Comprehensive Study of Silver Nanoparticle Functionalization of Kalzhat Bentonite for Medical Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Purification of Kzh Bentonite by D.P. Salo Method

2.2.2. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles

2.2.3. Modification of Kzh Bentonite by AgNPs

2.3. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

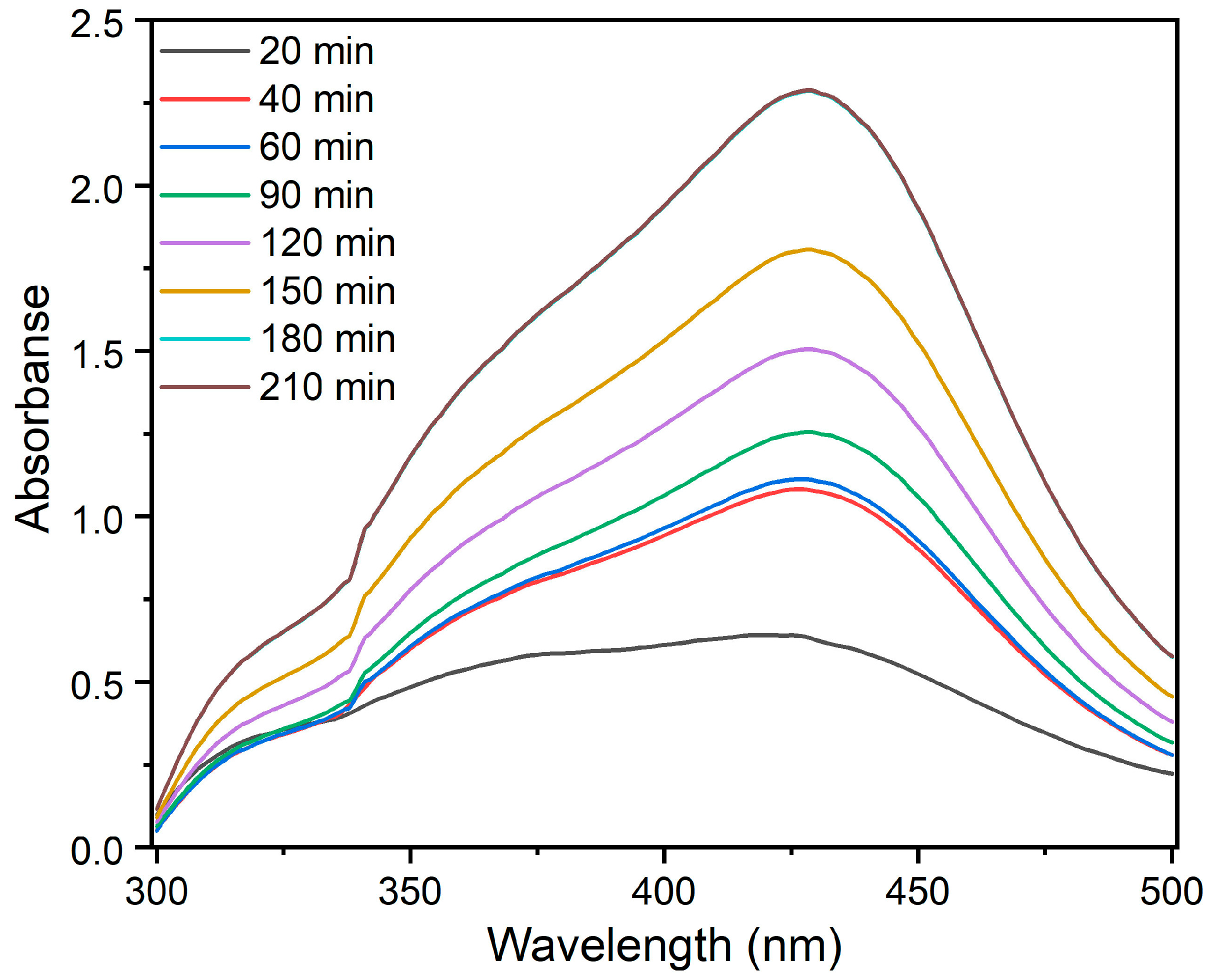

3.1. Synthesis of AgNPs

3.2. FTIR Analysis

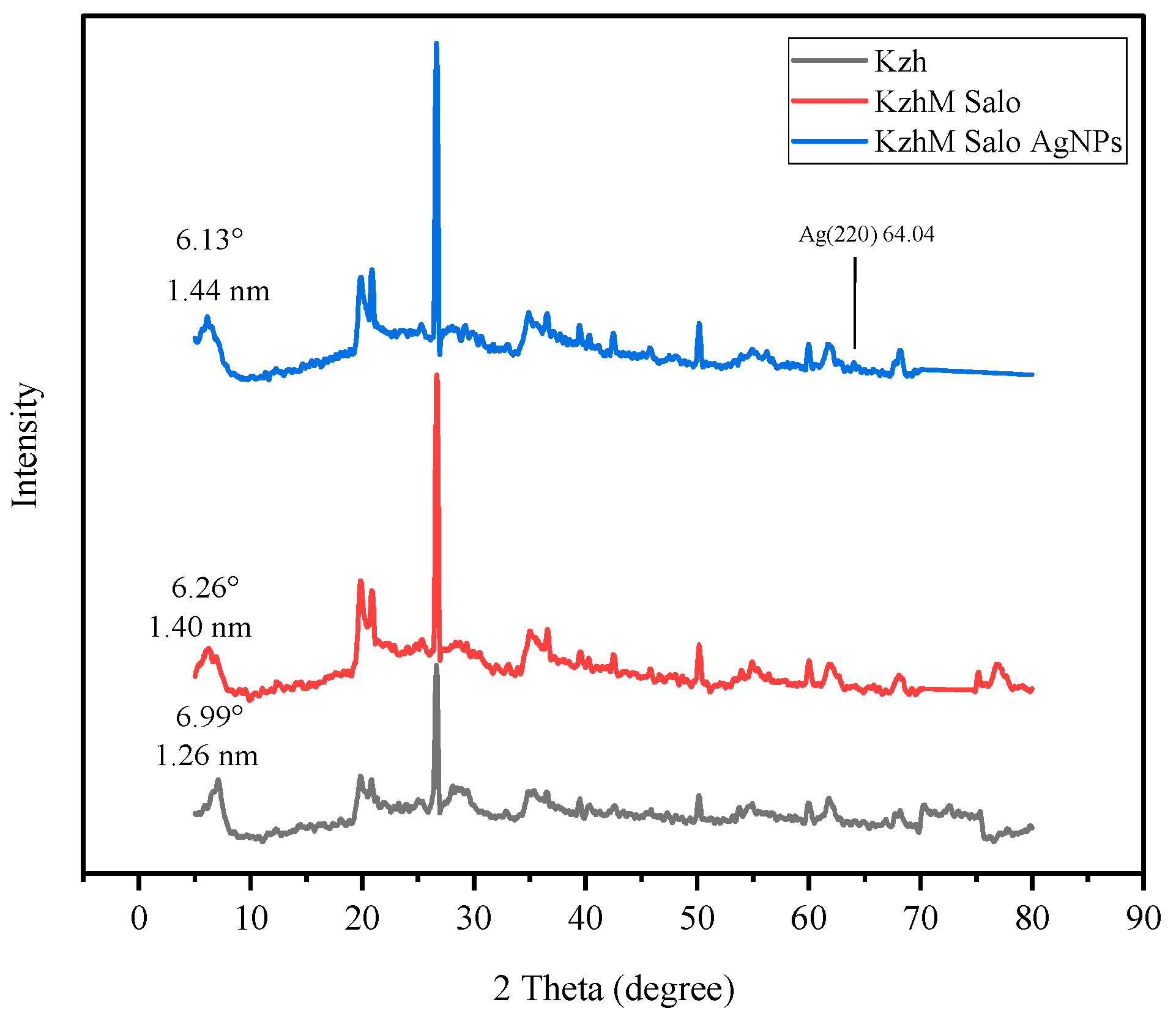

3.3. XRD

3.4. Determination of Elemental Composition of Bentonites

3.5. SEM Analysis

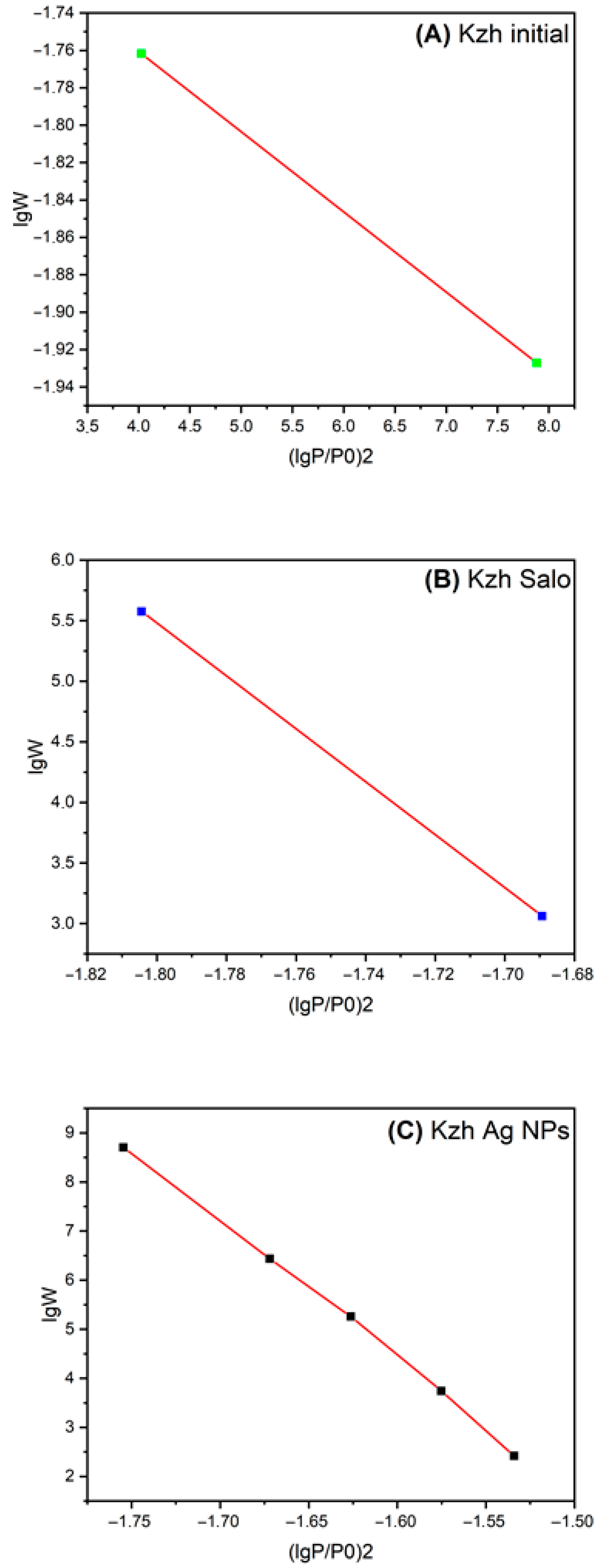

3.6. BET Analysis

3.7. Zeta Potential Analysis

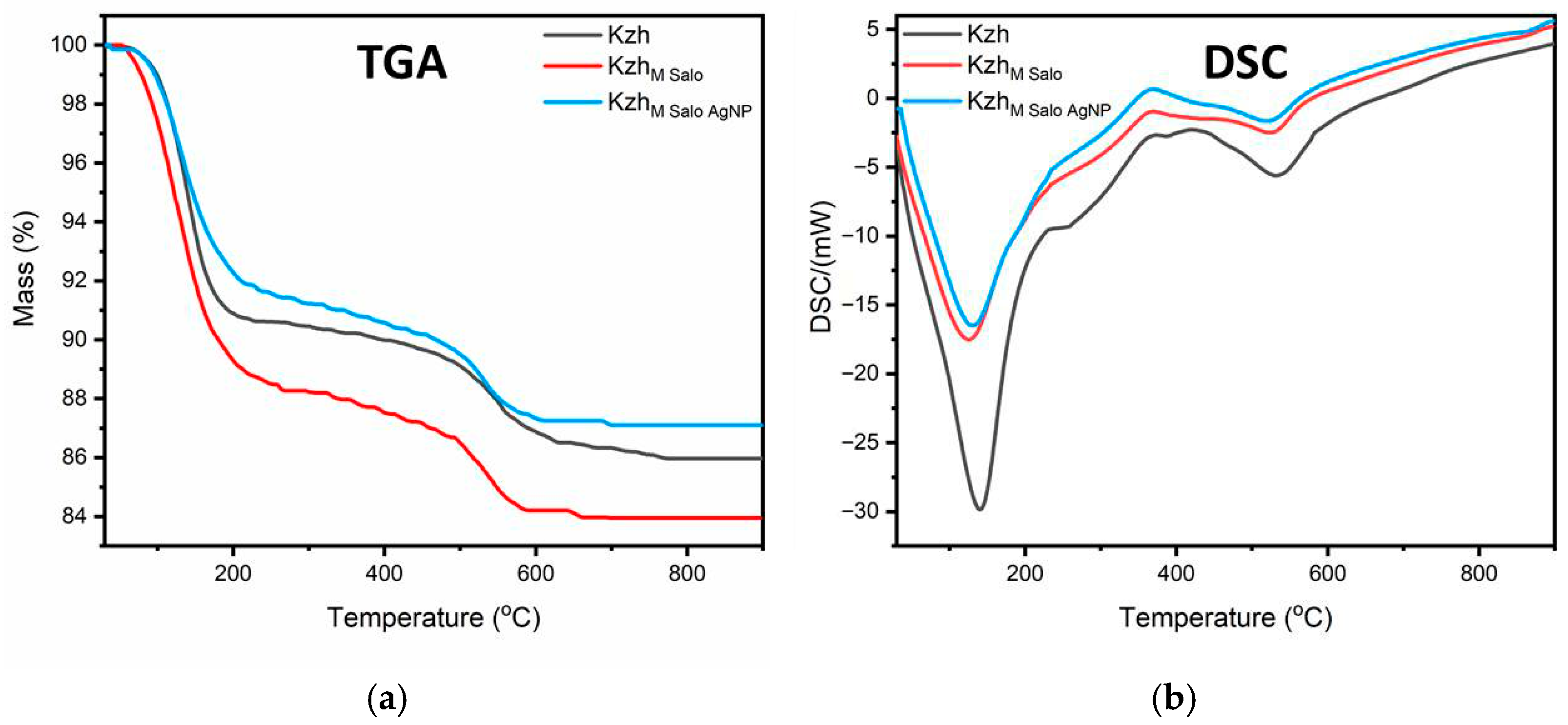

3.8. Thermal Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AgNPs | Silver Nanoparticles |

| KzhM Salo | D.P.Salo method Kzh bentonite |

| KzhM Salo AgNPs | Silver nanoparticles modified Kzh bentonite |

References

- Tabasi, H.; Oroojalian, F.; Darroudi, M. Green clay ceramics as potential nanovehicles for drug delivery applications. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 31042–31053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabdrakhmanova, S.K.; Kerimkulova, A.Z.; Nauryzova, S.Z.; Aryp, K.; Shaimardan, E.; Kukhareva, A.D.; Kantay, N.; Beisebekov, M.M.; Thomas, S. Bentonite-Based Composites in Medicine: Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, D.; Nath, H.; Saikia, H. Modification of bentonite clay & its applications: A review. Rev. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 42, 265–282. [Google Scholar]

- Pourhosseinhendabad, P.; Firouzabadi, P.Z. From raw to nano: Optimized purification and nano-bentonite synthesis for advanced applications. Phys. Scr. 2025, 100, 065916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babahoum, N.; Hamou, M.O. Characterization and purification of Algerian natural bentonite for pharmaceutical and cosmetic applications. BMC Chem. 2021, 15, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, A.; KhajeHassani, M.; Daneshafruz, H.; Hamedi, S.; Dorchei, F.; Kotlár, M.; Kazeminava, F.; Sadjadi, S.; Doostan, F.; Chodak, I.; et al. Thermoplastic starch/bentonite clay nanocomposite reinforced with vitamin B2: Physicochemical characteristics and release behavior. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 124742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngcobo, S.; Silwana, B.; Maqhashu, K.; Matoetoe, M.C. Bentonite nanoclay optoelectrochemical property improvement through bimetallic silver and gold nanoparticles. J. Nanotechnol. 2022, 2022, 3693938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; McCubbin, P. A comparison of the antimicrobial effects of four silver-containing dressings on three organisms. J. Wound Care 2003, 12, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asefian, S.; Ghavam, M. Green and environmentally friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles with antibacterial properties from some medicinal plants. BMC Biotechnol. 2024, 24, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasmi, F.; Hamitouche, H.; Laribi-Habchi, H.; Benguerba, Y.; Chafai, N. Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs), Methods of Synthesis, Characterization, and Their Application: A Review. Plasmonics 2025, 20, 9455–9488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohestani, H.; Nabilu, M.; Balooch, A. Biosynthesis and investigation of antibacterial properties of green silver nanoparticles using fruit extracts of Wild barberry, Medlar (Mespilus germanica L.), and Hawthorn. Food Chem. Adv. 2025, 6, 100850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavi, S.M.; Thokchom, B.; Singh, S.R.; Bajire, S.K.; Shastry, R.P.; Srinath, B.S.; Bhat, S.S.; Dupadahalli, K.; Govindasamy, C.; Chalekar, S.R.; et al. Syzygium malaccense leaf extract-mediated silver nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization, and biomedical evaluation in Caenorhabditis elegans and lung cancer cell line. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2025, 18, 2456624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.K.O.; Vieira, Í.R.S.; Souza, L.M.d.S.; Florêncio, I.; da Silva, I.G.M.; Junior, A.G.T.; Machado, Y.A.A.; dos Santos, L.C.; Taube, P.S.; Nakazato, G.; et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Paullinia cupana Kunth leaf extract collected in different seasons: Biological studies and catalytic properties. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sati, A.; Ranade, T.N.; Mali, S.N.; Yasin, H.K.A.; Pratap, A. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs): Comprehensive insights into bio/synthesis, key influencing factors, multifaceted applications, and toxicity—A 2024 update. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 7549–7582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyusebaeva, M.; Berillo, D.; Yesbussinova, Z.; Ibragimova, N.; Shepilov, D.; Sydykbayeva, S.; Almabekova, A.; Chinibayeva, N.; Adeloye, A.O.; Berganayeva, G. Green Synthesis and Characterization of Silver Nanoparticles Using Artemisia terrae-albae Extracts and Evaluation of Their Cytogenotoxic Effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridas, E.S.H.; Varma, M.K.R.; Chandra, G.K. Bioactive silver nanoparticles derived from Carica papaya floral extract and its dual-functioning biomedical application. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, S.S.; Alhaidal, H.; Mohammed, A.; Alsubait, A.; Alshammari, M.D.; Alsaqer, L.; Alzahrani, S.; Alanazi, F.; Al Tuhayni, L.B.; Ali, R.; et al. A Novel Integrated Approach: Plant-Mediated Synthesis, in vitro and in silico Evaluation of Silver Nanoparticles for Breast Cancer and Bacterial Therapies. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 10043–10071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beisebekov, M.M.; Zhumagalieva, S.N.; Beisebekov, M.K.; Abilov, Z.A.; Kosmella, S.; Koetz, J. Interactions of bentonite clay in composite gels of non-ionic polymers with cationic surfactants and heavy metal ions. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2015, 293, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Li, Z.; Zhao, G.; Guo, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S. Modified Bentonite as a Dissolve-Extrusion Composite and Its Modification Mechanism. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 33900–33911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannu, A.; Poddighe, M.; Mureddu, M.; Castia, S.; Mulas, G.; Murgia, F.; Di Pietro, M.E.; Mele, A.; Garroni, S. Impact of morphology of hydrophilic and hydrophobic bentonites on improving the pour point in the recycling of waste cooking oils. Appl. Clay Sci. 2024, 262, 107607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, H.Y.; Younus, M.M.; El Naga, A.O.A.; Saied, M.E.; Mahmoud, A.S. Biosynthesised bentonite clay-based Cu nanocomposite using Punica granatum L. peel extract for the effective catalytic reduction of hazardous aqueous contaminants. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Ahmed, W.; Moumene, T.; Belarbi, E.H.; Baeten, V.; Bresson, S. HTS/FTIR investigations in the spectral range 4000–600 cm−1 and BET method of specific surface area of various montmorillonite clays modified by monocationic and dicationic imidazolium ionic liquids. Chem. Phys. 2025, 598, 112844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrah, N.; Mu’azu, N.D.; Zubair, M.; Al-Harthi, M. Enhanced adsorptive performance of Cr (VI) onto layered double hydroxide-bentonite composite: Isotherm, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 1897–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, L.A.; Valenzuela, M.d.G.d.S.; Farooq, M.; Khattak, S.A.; Díaz, F.R.V. Influence of preparation methods on textural properties of purified bentonite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2018, 162, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkrim, S.; Mokhtar, A.; Djelad, A.; Bennabi, F.; Souna, A.; Bengueddach, A.; Sassi, M. Chitosan/Ag-bentonite nanocomposites: Preparation, characterization, swelling and biological properties. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2020, 30, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shameli, K.; Ahmad, M.B.; Yunus, W.M.Z.W.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Gharayebi, Y.; Sedaghat, S. Synthesis of silver/montmorillonite nanocomposites using γ-irradiation. Int. J. Nanomed. 2010, 5, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alraae, A.; Moussadik, A.; Benzaouak, A.; Kacimi, M.; Dahhou, M.; Sifou, A.; El Hamidi, A. One-step eco-friendly synthesis of Ag nanoparticles on bentonite-g-C3N4 for the reduction of hazardous organic pollutants in industrial wastewater. Next Nanotechnol. 2025, 7, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C.; Wu, C.; Chen, F.; Guo, Y.; Li, K.; Yao, M.; Zhu, Y. Microstructural Control and Macroscopic Performance Enhancement of Montmorillonite Crystals Based on Infrared Nanosecond Laser. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 37078–37086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belousov, P.E.; Pokidko, B.V.; Zakusin, S.V.; Krupskaya, V.V. Quantitative methods for quantification of montmorillonite content in bentonite clays. Georesursy 2020, 22, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkat, M.; Chegrouche, S.; Mellah, A.; Bensmain, B.; Nibou, D.; Boufatit, M. Application of algerian bentonite in the removal of cadmium (II) and chromium (VI) from aqueous solutions. J. Surf. Eng. Mater. Adv. Technol. 2014, 4, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keihanfar, M.; Mirjalili, B.B.F.; Bamoniri, A. Bentonite/Ti (IV) as a natural based nano-catalyst for synthesis of pyrimido[2, 1-b] benzothiazole under grinding condition. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarte, A.M.F.; Villarroel-Rocha, J.; Morantes, C.F.; Montes, M.L.; Sapag, K.; Curutchet, G.; Sánchez, R.M.T. Insight into surface and structural changes of montmorillonite and organomontmorillonites loaded with Ag. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2019, 22, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, H.; Fu, X.-L.; Reddy, K.R.; Wang, M.; Du, Y.-J. Interlayer and surface characteristics of carboxymethyl cellulose and tetramethylammonium modified bentonite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 428, 136303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, F.; Neree, A.T.; Megoura, M.; Mateescu, M.A.; Azzouz, A. Insights into the metal retention role in the antibacterial behavior of montmorillonite and cellulose tissue-supported copper and silver nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 24156–24171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhary, N.; Yadav, V.K.; Yadav, K.K.; Almohana, A.I.; Almojil, S.F.; Gnanamoorthy, G.; Kim, D.-H.; Islam, S.; Kumar, P.; Jeon, B.-H. Application of green synthesized MMT/Ag nanocomposite for removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution. Water 2021, 13, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composition % | Kzh | KzhM Salo | KzhM Salo AgNPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 67.6 | 70.5 | 70 |

| Al2O3 | 18.1 | 18.3 | 17.6 |

| Fe2O3 | 7.43 | 5.55 | 6.42 |

| MgO | 1.86 | 1.54 | 1.85 |

| CaO | 1.46 | 1.29 | 1.39 |

| TiO2 | 0.94 | 0.963 | 0.977 |

| K2O | 0.55 | 0.643 | 0.67 |

| SO3 | 1.65 | 0.742 | 0.429 |

| Ag | 0.0007 | 0.0005 | 0.349 |

| SrO | 0.063 | 0.052 | 0.0488 |

| MnO | 0.0435 | 0.0353 | 0.0324 |

| BaO | 0.0207 | 0.0136 | 0.0218 |

| V2O5 | 0.0321 | 0.0307 | 0.02 |

| HfO2 | 0.0128 | 0.0105 | 0.01 |

| P2O5 | 0.132 | 0 | 0.0118 |

| Co2O3 | 0.0212 | 0.0234 | 0.0143 |

| NiO | 0.0116 | 0.0106 | 0.0073 |

| Cr2O3 | 0.0088 | 0.016 | 0.0078 |

| CuO | 0.0085 | 0.0055 | 0.0107 |

| Cl | 0.0084 | 0.004 | 0.0091 |

| SnO2 | 0.008 | 0.0065 | 0.0051 |

| ZnO | 0.0061 | 0.0049 | 0.004 |

| Sample Name | BET Multi-Point Method Specific Surface (m2/g) | Pore Size Distribution (nm) | Pore Volume | Pore Surface Area | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cm3/g | % | cm3/g | % | ||||

| Kzh | 68.6044 | micro | 0.35–2 | 0.0206 | 41.20 | 46.6471 | 58.73 |

| meso | 2–10 | 0.0226 | 45.39 | 31.3062 | 39.42 | ||

| 10–50 | 0.0067 | 13.41 | 1.4671 | 1.85 | |||

| macro | 50–200 | 0.0000 | 0.00 | 0.0000 | 0.00 | ||

| KzhM Salo | 80.5450 | micro | 0.35–2 | 0.0230 | 40.62 | 52.8010 | 58.11 |

| meso | 2–10 | 0.0272 | 48.01 | 36.5133 | 40.19 | ||

| 10–5 | 0.0064 | 11.38 | 1.5459 | 1.70 | |||

| macro | 50–200 | 0.0000 | 0.00 | 0.0000 | 0.00 | ||

| KzhM Salo AgNPs | 94.4786 | micro | 0.35–2 | 0.0243 | 20.87 | 54.7005 | 49.69 |

| meso | 2–10 | 0.0367 | 31.56 | 46.7137 | 42.43 | ||

| 10–50 | 0.0369 | 31.75 | 7.4802 | 6.79 | |||

| macro | 50–200 | 0.0184 | 15.82 | 1.1906 | 1.08 | ||

| Sample Name | Constant, ah. | 0.063257 | Constant b | 0.0001648 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kzh | Correlation R2 | 0.99999 | Constant C according to BET | 384.7 |

| Range P/P0 | 0.0150~ 0.1293 | Monolayer capacity, Vm | 15.7674 cm3/g | |

| Surface area BET | 68.6044 m2/g | |||

| KzhM Salo AgNPs | Constant, ah. | 0.045903 | Constant b | 0.0001498 |

| Correlation R2 | 0.99999 | Constant C | 307.5 | |

| according to BET | ||||

| Range P/P0 | 0.0215~ | Monolayer capacity, | 21.7141 cm3/g | |

| 0.1232 | Vm | |||

| Surface area BET | 94.4786 m2/g | |||

| Sample Name | Results of the Langmuir Multipoint Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kzh | Constant, a | 0.046214 | Constant b | 0.1303158 |

| Correlation R2 | 0.99928 | Constant C | 0.4 | |

| P/P0 value | 4~32 bar | Monolayer capacity Vm | 21.6384 cm3/g | |

| Langmuir surface area | 94.1493 m2/g | |||

| KzhM Salo AgNPs | Constant, a | 0.0432522 | Constant b | 0.0922802 |

| Correlation R2 | 0.99871 | Constant C | 0.4 | |

| P/P0 value | 4~32 bar | Monolayer capacity Vm | 30.7480 cm3/g | |

| Langmuir surface area | 133.7854 m2/g | |||

| Determination Method | Specific Surface Area, m2/g | |

|---|---|---|

| Kzh | KzhM Salo AgNPs | |

| Multipoint BET | 68.6044 | 94.4786 |

| Single-point BET | 67.3075 | 92.3351 |

| Langmuir method | 94.1493 | 133.7854 |

| BJH desorption method (1.7–195.6 nm), intrapore region | 33.5658 | 81.9256 |

| BJH adsorption method (1.7–195.6 nm), intra-pore surface area | 32.7734 | 55.3844 |

| DR method, specific surface area of micropores | 81.8031 | 109.2392 |

| T-Plot method, specific surface area of micropores | 46.6471 | 54.7005 |

| T-Plot method, external specific surface area | 21.9573 | 39.7782 |

| Sample Name | Microporisation Results (Adsorption-Based) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kzh | Constant, ah. | 14.19526 | Constant, b | 13.29235 |

| Correlation, R2 | 0.99678 | Range, P/P0 | 0.0000~0.8000 | |

| Micropore volume | 0.0206 cm3/g | |||

| Specific surface area of micropores | 46.6471 m2/g | |||

| External specific surface area | 21.9573 m2/g | |||

| KzhM Salo AgNPs | Constant, ah. | 2,863,026 | Constant, b | 18.11149 |

| Correlation, R2 | 0.99921 | Range, P/P0 | 0.3470~0.5975 | |

| Micropore volume | 0.0280 cm3/g | |||

| Specific surface area of micropores | 63.9451 m2/g | |||

| External specific surface area | 44.2854 m2/g | |||

| Sample Name | Microporous DR Method (Adsorption-Based) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kzh | Constant, ah. | −0.0406 | Constant, b | −1.6292 |

| Correlation, R2 | 0.99993 | Range, P/P0 | 0.0023~0.0150 | |

| DR medium aperture | 1.708 nm | |||

| DR micropore volume | 0.0291 cm3/g | |||

| DR specific microporous surface area | 81.8031 m2/g | |||

| KzhM Salo AgNPs | Constant, ah. | −0.0353 | Constant, b | −1.4448 |

| Correlation, R2 | 0.99928 | Range, P/P0 | 0.0011~0.0278 | |

| DR medium aperture | 1.593 nm | |||

| DR micropore volume | 0.0444 cm3/g | |||

| DR specific microporous surface area | 125.0755 m2/g | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nauryzova, S.Z.; Kabdrakhmanova, S.K.; Kabdrakhmanova, A.K.; Aryp, K.; Shaimardan, E.; Kukhareva, A.D.; Ibraeva, Z.E.; Beisebekov, M.M.; Kamil, A.M.; Thomas, M.G.; et al. Comprehensive Study of Silver Nanoparticle Functionalization of Kalzhat Bentonite for Medical Application. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 702. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120702

Nauryzova SZ, Kabdrakhmanova SK, Kabdrakhmanova AK, Aryp K, Shaimardan E, Kukhareva AD, Ibraeva ZE, Beisebekov MM, Kamil AM, Thomas MG, et al. Comprehensive Study of Silver Nanoparticle Functionalization of Kalzhat Bentonite for Medical Application. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):702. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120702

Chicago/Turabian StyleNauryzova, Saule Z., Sana K. Kabdrakhmanova, Ainur K. Kabdrakhmanova, Kadiran Aryp, Esbol Shaimardan, Anastassiya D. Kukhareva, Zhanar E. Ibraeva, Madiar M. Beisebekov, Ahmed M. Kamil, Martin George Thomas, and et al. 2025. "Comprehensive Study of Silver Nanoparticle Functionalization of Kalzhat Bentonite for Medical Application" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 702. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120702

APA StyleNauryzova, S. Z., Kabdrakhmanova, S. K., Kabdrakhmanova, A. K., Aryp, K., Shaimardan, E., Kukhareva, A. D., Ibraeva, Z. E., Beisebekov, M. M., Kamil, A. M., Thomas, M. G., & Thomas, S. (2025). Comprehensive Study of Silver Nanoparticle Functionalization of Kalzhat Bentonite for Medical Application. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 702. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120702