Integrating Quality of Life Metrics into Head and Neck Cancer Treatment Planning: Evidence and Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Data Collection

- Age and sex;

- Tumor site and histology;

- Stage and presence of metastatic adenopathy;

- Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score;

- Final treatment modality (surgical vs. nonsurgical);

- Mortality status at last follow-up.

2.4. Quality of Life Assessment

- QLQ-C30: A 30-item core questionnaire evaluating global health status, functional domains (physical, role, emotional, cognitive, social), and symptoms (e.g., fatigue, pain).

- QLQ-H&N35: A site-specific module assessing head and neck-related symptoms including swallowing, speech, dry mouth, and social eating.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

- Mann–Whitney U test for two-group comparisons (e.g., sex, treatment type).

- Kruskal–Wallis test for multiple-group comparisons (e.g., tumor location).

- Spearman’s rank correlation for associations between continuous variables (age, CCI, QoL).

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

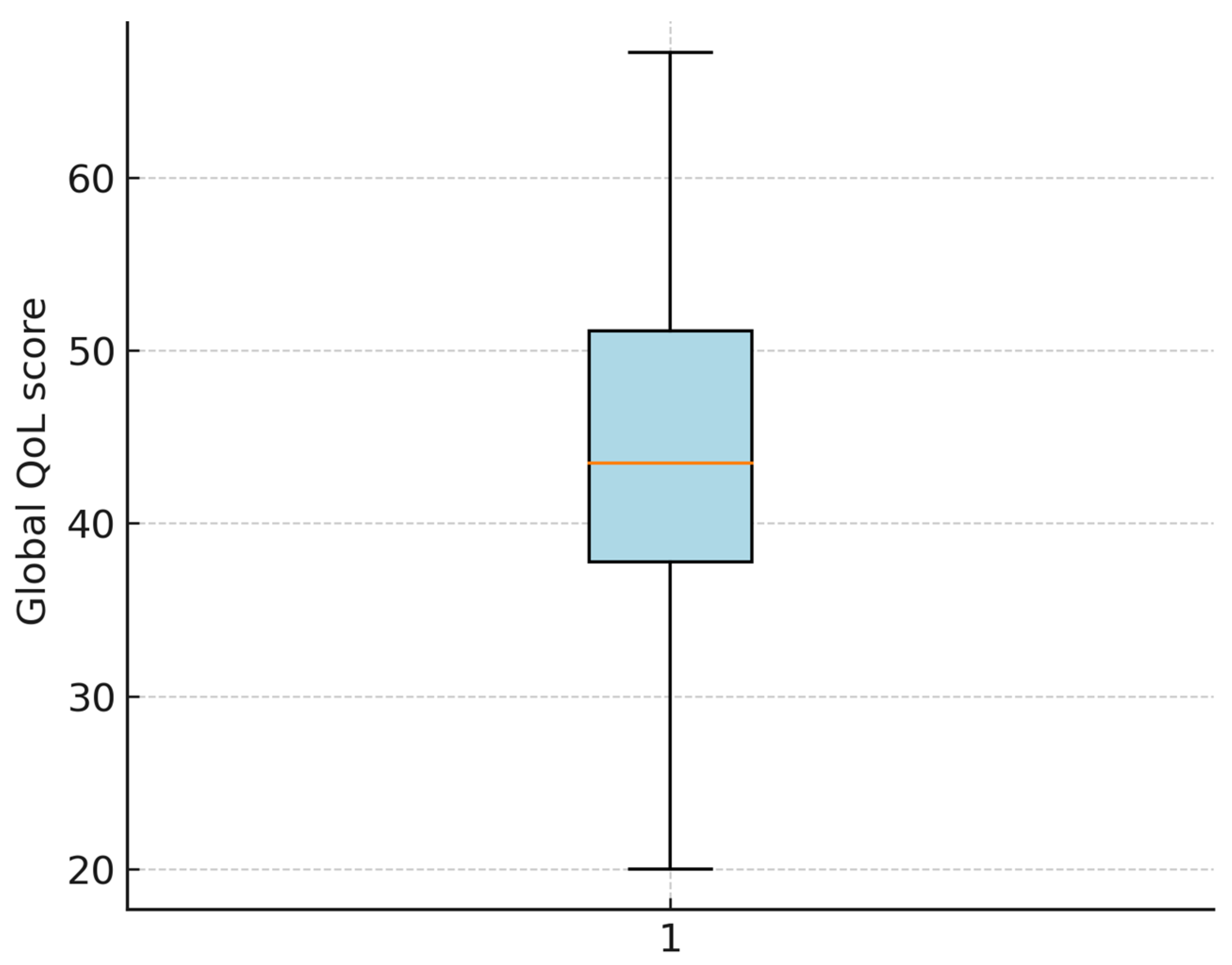

3.2. EORTC QoL Scores

3.3. Distribution and Normality Testing

3.4. Group Comparisons

3.4.1. Sex

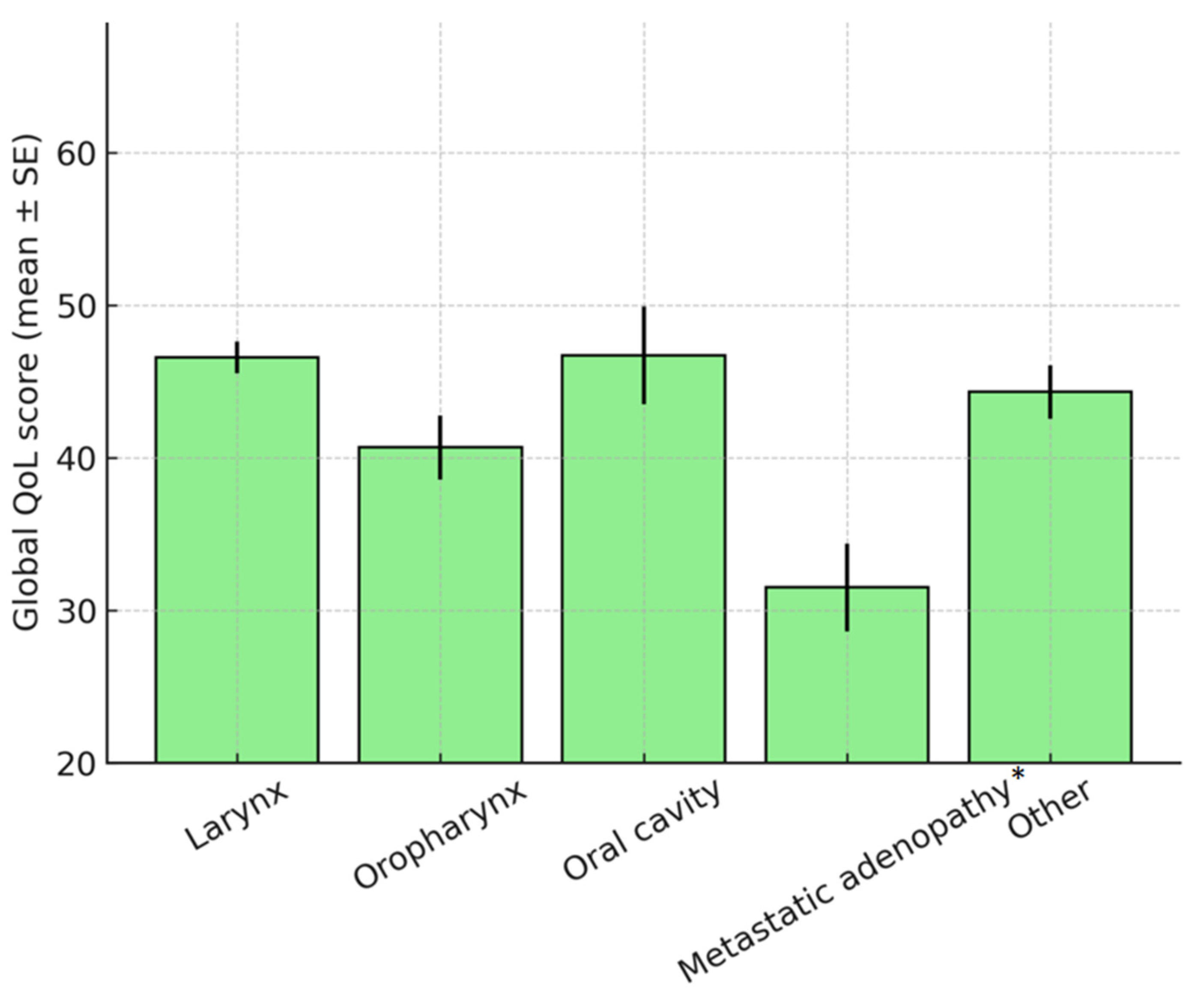

3.4.2. Tumor Location

3.4.3. Final Treatment

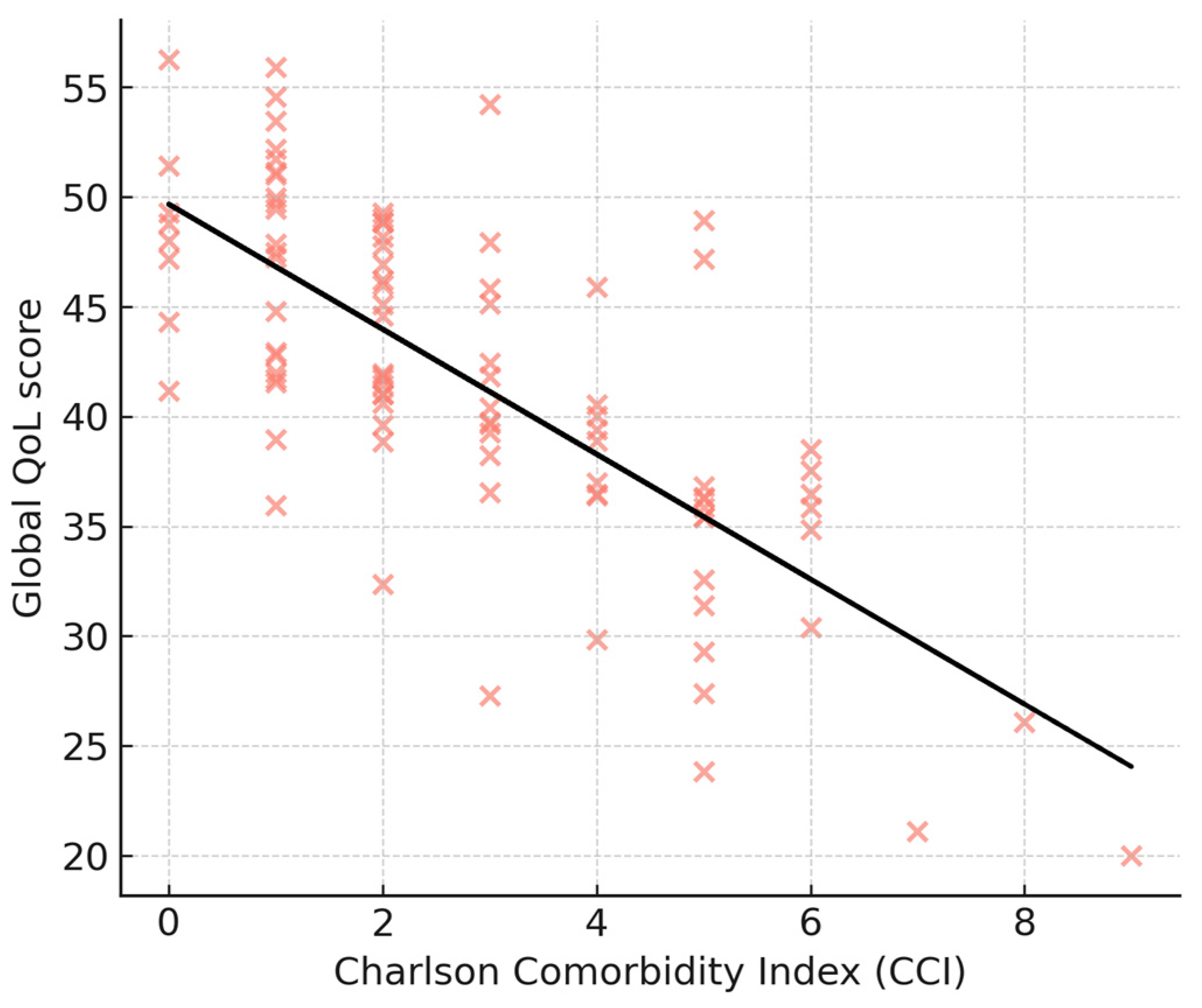

3.5. Correlation Analyses

3.6. Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Quality of Life in Head and Neck Cancer

4.2. Impact of Comorbidities

4.3. Role of Tumor Boards in QoL Outcomes

4.4. General Literature Findings and Broader Context

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| HNC/HNCs | Head and Neck Cancer(s) |

| EORTC | European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer |

| QLQ-C30 | Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 |

| QLQ-H&N35 | Quality of Life Questionnaire Head & Neck 35 |

| PF | Physical Functioning |

| RF | Role Functioning |

| EF | Emotional Functioning |

| CF | Cognitive Functioning |

| SF | Social Functioning |

| FA | Fatigue |

| PA | Pain |

| CCI | Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| η2 | Eta Squared (effect size measure) |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination (explained variance) |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| TORS | Transoral Robotic Surgery |

| ELPS | Endoscopic Laryngopharyngeal Surgery |

| ENT | Ear, Nose, and Throat |

| PROMs | Patient-Reported Outcome Measures |

References

- Licitra, L.; Mesia, R.; Keilholz, U. Individualised quality of life as a measure to guide treatment choices in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Oral Oncol. 2016, 52, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, J.P.; Gil, Z. Current concepts in management of oral cancer--surgery. Oral Oncol. 2009, 45, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheless, S.A.; McKinney, K.A.; Zanation, A.M. A prospective study of the clinical impact of a multidisciplinary head and neck tumor board. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2010, 143, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, S.N.; Lowe, D.; Brown, J.S.; Vaughan, E.D. Health-related quality of life after oral cancer treatment: 10-year outcomes. Head Neck 2019, 41, 2992–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, E.N.; Gomes, I.P.; Santos, J.N.; Souza, T.C.S.; Sá, C.D. Health-related quality of life in head and neck cancer patients: A longitudinal study. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 2163–2171. [Google Scholar]

- Strojan, P.; Hutcheson, K.A.; Eisbruch, A.; Beitler, J.J.; Langendijk, J.A.; Lee, A.W.M.; Corry, G.; Mendenhall, W.M.; Smee, R.; Rinaldo, A.; et al. Treatment of late sequelae after radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2017, 59, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wullaert, L.; Voigt, K.R.; Verhoef, C.; Husson, O.; Grünhagen, D.J. Oncological surgery follow-up and quality of life: Meta-analysis. Br. J. Surg. 2023, 110, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Rooij, J.A.F.; Roubos, J.; Vrancken Peeters, N.J.M.C.; Rijken, B.F.M.; Corten, E.M.L.; Mureau, M.A.M. Long-term patient-reported outcomes after reconstructive surgery for head and neck cancer: A systematic review. Head Neck 2023, 45, 2469–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mäkitie, A.A.; Alabi, R.O.; Pulkki-Råback, L.; Almangush, A.; Beitler, J.J.; Saba, N.F.; Strojan, P.; Takes, R.; Guntinas-Lichius, O.; Ferlito, A. Psychological factors related to treatment outcomes in head and neck cancer. Adv. Ther. 2024, 41, 3489–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendez, A.I.; Wihlidal, J.G.J.; Eurich, D.T.; Nichols, A.C.; MacNeil, S.D.; Seikaly, H.R. Validity of functional patient-reported outcomes in head and neck oncology: A systematic review. Oral Oncol. 2022, 125, 105701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, H.; Yang, C.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y. Early swallowing intervention after free flap reconstruction for oral cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck 2023, 45, 1430–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Virgilio, A.; Bellini, E.; Pace, G.M.; Costantino, A.; Festa, B.M.; Iandelli, A.; Russo, E.; Sampieri, C.; Peretti, G.; Spriano, G.; et al. Functional outcomes of soft palate reconstruction after oncologic surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2023, 280, 5177–5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, K.W.K.; Lai, R.; Lorincz, B.B.; Wang, C.C.; Chan, J.Y.K.; Yeung, D.C.M. Oncological and functional outcomes of transoral robotic surgery and endoscopic laryngopharyngeal surgery for hypopharyngeal cancer: A systematic review. Front. Surg. 2022, 8, 810581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, E.; Alessandri-Bonetti, M.; Costantino, A.; Festa, B.M.; Egro, F.M.; Giannitto, C.; Spriano, G.; De Virgilio, A. Functional outcomes and complications of total glossectomy with laryngeal preservation and flap reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2023, 141, 106415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, K.; Jones, S. Functional outcomes of early laryngeal cancer: Endoscopic laser surgery versus external beam radiotherapy—A systematic review. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2022, 136, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | N (%) or Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 82 (87.2) |

| Female | 12 (12.8) |

| Age (years) | 61.5 ± 9.8 (range 25–83) |

| Tumor location | |

| Larynx | 41 (43.6) |

| Oropharynx | 11 (11.7) |

| Hypopharynx/pharyngolaryngeal | 7 (7.4) |

| Oral cavity (pelvilingual/others) | 8 (8.5) |

| Metastatic adenopathy (unknown primary) | 6 (6.4) |

| Other sites (nasal cavity, parotid, skin, etc.) | 21 (22.4) |

| Treatment type | |

| Surgical | 70 (74.5) |

| Nonsurgical | 24 (25.5) |

| Tumor board recommendation | Surgery in 87 (92.6) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) | Median 3 (IQR 2–5) |

| Mortality at follow-up | 9 (9.6) |

| Tumor Location and Specific Intervention | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Larynx | 36 | (51.43%) |

| Total Laryngectomy | 26 | |

| Partial Laser Laryngectomy | 3 | |

| Classic Partial Laryngectomy | 2 | |

| TOUSS Partial Laryngectomy | 1 | |

| Laser Cordectomy | 3 | |

| Tracheostomy (RT) | 1 | |

| 2. Pharynx/Pharyngolaryngeal | 10 | (14.29%) |

| Partial Pharyngectomy | 5 | |

| Total Pharyngolaryngectomy | 3 | |

| Total Glossectomy with Total Laryngectomy | 1 | |

| Biopsy (no surgical intervention) | 1 | |

| 3. Oropharynx/Lingual/Pelvilingual | 16 | (22.86%) |

| Bucopharyngectomy | 7 | |

| Transmandibular Glossopelvectomy | 2 | |

| Transoral Glossopelvectomy | 3 | |

| Hemiglossopelvectomy | 1 | |

| Partial Glossectomy | 1 | |

| Right Hemiglossectomy, Bucopharyngectomy | 1 | |

| Glossopelvectomy | 1 | |

| 4. Rhinosinusal/Auditory Canal | 2 | (2.86%) |

| Bilateral Frontal Sinusotomy | 1 | |

| Tumor Mass Ablation (Auditory Canal) | 1 | |

| 5. Adenopathy of unknown primary/Other | 6 | (8.57%) |

| Lymph Node Dissection | 5 | |

| Tumor Debulking (Inoperable Case) | 1 | |

| Overall Total | 70 | |

| Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|

| Surgery | 5 | 5% |

| Surgery + RT | 31 | 33% |

| Surgery + CHRT | 34 | 36% |

| Nonsurgical | 24 | 26% |

| Total | 94 | 100% |

| Reasons for Non Surgical Treatment | Date of Tumor Board Assesment | Date of Follow-up | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidites | 1 | 2 | |

| Stage | 4 | 3 | |

| Personal decision | 1 | 4 | |

| Exitus | 1 | 8 | |

| Total | 7 | 17 | 24 |

| Tumor Location (Recoded) | Mean Comorbidity Count | Mean Index Charlson |

|---|---|---|

| Larynx | 2.97 | 3.87 |

| Pharynx/Pharyngolaryngeal | 4.67 | 4.70 |

| Oropharynx/Lingual/Pelvilingual | 2.38 | 2.80 |

| Rhinosinusal/Auditory Canal | 2.00 | 1.00 |

| Adenopathy/Other | 3.50 | 4.33 |

| Domain | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Global health status/QoL (QL) | 42.3 ± 11.7 |

| Physical functioning (PF) | 63.1 ± 15.1 |

| Role functioning (RF) | 55.2 ± 14.9 |

| Emotional functioning (EF) | 59.3 ± 16.7 |

| Cognitive functioning (CF) | 65.7 ± 13.8 |

| Social functioning (SF) | 58.4 ± 15.2 |

| Fatigue (FA) | 61.5 ± 13.5 |

| Pain (PA) | 57.6 ± 12.9 |

| Swallowing difficulties | 75.4 ± 11.3 |

| Speech problems | 69.2 ± 13.2 |

| Dry mouth | 71.5 ± 12.8 |

| Painkiller use | 74.6 ± 14.3 |

| Variable | β (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.12 (−0.28 to 0.04) | 0.14 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | −1.9 (−6.5 to 2.8) | 0.42 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | −2.5 (−4.6 to −0.4) | 0.02 * |

| Tumor type: metastatic adenopathy of unknown primary | −8.0 (−15.2 to −0.9) | 0.04 * |

| Other tumor sites (ref = larynx) | −3.1 (−7.8 to 1.6) | 0.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bejenaru, P.L.; Berteșteanu, G.S.; Grigore, R.; Nedelcu-Stancalie, R.I.; Schipor-Diaconu, T.E.; Rujan, S.A.; Taher, B.P.; Popescu, B.; Popescu, I.D.; Nicolaescu, A.; et al. Integrating Quality of Life Metrics into Head and Neck Cancer Treatment Planning: Evidence and Implications. J. Otorhinolaryngol. Hear. Balance Med. 2025, 6, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ohbm6020019

Bejenaru PL, Berteșteanu GS, Grigore R, Nedelcu-Stancalie RI, Schipor-Diaconu TE, Rujan SA, Taher BP, Popescu B, Popescu ID, Nicolaescu A, et al. Integrating Quality of Life Metrics into Head and Neck Cancer Treatment Planning: Evidence and Implications. Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, Hearing and Balance Medicine. 2025; 6(2):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ohbm6020019

Chicago/Turabian StyleBejenaru, Paula Luiza, Gloria Simona Berteșteanu, Raluca Grigore, Ruxandra Ioana Nedelcu-Stancalie, Teodora Elena Schipor-Diaconu, Simona Andreea Rujan, Bianca Petra Taher, Bogdan Popescu, Irina Doinița Popescu, Alexandru Nicolaescu, and et al. 2025. "Integrating Quality of Life Metrics into Head and Neck Cancer Treatment Planning: Evidence and Implications" Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, Hearing and Balance Medicine 6, no. 2: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ohbm6020019

APA StyleBejenaru, P. L., Berteșteanu, G. S., Grigore, R., Nedelcu-Stancalie, R. I., Schipor-Diaconu, T. E., Rujan, S. A., Taher, B. P., Popescu, B., Popescu, I. D., Nicolaescu, A., Cîrstea, A. I., Simion-Antonie, C. B., & Berteșteanu, Ș. G. V. (2025). Integrating Quality of Life Metrics into Head and Neck Cancer Treatment Planning: Evidence and Implications. Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, Hearing and Balance Medicine, 6(2), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ohbm6020019