Evolution of Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of Laser-Welded Maraging Steel for Aerospace Applications: The Past, Present, and Future Prospect

Abstract

1. Introduction

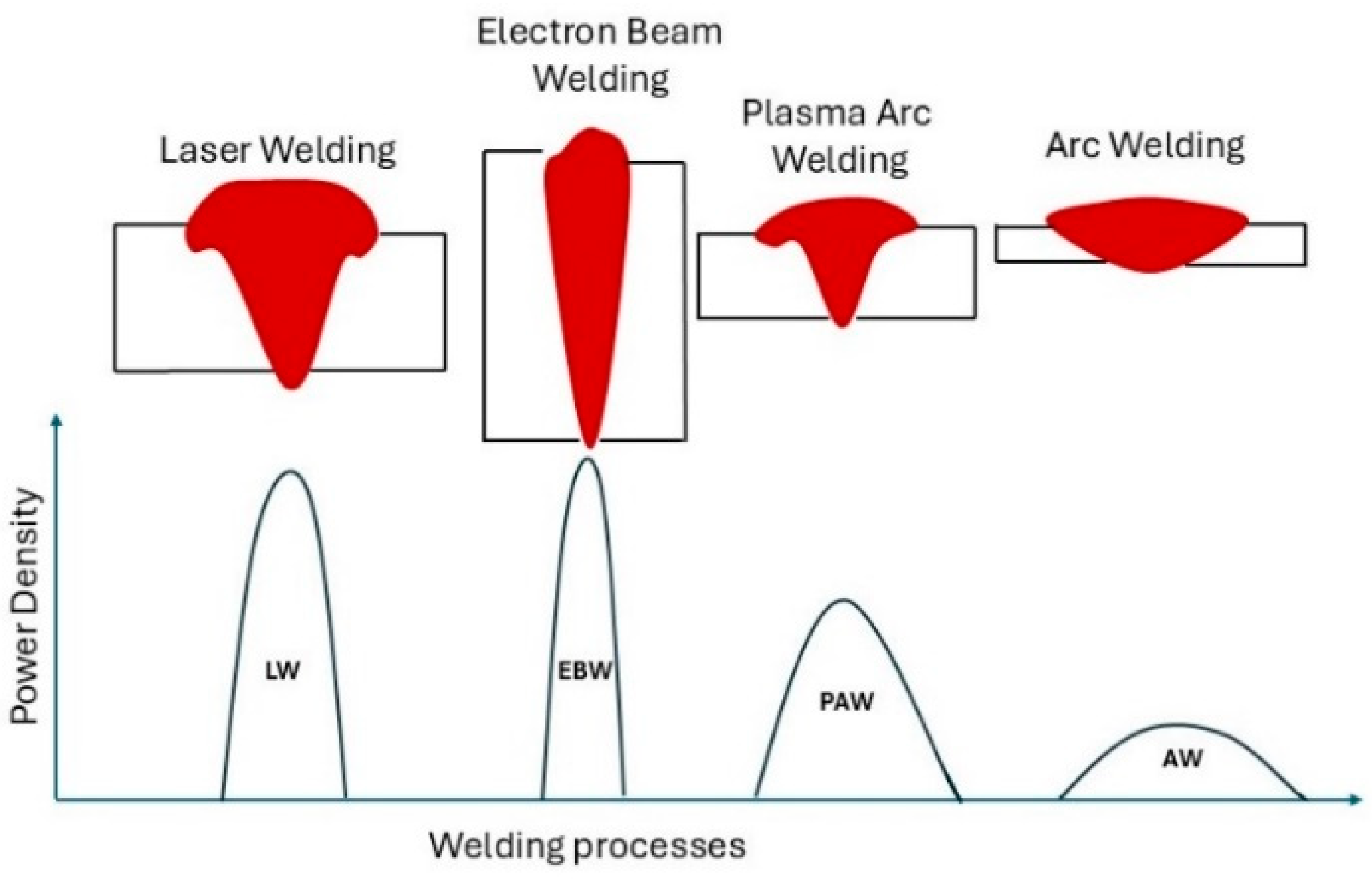

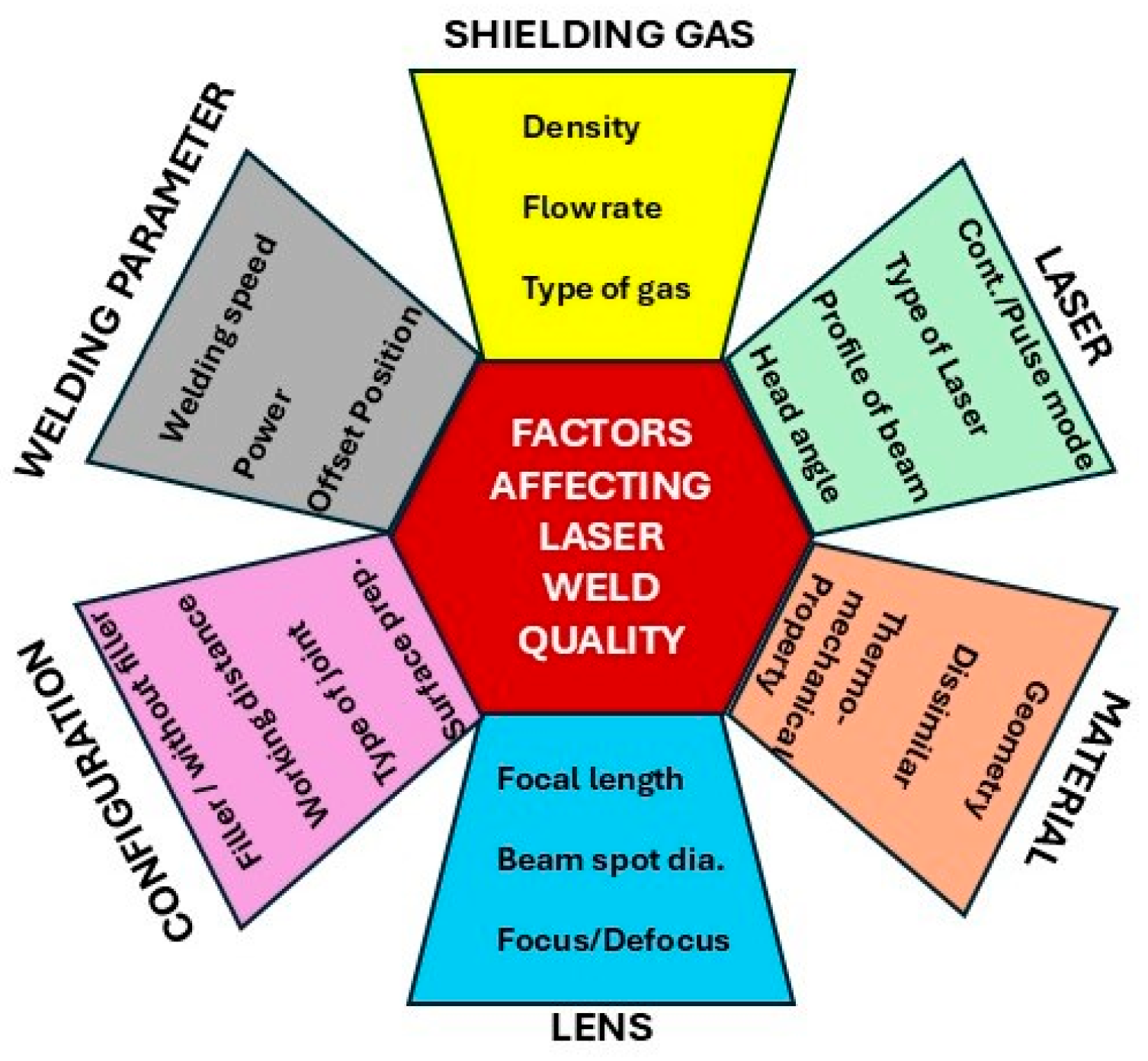

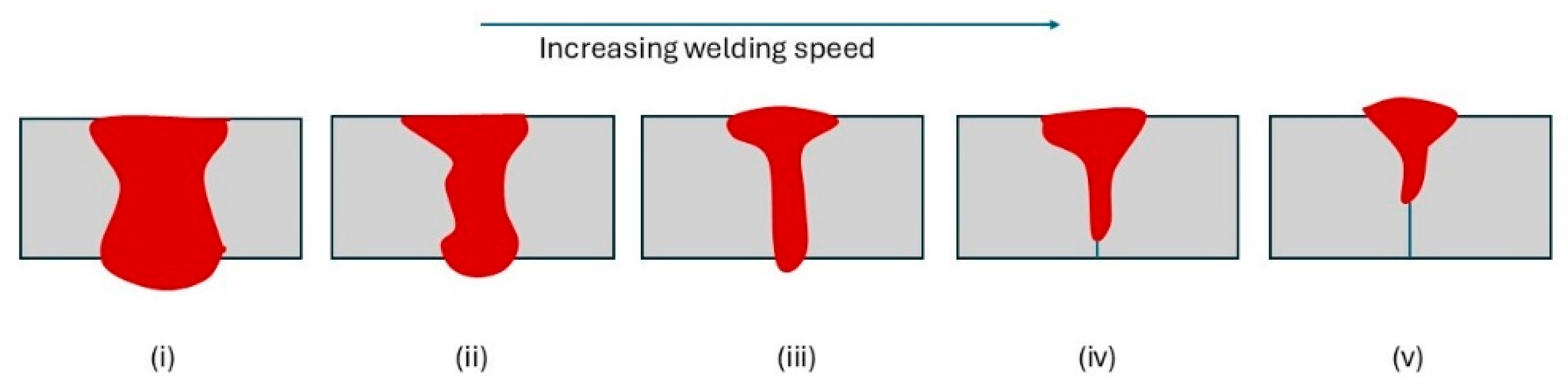

2. Laser Welding of Maraging Steel

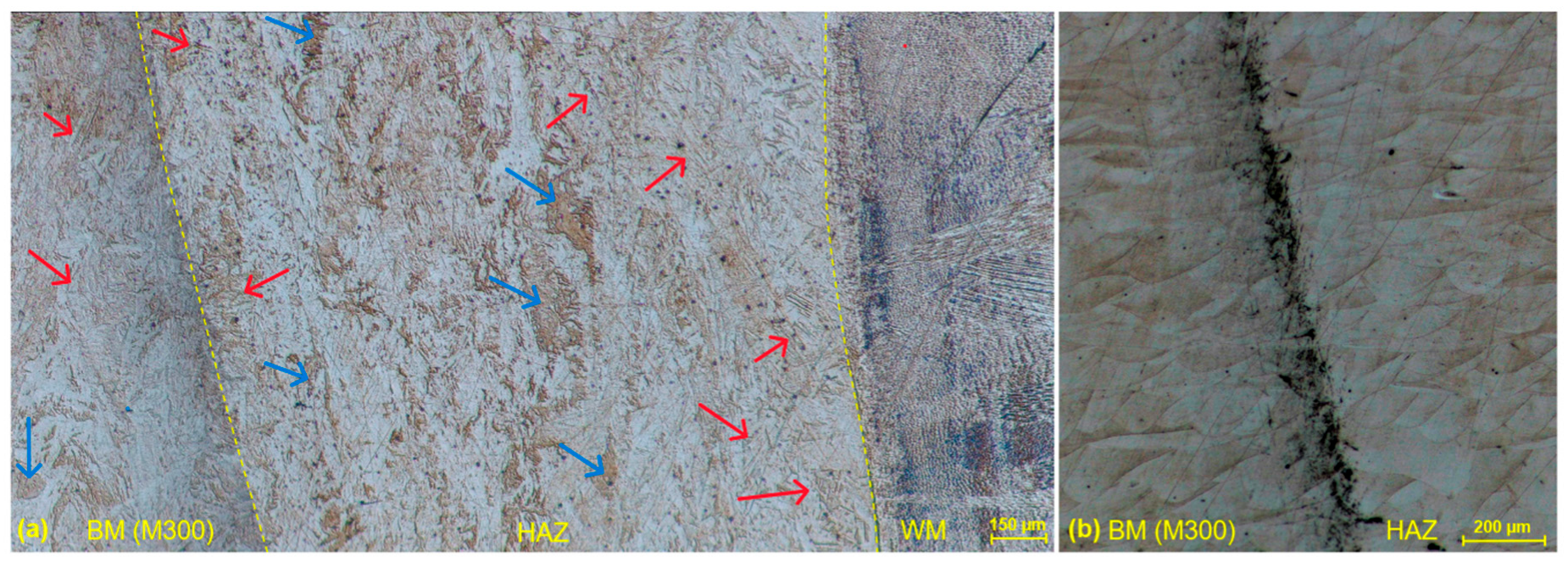

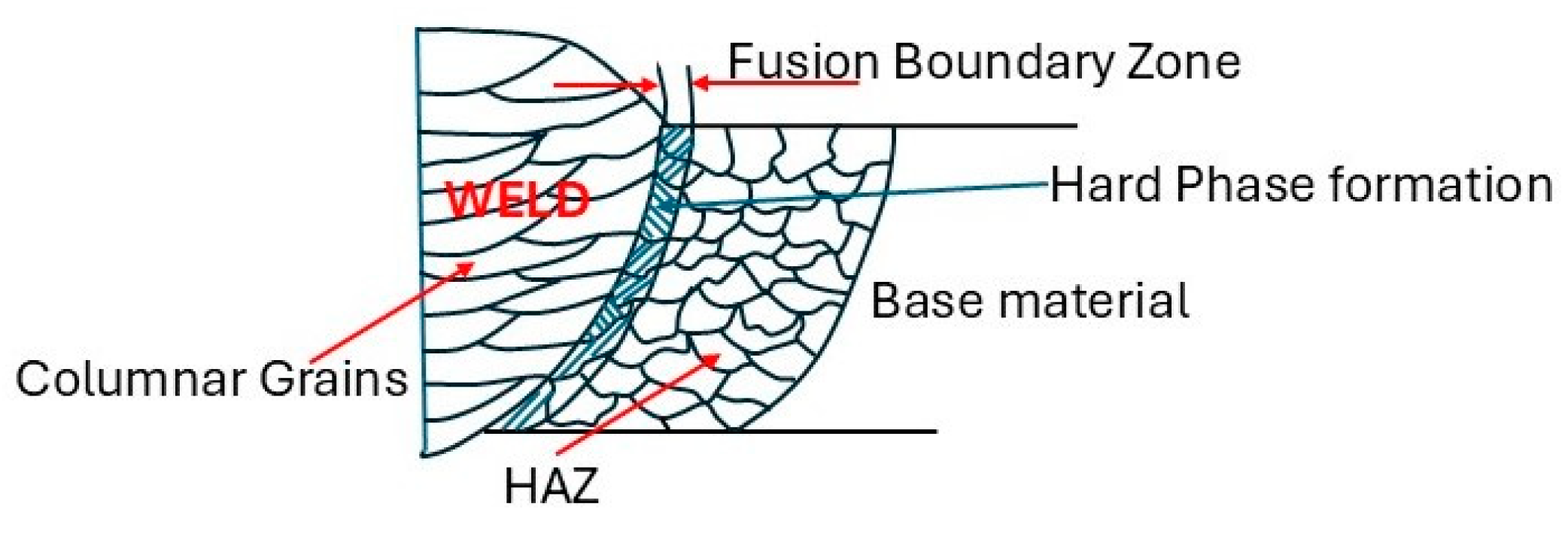

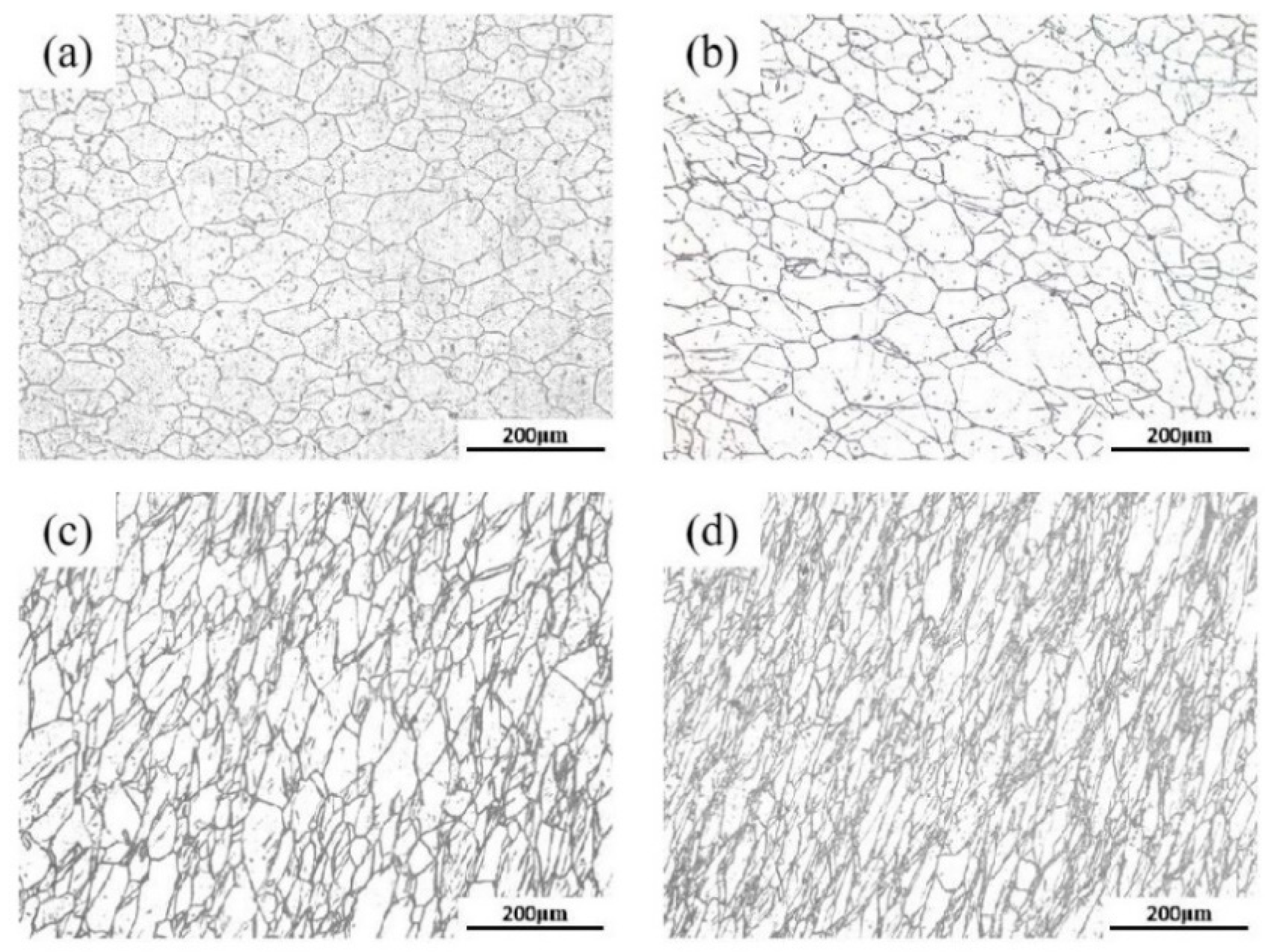

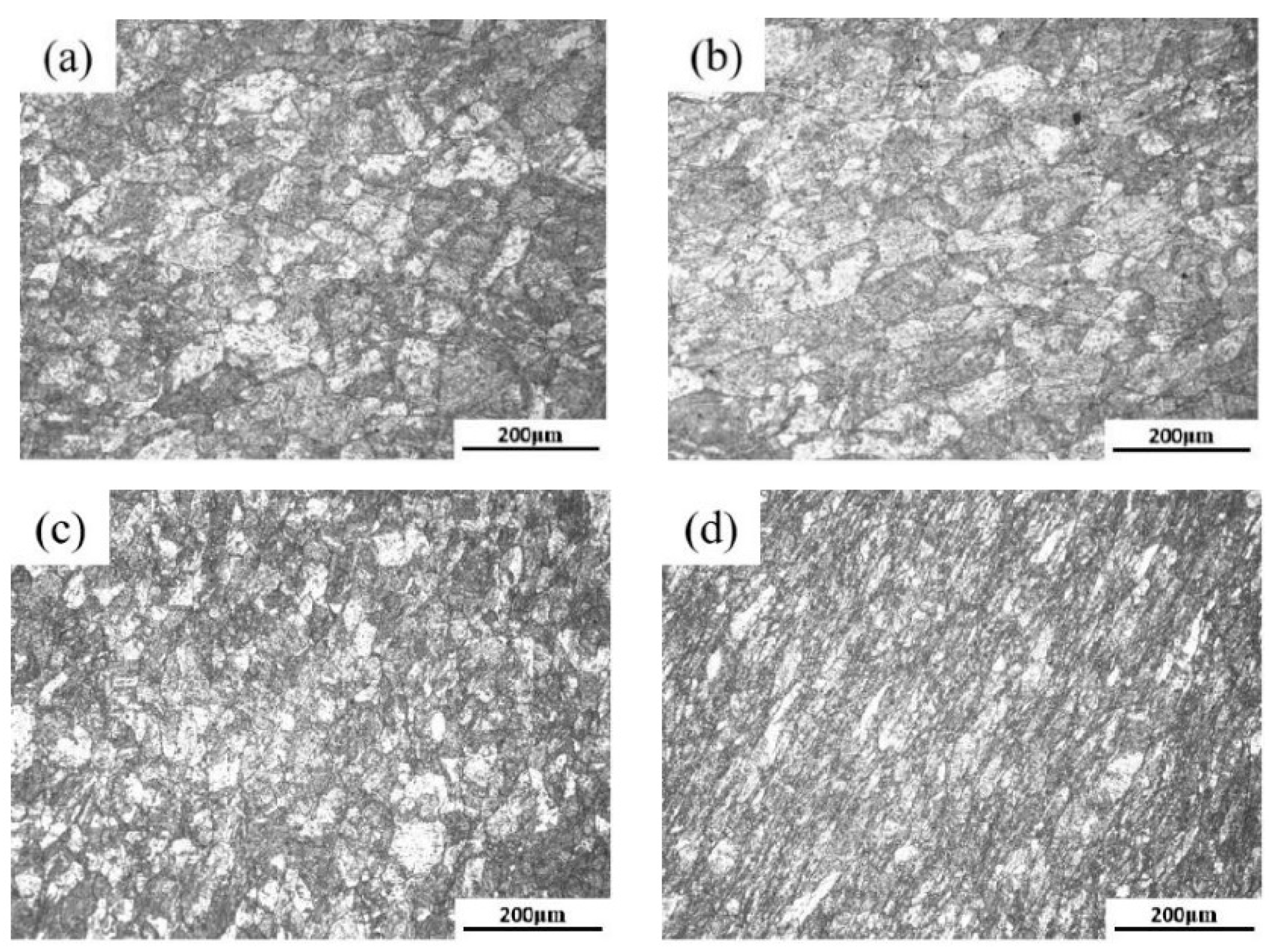

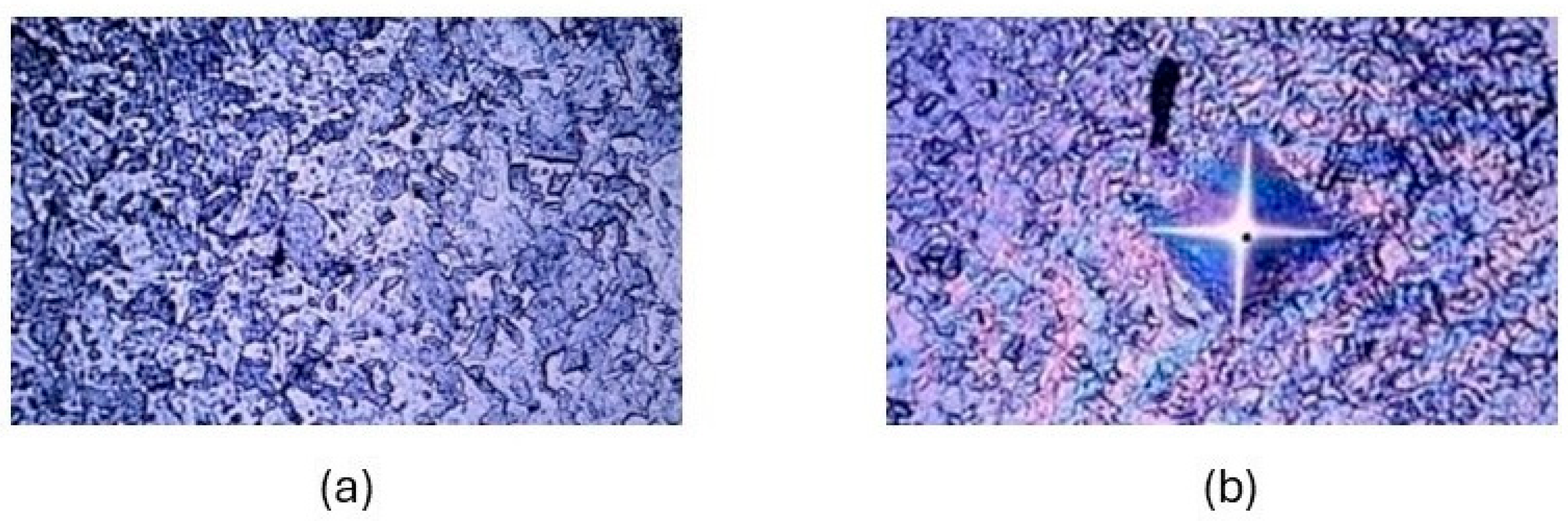

2.1. Microstructures

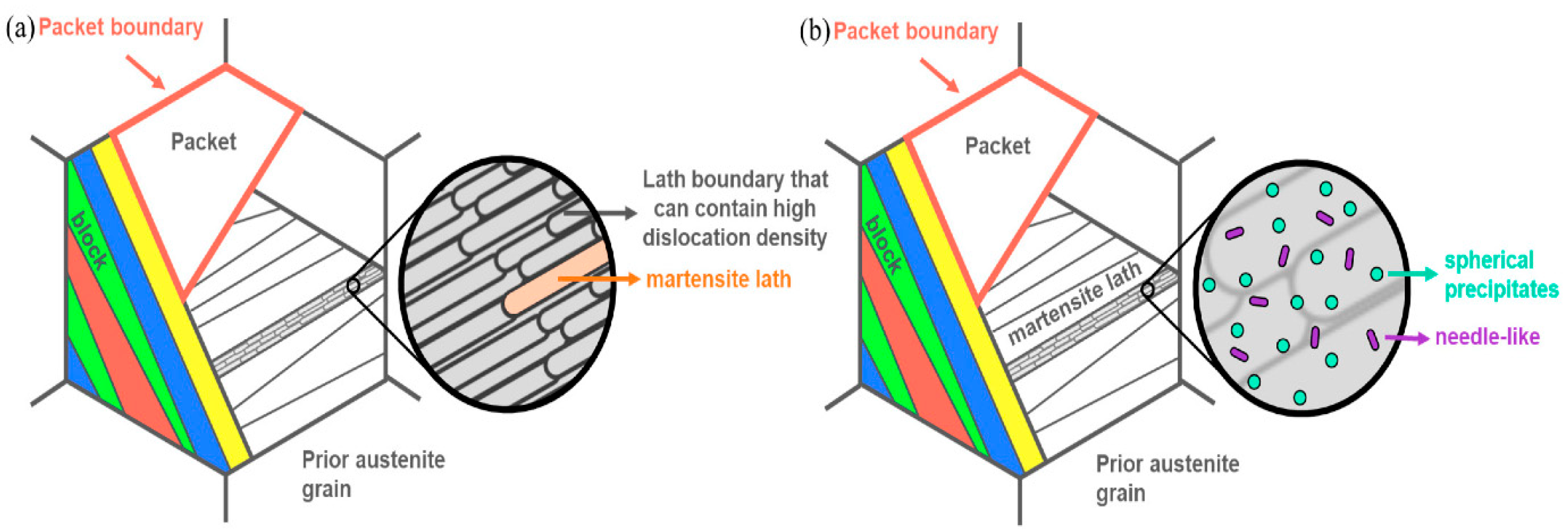

2.2. Strengthening Mechanism in Maraging Steel

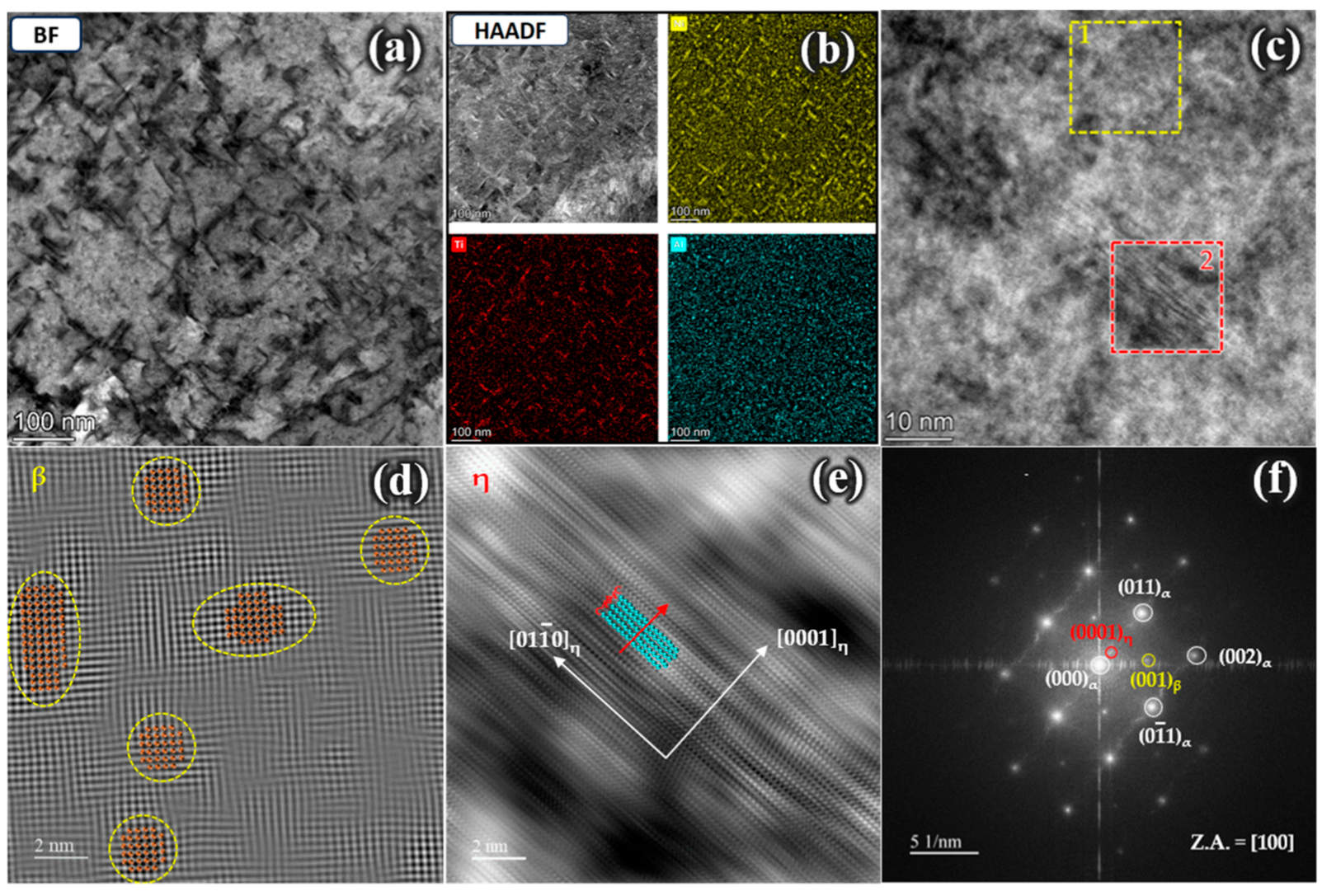

2.2.1. Precipitation

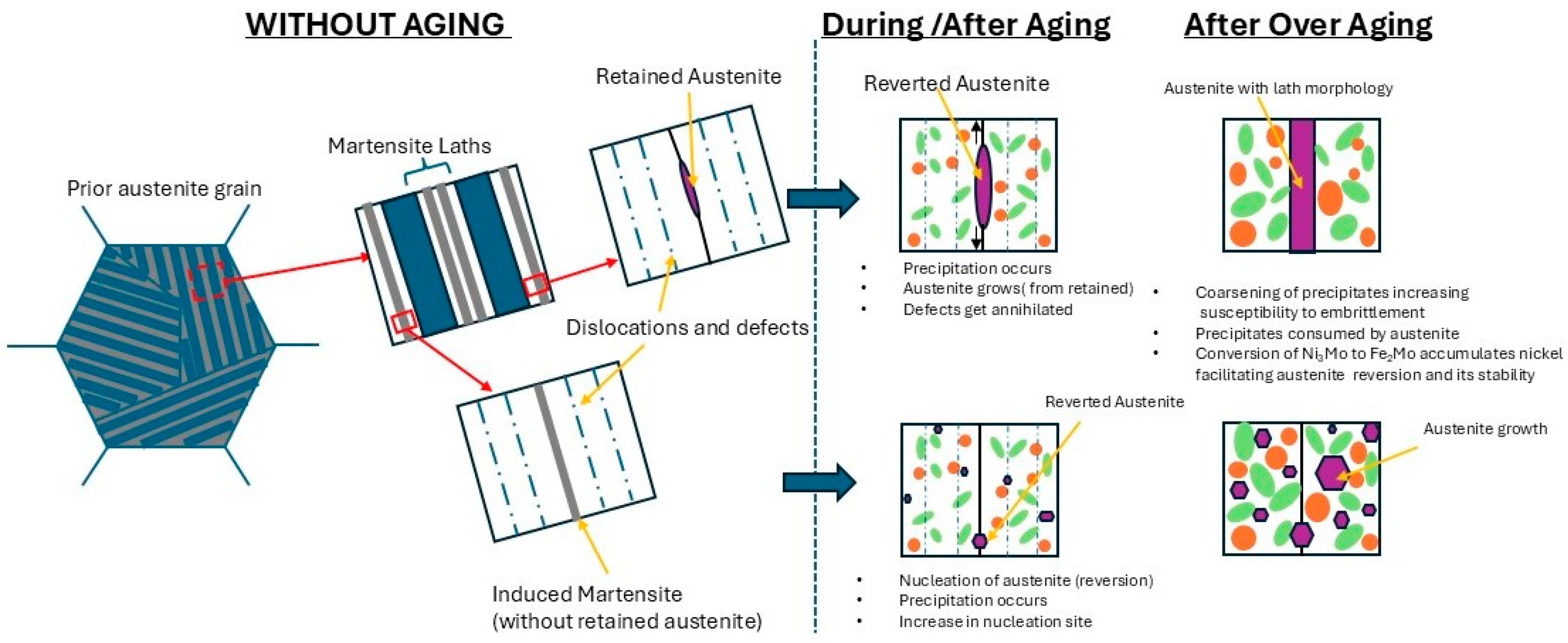

2.2.2. Reverted Austenite

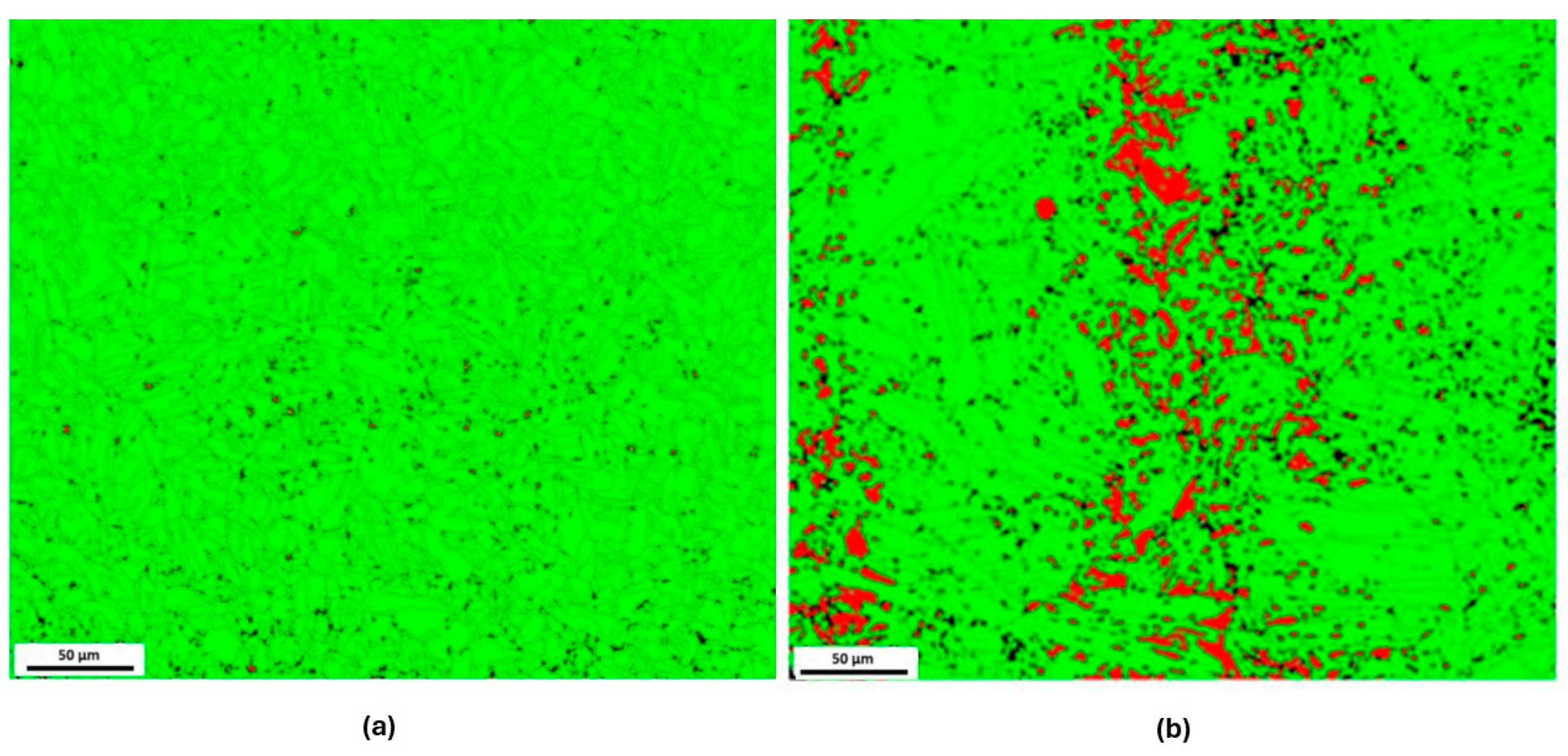

3. Mechanical Properties of As-Welded Maraging Steel

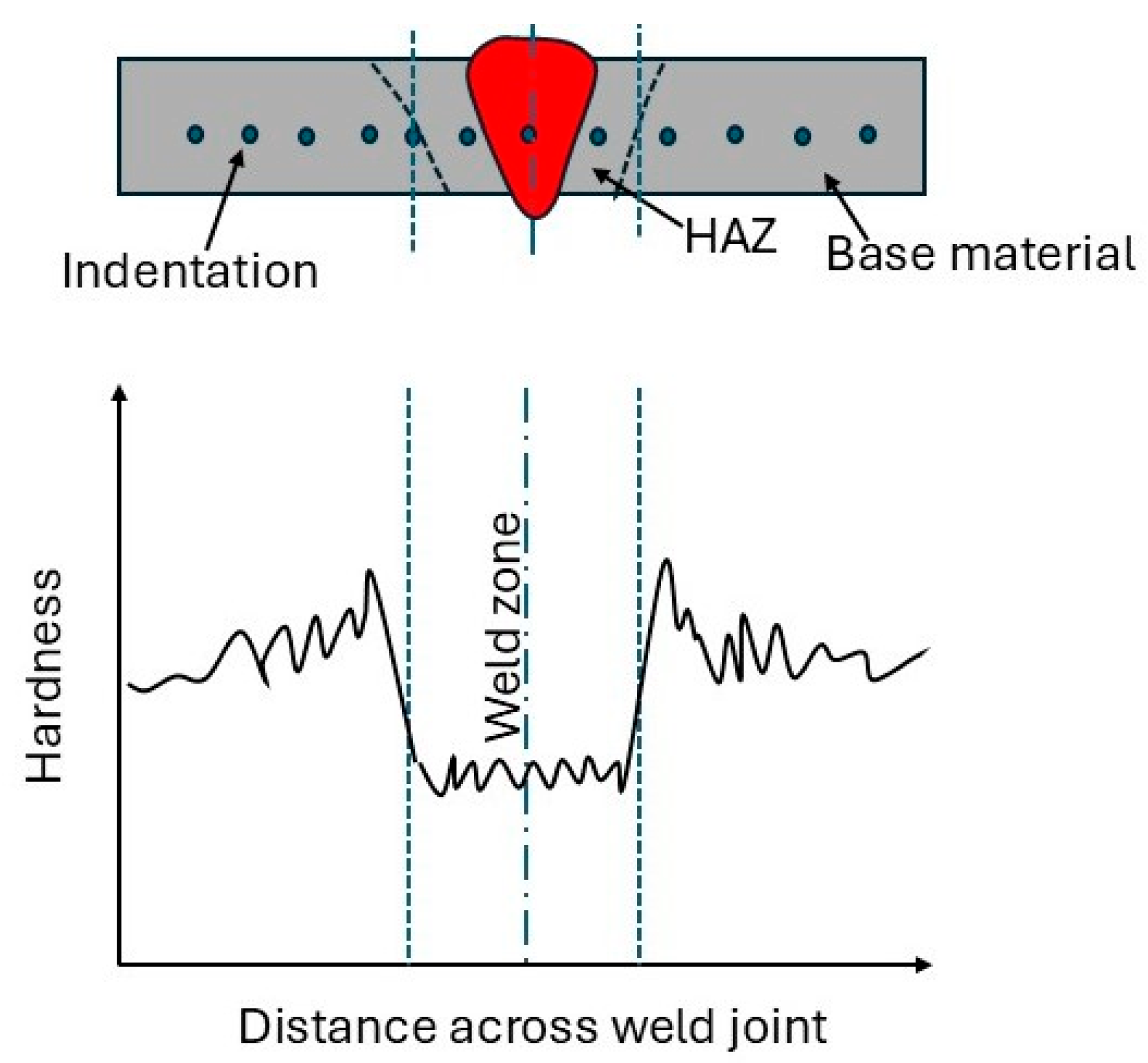

3.1. Hardness

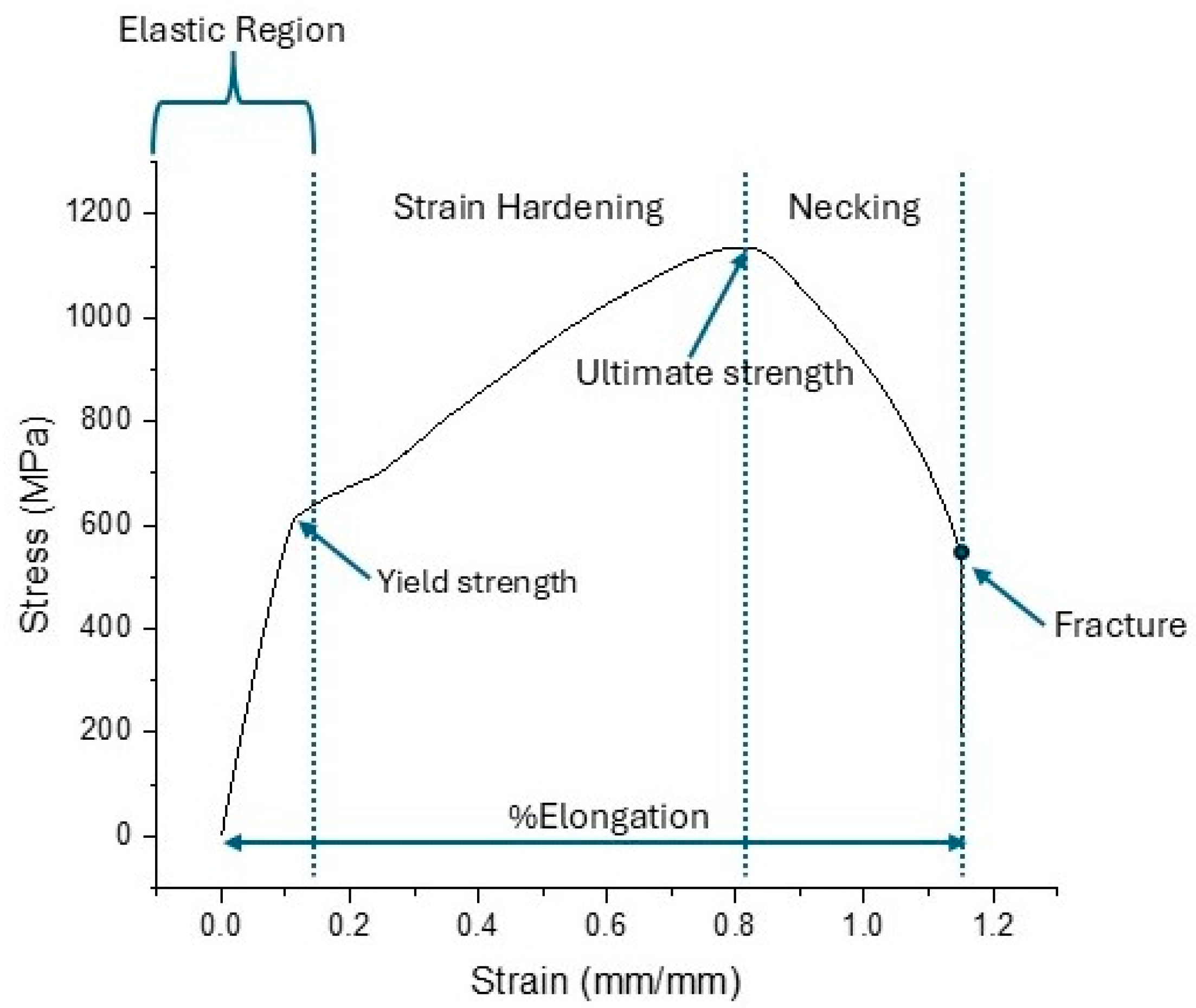

3.2. Tensile Strength

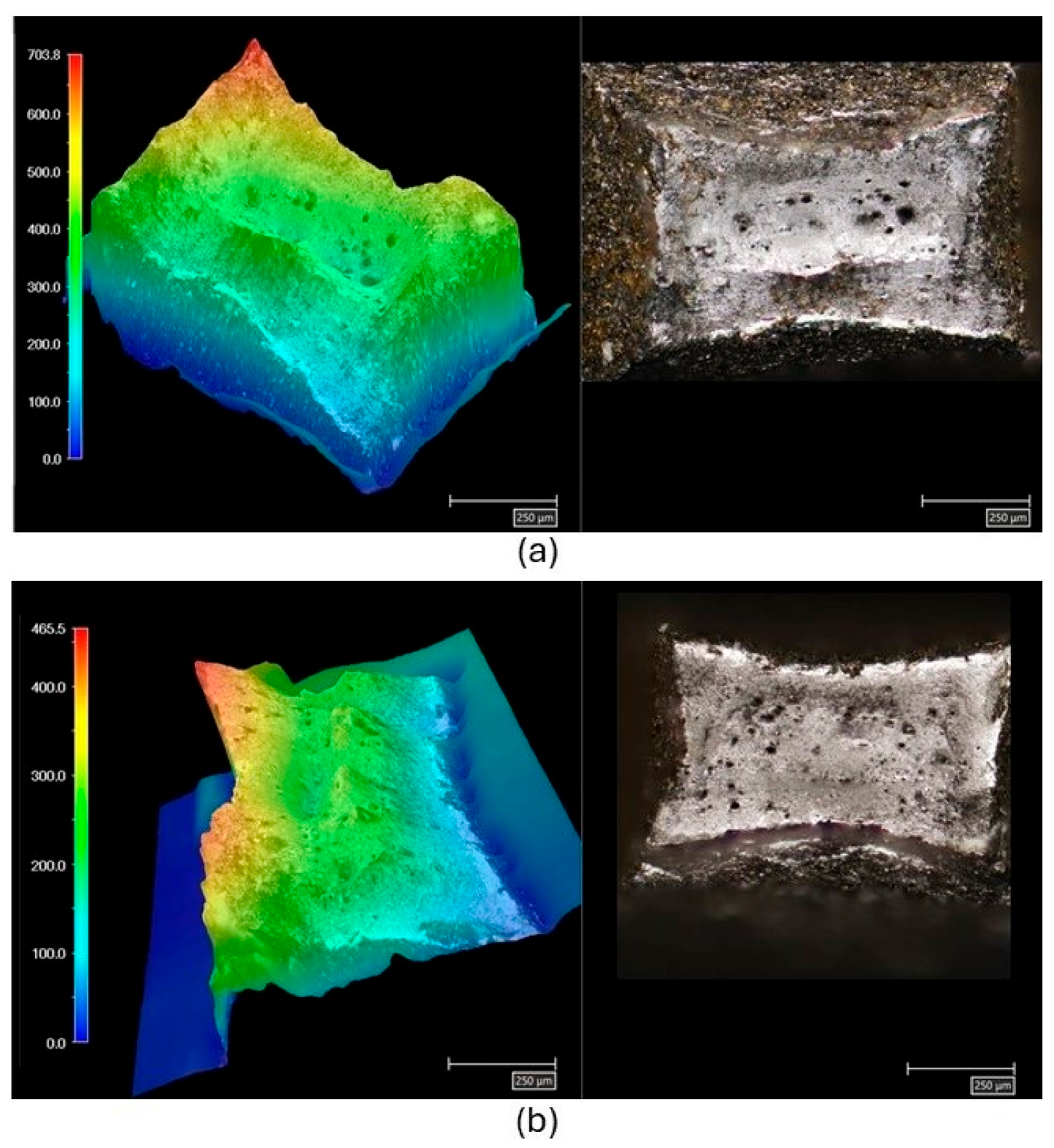

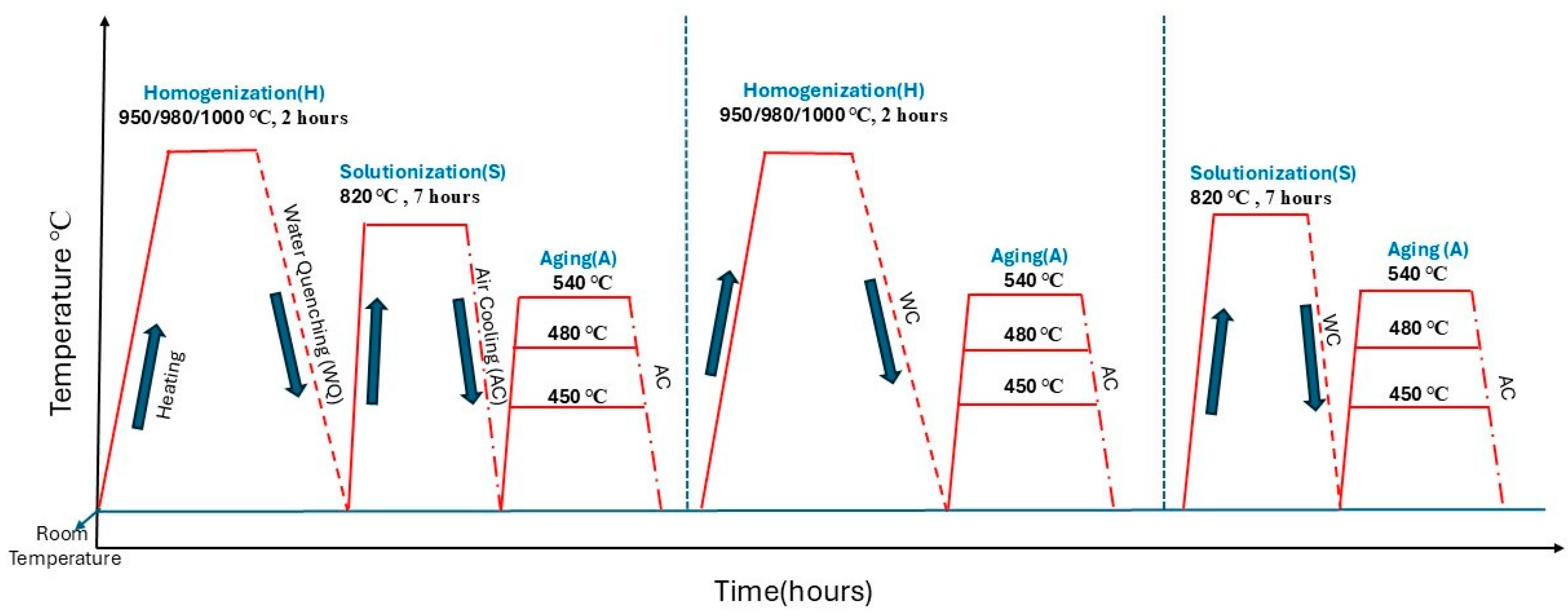

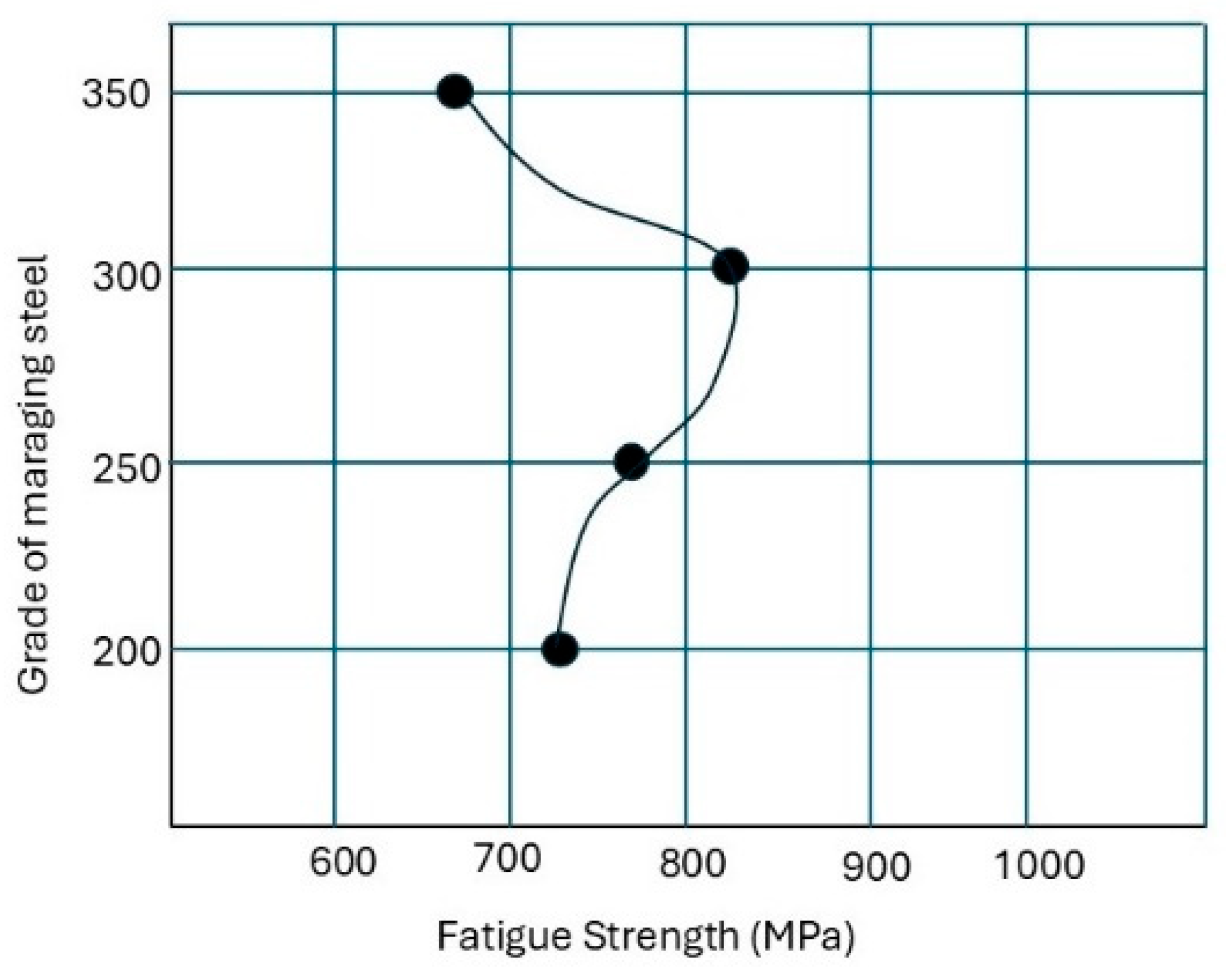

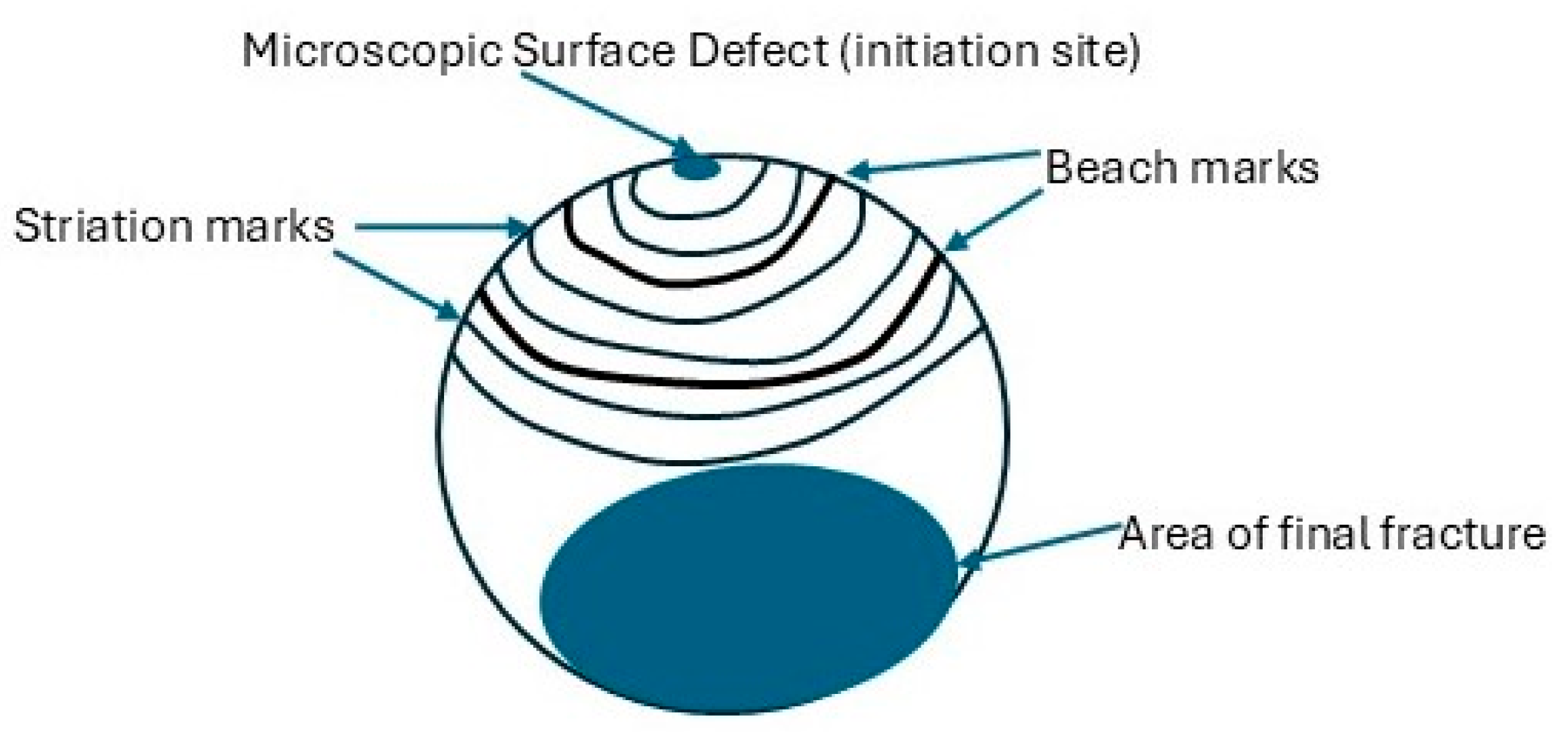

3.3. Fatigue Strength

4. Correlation Between Microstructures and Mechanical Properties

5. Present Scenario

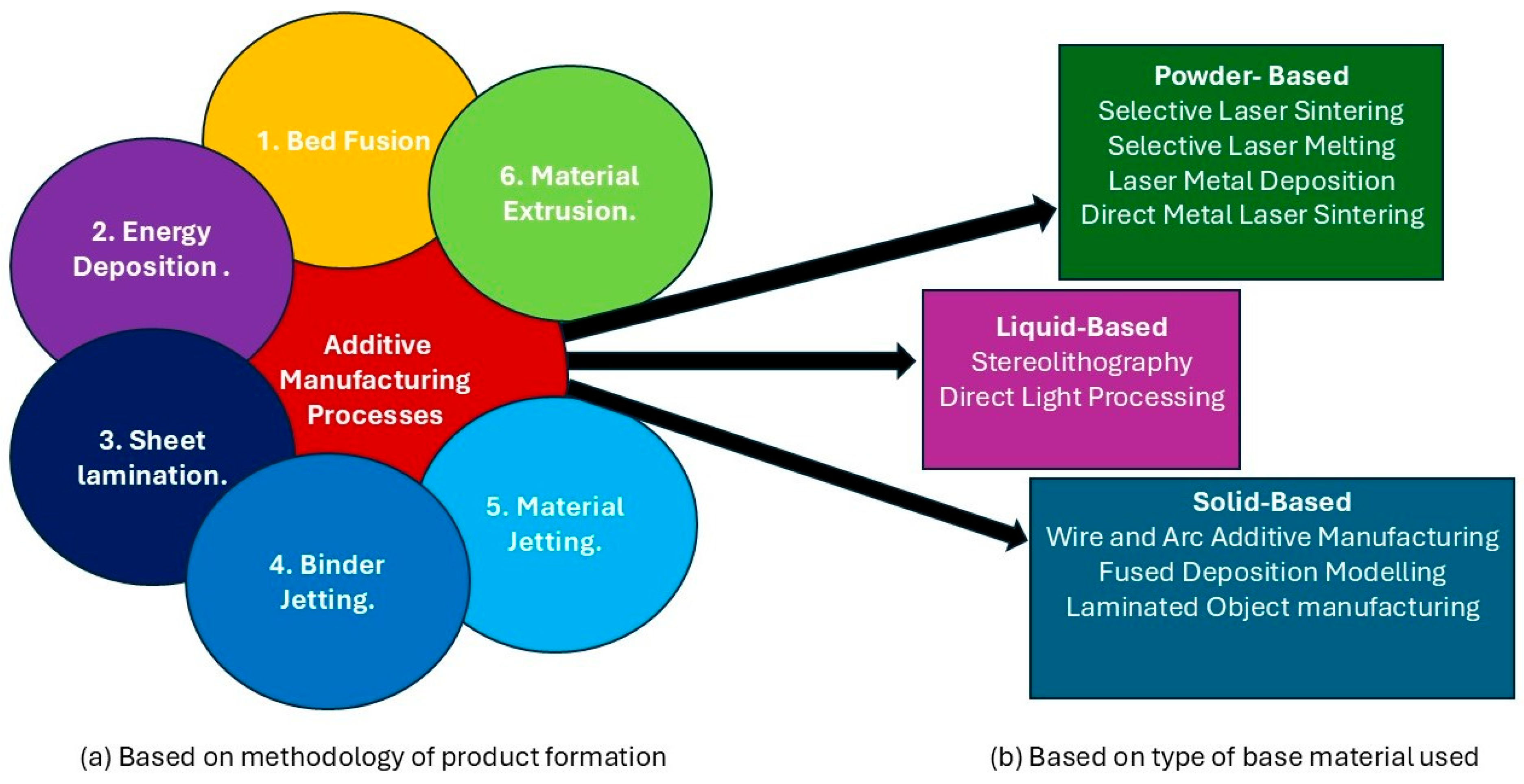

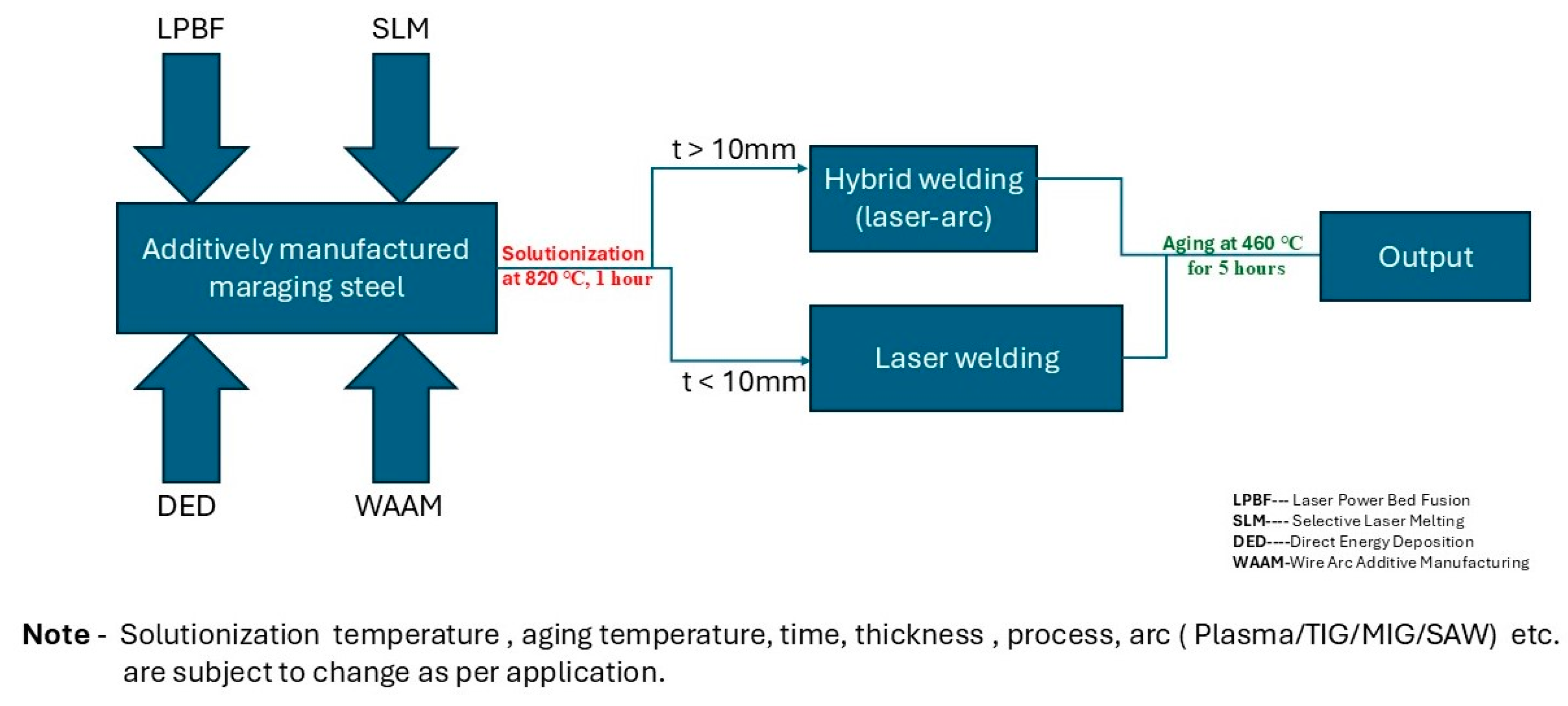

5.1. Additive Manufacturing

5.2. Hybrid Welding

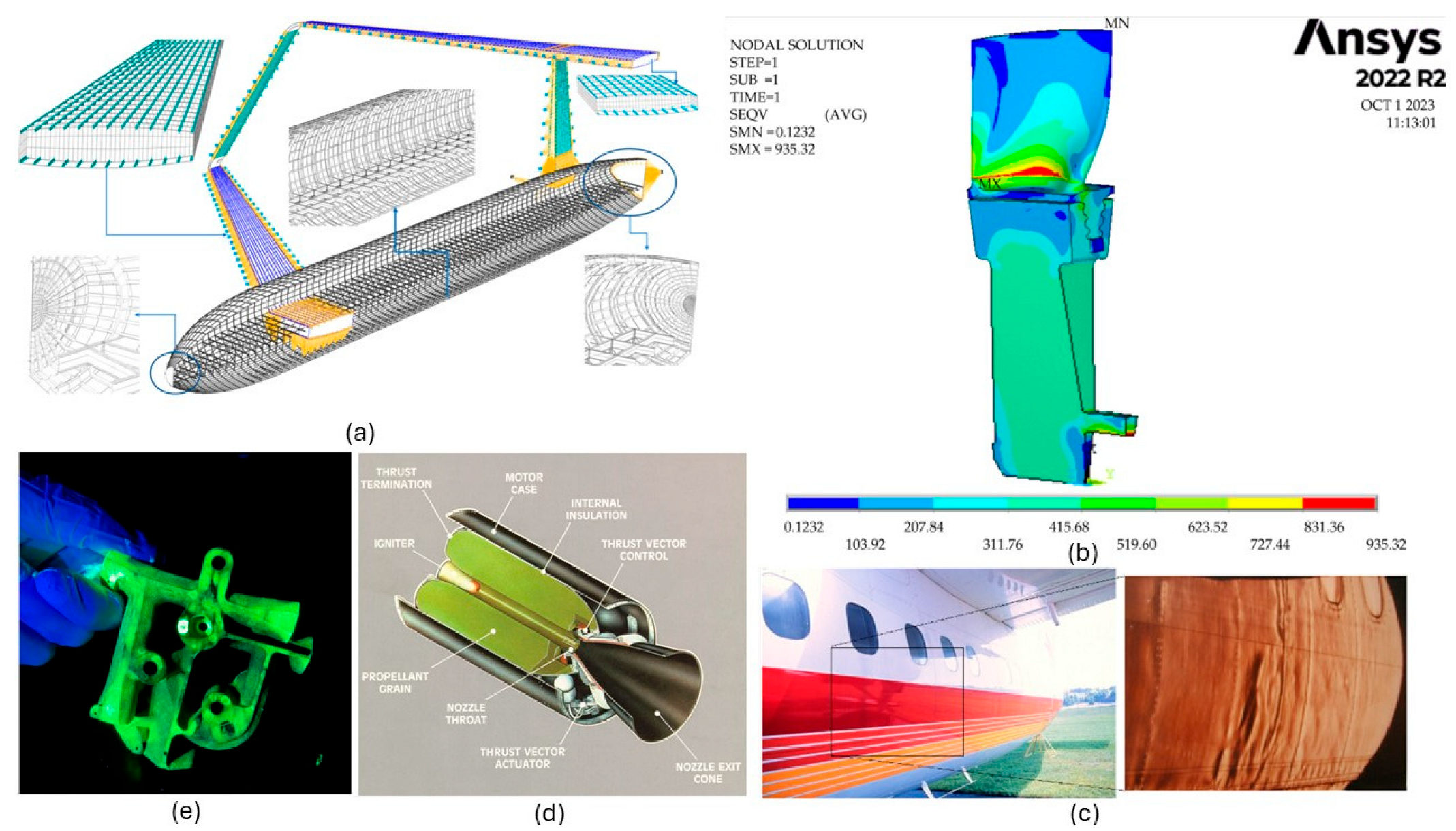

5.3. Applications

6. Summary and Future Scope

- The selection of a proper laser source, such as fibers, CO2, welding power, welding speed, residence time, etc., is important for effective laser welding of maraging steel.

- The typical issues, like undesired reverted austenite, loss of precipitates, difference in metallurgical properties with respect to hardness and strength at HAZ, weld zones, etc., are evident in laser welding of maraging steel. This should be properly dealt with by appropriate aging, along with solutionization, homogenization, or both processes.

- Retained austenite, high nickel content, etc., are the development sources for reverted austenite in maraging steel. As such, it leads to a reduction in the strength of maraging steel despite an increase in toughness and ductility.

- The development of reverted austenite in the matrix of martensite laths proves to be better than in the grain boundaries of martensite laths since the latter is the source of crack propagation in laser-welded maraging steel. Optimal copper-layer thickness facilitates the development of ε-Cu precipitates in weld zones, thereby promoting the formation of former reverted austenite.

- Copper addition in the matrix of maraging steel is manifested to increase precipitation in maraging steel. Hence, it is helpful in strengthening laser-welded maraging steel.

- Appropriate precipitate width due to aging assists in promoting reversibility of slip, thus retarding fatigue crack growth rate and improving fatigue strength.

- Shop peening, laser peening, nitriding, etc., are suggested to increase resistance processes with respect to fatigue failure of laser-welded maraging steel.

- Cryogenic treatment for maraging steel stabilizes the austenite, increasing dislocation density and refining martensite laths in maraging steel.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- NiDI. 18 Per Cent Nickel Maraging Steels—Engineering Properties; Inco Europa (Londres): London, UK, 1976; Volume 4419. [Google Scholar]

- Kizhakkinan, U.; Seetharaman, S.; Raghavan, N.; Rosen, D.W. Laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing of maraging steel: A Review. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2023, 145, 110801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzer, R.; Radis, R.; Nöhrer, M.; Schober, M.; Hochfellner, R.; Zinner, S.; Povoden-Karadeniz, E.; Kozeschnik, E.; Leitner, H. Reverted austenite in PH 13-8 Mo maraging steels. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2010, 122, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunprakash, R.; Manikandan, M. A novel approach to suppression of reverted austenite in aerospace grade thick maraging steel weldments using the turbo-TIG welding process. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2024, 38, 2277–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.S.; Lii, T.W. Electron beam deflection when welding dissimilar metals. J. Heat Transf. 1990, 112, 714–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaisheva, D.; Anchev, A.; Valkov, S.; Dunchev, V.; Kotlarski, G.; Stoyanov, B.; Ormanova, M.; Atanasova, M.; Petrov, P. Influence of beam power on structures and mechanical characteristics of electron-beam-welded joints of copper and stainless steel. Metals 2022, 12, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, R.; Zak, A.; Shirizly, A.; Leitner, A.; Louzon, E. Method for producing porosity-free joints in laser beam welding of maraging steel 250. Inter. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 94, 2763–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

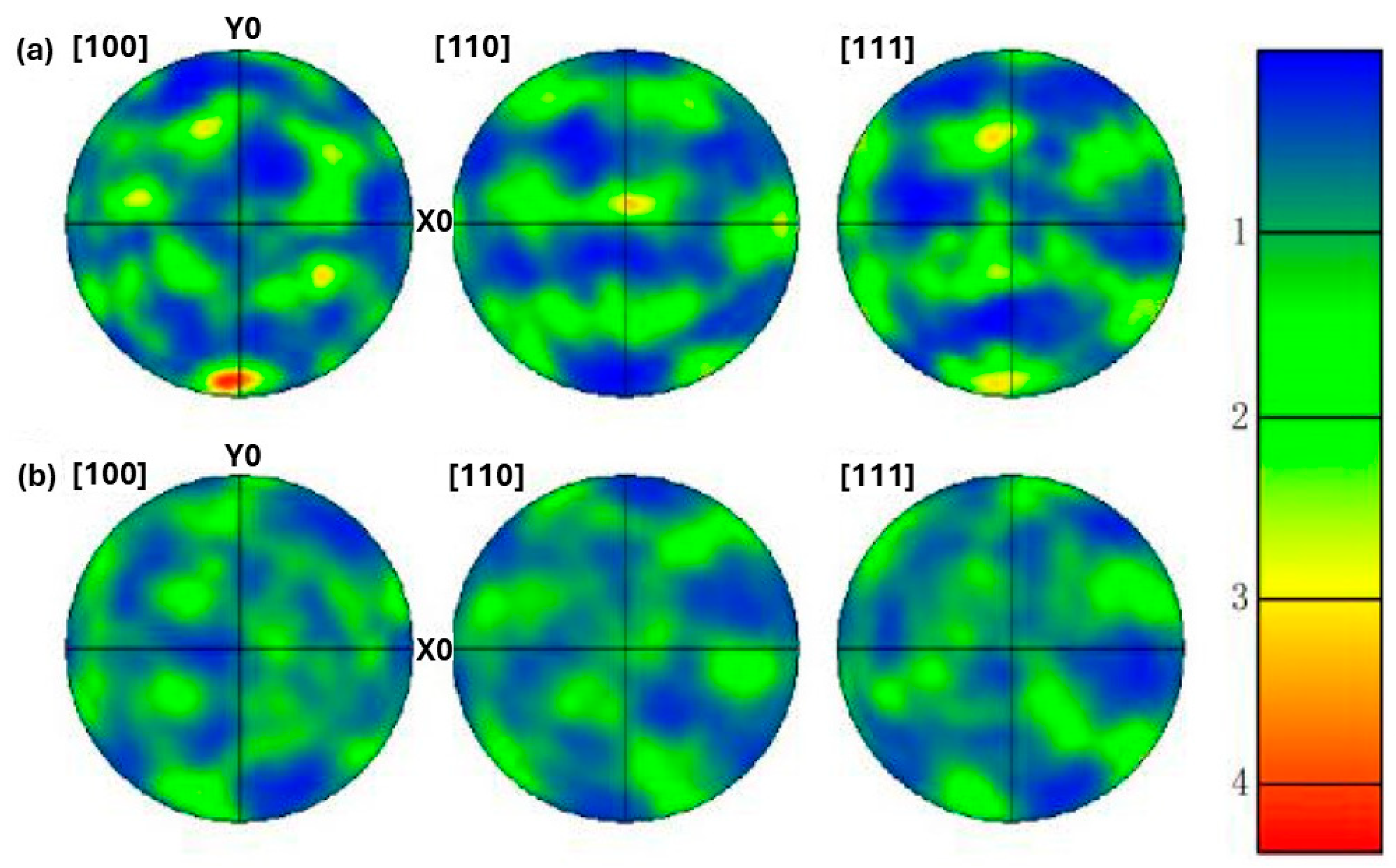

- Mondal, J.; Yadav, M.K.; Kumar, D.; Bandyopadhyay, T.K. The effect of post-weld aging treatments on the microstructure, texture, and mechanical properties of grade 250 maraging steel laser weldments. J Mater. Eng. Perform. 2024, 34, 2242–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanton, L.; Abdalla, A.J.; De Lima, M.S.F. Heat treatment and Yb-fiber laser welding of a maraging steel. Weld. J. 2014, 93, 362–368. [Google Scholar]

- Tuz, L.; Sokołowski, Ł.; Stano, S. Effect of post-weld heat treatment on microstructure and hardness of laser beam welded 17-4 PH stainless steel. Materials 2023, 16, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami Balajaddeh, M.; Naffakh-Moosavy, H. Pulsed Nd: YAG laser welding of 17-4 PH stainless steel: Microstructure, mechanical properties, and weldability investigation. Opt. Laser Technol. 2019, 119, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Lu, F.; Yang, R.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Elmi Hosseini, S.R. A comparative study on fiber laser and CO2 laser welding of inconel 617. Mater. Des. 2015, 76, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, S. Handbook of Laser Welding Technologies; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S.; Bratt, C.; Mueller, P.; Cuddy, J.; Shankar, K. Laser beam welding of titanium—A comparison of CO2 and fiber laser for potential aerospace applications. In Proceedings of the ICALEO 2008—27th International Congress on Applications of Lasers and Electro-Optics, Congress Proceedings, Temecula, CA, USA, 20–23 October 2008; pp. 750–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohit, B.; Muktinutalapati, N.R. Austenite reversion in 18% Ni maraging steel and its weldments. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2018, 34, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, J.R.; Potta, M.; Adepu, K.; Katta, R.K.; Gankidi, M.R. A comparative evaluation of microstructural and mechanical behavior of fiber laser beam and tungsten inert gas dissimilar ultra high strength steel welds. Defence Technol. 2016, 12, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.K.; Swathi Kiranmayee, M.; Manwatkar, S.K. Failure analysis of maraging steel fasteners used in nozzle assembly of solid propulsion system. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2013, 27, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinaharan, I.; Ramesh, R.; Palanivel, R.; Jen, T.C. Effect of CO2 laser beam welding on microstructure and tensile strength of C250 maraging steel. Lasers Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 12, 274–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geľatko, M.; Vandžura, R.; Botko, F.; Hatala, M. Electron beam welding of dissimilar stainless steel and maraging steel joints. Materials 2024, 17, 5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, R.S. Welding Engineering and Technology, 3rd ed.; Khanna Publishers: Delhi, India, 2022; Chapter 2; pp. 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, J.F. Metallurgy of Welding, 6th ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Welding and Other Joining Technologies: Cambridge, UK, 1999; Chapter 6; pp. 145–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Fonseca, D.P.M.; Altoé, M.V.P.; Archanjo, B.S.; Annese, E.; Padilha, A.F. Influence of Mo content on the precipitation behavior of 13Ni maraging ultra-high strength steels. Metals 2023, 13, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitosa, A.L.M.; Escobar, J.; Ribamar, G.G.; Avila, J.A.; Padilha, A.F. Direct observation of austenite reversion during aging of 18Ni (350 grade) maraging steel through in-situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction. Metall. Mater. Trans. A Phys. Metall. Mater. Sci. 2022, 53, 2922–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, B.; Manoharan, M.; Natarajan, A.; Muktinutalapati, N.R.; Reddy, G.M. Laser hybrid welding-an advanced joining technique for welding of thick plates of maraging steel. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2024, 34, 8773–8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Meng, F.; Lv, X.; Liu, H.; Gao, X.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y. Improvement of mechanical properties of stainless maraging steel laser weldments by post-weld ageing treatments. Mater. Des. 2012, 40, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.P.; Tsay, L.W.; Chen, C. Notched tensile testing of T-200 maraging steel and its laser welds in hydrogen. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2003, 346, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, S.; Nascimento Ferreira, R.; de Souza Santos, L.A.; de Jesus Silva, J.W.; Bagio Scheid, V.H.; Abdalla, A.J. Microstructural characterization of joints of maraging 300 steel welded by laser and subjected to plasma nitriding treatment. Mater. Sci. Forum 2016, 869, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Shan, J.; Wang, C.; Tian, Z. The role of copper in microstructures and mechanical properties of laser-welded Fe-19Ni-3Mo-1.5Ti maraging steel joint. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 681, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, F.; Baloch, R.A.; Ahmed, B.; Naz, N. Investigation into microstructures of maraging steel 250 weldments and effect of post-weld heat treatments. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2010, 19, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippold, J.C. Welding Metallurgy and Weldability, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; Chapter 2; pp. 45–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuerlein, K.U.; Shojaati, M.; Ansari, M.; Panzer, H.; Shahabad, S.I.; Keshavarz, M.K.; Zaeh, M.F.; Maleksaeedi, S. Microstructure simulation of maraging steel 1.2709 processed by powder bed fusion of metals using a laser beam: A cellular automata approach with varying process parameters. Results Mater. 2025, 25, 100667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, A.; Kasuya, T.; Ghoniem, N.M. Stress field and interaction forces between dislocations and precipitate distributions. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2024, 125, 7468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.R.; Jardini, A.L.; Del Conte, E.G. Effects of cutting parameters on roughness and residual stress of maraging steel specimens produced by additive manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 111, 2449–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkata Ramana, P.; Madhusudhan Reddy, G.; Mohandas, T. Microstructure, hardness and residual stress distribution in maraging steel gas tungsten arc weldments. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2008, 13, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, U.K.; Dey, G.K.; Asundi, M.K. Precipitation hardening in 350 grade maraging steel. Metall. Trans. A 1993, 24, 2429–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Yuan, L.; Xu, W.; Shan, D.; Guo, B. Effects of forging and heat treatment on martensite lath, recrystallization and mechanical properties evolution of 18Ni (250) maraging steel. Materials 2022, 15, 4600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, U.K.; Dey, G.K.; Sethumadhavan, V. Effects of austenite reversion during overageing on the mechanical properties of 18 Ni (350) maraging steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 399, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, N.; Ito, Y.; Nishida, R.; Suzuki, A.; Kobashi, M.; Kato, M. Austenite reversion behavior of maraging steel additive-manufactured by laser powder bed fusion. ISIJ Int. 2024, 63, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Tian, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhao, W.; Wang, C.; Sun, Y.; Liang, J.; Yang, Z.; Xie, J. The role of Al/Ti in precipitate-strengthened and austenite-toughened Co-free maraging stainless steel. Materials 2024, 17, 5337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wang, S.; Yu, H.; Wu, G.; Gao, J.; Wu, H.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, C.; Mao, X. Effect of precipitation on the mechanical behavior of vanadium micro-alloyed HSLA steel investigated by microstructural evolution and strength modeling. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 1874, 145313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisl, S.; Van Steenberge, N.; Schnitzer, R. Strengthening effect of NiAl and Ni3Ti precipitates in Co-free maraging steels. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 7149–7160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, R.; Mazumder, S.; Batra, I.S.; Dey, G.K.; Banerjee, S. Precipitation in 18 wt% Ni maraging steel of grade 350. Acta Mater. 2000, 48, 1187–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereloma, E.V.; Stohr, R.A.; Miller, M.K.; Ringer, S.P. Observation of precipitation evolution in Fe-Ni-Mn-Ti-Al maraging steel by atom probe tomography. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2009, 40, 5993–6002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K.; Okamoto, H. Transmission electron microscopy study of strengthening precipitates in 18% Ni maraging steel. Trans. Jpn. Inst. Met. 1971, 2, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Fawkhry, M.K.; Eissa, M.; Fathy, A.; Mattar, T. Development of maraging steel with retained austenite in martensite matrix. Mater. Today Proc. 2015, 425, 2119–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, F.; Rainforth, W.M. The formation mechanism of reverted austenite in Mn-based maraging steels. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 6624–6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Miyamoto, G.; Toji, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Furuhara, T. Role of cementite and retained austenite on austenite reversion from martensite and bainite in Fe-2Mn-1.5Si-0.3C alloy. Acta Mater. 2021, 209, 116772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Dai, Z.; Huang, M.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Chen, H. Effect of pre-existed austenite on austenite reversion and mechanical behavior of an Fe-0.2C-8Mn-2Al medium Mn steel. Acta Mater. 2018, 148, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampillo, C.A.; Paxton, H.W. The effect of reverted austenite on the mechanical properties and toughness of 12 Ni and 18 Ni (200) maraging steels. Metall. Trans. 1972, 3, 2895–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Shan, J.; Wang, C.; Tian, Z. Effect of post-weld heat treatments on strength and toughness behavior of T-250 maraging steel welded by laser beam. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 663, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsdorf, L.; Jeannin, O.; Barbier, D.; Mitsuhara, M.; Raabe, D.; Tasan, C.C. Multiple mechanisms of lath martensite plasticity. Acta Mater. 2016, 121, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jägle, E.A.; Choi, P.P.; Van Humbeeck, J.; Raabe, D. Precipitation and austenite reversion behavior of a maraging steel produced by selective laser melting. J. Mater. Res. 2014, 29, 2072–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.; Duan, M.; Ming, Z.; Peng, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, M.; Wang, W.; Wang, K. Segregation-dependent mechanical stability of reverted austenite and resultant tensile properties of Co-free maraging steel fabricated by wire-arc directed energy deposition. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 901, 146569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malitckii, E.; Yagodzinskyy, Y.; Vilaҫa, P. Role of retained austenite in hydrogen trapping and hydrogen-assisted fatigue fracture of high-strength steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 760, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.P.M.; Béreš, M.; Bastos, I.N.; Tavares, S.S.M.; Abreu, H.F.G.; Gomes da Silva, M.J. Hydrogen embrittlement of ultra high strength 300 grade maraging steel. Corros. Sci. 2015, 101, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodárek, V.; Rožnovská, G.; Kuboň, Z.; Volodarskaja, A.; Palupčíková, R. The effect of long-term ageing at 475 °C on microstructure and properties of a precipitation hardening martensitic stainless steel. Metals 2022, 12, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, F.F.; Escobar, J.D.; Oliveira, J.P.; Jardini, A.L.; Bose Filho, W.W.; Avila, J.A. Austenite reversion kinetics and stability during tempering of an additively manufactured maraging 300 steel. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 29, 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, L.G.; Plaut, R.L.; de Lima, N.B.; Padilha, A.F. Kinetics of martensite reversion to austenite during overaging in a maraging 350 steel. ISIJ Int. 2019, 59, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yin, Z. Reverted austenite during aging in 18Ni (350) maraging steel. Mater. Lett. 1995, 24, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, L.P.M.; Béreš, M.; de Castro, M.O.; Sarvezuk, P.W.C.; Wu, L.; Herculano, L.F.G.; Paesano, A.; Silva, C.C.; Masoumi, M.; de Abreu, H.F.G. Kinetics of reverted austenite in 18 wt.% Ni grade 300 maraging steel: An in-situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction and texture study. JOM 2020, 72, 3502–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitosa, A.L.M.; Ribamar, G.G.; Escobar, J.; Sonkusare, R.; Boll, T.; Coury, F.; Ávila, J.; Oliveira, J.; Padilha, A. Precipitation and reverted austenite formation in maraging 350 steel: Competition or cooperation? Acta Mater. 2024, 270, 119865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, M.A.; Peitsch, P.; Svoboda, H.G. Phase transformation kinetics during post-weld heat treatment in weldments of C-250 maraging steel. Materials 2025, 18, 2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, B.; Kourousis, K.I. A review of factors affecting the mechanical properties of maraging steel 300 fabricated via laser powder bed fusion. Metals 2020, 10, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, F.; Shifa, M.; Baloch, R.A. Effect of overaging conditions on microstructure and mechanical properties of maraging steel. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 2020, 62, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, B.; Bandhopadhyay, T.K. Issues and concern in dissimilar joining including additive manufacturing with specific emphasis to maraging steels with other high-strength steels-a comprehensive review. Steel Res. Int. 2025, 96, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaško, M.; Rosenberg, G. Correlation between hardness and tensile properties in ultra-high strength dual phase steels: Short communication. Mater. Eng. 2012, 18, 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Cahoon, J.R.; Broughton, W.H.; Kutzak, A.R. The determination of yield strength from hardness measurements. Metall. Trans. 1971, 2, 1979–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh Narayanan, P.; Sreekumar, K.; Natarajan, A.; Sinha, P.P. Metallographic investigations of the heat-affected zone II/parent metal interface cracking in 18Ni maraging steel welded structures. J. Mater. Sci. 1990, 25, 4587–4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, A.; Toyohiro, T.; Segawa, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Miura, H. Embrittlement fracture behavior and mechanical properties in heat-affected zone of welded maraging steel. Materials 2024, 17, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkumar, V.; Arivazhagan, N.; Devendranath, R.K. Studies on welding of maraging steels. Procedia Eng. 2014, 75, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima Filho, V.X.; Barros, I.F.; De Abreu, H.F.G. Influence of solution annealing on microstructure and mechanical properties of maraging 300 steel. Mater. Res. 2017, 20, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, R.; Saravanan, M.; Singaravel, B.; Sathiya, P. Effect of heat input and post-weld heat treatment on the mechanical and metallurgical characteristics of laser-welded maraging steel joints. Surf. Rev. Lett. 2017, 24, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Zhou, K.; Ma, W.; Zhang, P.; Liu, M.; Kuang, T. Microstructural evolution, nanoprecipitation behavior and mechanical properties of selective laser melted high-performance grade 300 maraging steel. Mater. Des. 2017, 134, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Geng, R.; Lei, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, C. Effect of aging treatment on the microstructure and properties of 2.2 GPa tungsten-containing maraging steel. Materials 2023, 16, 4918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, J.J.M.; da Silva Lima, M.N.; Souza, P.H.L.; de Oliveira, C.A.S.; de Vasconcelos, I.F.; da Silva Nunes, J.M.; Rodrigues, S.F.; de Abreu, H.F.G. Atomic rearrangement and phase transformation during aging at 480 °C in a Maraging-300 steel. J. Phase Equilibria Diffus. 2025, 46, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Jia, C.; Shi, X.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Yan, W.; Rong, L. Toughness degradation caused by reversed austenite formed during over-aging treatment in a 2.3 GPa maraging steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 38, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, A.; Wang, X.; Cui, Y. Multiscale modelling of precipitation hardening: A review. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Theory 2024, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.F.; Sun, L.G.; Qin, H.L.; Bi, Z.N.; Li, D.F. A molecular dynamics study on the dislocation-precipitate interaction in a nickel based superalloy during the tensile deformation. Materials 2023, 16, 6140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nageswara Rao, M.; Narayana Murty, S.V.S. Hot deformation of 18 % Ni maraging steels—A review. Mater. Perform. Charact. 2019, 8, 742–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.Q.; Kang, X.; Zhao, G.P. Fatigue properties of the ultra-high strength steel TM210A. Materials 2017, 10, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.K.; Wang, B.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Z.F. A fast evaluation method for fatigue strength of maraging steel: The minimum strength principle. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 789, 139659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.C.; Li, S.X.; Wang, Z.G.; Zhang, Z.F. General relation between tensile strength and fatigue strength of metallic materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2013, 564, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, T.S.; Nelson, E.E.; Marshall, G.C. Stress corrosion cracking susceptibility of 18 Ni maraging steel. NASA Tech. Mem. 1974, 1, 64837. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, Z.; Liu, S.; Ye, L.; Li, Y.; He, C.; Chen, J.; Tang, J.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, X. Mechanism of precipitate microstructure affecting fatigue behavior of 7020 aluminum alloy. Materials 2020, 13, 3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangid, M.D. The physics of fatigue crack initiation. Int. J. Fatigue 2013, 57, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, N.; Ding, N.; Qu, S.; Guo, W.; Liu, L.; Xu, N.; Tian, L.; Xu, H.; Chen, X.; Zaïri, F.; et al. Failure modes, mechanisms and causes of shafts in mechanical equipment. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 136, 106216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohit, B.; Muktinutalapati, N.R. Fatigue behavior of 18% Ni maraging steels: A review. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 2486–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, S.; Takahashi, K. Improving fatigue limit and rendering defects harmless through laser peening in additive-manufactured maraging steel. Metals 2022, 12, 10049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, Y.; Yıldırım, H.C.; Kinoshita, K.; Nussbaumer, A. Damage-based assessment of the fatigue crack initiation site in high-strength steel welded joints treated by HFMI. Metals 2022, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, G.A.; Ezeilo, A.N. Residual stress distributions and their influence on fatigue lifetimes. Int. J. Fatigue 2001, 23, 947–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.M.; Slunder, C.J. Physical metallurgy. In The Metallurgy, Behavior, and Application of the 18-Percent Nickel Maraging Steels; National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 1968; Chapter 3. [Google Scholar]

- DeHoff, R.T. Engineering of microstructures. Mater. Res. 1999, 2, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenauer, A.; Brandl, D.; Ressel, G.; Lukas, S.; Gruber, C.; Stockinger, M.; Schnitzer, R. In situ observations of the microstructural evolution during heat treatment of a PH 13-8 Mo maraging steel. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2023, 25, 2300410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.Q.; Xue, H.; Zhao, L.Y.; Fang, X.R. Effects of welded mechanical heterogeneity on interface crack propagation in dissimilar weld joints. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 6593982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppini, N.L.; Dutra, J.C.; Baptista, E.A.; Friaça, C.A.; Ferreira, F.A.A. Effect of grain size on machining strength in an austenitic stainless steel. In Proceedings of the 65th ABM International Congress, 18th IFHTSE Congress and 1st TMS/ABM International Materials Congress, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 26–30 July 2010; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Rack, H.J.; Holloway, P.H. Grain boundary precipitation in 18 Ni maraging steels. Metall. Trans. A 1977, 8, 1873–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, R.D.K. Understanding serrated grain boundaries in the context of strength–toughness combination in ultrahigh-strength maraging steel. Mater. Technol. 2025, 1037, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhao, N.; Liu, R.; Zhang, L.; Wu, W.; Yang, D.; Huang, Y.; Wang, K. The effect of thermal cycle on microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of Co-free maraging steel produced by wire arc additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2024, 332, 118582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, C.; Zhao, L.; Cao, Y.; Ma, C.; Peng, Y.; Tian, Z. Microstructure evolution and strengthening behavior of maraging steel fabricated by wire arc additive manufacturing at different heat treatment processes. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 909, 146804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, P.; Duan, Q.Q.; Zhang, Z.J.; Yang, H.J.; Li, X.W.; Zhang, Z. Optimizing the fatigue strength of 18 Ni maraging steel through ageing treatment. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 707, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, S.; Mortara, L.; Minshall, T. The emergence of additive manufacturing: Introduction to the special issue of Technological Forecasting and Social Change. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 102, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhika, C.; Shanmugam, R.; Ramoni, M.; Bk, G. A review on additive manufacturing for aerospace application. Mater. Res. Express 2024, 11, 022001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakey-Milner, B.; Gradl, P.; Snedden, G.; Brooks, M.; Pitot, J.; Lopez, E.; Leary, M.; Berto, F.; du Plessis, A. Metal additive manufacturing in aerospace: A review. Mater. Des. 2021, 209, 110008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorasani, M.; Ghasemi, A.H.; Rolfe, B.; Gibson, I. Additive manufacturing: A powerful tool for the aerospace industry. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2022, 28, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.Z.; Zhang, S.; Du, Y.; Wu, C.L.; Zhang, C.H.; Sun, X.Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, J. Development and characterization of a novel maraging steel fabricated by laser additive manufacturing. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 891, 145975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindič, M.; Klobčar, D.; Nagode, A.; Mole, N.; Žužek, B.; Vuherer, T. Heat treatment optimisation of 18 % Ni maraging steel produced by DED-ARC for enhancing mechanical properties. J. Adv. Join. Process. 2025, 11, 100312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krassenstein, B. New Airbus A350 XWB Aircraft Contains over 1,000 3D Printed Parts. 3D PrintCom: The Voice of 3D Printing. 2015. Available online: https://3dprint.com/63169/airbus-a350-xwb-3d-print/ (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Huang, G.; Wei, K.; Deng, J.; Zeng, X. High power laser powder bed fusion of 18Ni 300 maraging steel: Processing optimization, microstructure and mechanical properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 856, 143983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Lu, X.; Yang, H.; Niu, X.; Zhang, L.; Xie, X. Processing optimization, microstructure, mechanical properties and nanoprecipitation behavior of 18Ni 300 maraging steel in selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 830, 142334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Lin, W.; Wei, P.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, K.; Yang, B.; Li, W. Effect of heat treatments on the microstructure and properties of 18Ni 300 maraging steel produced by selective laser melting. Materials 2025, 18, 2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güney, B.; Erden, M. Effect of heat treatments on microstructural and tribological properties of 3D printed 18Ni-300 maraging tool steel made by selective laser sintering process. Sci. Sinter. 2024, 26, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, K.; Hovig, E.W.; Sørby, K.; Berto, F. Directional fatigue behaviour of maraging steel grade 300 produced by laser powder bed fusion. Int. J. Fatigue 2021, 149, 106229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutua, J.; Nakata, S.; Onda, T.; Chen, Z.C. Optimization of selective laser melting parameters and influence of post heat treatment on microstructure and mechanical properties of maraging steel. Mater. Des. 2018, 139, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Qu, B.; Tao, Y.; Zeng, W.; Chen, B. The combination of direct aging and cryogenic treatment effectively enhances the mechanical properties of 18Ni 300 by selective laser melting. Metals 2025, 15, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subashini, L.; Prabhakar, K.V.P.; Ghosh, S. Joint design influence on hybrid laser arc welding of maraging steel. Weld. World 2024, 68, 1751–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zhang, H.; Tan, H.; Duan, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, D.; Peng, Y.; Wang, K. Effect of aging and deep cryogenic treatment on enhancing strength-ductility synergy in PA-DEDed Co-free maraging steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 945, 148994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subashini, L.; Prabhakar, K.V.P.; Gundakaram, R.C.; Ghosh, S.; Padmanabham, G. Single pass laser-arc hybrid welding of maraging steel thick sections. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2016, 31, 1699–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzer, R.; Schober, M.; Zinner, S.; Leitner, H. Effect of Cu on the evolution of precipitation in an Fe-Cr-Ni-Al-Ti maraging steel. Acta Mater. 2010, 58, 4279–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobryn, P.A.; Ontko, N.R.; Perkins, L.P.; Tiley, J.S. Additive Manufacturing of Aerospace Alloys for Aircraft Structures; Report No. ADA 521726; Air Force Research Laboratory, Materials & Manufacturing Directorate: Wright-Patterson AFB, OH, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pant, M.; Pidge, P.; Nagdeve, L.; Kumar, H. A review of additive manufacturing in aerospace application. Rev. des Compos. et des Mater. Av. 2021, 31, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, J. Laser welding of metals for aerospace and other applications. In Welding and Joining of Aerospace Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 75–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, B.; Chandrasekaran, M. Investigation on welding characteristics of aerospace materials—A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 5379–5384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, B.; Manoharan, M.; Natarajan, A.; Rao Muktinutalapati, N.; Madhusudhan Reddy, G. Development of a low heat-input welding technique for joining thick plates of 250 grade maraging steel to fabricate rocket motor casings. Mater. Lett. 2022, 326, 132984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad Rambabu, N.; Eswara Prasad, V.V.K.; Wanhill, R.J.H. Aerospace Materials and Material Technologies, Volume 1: Aerospace Material Technologies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, T. Advanced Welding Methods and Equipment, 1st ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Salem, K.; Cipolla, V.; Palaia, G.; Binante, V.; Zanetti, D. A physics-based multidisciplinary approach for the preliminary design and performance analysis of a medium range aircraft with box-wing architecture. Aerospace 2021, 8, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spodniak, M.; Hovanec, M.; Korba, P. Jet engine turbine mechanical properties prediction by using progressive numerical methods. Aerospace 2023, 10, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandoli, B.; de Geus, A.R.; Souza, J.R.; Spadon, G.; Soares, A.; Rodrigues, J.F. Aircraft fuselage corrosion detection using artificial intelligence. Sensors 2021, 21, 4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korompili, G.; Mußbach, G.; Riziotis, C. Structural Health Monitoring of Solid Rocket Motors: From Destructive Testing to Perspectives of Photonic-Based Sensing. Instruments 2024, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, M.; Ambrogiani, P.; Raiola, V.; Bocchetto, F.; Tirelli, T.; Castaldo, M. Design and Qualification of an Additively Manufactured Manifold for Aircraft Landing Gears Applications. Aerospace 2023, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strakosova, A.; Průša, F.; Jiříček, P.; Houdková, J.; Michalcová, A.; Vojtěch, D. High-Temperature Exposure of the High-Strength 18Ni-300 Maraging Steel Manufactured by Laser Powder Bed Fusion: Oxidation, Structure and Mechanical Changes. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 859–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinado, G.; Carvalho, C.; Jardini, A.; Souza, E.; Avila, J.A.; Baptista, C. Microstructural and Mechanical Characterization of Additively Manufactured Parts of Maraging 18Ni 300M Steel with Water and Gas Atomized Powders Feedstock. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 130, 12686–12702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Shen, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, C.; Chen, X.; Jiang, M.; Liu, H.; Tian, Y. Fatigue Properties of Thick Section High Strength Steel Welded Joint by Hybrid Fiber Laser-Arc Welding. J. Laser Appl. 2024, 36, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunprakash, R.; Jose, B.; Manikandan, M.; Arivazhagan, N.; Muktinutalapati, N.R. Innovative D-Process MIG Welding for Enhanced Performance of Thick Sections of MDN 250 in Aerospace Applications. Weld. Int. 2025, 39, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerezo, P.M.; Aguilera, J.A.; Garcia-Gonzalez, A.; Lopez-Crespo, P. Tomography of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Maraging Steel. Materials 2024, 17, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasques, C.M.A.; Cavadas, A.M.S.; Abrantes, J.C.C. Technology overview and investigation of the quality of a 3D-printed maraging steel demonstration part. Mater. Sci. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 4, 025040002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Xie, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, X.; Peng, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, J.; Huang, F.; Zhang, S. Effect of solution-aging treatment on the microstructure and hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility in laser-powder bed fusion maraging steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 37, 5593–5606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.P.; Santos, T.G.; Miranda, R.M. Revisiting fundamental welding concepts to improve additive manufacturing: From theory to practice. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2020, 107, 100590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Manufacturing Process and Material | Microstructural Observation | Mechanical Properties | Remarks | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength (MPa) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Elongation % | Hardness (HVN) | |||||

| 1 | Fiber laser beam welding and TIG welding of maraging steel with AISI 4140 | Narrower fusion zone and HAZ in laser welding with fine and coarse grains relative to TIG | 1494 | 1215 | 2.2 | 545 | Laser welding exhibits higher efficiency in weld joints compared to TIG. Rapid cooling reduces the width of the HAZ and fusion zone, thereby improving mechanical properties. | [16] |

| 2 | Heat treatment and Yb-laser-welded maraging steel | Two HAZs, namely HAZ (austenitized) and HAZ (aged during welding) | 1440 | 1350 | 7.1 | 530 | Post-weld aging helps achieve uniformity in the first and second HAZs, thereby increasing mechanical strength. | [9] |

| 3 | CO2 laser welding of maraging steel | The change in scanning speed affects the fusion zone area. As the speed increases, the fusion zone grains tend to be finer. | 1520 | - | 10 | 300 | As the speed increases from 0.5 to 1 m/min, the strength increases rapidly and remains constant until it reaches 2.5 m/min, and then it decreases at 3 m/min. | [18] |

| 4 | Laser hybrid welding of maraging steel | Wine cup-shaped fusion zone with cellular and dendritic formations | 1721 | 1682 | 4 | 420 | Aging treatment improves both hardness and strength through the homogenization of microstructures. | [24] |

| 5 | Post-weld aging treatment of laser-welded maraging steel | Coarse equiaxed martensite grains at the weld zone, moving away from the weld zone, become finer. | 1513 | 1494 | 2.4 | 470 | Aging in a temperature range of 420–460 °C enhances the hardness at HAZ and fusion zone, and thus increases tensile properties. | [25] |

| 6 | Notched tensile testing of maraging steel weldment in air and hydrogen | The segregation of Ti and Mo at interdendritic boundaries yields the formation of austenite pools | 1597 | - | - | 416 | As the aging temperature increases, the amount of reverted austenite increases. | [26] |

| 7 | Maraging 300 steel welded by laser, subjected to plasma nitriding treatment | The microstructure depicts fusion zone formation and HAZ with reduced hardness, and further aging improves hardness | 1891 | 1607 | 8.8 | 355 | Nitriding tends to enhance the tensile strength of laser-welded maraging steel, and further aging improves its mechanical properties. | [27] |

| 8 | Role of copper in laser-welded maraging steel | The addition of a copper layer reduced the fraction of reverted austenite in the grain boundary from 6.8% to 3.7%, and the same increase occurred in the matrix of martensite | 1646 | 1507 | - | - | Aging ε-Cu precipitates adds the benefit of strength; Cu lowers the critical driving force in phase transformation, thus promoting austenite formation in the matrix. | [28] |

| 9 | Effect of post-welding heat treatment on maraging steel welded by gas tungsten arc welding using filler materials | The weld zone becomes coarser due to the excess of heat input by multi-pass welding, along with two HAZs formed, in which the second HAZ was aged during welding | 1790 | 1675 | 6.8 | 530 | Aging at 485 °C, followed by homogenization at 1099 °C, assisted in producing austenite-free lath martensite, as homogenization led to homogeneous structures prior to aging. | [29] |

| Material | Aging Parameter | Precipitate Phase | Precipitate Spacing/Size | Strengthening Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-free, 11.5–12% Ni and variable Ti and Al maraging steels | 510 °C for 16 h | η-Ni3Ti and β-NiAl | 5–20 nm mean free distance | σppt = 1000 MPa, relative to Ti and Al concentration | [41] |

| 18 Ni 350 maraging steel | 430 and 475 °C for 6.5 h | Ni3 (Ti, Mo) | Size varies from 3 to 15 nm | 653–697 VHN | [42] |

| 13 Ni maraging steel (studying the influence of Mo content) | 480 to 500 °C for 3, 4, 5, and 6 h | Ni3Mo to Fe2 (Mo, Ti) laves formation | 3 to 14 nm | Peak hardness reaches 798 VHN for a base composition of Mo | [22] |

| Fe-Ni-Mn-Ti-Al | Solution treating at 1100 °C and aging at 550 °C | (Ni, Fe)3 Ti (plate to rod morphology) and (Ni, Fe)3(Al, Mn) | Less than 10 nm | Early precipitation increases of 200–300 MPa strength | [43] |

| 18-Ni maraging steel | 450–500 °C | Primary Ni3 Mo and secondary Ni3Ti | 5–20 nm | Study of precipitates supporting strengthening | [44] |

| Material | Aging/Heat Treatment | Reverted Austenite (%vol.) | Effect on Mechanical Properties | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18Ni-350 maraging steel | 520 °C over aging | 18% | Hardness and strength reduce, but ductility/toughness improves | [58] |

| 18Ni-350 maraging steel | 560 °C over aging | 25% | Further reduction in hardness, but larger ductility | [58] |

| 18Ni-350 maraging steel | 600 °C over aging | 37% | Substantially low strength and hardness; coarse RA reduces strength | [58] |

| 18Ni-350 maraging steel | 570 °C for 4 h | 10% | A small fraction of RA for modest softening | [59] |

| 18Ni-300 maraging steel | 570 °C for 3 h | Up to 30% (for 3 h) | The fraction of RA grows with time, but the strength drops. | [60] |

| 18Ni-350 maraging steel | 600–700 °C, short aging of 1800 s | 54.5% to 60.9% | High-temperature short aging can still produce noticeable RA. The prior cold rolled shows a different RA fraction | [61] |

| 18Ni-250 maraging steel weldments | Post-weld heat treatment at 480 °C (1 to 360 min) | 2.5% after 15 min | Hardness at the weld zone varies from 390 to 520 VHN for 6 h | [62] |

| Mn-based maraging steel (10–12% Mn) | Aged 460 to 540 °C | 4% (10 min, 10% Mn) and 9% (12% Mn)—increases with time/composition | Mn segregation with lath-like RA. RA growth is slow due to low Mn diffusivity and toughness improvement | [46] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Behl, B.; Dong, Y.; Pramanik, A.; Bandyopadhyay, T.K. Evolution of Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of Laser-Welded Maraging Steel for Aerospace Applications: The Past, Present, and Future Prospect. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120394

Behl B, Dong Y, Pramanik A, Bandyopadhyay TK. Evolution of Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of Laser-Welded Maraging Steel for Aerospace Applications: The Past, Present, and Future Prospect. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2025; 9(12):394. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120394

Chicago/Turabian StyleBehl, Bharat, Yu Dong, Alokesh Pramanik, and Tapas Kumar Bandyopadhyay. 2025. "Evolution of Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of Laser-Welded Maraging Steel for Aerospace Applications: The Past, Present, and Future Prospect" Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 9, no. 12: 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120394

APA StyleBehl, B., Dong, Y., Pramanik, A., & Bandyopadhyay, T. K. (2025). Evolution of Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of Laser-Welded Maraging Steel for Aerospace Applications: The Past, Present, and Future Prospect. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 9(12), 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120394