Flame-Retardant Fiber-Reinforced Composites: Advances and Prospects in Multi-Performance Synergy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Flame Retardancy Test Methods

2.1. Limiting Oxygen Index (LOI) Test

2.2. UL-94 Vertical Burning Test

2.3. Cone Calorimeter (CCT) Test

2.4. Analysis of Fire Performance Index (FPI) and Average Effective Heat of Combustion (AEHC)

3. Flame-Retardant Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites (CFRPs)

3.1. Epoxy Resin-Based (EP) CFRP Flame-Retardant Composites

3.2. Polyamide-Based (PA) CFRP Flame-Retardant Composites

3.3. Other Resin-Based CFRP Flame-Retardant Composites

4. Flame-Retardant Composites of Glass Fiber Reinforced Polymers (GFRPs)

4.1. Epoxy Resin-Based (EP) GFRP Flame-Retardant Composites

4.2. Other Resin-Based GFRP Flame-Retardant Composites

5. Overview and Prospects of Flame-Retardant Strategies for Fiber-Reinforced Materials

5.1. Additive Flame-Retardant Approach

5.2. Intrinsic Flame-Retardant Approach

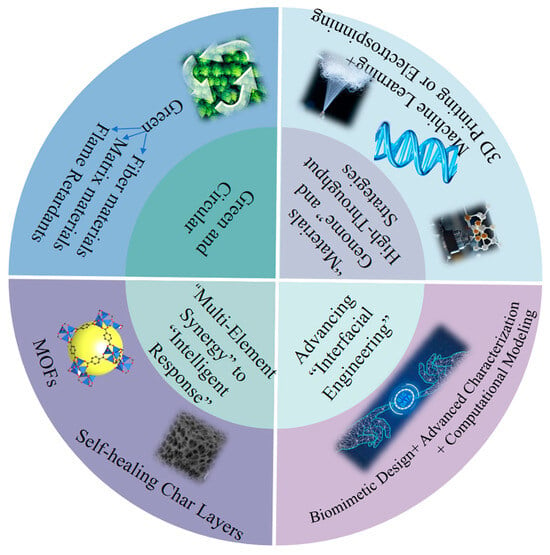

6. Future Directions for Flame-Retardant Fiber-Reinforced Materials

6.1. Lifecycle Design Philosophy Oriented Toward “Green and Circular” Principles

6.2. Evolving from “Multi-Element Synergy” to “Intelligent Response”

6.3. Advancing “Interfacial Engineering” to Overcome the Wick Effect

6.4. Implementing “Materials Genome” and High-Throughput Strategies in Flame Retardancy

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akbar, D.; Shabbir, F.; Raza, A.; Kahla, N.B. Synergistic enhancement of recycled aggregate concrete using hybrid natural-synthetic fiber reinforcement and silica fume. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, A.K.; Mustak, R.; Shaikh, M.S. Improving timber beam performance: Carbon and glass fiber reinforcement for enhanced strength and water resistance. Next Res. 2025, 2, 100389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerer, B.; Matz, P.; Kupelwieser, F.; Al-Musawi, H.; Praxmarer, G.; Hartmann, S.; Müller, U. Developing a bio-based, continuous fibre reinforcement to push the impact energy limits of engineered wood in structural applications. Compos. Part B Eng. 2025, 303, 112536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, H.; Shobeiri, V.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Bai, Y.; Robert, D.; Xie, Y.M. CFRP-confined rammed earth towards high-performance earth construction. Compos. Struct. 2025, 371, 119512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.; Ji, Z.; Rupp, F.; Caydamli, Y.; Heudorfer, K.; Gompf, B.; Carosella, S.; Buchmeiser, M.R.; Middendorf, P. Optimizing transparent fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A machine learning approach to material selection. Compos. Part B Eng. 2025, 307, 112799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Wen, W.; Wang, K.; Peng, Y.; Ahzi, S.; Chinesta, F. Tailoring interfacial properties of 3D-printed continuous natural fiber reinforced polypropylene composites through parameter optimization using machine learning methods. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 32, 103985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, M.; Yang, X.; Fan, R.; Yue, S.; Zheng, L.; Liu, Q.; He, Y. A comprehensive review of reactive flame-retardant epoxy resin: Fundamentals, recent developments, and perspectives. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2022, 201, 109976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, C.; Li, J.; Fang, K.; Zhu, Q.; Zhu, J.; Yan, Q. Enhancement of a hyperbranched charring and foaming agent on flame retardancy of polyamide 6. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2011, 22, 2237–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.-H.; Li, X.-L.; Li, Y.-M.; Li, Z.; Wang, D.-Y. Flame-retardant strategy and mechanism of fiber reinforced polymeric composite: A review. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 233, 109663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Tian, Y.; Yan, Y. Preparation and characterization of rigid polyimide foams --comparison of additive and reactive flame retardants and its application in sound absorption. Polymer 2025, 334, 128726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabipour, H.; Rohani, S. Biodrived flame retardants for epoxy resins: Phosphorus-containing additives for enhanced fire safety. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahabi, H.; Wu, H.; Saeb, M.R.; Koo, J.H.; Ramakrishna, S. Electrospinning for developing flame retardant polymer materials: Current status and future perspectives. Polymer 2021, 217, 123466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Su, Y.; Chen, F.; Yang, K. Axial compressive test and a new stress-strain model of CFRP-confined damaged high-strength concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 490, 142476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Dong, W.; Liu, C.; Xing, Y.; Sun, J.; Liang, X.; Duan, H.; Jia, X. A critical review on additive manufacturing of continuous fiber-reinforced polymer composites: Materials, fabrication, structural design and novel functions. Thin-Walled Struct. 2025, 215, 113491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Pan, Y.-T.; Liu, L.; Song, P.; Yang, R. Metal-organic frameworks and their derivatives for sustainable flame-retardant polymeric materials. Adv. Nanocomposites 2025, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Pan, Y.-T.; Wang, W.; Yang, R. Surface modification of MOFs towards flame retardant polymer composites. RSC Appl. Interfaces 2024, 2, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.I.; Sidhu, H.S.; Weber, R.O.; Mercer, G.N. A dynamical systems model of the limiting oxygen index test. ANZIAM J. 2001, 43, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Búcsi, A.; Rychlý, J. A theoretical approach to understanding the connection between ignitability and flammability parameters of organic polymers. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1992, 38, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D2863-23; Standard Test Method for Measuring the Minimum Oxygen Concentration to Support Candle-Like Combustion of Plastics (Oxygen Index). ASTM Compass: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025.

- ANSI/UL 94-2020; Standard for Tests for Flammability of Plastic Materials for Parts in Devices and Appliances. UL Standards & Engagement: Evanston, IL, USA, 2024.

- ASTM E1354-23; Standard Test Method for Heat and Visible Smoke Release Rates for Materials and Products Using an Oxygen Consumption Calorimeter. ASTM Compass: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025.

- Zhao, Q.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Hou, Y.; Li, J.; Li, C. Multiscale modeling framework to predict the low-velocity impact and compression after impact behaviors of plain woven CFRP composites. Compos. Struct. 2022, 299, 116090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzberg, T. Dangers relating to fires in carbon-fibre based composite material. Fire Mater. 2005, 29, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Wang, L.; Li, T.; Wei, B. Molecular investigation on the compatibility of epoxy resin with liquid oxygen. Theor. Appl. Mech. Lett. 2020, 10, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.; Ahn, K.J.; Nam, J.D.; Chun, H.J. Hygroscopic aspects of epoxy/carbon fiber composite laminates in aircraft environments. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2001, 32, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daelemans, L.; van der Heijden, S.; De Baere, I.; Rahier, H.; Van Paepegem, W.; De Clerck, K. Nanofibre bridging as a toughening mechanism in carbon/epoxy composite laminates interleaved with electrospun polyamide nanofibrous veils. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2015, 117, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Peng, J.; Liu, J.; Hao, X.; Guo, C.; Ou, R.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Q. Fully recyclable, flame-retardant and high-performance carbon fiber composites based on vanillin-terminated cyclophosphazene polyimine thermosets. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 224, 109188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, D.; Yue, D.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, G.; Alderliesten, R. On the mix-mode fracture of carbon fibre/epoxy composites interleaved with various thermoplastic veils. Compos. Commun. 2022, 33, 101230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.-L.; Chen, C.-K.; Chen, X.-L. Effects of carbon fibers on the flammability and smoke emission characteristics of halogen-free thermoplastic polyurethane/ammonium polyphosphate. J. Mater. Sci. 2016, 51, 3762–3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levchik, S.V.; Weil, E.D. Thermal decomposition, combustion and flame-retardancy of epoxy resins—A review of the recent literature. Polym. Int. 2004, 53, 1901–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laoutid, F.; Bonnaud, L.; Alexandre, M.; Lopez-Cuesta, J.M.; Dubois, P. New prospects in flame retardant polymer materials: From fundamentals to nanocomposites. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2009, 63, 100–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

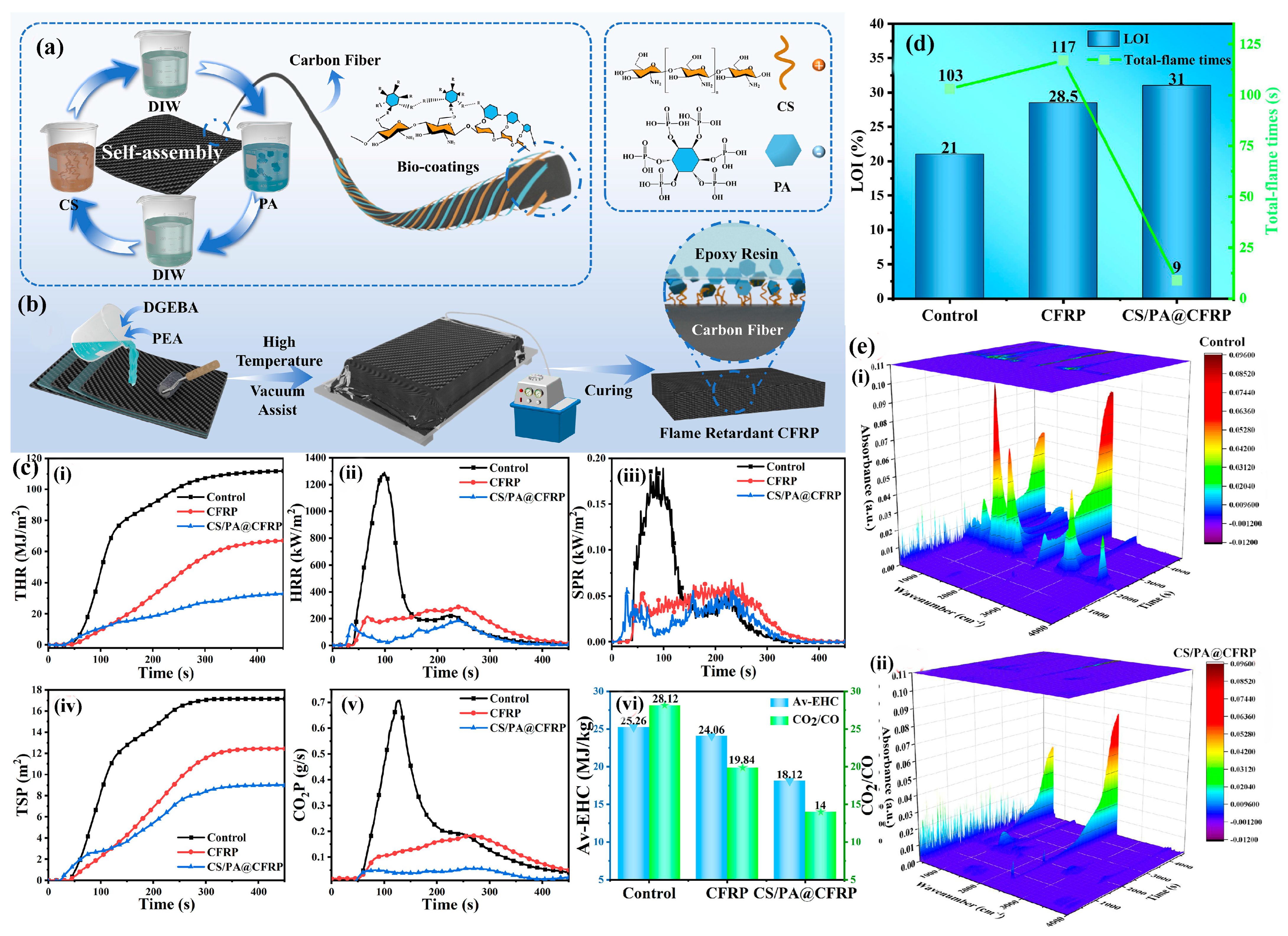

- Li, M.; Shi, H.; Su, Y.; He, L.; Guo, W. Whole biomass interface engineering: Construction of flame retardant and high-strength carbon fiber reinforced epoxy resin composites via layer by layer self-assembly. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2025, 240, 111481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zhang, M.; Jin, L.; Liu, L.; Li, N.; Shang, L.; Li, M.; Xiao, L.; Ao, Y. Enhancing interfacial properties of carbon fibers reinforced epoxy composites via Layer-by-Layer self assembly GO/SiO2 multilayers films on carbon fibers surface. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 470, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Meng, X.; Han, Z.; Qi, Y.; Li, Z.; Tian, P.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; et al. Designing Fe-containing polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane to endow superior mechanical and flame-retardant performances of polyamide 1010. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2023, 233, 109894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Tan, J.; Wang, J.; Chang, W.; Islam, M.S.; Sha, Z.; Wang, C.; Lin, B.; Zhang, J.; Yeoh, G.H.; et al. Enhancing mechanical and flame retardant properties of carbon fibre epoxy composites with functionalised ammonium polyphosphate nanoparticles. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2025, 261, 111005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chang, W.; Zhang, J.; Heng Yeoh, G.; Boyer, C.; Wang, C.H. A novel strategy for high flame retardancy and structural strength of epoxy composites by functionalizing ammonium polyphosphate (APP) using an amine-based hardener. Compos. Struct. 2024, 327, 117710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, B.; Qian, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, W.; Zhong, S.; Li, J.; Chu, F.; Kan, Y.; Chen, J.; Hu, Y. Quantitative assessment of whether phosphorus-based flame retardants are optimizing or degrading the fire hazard of aircraft carbon fiber/epoxy composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 279, 111413. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, P.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, J.; Wang, B.; Song, L.; Wang, B.; Hu, Y. Multifunctional fireproof electromagnetic shielding polyurethane films with thermal management performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 439, 135673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Gao, Z.; Xie, W.; Shi, X.; Zhang, O.; Shen, Z.; Fang, L.; Ren, M.; Sun, J. A novel strategy utilizing oxidation states of phosphorus for designing efficient phosphorus-containing flame retardants and its performance in epoxy resins. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2024, 230, 111016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, D.L.; Paiva, L.B.; Aldeia, W. Advances in polyamide nanocomposites: A review. Polym. Compos. 2019, 40, 851–870. [Google Scholar]

- Kausar, A. Advances in Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polyamide-Based Composite Materials. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2019, 19, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Fan, X.; Yu, L. Preparation and properties of continuous glass fiber reinforced anionic polyamide-6 thermoplastic composites. Mater. Des. (1980–2015) 2013, 46, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Cao, W.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, T. Synthesis and Application of Hybrid Aluminum Dialkylphosphinates as Highly Efficient Flame Retardants for Polyamides. Polymers 2023, 15, 4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Huang, H.; Zhu, L.; Liu, Z. Integrating carbon fiber reclamation and additive manufacturing for recycling CFRP waste. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 215, 108808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Xu, B.; Zhao, W.; Wang, G. Enhancing flame retardancy in 3D printed polyamide composites using directionally arranged recycled carbon fiber. Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 287, 111854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoffroy, L.; Samyn, F.; Jimenez, M.; Bourbigot, S. Additive manufacturing of fire-retardant ethylene-vinyl acetate. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2019, 30, 1878–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fu, Y.; Pi, W.; Li, Y.; Fu, S. Improving mechanical performances at room and elevated temperatures of 3D printed polyether-ether-ketone composites by combining optimal short carbon fiber content and annealing treatment. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 267, 111067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Ji, C.; Yu, T.; Li, Y.; Liu, X. The unique wick effect and combustion behavior of flax fiber reinforced composites: Experiment and simulation. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 265, 110954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avenet, J.; Levy, A.; Bailleul, J.-L.; Le Corre, S.; Delmas, J. Adhesion of high performance thermoplastic composites: Development of a bench and procedure for kinetics identification. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2020, 138, 106054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.-T.; Li, J.; Guo, F.-L.; Li, Y.-Q.; Fu, S.-Y. Micro-structure and tensile property analyses of 3D printed short carbon fiber reinforced PEEK composites. Compos. Commun. 2023, 41, 101655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Peng, X.; Yin, D.; Jin, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Jin, M.; et al. A review of the recent developments in flame-retardant nylon composites. Compos. Part C Open Access 2022, 9, 100297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.-J.; Yuan, Y.; Guan, J.-P.; Cheng, X.-W.; Chen, G.-Q. Preparation of durable coating for polyamide 6: Analysis the role of DOPO on flame retardancy, anti-dripping and combustion behavior. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2023, 215, 110418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zhao, R.; Cai, S.; Ning, X. An applicability study on various methods for determining the monomer conversion rate of polyamide 6. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, Z.; Toldy, A. Synergistic flame retardant coatings for carbon fibre-reinforced polyamide 6 composites based on expandable graphite, red phosphorus, and magnesium oxide. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2024, 222, 110696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, Z.; Toldy, A. Synergistic flame retardant coatings for carbon fibre-reinforced ε-caprolactam-based polyamide 6 composites: Fire performance and mechanical properties. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2025, 240, 111495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, W. Experimental investigation of mechanical, thermal, and flame-retardant property of polyamide 6/phenoxyphosphazene fibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 48458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zheng, L.; Ma, H.; Lu, Z.; Xu, F. 3D orthogonal woven carbon fiber/PEEK composites with superior bending and flame-retardant properties. Compos. Struct. 2023, 324, 117559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, C.; Zulkifli, F.; Silva, A. Effects of processing parameters of infrared-based automated fiber placement on mechanical performance of carbon fiber-reinforced thermoplastic composite. Compos. Struct. 2023, 309, 116725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Hull, T.R.; McCabe, R.W.; Flath, D.; Grasmeder, J.; Percy, M. Mechanism of thermal decomposition of poly(ether ether ketone) (PEEK) from a review of decomposition studies. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2010, 95, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Sang, M.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Liu, S.; Hu, Y.; Gong, X. Flexible and lightweight Kevlar composites towards flame retardant and impact resistance with excellent thermal stability. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.-N.; Kou, S.-Q.; Yang, H.-Y.; Xu, Z.-B.; Shu, S.-L.; Qiu, F.; Jiang, Q.-C.; Zhang, L.-C. High-content continuous carbon fibers reinforced PEEK matrix composite with ultra-high mechanical and wear performance at elevated temperature. Compos. Struct. 2022, 295, 115837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, H.; Qiu, Y.; Tai, X.; Wang, L.; Qian, L.; Tang, W.; Wang, J.; Xi, W.; Qu, L. Polyphenylene sulfide alloying and carbon fiber reinforcing together promote polycarbonate towards superior flame retardant composite with good mechanics. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2025, 240, 111501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

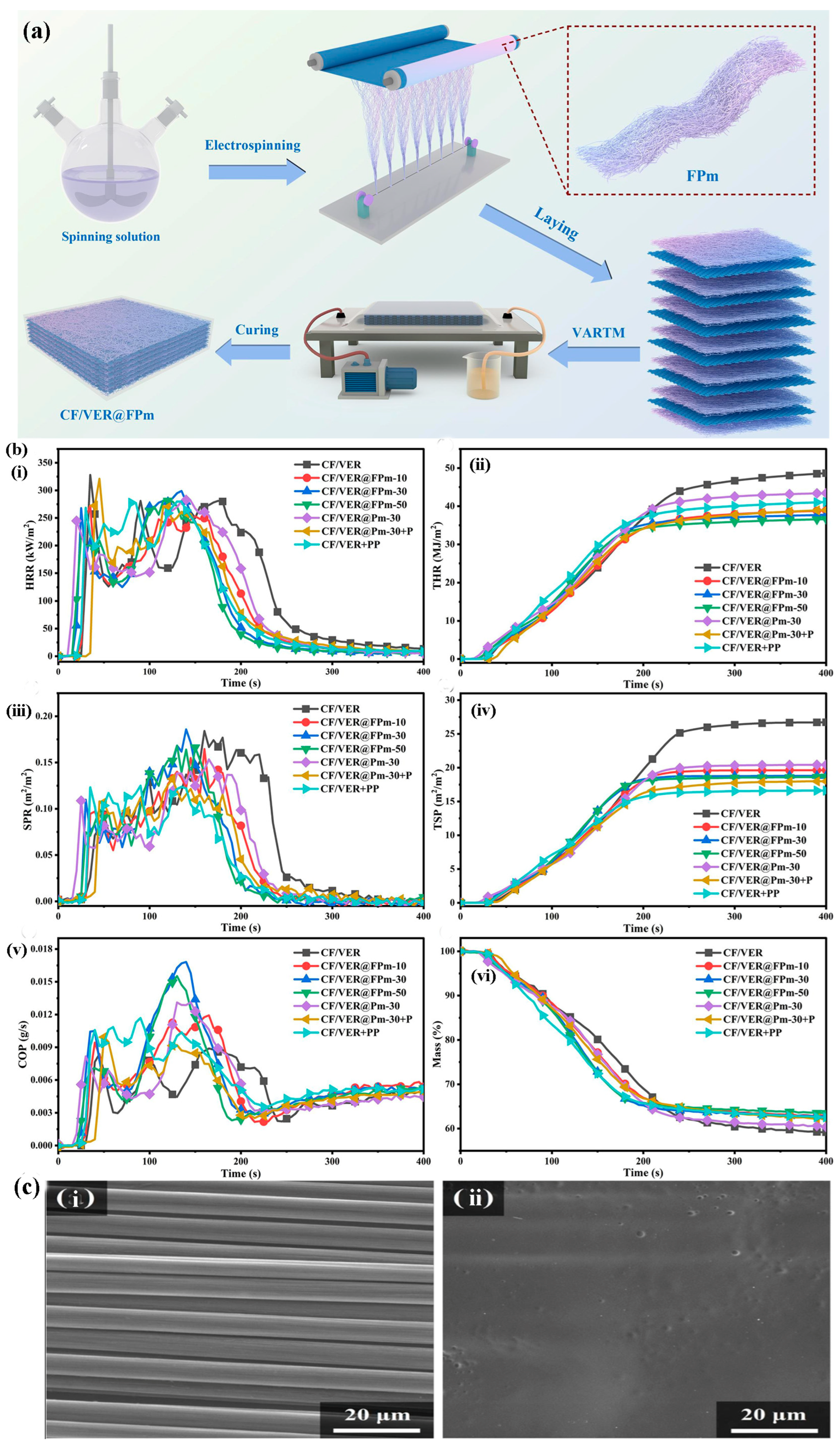

- Yu, M.; Chu, Y.; Xie, W.; Fang, L.; Zhang, L.; Ren, M.; Sun, J. Integrated design of flame retardancy, smoke suppression and structure of carbon fiber reinforced vinyl ester resin composites through intercalation of nanofiber membranes. Compos. Struct. 2024, 349–350, 118531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chu, F.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, W.; Hu, Y. Interfacial flame retardant unsaturated polyester composites with simultaneously improved fire safety and mechanical properties. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 426, 131313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, D.S.; Suzuki, Y.; Murray, R.E.; Samaniuk, J.R.; Stebner, A.P. Recycling glass fiber thermoplastic composites from wind turbine blades. J. Clean Prod. 2019, 209, 1252–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, M.; Choudhary, P.; Krishnan, V.; Zafar, S. A review on recycling and reuse methods for carbon fiber/glass fiber composites waste from wind turbine blades. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 215, 108768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Li, F.; Hu, N.; Fu, S.-Y. Frictional characteristics of graphene oxide-modified continuous glass fiber reinforced epoxy composite. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 223, 109446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnati, S.R.; Agbo, P.; Zhang, L. Applications of silica nanoparticles in glass/carbon fiber-reinforced epoxy nanocomposite. Compos. Commun. 2020, 17, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.-T.; Shi, H.-J.; Wang, W.; Liu, Q.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, X. Glass fiber-reinforced epoxy composites with high thermal conductivity, flame retardancy and mechanical strength. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2025, 194, 108905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.S.; Zou, S.; Enman, L.J.; Kellon, J.E.; Gabor, C.A.; Pledger, E.; Boettcher, S.W. Revised Oxygen Evolution Reaction Activity Trends for First-Row Transition-Metal (Oxy)hydroxides in Alkaline Media. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 3737–3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, M.; Yang, X.; Su, B.; Yue, S.; Liu, Q.; Chen, X. Intrinsic flame-retardant epoxy resin composite containing schiff base structure with satisfied flame retardancy and mechanical properties. Polym. Test. 2024, 134, 108437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel Yilmaz, A.N.; Celik Bedeloglu, A.; Yunus, D.E. Enhancing mechanical and flame retardant characteristics of glass fiber-epoxy laminated composites through MXene and functionalized-MXene integration. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 108745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguib, M.; Kurtoglu, M.; Presser, V.; Lu, J.; Niu, J.; Heon, M.; Hultman, L.; Gogotsi, Y.; Barsoum, M.W. Two-Dimensional Nanocrystals Produced by Exfoliation of Ti3AlC2. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 4248–4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnier, L.; Cossard, G.; Martin, V.; Pascal, C.; Roche, V.; Sibert, E.; Shchedrina, I.; Bousquet, R.; Parry, V.; Chatenet, M. Fe–Ni-based alloys as highly active and low-cost oxygen evolution reaction catalyst in alkaline media. Nat. Mater. 2024, 23, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priyadarshini, S.; Soren, S.; Durga, G. Effect of graphene and MXene as 2D filler material on physico-mechanical properties of hemp/E-glass fibers reinforced hybrid composite: A comparative study. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 2685–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.-M.; Vahid, M.H.; Sun, Y.-L.; Heidari, A.; Barbaz-Isfahani, R.; Saber-Samandari, S.; Khandan, A.; Toghraie, D. Investigation on the effect of functionalization of single-walled carbon nanotubes on the mechanical properties of epoxy glass composites: Experimental and molecular dynamics simulation. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 12, 1931–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

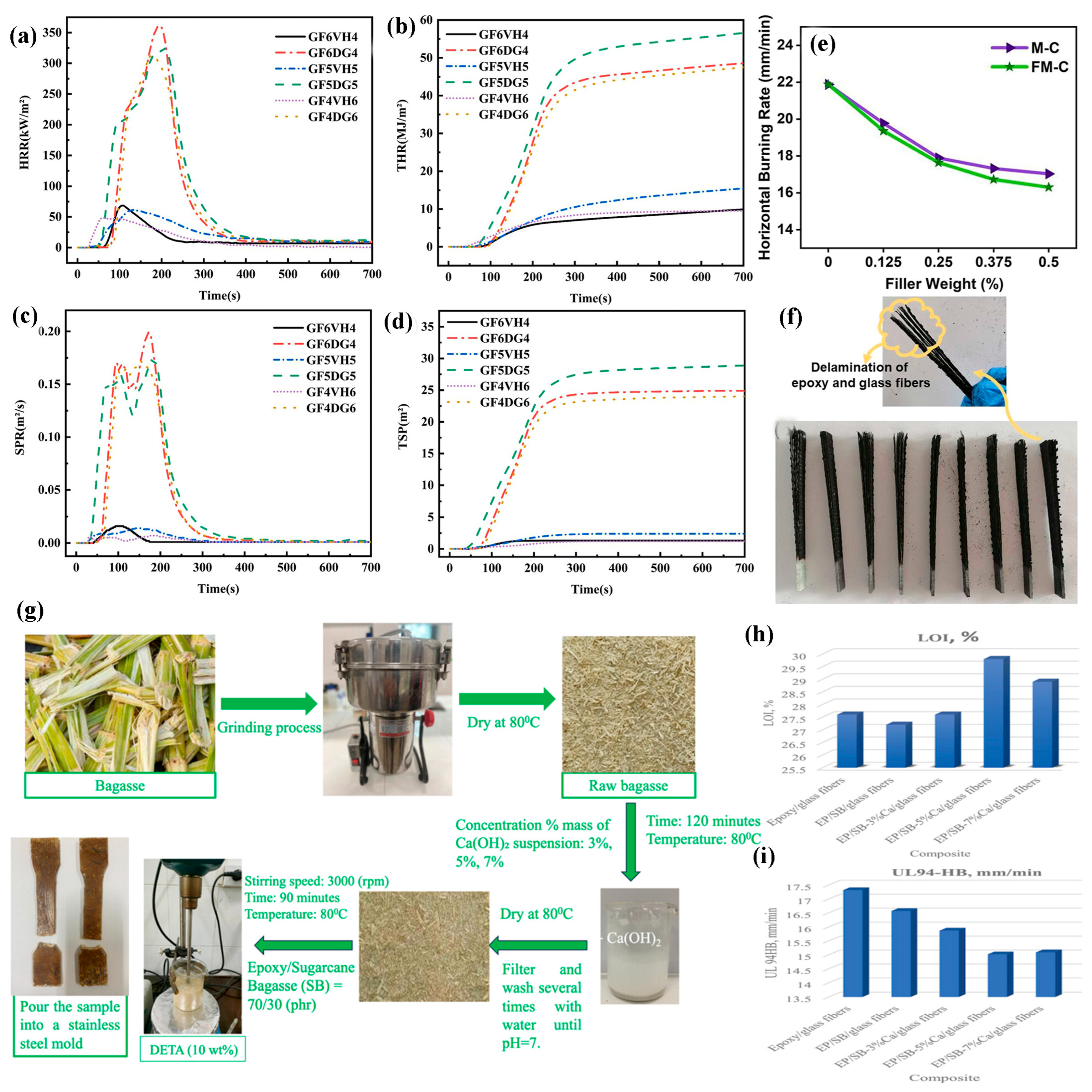

- Nguyen, T.A.; Oanh, D.T.Y.; Van Ngo, T.; Nguyen, T.T.P.; Nguyen, M.V.; Nguyen, T.H.; Bui, T.T.T.; Le, T.H.N.; Nguyen, M.H.; Nguyen, Q.T. Enhancing epoxy composite materials through lime-treated sugarcane bagasse and glass fiber reinforcement: Morphological, mechanical, and flame-retardant insights. Vietnam J. Chem. 2025, 63, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, A.; Khandoker, N.; Debnath, S. Development and characterization of sugarcane bagasse fiber and nano-silica reinforced epoxy hybrid composites. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 344, 12029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, E.; Baptista, C.; Mulinari, D. Mechanical behaviour of polypropylene reinforced sugarcane bagasse fibers composites. Procedia Eng. 2011, 10, 2046–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, D.G.; Terzopoulou, Z.; Fina, A.; Cuttica, F.; Papageorgiou, G.Z.; Bikiaris, D.N.; Chrissafis, K.; Young, R.J.; Kinloch, I.A. Enhanced thermal and fire retardancy properties of polypropylene reinforced with a hybrid graphene/glass-fibre filler. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2018, 156, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.-Q.; Zhao, Y.-Z.; Xu, Y.-J.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, P. Flame retardation of vinyl ester resins and their glass fiber reinforced composites via liquid DOPO-containing 1-vinylimidazole salts. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 234, 109697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, L.; Li, C. Flame retardant synergy between interfacial and bulk carbonation in glass fiber reinforced polypropylene. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 28, 1725–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, H.; Ni, A.; Ding, A. Synergistic effect of intumescent flame retardant and attapulgite on mechanical properties and flame retardancy of glass fibre reinforced polyethylene composites. Compos. Struct. 2020, 246, 112404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhang, Y.-R.; Yuen, A.C.-Y.; Chen, T.B.-Y.; Chan, M.-C.; Peng, L.-Z.; Yang, W.-J.; Zhu, S.-E.; Yang, B.-H.; Hu, K.-H.; et al. Synthesis of phosphorus-containing silane coupling agent for surface modification of glass fibers: Effective reinforcement and flame retardancy in poly(1,4-butylene terephthalate). Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 321, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Sabee, M.M.S.; Itam, Z.; Beddu, S.; Zahari, N.M.; Mohd Kamal, N.L.; Mohamad, D.; Zulkepli, N.A.; Shafiq, M.D.; Abdul Hamid, Z.A. Flame Retardant Coatings: Additives, Binders, and Fillers. Polymers 2022, 14, 2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattar, A.; Hafeez, S.; Hedar, M.; Saeed, M.; Hussain, T.; Intisar, A. Polymer/POSS based robust and emerging flame retardant nanocomposites: A comprehensive review. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects 2025, 41, 101427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-H.; Jung, C.-H.; Kim, D.-K.; Suh, D.-H.; Nho, Y.-C.; Kang, P.-H.; Ganesan, R. Preparation of polymer/POSS nanocomposites by radiation processing. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2009, 78, 517–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhuang, D.; Zhou, Y.; Liao, J.; Dai, S.; Pan, C.; Li, Y.; Dai, L.; Wang, W. Mechanically reinforced and flame-retardant epoxy resin nanocomposite based on molecular engineering of POSS. Polym. Test. 2025, 143, 108719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combeau, M.; Batistella, M.; Breuillac, A.; Naess, M.K.; Perrin, D.; Lopez-Cuesta, J.-M. POSS in intumescent flame-retardant systems to improve fire behaviour of virgin and recycled high density polyethylene. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2025, 233, 111177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappan, T. Fire Retardant Coatings. In New Technologies in Protective Coatings; Giudice, C.A., Canosa, G., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Manivannan, S. Flame-retardant coatings: Recent advances in materials, mechanisms, and multifunctional applications. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 209, 109572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeri, Z.; Ramezanzadeh, B.; Ramezanzadeh, M. Recent progress on the metal-organic frameworks decorated graphene oxide (MOFs-GO) nano-building application for epoxy coating mechanical-thermal/flame-retardant and anti-corrosion features improvement. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 163, 106645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Qi, P.; Yan, Y.; Wang, R. Hierarchical bio-based flame retardant BNNS@PA@Fe-MOFs: A nanomaterials self-assembly strategy towards reducing fire hazard of polylactic acid and improving its degradation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 332, 148266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Wu, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Dai, C.; Han, B.; Hu, J.; Liang, L.; Ma, M.; Pan, Y.-T. Interface engineering using MOFs to bionically construct ultra-rough nanostructures to enhance the flame retardancy and mechanical properties of polyurea. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 48, 113341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Li, J.; Dai, C.; Han, B.; Hu, J.; Liang, L.; Ma, M.; Pan, Y.-T. “Two-birds-one-stone” strategy: Phytic acid-chelated MOFs and NiMoO4 nanorods integrated polyurea for multifunctional flame retardancy, mechanical, and UV protection. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 523, 168471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, T.; Anwar, M.T. Metal organic frameworks as self-sacrificing modalities for potential environmental catalysis and energy applications: Challenges and perspectives. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 480, 215011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, W.; Pan, Y.-T.; Huo, S.; Shi, C. MOF-based nanocomposites in polymer matrix: Progress and prospects. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2025, 8, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xiao, J.; Zhong, G.; Xu, T.; Zhang, X. Design and application of dual-emission metal–organic framework-based ratiometric fluorescence sensors. Analyst 2024, 149, 1381–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, H.; Li, J.; Jin, M.; Ren, J. Eugenol-derived trifunctional epoxy resin: Intrinsic phosphorus-free flame retardancy and mechanical reinforcement for sustainable polymer alternatives. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2025, 239, 111394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Roy, S.; Agumba, D.O.; Pham, D.H.; Kim, J. Effect of bio-based derived epoxy resin on interfacial adhesion of cellulose film and applicability towards natural jute fiber-reinforced composites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 222, 1304–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Guo, W.; Wang, X.; Song, L.; Hu, Y. Intrinsically flame retardant cardanol-based epoxy monomer for high-performance thermosets. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2021, 186, 109519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Jin, C.; Huo, S.; Kong, Z.; Chu, F. Preparation and properties of novel bio-based epoxy resin thermosets from lignin oligomers and cardanol. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 193, 1400–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.-J.; Zhang, K.-T.; Wang, J.-R.; Wang, Y.-Z. Biopolymer-Based Flame Retardants and Flame-Retardant Materials. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2414880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, S.; Ma, J.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, R. Investigation on UV/flame retardant protection of outdoor-applied cotton fabrics by tannic acid/phytic acid system. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.L.; Li, S.; Qiu, T.R.; Tan, Y.Q. Effects of plastic coating on the physical and mechanical properties of the artificial aggregate made by fly ash. J. Clean Prod. 2022, 360, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.J.; Mai, D.J.; Li, S.L.; Morris, M.A.; Olsen, B.D. Tuning Selective Transport of Biomolecules through Site-Mutated Nucleoporin-like Protein (NLP) Hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Yang, W.; Lee, S.H.; Lum, W.C.; Du, G.; Ren, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J. Reactive bio-based flame retardant derived from chitosan, phytic acid, and epoxidized soybean oil for high-performance biodegradable foam. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 307, 142137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Murugesan, B.; Mo, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Cai, Y. Bio-based vanillin-derived nitrogen-phosphorus synergism: A sustainable flame-retardant strategy for high-performance thermoplastic polyurethane. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 208, 109528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yan, W.-J.; Zhong, C.-Z.; Chen, C.-R.; Luo, Q.; Pan, Y.-T.; Tang, Z.-H.; Xu, S. Construction of TiO2-based decorated with containing nitrogen-phosphorus bimetallic layered double hydroxides for simultaneously improved flame retardancy and smoke suppression properties of EVA. Mater. Today Chem. 2024, 36, 101952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Zhang, Z.; Song, K.; Zhang, X.; Pan, Y.-T.; Qu, H.; Vahabi, H.; He, J.; Yang, R. Packaging of ZIF-8 into diatomite sealed by ionic liquid and its application in flame retardant polyurea composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2024, 184, 108283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Trevino, A.; Qiao, Y.; Seffens, R.J.; Engelhard, M.H.; Gilliam, M.; Garner, G.; Lukitsch, M.; Carlson, B.E.; Simmons, K.L. Enhanced adhesive bonding at the adhesive-CFRTP interface via plasma and silane coupling agents in adhesively-bonded metal-CFRTP joints. Compos. Part B Eng. 2026, 308, 113009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic Dimension | Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) | Glass Fiber Reinforced Polymer (GFRP) | Natural Fiber Reinforced Polymer (NFRPC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Function Positioning | Synergy of High Performance and Flame Retardancy | Balance of Cost, Function, and Flame Retardancy | Unification of Green Sustainability and Flame Retardancy |

| Characteristic Flame Retardant Types |

|

|

|

| Key Flame Retardancy Mechanism | Primarily condensed phase char formation, supplemented by gas phase inhibition. Forms a dense char layer to block heat and mass transfer and trap radicals. | Gas phase inhibition is crucial for extinguishing flames induced by the “wick effect”; condensed phase char formation serves as a supplement. | Strong catalytic char formation is key, building a protective layer to shield the flammable natural fibers. |

| Performance Synergy Effects | Enhances flame retardancy while maintaining high mechanical properties; can even use flame retardants to improve fiber/matrix interface. | While achieving flame retardancy, it can impart properties like high thermal conductivity, excellent smoke suppression, or higher arc resistance. | Combines flame retardancy with material biodegradability, renewability, and environmental friendliness. |

| Unique Functional Advantages | Enables structural-functional integration, providing integrated load-bearing and fire protection solutions for high-end equipment. | Mature technology, controllable cost, and easy-to-achieve flame-retardant functional modification in general industrial fields. | Meets the highest environmental standards, an ideal choice for the circular economy and green design. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Han, F.; Li, H.; Li, T.; Yang, B.; Hu, J.; Pan, Y.-T. Flame-Retardant Fiber-Reinforced Composites: Advances and Prospects in Multi-Performance Synergy. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 703. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120703

Zhang Z, Han F, Li H, Li T, Yang B, Hu J, Pan Y-T. Flame-Retardant Fiber-Reinforced Composites: Advances and Prospects in Multi-Performance Synergy. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):703. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120703

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zihan, Feng Han, Haoran Li, Tianyu Li, Boran Yang, Jinhu Hu, and Ye-Tang Pan. 2025. "Flame-Retardant Fiber-Reinforced Composites: Advances and Prospects in Multi-Performance Synergy" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 703. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120703

APA StyleZhang, Z., Han, F., Li, H., Li, T., Yang, B., Hu, J., & Pan, Y.-T. (2025). Flame-Retardant Fiber-Reinforced Composites: Advances and Prospects in Multi-Performance Synergy. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 703. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120703