Experimental and Analytical Evaluation of GFRP-Reinforced Concrete Bridge Barriers at the Deck–Wall Interface

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Program

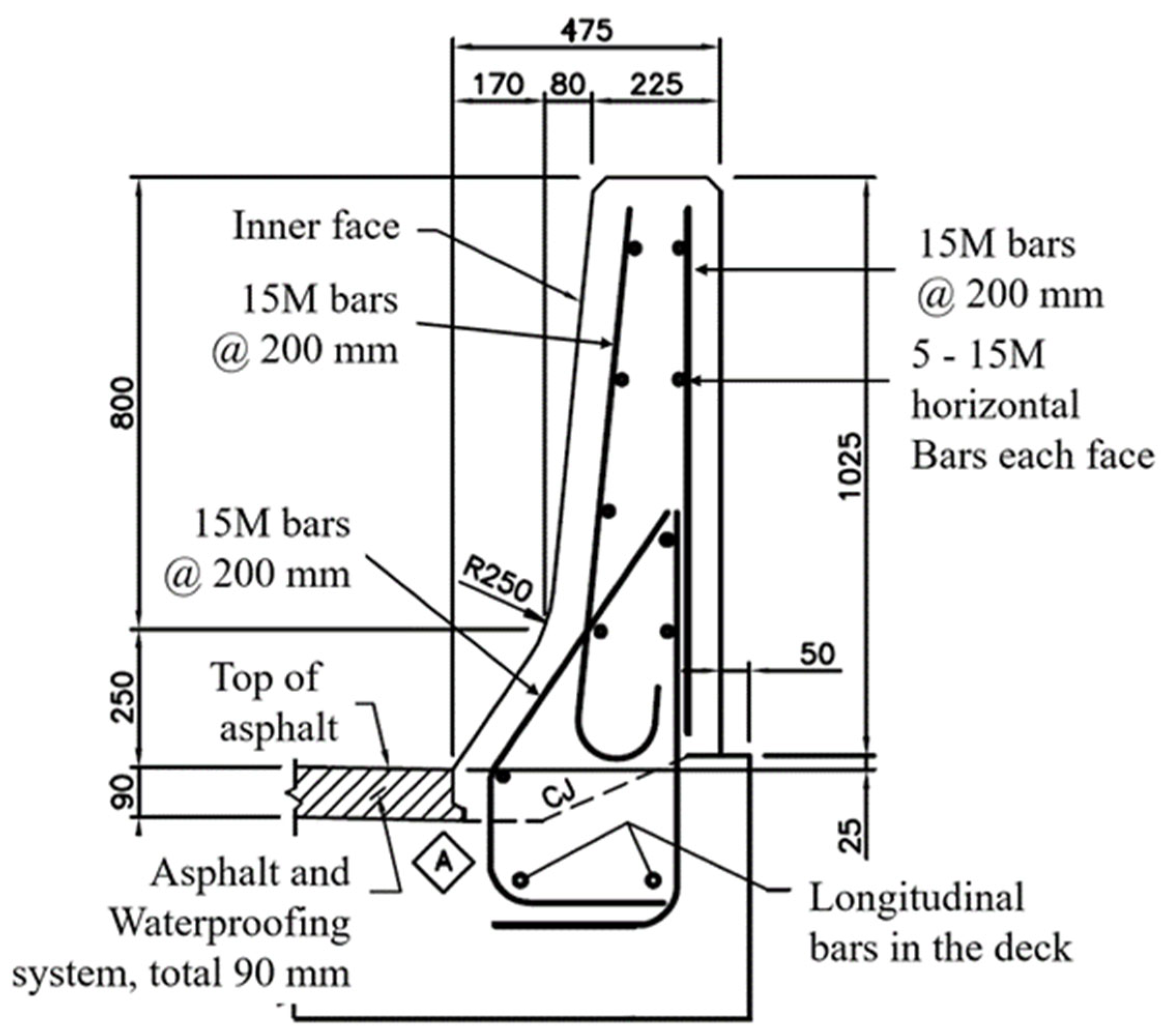

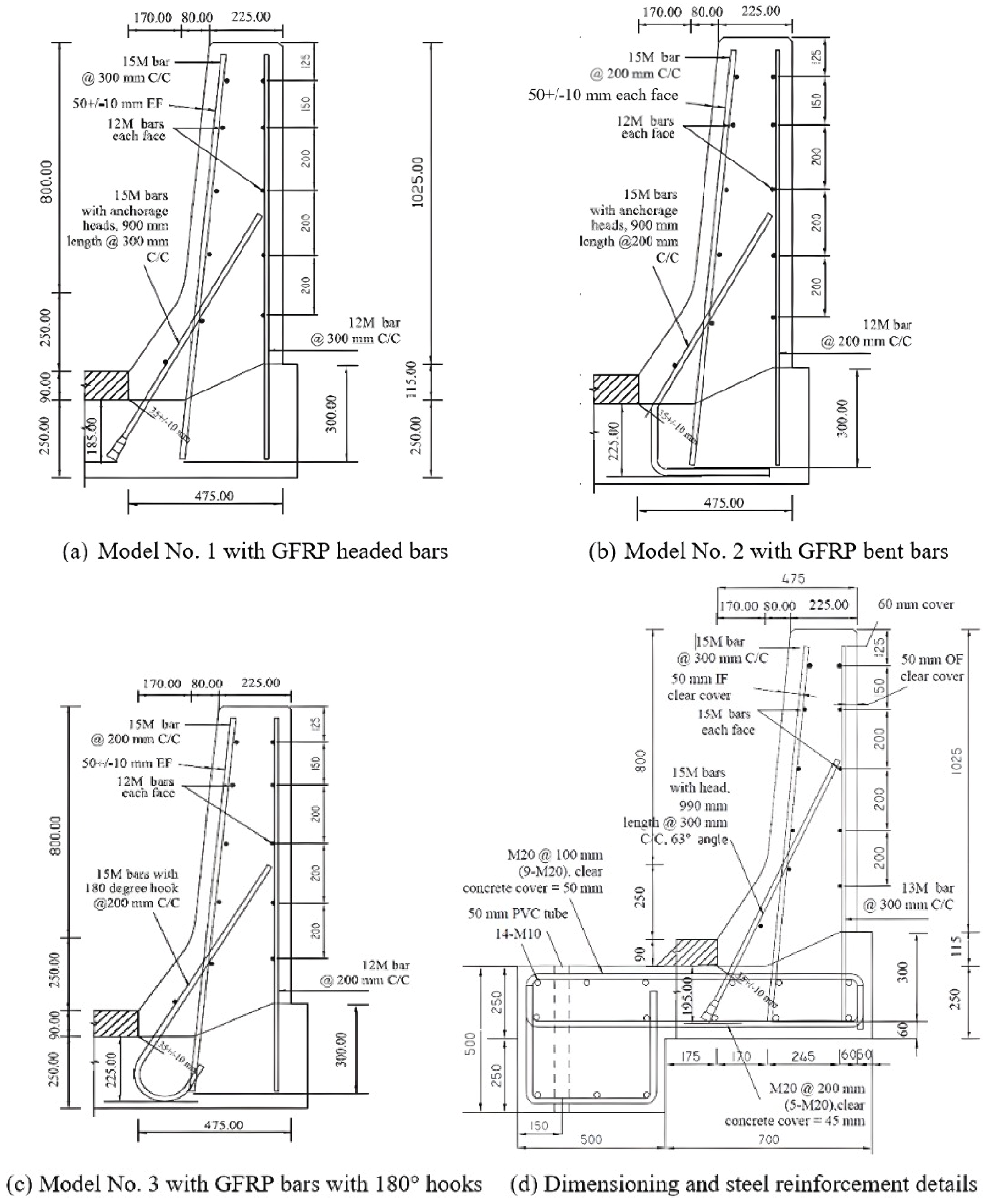

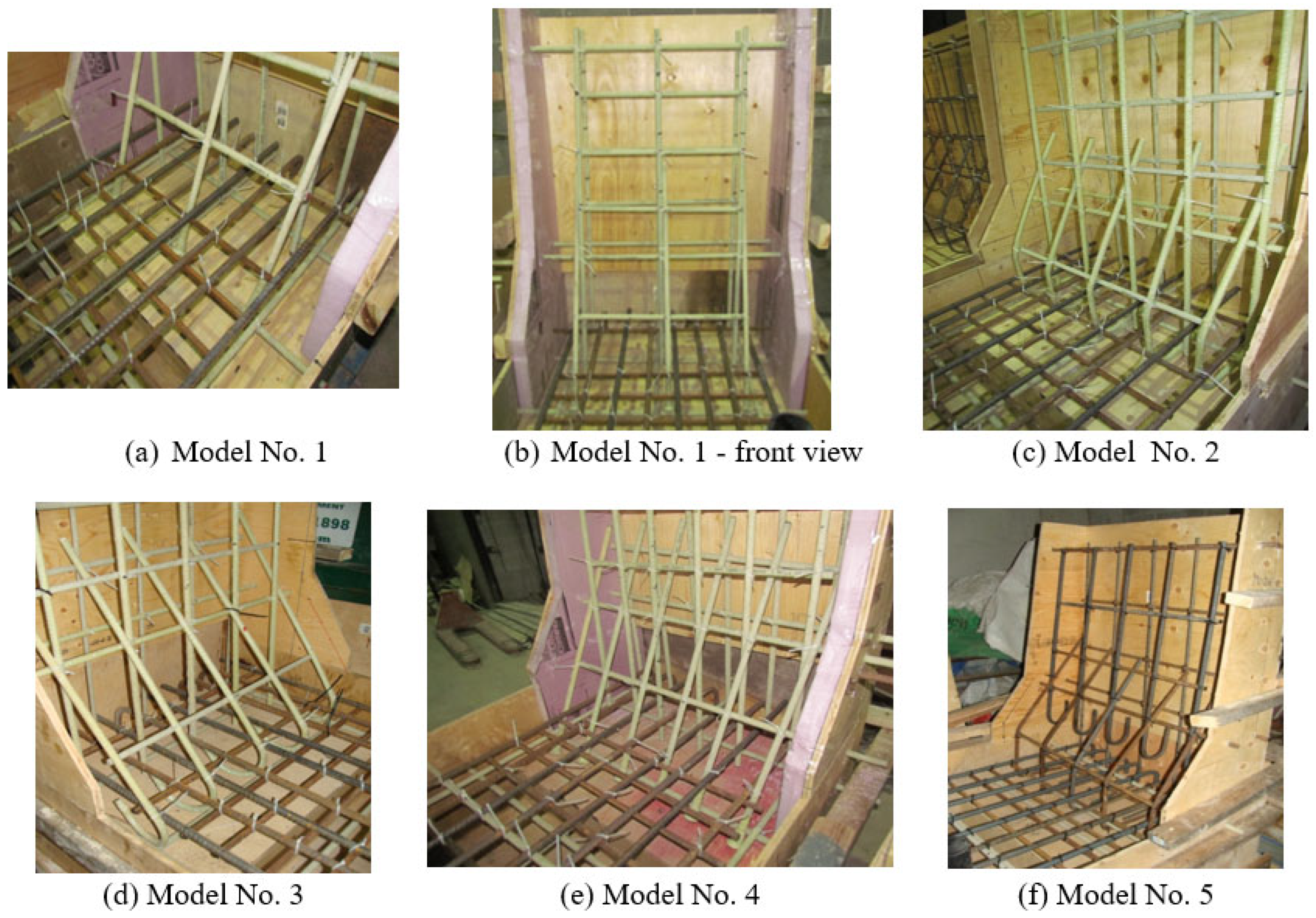

2.1. Test Specimens

2.2. Material Properties

2.3. Test Setup and Instrumentation

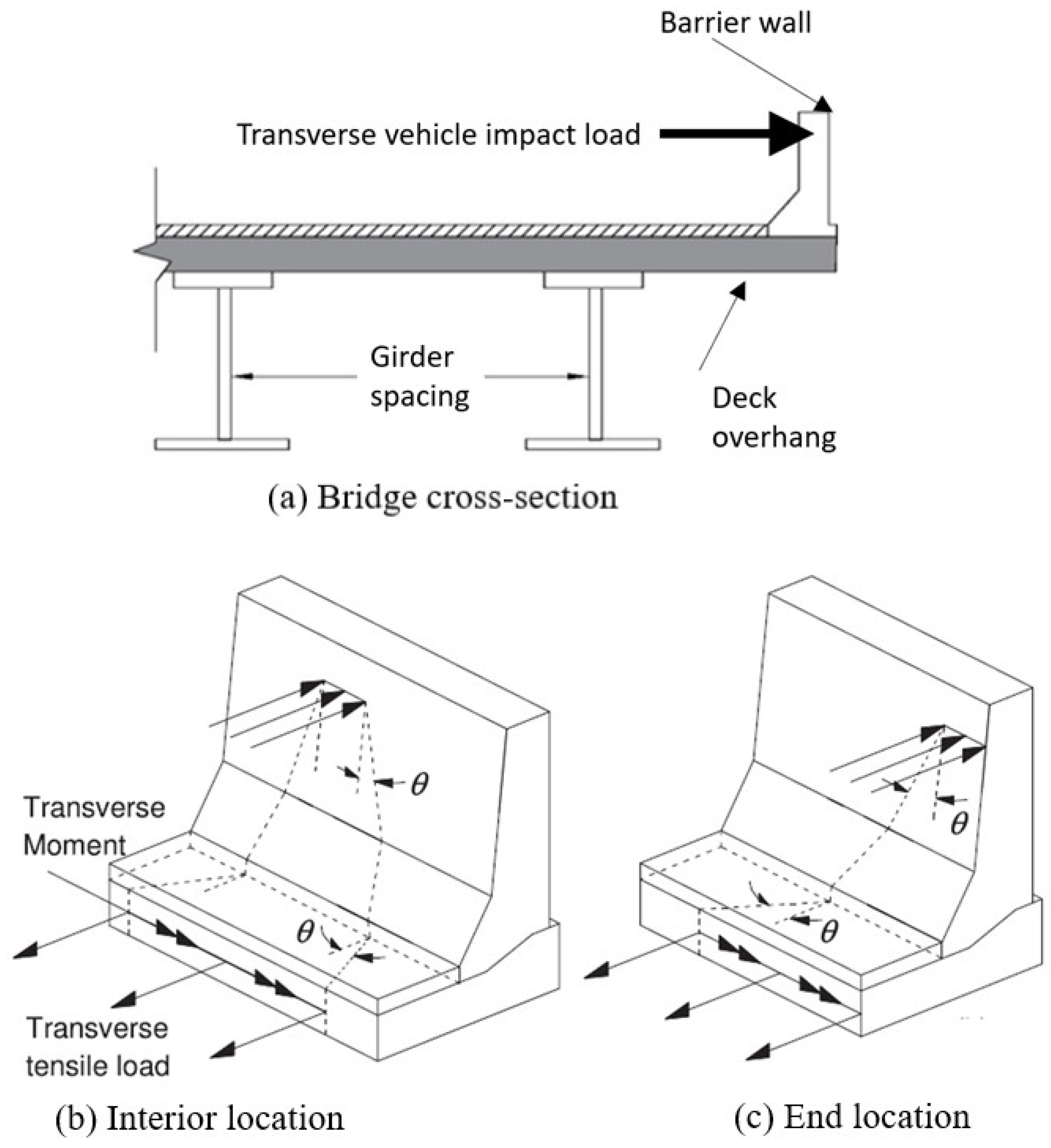

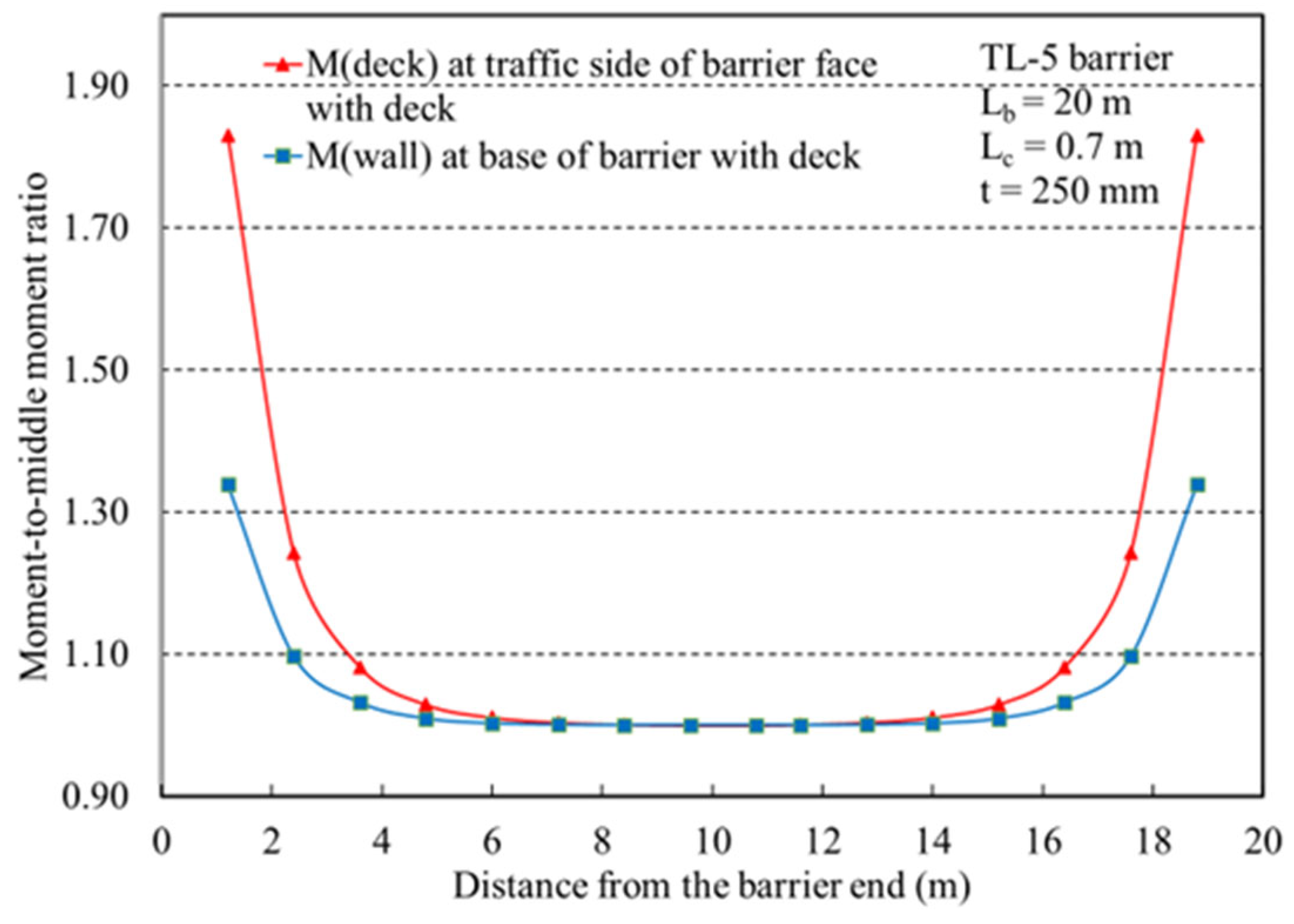

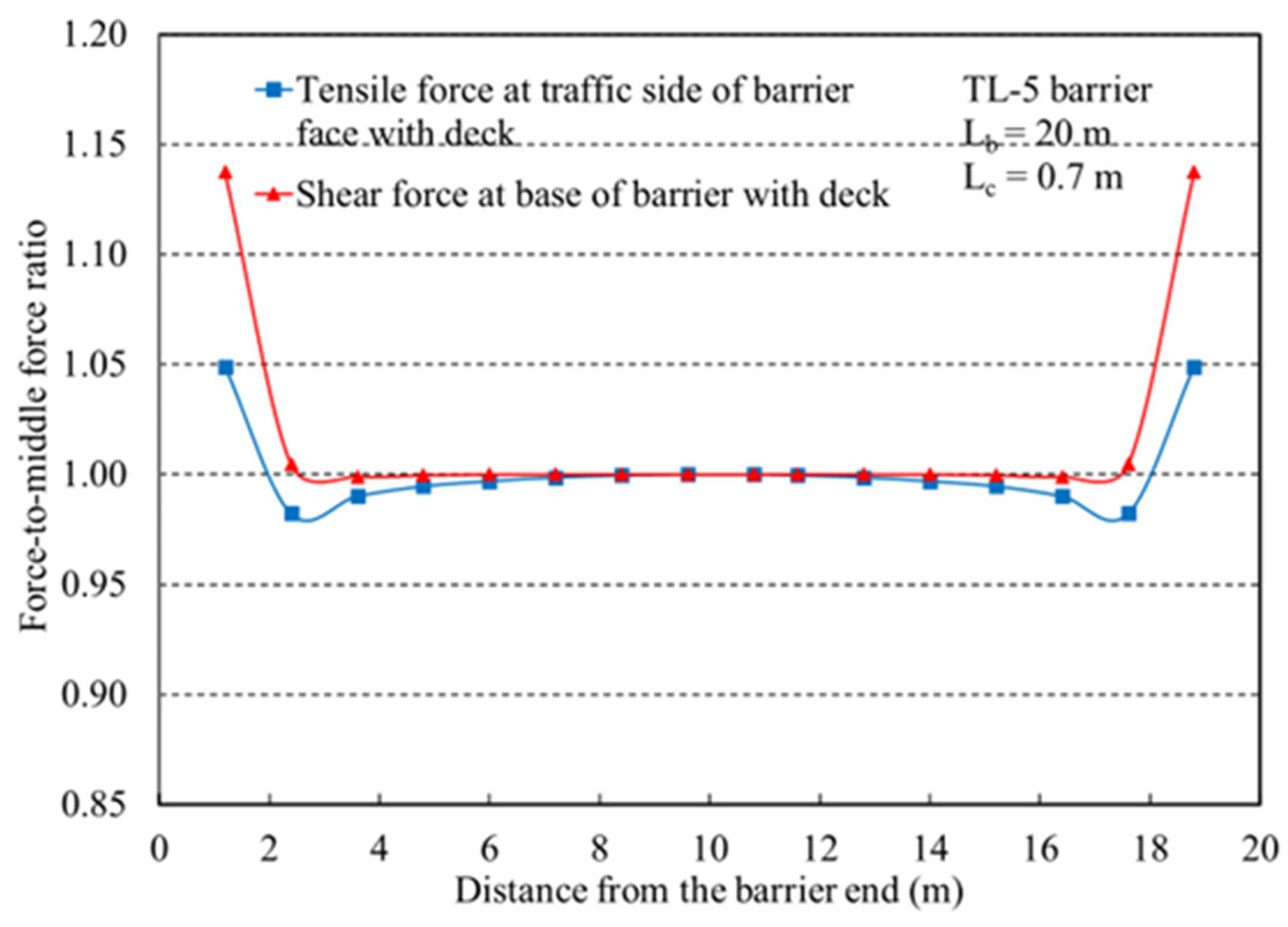

3. Structural Demand of the TL-5 Barrier–Deck Overhang System

4. Test Results and Discussion

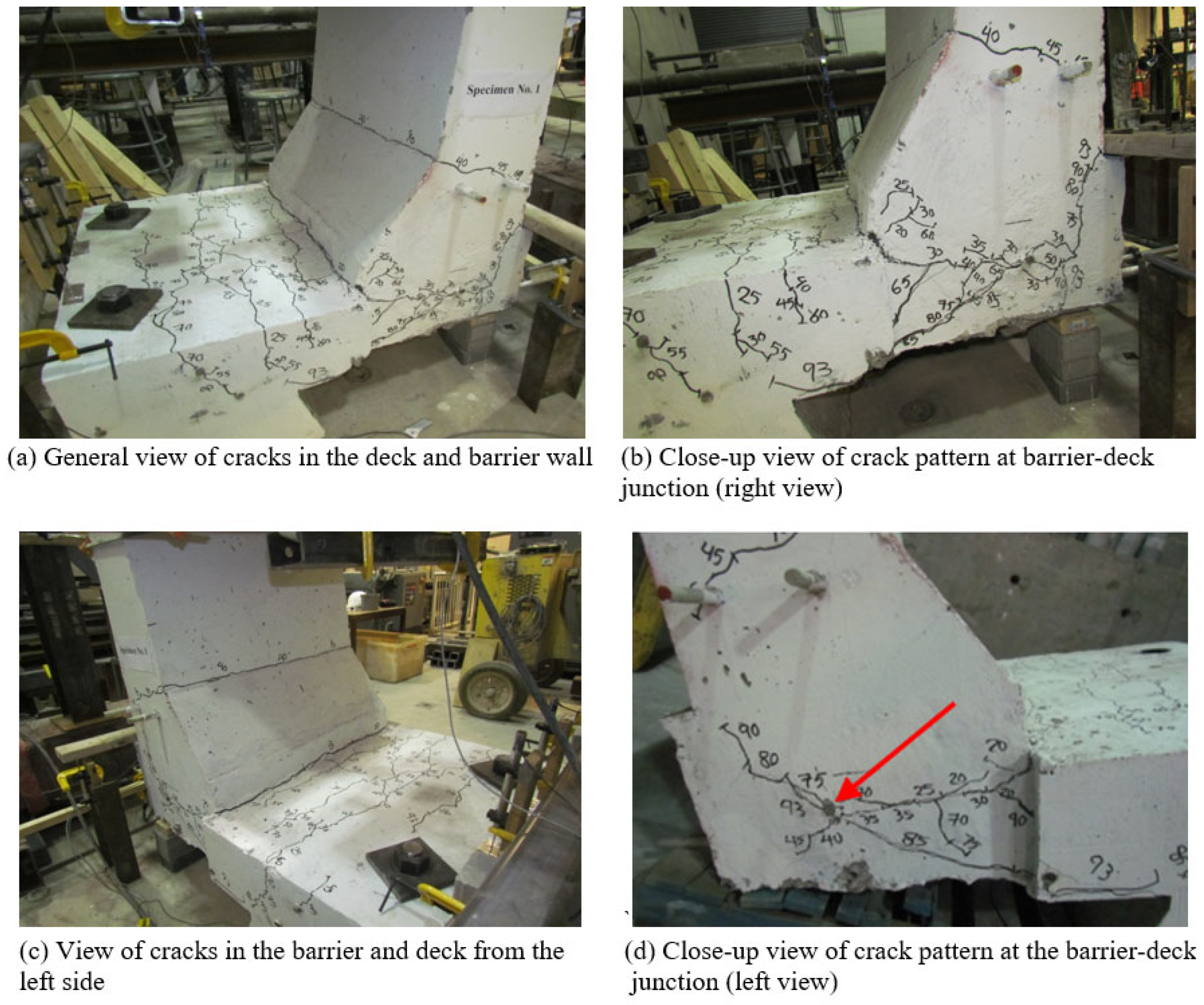

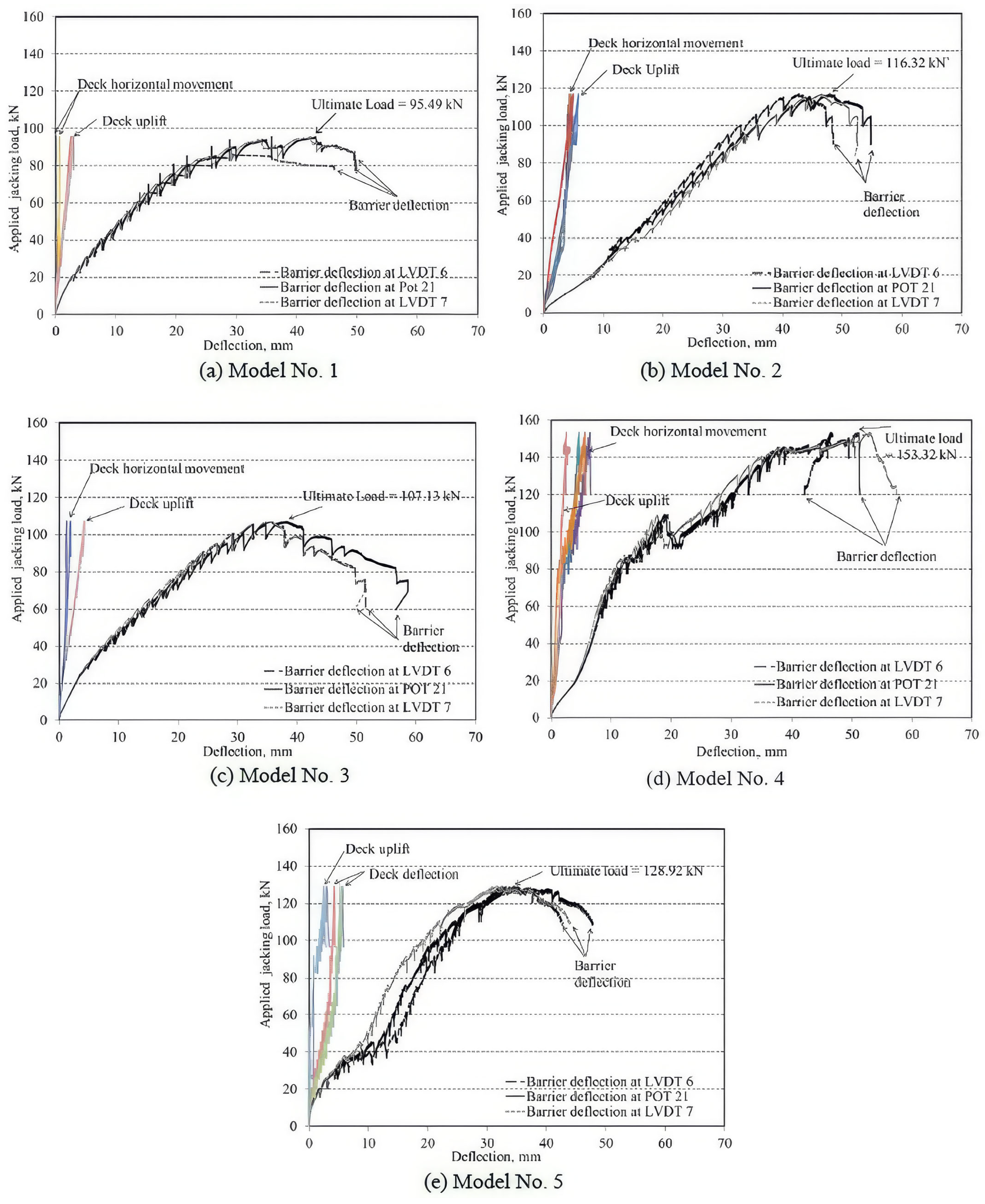

4.1. Crack Patterns and Load-Carrying Capacity

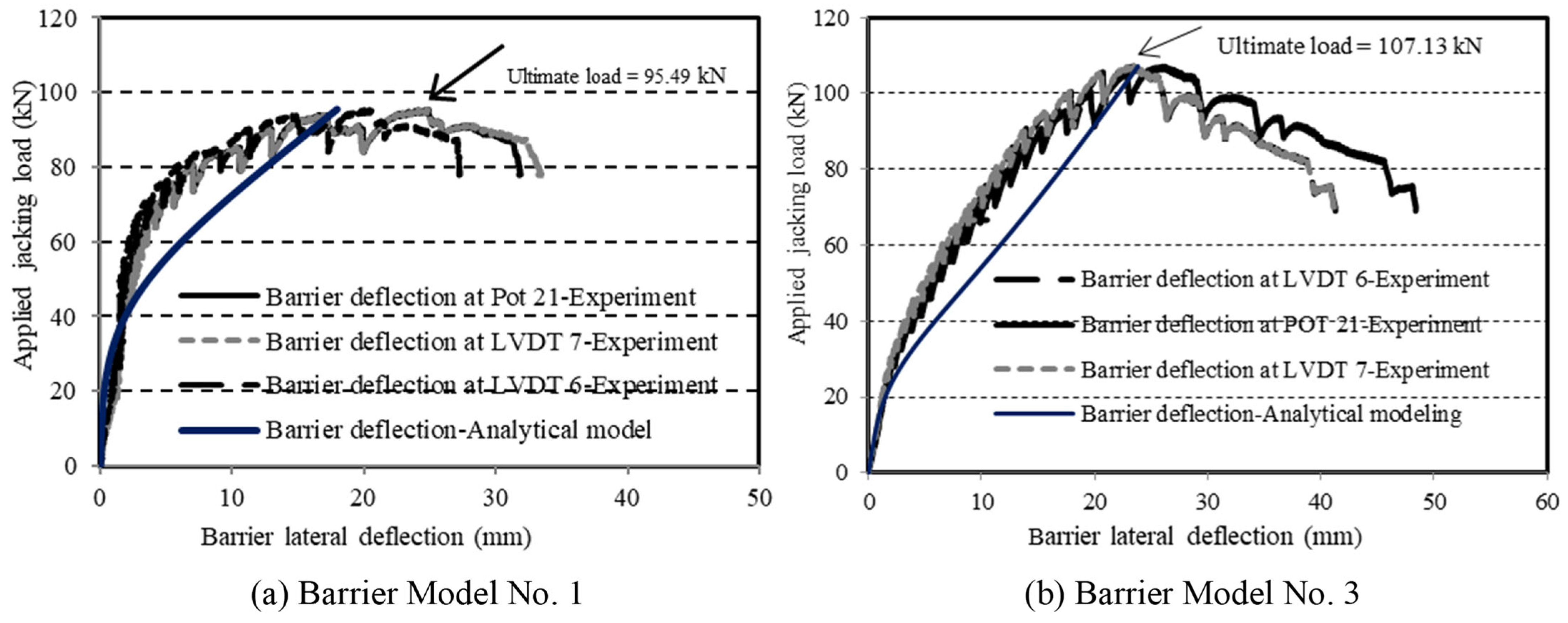

4.2. Cross-Sectional Analysis of Barrier Models

5. Investigation of Diagonal Tension Crack at the Barrier–Slab Overhang Joint

5.1. Capacity Versus Demand for the Diagonal Tension Failure at Barrier–Overhang Corner

5.2. Minimum Reinforcement Ratio for Concrete Diagonal Tension Crack

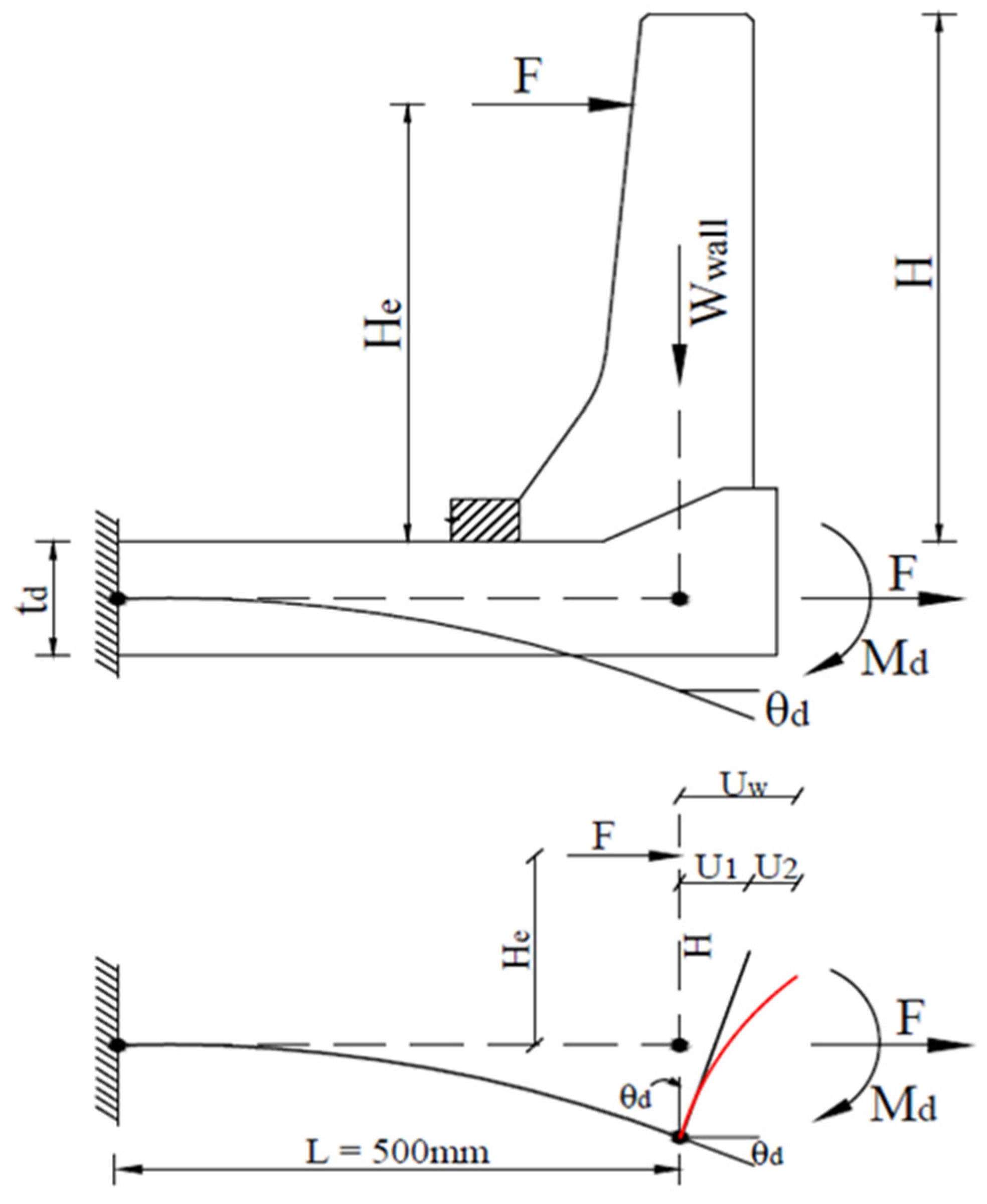

6. Analytical Modeling of Deck–Wall Connection

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- El-Tawil, S.; Nanni, A. GFRP Reinforcement for Concrete Structures: Design and Performance. J. Compos. Constr. 2007, 11, 377–387. [Google Scholar]

- Nanni, A.; El-Tawil, S. Design and Performance of GFRP Reinforcement in Concrete Structures. ACI Struct. J. 2009, 106, 747–754. [Google Scholar]

- Almusallam, A.; Al-Gahtani, A. Assessment of Corrosion Damage to Concrete Bridge Barriers. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2018, 14, 220–231. [Google Scholar]

- Rostami, M.; Sennah, K.; Azimi, H.; Afefy, H. Behavior and design of GFRP bar adhesive anchors under direct tension for deteriorated concrete bridge barrier replacement. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2025, 28, 13694332251334830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Performance of GFRP and BFRP Reinforcements in Marine and De-Icing Salt Environments. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 352, 129031. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, H.P. Assessment of Salt-Induced Corrosion in Bridge Barriers and Structural Health Monitoring Techniques. Struct. Control. Health Monit. 2024, 31, e2908. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, R.; Kumar, S. Innovative Use of GFRP Reinforcement for Bridge Barriers Exposed to Coastal and Salt-Spread Conditions. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 34, 105447. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S.P.; Sideris, P.J. Durability of GFRP Reinforcement in Concrete Structures. J. Compos. Constr. 2014, 18, 04014004. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhang, G. Environmental durability and corrosion resistance of GFRP bars in aggressive environments. J. Compos. Constr. 2021, 25, 04021008. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.R.; Zhang, Z. Corrosion Behavior of GFRP Reinforcement in Aggressive Environments. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 165, 468–477. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y. Long-term durability of GFRP bars in chloride-rich environments. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 316, 125567. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Kumar, A. Comparative analysis of corrosion behavior of GFRP and steel rebars in marine environments. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 81, 1234–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.; Ahmed, S. Durability performance of GFRP reinforcement in harsh environmental conditions. Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 238, 109935. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Lee, S.; Park, H. Innovations in GFRP reinforcement for sustainable construction: Environmental resistance and lifespan. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 30, e00567. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.I.; Aref, A.J. Mechanical Properties of GFRP Bars for Structural Applications: A Review. Compos. Struct. 2021, 280, 114950. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S.M.; Yousuf, T. Advances in GFRP Reinforcement for Concrete Structures: Mechanical Properties and Structural Performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 345, 128394. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H. Recent Progress in GFRP Reinforcement: Mechanical Performance and Structural Benefits. J. Compos. Constr. 2023, 27, 04023011. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.S.; Sennah, K.; Afefy, H.M. Structural Behavior of Full-Depth Deck Panels Having Developed Closure Strips Reinforced with GFRP Bars and Filled with UHPFRC. J. Comp. Sci. 2024, 8, 468. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.S.; Sennah, K.; Afefy, H.M. Fatigue and Ultimate Strength Evaluation of GFRP-Reinforced, Laterally Restrained, Full-Depth Precast Deck Panels with Developed UHPFRC Filled Transverse Closure Strips. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Sennah, K.; Khederzadeh, H. Development of Cost-Effective PL-3 Concrete Bridge Barrier Reinforced with Sand-Coated GFRP Bars: Vehicle Crash Test. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2014, 41, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennah, K.; Hedjazi, S. Structural Qualification of a Developed GFRP-Reinforced PL-3 Concrete Bridge Barrier Using Vehicle Crash Testing. Int. J. Crashworthiness Taylor Fr. 2018, 24, 296–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennah, K.; Tropynina, E.; Ibrahim, Z.; Hedjazi, S. Structural Qualification of a Developed GFRP-Reinforced PL-3 Concrete Bridge Barrier Using Ultimate Load Testing. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2018, 12, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Rostami, M.; Sennah, K.; Afefy, H.M. Ultimate capacity of barrier-deck anchorage in MTQ TL-5 barrier reinforced with headed-end, high-modulus, sand-coated GFRP bars. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 45, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervishhasani, G.; Sennah, K.; Afefy, H.M.; Diab, A. Ultimate Capacity of a GFRP-Reinforced Concrete Bridge Barrier–Deck Anchorage Subjected to Transverse Loading. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAN/CSA-S6-25; Canadian Highway Bridge Design Code. Canadian Standards Association: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2025.

- AASHTO. AASHTO-LRFD Bridge Design Specifications, 3rd ed.; American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- AASHTO. AASHTO Guide for Selecting, Locating, and Designing Traffic Barriers; American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials: Washington, DC, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- AASHTO. AASHTO Guide Specifications for Bridge Railings; American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials: Washington, DC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Rostami, M.; Sennah, M.; Hedjazi, S. GFRP Bars Anchorage Resistance in a GFRP-Reinforced Concrete Bridge Barrier. Mater. J. 2019, 12, 2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sennah, K.; Mostafa, A. Performance of a Developed TL-5 Concrete Bridge Barrier Reinforced with GFRP Hooked Bars: Vehicle Crash Testing. ASCE J. Bridge Eng. 2018, 23, 04017139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, M.; Sennah, M.; Mostafa, A. Experimental Study on the Transverse Load Carrying Capacity of TL-5 Bridge Barrier Reinforced with Special Profile GFRP Bars. ASCE J. Compos. Constr. 2019, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khederzadeh, H.; Sennah, K. Development of Cost-Effective PL-3 Concrete Bridge Barrier Reinforced with Sand-Coated GFRP Bars: Static Load Tests. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2014, 41, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M. Reinforcement Detailing in Concrete Frame Corners. ACI Struct. J. 2001, 98, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skettrup, E.; Strabo, J.; Andersen, N.H.; Brondum-Nielsen, T. Concrete Frame Corners. ACI Struct. J. 1984, 91, 587–593. [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield, B.; Kong, F.K.; Bennison, A. Strength and Stiffness in Lightweight Concrete Corners. ACI Struct. J. 1972, 69, 420–427. [Google Scholar]

- Yamin, J.L. A Review of Reinforced Concrete Corner Joints Subjected to Opening Moments. Concr. Int. Am. Concr. Inst. 2024, 46, 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti, M.L.; Tassios, T.P.; Vintzileou, E. Behavior and Design of Corner Joints under Opening Bending Moment. ACI Struct. J. 2014, 111, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, S.; Ruiz, M.F.; Muttoni, A. Behaviour of nodal regions of reinforced concrete frames subjected to opening moments and proposals for their reinforcement. Eng. Struct. 2013, 51, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczecina, M.; Winnicki, A. Rational Choice of Reinforcement of Reinforced Concrete Frame Corners Subjected to Opening Bending Moment. Materials 2021, 14, 3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monserrat-López, A.; Faria, D.M.; Brantschen, F.; Ruiz, M.F. Performance of nodal regions of reinforced concrete frame corners subjected to opening bending moments. Eng. Struct. 2025, 322 Pt A, 119041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, G.; Tolnai, M.; Gokani, V.; Picón, R.; Yang, S.; Klingner, R.E.; Williamson, E.B. Design of Retrofit Vehicular Barriers Using Mechanical Anchors; Report No. FHWA/TX-07/0-4823-CT-1; Texas Department of Transportation: Austin, TX, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, D.Y.; Jeong, H.S.; Choi, J.W. A Study of the Bolt Connection System for a Concrete Barrier of a Modular Bridge. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Innov. 2018, 8, 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Xie, Z.; Yang, B.; Li, L.; Wang, R.; Chen, W. Impact resistance performance of precast reinforced concrete barriers with grouted sleeve and steel angle-to-plate connections. Eng. Struct. 2024, 316, 118533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, G.; Sennah, K.; Azimi, H.; Lam, C.; Kianoush, R. Development of Precast Concrete Barrier Wall System for Bridge Decks. J. Prestress. Concr. Inst. (PCI) Winter 2014, 2014, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo, D.; Aguiniga, F.; Buth, C.E.; James, R.W.; Keating, P.B. Pendulum Impact Tests on Bridge Deck Sections; Report No. FHWA-01/1520-1; Texas Department of Transportation: Austin, TX, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon, A.; McLure, R.M.; Spitzer, P.; Tessaro, T.; Aminmansour, A. Performance Characteristics of Case-in-Place Bridge Barrier; Report No. PA-89-018+87-21; Pennsylvania Department of Transportation: Harrisburg, PA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Frosch, R.J.; Morel, A.J. Guardrails for Use on Historic Bridges: Volume 2—Bridge Deck Overhang Design; Joint Transportation Research Program, Publication No. FHWA/IN/JTRP-2016/34); Purdue University: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodayari, A.; Mantawy, I.M.; Azizinamini, A. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Prefabricated Concrete Barrier Systems Using Ultra-High-Performance Concrete. Transp. Res. Rec. 2023, 2677, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deitz, D.; Harik, I.; Gesund, H. GFRP Reinforced Concrete Bridges; Report No. KTC-00-9; Kentucky Transportation Center: Lexington, KY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rostami, M.; Sennah, K.; Afefy, H. Experimental capacity of TL-4 concrete barrier-deck connection using GFRP-bars with reduced-radius 180° hooks and adhesive GFRP anchors. Struct. Concr. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Afefy, H.; Sennah, K.; Azimi, H.; Sayed-Ahmed, M. Bond Characteristics of Glass Fiber Reinforced Polymer Bars in High-Strength Concrete. J. Struct. Build. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. 2022, 175, 748–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Afefy, H.; Azimi, H.; Sennah, K.; Sayed-Ahmed, M. Bond performance of sand-coated and ribbed-surface glass fiber reinforced polymer bars in high-performance concrete. J. Struct. 2021, 34, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Afefy, H.; Sennah, K.; Azimi, H. Bond characteristics of straight- and headed-end ribbed-surface GFRP bars embedded in high-strength concrete. J. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 83, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pultrall. GFRP Manufacturer Data Sheet; Pultrall Inc.: Thetford Mines, QC, Canada, 2011; Available online: https://pultrall.com/en/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- MacGregor, J.G. Reinforced Concrete, Mechanics and Design, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1997; 939p. [Google Scholar]

- CSI. SAP2000 Software Integrated Finite Element Analysis and Design of Structures; Computers and Structures Inc.: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ISIS. ISIS Canada Module 3—An Introduction to FRP Composites for Construction; Prepared by ISIS Canada; Department of Civil Engineering, Queen’s University: Kingston, ON, Canada, 2006; 36p. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, I.H.E.; Losberg, A. Reinforced concrete corners and joints subjected to bending moment. J. Struct. Div. 1976, 102, 1229–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, F.; Nanni, A. Connection of Concrete Railing Post and Bridge Deck with Internal FRP Reinforcement. ASCE J. Bridge Eng. 2009, 14, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSA-A23.3-24; Design of Concrete Structures. Canadian Standards Association: Mississauga, ON, Canada, 2024.

| Model No. | Description of Models |

|---|---|

| 1 | Model No. 1 with HM-GFRP straight and headed-end bars at 300 mm spacing |

| 2 | Model No. 2 with SM-GFRP-SM straight and bent bars at 200 mm spacing |

| 3 | Model No. 3 with SM-GFRP straight and 180°-hook bars at 200 mm spacing |

| 4 | Model No. 4 with HM-GFRP straight and headed-end bars at 150 mm spacing |

| 5 | Model No. 5 with conventional steel reinforcement at 200 mm bar spacing |

| Product Type | Bar Size | Guaranteed Tensile Strength (MPa) | Modulus of Elasticity (GPa) | Strain at Failure | Cross-Sectional Area (mm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High modulus (HM) | #4 (12M) | 1312 | 2.0% | 126.7 | |

| #5 (15M) | 1184 | 1.89% | 197.9 | ||

| Standard modulus (SM) | #4 (12M) | 941 | 53.6 | 1.76% | 126.7 |

| #5 (15M) | 934 | 55.4 | 1.69% | 197.9 | |

| SM-Bent | #5 (15M) | 473 (bent portion) | 50 | 1% | 197.9 |

| 1051 (straight portion) | |||||

| SM-180° hook | #5 (15M) | 473 (bent portion) | 50 | 1% | 197.9 |

| 1051 (straight portion) |

| Sample No. | Ultimate Load (kN) | fcore (MPa) | No. of Bars Inside | Remarks (Type of Bars) | Correction Factors | feq | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fl/d | Fdia | Fr | Fmc | Fd | ||||||

| 1 | 263.8 | 33.6 | - | No bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1 | 1.08 | 1 | 31.5 |

| 2 | 189.2 | 24.1 | - | No bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1 | 1.08 | 1 | 22.6 |

| 3 | 248.7 | 31.67 | - | No bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1 | 1.08 | 1 | 29.7 |

| 4 | 212.5 | 27.05 | - | No bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1 | 1.08 | 1 | 25.4 |

| 5 | 229.7 | 29.25 | - | No bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1 | 1.08 | 1 | 27.4 |

| 6 | 209.7 | 26.7 | - | No bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1 | 1.08 | 1 | 25.0 |

| 7 | 282.1 | 35.92 | - | No bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1 | 1.08 | 1 | 33.7 |

| 8 | 304.3 | 38.75 | - | No bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1 | 1.08 | 1 | 36.4 |

| 9 | 212.4 | 27.05 | 2 | Steel bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1.13 | 1.08 | 1 | 28.7 |

| 10 | 180.9 | 23.4 | 1 | Steel bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1 | 23.7 |

| 11 | 222.2 | 28.3 | 1 | Steel bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1 | 28.7 |

| 12 | 186.5 | 23.75 | 1 | Steel bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1 | 24.1 |

| 13 | 230.1 | 29.3 | 1 | Steel bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1 | 29.7 |

| 14 | 212.4 | 27.05 | 1 | FRP bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1 | 27.4 |

| 15 | 221.6 | 28.2 | 1 | FRP bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1 | 28.6 |

| 16 | 208.2 | 26.51 | 1 | FRP bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1 | 26.9 |

| 17 | 236.9 | 30.17 | 2 | FRP bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1.13 | 1.08 | 1 | 32.0 |

| 18 | 240.3 | 30.6 | 2 | FRP bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1.13 | 1.08 | 1 | 32.4 |

| 19 | 229.4 | 29.2 | 1 | FRP bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1 | 29.6 |

| 20 | 303.3 | 38.63 | 2 | FRP bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1.13 | 1.08 | 1 | 41.0 |

| 21 | 339.14 | 43.18 | 2 | FRP bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1.13 | 1.08 | 1 | 45.8 |

| 22 | 233.0 | 29.67 | 2 | FRP bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1.13 | 1.08 | 1 | 31.5 |

| 23 | 218.2 | 27.79 | 1 | FRP bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1 | 28.2 |

| 24 | 300.5 | 38.2 | 1 | FRP bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1 | 38.7 |

| 25 | 231.7 | 29.5 | 1 | FRP bars | 0.87 | 1 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1 | 29.9 |

| Barrier Model | Model No. 1 | Model No. 2 | Model No. 3 | Model No. 4 | Model No. 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Failure load, Fexp (kN/m) | 106.1 | 116.3 | 107.2 | 170.3 | 128.9 | |

| Height of load application, He (m) | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |

| Experimental moment in the wall at the base Mexp,w = Fexp. He (kN·m/m) | 105.0 | 115.1 | 106.1 | 168.6 | 127.3 | |

| Experimental moment in the deck at the joint Mexp,d = Fexp(He+0.5td), (kN·m/m) | 118.3 | 129.7 | 119.5 | 189.9 | 143.7 | |

| Resistance moment in the wall at the base—cross-sectional analysis Mr,w (kN·m/m) | 243.6 | 145.4 | 145.4 | 323.7 | 150.8 | |

| Resistance moment in the deck at the joint—cross-sectional analysis Mr,d (kN·m/m) | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | |

| FEA design moments—Mdesign (kN·m/m) | Interior location | 78 | 78 | 78 | - | 78 |

| Exterior location | - | - | - | 104 | - | |

| Capacity-to-demand ratio = Mexp,w/Mdesign | 1.35 | 1.48 | 1.36 | 1.62 | 1.63 | |

| Mr,w/Mexp,w | 2.32 | 1.26 | 1.37 | 1.92 | 1.18 | |

| Mr,d/Mexp,d | 1.30 | 1.19 | 1.29 | 0.81 | 1.02 | |

| Net lateral deflection of barrier wall (mm) | 24.5 | 31.3 | 23.3 | 43.2 | 17.8 | |

| Deck movement (mm) | 1.6 | 4.4 | 1.6 | 5.5 | 5.0 | |

| Deck uplift (mm) | 2.8 | 5.3 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 2.6 | |

| Barrier Model | αexp. (°) | αidealized (°) | b (mm) | db (mm) | ℓdc (mm) | f′c (MPa) | Mr,predict (kN·m/m) | FExp. (kN/m) | Mr,Exp. (kN·m/m) | Mr,Exp/Mr,predit Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 41 | 37.5 | 1000 | 192 | 479 | 25.4 | 101.6 | 106.1 | 106.5 | 1.17 |

| 2 | 43 | 37.5 | 1000 | 192 | 479 | 25.4 | 101.6 | 116.3 | 129.7 | 1.28 |

| 3 | 39 | 37.5 | 1000 | 192 | 479 | 25.4 | 101.6 | 107.2 | 119.5 | 1.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khederzadeh, H.; Sennah, K.; Afefy, H.M.; Razouk, K. Experimental and Analytical Evaluation of GFRP-Reinforced Concrete Bridge Barriers at the Deck–Wall Interface. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9110600

Khederzadeh H, Sennah K, Afefy HM, Razouk K. Experimental and Analytical Evaluation of GFRP-Reinforced Concrete Bridge Barriers at the Deck–Wall Interface. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(11):600. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9110600

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhederzadeh, Hamidreza, Khaled Sennah, Hamdy M. Afefy, and Kousai Razouk. 2025. "Experimental and Analytical Evaluation of GFRP-Reinforced Concrete Bridge Barriers at the Deck–Wall Interface" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 11: 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9110600

APA StyleKhederzadeh, H., Sennah, K., Afefy, H. M., & Razouk, K. (2025). Experimental and Analytical Evaluation of GFRP-Reinforced Concrete Bridge Barriers at the Deck–Wall Interface. Journal of Composites Science, 9(11), 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9110600