Evaluation of Sasa kurilensis Biomass-Derived Hard Carbon as a Promising Anode Material for Sodium-Ion Batteries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials Synthesis

2.2. Physicochemical Methods

2.3. Electrochemical Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Obtained Materials

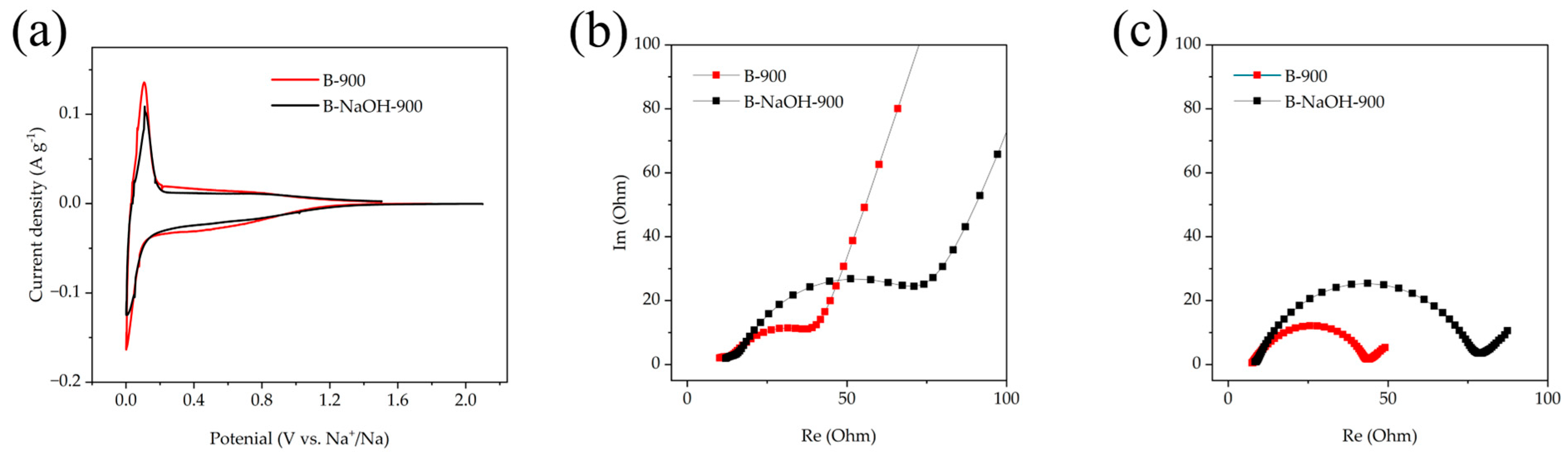

3.2. Electrochemical Performance of the Investigated Materials

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tian, Y.; Zeng, G.; Rutt, A.; Shi, T.; Kim, H.; Wang, J.; Koettgen, J.; Sun, Y.; Ouyang, B.; Chen, T.; et al. Promises and Challenges of Next-Generation “Beyond Li-Ion” Batteries for Electric Vehicles and Grid Decarbonization. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1623–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Hu, Z.; Li, W.; Zou, C.; Jin, H.; Wang, S.; Chou, S.; Dou, S.-X. Sodium Transition Metal Oxides: The Preferred Cathode Choice for Future Sodium-Ion Batteries? Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 158–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Pan, Z.; Sun, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J. High-Energy Batteries: Beyond Lithium-Ion and Their Long Road to Commercialisation. Nano Micro Lett. 2022, 14, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yuan, H.; Liu, H.; Zhao, C.; Lu, Y.; Cheng, X.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Q. Unlocking the Failure Mechanism of Solid State Lithium Metal Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2100748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Li, G.; Duan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, X.; Luo, M.; Liu, Y. The Research and Industrialization Progress and Prospects of Sodium Ion Battery. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 958, 170486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Zhou, Q.; Ma, M.; Liu, H.K.; Dou, S.X.; Chong, S. Advanced Anode Materials for Rechargeable Sodium-Ion Batteries. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 11220–11252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Lan, X.; Hu, R.; Yao, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, M. Tin-Based Anode Materials for Stable Sodium Storage: Progress and Perspective. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2106895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Ouyang, B.; Fan, X.; Zhou, W.; Liu, W.; Liu, K. Oxide Cathodes for Sodium-ion Batteries: Designs, Challenges, and Perspectives. Carbon Energy 2022, 4, 170–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, J.; Xu, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhou, J.; Gao, F.; Tang, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z.; et al. Fe2VO4 Nanoparticles on RGO as Anode Material for High-Rate and Durable Lithium and Sodium Ion Batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chang, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Gu, M.; Huang, H.; Tang, L.; Zhong, Y.; Xia, H. Interface Modulation of Metal Sulfide Anodes for Long-Cycle-Life Sodium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2208705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; He, Y.; Dai, Y.; Ren, Y.; Gao, T.; Zhou, G. Bimetallic SnS2/NiS2@S-RGO Nanocomposite with Hierarchical Flower-like Architecture for Superior High Rate and Ultra-Stable Half/Full Sodium-Ion Batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 131784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Sun, Z.; Nie, P.; Yu, H.; Zhao, C.; Yu, M.; Luo, Z.; Geng, H.; Wu, X. SbPS4: A Novel Anode for High-Performance Sodium-Ion Batteries. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 470–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, H.; Huang, W.; He, X.; Chen, Q.; Dong, H.; Li, L.; Wu, X.; et al. Industrial-Scale Hard Carbon Designed to Regulate Electrochemical Polarization for Fast Sodium Storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202406889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Wang, H.; Zhou, S.; Pan, Z.; Huang, Y.; Sun, D.; Tang, Y.; Ji, X.; Amine, K.; et al. Revealing the Closed Pore Formation of Waste Wood-Derived Hard Carbon for Advanced Sodium-Ion Battery. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Vasileiadis, A.; Zhou, Q.; Lu, Y.; Meng, Q.; Li, Y.; Ombrini, P.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Z.; Niu, Y.; et al. Origin of Fast Charging in Hard Carbon Anodes. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Zheng, L.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wu, F.; Wu, C.; Bai, Y. Unlocking the Local Structure of Hard Carbon to Grasp Sodium-Ion Diffusion Behavior for Advanced Sodium-Ion Batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, J.; Guo, Z.; Xie, F.; Liu, H.; Yadegari, H.; Tebyetekerwa, M.; Ryan, M.P.; Hu, Y.; Titirici, M. The Role of Hydrothermal Carbonization in Sustainable Sodium-Ion Battery Anodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2200208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Hu, S.; Yin, W.; Peng, J.; Wang, R.; Jin, J.; He, B.; Gong, Y.; Wang, H.; Fan, H.J. CO2-Etching Creates Abundant Closed Pores in Hard Carbon for High-Plateau-Capacity Sodium Storage. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2303064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Le, P.M.L.; Gao, P.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, B.; Engelhard, M.H.; Cao, X.; Vo, T.D.; Hu, J.; Zhong, L.; et al. Low-Solvation Electrolytes for High-Voltage Sodium-Ion Batteries. Nat. Energy 2022, 7, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobyleva, Z.V.; Drozhzhin, O.A.; Alekseeva, A.M.; Dosaev, K.A.; Peters, G.S.; Lakienko, G.P.; Perfilyeva, T.I.; Sobolev, N.A.; Maslakov, K.I.; Savilov, S.V.; et al. Caramelization as a Key Stage for the Preparation of Monolithic Hard Carbon with Advanced Performance in Sodium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2023, 6, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, X.; Lou, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, J.; Qiu, Y.; Wu, T.; Zhong, S.; Wang, H.; Wu, L. Carbon Nanofibers Derived from Carbonization of Electrospinning Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) as High Performance Anode Material for Lithium Ion Batteries. J. Porous Mater. 2023, 30, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Zhang, R.; Luo, X.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, W.; Liu, J.; Liu, J. Epoxy Phenol Novolac Resin: A Novel Precursor to Construct High Performance Hard Carbon Anode toward Enhanced Sodium-Ion Batteries. Carbon 2023, 205, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfattani, R.; Shah, M.A.; Siddiqui, M.I.H.; Ali, M.A.; Alnaser, I.A. Bio-Char Characterization Produced from Walnut Shell Biomass through Slow Pyrolysis: Sustainable for Soil Amendment and an Alternate Bio-Fuel. Energies 2021, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Zheng, J.; Que, L.; Yu, F.; Zhao, J.; Xie, Y.; Huang, M.; Lu, C.; et al. Tea-Derived Sustainable Materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2310226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, X.; Xia, Y. Regulation of Surface Oxygen Functional Groups and Pore Structure of Bamboo-Derived Hard Carbon for Enhanced Sodium Storage Performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muruganantham, R.; Wang, F.-M.; Liu, W.-R. A Green Route N, S-Doped Hard Carbon Derived from Fruit-Peel Biomass Waste as an Anode Material for Rechargeable Sodium-Ion Storage Applications. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 424, 140573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, L.; Wan, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, H. The Effect of Thermal Treatment Temperature on the Crystal Structure and Electrochemical Performance of the Coconut Shell-Based Hard Carbon. Solid State Ion. 2023, 402, 116374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thenappan, M.; Rengapillai, S.; Marimuthu, S. Hard Carbon Reprising Porous Morphology Derived from Coconut Sheath for Sodium-Ion Battery. Energies 2022, 15, 8086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.-M.; Zheng, H.; Yuan, P.; Luo, J.-H.; Shen, L.-L.; Tan, J.-F.; Luo, X.-Y.; Li, D.; Chen, Y. Structural Engineering of Hard Carbon through Spark Plasma Sintering for Enhanced Sodium-Ion Storage. Rare Met. 2024, 43, 4274–4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itabashi, T.; Akada, S.; Ishida, K.; Ishibashi, S.; Ohno, M.; Matsui, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Nakashizuka, T.; Makita, A. Culm Dynamics of Dwarf Bamboo (Sasa kurilensis Makino & Shibata) in Relation to Forest Canopy Conditions in Beech Forests. Adv. Bamboo Sci. 2023, 2, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, S.; Takeuchi, K.; Takagi, K.; Shibata, M. Stimulatry Effect of the Water Extract of Bamboo Grass (Folin Solution) on Gastric Acid Secretion in Pylorus-Ligated Rats. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1975, 25, 608–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.-F.; Liang, C.-F.; Chen, J.-H.; Li, Y.-C.; Qin, H.; Fuhrmann, J.J. Rapid Bamboo Invasion (Expansion) and Its Effects on Biodiversity and Soil Processes +. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 21, e00787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, A.; Luxová, M.; Abe, J.; Morita, S.; Inanaga, S. Silicification of Bamboo (Phyllostachys heterocycla Mitf.) Root and Leaf. Plant Soil 2003, 255, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Sun, Y.; He, Z.; Dai, G.; Ru, B.; Qiu, P.; Wang, S. Effect of Pore Structure Regulation in Coconut Shell-Derived Hard Carbon on Sodium Storage Capacity. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 538, 147046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Sun, N.; Zhu, Q.; Soomro, R.A.; Xu, B. Microcrystalline Hybridization Enhanced Coal-Based Carbon Anode for Advanced Sodium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2200023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangfu, J.; Cao, H.; Xi, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Kong, F. Low-Temperature Pre-Oxidation and High-Temperature Activation Modulate Brewer’s Spent Grains-Based Hard Carbon Microcrystalline Structure to Enhance Sodium Storage Properties. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 233, 121413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarramsetti, S.; Kalluri, S.; Ch, S.; Uv, V. Catalytic Graphitisation of Vigna Mungo (L) Hepper Biomass: A Renewable Graphite Source for High-Performance Energy Storage Applications. J. Energy Storage 2025, 134, 118211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultman, L.; Cziga, Z. Ultramicroscopy Interpretation of Electron Diffraction Patterns from Amorphous and Fullerene-like Carbon Allotropes. Ultramicroscopy 2010, 110, 815–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Zhu, Z.; Han, S.; Wang, N.; Tiwari, S.K. Advances in Hard Carbon: From Structural Complexity to Applications for next-Generation Technologies. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1042, 183755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Shang, L.; Ma, X.; Fang, C.; Fei, B.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S. Three-Dimensional Structural Characterization and Mechanical Properties of Bamboo Parenchyma Tissue. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 208, 117833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palombini, F.L.; Kindlein, W.; de Oliveira, B.F.; de Araujo Mariath, J.E. Bionics and Design: 3D Microstructural Characterization and Numerical Analysis of Bamboo Based on X-Ray Microtomography. Mater. Charact. 2016, 120, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Shao, Z. Study on the Variation Law of Bamboo Fibers’ Tensile Properties and the Organization Structure on the Radial Direction of Bamboo Stem. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 152, 112521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Gu, S.; Huang, A.; Cheng, H. Effects of Alkali Treatment on the Bending and Fracture Behavior of Biomaterial Bamboo. Polym. Test. 2025, 143, 108715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Luo, X.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Liu, Z.; Dai, C.; Miao, H.; Liu, H. Bamboo as a Naturally-Optimized Fiber-Reinforced Composite: Interfacial Mechanical Properties and Failure Mechanisms. Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 279, 111458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väli, R.; Jänes, A.; Lust, E. Alkali-Metal Insertion Processes on Nanospheric Hard Carbon Electrodes: An Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Study. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, E3429–E3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Hussain, H.; Ali, M.; Aman, S.; Yang, W.; Ali, Z.; Li, L.; Jiang, Y.; Yousaf, M. Regulating a NaF-Rich SEI Layer for Dendrite-Free Sodium Metal Batteries Using Trifunctional Halogenated Covalent Organic Framework Separators. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e03693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Chishti, A.N.; Ali, M.; Iqbal, S.; Aman, S.; Mahmood, A.; Liu, H.; Yousaf, M.; Jiang, Y. Recent Development in Sodium Metal Batteries: Challenges, Progress, and Perspective. Mater. Today 2025, 88, 730–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Iqbal, S.; Chishti, A.N.; Ali, M.; Aman, S.; Hussain, H.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, X.; Yousaf, M. A Multifunctional Ex-Situ Artificial Hybrid Interphase Layer to Stabilize Sodium Metal Anode. Nano Energy 2024, 132, 110348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Iqbal, S.; Ali, M.; Aman, S.; Chishti, A.N.; Zhang, J.; Shen, Z.; Huang, H.; Yousaf, M.; Jiang, Y. Tailoring the NaI-Rich Solid Electrolyte Interphase for Enhanced Stability in Sodium Metal Batteries. J. Power Sources 2025, 640, 236733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Zhao, R.; Huang, Z.; Cui, C.; Wang, F.; Gu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, T. Vascular Tissue-Derived Hard Carbon with Ultra-High Rate Capability for Sodium-Ion Storage. Carbon 2024, 224, 118955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Chishti, A.N.; Ali, M.; Rehman, J.; Zaman, F.; Luo, T.; Ali, M.; Aman, S.; Hussain, H.; Huang, H.; et al. Introduction of a Multifunctional Percolated Framework into Na Metal for Highly Stable Sodium Metal Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 14982–14994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, S.; Iqbal, S.; Chishti, A.N.; Ali, M.; Ali, M.; Hussain, H.; Huang, H.; Lin, Y.; Yousaf, M.; Jiang, Y. A Multifunctional Na2Se/Zn-Mn Skeleton Enables Processable and Highly Reversible Sodium Metal Anode. Small 2025, 21, 2407682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kydyrbayeva, U.; Baltash, Y.; Mukhan, O.; Nurpeissova, A.; Kim, S.-S.; Bakenov, Z.; Mukanova, A. The Buckwheat-Derived Hard Carbon as an Anode Material for Sodium-Ion Energy Storage System. J. Energy Storage 2024, 96, 112629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, K.; Cao, D. Preparation of Mesoporous Hard Carbon Anode Materials by Nitrogen Doping of Biomass to Enhance the Specific Capacity of Sodium Ion Adsorption. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2025, 991, 119190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra Rios, C.d.M.; Simone, V.; Simonin, L.; Martinet, S.; Dupont, C. Biochars from Various Biomass Types as Precursors for Hard Carbon Anodes in Sodium-Ion Batteries. Biomass Bioenergy 2018, 117, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Hua, Z.; Yang, J.; Hu, H.; Zheng, J.; Ma, X.; Lin, J.; Cao, S. Bamboo—A Potential Lignocellulosic Biomass for Preparation of Hard Carbon Anode Used in Sodium Ion Battery. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 194, 107673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Bao, R.; Kong, X.; Liu, L.; Deng, Z.; Yi, J. Resin Derived Carbon Coating Enhances Closed Pore Architecture in Coffee Silver Skin Hard Carbon for Advanced Sodium Ion Storage. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 727, 138183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Xue, Z.; Ding, Y. Bamboo Waste Derived Hard Carbon as High Performance Anode for Sodium-Ion Batteries. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 150, 111737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Yuan, R.; Shang, L.; Liu, T.; Wang, W.; Miao, Y.; Chen, X.; Song, H. Potato-Starch-Based Hard Carbon Microspheres: Preparation and Application as an Anode Material for Sodium-Ion Batteries. Solid State Ion. 2024, 406, 116475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Han, C.; Dai, Y.; Li, M.; Wu, Z.; Gao, X. Biomass Derived Hard Carbon Materials for Sodium Ion Battery Anodes: Exploring the Influence of Carbon Source on Structure and Sodium Storage Performance. Fuel 2024, 371, 132141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chen, B.; Hu, B.; Gu, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Sha, D.; Zhang, J.; Huang, S. 3D Connected Porous Structure Hard Carbon Derived from Paulownia Xylem for High Rate Performance Sodium Ion Battery Anode. J. Energy Storage 2024, 81, 110306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Chishti, A.N.; Ali, M.; Ali, M.; Hao, Y.; Wu, X.; Huang, H.; Lu, W.; Gao, P.; Yousaf, M.; et al. Se-p Orbitals Induced “Strong d–d Orbitals Interaction” Enable High Reversibility of Se-Rich ZnSe/MnSe@C Electrode as Excellent Host for Sodium-Ion Storage. Small 2024, 20, e2308262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Precursor | Sample | Temperature (°C) | d002, nm | SBET, m2 g−1 | Capacity, mAhg−1 | ICE, % | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bamboo | HC-900 HC-1100 HC-1300 HC-1500 HC-1700 | 900–1700 | 0.392 0.387 0.385 0.371 0.370 | 519.5972 35.6296 13.0375 3.7649 3.6883 | 237.5 266.1 348.5 310.0 314.5 | 68.2 72.7 84.1 85.6 87.6 | [25] |

| Mango peels | MPC NS-MPC | 1000 | 0.38 0.48 | 1079.88 408.99 | 280 350 | 40.05 52.03 | [26] |

| Coconut shell | HC-1100 HC-1300 HC-1400 | 1000–1500 | 0.411 0.393 0.376 | 15.61 14.43 8.34 | 119.59 221.55 103.24 | 57.1 78.2 87.2 | [27] |

| Coconut sheath | K-CS Na-CS Zn-CS | 900 | 0.367 0.370 0.394 | 153.3 79.240 20.780 | 141.27 153.02 162.30 | 51.1 52.05 72 | [28] |

| Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) | HC600 HC800 HC1000 HC1400 HCox600 HCox800 HCox1000 HCox1400 | 600–1400 | 0.371 0.370 0.379 0.366 0.371 0.369 0.386 0.365 | 68.4242 4.7227 10.8565 12.1760 13.7254 1.1614 69.4572 9.3573 | 179.43 216.5 245.57 289.47 246.88 289.47 272.36 330.23 | 32.36 40.53 39.58 54.75 28.27 40.63 37.47 46.29 | [53] |

| Tobacco stems | HC-1100 HC-1300 HC-1500 HC-N1300 | 1100–1300 | 0.360 0.400 0.350 0.410 | 1.44 3.24 3.96 7.13 | 293 296 287 330 | 71.9 66.6 68.5 67.9 | [54] |

| Pine Ash wood Miscanthus Wheat straw | Pine Ash wood Miscanthus Wheat straw | 1400 | 0.375 0.371 - - | <3 <3 12 45 | 323.8 280 274 224 | 85 79 80 65 | [55] |

| Bamboo (moso bamboo), hardwood (eucalyptus), softwood (scots pine) and straw (juncao) | BC HWC SWC SC | 1200 + HCl treatment | 0.394 0.392 0.396 0.393 | 4.85 28.33 21.02 11.33 | 344.3 309.2 303.5 273.2 | 60.6 59.8 62.6 57.0 | [56] |

| Coffee silver skin (CHC), phenolic resin powder (SDP); coffee silver skin coating with phenolic resin (SDCP) | CHC SDP SDCP | 1000 | 0.378 0.398 0.389 | 141.83 2.34 2.67 | 203.42 255.35 270.89 | 60.50 65.46 65.89 | [57] |

| Bamboo waste | HCB-1000 HCB-1200 HCB-1400 HCB-1600 | 1000–1400 | 0.397 0.387 0.382 0.378 | 61.14 35.02 10.78 10.48 | 136.4 267.1 328.4 296.9 | 39.1 61.5 67.8 66.7 | [58] |

| Potato starch (PS) | PC-800 PC-1000 PC-1200 PC-1400 PC-1500 | 800–1500 | 0.389 0.384 0.379 0.378 0.372 | 331.0 3.4 3.2 2.1 1.7 | 200.0 225.6 243.0 235.6 224.7 | - - - - 90.6 | [59] |

| Peanut shells, coffee grounds, and sugarcane bagasse | HC-P HC-C HC-S | 1000 + HCl treatment | 0.373 0.368 0.355 | 35.46 57.79 87.26 | 203,6 187,9 112,1 | 53.84 50.46 28.02 | [60] |

| Paulownia xylem | HC-1000 HC-1100 HC-1200 HC-1300 HC-1400 | 1000–1400 | 0.379 0.375 0.374 0.372 0.368 | 270.8 - 28.3 - 18.6 | 239 at 0.5C - 291.2 0.5C - 313 0.5C 209 10C | 76.8 77.9 81.8 82.6 85.9 | [61] |

| Typha leaves | VHC-800 VHC-900 VHC-1000 VHC-1100 VHC-1200 VHC-1300 | 800–1300 | 0.387 0.386 0.383 0.383 0.380 0.367 | 114.27 89.59 136.62 174.69 227.57 287.21 | - - - - 285.3 - | 66.43 67.21 75.30 77.44 72.43 72.35 | [62] |

| Sasa kurilensis | B-900 B-NaOH-900 | 900 | 0.3794 0.3796 | 135.6 556.4 | 160 114 | 47 40 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marmaza, P.A.; Shichalin, O.O.; Priimak, Z.E.; Seroshtan, A.I.; Ivanov, N.P.; Lakienko, G.P.; Korenevskiy, A.S.; Syubaev, S.A.; Mayorov, V.Y.; Ushkova, M.A.; et al. Evaluation of Sasa kurilensis Biomass-Derived Hard Carbon as a Promising Anode Material for Sodium-Ion Batteries. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 668. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120668

Marmaza PA, Shichalin OO, Priimak ZE, Seroshtan AI, Ivanov NP, Lakienko GP, Korenevskiy AS, Syubaev SA, Mayorov VY, Ushkova MA, et al. Evaluation of Sasa kurilensis Biomass-Derived Hard Carbon as a Promising Anode Material for Sodium-Ion Batteries. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):668. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120668

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarmaza, Polina A., Oleg O. Shichalin, Zlata E. Priimak, Alina I. Seroshtan, Nikita P. Ivanov, Grigory P. Lakienko, Alexei S. Korenevskiy, Sergey A. Syubaev, Vitaly Yu. Mayorov, Maria A. Ushkova, and et al. 2025. "Evaluation of Sasa kurilensis Biomass-Derived Hard Carbon as a Promising Anode Material for Sodium-Ion Batteries" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 668. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120668

APA StyleMarmaza, P. A., Shichalin, O. O., Priimak, Z. E., Seroshtan, A. I., Ivanov, N. P., Lakienko, G. P., Korenevskiy, A. S., Syubaev, S. A., Mayorov, V. Y., Ushkova, M. A., Tokar, E. A., Korneikov, R. I., Efremov, V. V., Ognev, A. V., Papynov, E. K., & Tananaev, I. G. (2025). Evaluation of Sasa kurilensis Biomass-Derived Hard Carbon as a Promising Anode Material for Sodium-Ion Batteries. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 668. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120668