Finite Element-Based Methodology for the Evaluation of the Flexural Properties of Cement-Based Nanocomposites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Homogenization Methodology

2.1.1. Orientation Tensor

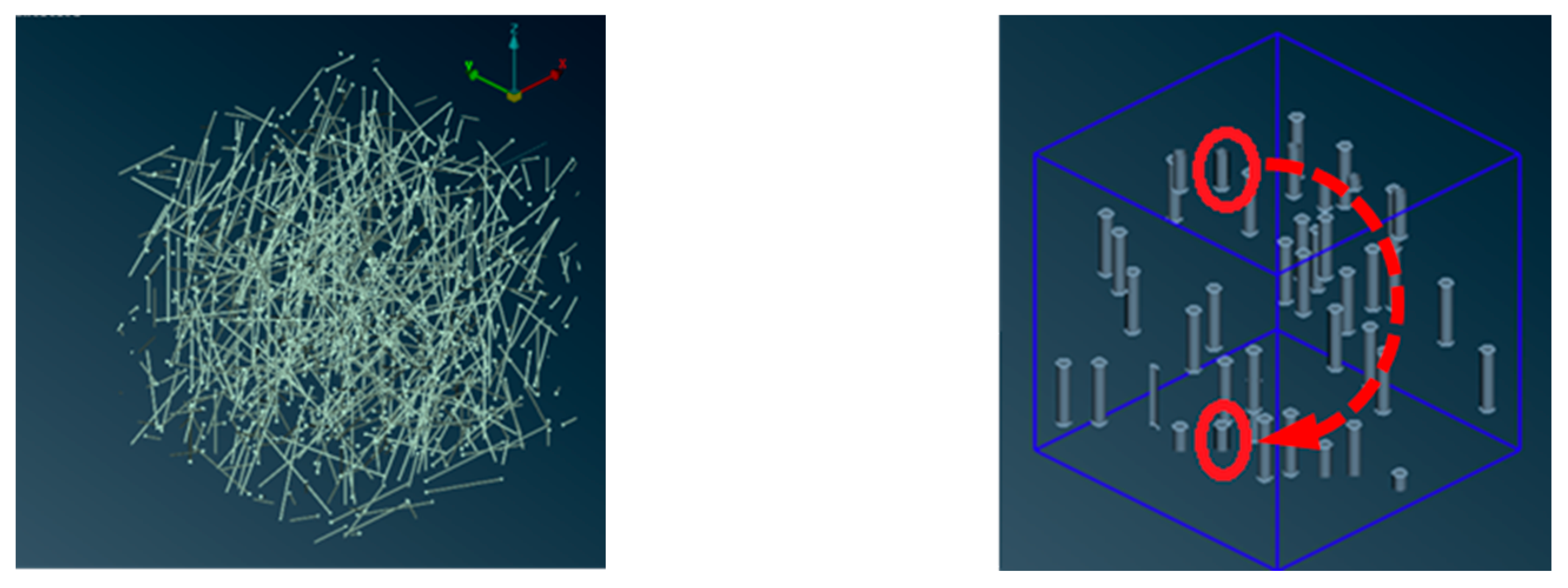

2.1.2. Periodic Geometry Algorithm

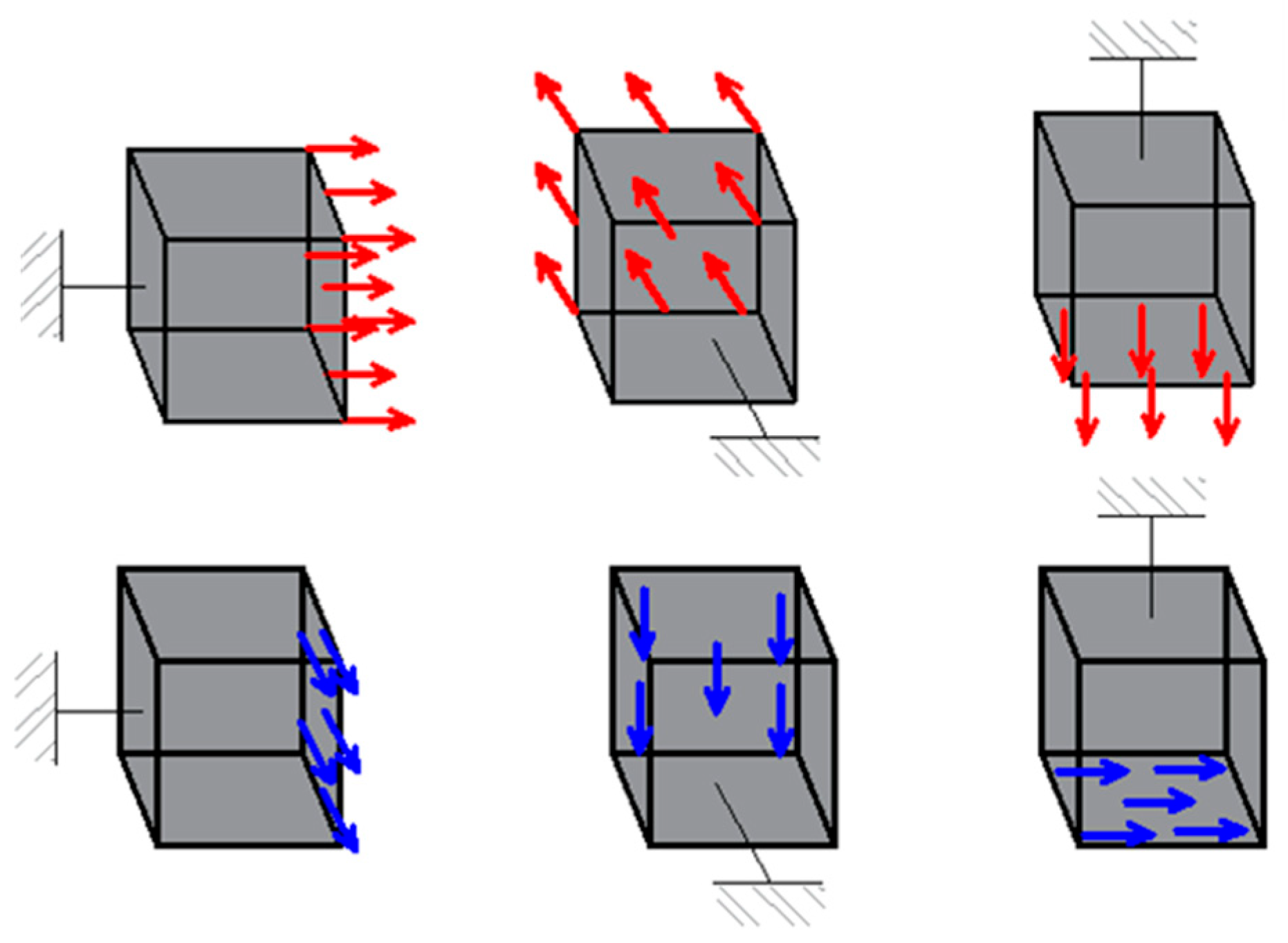

2.1.3. Nano-Scale Homogenization Model

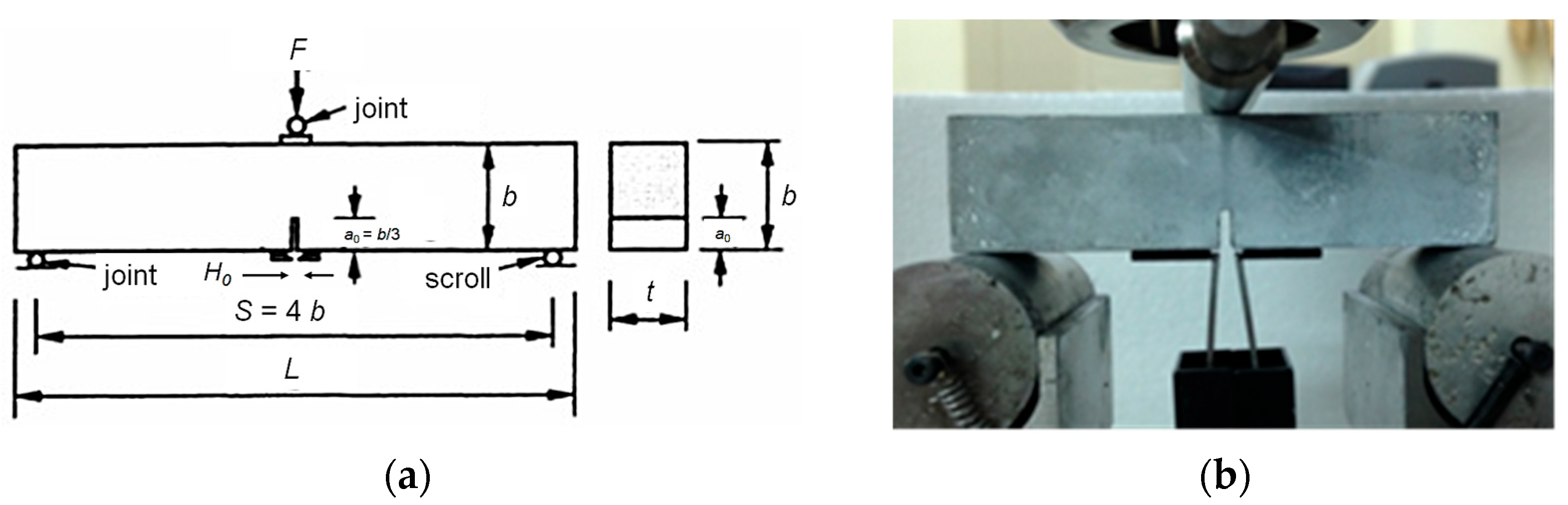

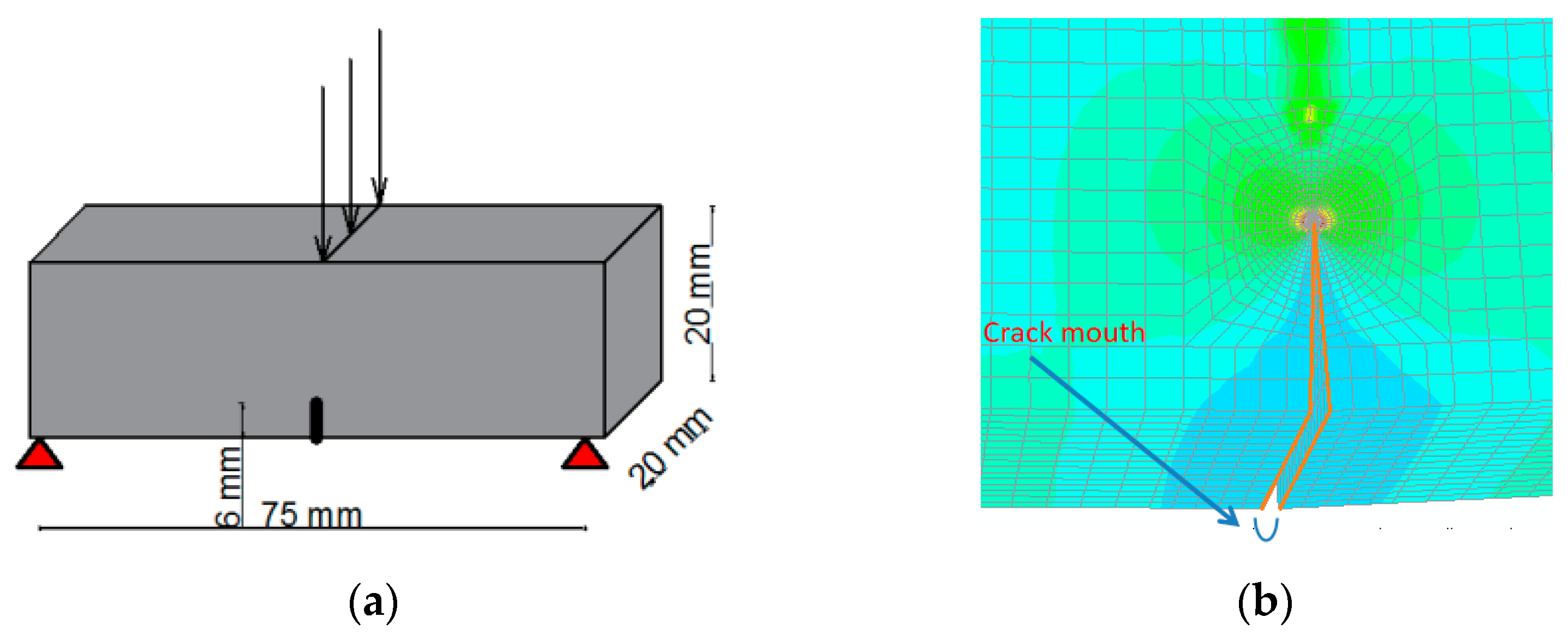

2.2. Finite Element Modelling

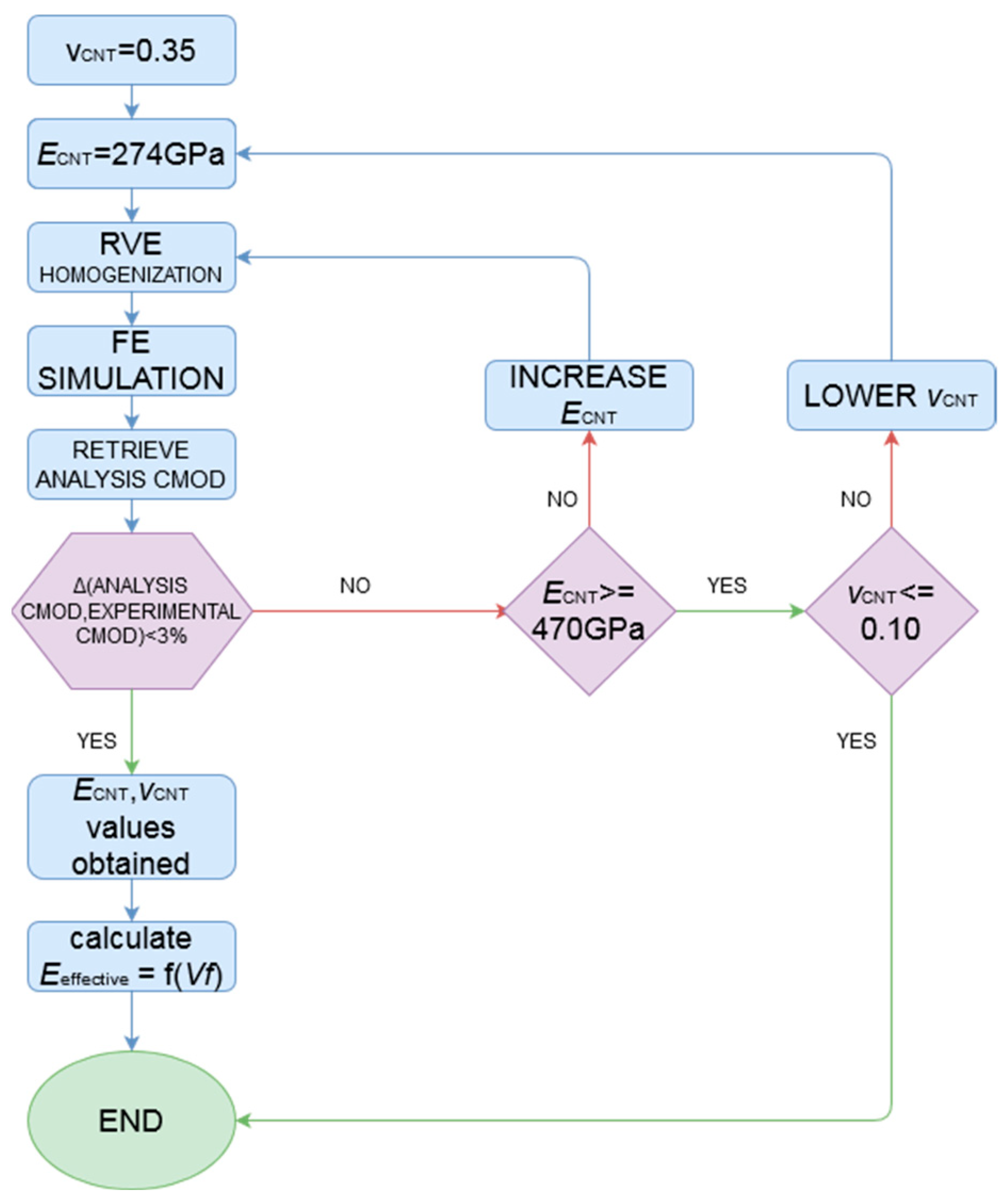

2.3. Research Methodology

- Selection of CNT Poisson’s ratio (starting value is the highest found in literature, i.e., 0.35).

- Selection of CNT effective elastic modulus (ECNT) (starting value is the lowest found in the literature, i.e., 235 GPa according to the results in [32]).

- Calculation of the homogenized material stiffness matrix: RVE finite element along with the random orientation tensor, as described in the previous chapter of homogenization methodology.

- Modelling of the pre-cracked specimens using the homogenized matrix and simulation of the experiment (FE).

- Measurement of CMOD values in the CAE models.

- Comparison of the CMOD values with the experimental results.

- Change to higher CNT effective elastic modulus.

- New loop from step 2 until satisfactory deviation from experimental results (or until reaching non-realistic values of ECNT, with the latter not having been applicable in this paper).

- Change to lower CNT Poisson’s ratio.

- New loop from step 1 until satisfactory deviation from experimental results (or until reaching non-realistic values of νCNT).

- Determination of Poisson’s ratio and effective modulus of elasticity values from results closest to experimental for experimental inclusion volume fractions.

- Expressing the composite material’s Eeff as a function of the inclusion volume fraction (Vf).

3. Results

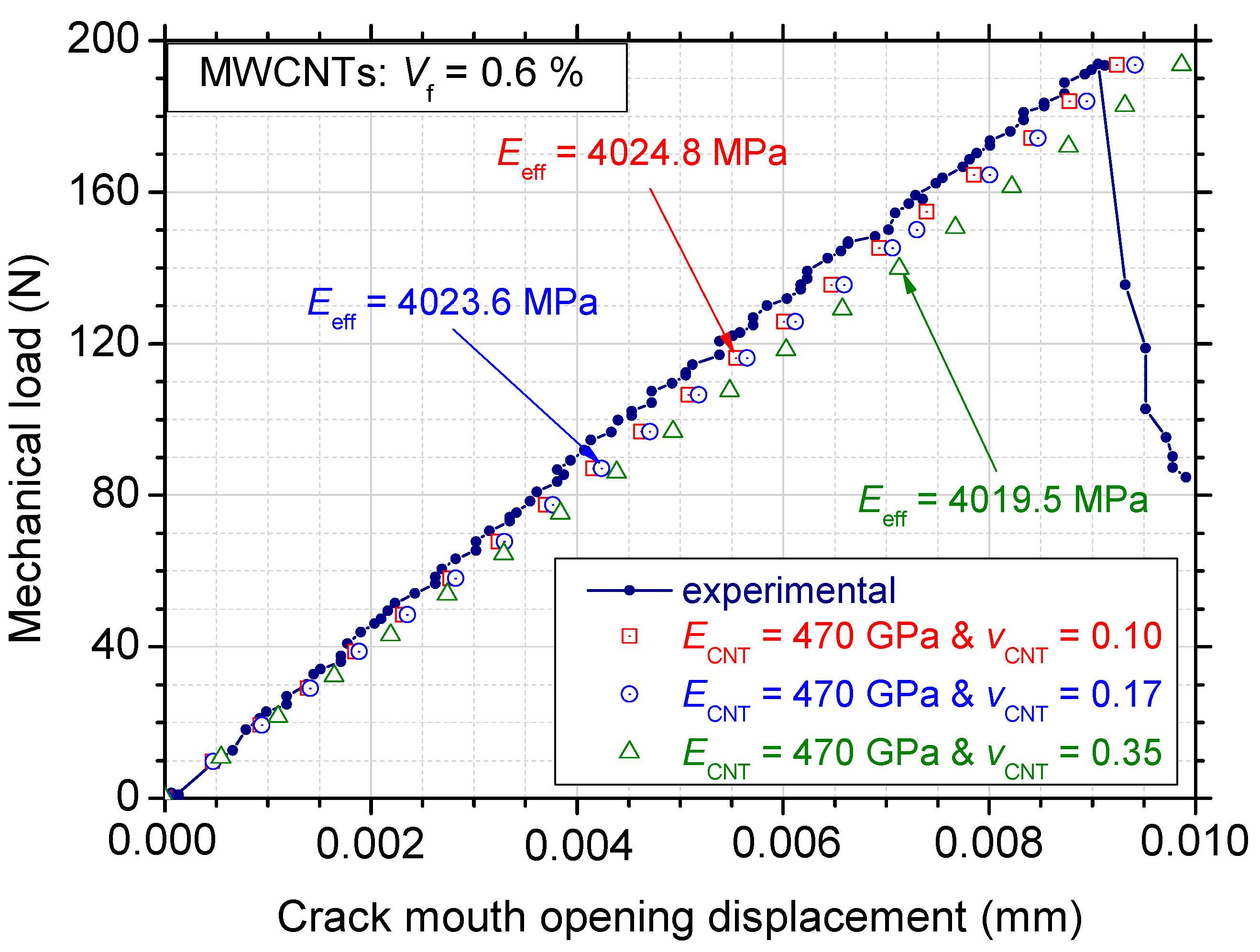

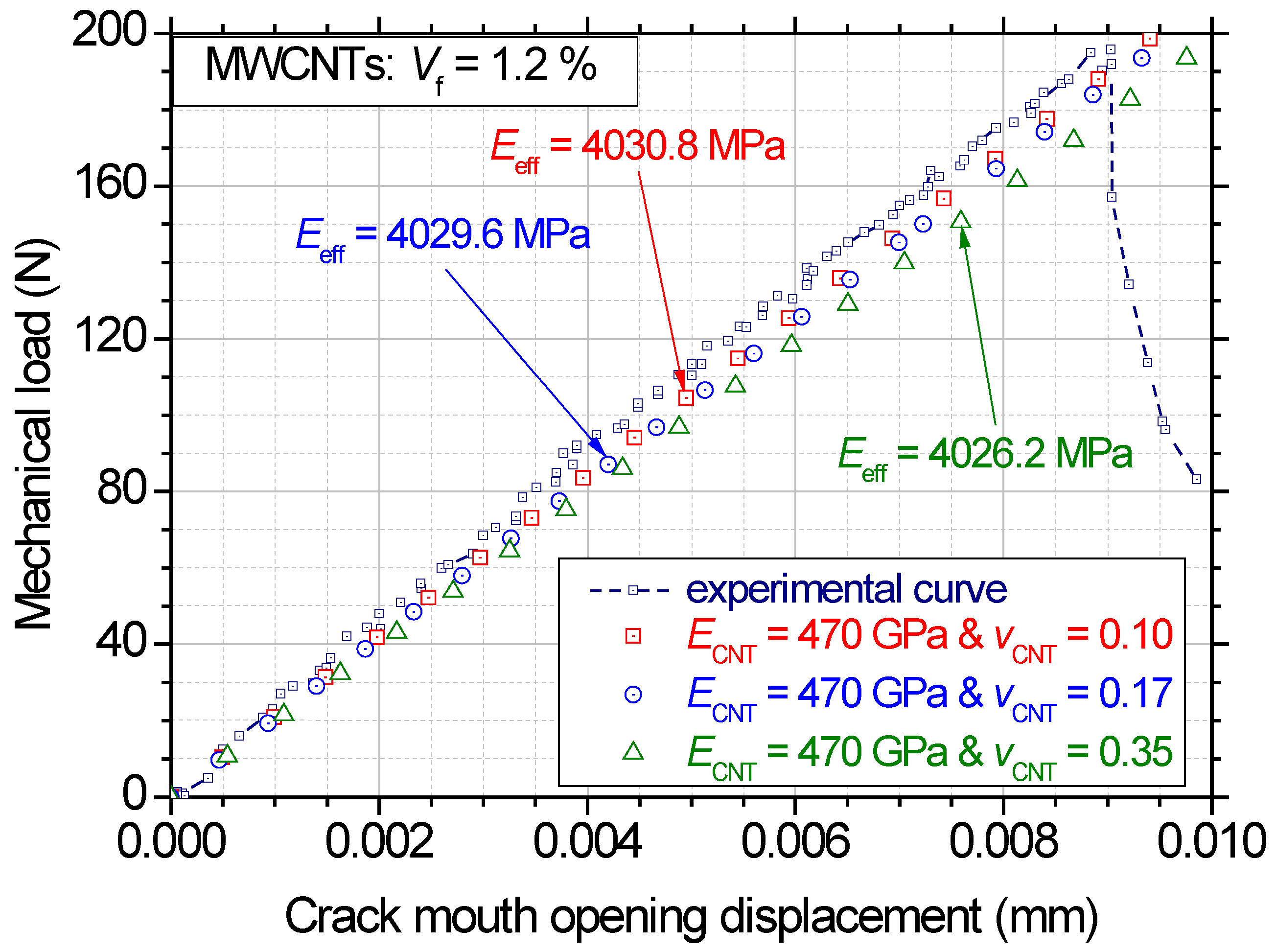

3.1. Effect of the Poisson’s Ratio

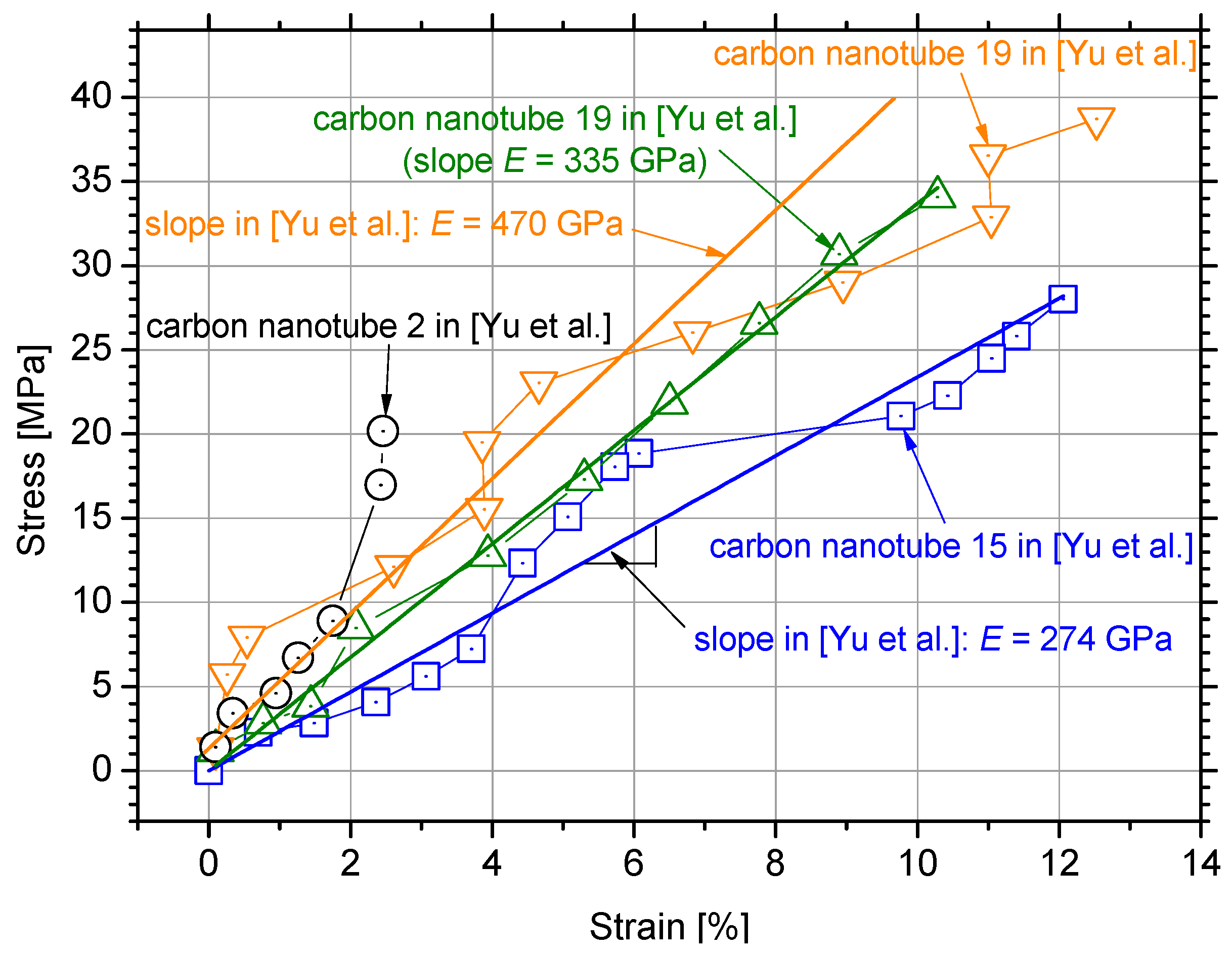

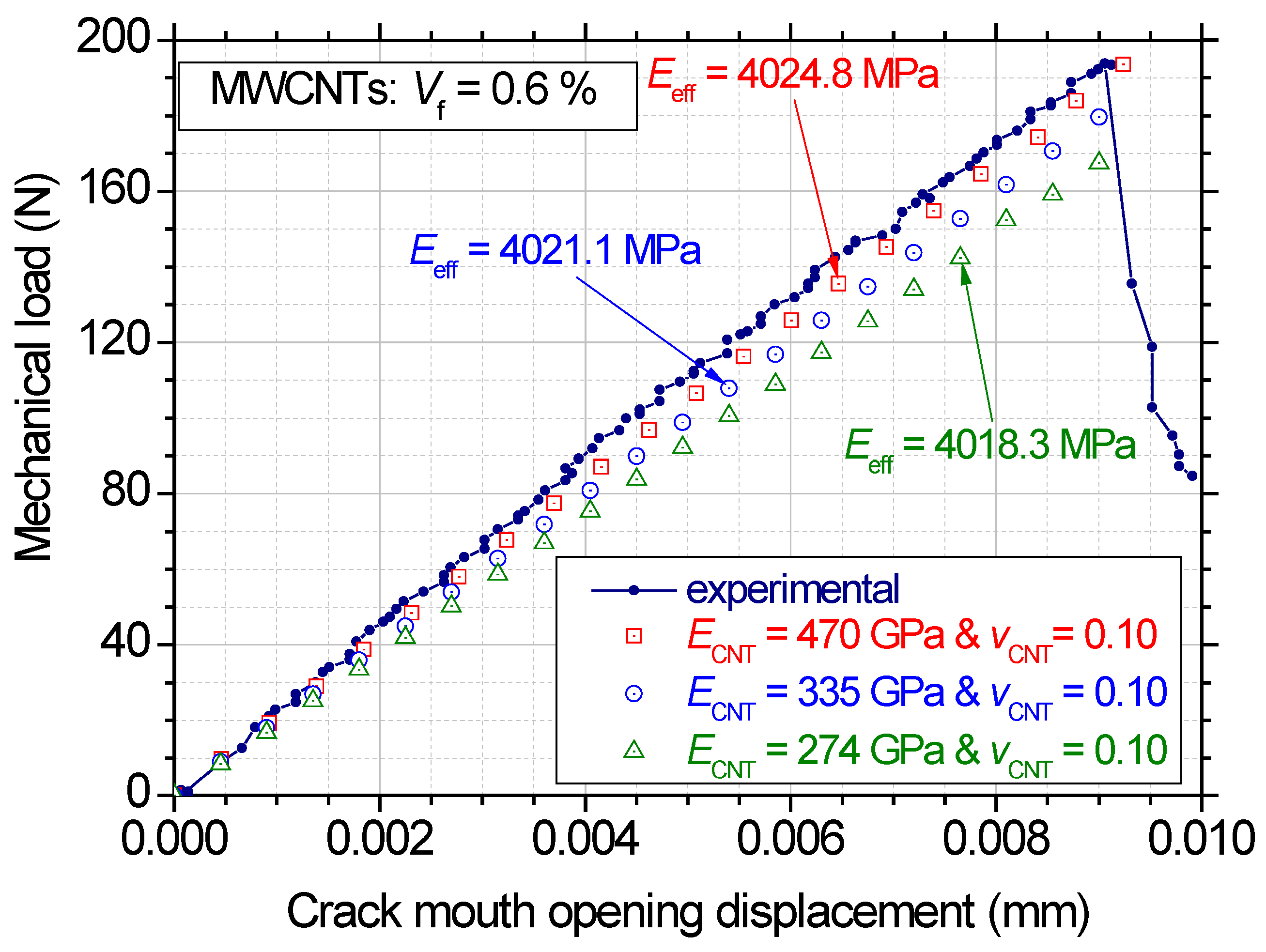

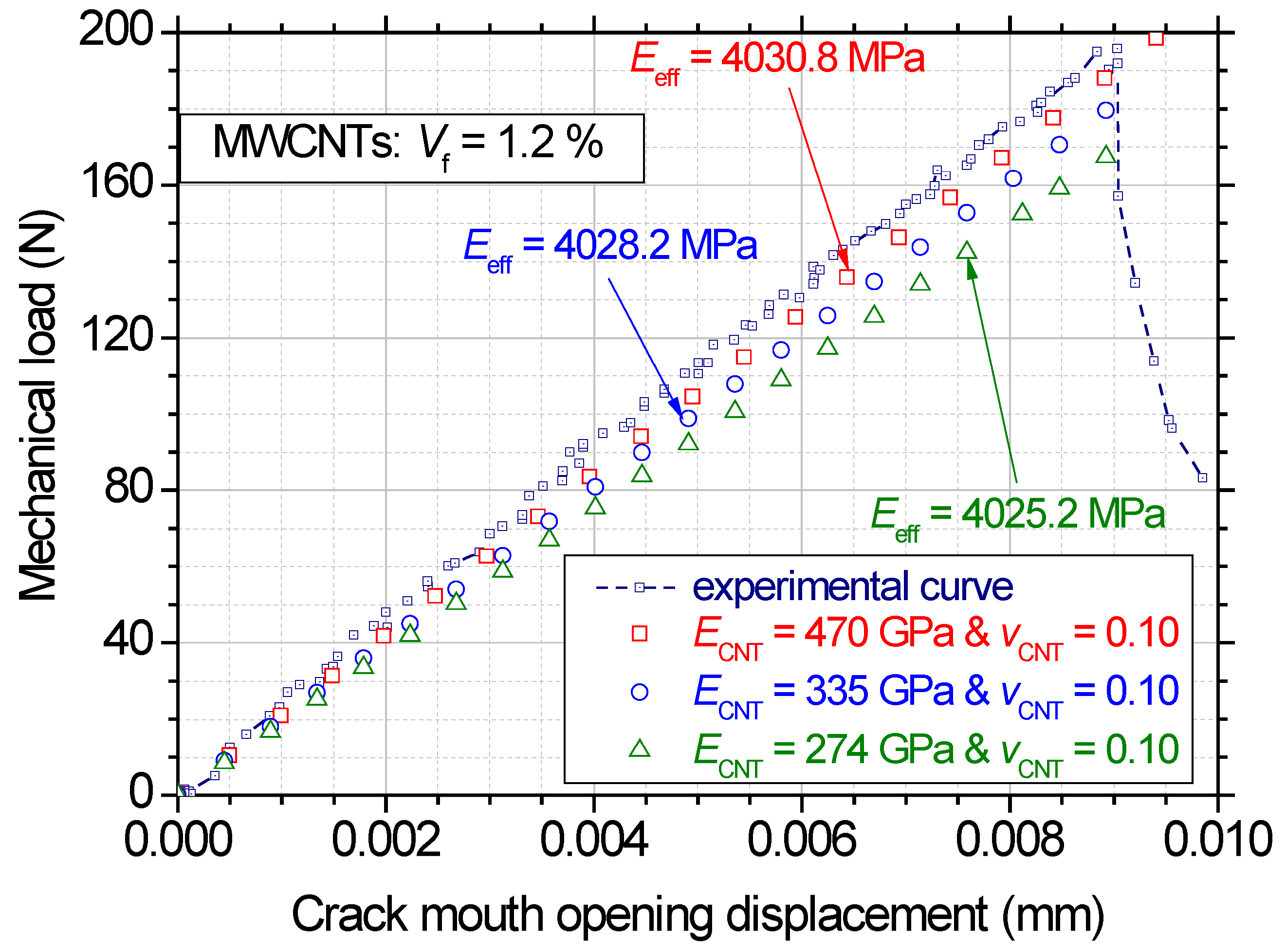

3.2. Investigation on the Role of Effective Elastic Modulus

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chu, K.; Guo, H.; Jia, C.; Yin, F.; Zhang, X.; Liang, X.; Chen, H. Thermal Properties of Carbon Nanotube–Copper Composites for Thermal Management Applications. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2010, 5, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, A.D.; Omrani, E.; Menezes, P.; Rohatgi, P. Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Self-Lubricating Metal Matrix Nanocomposites Reinforced by Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene—A Review. Compos. Part B Eng. 2015, 77, 402–420. [Google Scholar]

- Arash, B.; Wang, Q.; Varadan, V. Mechanical Properties of Carbon Nanotube/Polymer Composites. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loos, M.; Pezzin, S.; Amico, S.; Bergmann, C.; Coelho, L. The Matrix Stiffness Role on Tensile and Thermal Properties of Carbon Nanotubes/Epoxy Composites. J. Mater. Sci. 2008, 43, 6064–6069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ci, L.; Bai, J. The Reinforcement Role of Carbon Nanotubes in Epoxy Composites with Different Matrix Stiffness. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2006, 66, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metaxa, Z.S.; Tolkou, A.K.; Efstathiou, S.; Rahdar, A.; Favvas, E.P.; Mitropoulos, A.C.; Kyzas, G.Z. Nanomaterials in Cementitious Composites: An Update. Molecules 2021, 26, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zou, F.; Sui, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, S.; Lu, S.; Yu, J.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; et al. Dispersion strategies development for high performance carbon nanomaterials reinforced cementitious composites critical review on properties and future challenges. Mater. Des. 2025, 259, 114789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, M.; Pan, G.; Zhou, F.; Mi, R.; Shah, S. In situ grown carbon nanotubes enhanced cement based materials with multifunctionality. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 108, 103518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Zhang, Q.; Sagoe-Crentsil, K.; Duan, W. Graphene oxide coated sand for improving performance of cement composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 124, 104279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.-J.; Gu, Y.-C.; Xing, F.; Khayat, K. Microstructure development and mechanism of hardened cement paste incorporating graphene oxide during carbonation. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 94, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, P.; Elrahman, M.A.; Chung, S.; Cendrowski, K.; Mijowska, E.; Stephan, D. Mechanical and microstructural properties of cement pastes containing carbon nanotubes and carbon nanotube silica core shell structures exposed to elevated temperature. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 95, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshan, M.; Correia, A. Multifunctional cementitious composites from fabrication to their application in pavement a comprehensive review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Feng, X.; Jiang, K.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, M. Recent progress in smart electromagnetic interference shielding materials. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 186, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubyey, L.; Ukrainczyk, N.; Yadav, S.; Izadifar, M.; Schneider, J.; Koenders, E. Carbon nanotubes and nanohorns in geopolymers a study on chemical physical and mechanical properties. Mater. Des. 2024, 240, 112851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulaj, A.; Peeters, S.; Poorsolhjouy, P.; Salet, T.; Lucas, S. Combined analytical and numerical modelling of the electrical conductivity of 3D printed carbon nanotube cementitious nanocomposites. Mater. Des. 2024, 246, 113324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Jing, H.; Gao, Y.; Su, H.; Fang, H. Carbon nanomaterials enhanced cement based composites advances and challenges. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2020, 9, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvandani, M.M.; Mahdikhani, M.; Aghabarati, H.; Fatmehsari, M.H. Effect of functionalized multi walled carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties and durability of cement mortars. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 41, 102407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.J.; Souri, H.; Kim, S.; Ryu, S.; Lee, H.K. An analytical model to predict curvature effects of the carbon nanotube on the overall behavior of nanocomposites. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 116, 033511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, W. Über die Beziehung zwischen den beiden Elastizitätskonstanten isotroper Körper. Wiedemann’s Ann. 1889, 38, 573–587. [Google Scholar]

- Reuss, A. Berechnung der Fließgrenze von Mischkristallen. Z. Angew. Math. Und Phys. 1929, 9, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Eshelby, J. The Determination of the Elastic Field of an Ellipsoidal Inclusion, and Related Problems. Proc. R. Soc. A 1957, 241, 376–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, T.; Tanaka, K. Average Stress in the Matrix and Average Elastic Energy of Materials with Misfitting Inclusions. Acta Metall. 1973, 21, 571–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Wang, Y.; Kitipornchai, S.; Yang, J. Effects of Reorientation of Graphene Platelets on Young’s Modulus of Polymer Nanocomposites under Uni-Axial Stretching. Polymers 2017, 9, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghpour, E.; Guo, Y.; Chua, D.; Shim, V. A Modified Mori–Tanaka Approach Incorporating Filler-Matrix Interface Failure to Model Graphene/Polymer Nanocomposites. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2020, 180, 105699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Yang, S.; Shin, H.; Cho, M. Multiscale Homogenization Model for Thermoelastic Behavior of Epoxy-Based Composites with Polydisperse SiC Nanoparticles. Compos. Struct. 2015, 128, 342–353. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, K.; Mohite, P.; Upadhyay, C. Development of an RVE and Its Stiffness Predictions Based on Mathematical Homogenization Theory for Short Fibre Composites. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2018, 130–131, 80–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Gu, B.; Zhou, J.; Tao, J. Study of the Effectiveness of the RVEs for Random Short Fiber Reinforced Elastomer Composites. Fibers Polym. 2019, 20, 1467–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvas, D.; Stefanou, G.; Papadrakakis, M.; Deodatis, G. Homogenization of Random Heterogeneous Media with Inclusions of Arbitrary Shape Modeled by XFEM. Comput. Mech. 2014, 54, 1221–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M. The Sequential Addition and Migration Method to Generate Representative Volume Elements for the Homogenization of Short Fiber Reinforced Plastics. Comput. Mech. 2017, 59, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. Effect of the Transition Zone on the Elastic Moduli of Mortar. Cem. Concr. Res. 1998, 28, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, E.; Kryvoruk, R. Meso-Scale Analysis of FRC Using a Two-Step Homogenization Approach. Comput. Struct. 2011, 89, 921–929. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, R. A Critical Evaluation for a Class of Micro-Mechanics Models. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1990, 38, 379–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Liew, K. Multiscale Simulation of Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of CNT-Reinforced Cement-Based Composites. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2017, 319, 393–413. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Yuan, Y.; Mang, H. Multiscale Modeling of the Effect of the Interfacial Transition Zone on the Modulus of Elasticity of Fiber-Reinforced Fine Concrete. Comput. Mech. 2015, 55, 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Qsymah, A.; Sharma, R.; Yang, Z.; Margetts, L.; Mummery, P. Micro X-Ray Computed Tomography Image-Based Two-Scale Homogenisation of Ultra High Performance Fibre Reinforced Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 130, 230–240. [Google Scholar]

- Vu-Bac, N.; Rabczuk, T.; Zhuang, X. Continuum/Finite ElementModeling of Carbon Nanotube–Reinforced Polymers. In Carbon Nanotube-Reinforced Polymers; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 385–409. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, L.; Andrawes, B. Characterization of the Uncertainties in the Constitutive Behavior of Carbon Nanotube/Cement Composites. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2009, 10, 045007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, V.; Impraimakis, M. Multiscale Modeling of Carbon Nanotube Reinforced Concrete. Compos. Struct. 2017, 182, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Liew, K. A Multiscale Modeling of CNT-Reinforced Cement Composites. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2016, 309, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavvadias, I.; Tsongas, K.; Bantilas, K.; Falara, M.; Thomoglou, A.; Gkountakou, F.; Elenas, A. Mechanical Characterization of MWCNT-Reinforced Cement Paste: Experimental and Multiscale Computational Investigation. Materials 2023, 16, 5379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konsta-Gdoutos, M.; Metaxa, Z.; Shah, S. Highly Dispersed Carbon Nanotube Reinforced Cement Based Materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2010, 40, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metaxa, Z. Mechanical Behaviour and Durability of Advanced Cement Based Materials. Ph.D. Thesis, Demokrition University of Thrace, Xanthi, Greece, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Metaxa, Z.; Konsta-Gdoutos, M.; Shah, S. Carbon nanotubes reinforced concrete. In SP 267 Nanotechnology of Concrete: The Next Big Thing Is Small; ACI Symposium Publication: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2009; Volume 267, p. 180. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.-F.; Lourie, O.; Dyer, M.; Moloni, K.; Kelly, T.; Ruoff, R. Strength and Breaking Mechanism of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes Under Tensile Load. Science 2000, 287, 637–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poncharal, P.; Wang, Z.; Ugarte, D.; de Heer, W. Electrostatic Deflections and Electromechanical Resonances of Carbon Nanotubes. Science 1999, 283, 1513–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Cheng, H.M.; Bai, S.; Su, G.; Dresselhaus, M.S. Tensile strength of single-walled carbon nanotubes directly measured from their macroscopic ropes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2000, 77, 3161–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demczyk, B.; Wang, Y.; Cumings, J.; Hetman, M.; Han, W.; Zettl, A.; Ritchie, R. Direct Mechanical Measurement of the Tensile Strength and Elastic Modulus of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2002, 334, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K.T.; Chipara, M.; Ling, H.Y.; Hui, D. On the effective elastic moduli of carbon nanotubes for nanocomposite structures. Compos. Part B Eng. 2004, 35, 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM C305; Standard Practice for Mechanical Mixing of Hydraulic Cement Pastes and Mortars of Plastic Consistency. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM C348; Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Hydraulic-Cement Mortars. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- Vandewalle, L.; Nemegeer, D.; Balazs, L.; Barr, B.; Barros, J.; Bartos, P.; Banthia, N.; Criswell, M.; Denarie, E.; Di Prisco, M.; et al. RILEM TC 162-TDF: Test and design methods for steel fibre reinforced concrete. Mater. Struct. 2002, 35, 579–582. [Google Scholar]

- Jenq, Y.; Shah, S. Mixed-Mode Fracture of Concrete. Int. J. Fract. 1988, 38, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSalvo, G.J.; Swanson, J.A. ANSYS Engineering Analysis System User’s Manual; Swanson Analysis Systems: Houston, PA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hashin, Z.; Rosen, B.W. The Elastic Moduli of Fiber-Reinforced Materials. J. Appl. Mech. 1964, 3, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Modulus of Elasticity of the Matrix (Ematrix) | Effective Elastic Modulus of the Reinforcement (ECNT) | Poisson’s Ratio of the MWCNTs (vCNT) | Volume Fraction of the Reinforcement (Vf) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4000 MPa | 274 GPa | 0.10 | 0.6% |

| 2 | 4000 MPa | 335 GPa | 0.10 | 0.6% |

| 3 | 4000 MPa | 470 GPa | 0.10 | 0.6% |

| 4 | 4000 MPa | 274 GPa | 0.17 | 0.6% |

| 5 | 4000 MPa | 335 GPa | 0.17 | 0.6% |

| 6 | 4000 MPa | 470 GPa | 0.17 | 0.6% |

| 7 | 4000 MPa | 274 GPa | 0.17 | 0.6% |

| 8 | 4000 MPa | 335 GPa | 0.17 | 0.6% |

| 9 | 4000 MPa | 470 GPa | 0.17 | 0.6% |

| 10 | 4000 MPa | 274 GPa | 0.35 | 0.6% |

| 11 | 4000 MPa | 335 GPa | 0.35 | 0.6% |

| 12 | 4000 MPa | 470 GPa | 0.35 | 0.6% |

| 13 | 4000 MPa | 274 GPa | 0.10 | 1.2% |

| 14 | 4000 MPa | 335 GPa | 0.10 | 1.2% |

| 15 | 4000 MPa | 470 GPa | 0.10 | 1.2% |

| 16 | 4000 MPa | 274 GPa | 0.17 | 1.2% |

| 17 | 4000 MPa | 335 GPa | 0.17 | 1.2% |

| 18 | 4000 MPa | 470 GPa | 0.17 | 1.2% |

| 19 | 4000 MPa | 274 GPa | 0.17 | 1.2% |

| 20 | 4000 MPa | 335 GPa | 0.17 | 1.2% |

| 21 | 4000 MPa | 470 GPa | 0.17 | 1.2% |

| 22 | 4000 MPa | 274 GPa | 0.35 | 1.2% |

| 23 | 4000 MPa | 335 GPa | 0.35 | 1.2% |

| 24 | 4000 MPa | 470 GPa | 0.35 | 1.2% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Anastopoulos, S.; Givannaki, F.; Papanikos, P.; Metaxa, Z.S.; Alexopoulos, N.D. Finite Element-Based Methodology for the Evaluation of the Flexural Properties of Cement-Based Nanocomposites. J. Compos. Sci. 2026, 10, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010017

Anastopoulos S, Givannaki F, Papanikos P, Metaxa ZS, Alexopoulos ND. Finite Element-Based Methodology for the Evaluation of the Flexural Properties of Cement-Based Nanocomposites. Journal of Composites Science. 2026; 10(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnastopoulos, Stylianos, Faidra Givannaki, Paraskevas Papanikos, Zoi S. Metaxa, and Nikolaos D. Alexopoulos. 2026. "Finite Element-Based Methodology for the Evaluation of the Flexural Properties of Cement-Based Nanocomposites" Journal of Composites Science 10, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010017

APA StyleAnastopoulos, S., Givannaki, F., Papanikos, P., Metaxa, Z. S., & Alexopoulos, N. D. (2026). Finite Element-Based Methodology for the Evaluation of the Flexural Properties of Cement-Based Nanocomposites. Journal of Composites Science, 10(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010017