Effect of Notch Depth on Mode II Interlaminar Fracture Toughness of Rubber-Modified Bamboo–Coir Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

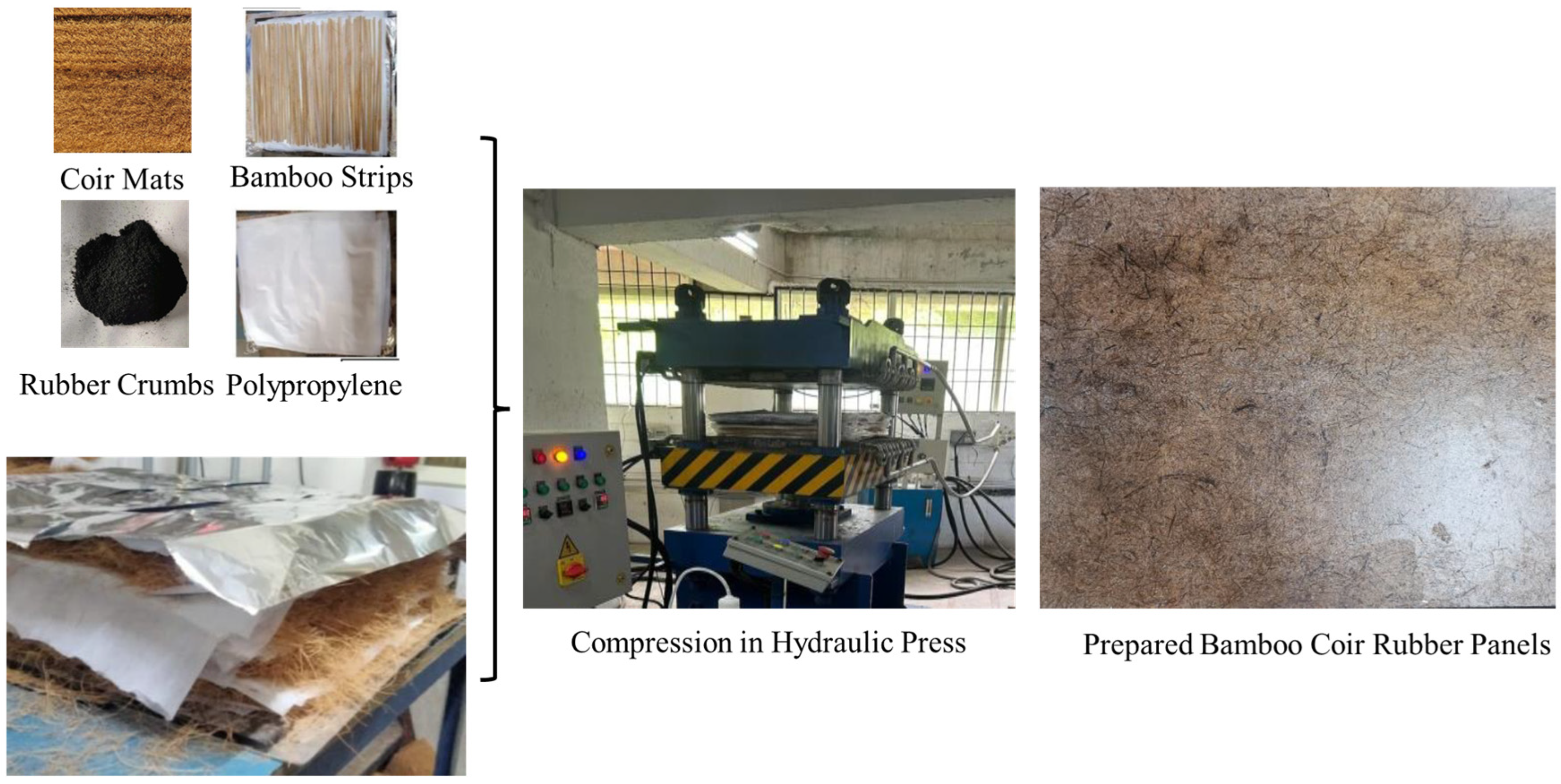

2.1. Materials

2.2. Panel Fabrication

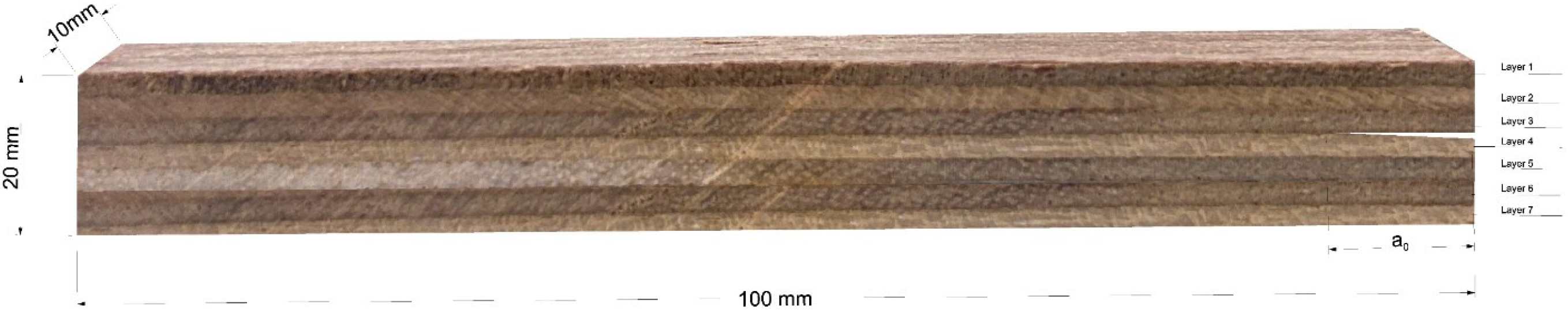

2.3. Specimen Preparation and Notch Geometry

2.4. End-Notched Flexure (ENF) Test Configuration

2.5. Optical Image-Based Crack Tracking and Monitoring

2.6. Microstructural Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

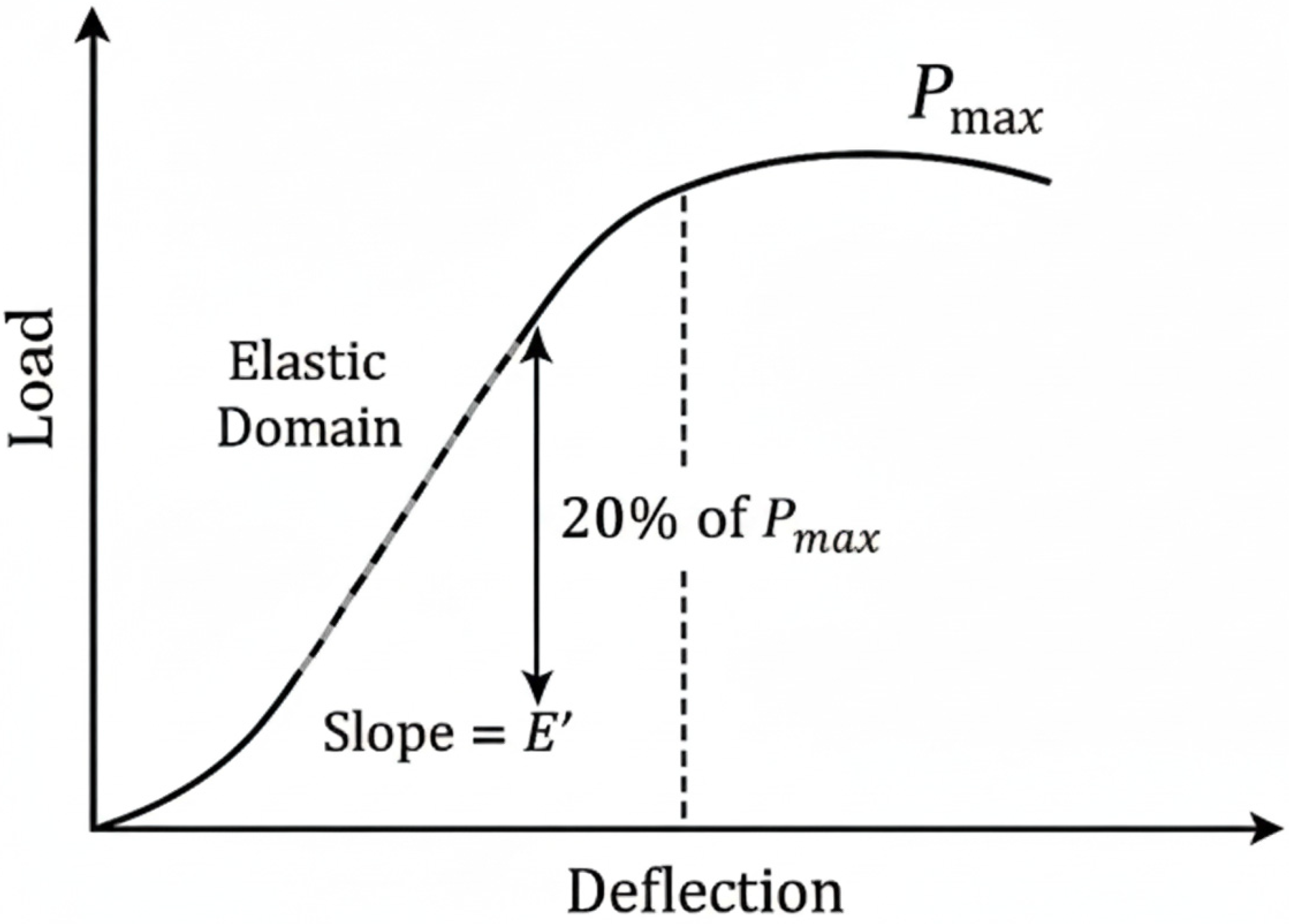

3.1. Load–Displacement Behavior

3.2. Crack Propagation and ImageJ-Based Analysis

3.2.1. Crack Initiation and Propagation

3.2.2. Effect of SBR Modification

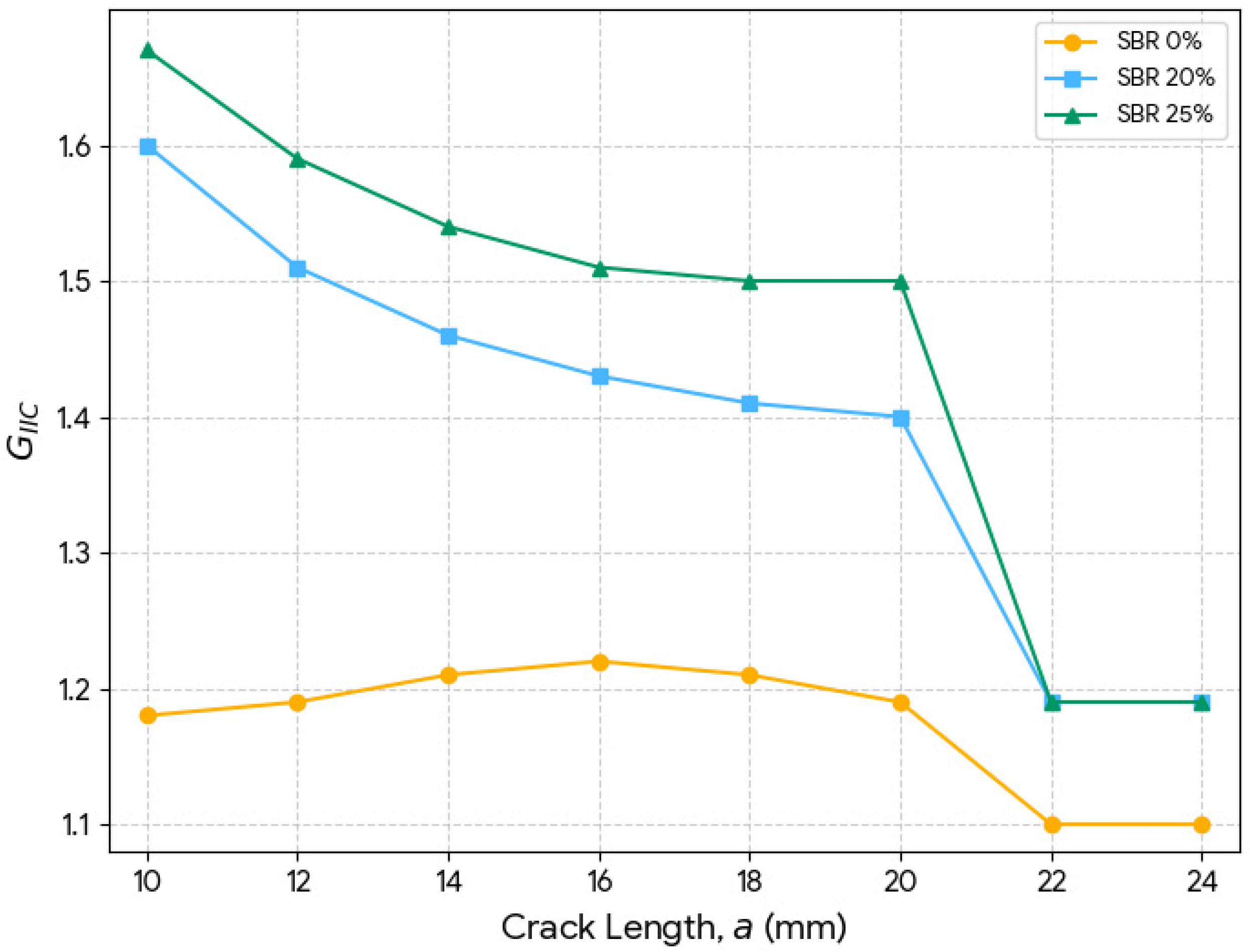

3.2.3. Influence of Initial Notch Ratio (a0/L)

3.2.4. Correlation Between C-A and GIIc

3.3. Microstructural Analysis of the Fracture Surface

4. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

- The Mode II strain energy release rate of BCR panels increased considerably with the incorporation of SBR, achieving up to 1.98 kJ/m2 at 30% SBR content as compared to 1.26 kJ/m2 for the unmodified laminate (SBR 0%). This improvement was attributed to rubber-particle cavitation, matrix shear yielding, and coir–fiber bridging mechanisms that together promote progressive crack growth and delayed delamination. Optimal enhancement occurred at 20–25% SBR, balancing the ductility and stiffness while maintaining nearly 90% of the unmodified load-bearing capacity.

- Increasing the crack ratio from 0.2 to 0.4 doubled the specimen compliance and reduced the GII values by approximately 20%. This confirmed the geometrical sensitivity of the interlaminar shear response. However, it must be noted that higher a0/L ratios yielded smoother post-peak transitions and more stable crack propagation, indicating the dominance of sliding-type delamination.

- The commercial plywood exhibited brittle, unstable fracture with GII in the range of 0.7 to 0.9 kJ/m2. The inclusion of SBR resulted in 60–80% higher Mode II fracture energy, emphasizing superior energy absorption and damage tolerance of the hybrid laminates over traditional resin-bonded veneers.

- SEM analysis confirmed the presence of cavitated SBR domains, plastic shear bands, and coir-pullout zones, validating the observed macroscopic increase in the fracture energy. The ductile failure morphology contrasted with the clean brittle adhesive separation seen in plywood. This underscored the constructive interaction between rubber-induced plasticity and natural fiber bridging.

- The combination of bamboo and coir fibers with a PP matrix and SBR modification yields a fully thermoplastic laminate exhibiting toughness levels comparable to structural plywood.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mohammadabadi, M.; Yadama, V.; Dolan, J.D. Evaluation of Wood Composite Sandwich Panels as a Promising Renewable Building Material. Materials 2021, 14, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; He, S.; Leng, W.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Z. Replacing Plastic with Bamboo: A Review of the Properties and Green Applications of Bamboo-Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites. Polymers 2023, 15, 4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Neves, V.; Banea, M.D. Mechanical and Thermal Characterization of Bamboo and Interlaminar Hybrid Bamboo/Synthetic Fibre-Reinforced Epoxy Composites. Materials 2024, 17, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madueke, C.I.; Ekechukwu, O.M.; Kolawole, F.O. A Review on Coir Fibre, Coir Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites and Their Current Applications. J. Renew. Mater. 2024, 12, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriseubsai, W.; Praemettha, A. Hybrid Natural Fiber Composites of Polylactic Acid Reinforced with Sisal and Coir Fibers. Polymers 2024, 17, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puttaswamygowda, P.H.; Sharma, S.; Ullal, A.K.; Shettar, M. Synergistic Enhancement of the Mechanical Properties of Epoxy-Based Coir Fiber Composites through Alkaline Treatment and Nanoclay Reinforcement. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasti, S.; Hubbard, A.M.; Clarkson, C.M.; Johnston, E.; Tekinalp, H.; Ozcan, S.; Vaidya, U. Long coir and glass fiber reinforced polypropylene hybrid composites prepared via wet-laid technique. Compos. Part C Open Access 2024, 14, 100445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adediran, A.A.; Akinwande, A.A.; Balogun, O.A.; Olasoju, O.S.; Adesina, O.S. Experimental evaluation of bamboo fiber/particulate coconut shell hybrid PVC composite. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuswan, T.; Manik, P.; Samuel, S.; Suprihanto, A.; Sulardjaka, S.; Nugroho, S.; Pakpahan, B.F. Correlation between lamina directions and the mechanical characteristics of laminated bamboo composite for ship structure. Curved Layer. Struct. 2023, 10, 20220186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhudass, J.M.; Palanikumar, K.; Natarajan, E.; Markandan, K. Enhanced thermal stability, mechanical properties and structural integrity of MWCNT filled Bamboo/Kenaf hybrid polymer nanocomposites. Materials 2022, 15, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martijanti, M.; Sutarno, S.; Juwono, A.L. Polymer Composite Fabrication Reinforced with Bamboo Fiber for Particle Board Product Raw Material Application. Polymers 2021, 13, 4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, A.; Al Rashid, A.; Polat, R.; Koç, M. Potential and challenges of recycled polymer plastics and natural waste materials for additive manufacturing. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2024, 41, e01103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.M.N.; M.N., P.; Lee, D.W.; Song, J.I. Enhanced mechanical and thermal properties of green PP composites reinforced with bio-hybrid fibers and agro-waste fillers. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2025, 8, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Cheng, X.; Wong, C.; Zeng, X.; Li, L.; Teng, C.; Du, G.; Zhang, C.; Ren, L.; Zeng, X.; et al. Insight into the fracture energy dissipation mechanism in elastomer composites via sacrificial bonds and fillers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 4429–4436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, B.; Talebi, H.; Momeni, M.M.; Ayatollahi, M.R. Experimental and theoretical investigation of the influence of post-curing on mixed mode fracture properties of 3d-printed polymer samples. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, N.L.; Hiranobe, C.T.; Cardim, H.P.; Dognani, G.; Sanchez, J.C.; Carvalho, J.A.J.; Torres, G.B.; Paim, L.L.; Pinto, L.F.; Cardim, G.P.; et al. A Review of EPDM (Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer) Rubber-Based Nanocomposites: Properties and Progress. Polymers 2024, 16, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhargavi, C.; Sreekeshava, K.S.; Prasad, B.K.R. Evolution of Studies on Fracture Behavior of Composite Laminates: A Scoping Review. Appl. Mech. 2025, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D7905/D7905M-14; Standard Test Method for Determination of the Mode II Interlaminar Fracture Toughness of Unidirectional Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Matrix Composites. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

- Yu, B.; Li, Y.; Tu, H.; Zhang, Z. Experimental and numerical investigation into interlaminar toughening effect of chopped fiber-interleaved flax fiber reinforced composites. Acta Mech. Sin. 2024, 40, 423287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Königsberger, M.; Senk, V.; Lukacevic, M.; Wimmer, M.; Füssl, J. Micromechanics stiffness upscaling of plant fiber-reinforced composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 281, 111571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; Niu, B.; Lv, C.; Liu, J. A Review of Sisal Fiber-Reinforced Geopolymers: Preparation, Microstructure, and Mechanical Properties. Molecules 2024, 29, 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Hamerton, I.; Allegri, G. Environmental Effects of Moisture and Elevated Temperatures on the Mode I and Mode II Interlaminar Fracture Toughness of a Toughened Epoxy Carbon Fibre Reinforced Polymer. Polymers 2025, 17, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharek, M.S.; Vengala, J.; Sunagar, P.; Sreekeshava, K.S.; Kilabanur, P.; Thejaswi, P. Biocomposites and Their Applications in Civil Engineering—An Overview. In Smart Technologies for Energy, Environment and Sustainable Development; Kolhe, M.L., Jaju, S.B., Diagavane, P.M., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Energy; Springer: Singapore, 2022; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shen, J.; Wang, W.; Li, L.; Zheng, D.; Qi, F.; Wang, X.; Li, Q. Comparison of the properties of phenolic resin synthesized from different aldehydes and evaluation of the release and health risks of VOCs. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 344, 123419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumins, J.A.; Vamza, I.; Dzalbs, A.; Blumberga, D. Particle Boards from Forest Residues and Bio-Based Adhesive. Buildings 2024, 14, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadiji, H.; Serra, J.; Curti, R.; Gebrehiwot, D.; Castanié, B. Characterization of mode II delamination behaviour of poplar plywood and LVL. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2024, 131, 104354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Debertolis, M.; Crocetti, R.; Wålinder, M.; Blomqvist, L. Spreading angle analysis on the tensile capacities of birch plywood plates in adhesively bonded timber connections. Eng. Struct. 2024, 315, 118428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vengala, J.; Kilaru, D.; Varshini, V.H. Analysis of bamboo tensegrity structures. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 65, 2060–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harries, K.A. Adoption of full-culm bamboo as a mainstream structural material. npj Mater. Sustain. 2025, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidi, M.; Park, C.B.; Il Kim, C. Synergism effect between nanofibrillation and interface tuning on the stiffness-toughness balance of rubber-toughened polymer nanocomposites: A multiscale analysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 24948–24967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lubineau, G. Towards stable End Notched Flexure (ENF) tests. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2024, 192, 05795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Kassapoglou, C. Experimental tests and numerical simulation of delamination and fiber breakage in AP-PLY composite laminates. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2024, 44, 1702–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyagari, S.; Al-Haik, M. Mitigating Crack Propagation in Hybrid Composites: An Experimental and Computational Study. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanowicz, M.; Grygorczuk, M. The effect of crack orientation on the mode I fracture resistance of pinewood. Int. J. Fract. 2024, 248, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpitha, G.R.; Raghu, M.J.; Bharath, K.N.; Jain, N.; Verma, A. Mechanical and micro-structural characterization of biodegradable coir fiber–glass sheet–charcoal reinforced polymer composite: An experimental approach. Discov. Polym. 2024, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpinteri, A.; Accornero, F.; Rubino, A. Scale effects in the post-cracking behaviour of fibre-reinforced concrete beams. Int. J. Fract. 2022, 240, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vašina, M.; Pöschl, M.; Zádrapa, P. Influence of Rubber Composition on Mechanical Properties. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 21, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Vassilopoulos, A.P.; Keller, T. Numerical modeling of two-dimensional delamination growth in composite laminates with in-plane isotropy. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2021, 250, 107787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.B.; Deng, X.L.; Cao, B.Y.; Feng, H.P.; Chen, J.; Li, P.D.; Ren, L.; Zhang, M.Y. Highly toughened PP/Rice husk charcoal composites modified Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer (EPDM) with glycidyl methacrylate. J. Polym. Res. 2024, 31, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondi, L.; Bernardi, F. Advanced hybrid laminates: Elastomer integration for optimized mechanical properties. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 136, 3177–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.; Elemam, H.; Seleem, M.H.; Sallam, H.E.D.M. Effect of fiber addition on strength and toughness of rubberized concretes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinç, Z.S.; Öz, Y.; Potluri, P.; Sampson, W.W.; Eren, H.A. Influence of thermoplastic fibre-epoxy adhesion on the interlaminar fracture toughness of interleaved polymer composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2024, 189, 108619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikry, M.J.M.; Arai, Y.; Inoue, R.; Vinogradov, V.; Tan, K.T.; Ogihara, S. Damage Behavior in Unidirectional CFRP Laminates with Ply Discontinuity. Appl. Compos. Mater. 2025, 32, 1481–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani, M.; Nosraty, H.; Mirdehghan, S.A.; Varkiani, S.M.H. Investigating the Interlaminar Fracture Toughness of Glass Fiber/Epoxy Composites Modified by Polypropylene Spunbond Nonwoven Fabric Interlayers. Fibers Polym. 2024, 25, 1061–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Sparrer, Y.; Rao, J.; Könemann, M.; Münstermann, S.; Lian, J. A forming limit framework accounting for various failure mechanisms: Localization, ductile and cleavage fracture. Int. J. Plast. 2024, 175, 103921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musale, A.; Hunashyal, A.M.; Patil, A.Y.; Kumar, R.; Ahamad, T.; Kalam, M.A.; Patel, M. Study on Nanomaterials Coated Natural Coir Fibers as Crack Arrestor in Cement Composite. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2024, 2024, 6686655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namrata, B.; Pai, Y.; Nair, V.G.; Hegde, N.T.; Pai, D.G. Analysis of aging effects on the mechanical and vibration properties of quasi-isotropic basalt fiber-reinforced polymer composites. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wdowiak-Postulak, A.; Świt, G.; Dziedzic-Jagocka, I. Application of Composite Bars in Wooden, Full-Scale, Innovative Engineering Products—Experimental and Numerical Study. Materials 2024, 17, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.; Oleiwi, J.K.; Mohammed, A.M.; Jawad, A.J.M.; Osman, A.F.; Adam, T.; Betar, B.O.; Gopinath, S.C.B. A Review on the Advancement of Renewable Natural Fiber Hybrid Composites: Prospects, Challenges, and Industrial Applications. J. Renew. Mater. 2024, 12, 1237–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Property | Typical Range/Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Plywood | Density | 550–800 kg m−3 | [26,27] |

| Modulus of Elasticity (E) | 6.9–13.1 GPa | ||

| Modulus of Rupture (MOR) | 20.7–48.3 MPa | ||

| Tensile Strength | 27.6–34.5 MPa | ||

| Coir Fiber Composite | Density | 1000–1250 kg m−3 | [4,7] |

| E | 2–5 GPa | ||

| MOR | 25–60 MPa | ||

| Tensile Strength | 20–50 MPa | ||

| Bamboo Mat Composite | Density | 850–1100 kg m−3 | [28,29] |

| E | 8–18 Gpa | ||

| MOR | 25–60 MPa | ||

| Tensile Strength | 40–90 MPa |

| Specimen | SBR-0 wt.% | SBR-5 wt.% | SBR-10 wt.% | SBR-15 wt.% | SBR-20 wt.% | SBR-25 wt.% | SBR-30 wt.% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Weight of Fiber | 80 (50% bamboo and 50% coir) | ||||||

| % Weight of PP | 20 | ||||||

| % Weight of SBR | 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 |

| Specimen | SBR-0 wt.% | SBR-5 wt.% | SBR-10 wt.% | SBR-15 wt.% | SBR-20 wt.% | SBR-25 wt.% | SBR-30 wt.% | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a0/L | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| a0 (mm) | 10 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 20 |

| a0/L | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Mean Peak Load (N) Pmax | Mean Midspan Deflection (mm) δmax | Mean Flexural Modulus (MPa) E′ | Mean Peak Load (N) Pmax | Mean Midspan Deflection (mm) δmax | Mean Flexural Modulus (MPa) E′ | Mean Peak Load (N) Pmax | Mean Midspan Deflection (mm) δmax | Mean Flexural Modulus (MPa) E′ |

| SBR 0% | 165 ± 2.1 | 3.50 ± 0.12 | 589.3 ± 21.6 | 150 ± 2.0 | 4.00 ± 0.14 | 468.8 ± 17.6 | 135 ± 1.8 | 4.50 ± 0.15 | 375.0 ± 13.5 |

| SBR 5% | 160 ± 1.9 | 3.60 ± 0.14 | 555.6 ± 22.6 | 145 ± 1.7 | 4.10 ± 0.12 | 442.1 ± 13.9 | 131 ± 1.9 | 4.65 ± 0.16 | 352.2 ± 13.1 |

| SBR 10% | 155 ± 2.0 | 3.72 ± 0.15 | 520.8 ± 22.1 | 141 ± 2.1 | 4.25 ± 0.13 | 414.7 ± 14.1 | 127 ± 2.0 | 4.80 ± 0.14 | 330.7 ± 11.0 |

| SBR 15% | 150 ± 1.8 | 3.85 ± 0.13 | 487.0 ± 17.5 | 136 ± 1.9 | 4.38 ± 0.15 | 388.1 ± 14.4 | 123 ± 1.8 | 4.95 ± 0.15 | 310.6 ± 10.5 |

| SBR 20% | 145 ± 2.2 | 3.98 ± 0.12 | 455.4 ± 15.4 | 132 ± 2.0 | 4.50 ± 0.14 | 366.7 ± 12.7 | 119 ± 2.1 | 5.10 ± 0.14 | 291.7 ± 9.5 |

| SBR 25% | 140 ± 2.1 | 4.10 ± 0.14 | 426.8 ± 15.9 | 127 ± 1.8 | 4.65 ± 0.13 | 341.4 ± 10.7 | 115 ± 2.0 | 5.25 ± 0.15 | 273.8 ± 9.2 |

| SBR 30% | 135 ± 2.0 | 4.25 ± 0.16 | 397.1 ± 16.1 | 123 ± 2.0 | 4.80 ± 0.16 | 320.3 ± 11.9 | 111 ± 1.9 | 5.40 ± 0.16 | 256.9 ± 8.8 |

| Plywood | 154 ± 2.3 | 3.80 ± 0.13 | 506.6 ± 18.9 | 140 ± 2.2 | 4.20 ± 0.14 | 416.7 ± 15.4 | 126 ± 2.1 | 4.85 ± 0.15 | 324.7 ± 11.4 |

| GIIc(kJ/m2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| SBR Content | a0/L = 0.2 | a0/L = 0.3 | a0/L = 0.4 |

| 0% | 1.0411 ± 0.1452 | 1.1064 ± 0.1533 | 1.0687 ± 0.1509 |

| 5% | 1.0887 ± 0.1140 | 1.2441 ± 0.1736 | 1.0773 ± 0.1513 |

| 10% | 1.1170 ± 0.1180 | 1.3503 ± 0.1900 | 1.1576 ± 0.1744 |

| 15% | 1.2198 ± 0.1276 | 1.5267 ± 0.2129 | 1.2871 ± 0.1980 |

| 20% | 1.3127 ± 0.1820 | 1.6365 ± 0.2277 | 1.3863 ± 0.2075 |

| 25% | 1.2521 ± 0.1672 | 1.6445 ± 0.2295 | 1.3582 ± 0.2056 |

| 30% | 1.3278 ± 0.1819 | 1.7292 ± 0.2416 | 1.4301 ± 0.2241 |

| Plywood | 0.8210 ± 0.1263 | 0.7402 ± 0.1033 | 0.6601 ± 0.1109 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bhargavi, C.; Sreekeshava, K.S.; Reddy, N.; Naik, N.D. Effect of Notch Depth on Mode II Interlaminar Fracture Toughness of Rubber-Modified Bamboo–Coir Composites. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 704. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120704

Bhargavi C, Sreekeshava KS, Reddy N, Naik ND. Effect of Notch Depth on Mode II Interlaminar Fracture Toughness of Rubber-Modified Bamboo–Coir Composites. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):704. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120704

Chicago/Turabian StyleBhargavi, C., K S Sreekeshava, Narendra Reddy, and Naveen Dyava Naik. 2025. "Effect of Notch Depth on Mode II Interlaminar Fracture Toughness of Rubber-Modified Bamboo–Coir Composites" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 704. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120704

APA StyleBhargavi, C., Sreekeshava, K. S., Reddy, N., & Naik, N. D. (2025). Effect of Notch Depth on Mode II Interlaminar Fracture Toughness of Rubber-Modified Bamboo–Coir Composites. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 704. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120704