Advances in the Stabilization of Eutectic Salts as Phase Change Materials (PCMs) for Enhanced Thermal Performance: A Critical Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

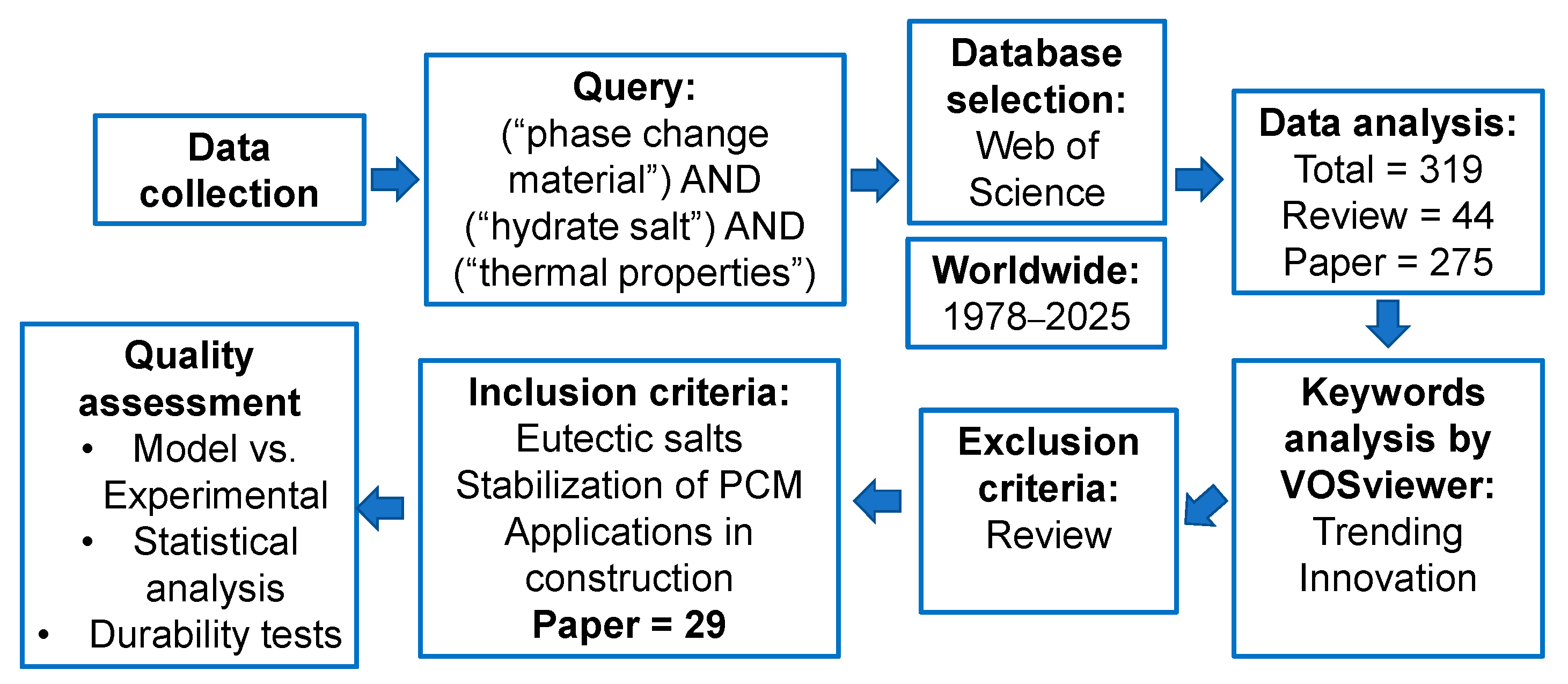

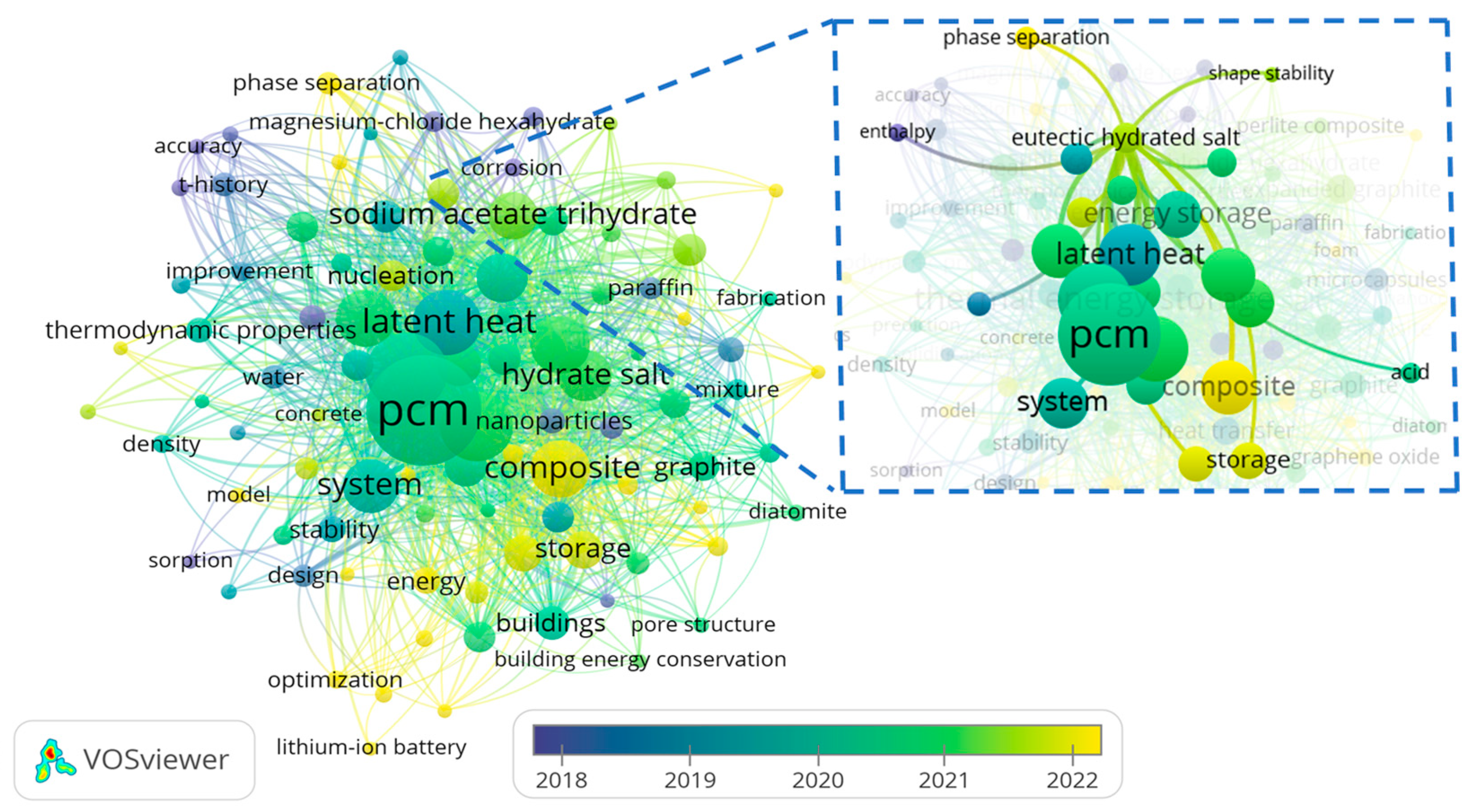

2. Data Collection Methodology

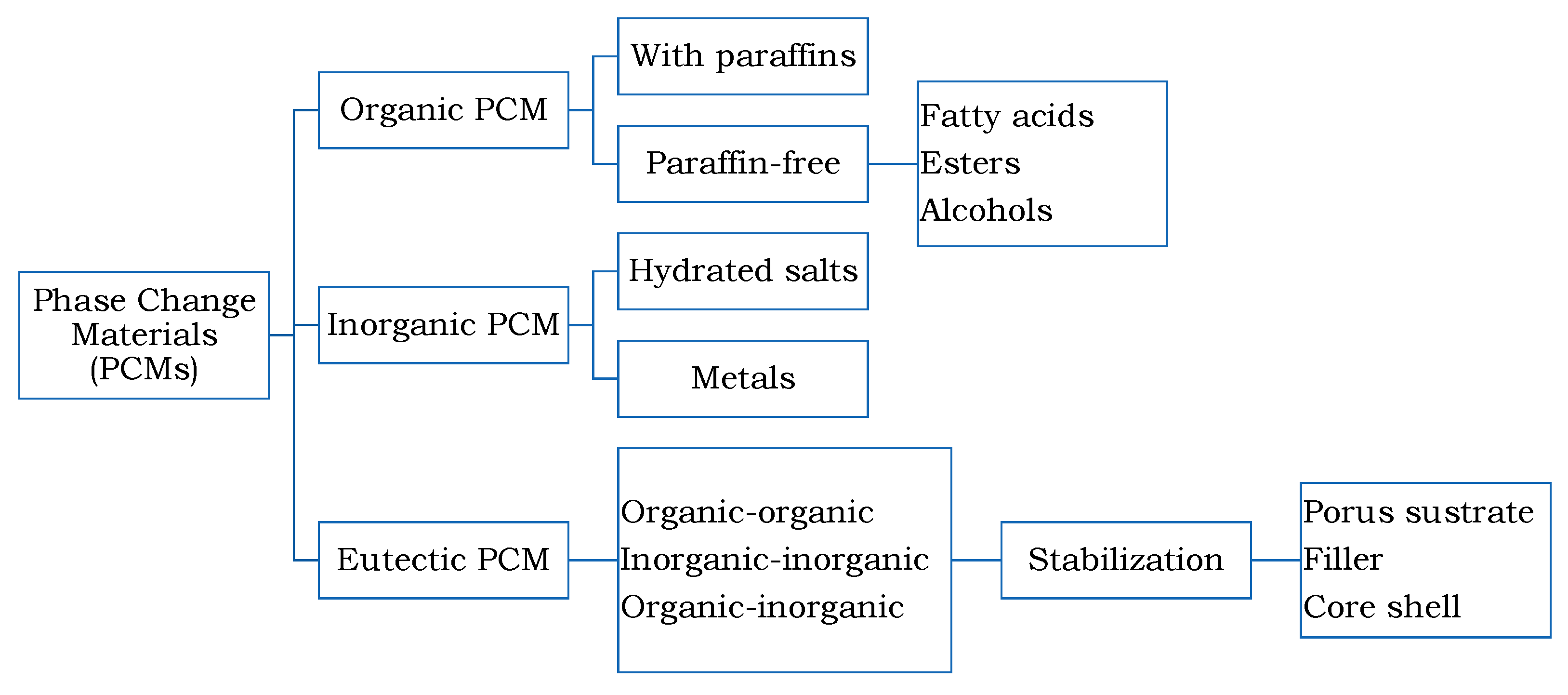

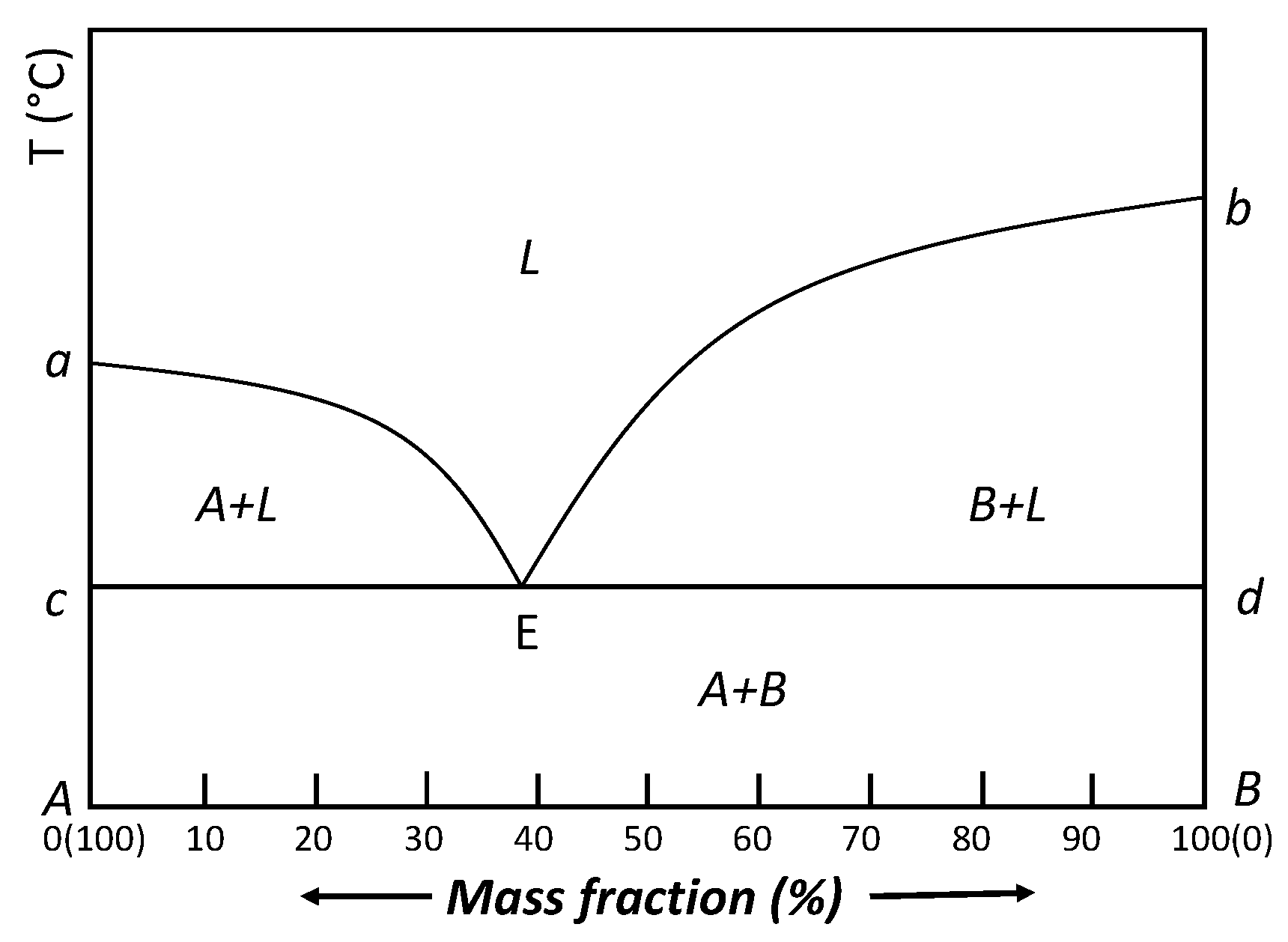

3. Eutectic PCM Stabilization

| Eutectic Salt | Mass Ratio | Substrate | Core–Shell | Filler | Phase Transition Temperature (°C) | Melting Enthalpy (J·g−1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na2HPO4·12H2O/Na2S2O3·5H2O | 80:20 | melamine sponge | PU light-curing resin | - | 26.1 | 134.54 | [65] |

| CH3COONa·3H2O/CH4N2O | 6:4 | - | silica/nanosilica shell | - | 21.31 | 286.8 | [70] |

| Na2HPO4·12H2O/Na2CO3·10H2O | 6:4 | Expanded perlite | Epoxy resin and fly ash | - | 23.73 | 92.87 | [66] |

| MgCl2·6H2O/NH4Al(SO4)2·12H2O | 30:70 | Carbon aerogels | - | - | 64.7 | 156.93 | [67] |

| CH3COONa·3H2O/C2H5NO2/Na2HPO4·12H2O | 85.15:13.86:0.99 | Expanded graphite | - | - | 48.36 | 128.1 | [71] |

| BaCl2/KCl/NaCl | 53:28:19 | Geopolymer half shells | Al2O3 | - | - | 215 | [72] |

| NaAc∙3H2O/NH2CH2COOH | 88:12 | Expanded graphite | - | - | 48.62 | 258.5 | [73] |

| Na2CO3·10H2O/MgSO4·7H2O | 70:30 | polycrystalline silicon | - | - | 33.2 | 230.5 | [25] |

| Na2CO3·10H2O/Na2HPO4·12H2O | - | expanded graphite | - | - | 23.5 | 196.2 | [40] |

| Al2(SO4)3·18H2O/FeSO4·7H2O | 2:1 | carboxymethyl cellulose | - | carbon nanotubes | 80–150 | 420 | [64] |

| MgCl2∙6H2O/MgSO4∙7H2O | 92.15:4.85 | Activated carbon | - | - | 90.21 | 156.14 | [63] |

| Ba(OH)2∙8H2O/KCl | 90:10 | expanded graphite | - | - | 66.25 | 206.4 | [39] |

| Ba(OH)2∙8H2O/KNO3 | 88:12 | 67.71 | 231.5 | ||||

| CH3COONa·3H2O/Na2S2O3·5H2O | 28:72 | Melamine sponge | - | Polyurethane | 41.45 | 186.6 | [20] |

| Na2SO4·10H2O/Na2HPO4·12H2O | 80:20 | - | - | - | 33.4 | 253.5 | [36] |

| Na2CO3·10H2O/Na2SO4·10H2O/Na2HPO4·12H2O | 0.4:1.0:0.7 | Graphene Nanoplatelets | - | - | 21.5 | 207 | [30] |

| Na2SO4·10H2O/Na2HPO4·12H2O | 62:38 | Coconut shell biochar | - | - | 27.8 | 218.1 | [28] |

| Na2SO4·10H2O/Na2HPO4·12H2O | 62:38 | MAX Phase material (Ti3AlC2) | - | - | 27.6 | 216 | [26] |

| NaH2PO4·2H2O/Na2S2O3·5H2O/K2HPO4·3H2O | 6:6:6 | - | - | Nanoactivatedcarbon/Sodiumtetraborate/Sodiumfluoride | 11.9 10.6 14.8 | 127.2 118.6 82.56 | [48] |

| Na2SO4·10H2O/Na2HPO4·12H2O | 75:25 | - | - | nano-α-Al2O3 | 31.2 | 280.1 | [50] |

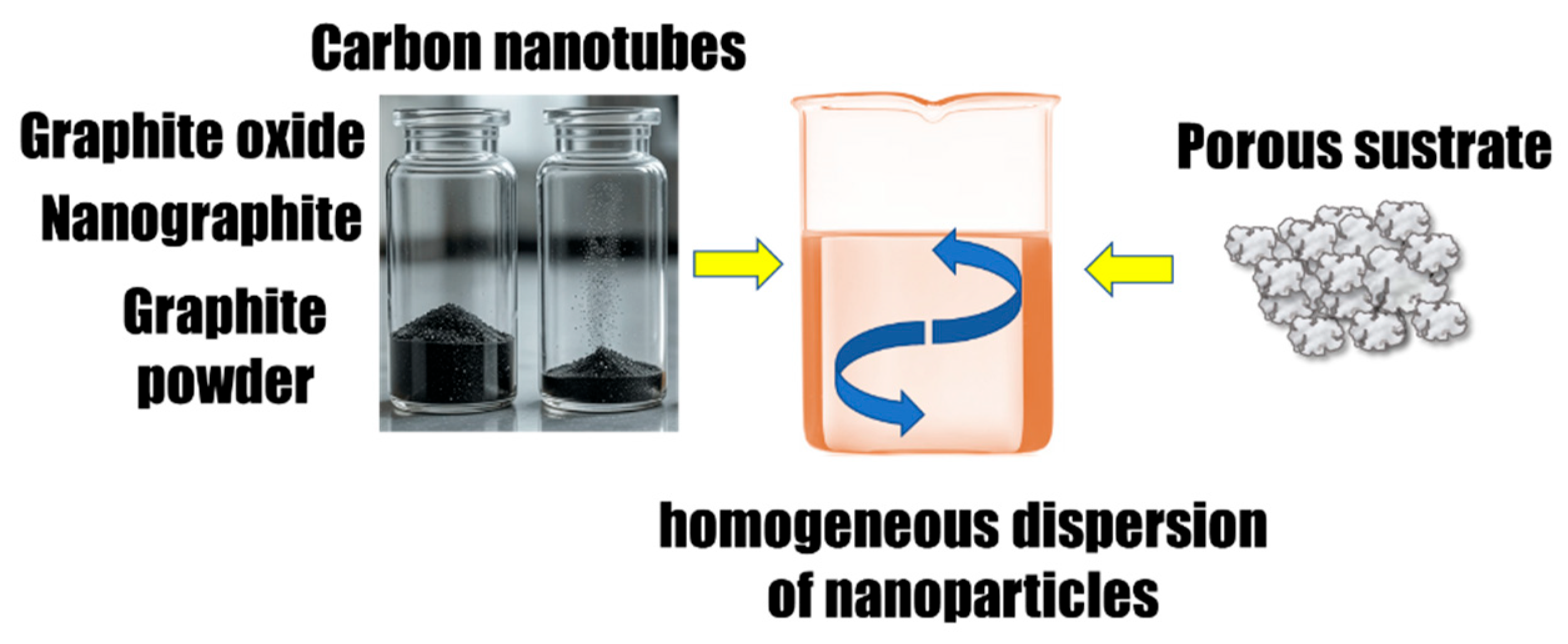

4. Eutectic Salts Stabilization via Porous Substrates

5. Eutectic Salts Stabilization via Encapsulation

6. Application of Carbon-Based Fillers in PCM Composites

7. Mitigation of Supercooling and Stability Enhancement

8. Discussion on the Holistic Design of PCMs

9. Conclusions

- In terms of PCM content, 60–70 wt% within porous matrices ensures leakage-free operation;

- Regarding filler loading, ≤3 wt% carbon-based additives provide a conductivity gain of 100–200% with <10% latent heat penalty;

- Cycle durability of encapsulated or supported PCMs can retain >90% enthalpy after 200–300 cycles when proper pore confinement and interfacial coupling are achieved.

10. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zahir, M.H.; Mohamed, S.A.; Saidur, R.; Al-Sulaiman, F.A. Supercooling of Phase-Change Materials and the Techniques Used to Mitigate the Phenomenon. Appl. Energy 2019, 240, 793–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harish, V.S.K.V.; Kumar, A. A Review on Modeling and Simulation of Building Energy Systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 56, 1272–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Dahlhauser, S.D.; Lucci, C.; Donohoe, B.S.; Allen, R.D.; Rorrer, N.A. Shape-Stabilization of Phase Change Materials with Carbon-Conscious Poly(Hydroxy)Urethane Foams. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2421039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, W.; Zou, X.; Wang, F.; Shu, X. Preparation and Performance of Inorganic Hydrated Salt-Based Composite Materials for Temperature and Humidity Regulation. Int. J. Energy Res. 2024, 90, 111906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, J.; Ma, J.; Zhao, Z.; Xia, N.; Liu, J.; Peng, H.; Fang, T.; Fu, W. Preparation and Properties of Na2HPO4∙12H2O/Silica Aerogel Composite Phase Change Materials for Building Energy Conservation. Materials 2024, 17, 5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Luo, J.; Li, Z.; Huang, Z.; Gao, X.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Salt Hydrate/Expanded Vermiculite Composite as a Form-Stable Phase Change Material for Building Energy Storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2019, 189, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, U.; Haggag, M.; Hassan, A.; Laghari, M. Evaluation of Phase Change Materials for Pre-Cooling of Supply Air into Air Conditioning Systems in Extremely Hot Climates. Buildings 2024, 14, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraj, K.; Khaled, M.; Faraj, J.; Hachem, F.; Chahine, K.; Castelain, C. Short Recent Summary Review on Evolving Phase Change Material Encapsulation Techniques for Building Applications. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 1245–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Z.; Zhang, G.; Xu, T.; Hong, K. Experimental Study on a Novel Form-Stable Phase Change Materials Based on Diatomite for Solar Energy Storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 182, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontoleon, K.J.; Stefanidou, M.; Saboor, S.; Mazzeo, D.; Karaoulis, A.; Zegginis, D.; Kraniotis, D. Defensive Behaviour of Building Envelopes in Terms of Mechanical and Thermal Responsiveness by Incorporating PCMs in Cement Mortar Layers. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 47, 101349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Liu, P.; Quan, X.; Ma, C. Characterization and Cooling Effect of a Novel Cement-Based Composite Phase Change Material. Sol. Energy 2020, 208, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Niu, J.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, Y. Development of Polyurethane Acrylate Coated Salt Hydrate/Diatomite Form-Stable Phase Change Material with Enhanced Thermal Stability for Building Energy Storage. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 259, 119714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Giacomello, A.; Meloni, S.; Dauvergne, J.L.; Nikulin, A.; Palomo, E.; Ding, Y.; Faik, A. Hierarchical Macro-Nanoporous Metals for Leakage-Free High-Thermal Conductivity Shape-Stabilized Phase Change Materials. Appl. Energy 2020, 269, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, T.; Hu, L.; Wang, Y.; Nie, S. Facile Preparation and Adjustable Thermal Property of Stearic Acid-Graphene Oxide Composite as Shape-Stabilized Phase Change Material. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 215–216, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, K.; Gao, X.; Ren, M.; Jia, M.; Yang, Y. Enhanced Thermal Properties of Hydrate Salt/Poly (Acrylate Sodium) Copolymer Hydrogel as Form-Stable Phase Change Material via Incorporation of Hydroxyl Carbon Nanotubes. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2020, 208, 110387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Wang, Q.; Ye, R.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Z. A Calcium Chloride Hexahydrate/Expanded Perlite Composite with Good Heat Storage and Insulation Properties for Building Energy Conservation. Renew. Energy 2017, 114, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Y. Form-Stable Phase Change Material Based on Na2CO3·10H2O-Na2HPO4·12H2O Eutectic Hydrated Salt/Expanded Graphite Oxide Composite: The Influence of Chemical Structures of Expanded Graphite Oxide. Renew. Energy 2018, 115, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ling, Z.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Z. Microinfiltration of Mg(NO3)2·6H2O into g-C3N4 and Macroencapsulation with Commercial Sealants: A Two-Step Method to Enhance the Thermal Stability of Inorganic Composite Phase Change Materials. Appl. Energy 2019, 253, 113540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ravensteijn, B.G.P.; Donkers, P.A.J.; Ruliaman, R.C.; Eversdijk, J.; Fischer, H.R.; Huinink, H.P.; Adan, O.C.G. Encapsulation of Salt Hydrates by Polymer Coatings for Low-Temperature Heat Storage Applications. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 1712–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liang, X.; Wang, S.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, Y. Polyurethane Macro-Encapsulation for CH3COONa·3H2O-Na2S2O3·5H2O/Melamine Sponge to Fabricate Form-Stable Composite Phase Change Material. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 410, 128308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Ge, C.; Zhang, R.; Ma, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X. Boron Nitride Foam as a Polymer Alternative in Packaging Phase Change Materials: Synthesis, Thermal Properties and Shape Stability. Appl. Energy 2019, 238, 942–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrali, M.; ten Elshof, J.E.; Shahi, M.; Mahmoudi, A. Simultaneous Solar-Thermal Energy Harvesting and Storage via Shape Stabilized Salt Hydrate Phase Change Material. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 405, 126624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Shi, L.; Zhang, S.; Li, W. Enhanced Thermal Performance of Phase Change Mortar Using Multi-Scale Carbon-Based Materials. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, K.; Pandey, A.K.; Bhutto, Y.A.; Islam, A.; Kareri, T.; Rahman, S.; Buddhi, D.; Tyagi, V.V. Evolving Thermal Energy Storage Using Hybrid Nanoparticle: An Experimental Investigation on Salt Hydrate Phase Change Materials for Greener Future. Energy Technol. 2024, 13, 2400248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichandi, R.; Murugavel Kulandaivelu, K.; Alagar, K.; Dhevaguru, H.K.; Ganesamoorthy, S. Performance Enhancement of Photovoltaic Module by Integrating Eutectic Inorganic Phase Change Material. Energy Sources Part A Recover. Util. Environ. Eff. 2020, 46, 16360–16377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalidasan, B.; Pandey, A.K.; Saidur, R.; Han, T.K.; Mishra, Y.N. MXene-Based Eutectic Salt Hydrate Phase Change Material for Efficient Thermal Features, Corrosion Resistance & Photo-Thermal Energy Conversion. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 25, 100634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; He, R.; Fan, G.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, J.; Du, Y.; Zhou, W.; Yang, J. Hexadecanol-Palmitic Acid/Expanded Graphite Eutectic Composite Phase Change Material and Its Application in Photovoltaic Panel. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2024, 273, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalidasan, B.; Pandey, A.K.; Saidur, R.; Kothari, R.; Sharma, K.; Tyagi, V.V. Eco-Friendly Coconut Shell Biochar Based Nano-Inclusion for Sustainable Energy Storage of Binary Eutectic Salt Hydrate Phase Change Materials. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2023, 262, 112534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalidasan, B.; Pandey, A.K.; Saidur, R.; Tyagi, S.K.; Mishra, Y.K. Experimental Evaluation of Binary and Ternary Eutectic Phase Change Material for Sustainable Thermal Energy Storage. J. Energy Storage 2023, 68, 107707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, E.; Ternary, T.; Salt, E.; Material, P.C. Experimental Investigation of Graphene Nanoplatelets. Energies 2023, 16, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalidasan, B.; Pandey, A.K.; Saidur, R.; Mishra, Y.N.; Ma, Z.; Tyagi, V.V. Thermal Performance and Corrosion Resistance Analysis of Inorganic Eutectic Phase Change Material with One Dimensional Carbon Nanomaterial. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 391, 123281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalidasan, B.; Pandey, A.K.; Saidur, R.; Aljafari, B.; Kareri, T. Expanded Graphite Intersperse Reliable Binary Eutectic Phase Change Material for Low Temperature Thermal Regulation Systems. Mater. Today Sustain. 2023, 24, 100602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Ahmed, S.; Shamberger, P.; Yu, C. Achieving Extraordinary Thermal Stability of Salt Hydrate Eutectic Composites by Amending Crystallization Behaviour with Thickener. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 264, 110877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, G.; Zeng, H.; Guo, Z.; Cui, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, X.; Zhang, L.; Han, W. Studies of Eutectic Hydrated Salt/Polymer Hydrogel Composite as Form-Stable Phase Change Material for Building Thermal Energy Storage. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 59, 105010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zheng, W.; Gou, Y.; Jia, Y.; Li, H. Thermal Behaviors of Energy Storage Process of Eutectic Hydrated Salt Phase Change Materials Modified by Nano-TiO2. J. Energy Storage 2022, 53, 105077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, W.; Fang, J.; Jiang, W.; Ping, L.; Na, L.; Yanhan, F.; Wang, L. Preparation and Modification of Novel Phase Change Material Na2SO4·10H2O-Na2HPO4·12H2O Binary Eutectic Hydrate Salt. Energy Sources Part A Recover. Util. Environ. Eff. 2022, 44, 1842–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Nian, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, B.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Zhou, Y. Construction of Na2CO3·10H2O-Na2HPO4·12H2O Eutectic Hydrated Salt/NiCo2O4-Expanded Graphite Multidimensional Phase Change Material. J. Energy Storage 2022, 52, 104781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Hoe, A.; Alamo, F.; Turner, N.; Shamberger, P.J. Experimental Determination of High Energy Density Lithium Nitrate Hydrate Eutectics. J. Energy Storage 2022, 52, 104754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Wang, D.; Wang, S. Preparation and Thermal Performance of Phase Change Material with High Latent Heat and Thermal Conductivity Based on Novel Binary Inorganic Eutectic System. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2021, 230, 111186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Liu, L.; Yang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, J. Design of Eutectic Hydrated Salt Composite Phase Change Material with Cement for Thermal Energy Regulation of Buildings. Materials 2021, 14, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; Zeng, J.; Hai, C.; Ren, X.; Zhu, S.; Zhou, Y. Surface Evolution of Eutectic MgCl2·6H2O-Mg(NO3)2·6H2O Phase Change Materials for Thermal Energy Storage Monitored by Scanning Probe Microscopy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 565, 150549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Li, Z.; Gao, X.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Preparation and Performance of Modified Expanded Graphite/Eutectic Salt Composite Phase Change Cold Storage Material. Int. J. Refrig. 2020, 110, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Su, J.; Tang, Y.; Liang, X.; Wang, S.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Z. Form-Stable Na2SO4·10H2O-Na2HPO4·12H2O Eutectic/Hydrophilic Fumed Silica Composite Phase Change Material with Low Supercooling and Low Thermal Conductivity for Indoor Thermal Comfort Improvement. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 3171–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lin, S.; Ling, Z.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Z. Growth of the Phase Change Enthalpy Induced by the Crystal Transformation of an Inorganic-Organic Eutectic Mixture of Magnesium Nitrate Hexahydrate-Glutaric Acid. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 6751–6760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althoey, F.; Stutzman, P.; Steiger, M.; Farnam, Y. Thermo-Chemo-Mechanical Understanding of Damage Development in Porous Cementitious Materials Exposed to Sodium Chloride under Thermal Cycling. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 147, 106497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, K.; Yang, Y.; Jia, M.; Sun, F. Size Effects of Nano-Rutile TiO2 on Latent Heat Recovered of Binary Eutectic Hydrate Salt Phase Change Material. Thermochim. Acta 2020, 684, 178492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Z.; Xu, T.; Liu, C.; Zheng, Z.; Liang, L.; Hong, K. Experimental Study on Thermal Properties and Thermal Performance of Eutectic Hydrated Salts/Expanded Perlite Form-Stable Phase Change Materials for Passive Solar Energy Utilization. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 188, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Chen, X. Preparation and Thermal Properties of Eutectic Hydrate Salt Phase Change Thermal Energy Storage Material. Int. J. Photoenergy 2018, 2018, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Y. Preparation and Thermal Properties of Na2CO3·10H2O-Na2HPO4·12H2O Eutectic Hydrate Salt as a Novel Phase Change Material for Energy Storage. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 112, 606–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Y. Use of Nano-α-Al2O3 to Improve Binary Eutectic Hydrated Salt as Phase Change Material. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2017, 160, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, Q.; Lin, W.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Z. MgCl2·6H2O-Mg(NO3)2·6H2O Eutectic/SiO2 Composite Phase Change Material with Improved Thermal Reliability and Enhanced Thermal Conductivity. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2017, 172, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, K.; Alnashef, I.M.; Lin, R.J.T.; Hashim, M.A.; Mjalli, F.S.; Farid, M.M. A Novel Calcium Chloride Hexahydrate-Based Deep Eutectic Solvent as a Phase Change Materials. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 155, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Xiao, S.; Xiao, X.; Liu, Y. Preparation, Phase Diagrams and Characterization of Fatty Acids Binary Eutectic Mixtures for Latent Heat Thermal Energy Storage. Separations 2023, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrero, J.I. Application of the van’t Hoff Equation to Phase Equilibria. ChemTexts 2024, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Song, J.; Zhang, X.L.; Wu, X.; Liu, C.; Li, Y. Study on Preparation and Thermal Properties of New Inorganic Eutectic Binary Composite Phase Change Materials. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 16837–16849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmelund, H.; Boyd, B.J.; Rantanen, J.; Löbmann, K. Influence of Water of Crystallization on the Ternary Phase Behavior of a Drug and Deep Eutectic Solvent. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 315, 113727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, S.; Cazorla, C.; Romanini, M.; Tamarit, J.L.; Macovez, R. Eutectic Mixture Formation and Relaxation Dynamics of Coamorphous Mixtures of Two Benzodiazepine Drugs. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalidasan, B.; Pandey, A.K.; Mirsafi, F.S.; Leissner, T.; Rubahn, H.; Rahman, S.; Kumar, Y. Tetrapod-Engineered Eutectic Salt Hydrate Composites for Advanced Thermal Energy Storage. J. Energy Storage 2025, 124, 116680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.W.; Crimes, J.W.; Kaetzel, L. Evaluation of the Variation in the Thermal Performance in a Na2SO4·10H2O Phase Change System. Sol. Energy Mater. 1986, 13, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkawi, D.S.; Tamimi, A.I. Comparison of Phase Change Material for Thermal Analysis of a Passive Hydronic Solar System. J. Energy Storage 2021, 33, 102069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magin, R.L.; Mangum, B.W.; Statler, J.A.; Thornton, D.D. Transition Temperatures of the Hydrates of Na2SO4, Na2HPO4, and KF as Fixed Points in Biomedical Thermometry. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. 1981, 86, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Rana, M.J.; Rahman, M.M.; Dang, H.; Talukder, S.; Anzum, A. Investigating the Energy-Efficiency of Glauber’s Salt as PCM-Enhanced Mortar in Building Envelope. Adv. Build. Energy Res. 2025, 2549, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Shen, L.; Yang, Q.; Wang, K.; Wang, C. Study on the Synthesis and Thermal Properties of Magnesium Chloride Hexahydrate–Magnesium Sulfate Heptahydrate–Activated Carbon Phase Change Heat Storage Materials. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2021, 127, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Jiang, J.; Wu, H.; Hu, D.; Li, P.; Yang, X.; Jia, X. Facile Preparation of Binary Salt Hydrates/Carbon Nanotube Composite for Thermal Storage Materials with Enhanced Structural Stability. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 4561–4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Lian, P.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Sheng, X. Advanced Engineering of Binary Eutectic Hydrate Composite Phase Change Materials with Enhanced Thermophysical Performance for High-Efficiency Building Thermal Energy Storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 288, 113631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yao, J.; Min, C.; Liu, C.; Rao, Z. Investigation on Thermal Performance of Epoxy Resin Encapsulated Eutectic Hydrated Salt/Expanded Perlite Composite Phase Change Materials for Thermal Energy Storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 283, 113453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Jiang, T.; Guo, S.; Song, F.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Dong, N.; Nie, B. Research on Novel Carbon Aerogel and Eutectic Salt Hydrates as Composite Phase Change Materials: Heat Capacity, Leakage and Cycle Reliability for Thermal Energy Storage. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 699, 138159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Lan, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ran, R.; Shi, L.Y. Shape-Stable Hydrated Salts/Polyacrylamide Phase-Change Organohydrogels for Smart Temperature Management. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 21810–21821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, C.; Rao, Z. Fabrication and Thermal Properties of Composite Phase Change Materials Based on Modified Diatomite for Thermal Energy Storage. J. Energy Storage 2025, 113, 115749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xu, B.; Wang, H.; Jiu, S.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y. Fabrication of Inorganic Eutectic Salt @ SiO2 Phase Change Microcapsules and Their Influence on Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Gypsum-Based Composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 492, 142878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Zhi, M.; Cui, H.; Xu, Q.; Sun, Q.; Liu, Q. Shape-Stable Hydrated Salt Based Composite Phase Change Materials with Good Flexibility, Thermal Reliability, and Flame-Retardant Properties. J. Energy Storage 2025, 120, 116494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, R.; Raud, R.; Trout, N.; Bell, S.; Clarke, S.; Saman, W.; Bruno, F. Effect of Inner Coatings on the Stability of Chloride-Based Phase Change Materials Encapsulated in Geopolymers. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 174, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Liu, J.; Zhang, T. Developing NaAc∙3H2O-Based Composite Phase Change Material Using Glycine as Temperature Regulator and Expanded Graphite as Supporting Material for Use in Floor Radiant Heating. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 317, 113932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Tang, Y.; Liang, X.; Jin, C.; Wang, S.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Z. Thermal Properties Enhancement and Application of a Novel Sodium Acetate Trihydrate-Formamide/Expanded Graphite Shape-Stabilized Composite Phase Change Material for Electric Radiant Floor Heating. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 150, 1177–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xie, M.; Gao, X.; Yang, Y.; Sang, Y. Experimental Exploration of Incorporating Form-Stable Hydrate Salt Phase Change Materials into Cement Mortar for Thermal Energy Storage. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 140, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, W.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Z. A Polymer-Coated Calcium Chloride Hexahydrate/Expanded Graphite Composite Phase Change Material with Enhanced Thermal Reliability and Good Applicability. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2018, 156, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhou, Y.; Ling, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, X. Modification of Expanded Graphite and Its Adsorption for Hydrated Salt to Prepare Composite PCMs. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 133, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goitandia, A.M.; Beobide, G.; Aranzabe, E.; Aranzabe, A. Development of Content-Stable Phase Change Composites by Infiltration into Inorganic Porous Supports. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2015, 134, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Guo, C.; Zhang, R.; Qin, F.; Zhao, K.; Yi, H. Hectorite Aerogel Stabilized NaCl Solution as Composite Phase Change Materials for Subzero Cold Energy Storage. Miner. Miner. Mater. 2024, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitran, R.A.; Ioniţǎ, S.; Lincu, D.; Berger, D.; Matei, C. A Review of Composite Phase Change Materials Based on Porous Silica Nanomaterials for Latent Heat Storage Applications. Molecules 2021, 26, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, J.; Liu, X.; Tie, S.; Yu, P.; Wang, Y.; Ding, J. Preparation and Properties of Modified Microporous Cross-Linked Carbon Tubes-Shaped Glauber’s Salt Phase-Change Materials. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2025, 150, 12213–12221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.Z.; Qin, S.Y.; Tsui, G.C.P.; Tang, C.Y.; Ouyang, X.; Liu, J.H.; Tang, J.N.; Zuo, J.D. Fabrication, Morphology and Thermal Properties of Octadecylamine-Grafted Graphene Oxide-Modified Phase-Change Microcapsules for Thermal Energy Storage. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 157, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamekhorshid, A.; Sadrameli, S.M.; Farid, M. A Review of Microencapsulation Methods of Phase Change Materials (PCMs) as a Thermal Energy Storage (TES) Medium. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 31, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Li, Y.; Fu, M.; Liu, X.; Hu, Y.; Cheng, X. Preparation and Corrosion Study of NaOH-NaNO3 Composite Phase Change Thermal Energy Storage Material. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2026, 295, 113946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlbeck, L.; Schreiner, P.; Schlachter, K.; Dörnhofer, P.; Fasel, F.; Methner, F.J.; Rädle, M. Adjustment of Thermal Behavior by Changing the Shape of PCM Inclusions in Concrete Blocks. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 158, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Ramírez, C.; Jaramillo, F.; Gómez, M. Systematic Review of Encapsulation and Shape-Stabilization of Phase Change Materials. J. Energy Storage 2020, 30, 101495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhu, C.; Lin, Y.; Fang, G. Thermal Properties and Applications of Microencapsulated PCM for Thermal Energy Storage: A Review. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 147, 841–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasaraonaik, B.; Singh, L.P.; Sinha, S.; Tyagi, I.; Rawat, A. Studies on the Mechanical Properties and Thermal Behavior of Microencapsulated Eutectic Mixture in Gypsum Composite Board for Thermal Regulation in the Buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 31, 101400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alehosseini, E.; Jafari, S.M. Nanoencapsulation of Phase Change Materials (PCMs) and Their Applications in Various Fields for Energy Storage and Management. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 283, 102226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, H.; Batool, M.; Bolivar Osorio, F.J.; Isaza-Ruiz, M.; Xu, X.; Vignarooban, K.; Phelan, P.; Inamuddin; Kannan, A.M. Recent Developments in Phase Change Materials for Energy Storage Applications: A Review. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 129, 491–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, G.B.; Younsi, Z.; Naji, H.; Salaün, F. A Comprehensive Review of Microencapsulated Phase Change Materials Synthesis for Low-Temperature Energy Storage Applications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milián, Y.E.; Gutiérrez, A.; Grágeda, M.; Ushak, S. A Review on Encapsulation Techniques for Inorganic Phase Change Materials and the Influence on Their Thermophysical Properties. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 73, 983–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boh, B.; Sumiga, B. Microencapsulation Technology and Its Applications in Building Construction Materials. RMZ—Mater. Geoenvironment 2008, 55, 329–344. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.M.; Kim, J.S. The Microencapsulation of Calcium Chloride Hexahydrate as a Phase-Change Material by Using the Hybrid Coupler of Organoalkoxysilanes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 45821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platte, D.; Helbig, U.; Houbertz, R.; Sextl, G. Microencapsulation of Alkaline Salt Hydrate Melts for Phase Change Applications by Surface Thiol-Michael Addition Polymerization. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2013, 298, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchukina, E.M.; Graham, M.; Zheng, Z.; Shchukin, D.G. Nanoencapsulation of Phase Change Materials for Advanced Thermal Energy Storage Systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 4156–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sarkar, C.; Saha, S. From Micro to Macro: The Importance of Dimensionality in Stabilizing Phase Change Materials Based Polymer Composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2025, 307, 112914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, V.V.; Kaushik, S.C.; Tyagi, S.K.; Akiyama, T. Development of Phase Change Materials Based Microencapsulated Technology for Buildings: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 1373–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Shi, C.; Zhu, S.; Wang, B.; Hao, W.; Zou, D. Thermal Performance Enhancement of Ceramics Based Thermal Energy Storage Composites Containing Inorganic Salt/Metallic Micro-Encapsulated Phase Change Material. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 288, 113645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haoxin, C.; Yanqi, M.; Xinxin, S.; Ying, C. Achieving Heat Storage Coatings from Ethylene Vinyl Acetate Copolymers and Phase Change Nano-Capsules with Excellent Flame-Retardant and Thermal Comfort Performances. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 192, 108478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y. Preparation, Physical Property and Thermal Physical Property of Phase Change Microcapsule Slurry and Phase Change Emulsion. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2003, 80, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Stonehouse, A.; Abeykoon, C. Encapsulation Methods for Phase Change Materials—A Critical Review. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 200, 123458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Memon, S.A.; Liu, R. Development, Mechanical Properties and Numerical Simulation of Macro Encapsulated Thermal Energy Storage Concrete. Energy Build. 2015, 96, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Darkwa, J.; Kokogiannakis, G. Review of Solid-Liquid Phase Change Materials and Their Encapsulation Technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 48, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.; Shen, Z.; Kwon, S.; Toivakka, M. Thermal Properties of Graphite/Salt Hydrate Phase Change Material Stabilized by Nanofibrillated Cellulose. Cellulose 2021, 28, 6845–6856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Li, J.; Huang, K.; Bai, Y.; Wang, C. Effect of Composite Orders of Graphene Oxide on Thermal Properties of Na2HPO4∙12H2O/Expanded Vermiculite Composite Phase Change Materials. J. Energy Storage 2021, 41, 102980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, B. Interfacial Thermal Resistance: Past, Present, and Future. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2022, 94, 025002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Kumar, A.; Dhasmana, H.; Kumar, A.; Verma, A.; Shukla, P.; Jain, V.K. Effect of Shape and Size of Carbon Materials on the Thermophysical Properties of Magnesium Nitrate Hexahydrate for Solar Thermal Energy Storage Applications. J. Energy Storage 2021, 41, 102899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, D.; Dilip Saraf, S.; Gangawane, K.M. Expanded Graphite Nanoparticles-Based Eutectic Phase Change Materials for Enhancement of Thermal Efficiency of Pin–Fin Heat Sink Arrangement. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 48, 102417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Yim, Y.J.; Lee, J.W.; Heo, Y.J.; Park, S.J. Carbon-Filled Organic Phase-Change Materials for Thermal Energy Storage: A Review. Molecules 2019, 24, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.X.; Fan, Y.F.; Tao, X.M.; Yick, K.L. Crystallization and Prevention of Supercooling of Microencapsulated N-Alkanes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 281, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Yang, B. Supercooling Suppression of Microencapsulated Phase Change Materials by Optimizing Shell Composition and Structure. Appl. Energy 2014, 113, 1512–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Huang, Z.; Luo, Z.; Gao, X.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Inorganic Salt Hydrate for Thermal Energy Storage. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbu, I.; Sebarchievici, C. A Comprehensive Review of Thermal Energy Storage. Sustainability 2018, 10, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.; Lindberg, P.; Eichler, K.; Löveryd, P.; Johansson, P.; Kalagasidis, A.S. Effect of Phase Separation and Supercooling on the Storage Capacity in a Commercial Latent Heat Thermal Energy Storage: Experimental Cycling of a Salt Hydrate PCM. J. Energy Storage 2020, 29, 101266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannemand, M.; Dragsted, J.; Fan, J.; Johansen, J.B.; Kong, W.; Furbo, S. Experimental Investigations on Prototype Heat Storage Units Utilizing Stable Supercooling of Sodium Acetate Trihydrate Mixtures. Appl. Energy 2016, 169, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Dong, X.; Hou, P.; Lian, H. Preparation Research of Novel Composite Phase Change Materials Based on Sodium Acetate Trihydrate. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 118, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Zeng, J.; Zhu, S.; Song, W.; Zhou, Y.; Ren, X.; Hai, C.; Shen, Y. Low-Cost Magnesium-Based Eutectic Salt Hydrate Phase Change Material with Enhanced Thermal Performance for Energy Storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2022, 238, 111620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, R.; Iqbal, M.I.; Farnam, Y. Evaluating Long-Term Thermal and Chemical Stability and Leaching Potential of Low-Temperature Phase Change Materials in Concrete Slabs Exposed to Outdoor Environmental Conditions. Mater. Struct. Constr. 2025, 58, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Year | Theoretical Model | Experimental Model | Statistical Analysis | Durability Tests | Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [25] | 2024 | √ | Low | |||

| [26] | 2024 | √ | √ | √ | Medium | |

| [27] | 2024 | √ | Low | |||

| [28] | 2023 | √ | √ | √ | Medium | |

| [29] | 2023 | √ | √ | √ | Medium | |

| [30] | 2023 | √ | √ | Medium | ||

| [31] | 2023 | √ | √ | √ | Medium | |

| [32] | 2023 | √ | √ | Medium | ||

| [33] | 2023 | √ | √ | Medium | ||

| [34] | 2022 | √ | √ | Medium | ||

| [35] | 2022 | √ | Low | |||

| [36] | 2022 | √ | √ | Medium | ||

| [37] | 2022 | √ | Low | |||

| [38] | 2022 | √ | √ | Medium | ||

| [39] | 2021 | √ | √ | Medium | ||

| [40] | 2021 | √ | Low | |||

| [41] | 2021 | √ | √ | Medium | ||

| [42] | 2020 | √ | Low | |||

| [43] | 2020 | √ | √ | Medium | ||

| [44] | 2020 | √ | √ | Medium | ||

| [45] | 2020 | √ | √ | Medium | ||

| [46] | 2020 | √ | √ | √ | Medium | |

| [17] | 2018 | √ | √ | Medium | ||

| [47] | 2018 | √ | √ | Medium | ||

| [48] | 2018 | √ | √ | √ | √ | High |

| [49] | 2017 | √ | Low | |||

| [50] | 2017 | √ | √ | √ | √ | High |

| [51] | 2017 | √ | √ | Medium | ||

| [52] | 2016 | √ | √ | Medium |

| Advantages | Disadvantages | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Encapsulation | nano (1–1000 nm) | Controlled thermal energy release. | Increase in thermal conductivity. |

| Prevention of material exchange with environment. | Nanoparticles are susceptible to instability and agglomeration. | ||

| Protection against degradation during heat uptake/release cycles. | Difficult to scale-up. | ||

| The possibility to use the capsules in powder or paste form as additives to convenient materials (concrete, foam, paint, etc.). | It is complicated and costly. | ||

| Smaller capsules greatly increase the surface area to volume ratio of the material, which improves heat transfer. | |||

| Encapsulating PCMs in capsules of 1 mm in size would increase the surface area by 300 m2 m−3 when compared with the bulk PCM Reducing their diameter to the nanometer range would vastly enhance this effect. | |||

| Prevention of both leakage and reactions with the external environment. | |||

| Corrosion protection for container materials | |||

| It is also possible to form a composite polymer/inorganic shell combining advantages of each. | |||

| Increment in the reliability (charging-discharging cycle life). | |||

| It is one of the most promising solutions to increase the efficiency of PCMs, both organic and inorganic. | |||

| micro (1–1000 µm) | Microcapsules with impermeable walls are used in products where isolation of active substances is needed. | The degree of supercooling is strongly dependent on the morphology and component of shell material. | |

| PCMs with a melting point ranging from −10 to 80 °C can be microencapsulated. | The leaching of the functional core PCM in microencapsulation. | ||

| The effects achieved with impermeable microcapsules include separation of reactive components, protection of sensitive substances against environmental effects, reduced volatility of highly volatile substances, and conversion of liquid ingredients into a solid state and toxicity reduction. | The high surface polarities of these substances, edge alignment effects, and their tendency to alter their water content. | ||

| Control the changes in the volume as phase change occurs. | Difficult to scale up. | ||

| Controlled release of thermal energy. | It is complicated and costly. | ||

| macro (>1000 µm) | Macroencapsulations are easier to include and therefore cheaper to produce and should be better in case of natural convection with a smaller heat transfer surface compared to the PCM mass. | A lower thickness improves the crystallization time but simultaneously increases the melting time. | |

| Macroencapsulated salt hydrates are up to three to four times cheaper than microencapsulated paraffins. | Cuboid shapes are easy to produce but have a low heat transfer owing to a thick PCM layer. | ||

| A spherical shape shows the fastest melting time because of an even distribution combined with a large heat transfer surface. | Macroencapsulation produces a much simpler structure but uses hard shells (such as metals) to avoid shape deforming once the solid melts into a liquid | ||

| It requires the modification of the traditional construction process. | The heavy shells lower the energy storage density and increase the costs. | ||

| Metal capsules have corrosion problems. | |||

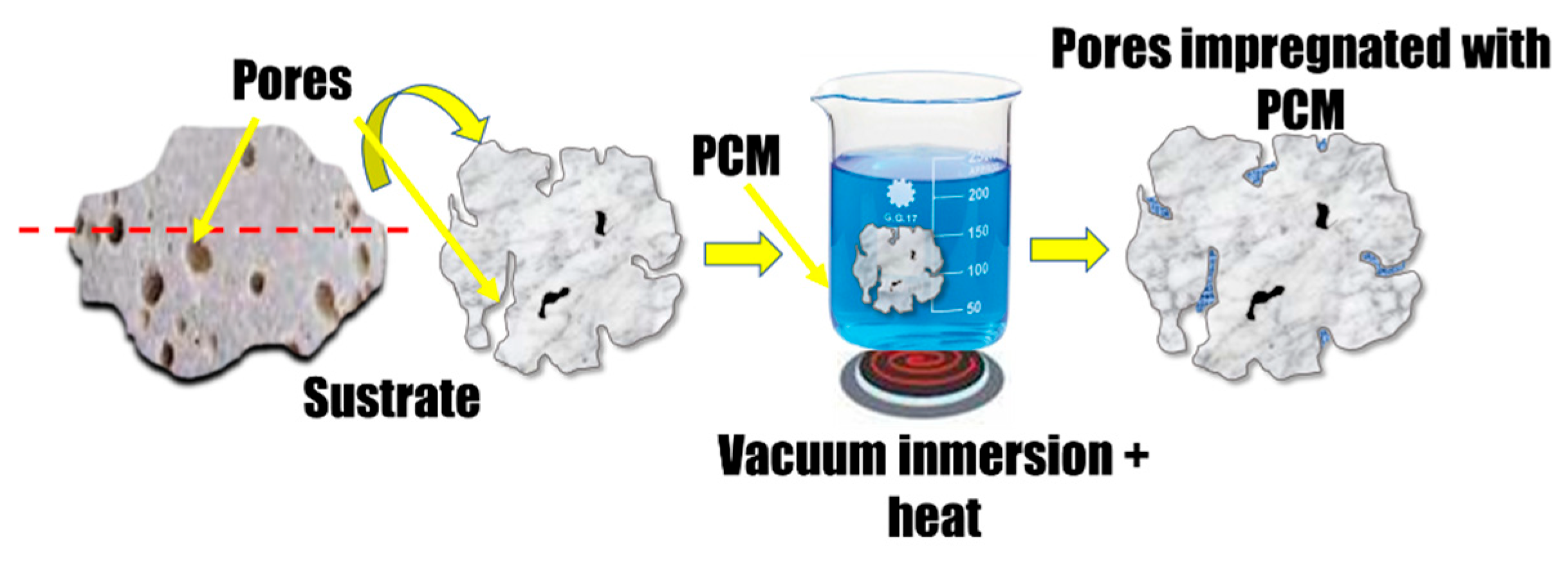

| Porous substrate | The micropore can absorb PCMs with capillary force, thus keeping the composite free of liquid leakage, reducing the sub-cooling degree of PCMs, and alleviating the phase separation. | There is still one problem that microimpregnation with porous matrices cannot correct dehydration. Hydrated salts dehydrate once phase change begins. If the water leaves from the hydrates as a vapor, the composition of the hydrated salts changes, which also changes the phase change characteristics. | |

| Applying vacuum impregnation, the process effectively removed air from the porous, allowing for deep and uniform infiltration of PCM | Composites prepared from conventional porous materials such as bentonite, zeolites, diatomaceous earth and expanded graphite, might present an initially appealing latent heat, they suffer a considerable amount of PCM leakage caused by exudation from the macropores and the inter-granular space during thermal cycling. | ||

| The microporous structure provides a large specific surface area. | The exudation problems of in use conditions. | ||

| Optimization of pore structure may enhance thermal storage and mechanical properties | |||

| The hydrophilicity of the porous matrix has a considerable impact on the adsorption capacity of hydrates. | |||

| It can be complemented with some form of encapsulation technique. | |||

| Low cost, ease of fabrication and widespread application. | |||

| Physical Methods | Physic-Chemical Methods | Chemical Methods |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| PCM | Nucleating Agent | Addition wt% | Melting Point °C | Enthalpy J·g−1 | Supercooling °C | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na2HPO4·12H2O/Na2S2O3·5H2O | Na2SiO3·9H2O | 3.0 | 26.1 | 134.5 | 2.3 | [65] |

| NaAc∙3H2O/ NH2CH2COOH | Borax | 0.5 | 48.62 | 258.5 | 1.49 | [73] |

| CH3COONa·3H2O/Na2S2O3·5H2O | SrCl2·6H2O | 2.0 | 41.45 | 186.6 | 0.462 | [20] |

| Na2 SO4·10H2O/Na2HPO4·12H2O | Nanometer AlN, Borax | 1.8 | 180.2 | 3.1 | [36] | |

| 1.5 | ||||||

| Na2SO4·10H2O/Na2HPO4·12H2O | Borax | 1 | 42.2 | 149.3 | 7.7 | [28] |

| Na2SO4·10H2O/Na2HPO4·12H2O | Borax | 0.3 | 209.5 | 3.4 | [26] | |

| 0.6 | 209.0 | 5 | ||||

| 0.9 | 215.5 | 4.5 | ||||

| 1.2 | 207.5 | 4.2 | ||||

| MgCl2·6H2O/ Mg(NO3)2·6H2O | Sr(OH)2·8H2O | 0.5 | 60 | 139.5 | 1 | [118] |

| NaH2PO4·2H2O/Na2S2O3·5H2O/K2HPO4·3H2O | Nanoactivatedcarbon/Sodiumtetraborate/Sodiumfluoride | 0 | 11.9 | 127.2 | 1.5 | [48] |

| 3 | 10.6 | 118.6 | ||||

| 5 | 14.8 | 82.56 | ||||

| Na2SO4·10H2O/Na2HPO4·12H2O | Nano-α-Al2O3/Borax | 3 | 31.2 | 280.1 | 1 | [50] |

| 1 | ||||||

| Na2HPO4·12H2O | Na2SiO3·9H2O | 30.4 | 163.4 | 1.3 | [5] | |

| Na2HPO4·12H2O | Na2SiO3·9H2O | 2 | 28.9 | 153.1 | 3.7 | [4] |

| 3 | 2.0 | |||||

| 4 | 2.7 | |||||

| 5 | 0.8 | |||||

| 6 | 2.4 | |||||

| 7 | 1.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cervantes Ramírez, E.M.; Trejo Arroyo, D.; Argüello, J.C.C.; Pamplona Solís, B.B.; Nahuat Sansores, J.R. Advances in the Stabilization of Eutectic Salts as Phase Change Materials (PCMs) for Enhanced Thermal Performance: A Critical Review. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120667

Cervantes Ramírez EM, Trejo Arroyo D, Argüello JCC, Pamplona Solís BB, Nahuat Sansores JR. Advances in the Stabilization of Eutectic Salts as Phase Change Materials (PCMs) for Enhanced Thermal Performance: A Critical Review. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):667. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120667

Chicago/Turabian StyleCervantes Ramírez, Elmer Marcial, Danna Trejo Arroyo, Julio César Cruz Argüello, Blandy Berenice Pamplona Solís, and Javier Rodrigo Nahuat Sansores. 2025. "Advances in the Stabilization of Eutectic Salts as Phase Change Materials (PCMs) for Enhanced Thermal Performance: A Critical Review" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120667

APA StyleCervantes Ramírez, E. M., Trejo Arroyo, D., Argüello, J. C. C., Pamplona Solís, B. B., & Nahuat Sansores, J. R. (2025). Advances in the Stabilization of Eutectic Salts as Phase Change Materials (PCMs) for Enhanced Thermal Performance: A Critical Review. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120667