Upcycling Pultruded Polyester–Glass Thermoset Scraps into Polyolefin Composites: A Comparative Structure–Property Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation and Processing of Recycled Polyester-Glass Fiber Filled PE Composites

2.2.1. Fiber Recycling Process

2.2.2. Preparation of the PWCs

2.3. Physical Characterization of Polyester-Glass Fiber Thermoset Scraps (PS)

2.3.1. Particle Size Distribution

2.3.2. Fiber Length Analysis

2.3.3. Determination of Glass Fiber Content (Burn-Off Test)

2.4. Analysis of Polyester-Glass Fiber Waste-Filled Composites (PWCs)

2.4.1. Optical and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis of PWCs

2.4.2. Density and Moisture Absorption of PWCs

2.5. Mechanical Properties of the PWCs

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Assessment of Recycled Polyester-Glass Fiber Thermoset Scrap (PS) Fillers

3.2. Assessment of Recycled Polyester-Glass Fiber Filled Thermoplastic Composites (PWCs)

3.3. Morphological and Interfacial Characterization of PWCs

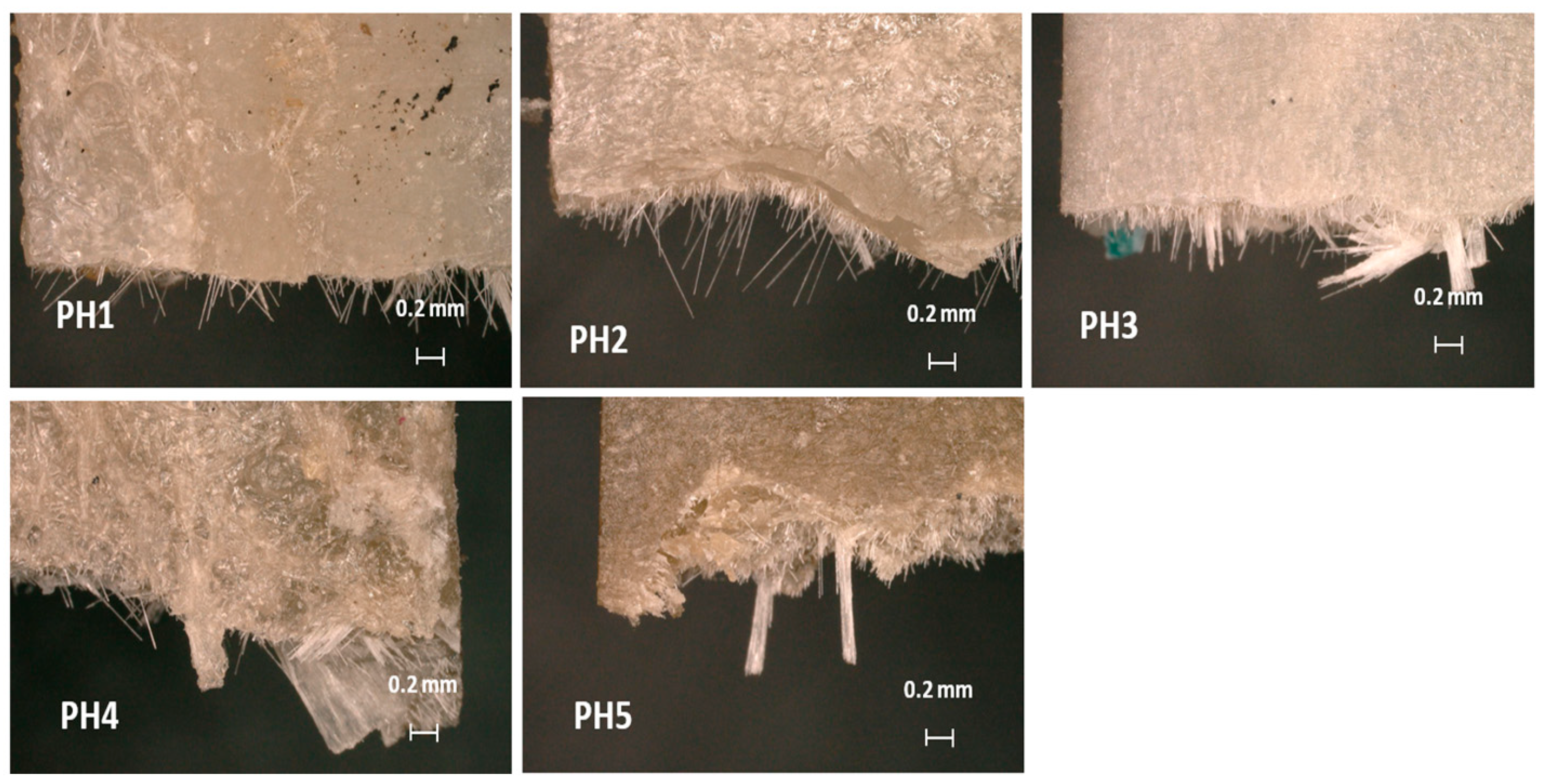

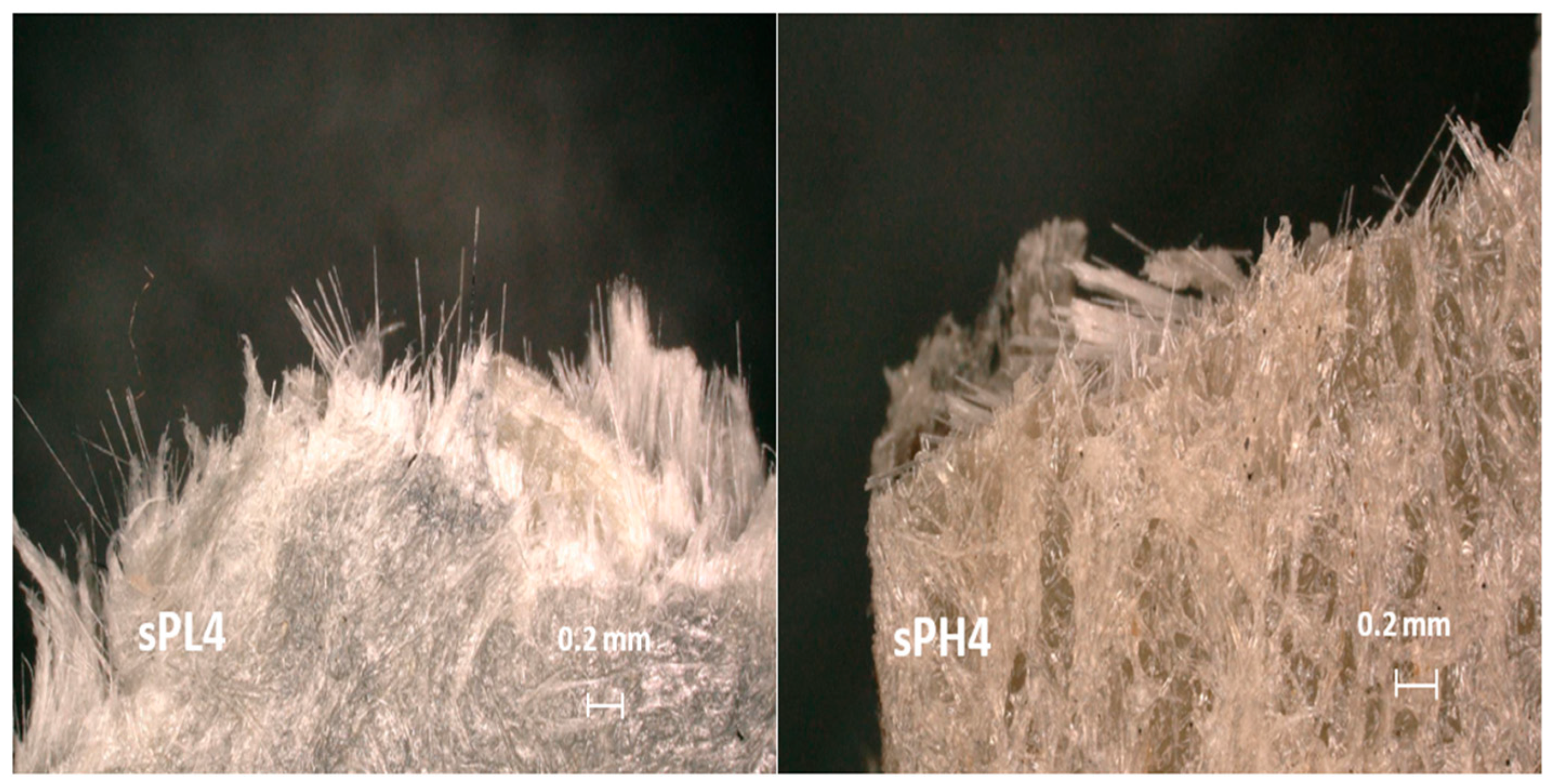

3.3.1. Optical Microstructural Analysis

3.3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

3.4. Mechanical Performance Evaluation of PWCs

3.4.1. Tensile Properties of PWCs

3.4.2. Flexural Properties of PWCs

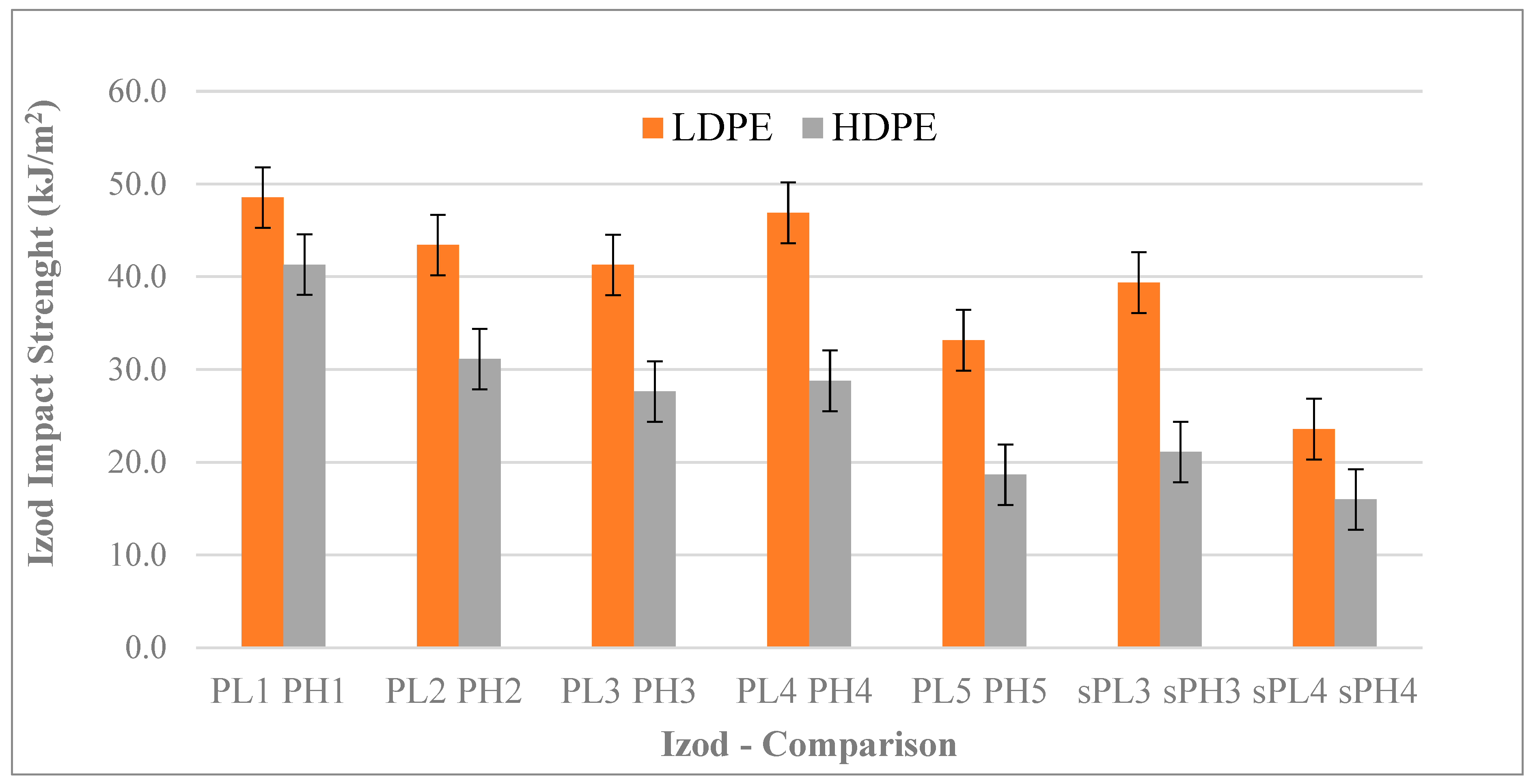

3.4.3. Izod Impact Properties of PWCs

4. Conclusions

- -

- The recycled fillers comprised resin-rich particulates, partially separated short fibers, and macro-scale fiber bundles, which led to increasingly anisotropic microstructures at higher loadings. Beyond 30 wt.% filler, fiber agglomeration, incomplete bundle disintegration, and micro void networks became more pronounced—features that restricted uniform load transfer and contributed to embrittlement, consistent with prior observations in recycled GFRP–polyolefin systems.

- -

- Tensile testing revealed significant stiffness enhancements in both LDPE- and HDPE-based composites. The modulus of LDPE increased from ~318 MPa to 1245 MPa, while HDPE rose from ~540 MPa to over 1700 MPa. Tensile strength improvements were most notable at moderate filler contents (20–30 wt.%), where a hybrid load-sharing mechanism between the matrix and partially separated fiber bundles became effective. At higher filler levels, however, fiber clustering and interfacial decohesion limited strength and promoted brittle fracture—trends aligned with those reported for short glass fiber-reinforced polyolefins.

- -

- Flexural properties exhibited the strongest dependence on filler content, with moduli reaching up to ~3.0 GPa. Surface-modified composites (sPL, sPH) consistently outperformed their untreated counterparts due to improved fiber–matrix wetting and enhanced interfacial shear transfer, underscoring the role of surface activation in strengthening non-polar polymer–glass interfaces. These findings are consistent with literature on compatibilized PE/GF composites, which similarly report improved bending performance through interfacial enhancement.

- -

- Izod impact results confirmed the expected stiffness–toughness trade-off. LDPE-based composites retained higher toughness than HDPE due to their inherently ductile matrix. Impact strength decreased systematically with increasing filler content in both systems. However, surface modification partially mitigated this decline by promoting more effective crack deflection and reducing interfacial failure. At high filler loadings, the dominance of fiber clusters and reduced matrix continuity limited the benefits of surface treatment.

- -

- Density increased proportionally with filler content, while water absorption was strongly influenced by matrix polarity and interfacial quality. LDPE composites exhibited higher moisture uptake than HDPE, and surface modification reduced water absorption by 5–10% by minimizing microvoid pathways and enhancing interfacial sealing. Diffusion coefficients (≈0.4–2.1 × 10−13 m2/s) indicated predominantly Fickian behavior, with slight deviations at higher filler contents due to increased microstructural heterogeneity—consistent with trends observed in recycled fiber–polyolefin systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PS | Recycled Polyester Scraps |

| sPS | Surface Modified Recycled Polyester Scraps |

| GFRP | Glass Fiber Reinforced Plastic |

| PWC | Polyester–Glass Fiber Thermoset Scrap-Filled Composites |

| LDPE | Low-Density Polyethylene |

| HDPE | High-Density Polyethylene |

| PL | LDPE-based PWCs |

| PH | HDPE-based PWCs |

| sPL | Surface-modified filled LDPE-based PWCs |

| sPH | Surface-modified filled HDPE-based PWCs |

| CH3COOH | Acetic Acid |

| C6H8O7 | Citric Acid |

| MPAD | Materials Processing and Applications Development |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

References

- Morici, E.; Dintcheva, N.T. Recycling of Thermoset Materials and Thermoset-Based Composites: Challenge and Opportunity. Polymers 2022, 14, 4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, X.; Liu, S.Y.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Wang, Q.Z.; Xiao, C.Z. A Technology Review of Recycling Methods for Fiber-Reinforced Thermosets. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2022, 41, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, M.; Barik, D.; Chandran, S.S.R. Exploration of Material Recovery Framework from Waste—A Revolutionary Move toward Clean Environment. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2024, 18, 100589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaghemandi, M. Sustainable Solutions through Innovative Plastic Waste Recycling Technologies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehanno, C.; Alty, J.W.; Roosen, M.; De Meester, S.; Dove, A.P.; Chen, E.Y.X.; Leibfarth, F.A.; Sardon, H. Critical Advances and Future Opportunities in Upcycling Commodity Polymers. Nature 2022, 603, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalid, M.Y.; Arif, Z.U.; Hossain, M.; Umer, R. Recycling of Wind Turbine Blades through Modern Recycling Technologies: A Road to Zero Waste. Renew. Energy Focus 2023, 44, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwudili, J.A.; Miskolczi, N.; Nagy, T.; Lipóczi, G. Recovery of Glass Fibre and Carbon Fibres from Reinforced Thermosets by Batch Pyrolysis and Investigation of Fibre Re-Using as Reinforcement in LDPE Matrix. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 91, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, K.; Varghese, S.; Kalaprasad, G.; Thomas, S.; Prasannakumari, L.; Koshy, P.; Pavithran, C. Influence of Interfacial Adhesion on the Mechanical Properties and Fracture Behaviour of Short Sisal Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites. Eur. Polym. J. 1996, 32, 1243–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazan, C.; Perniu, D.; Cosnita, M.; Duta, A. Polymeric Wastes from Automotives as Second Raw Materials for Large Scale Products. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2013, 12, 1649–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Alves, J.; Castellani, R.; Tillier, Y.; Bouvard, J.L. Application of the Time–Temperature Equivalence at Large Deformation to Describe the Mechanical Behavior of Polyethylene-Based Thermoplastic, Thermoset and Vitrimer Polymers. Polymers 2023, 281, 126110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragaert, K.; Delva, L.; Van Geem, K. Mechanical and Chemical Recycling of Solid Plastic Waste. Waste Manag. 2017, 69, 24–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, I.; Jenks, M.J.; Roelands, M.C.; White, R.J.; Van Harmelen, T.; De Wild, P.; van Der Laan, G.P.; Meirer, F.; Keurentjes, J.T.; Weckhuysen, B.M. Beyond Mechanical Recycling: Giving New Life to Plastic Waste. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 15402–15423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Periasamy, D.; Manoharan, B.; Niranjana, K.; Aravind, D.; Krishnasamy, S.; Natarajan, V. Recycling of Thermoset Waste/High-Density Polyethylene Composites: Examining the Thermal Properties. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 2739–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkori, R.; Baha, M.; Hachim, A.; Elhad, K.; Lamarti, A. Comparison of the Mechanical Behavior of Two Thermoplastic Polymers by Static Tests (Numerically and Experimentally): High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) and High Impact Polystyrene (HIPS). In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Networking, Information Systems & Security, Stockholm, Sweden, 13–15 August 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anstey, A.; Codou, A.; Misra, M.; Mohanty, A.K. Novel Compatibilized Nylon-Based Ternary Blends with Polypropylene and Poly (lactic acid): Fractionated Crystallization Phenomena and Mechanical Performance. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 2845–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meira Castro, A.C.; Carvalho, J.P.; Ribeiro, M.C.S.; Meixedo, J.P.; Silva, F.J.G.; Fiúza, A.; Dinis, M.L. An Integrated Recycling Approach for GFRP Pultrusion Wastes: Recycling and Reuse Assessment into New Composite Materials Using Fuzzy Boolean Nets. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Apraku, S.E.; Zhu, Y. Recycling and Recovery of Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites for End-of-Life Wind Turbine Blade Management. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 9644–9658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveux, G.; Dandy, L.O.; Leeke, G.A. Current Status of Recycling of Fibre Reinforced Polymers: Review of Technologies, Reuse and Resulting Properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2015, 72, 61–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM, E11-20; Standard Specification for Woven Wire Test Sieve Cloth and Test Sieves. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; He, M.; Qin, S.; Yu, J. Effect of Fiber Length and Dispersion on Properties of Long Glass Fiber Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites Based on Poly(butylene terephthalate). RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 15439–15454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiola, J.H.; Astobitza, U.; Iturrondobeitia, M.; Burgoa, A.; Ibarretxe, J.; Arriaga, A. Relation Between Injection Molding Conditions, Fiber Length, and Mechanical Properties of Highly Reinforced Long Fiber Polypropylene: Part II Long-Term Creep Performance. Polymers 2023, 17, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D3171-22; Standard Test Methods for Constituent Content of Composite Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- Lee, S.-G.; Oh, D.; Woo, J.H. The Effect of High Glass Fiber Content and Reinforcement Combination on Pulse-Echo Ultrasonic Measurement of Composite Ship Structures. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Jin, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Luo, Z.; Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, H.; Xu, H.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Lifetime Prediction and Aging Mechanism of Glass Fiber-Reinforced Acrylate–Styrene–Acrylonitrile/Polycarbonate Composite Under Long-Term Thermal and Oxidative Conditions. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2024, 149, 2075–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cech, V.; Palesch, E.; Lukes, J. The glass fiber–polymer matrix interface/interphase characterized by nanoscale imaging techniques. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2013, 82, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wu, H.; Zhang, M.; Fu, S.; Zhu, K. Fiber Orientation Reconstruction from SEM Images of Fiber-Reinforced Composites. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares-Elejoste, P.; Seoane-Rivero, R.; Gandarias, I.; Iturmendi, A.; Gondra, K. Sustainable Alternatives for the Development of Thermoset Composites with Low Environmental Impact. Polymers 2023, 15, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM D792-20; Standard Test Methods for Density and Specific Gravity (Relative Density) of Plastics by Displacement. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D5229/D5229M-20; Standard Test Method for Moisture Absorption Properties of Polymer Matrix Composites. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- Liu, Z.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, X.; Kang, Z.; Zhang, J. Effect Mechanism and Simulation of Voids on Hygrothermal Performances of Composites. Polymers 2022, 14, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagdani, O.; Tarfaoui, M.; Rouway, M.; Laaouidi, H.; Jamoudi Sbai, S.; Amine Dabachi, M.; Aamir, A.; Nachtane, M. Influence of Moisture Diffusion on the Dynamic Compressive Behavior of Glass/Polyester Composite Joints for Marine Engineering Applications. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanjar, S.; Barui, S.; Kate, K.; Ajjarapu, K.P.K. An Investigation into Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed Thermoplastic-Thermoset Mixed-Matrix Composites: Synergistic Effects of Thermoplastic Skeletal Lattice Geometries and Thermoset Properties. Materials 2024, 17, 4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Chouw, N. Effect of Water, Seawater and Alkaline Solution Ageing on Mechanical Properties of Flax Fabric Reinforced Epoxy Composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 99, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D3039/D3039M-17; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Polymer Matrix Composite Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM D7264/D7264M-15; Standard Test Method for Flexural Properties of Polymer Matrix Composite Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- ASTM D256-10; Standard Test Methods for Determining the Izod Pendulum Impact Resistance of Plastics. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- Ghaffari, S.; Makeev, A.; Seon, G.; Cole, D.P.; Magagnosc, D.J.; Bhowmick, S. Understanding Compressive Strength Improvement of High-Modulus Carbon-Fiber Reinforced Polymeric Composites through Fiber–Matrix Interface Characterization. Mater. Des. 2020, 192, 108798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gal La Salle, E.; Nouigues, A.; Bailleul, J.-L. Thermo-mechanical characterization of unsaturated polyester/glass fiber composites for recycling. Int. J. Mater. Form. 2021, 14, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelmach, S.; Gacki, D.; Szul, M.; Słowiński, K.; Radko, T.; Wojtaszek-Kalaitzidi, M. General Evaluation of the Recyclability of Polyester-Glass Laminates Used to Reinforce Steel Tanks. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, S.J. Recycling Technologies for Thermoset Composite Materials—Current Status. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2006, 37, 1206–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginder, R.S.; Ozcan, S. Recycling of commercial E-glass reinforced thermoset composites via two temperature step pyrolysis to improve recovered fiber tensile strength and failure strain. Recycling 2019, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, D.; Kárpáti, Z.; Fekete, E.; Móczó, J. The Role of Interfacial Adhesion in Polymer Composites Engineered from Lignocellulosic Agricultural Waste. Polymers 2021, 13, 3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, P. A novel microbond bundle pullout technique to evaluate the interfacial properties of fibre-reinforced plastic composites. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2017, 40, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salakhov, I.I.; Shaidullin, N.M.; Chalykh, A.E.; Matsko, M.A.; Shapagin, A.V.; Batyrshin, A.Z.; Shandryuk, G.A.; Nifant’ev, I.E. Low-Temperature Mechanical Properties of High-Density and Low-Density Polyethylene and Their Blends. Polymers 2021, 13, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derradj, M.; Zoukrami, F.; Guerba, H.; Benchaoui, A. The effect of laboratory synthesized and modified layered double hydroxides on recycled and neat high-density polyethylene matrix properties using stearic acid as an interface modifier. J. Polym. Res. 2023, 30, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlaoui, O.; Klinkova, O.; Elleuch, R.; Tawfiq, I. Effect of the Glass Fiber Content of a Polybutylene Terephthalate Reinforced Composite Structure on Physical and Mechanical Characteristics. Polymers 2022, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkazaz, E.; Crosby, W.A.; Ollick, A.M.; Elhadary, M. Effect of fiber volume fraction on the mechanical properties of randomly oriented glass fiber reinforced polyurethane elastomer with crosshead speeds. Alexandria Eng. J. 2020, 59, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, O.O. Effect of Fiber Length on Mechanical Properties of Injection Molded Long-Fiber-Reinforced Thermoplastics. Macromol. Res. 2020, 28, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasayama, T.; Inagaki, M.; Sato, N. Direct Simulation of Glass Fiber Breakage in Simple Shear Flow Considering Fiber–Fiber Interaction. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2019, 124, 105514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Luan, X.; Meng, B.; Liu, J.; Lu, Y. Effects of Void Characteristics on the Mechanical Properties of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polyetheretherketone Composites: Micromechanical Modeling and Analysis. Polymers 2025, 17, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.H.; Springer, G.S. Moisture Absorption and Desorption of Composite Materials. J. Compos. Mater. 1976, 10, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, H.G.; Kibler, K.G. Langmuir-Type Model for Anomalous Moisture Diffusion in Composite Resins. J. Compos. Mater. 1978, 12, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, B.; Karbhari, V.M. Characteristics and Models of Moisture Uptake in Fiber-Reinforced Composites: A Topical Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedlaczek, P.; Sinn, G.; Peter, P.; Wan-Wendner, R.; Lichtenegger, H.C. Characterization of Moisture Uptake and Diffusion Mechanisms in Particle-Filled Composites. Polymers 2022, 249, 124799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Xing, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S. A Comprehensive Review on Water Diffusion in Polymers Focusing on the Polymer–Metal Interface Combination. Polymers 2020, 12, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, R.Q.C.; Fook, M.V.L.; Lima, A.G.B. Non-Fickian Moisture Absorption in Vegetable Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composites: The Effect of the Mass Diffusivity. Polymers 2021, 13, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, H.; Shih, Y.-C.; Pillay, S.; Ning, H. Sustainable Reprocessing of Thermoset Composite Waste into Thermoplastics: A Polymer Blend Approach for Circular Material Design. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriprom, W.; Sirivallop, A.; Choodum, A.; Limsakul, W.; Wongniramaikul, W. Plastic/Natural Fiber Composite Based on Recycled Expanded Polystyrene Foam Waste. Polymers 2022, 14, 2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirimoglu, Y.S.; Ozturk, F. Advances in Mechanical and Physicochemical Performances of Recycled Carbon Fiber Reinforced PEKK Composites. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 14453–14478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.-J.; Kim, D.-K.; Han, W.; Choi, S.-H.; Chung, D.-C.; Kim, K.-W.; Kim, B.-J. Facile Enhancement of Mechanical Interfacial Strength of Recycled Carbon Fiber Web-Reinforced Polypropylene Composites via a Single-Step Silane Modification Process. Polymers 2025, 17, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daki, I.; Saloumi, N.; Yousfi, M.; Parajua-sejil, C.; Truchot, V.; Gérard, J.-F.; Cherkaoui, O.; Hannache, H.; El Bouchti, M.; Oumam, M. Exploring the Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Thermoset-Based Composites Reinforced with New Continuous and Chopped Phosphate Glass Fibers. Polymers 2025, 17, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, V.; Kärki, T.; Varis, J. Effect of Fiber Content and Silane Treatment on the Mechanical Properties of Recycled Acrylonitrile-Butadiene-Styrene Fiber Composites. Chemistry 2021, 3, 1258–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSuhaibani, F.A.; Falath, W.; Theravalappil, R. Improved Fracture Toughness of Glass Fibers Reinforced Polypropylene Composites through Hybridization with Polyolefin Elastomers and Polymeric Fibers for Automotive Applications. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 6553–6570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMaadeed, M.A.; Ouederni, M.; Noorunnisa Khanam, P. Effect of chain structure on the properties of Glass fibre/polyethylene composites. Mater. Des. 2013, 47, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, P.N.; AlMaadeed, M.A.A. Processing and characterization of polyethylene-based composites. In Advanced Manufacturing: Polymer and Composites Science; Taylor and Francis Ltd.: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamanpush, S.H.; Li, H.; Tavousi Tabatabaei, A.; Englund, K. Heterogeneous Thermoset/Thermoplastic Recycled Carbon Fiber Composite Materials for Second-Generation Composites. Waste Biomass Valor. 2021, 12, 4653–4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, T.P.; Singh, I.; Sharma, A.K.; Yu, H. Recycling of Thermoset Composites Waste: End of Life Solution. In Composite Materials Processing Using Microwave Heating Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 83–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardeau, F.; Perrin, D.; Caro, A.-S.; Bénézet, J.-C.; Ienny, P. Valorization of waste thermoset material as a filler in thermoplastic: Mechanical properties of phenolic molding compound waste-filled PP composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 45849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, H.; Shih, Y.-C.; Ning, H.; Pillay, S. Upcycling epoxy–glass thermoset waste into high-performance polyethylene composites. Compos. Struct. 2026, 377, 119880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberkane, A.; Bendaikha, H.; Benzidane, R.; Jouenne, J.-B.; Alshaikh, I.M.H.; Belaadi, A.; Ghernaout, D. Mechanical, Thermal, and Morphological Properties of Recycled PP and HDPE Green Composites Reinforced with Atriplex halimus Fibers. J. Nat. Fibers 2025, 22, 2507157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widiastuti, I.; Saputra, H.C.; Kusuma, S.S.W.; Harjanto, B. Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Recycled High-Density Polyethylene/Bamboo with Different Fiber Loadings. Open Eng. 2022, 12, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Wu, H.F.; Kampe, S.L.; Lu, G.Q. Volume Fraction Effects on Interfacial Adhesion Strength of Glass-Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2000, 277, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, K.; Thomas, S.; Pavithran, C. Effect of Chemical Treatment on the Tensile Properties of Short Sisal Fibre-Reinforced Polyethylene Composites. Polymers 1996, 37, 5139–5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.Y.; Feng, X.Q.; Lauke, B.; Mai, Y.W. Effects of Particle Size, Particle/Matrix Interface Adhesion and Particle Loading on Mechanical Properties of Particulate-Polymer Composites. Compos. Part B 2008, 39, 933–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkan, U.; Özcanlı, Y.; Alekberov, V. Effect of Temperature and Time on Mechanical and Electrical Properties of HDPE/Glass Fiber Composites. Fibers Polym. 2013, 14, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrasi, G.; Di Lieto, R.; Patimo, G.; De Pasquale, S.; Sorrentino, A. Structure–Property Relationships on Uniaxially Oriented Carbon Nanotube/Polyethylene Composites. Polymers 2011, 52, 1124–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.F.; Dwight, D.W.; Huff, N.T. Effects of Silane Coupling Agents on the Interphase and Performance of Glass-Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1997, 57, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Elen, M.; Sushmita, K.; Overman, N.R.; Murdy, P.; Presuel-Moreno, F.; Fifield, L.S.; Nickerson, E. Hygrothermal Aging and Recycling Effects on Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Recyclable Thermoplastic Glass Fiber Composites. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 29242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periasamy, D.; Karuppiah, P.; Manoharan, B.; Arockiasamy, F.S.; Kannan, S.; Mohanavel, V.; Velmurugan, P.; Arumugam, N.; Almansour, A.I.; Sivakumar, S. Assessing the Recycling Potential of Thermosetting Polymer Waste in High-Density Polyethylene Composites for Safety Helmet Applications. e-Polymers 2024, 24, 20230080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Du, S.; Zhu, J.; Ma, S. Upcycling of Thermosetting Polymers into High-Value Materials. Mater. Horiz. 2022, 9, 2952–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syduzzaman, M.; Pritha, N.M.; Dulal, M.; Ullah, T.H.M.H.; Mamun, M.A.; Sowrov, K.; Ahmed, A.T.M.F. Flexural and Impact Properties of Recycled High-Density Polyethylene (rHDPE) Composites Reinforced with Hybrid Jute and Banana Fibers. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2025, 2025, 9964196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, K.A.; Romańska, P.; Piech, R.; Majka, T.M.; Michalik, A.; Bednarowski, D.; Zawadzka, Z. Polyethylene Terephthalate-Based Composites with Recycled Flakes and Chemically Resistant Glass Fibres for Construction. Polymers 2025, 17, 3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarz, M.; Behzadnia, A.; Dastan, T. Assessing the Flexural Properties of Interlayer Hybrid Thermoset–Thermoplastic Composites and Their Repairability. Compos. Mech. Comput. Appl. 2022, 13, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrés, Q.; Soler, J.; Rojas-Sola, J.I.; Oliver-Ortega, H.; Julián, F.; Espinach, F.X.; Mutjé, P.; Delgado-Aguilar, M. Flexural Properties and Mean Intrinsic Flexural Strength of Old Newspaper Reinforced Polypropylene Composites. Polymers 2019, 11, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadik, W.A.; El-Demerdash, A.G.M.; Abokhateeb, A.E.A.; Elessawy, N.A. Innovative High-Density Polyethylene/Waste Glass Powder Composite with Remarkable Mechanical, Thermal and Recyclable Properties for Technical Applications. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.L.; Lei, H.H.; Zhang, C.L.; Zhang, C.L. Progress in Surface Treatment of Carbon Fiber and Composite Material. Surf. Technol. 2022, 51, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, H.; Mohamed, M.; Ning, H.; Pillay, S. Recycling of Pultruded Vinyl Ester Thermoset Scraps into Polyethylene Composites: Toward Circular Composite Manufacturing. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.; Ishlda, H.; Maurer, F.H.J. Infrared Analysis and Izod Impact Testing of Multicomponent Polymer Composites: Polyethylene/EPDM/Filler Systems. J. Mater. Sci. 1987, 22, 3963–3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Yang, L.; Jia, C.; Chen, F.; Wang, X. Lightweight and High Impact Toughness PP/PET/POE Composite Foams Fabricated by In Situ Nanofibrillation and Microcellular Injection Molding. Polymers 2023, 15, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti, M.; Scrivani, M.T.; Kociolek, I.; Larsen, Å.G.; Olafsen, K.; Lambertini, V. Enhanced Impact Strength of Recycled PET/Glass Fiber Composites. Polymers 2021, 13, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Fan, M.; Chen, L. Interface and Bonding Mechanisms of Plant Fibre Composites: An Overview. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 101, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Geng, C.; Zhou, M.; Bai, H.; Fu, Q.; He, B. Impact Toughness of Polypropylene/Glass Fiber Composites: Interplay between Intrinsic Toughening and Extrinsic Toughening. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 92, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Polymer Matrix Type | Composite Label | Thermoplastic Content (wt.%) | Thermoset Waste Content (wt.%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated PS | Surface Treated PS (sPS) | |||

| LDPE | PL1 | 90 | 10 | - |

| PL2 | 80 | 20 | - | |

| PL3 | 70 | 30 | - | |

| PL4 | 60 | 40 | - | |

| PL5 | 50 | 50 | - | |

| sPL3 | 70 | - | 30 | |

| sPL4 | 60 | - | 40 | |

| HDPE | PH1 | 90 | 10 | - |

| PH2 | 80 | 20 | - | |

| PH3 | 70 | 30 | - | |

| PH4 | 60 | 40 | - | |

| PH5 | 50 | 50 | - | |

| sPH3 | 70 | - | 30 | |

| sPH4 | 60 | - | 40 | |

| Standard Sieve Mesh (ASTM E11) | Morphological Classification of Recycled PSs | Mass Fraction (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No. 4 (>4.75 mm) | Resin Encapsulated Macrofibre Clusters | 5.11% |

| No. 5 (>4 mm) | Coarse Fiber Agglomerates | 12.23% |

| No. 6 (>3.35 mm) | Medium-scale Fiber Fragments | 28.32% |

| No. 25 (>710 µm) | Micrometer-Scale Dispersed Fiber Structures | 27.57% |

| No. 30 (>600 µm) | Fine Fiber Fragments | 10.64% |

| No. 40 (>425 µm) | Pulverized Fiber Dust and Particles | 8.95% |

| No. 140 (>106 µm) | Fiber Fines and Resin Residues | 5.21% |

| Under Sieve (<106 µm) | Submicron Dust and Amorphous Debris | 1.96% |

| Definition of PWCs | Loading Fraction | Post-Test Content | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matrix (wt.%) | Thermoset Scraps (wt.%) | |||||

| PS | sPS | Matrix (wt.%) | Glass Fiber (wt.%) | σSD | ||

| PL1 | 90 | 10 | 91.63 | 8.37 | 0.48 | |

| PL2 | 80 | 20 | 83.76 | 16.24 | 0.55 | |

| PL3 | 70 | 30 | 75.96 | 24.05 | 0.63 | |

| PL4 | 60 | 40 | 67.96 | 32.04 | 0.70 | |

| PL5 | 50 | 50 | 59.89 | 40.11 | 0.77 | |

| sPL3 | 70 | - | 30 | 75.68 | 24.32 | 0.58 |

| sPL4 | 60 | - | 40 | 66.96 | 33.05 | 0.63 |

| PH1 | 90 | 10 | 91.48 | 8.52 | 0.42 | |

| PH2 | 80 | 20 | 84.12 | 15.89 | 0.44 | |

| PH3 | 70 | 30 | 75.90 | 24.10 | 0.62 | |

| PH4 | 60 | 40 | 67.33 | 32.67 | 0.79 | |

| PH5 | 50 | 50 | 58.84 | 41.16 | 0.87 | |

| sPH3 | 70 | - | 30 | 76.49 | 23.51 | 0.77 |

| sPH4 | 60 | - | 40 | 68.06 | 31.94 | 0.86 |

| Definition of PWCs | Loading Fraction | Post-Test Content | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matrix (wt.%) | Thermoset Scraps | ||||

| PS | sPS | Density g/cm3 | SD (*) | ||

| PL1 | 90 | 10 | 0.95 | 0.018 | |

| PL2 | 80 | 20 | 1.05 | 0.021 | |

| PL3 | 70 | 30 | 1.10 | 0.022 | |

| PL4 | 60 | 40 | 1.19 | 0.030 | |

| PL5 | 50 | 50 | 1.20 | 0.031 | |

| sPL3 | 70 | 30 | 1.09 | 0.018 | |

| sPL4 | 60 | 40 | 1.17 | 0.031 | |

| PH1 | 90 | 10 | 0.99 | 0.020 | |

| PH2 | 80 | 20 | 1.07 | 0.028 | |

| PH3 | 70 | 30 | 1.12 | 0.030 | |

| PH4 | 60 | 40 | 1.22 | 0.041 | |

| PH5 | 50 | 50 | 1.23 | 0.046 | |

| sPH3 | 70 | 30 | 1.10 | 0.021 | |

| sPH4 | 60 | 40 | 1.19 | 0.035 | |

| Definition of STCs | Initial Mass (g) | Saturated Mass (g) | Coefficient of Determination | Diffusion Coefficient (m2/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PL1 | 8.9039 | 8.9463 | 0.964 | 2.009 × 10−13 |

| PL2 | 8.5855 | 8.6319 | 0.977 | 1.407 × 10−13 |

| PL3 | 8.7014 | 8.7535 | 0.975 | 1.065 × 10−13 |

| PL4 | 8.8557 | 8.9148 | 0.964 | 0.895 × 10−13 |

| PL5 | 8.9658 | 9.0286 | 0.968 | 0.965 × 10−13 |

| sPL3 | 8.8053 | 8.8612 | 0.960 | 1.032 × 10−13 |

| sPL4 | 8.9600 | 9.0236 | 0.974 | 0.412 × 10−13 |

| PH1 | 8.9684 | 9.0272 | 0.962 | 1.735 × 10−13 |

| PH2 | 8.9266 | 8.9898 | 0.954 | 1.822 × 10−13 |

| PH3 | 8.7692 | 8.8409 | 0.968 | 1.978 × 10−13 |

| PH4 | 8.8987 | 8.9786 | 0.971 | 1.477 × 10−13 |

| PH5 | 8.9783 | 9.0775 | 0.957 | 1.966 × 10−13 |

| sPH3 | 8.9150 | 8.9785 | 0.966 | 2.143 × 10−13 |

| sPH4 | 8.8499 | 8.9335 | 0.869 | 1.348 × 10−13 |

| Definition of PWCs | Test Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Break Energy (J) | SD | Izod Impact Strength (kJ/m2) | SD | |

| PL1 | 1.24 | 0.03 | 48.54 | 2.14 |

| PL2 | 1.12 | 0.02 | 43.42 | 1.51 |

| PL3 | 1.05 | 0.03 | 41.27 | 2.13 |

| sPL3 (*) | 1.14 | 0.03 | 46.90 | 1.84 |

| PL4 | 0.83 | 0.02 | 33.17 | 1.46 |

| sPL4 (*) | 0.97 | 0.02 | 39.37 | 1.43 |

| PL5 | 0.61 | 0.08 | 23.58 | 3.04 |

| PH1 | 1.14 | 0.08 | 41.31 | 3.06 |

| PH2 | 0.86 | 0.08 | 31.12 | 2.91 |

| PH3 | 0.70 | 0.08 | 27.62 | 3.45 |

| sPH3 (*) | 0.80 | 0.08 | 28.79 | 3.05 |

| PH4 | 0.48 | 0.08 | 18.65 | 3.19 |

| sPH4 (*) | 0.58 | 0.03 | 21.12 | 1.01 |

| PH5 | 0.41 | 0.10 | 15.98 | 3.98 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kasim, H.; Yan, Y.; Ning, H.; Pillay, S.B. Upcycling Pultruded Polyester–Glass Thermoset Scraps into Polyolefin Composites: A Comparative Structure–Property Insights. J. Compos. Sci. 2026, 10, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010052

Kasim H, Yan Y, Ning H, Pillay SB. Upcycling Pultruded Polyester–Glass Thermoset Scraps into Polyolefin Composites: A Comparative Structure–Property Insights. Journal of Composites Science. 2026; 10(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleKasim, Hasan, Yongzhe Yan, Haibin Ning, and Selvum Brian Pillay. 2026. "Upcycling Pultruded Polyester–Glass Thermoset Scraps into Polyolefin Composites: A Comparative Structure–Property Insights" Journal of Composites Science 10, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010052

APA StyleKasim, H., Yan, Y., Ning, H., & Pillay, S. B. (2026). Upcycling Pultruded Polyester–Glass Thermoset Scraps into Polyolefin Composites: A Comparative Structure–Property Insights. Journal of Composites Science, 10(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010052