1. Introduction

A bushing is a simple mechanical component designed to provide a smooth surface for the movement of one part against another. It is typically a cylindrical lining that fits inside a hole, allowing a shaft, pin, or other components to move with reduced friction and wear. A torsional bushing is specifically designed to manage both rotational and axial loads. It is often made from an elastomer, such as rubber, that is bonded between inner and outer metal sleeves. Torsional bushings are commonly used in automotive suspensions and stabilizers. They enable controlled twisting (torsion) while providing cushioning, vibration isolation, and damping. Unlike simple bearings, torsional bushings have specific torsional stiffness and can accommodate axial and angular movements. However, complications can arise due to the nature of elastomer materials, as the relationship between forces, moments, and their corresponding deformations and rotations is nonlinear. Additional nonlinearities may also be present due to coupling between different modes of deformation [

1].

A common engineering application for torsional bushings is in anti-roll bars (ARBs), which are critical components of automotive suspension systems. Their purpose is to enhance stability, handling, and safety, ensuring the reliability and durability of modern vehicles [

2]. The bushing plays an essential role by maintaining the position of the ARB and reducing vibrations during operation. It enhances the roll stiffness of the ARB and directly impacts safety and comfort. If the bushings are damaged, they can lead to excessive vibrations and noise from the suspension system. Therefore, the degradation of bushings and the potential for fatigue failure pose significant concerns for ensuring the durability of this structural component.

Elastomer bushings are commonly used in vehicle chassis applications to enhance self-steering effects, improve vehicle handling, and increase ride comfort. However, a known issue with elastomer bushings is that their properties, such as stiffness and damping characteristics, can change significantly over their operational lifetime due to various factors, including thermal, chemical, and geometrical influences [

3]. This can lead to adverse effects compared to their initial design configuration.

To address this issue, a novel optimization algorithm, the chaotic krill herd (CKH), has been applied to optimize rubber bushing stiffness, which is a relevant challenge in the automotive industry. The results obtained with this algorithm have been compared with those from other methodologies, including genetic algorithms (GA), differential evolution algorithms (DE), and particle swarm optimization (PSO). The CKH algorithm demonstrated superior performance in reaching the global optimum of the objective function [

4]. Its effectiveness and validity have been confirmed through extensive testing using six different benchmark functions, as well as a nonlinear finite-element analysis of a rubber bushing.

An alternative to rubber bushings is oil-impregnated bronze bushings. These are durable and sometimes have a recessed bore. They are designed to keep grease on the inner shafts while keeping dirt out. Another option is polyurethane bushings, which are often made from proprietary blends tailored for specific conditions. Compared to standard rubber bushings, these materials provide advantages such as improved handling, increased safety, and a longer lifespan.

Most engineering applications focus on the complex behavior of bushings subjected to torsional vibrations. Recent efforts [

5,

6] have been dedicated to developing a calculation method and a torsional vibration suppression technique specifically for reciprocating compressor crankshaft systems. These studies take into account the effects of fit clearance and flexibility. Simulation results were obtained by integrating multibody dynamics to model the behavior of crankshaft bushings and the coupling dynamics of a compressor crankshaft system, while considering the crosshead pin clearance.

Therefore, building a multibody simulation with an accurate description of rubber bushings requires a nonlinear, time-dependent model that describes their mechanical behavior [

7]. However, the parameters associated with such a model can only be identified through experimental testing. A new modeling approach based on machine learning that can accurately predict the visco-hyperelastic behavior of materials under different loading conditions has been developed [

8]. This model benefits from mathematical simplicity and a fast, straightforward calibration process. It can be used for different structures and loading conditions, such as uniaxial tension, pure shear, and torsion.

The fatigue behavior of ARBs was studied using the finite element (FE) technique to determine the stress distribution of various polyurethane rubbers [

9]. It was found that soft rubber and thicker wall thicknesses reduce stress in the critical region and increase fatigue life. Paper [

10] proposes improving the overall durability performance of a vehicle suspension system by modifying the compliance of elastomeric bushings. Using finite element analysis, the stress distribution of the vehicle suspension system was calculated to determine the optimal elastomeric bushing compliance and maximize stress distribution to increase fatigue life.

In [

11], a vibro-acoustic reduced-order model based on substructuring using undeformed coupling interfaces is proposed to model the local dynamic stiffness of rubber bushings. Alternatively, a waveguide dynamic stiffness model of an arbitrarily wide and long rubber bush mounting was developed within the audible frequency range [

12]. The stiffness depends strongly on frequency and displays acoustic resonance phenomena influenced by material properties and bush mounting configuration.

The radial stiffness of rubber bush mountings has been extensively studied [

13,

14,

15]. Since loads from bushings are important factors in predicting the fatigue life of a component and the dynamic characteristics of a vehicle, the linear characteristics of a bushing are approximated using finite element analysis and applied to a multibody dynamic vehicle model. Using the compliance of the front suspension bushings as a design parameter, the Taguchi method is employed in a robust design process to reduce the stress value of the lower control arm [

14]. More recently, a torsional stiffness model of the coupling that considers the influence of excess was constructed using finite element and response surface theory. It was verified that the model compensates for the loss of high-frequency vibration information [

15]. Secondly, the Sobol’s method is used to explore the sensitivity of the coupling torsional stiffness eigenvalues to the structure-excess parameter.

The frequency characteristic is optimized using a genetic algorithm [

16]. The bushing stiffness and the bushing installation angle, which greatly influence the frequency characteristics, are taken as the optimization variables, and the frequency characteristic index is taken as the optimization goal. The optimal design of a bionic flexible rubber bushing structure considers a hyper-viscoelastic model, which is selected as the constitutive model of the rubber material [

17]. Additionally, a design that optimizes vibration damping can effectively alter the motion characteristics of the rubber bushing under various working conditions, providing new inspiration for future rubber bushing designs.

Through parametric test design, the front subframe bushing stiffness is selected as a design variable to establish a rigid–flexible coupled vehicle model. Simulations of the suspension kinematics and compliance, as well as steering simulations, are performed on the vehicle [

18]. Similarly, a tube-beam front subframe was optimized to meet performance and lightweight requirements for a rigid–flexible structural component. Topology optimization was conducted using Optistruct analysis software to determine the subframe layout and optimal cross-member position [

19].

In the field of additive manufacturing (AM), there is an urgent need for rigid–flexible, multi-material, three-dimensional (3D) printing to replace conventional manufacturing methods and optimize mechanical performance. Significant advancements in PolyJet 3D printing of fiber-reinforced and functionally graded structures with various material composition modifications are reviewed in [

20]. Despite the benefits of PolyJet manufacturing, the limitations and challenges demonstrate the need for further research in this field to significantly enhance fabrication quality.

Hard–soft mechanical interplay [

21] is obviously necessary for 3D multi-material printing. Developing a rigid–flexible coupling interpenetration network of dielectric insulators is key to advancing power systems. Refined light-based 3D printing enables reversible crosslinking, which allows for the reprocessing of printed objects. In this context, a novel strategy was implemented to create a mechanically robust and sustainable vitrimer: a rigid–flexible coupling interpenetration network was constructed. This process uses a two-stage curing approach to produce high-performance 3D-printed vitrimers. To avoid issues related to weak layer-interface compatibility, greater penetration depth was achieved in the 3D printing process [

22]. Additionally, the thermally cured epoxy network that interacts with the printing interface significantly enhances the compatibility of the samples. The interpenetration network exhibits minimal anisotropy, with a bending strength double that of the photosensitive resin.

Incorporating flexibility into the design of a torsional bushing has led to the development of composite structures consisting of soft and, in some cases, hard phases distributed across various length scales. AM, particularly 3D printing, is an appealing method for replicating the complex structures found in nature and allows for the assembly of intricate topologies [

23]. This technique demonstrates the ability to distribute materials with different mechanical properties and incorporate advanced interfacial designs.

However, the 3D printing manufacturing process often involves changing materials, which can introduce or increase anisotropy in the final product. Additionally, the complexity of part geometries and loading conditions often requires the finite element method to simulate behavior under service conditions. One interesting study reverse-engineered a bushing for a hinged drawer support, simulated its in-service performance, and then manufactured it using Tough PLA material through 3D printing [

24]. The study also evaluated the effects of anisotropy and friction on the design.

The goal of this research is to mitigate torsion loads and delay failure under high angular displacement. This is achieved by designing a novel, fully customizable hybrid bushing structure through AM that can be adapted to the required damping performance. This design serves as a proof of concept, demonstrating the feasibility and viability of the idea. The proposed design features elastic thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) layers that are interconnected, and rigid polylactic acid (PLA) layers arranged in a controlled stacking sequence and overlapping configuration. This approach balances compliance and stiffness. Previous studies have shown that a gyroid core provides lightweight structural integrity and evenly distributes stresses. The TPU layers serve as regions for vibrational energy absorption and can help reduce the likelihood of high oscillation amplitudes. Meanwhile, the PLA layers offer dimensional stability and enable progressive load transfer, allowing for substantial torsional angles before failure. This hybrid bushing structure is ideal for use in automotive couplings, robotic joints, and precision machinery mounts where vibration isolation and resilience to high angles are critical.

This paper examines various infill patterns used for 3D printing traction specimens made of PLA and TPU to determine their mechanical properties and identify the optimal printing configuration. We analyze how consecutive layers interlock to create a mechanical connection between the flexible TPU gyroid core and the rigid PLA casing of the bushing. We conduct quasi-static and repetitive-cycling torsion tests to show that this innovative bushing design is an effective foundation for torsional vibration testing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Additive Manufacturing Procedure

The fused deposition modeling (FDM) printer, Raise3D E2 (Shanghai, China), used to fabricate the bushings, is an industrial-grade FDM printer designed to maximize productivity with its independent dual extruder system for duplication and mirror modes. The used slicer is IdeaMaker, developed and adapted for Raise3D printers, and it allows for downloading presets tested by the manufacturer for particular filaments.

The flexible TPU used for printing the specimens was NinjaFlex

® 85A Red (NinjaTek, Lititz, PA, USA), with a hardness of 85 Shore A, and the mechanical specification established by the producer for specimens with 100% infill as tensile yielding stress—4 MPa; tensile ultimate strength—26 MPa; Young’s modulus—12 MPa; elongation at break—660% [

25]. The rigid selected material for this project is Raise3D Premium PLA White (Raise 3D Technologies, Houston, TX, USA). According to the manufacturer, this PLA exhibits the following mechanical properties in the X-Y horizontal plane of printing for specimens with 100% infill: tensile ultimate strength—40 ± 1 MPa; Young’s modulus—2681 ± 215 MPa; elongation at break—2.5 ± 0.6% [

26]. The hardness Shore D is 84.

Several infill patterns were evaluated to assess their mechanical tensile properties. These infill patterns, illustrated in

Figure 1, were tested using specimens made from both PLA and TPU materials, featuring different angle inclinations in the printing directions. The printer settings were initially configured for TPU; however, PLA was printed using the same settings. The printer does not allow for the simultaneous use of both materials, as it considers them incompatible. Nevertheless, the adjusted settings enabled the successful printing of the torsion bushing.

The infill was generated using a rectilinear pattern with an infill overlap of 30%, and the printing pattern was connected to 2.5 perimeter contour shells with an overlap of 15%. Printing temperatures were set to 205 °C for PLA and 235 °C for TPU, while the build platform was maintained at 50 °C. To minimize warping and other surface defects, a PLA raft was used during fabrication for both printed specimens. The printing speed was set to 20 mm/s for both materials, which is the maximum acceptable value for quality TPU printing.

Regarding the materials’ mechanical characterization, PLA has been tested under tensile loads according to ISO 527-1 [

27]. As TPU is an elastomeric material, the tensile properties were collected by printing samples according to ISO 37 [

28].

Depending on the infill pattern, the details on time of printing for five specimens and mass of specimens and rafts are given in

Table 1.

It is to be noted that the printing with TPU lasts significantly less time, and the mass of the specimens and of the rafts is the same for all infills. For PLA, the printing time is almost double as the specimens are larger in dimensions.

2.2. Specimens for Testing

Traction specimens were printed according to the previously mentioned standards for PLA and TPU materials, and their dimensions are presented in

Figure 2. Five specimens for each infill are printed, and raft printing is chosen to ensure easy separation and a high-quality surface finish on the bottom of the specimen. Once the print is complete, the raft peels away from the print.

In order to verify the locking between PLA and TPU in the interconnected part, additional specimens were designed and tested in traction. The thickness of the specimens is 6 mm and the width 10 mm. In

Figure 3, the length

a is varied as 1 mm, 2 mm, and 3 mm, as the overall dimensions were selected to ensure that the interconnection between TPU and PLA mostly replicates the configuration of the bushing to be tested in torsion. This approach ensures that the mechanical interaction between the two materials in the traction test samples accurately reflects the conditions of the designed component. Over a thickness of 6 mm, there are a total of 15 layers (8 TPU and 7 PLA). The printing of two consecutive layers that are each 0.2 mm thick gives the 0.4 mm layer.

For the overlap of 2 mm and an infill of 0/90 degrees, printing such a specimen takes 3 h and 17 min for 5 samples, and consumes 15.2 g of PLA (at both ends) and 7.1 g of TPU. If the infill is 45/135 degrees, the needed time is 3 h and 18 min, and the required quantities are the same for PLA and 7.0 g for TPU.

The gyroid cells, respectively, the core of the bushing, were designed by using the software Autodesk Fusion (Autodesk, San Francisco, CA, USA) by using the Volumetric Model and setting the cell size to 15 mm and the relative density, named in this software solidity, to 0.2 (0 meaning empty volume and 1 full volume, that is, without cells). Of these two parameters, the Volumetric Lattice tool auto-computes the wall thickness from solidity as being theoretically 1.07 mm, which accounts for the curved geometry and nonlinear scaling with the cell size. However, this thickness is theoretically established for ideal conditions. As in physical print, under-extrusion or surface roughness can reduce effective solidity; it is recommended to increase wall thickness. When exporting as STL, the software may prioritize robustness and increase the wall thickness. Fusion software uses a volume fraction material distribution and does not account for an exact wall thickness as designed. The conversion process from solid to meshing and the accuracy of curved surfaces cause the effective wall thickness to increase. For example, even if the theoretical wall thickness is approximately 1.07 mm, the exported model will have a thickness of 2.3–3.0 mm. This makes the model easier to print and generate.

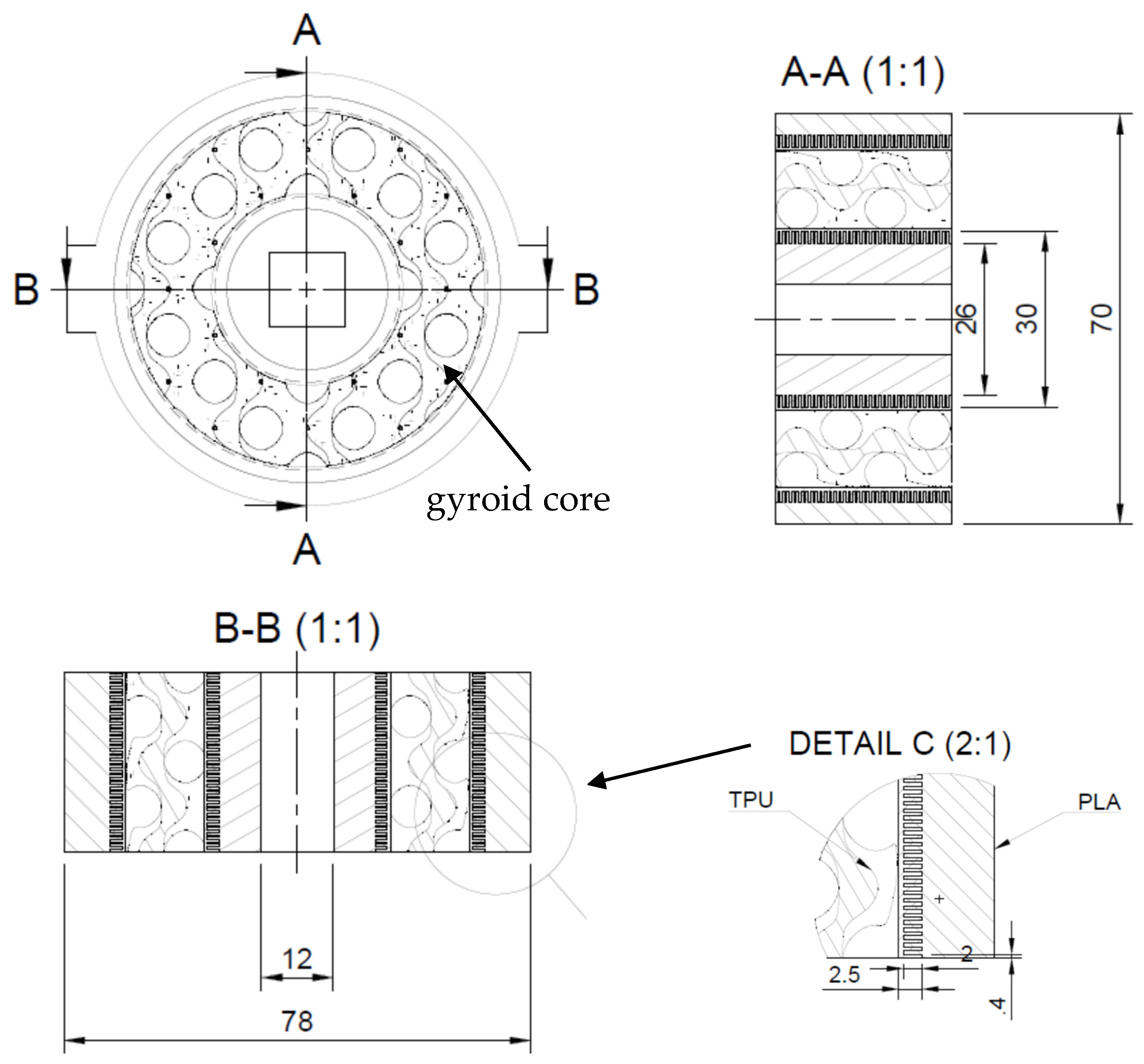

Special attention is given to the complete printing of the bushing that is subjected to torsion. The geometrical configuration design is depicted in

Figure 4. The height (thickness) of the bushing is 30 mm. In the middle of the bushing, a 12 mm square hole is configured to apply the moment of torsion through an inserted shaft (to be further detailed). The TPU gyroid core has two inner and outer circular sleeves of 2 mm thickness each. Within these sleeves, between the two materials, are interconnected successive layers of 0.2 mm thickness (0.4 mm for both PLA and TPU as in

Figure 3), as shown in detail C. The overlap length between the two materials is 2 mm on each side of the core, extending through the entire thickness of the bushing. This design ensures a proper mechanical connection between the two materials. Increasing overlap improves adhesion between infill lines and shell walls; slicers typically use 15–30% for strong interlocking between shells. A 2 mm segment length keeps infill close to the walls, maximizing overlap and reducing weaker spots. Segments that are too short (1 mm) impact filament continuity, while longer ones (3 mm) are affected by misalignment and thermal contraction. At 2 mm, the extrusion process remains unaffected, minimizing voids and defects. The length is ideal for thermal behavior—long enough to stay warm but short enough to cool uniformly, ensuring strong interlayer bonding. Very short segments cool too quickly, and long ones may be affected by heat, causing internal residual stresses. With a 45/135 infill pattern, 2 mm segments align intersections correctly, improving load transfer and overall strength. Each infill line overlaps the shell along its length, creating a structure with fewer voids and defects.

Considering a thickness of 30 mm, a total number of 150 layers were printed, consisting of 76 TPU layers of 0.2 mm and 74 PLA layers of the same thickness. Two consecutive layers are printed for each material; thus, as shown in detail C, each final layer has a thickness of 0.4 mm, and there are 38 TPU and 37 PLA interpenetrated layers. The TPU layers are first top and bottom (

Figure 4, detail C).

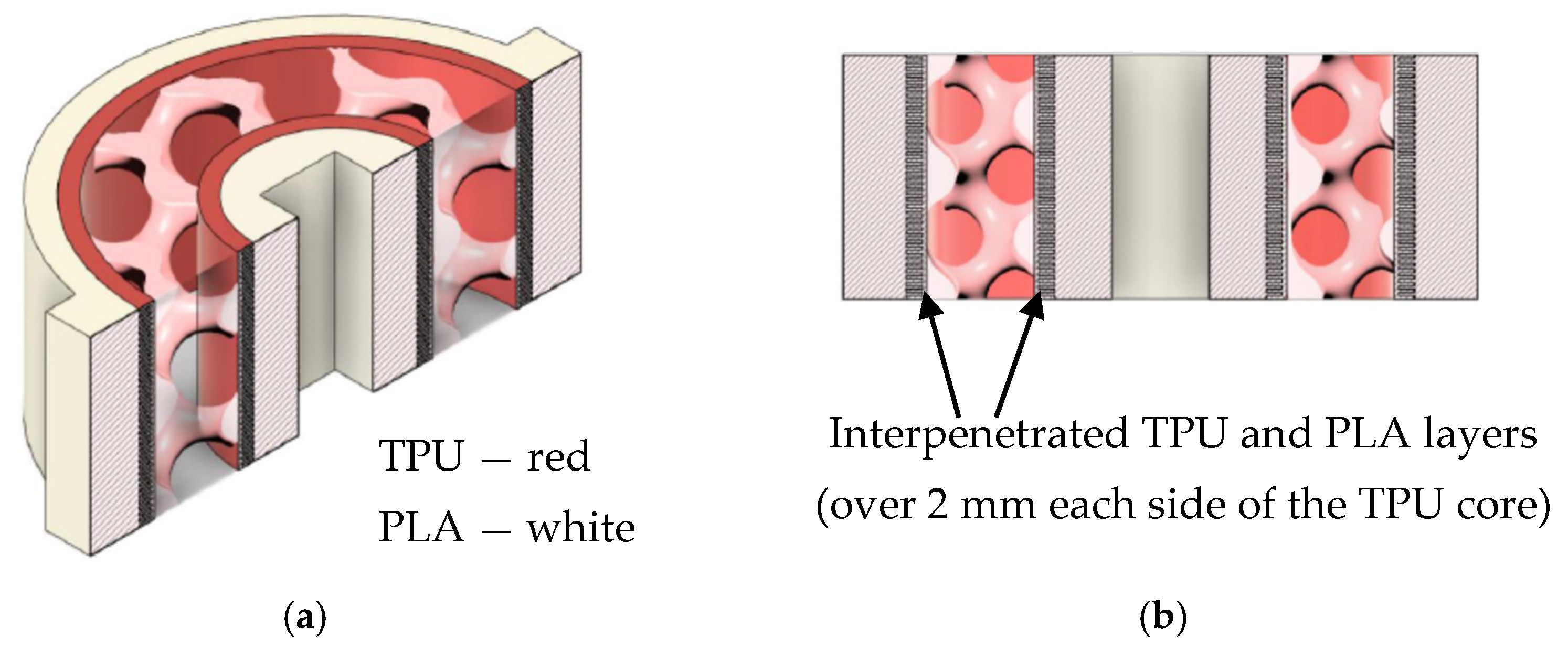

The bushing is exported as an STL file (

Figure 5) and can be viewed in two sections (

Figure 5a,b) and in a top view (

Figure 5c). The interpenetrated TPU and PLA layers over 2 mm are to be seen in the top view, with red color on both sides of the gyroid core, as the first layer is TPU. A photo of the printed torsion bushing is shown in

Figure 5d.

The bushing to be tested for torsion (

Figure 6) is mounted in an outer case made of TPU that is specially designed to fit the bottom grip of the testing machine. A 12 mm square shaft is inserted into the middle of the bushing (

Figure 4) and fixed in the upper grip, which rotates at a specified angle. The angle gradually increases up to 70°, and repetitive torsion loading is also applied.

2.3. Testing Equipment

The testing equipment used for the traction tests includes a Zwick-Roell Z010 testing machine (Zwick-Roell, Ulm, Germany) with a capacity of 10 kN. This machine is connected to a Hottinger signal amplifier (HBK, Darmstadt, Germany), which ensures accurate force measurement readings for a Zeiss 12MP ARAMIS system (Carl Zeiss GOM Metrology GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany). In this testing setup, each acquired image is associated with a load value measured in volts, with a conversion factor of 1 V representing 2 kN. The crosshead speed during testing was set to 2 mm/min.

The bushing was loaded in torsion using an Instron 8850 axial–torsion machine (Instron, Norwood, MA, USA) of 100 kN by using an integrated biaxial actuator. Torsion tests were conducted by imposing a specific angle of rotation and measuring the corresponding moment of torsion.

3. Results

3.1. Traction Testing

The traction test for both materials was performed for the infill patterns shown in

Figure 1. As TPU experiences large deformations during testing, it is not possible to use an extensometer, and the digital image correlation (DIC) technique was used to monitor in situ the quasi-static testing performed at a loading speed of 2 mm/min. The force measured with the testing machine’s force transducer was registered directly with the Zeiss Aramis 12 MP system at each loading stage, together with the deformation fields. The system was calibrated using the CP40/170 caliber. The analysis required using a facet size of 25 pixels and a point distance of 13 pixels on a full-resolution sensor of 12 MP. Data acquisition was performed at three frames per second. The conventional stress–strain curves were fully recorded until the failure of the PLA specimens, which occurred at elongation at break between 6% and 18%, depending on the infill pattern. For the TPU specimens, traction testing was possible until a strain of around 80%, beyond which the stretched specimen was out of the visual field of two cameras, or large deformations compromised the painted pattern on the surface of the specimens, and facets were no longer visible.

The Poisson ratios for both materials were determined using strains measured using Aramis. For PLA, the longitudinal gage length is 50 mm, while for TPU it is 25 mm. The transverse strains are measured within the visual field of the mask used to eliminate edge effects at the boundaries of the specimen, which covers nearly the entire width of the traction specimens, with 13 mm for PLA and 6 mm for TPU.

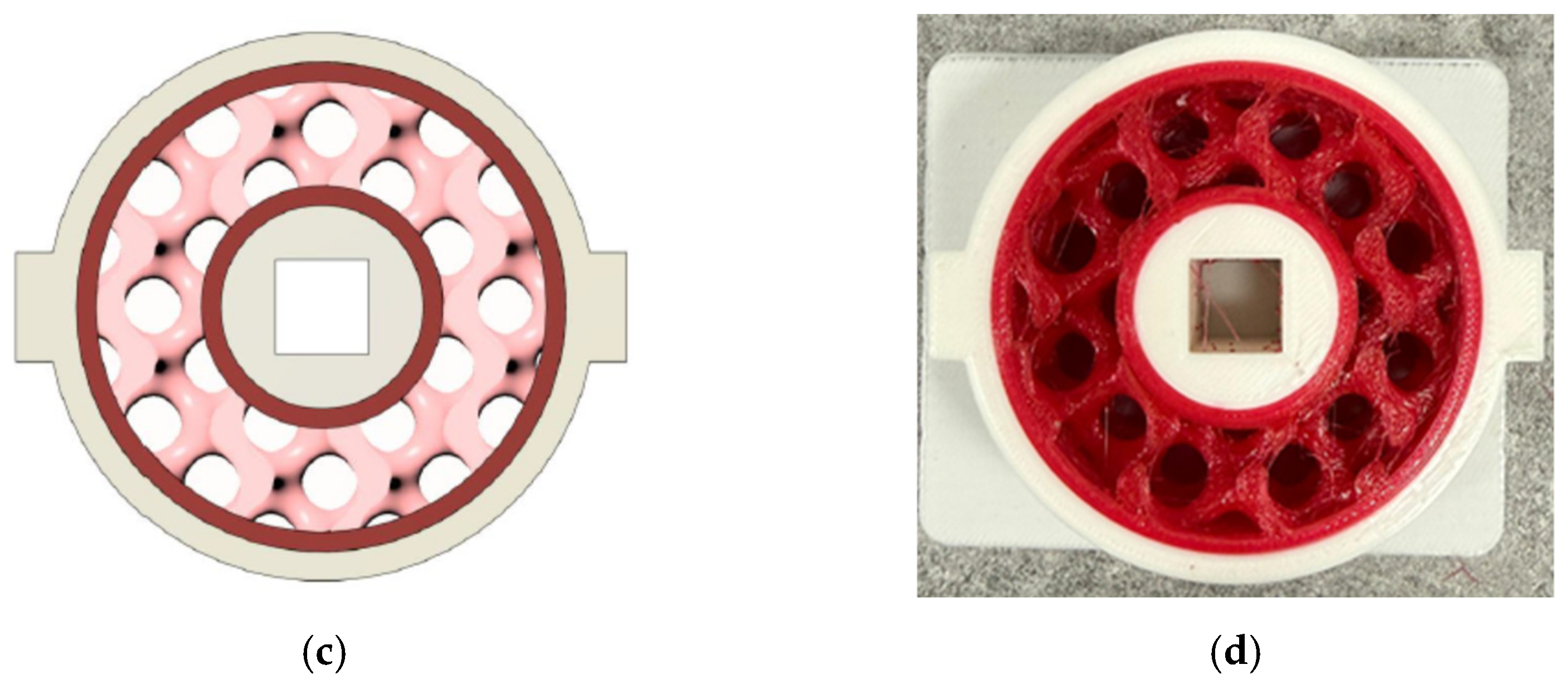

The conventional stress–strain curves for PLA material are displayed in

Figure 7 for all printed infill patterns. Each infill pattern was tested using five specimens. If a test was unsuccessful, it was excluded from the diagram. Generally, the maximum stress observed is approximately 40 MPa, achieved at a strain of 2%. At 0 degrees infill direction (

Figure 7a), the maximum stress reaches 45–47 MPa, and at 45/135 degrees (

Figure 7e), the same stress is between 42 and 43 MPa. However, greater ductility in the response of the specimens was observed when the infill was 45/135, as all tested specimens reached 7% strain, or 10% strain in four out of five specimens, before an evident decrease in the stress appeared, indicating local failures in the specimens. For 0 degrees infill (

Figure 7a), only two specimens reached 5% strain without failure, while the others failed earlier, one of them even at 2.3% (specimen 5). It is remarkable that for the 90 degrees infill shown in

Figure 7b, the maximum stress reaches even a value of 40 MPa.

The average (Aver.) main mechanical properties (out of four or five tests) for the five types of infills, together with the standard deviation (St. dev.) and coefficient of variation [%] (Var.), are presented in

Table 2.

As expected, the lowest Young’s modulus was obtained at 90 degrees infill, and the highest at 0 degrees infill; the percentage difference between the two extreme values was only 3.7%. The highest standard deviation is 102 MPa for the infill of 45 degrees. At 45/135 degrees, the average stiffness is a little bit lower than for 0 degrees, but ductility is higher.

Poisson’s ratio is on average 0.34–0.35, with an exception of 0.30 at 0/90 degrees, probably due to the specific infill pattern. The average maximum stress (max. stress) is maximum, as expected, at 0 degrees infill, close to 47 MPa, and about the same, about 43 MPa for 45 and 45/135 degrees infill. In all, the pattern of filling the specimens at 45/135 degrees is preferred for providing good stiffness and strength, as well as the highest ductility and data reproducibility.

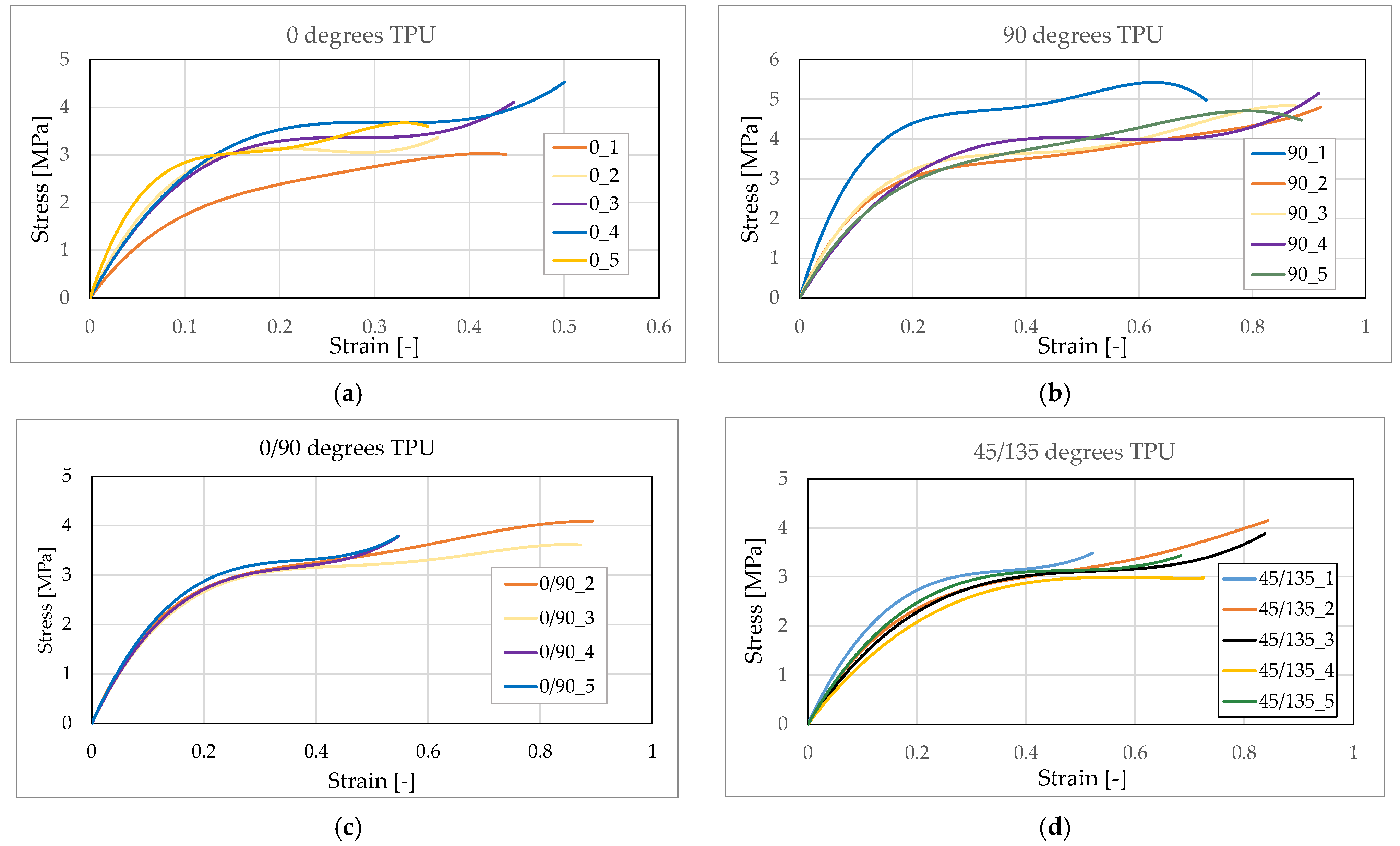

The traction stress–strain diagrams for TPU specimens (

Figure 2b) are presented in

Figure 8 for five tested specimens (at 0/90 degrees, one test was disregarded) at four infill configurations. Longitudinal and transversal strains were recorded to calculate Poisson’s ratio. As high deformations occur, it was possible to reach longitudinal strain only up to 100%, as the visual field to be seen with Aramis is limited.

For 0 degrees and 90 degrees infills, the curves are more scattered than for 0/90 and 45/135 degrees. The yielding stresses are generally limited to 4 MPa. As TPU behaves like an elastomer and is highly stretchable, it is very difficult to register strains higher than 50% in many cases, as some facets are no longer visible. On the other hand, it is obvious that delaminations occur between the 10 printed layers (0.2 mm thick), leading to local failures, and the test had to be stopped. Large deformations and anisotropy are critical issues for this printed material.

As for PLA results, the average main mechanical properties are presented in

Table 3 for four types of infills (45 degrees tests were not conducted as they were not relevant), together with the standard deviation and variation [%]. The highest average Young’s modulus is obtained for 0 degrees infill, as 33.36 MPa, followed by the 90 degrees infill pattern for which a value of 25.62 MPa was obtained. However, in both cases, the percentage variance is very high. Poisson’s ratio was established between 0.42 at 0 degrees and 0.51 at 0/90 degrees, but for this infill, the standard deviation and the variance are the highest.

The average yielding stress is below 4 MPa, with a surprising average value of 4.63 MPa at 90 degrees infill (due to an outlier specimen). At 0 degrees and 90 degrees infill (

Figure 8a,b), there is a very large scatter of the stress–strain curves. Although the highest Young’s modulus values were obtained at both infills, a high level of anisotropy is observed. The lowest standard deviations resulted for balanced infills of 0/90 degrees and 45/135 degrees.

A critical issue in this proof-of-concept torsion bushing is the interconnected layers of PLA and TPU that ensure the connection between the two printed materials (

Figure 3a). As the thickness of layers was established, the variable is the length over which the consecutive layers are joined. To test the efficiency of this type of interlocking, traction tests for overlapping lengths of 1 mm, 2 mm, and 3 mm were performed on five specimens of each type. The force at failure (

Figure 9a) and displacement at failure (

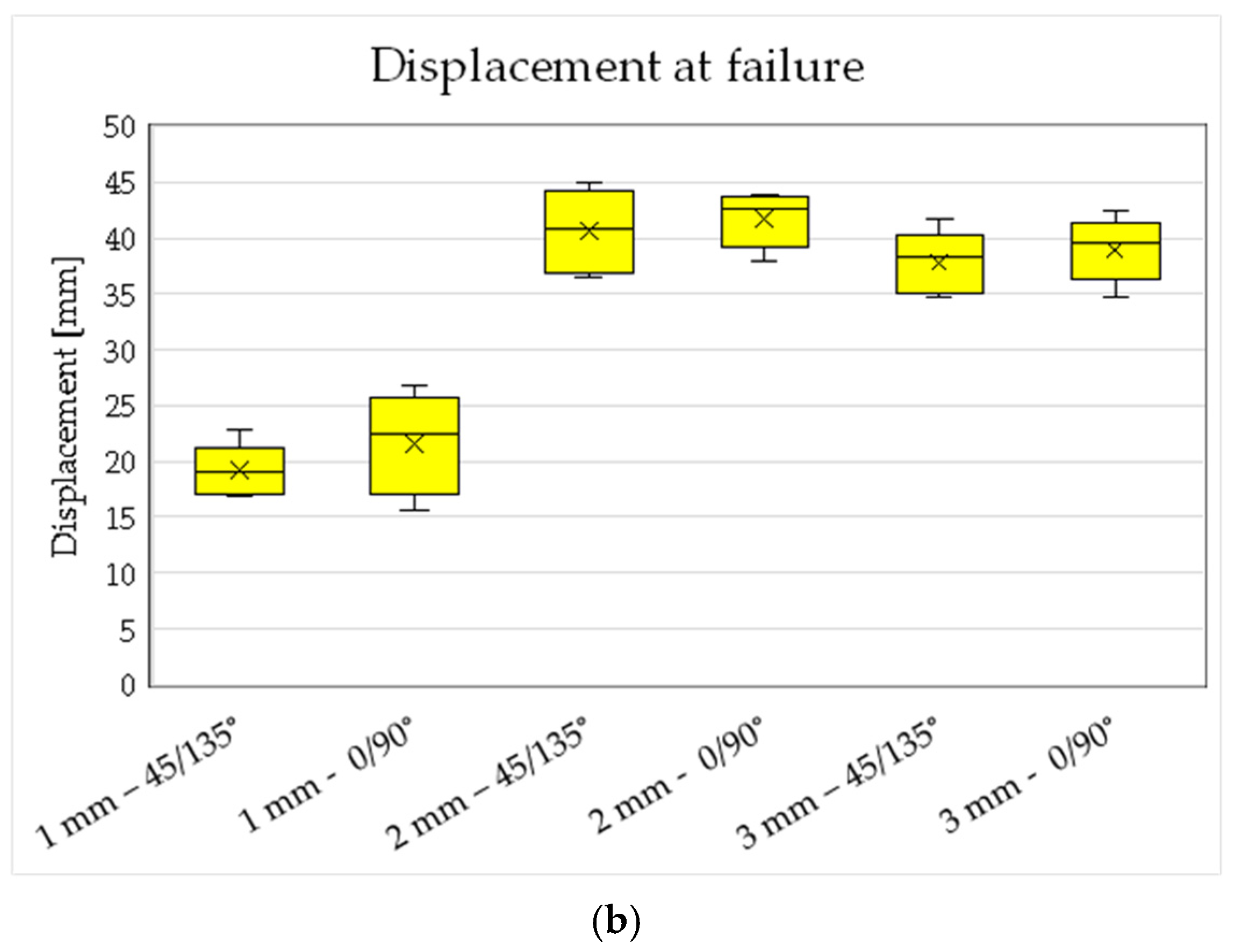

Figure 9b) variations are shown in boxplots for the three lengths of overlap. Only two infills, 0/90 degrees and 45/135 degrees, which were proven to be the best patterns, were considered for the printing. The force at failure for 1 mm is, on average, around 150 N; for 2 mm, around 200 N; and for 3 mm, it decreases, with better performance for the 45/135 degrees configuration. As the interlocking length increases, the likelihood of interface defects increases, reducing the maximum force.

The displacement at failure is about 20 mm for 1 mm overlap, which doubles to about 40 mm for 2 mm, and remains about the same (slightly decreasing) for 3 mm. Considering the presented results, the overlap length was finally chosen to be 2 mm.

3.2. Torsion Testing of the Bushing

The bushing was tested in torsion in two cases: (a) quasi-static increase in the rotation angle from 0° to 70° to test the failure response of the bushing; (b) loading–unloading 30 repetitive torsion cycles, with loading up to 60° angle of rotation followed by complete unloading.

For the quasi-static testing, two bushings were tested by gradually increasing the angle of rotation up to 70° with a twisting speed of 50 °/minute, as depicted in

Figure 10a. The moment of torsion was measured as the response given by the tested bushing. Data acquisition was performed at 10 Hz. Up to 30° of rotation, the response is linear, reaching a moment of torsion of 11.6 Nm. When the angle of rotation exceeds 30°, the response of the bushing becomes nonlinear as the two curves (

Figure 10a) start to separate. Close to 60° rotation and a torque of 20 Nm, no local failure occurs. Irregularities in the curves start to appear, indicating slight decreases followed by increases in the torsion moment as local internal damage appears. Following these tests, it was decided to apply the loading–unloading 30 repetitive torsion cycles up to 60° in order to estimate the response of the bushing. The 30 cycles lasted 600 s (three sequences of 10 cycles each lasting 200 s), for a total of 20 s per cycle. The cyclic speed of twisting in applying the angle of rotation is 360°/minute. As shown in

Figure 10b, the measured torque decreases constantly from 16 Nm to about 10 Nm at the end of the testing, indicating a gradual reduction in the torsion capacity of the bushing. As readings were performed at a frequency of 50 Hz, the complete spectrum of the measured data is shown in

Figure 10c.

The decrease in the torsion capacity of the bushing indicates local damage and a possible viscoelastic response during testing. It is difficult to quantify the extent to which each of these factors contributes to the decrease.

To better understand the bushing’s behavior during the loading cycles, the data were analyzed separately for the first and last 2500 recorded values (see

Figure 10d). The initial cycles, which lasted 50 s, displayed a hysteretic response from the bushing that had not yet stabilized. In contrast, the cycles had stabilized by the last 2500 readings, leading to a reduction in hysteretic effects. However, it is important to note that the twisting loading capacity decreased by 37.5%, dropping from 16 Nm to 10 Nm.

4. Conclusions

We propose a new design for a printed torsion bushing that creates a rigid–flexible connection for a specific topology. The interlocking of two materials, PLA and TPU, produced through layer-by-layer printing, demonstrates the proof of concept. DIC was used for the traction testing of specimens with different infill angles to quantify the stress–strain curves and Poisson’s ratios for both materials. The results showed that filling the specimens at 45/135 degrees is preferable because it provides good stiffness, strength, ductility, and reproducible data. Special attention was given to determining the infill overlap length between the two materials at the torsional bushing interface. Successive traction testing of specially designed specimens demonstrated that an overlap length of 2 mm leaves the extrusion process unaffected, minimizing voids and defects while ensuring strong interlayer bonding.

The designed bushing was subjected to torsional loads under quasi-static singular and repetitive imposed angular rotations. The results indicate that the bushing can accommodate significant rotation angles of up to 60 degrees and is sufficiently flexible for this application. This study primarily aims to evaluate the suitability of TPU and PLA materials for such an interlocking design, particularly in dynamic mechanical environments where flexibility, durability, and energy absorption are critical factors.

The most important outcome is that the proposed design concept for a 3D printed torsional bushing is viable. It effectively combines a flexible gyroid core with a rigid casing, thereby enhancing the deformation capacity of this structural component.

As proof of concept, we demonstrated the feasibility and viability of this new design. These preliminary results show that additive manufacturing can produce hard–soft mechanical interplay for engineering applications. In the near future, we plan to quantify the viscoelastic behavior of the bushing, which can be further developed and validated under dynamic torsional vibrations.