Preparation and Characterization of Polyethylene-Based Composites with Iron-Manganese “Core-Shell” Nanoparticles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Composite Preparation

2.2. Experimental Methods

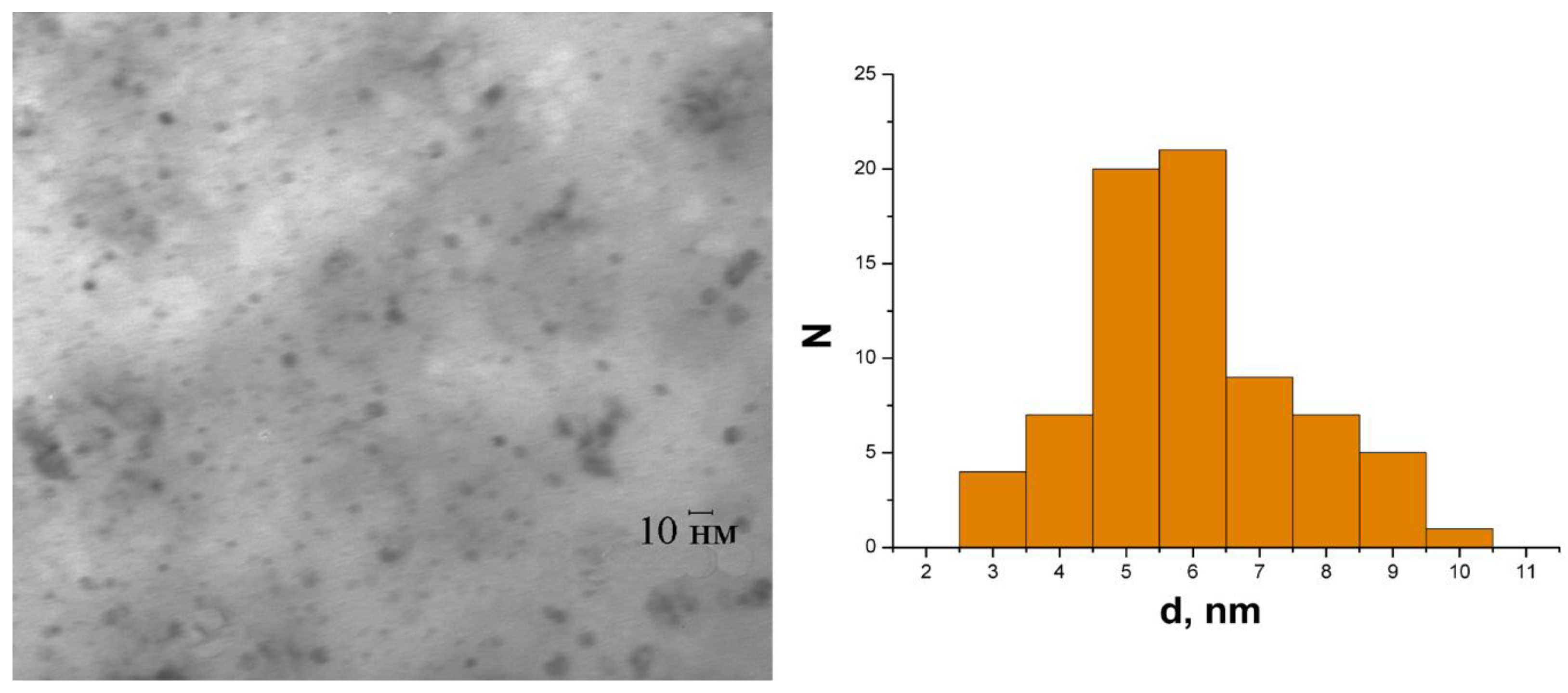

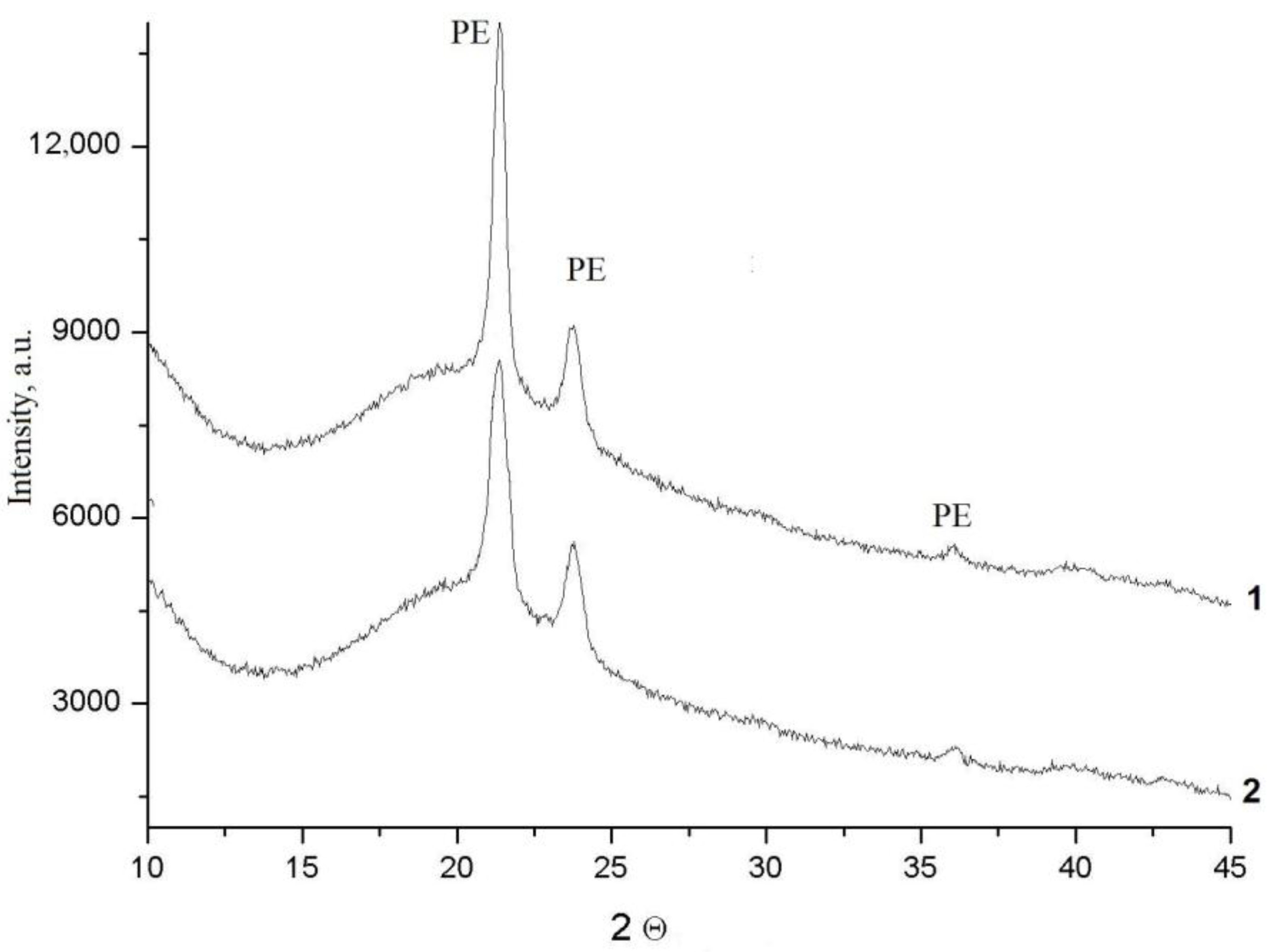

3. Results and Discussion

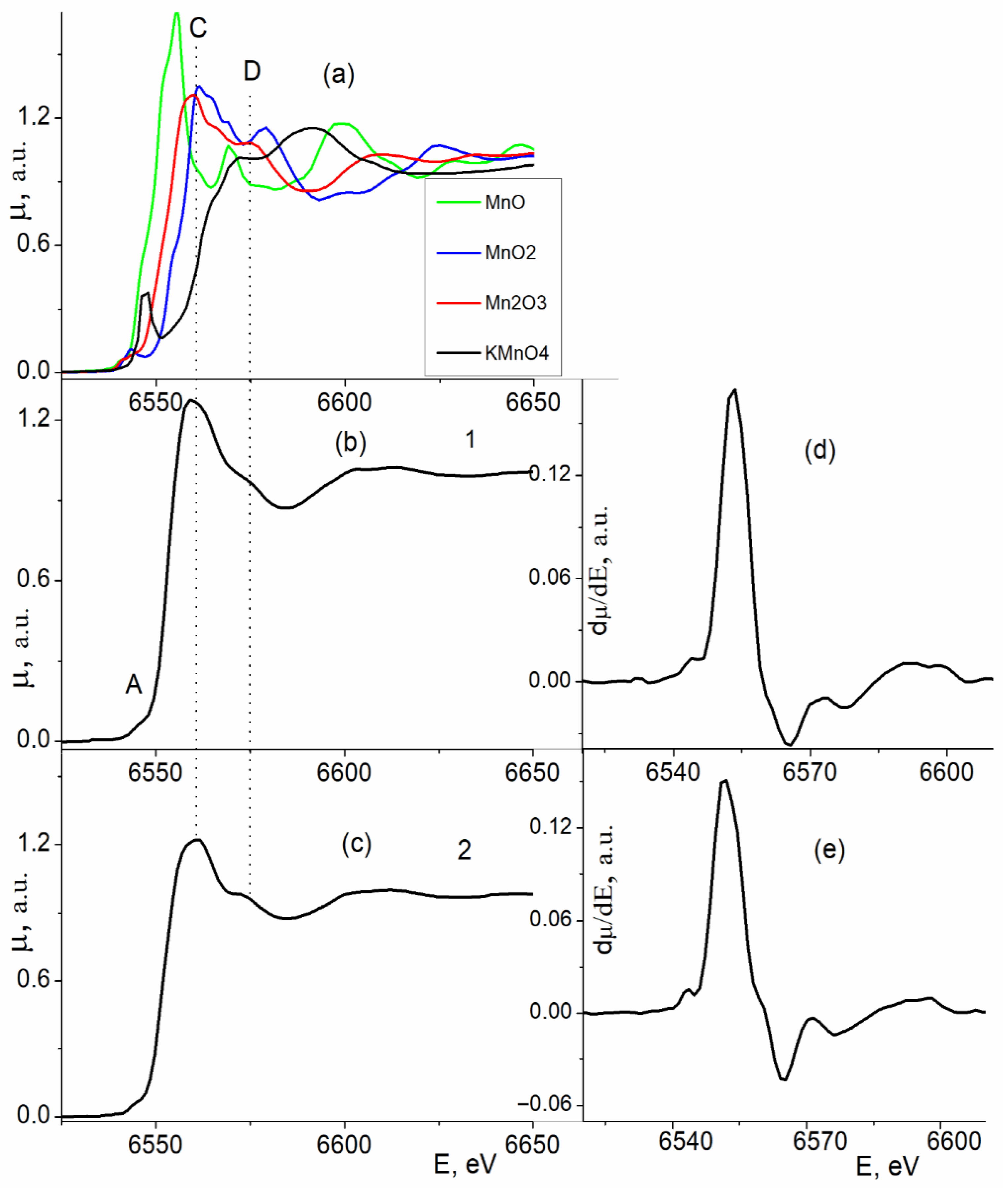

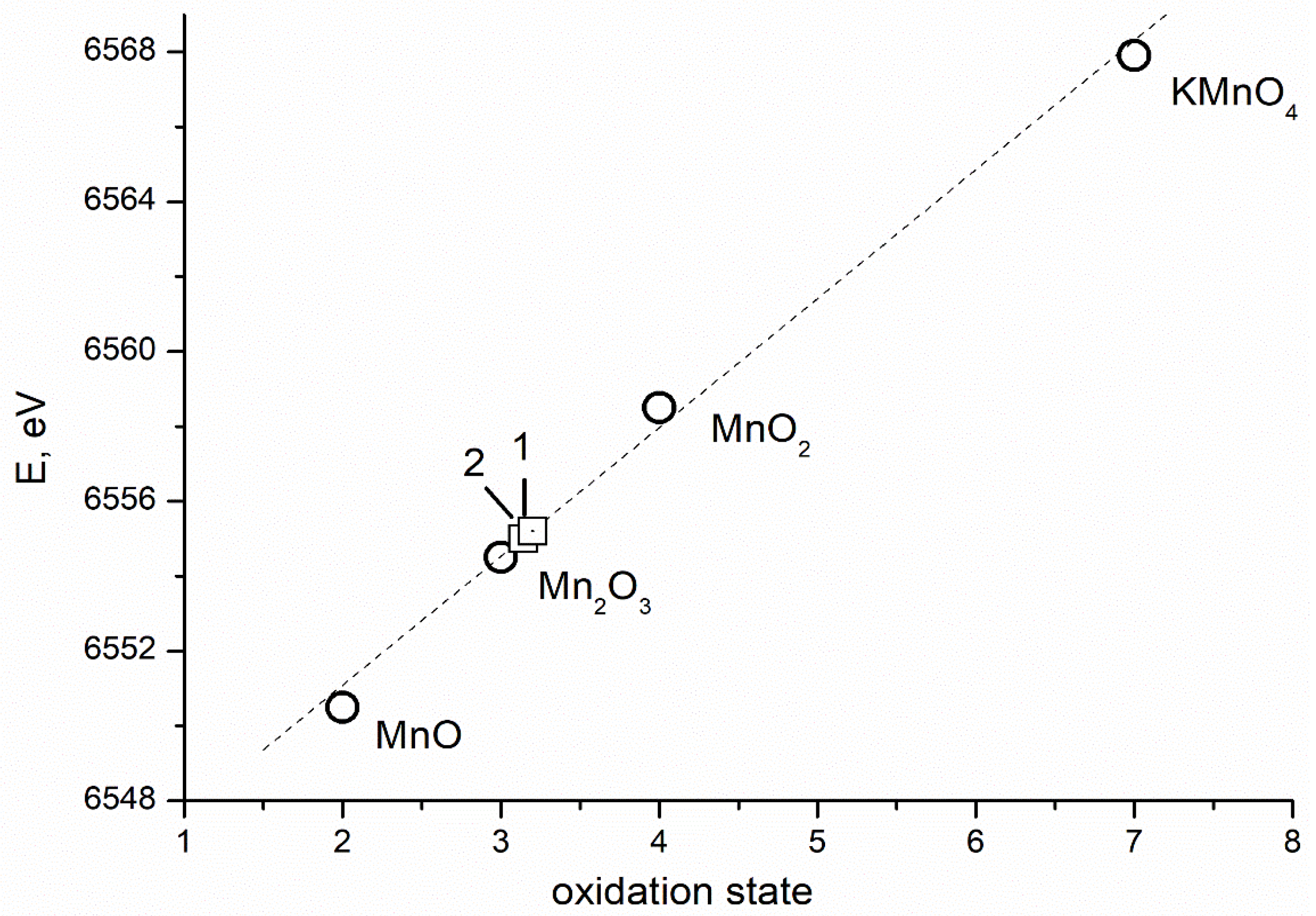

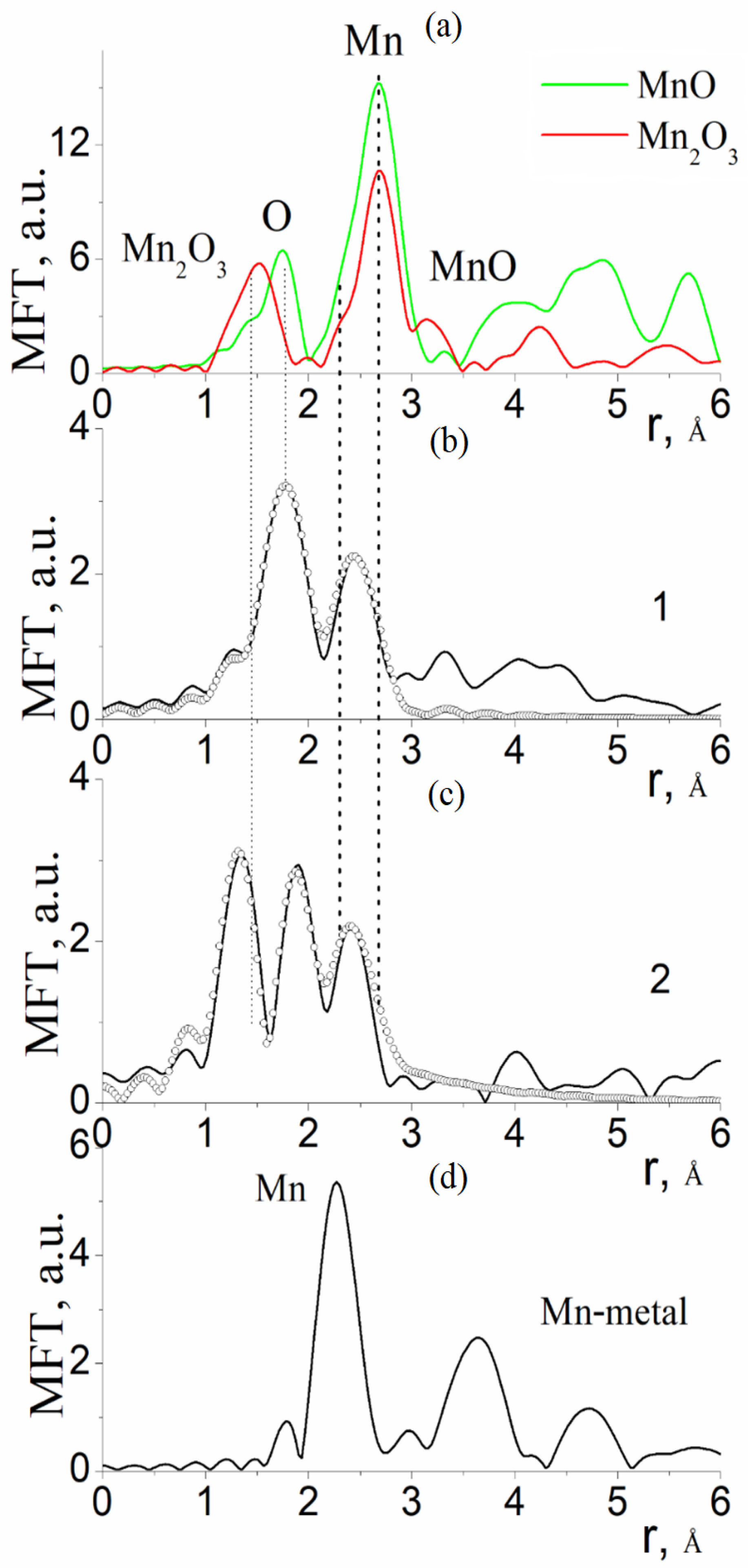

3.1. Results of the Study of the Electron and Atomic State of Manganese Atoms in Composite Materials

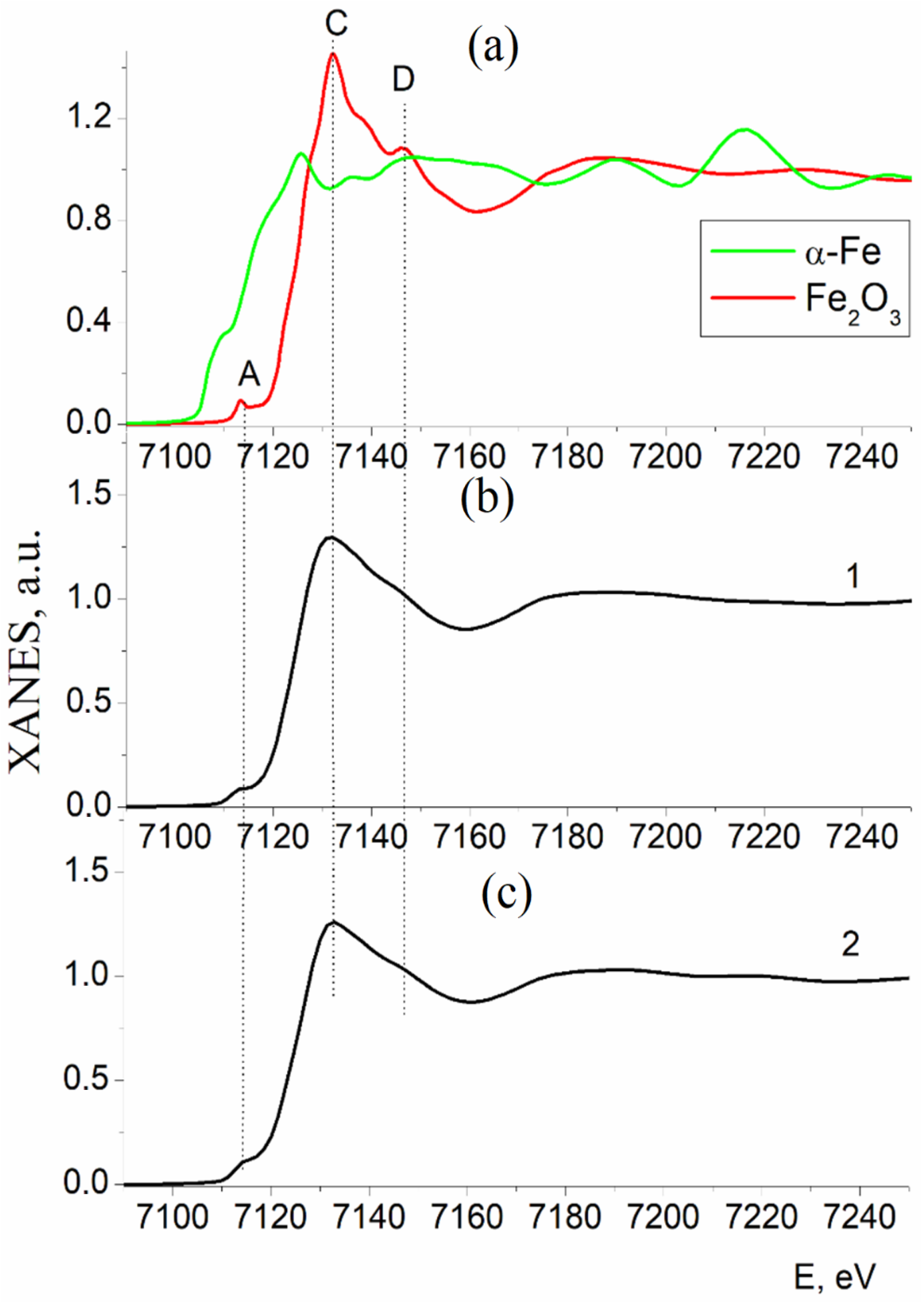

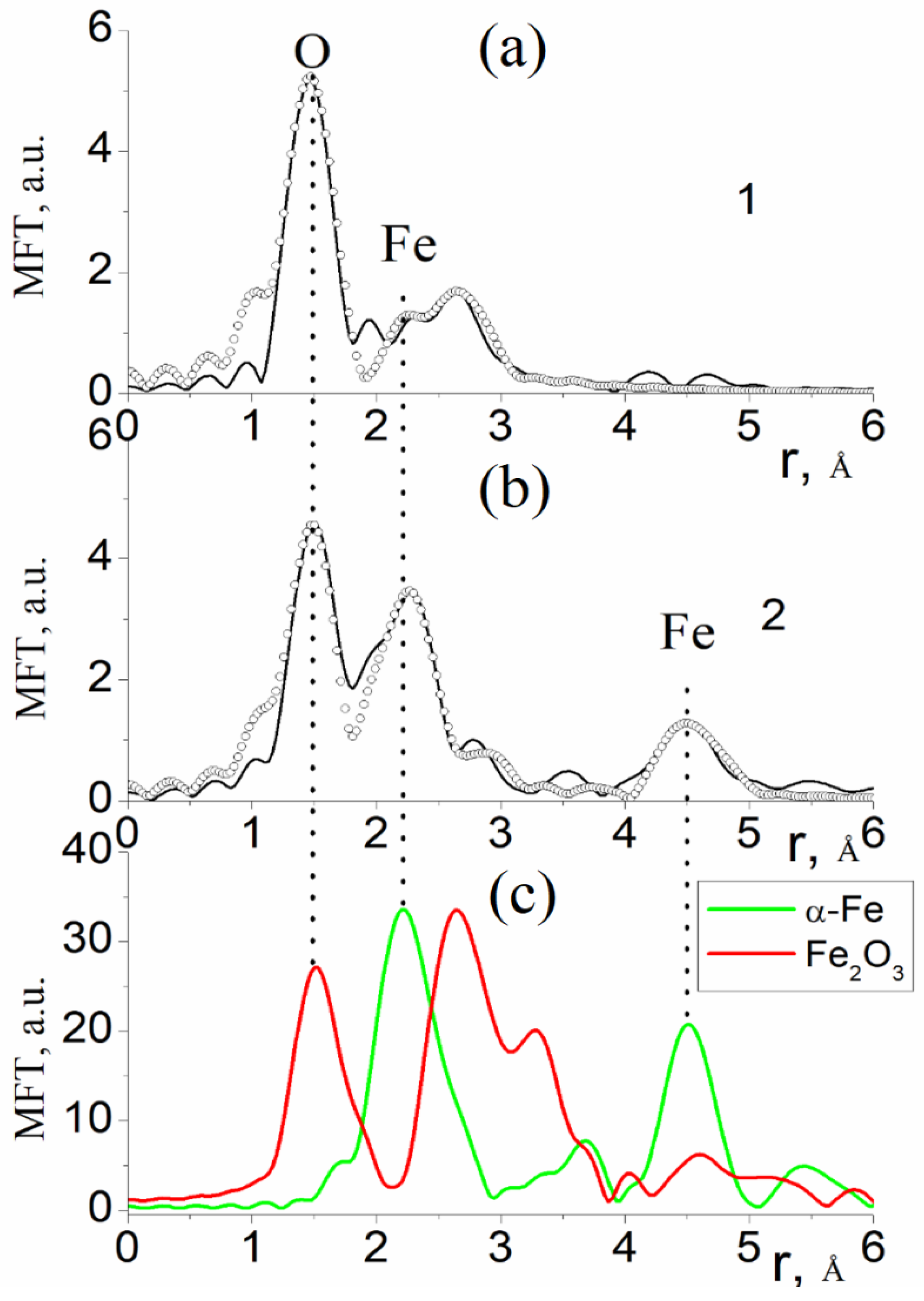

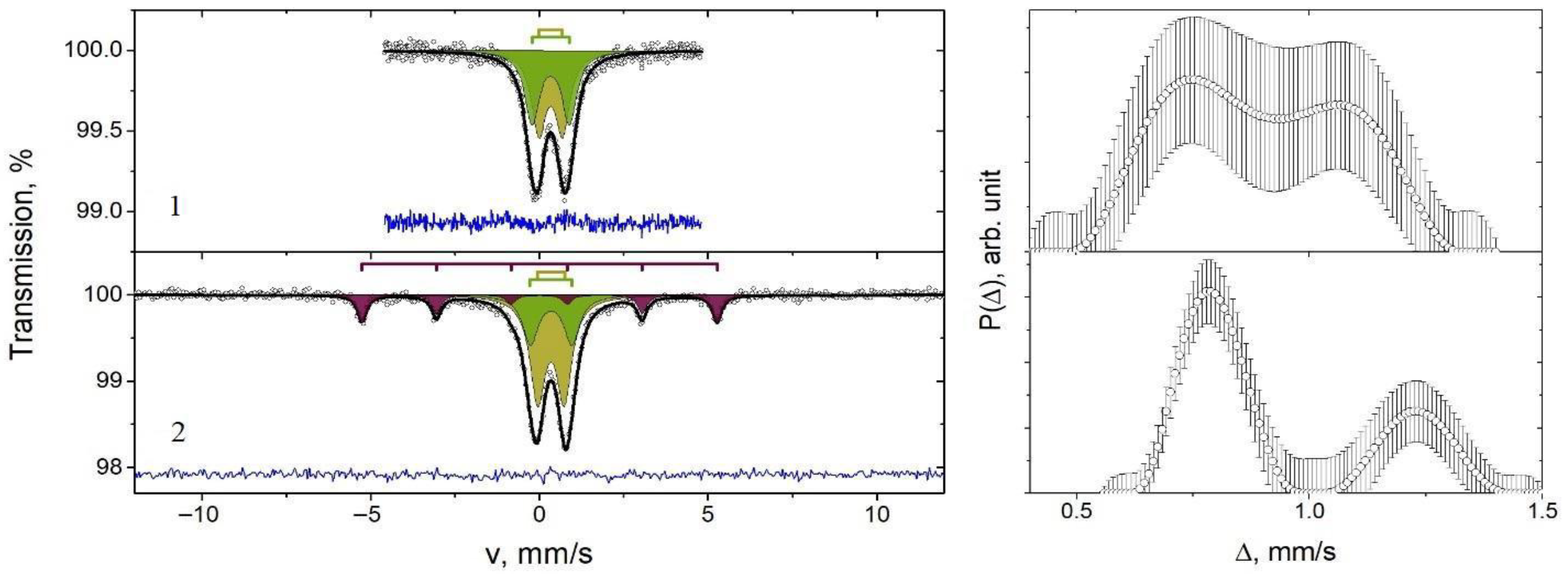

3.2. Results of the Study of the Electron and Atomic State of Iron Atoms in Composite Materials

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Evgin, T.; Turgut, A.; Hamaoui, G.; Špitalský, Z.; Horny, N.; Altay, L.; Chirtoc, M.; Omastová, M. Size Effect of Hybrid Carbon Nanofillers on the Synergetic Enhancement of the Properties of HDPE-Based Nanocomposites. Nanotechnology 2021, 32, 315704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anto, T.; Rejeesh, C.R. Synthesis and Characterization of Recycled HDPE Polymer Composite Reinforced with Nano-Alumina Particles. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 72, 3177–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makowiec, M.E.; Gionta, G.L.; Bhargava, S.; Ozisik, R.; Blanchet, T.A. Wear Resistance Effects of Alumina and Carbon Nanoscale Fillers in PFA, FEP, and HDPE Polymers. Wear 2022, 502–503, 204376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirors, M. The History of Polyethylene. In 100+ Years of Plastics. Leo Baekeland and Beyond; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Volume 1080, pp. 115–145. ISBN 978-0-8412-2677-7. [Google Scholar]

- Yurkov, G.Y.; Kozinkin, A.V.; Kubrin, S.P.; Zhukov, A.M.; Podsukhina, S.S.; Vlasenko, V.G.; Fionov, A.S.; Kolesov, V.V.; Zvyagintsev, D.A.; Vyatkina, M.A.; et al. Nanocomposites Based on Polyethylene and Nickel Ferrite: Preparation, Characterization, and Properties. Polymers 2023, 15, 3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanase, M.; Nuhfer, N.T.; Laughlin, D.E.; Klemmer, T.J.; Liu, C.; Shukla, N.; Wu, X.; Weller, D. Crystallographic Ordering Studies of FePt Nanoparticles by HREM. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2003, 266, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurkov, G.Y.; Biryukova, M.I.; Koksharov, Y.A.; Pankratov, D.A.; Kozinkin, A.V.; Vlasenko, V.G.; Ovchenkov, E.A.; Chursova, L.V.; Bouznik, V.M. Synthesis and structure of composite materials based on low density polyethylene and Pt@Fe2O3 nanoparticles. Perspekt. Mater. 2013, 6, 51–62. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Yurkov, G.Y.; Kozinkin, A.V.; Shvachko, O.V.; Kubrin, S.P.; Ovchenkov, E.A.; Korobov, M.S.; Kirillov, V.E.; Osipkov, A.S.; Makeev, M.O.; Ryzhenko, D.S.; et al. One-Step Synthesis of Composite Materials Based on Polytetrafluoroethylene Microgranules and Co@Fe2O3-FeF2 Nanoparticles. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, e52890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskakov, A.O.; Solov’eva, A.Y.; Ioni, Y.V.; Starchikov, S.S.; Lyubutin, I.S.; Khodos, I.I.; Avilov, A.S.; Gubin, S.P. Magnetic and Interface Properties of the Core-Shell Fe3O4/Au Nanocomposites. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 422, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, A.E.; Ivanova, O.S.; Fedorov, A.S.; Kovaleva, E.A.; Vysotin, M.A.; Lin, C.-R.; Ovchinnikov, S.G. Why the Magnetite–Gold Core–Shell Nanoparticles Are Not Quite Good and How to Improve Them. Phys. Solid State 2021, 63, 1536–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konicki, W.; Sibera, D.; Narkiewicz, U. Adsorption of Acid Red 88 Anionic Dye from Aqueous Solution onto ZnO/ZnMn2O4 Nanocomposite: Equilibrium, Kinetics, and Thermodynamics. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2017, 26, 2585–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovanović, L.; Radovanović, Ž.; Simović, B.; Vasić, M.V.; Balanč, B.; Dapčević, A.; Dramićanin, M.; Rogan, J. Structure and Properties of ZnO/ZnMn2O4 Composite Obtained by Thermal Decomposition of Terephthalate Precursor. J. Serbian Chem. Soc. 2023, 88, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratov, D.G.; Kozhitov, L.V.; Kazaryan, T.M.; Vasil’ev, A.A.; Popkova, A.V.; Korovin, E.Y. Synthesis and Electromagnetic Properties of FeCoNi/C Nanocomposites Based on Polyvinyl Alcohol. Russ. Microelectron. 2021, 50, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratov, D.G.; Kozhitov, L.V.; Yakushko, E.V.; Vasilev, A.A.; Popkova, A.V.; Tarala, V.A.; Korovin, E.Y. Synthesis, Structure and Electromagnetic Properties of FeCoAl/C Nanocomposites. Mod. Electron. Mater. 2021, 7, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, M.A.; El-Rahman, T.M.A.A.; Abdelsalam, H.K.; El-Souad, S.M.S.A.; Shady, R.M.; Amen, R.A.; Zaki, M.A.; Mohsen, M.; Desouky, S.; Saeed, S.; et al. Biosynthesis of Silver, Copper, and Their Bi-Metallic Combination of Nanocomposites by Staphylococcus Aureus: Their Antimicrobial, Anticancer Activity, and Cytotoxicity Effect. Indian J. Microbiol. 2024, 64, 1721–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, R.S.; Khairnar, S.D.; Patil, M.R.; Adole, V.A.; Koli, P.B.; Deshmane, V.V.; Halwar, D.K.; Shinde, R.A.; Pawar, T.B.; Jagdale, B.S.; et al. Synthesis and Characterization of ZnO/CuO Nanocomposites as an Effective Photocatalyst and Gas Sensor for Environmental Remediation. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2022, 32, 1045–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelekew, O.A.; Fufa, P.A.; Sabir, F.K.; Duma, A.D. Water Hyacinth Plant Extract Mediated Green Synthesis of Cr2O3/ZnO Composite Photocatalyst for the Degradation of Organic Dye. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angotzi, M.S.; Mameli, V.; Cara, C.; Peddis, D.; Xin, H.L.; Sangregorio, C.; Laura Mercuri, M.; Cannas, C. On the Synthesis of Bi-Magnetic Manganese Ferrite-Based Core–Shell Nanoparticles. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 1612–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; He, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, G.; Yuan, G. Novel Core–Shell Structured Mn–Fe/MnO2 Magnetic Nanoparticles for Enhanced Pb(II) Removal from Aqueous Solution. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 18481–18488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Soriano, D.; Milán-Rois, P.; Lafuente-Gómez, N.; Navío, C.; Gutiérrez, L.; Cussó, L.; Desco, M.; Calle, D.; Somoza, Á.; Salas, G. Iron Oxide-Manganese Oxide Nanoparticles with Tunable Morphology and Switchable MRI Contrast Mode Triggered by Intracellular Conditions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 613, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, A.; Rahman, M.M.; Longo, P.; Horn, S. Synthesis and High-Resolution Structural and Chemical Analysis of Iron-Manganese-Oxide Core-Shell Nanocubes. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybaltovskij, A.A.; Zavorotnyj, Y.S.; Epifanov, E.O.; Shubny, A.; Yusupov, V.I.; Minaev, N.G.; Hmelenin, D.N. Two Approaches to the Laser-induced Formation of Au/Ag Bimetallic Nanoparticles in Supercritical Carbon Dioxide. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisov, R.V.; Belousov, O.V.; Zhizhaev, A.M.; Lihackij, M.N.; Belousova, N.V. Synthesis of Bimetallic Nanoparticles Pd-Au and Pt-Au on Carbon Nanotubes in an Autoclave. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2021, 70, 1474–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervikov, A.V.; Lozhkomoev, A.S.; Bakina, O.V.; Lerner, M.I. Formation of Structural-Phase States in Ag–Cu Bimetallic Nanoparticles Produced By Electrical Explosion of Wires. Russ. Phys. J. 2021, 63, 1557–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batsalova, T.; Vasil’kov, A.; Moten, D.; Voronova, A.; Teneva, I.; Naumkin, A.; Dzhambazov, B. Bimetallic Gold–Iron Oxide Nanoparticles as Carriers of Methotrexate: Perspective Tools for Biomedical Applications. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, M.; Ivanova, P. Bimetallic and Multimetallic Nanoparticles as Nanozymes. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 336, 129736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohar, A.; Vijayakanth, V.; Vattikuti, S.V.P.; Kim, K.H. A Mini-Review on AFe2O4 (A = Zn, Mg, Mn, Co, Cu, and Ni) Nanoparticles: Photocatalytic, Magnetic Hyperthermia and Cytotoxicity Study. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 286, 126117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefeni, K.K.; Msagati, T.A.M.; Mamba, B.B. Ferrite Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization and Applications in Electronic Device. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2017, 215, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.; Eskandari, K.; Salavati-Niasari, M. Magnetically Retrievable Ferrite Nanoparticles in the Catalysis Application. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 271, 101982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.; Salavati-Niasari, M.; Akbari, A. Magnetic Nanocarriers: Evolution of Spinel Ferrites for Medical Applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 265, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozakov, A.T.; Kolesnikov, V.I.; Sidashov, A.V.; Guglev, K.A. Study of the Segregation Phenomena on the Surface of Binary Alloys and Steels in Oxygen Environment. Bull. Russ. Acad. Sci. Phys. 2009, 73, 690–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozakov, A.T.; Kolesnikov, V.I.; Sidashov, A.V.; Nikol’skii, A.V. Peculiarities of Segregation Phenomena at the Surface of PdxV1−x alloys in an Oxygen Medium. J. Surf. Investig. 2007, 1, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidashov, A.V.; Kozakov, A.T.; Yares’ko, S.I.; Manturov, D.S.; Marunevich, O.V. Effect of Nd: YAG Pulsed Laser Radiation on Oxidation and Segregation Processes in the Surface Layers of T8 High Speed Tool Steel: Tribological Consequences. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 564, 150434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsonov, G.V. The Oxide Handbook; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4615-9597-7. [Google Scholar]

- Koksharov, Y.A.; Yurkov, G.Y.; Baranov, D.A.; Malakho, A.P.; Polyakov, S.N.; Gubin, S.P. Electron Magnetic Resonance Spectra of Fe1−xMnx Amorphous Nanoparticles. Phys. Solid State 2006, 48, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubin, S.P.; Yurkov, G.Y.; Kosobudsky, I.D. Nanomaterials Based on Metal-Containing Nanoparticles in Polyethylene and Other Carbon-Chain Polymers. Int. J. Mater. Prod. Technol. 2005, 23, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhukov, A.M.; Solodilov, V.I.; Tretyakov, I.V.; Burakova, E.A.; Yurkov, G.Y. The Effect of the Structure of Iron-Containing Nanoparticles on the Functional Properties of Composite Materials Based on High-Density Polyethylene. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 16, 926–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunker, G. Introduction to XAFS: A Practical Guide to X-Ray Absorption Fine Structure Spectroscopy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Newville, M. EXAFS Analysis Using FEFF and FEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2001, 8, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabinsky, S.I.; Rehr, J.J.; Ankudinov, A.; Albers, R.C.; Eller, M.J. Multiple-Scattering Calculations of x-Ray-Absorption Spectra. Phys. Rev. B 1995, 52, 2995–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsnev, M.E.; Rusakov, V.S. SpectrRelax: An Application for Mössbauer Spectra Modeling and Fitting. AIP Conf. Proc. 2012, 1489, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurkov, G.Y.; Fionov, A.S.; Kozinkin, A.V.; Koksharov, Y.A.; Ovtchenkov, Y.A.; Pankratov, D.A.; Popkov, O.V.; Vlasenko, V.G.; Kozinkin, Y.A.; Biryukova, M.I.; et al. Synthesis and Physicochemical Properties of Composites for Electromagnetic Shielding Applications: A Polymeric Matrix Impregnated with Iron- or Cobalt-Containing Nanoparticles. J. Nanophotonics 2012, 6, 061717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurkov, G.Y.; Gubin, S.P.; Pankratov, D.A.; Koksharov, Y.A.; Kozinkin, A.V.; Spichkin, Y.I.; Nedoseikina, T.I.; Pirog, I.V.; Vlasenko, V.G. Iron(III) Oxide Nanoparticles in a Polyethylene Matrix. Inorg. Mater. 2002, 38, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Wang, Z.; Bao, Y.; Gu, C.; Zhang, Z. Effect of Silicon–Manganese Deoxidation on Oxygen Content and Inclusions in Molten Steel. Processes 2024, 12, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P.R.S.; Wallwork, G.R. High Temperature Oxidation of Iron-Manganese-Aluminum Based Alloys. Oxid. Met. 1984, 21, 135–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craddock, P.T. The Many and Various Roles of Manganese in Iron and Steel Production. Mater. Sci. Forum 2020, 983, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | CN | R, Å | σ2, Å2 | CS | Q *, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Fe0.9Mn0.1) | 1.9 | 2.21 | 0.0039 | Mn-O | 1.5 |

| 0.7 | 2.74 | 0.0057 | Mn-Mn | ||

| 2 (Fe0.8Mn0.2) | 1.2 | 1.90 | 0.0040 | Mn-O | 2.1 |

| 1.9 | 2.43 | 0.0040 | Mn-O | ||

| 0.7 | 2.73 | 0.0050 | Mn-Mn |

| Sample | CN | R, Å | σ2, Å2 | CS | Q *, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Fe0.9Mn0.1) | 2.4 | 1.95 | 0.0037 | Fe-O (oxide) | 3.1 |

| 0.3 | 2.55 | 0.0055 | Fe-Fe (α-Fe) | ||

| 1.0 | 3.04 | 0.0055 | Fe-O (oxide) | ||

| 2 (Fe0.8Mn0.2) | 2.0 | 1.96 | 0.0037 | Fe-O (oxide) | 2.8 |

| 1.0 | 2.12 | 0.0037 | Fe-O (oxide) | ||

| 1.2 | 2.60 | 0.0055 | Fe-Fe (α-Fe) | ||

| 0.5 | 3.09 | 0.0055 | Fe-O (oxide) |

| Sample | Components | δ ± 0.02, mm/s | Δ/ε ± 0.02, mm/s | H ± 1, kOe | γ ± 0.02, mm/s | A ± 1, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Fe0.9Mn0.1) | D1 | 0.34 | 0.70 | 0.53 | 52 | |

| D2 | 0.34 | 1.11 | 0.53 | 48 | ||

| 2 (Fe0.8Mn0.2) | S | −0.01 | 0.01 | 326 | 0.33 | 17 |

| D1 | 0.35 | 0.81 | 0.56 | 59 | ||

| D2 | 0.34 | 1.23 | 0.56 | 24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yurkov, G.Y.; Kozinkin, A.V.; Maksimova, A.V.; Vlasenko, V.G.; Kubrin, S.P.; Kirillov, V.E.; Solodilov, V.I. Preparation and Characterization of Polyethylene-Based Composites with Iron-Manganese “Core-Shell” Nanoparticles. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120666

Yurkov GY, Kozinkin AV, Maksimova AV, Vlasenko VG, Kubrin SP, Kirillov VE, Solodilov VI. Preparation and Characterization of Polyethylene-Based Composites with Iron-Manganese “Core-Shell” Nanoparticles. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):666. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120666

Chicago/Turabian StyleYurkov, Gleb Yu., Alexander V. Kozinkin, Anna V. Maksimova, Valeriy G. Vlasenko, Stanislav P. Kubrin, Vladislav E. Kirillov, and Vitaliy I. Solodilov. 2025. "Preparation and Characterization of Polyethylene-Based Composites with Iron-Manganese “Core-Shell” Nanoparticles" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120666

APA StyleYurkov, G. Y., Kozinkin, A. V., Maksimova, A. V., Vlasenko, V. G., Kubrin, S. P., Kirillov, V. E., & Solodilov, V. I. (2025). Preparation and Characterization of Polyethylene-Based Composites with Iron-Manganese “Core-Shell” Nanoparticles. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120666