Processing and Development of Porous Titanium for Biomedical Applications: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

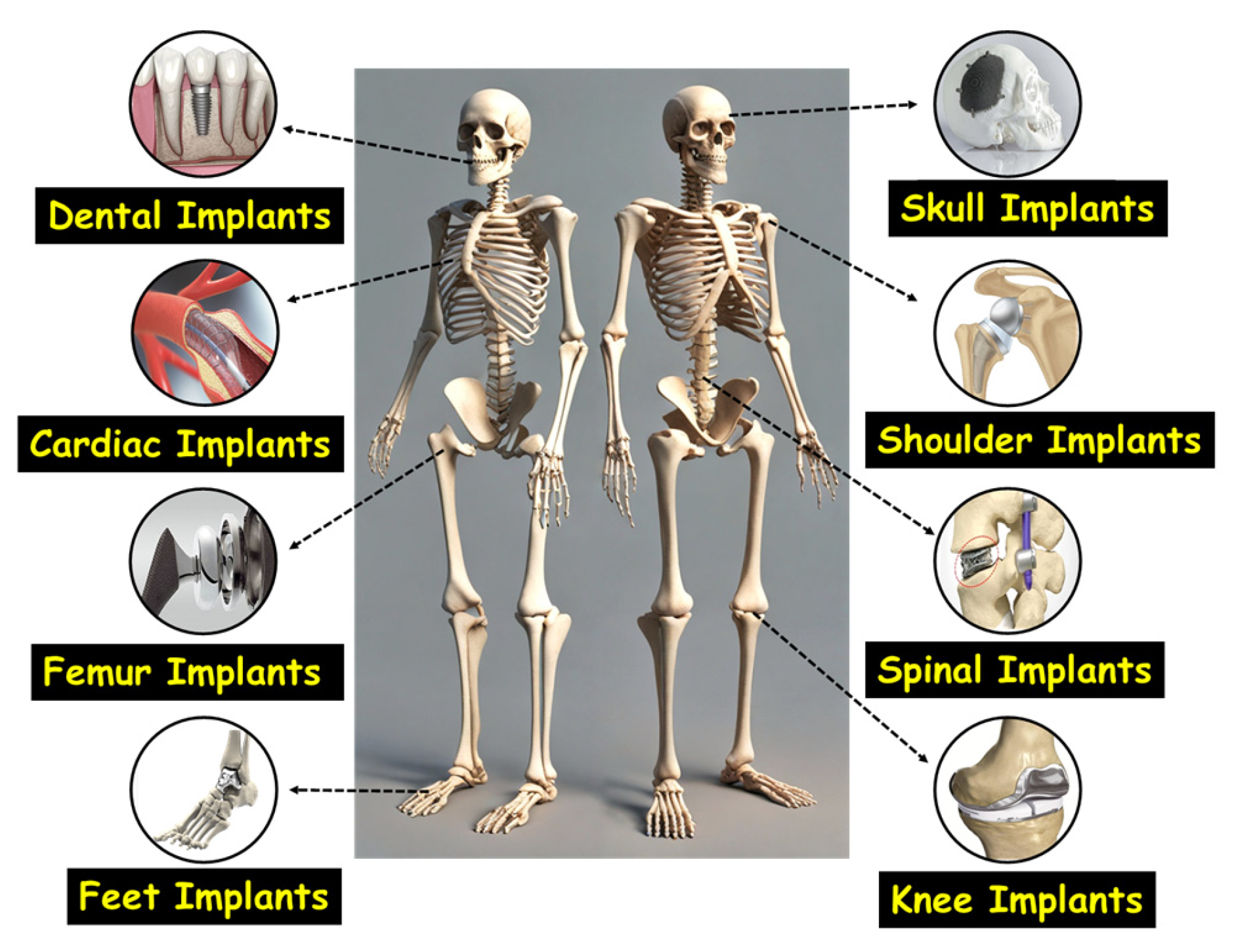

1. Introduction

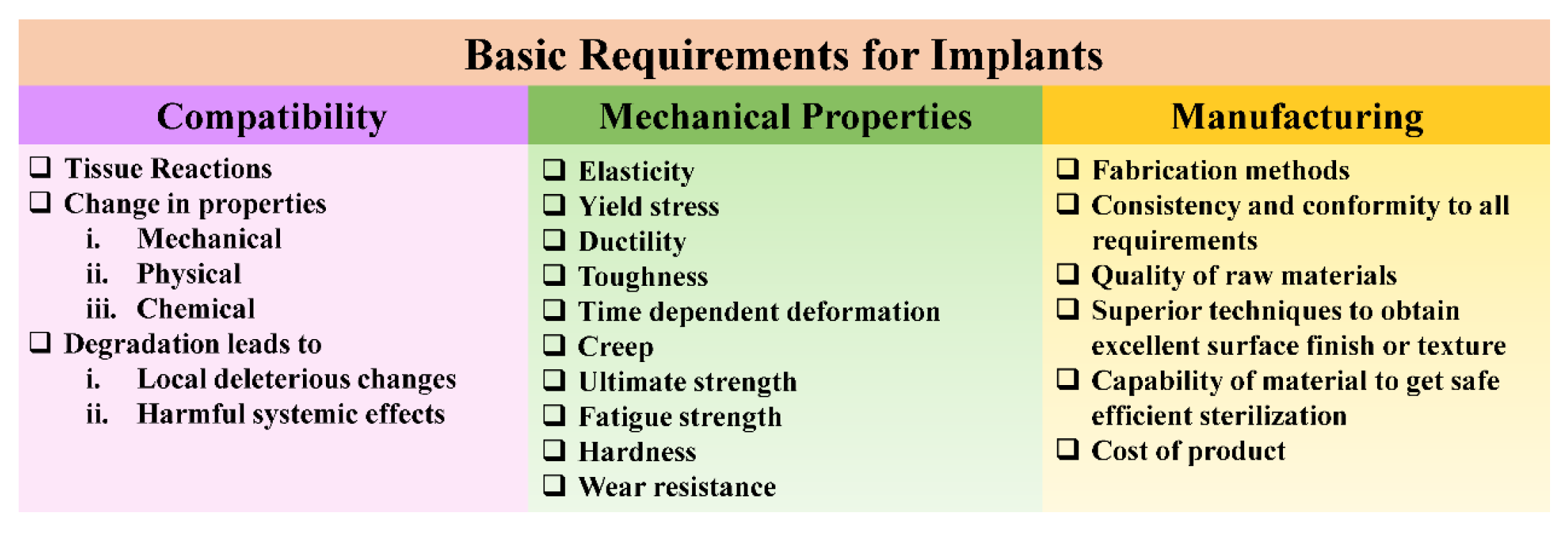

2. Material Characteristics Critical to Implant Functionality

2.1. Mechanical Properties

2.2. Corrosion and Wear Resistance

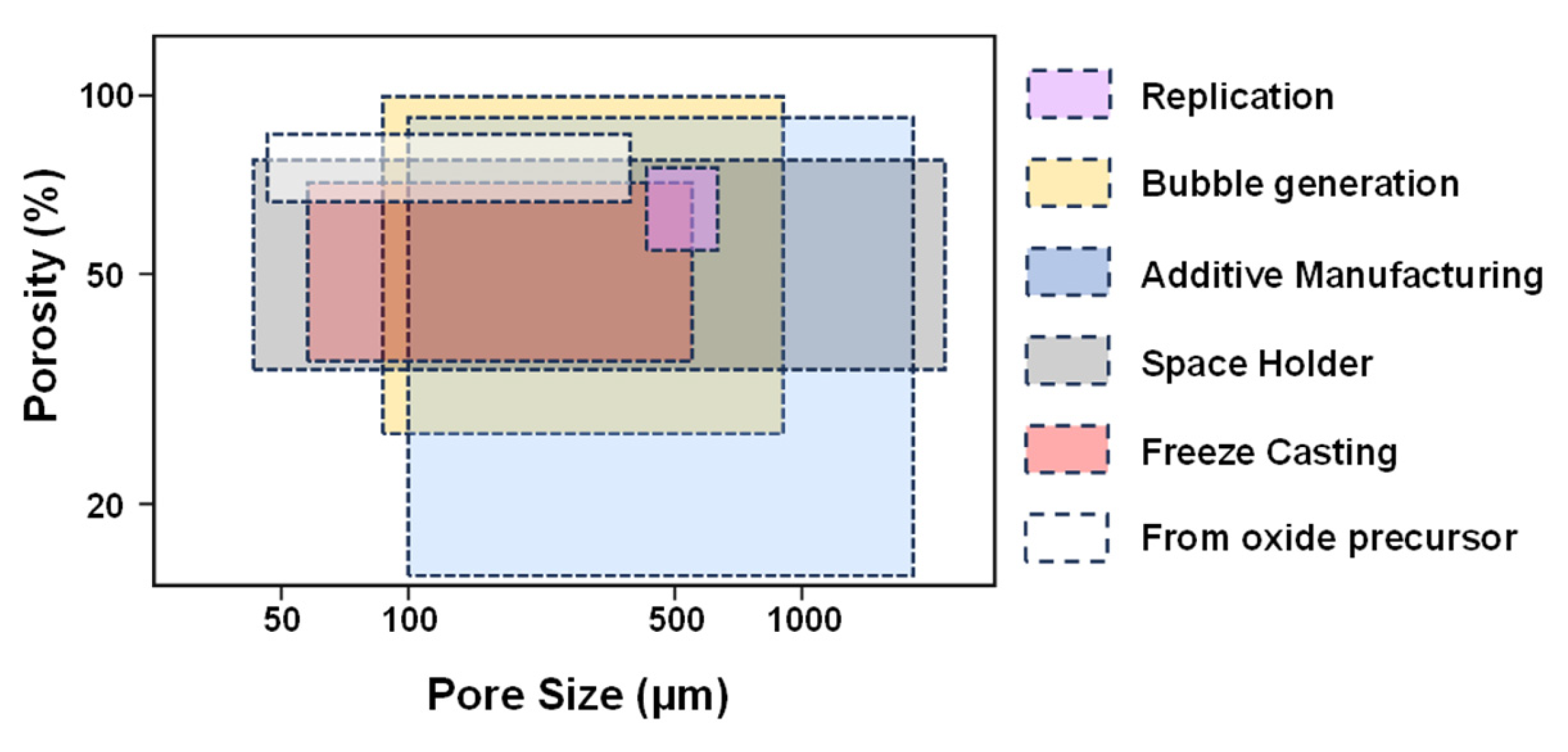

2.3. Porosity Effect

2.4. Surface Wettability and Its Role in Implant Performance

2.5. Biocompatibility

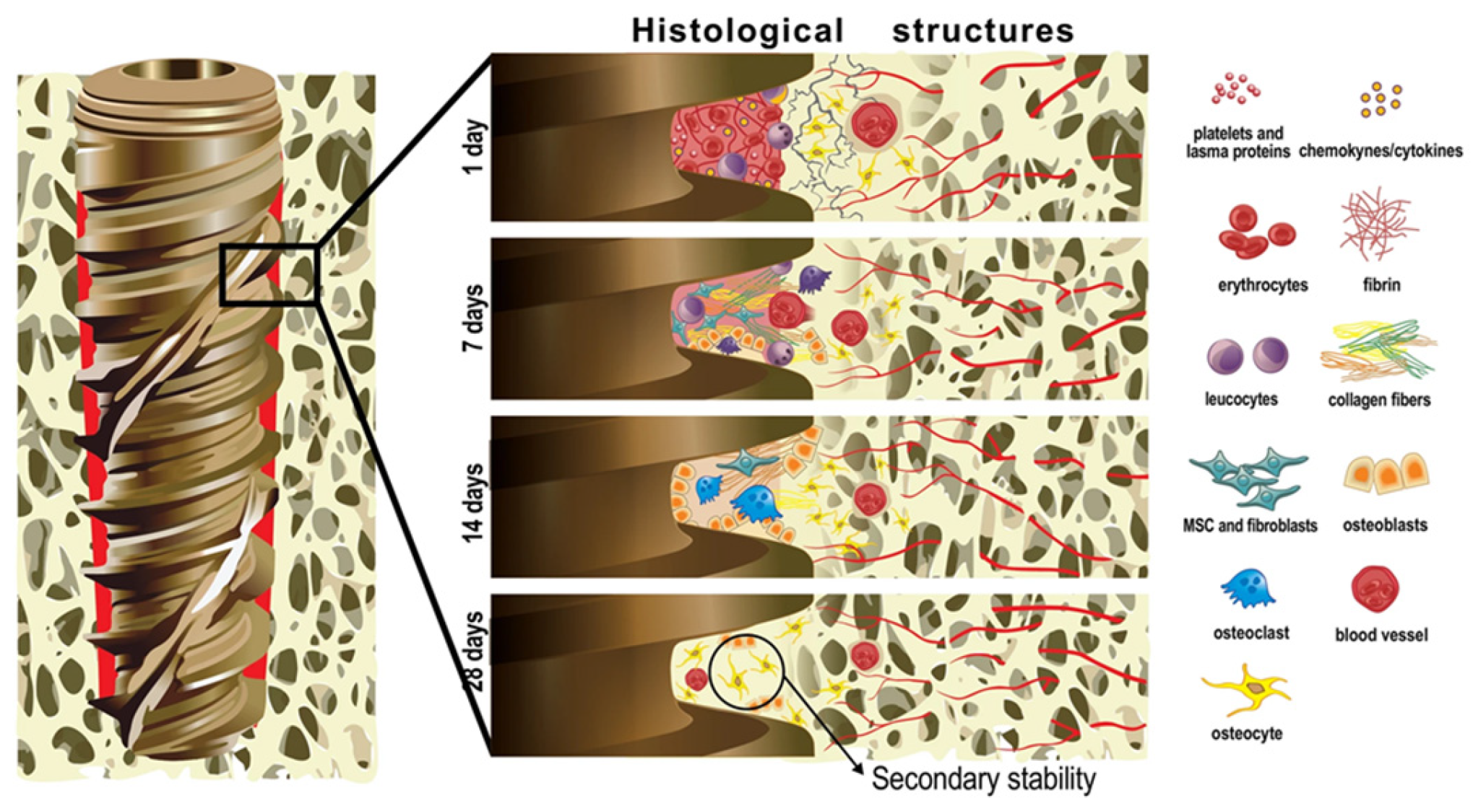

2.6. Osseointegration

3. Bone Metabolism

3.1. Bone Physiology

3.1.1. Woven Bone

3.1.2. Lamellar Bone

3.2. Chemical Composition of Bone

- An increase in overall mineral content;

- Greater carbonate substitution within the mineral structure;

- A reduction in acid phosphate substitution;

- Higher hydroxyl content;

- An elevated calcium-to-phosphorus (Ca/P) molar ratio;

- Growth in crystal size and improved crystallinity.

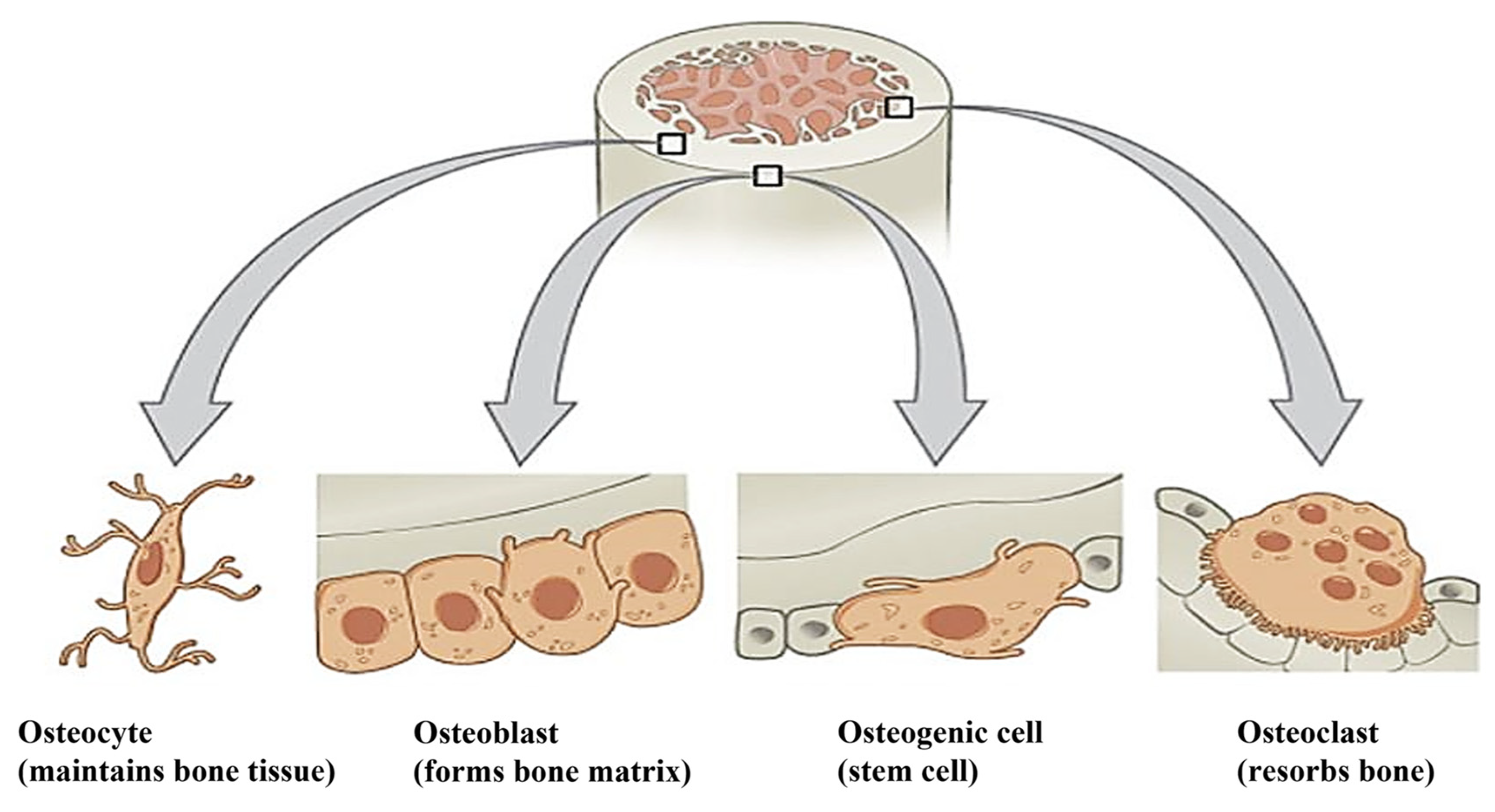

3.3. Types of Cells in the Bone

3.3.1. Osteoblasts

3.3.2. Osteocytes

3.3.3. Osteoclast

3.3.4. Osteogenic Cells

4. Materials Used for Orthopedic Implant Applications: Advantages and Disadvantages

| Material | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| SS 316L | Widely available and cost-effective, excellent mechanical properties, biocompatible | High elastic modulus, inadequate resistance to corrosion, low wear resistance, potential to trigger allergic reactions in surrounding tissues, and stress shielding, which can lead to bone resorption | Bone plates, bone screws, pins, wires, etc. |

| Co-Cr alloys | Excellent resistance to corrosion, fatigue, and wear. High mechanical strength. Sustained biocompatibility over the long term | High cost, limited machinability, induction of stress shielding, potential biological toxicity from the release of cobalt (Co), chromium (Cr), and nickel (Ni) ions | Shorter-term implants, bone plates and wires, total hip replacements (THR), and stem or hard-on-hard bearing system |

| Mg alloy | Biocompatible, biodegradable, bioresorbable, similar density, Young’s modulus is that of natural bone, less stress-shielding effect, and lightweight | Hydrogen evolution during degradation and less corrosion resistance | Bone screws, bone plates, bone pins, etc. |

| Ti alloy | Excellent resistance, lower modulus, stronger than stainless steel, lightweight, and biocompatible | Poor wear resistance, poor bending ductility, and expensive | Fracture fixation devices such as plates, nails, rods, screws, fasteners, and wires; femoral hip stems; total koint replacement (TJR) systems; and arthroplasty procedures, particularly for hip and knee joints |

| Alumina (Al2O3) | Biocompatibility and bio-inert behavior, elevated hardness, strength, resistance to abrasion, minimal formation of fibrous tissue at the implant–tissue interface | Low fracture toughness, brittleness, limited ductility, and radiopacity | Porous coatings for femoral stems, femoral head, bone screws and plates, and knee prosthesis |

| Zirconia (Zr2O3) | Excellent fracture toughness; high flexural strength; low Young’s modulus; closely matching that of bone; bio-inert nature; good biocompatibility; and non-toxic behavior within the biological environment | Phase transformation, brittleness, and low toughness | Femoral head, artificial knee, bone screws, and plates |

| Bioglass | Biocompatibility, bioactivity, promoting integration with surrounding tissue, non-toxicity, and brittleness, which may limit load-bearing applications | Brittleness, low tensile strength, and poor fatigue resistance | Artificial bone and dental implants |

| Hydroxyapatite (HAp) | Bio-resorbable, bioactive, biocompatible, similar composition to bone, and good osteoconductive properties | Brittleness, low tensile strength, and poor fatigue resistance | Femoral knee, femoral hips, tibial components, and acetabular cup |

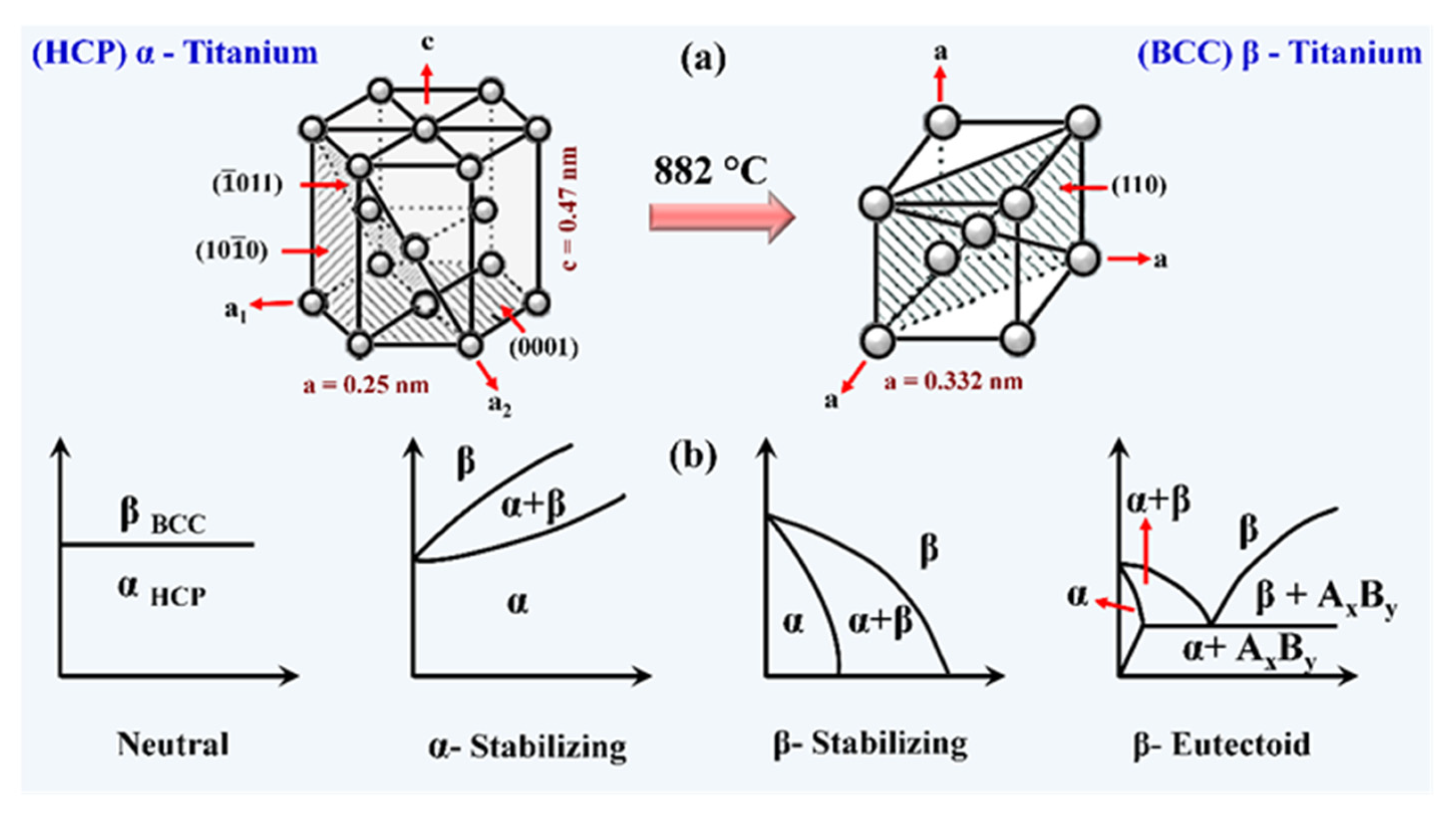

5. Titanium and Its Alloys: Material of Ultimate Choice for Implant Application

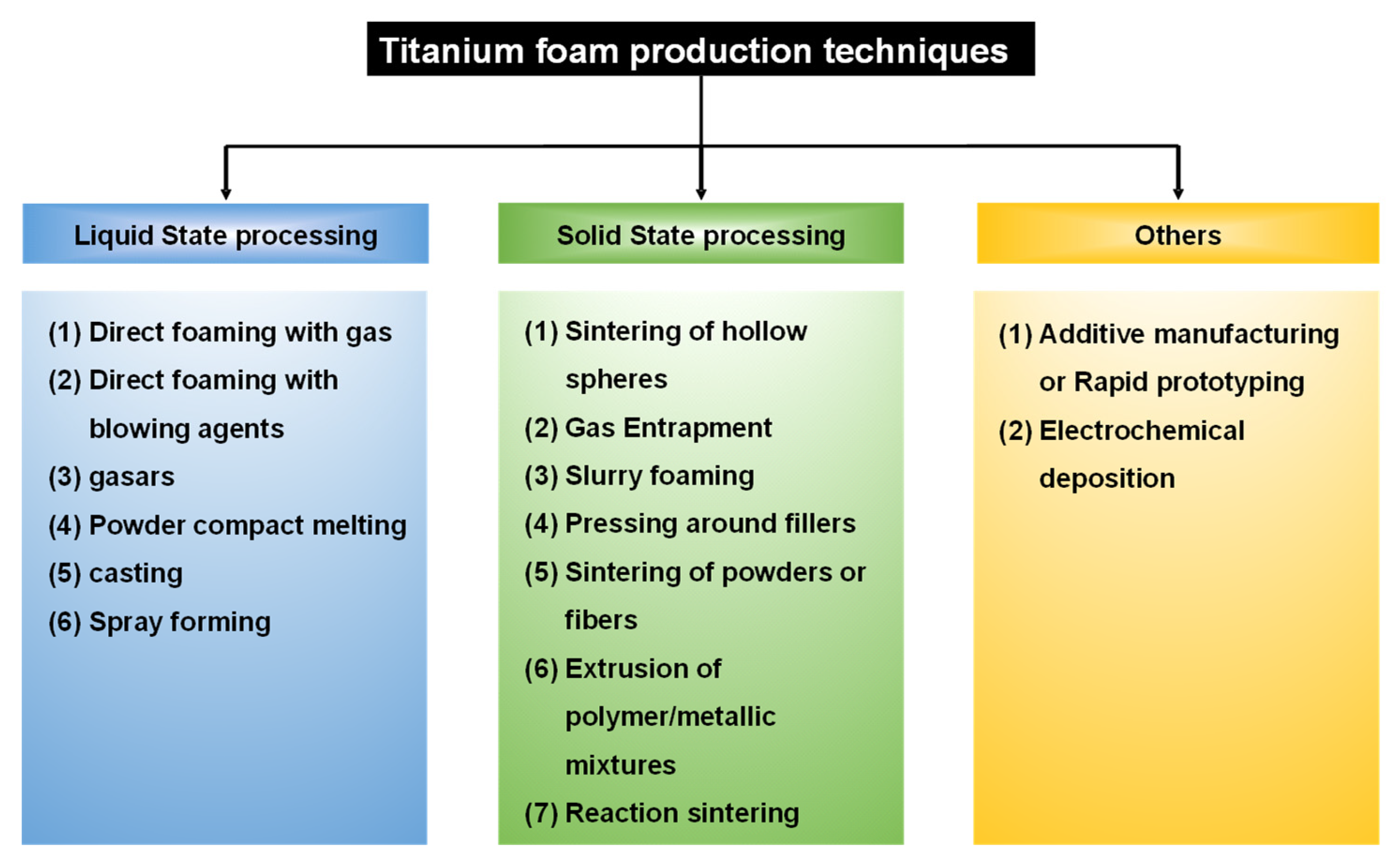

6. Fabrication of Porous Titanium Using Various Powder Metallurgical Techniques

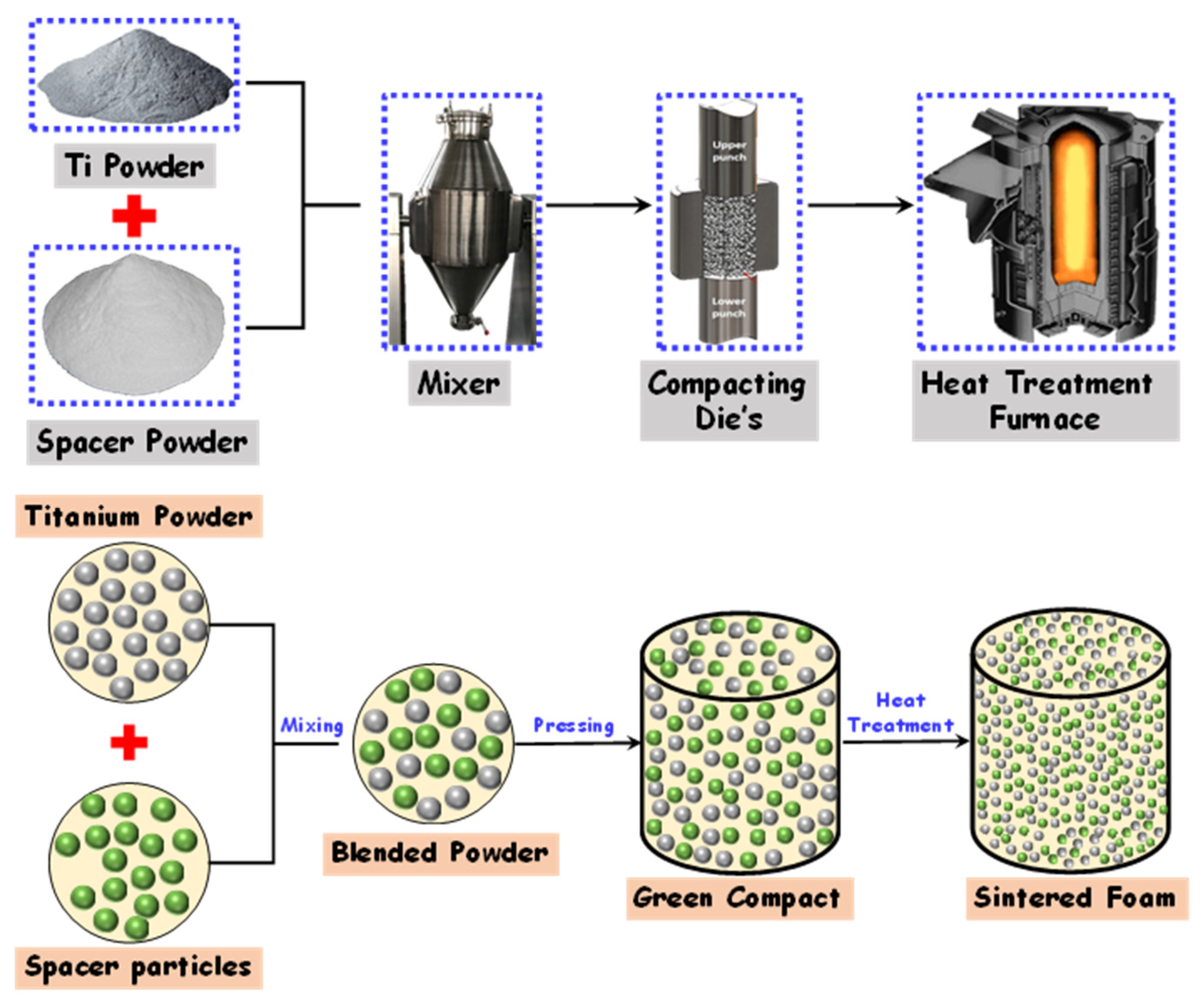

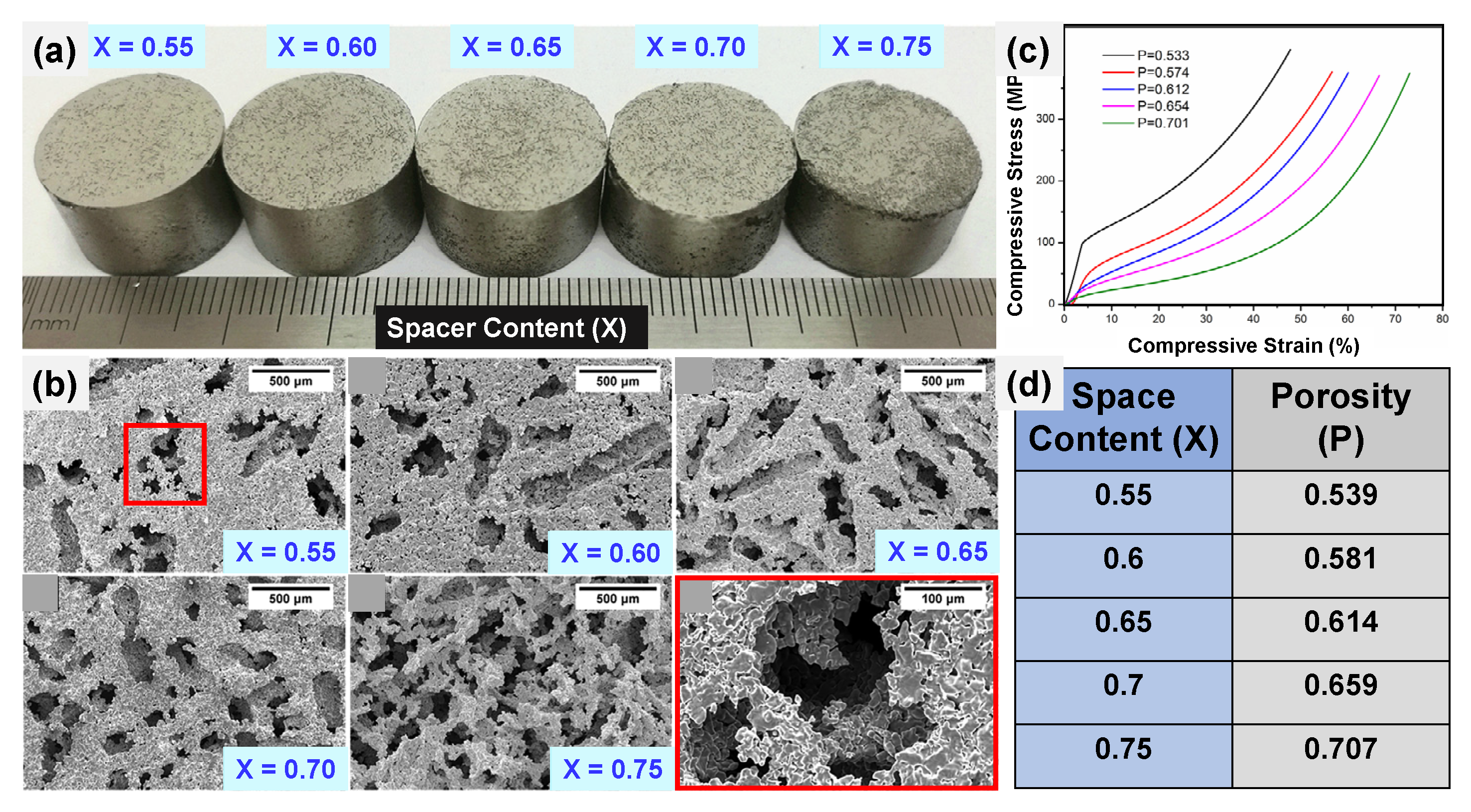

6.1. Space Holder Technique

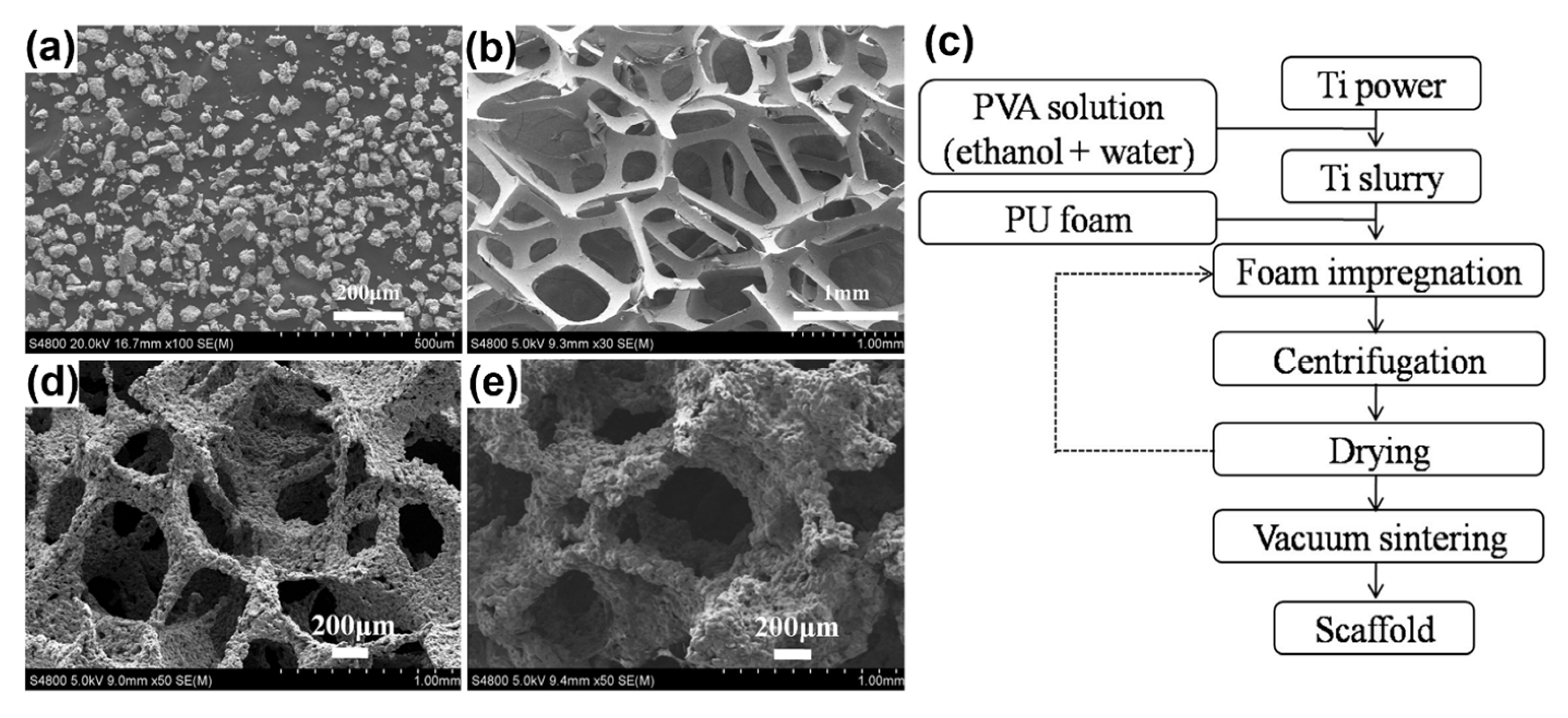

6.2. Replication Method

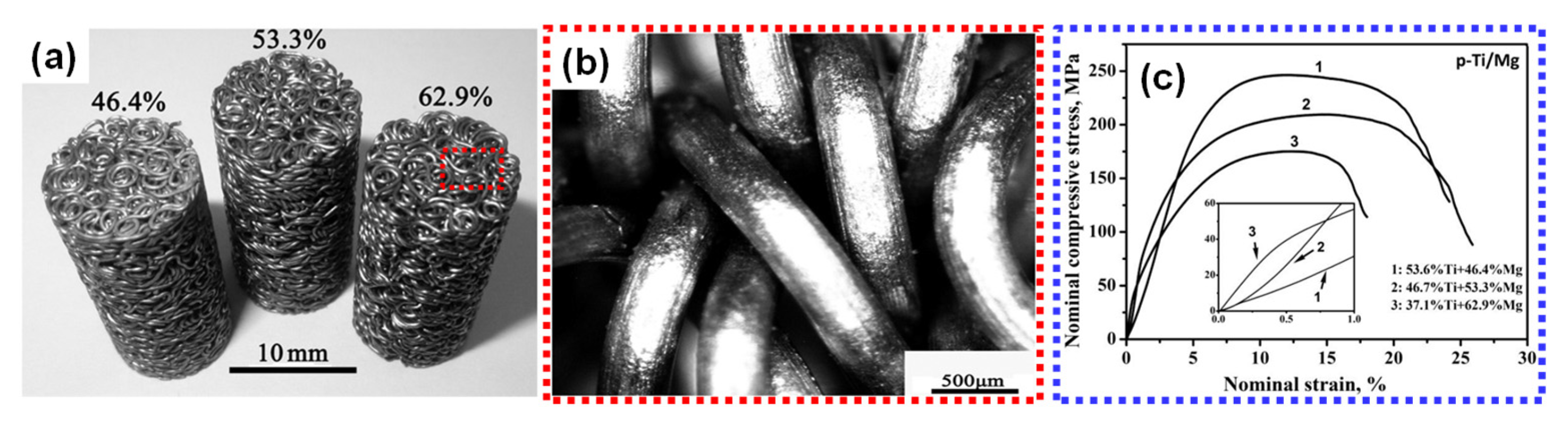

6.3. Entangled Metal Wire Technique

6.4. Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) and Hot Pressing (HP)

6.5. Microwave Sintering

| p | ST | TP | P | PS | E | YS | UCS | UTS | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spark plasma sintering | |||||||||

| Pure Ti | 750 | 16 MPa | Fully dense | - | ~125 | - | - | - | [210] |

| Pure Ti | 1000 | Pressureless | 53 | - | 40 | - | - | - | |

| Ti5Mn alloy | 950 | Pressureless | 56 | - | 35 | - | - | - | |

| Ti5Mn alloy | 1100 | Pressureless | 21 | - | 52 | - | - | - | |

| Pure Ti | 700 | - | 30–70 | 125–800 | 6–36 | 27–94 | - | - | [215] |

| β-alloy Ti-45Nb (gas-atomized) | 1000 | 10 min, 30 MPa | 0.5 ± 0.1 | - | 72 ± 1 | 550 | - | - | [216] |

| β-alloy Ti-45Nb (milled) | 1000 | 10 min, 30 MPa | 4.0 ± 0.2 | - | 72 ± 1 | 867 | - | - | [216] |

| Ti-6Al-4V | 700 | 3 min, 30 MPa | 32 ± 0.2 | - | - | - | 125 | - | [217] |

| Pure Ti | 600 | 3 min, 30 MPa | 32 ± 0.4 | - | - | - | 113 | - | [217] |

| CP Ti (Grade 1) Powder | 900 | 5 min, 60 MPa | - | - | - | 340 | - | 445 | [218,219] |

| Cryomilled nanocrystalline CP Ti (Grade 2) powder | 850 | - | - | - | - | 770 | - | 840 | |

| CP Ti (Grade 3) powder | 900 | 5 min, 60 MPa | - | - | - | 595 | - | 720 | |

| Wrought titanium grade 4 | - | 3 min, 80 MPa | - | - | - | 480–635 | - | 655–690 | |

| Hot pressing | |||||||||

| Ti-45Nb (gas-atomized) | 600 | 30 min, 700 MPa | 0.7 ± 0.2 | - | 70 ± 1 | 447 | - | - | [216] |

| Ti-45Nb (milled) | 600 | 30 min, 700 MPa | 3.7 ± 0.1 | - | 70 ± 1 | 940 | - | - | [216] |

| Microwave sintering | |||||||||

| Ti6Al4V/MWCNTi powder | 1620 | - | 25 | - | 11 ± 3 | 145 | 270 | - | [213] |

6.6. Additive Manufacturing (AM) or Rapid Prototyping (RP)

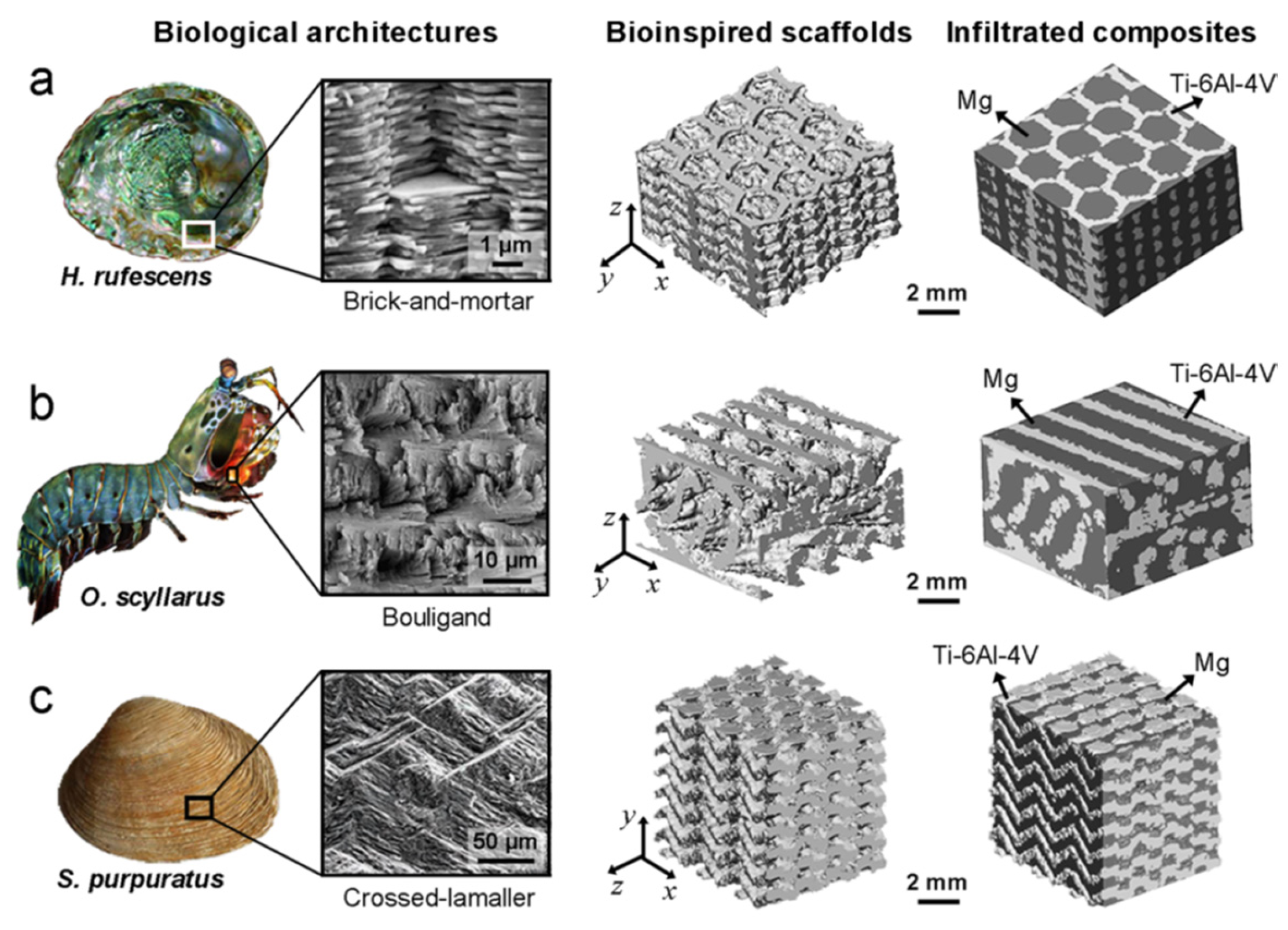

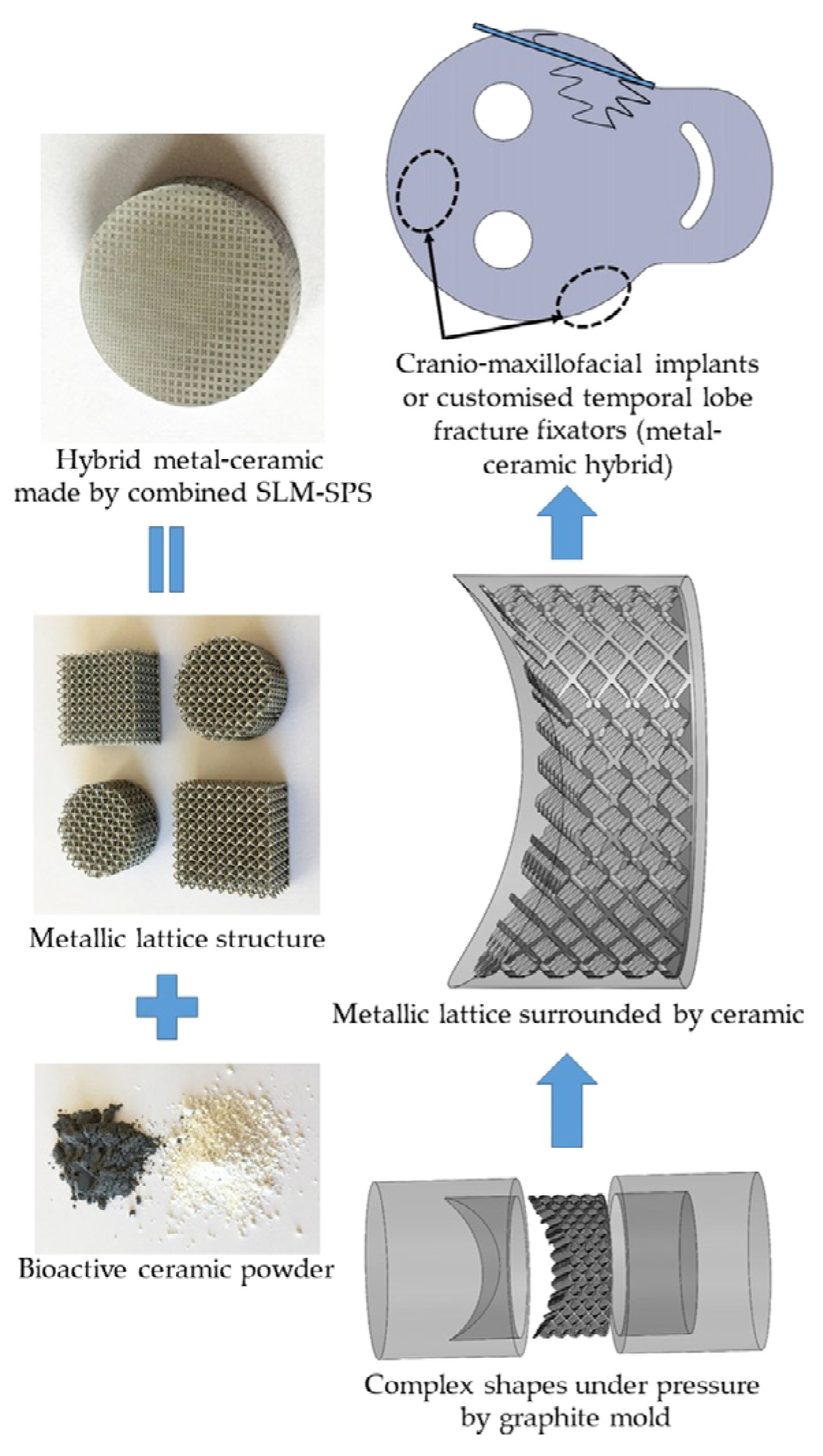

6.7. Recent Trends in the Development of Porous Ti Scaffold: Titanium-Based Interpenetrating Phase Composites

7. Current Challenges for Porous Titanium

- (1)

- Porous Ti implants are difficult to manufacture, and optimally controlling pores and maintaining the uniformity of pores are challenging tasks.

- (2)

- The interconnectivity of the pores is essential in determining the mechanical properties of the implants. It is paramount to maintain a tradeoff between the strength and porosity of porous Ti implants.

- (3)

- As implants undergo repeated cycles of loading and unloading during daily activities, the porous structures generally exhibit lower fatigue resistance compared to their dense counterpart. The pores serve as potential initiation points for fatigue cracks, which can gradually propagate and ultimately result in premature implant failure.

- (4)

- There must be a balance between patient-specific implants and large-scale production of implants, i.e., customization and production, since developing porous structures and meshing is time-consuming.

- (5)

- The implant cost should also be considered, as porous Ti implants are usually costlier than fully dense implants. Higher costs of implants reduce the demand in the market.

- (6)

- Implementing thorough checking to minimize defect concentration is important to obtain high-quality implants with better mechanical properties and biocompatibility.

- (7)

- Especially in the case of AM, thermal gradients can lead to variations in pore sizes and porosity levels.

- (8)

- The post-processing of the porous structures is also very difficult and time-consuming. It must be carried out carefully, as small disruptions can damage the interconnected structures, leading to defective implants.

8. Future Scope of Titanium-Based Porous Implants

- (1)

- AM has been gaining momentum in producing porous Ti structures. However, more efforts must be taken to fabricate porous structures with good pore interconnectivity, which will, in turn, pave the way for better mechanical properties and biocompatibility.

- (2)

- A biocompatible coating can be applied to enhance the osseointegration of the implant with body fluids.

- (3)

- Porous Ti structures can be used as multifunctional implants by integrating them with drug delivery systems or sensors.

- (4)

- Efforts should be made to make the porous Ti implants more accessible at an affordable price, which is possible through process optimization to achieve higher productivity at a lower cost.

- (5)

- Investigations of biocompatible joining strategies should be carried out for integrating porous Ti into various biomaterials or metallic implant structures.

- (6)

- The development of interpenetrating phase composites is limited to the Ti-Mg system since the developed composite has the potential to be utilized as an implant; therefore, a composite system comprising Ti-Zn/Ca/Fe and SS-Mg/Zn/Ca/Fe should be explored.

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cui, Y.W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.C. Towards Load-Bearing Biomedical Titanium-Based Alloys: From Essential Requirements to Future Developments. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2024, 144, 101277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banhart, J. Manufacture, Characterisation and Application of Cellular Metals and Metal Foams. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2001, 46, 559–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowski, B.; Swieszkowski, W.; Godlinski, D.; Kurzydlowski, K.J. Highly Porous Titanium Scaffolds for Orthopaedic Applications. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2010, 95, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabiyouni, M.; Brückner, T.; Zhou, H.; Gbureck, U.; Bhaduri, S.B. Magnesium-Based Bioceramics in Orthopedic Applications. Acta Biomater. 2018, 66, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; See, C.W.; Li, X.; Zhu, D. Orthopedic Implants and Devices for Bone Fractures and Defects: Past, Present and Perspective. Eng. Regen. 2020, 1, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer, P.P.; Kretlow, J.D.; Young, S.; Jansen, J.A.; Kasper, F.K.; Mikos, A.G. Evaluation of Bone Regeneration Using the Rat Critical Size Calvarial Defect. Nat. Protoc. 2012, 7, 1918–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oryan, A.; Alidadi, S.; Moshiri, A.; Maffulli, N. Bone Regenerative Medicine: Classic Options, Novel Strategies, and Future Directions. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2014, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Lawrence, J.G.; Bhaduri, S.B. Fabrication Aspects of PLA-CaP/PLGA-CaP Composites for Orthopedic Applications: A Review. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 1999–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.M. Biomaterials for Bone Tissue Engineering. Mater. Today 2008, 11, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, J.F.; McQueen, M.M. Substitutes for autologous bone graft in orthopaedic trauma. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. Vol. 2001, 83, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damien, C.J.; Parsons, J.R. Bone Graft and Bone Graft Substitutes: A Review of Current Technology and Applications. J. Appl. Biomater. 1991, 2, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hering, B.J.; Walawalkar, N. Pig-to-Nonhuman Primate Islet Xenotransplantation. Transpl. Immunol. 2009, 21, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishman, J.A.; Patience, C. Xenotransplantation: Infectious Risk Revisited. Am. J. Transplant. 2004, 4, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, D.K.C.; Ezzelarab, M.B.; Hara, H.; Iwase, H.; Lee, W.; Wijkstrom, M.; Bottino, R. The Pathobiology of Pig-to-Primate Xenotransplantation: A Historical Review. Xenotransplantation 2016, 23, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, M.; Singh, A.K.; Asokamani, R.; Gogia, A.K. Ti Based Biomaterials, the Ultimate Choice for Orthopaedic Implants—A Review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2009, 54, 397–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.K.; Pandey, V.; Jyoti; Kumar, A.; Mohanta, K.; Singh, V.K. Mechanical and Biological Behaviour of Porous Ti–SiO2 Scaffold for Tissue Engineering Application. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 22191–22200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Yadav, M.; Hiren Shukla, R.; Prashanth, K.G. A Comprehensive Review on Development of Waste Derived Hydroxyapatite (HAp) for Tissue Engineering Application. Mater. Today Proc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.K.; Pandey, V.; Mohanta, K.; Singh, V.K. A Low-Cost Approach to Develop Silica Doped Tricalcium Phosphate (TCP) Scaffold by Valorizing Animal Bone Waste and Rice Husk for Tissue Engineering Applications. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 25335–25345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ershad-Langroudi, A.; Babazadeh, N.; Alizadegan, F.; Mehdi Mousaei, S.; Moradi, G. Polymers for Implantable Devices. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2024, 137, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Srikanth, K.P.; Gopal, V.; Rajput, M.; Manivasagam, G.; Prashanth, K.G.; Chatterjee, K.; Suwas, S. In Situ Production of Low-Modulus Ti–Nb Alloys by Selective Laser Melting and Their Functional Assessment toward Orthopedic Applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 5982–5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ummethala, R.; Karamched, P.S.; Rathinavelu, S.; Singh, N.; Aggarwal, A.; Sun, K.; Ivanov, E.; Kollo, L.; Okulov, I.; Eckert, J.; et al. Selective Laser Melting of High-Strength, Low-Modulus Ti–35Nb–7Zr–5Ta Alloy. Materialia 2020, 14, 100941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, P.; Liu, C.F.; Ummethala, R.; Singh, N.; Huang, H.H.; Manivasagam, G.; Prashanth, K.G. Biomorphic Porous Ti6Al4V Gyroid Scaffolds for Bone Implant Applications Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 6, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, P.A.; Raheem, A.; Kalirajan, C.; Prashanth, K.G.; Manivasagam, G. In Vivo Assessment of a Triple Periodic Minimal Surface Based Biomimmetic Gyroid as an Implant Material in a Rabbit Tibia Model. ACS Mater. Au 2024, 4, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neto, J.V.C.; Teixeira, A.B.V.; Cândido dos Reis, A. Hydroxyapatite Coatings versus Osseointegration in Dental Implants: A Systematic Review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2023, 134, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salahinejad, E.; Vahedifard, R. Deposition of Nanodiopside Coatings on Metallic Biomaterials to Stimulate Apatite-Forming Ability. Mater. Des. 2017, 123, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, R.; Lopes, S.I.; Prashanth, K.G. Selective Laser Melting and Spark Plasma Sintering: A Perspective on Functional Biomaterials. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, R.; Kamboj, N.; Brojan, M.; Antonov, M.; Prashanth, K.G. Hybrid Metal-Ceramic Biomaterials Fabricated through Powder Bed Fusion and Powder Metallurgy for Improved Impact Resistance of Craniofacial Implants. Materialia 2022, 24, 101465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, R.; Antonov, M.; Kollo, L.; Holovenko, Y.; Prashanth, K.G. Mechanical Behavior of Ti6Al4V Scaffolds Filled with CaSiO3 for Implant Applications. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, N.; Rodríguez, M.A.; Rahmani, R.; Prashanth, K.G.; Hussainova, I. Bioceramic Scaffolds by Additive Manufacturing for Controlled Delivery of the Antibiotic Vancomycin. Proc. Est. Acad. Sci. 2019, 68, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shalawi, F.D.; Azmah Hanim, M.A.; Ariffin, M.K.A.; Looi Seng Kim, C.; Brabazon, D.; Calin, R.; Al-Osaimi, M.O. Biodegradable Synthetic Polymer in Orthopaedic Application: A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 74, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveenkumar, K.; Manivasagam, G.; Swaroop, S. Effect of Laser Peening on the Residual Stress Distribution and Wettability Characteristics of Ti-6Al-4V Alloy for Biomedical Applications. Trends Biomater. Artif. Organs 2022, 36, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Arabnejad, S.; Johnston, B.; Tanzer, M.; Pasini, D. Fully Porous 3D Printed Titanium Femoral Stem to Reduce Stress-Shielding Following Total Hip Arthroplasty. J. Orthop. Res. 2017, 35, 1774–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engler, I.D.; Hart, P.A.; Swanson, D.P.; Kirsch, J.M.; Murphy, J.P.; Wright, M.A.; Murthi, A.; Jawa, A. High Prevalence of Early Stress Shielding in Stemless Shoulder Arthroplasty. Semin. Arthroplast. JSES 2022, 32, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagels, J.; Stokdijk, M.; Rozing, P.M. Stress Shielding and Bone Resorption in Shoulder Arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2003, 12, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveenkumar, K.; Vishnu, J.; Samuel S., C.; Gopal, V.; Arivarasu, M.; Lackner, J.M.; Meier, B.; Karthik, D.; Suwas, S.; Swaroop, S.; et al. High Temperature Dry Sliding Wear Behaviour of Selective Laser Melted Ti-6Al-4V Alloy Surfaces. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2024, 329, 118439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveenkumar, K.; Swaroop, S.; Manivasagam, G. Effect of Multiple Laser Shock Peening without Coating on Residual Stress Distribution and High Temperature Dry Sliding Wear Behaviour of Ti-6Al-4 V Alloy. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 164, 109398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveenkumar, K.; Mylavarapu, P.; Sarkar, A.; Isaac Samuel, E.; Nagesha, A.; Swaroop, S. Residual Stress Distribution and Elevated Temperature Fatigue Behaviour of Laser Peened Ti-6Al-4V with a Curved Surface. Int. J. Fatigue 2022, 156, 106641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveenkumar, K.; Vishnu, J.; Raheem, A.; Gopal, V.; Swaroop, S.; Suwas, S.; Shankar, B.; Manivasagam, G. In-Vitro Fretting Tribocorrosion and Biocompatibility Aspects of Laser Shock Peened Ti-6Al-4V Surfaces. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 665, 160334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Mitra, I.; Goodman, S.B.; Kumar, M.; Bose, S. Improving Biocompatibility for next Generation of Metallic Implants. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 133, 101053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Gong, C.; Chen, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cai, L.; Zhu, S.; Xie, S.Q. Additive Manufacturing of Customized Metallic Orthopedic Implants: Materials, Structures, and Surface Modifications. Metals 2019, 9, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donachie, M.J. Titanium: A Technical Guide; ASM International: Almere, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanan, A.; Haines, S.J. Repairing Holes in the Head: A History of Cranioplasty. Neurosurgery 1997, 40, 588–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praveenkumar, K.; Mylavarapu, P.; Swaroop, S. Surface Oxidation and Subsurface Deformation in a Laser-Peened Ti-6Al-4V. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2023, 32, 7348–7362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnu, J.; Praveenkumar, K.; Kumar, A.A.; Nair, A.; Arjun, R.; Pillai, V.G.; Shankar, B.; Shankar, K.V. Multifunctional Zinc Oxide Loaded Stearic Acid Surfaces on Biodegradable Magnesium WE43 Alloy with Hydrophobic, Self-Cleaning and Biocompatible Attributes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 680, 161455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoerke, E.D.; Murray, N.G.; Li, H.; Brinson, L.C.; Dunand, D.C.; Stupp, S.I. A Bioactive Titanium Foam Scaffold for Bone Repair. Acta Biomater. 2005, 1, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, U.; Imwinkelried, T.; Horst, M.; Sievers, M.; Graf-Hausner, U. Do Human Osteoblasts Grow into Open-Porous Titanium? Cell Mater 2006, 11, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohler, O.E.M. Unalloyed Titanium for Implants in Bone Surgery. Injury 2000, 31, D7–D13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Leong, K.F.; Du, Z.; Chua, C.K. The Design of Scaffolds for Use in Tissue Engineering. Part I. Traditional Factors. Tissue Eng. 2001, 7, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, T.; Balcı, Ö.; Gammer, C.; Ivanov, E.; Eckert, J.; Prashanth, K.G. High Pressure Torsion Induced Lowering of Young’s Modulus in High Strength TNZT Alloy for Bio-Implant Applications. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 108, 103839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, S.; Samuel, S.; Puthucode, A.; Banerjee, R. Characterization of Novel Borides in Ti-Nb-Zr-Ta + 2B Metal-Matrix Composites. Mater. Charact. 2009, 60, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.P.; Huang, Y.J.; Xu, J.Y.; Sun, J.F.; Dargusch, M.S.; Hou, C.H.; Ren, L.; Wang, R.Z.; Ebel, T.; Yan, M. Additively Manufactured Biomedical Ti-Nb-Ta-Zr Lattices with Tunable Young’s Modulus: Mechanical Property, Biocompatibility, and Proteomics Analysis. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 114, 110903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahay, S.; Kesavan, P.; Yadav, M.K.; Nilawar, S.; Manivasagam, G.; Chatterjee, K. High-Pressure Torsion Affects Mechanical Properties, Electrochemical Behavior, and Cellular Response to a Biomedical Ti-Nb-Zr-Ta Alloy. Mater. Trans. 2025, 66, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.N.; White, E.W. Carbon-Metal Graded Composites for Permanent Osseous Attachment of Non-Porous Metals. Mater. Res. Bull. 1972, 7, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashanth, K.; Zhuravleva, K.; Okulov, I.; Calin, M.; Eckert, J.; Gebert, A. Mechanical and Corrosion Behavior of New Generation Ti-45Nb Porous Alloys Implant Devices. Technologies 2016, 4, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; He, Z.Y.; Tan, J.; Calin, M.; Prashanth, K.G.; Sarac, B.; Völker, B.; Jiang, Y.H.; Zhou, R.; Eckert, J. Designing a Multifunctional Ti-2Cu-4Ca Porous Biomaterial with Favorable Mechanical Properties and High Bioactivity. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 727, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar, H.; Löber, L.; Funk, A.; Calin, M.; Zhang, L.C.; Prashanth, K.G.; Scudino, S.; Zhang, Y.S.; Eckert, J. Mechanical Behavior of Porous Commercially Pure Ti and Ti-TiB Composite Materials Manufactured by Selective Laser Melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 625, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravleva, K.; Bönisch, M.; Prashanth, K.G.; Hempel, U.; Helth, A.; Gemming, T.; Calin, M.; Scudino, S.; Schultz, L.; Eckert, J.; et al. Production of Porous β-Type Ti-40Nb Alloy for Biomedical Applications: Comparison of Selective Laser Melting and Hot Pressing. Materials 2013, 6, 5700–5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.P.; Mikos, A.G.; Bronzino, J.D. Tissue Engineering. Science 1993, 260, 1–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutmacher, D.W. Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering Bone and Cartilage. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 2529–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pałka, K.; Pokrowiecki, R. Porous Titanium Implants: A Review. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2018, 20, 1700648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koju, N.; Niraula, S.; Fotovvati, B. Additively Manufactured Porous Ti6Al4V for Bone Implants: A Review. Metals 2022, 12, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinomi, M.; Nakai, M.; Hieda, J. Development of New Metallic Alloys for Biomedical Applications. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 3888–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, H.M. Bone’s Mechanostat: A 2003 Update. Anat. Rec. Part A Discov. Mol. Cell. Evol. Biol. 2003, 275, 1081–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, M.J.; Van Der Meulen, M.C.H.; Demetrakopoulos, D.; Wright, T.M.; Myers, E.R.; Bostrom, M.P. In Vivo Cyclic Axial Compression Affects Bone Healing in the Mouse Tibia. J. Orthop. Res. 2006, 24, 1679–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozec, L.; Horton, M.A. Skeletal Tissues as Nanomaterials. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2006, 17, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Rack, H.J. Titanium Alloys in Total Joint Replacement—A Materials Science Perspective. Biomaterials 1998, 19, 1621–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, D.R.; Turner, T.M.; Igloria, R.; Urban, R.M.; Galante, J.O. Functional Adaptation and Ingrowth of Bone Vary as a Function of Hip Implant Stiffness. J. Biomech. 1998, 31, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Witte, F.; Lu, F.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Qin, L. Current Status on Clinical Applications of Magnesium-Based Orthopaedic Implants: A Review from Clinical Translational Perspective. Biomaterials 2017, 112, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Curtin, J.; Duffy, B.; Jaiswal, S. Biodegradable Magnesium Alloys for Orthopaedic Applications: A Review on Corrosion, Biocompatibility and Surface Modifications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 68, 948–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuchukwu, O.A.; Salihi, A.; Abdullahi, I.; Obada, D.O.; Abolade, S.A.; Akande, A.; Csaki, S.; Dodoo-Arhin, D. Datasets on the Elastic and Mechanical Properties of Hydroxyapatite: A First Principle Investigation, Experiments, and Pedagogical Perspective. Data Brief 2023, 48, 109075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piconi, C.; Maccauro, G. Zirconia as a Ceramic Biomaterial. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar, H.; Prashanth, K.G.; Chaubey, A.K.; Calin, M.; Zhang, L.C.; Scudino, S.; Eckert, J. Comparison of Wear Properties of Commercially Pure Titanium Prepared by Selective Laser Melting and Casting Processes. Mater. Lett. 2015, 142, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Hou, L.; Sun, J.; Li, D.; Song, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Q.; Wei, Y. Regulating the Localized Corrosion of Grain Boundary and Galvanic Corrosion by Adding the Electronegative Element in Magnesium Alloy. Corros. Sci. 2025, 244, 112667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Iftikhar, T.; Liu, H. “Electrons-Siphoning” of Sulfate Reducing Bacteria Biofilm Induced Sharp Depletion of Al-Zn-In-Mg-Si Sacrificial Anode in the Galvanic Corrosion Coupled with Carbon Steel. Corros. Sci. 2023, 216, 111103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K.; Sakairi, M.; Fushimi, K. Ion-Selectivity of Galvanic Corrosion Products Formed in Multi-Material Gaps under Atmospheric Corrosion Conditions with Anti-Freezing Salts. Corros. Sci. 2024, 237, 112305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, L.C.; Buchanan, R.A.; Lemons, J.E. Investigations on the Galvanic Corrosion of Multialloy Total Hip Prostheses. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1981, 15, 731–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szklarska-Smialowska, Z. Pitting Corrosion of Aluminum. Corros. Sci. 1999, 41, 1743–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loto, R.T. Pitting Corrosion Resistance and Inhibition of Lean Austenitic Stainless Steel Alloys. Austenitic Stainl. Steels New Asp. 2017, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Liu, J.H.; Yu, M.; Li, S.M. Through-Thickness Inhomogeneity of Precipitate Distribution and Pitting Corrosion Behavior of Al–Li Alloy Thick Plate. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2019, 29, 1793–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCafferty, E. Introduction to Corrosion Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; ISBN 9781441904546. [Google Scholar]

- Prashanth, K.G.; Debalina, B.; Wang, Z.; Gostin, P.F.; Gebert, A.; Calin, M.; Kühn, U.; Kamaraj, M.; Scudino, S.; Eckert, J. Tribological and Corrosion Properties of Al-12Si Produced by Selective Laser Melting. J. Mater. Res. 2014, 29, 2044–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, T.; Kato, C. Introduction of Cu2+ to the inside of the Crevice by Chelation and Its Effect on Crevice Corrosion of Type 316L Stainless Steel. Corros. Sci. 2023, 210, 110850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Xu, D.; Wang, F. Electroactive Shewanella Algae Accelerates the Crevice Corrosion of X70 Pipeline Steel in Marine Environment. Corros. Sci. 2024, 235, 112226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Z.; Qiao, L.; Su, Y.; Yan, Y. Role of Protein in Crevice Corrosion of CoCrMo Alloy: An Investigation Using Wire Beam Electrodes. Corros. Sci. 2023, 215, 111028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, D.L.; Staehle, R.W. Crevice Corrosion in Orthopedic Implant Metals. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1977, 11, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uva Narayanan, C.; Daniel, A.; Praveenkumar, K.; Manivasagam, G.; Suwas, S.; Prashanth, K.G.; Suya Prem Anand, P. Effect of Scanning Speed on Mechanical, Corrosion, and Fretting-Tribocorrosion Behavior of Austenitic 316L Stainless Steel Produced by Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process. J. Manuf. Process 2024, 131, 1582–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.Z.; Lu, Y.H.; Bian, W.W.; Yu, P.J.; Wang, Y.B.; Xin, L.; Han, Y.M. Fretting Corrosion Behavior and Microstructure Evolution of Hydrided Zirconium Alloy under Gross Slip Regime in High Temperature High Pressure Water Environment. Corros. Sci. 2025, 242, 112582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, W.W.; Lu, Y.H.; Zhang, X.F.; Han, Y.M.; Wang, F.; Shoji, T. Effect of Fretting Wear Regimes on Stress Corrosion Cracking of Alloy 690TT in High-Temperature Pressurized Water. Corros. Sci. 2024, 237, 112320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, A.; Goswami, T. Hip Implants: Paper V. Physiological Effects. Mater. Des. 2006, 27, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Choudhury, D.; Roy, T.; Moradi, A.; Masjuki, H.H.; Pingguan-Murphy, B. Tribological Performance of the Biological Components of Synovial Fluid in Artificial Joint Implants. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2015, 16, 045002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliaz, N. Corrosion of Metallic Biomaterials: A Review. Materials 2019, 12, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.; Lee, Y.N.; Shin, W.Y.; Kim, K.H.; Jung, S.H.; Kang, H.G.; Kim, R.; Sung, H.; Jung, I.D.; Park, J.W. Structural Influence on Titanium Ion Dissolution in 3D-Printed Ti6Al4V Orthopedic Implants. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermawan, H.; Razavi, M. Absorbable Metals for Biomedical Applications; MDPI-Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute: Basel, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 9783036517643. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, M.M.; Swaroop, S. Impact of the Oxide Layer and Subsurface Micromechanical Properties of Laser Peened 31L Stainless Steel on Biocorrosion Resistance in Simulated Body Fluid. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 56, 105672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashanth, K.G. Interpenetrating Composites: A Nomenclature Dilemma. Materials 2025, 18, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Prashanth, K.G. Metal-Metal Interpenetrating Phase Composites: A Review. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1009, 176951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, N.; Hamlet, S.; Love, R.M.; Nguyen, N.T. Porous Scaffolds for Bone Regeneration. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 2020, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuboki, Y.; Takita, H.; Kobayashi, D.; Tsuruga, E.; Inoue, M.; Murata, M.; Nagai, N.; Dohi, Y.; Ohgushi, H. BMP-Induced Osteogenesis on the Surface of Hydroxyapatite with Geometrically Feasible and Nonfeasible Structures: Topology of Osteogenesis. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1998, 39, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; Wang, Z.; Lu, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, G.; Lv, R.; Wang, J.; Lin, K.; Zhang, J.; Huang, X. The Correlation between the Internal Structure and Vascularization of Controllable Porous Bioceramic Materials in Vivo: A Quantitative Study. Tissue Eng. Part A 2010, 16, 3791–3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.X.; Flautre, B.; Anselme, K.; Hardouin, P.; Gallur, A.; Descamps, M.; Thierry, B. Role of Interconnections in Porous Bioceramics on Bone Recolonization in Vitro and in Vivo. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 1999, 10, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hady Gepreel, M.; Niinomi, M. Biocompatibility of Ti-Alloys for Long-Term Implantation. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2013, 20, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, B.W.; Weinstein, A.M.; Klawitter, J.J.; Hulbert, S.F.; Leonard, R.B.; Bagwell, J.G. The Role of Porous Polymeric Materials in Prosthesis Attachment. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1974, 8, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewidar, M.M.; Lim, J.K. Properties of Solid Core and Porous Surface Ti–6Al–4V Implants Manufactured by Powder Metallurgy. J. Alloys Compd. 2008, 454, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laptev, A.; Vyal, O.; Bram, M.; Buchkremer, H.P.; Stöver, D. Green Strength of Powder Compacts Provided Production of Highly Porous Titanium Parts. Powder Metall. 2005, 48, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittens, R.A.; Scheideler, L.; Rupp, F.; Hyzy, S.L.; Geis-Gerstorfer, J.; Schwartz, Z.; Boyan, B.D. A Review on the Wettability of Dental Implant Surfaces II: Biological and Clinical Aspects. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 2907–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peta, K.; Kubiak, K.J.; Sfravara, F.; Brown, C.A. Dynamic Wettability of Complex Fractal Isotropic Surfaces—Multiscale Correlations. Tribol. Int. 2026, 214, 111145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peta, K.; Bartkowiak, T.; Rybicki, M.; Galek, P.; Mendak, M.; Wieczorowski, M.; Brown, C.A. Scale-Dependent Wetting Behavior of Bioinspired Lubricants on Electrical Discharge Machined Ti6Al4V Surfaces. Tribol. Int. 2024, 194, 109562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittens, R.A.; Olivares-Navarrete, R.; Cheng, A.; Anderson, D.M.; McLachlan, T.; Stephan, I.; Geis-Gerstorfer, J.; Sandhage, K.H.; Fedorov, A.G.; Rupp, F.; et al. The Roles of Titanium Surface Micro/Nanotopography and Wettability on the Differential Response of Human Osteoblast Lineage Cells. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 6268–6277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittens, R.A.; Olivares-Navarrete, R.; McLachlan, T.; Cai, Y.; Hyzy, S.L.; Schneider, J.M.; Schwartz, Z.; Sandhage, K.H.; Boyan, B.D. Differential Responses of Osteoblast Lineage Cells to Nanotopographically-Modified, Microroughened Titanium–Aluminum–Vanadium Alloy Surfaces. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 8986–8994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittens, R.A.; McLachlan, T.; Olivares-Navarrete, R.; Cai, Y.; Berner, S.; Tannenbaum, R.; Schwartz, Z.; Sandhage, K.H.; Boyan, B.D. The Effects of Combined Micron-/Submicron-Scale Surface Roughness and Nanoscale Features on Cell Proliferation and Differentiation. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 3395–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Lin, L.; Yang, Y.; Hu, R.; Vogler, E.A.; Lin, C. Role of Trapped Air in the Formation of Cell-and-Protein Micropatterns on Superhydrophobic/Superhydrophilic Microtemplated Surfaces. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 8213–8220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Schwartz, Z.; Olivares-Navarrete, R.; Boyan, B.D.; Tannenbaum, R. Enhancement of Surface Wettability via the Modification of Microtextured Titanium Implant Surfaces with Polyelectrolytes. Langmuir 2011, 27, 5976–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viceconti, M.; Muccini, R.; Bernakiewicz, M.; Baleani, M.; Cristofolini, L. Large-sliding contact elements accurately predict levels of bone–implant micromotion relevant to osseointegration. J. Biomech. 2000, 33, 1611–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Noort, R. Titanium: The Implant Material of Today. J. Mater. Sci. 1987, 22, 3801–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallab, N.J.; Anderson, S.; Stafford, T.; Glant, T.; Jacobs, J.J. Lymphocyte Responses in Patients with Total Hip Arthroplasty. J. Orthop. Res. 2005, 23, 384391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaruma, L.G. Definitions in Biomaterials, D.F. Williams, Ed., Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1987, 72 pp. J. Polym. Sci. Part C Polym. Lett. 1988, 26, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, B.D. The Biocompatibility of Implant Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; ISBN 9780128005002. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.F. On the Mechanisms of Biocompatibility. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 2941–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivasagam, G.; Dhinasekaran, D.; Rajamanickam, A. Biomedical Implants: Corrosion and Its Prevention—A Review. Recent Pat. Corros. Science 2010, 2, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidrou, C.; Kapetanou, A.; Rizou, S. The Effect of Drugs on Implant Osseointegration—A Narrative Review. Injury 2023, 54, 110888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Chu, P.K. Orthopedic Implants. Encycl. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 1, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello-Machado, R.C.; Sartoretto, S.C.; Granjeiro, J.M.; Calasans-Maia, J.d.A.; de Uzeda, M.J.P.G.; Mourão, C.F.d.A.B.; Ghiraldini, B.; Bezerra, F.J.B.; Senna, P.M.; Calasans-Maia, M.D. Osseodensification Enables Bone Healing Chambers with Improved Low-Density Bone Site Primary Stability: An in Vivo Study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.B.; Burr, D.B. Structure, Function and Adaptation of Compact Bone. Skelet. Radiol. 1989, 18, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Srikanth, S.P.; Wu, Y.S.; Kalita, T.; Ambartsumov, T.G.; Tseng, W.; Kumar, A.P.; Ahmad, A.; Michalek, J.E. Different Types of Algae Beneficial for Bone Health in Animals and in Humans—A Review. Algal. Res. 2024, 82, 103593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakes, R.S.; Park, J. Biomaterials. An Introduction, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1993; ISBN 0-306-43992-1. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, Y.-C. Biomechanics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, D.; Martins-Cruz, C.; Oliveira, M.B.; Mano, J.F. Bone Physiology as Inspiration for Tissue Regenerative Therapies. Biomaterials 2018, 185, 240–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, F.S.; Hayes, W.C.; Keaveny, T.M.; Boskey, A.; Einhorn, T.A.; Iannotti, J.P. Form and Function of Bone. Orthop. Basic Sci. 1994, 4, 127–185. [Google Scholar]

- Boskey, A.L.; Coleman, R. Aging and Bone. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 89, 1333–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, I.S.; Preeth, D.R.; Vedhanayagam, M.; Hyon, S.H.; Lim, D.; Kim, B.; Rajalakshmi, S.; Han, D.W. Polyphenols-Loaded Electrospun Nanofibers in Bone Tissue Engineering and Regeneration. Biomater. Res. 2021, 25, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, T.J. Nanophase Ceramics: The Future Orthopedic and Dental Implant Material. Adv. Chem. Eng. 2001, 27, 125–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedenstein, A.J.; Chailakhyan, R.K.; Gerasimov, U.V. Bone Marrow Osteogenic Stem Cells: In Vitro Cultivation and Transplantation in Diffusion Chambers. Cell Prolif. 1987, 20, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, D.; Li, S.; Deng, Z.; Pan, Z.; Li, C.; Chen, T. The Effects of Graphene Oxide Doping on the Friction and Wear Properties of TiN Bioinert Ceramic Coatings Prepared Using Wide-Band Laser Cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 458, 129354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desante, G.; Labude, N.; Rütten, S.; Römer, S.; Kaufmann, R.; Zybała, R.; Jagiełło, J.; Lipińska, L.; Chlanda, A.; Telle, R.; et al. Graphene Oxide Nanofilm to Functionalize Bioinert High Strength Ceramics. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 566, 150670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Deng, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhu, X.; Xiong, Y. Bioinert TiC Ceramic Coating Prepared by Laser Cladding: Microstructures, Wear Resistance, and Cytocompatibility of the Coating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 423, 127635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohner, M. Bioresorbable Ceramics. In Degradation Rate of Bioresorbable Materials: Prediction and Evaluation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; pp. 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Raina, D.B.; Oberländer, J.T.; Liu, Y.; Goronzy, J.; Apolle, R.; Vater, C.; Richter, R.F.; Tägil, M.; Lidgren, L.; et al. Comparison of Immediate Anchoring Effectiveness of Two Different Techniques of Bioresorbable Ceramic Application for Pedicle Screw Augmentation. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 12877–12889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Aziz, A.; Sheng, X.; Wang, L.; Yin, L. Bioresorbable Neural Interfaces for Bioelectronic Medicine. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 32, 100565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehboob, H.; Chang, S.H. Application of Composites to Orthopedic Prostheses for Effective Bone Healing: A Review. Compos. Struct. 2014, 118, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.M.S.; Koolen, P.G.L.; Kim, K.; Perrone, G.S.; Kaplan, D.L.; Lin, S.J. Absorbable Biologically Based Internal Fixation. Clin. Podiatr. Med. Surg. 2015, 32, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Zeng, F.; Dunne, M.; Allen, C. Methoxy Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Block-Poly(δ-Valerolactone) Copolymer Micelles for Formulation of Hydrophobic Drugs. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 3119–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.C.; Kim, D.W.; Shim, Y.H.; Bang, J.S.; Oh, H.S.; Kim, S.W.; Seo, M.H. In Vivo Evaluation of Polymeric Micellar Paclitaxel Formulation: Toxicity and Efficacy. J. Control. Release 2001, 72, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lausmaa, J.; Kasemo, B.; Mattsson, H.; Odelius, H. Multi-Technique Surface Charaterization of Oxide Films on Electropolished and Anodically Oxidized Titanium. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1990, 45, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zhong, S.; Xi, T. In Vitro Corrosion and Biocompatibility of Binary Magnesium Alloys. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Li, Y.J.; Walmsley, J.C.; Dumoulin, S.; Skaret, P.C.; Roven, H.J. Microstructure Evolution of Commercial Pure Titanium during Equal Channel Angular Pressing. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barceloux, D.G.; Barceloux, D. Chromium. J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 1999, 37, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barceloux, D.G.; Barceloux, D. Nickel. J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 1999, 37, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gao, P.; Wan, P.; Pei, Y.; Shi, L.; Fan, B.; Shen, C.; Xiao, X.; Yang, K.; Guo, Z. Novel Bio-Functional Magnesium Coating on Porous Ti6Al4V Orthopaedic Implants: In Vitro and In Vivo Study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.; Chen, L.; Yin, M.; Xu, S.; Liang, Z. Review on Magnesium and Magnesium-Based Alloys as Biomaterials for Bone Immobilization. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 23, 4396–4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badkoobeh, F.; Mostaan, H.; Rafiei, M.; Bakhsheshi-Rad, H.R.; RamaKrishna, S.; Chen, X. Additive Manufacturing of Biodegradable Magnesium-Based Materials: Design Strategies, Properties, and Biomedical Applications. J. Magnes. Alloys 2023, 11, 801–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Shukla, R.; Kesavan, P.; Nilawar, S.; Perugu, C.; Sellamuthu, P.; Chatterjee, K.; Suwas, S.; Jayamani, J.; Prashanth, K. Microstructural, Mechanical, Corrosion, and Biological Behavior of Spark Plasma Sintered Commercially Pure Zinc for Biomedical Applications. Mater. Adv. 2025, 6, 3546–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy Jai Poinern, G.; Brundavanam, S.; Fawcett, D. Biomedical Magnesium Alloys: A Review of Material Properties, Surface Modifications and Potential as a Biodegradable Orthopaedic Implant. Am. J. Biomed. Eng. 2013, 2, 218–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, R.; Ramakrishna, S. Development of Nanocomposites for Bone Grafting. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2005, 65, 2385–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wu, G.; Jiang, J.; Wong, H.M.; Yeung, K.W.K.; Chu, P.K. Improved Corrosion Resistance and Cytocompatibility of Magnesium Alloy by Two-Stage Cooling in Thermal Treatment. Corros. Sci. 2012, 59, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, F.; Kaese, V.; Haferkamp, H.; Switzer, E.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; Wirth, C.J.; Windhagen, H. In Vivo Corrosion of Four Magnesium Alloys and the Associated Bone Response. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 3557–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghali, E. Corrosion Resistance of Aluminum and Magnesium Alloys: Understanding, Performance, and Testing. In Corrosion Resistance of Aluminum and Magnesium Alloys: Understanding, Performance, and Testing; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radha, R.; Sreekanth, D. Insight of Magnesium Alloys and Composites for Orthopedic Implant Applications—A Review. J. Magnes. Alloys 2017, 5, 286–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyens, C.; Peters, M. Titanium and Titanium Alloys: Fundamentals and Applications; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D.; Williams, J.C. Perspectives on Titanium Science and Technology. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 844–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Lee, P.D.; Dashwood, R.J.; Lindley, T.C. Titanium Foams for Biomedical Applications: A Review. Mater. Technol. 2010, 25, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Xu, W.; Brandt, M.; Tang, H.P. Additive Manufacturing and Postprocessing of Ti-6Al-4V for Superior Mechanical Properties. MRS Bull. 2016, 41, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, P. Handbook of Inorganic Chemicals; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 0070494398. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.W.; Jung, H.D.; Kang, M.H.; Kim, H.E.; Koh, Y.H.; Estrin, Y. Fabrication of Porous Titanium Scaffold with Controlled Porous Structure and Net-Shape Using Magnesium as Spacer. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 2808–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esen, Z.; Bor, Ş. Processing of Titanium Foams Using Magnesium Spacer Particles. Scr. Mater. 2007, 56, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lu, Z.; Jia, L.; Li, F. Preparation and Properties of Low Cost Porous Titanium by Using Rice Husk as Hold Space. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2017, 27, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.S.; Lu, Z.L.; Jia, L.; Chen, J.X. Preparation of Porous Titanium Materials by Powder Sintering Process and Use of Space Holder Technique. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2017, 24, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, X.; Yongning, L.; Yong, L.; Guibao, Q.; Jinming, L. The Application of Model Equation Method in Preparation of Titanium Foams. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 13, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcellos, L.M.R.D.; Oliveira, M.V.D.; Graça, M.L.D.A.; Vasconcellos, L.G.O.D.; Carvalho, Y.R.; Cairo, C.A.A. Porous Titanium Scaffolds Produced by Powder Metallurgy for Biomedical Applications. Mater. Res. 2008, 11, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, W.; Bai, C.; Qiu, G.B.; Wang, Q. Processing and Properties of Porous Titanium Using Space Holder Technique. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2009, 506, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.S.; Zhang, Y.P.; Ma, X.; Zhang, X.P. Space-Holder Engineered Porous NiTi Shape Memory Alloys with Improved Pore Characteristics and Mechanical Properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 474, L1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Y.; Tang, H. Preparation and Compressive Behavior of Porous Titanium Prepared by Space Holder Sintering Process. Procedia Eng. 2012, 27, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, Y.; Pavón, J.J.; Rodríguez, J.A. Processing and Characterization of Porous Titanium for Implants by Using NaCl as Space Holder. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2012, 212, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Kent, D.; Bermingham, M.; Dehghan-Manshadi, A.; Dargusch, M. Manufacturing of Biocompatible Porous Titanium Scaffolds Using a Novel Spherical Sugar Pellet Space Holder. Mater. Lett. 2017, 195, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.Q.; Wang, C.Y.; Lu, X. Effect of Pore Structure on the Compressive Property of Porous Ti Produced by Powder Metallurgy Technique. Mater. Des. 2013, 50, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, Q.; Xu, M.; Jiang, G.; Zhang, Y.; He, G. A Novel Approach to Fabrication of Three-Dimensional Porous Titanium with Controllable Structure. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 71, 1046–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Frith, J.E.; Dehghan-Manshadi, A.; Attar, H.; Kent, D.; Soro, N.D.M.; Bermingham, M.J.; Dargusch, M.S. Mechanical Properties and Biocompatibility of Porous Titanium Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 75, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Zhang, E.; Li, M.; Zeng, S. Preparation, Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Porous Titanium Sintered by Ti Fibres. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2008, 19, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, F.I.; Trapani, V. Cell (Patho)Physiology of Magnesium. Clin. Sci. 2008, 114, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, M.E.; Cowan, J.A. Magnesium Chemistry and Biochemistry. BioMetals 2002, 15, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vormann, J. Magnesium: Nutrition and Metabolism. Mol. Aspects Med. 2003, 24, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatman, P.W. Magnesium Transport across Cell Membranes. J. Membr. Biol. 1984, 80, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cachinho, S.C.P.; Correia, R.N. Titanium Scaffolds for Osteointegration: Mechanical, in Vitro and Corrosion Behaviour. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2008, 19, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karageorgiou, V.; Kaplan, D. Porosity of 3D Biomaterial Scaffolds and Osteogenesis. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 5474–5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrabés, M.; Sevilla, P.; Planell, J.A.; Gil, F.J. Mechanical Properties of Nickel–Titanium Foams for Reconstructive Orthopaedics. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2008, 28, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.P.; Li, S.H.; De Groot, K.; Layrolle, P. Preparation and Characterization of Porous Titanium. Key Eng. Mater. 2002, 218, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, H.; Zhu, X.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, X. An Improved Polymeric Sponge Replication Method for Biomedical Porous Titanium Scaffolds. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 70, 1192–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Liu, P.; Tan, Q. Porous Titanium Materials with Entangled Wire Structure for Load-Bearing Biomedical Applications. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2012, 5, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; He, G. Enhancement of the Porous Titanium with Entangled Wire Structure for Load-Bearing Biomedical Applications. Mater. Des. 2014, 56, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Liu, P.; Du, C.; Wu, L.; He, G. Mechanical Behaviors of Quasi-Ordered Entangled Aluminum Alloy Wire Material. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2009, 527, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Tan, Q.; Wu, L.; He, G. Compressive and Pseudo-Elastic Hysteresis Behavior of Entangled Titanium Wire Materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 3301–3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Wang, C.; Li, Q.; Dong, J.; He, G. Porous Titanium with Entangled Structure Filled with Biodegradable Magnesium for Potential Biomedical Applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 47, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Jiang, G.; He, G. Enhancement of Entangled Porous Titanium by BisGMA for Load-Bearing Biomedical Applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 61, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, G.; Liu, P.; Tan, Q.; Jiang, G. Flexural and Compressive Mechanical Behaviors of the Porous Titanium Materials with Entangled Wire Structure at Different Sintering Conditions for Load-Bearing Biomedical Applications. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2013, 28, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asaoka, K.; Kuwayama, N.; Okuno, O.; Miura, I. Mechanical Properties and Biomechanical Compatibility of Porous Titanium for Dental Implants. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1985, 19, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivasishin, O.M.; Savvakin, D.G. The Impact of Diffusion on Synthesis of High-Strength Titanium Alloys from Elemental Powder Blends. Key Eng. Mater. 2010, 436, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.F.; Luo, S.D.; Schaffer, G.B.; Qian, M. Sintering of Ti–10V–2Fe–3Al and Mechanical Properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 528, 6719–6726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamedov, V. Spark Plasma Sintering as Advanced PM Sintering Method. Powder Metall. 2002, 45, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Ohashi, O.; Chiba, K.; Yamaguchi, N.; Song, M.; Furuya, K.; Noda, T. Frequency Effect on Pulse Electric Current Sintering Process of Pure Aluminum Powder. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2003, 359, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Ohashi, O.; Wada, K.; Ogawa, T.; Song, M.; Furuya, K. Interface Microstructure of Aluminum Die-Casting Alloy Joints Bonded by Pulse Electric-Current Bonding Process. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 428, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.W.; Chen, L.D.; Kang, Y.S.; Niino, M.; Hirai, T. Effect of Plasma Activated Sintering (PAS) Parameters on Densification of Copper Powder. Mater. Res. Bull. 2000, 35, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.F.; Qian, M. Spark Plasma Sintering and Hot Pressing of Titanium and Titanium Alloys. In Titanium Powder Metallurgy: Science, Technology and Applications; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omori, M. Sintering, Consolidation, Reaction and Crystal Growth by the Spark Plasma System (SPS). Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2000, 287, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groza, J.R.; Zavaliangos, A. Sintering Activation by External Electrical Field. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2000, 287, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Shen, Z.; Nygren, M. Fast Densification and Deformation of Titanium Powder. Powder Metall. 2013, 48, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Li, H.; Bünger, M.; Egund, N.; Lind, M.; Bünger, C. Bone Ingrowth Characteristics of Porous Tantalum and Carbon Fiber Interbody Devices: An Experimental Study in Pigs. Spine J. 2004, 4, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.; Groza, J.R.; Yamazaki, K.; Shoda, K. Plasma Activated Sintering (PAS) of Tungsten Powders. Mater. Manuf. Process 1994, 9, 1105–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifland, M.I.; Okazaki, K. Properties of Titanium Dental Implants Produced by Electro-Discharge Compaction. Clin. Mater. 1994, 17, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fambri, L. Book Review: Biomaterials. An Introduction, Second Edition Edited by J. B. Park and R. S. Lakes Plenum Press, New York, 1992 ISBN 0-306-43992-1, 394 pp. J. Bioact. Compat. Polym. 1993, 8, 289–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, D.; Sellamuthu, P.; Prashanth, K.G. Vacuum Hot Pressing of Oxide Dispersion Strengthened Ferritic Stainless Steels: Effect of al Addition on the Microstructure and Properties. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2020, 4, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Zhang, F.; Otterstein, E.; Burkel, E. Processing of Porous Ti and Ti5Mn Foams by Spark Plasma Sintering. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashimbetova, A.; Slámecka, K.; Díaz-De-La-Torre, S.; Méndez-García, J.C.; Hernández-Morales, B.; Piña-Barba, M.C.; Hui, D.; Celko, L.; Montufar, E.B. Pressure-Less Spark Plasma Sintering of 3D-Plotted Titanium Porous Structures. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 22, 2147–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.D.; Qian, M.; Ashraf Imam, M. Microwave Sintering of Titanium and Titanium Alloys. In Titanium Powder Metallurgy: Science, Technology and Applications; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.Y.; Wong, C.T.; Zhang, L.N.; Choy, M.T.; Chow, T.W.; Chan, K.C.; Yue, T.M.; Chen, Q. In Situ Formation of Ti Alloy/TiC Porous Composites by Rapid Microwave Sintering of Ti6Al4V/MWCNTs Powder. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 557, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ruiz, R.; Romanos, G. Potential Causes of Titanium Particle and Ion Release in Implant Dentistry: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Otterstein, E.; Burkel, E. Spark Plasma Sintering, Microstructures, and Mechanical Properties of Macroporous Titanium Foams. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2010, 12, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Pilz, S.; Lindemann, I.; Damm, C.; Hufenbach, J.; Helth, A.; Geissler, D.; Henss, A.; Rohnke, M.; Calin, M.; et al. Powder Metallurgical Processing of Low Modulus β-Type Ti-45Nb to Bulk and Macro-Porous Compacts. Powder Technol. 2017, 322, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kon, M.; Hirakata, L.M.; Asaoka, K. Porous Ti-6Al-4V Alloy Fabricated by Spark Plasma Sintering for Biomimetic Surface Modification. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2004, 68, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertorer, O.; Topping, T.D.; Li, Y.; Moss, W.; Lavernia, E.J. Nanostructured Ti Consolidated via Spark Plasma Sintering. Metall. Mater. Trans. A Phys. Metall. Mater. Sci. 2011, 42, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadra, M.; Casari, F.; Girardini, L.; Molinari, A. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Cp-Titanium Produced by Spark Plasma Sintering. Powder Metall. 2008, 51, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashanth, K.G.; Wang, Z. Additive Manufacturing: Alloy Design and Process Innovations. Materials 2020, 13, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaprasad, K.; Babu, N.R.; Prashanth, K.G. Additive Manufacturing and Allied Technologies. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2023, 76, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, H.S.; Vikram, R.J.; Kosiba, K.; Juhani, K.; Sergejev, F.; Suwas, S.; Prashanth, K.G. Additive Manufacturing of CMCs with Bimodal Microstructure. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 938, 168416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, H.S.; Kosiba, K.; Juhani, K.; Sergejev, F.; Prashanth, K.G. Effect of Powder Bed Preheating on the Crack Formation and Microstructure in Ceramic Matrix Composites Fabricated by Laser Powder-Bed Fusion Process. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 58, 103013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, H.S.; Jayaraj, J.; Vikram, R.J.; Juhani, K.; Sergejev, F.; Prashanth, K.G. Additive Manufacturing of TiC-Based Cermets: A Detailed Comparison with Spark Plasma Sintered Samples. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 960, 170436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, H.S.; Marczyk, J.; Juhani, K.; Sergejev, F.; Kumar, R.; Hussain, A.; Akhtar, F.; Hebda, M.; Prashanth, K.G. Binder Jetting 3D Printing of Green TiC-FeCr Based Cermets—Effect of Sintering Temperature and Systematic Comparison Study with Laser Powder Bed Fusion Fabricated Parts. Mater. Today Adv. 2025, 25, 100562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, T.J.; Harrysson, O.L. Overview of Current Additive Manufacturing Technologies and Selected Applications. Sci. Prog. 2012, 95, 255–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S.; Ong, K.; Lau, E.; Mowat, F.; Halpern, M. Projections of Primary and Revision Hip and Knee Arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2007, 89, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashanth, K.; Löber, L.; Klauss, H.-J.; Kühn, U.; Eckert, J. Characterization of 316L Steel Cellular Dodecahedron Structures Produced by Selective Laser Melting. Technologies 2016, 4, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, J.; Muthukannan, D.; Shukla, R.; Konda Gokuldoss, P. Manufacturability and Deformation Studies on a Novel Metallic Lattice Structure Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting. Vacuum 2024, 222, 113065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadeesh, B.; Duraiselvam, M.; Prashanth, K.G. Deformation Behavior of Metallic Lattice Structures with Symmetrical Gradients of Porosity Manufactured by Metal Additive Manufacturing. Vacuum 2023, 211, 111955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Huang, J.; Lei, Y.; O’Reilly, P.; Ahmed, M.; Zhang, C.; Yan, X.; Yin, S. Microstructural Features and Compressive Properties of SLM Ti6Al4V Lattice Structures. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 403, 126419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokuldoss, P.K.; Kolla, S.; Eckert, J. Additive Manufacturing Processes: Selective Laser Melting, Electron Beam Melting and Binder Jetting—Selection Guidelines. Materials 2017, 10, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Hameed, P.; Ummethala, R.; Manivasagam, G.; Prashanth, K.G.; Eckert, J. Selective Laser Manufacturing of Ti-Based Alloys and Composites: Impact of Process Parameters, Application Trends, and Future Prospects. Mater. Today Adv. 2020, 8, 100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, D.G. Directed Energy Deposition (DED) Process: State of the Art. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. Green Technol. 2021, 8, 703–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudino, S.; Unterdörfer, C.; Prashanth, K.G.; Attar, H.; Ellendt, N.; Uhlenwinkel, V.; Eckert, J. Additive Manufacturing of Cu-10Sn Bronze. Mater. Lett. 2015, 156, 202–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryawanshi, J.; Prashanth, K.G.; Ramamurty, U. Mechanical Behavior of Selective Laser Melted 316L Stainless Steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 696, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryawanshi, J.; Prashanth, K.G.; Scudino, S.; Eckert, J.; Prakash, O.; Ramamurty, U. Simultaneous Enhancements of Strength and Toughness in an Al-12Si Alloy Synthesized Using Selective Laser Melting. Acta Mater. 2016, 115, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DebRoy, T.; Wei, H.L.; Zuback, J.S.; Mukherjee, T.; Elmer, J.W.; Milewski, J.O.; Beese, A.M.; Wilson-Heid, A.; De, A.; Zhang, W. Additive Manufacturing of Metallic Components—Process, Structure and Properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 92, 112–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, J.; Zhao, C.; Prashanth, K.G. Massive Transformation in Dual-Laser Powder Bed Fusion of Ti6Al4V Alloys. J. Manuf. Process 2024, 119, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, J.; Antonov, M.; Kollo, L.; Prashanth, K.G. Role of Laser Remelting and Heat Treatment in Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Selective Laser Melted Ti6Al4V Alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 897, 163207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Chi, H.; Li, P.; Guo, B.; Yu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Liang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Ren, L. Interpenetrating Phases Composites Ti6Al4V/Zn as Partially Degradable Biomaterials to Improve Bone-Implant Properties. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 93, 104411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Shin, Y.C. Additive Manufacturing of Ti6Al4V Alloy: A Review. Mater. Des. 2019, 164, 107552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocki, B.; Maj, P.; Sitek, R.; Buhagiar, J.; Kurzydłowski, K.J.; Świeszkowski, W. Laser and Electron Beam Additive Manufacturing Methods of Fabricating Titanium Bone Implants. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabban, R.; Bahl, S.; Chatterjee, K.; Suwas, S. Globularization Using Heat Treatment in Additively Manufactured Ti-6Al-4V for High Strength and Toughness. Acta Mater. 2019, 162, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.K.; Shahidsha, N.; Bahl, S.; Kedaria, D.; Singamneni, S.; Yarlagadda, P.K.D.V.; Suwas, S.; Chatterjee, K. Enhanced Biomechanical Performance of Additively Manufactured Ti-6Al-4V Bone Plates. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 119, 104552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, J.; Suryanarayana, C.; Okulov, I.; Prashanth, K.G. Selective Laser Melting of Ti6Al4V: Effect of Laser Re-Melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 805, 140558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, N.; Chaudhary, A.; Nandwana, P.; Babu, S.S. Texture Evolution During Laser Direct Metal Deposition of Ti-6Al-4V. Jom 2016, 68, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Brandt, M.; Sun, S.; Elambasseril, J.; Liu, Q.; Latham, K.; Xia, K.; Qian, M. Additive Manufacturing of Strong and Ductile Ti–6Al–4V by Selective Laser Melting via in Situ Martensite Decomposition. Acta Mater. 2015, 85, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, S.; Yadav, M.K.; Jayaraj, J.; Yangyang, F.; Xi, L.; Prashanth, K.G. Microstructural Homogenization through Laser Remelting in an Additively Manufactured Ti–40Nb Sample from Elemental Feedstock Powders. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 38, 4305–4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharin, H.A.; Rani, A.M.A.; Azam, F.I.; Ginta, T.L.; Sallih, N.; Ahmad, A.; Yunus, N.A.; Zulkifli, T.Z.A. Effect of Unit Cell Type and Pore Size on Porosity and Mechanical Behavior of Additively Manufactured Ti6Al4V Scaffolds. Materials 2018, 11, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xie, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, C.; Kollo, L.; Eckert, J.; Prashanth, K.G. Premature Failure of an Additively Manufactured Material. NPG Asia Mater. 2020, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Fang, G.; Zhou, J. Additively Manufactured Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering and the Prediction of Their Mechanical Behavior: A Review. Materials 2017, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanghai Cooyer New Material Co., L. Medical Titanium Alloy Anticorrosive Material. Available online: https://www.openpr.com/news/1188745/hip-replacement-implants-market-opportunity-2018-2025-by-top-key-players-zimmer-biomet-depuy-synthes-stryker-smith-and-nephew-b-braun-melsungen-ag-corin-arthrex-inc-evolutis.html (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Technology Predictions 2022; 3D Printing in Healthcare. Available online: https://futuredirections.ieee.org/2022/01/27/technology-predictions-2022-3d-printing-in-healthcare/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Metal AM, F.M. 3D Printing/A.M. Celebrating Ten Years of Metal Additively Manufactured Hip Cups. Available online: https://www.metal-am.com/celebrating-ten-years-of-metal-additively-manufactured-hip-cups/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Fang, C.; Cai, H.; Kuong, E.; Chui, E.; Siu, Y.C.; Ji, T.; Drstvenšek, I. Surgical Applications of Three-Dimensional Printing in the Pelvis and Acetabulum: From Models and Tools to Implants. Unfallchirurg 2019, 122, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Babazadeh-Naseri, A.; Dunbar, N.J.; Brake, M.R.W.; Zandiyeh, P.; Li, G.; Leardini, A.; Spazzoli, B.; Fregly, B.J. Finite Element Analysis of Screw Fixation Durability under Multiple Boundary and Loading Conditions for a Custom Pelvic Implant. Med. Eng. Phys. 2023, 111, 103930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, K.C.; Kumta, S.M.; Gee, N.V.L.; Demol, J. One-Step Reconstruction with a 3D-Printed, Biomechanically Evaluated Custom Implant after Complex Pelvic Tumor Resection. Comput. Aided Surg. 2015, 20, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broekhuis, D.; Boyle, R.; Karunaratne, S.; Chua, A.; Stalley, P. Custom Designed and 3D-Printed Titanium Pelvic Implants for Acetabular Reconstruction after Tumour Resection. HIP Int. 2023, 33, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, D.A.; Von Walter, M.; Wirtz, T.; Sellei, R.; Schmidt-Rohlfing, B.; Paar, O.; Erli, H.J. Structural, Mechanical and in Vitro Characterization of Individually Structured Ti-6Al-4V Produced by Direct Laser Forming. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y.; Wirtz, T.; LaMarca, F.; Hollister, S.J. Structural and Mechanical Evaluations of a Topology Optimized Titanium Interbody Fusion Cage Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting Process. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2007, 83, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATEC’s IdentiTiTM-PC ATEC’s IdentiTi Posterior Curved Porous Ti Interbody Implants. Available online: https://www.londonspine.com/instrumented-lumbar-fusion-for-degenerative-spondylolisthesis/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Laura Griffiths Stroke Patient Gets Life Back with 3D Printed Cranial Implant from EOS. Available online: https://www.protolabs.com/en-gb/resources/blog/3d-printing-and-customised-medical-implants/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Murr, L.E. Open-Cellular Metal Implant Design and Fabrication for Biomechanical Compatibility with Bone Using Electron Beam Melting. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 76, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoli, A.; Germani, M.; Raffaeli, R. Direct Fabrication through Electron Beam Melting Technology of Custom Cranial Implants Designed in a PHANToM-Based Haptic Environment. Mater. Des. 2009, 30, 3186–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, K.; Bai, X. Research on Impact Resistance of 3D Printing Titanium Alloy Personalized Cranial Prosthesis. J. Integr. Technol. 2022, 11, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Luo, D.; Huang, H.; Li, R.; Yu, N.; Liu, C.; Hu, M.; Rong, Q. Electron Beam Melting in the Fabrication of Three-Dimensional Mesh Titanium Mandibular Prosthesis Scaffold. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiduddin, K.; Mian, S.H.; Umer, U.; Ahmed, N.; Alkhalefah, H.; Ameen, W. Reconstruction of Complex Zygomatic Bone Defects Using Mirroring Coupled with EBM Fabrication of Titanium Implant. Metals 2019, 9, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yánez, A.; Cuadrado, A.; Martel, O.; Afonso, H.; Monopoli, D. Gyroid Porous Titanium Structures: A Versatile Solution to Be Used as Scaffolds in Bone Defect Reconstruction. Mater. Des. 2018, 140, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, A.W.; Mali, H.S.; Meena, A.; Saxena, K.K.; Ahmad, S.; Agrawal, M.K.; Sagbas, B.; Valerga Puerta, A.P.; Khan, M.I. A Comprehensive Review on Surface Post-Treatments for Freeform Surfaces of Bio-Implants. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 23, 4866–4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, E.; Bagherifard, S.; Bandini, M.; Guagliano, M. Surface Post-Treatments for Metal Additive Manufacturing: Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 37, 101619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, A.W.; Mali, H.S.; Meena, A. A Comprehensive Review on Surface Quality Improvement Methods for Additively Manufactured Parts. Rapid. Prototyp. J. 2023, 29, 504–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mruthunjaya, M.; Yogesha, K.B. A Review on Conventional and Thermal Assisted Machining of Titanium Based Alloy. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 8466–8472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Kibria, G.; Doloi, B.; Bhattacharyya Editors, B. Materials Forming, Machining and Tribology Advances in Abrasive Based Machining and Finishing Processes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Acharya, S.; Panicker, A.G.; Gopal, V.; Dabas, S.S.; Manivasagam, G.; Suwas, S.; Chatterjee, K. Surface Mechanical Attrition Treatment of Low Modulus Ti-Nb-Ta-O Alloy for Orthopedic Applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 110, 110729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S.; Suwas, S.; Chatterjee, K. Review of Recent Developments in Surface Nanocrystallization of Metallic Biomaterials. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 2286–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Wang, H.L.; Li, S.J.; Wang, S.G.; Wang, W.J.; Hou, W.T.; Hao, Y.L.; Yang, R.; Zhang, L.C. Compressive and Fatigue Behavior of Beta-Type Titanium Porous Structures Fabricated by Electron Beam Melting. Acta Mater. 2017, 126, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadpoor, A.A. Mechanical Performance of Additively Manufactured Meta-Biomaterials. Acta Biomater. 2019, 85, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Q.; Yang, W.; Hu, Y.; Shen, X.; Yu, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Cai, K. Osteogenesis of 3D Printed Porous Ti6Al4V Implants with Different Pore Sizes. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 84, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panzavolta, S.; Torricelli, P.; Amadori, S.; Parrilli, A.; Rubini, K.; Della Bella, E.; Fini, M.; Bigi, A. 3D Interconnected Porous Biomimetic Scaffolds: In Vitro Cell Response. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2013, 101, 3560–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, C.; Zhang, M.; Ren, D.; Ji, H.; Yi, Z.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Bi-Continuous Mg-Ti Interpenetrating-Phase Composite as a Partially Degradable and Bioactive Implant Material. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 146, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jahr, H.; Lietaert, K.; Pavanram, P.; Yilmaz, A.; Fockaert, L.I.; Leeflang, M.A.; Pouran, B.; Gonzalez-Garcia, Y.; Weinans, H.; et al. Additively Manufactured Biodegradable Porous Iron. Acta Biomater. 2018, 77, 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.Z.; Yu, J.; Liu, X.F.; Zhang, H.J.; Zhang, D.W.; Yin, Y.X.; Wang, L.N. Effects of Ag, Cu or Ca Addition on Microstructure and Comprehensive Properties of Biodegradable Zn-0.8Mn Alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 99, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, H.R.B.; Idris, M.H.; Kadir, M.R.A.; Farahany, S. Microstructure Analysis and Corrosion Behavior of Biodegradable Mg–Ca Implant Alloys. Mater. Des. 2012, 33, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.K.; Shukla, R.; Xi, L.; Wang, Z.; Prashanth, K.G. Metallic Multimaterials Fabricated by Combining Additive Manufacturing and Powder Metallurgy. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, R.; Yadav, M.K.; Madruga, L.Y.C.; Jayaraj, J.; Popat, K.; Wang, Z.; Xi, L.; Prashanth, K.G. A Novel Ti-Eggshell-Based Composite Fabricated by Combined Additive Manufacturing-Powder Metallurgical Routes as Bioimplants. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 6281–6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhao, N.; Yu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Qu, R.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Ren, D.; Berto, F.; Zhang, Z.; et al. On the Damage Tolerance of 3-D Printed Mg-Ti Interpenetrating-Phase Composites with Bioinspired Architectures. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | ρ | E | YS | UTS | UCS | FS | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Bone | |||||||

| Cortical bone | 1.8–2.0 | 7–30 | - | 164–240 | 100–230 | 27–35 | [68] |

| Cancellous bone | 1.0–1.4 | 0.01–3.0 | - | - | 2–12 | - | |

| Metals and Alloys | |||||||

| Ti-6Al-4V (cast) | 4.43 | 114 | 760–880 | 895–930 | - | 600–700 | [68] |

| Ti-6Al-4V (wrought) | 4.43 | 114 | 827–1103 | 860–965 | 896–1172 | 500–800 | |

| Ti-6Al-7Nb | 4.52 | 105 | 880 | 900 | - | - | [15] |

| SS316L | 8.0 | 193 | 170–310 | 540–1000 | 480–620 | 240–480 | [68] |

| Fe20Mn | 7.73 | 207 | 420 | 700 | - | - | [69] |

| Zn-Al-Cu | 5.79 | 90 | 171 | 210 | - | - | [34] |

| Co-Cr-Mo | 8.3 | 240 | 500–1500 | 900–1540 | - | 500–900 | |

| CoCr20Ni15Mo7 | 7.8 | 195–230 | 240–450 | 450–960 | - | - | |

| Pure Mg (cast) | 1.74 | 41 | 21 | 87 | 40 | - | |

| Pure Mg (wrought) | 1.74 | 41 | 100 | 180 | 100–140 | - | |

| AZ31 (Mg-based alloy) | 1.78 | 45 | 185 | 263 | - | - | |

| AZ91 (Mg-based alloy) | 1.81 | 45 | 160 | 150 | - | - | |

| Ceramics | |||||||

| Alumina Ceramics | 4 | 260–410 | - | 400–580 | - | - | [34] |

| Synthetic hydroxyapatite | 3.15 | 6–102 | - | - | 0.22–4.1 | - | [18,70] |

| Zirconia | 3.98 | 210 | - | 800–1500 | 1990 | - | [71] |

| Polymers | |||||||

| PLGA | 1.2–1.3 | 1.69 | 3.8–26.6 | 13.9–16.7 | - | - | [34] |

| PCL | 1.15 | 281–686 | 8.37–14.66 | 68–103 | - | - | |

| PLA | 1.8 | 3750 | 70 | 59 | - | - | |

| Material | Standard | E | UTS | Alloy Composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-generation biomaterials (1950–1990) | ||||

| Commercially pure Ti (CP grade 1–4) | ASTM F1341 | 100 | 240–550 | α |

| Ti–6Al–4V ELI wrought | ASTM F136 | 110 | 860–965 | α + β |

| Ti–6Al–4V ELI standard grade | ASTM F1472 | 112 | 895–930 | α + β |

| Ti–6Al–7Nb wrought | ASTM F1295 | 110 | 900–1050 | α + β |

| Ti–5Al–2.5Fe | - | 110 | 1020 | α + β |

| Second-generation biomaterials (1990–to date) | ||||

| Ti–13Nb–13Zr wrought | ASTM F1713 | 79–84 | 973–1037 | Metastable β |

| Ti–12Mo–6Zr–2Fe (TMZF) | ASTM F1813 | 74–85 | 1060–1100 | β |

| Ti–35Nb–7Zr–5Ta (TNZT) | - | 55 | 596 | β |

| Ti–29Nb–13Ta–4.6Zr | - | 65 | 911 | β |

| Ti–35Nb–5Ta–7Zr–0.40 (TNZTO) | - | 66 | 1010 | β |

| Ti–15Mo–5Zr–3Al | - | 22 | - | β |

| Ti–Mo | ASTM F2066 | - | - | β |

| Space Holder Material | P | PS | E | YS | UTS | UCS | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mo Wire | 32–47 | - | 23–62 | 76–192 | - | - | [175] |

| Mg | 45–70 | 525 | 0.42–8.8 | 15–116 | - | - | [164] |

| Mg | 50–71 | 262–132 | - | - | - | 59–280 | [163] |

| Mg | 30–50 | - | 15–44 | 117–222 | - | - | [176] |

| Ti Fibers | 35–84 | 150–600 | 2–4 | - | 200–600 | - | [177] |

| Rice Husk | 50–60 | 100–550 | - | - | - | 17–70 | [165] |

| Rice Husk | 25–36 | - | - | - | - | 440–938 | [166] |

| Rice Husk | 15–34 | - | 6–15 | - | - | 116–396 | [16] |

| Sucrose | 20–54 | 212–500 | 12–50 | - | - | - | [173] |

| Urea | 36 | 480 | - | - | - | - | [168] |

| Urea | 55–75 | 200–500 | 3–6 | - | 10–35 | - | [169] |

| Method | Material Used | P | PS | E | YS | UTS | UCS | FS | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EWMT | Entangled Mo Wire | 32–47 | 0.4 | 23–62 | 76–192 | - | - | - | [175] |

| EWMT | Ti Wire | 35–84 | 150–600 | 2–4.2 | - | 200–600 | - | - | [177] |

| EWMT | Entangled Ti Wires | 44–81 | NR | 0.03–2.25 | - | - | - | 9–325 | [193] |

| EWMT | Entangled Ti Wire | 53–55 | NR | 0.03–1 | 3–3.5 | - | - | - | [188] |

| EWMT | Entangled Ti Wire | 37–54 | NR | 22–47 | - | - | 175–246 | - | [191] |

| EWMT | Entangled Ti Wire | 40–55 | 100–400 | 0.4–1.4 | 12.9–52.5 | - | - | - | [192] |

| EWMT | Entangled Ti Wire | 45–58 | 50–200 | 1.05–0.33 | 75–124 | 48–108 | - | - | [187] |

| EMWT | Normally entangled Ti Wire | 48–73 | - | 0.13–0.82 | 2–31 | - | - | - | [190] |

| Coiled entangled Ti Wire | 48–78 | - | 0.04–0.62 | 1–19 | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yadav, M.K.; Yarlapati, A.; Aditya, Y.N.; Kesavan, P.; Pandey, V.; Perugu, C.S.; Nain, A.; Chatterjee, K.; Suwas, S.; Jayamani, J.; et al. Processing and Development of Porous Titanium for Biomedical Applications: A Comprehensive Review. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 401. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120401

Yadav MK, Yarlapati A, Aditya YN, Kesavan P, Pandey V, Perugu CS, Nain A, Chatterjee K, Suwas S, Jayamani J, et al. Processing and Development of Porous Titanium for Biomedical Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2025; 9(12):401. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120401

Chicago/Turabian StyleYadav, Mayank Kumar, Akshay Yarlapati, Yarlapati Naga Aditya, Praveenkumar Kesavan, Vaibhav Pandey, Chandra Shekhar Perugu, Amit Nain, Kaushik Chatterjee, Satyam Suwas, Jayaraj Jayamani, and et al. 2025. "Processing and Development of Porous Titanium for Biomedical Applications: A Comprehensive Review" Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 9, no. 12: 401. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120401

APA StyleYadav, M. K., Yarlapati, A., Aditya, Y. N., Kesavan, P., Pandey, V., Perugu, C. S., Nain, A., Chatterjee, K., Suwas, S., Jayamani, J., & Konda Gokuldoss, P. (2025). Processing and Development of Porous Titanium for Biomedical Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 9(12), 401. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120401