Unveiling the Responses’ Feature of Composites Subjected to Fatigue Loadings—Part 1: Theoretical and Experimental Fatigue Response Under the Strength-Residual Strength-Life Equal Rank Assumption (SRSLERA) and the Equivalent Residual Strength Assumption (ERSA)

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The CA fatigue life cumulative distribution function (CDF) as a function of the applied maximum stress;

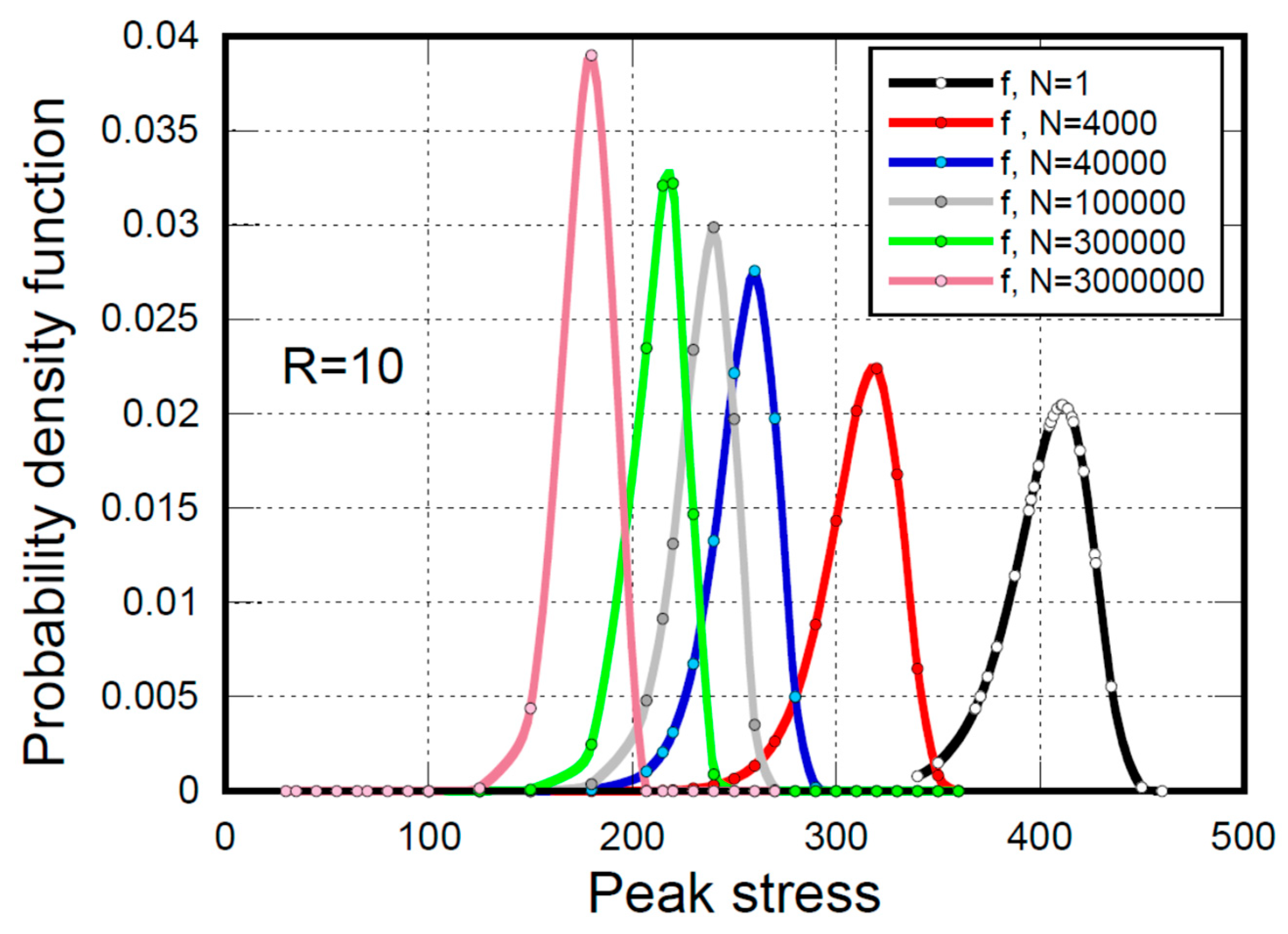

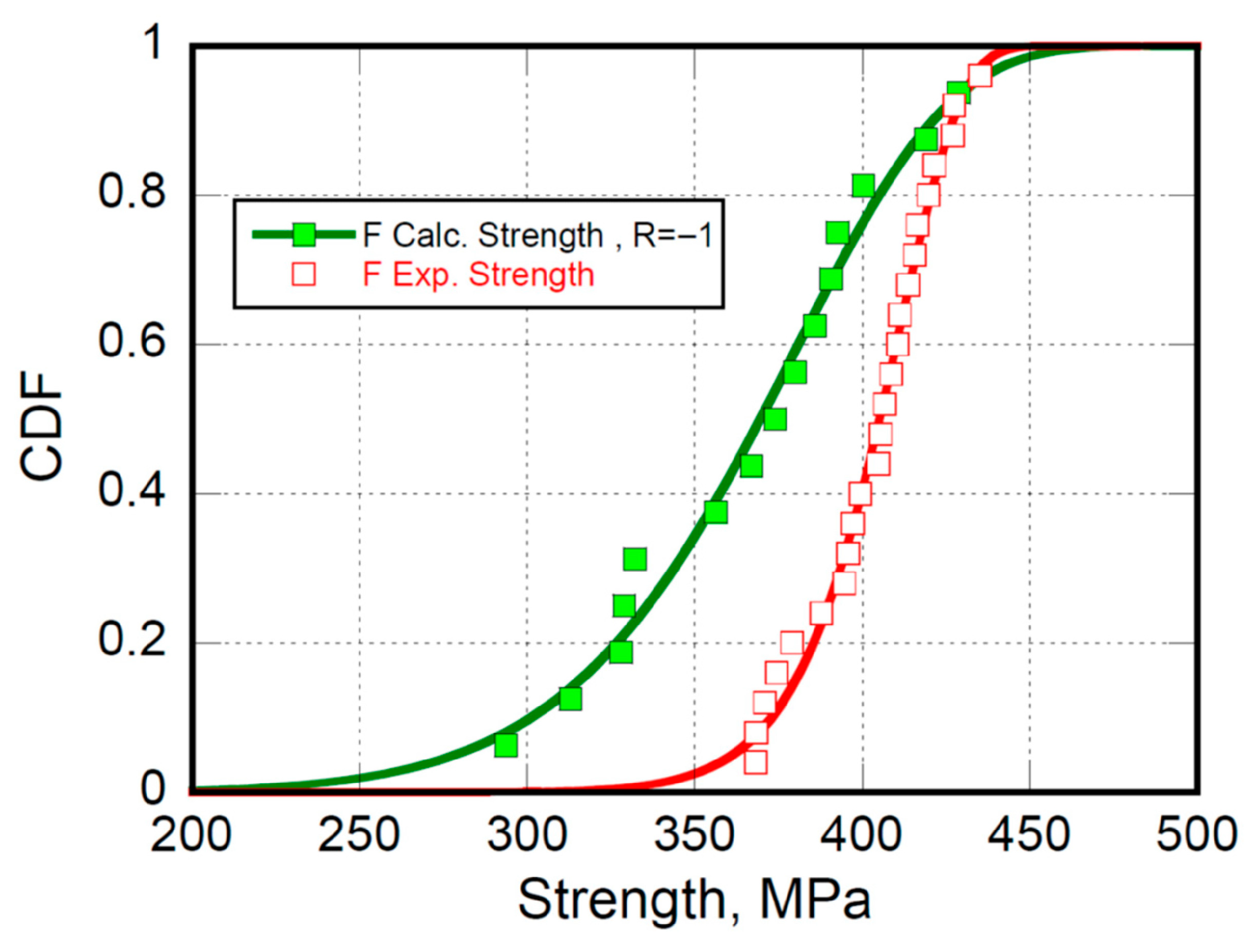

- The lifetime probability density function (PDF) as a function of the number of cycles;

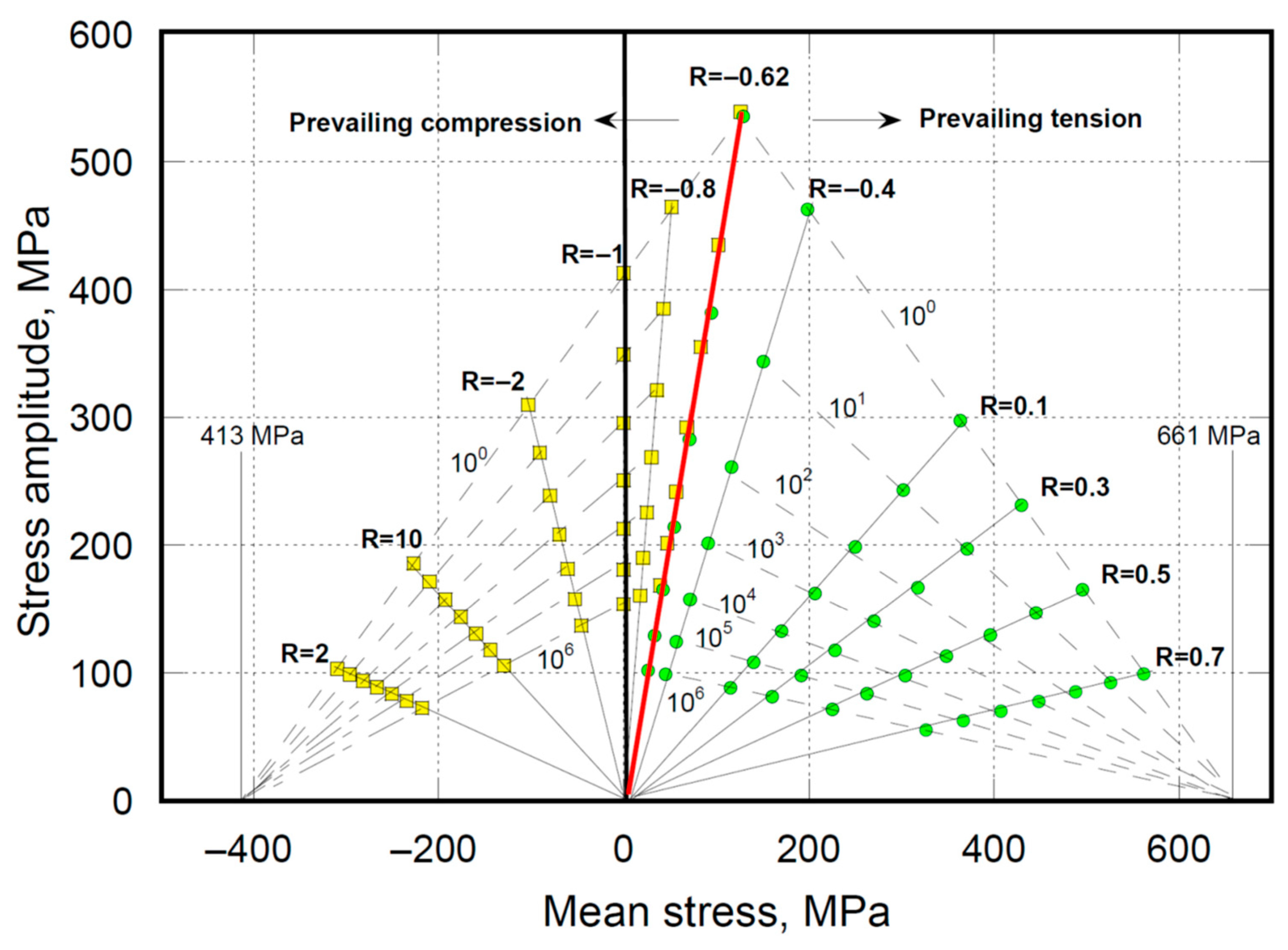

- The constant life diagram (CLD);

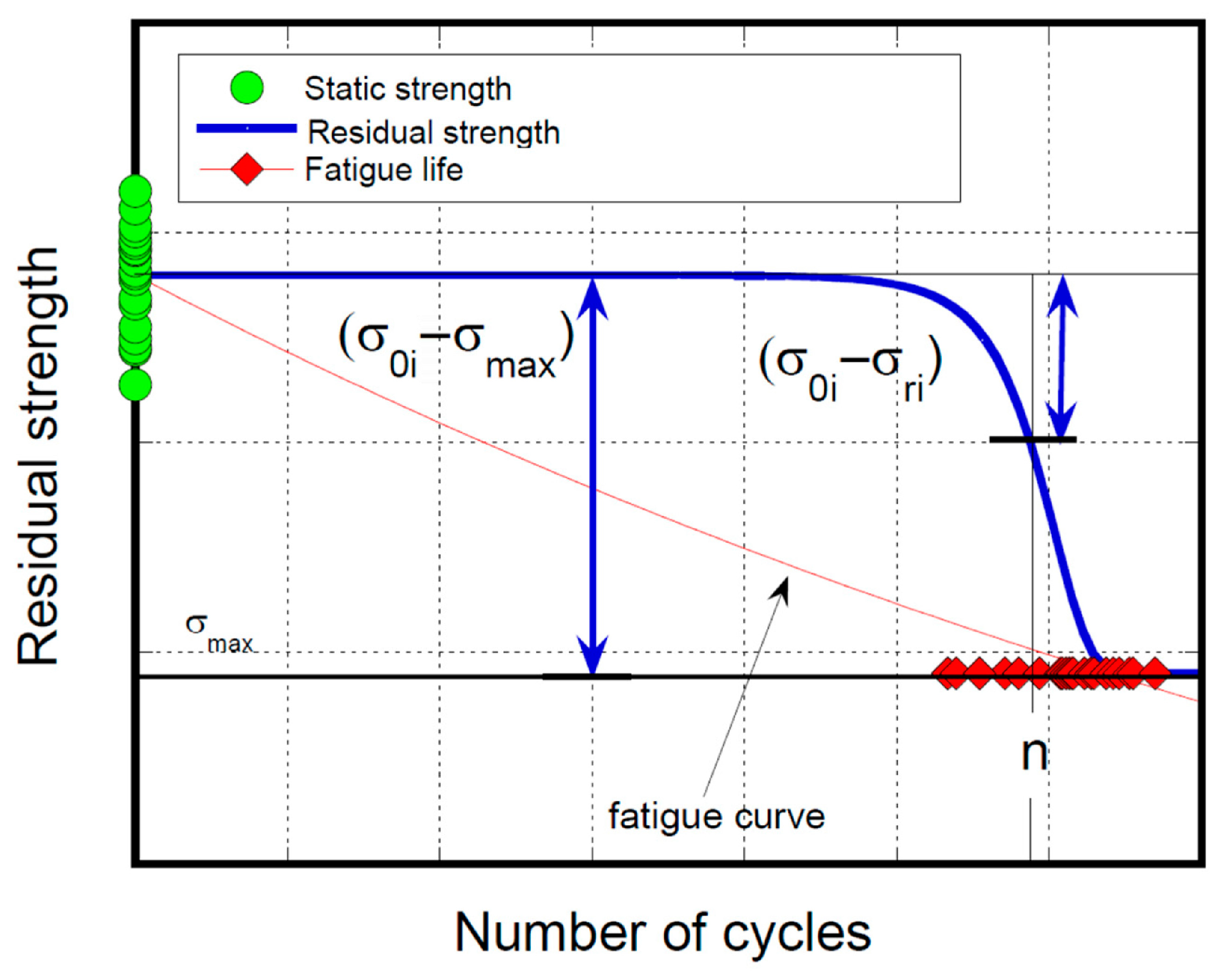

- The residual strength statistics;

- The statistical lifetime predictions based on a strength-based damage rule accounting for the block extent and sequence effects.

2. Materials and Testing

3. Analytical Background

4. Results and Discussion

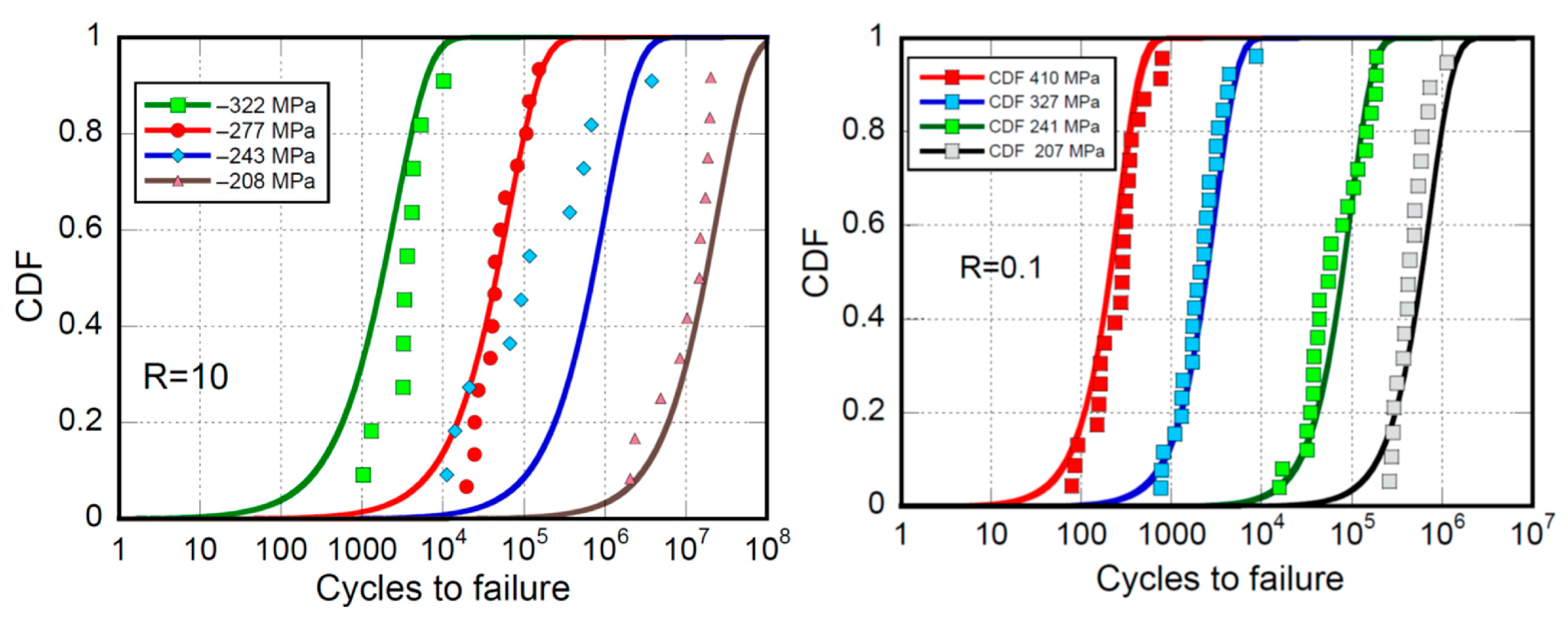

4.1. Constant Amplitude (CA) Fatigue Modeling

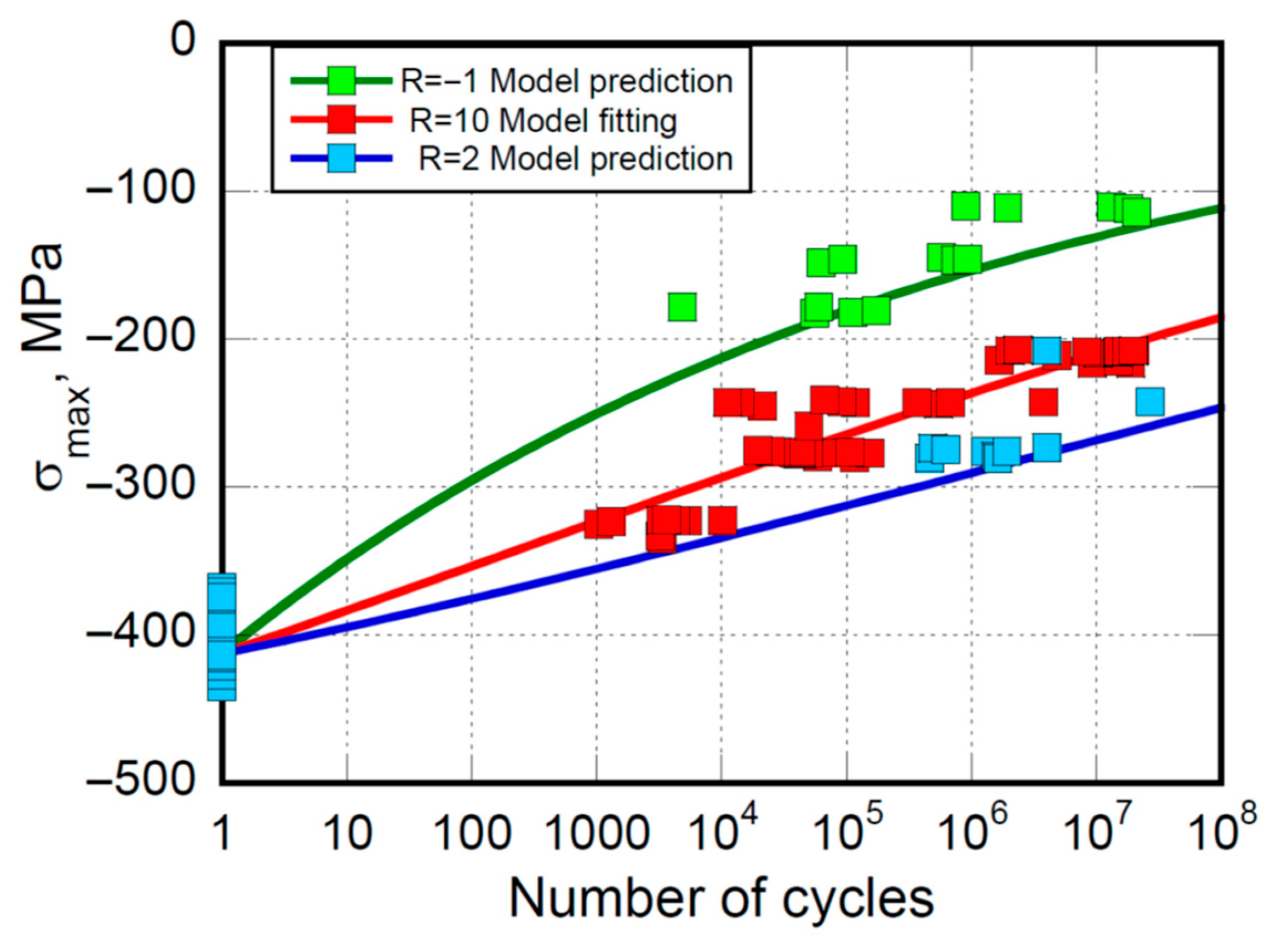

4.2. Constant Life Diagram (CLD)

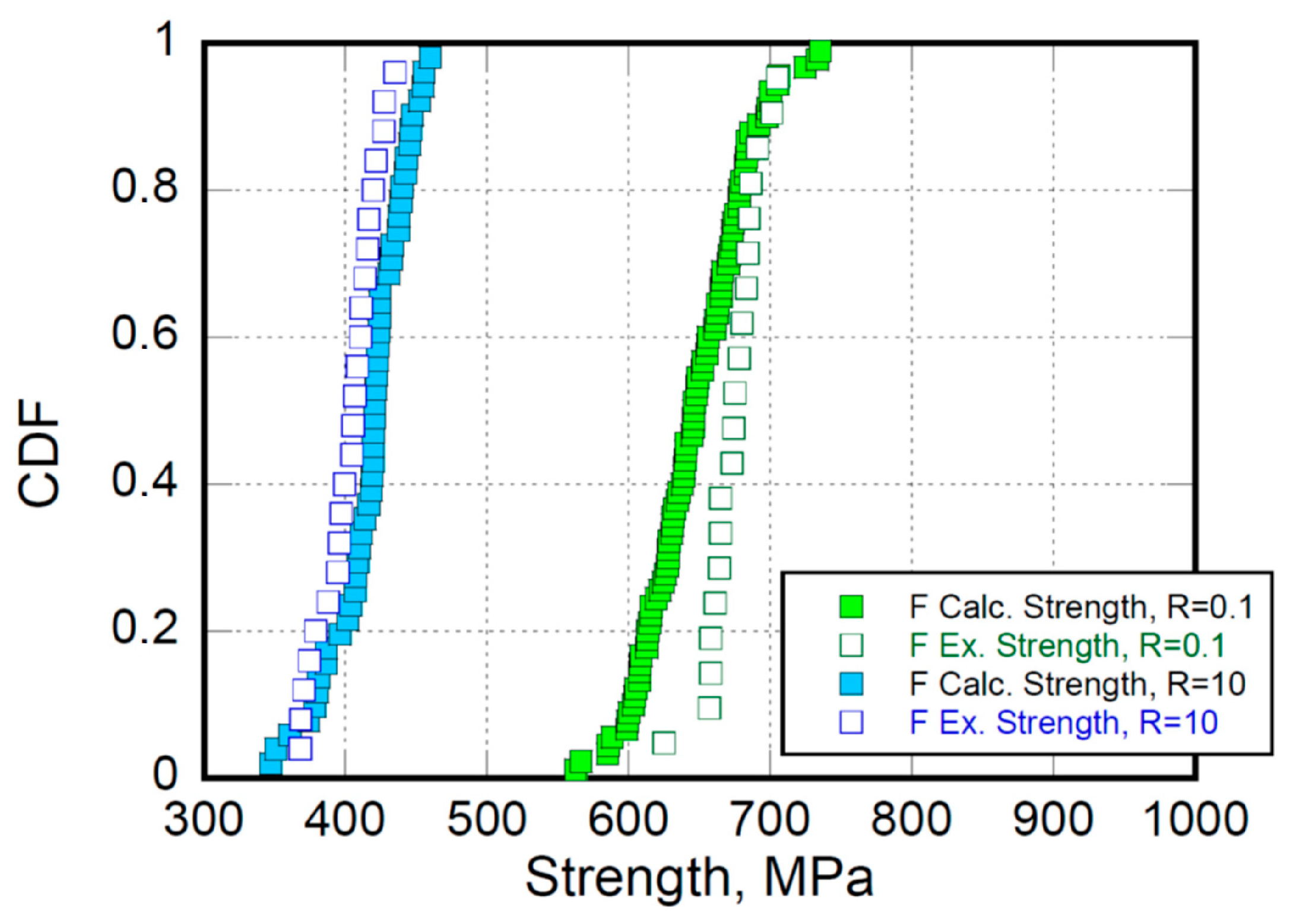

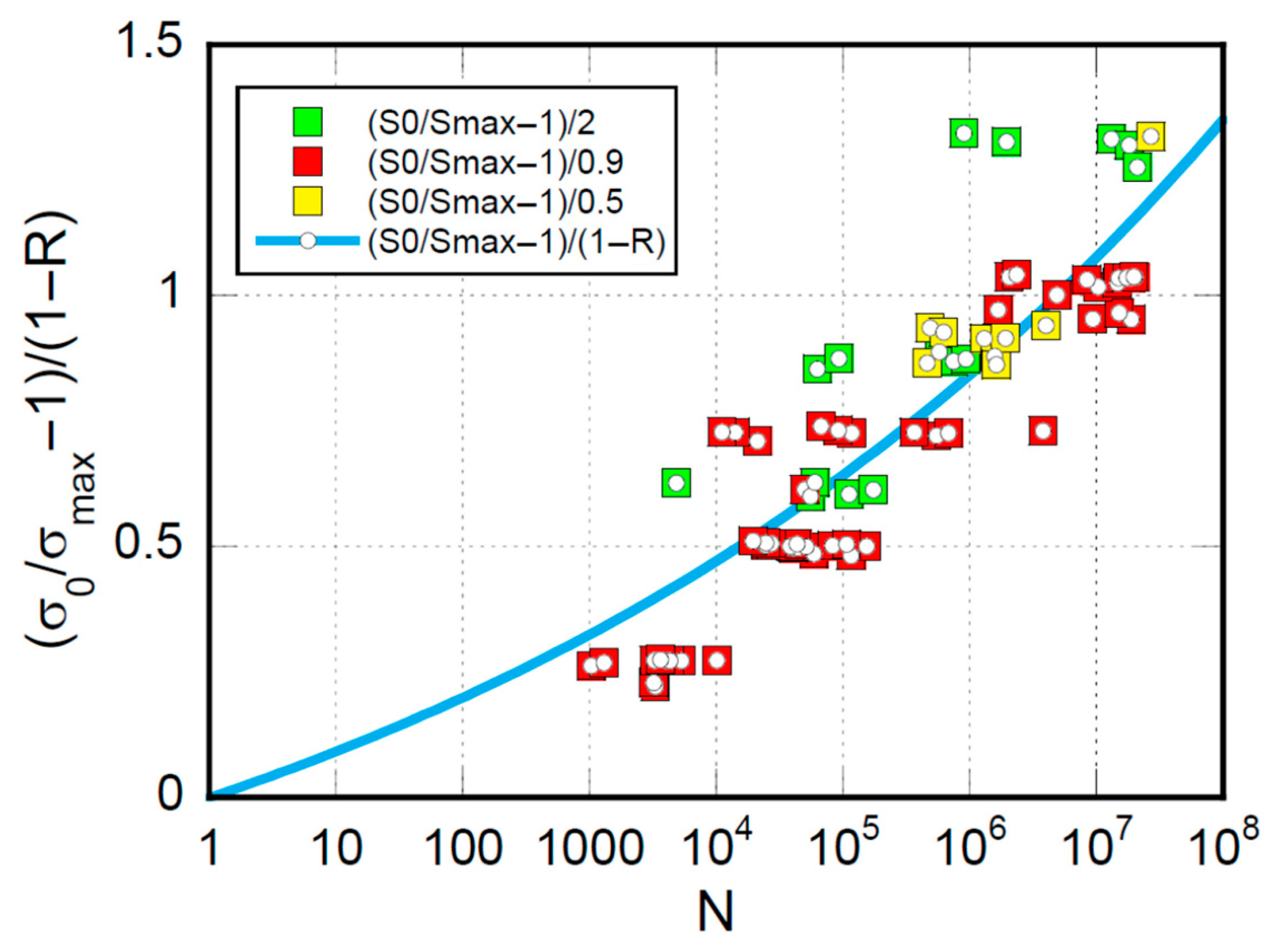

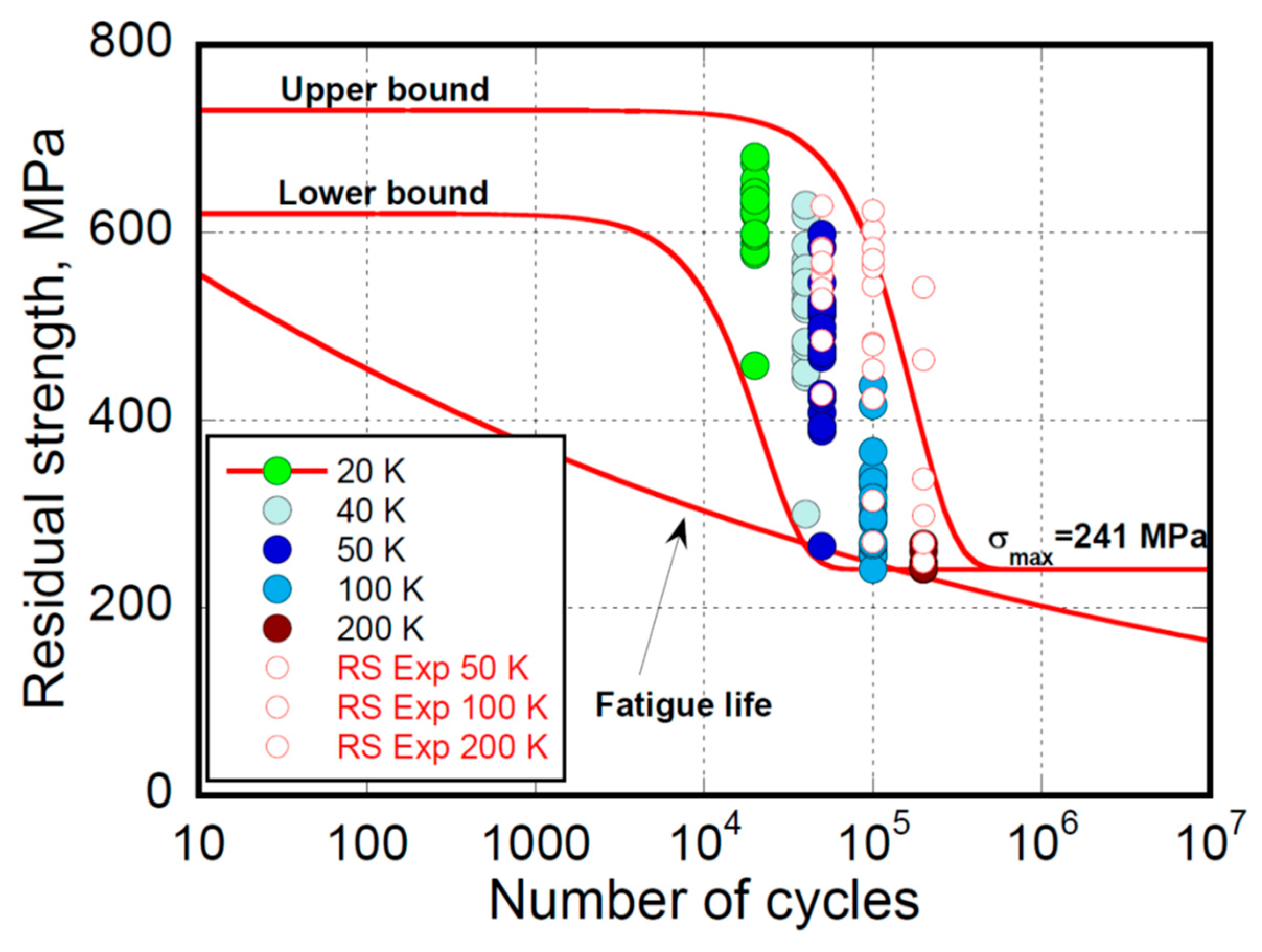

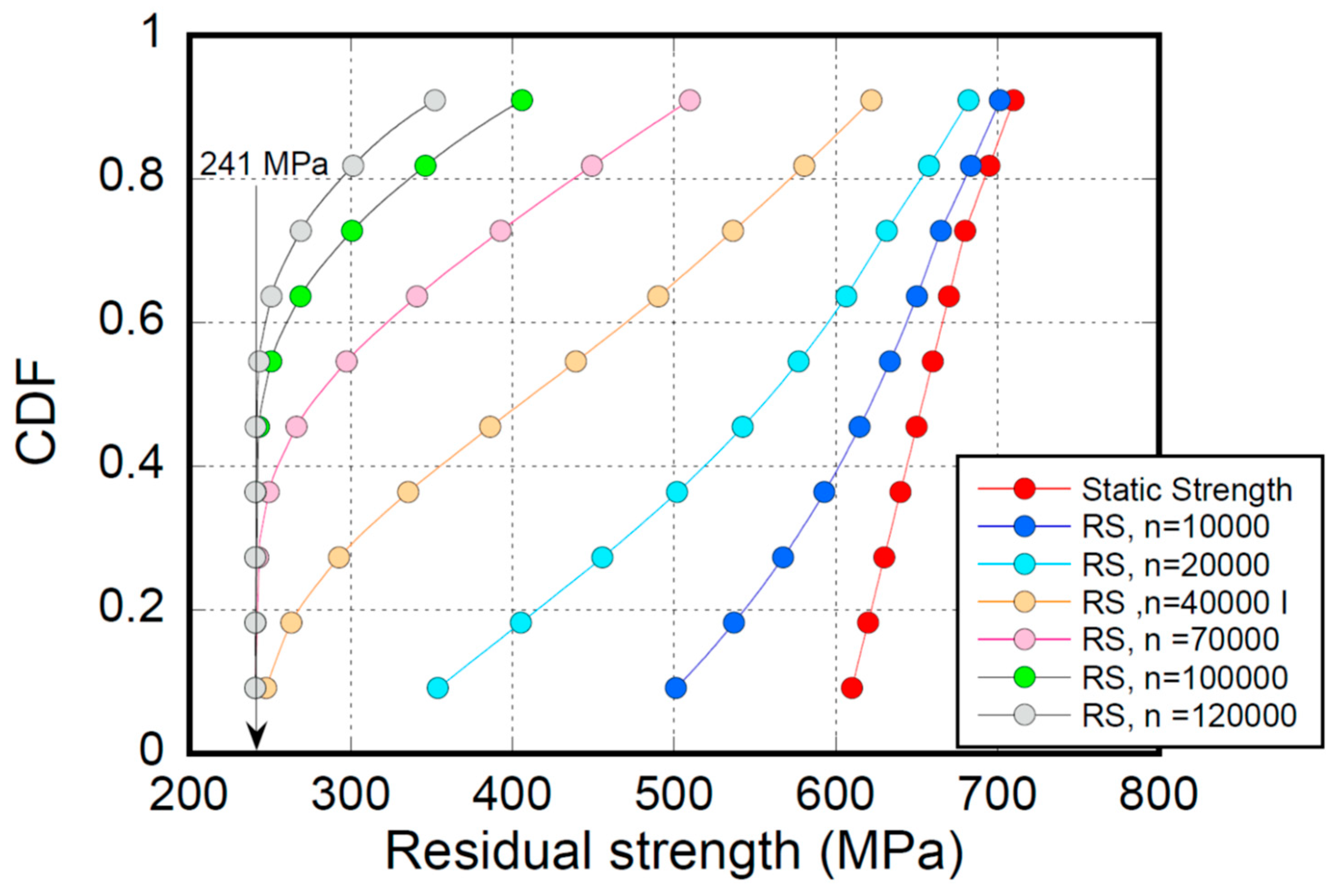

4.3. Residual Strength

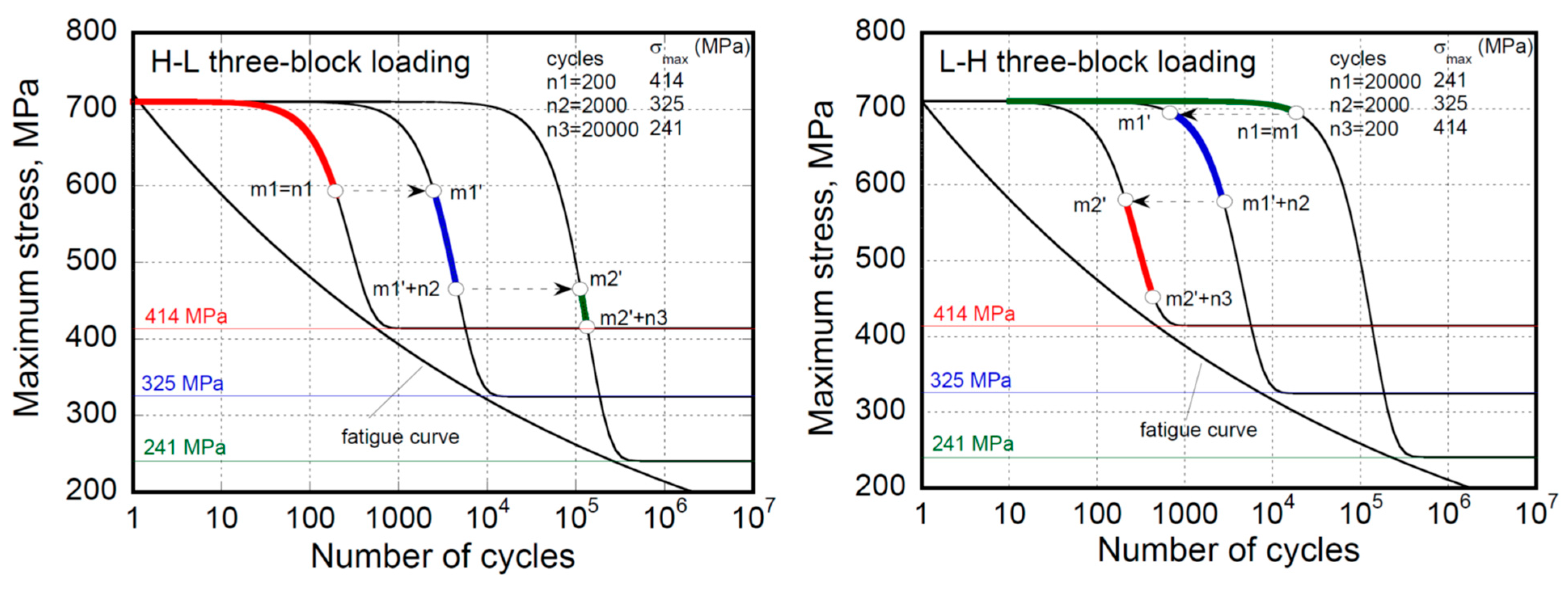

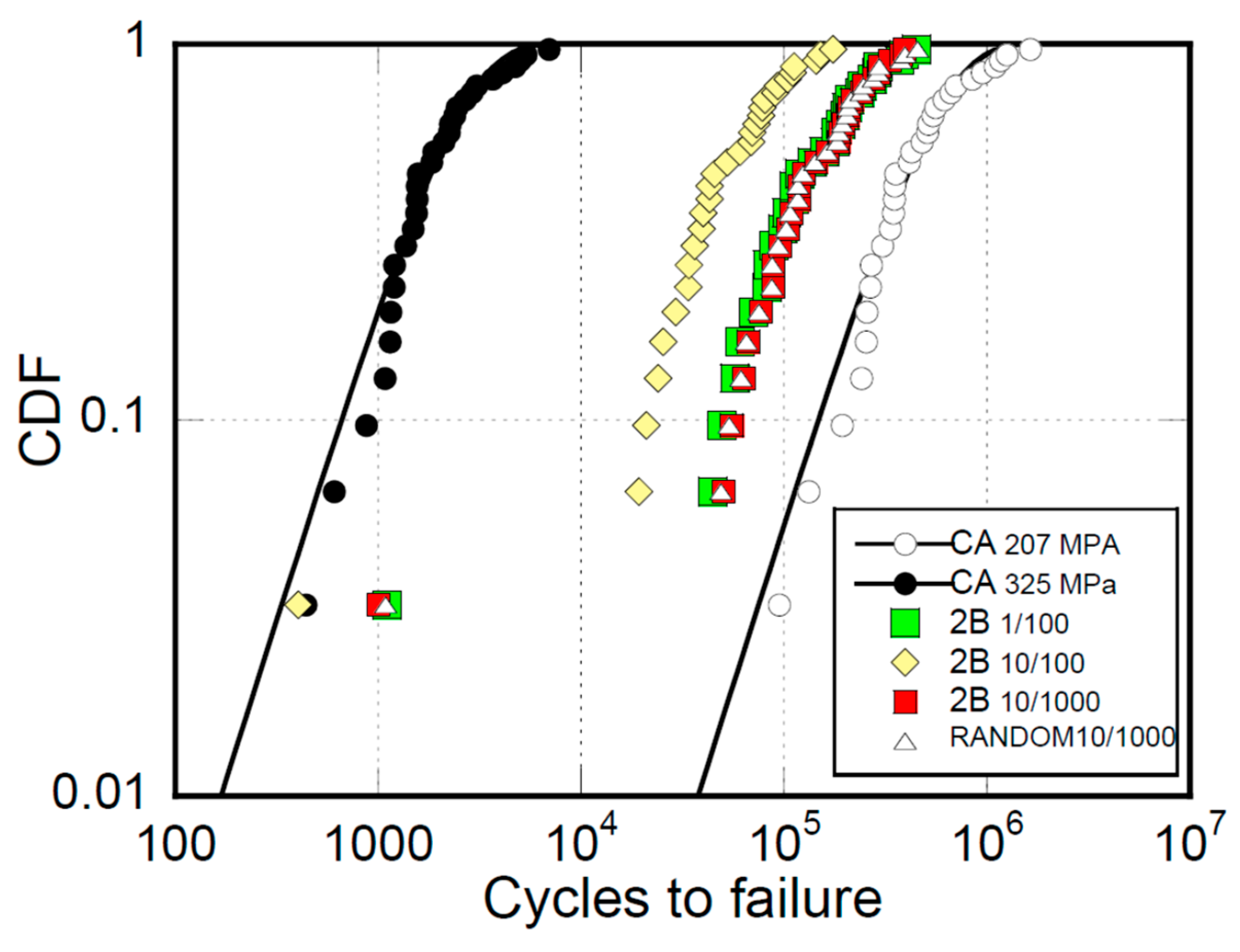

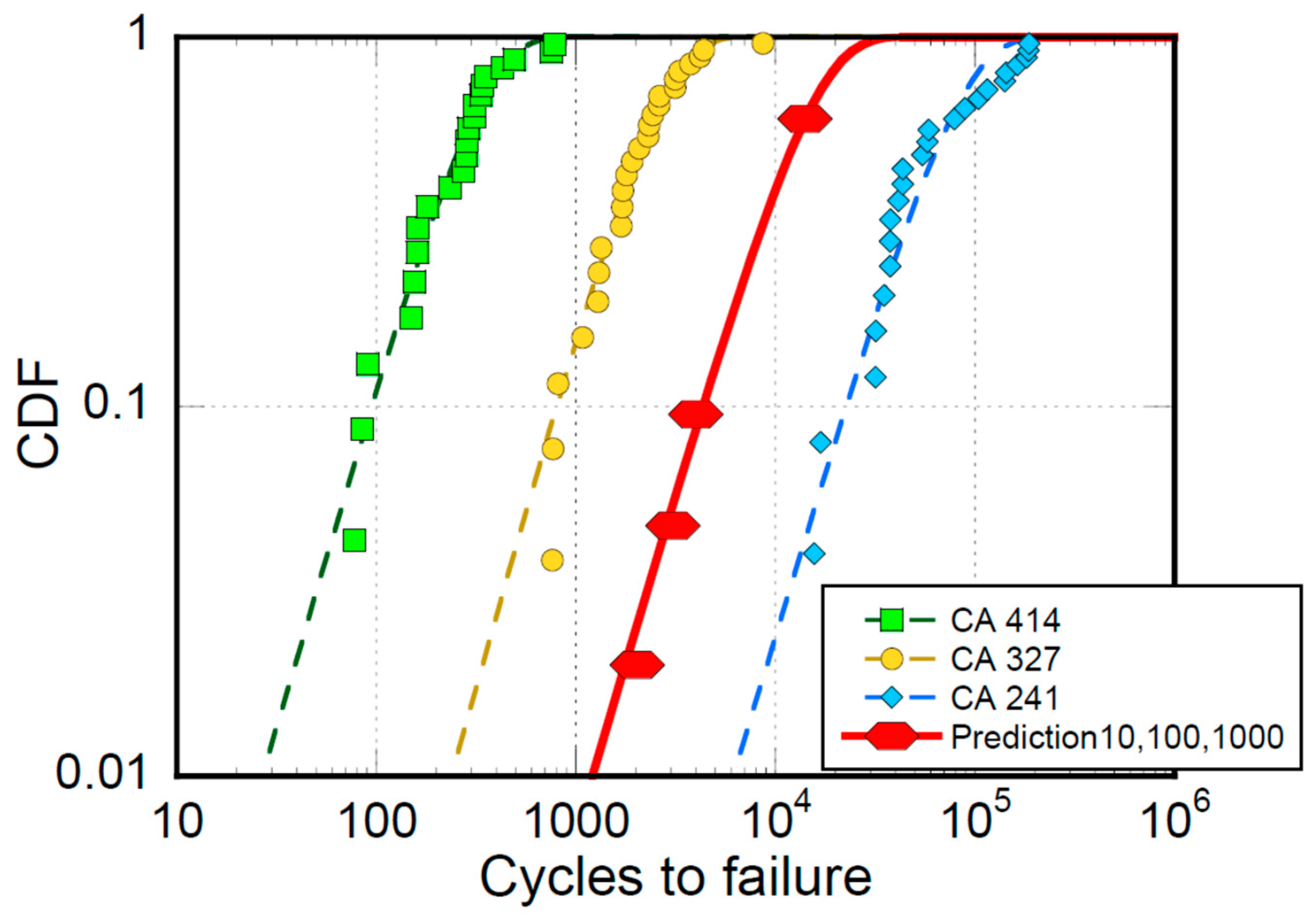

4.4. Variable Amplitude (VA) Modeling

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Halpin, J.C. Requirements for Certification of Composite Airframes: Historical Evolution; Nicolais, L., Borzacchiello, A., Eds.; Wiley Encyclopedia of Composites: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-470-12828-2. [Google Scholar]

- Halpin, J.C.; Johnson, T.A.; Waddoups, M.E. Kinetic fracture models and structural reliability. Int. J. Fract. Mech. 1972, 8, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reifsneider, K.L. (Ed.) Fatigue of Composite Materials; Elsevier Publ.: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilopoulos, A.P.; Keller, T. (Eds.) Fatigue of Fiber-Reinforced Composites; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; ISBN 10: 1447126947. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilopoulos, A.P. The history of fiber-reinforced polymer composite laminate fatigue. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 134, 105512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Paepegem, W.; Degrieck, J. A new coupled approach of residual stiffness and strength for fatigue of fibre-reinforced composites. Int. J. Fatigue 2002, 24, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Yao, X. A review on manufacturing defects and their detection of fiber reinforced resin matrix composites. Compos. Part C Open Access 2022, 8, 100276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendeckyj, G.P. Life prediction for resin-matrix composite materials. In Fatigue of Composite Materials; Reifsneider, K.L., Ed.; Elsevier Science Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1990; pp. 431–483. [Google Scholar]

- Kassapoglou, C. Fatigue life prediction of composite structures under constant amplitude loading. J. Compos. Mater. 2007, 41, 2737–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, A.; Caprino, G.; Stupak, P.; Zhou, J.; Nicolais, L. Effect of stress ratio on the flexural fatigue behavior of continuous strand mat reinforced plastics. Sci. Eng. Compos. Mater. 1996, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, A.; Giorgio, M.; Grassia, L. Modeling the residual strength of carbon fiber reinforced composites subjected to cyclic loading. Int. J. Fatigue 2015, 78, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, H.T.; Kim, R.Y. Proof testing of composite materials. J. Compos. Mater. 1975, 9, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, P.C.; Croman, R. Residual strength in fatigue based on the strength-life equal rank assumption. J. Compos. Mater. 1978, 12, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, P.M.; Butler, R.J.; Curtis, P.T. The Strength-Life Equal Rank Assumption and its application to the fatigue life prediction of composite materials. Int. J. Fatigue 1988, 10, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamstedt, E.K.; Sjögren, B.A. An experimental investigation of the sequence effect in block amplitude loading of cross-ply laminates. Int. J. Fatigue 2002, 24, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashin, Z. Cumulative damage theory for composite materials: Residual life and residual strength methods. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1985, 23, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.N.; Liu, M.D. Residual strength degradation model and theory of periodic proof tests for graphite/epoxy laminates. J. Compos. Mater. 1977, 11, 176–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprino, G.; D’Amore, A. Flexural fatigue behavior of random continuous-fibre-reinforced thermoplastic composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1998, 58, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippidis, T.P.; Passipoularidis, V.A. Residual strength after fatigue in composites: Theory vs. experiment. Int. J. Fatigue 2007, 29, 2104–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passipoularidis, V.A.; Philippidis, T.P. Strength Degradation due to Fatigue in Fiber Dominated Glass/Epoxy Composites: A Statistical Approach. J. Compos. Mater. 2009, 43, 997–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tserpes, K.I.; Papanikos, P.; Labeas, G.; Pantelakis, S. Fatigue damage accumulation and residual strength assessment of CFRP laminates. Compos. Struct. 2004, 63, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, A.; Grassia, L. The Fatigue Response’s Fingerprint of Composite Materials Subjected to Constant Variable Amplitude Loadings. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, A.; Grassia, L. A method to predict the fatigue life and the residual strength of composite materials subjected to variable amplitude (VA) loadings. Compos. Struct. 2019, 228, 111338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, A.; Califano, A.; Grassia, L. Modelling the loading rate effects on the fatigue response of composite materials under constant and variable frequency loadings. Int. J. Fatigue 2021, 150, 106338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, A.; Grassia, L. Phenomenological approach to the study of Hierarchical damage mechanisms in composite materials subjected to fatigue loadings. Compos. Struct. 2017, 175, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, M.A. Cumulative Damage in Fatigue. J. Appl. Mech. 1945, 12, A159–A164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, H.A. Cumulative damage in composites. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 1990, 112, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, A.; Grassia, L. Comparative Study of Phenomenological Residual Strength Models for Composite Materials Subjected to Fatigue: Predictions at Constant Amplitude (CA) Loading. Materials 2019, 12, 3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, A.; Grassia, L. Statistical Lifetime of Composites Subjected to Random and Ordered Block Loadings. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2025, 48, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, N.; Samborsky, D.; Mandell, J.; Cairns, D. Spectrum Fatigue Lifetime and Residual Strength for Fiberglass Laminates in Tension. In A Collection of the 2001 ASME Wind Energy Symposium; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Inc.: Reston, VA, USA; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Philippidis, T.P.; Vassilopoulos, A.P. Life prediction methodology for GFRP laminates under spectrum loading. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2004, 35, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaff, J.R.; Davidson, B.D. Life prediction methodology for composite structures. Part I—Constant amplitude and two-stress level fatigue. J. Compos. Mater. 1997, 31, 128–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaff, J.R.; Davidson, B.D. Life prediction methodology for composite structures. Part II—Spectrum fatigue. J. Compos. Mater. 1997, 31, 158–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.N.; Jones, D.L. Load sequence effects on the fatigue of unnotched composite materials. In Fatigue of Fibrous Composite Materials; Lauraitis, K.N., Ed.; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1981; pp. 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, T.; Gathercole, N.; Reiter, H.; Harris, B. Life prediction for fatigue of T800/5245 carbon-fibre composites: II. Variable-amplitude loading. Int. J. Fatigue 1994, 16, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, N.K. Spectrum Fatigue Lifetime Residual Strength for Fiberglass Laminates in Tension. Ph.D. Thesis, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bedi, R.; Chandra, R. Fatigue-life distributions and failure probability for glass-fiber reinforced polymeric composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2009, 69, 1381–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamsted, E.K.; Sjögren, B.A. Micromechanisms in tension-compression fatigue of composite laminates containing transverse plies. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1999, 59, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, M.; Koizumi, M. Nonlinear constant fatigue life diagrams for carbon/epoxy laminates at room temperature. Compos. Part A 2007, 38, 2342–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, B. A parametric constant-life model for prediction of the fatigue lives of fibre-reinforced plastics. In Fatigue in Composites; Harris, B., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Limited: London, UK, 2003; pp. 546–568. [Google Scholar]

- Boerstra, G.K. The multislope model: A new description for the fatigue strength of glass reinforced plastic. Int. J. Fatigue 2007, 29, 1571–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprino, G.; D’Amore, A. Fatigue Life of Graphite/Epoxy Laminates Subjected to Tension-Compression Loadings. Mech. Time-Depend. Mater. 2000, 4, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Found, M.S.; Quaresimin, M. Two-stage fatigue loading of woven carbon fibre reinforced laminates. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2003, 26, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.N.; Jones, D.L. Load sequence effects on graphite/epoxy [±35]2s laminates. In Long-Term Behavior of Composites, STP 813; ASTM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1983; pp. 246–262. [Google Scholar]

| Static Strength, MPa | ||

|---|---|---|

| Tension | Compression | |

| 1 | 625.00 | 399.48 |

| 2 | 657.00 | 395.82 |

| 3 | 658.00 | 405.49 |

| 4 | 658.00 | 368.34 |

| 5 | 661.00 | 410.54 |

| 6 | 664.00 | 368.21 |

| 7 | 665.00 | 416.44 |

| 8 | 665.00 | 379.01 |

| 9 | 673.00 | 435.09 |

| 10 | 674.00 | 427.49 |

| 11 | 675.00 | 408.58 |

| 12 | 678.00 | 406.71 |

| 13 | 680.00 | 387.75 |

| 14 | 683.00 | 419.75 |

| 15 | 684.00 | 370.86 |

| 16 | 685.00 | 404.78 |

| 17 | 686.00 | 426.97 |

| 18 | 691.00 | 397.16 |

| 19 | 701.00 | 421.48 |

| 20 | 705.00 | 394.64 |

| 21 | 411.15 | |

| 22 | 374.45 | |

| 23 | 415.66 | |

| 24 | 413.70 | |

| R = 0.1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | σmax (MPa) | N | σmax (MPa) | N | σmax | N | σmax (MPa) |

| 78,000 85,000 91,000 149.00 155.00 161.00 162.00 180.00 234.00 274.00 283.00 286.00 290.00 310.00 311.00 334.00 342.00 356.00 429.00 491.00 757.00 783.00 | 410.00 410.00 410.00 410.00 410.00 410.00 410.00 410.00 410.00 410.00 410.00 410.00 410.00 410.00 410.00 410.00 410.00 410.00 410.00 410.00 410.00 410.00 | 763.00 769.00 814.00 1081.0 1289.0 1306.0 1339.0 1690.0 1706.0 1722.0 1794.0 1914.0 2078.0 2297.0 2329.0 2433.0 2611.0 2620.0 3139.0 3152.0 3306.0 3744.0 4190.0 4375.0 8653.0 | 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 327.00 | 15,680 16,884 31,732 31,943 35,109 37,576 37,576 37,855 41,493 43,491 43,618 54,487 57,742 58,826 78,888 89,527 1.0468 × 105 1.1552 × 105 1.4138 × 105 1.4348 × 105 1.6375 × 105 1.8152 × 105 1.8627 × 105 1.8729 × 105 | 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 241.00 | 2.6129 × 105 2.7427 × 105 2.8661 × 105 2.9455 × 105 3.1889 × 105 3.7331 × 105 3.8283 × 105 4.1889 × 105 4.2127 × 105 4.3819 × 105 4.9540 × 105 4.9635 × 105 5.4453 × 105 5.8837 × 105 5.9861 × 105 6.9745 × 105 7.3287 × 105 1.1376 × 106 | 207.00 207.00 207.00 207.00 207.00 207.00 207.00 207.00 207.00 207.00 207.00 207.00 207.00 207.00 207.00 207.00 207.00 207.00 |

| R = 10 | R = 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | σmax (MPa) | N | σmax (MPa) | N | σmax (MPa) | N | σmax (MPa) |

| 4861.0 55,555 60,035 1.1189 × 105 1.7397 × 105 5.7736 × 105 62,837 7.4481 × 105 93,249 9.3635 × 105 9.0210 × 105 1.3140 × 107 1.8148 × 107 1.9627 × 106 2.1083 × 107 | −178.42 −182.78 −178.27 −182.08 −180.64 −144.85 −148.49 −146.81 −146.24 −146.31 −110.25 −110.94 −111.68 −111.28 −114.45 | 3335.0 3215.0 1035.0 1305.0 5325.0 4145.0 4325.0 10185 3265.0 3635.0 1.1608 × 105 59,035 40,625 44,095 51,225 1.5393 × 105 38,495 82,875 24,625 1.0692 × 105 43,525 27,265 24,685 19,565 50,095 | −335.37 −333.46 −325.19 −323.79 −322.94 −322.88 −322.83 −322.72 −322.67 −322.39 −280.47 −279.74 −277.77 −277.70 −277.27 −277.22 −277.19 −276.95 −276.81 −276.54 −276.42 −276.36 −276.04 −275.39 −259.09 | 21,240 5.4873 × 105 6.7972 × 105 1.1738 × 105 3.6657 × 105 14,172 11,145 3.7906 × 106 92,345 67,035 1.8841 × 107 9.3307 × 106 1.5087 × 107 1.6807 × 106 4.8795 × 106 1.0372 × 107 1.4646 × 107 8.4254 × 106 1.5057 × 107 1.8598 × 107 1.7471 × 107 2.0219 × 107 2.0508 × 106 1.9803 × 107 2.3530 × 106 | −245.30 −243.89 −243.15 −243.14 −242.98 −242.94 −242.84 −242.60 −242.46 −241.37 −216.49 −216.39 −215.17 −214.46 −211.49 −209.86 −209.11 −208.50 −208.16 −208.10 −208.09 −208.03 −207.93 −207.90 −207.49 | 4.6303 × 105 4.8990 × 105 6.2258 × 105 1.3073 × 106 1.5840 × 106 1.6240 × 106 1.9259 × 106 4.0000 × 106 2.7000 × 107 | −280.58 −273.84 −274.67 −275.92 −279.27 −280.91 −275.89 −273.41 −242.36 |

| DD16 | α | β | γ (MPa) | δ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure tension | R = 0.1; R = 0.3; R = 0.5; R = 0.7 | 1.0957 | 0.0886 | 661 | 19.5 |

| Prevailing tension | R = −0.4; R = −0.62 | ||||

| Pure compression | R = 10; ; | 0.54 | 0.068 | 413 | 22 |

| Prevailing compression | ; , ; |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Amore, A.; Grassia, L. Unveiling the Responses’ Feature of Composites Subjected to Fatigue Loadings—Part 1: Theoretical and Experimental Fatigue Response Under the Strength-Residual Strength-Life Equal Rank Assumption (SRSLERA) and the Equivalent Residual Strength Assumption (ERSA). J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 528. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9100528

D’Amore A, Grassia L. Unveiling the Responses’ Feature of Composites Subjected to Fatigue Loadings—Part 1: Theoretical and Experimental Fatigue Response Under the Strength-Residual Strength-Life Equal Rank Assumption (SRSLERA) and the Equivalent Residual Strength Assumption (ERSA). Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(10):528. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9100528

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Amore, Alberto, and Luigi Grassia. 2025. "Unveiling the Responses’ Feature of Composites Subjected to Fatigue Loadings—Part 1: Theoretical and Experimental Fatigue Response Under the Strength-Residual Strength-Life Equal Rank Assumption (SRSLERA) and the Equivalent Residual Strength Assumption (ERSA)" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 10: 528. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9100528

APA StyleD’Amore, A., & Grassia, L. (2025). Unveiling the Responses’ Feature of Composites Subjected to Fatigue Loadings—Part 1: Theoretical and Experimental Fatigue Response Under the Strength-Residual Strength-Life Equal Rank Assumption (SRSLERA) and the Equivalent Residual Strength Assumption (ERSA). Journal of Composites Science, 9(10), 528. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9100528