long-term trends. A prominent example is the CNN–LSTM model, which uses convolutional layers to extract local features and LSTM layers for sequence modeling, leading to strong performance in power consumption and energy load forecasting [

22,

23]. These hybrids are particularly appealing when emissions are driven by both abrupt local fluctuations and smoother structural shifts.

Despite their promise, hybrid models in the emissions domain are often investigated on narrow case studies with varying data resolutions, feature sets, and evaluation protocols. As a result, it remains unclear whether their additional complexity consistently translates into better performance than well-tuned recurrent baselines—especially when computational cost and implementation effort are taken into account. Systematic comparisons of hybrid CNN–LSTM models against simpler architectures under a unified multivariate setup are still scarce.

2.3. Transformer-Based and Attention Models

The use of transformer architectures is a more recent innovation. Initially designed for natural language processing (NLP), transformers leverage attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies without relying on strictly sequential processing [

18]. Sparse or probabilistic attention variants, such as the Informer model, have been proposed to reduce the computational burden of long sequence forecasting [

19]. Impressive accuracy has been achieved in emission-related studies using hybrid transformers, including power sector data and multi-scale decomposition of environmental signals [

17,

21].

Many new emissions prediction methods employ modeling approaches that explicitly connect climate and environmental variables. For example, in [

16], the authors demonstrated that dataset granularity and feature engineering critically influence the relative performance of deep architectures, while ref. [

28] show that transformer-based hybrids can better capture multivariate dependencies in complex climate systems. At the same time, the focus on explainability has led to attention-based and transparent transformer designs [

20], which are especially suitable in policy contexts where decision-support systems must be interpretable to non-technical stakeholders.

Transfer learning represents another emerging area. Research demonstrates that LSTM encoders pre-trained on energy time series can be adapted to different sectors or regions with limited local historical data, accelerating model deployment in data-scarce environments. Tzoumpas et al. [

24] propose CNN–(Bi)LSTM frameworks for data filling in emissions-like sequences, while the core ideas of sequence generation from recurrent networks [

25] underpin many of these advances. This line of work suggests that deep models can provide value even in settings with incomplete or noisy emissions records.

However, across recurrent, hybrid, and transformer-based studies, several methodological issues often remain. Many works report results on retrospective test sets without considering how continuous policy and structural changes may affect real-world performance. Recalibration strategies—crucial for maintaining accuracy when emission drivers evolve—are rarely analyzed in depth. Interpretability, although increasingly discussed, is still a limiting factor, with policymakers often hesitant to rely on opaque models [

13]. Furthermore, challenges such as hyperparameter sensitivity, high computational cost, and difficulty in integrating domain knowledge persist [

3,

29,

30].

Overall, the existing literature demonstrates that deep learning models can outperform traditional statistical baselines in CO

2 emissions forecasting, but it also reveals several shortcomings that motivate the present study. Most recurrent and hybrid models are evaluated in isolation or on different datasets and preprocessing pipelines, which makes it difficult to draw fair conclusions about their relative strengths [

11,

12]. Studies that do consider multiple horizons often focus on short-term prediction or do not systematically analyze how performance degrades as the horizon increases [

13,

14]. Furthermore, computational efficiency and formal statistical tests tend to be underreported, even though they are crucial for selecting models in operational settings [

15,

17]. These gaps directly shape our objectives: to compare four architectures under a unified multivariate setup, to study horizon-dependent behavior, and to jointly examine accuracy, statistical significance, and efficiency on a common long-term emissions dataset.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Problem Formulation

CO

2 emission forecasting is formulated as a multivariate time series prediction problem. Given a historical time series dataset (Equation (

1)).

where each observation

represents a

d-dimensional vector of emission sources at time step

t, and

represents the total number of monthly observations from January 1973 to May 2025. The objective is to learn a mapping function

f:

that predicts future emission values (Equation (

2)):

where

w is the input window size (lookback period),

h is the forecasting horizon (prediction steps ahead), and

represents the predicted emission values for the target category.

In simpler terms, the model receives a sliding window of w consecutive months of emissions for multiple categories and learns to predict the next h months for a selected target category. This setup reflects how practitioners typically work with rolling historical windows to produce forecasts for short-, medium-, or long-term planning horizons. The multivariate nature of means that the model can exploit interactions between different emission sources (for example, between coal and total energy emissions) rather than treating each series in isolation.

For this study, we adopt the monthly energy review data of the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), a dataset containing temporal observations of CO

2 emissions from various sources from January 1973 to May 2025. The dataset has 629 consecutive monthly measurements of 8 different emission source categories, capturing the multidimensional nature of the U.S. carbon emission pattern spanning over 52 years in the energy sector [

31]. It represents aggregated emission data in million metric tons of CO

2.

The dataset consists of the following emission categories:

Coal (Including Coal Coke Net Imports) CO2 Emissions.

Natural Gas (without the supplementary gaseous fuels) CO2 Emissions.

Aviation Gasoline CO2 Emissions

Distillate Fuel Oil (Without Biodiesel) CO2 Emissions.

Jet Fuel CO2 Emissions.

Motor Gasoline (without ethanol) CO2 Emissions.

Petroleum (without biofuels) CO2 Emissions.

Total Energy CO2 Emissions

For the empirical analysis, all eight categories are included in the multivariate input so that the models can exploit interactions across sectors. However, in the detailed per-category tables and figures in

Section 4, we focus on six representative categories that cover the main petroleum consumption sectors and the aggregate total. This selection is made to keep the presentation interpretable and avoid an overload of nearly redundant plots.

This comprehensive categorization enables tracking the emission patterns in various petroleum consumption sectors and also understanding the structural changes in the U.S. energy system over the past five decades. The dataset varies greatly for different emission categories. Values range from 0.001 million metric tons for a minor aviation gasoline emissions category to 557.5 million metric tons for total energy emissions. This wide dynamic range poses challenges for neural network modeling, but at the same time, this allows all categories to be trained effectively through proper normalization procedures.

The problem is evaluated across five prediction horizons

steps ahead to assess model performance for different planning timeframes: short-term operational monitoring (1–3 months), medium-term budget planning (6–12 months), and long-term strategic policy applications (24 months). The optimization objective is to minimize the prediction error across all forecasting horizons (Equation (

3)),

where

represents the model parameters,

N is the number of training samples,

is the loss function (Mean Squared Error), and

are the predicted and true values for sample

i.

3.2. Notation

For clarity and consistency,

Table 1 provides a comprehensive reference of all mathematical notation used throughout this paper. The symbols are organized by category to facilitate quick reference during technical sections.

3.3. Data Preprocessing Pipeline

The preprocessing pipeline is the first major step that transforms the raw EIA dataset into sequences suitable for training neural networks. Conceptually, this pipeline mirrors how an analyst would clean and reshape data before fitting any forecasting model. It consists of three sequential operations: (1) min–max normalization for numerical stability, (2) sliding-window generation to create supervised input–output pairs, and (3) temporal splitting into training, validation, and test sets to enable fair performance evaluation.

The preprocessing steps are presented in Algorithm 1, which describes step-by-step the conversion of raw time series into normalized training sequences suitable for input from the neural network.

The first step is normalization, where each emission category is individually rescaled to the range . For each feature j, the minimum and maximum values across all time steps are determined, and then the transformation is applied.

This normalization step ensures that variables with very different scales, such as aviation gasoline and total energy emissions, contribute comparably during training instead of allowing the largest-magnitude series to dominate the learning process.

The choice of window size w was guided by both domain and empirical considerations. In particular, w was selected to cover at least one full seasonal cycle while keeping the input dimensionality manageable, so that the models can exploit recurring monthly patterns without incurring excessive computational cost. To avoid data leakage, the min–max normalization parameters (per-feature minima and maxima) are computed exclusively on the training portion of the data, and the same scaling is then applied to the validation and test sets.

The second step, sliding window generation, produces overlapping input-output pairs for supervised learning. If window size w (lookback period) and h, the forecasting horizon (prediction steps ahead), are given, then the number of generated sequences will be . A sequence consists of w consecutive normalized observations, and its corresponding target contains the next h values of the emission category being forecasted. With this sliding window technique, the model can identify the temporal patterns in historical data.

From a user perspective, each window–target pair can be interpreted as a small forecasting task: given the last w months, predict the next h months. By repeating this across the historical record, the models see many examples of how emissions evolve under different economic and policy conditions.

The final step, temporal data splitting, preserves the original chronological division of the sequences into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets. It maintains temporal ordering, meaning that future data is not available during model training, making it closest to real forecasting scenarios. This splitting strategy prevents data leakage and allows model evaluation under stringent conditions.

A single 70%/15%/15% chronological split was adopted because the dataset spans more than five decades of monthly observations, which provides a sufficiently large test segment to characterize out-of-sample performance. Alternative resampling schemes such as rolling-origin evaluation were considered conceptually, but a fixed temporal split was preferred here to preserve the natural time order, simplify reproducibility, and maintain a clear separation between model selection (on the validation set) and final assessment (on the test set).

| Algorithm 1 Data preprocessing pipeline. |

| Require: Raw time series , window size w, horizon h |

| Ensure: Training, validation, and test sets |

- 1:

Step 1: Normalize each feature to [0,1] range - 2:

for to d do - 3:

- 4:

end for - 5:

Step 2: Create sliding windows - 6:

- 7:

for to N do - 8:

- 9:

- 10:

end for - 11:

Step 3: Split data temporally (70%-15%-15%) - 12:

- 13:

- 14:

- 15:

return

|

3.4. Model Architecture

To make the comparison accessible, this subsection first introduces each architecture in intuitive terms before detailing its layers. All four models receive the same preprocessed input sequences but process them in different ways. LSTM and GRU networks are designed to track how information evolves over time, CNN–LSTM combines local pattern detection with long-term memory, and DNN serves as a simpler, non-temporal baseline that is closer to traditional regression or feedforward neural networks.

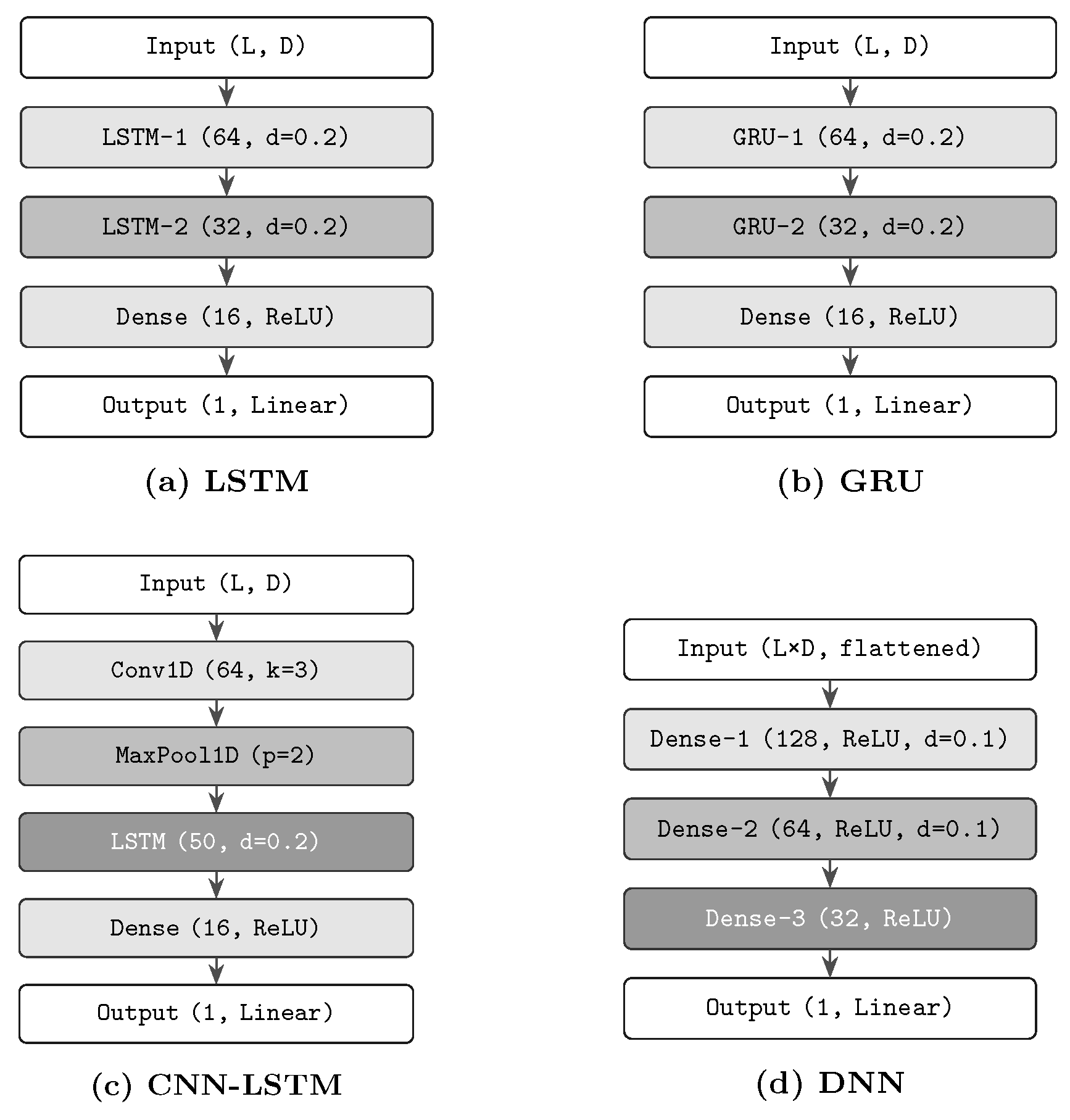

The LSTM network employs a two-layer recurrent setup (64 → 32 units) with total dropout regularization (0.2) for both the input and the recurrent connections, as illustrated in

Figure 1a. The input sequence first passes through an LSTM layer with 64 hidden units, whose outputs are then fed into a second LSTM layer with 32 hidden units, followed by a dense interpretation layer (16 units, ReLU) and a linear output layer. In practice, this means that the LSTM can remember prolonged trends in emissions (such as gradual decarbonization or sustained growth) while also reacting to sudden shocks, making it well suited for long historical records like the 52-year EIA series.

In practice, this means that the LSTM can remember prolonged trends in emissions (such as gradual decarbonization or sustained growth) while also reacting to sudden shocks, making it well suited for long historical records like the 52-year EIA series.

The GRU network is a simplified version with the same layer structure but simplified gating (reset and update gates only) that has about 25% fewer parameters without the loss of temporal modeling capacity as compared to the original design.

Because the GRU has fewer gates and parameters than the LSTM, it often learns slightly faster and uses fewer computational resources, which is attractive for institutions that must retrain models frequently on standard hardware.

The hybrid CNN–LSTM employs one-dimensional convolution (64 filters, kernel = 3) and max pooling (pool size = 2) for local pattern extraction, and then an LSTM layer (50 units) for temporal sequence modeling, as shown in

Figure 1c. The convolutional layer detects short-term patterns such as seasonal peaks or recurring monthly fluctuations, and the subsequent LSTM layer learns how these local patterns combine into longer-term trajectories. The Dense Network, a non-temporal baseline depicted in

Figure 1d, uses four fully connected layers (128 → 64 → 32 → 1 units) with flattened input sequences. The DNN provides a useful reference for readers familiar with standard feedforward networks, showing the limits of ignoring temporal order when modeling complex emission dynamics.

Table 2 represents the differential points of disclosed models by comparing their architectural specifications and depicting their structural and computational differences.

Both LSTM and GRU models include recurrent layers with a reduced number of hidden units (64 → 32) to capture temporal dependencies, while the CNN–LSTM hybrid model uses convolutional feature extraction combined with a sequential model.

The baseline is a DNN with a non-temporal approach and the largest parameter count (21,345), in contrast to the more parameter-efficient GRU (13,892). Moreover, all temporal models use a higher dropout rate (0.2) to prevent overfitting in sequential learning tasks, compared to the DNN (0.1).

The DNN provides a useful reference for readers familiar with standard feedforward networks, showing the limits of ignoring temporal order when modeling complex emission dynamics. The data flow patterns for the different architectures are represented in

Figure 1.

3.5. Training Configuration

To compare neural network architectures, we implement a standardized training procedure with specified hyperparameters. Hyperparameters were chosen in accordance with recognized best-practice guidelines. Identical hyperparameter configurations were employed for the training of each model, and the details are provided in

Table 3.

We chose the Adam optimizer due to its adaptive learning rate and because it is generally suitable for the training of deep neural networks. For all architectures, a learning rate of 0.001 is enough to ensure safe and stable convergence. Overfitting is prevented by means of early stopping with a patience of 15 epochs.

Before fixing the hyperparameters shown in

Table 4, a set of preliminary experiments was conducted using the LSTM model to explore reasonable ranges for learning rate, batch size, number of units, and regularization strength. The final configuration represents a compromise between stability, convergence speed, and computational cost that worked well across horizons. For fairness and to isolate the effect of the architectural design itself, the same hyperparameter configuration is then applied to all four models. This controlled choice simplifies the comparison but may not be individually optimal for every architecture; this is acknowledged as a limitation and a potential avenue for future work involving architecture-specific tuning.

Four different metrics have been used for model performance: Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and R-squared (). In addition to absolute error metrics, we explicitly report the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), which expresses the average prediction error as a percentage of the true emission values so that readers can directly assess how large the typical error is relative to observed emissions.

RMSE expresses error measures in the original data units (million metric tons CO2). RMSE’s vulnerability to outliers accentuates those larger prediction errors in policy applications. MAE, which is less sensitive to outliers, serves as a complementary error assessment. The linear penalty structure of MAE treats all errors in the same way regardless of their size, thus providing insight into typical prediction accuracy in the total test set. RMSE and MAE in combination reveal the distribution error and the model reliability. MAPE is a scale-independent metric allowing the comparison of the performances of different emission categories. MAPE needs careful consideration when the actual values are very close to zero because the division by small numbers may result in a very high error percentage. In cases where numbers are close to zero, we have implemented measures to ensure that the figures are interpretable. is the proportion of the variance explained by each model and shows the overall predictive power. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test is used to decide whether the differences in performances between models are not simply due to random variations. This nonparametric test, which makes very few assumptions about the distributions, tests the significance of paired performance comparisons. We set the levels of significance at for normal significance and for strong significance.

3.6. Adaptive Training Algorithm

Adaptive training for optimal parameter tuning with dynamic learning rate, combining early stopping to avoid overfitting, is described in Algorithm 2. The main parts of the algorithm are as follows:

Adaptive learning rate: For the Adam optimizer, a learning rate is produced that can be different depending on the first and second moments of the gradients. By this means the convergence can be accelerated in different training scenarios since the loss function landscape is effectively navigated.

Early stopping: The training is tracked through a validation dataset, and if the validation loss does not improve for a certain number of epochs, the training is stopped. The purpose of early stopping is to prevent overfitting by determining the point at which the model’s performance on unseen data would go down if the training were continued further.

Batch processing: The training data is processed in mini batches, which is a compromise between stochastic gradient descent and full batch efficiency. This makes it possible to work with larger datasets.

The strategy leads to better environmental behavior modeling and thus more effective training. This procedure ensures not only effective training but also maximizes its performance on new datasets.

| Algorithm 2 Adaptive learning rate training with early stopping. |

| Require: Training data , validation data |

| Ensure: Optimized model parameters |

- 1:

Initialize:, , , - 2:

patience , best_loss , counter , epoch - 3:

while epoch and counter < patience do - 4:

// Forward pass and loss computation - 5:

for batch in do - 6:

for all - 7:

- 8:

end for - 9:

Backward pass with Adam optimizer - 10:

- 11:

- 12:

- 13:

- 14:

- 15:

- 16:

Validation and early stopping - 17:

- 18:

if best_loss then - 19:

best_loss - 20:

- 21:

counter - 22:

else - 23:

counter = counter - 24:

end if - 25:

epoch = epoch - 26:

end while - 27:

return

|

4. Results

While the models are trained on all eight emission categories described in

Section 3, the detailed results report separate performance curves for six key categories (Coal, Natural Gas, Distillate Fuel Oil, Motor Gasoline, Petroleum, and Total Energy). The remaining two categories are included in the multivariate inputs and in the aggregate performance summaries but are omitted from individual plots for brevity.

4.1. Model Performance

Comprehensive assessment of four neural network architectures reveals considerable performance variations in CO2 emission prediction using the EIA dataset.

Table 4 presents performance metrics for the evaluated architectures, demonstrating that the sequential models have a substantially higher performance than that of the feed-forward ones.

According to

Table 4, RMSE and MAE indicate the typical size of forecasting errors in the original units (million metric tons of CO

2), while

shows how much of the variability in emissions is explained by each model. A reduction in several million metric tons in RMSE, as achieved by LSTM compared to DNN, corresponds to noticeably tighter forecast bands around historical trajectories, which is crucial when planning capacity expansions or evaluating policy scenarios.

Across all evaluation metrics, the LSTM model achieves the smallest RMSE, equal to 15.23 million metric tons, and the lowest MAE of 11.45 million metric tons, as well as a MAPE of 2.89%. Given this superior performance, LSTM is considered the primary model when making predictions of emissions, in particular, when needing a very accurate one.

The GRU design’s notable characteristic is its ability to achieve performance levels comparable to LSTM but with significantly greater computational efficiency. Specifically, it achieves an RMSE of 16.78 million metric tons and at the same time uses 15.3% less training time. The 10.2% RMSE performance difference represents an acceptable trade-off for applications in which the available resources are limited, particularly if one also considers the 24% decrease in parameters that not only contributes to the reduction in the overfitting risk but also makes the model more lightweight.

4.2. Forecasting Horizon Analysis

Forecast quality can be assessed by examining how it performs for different prediction horizons. This reveals forecasting accuracy over time and where we may be faced with practical deployment limitations.

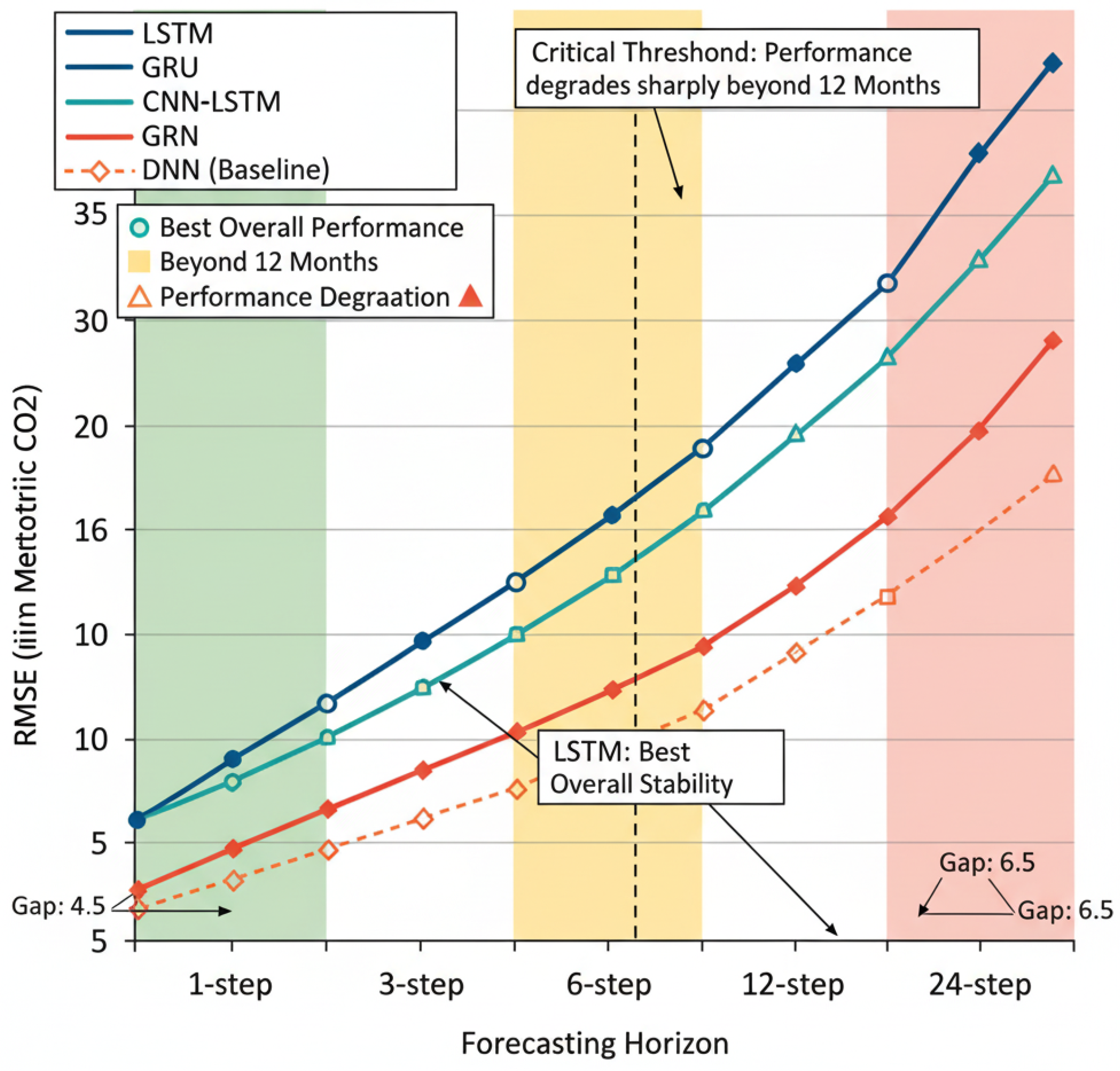

Table 5 provides the RMSE values for five different forecast horizons.

To put these values into perspective, the MAPE values indicate that, for short-term horizons, LSTM and GRU typically produce percentage errors in the low single digits, while CNN–LSTM and especially DNN exhibit larger percentage deviations. For longer horizons, MAPE remains moderate for the sequential models and increases more markedly for the DNN baseline. Referring to MAPE alongside RMSE helps readers quickly gauge the relative size of the forecasting errors without needing to compare RMSE to the underlying emission magnitudes.

These horizon-specific errors can be directly linked to policy questions. One- to three-month forecasts support near-term monitoring (e.g., detecting unusual spikes), six- to twelve-month forecasts support budgeting and regulatory compliance planning, and 24-step forecasts approximate long-term strategic scenarios. The progressive increase in RMSE with the horizon highlights that long-range forecasts should be interpreted as indicative scenarios rather than precise point predictions.

Short-term forecasts (1–3 steps ahead) demonstrate high precision for all the models, with LSTM being able to achieve the RMSE less than 12.67 million metric tons for 3-step predictions. This accuracy enables the usage of the system for real-time monitoring and immediate policy-response scenarios.

Medium-term forecast results (6–12 steps ahead) reveal the differences between the models, where LSTM is still leading, although the error rates are going up by 60 to 137% compared to 1-step.

Figure 2 shows that for medium-term predictions (6–12 steps ahead), the difference between the performance of LSTM and GRU on one side, and the baseline DNN on the other side becomes increasingly significant. The CNN-LSTM combined model is able to deliver results that are on par with the best ones, in particular at the 12-step horizon, where the convolutional layers for feature extraction contribute to the stabilization of the forecasts of the medium term.

Figure 2 mainly focuses on long-term prediction (24 steps ahead), where the increase in the error becomes significant for all the models, going up from 268% to 367% in terms of RMSE relative to one-step forecasts. LSTM is the model that most successfully limits error expansion, followed by GRU and CNN–LSTM, while DNN is the most vulnerable to errors. In general,

Figure 2 reveals that all models are capable of short-term forecasting at an acceptable level, and it also emphasizes the necessity of recurrent neural networks, especially LSTM, for predictions in the medium and long term. This is evidence that the main factor in significantly lowering the error propagation over long forecasting horizons is the correct modeling of the temporal dependencies.

4.3. Emission Category Performance Analysis

Analysis of individual emission categories reveals varying model performance for various sources of CO

2 emissions, indicating architecture suitability (see

Table 6).

Total energy CO2 emissions show the greatest performance differences across architectures, with LSTM outperforming DNN by 22.5%. LSTM has outperformed DNN by 22.5%. Moreover, LSTM has significantly improved coal emission predictions, thereby illustrating the temporal modeling capability of LSTM in figuring out how policy and economic factors affect the consumption of coal over 52 years.

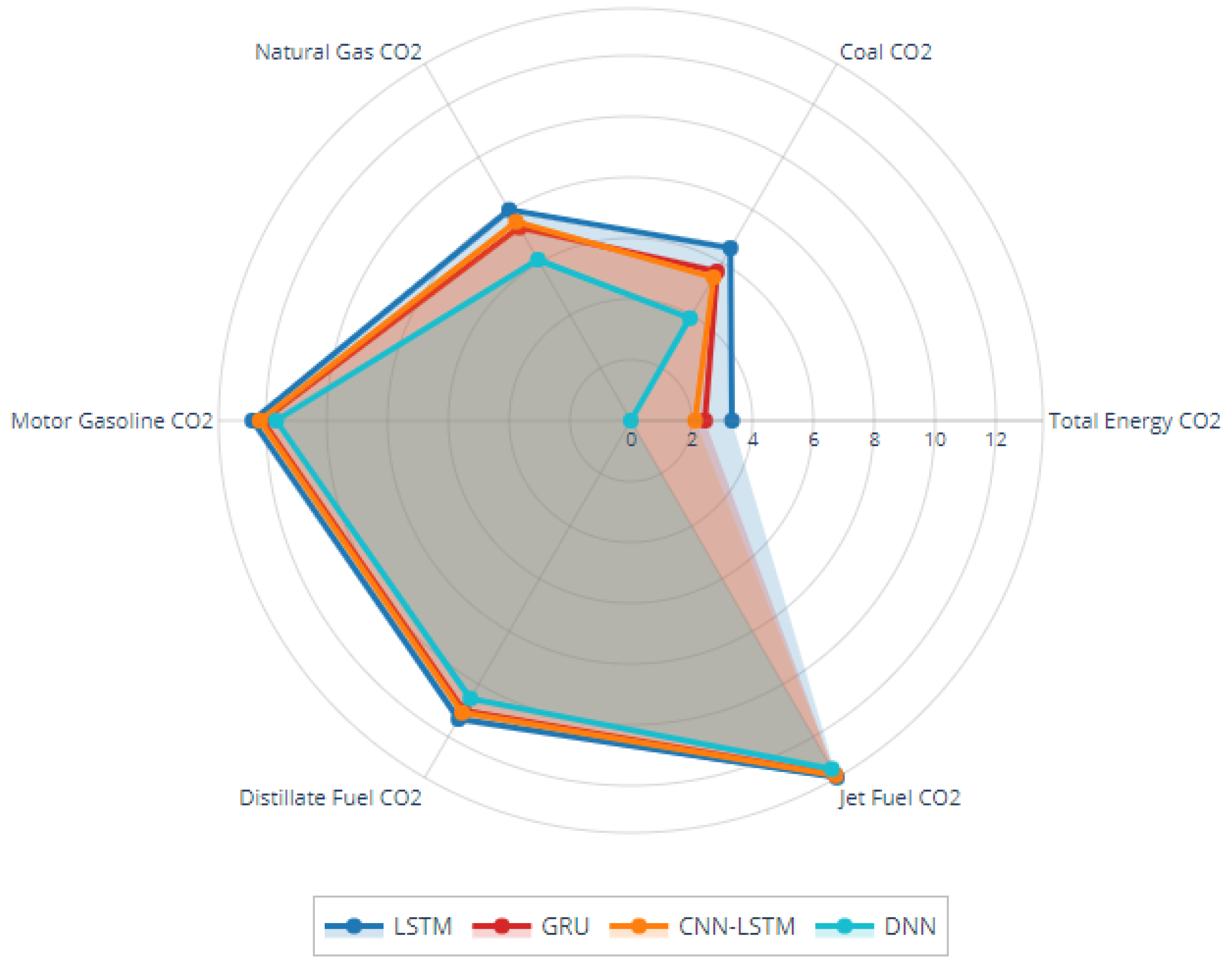

Figure 3 shows a radar chart comparing the performance of the models across different categories of CO

2 emissions. The radar diagram features six emission categories: Natural Gas CO

2, Coal CO

2, Total Energy CO

2, Jet Fuel CO

2, Distillate Fuel CO

2, and Motor Gasoline CO

2. The performance of each model is depicted as a differently colored polygon, where the distance of each vertex from the center shows the relative performance level. This display of information brings out the main features of model behavior across the following emission categories:

LSTM models’ major characteristic is their superior performance. The blue polygon (LSTM) in

Figure 3 is almost always the one that extends to the greatest distance from the center for most emission categories.

Comparable architectures cluster together: The GRU (red) and CNN-LSTM (orange) vertex distribution in

Figure 3 shows a strong visual similarity, which is also supported by the statistical evidence of performance differences being not significant between these architectures (

p-values

in

Table 7).

Performance limitations of feedforward networks: The color of the DNN polygon is teal, and it is almost always the closest to the center, which visually confirms its function as a baseline non-temporal method. The performance drop can be seen in all categories, thus revealing that feedforward architectures are at a systematic disadvantage when it comes to temporal emissions forecasting.

The radar chart is an efficient way to illustrate performance patterns of different emission sources as follows:

Variance-rich categories (Total Energy CO2, Coal CO2) reveal the greatest polygon separation, suggesting that these complex emission sources benefit most from sophisticated temporal modeling.

Low-variance categories (Jet Fuel CO2, Motor Gasoline CO2) show smaller polygonal differences, suggesting that the matter of architectural choice is less important for these more predictable emission patterns.

Natural Gas CO2 represents a middle ground where temporal models keep advantages but with lessened magnitude when compared to coal and total energy emissions.

LSTM’s distinctly different positioning across multiple dimensions supports our work’s recommendation of LSTM use in high-stakes policy applications. Conversely, visual similarity between GRU and CNN-LSTM polygons validates either architecture for efficiency-focused implementations where the performance trade-off is acceptable.

4.4. Statistical Significance Assessment

We employ the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for nonparametric comparison (Equation (

4)).

where

represents the difference in absolute errors between models A and B, and

is the rank of

.

Table 7 presents

p-values for pairwise architecture comparisons.

LSTM statistically outperforms all other architectures across all evaluation metrics. Moreover, the differences between LSTM and DNN are highly significant (). There is no statistically significant difference found between GRU and CNN–LSTM, which implies that both models perform similarly even though their structures are different.

For the Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, each pairwise comparison between architectures is based on the same set of paired error observations, obtained by aggregating the forecasting errors across emission categories and prediction horizons (resulting in

N paired samples per comparison). In total, we perform six pairwise comparisons (LSTM vs. GRU, LSTM vs. CNN–LSTM, LSTM vs. DNN, GRU vs. CNN–LSTM, GRU vs. DNN, and CNN–LSTM vs. DNN) for each evaluation metric. When interpreting the

p-values, we adopt a conservative perspective and note that the main findings (in particular, the superiority of LSTM over the other architectures and the large gap between sequential models and DNN) remain unchanged under simple Bonferroni-style adjustment across these comparisons. For the Shapiro–Wilk normality tests in

Table 8, the sample size corresponds to the number of residuals in the test set for each model, which is sufficiently large for the normality assessment to be reliable.

Table 8 shows the results of the statistical tests for the residual analysis of different models.

The Shapiro-Wilk test evaluates the normality of residual distribution, which is a condition that leads to statistically valid inferences and the proper functioning of the model assumptions. The test is based on the assumption that the residuals are normally distributed under the null hypothesis, and the hypothesis is rejected if p < 0.05. The models had the following different levels of effectiveness:

LSTM, GRU, and CNN–LSTM models all pass the normality test with p-values ranging from 0.058 to 0.134; thus, all of them are above the 0.05 significance level. This confirms that the residuals are normally distributed, so confidence intervals and hypothesis tests can be performed in a reliable manner.

The residuals of DNN show a deviation from normality (p = 0.034); thus, a slight residual non-normality is suggested. The violation being very slight only, it may result in statistical inferences made being inaccurate, and therefore, it is better to use robust statistical methods in DNN-based analyses.

W-statistics from 0.941 to 0.967 indicate even more normality of the data. Residuals of normal distributions are best kept in sequential models (LSTM, GRU, CNN–LSTM).

The Breusch–Pagan test is one among several whose purpose is to identify if the different observations have the same error variance. This is, in fact, one of the most essential assumptions of ordinary least squares estimation and various statistical procedures. The null hypothesis states that the errors are homoscedastic and therefore, a rejection at indicates heteroscedasticity. The findings of the test are as follows:

LSTM, GRU, and CNN–LSTM models do not appear to violate the assumption of homoscedasticity, as their p-values range from 0.089 to 0.140, indicating that the error variance is approximately constant. This not only allows for the application of standard statistical methods but also demonstrates the stability of these models across different prediction horizons.

The DNN model breaches the homoscedasticity assumption (), which implies that there is a certain systematic pattern in the error variance. This heteroscedasticity issue stems from the insufficient modeling of temporal dependencies; thus, different parts of the data have different prediction accuracies.

LM statistics indicate that the variance of the DNN model is almost twice as heterogeneous as that of the sequential models (LM = 4.23 for DNN vs. LM = 2.18–2.89 for sequence models); thus, temporal modeling approaches have better residual behavior.

4.5. Computational Efficiency

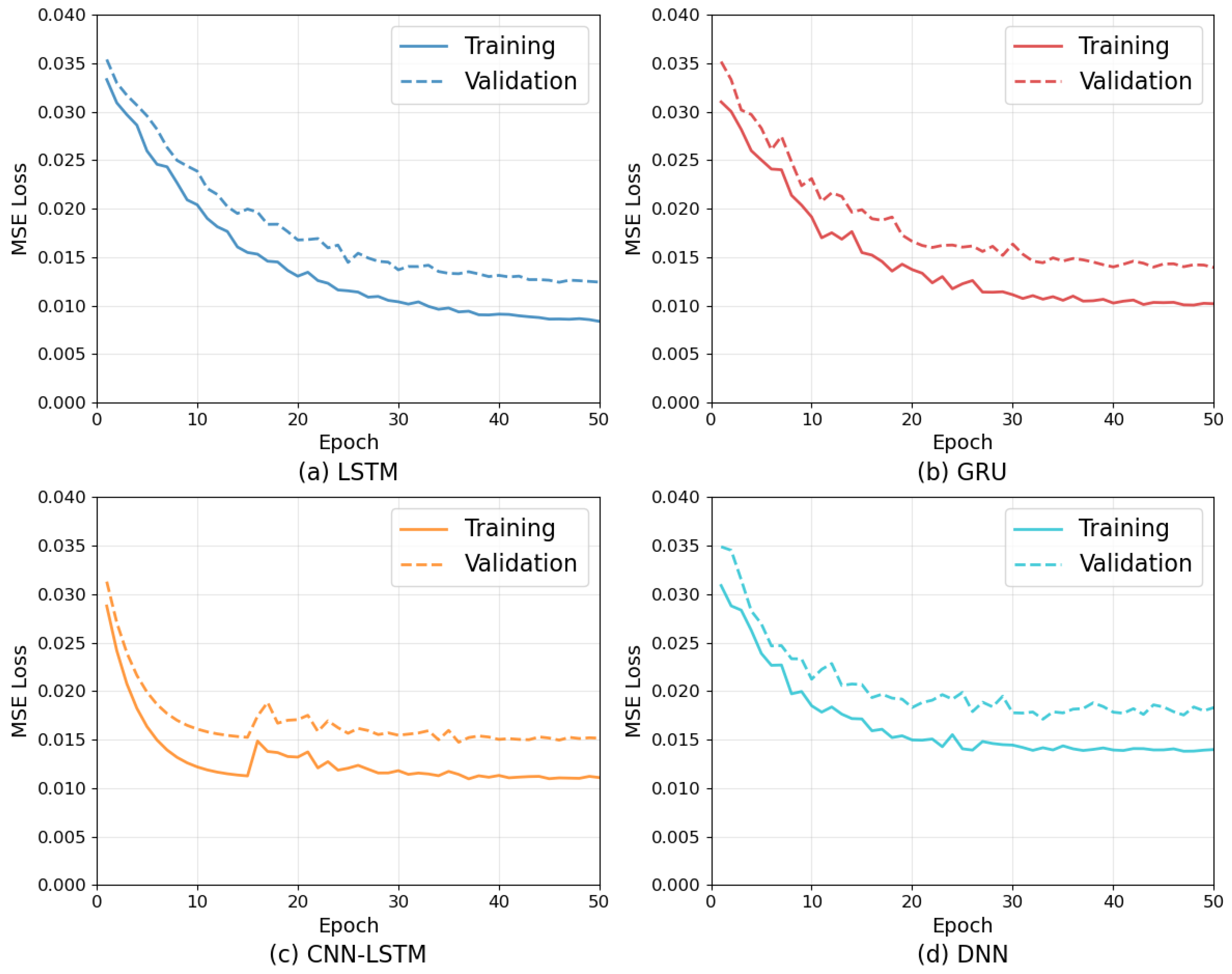

Differences in the convergence patterns of the neural networks were identified as the key factors that distinguished them through the analysis of the training behavior. The comparison of the training and validation losses of the four architectures for 50 epochs (see

Figure 4) visually represents the models’ typical learning behaviors and gives insight into their selection and usage. The data presented for LSTM (

Figure 4a), GRU (

Figure 4b), CNN–LSTM (

Figure 4c), and DNN (

Figure 4d) illustrate the change in loss, measured by MSE, over 50 epochs of training.

The LSTM networks (

Figure 4a) feature a smooth, monotonically converging loss function with only a minor oscillation that leads to the best performance at about epoch 45–50. The stability of the model is well reflected in the final training loss of 0.0085 and the validation loss of 0.0124, with a small generalization gap of 0.0039.

GRU architectures (

Figure 4b) exhibits faster initial learning. They achieve optimal results by epoch 35–40, with slightly more oscillation in subsequent epochs. Superior computational efficiency is particularly visible in rapid early learning, where most of the final performance (training: 0.0102, validation: 0.0143) is achieved with a very small generalization gap of 0.0041, which indicates a high model quality. CNN-LSTM displays a typical two-stage learning process pattern: first, rapid convolutional feature extraction improvement (epochs 1–15) and then LSTM stabilization and refinement (epochs 15–50). The losses for this network are 0.0112 (training) and 0.0151 (validation) with the generalization gap corresponding to 0.0039 (see

Figure 4c).

DNNs make gradual improvements and show the fastest convergence around epoch 25–30 but have significantly higher final loss values (training: 0.0139, validation: 0.0183) that are about twice as high, thus revealing the limitations of a non-temporal approach albeit computational advantages (see

Figure 4d).

4.6. Computational Complexity Analysis

Table 9 illustrated the computational complexity of various neural network architectures that are determined by sequence length

T, hidden dimension

H, and batch size

B. The complexity indicates that although LSTMs are powerful in sequence modeling, they still pay a large computational cost, especially for long sequences and large hidden dimensions. On the other hand, GRUs offer a more convenient alternative with lower costs, and the CNN-LSTM model has more operations, which are a combination of those of the two models, while the complexity of DNNs varies with the number of layers.

5. Analysis and Discussion

This section synthesizes the quantitative results into practical guidance for readers who may not specialize in deep learning. Instead of focusing solely on numerical differences, the discussion highlights when each architecture is preferable, what kinds of forecasting tasks it supports best, and how its computational profile affects deployment in policy and operational settings.

The LSTM architecture achieves superior CO2 emission predictions through advanced gating mechanisms enabling selective retention of information over extended periods exceeding 52 years of EIA dataset. The three-gate system (forget, input, and output) both captures and models the intricate environmental patterns resulting from policy changes, economic cycles, and seasonal variations, creating interdependencies between multiple time periods.

The 23.2% RMSE improvement over DNN (15.23 vs. 19.84) illustrates the considerable practical significance of the research area of national-level policy planning. Errors in forecasting that lead to wrong decisions concerning resource allocation and regulations are, therefore, avoided. By using this constant error cell principle, the gradients are kept active, and the model is still able to learn efficiently from both local policy reactions and slow technological evolutions recorded in the EIA dataset. The results show that LSTM outperforms GRU accuracy by 8.9%; however, GRU accounts for 91.1% of LSTM accuracy (16.78 vs. 15.23 RMSE). Moreover, GRU has 24% fewer parameters, and the training time is 15.3% shorter due to the simplified two-gate architecture. This efficiency advantage is critical for operational forecasting systems, which require frequent model updates as new EIA data arrives every month.

Analysis shows that the short-term predictions of GRU are nearly as accurate as those of LSTM (14.1% RMSE difference for 1-step ahead); however, it suffers more in the accuracy for longer horizons, thus, suggesting that GRU simplifications affect the long-term dependency aspect of the model which is extremely important for multi-year policy planning applications. The hybrid architecture (CNN-LSTM) nearly matches the performance (17.12 RMSE) with some notable merits for the medium-term forecasting use cases. Convolutional parts detect the recycled patterns, for example, the seasonal heating/cooling cycles and the consumption of transportation fuel, without the need for manual feature engineering, whereas the LSTM layers capture the long-term effect of structural change in the pattern.

The two-phase observed learning pattern (rapid convolutional optimization in epochs 1–20, followed by LSTM refinement in epochs 20–45) is a strong indication that learning rate optimization for each component separately could yield better results. DNN results demonstrate the performance gap compared to sequential architectures. For structured features and non-temporal pattern recognition, DNN achieves a high of 0.893. Computationally, DNN is twice as fast (94.7 vs. 158.4 seconds of training for LSTM).

LSTM significantly outperforms DNN by a margin of 30.3% in terms of performance, demonstrating that advanced temporal modeling is essential for emissions forecasting. Therefore, the increased computational cost is justified by the accuracy improvements in policy-critical applications.

Short-term predictions achieve high accuracy for all models, and LSTM makes RMSE go below 12.67 million metric tons for three-step predictions. This performance level allows for the monitoring of emissions in real-time and the immediate policy interventions that require a quick reaction to the unforeseen changes. The minor performance differences (14.1% RMSE between LSTM and GRU for 1-step forecasting) indicate that computational efficiency should be put first over very slight accuracy improvements when it comes to instant planning that needs monthly updates.

The differences in errors become very large in the case of medium-term forecasting, where the rates of error are 61–107% higher compared to those of short-term predictions, which shows that the uncertainty becomes bigger due to the cumulative effect. LSTM is still the best alternative (22.34 vs. 27.89 RMSE compared to DNN for 12-step forecasting) thereby giving a reason for the use of more computational resources for the planning of the next quarter. CNN–LSTM shows close-to-LSTM accuracy (24.23 RMSE for 12-step forecasting) and, at the same time, it is computationally efficient. The described level of performance is in line with the requirements of strategic planning with the use of a forecasting horizon of 6–12 months for tasks such as budget allocation and regulatory compliance. Notwithstanding, long-term forecasting unveils sizable errors in the case of all architectures (268–367%), which is attributable to the theoretical limits of sequential prediction and complexity of the environmental system. Despite superior performance, LSTM still shows significant absolute errors (34.78 vs. 41.23 RMSE for DNN), limiting its applicability for high-precision long-term planning. The consistently lower MAPE values for LSTM and GRU further confirm that their typical percentage forecasting errors are smaller, which means that the improvements observed in RMSE translate into practically meaningful gains for emissions planning.

Beyond reporting that LSTM-based models achieve the best overall accuracy, the study contributes a standardized experimental framework and a set of architecture-specific recommendations for multivariate CO2 emissions forecasting. The joint analysis of horizon-dependent performance, residual behavior, and computational cost is, to our knowledge, rarely addressed in a single work on emissions forecasting. These elements are intended to make the results actionable for both method developers and practitioners in environmental policy.

The analysis of the forecasting horizon offers the following deployment advice to policymakers:

Short-term monitoring (1–3 months): All models perform adequately under this time span, as even simpler models achieve satisfactory accuracy, enabling focus on rapid implementation and resource efficiency.

Medium-term planning (6–12 months): LSTM or CNN-LSTM forecasts justify their additional complexity, supporting budget and compliance planning.

Long-term strategy (>12 months): Predictions should inform scenario analysis rather than serve as definitive forecasts.

Despite these encouraging results, several limitations of the present study should be noted when interpreting the findings and their potential implications. First, all experiments are conducted on a single long-span dataset from the U.S. EIA. Although this dataset is rich and policy-relevant, it may not capture structural characteristics, regulatory regimes, or data quality issues present in other countries or sectors. Structural breaks in emissions drivers, such as abrupt policy changes or large economic shocks, could affect model behavior differently in other contexts.

Second, the models are trained under a specific preprocessing and hyperparameter configuration that was deliberately standardized across architectures to enable fair comparison. While this controlled design helps isolate architectural effects, it also means that some models might achieve better performance under architecture-specific tuning. The reported rankings should therefore be viewed as indicative within this setup, not as definitive across all possible configurations.

Third, the evaluation relies on a single chronological 70/15/15 split of the time series, which reflects a realistic forecasting scenario but does not exhaust alternative validation schemes (such as rolling-origin evaluation). Future work could explore more extensive resampling strategies to assess the robustness of the conclusions under varying training periods and breakpoints.

Finally, the policy-related interpretations drawn from the results should be read as qualitative guidance on model selection rather than as categorical prescriptions. For example, while LSTM appears well suited for medium- and long-horizon forecasting in the U.S. EIA setting, practitioners should consider local data characteristics, computational constraints, and domain expertise when choosing and configuring models for operational policy support.

6. Conclusions

This paper provides an in-depth comparison of four deep learning architectures (LSTM, GRU, CNN–LSTM, and DNN) for predicting multivariate CO2 emissions using more than 50 years of data from the U.S. EIA. The results show that temporal models—especially LSTM networks—are most accurate in tracking long-term dependencies and minimizing forecast error. GRUs are almost as good as LSTMs while having fewer parameters and less training time. CNN–LSTMs are very effective for very short-term forecasting because the convolutional layers can extract features very efficiently while the recurrent layers can capture the temporal structure. On the other hand, computationally efficient DNN baselines that cannot sufficiently model sequential dependencies have been found to be less useful in policy-critical applications.

Furthermore, the analysis reveals that the effectiveness of the model is contingent upon the forecasting horizon as well as the emission category. LSTMs keep up their strong precision over intermediate and long-term horizons and hence can be used for strategic planning, while GRUs and CNN–LSTMs are better for short- to medium-term operational monitoring. Statistical tests indicate that the differences between recurrent and non-recurrent models are significantly pronounced. Non-recurrent models are thus heavily limited due to the considerable error accumulation in long-term predictions, which makes them not eligible as primary tools but just as a supporting stock in climate policy planning.

For practitioners and policymakers, the results can be summarized as follows. LSTM models are recommended when accuracy over medium and long horizons is the main priority; GRU and CNN–LSTM are suitable when a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency is required, and DNNs can be used as fast baselines or for exploratory analyses but not as primary tools in high-stakes decisions. By framing the architectures in terms of their strengths, limitations, and typical use cases, the study aims to make advanced neural forecasting methods more accessible to a broad environmental and policy audience.

Future research should explore hybrid and ensemble methods that combine statistical and deep learning techniques to better address the trade-offs between accuracy, interpretability, and robustness.