Facile Synthesis of Cellulose Whisker from Cotton Linter as Filler for the Polymer Electrolyte Membrane (PEM) of Fuel Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

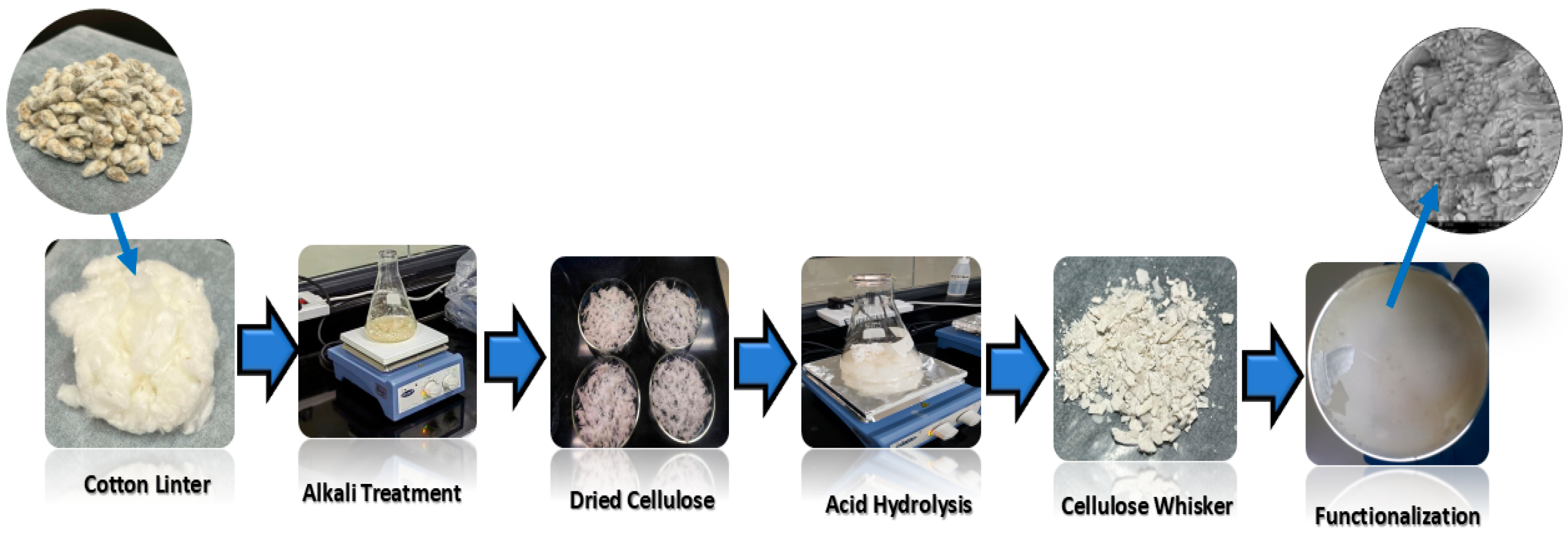

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Alkali Treatment

2.3. Acid Hydrolysis

2.4. Functionalization

2.5. Characterization of Cellulose and Cellulose Whiskers

2.6. Hybrid Membrane Preparation

2.7. Statistical Experimental Design and Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Material Selection and Profiling of Biomass Wastes

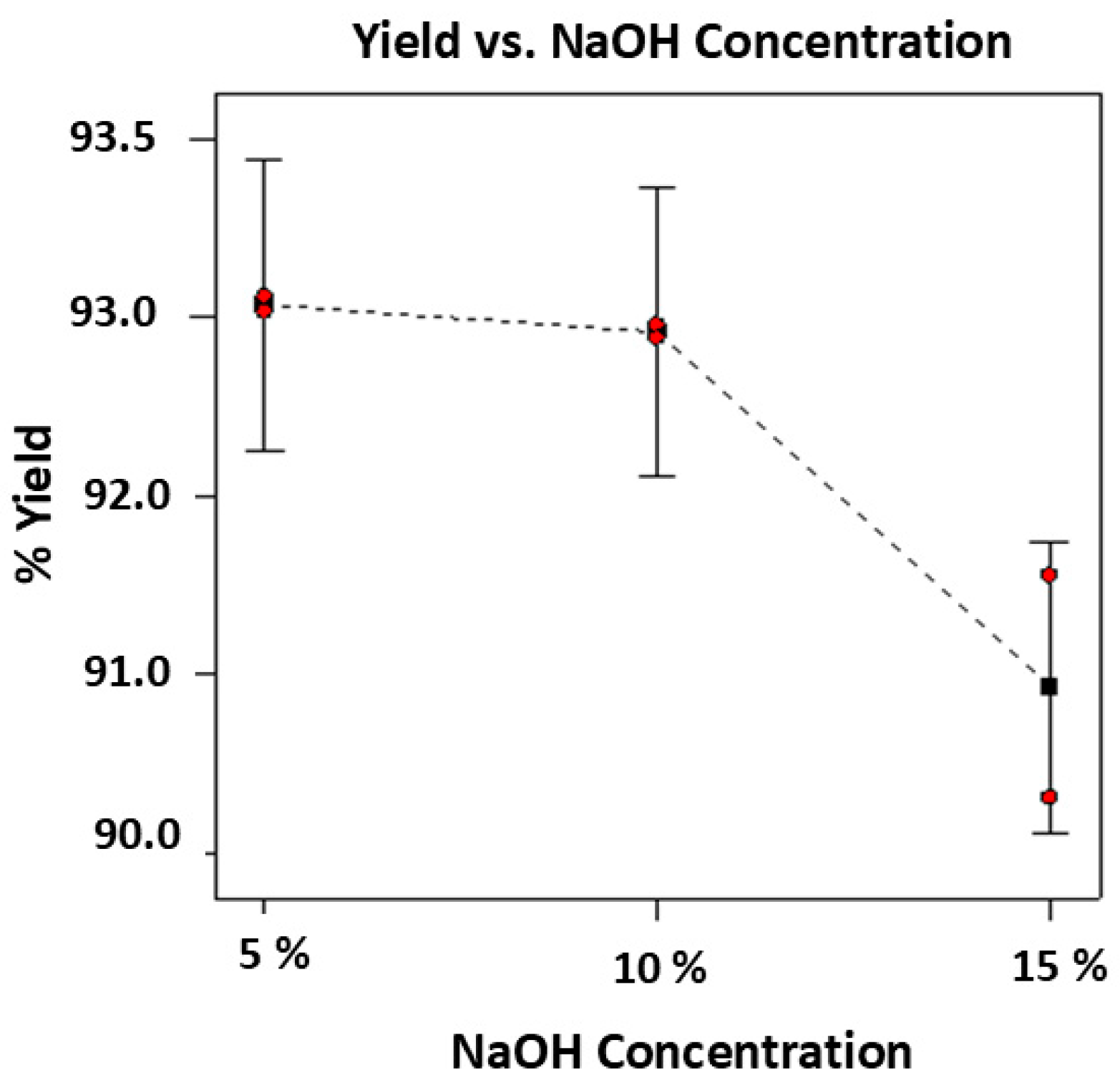

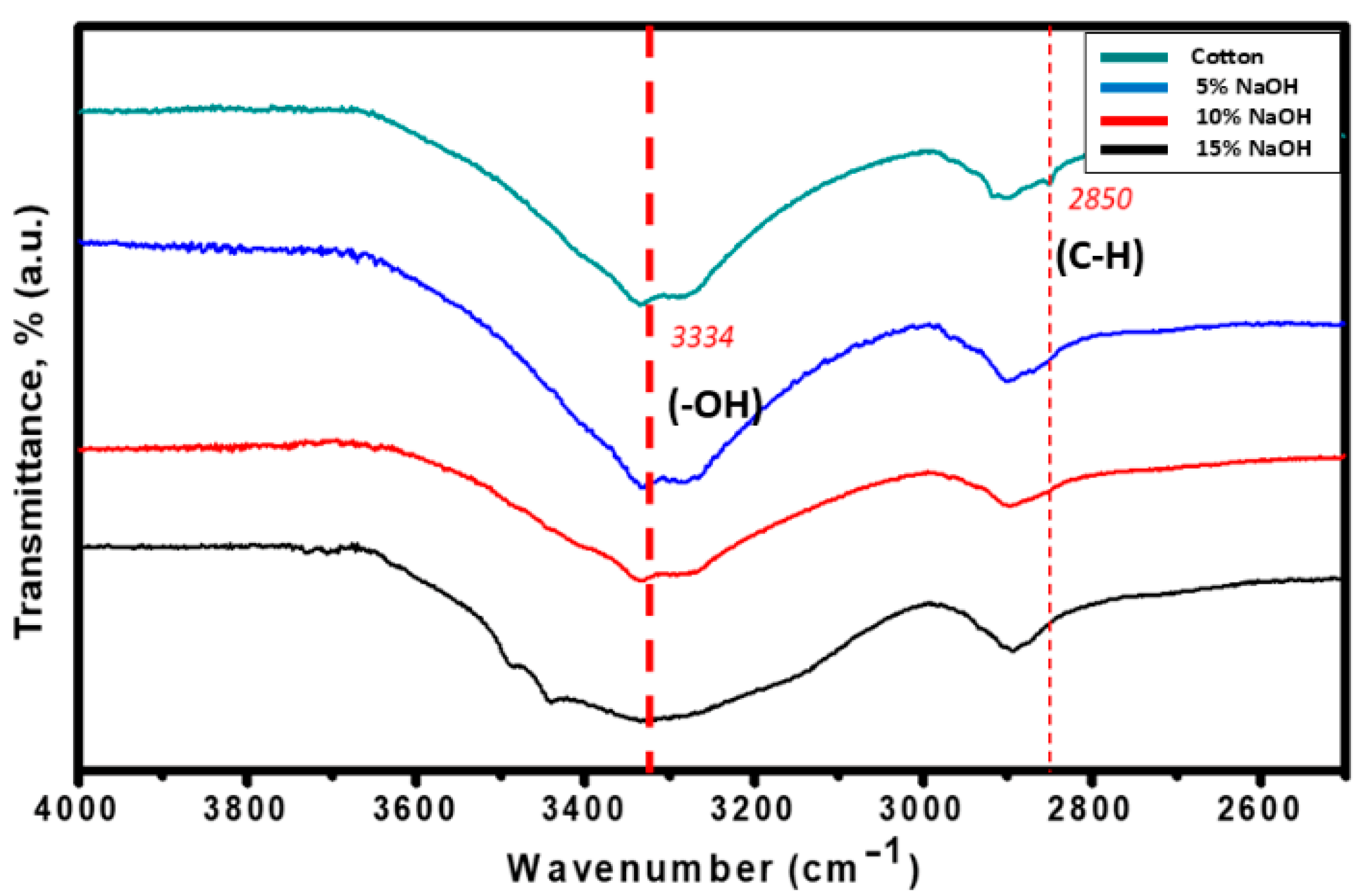

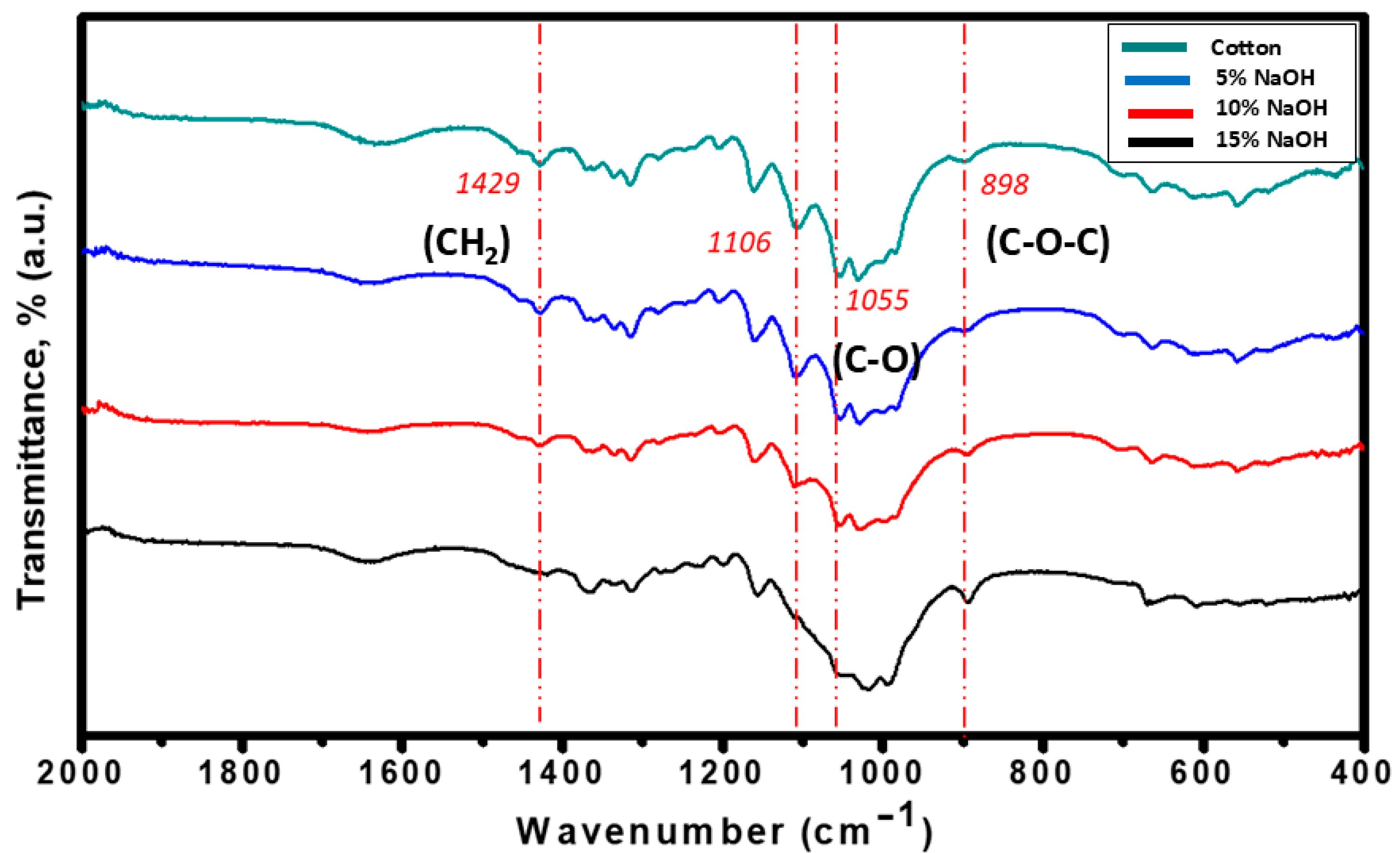

3.2. Effects of Alkali Treatment on Cellulose Recovery and Conversion

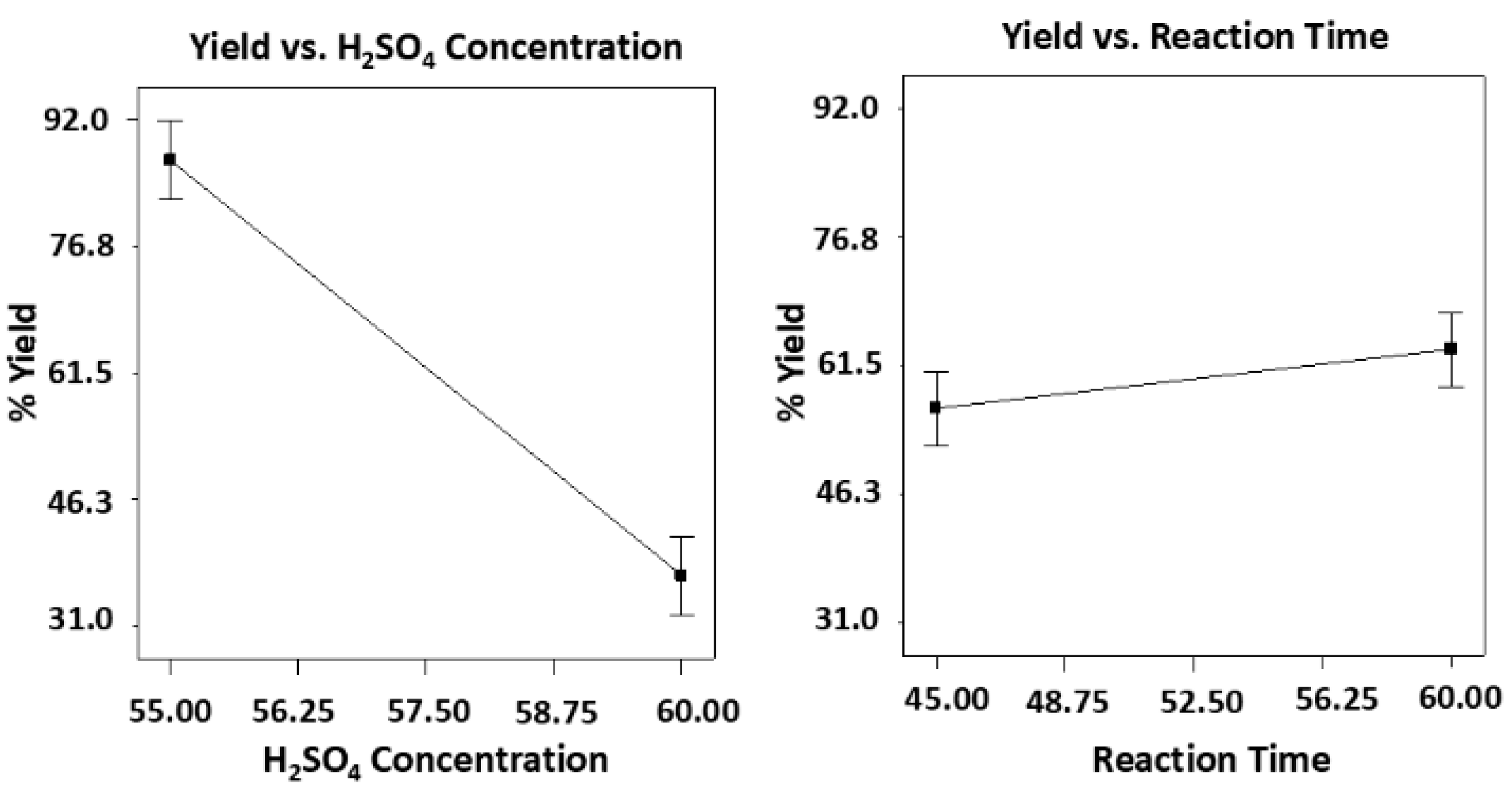

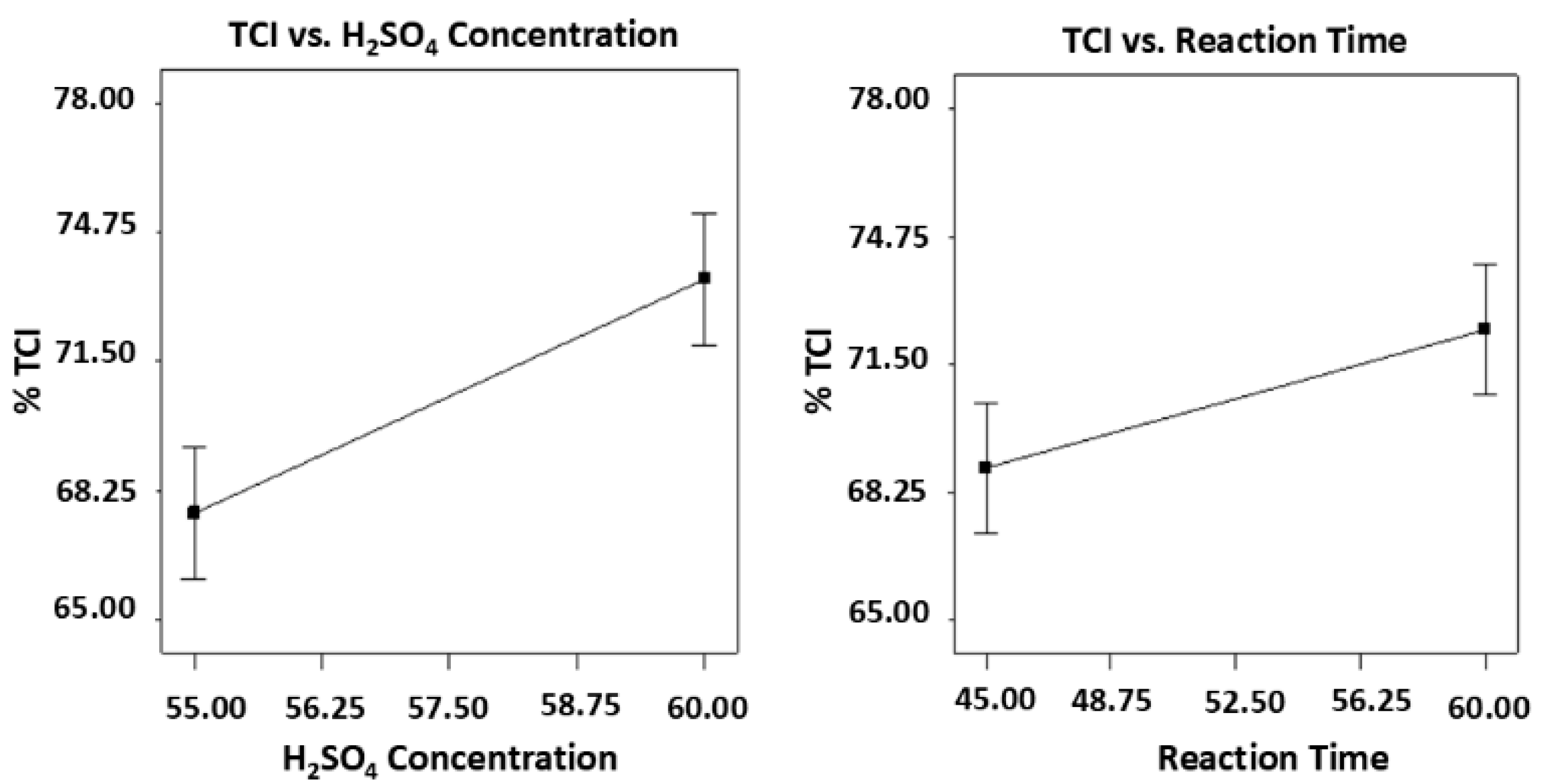

3.3. Effects of Acid Hydrolysis on Cellulose Whisker Conversion

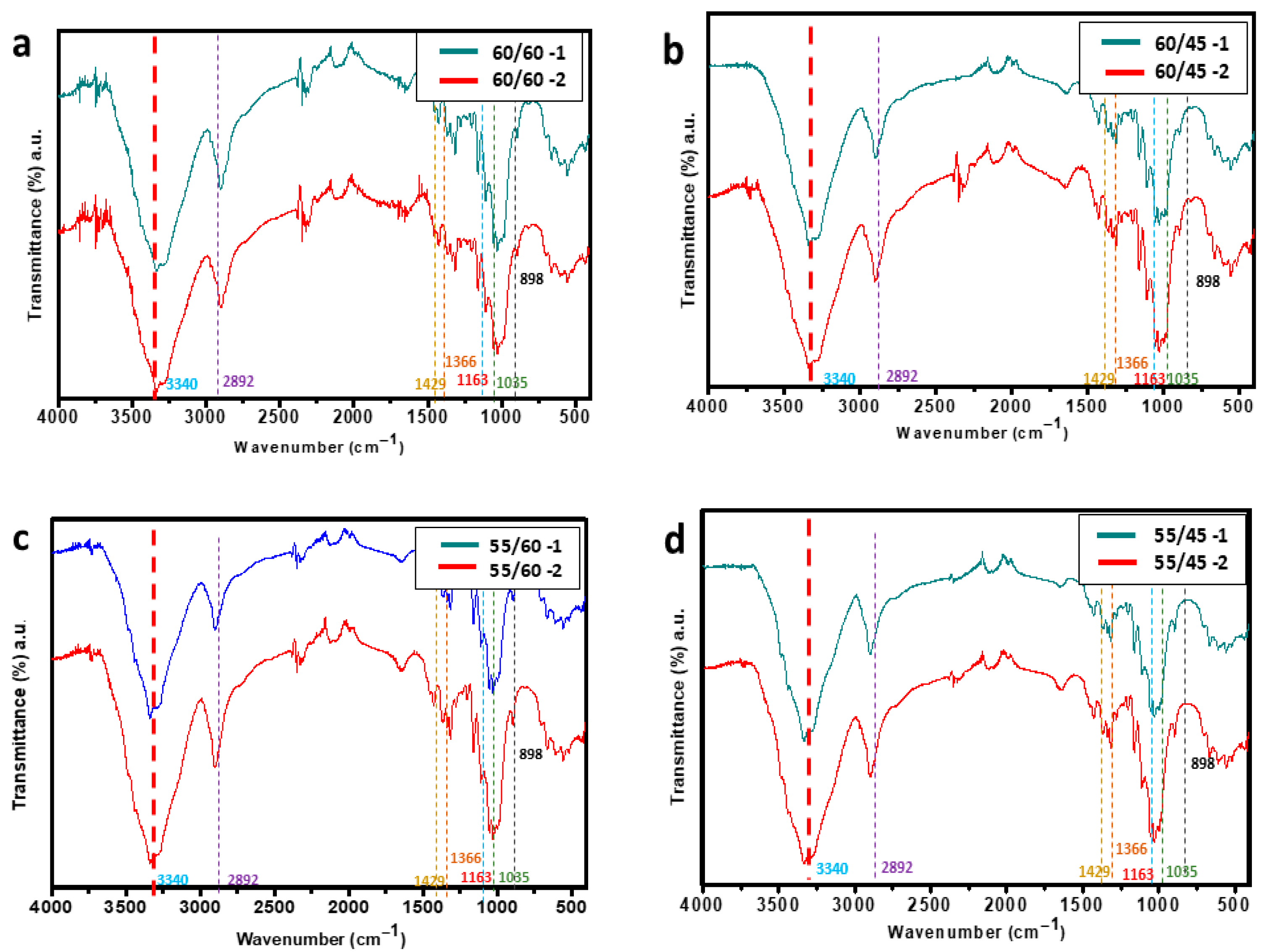

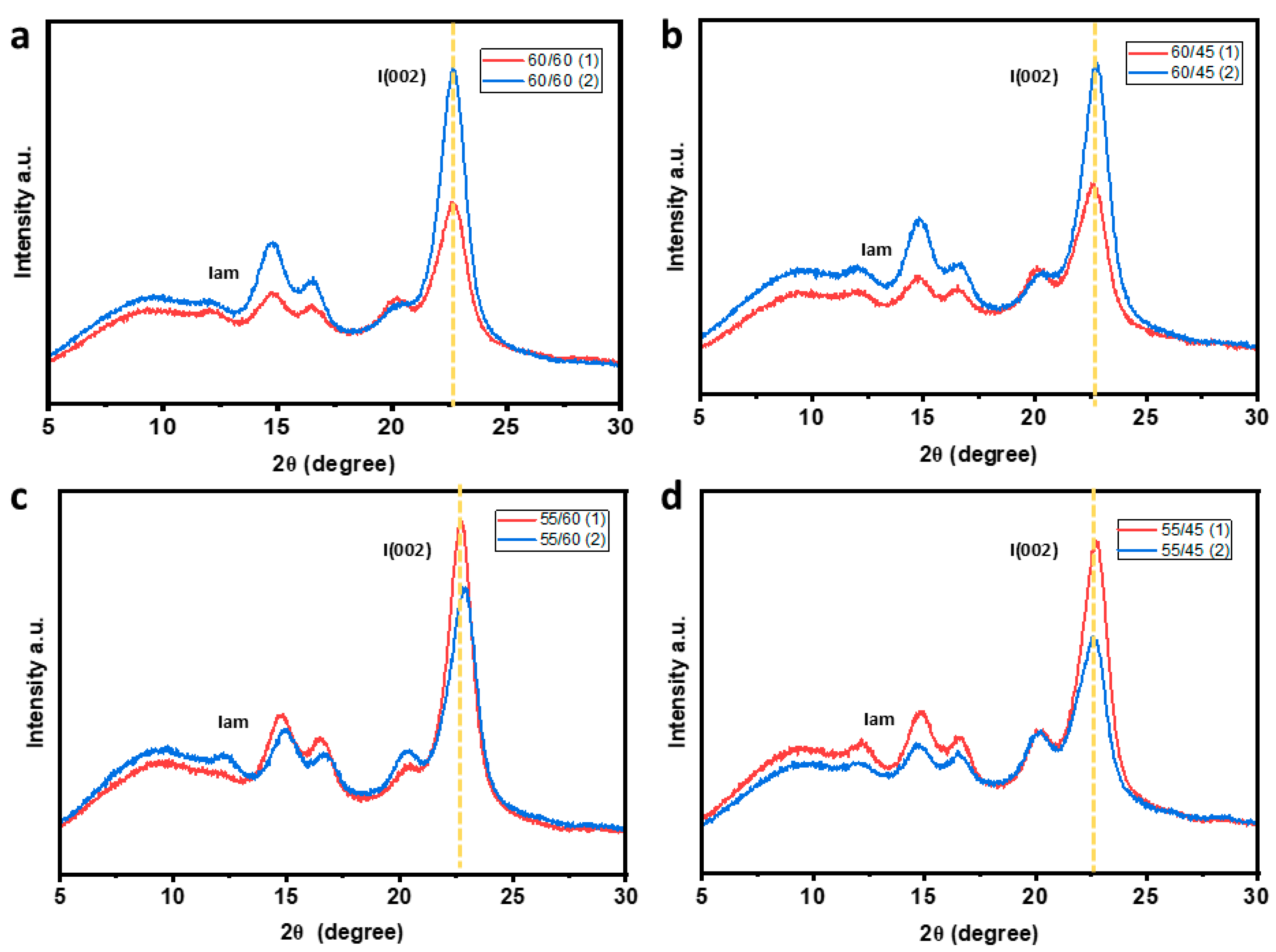

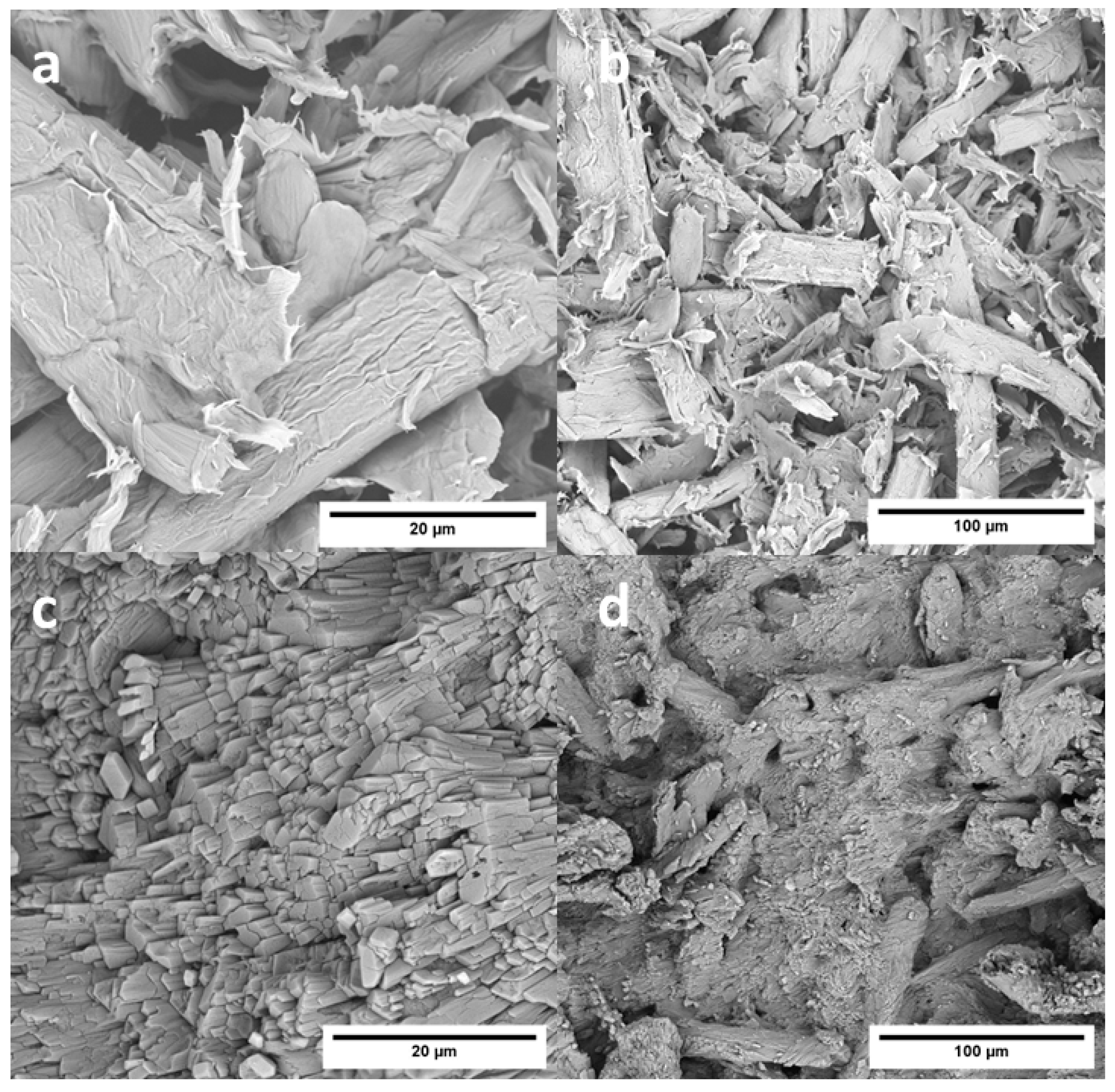

3.4. Effects of Acid Hydrolysis on Structural Composition of CWs

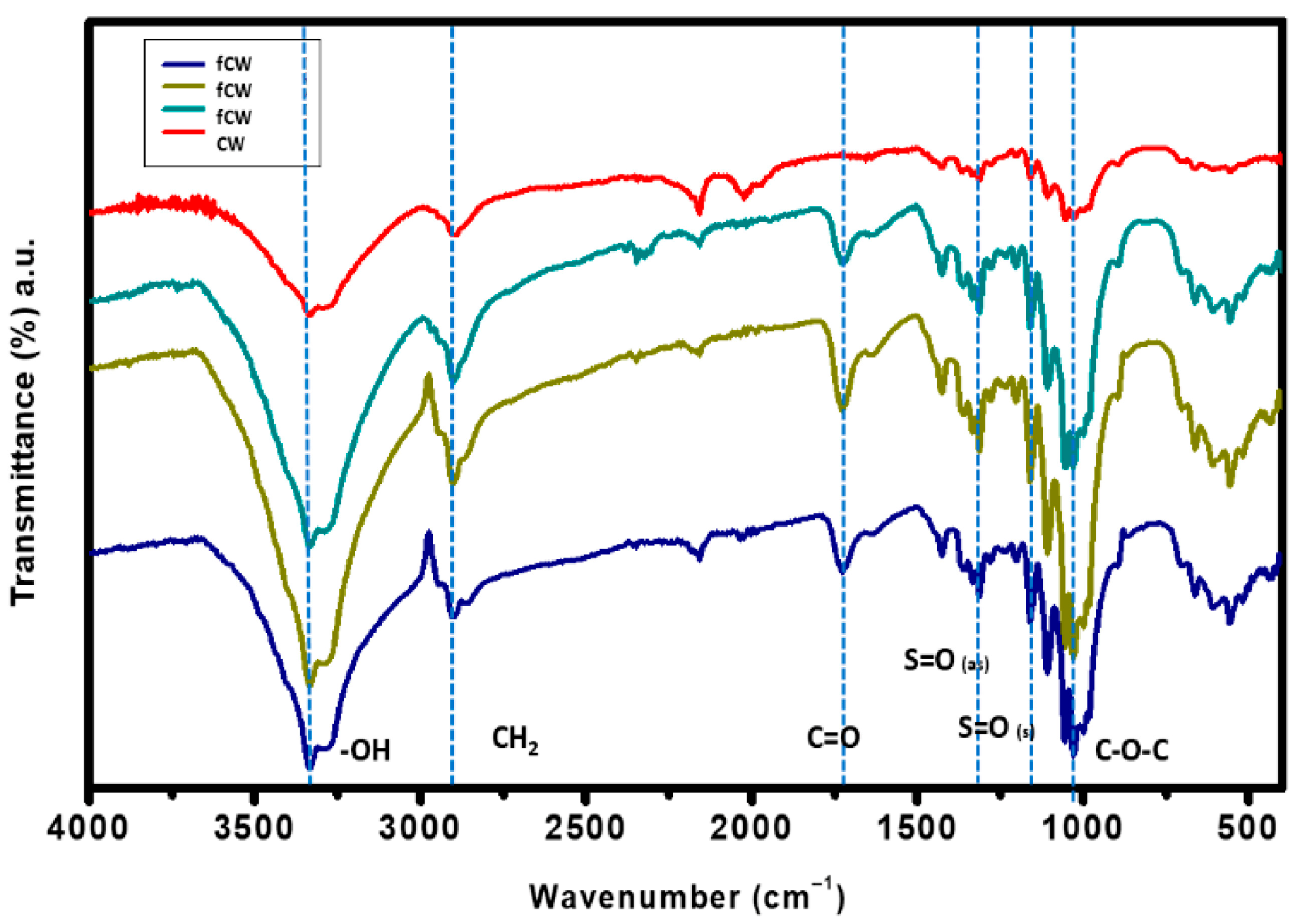

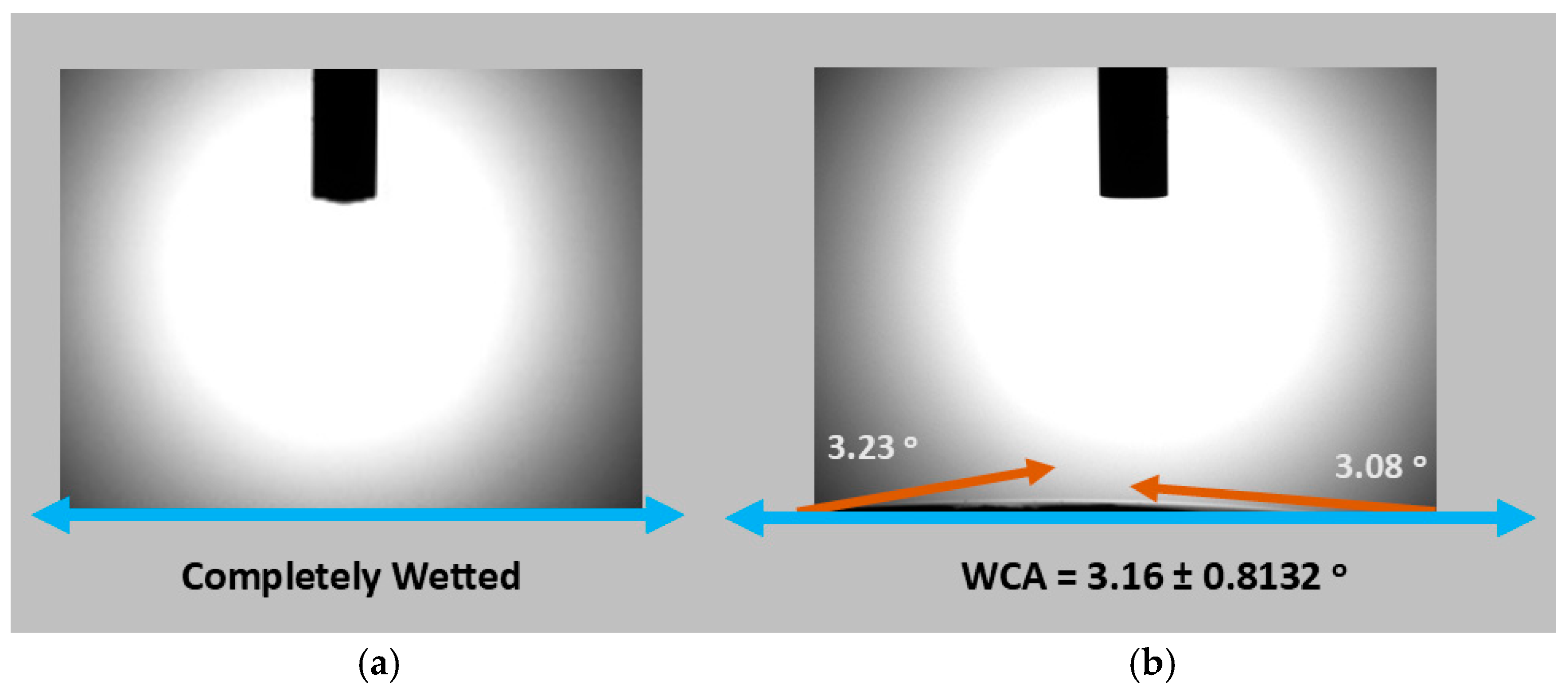

3.5. Effects of Functionalization on the Structure, Surface Wettability and Morphology of CWs

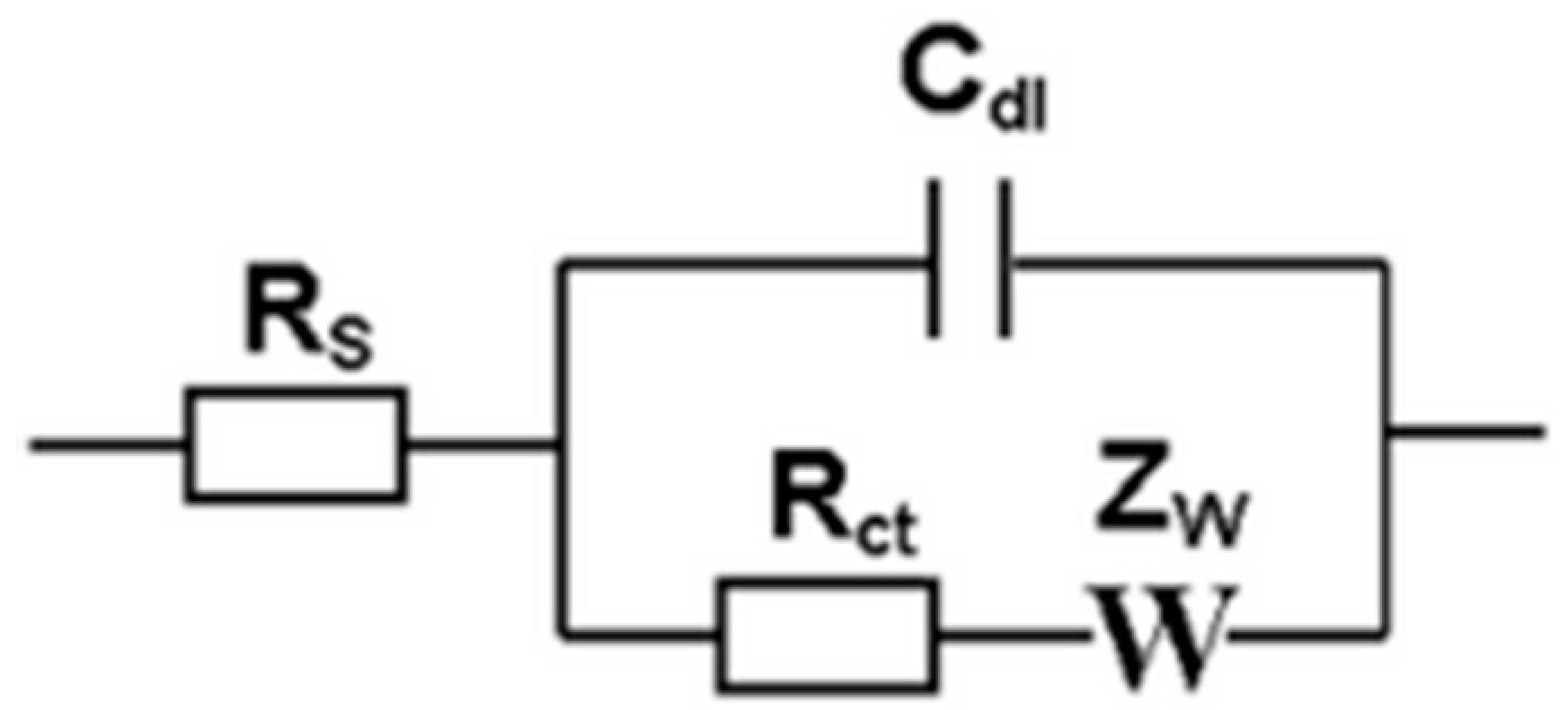

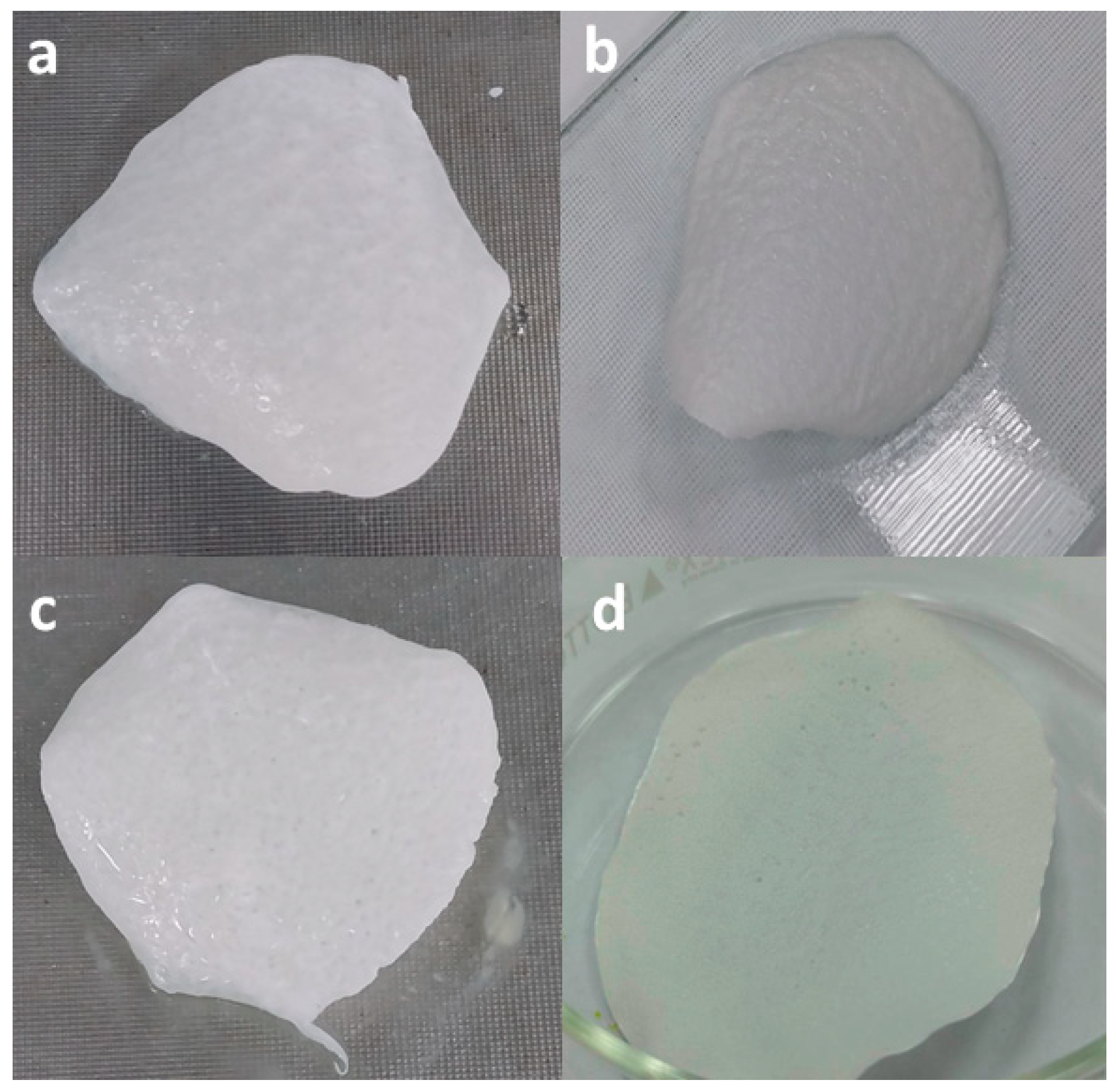

3.6. Electrochemical Capacity of Cellulose Whisker

3.7. Hybrid Membrane with Cellulose Whisker as Filler

4. Conclusions

5. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Philippot, M.; Alvarez, G.; Ayerbe, E.; Van Mierlo, J.; Messagie, M. Eco-Efficiency of a Lithium-Ion Battery for Electric Vehicles: Influence of Manufacturing Country and Commodity Prices on GHG Emissions and Costs. Batteries 2019, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allwood, J.M.; Cullen, J.M. Sustainable Materials: With Both Eyes Open; UIT Cambridge Ltd.: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Li, M.; Wang, Y. Biomass-derived carbon: Synthesis and applications in energy storage and conversion. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 4824–4854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuer, K.D. On the development of proton conducting polymer membranes for hydrogen and methanol fuel cells. J. Membr. Sci. 2001, 185, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, J.P.; Montalvo-Navarrete, J.M.; Hidalgo-Salazar, M.A. Carbon footprint considerations for biocomposite materials for sustainable products: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekomaya, O.; Jamiru, T.; Sadiku, R.; Huan, Z. A review on the sustainability of natural fiber in matrix reinforcement—A practical perspective. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2015, 35, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, H.R.; Woodard, A.C. Sustainability of engineered wood products. In Sustainability of Construction Materials; Woodhead Publishing: London, UK, 2016; pp. 159–180. [Google Scholar]

- D’AMato, D.; Gaio, M.; Semenzin, E. A review of LCA assessments of forest-based bioeconomy products and processes under an ecosystem services perspective. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 706, 135859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, R.D.; Puettmann, M.; Taylor, A.; Skog, K.E. The Carbon Impacts of Wood Products. For. Prod. J. 2014, 64, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaharuzaman, M.A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Mansor, M.R. Sustainable materials selection: Principles and applications. Des. Sustain. Green Mater. Process. 2021, 57–84. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, R.A. Green chemistry, catalysis and valorization of waste biomass. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2016, 422, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.H.; Matharu, A.S. Issues in Environmental Science and Technology: Waste as a Resource; Hester, R.E., Harrison, R.M., Eds.; Royal Society: London, UK, 2013; Volume 37, pp. 66–82. [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen, T.; Mussone, P.; Bressler, D. Valorization of rendering industry wastes and co-products for industrial chemicals, materials and energy: Review. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2016, 36, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, M.J.H.; Kucera, R.L.; Chalker, J.M. Green chemistry and polymers made from sulfur. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 3358–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, G.; Wang, S.; Yu, S.; Pan, F.; Wu, H.; Jiang, Z. Recent advances in the fabrication of advanced composite membranes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 10058–10077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, H.L.; Wahab, R.A. Towards an eco-friendly deconstruction of agro-industrial biomass and preparation of renewable cellulose nanomaterials: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 1414–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemm, D.; Heublein, B.; Fink, H.-P.; Bohn, A. Cellulose: Fascinating biopolymer and sustainable raw material. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 3358–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y.-J.; Cui, L.; Ignaszak, A.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, J. Research advances in biomass-derived nanostructured carbons and their composite materials for electrochemical energy technologies. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 118, 100770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, J.P.S.; Rosa, M.F.; Filho, M.M.S.; Nascimento, L.D.; Nascimento, D.M.; Cassales, A.R. Extraction and characterization of nanocellulose structures from raw cotton linter. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 91, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, G.X.; Takaffoli, M.; Hsieh, A.J.; Buehler, M.J. Biomimetic additive manufactured polymer composites for improved impact resistance. Extreme Mech. Lett. 2016, 9, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.; Kosoris, J.; Hong, L.N.; Crul, M. Design for Sustainability: Current Trends in Sustainable Product Design and Development. Sustainability 2009, 1, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Zhou, T.; Wang, Y.; Cao, X.; Wu, S.; Zhao, M.; Wang, H.; Xu, M.; Zheng, B.; Zheng, J.; et al. Pretreatment of wheat straw leads to structural changes and improved enzymatic hydrolysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, S.M.L.; Rehman, N.; de Miranda, M.I.G.; Nachtigall, S.M.B.; Bica, C.I.D. Chlorine-free extraction of cellulose from rice husk and whisker isolation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 87, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaaslan, M.A.; Tshabalala, M.A.; Yelle, D.J.; Buschle-Diller, G. Nanoreinforced biocompatible hydrogels from wood hemicelluloses and cellulose whiskers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 86, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendahou, A.; Habibi, Y.; Kaddami, H.; Dufresne, A. Physico-chemical characterization of palm from phoenix dactylifera–L, preparation of cellulose whiskers and natural rubber–based nanocomposites. J. Biobased Mater. Bioenergy 2009, 3, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kljun, A.T.W.M.; Benians, T.A.S.; Goubet, F.; Meulewaeter, F.; Knox, J.P.; Blackburn, R.S. Comparative analysis of crystallinity changes in cellulose I polymers using ATR-FTIR, X-ray diffraction, and carbohydrate-binding module probes. BioMacromolecules 2011, 12, 4121–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.Y.M.; Shao, P.; Burns, C.M.; Feng, X. Sulfonation of Poly (Ether Ether Ketone) (PEEK): Kinetic Study and Characterization. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001, 82, 2651–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, A.; Zeeman, G. Pretreatments to enhance the digestibility of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.Z.; Xie, G.H. Alkali-based pretreatments distinctively extract lignin and pectin for enhancing biomass saccharification by altering cellulose features in sugar-rich Jerusalem artichoke stem. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 208, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vârban, R.; Crișan, I.; Vârban, D.; Ona, A.; Olar, L.; Stoie, A.; Stefan, R. Comparative FTIR Prospecting for Cellulose in Stems of Some Fiber Plants: Flax, Velvet Leaf, Hemp and Jute. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciolacu, D.; Ciolacu, F.; Popa, V.I. Amorphous cellulose: Structure and characterization. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2011, 45, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Theivasanthi, T.; Christma, F.L.A.; Toyin, A.J.; Gopinath, S.C.B.; Ravichandran, R. Synthesis and characterization of cotton fiber-based nanocellulose. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 109, 832–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohomane, S.M.; Motloung, S.V.; Koao, L.F.; Motaung, T.E. Effects of Acid Hydrolysis on the Extraction of Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNCS): A Review. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2022, 56, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shailaja, A.K.; Ragini, B.P. Nanocellulose: Preparation, Characterization and Applications. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Q.; Wang, S.; Rials, T.G. Poly(vinyl alcohol) nanocomposites reinforced with cellulose fibrils isolated by high intensity ultrasonication. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2009, 40, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherzadeh, M.J.; Karimi, K. Enzyme-based hydrolysis processes for ethanol from lignocellulosic materials: A review. BioResources 2007, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Singh, B.; Korstad, J. Utilization of lignocellulosic biomass by oleaginous yeast and bacteria for production of biodiesel and renewable diesel. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 73, 654–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, T.; Dhandapani, R.; Liang, D.; Wang, J.; Wolcott, M.P.; Van Fossen, D.; Liu, H. Nanocellulose from recycled indigo-dyed denim fabric and its application in composite films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 240, 116283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvério, H.A.; Neto, W.P.F.; Dantas, N.O.; Pasquini, D. Extraction and characterization of cellulose nanocrystals from corncob for application as reinforcing agent in nanocomposites. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013, 44, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, Y.; Lucia, L.A.; Rojas, O.J. Cellulose nanocrystals: Chemistry, self-assembly, and applications. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 3479–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob, M.; Mahendran, A.R.; Gindl-Altmutter, W.; Bliem, P.; Konnerth, J.; Müller, U.; Veigel, S. The strength and stiffness of oriented wood and cellulose-fibre materials: A review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumita, M.; Sakata, K.; Asai, S.; Miyasaka, K.; Nakagawa, H. Dispersion of fillers and the electrical conductivity of polymer blends filled with carbon black. Polym. Bull. 1991, 25, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaari, N.; Kamarudin, S.K. Recent advances in additive-enhanced polymer electrolyte membrane properties in fuel cell applications: An overview. Int. J. Energy Res. 2019, 43, 2756–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Hsieh, Y.-L. Preparation and properties of cellulose nanocrystals: Rods, spheres, and network. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 82, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Shi, S.Q.; Barnes, H.M.; Pittman, J.C.U. A chemical process for preparing cellulosic fibers hierarchically from kenaf bast fibers. BioResources 2011, 6, 879–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagaito, A.N.; Fujimura, A.; Sakai, T.; Hama, Y.; Yano, H. Production of microfibrillated cellulose (MFC)-reinforced polylactic acid (PLA) nanocomposites from sheets obtained by a papermaking-like process. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2009, 69, 1293–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samir, M.A.S.A.; Alloin, F.; Sanchez, J.-Y.; Dufresne, A. Cross-Linked Nanocomposite Polymer Electrolytes Reinforced with Cellulose Whiskers. Macromolecules 2004, 37, 4839–4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selyanchyn, O.; Bayer, T.; Klotz, D.; Selyanchyn, R.; Sasaki, K.; Lyth, S.M. Cellulose Nanocrystals Crosslinked with Sulfosuccinic Acid as Sustainable Proton Exchange Membranes for Electrochemical Energy Applications. Membranes 2022, 12, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, L.; Mathew, A.; Oksman, K.; Gatenholm, P.; Ragauskas, A.J. A novel nanocomposite film prepared from crosslinked cellulosic whiskers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 75, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-U.; Kim, J.-Y. Monte Carlo Investigation of Orientation-Dependent Percolation Networks in Carbon Nanotube-Based Conductive Polymer Composites. Physchem 2025, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Teramoto, Y.; Endo, T. Cellulose nanofiber-reinforced polycaprolactone/polypropylene hybrid nanocomposite. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2011, 42, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, X.L.; Li, C.Y.; Liang, M.; Lua, C.H.; Deng, Y.L. Mechanochemical activation of cellulose and its thermoplastic polyvinyl alcohol ecocomposites with enhanced physicochemical properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 83, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.A.; Huque, M.M.; Islam, M.R.; Bledzki, A.K. Mechanical properties of jute fiber reinforced polypropylene composite: Effect of chemical treatment by benzenediazonium salt in alkaline medium. BioResources 2009, 5, 1618–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, S.; Guha, P. A Review on Preparation and Properties of Cellulose Nanocrystal-Incorporated Natural Biopolymer. J. Packag. Technol. Res. 2018, 2, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Independent Variable/Factor | Levels | Dependent Variables/Responses | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Mid | High | ||

| NaOH Concentration, wt% | 5 | 10 | 15 | Yield, ATR-FTIR |

| Independent Variables/Factors | Levels | Dependent Variables/ Responses | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||

| H2SO4 Concentration, wt% | 55 | 60 | Yield, TCI, ATR-FTIR |

| Reaction Time, min | 45 | 60 | |

| Biomass Material | Composition | Cellulose, % | Lignin, % | Moisture, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coconut Fiber |  | 43.4 | 45.8 | 10.8 |

| Saw Dust |  | 54.3 | 35.8 | 9.9 |

| Cotton Lint |  | 79.6 | - | 20.4 |

| Cotton Linter * |  | 96.5 | - | 3.5 |

| Cotton Linter ** |  | 94.9 | - | 5.1 |

| Cotton Linter * |  | 95.5 | - | 4.5 |

| Sample | CrI, % | TCI, % | Std Dev |

|---|---|---|---|

| 60/60 | 72.4 | 75.6 | 2.2 |

| 55/60 | 69.5 | 69.1 | 0.2 |

| 60/45 | 70.9 | 71.5 | 0.4 |

| 55/45 | 70.0 | 65.9 | 2.9 |

| CW Sample | IEC, meq/g |

|---|---|

| Average | |

| CW 1 | 1.78 ± 0.0354 |

| CW 2 | 1.68 ± 0.0919 |

| CW 3 | 1.51 ± 0.1273 |

| Tensile Strenght, Mpa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filler Loading, % | 0 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| Replicate 1 | 13.36 | 14.32 | 14.37 | 10.60 |

| Replicate 2 | 13.61 | 13.13 | 13.15 | 8.05 |

| Average | 13.5 | 13.7 | 13.8 | 9.3 |

| Membrane | Resistance (Ω) | Conductivity (S/cm) | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure PSU | 4.51 | 0.0173 | - |

| 3% fCW/PSU | 5.60 | 0.0182 | 5.2 |

| 5% fCW/PSU | 4.80 | 0.0192 | 10.9 |

| 8% fCW/PSU | 3.71 | 0.0189 | 9.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Parreño, R.P., Jr.; Badua, R.A., Jr.; Rama, J.L.; Bawagan, A.V.O. Facile Synthesis of Cellulose Whisker from Cotton Linter as Filler for the Polymer Electrolyte Membrane (PEM) of Fuel Cells. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 670. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120670

Parreño RP Jr., Badua RA Jr., Rama JL, Bawagan AVO. Facile Synthesis of Cellulose Whisker from Cotton Linter as Filler for the Polymer Electrolyte Membrane (PEM) of Fuel Cells. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):670. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120670

Chicago/Turabian StyleParreño, Ronaldo P., Jr., Reynaldo A. Badua, Jr., Jowin L. Rama, and Apollo Victor O. Bawagan. 2025. "Facile Synthesis of Cellulose Whisker from Cotton Linter as Filler for the Polymer Electrolyte Membrane (PEM) of Fuel Cells" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 670. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120670

APA StyleParreño, R. P., Jr., Badua, R. A., Jr., Rama, J. L., & Bawagan, A. V. O. (2025). Facile Synthesis of Cellulose Whisker from Cotton Linter as Filler for the Polymer Electrolyte Membrane (PEM) of Fuel Cells. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 670. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120670