Influence of FeSiB Layer Thickness on Magnetoelectric Response of Asymmetric and Symmetric Structures of Magnetostrictive/Piezoelectric Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

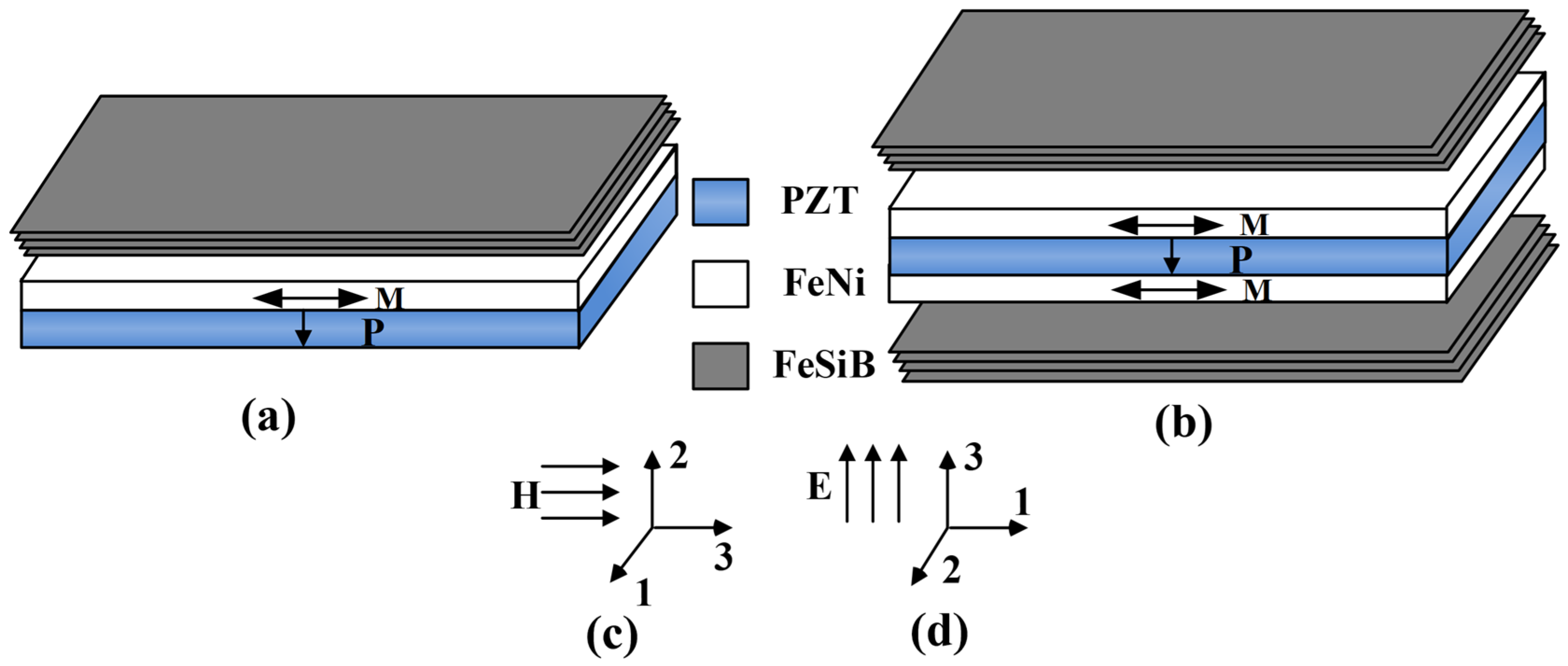

2.2. Composite Structure

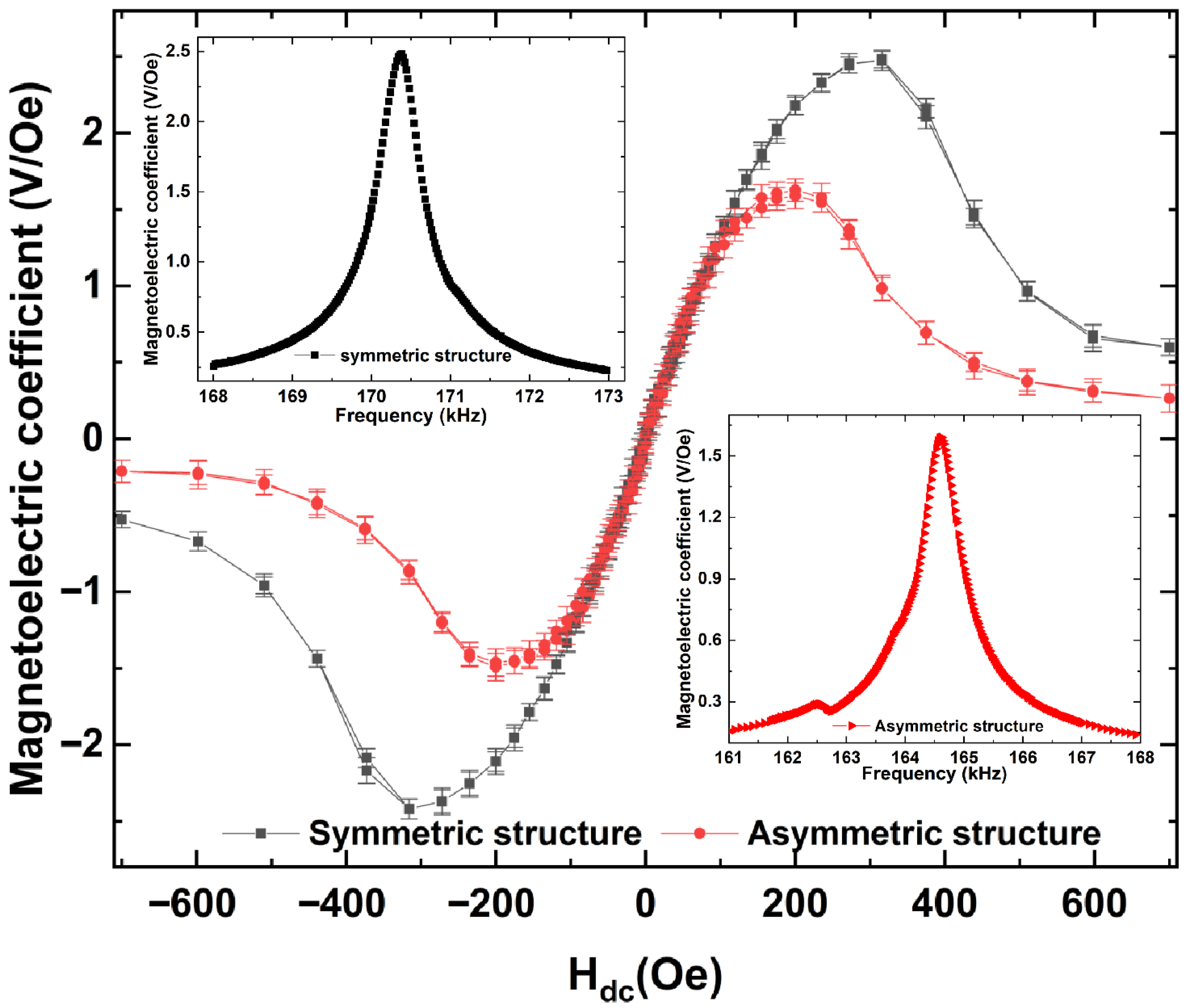

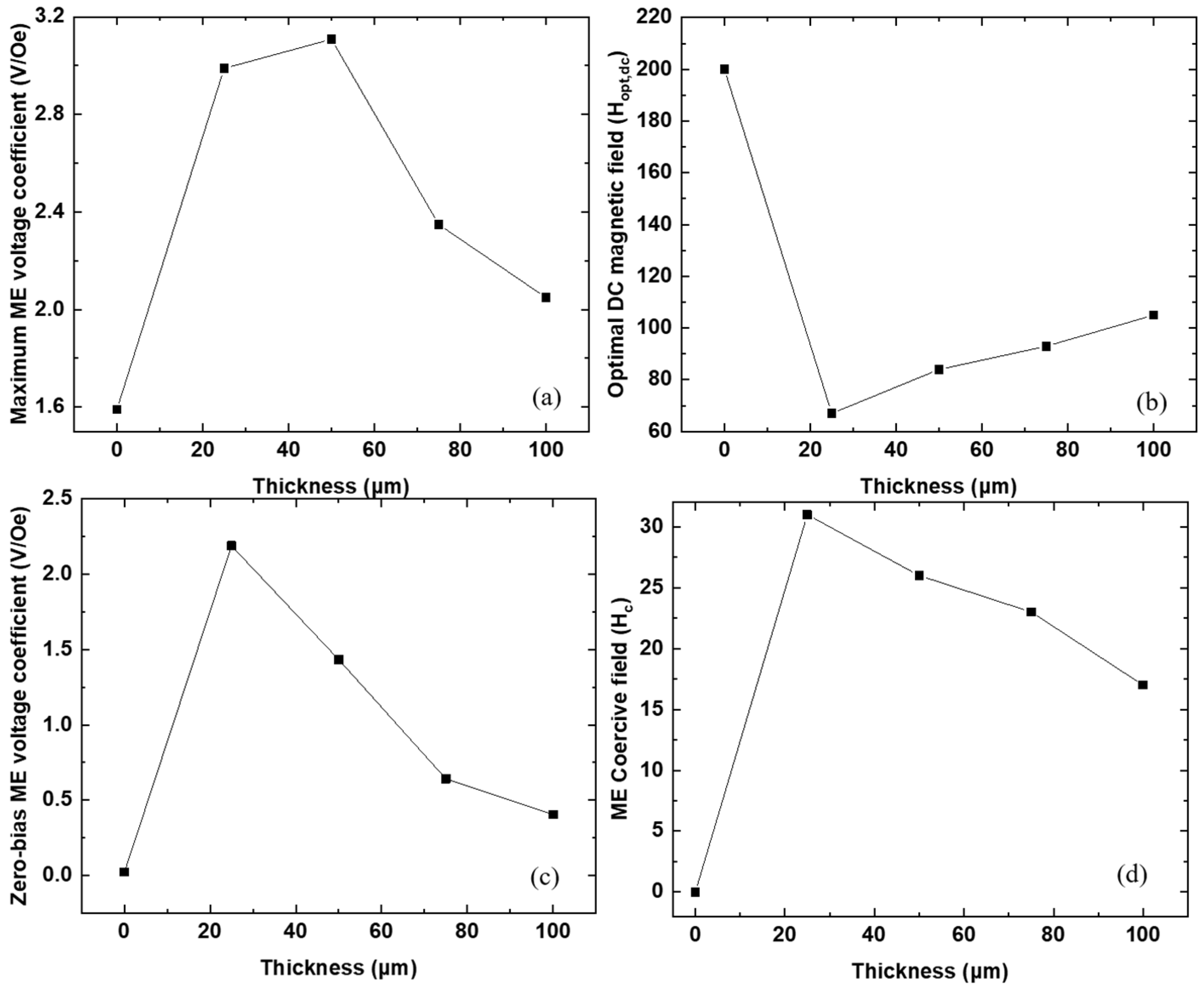

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ryu, J.; Carazo, A.V.; Uchino, K.; Kim, H.E. Magnetoelectric properties in piezoelectric and magnetostrictive laminate composites. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2001, 40, 4948–4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Matyushov, A.; Dong, C.; Chen, H.; Lin, H.; Nan, T.; Qian, Z.; Rinaldi, M.; Lin, Y.; Sun, N.X. Ultra-sensitive NEMS magnetoelectric sensor for picotesla DC magnetic field detection. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 143510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaldin, N.A.; Ramesh, R. Advances in magnetoelectric multiferroics. Nat. Mater. 2019, 18, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, C.; Chu, Z.-Q.; Spetzler, B.; Hayes, P.; Dong, C.-Z.; Liang, X.-F.; Chen, H.-H.; He, Y.-F.; Wei, Y.-Y.; Lisenkov, I.; et al. Mechanical-Resonance-Enhanced Thin-Film Magnetoelectric Heterostructures for Magnetometers, Mechanical Antennas, Tunable RF Inductors, and Filters. Materials 2019, 12, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, C.W.; Bichurin, M.I.; Dong, S.; Viehland, D.; Srinivasan, G. Multiferroic magnetoelectric composites: Historical perspective, status, and future directions. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 103, 031101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.; Pourhosseiniasl, M.J.; Dong, S. Review of multi-layered magnetoelectric composite materials and devices applications. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2018, 51, 243001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Chen, H.; Sun, N.X. Magnetoelectric materials and devices. APL Mater. 2021, 9, 41114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, N.; Xiao, R.; Wen, Y.; Li, P.; Chen, L.; Ji, X.; Han, T. Enhanced dc Magnetic Field Sensitivity for Coupled ac Magnetic Field and Stress Driven Soft Magnetic Laminate Heterostructure. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 14756–14763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.; Shi, H.; Pourhosseiniasl, M.J.; Wu, J.; Shi, W.; Gao, X.; Yuan, X.; Dong, S. A magnetoelectric flux gate: New approach for weak DC magnetic field detection. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.W.; Wang, B.; Wang, K.F.; Wan, J.G.; Liu, J.M. Ultra-sensitive detection of magnetic field and its direction using bilayer PVDF/Metglas laminate. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2009, 153, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Wang, X.; Lin, H.; Gao, Y.; Zaeimbashi, M. A portable very low frequency (VLF) communication system based on acoustically actuated magnetoelectric antennas. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2020, 19, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jing, L.; Shi, P.; Hou, J.; Yang, X.; Peng, Y.; Chen, S. Research on a miniaturized VLF antenna array based on a magnetoelectric heterojunction. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2022, 33, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Mallick, D. A self-biased, low-frequency, miniaturized magnetoelectric antenna for implantable medical device applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2023, 122, 014102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastouri, H.; Ennawaoui, A.; Remaidi, M.; Sabani, E.; Derraz, M.; El Hadraoui, H.; Ennawaoui, C. Design, Modeling, and Experimental Validation of a Hybrid Piezoelectric–Magnetoelectric Energy-Harvesting System for Vehicle Suspensions. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.M.; Li, J.; Viehland, D.; Zhuang, X. A review on applications of magnetoelectric composites: From heterostructural uncooled magnetic sensors, energy harvesters to highly efficient power converters. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2018, 51, 263002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozielski, L.; Bochenek, D.; Clemens, F.; Sebastian, T. Magnetoelectric Composites: Engineering for Tunable Filters and Energy Harvesting Applications. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, A.; Li, P.; Zhang, S. Magnetoelectric Memory Based on Ferromagnetic/Ferroelectric Multiferroic Heterostructure. Materials 2021, 14, 4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wu, J.; Liu, S.; Gao, J.; Lin, B.; Mo, J.; Qiao, J.; Xu, Y.; Du, Y.; He, X.; et al. Magnetoelectric Sensor Operating in d15 Thickness-Shear Mode for High-Frequency Current Detection. Sensors 2024, 24, 2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.M.; Zhuang, X.; Friedrichs, D.; Li, J.; Erickson, R.W.; Laletin, V.; Popov, M.; Srinivasan, G.; Viehland, D. Highly efficient solid state magnetoelectric gyrators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 111, 122904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saveliev, D.; Chashin, D.; Fetisov, L.; Shamonin, M.; Fetisov, Y. Ceramic-heterostructure based magnetoelectric voltage transformer with an adjustable transformation ratio. Materials 2020, 13, 3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bichurin, M.; Sokolov, O.; Ivanov, S.; Ivasheva, E.; Leontiev, V.; Lobekin, V.; Semenov, G. Modeling the Composites for Magnetoelectric Microwave Devices. Sensors 2023, 23, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.M.; Cardoso, V.F.; Martins, P.; Correia, D.M.; Gonçalves, R.; Costa, P.; Correia, V.; Ribeiro, C.; Fernandes, M.M.; Martins, P.M.; et al. Smart and multifunctional materials based on electroactive poly (vinylidene fluoride): Recent advances and opportunities in sensors, actuators, energy, environmental, and biomedical applications. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 11392–11487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, D.A.; Zhang, S.G.; Volinsky, A.A.; Qiao, L.J. Shape and size effects on layered Ni/PZT/Ni composites magnetoelectric performance. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2008, 41, 172003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Y. The effects of the soft magnetic alloys’ material characteristics on resonant magnetoelectric coupling for magnetostrictive/piezoelectric composites. Smart Mater. Struct. 2019, 28, 045003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Gray, D.; Berry, D.; Li, M.H.; Gao, J.Q.; Li, J.F.; Viehland, D. Influence of interfacial bonding condition on magnetoelectric properties in piezofiber/Metglas heterostructures. J. Alloys Compd. 2012, 513, 242–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.X.; Li, J.F.; Viehland, D. Longitudinal and transverse magnetoelectric voltage coefficients of magnetostrictive/piezoelectric laminate composite: Theory. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. 2003, 50, 1253–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyau, V.; Morin, V.; Chaplier, G.; Lobue, M.; Mazaleyrat, F. Magnetoelectric effect in layered ferrite/PZT composites. Study of the demagnetizing effect on the magnetoelectric behaviour. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 117, 184102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivasheva, E.E.; Leontiev, V.S.; Bichurin, M.I.; Koledov, V.V. Application of Heat Treatment to Optimize the Magnetostrictive Component of a Magnetoelectric Composite. J. Commun. Technol. Electron. 2022, 68, 451–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.P.; Martins, P.; Lasheras, A.; Gutiérrez, J.; Barandiarán, J.M.; Lanceros-Mendez, S. Size effects on the magnetoelectric response on PVDF/Vitrovac 4040 laminate composites. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2015, 377, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liao, S.; Zou, H.; Qin, B.; Deng, L. Transition-Layer Implantation for Improving Magnetoelectric Response in Co-fired Laminated Composite. Magnetochemistry 2023, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saengow, T.; Silapunt, R. Geometry–Dependent Magnetoelectric and Exchange Bias Effects of the Nano L–T Mode Bar Structure Magnetoelectric Sensor. Micromachines 2023, 14, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, S.; Jiang, N.; Zhuang, X.; Yan, B.; Zhang, F.; Dolabdjian, C.; Fang, G. Resonant Magnetoelectric Coupling of Fe-Si-B/Pb(Zr,Ti)O3 Laminated Composites with Surface Crystalline Layers. Sensors 2023, 23, 9622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Li, P.; Wen, Y.M.; Zhu, Y. Note: High sensitivity self-bias magnetoelectric sensor with two different magnetostrictive materials. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2013, 84, 066101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Li, P.; Wen, Y.M.; Zhu, Y. Large self-biased effect and dual-peak magnetoelectric effect in different three-phase magnetostrictive/piezoelectric composites. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 606, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Y. Dynamic Magneto-mechanical Behavior of Magnetization-graded Ferromagnetic Materials. J. Magn. 2014, 19, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Zhai, J.Y. Equivalent circuit method for static and dynamic analysis of magnetoelectric laminated composites. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2008, 53, 2113–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Dong, S. A Resonance-Bending Mode Magnetoelectric Coupling Equivalent Circuit. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Contr. 2009, 56, 2578–2586. [Google Scholar]

- Bichurin, M.; Sokolov, O.; Ivanov, S.; Ivasheva, E.; Leontiev, V.; Lobekin, V.; Semenov, G. Modeling the Magnetoelectric Composites in a Wide Frequency Range. Materials 2023, 16, 5813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdin, D.A.; Chashin, D.V.; Ekonomov, N.A.; Fetisov, L.Y.; Preobrazhensky, V.L.; Fetisov, Y.K. Low-Frequency Resonant Magnetoelectric Effects in Layered Heterostructures Antiferromagnet-Piezoelectric. Sensors 2023, 23, 5901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wen, Y.M.; Li, P.; Zheng, M.; Bian, L.X. Resonant magnetoelectric response of magnetostrictive/piezoelectric laminate composite in consideration of losses. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2008, 141, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudakar, C.; Naik, R.; Lawes, G.; Mantese, J.V.; Micheli, A.L.; Srinivasan, G.; Alpay, S.P. Internal magnetostatic potentials of magnetization-graded ferromagnetic materials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 062502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.C.; Park, C.S.; Cho, K.H.; Priya, S. Self-biased magnetoelectric response in three-phase laminates. J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 108, 093706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | or (×10−12 m2/N) | ρp, ρm, ρf (kg/m3) | λs (ppm) | μr | Qm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PZT8 a | 11.1 | 7700 | 1000 | ||

| FeNi alloy b | 40 | 8000 | 11 | 30 | 9000 |

| FeSiB c | 9.09 | 7250 | 27 | 40,000 | 1000 |

| Mix Ratio | Cure Time | Viscosity | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5:1 | 24 h full cure, 7 d max strength at 25 °C | Low-viscosity liquid, cures to high-strength solid | Structural bonding, fiberglass reinforcement |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, L.; Cheng, Y.; Qin, F. Influence of FeSiB Layer Thickness on Magnetoelectric Response of Asymmetric and Symmetric Structures of Magnetostrictive/Piezoelectric Composites. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 693. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120693

Chen L, Cheng Y, Qin F. Influence of FeSiB Layer Thickness on Magnetoelectric Response of Asymmetric and Symmetric Structures of Magnetostrictive/Piezoelectric Composites. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):693. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120693

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Lei, Yingjie Cheng, and Fujian Qin. 2025. "Influence of FeSiB Layer Thickness on Magnetoelectric Response of Asymmetric and Symmetric Structures of Magnetostrictive/Piezoelectric Composites" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 693. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120693

APA StyleChen, L., Cheng, Y., & Qin, F. (2025). Influence of FeSiB Layer Thickness on Magnetoelectric Response of Asymmetric and Symmetric Structures of Magnetostrictive/Piezoelectric Composites. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 693. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120693