A Bidirectional Digital Twin System for Adaptive Manufacturing

Abstract

1. Introduction

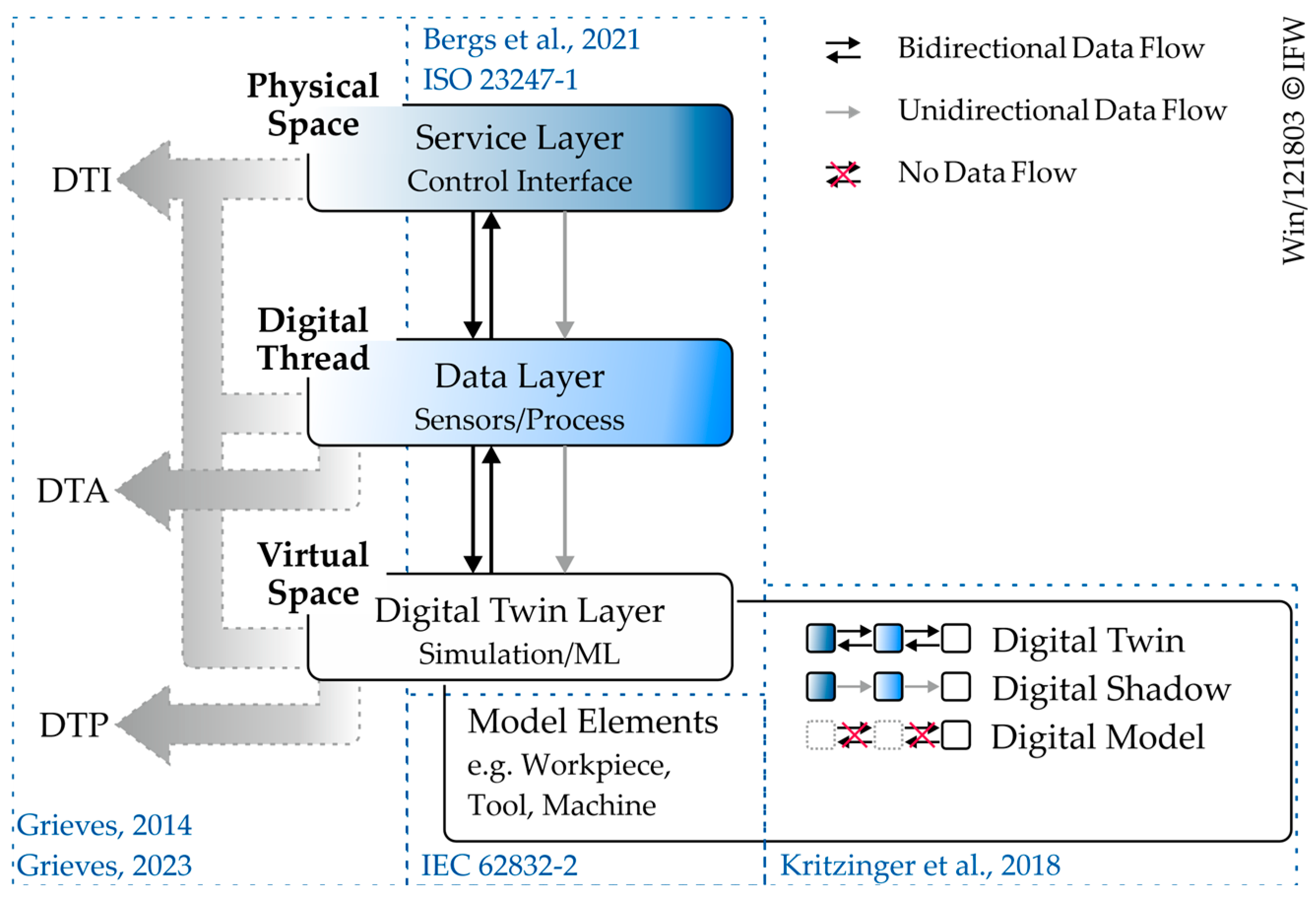

1.1. Digital Twin Systems in Manufacturing

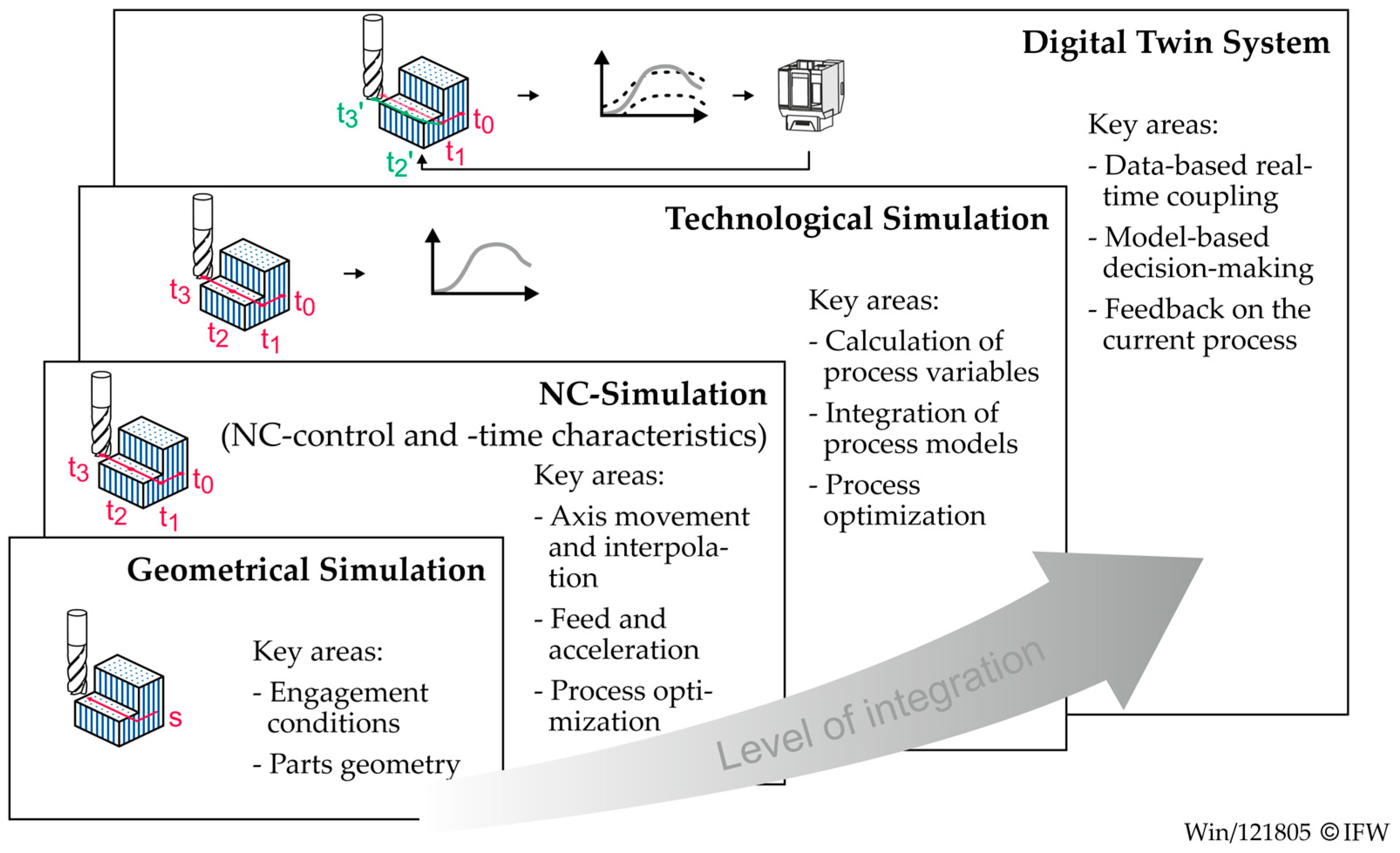

1.2. Process Simulation

- Realizing a complete DTS with a bidirectional data flow for closed-loop integration of real and virtual machining states, and

- Validating the system’s capability for process-parallel monitoring and intervention through representative use cases in orthopedic implant manufacturing.

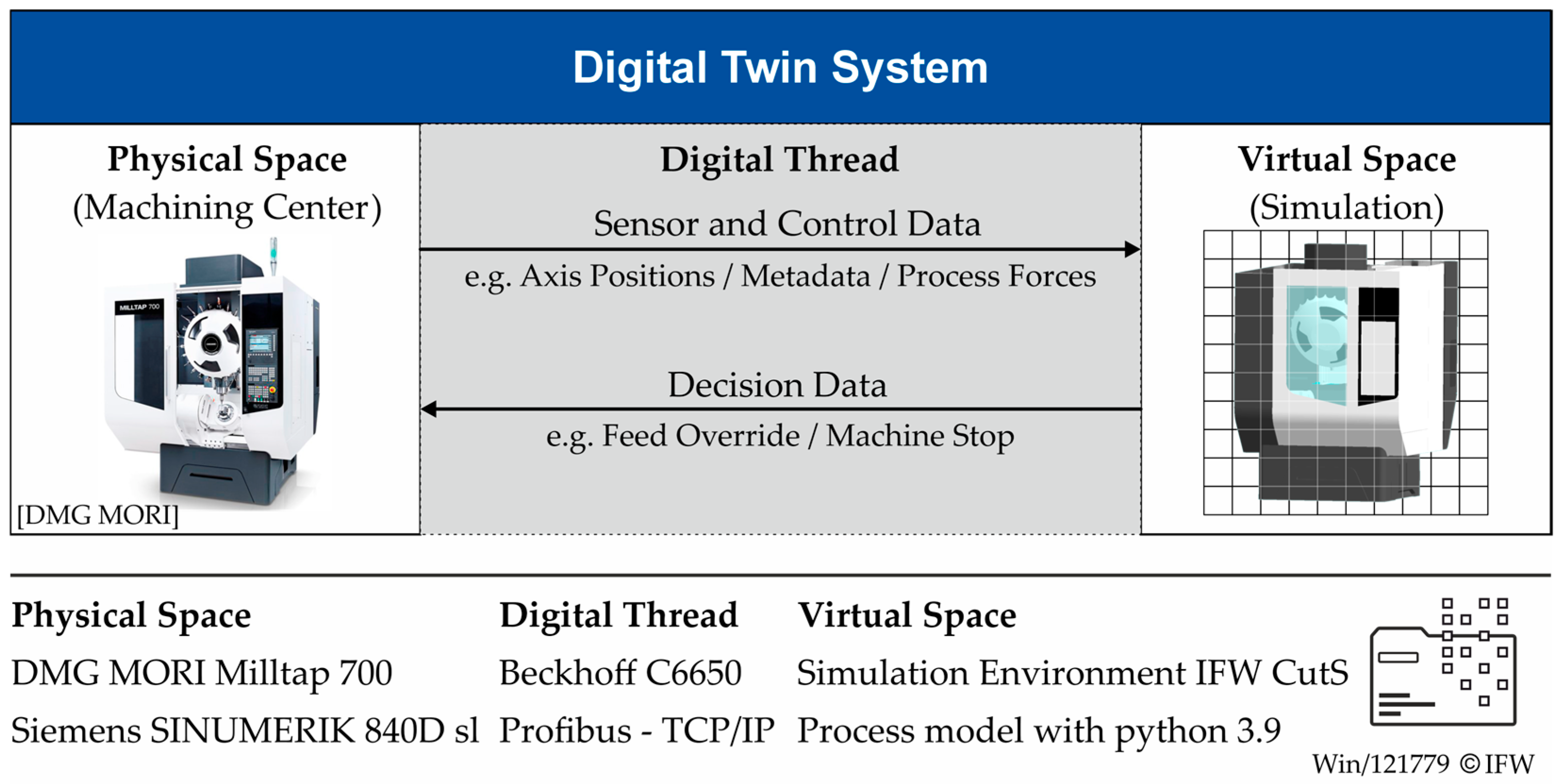

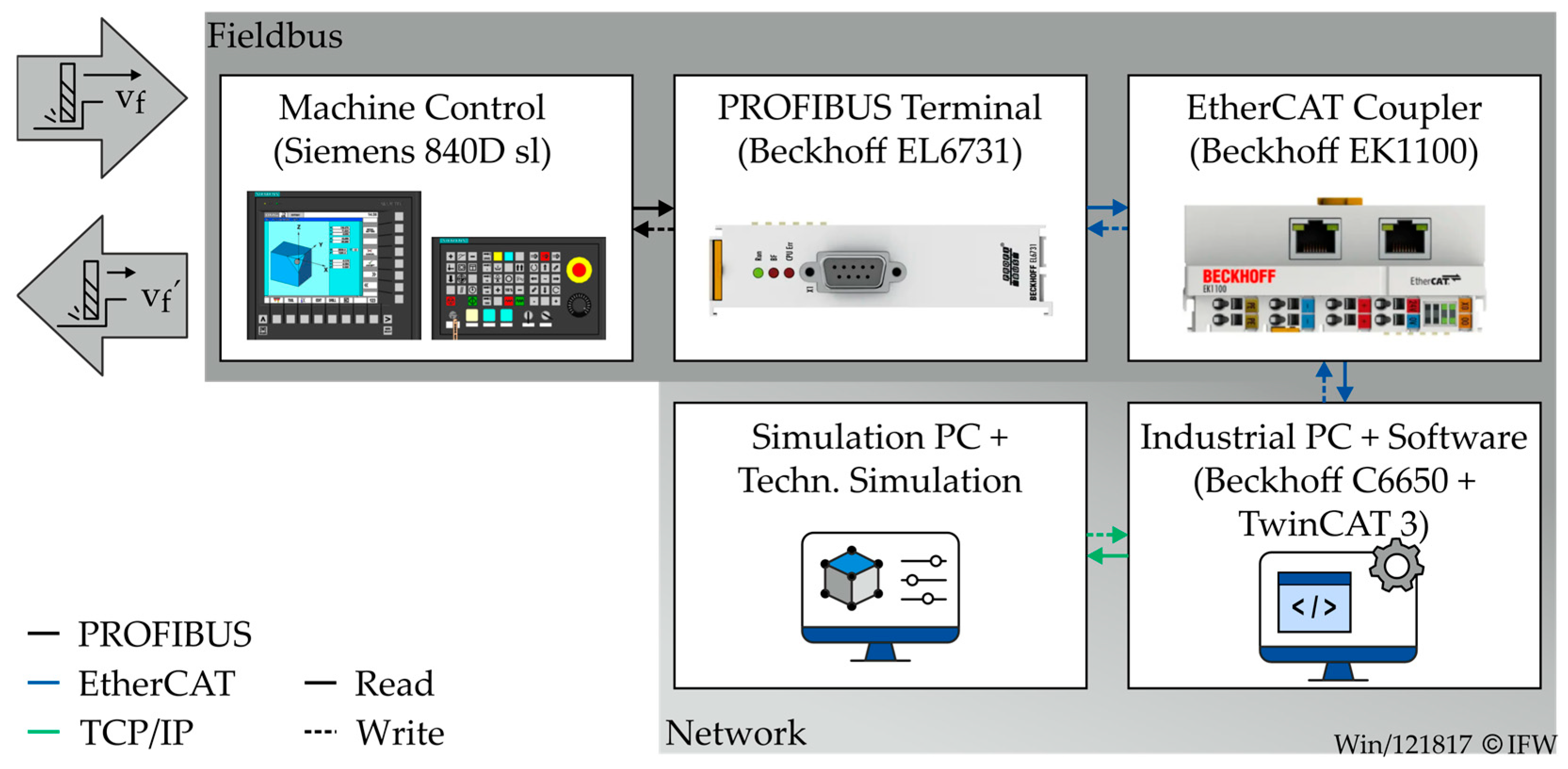

2. Architecture of the Digital Twin System

- Real-time coupling between machine and simulation at the controller level;

- Utilization of machine-native signals for scalable process diagnostics;

- Integration of explainable, domain-specific predictive models;

- Feedback of condition evaluations into process control or user interface.

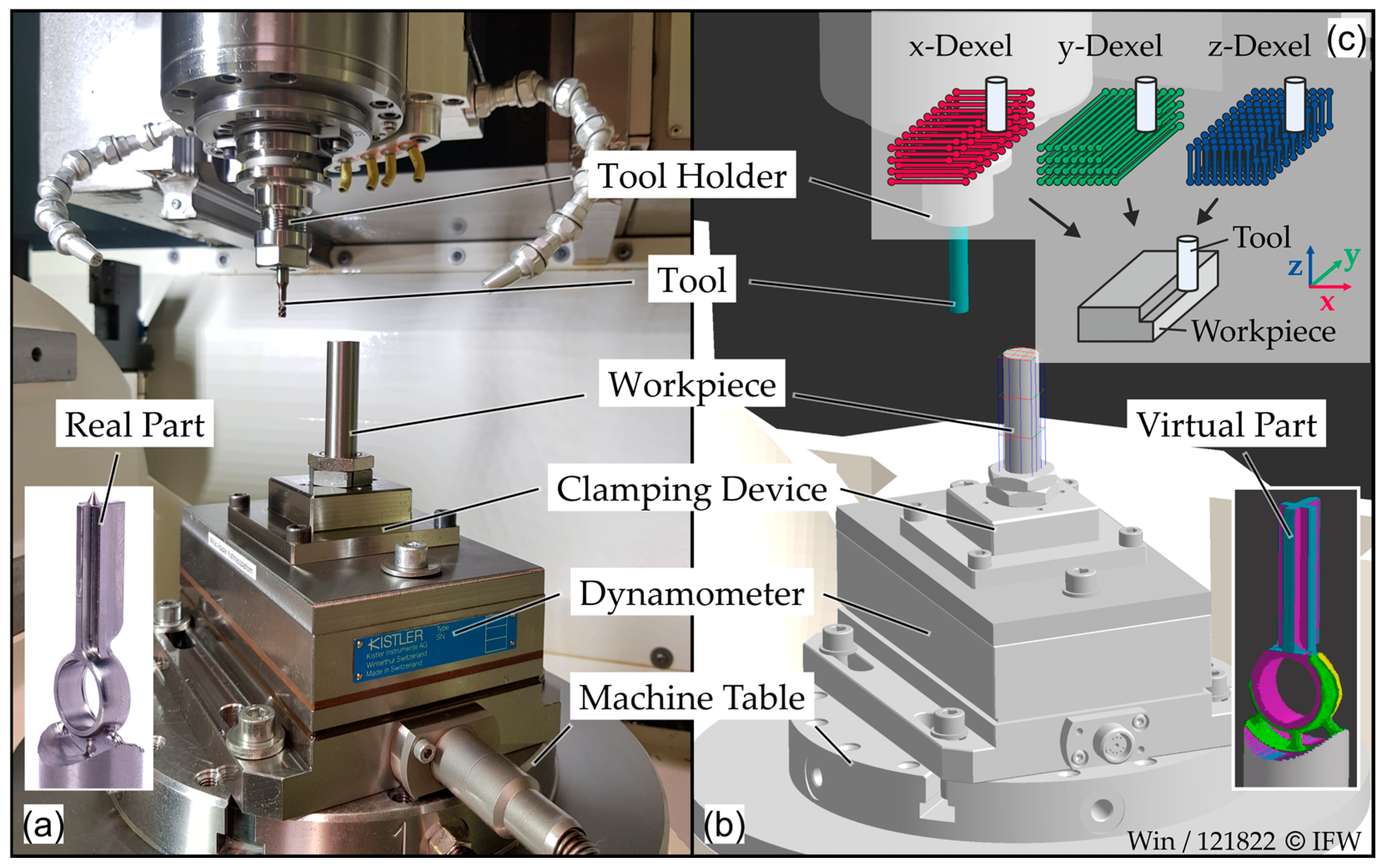

2.1. Physical Space

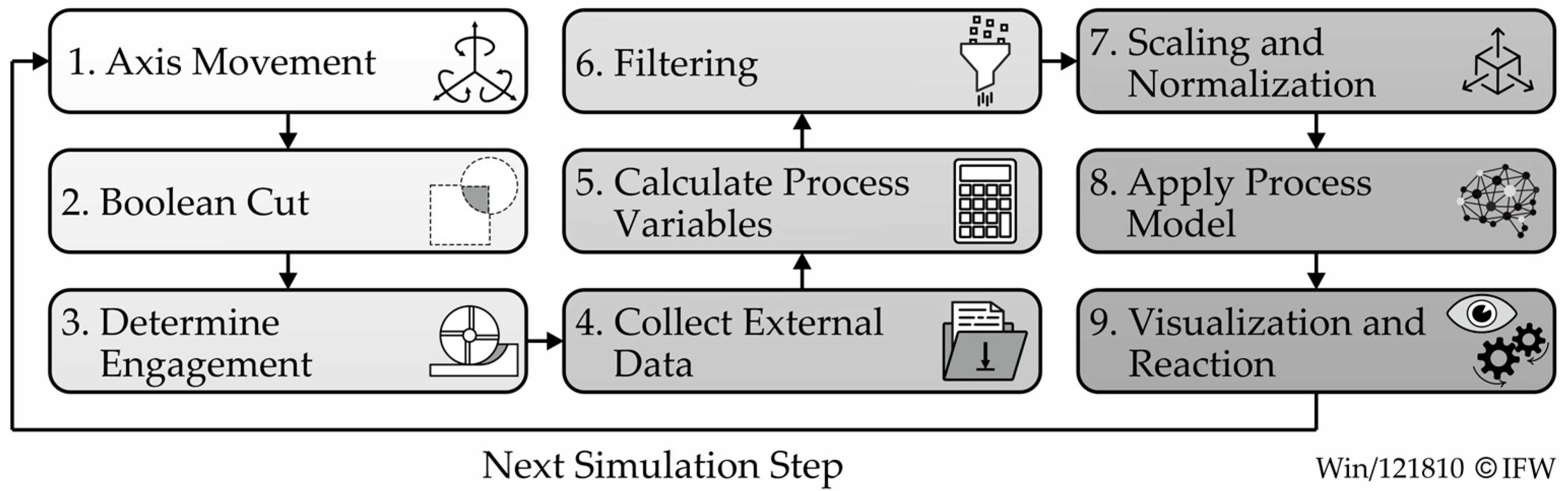

2.2. Virtual Space

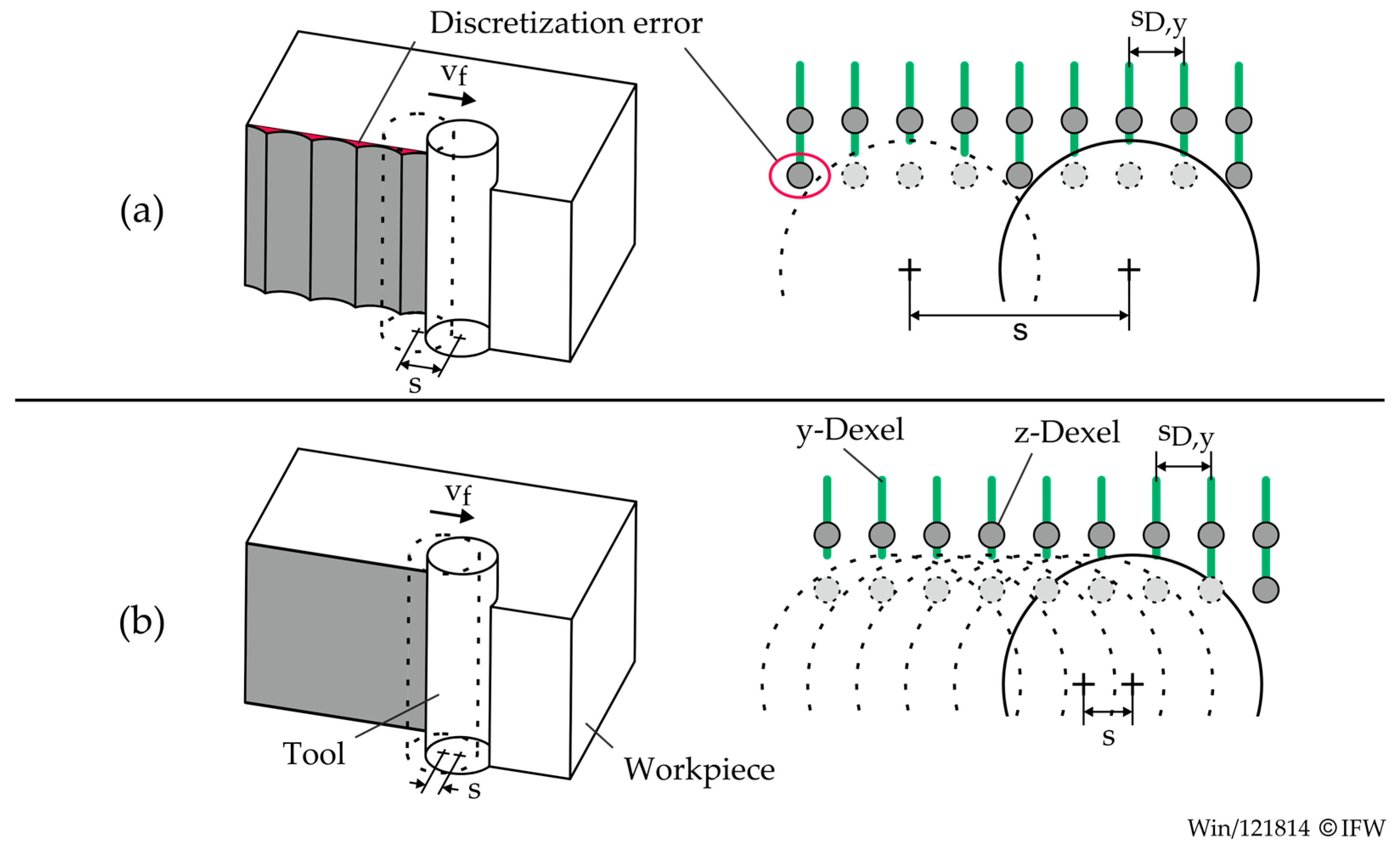

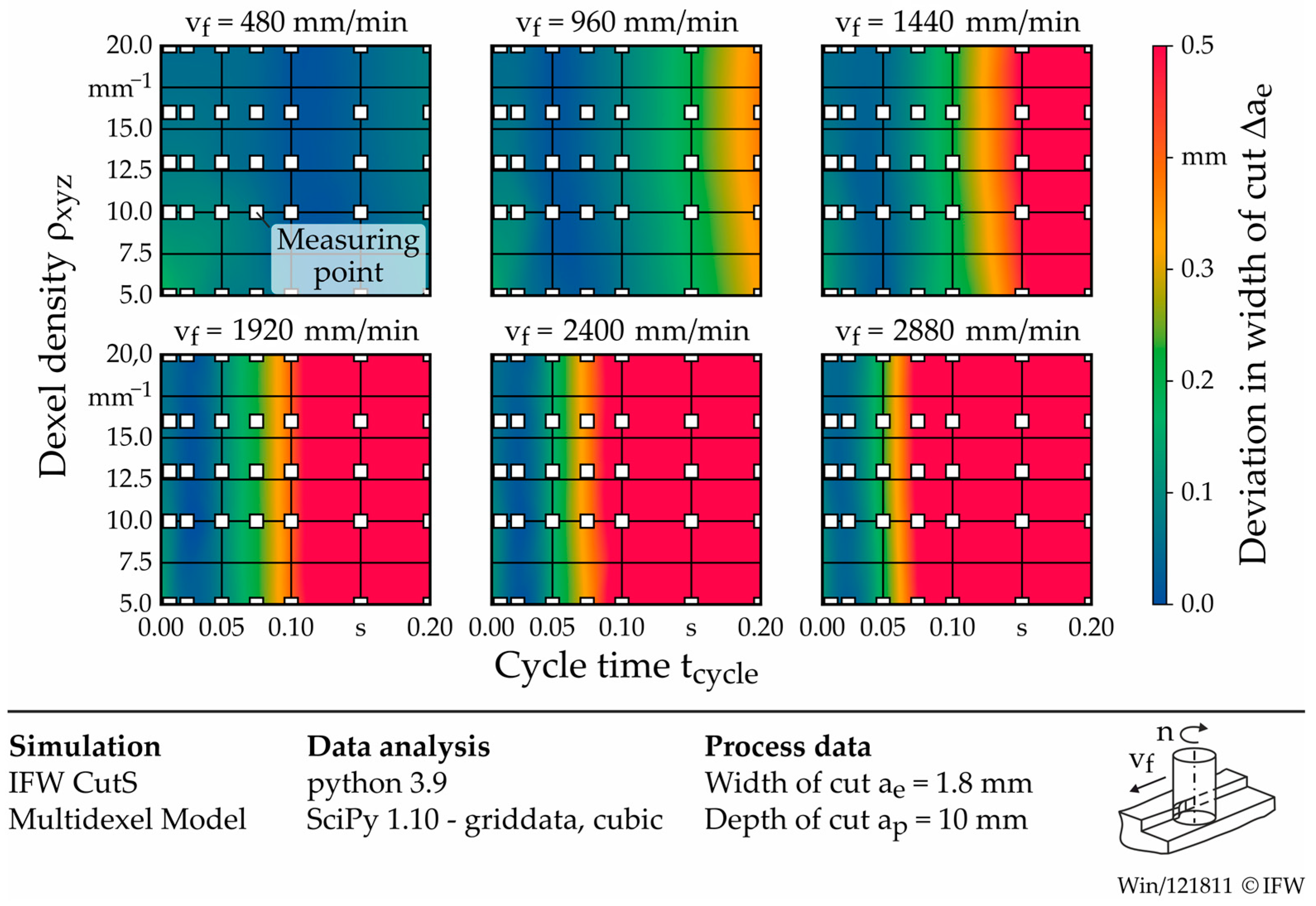

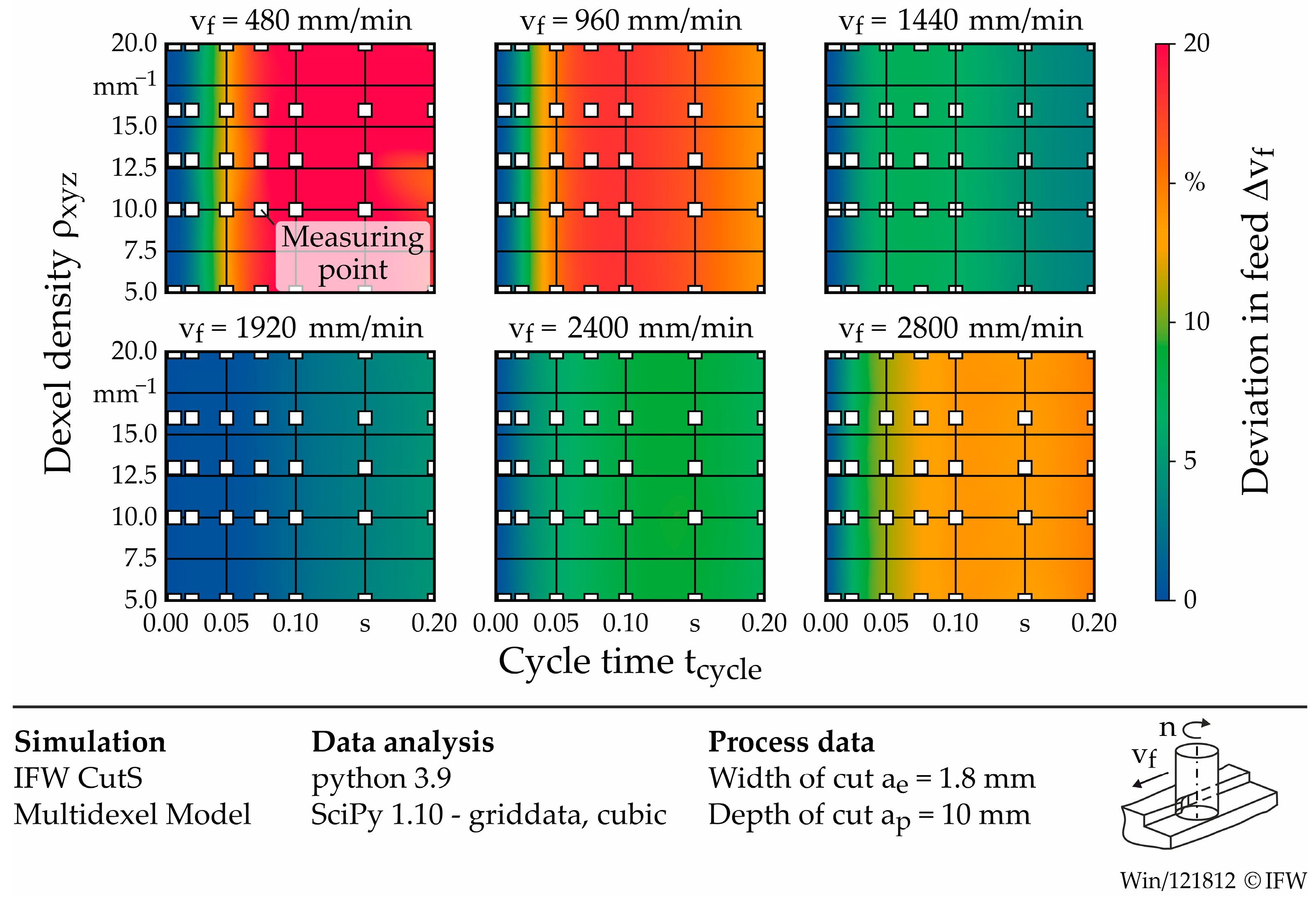

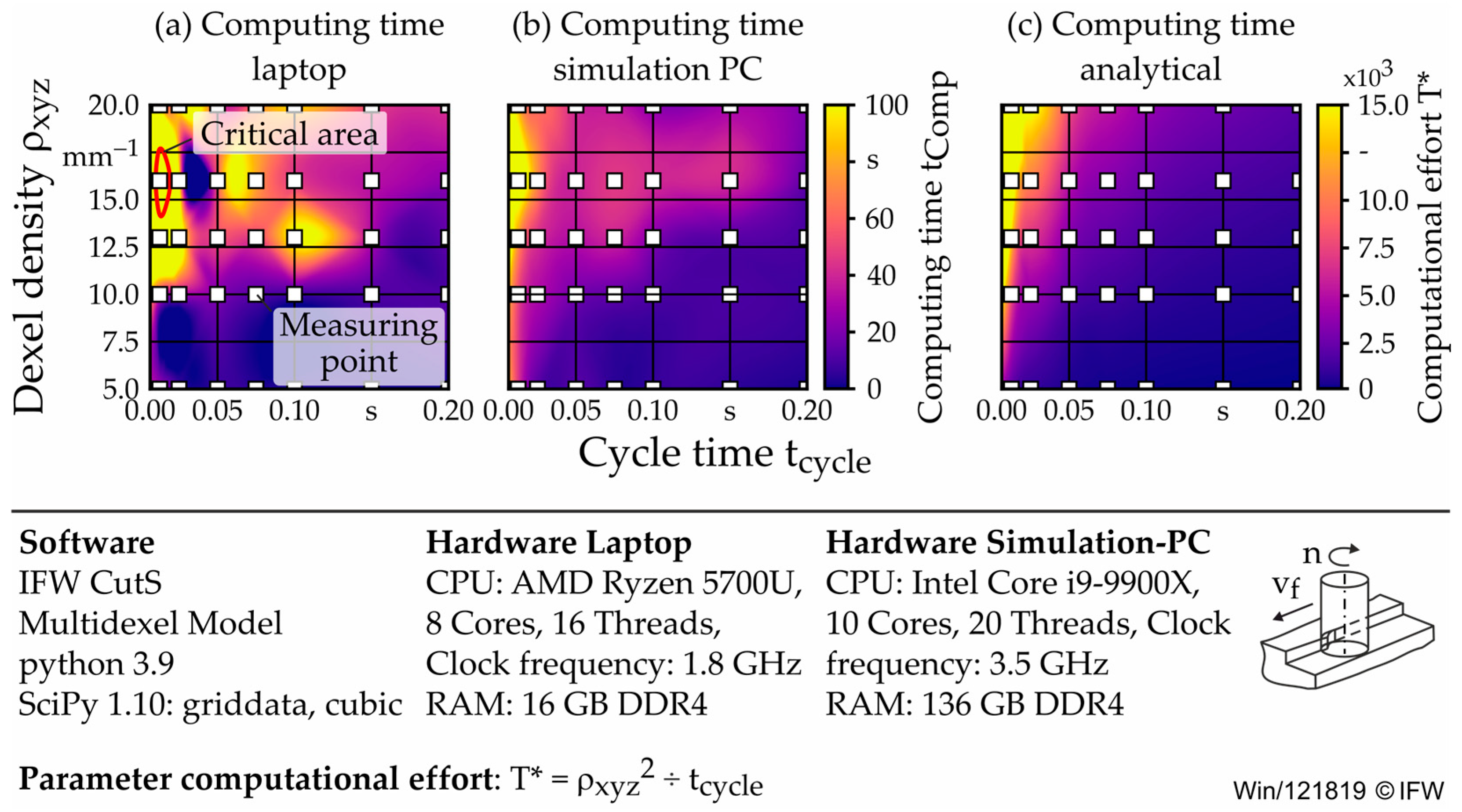

2.3. Simulation Study: Influence of Parameters on Model Accuracy and Runtime

- Mean deviation of simulated width of cut (Aae);

- Relative error in simulated feed rate (Avf);

- Total simulation runtime (AT).

2.4. Digital Thread

2.5. Communication Latency Analysis

3. Application Scenarios for Process Monitoring and Control Using the Digital Twin System

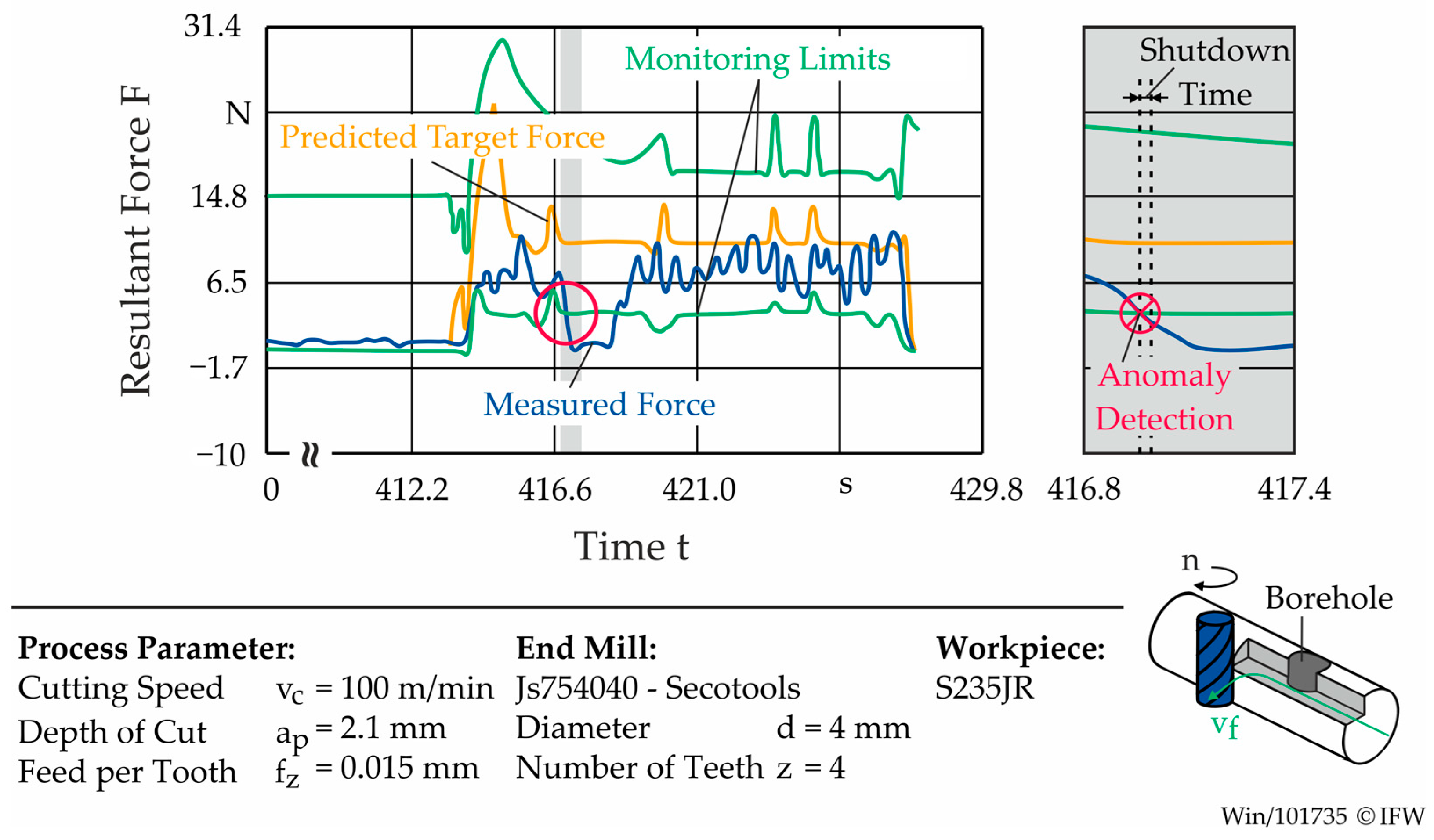

3.1. Use Case 1: Process Force Monitoring and Machine Halt

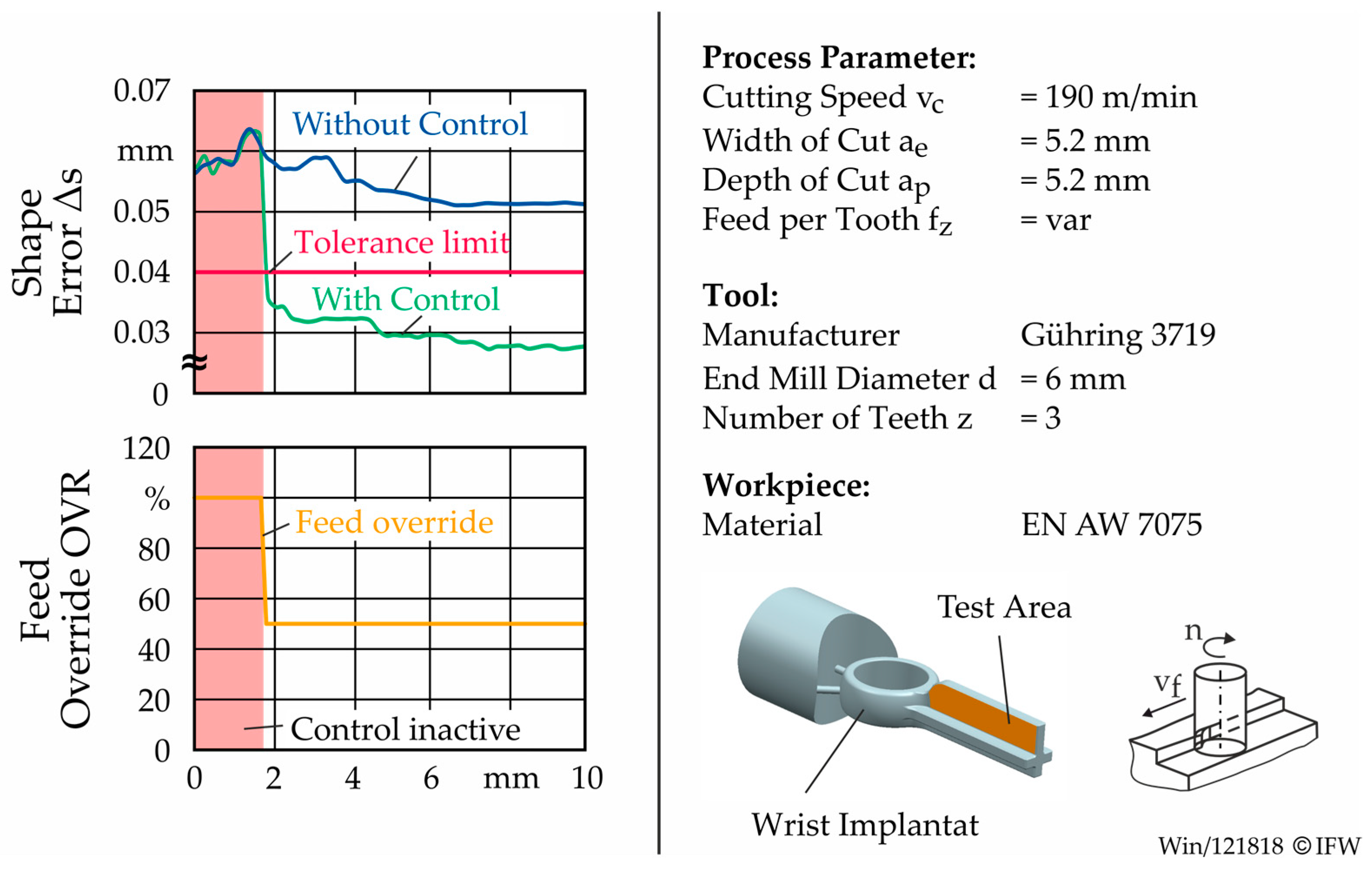

3.2. Use Case 2: Shape Error Control and Feed Rate Adjustment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADS | Automation Device Specification |

| C# | C Sharp (programming language) |

| CNC | Computerized Numerical Control |

| DT | Digital Twin |

| DTA | Digital Twin Aggregate |

| DTI | Digital Twin Instance |

| DTP | Digital Twin Prototype |

| DTS | Digital Twin System |

| EtherCAT | Ethernet for Control Automation Technology |

| IPC | Industrial PC |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NC | Numerical Control |

| ONNX | Open Neural Network Exchange |

| PC | Personal Computer |

| PROFIBUS | Process Field Bus |

References

- Europäische Union. Verordnung (EU) 2017/745 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates: MDR; Europäische Union: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH. Whitepaper 2025: Aktuelles zu MDR, AI Act und Cybersecurity; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- International Medical Device Regulators Forum. Unique Device Identification System (UDI System) Application Guide: IMDRF/UDI WG/N48 FINAL:2019; International Medical Device Regulators Forum: Sapporo, Japan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bergs, T.; Biermann, D.; Erkorkmaz, K.; M’Saoubi, R. Digital twins for cutting processes. CIRP Ann. 2023, 72, 541–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellenbrink, C.; Nübel, N.; Schnabel, A.; Gilge, P.; Seume, J.R.; Denkena, B.; Helber, S. A regeneration process chain with an integrated decision support system for individual regeneration processes based on a virtual twin. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 4137–4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergs, T.; Gierlings, S.; Auerbach, T.; Klink, A.; Schraknepper, D.; Augspurger, T. The Concept of Digital Twin and Digital Shadow in Manufacturing. Procedia CIRP 2021, 101, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleich, B.; Dittrich, M.-A.; Clausmeyer, T.; Damgrave, R.; Erkoyuncu, J.A.; Haefner, B.; de Lange, J.; Plakhotnik, D.; Scheidel, W.; Wuest, T. Shifting value stream patterns along the product lifecycle with digital twins. Procedia CIRP 2019, 86, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M.W. Digital Twins: Past, Present, and Future. In The Digital Twin; Crespi, N., Drobot, A.T., Minerva, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 97–121. ISBN 978-3-031-21342-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kritzinger, W.; Karner, M.; Traar, G.; Henjes, J.; Sihn, W. Digital Twin in manufacturing: A categorical literature review and classification. IFAC-Pap. 2018, 51, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M.; Vickers, J. Digital Twin: Mitigating Unpredictable, Undesirable Emergent Behavior in Complex Systems. In Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems; Kahlen, F.-J., Flumerfelt, S., Alves, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 85–113. ISBN 978-3-319-38754-3. [Google Scholar]

- Grieves, M. Digital Twin: Manufacturing Excellence through Virtual Factory Replication. 2014. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275211047 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Zhuang, C. Digital Twin Modeling Enabled Machine Tool Intelligence: A Review. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2024, 37, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Electrotechnical Commission. Industrial-Process Measurement, Control and Automation—Digital Factory Framework: Part 2: Model Elements, 2020 ed.; International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 23247-1:2021(en); Digital Twin Framework for Manufacturing—Part 1: Overview and General Principles. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Stark, R.; Fresemann, C.; Lindow, K. Development and operation of Digital Twins for technical systems and services. CIRP Ann. 2019, 68, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleich, B.; Anwer, N.; Mathieu, L.; Wartzack, S. Shaping the digital twin for design and production engineering. CIRP Ann. 2017, 66, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Electrotechnical Commission. Industrial-Process Measurement, Control and Automation—Digital Factory Framework: Part 1: General Principles, 2020 ed.; International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlemann, T.H.-J.; Lehmann, C.; Steinhilper, R. The Digital Twin: Realizing the Cyber-Physical Production System for Industry 4.0. Procedia CIRP 2017, 61, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, L.R.R.; Pimenov, D.Y.; Da Silva, R.B.; Ercetin, A.; Giasin, K. Review of Applications of Digital Twins and Industry 4.0 for Machining. JMMP 2025, 9, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Li, S.; Song, H.; Lu, Y. Digital Twin-driven multi-scale characterization of machining quality: Current status, challenges, and future perspectives. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2025, 93, 102902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Tao, F. Digital Twin and Big Data Towards Smart Manufacturing and Industry 4.0: 360 Degree Comparison. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 3585–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkena, B.; Wichmann, M.; Reuter, L.; Schlenker, F. Realizing Digital Twins in the Aircraft Industry by Using Simulation-Based Soft Sensors. MIC Procedia 2022, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, H.; Shao, G.; Starly, B. A Case Study of Digital Twin for Manufacturing Process Involving Human Interactions. In Proceedings of the 2020 Winter Simulation Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 13–16 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, R.; Sun, C.; Dominguez-Caballero, J.; Ojo, S.; Ayvar-Soberanis, S.; Curtis, D.; Ozturk, E. Machining Digital Twin using real-time model-based simulations and lookahead function for closed loop machining control. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 117, 3615–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yue, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Liang, S.Y.; Xia, W.; Dou, X. Research on digital twin monitoring system during milling of large parts. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 77, 834–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Huang, H.; Mei, L. A method for constructing digital twins of CNC machine tools feed systems based on hybrid mechanism-data. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dittrich, M.-A. Autonome Werkzeugmaschinen: Definition, Elemente und Technische Integration; TEWISS Verlag: Garbsen, Germany, 2021; ISBN 9783959005920. [Google Scholar]

- Verein Deutscher Ingenieure. Digitale Fabrik: Digitaler Fabrikbetrieb; VDI-Gesellschaft Produktion und Logistik: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2011; VDI 4499 Blatt 2. [Google Scholar]

- Rehling, S. Technologische Erweiterung der Simulation von NC-Fertigungsprozessen; Zugl.: Hannover, Univ., Diss., 2008; PZH Produktionstechnisches Zentrum: Garbsen, Germany, 2009; ISBN 9783941416086. [Google Scholar]

- Stautner, M. Simulation und Optimierung der Mehrachsigen Fräsbearbeitung; Vulkan-Verlag: Essen, Germany, 2006; ISBN 3802787323. [Google Scholar]

- Denkena, B.; Böß, V. Technological NC Simulation for Grinding and Cutting Processes Using CutS. In Proceedings of the 12th CIRP Conference on Modelling of Machining Operations, Donostia-San Sebastián, Spain, 7–8 May 2009; Arrazola, P.J., Ed.; Mondragon Unibertsitateko Zerbitzu Ed: Mondragon, Spain, 2009; pp. 563–566, ISBN 9788460808640. [Google Scholar]

- Altintas, Y.; Kersting, P.; Biermann, D.; Budak, E.; Denkena, B.; Lazoglu, I. Virtual process systems for part machining operations. CIRP Ann. 2014, 63, 585–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederwestberg, D. Prognose und Kompensation der Temperaturbedingten Werkstückverlagerungen beim Trockenfräsen; Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Universität Hannover: Hannover, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Arrazola, P.J.; Özel, T.; Umbrello, D.; Davies, M.; Jawahir, I.S. Recent advances in modelling of metal machining processes. CIRP Ann. 2013, 62, 695–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohannes, B. Industrielle Prozessüberwachung für die Kleinserienfertigung; PZH-Verlag: Garbsen, Germany, 2013; ISBN 9783944586137. [Google Scholar]

- Denkena, B. Cyber-Physical and Gentelligent Systems in Manufacturing and Life Cycle: Genetics and Intelligence–Keys to Industry 4.0; Elsevier Science: Saint Louis, MO, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-12-811939-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pape, O.; Denkena, B. Entwicklung von Fräswerkzeugen Durch Geometrische Simulationen; Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Universität Hannover: Hannover, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Böß, V.; Denkena, B.; Breidenstein, B.; Dittrich, M.-A.; Nguyen, H.N. Improving technological machining simulation by tailored workpiece models and kinematics. Procedia CIRP 2019, 82, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bate, I.; McDermid, J.; Nightingale, P. Establishing timing requirements for control loops in real-time systems. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2003, 27, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkena, B.; Winkler, M. Teilautonome Fertigung orthopädischer Implantate: TempoPlant, teilautonome Fertigungszelle für orthopädische Implantate: Abschlussbericht zum BMBF-Verbundprojekt; TEWISS Verlag: Garbsen, Germany, 2024; ISBN 9783959009157. [Google Scholar]

- Stiehl, T.H. Transfer von Wissen zwischen Werkzeugmaschinen für die Prozessüberwachung; Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Universität Hannover: Hannover, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

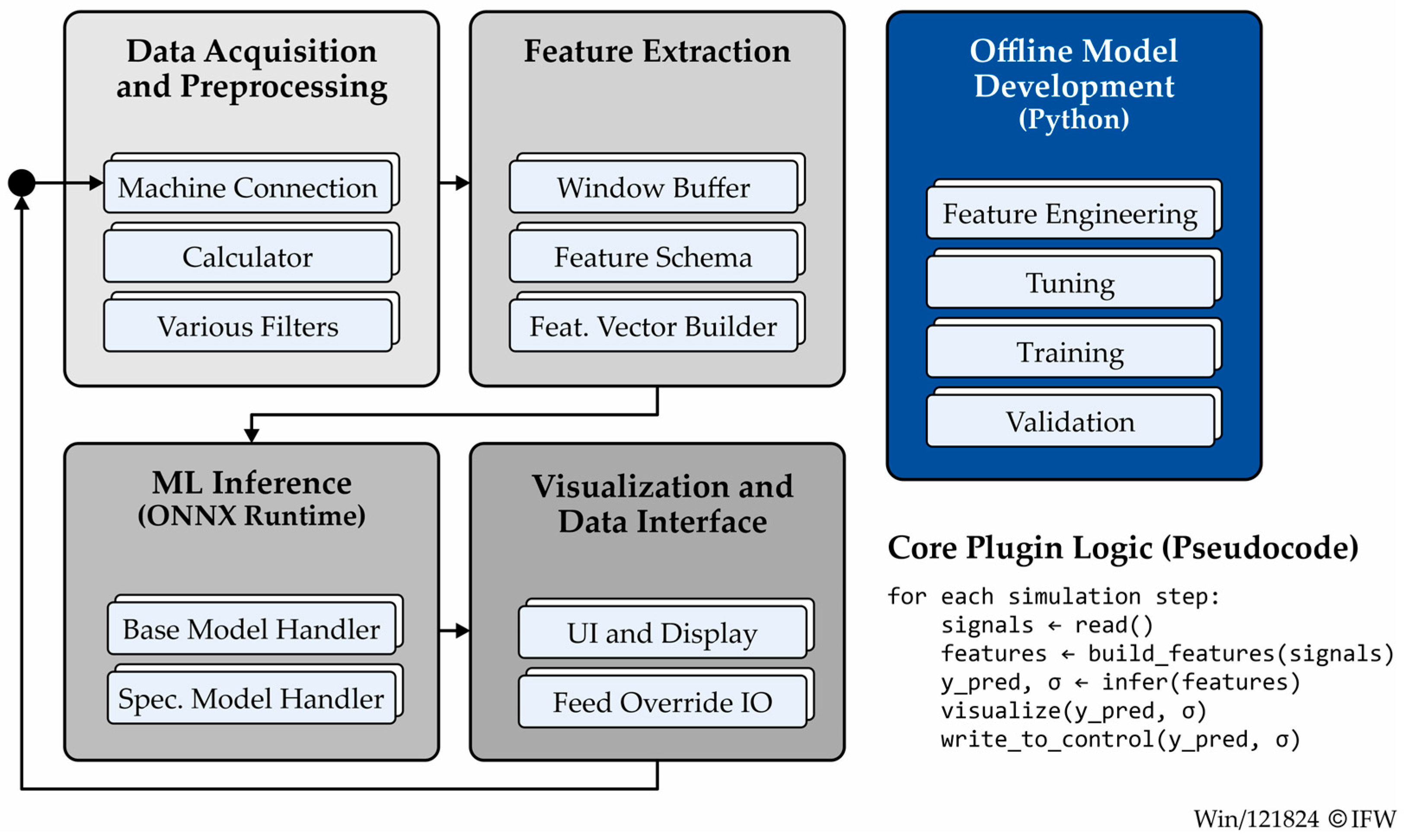

| Class/Python Script | Main Function |

|---|---|

| Machine connection | Provides a communication interface to the machine controller, managing all read and write handles for real-time process signals. |

| Calculator | Synchronizes simulation steps in IFW CutS, retrieves geometric and process values, and orchestrates data flow to the plugin modules. |

| Various filters | Implements Hampel, Kalman, and Butterworth filters for adaptive noise reduction and signal smoothing in real time. |

| Window buffer | Maintains sliding windows of time-series data for subsequent feature extraction; defines window size and step interval. |

| Feature schema | Stores the feature order and names consistent with the Python training to ensure identical model inputs. |

| Feature vector builder | Aggregates filtered signals within each window to numerical features (mean, RMS, slope, quantiles, etc.). |

| Base model handler | Generic ONNX Runtime interface responsible for loading and executing trained ML models. |

| Specific model handler | Concrete model implementation (e.g., XGBoost, Gaussian Process Regression, Neural Network) derived from the Base Model Handler. |

| UI and display | Windows Forms interface that visualizes measured and predicted process values in real time. |

| Feed override IO | Implements the functional logic for sending override or stop commands through the machine connection. |

| Python: feature engineering | Generates standardized feature sets from experimental data, including filtering, normalization, and windowing logic. |

| Python: tuning | Performs automated hyper-parameter optimization for each ML model using grouped cross-validation. |

| Python: training | Trains the final ML model (XGBoost, CNN, DNN, or GPR) on pre-processed data and exports the model to ONNX format. |

| Python: validation | Evaluates model accuracy on unseen hold-out groups and calibrates residual and uncertainty models |

| Dexel Density ρxyz [mm−1] | Cycle Time tcycle [s] | Feed Velocity vf [mm/min] |

|---|---|---|

| 5 10 13 16 20 | 0.00625 | |

| 0.0125 | 480 | |

| 0.075 | 960 | |

| 0.025 | 1440 | |

| 0.05 | 1920 | |

| 0.1 | 2400 | |

| 0.15 | 2880 | |

| 0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heide, K.M.; Denkena, B.; Winkler, M. A Bidirectional Digital Twin System for Adaptive Manufacturing. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120400

Heide KM, Denkena B, Winkler M. A Bidirectional Digital Twin System for Adaptive Manufacturing. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2025; 9(12):400. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120400

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeide, Klaas Maximilian, Berend Denkena, and Martin Winkler. 2025. "A Bidirectional Digital Twin System for Adaptive Manufacturing" Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 9, no. 12: 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120400

APA StyleHeide, K. M., Denkena, B., & Winkler, M. (2025). A Bidirectional Digital Twin System for Adaptive Manufacturing. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 9(12), 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120400