A Study on the Adsorption of Cd(II) in Aqueous Solutions by Fe-Mn Oxide-Modified Algal Powder Gel Beads

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Reagents and Instruments

2.2. Preparation of Fe-Mn-Modified Algal Powder Gel Beads

2.3. Material Characterization

2.4. Adsorption Experiment

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optimization of Conditions for Preparation

3.2. Morphology and Properties of Fe-Mn-Modified Algal Powder Gel Beads

3.3. Effect of pH

3.4. Effect of Dosage and Reaction Time

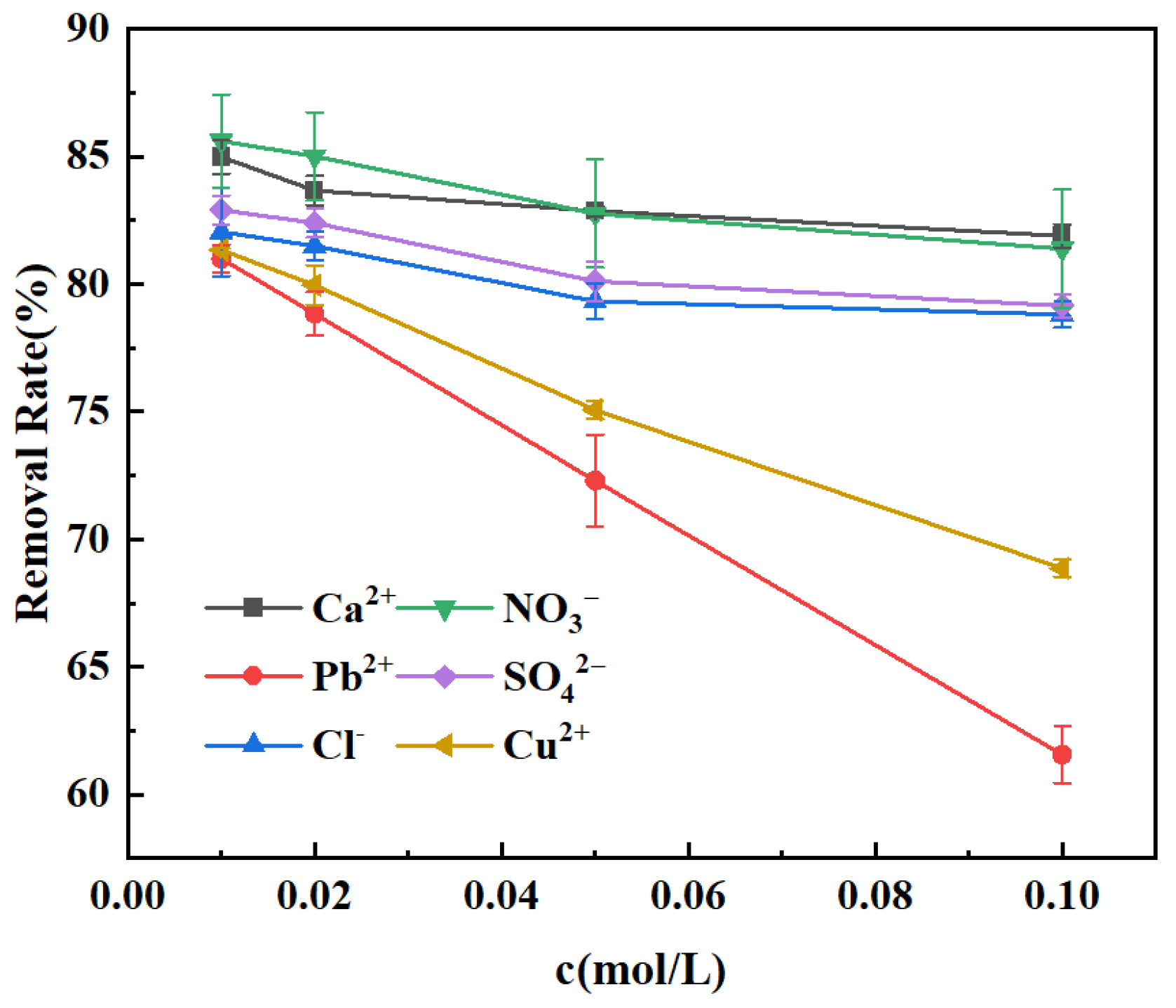

3.5. Effect of Co-Existing Ions

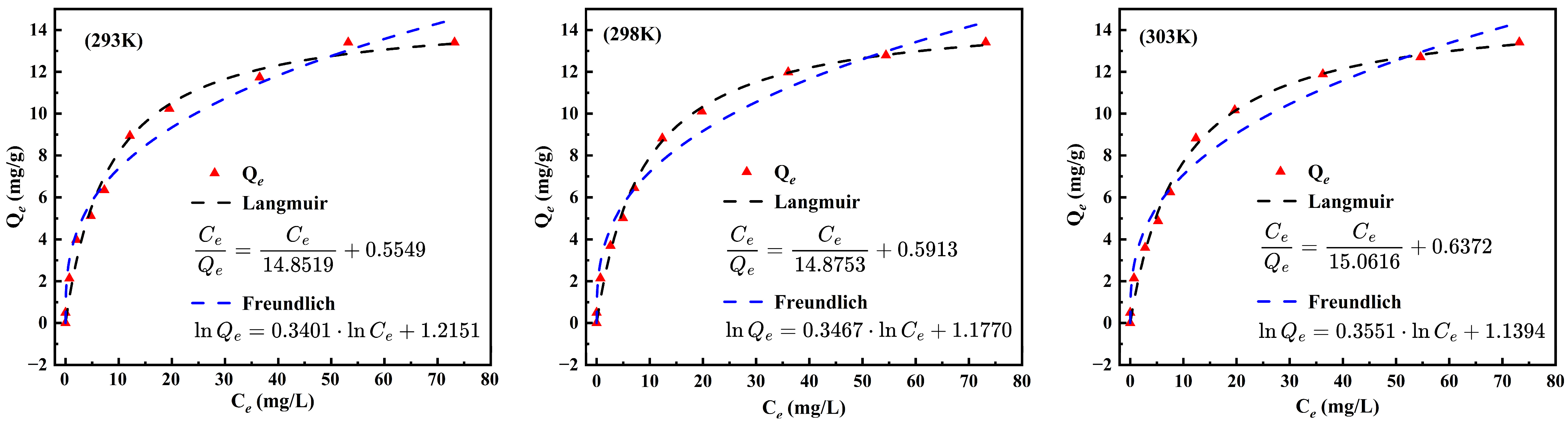

3.6. Isothermal Adsorption Modeling and Adsorption Kinetics Studies

3.7. Adsorption Mechanism Analysis

3.8. Desorption Characteristics

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deng, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhuo, R. Recent advances in phyto-combined remediation of heavy metal pollution in soil. Biotechnol. Adv. 2024, 72, 108337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Dwivedi, S.K.; Oh, S. A review on microbial-integrated techniques as promising cleaner option for removal of chromium, cadmium and lead from industrial wastewater. J. Water Process. Eng. 2022, 47, 102727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Hao, H.; Cui, J.; Huang, L.; Liang, Q. The association between cadmium exposure and the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 469, 133828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doccioli, C.; Sera, F.; Francavilla, A.; Cupisti, A.; Biggeri, A. Association of cadmium environmental exposure with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, Y.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Q.; Ning, Z.; Yu, Y.; Li, Y. Urinary cadmium in relation to bone damage: Cadmium exposure threshold dose and health-based guidance value estimation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 226, 112824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, S.; Xie, Y.; Liu, H.; Hu, Y.; Li, Y. Variations in cadmium and lead bioaccessibility and human health risk assessment from ingestion of leafy vegetables: Focus on the involvement of gut microbiota. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 141, 107353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Song, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Tao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Z. Simultaneous scavenging of Cd(II) and Pb(II) from water by sulfide-modified magnetic pinecone-derived hydrochar. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 341, 130758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Zhuang, S.; Wang, J. Adsorption of heavy metals by biochar in aqueous solution: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 968, 178898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Fu, D.; Hu, W.; Lu, X.; Wu, Y.; Bryan, H. Physiological responses and accumulation ability of Microcystis aeruginosa to zinc and cadmium: Implications for bioremediation of heavy metal pollution. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 303, 122963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkarim, M.S.; Ali, M.H.H.; Kassem, D.A. Ecofriendly remediation of cadmium, lead, and zinc using dead cells of Microcystis aeruginosa. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; He, Y.; Liang, D.; Wang, F.; Luo, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Gao, P.; Wen, X.; et al. Adsorption of Heavy Metal Ions Copper, Cadmium and Nickel by Microcystis aeruginosa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.Y.; Show, P.; Lau, B.F.; Chang, J.; Ling, T.C. New Prospects for Modified Algae in Heavy Metal Adsorption. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1255–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Qi, J.; Ji, Q.; Lan, H.; Liu, H.; Qu, J. Fabrication of iron-manganese oxide composite modified Microcystis aeroginosa adsorbent for advanced antimony removal. Chin. J. Environ. Eng. 2019, 13, 1573–1583. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monica, P. Treatment of Wastewaters with Zirconium Phosphate Based Materials: A Review on Efficient Systems for the Removal of Heavy Metal and Dye Water Pollutants. Molecules 2021, 26, 2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Kuang, S.; Kang, Y.; Ma, H.; Dong, J.; Guo, Z. Recent advances in application of iron-manganese oxide nanomaterials for removal of heavy metals in the aquatic environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 819, 153157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohaeti, E.; Helmiyati; Joronavalona, R.; Taba, P.; Sondari, D.; Kamari, A. The Role of Brown Algae as a Capping Agent in the Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles to Enhance the Antibacterial Activities of Cotton Fabrics. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Guo, C.; Hao, J.; Zhao, Z.; Long, H.; Li, M. Adsorption of heavy metal ions by sodium alginate based adsorbent-a review and new perspectives. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 4423–4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Long, A.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, S.; et al. Recent advances in alginate-based hydrogels for the adsorption-desorption of heavy metal ions from water: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 353, 128265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovič, A.; Simonič, M. Removal of heavy metal ions from drinking water by alginate-immobilised Chlorella sorokiniana. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 13, 1761–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Liu, R.; Wang, H. Unraveling adsorption characteristics and removal mechanism of novel Zn/Fe-bimetal-loaded and starch-coated corn cobs biochar for Pb(II) and Cd(II) in wastewater. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 391, 123375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, M.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L. Preparation of a novel hydrogel of sodium alginate using rural waste bone meal for efficient adsorption of heavy metals cadmium ion. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 863, 160969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ou, J.; Wang, B.; Wang, H.; He, Q.; Song, J.; Zhang, H.; Tang, M.; Zhou, L.; Gao, Y.; et al. Efficient heavy metal removal from water by alginate-based porous nanocomposite hydrogels: The enhanced removal mechanism and influencing factor insight. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 418, 126358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.H.; Shah, N.S.; Khan, G.A.; Sarfraz, S.; Iqbal, J.; Jwuiyad, A.; Shahida, S.; Han, C.; Wawrzkiewicz, M. The Cr(III) Exchange Mechanism of Macroporous Resins: The Effect of Functionality and Chemical Matrix, and the Statistical Verification of Ion Exchange Data. Water 2023, 15, 3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, H. Enhanced adsorption performance of tetracycline in aqueous solutions by methanol-modified biochar. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 248, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Lan, C.Q. Effects of culture pH on cell surface properties and biosorption of Pb(II), Cd(II), Zn(II) of green alga Neochloris oleoabundans. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 468, 143579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarada, B.; Prasad, M.K.; Kumar, K.K.; Ramachandra Murthy, C.V. Cadmium removal by macro algae Caulerpa fastigiata: Characterization, kinetic, isotherm and thermodynamic studies. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 1533–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, M.; He, J.; Long, F.; Wang, Y. Low-cost preparation of ethylene glycol-modified micro-nano porous calcium carbonate with excellent removal of Cadmium in wastewater. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 38, 104105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, A.; Tuzen, M. Biosorption of Pb(II) and Cd(II) from aqueous solution using green alga (Ulva lactuca) biomass. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 152, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Huang, H.; Zhao, D.; Lin, J.; Gao, P.; Yao, L. Adsorption of Pb2+ onto freeze-dried microalgae and environmental risk assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 265, 110472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Zhao, M.; Ma, D.; Sun, Z.; Hu, J. Poly (acrylamide-co-2-acrylamido-2-methylpropane sulfonic acid)-g-carboxymethylcellulose-Ca(II) hydrogel beads for efficient adsorption of Cd(II). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 306 Pt 2, 141498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Jiang, H.; Lin, Z.; Xu, S.; Xie, J.; Zhang, A. Preparation of acrylamide/acrylic acid cellulose hydrogels for the adsorption of heavy metal ions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 224, 115022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Rao, D.; Zou, L.; Teng, Y.; Yu, H. Capacity and potential mechanisms of Cd(II) adsorption from aqueous solution by blue algae-derived biochars. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 767, 145447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Yin, H.; Yuan, Y.; Ouyang, X.; Lou, K. Simultaneously enhancing the efficiency of As(III) and Cd removal by iron-modified biochar: Oxidative enhancement, and selective adsorption of As(III). J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; He, E.; Jiang, X.; Xia, S.; Yu, L. Efficient removal of direct dyes and heavy metal ion by sodium alginate-based hydrogel microspheres: Equilibrium isotherms, kinetics and regeneration performance study. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 294, 139294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Wang, E. Adsorption and Recovery Studies of Cadmium and Lead Ions Using Biowaste Adsorbents from Aqueous Solution. Separations 2025, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, W. A novel modified method for the efficient removal of Pb and Cd from wastewater by biochar: Enhanced the ion exchange and precipitation capacity. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 142150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirbaz, M.; Roosta, A. Adsorption, kinetic and thermodynamic studies for the biosorption of cadmium onto microalgae Parachlorella sp. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 2302–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Aty, A.M.; Ammar, N.S.; Abdel Ghafar, H.H.; Ali, R.K. Biosorption of cadmium and lead from aqueous solution by fresh water alga Anabaena sphaerica biomass. J. Adv. Res. 2013, 4, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Bing, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, K.; Wei, L.; Jiang, J.; Ding, J.; Jiang, M.; Xue, R. Synthesis of MnFe2O4-biochar with surficial grafting hydroxyl for the removal of Cd(II)-Pb(II)-Cu(II) pollutants: Competitive adsorption, application prospects and binding orders of functional groups. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 375, 124280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arafa, E.G.; Mahmoud, R.; Gadelhak, Y.; Gawad, O.F.A. Design, preparation, and performance of different adsorbents based on carboxymethyl chitosan/sodium alginate hydrogel beads for selective adsorption of Cadmium (II) and Chromium (III) metal ions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 273, 132809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milojković, J.V.; Lopičić, Z.R.; Anastopoulos, I.P.; Petrović, J.T.; Milićević, S.Z.; Petrović, M.S.; Stojanović, M.D. Performance of aquatic weed—Waste Myriophyllum spicatum immobilized in alginate beads for the removal of Pb(II). J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 232, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuat, G.; Cumali, Y. Synthesis, characterization, and lead(II) sorption performance of a new magnetic separable composite: MnFe2O4@wild plants-derived biochar. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 104567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Ye, S.; Yang, H.; Yang, K.; Zhou, J.; Gao, Y.; Lin, Q.; Tan, X.; Yang, Z. Application of layered double hydroxide-biochar composites in wastewater treatment: Recent trends, modification strategies, and outlook. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 420, 126569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Yin, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Z.; Lin, Y.; Wang, L. Study on the mechanism of biochar loaded typical microalgae Chlorella removal of cadmium. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 813, 152488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Teng, C.; Yu, S.; Song, T.; Dong, L.; Liang, J.; Bai, X.; Liu, X.; Hu, X.; Qu, J. Batch and fixed-bed biosorption of Cd(II) from aqueous solution using immobilized Pleurotus ostreatus spent substrate. Chemosphere 2018, 191, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Kang, G.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, J.; Xie, W.; Liu, Z.; Xu, L.; Hu, F.; Li, Z.; Li, H. Biochar loaded with ferrihydrite and Bacillus pseudomycoides enhances remediation of co-existed Cd(II) and As(III) in solution. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 395, 130323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinza, L.; Geraki, K.; Matamoros-Veloza, A.; Ignat, M.; Neamtu, M. The Irish kelp, Fucus vesiculosus, a highly potential green bio sorbent for Cd (II) removal: Mechanism, quantitative and qualitative approaches. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 327, 129422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y. Fabrication and application of magnetic MgFe2O4-OH@biochar composites decorated with β-ketoenamine for Pb(II) and Cd(II) adsorption and immobilization from aqueous solution. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 129320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Hu, J.; Yu, Y.; Ma, D.; Gong, W.; Qiu, H.; Hu, Z.; Gao, H. Facile preparation of sulfonated biochar for highly efficient removal of toxic Pb(II) and Cd(II) from wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 750, 141545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Jiang, S.G.; Liang, K.; Yang, Z.Z.; Xu, Y.M. Remediation Effect of Iron-manganese Composite-modified Biochar from Different Biomasses on Cd-contaminated Alkaline Soil. Environ. Sci. 2025, 46, 461–469. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerulová, K.; Bartošová, A.; Blinová, L.; Bártová, K.; Dománková, M.; Garaiová, Z.; Palcut, M. Magnetic Fe3O4-polyethyleneimine nanocomposites for efficient harvesting of Chlorella zofingiensis, Chlorella vulgaris, Chlorella sorokiniana, Chlorella ellipsoidea and Botryococcus braunii. Algal. Res. 2018, 33, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, F.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Chen, L. Simple hydrothermal synthesis of magnetic MnFe2O4-sludge biochar composites for removal of aqueous Pb2+. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2021, 156, 105173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Li, Y.; Cheng, S.; Wu, G.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, L. Cadmium removal by FeOOH nanoparticles accommodated in biochar: Effect of the negatively charged functional groups in host. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 421, 126807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.K.; Kumar, K.; Prasad, T.; Rai, S.; Chaudhary, A.; Tungala, K.; Das, A. Fabrication of cationic microgels doped MnO2/Fe3O4 nanocomposites, and study of their photocatalytic performance and reusability in organic transformations. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2024, 35, e6295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Shao, J.; Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, W. Direct Z-scheme CdFe2O4/g-C3N4 hybrid photocatalysts for highly efficient ceftiofur sodium photodegradation. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 56, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specific Surface Area | Pore Volume | Average Pore Diameter | |

|---|---|---|---|

| m2/g | cm3/g | nm | |

| Before adsorption | 9.3878 | 0.0077 | 4.6036 |

| After adsorption | 7.1677 | 0.0097 | 6.2373 |

| T/K | Langmuir | Freundlich | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qm | KL | RL | R2 | KF | 1/n | R2 | |

| 293 | 14.8519 | 0.12133 | 0.8917 | 0.9757 | 3.3705 | 0.3401 | 0.9768 |

| 298 | 14.8753 | 0.1137 | 0.8979 | 0.9885 | 3.2446 | 0.3467 | 0.9749 |

| 303 | 15.0616 | 0.1042 | 0.9056 | 0.9856 | 3.1249 | 0.3551 | 0.9711 |

| Pseudo-First-Order | Pseudo-Second-Order | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k1 | qe | R2 | k2 | qe | R2 |

| 0.1871 | 13.6401 | 0.9938 | 1.599 | 13.6623 | 0.9965 |

| Surface Diffusion | Internal Diffusion | ||||

| kp | Cp | R2 | kp | Cp | R2 |

| 7.7189 | 1.300 | 0.9180 | 0.3213 | 12.6502 | 0.7888 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, S.; Peng, Z.; Zou, J.; Qin, J.; Deng, R.; Wang, C.; Peng, Y.; Hursthouse, A.; Deng, M. A Study on the Adsorption of Cd(II) in Aqueous Solutions by Fe-Mn Oxide-Modified Algal Powder Gel Beads. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9110606

Zhou S, Peng Z, Zou J, Qin J, Deng R, Wang C, Peng Y, Hursthouse A, Deng M. A Study on the Adsorption of Cd(II) in Aqueous Solutions by Fe-Mn Oxide-Modified Algal Powder Gel Beads. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(11):606. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9110606

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Saijun, Zixuan Peng, Jiarong Zou, Jinsui Qin, Renjian Deng, Chuang Wang, Yazhou Peng, Andrew Hursthouse, and Mingjun Deng. 2025. "A Study on the Adsorption of Cd(II) in Aqueous Solutions by Fe-Mn Oxide-Modified Algal Powder Gel Beads" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 11: 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9110606

APA StyleZhou, S., Peng, Z., Zou, J., Qin, J., Deng, R., Wang, C., Peng, Y., Hursthouse, A., & Deng, M. (2025). A Study on the Adsorption of Cd(II) in Aqueous Solutions by Fe-Mn Oxide-Modified Algal Powder Gel Beads. Journal of Composites Science, 9(11), 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9110606