Development of a Speech-in-Noise Test in European Portuguese Based on QuickSIN: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- Sentence Drafting: An initial set of 165 sentences was drafted based on the structure and principles of the QuickSIN test, with each sentence containing exactly five target keywords. Sentences were designed to be semantically coherent, syntactically correct, and phonetically representative of European Portuguese. Care was taken to ensure natural sentence length, everyday vocabulary, and diversity in sentence construction to reflect realistic speech patterns.

- -

- Semantic and Syntactic Evaluation: The drafted sentences were evaluated by fifteen native European Portuguese speakers for semantic and syntactic appropriateness. Each sentence was rated on a 1–3 scale (1 = poor, 2 = acceptable, 3 = excellent). Inter-rater reliability was calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient, ensuring consistent and reliable ratings across evaluators. Sentences achieving an average score above 2.5 were retained for the next phase. This rigorous evaluation ensured that only linguistically accurate and natural-sounding sentences were included, minimizing the risk of comprehension difficulties unrelated to noise perception during later testing.

- -

- Final Selection, Recording, and Intelligibility Testing: From the evaluated sentences, 120 were selected for the final test. These sentences were recorded using a female voice in the Audiology Laboratory of the School of Health Technology of Coimbra, with Audacity3.7.4 (https://www.audacityteam.org/, accessed on 9 January 2022). Recordings were conducted in a quiet environment, ensuring consistent speech rate, natural intonation, and clear articulation of all keywords, producing high-quality audio suitable for subsequent testing and signal-to-noise ratio calibration.

- -

- Sentence Grouping and Phoneme Balancing: The selected sentences were organized into fifteen sets of six, carefully designed to ensure that the distribution of phonemes within each set reflected their natural occurrence in European Portuguese. This balancing process maintained linguistic representativeness and phonetic diversity, preventing bias toward specific sounds or syllables. Each set thus provided a consistent and reliable measure of speech perception across all phonemes, supporting accurate assessment of participants’ ability to recognize speech in noise [15].

- -

- Noise Addition and SNR (dB) Calibration: Each sentence set was mixed with multi-talker babble noise, specifically developed from recordings of European Portuguese speakers, using Audacity® software. Root Mean Square levels of speech and noise tracks were measured, and gains were adjusted to achieve target SNR (dB) of 0, 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25. SNR (dB) levels were verified across multiple sentences to ensure accuracy within ±0.5 dB, maintaining consistent mixing and gradual increases in listening difficulty from easy (25 SNR (dB)) to highly challenging conditions (0 SNR (dB)). This approach ensured that the test materials spanned the full range of listening difficulty, enabling precise assessment of speech perception in noise. Special care was taken to maintain consistent mixing levels, preserve sentence intelligibility at higher SNRs (dB), and ensure a gradual and controlled increase in listening difficulty across the SNR (dB) spectrum.

- -

- Pre-Test: The pre-test was conducted in a free-field environment at 65 dB SPL in the Audiology Laboratory of the Coimbra Health School. Fifteen normal-hearing adults (hearing thresholds ≤ 20 dB HL at 500–8000 Hz), with type A tympanograms and present ipsilateral and contralateral reflexes at 1000 Hz, participated in this phase. Participants were aged 18–22 years (3 males and 12 females) and had no cognitive impairments. Each participant was instructed to listen carefully and repeat every sentence they heard. The responses were recorded, and the number of correctly repeated keywords was tallied for each sentence. From these data, the percentage of correctly repeated keywords was calculated for each signal-to-noise ratio (SNR (dB)), providing a quantitative measure of sentence intelligibility and guiding the final selection of sentences for the test.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Os, M.; Kray, J.; Demberg, V. Rational Speech Comprehension: Interaction between Predictability, Acoustic Signal, and Noise. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 914239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shechter Shvartzman, L.; Lavie, L.; Banai, K. Speech Perception in Older Adults: An Interplay of Hearing, Cognition, and Learning? Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 816864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Ferreiro, M.; Durán-Bouza, M.; Marrero-Aguiar, V. Design and Development of a Spanish Hearing Test for Speech in Noise (PAHRE). Audiol. Res. 2023, 13, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfer, K.S.; Jesse, A. Hearing and Speech Processing in Midlife. Hear. Res. 2021, 402, 108097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pienkowski, M. On the Etiology of Listening Difficulties in Noise Despite Clinically Normal Audiograms. Ear Hear. 2017, 38, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, C.J.; Olsen, T.M.; Charney, L.; Madsen, B.M.; Holmes, C.E. Speech-in-Noise Testing: An Introduction for Audiologists. Semin. Hear. 2024, 45, 55–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendel, L.L. Objective and Subjective Hearing Aid Assessment Outcomes. Am. J. Audiol. 2007, 16, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, O.A.; Elmahallawy, T.H.; Kolkaila, E.A.; Lasheen, R.M. Comparison between Quick Speech in Noise Test (QuickSIN) and Hearing in Noise Test (HINT) in Adults with Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Egypt. J. Ear Nose Throat Allied Sci. 2020, 21, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.H.; McArdle, R.A.; Smith, S.L. An Evaluation of the BKB-SIN, HINT, QuickSIN, and WIN Materials on Listeners with Normal Hearing and Hearing Loss. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2007, 50, 844–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, A.; Marrone, N.; Souza, P. Hearing Aid Technology Settings and Speech-in-Noise Difficulties. Am. J. Audiol. 2022, 31, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killion, M.C.; Niquette, P.A.; Gudmundsen, G.I.; Revit, L.J.; Banerjee, S. Development of a Quick Speech-in-Noise Test for Measuring Signal-to-Noise Ratio Loss in Normal-Hearing and Hearing-Impaired Listeners. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2004, 116, 2395–2405, Erratum in J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2006, 119, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzaquén, E.; Çolak, H.; Guo, X.; Lad, M.; Rushton, S.P.; Griffiths, T.D. Auditory-cognitive contributions to speech-in-noise perception determined with structural equation modelling of a large sample. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutler, A. Native Listening: Language Experience and the Recognition of Spoken Words; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, M.; Soli, S.D.; Sullivan, J.A. Development of the Hearing in Noise Test for the measurement of speech reception thresholds in quiet and in noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1994, 95, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, A.P.; Moreira, M.; Costa, A.; Murtinheira, A.; Jorge, A. Validade e Sensibilidade do Texto Fonetically Equilibrado para o Português-Europeu ‘O Sol’. Distúrb. Comun. 2014, 26, 277–286. [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk Karaburun, S.; Çiprut, A.A.; Akdeniz, E. Development of a Quick Speech in Noise Test in Turkish, Based on Quick-SIN. Egypt. J. Otolaryngol. 2025, 41, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, R.A.; Wilson, R.H. Homogeneity of the 18 QuickSIN Lists. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2006, 17, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynard, P.; Lagacé, J.; Joly, C.A.; Dodelé, L.; Veuillet, E.; Thai-Van, H. Speech-in-Noise Audiometry in Adults: A Review of the Available Tests for French Speakers. Audiol. Neurootol. 2022, 27, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, F.; Renard, C.; Vincent, C. Speech Audiometry in Noise: Development of the French-Language VRB (Vocale Rapide dans le Bruit) Test. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2018, 135, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiani, H.E.; Serra, V.; Guinguis, M. Development of a Quick Speech-in-Noise Test in “Rioplatense” Spanish, Based on Quick-SIN®. J. Phonet. Audiol. 2020, 6, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, W.L. Assessing the Correlation Between Hearing Sensitivity and Quick Speech-in-Noise Test (QuickSIN) Performance: The Role of Extended High-Frequency Hearing and Conventional Frequency Range Hearing. Ph.D. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zekveld, A.A.; Rudner, M.; Johnsrude, I.S.; Festen, J.M.; Van Beek, J.H.; Rönnberg, J. The Influence of Semantically Related and Unrelated Text Cues on the Intelligibility of Sentences in Noise. Ear Hear. 2011, 32, e16–e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brungart, D.S.; Sheffield, B.M.; Kubli, L.R. Development of a Test Battery for Evaluating Speech Perception in Complex Listening Environments. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2014, 136, 777–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Set | Mean | Median | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 46.7 | 40 | 27.9 | 0–100 |

| 2 | 18.7 | 20 | 20.7 | 0–60 |

| 3 | 21.3 | 20 | 16.0 | 0–40 |

| 4 | 45.3 | 60 | 37.4 | 0–100 |

| 5 | 18.7 | 0 | 34.2 | 0–100 |

| 6 | 50.7 | 60 | 12.8 | 20–60 |

| 7 | 42.7 | 40 | 23.7 | 0–80 |

| 8 | 41.3 | 40 | 38.9 | 0–100 |

| 9 | 34.7 | 20 | 38.1 | 0–100 |

| 10 | 73.3 | 60 | 19.5 | 40–100 |

| 11 | 34.7 | 20 | 35.8 | 0–100 |

| 12 | 18.7 | 20 | 27.7 | 0–100 |

| 13 | 74.7 | 80 | 31.6 | 0–100 |

| 14 | 85.3 | 80 | 14.1 | 60–100 |

| 15 | 72.0 | 80 | 19.7 | 20–100 |

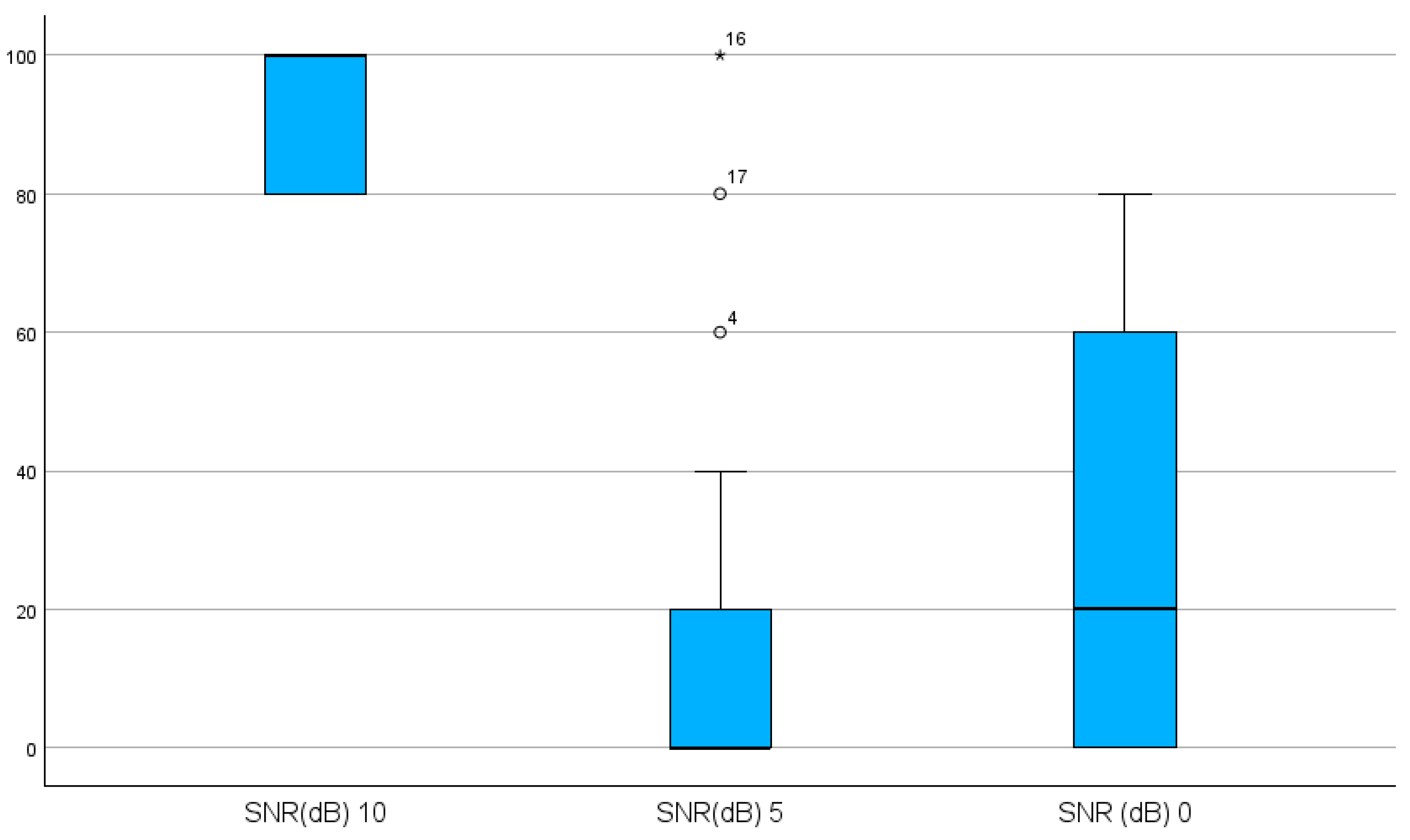

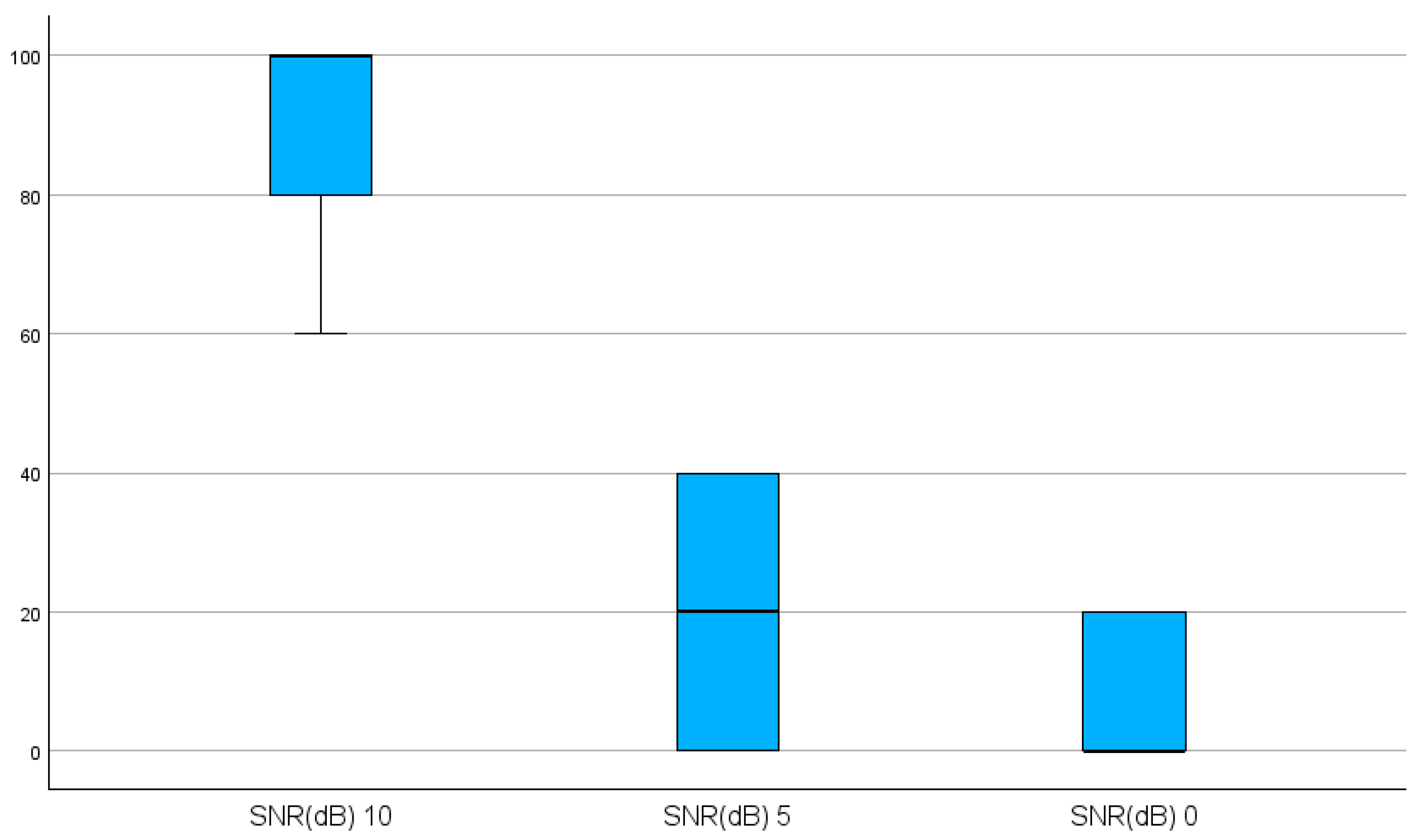

| SNR (dB) | Mean | Median | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 93.3 | 100 | 9.8 | 80–100 |

| 5 | 18.7 | 0 | 34.2 | 0–100 |

| 0 | 33.3 | 40 | 34.4 | 0–80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Serrano, M.; Simões, J.; Vicente, J.; Ferreira, M.; Murta, A.; Ferrão, J.T. Development of a Speech-in-Noise Test in European Portuguese Based on QuickSIN: A Pilot Study. J. Otorhinolaryngol. Hear. Balance Med. 2025, 6, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ohbm6020022

Serrano M, Simões J, Vicente J, Ferreira M, Murta A, Ferrão JT. Development of a Speech-in-Noise Test in European Portuguese Based on QuickSIN: A Pilot Study. Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, Hearing and Balance Medicine. 2025; 6(2):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ohbm6020022

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerrano, Margarida, Jéssica Simões, Joana Vicente, Maria Ferreira, Ana Murta, and João Tiago Ferrão. 2025. "Development of a Speech-in-Noise Test in European Portuguese Based on QuickSIN: A Pilot Study" Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, Hearing and Balance Medicine 6, no. 2: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ohbm6020022

APA StyleSerrano, M., Simões, J., Vicente, J., Ferreira, M., Murta, A., & Ferrão, J. T. (2025). Development of a Speech-in-Noise Test in European Portuguese Based on QuickSIN: A Pilot Study. Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, Hearing and Balance Medicine, 6(2), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ohbm6020022