Abstract

Background/Objectives: Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) is characterized by calcification and ossification of ligaments and tendons, primarily affecting the spine. While often asymptomatic, DISH in the cervical spine can cause dysphagia and, more rarely, vocal cord paralysis due to compression of the recurrent laryngeal nerve at the cricothyroid joint. Here, we report cases of unilateral vocal fold paresis in two patients with DISH. Case Presentation: Our first case is an 80-year-old male presented with two months of dysphonia. Strobovideolaryngoscopy found left vocal fold paresis with glottic insufficiency. Computed Tomography (CT) imaging showed DISH with large anteriorly projecting osteophytes in the cervical spine causing rightward deviation of the laryngeal structures and compressing the cricothyroid joint. Second, a 30-year-old female with Turner Syndrome and subglottic stenosis who developed progressively worsening dysphonia over 6 months, characterized by diminished voice projection and clarity. Strobovideolaryngoscopy revealed a mild-to-moderate right vocal fold paresis. CT of the neck demonstrated multiple right-sided osteophytes projecting into the right tracheoesophageal groove, along the course of the right recurrent laryngeal nerve, in the absence of significant disc degeneration. Discussion and Conclusions: On our review of the literature, no other similar instances of unilateral vocal fold paresis were found. We present these cases to emphasize the need for early recognition and treatment to prevent symptom progression of DISH.

1. Introduction

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH), also known as ankylosing spondyloproliferative or Forestier disease, is a condition characterized by the calcification and ossification of ligaments and tendons, primarily affecting the spine [1]. While often asymptomatic, DISH can lead to complications such as dysphagia and, more rarely, recurrent laryngeal nerve injury and associated vocal cord immobilization or paresis due to compression at the cricothyroid joint [2,3,4,5,6]. Vocal fold immobilization is defined as complete lack of movement (which can be due to complete paralysis or joint ankylosis) whereas vocal fold paresis is defined as partial movement. These symptoms may significantly impact airway safety, phonation, and quality of life, resulting in functional limitations that can be socially and professionally disabling for some patients. Such morbidity highlights the clinical relevance of recognizing DISH early. Case reports in literature have described unilateral immobilization and bilateral vocal cord paresis or immobilization with DISH [2,3,4,5,6]. However, to our knowledge, no prior publications have described isolated unilateral vocal cord paresis caused by cervical DISH in the absence of contralateral dysfunction. To this end, we present the first reported cases of two patients with DISH causing unilateral vocal cord paresis, thereby expanding the recognized clinical spectrum of this disease and highlighting the importance of early recognition in preventing irreversible laryngeal dysfunction.

2. Case Report

2.1. Case A

An 80-year-old male presented to our outpatient otolaryngology clinic in July 2024 with a two-month history of dysphonia. The patient complained of difficulty with both projection and clarity of voice. His past medical history was significant for a 65-year smoking history and longstanding emphysema.

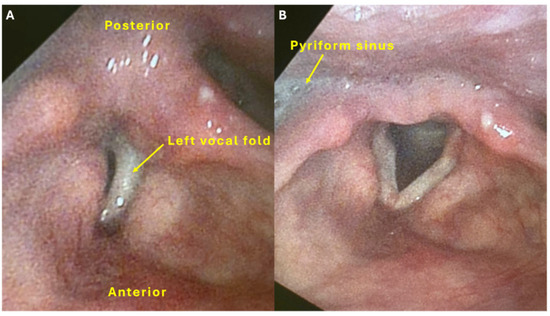

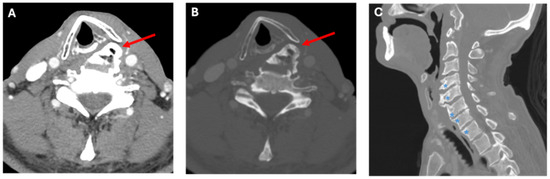

The patient’s voice handicap index (VHI) score was 28/40, and his singing voice handicap index was 30/40. Strobovideolaryngoscopy found moderate paresis of the left vocal fold with glottic insufficiency as well as pyriform sinus pooling (Figure 1A,B). CT imaging found numerous radiographic features consistent with a diagnosis of DISH and showed large anteriorly projecting osteophytes in the cervical spine, eccentric to the left (Figure 2A–C). In particular, a large osteophyte extended anteriorly to the left at C5–6, towards the larynx, along the posterior aspect of the left thyroid cartilage, with rightward deviation of the laryngeal structures and hypopharynx (Figure 2A–C). Flexible laryngoscopy with injection augmentation of the left vocal fold with carboxymethylcellulose gel was performed for symptomatic relief and a referral to a spine specialist was made for DISH management. The patient tolerated the injection augmentation well, without complication, and reported complete symptom resolution at subsequent follow-up. The patient did not elect for further management of his osteophytes at this time.

Figure 1.

Strobovideolaryngoscopy views of the larynx prior to injection augmentation for Case A. (A) Attempted phonation showing bowing of the left vocal fold and secondary/compensatory hypercontraction of the right false vocal fold with continued glottic insufficiency. (B) Inspiration. There is pooling of secretions in the pyriform sinus.

Figure 2.

Computed Tomography images for Case A. CT images in axial soft tissue (A), axial bone window (B), and sagittal bone window (C) reconstructions. Images demonstrate a large left endplate osteophyte (red arrow), which projects into the left cricothyroid joint in a patient with left vocal cord palsy. The sagittal image shows multi-level bulky endplate osteophyte formation (blue asterisk), without substantial disc degeneration, in keeping with findings of DISH.

2.2. Case B

A 30-year-old female who had previously been followed for subglottic stenosis, re-presented to our outpatient otolaryngology clinic in June 2024 with a six-month history of progressively worsening dysphonia, characterized by diminished voice projection and clarity. Her medical history was notable for gastroesophageal reflux disease and Turner syndrome. She was a lifelong non-smoker with no history of alcohol or drug use. The patient had undergone seven previous direct laryngoscopies with subglottic dilation and steroid injections. She had previously been noted to have mild right vocal fold paresis since November 2021; however, as she was asymptomatic at the time, she did not pursue further evaluation or treatment.

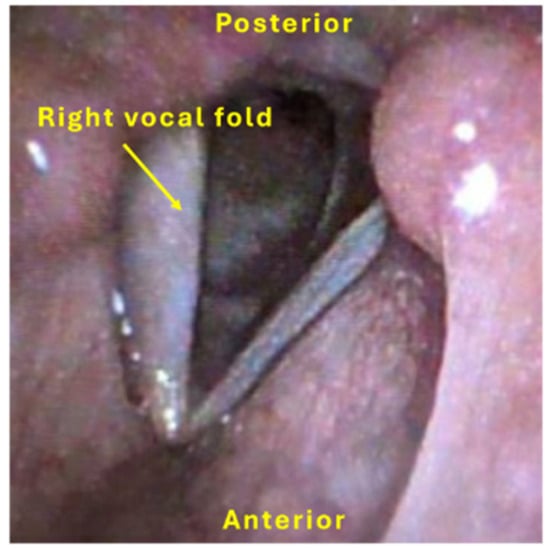

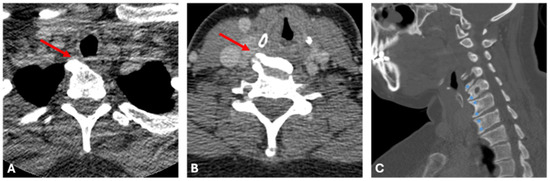

At this presentation, her VHI score was 17/40. Strobovideolaryngoscopy revealed mild (10–20%) subglottic stenosis with anterior and posterior shelf formation (Figure 3). A right cervical osteophyte was visualized, and moderate to severe right vocal fold paresis was noted, though glottic closure remained complete. CT of the neck demonstrated multiple right-sided osteophytes projecting into the right tracheoesophageal groove, along the course of the right recurrent laryngeal nerve, in the absence of significant disc degeneration (Figure 4A–C). These findings were consistent with DISH. The patient was referred to speech therapy for voice rehabilitation and counselled regarding potential injection laryngoplasty should symptoms persist or worsen. Subglottic stenosis remained unchanged on follow-up evaluation. The patient did not elect for further management of her osteophytes at this time.

Figure 3.

Strobovideolaryngoscopy views of the larynx for Case B. Attempted phonation showing right vocal fold paresis.

Figure 4.

Computed Tomography images for Case B. Axial soft tissue window CT images (A,B) demonstrate multi-level right-sided endplate osteophytes (red arrow) which project into the right tracheo-esophageal groove, along the expected course of the right recurrent laryngeal nerve, in this patient with right vocal cord paresis. Sagittal image (C) demonstrates multi-level bulky endplate osteophyte formation (blue asterisk), in the absence of significant disc degeneration, in keeping with DISH.

3. Discussion

DISH was first described as “senile vertebral ankylosing hyperostosis” by Forestier and Rotes-Querol in 1950 [7]. It is characterized by the ossification of the anterior longitudinal spinal ligament—with large osteophytes throughout the spine creating its “typical candle wax” appearance [8]. It is most commonly observed in males and is related to older age [3]. The exact pathophysiology of DISH remains unclear, though various mechanisms have been proposed. Metabolic derangements, particularly hyperinsulinemia and elevated growth factors, are thought to play a role in abnormal bone formation [9]. These mechanisms may explain the frequent association of DISH with obesity, diabetes, gout, and hyperlipidemia, and underscore the importance of considering systemic comorbidities in affected patients [3,10]. In light of the unclear etiology and frequently nonspecific clinical findings, accurate imaging plays a central role in establishing the diagnosis of DISH and assessing its anatomic extent. Imaging, particularly bone window CT scans, is considered the gold standard for diagnosing DISH [11]. Diagnostic criteria involve the presence of calcification of the anterior longitudinal ligament spanning at least four contiguous vertebrae, the absence of degenerative changes in the interposed vertebral discs, and the absence of ankylosis or arthritic changes [1].

DISH can present with vocal fold immobility (i.e., dysphonia, dysphagia, stridor) and respiratory difficulties due to compression of the esophagus and/or recurrent laryngeal nerve by cervical osteophytes [2,3,4,5,6]. The recurrent laryngeal nerve, which innervates all intrinsic muscles of the larynx except the cricothyroid, courses through the tracheoesophageal groove before entering the larynx. In DISH, prominent cervical osteophytes—especially at C4–C6—can cause chronic extrinsic compression, inflammation, or tethering of the nerve. Over time, this may compromise the nerve’s blood supply and function, leading to neuropraxia or axonotmesis and manifesting as progressive paresis. Unlike central neurologic lesions, DISH-induced recurrent laryngeal nerve dysfunction is mechanical and potentially reversible with early identification.

DISH can be managed through either conservative medical treatment or surgical intervention, depending on the severity of symptoms and the presence of structural complications. Medical management focuses on symptomatic relief, after ruling out secondary causes [3]. This could consist of physical and swallowing therapy, with or without analgesics, corticosteroids, anti-reflux drugs, or muscle relaxants. In more complex cases, especially those involving airway compromise or vocal fold dysfunction, a multidisciplinary team approach—typically involving a spine surgeon and an otolaryngologist—is often beneficial to guide both diagnosis and treatment planning. Surgical intervention with osteophytectomy is primarily utilized either when medical treatment fails or when symptoms are severe such as airway compromise or severe dysphagia [3,5,11]. Post surgical outcomes are generally positive, with improvement of dysphagia or dysphonia and low recurrent symptoms [3,5,11].

An English language Embase search protocol was designed to find other cases of DISH-associated vocal cord paresis or immobilization. The following search term was used: (“vocal cord weak” OR “vocal cord paresis” OR “vocal cord paralysis” OR “vocal cord immobility” OR dysphonia OR hoarseness OR “laryngeal dysfunction” OR “vocal fold weak” OR “vocal fold paresis” OR “vocal fold paralysis” OR “vocal fold immobility” OR aphonia) AND (“Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis” OR DISH OR “Forestier Disease” OR hyperostosis). A total of 160 articles obtained from the initial Embase search were reviewed. Cases from reviewed articles were included if the patient (1) had a documented diagnosis of DISH and (2) had vocal cord immobilization or paresis as documented by laryngoscopy exam. The citations and citing articles of each included study were reviewed, as well as the citations of review articles identified in the primary search, to find additional sources. This method yielded twenty reported cases of DISH-associated vocal cord paresis or immobility with most cases showing immobility (n = 17), and many cases involving bilateral vocal folds (n = 12) (Table 1) [2,3,6,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. In all three cases with reported paresis, the contralateral vocal fold was already immobile [24].

Table 1.

Summary of notable features in included DISH cases.

Our first case aligns with existing literature on DISH, as the patient is a male in his eighth decade of life—consistent with the typical demographic profile of the condition. In contrast, DISH is exceedingly rare in individuals under 40 years of age, making our second case, involving a 30-year-old female, especially unusual; only a handful of such cases have been documented in the literature [25,26,27]. Notably, the younger patient had Turner syndrome, a chromosomal disorder not previously associated with DISH in the literature. While this may be coincidental, it raises the question of whether certain congenital or endocrine disorders predispose patients to earlier or atypical presentations. Further study may reveal underrecognized risk factors for early-onset DISH in populations beyond elderly males. What distinguishes both of our cases, however, is their presentation with unilateral vocal fold paresis—a finding not previously reported in the English-language literature. This underscores the novelty of our report and expands the known clinical spectrum of DISH-related laryngeal involvement. Our cases support broadening the diagnostic consideration of DISH beyond the typical elderly male demographic, possibly in younger patients with Turner syndrome or atypical laryngeal symptoms.

While other case reports have reported both unilateral and bilateral vocal fold immobility as well as bilateral paresis, but none have previously reported unilateral paresis [2,3,6,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. This finding supports the notion of a natural progression of the condition in which vocal fold mobility is affected in a stepwise manner. The disease first causes the vocal fold to become paretic, then paralyzed, with the possibility of progressing to the contralateral vocal cord. Given the rarity of DISH-related vocal fold paresis and its often subtle radiologic signs, clinicians should consider DISH in the differential diagnosis of unexplained dysphonia—particularly when standard workup is unrevealing. Awareness of this condition is important, especially because delayed treatment can lead to life-threatening airway compromise and required tracheotomy for airway protection [5]. Early recognition and treatment can prevent progression to complete immobility, permanent vocal fold dysfunction, and life-threatening complications.

4. Conclusions

We present the first known cases of DISH-associated unilateral vocal cord paresis. Our cases support expanding the diagnostic consideration of DISH beyond the typical elderly male demographic, possibly in younger patients with Turner syndrome or atypical laryngeal symptoms. Our findings expand the known clinical spectrum of DISH-related laryngeal involvement and suggest that vocal fold paresis may represent an early, previously underrecognized stage in the disease’s progression. Previous cases of DISH-related vocal fold paresis have only been reported in the setting of contralateral immobility, suggesting a progressive disease course. This underscores the importance of early recognition to enable timely intervention, limit clinical progression, and reduce the risk of airway compromise, aspiration, or irreversible vocal fold dysfunction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.K.; methodology, E.K., M.M. and R.K.; validation, E.K., M.M., H.B., W.H. and R.K.; formal analysis, E.K., M.M. and H.B.; investigation, E.K., M.M., H.B., W.H. and R.K.; data curation, E.K., M.M. and H.B.; writing—original draft preparation, E.K., M.M., H.B., W.H. and R.K.; writing—review and editing, E.K., M.M., H.B.,. W.H. and R.K.; supervision, R.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to not being required for a case report study of three or fewer cases.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DISH | Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| VHI | Voice Handicap Index |

References

- Resnick, D.; Niwayama, G. Radiographic and pathologic features of spinal involvement in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH). Radiology 1976, 119, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buyukkaya, R.; Buyukkaya, A.; Ozturk, B.; Ozşahin, M.; Erdoğmuş, B. Vocal cord paralysis and dysphagia caused by diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH): Clinical and radiographic findings. Turk. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 60, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebaaly, A.; Boubez, G.; Sunna, T.; Wang, Z.; Alam, E.; Christopoulos, A.; Shédid, D. Diffuse idiopathic hyperostosis manifesting as dysphagia and bilateral cord paralysis: A case report and literature review. World Neurosurg. 2018, 111, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schattner, A.; Dubin, I.; Glick, Y. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis-mediated dysphagia. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2022, 11, 55–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vengust, R.; Mihalič, R.; Turel, M. Two different causes of acute respiratory failure in a patient with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis and ankylosed cervical spine. Eur. Spine J. 2010, 19, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Goico-Alburquerque, A.; Zulfiqar, B.; Antoine, R.; Samee, M. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis: Persistent sore throat and dysphagia in an elderly smoker male. Case Rep. Med. 2017, 2017, 2567672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forestier, J.; Rotes-Querol, J. Senile ankylosing hyperostosis of the spine. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1950, 9, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffra, V.; Giusiani, S.; Fornaciari, A.; Villari, N.; Vitiello, A.; Fornaciari, G. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis in the Medici, Grand Dukes of Florence (XVI century). Eur. Spine J. 2010, 19, S103–S107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustina, A.; Mazziotti, G.; Canalis, E. Growth hormone, insulin-like growth factors, and the skeleton. Endocr. Rev. 2008, 29, 535–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, S.; Littlejohn, G. Metabolic factors in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis—A review of clinical data. Open Rheumatol. J. 2014, 8, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberale, C.; Bassani, S.; Nocini, R.; Molteni, G. Step-by-step surgery for diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) of the cervical spine. Laryngoscope 2023, 134, 2787–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, S.; Achar, T.S.; Badikkilaya, V.; Kanade, P.U. Forestier’s disease presenting as dysphagia and dysphonia—A rare case report. Glob. Spine J. 2023, 13, 215–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiue, Y.; Chang, T.S. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis presenting with hoarseness—A case report. Ear Nose Throat J. 2023, 104, 49S–50S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattisapu, P.; Donovan, D.T. Osteophyte causing direct compressive paralysis of recurrent laryngeal nerve. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2019, 161, 183–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, D.; Bukhari, S.; Ghobrial, I. A rare case of bilateral vocal cord palsy due to diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis. In Proceedings of the Hospital Medicine 2018, Orlando, FL, USA, 8–11 April 2018. Abstract #712. [Google Scholar]

- Virk, J.S.; Majithia, A.; Lingam, R.K.; Singh, A. Cervical osteophytes causing vocal fold paralysis: Case report and literature review. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2012, 126, 963–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, K.; Ulug, T.; Simsek, T. Bilateral vocal cord paralysis caused by cervical spinal osteophytes. Br. J. Radiol. 2002, 75, 990–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allensworth, J.J.; O’Dell, K.D.; Schindler, J.S. Bilateral vocal fold paralysis and dysphagia secondary to diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis. Head Neck 2017, 39, E1–E3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psychogios, G.; Jering, M.; Zenk, J. Cervical hyperostosis leading to dyspnea, aspiration and dysphagia: Strategies to improve patient management. Front. Surg. 2018, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkas, A.A.; Schmerber, S.A.; Gay, E.P.; Chahine, K.N.; Righini, C.A. Respiratory distress and vocal cord immobilization caused by Forestier’s disease. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2008, 139, 327–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstraete, W.L.; De Cauwer, H.G.; Verhulst, D.; Jacobs, F. Vocal cord immobilisation in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH). Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Belg. 1998, 52, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Young, D.; Saxby, K.; Beard, M.; Buniak, W.; Elnazepstein, D.; Davidhussain, K. Acute bilateral vocal cord paralysis (BVCP) in a patient with undiagnosed diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH). Chest 2021, 160, 890–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Singh, P.; Agrawa, G.; Kumar, S.; Banode, P. Arytenoid sclerosis in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis presenting with acute stridor in elderly: Chance or association? J. Laryngol. Voice 2016, 6, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razura, D.E.; Shuman, E.A.; Johns, M.M.; O’Dell, K. Bilateral vocal fold motion impairment associated with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis. OTO Open 2024, 8, 70003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.Z.; Chang, Z.Q.; Bao, Z.M. Young thoracic vertebra diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis with Scheuermann disease: A case report. World J. Clin. Cases 2023, 11, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoda, H.; Terai, H.; Yamada, K.; Suzuki, A.; Dohzono, S.; Matsumoto, T.; Nakamura, H. Prevalence of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis in patients with spinal disorders. Asian Spine J. 2017, 11, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiyama, A.; Katoh, H.; Sakai, D.; Sato, M.; Tanaka, M.; Watanabe, M. Prevalence of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) assessed with whole-spine computed tomography in 1479 subjects. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2018, 19, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).