Effects of Multiple Quenching Treatments on Microstructure and Hardness of O2, D2, and D3 Tool Steels

Abstract

1. Introduction

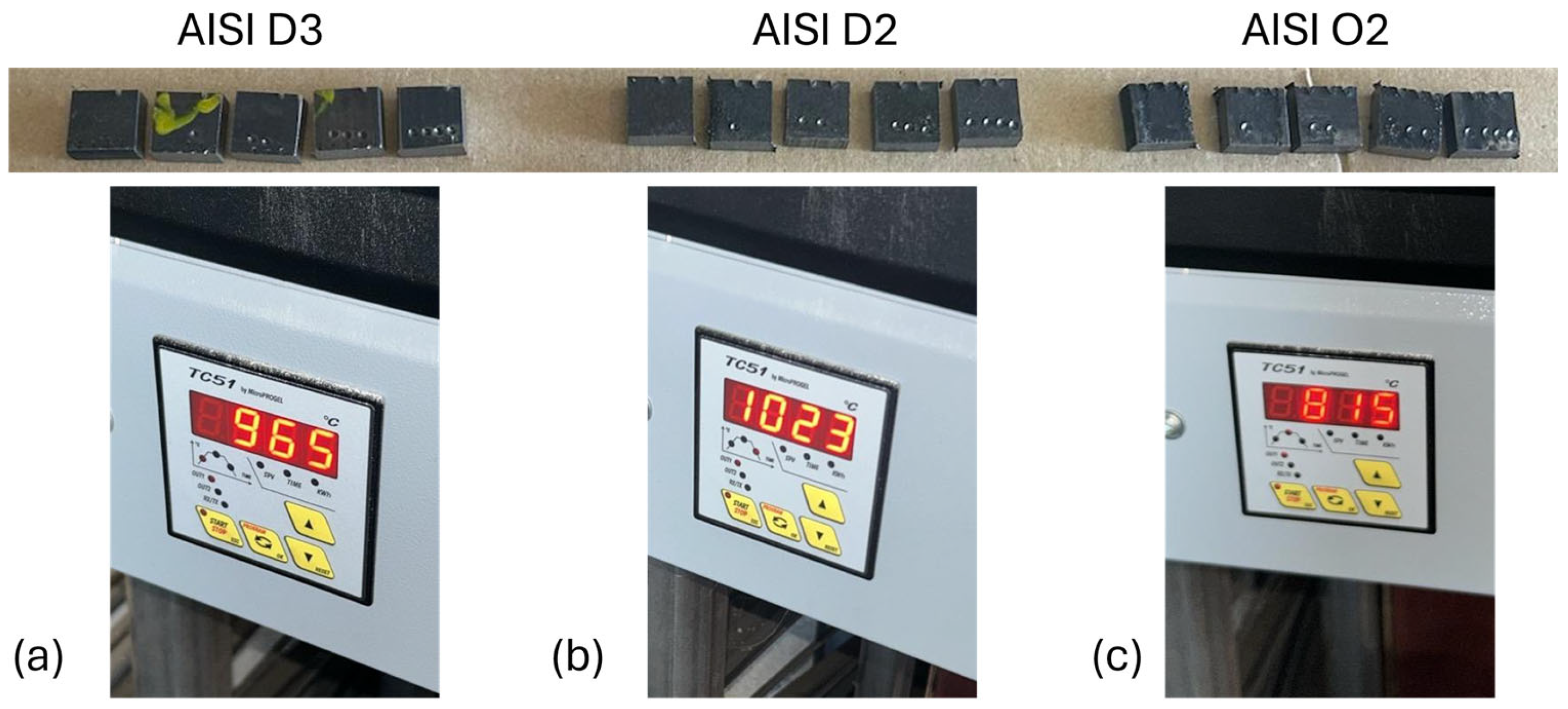

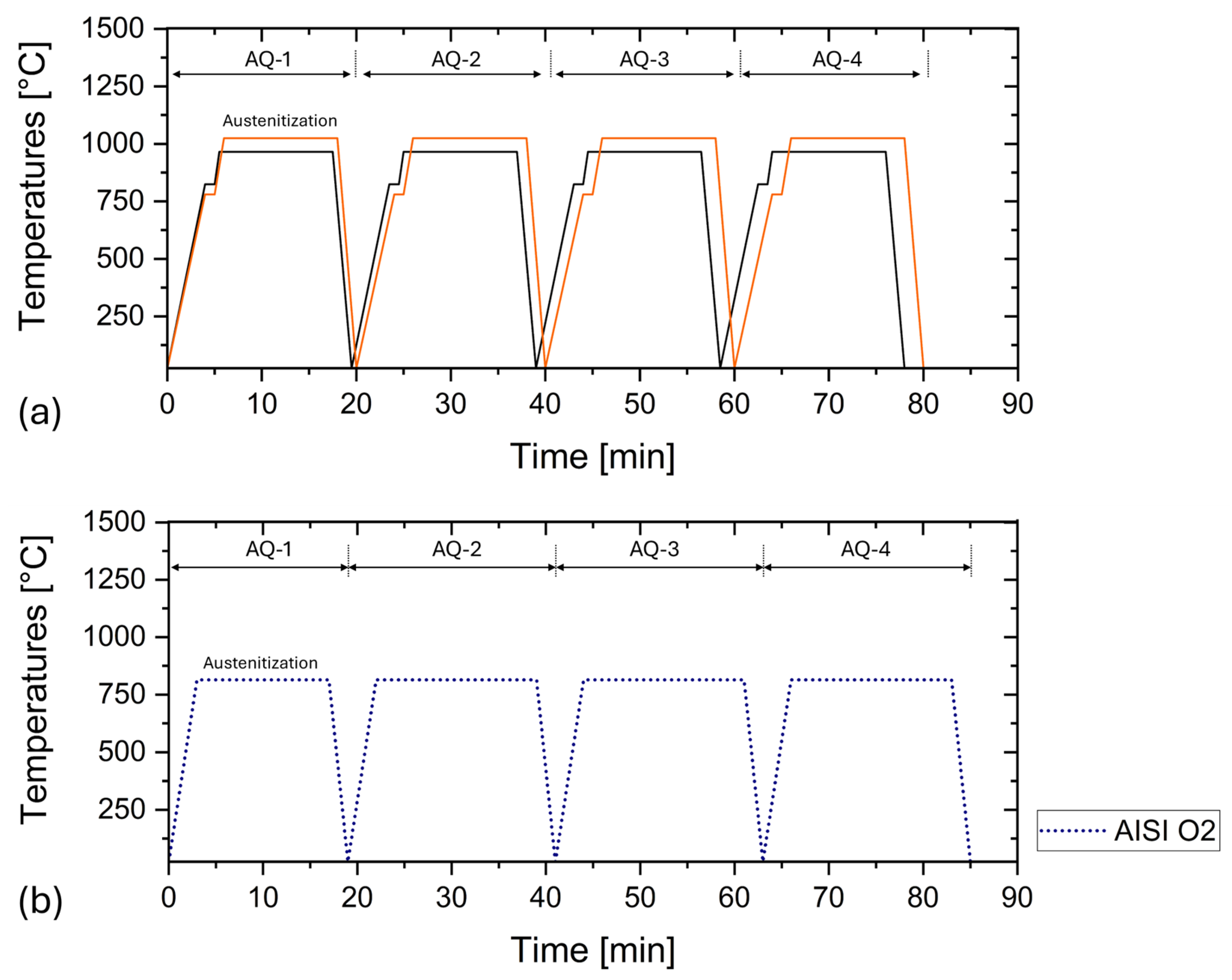

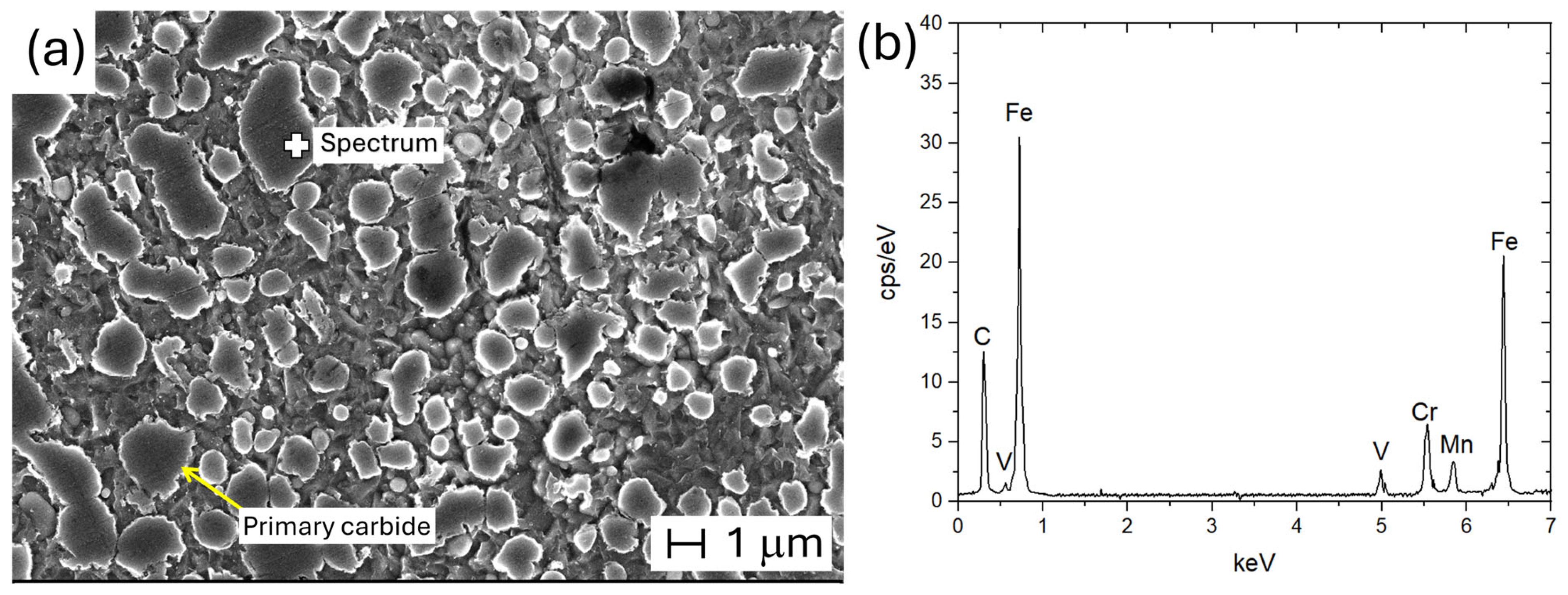

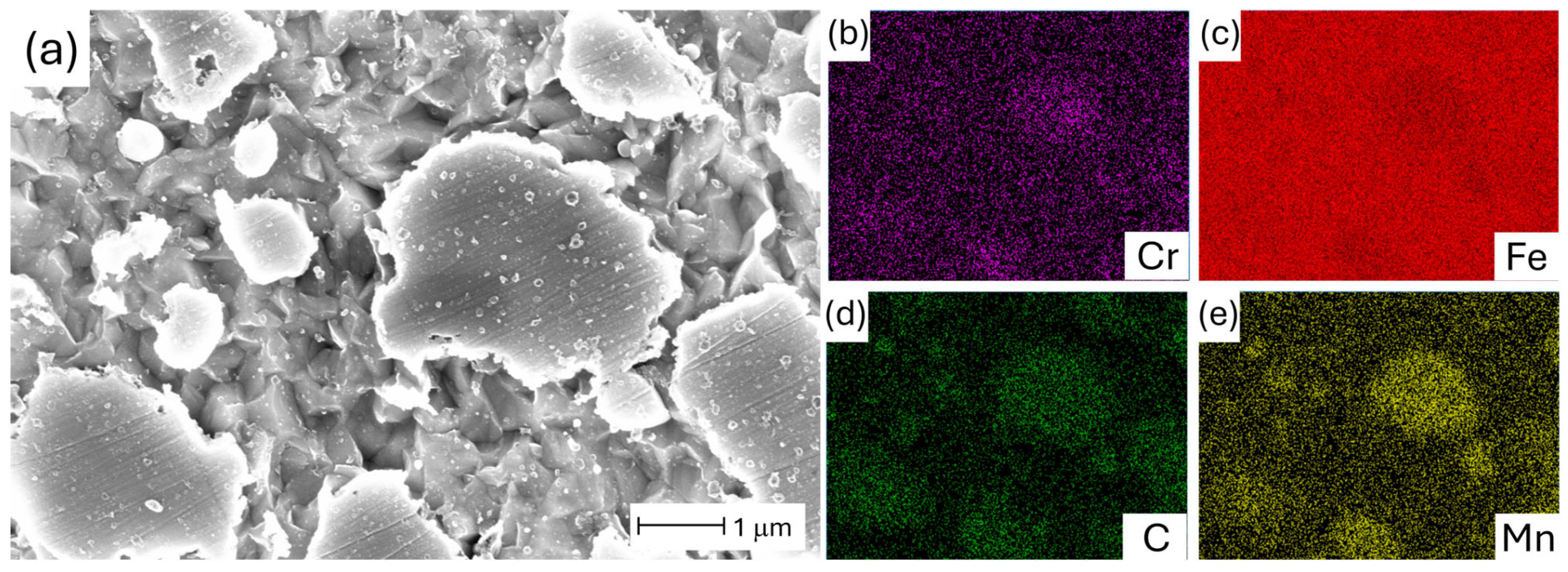

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Conclusions

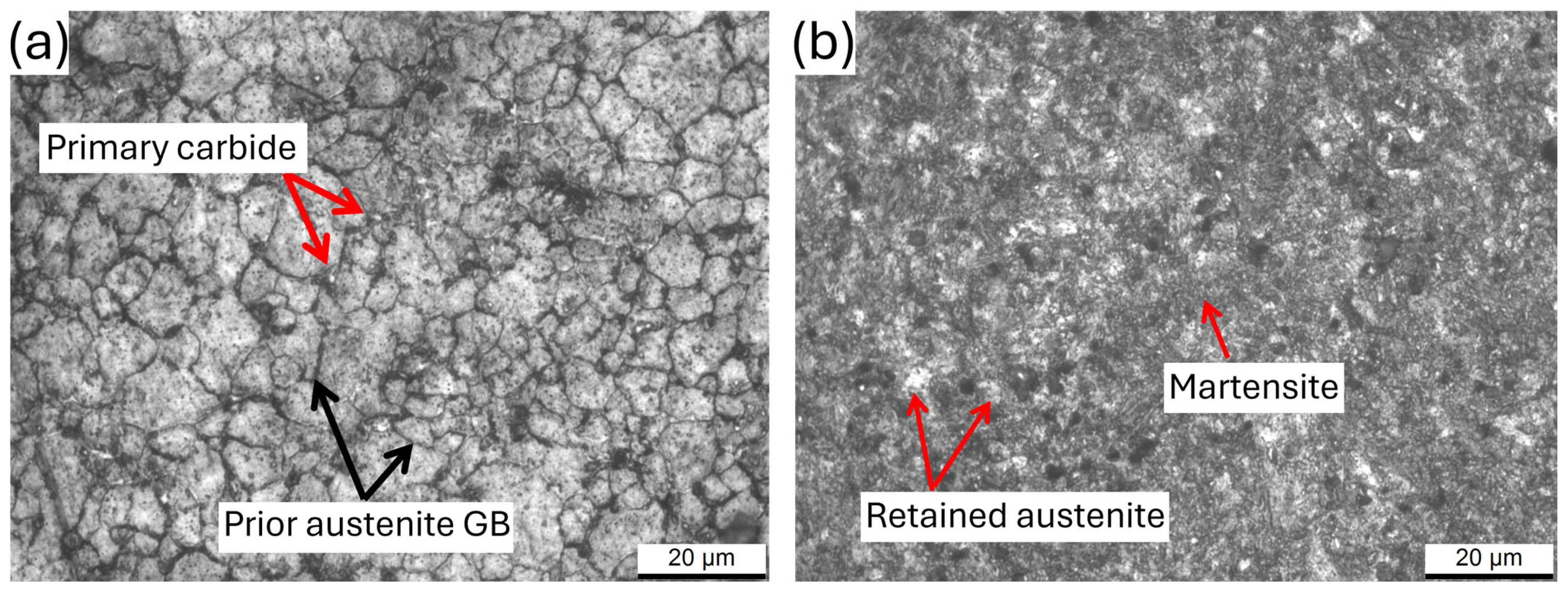

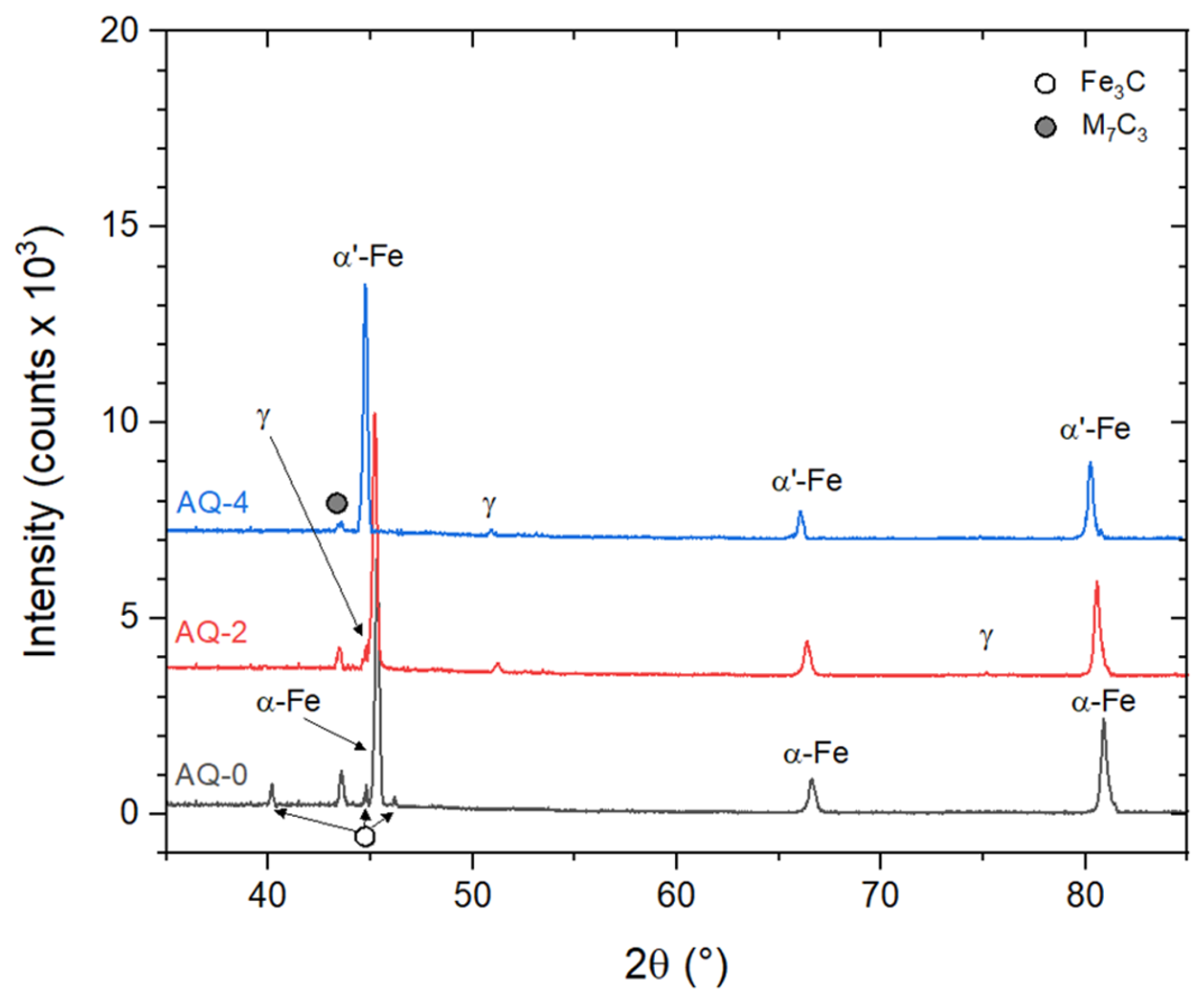

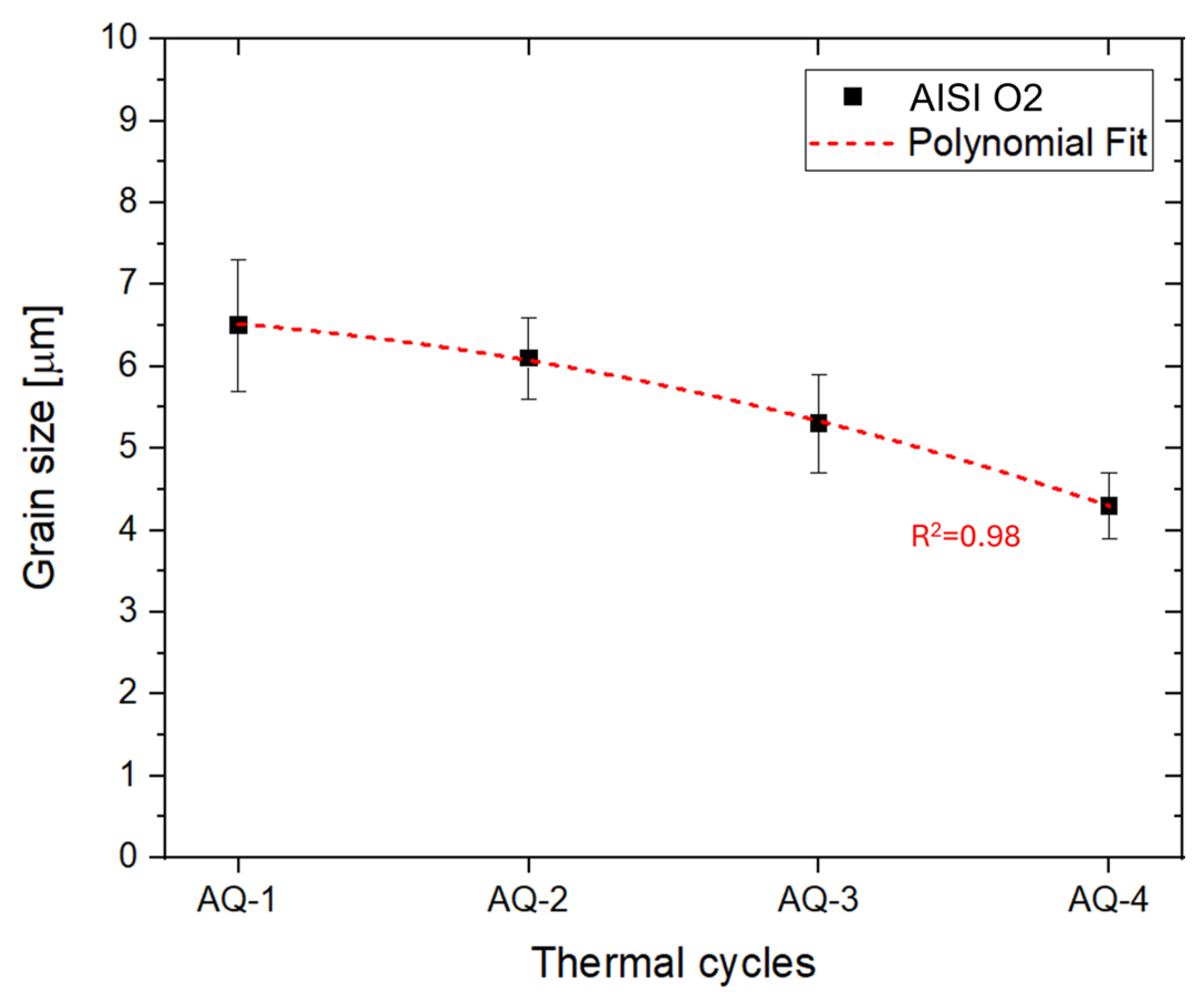

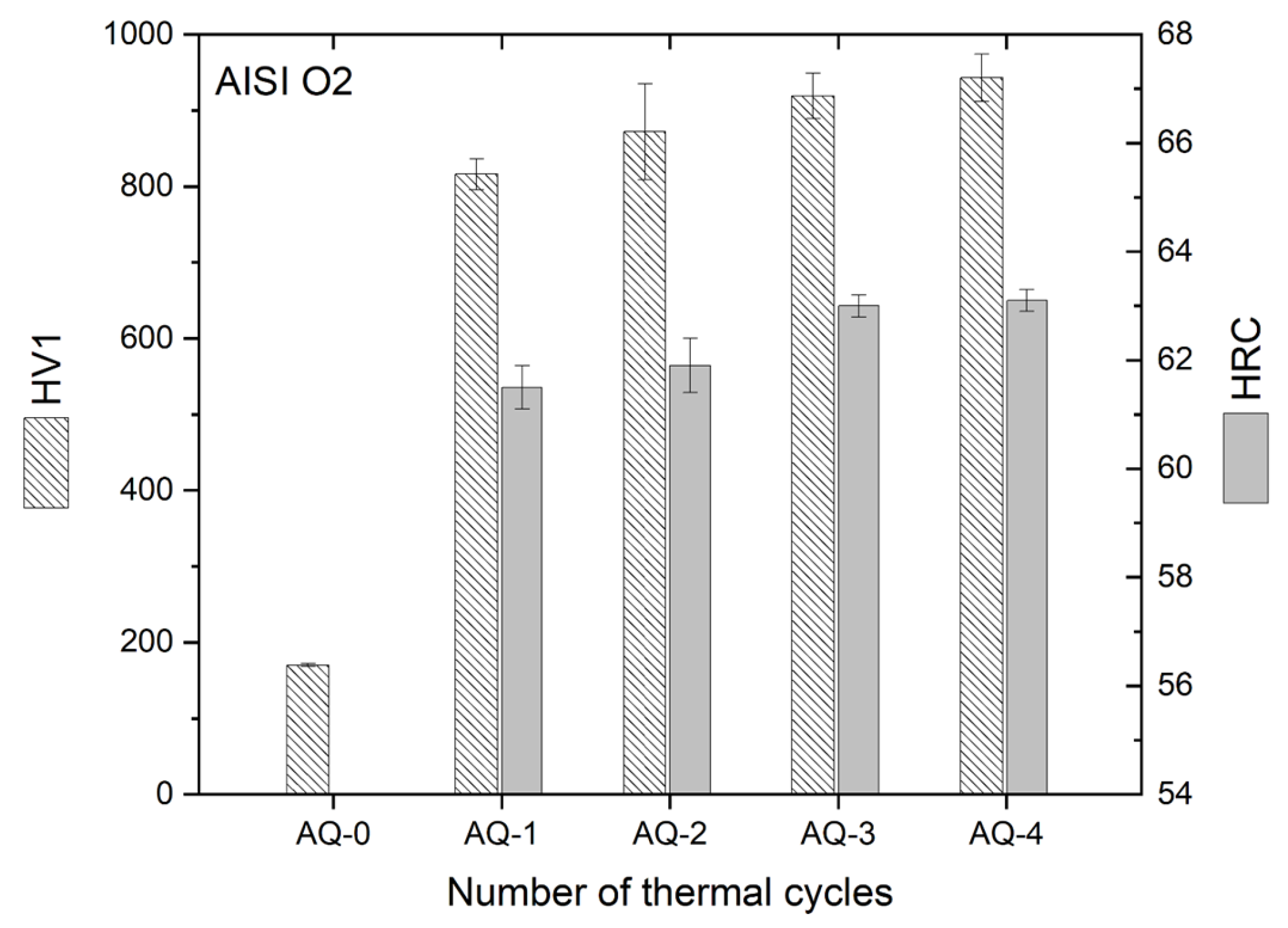

- Repeated AQ cycles promoted progressive grain refinement in AISI O2 steel, reducing the mean prior austenitic grain size from (6.5 ± 0.8) μm to (4.3 ± 0.4) μm. This refinement, combined with carbide dissolution (after AQ-2), martensite formation, and a reduction in retained austenite, resulted in a continuous hardness increase up to ~ 950 HV1 (63 HRC).

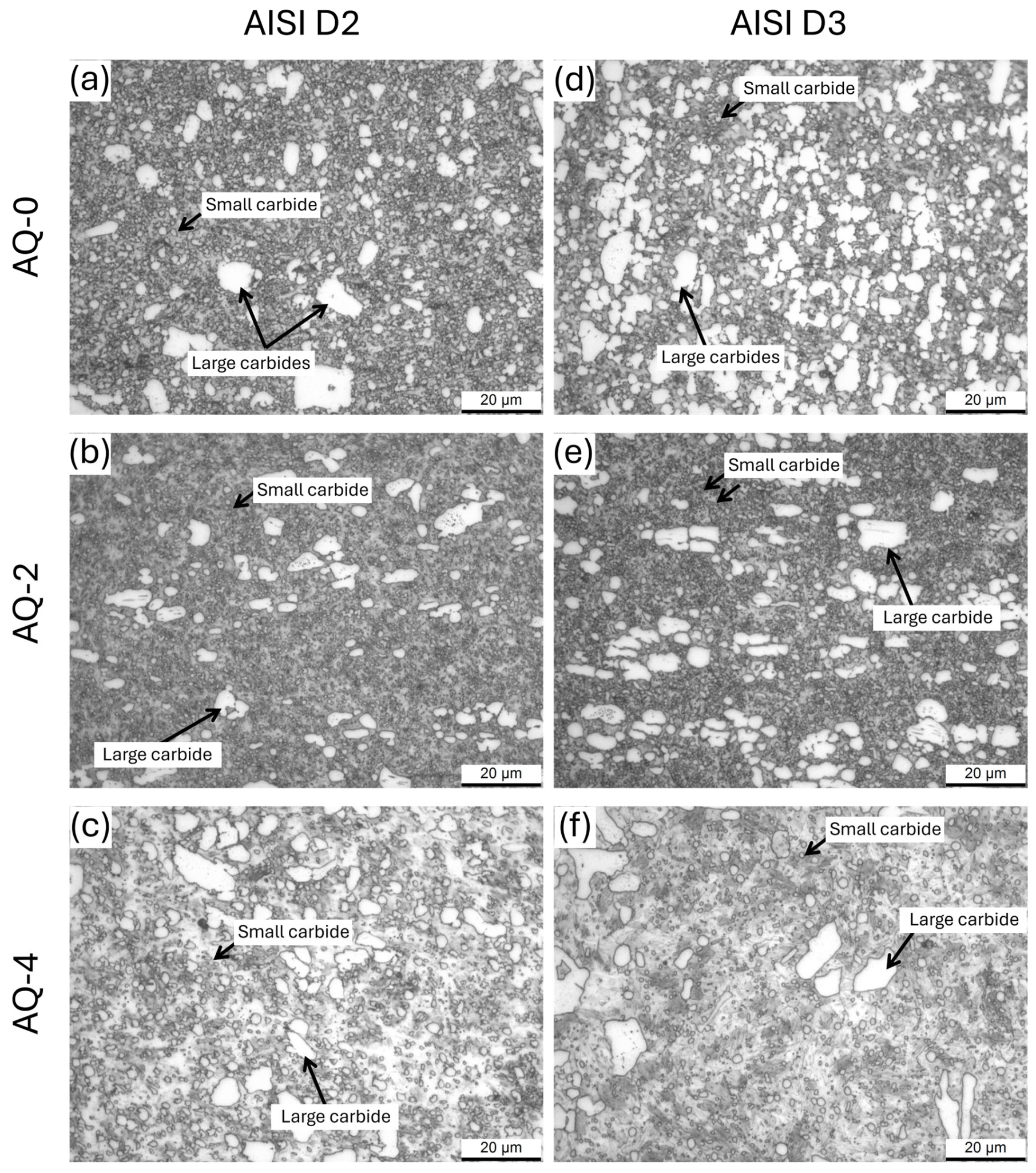

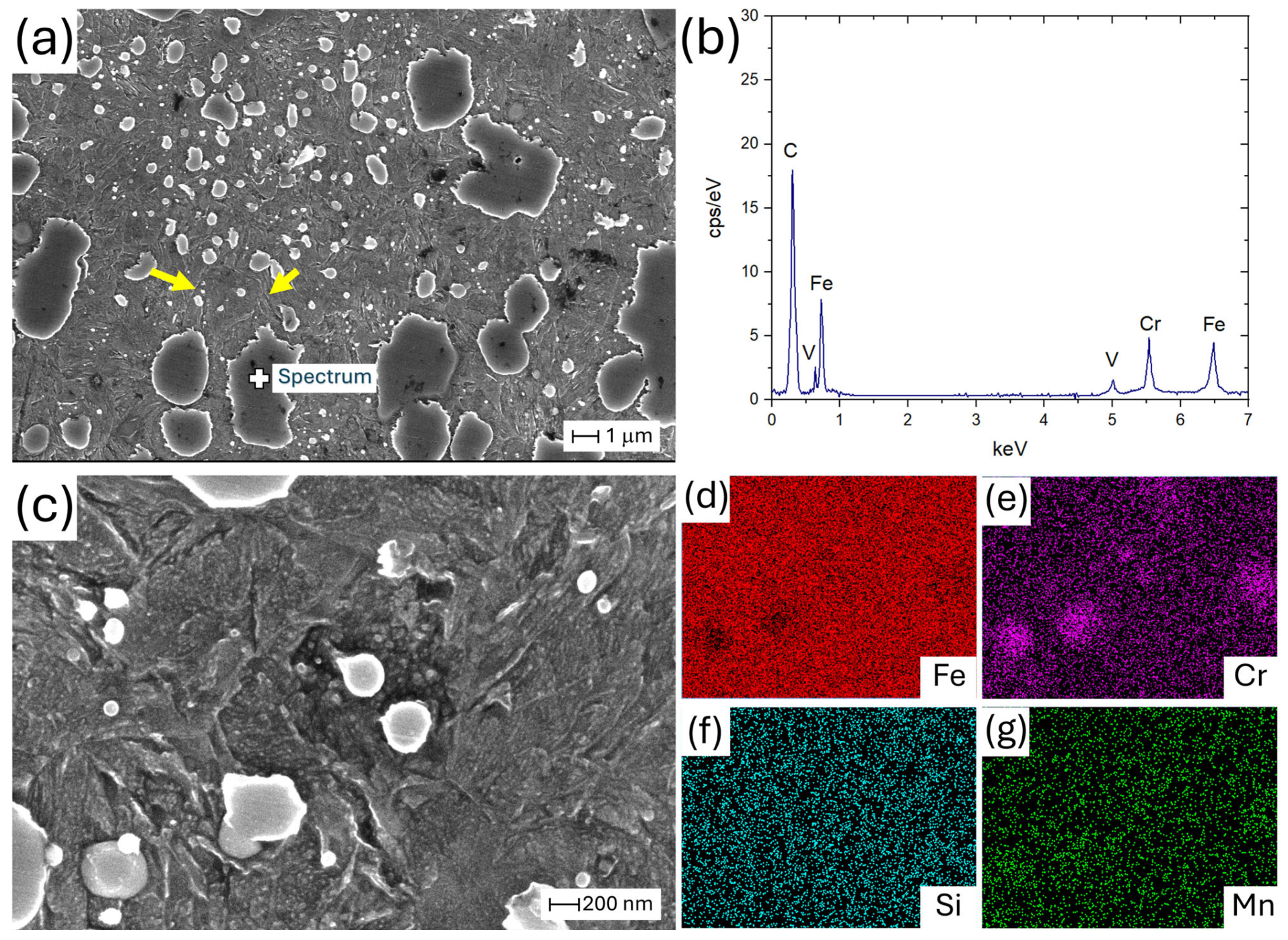

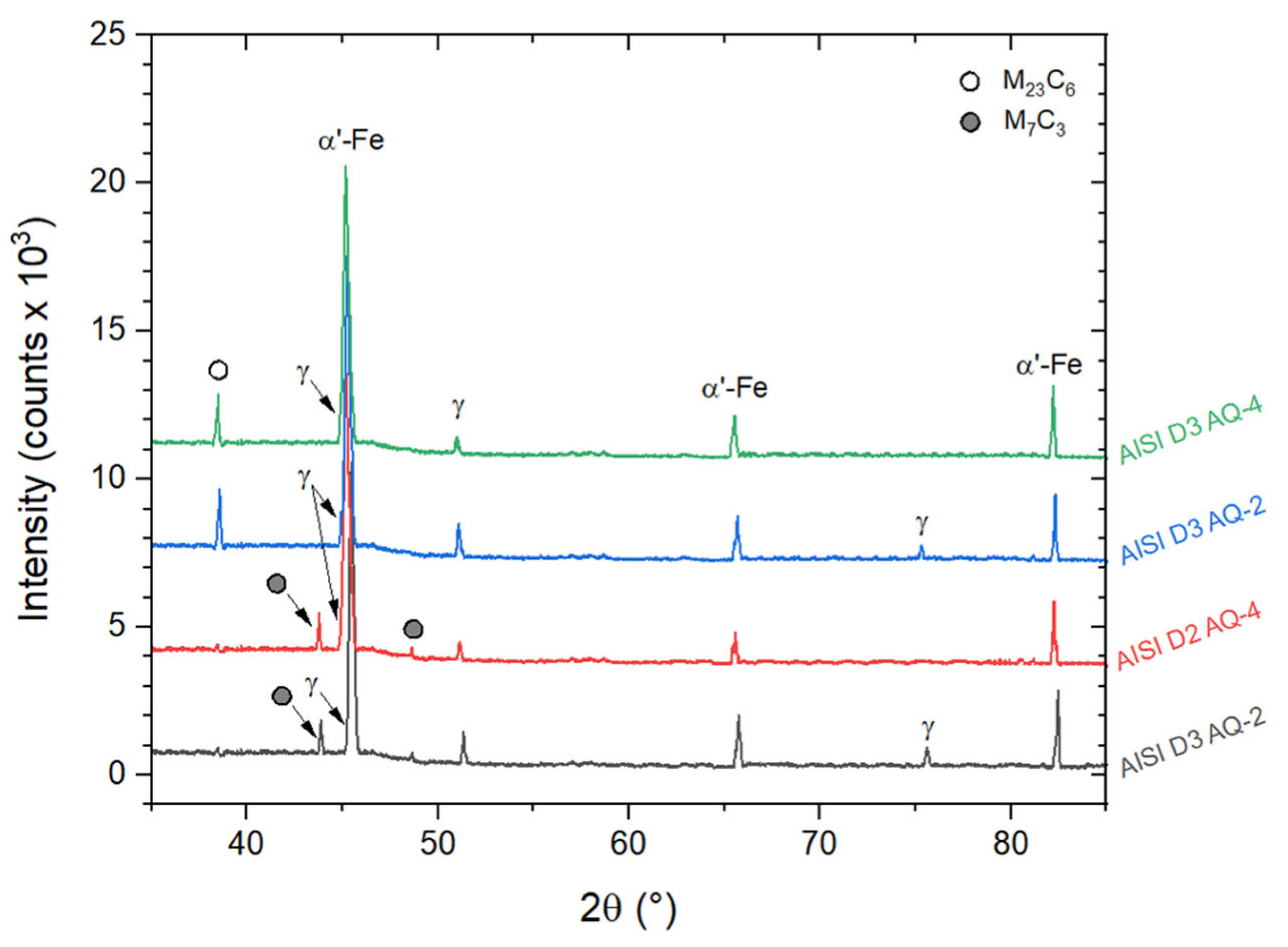

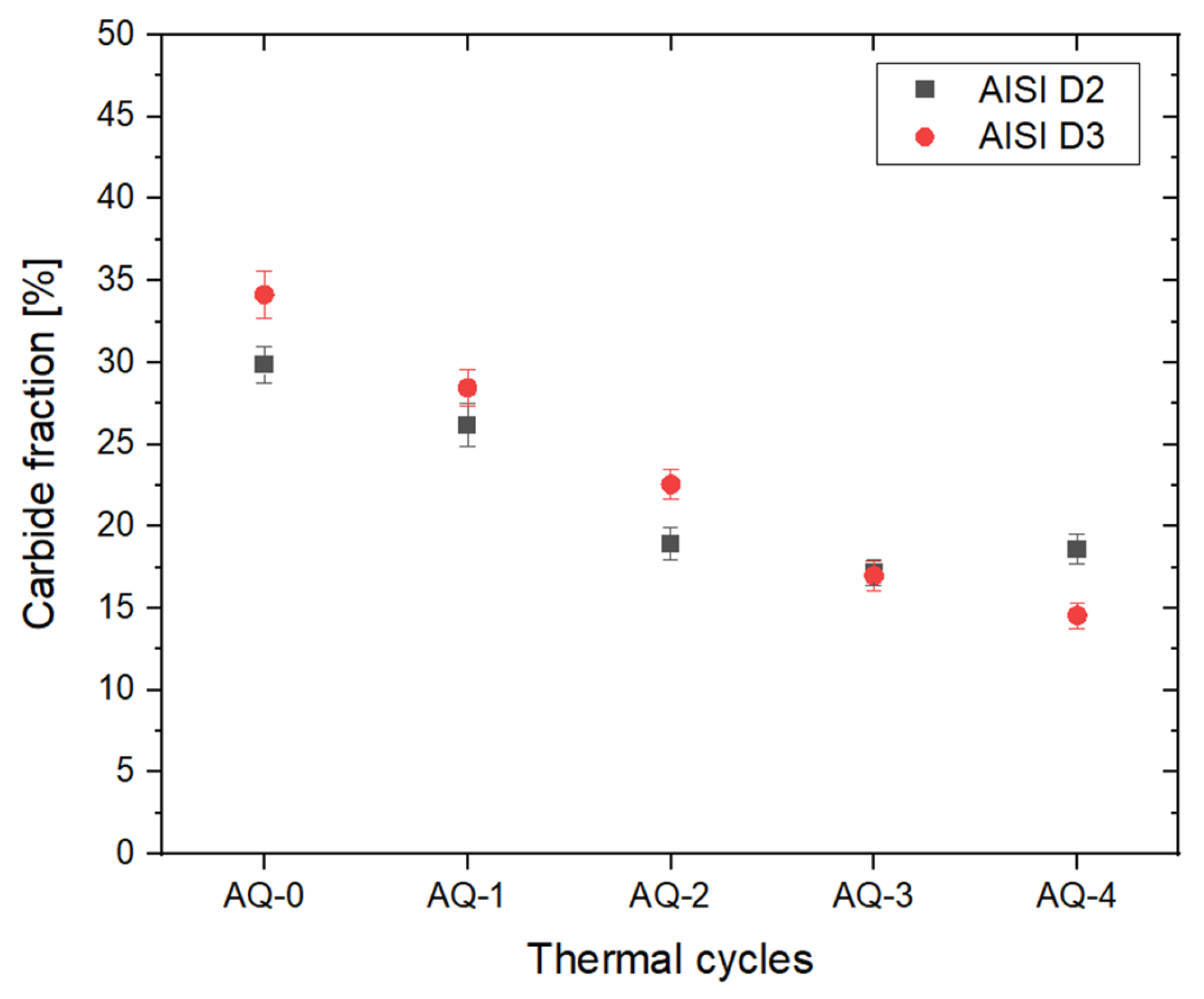

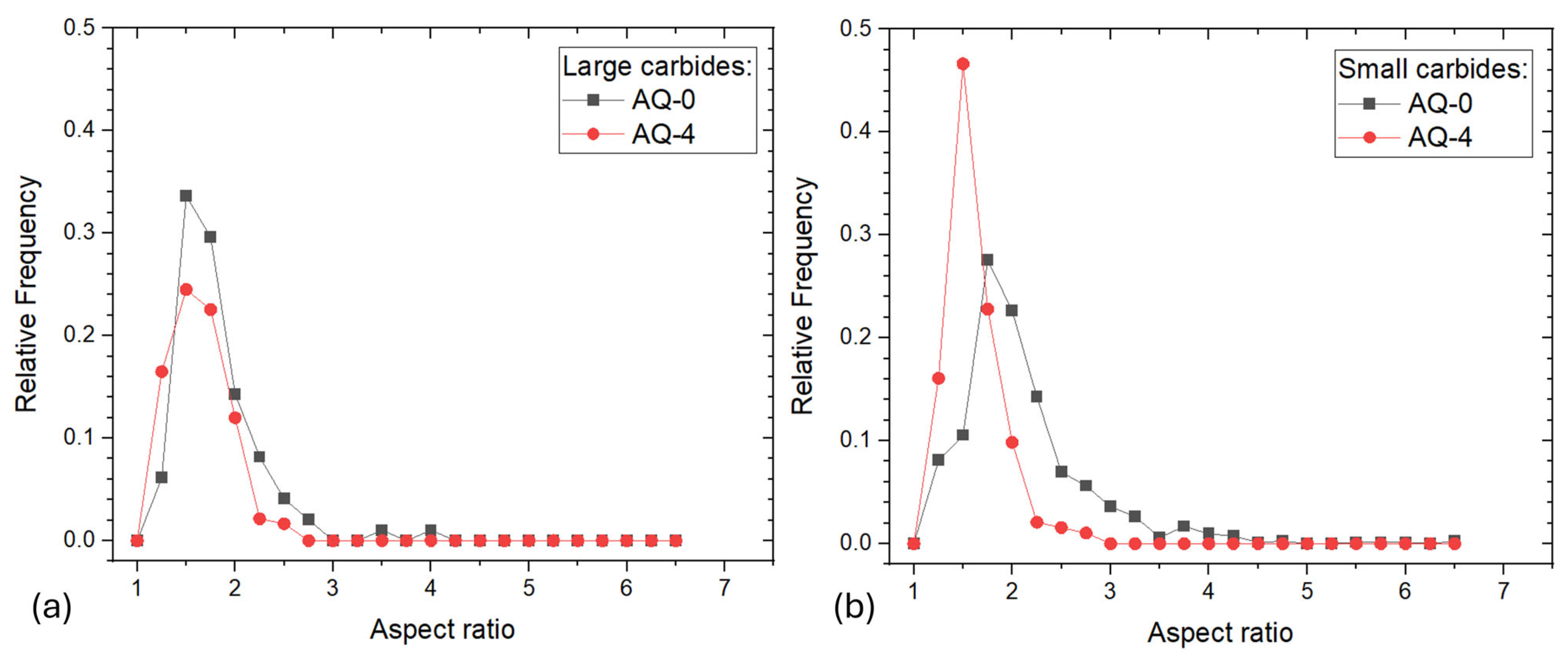

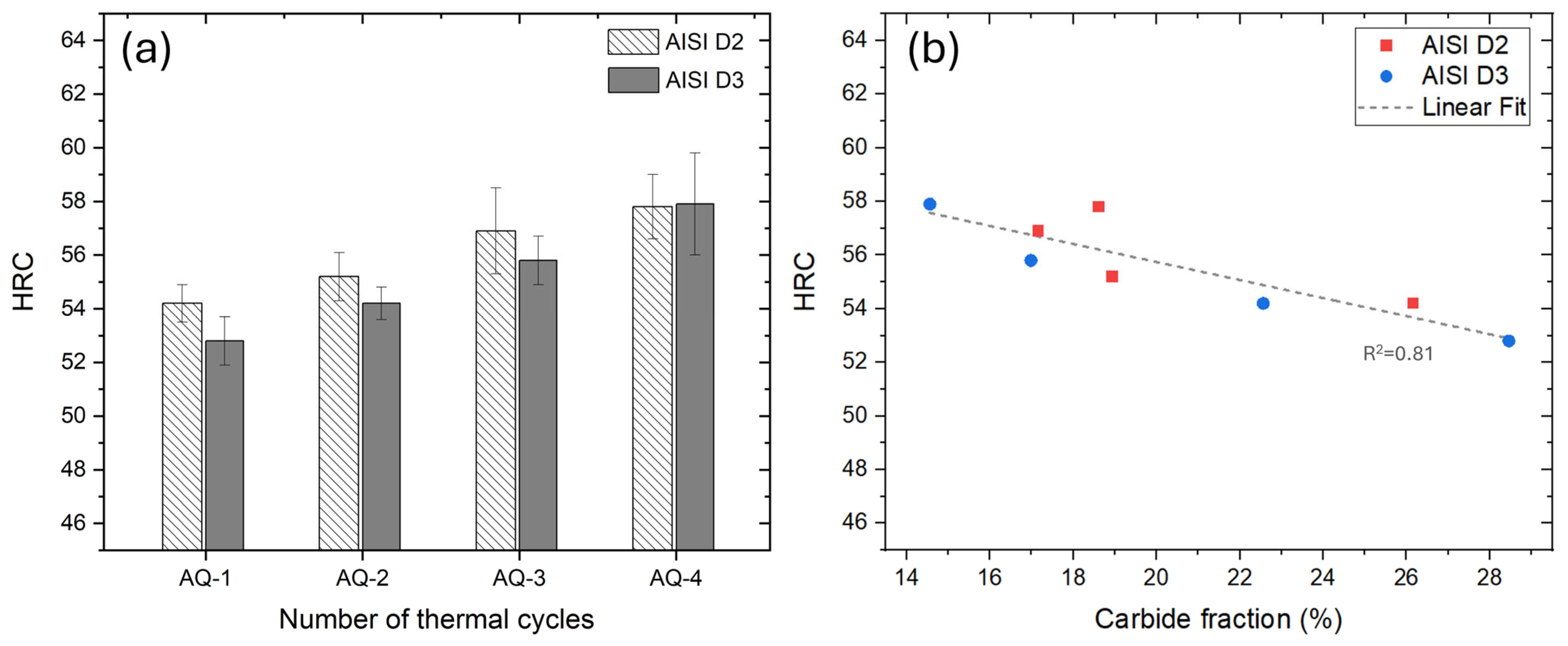

- In AISI D2 and D3 steels, the AQ treatments induced both carbide dissolution and their spheroidization. In AISI D2, partial coarsening was observed after AQ-3, likely due to the complete dissolution of the smallest carbides, while AISI D3 exhibited a monotonic reduction in both the size and volume fraction of the M23C6 carbides.

- A linear correlation was established between carbide dissolution and the hardness for both D2 and D3 steels. Increased carbide dissolution enhanced the matrix’s hardness, leading to a Rockwell hardness of ~58 HRC.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alza, V.A. Effect of Multiple Tempering on Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of Ledeburitic Tool Steel AISI D3. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. IJRTE 2020, 8, 2514–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.N.; Omar, M.Z.; Jameel Al-Tamimi, A.N.; Sultan, H.S.; Abbud, L.H.; Al-Zubaidi, S.; Abdullah, O.I.; Abdulrazaq, M. Microstructural and Mechanical Characterization of Ledeburitic AISI D2 Cold-Work Tool Steel in Semisolid Zones via Direct Partial Remelting Process. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2022, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhang, Y.F.; Yu, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.L.; Cao, W.Q. Influence of Multiple Quenching Treatment on Microstructure and Tensile Property of AISI M50 Steel. Mater. Lett. 2023, 340, 134175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-Y.; Kim, H.; Son, D.; Kim, C.; Park, S.K.; Lee, T.-H. Hot-Worked Microstructure and Hot Workability of Cold-Work Tool Steels. Mater. Charact. 2018, 135, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kang, J.-Y.; Son, D.; Lee, T.-H.; Cho, K.-M. Evolution of Carbides in Cold-Work Tool Steels. Mater. Charact. 2015, 107, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salunkhe, S.; Fabijanic, D.; Nayak, J.; Hodgson, P. Effect of Single and Double Austenitization Treatments on the Microstructure and Hardness of AISI D2 Tool Steel. Mater. Today Proc. 2015, 2, 1901–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celtik, C.; Ayhan, I.I.; Yurekturk, Y. Effect of Double Austenitization and Pre-Annealing Heat Treatment on the Microstructural and Mechanical Properties of QT 41Cr4 Steel. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2023, 76, 2845–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Song, R.; Quan, S.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Cai, C.; Wen, E. A Fe-Cr-C Steel Based on Gradient Scale Precipitation Hardening: Hardening and Toughening Mechanism of Multistage Heat Treatment. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 946, 169355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colla, V.; Branca, T.A. Sustainable Steel Industry: Energy and Resource Efficiency, Low-Emissions and Carbon-Lean Production. Metals 2021, 11, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouhara, H.; Khordehgah, N.; Almahmoud, S.; Delpech, B.; Chauhan, A.; Tassou, S.A. Waste Heat Recovery Technologies and Applications. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2018, 6, 268–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchner, K.; Uhlig, J. Discussion on Energy Saving and Emission Reduction Technology of Heat Treatment Equipment. BHM Berg Hüttenmännische Monatshefte 2023, 168, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Q.; Wu, X.; Zhuo, J.; Li, C.; Li, C.; Cao, H. An Incremental Data-Driven Approach for Carbon Emission Prediction and Optimization of Heat Treatment Processes. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 72, 106320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermawan, F.H.; Mochtar, M.A. Effect of Austenitizing Temperature on Microstructure, Amount of Retained Austenite, and Hardness of AISI O1 Tool Steel. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Quality in Research (Qir) 2021 in Conjunction with the 6th ITREC 2021 and the 2nd CAIC-SIUD, Depok, Indonesia, 13–15 October 2021; p. 070001. [Google Scholar]

- Çivici, M.; Özer, M.; Altuntaş, G.; Yilmaz, T.; Shelar, A.R.; Altuntaş, O.; Özer, A. Advanced Heat Treatment Strategies for Optimizing Microstructure and Mechanical Integrity of AISI O2 Tool Steel. Ironmak. Steelmak. Process. Prod. Appl. 2025, 52, 1232–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochtar, M.A.; Putra, W.N.; Abram, M. Effect of Tempering Temperature and Subzero Treatment on Microstructures, Retained Austenite, and Hardness of AISI D2 Tool Steel. Mater. Res. Express 2023, 10, 056511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, E.; Kılıçay, K.; Ulutan, M. Microstructure and Tribological Properties of Tool Steel AISI O2 After Thorough Cryogenic Heat Treatment. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 2020, 62, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNI EN ISO 6507-1:2023; Metallic Materials—Vickers Hardness Test—Part 1: Test Method. ISO: Milan, Italy, 2023.

- UNI EN ISO 6508-1:2024; Metallic Materials—Rockwell Hardness Test—Part 1: Test Method. ISO: Milan, Italy, 2024.

- Cerri, E.; Ghio, E.; Bolelli, G. Defect-Correlated Vickers Microhardness of Al-Si-Mg Alloy Manufactured by Laser Powder Bed Fusion with Post-Process Heat Treatments. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2022, 31, 8047–8067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhelaly, M.A.; El-Zomor, M.A.; Attia, M.S.; Youssef, A.O. Characterization and Kinetics of Chromium Carbide Coatings on AISI O2 Tool Steel Performed by Pack Cementation. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2022, 31, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumi, M.; Echeverri, E.A.A.; Tschiptschin, A.P.; Goldenstein, H. Improvement of Wear Resistance in a Pearlitic Rail Steel via Quenching and Partitioning Processing. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günerli, E.; Bayramoğlu, M.; Geren, N. Volume Fraction of Retained Austenite in 1.2842 Tool Steel as a Function of Tempering Temperature. Eur. Mech. Sci. 2022, 6, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, H.; Miyamoto, G.; Hossein Nedjad, S.; Chiba, T.; Nili Ahmadabadi, M.; Furuhara, T. Microstructure Evolution during Austenite Reversion in Fe-Ni Martensitic Alloys. Acta Mater. 2018, 144, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdiere, A.; Castro Cerda, F.; Béjar Llanes, A.; Wu, J.; Crebolder, L.; Petrov, R.H. Effect of the Austenitizing Parameters on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of 75Cr1 Tool Steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 785, 139331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghoubi, M.; Rezaeian, A.; Toroghinejad, M.R.; Mojgani, A.; Gholamalian Dehaghani, H. Effect of Prior Austenite Grain Size on Strength-Ductility Trade-off, Phase Evolution, and Fracture Behavior in a Fully Austenitizated QP Steel: Insights into TRIP Behavior. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 37, 2434–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Hu, X.; Zhu, P.; Xiong, Y.; Zhao, A.; Cao, K. Effects of Y Addition on Carbide Morphology and Impact Properties of D2 Cold Work Die Steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 5040–5051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, T.; Dai, Y.; Yao, J.; Xu, L.; Li, P.; Zhao, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, H. Segregation and Carbide Evolution in AISI D2 Tool Steel Produced by Curved Continuous Casting. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 26, 8254–8262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, I.M.; Moustafa, M.A.; Nofal, A.A. Carbide Formation Mechanism during Solidification and Annealing of 17% Cr-Ferritic Steel. Mater. Lett. 2000, 42, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Maity, S.R.; Patnaik, L. Effect of Surface Modification on the Nanomechanical and Wear Properties of AISI D3 Cold Work Tool Steel. In Recent Advancements in Mechanical Engineering, Select Proceedings of ICRAME 2021, The 2nd International Conference on Recent Advancements of Mechanical Engineering (ICRAME 2021), Silchar, India, 7–9 February 2021; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Navasingh, R.J.H.; Rajendran, T.P.; Nikolova, M.P.; Goldin Priscilla, C.P.; Niesłony, P.; Żak, K. Improved Microstructure Evolution and Corrosion Resistance in Friction-Welded Dissimilar AISI 1010/D3 Steel Joints Through Post-Weld Heat Treatment. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bole, S.; Sarkar, S.B. A Study on the Effect of Prior Hot Forging on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of AISI D2 Steel After Quenching. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 2024, 65, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Khatirkar, R.K.; Sapate, S.G. Microstructure Evolution and Abrasive Wear Behavior of D2 Steel. Wear 2015, 328–329, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlina, E.J.; Van Tyne, C.J. Correlation of Yield Strength and Tensile Strength with Hardness for Steels. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2008, 17, 888–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelleg, J. Testing. In Basic Compounds for Superalloys; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 7–84. [Google Scholar]

- Seok, M.-Y.; Choi, I.-C.; Moon, J.; Kim, S.; Ramamurty, U.; Jang, J. Estimation of the Hall–Petch Strengthening Coefficient of Steels through Nanoindentation. Scr. Mater. 2014, 87, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R. Crystal Engineering for Mechanical Strength at Nano-Scale Dimensions. Crystals 2017, 7, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tao, Q.; Fan, J.; Fu, L.; Shan, A. Enhanced Mechanical Properties of a High-Carbon Martensite Steel Processed by Heavy Warm Rolling and Tempering. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 872, 144958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majerík, J.; Barényi, I.; Kohutiar, M.; Chochlíková, H.; Escherová, J. Experimental Research and Evaluation of Mechanical Properties of Microstructural Components of High Strenght Steels by Quasistatic Nanoindentation. Eng. Rev. 2024, 44, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkamani, H.; Raygan, S.; Rassizadehghani, J. Comparing Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of AISI D2 Steel after Bright Hardening and Oil Quenching. Mater. Des. (1980–2015) 2014, 54, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| AISI | DIN | C | Cr | Mn | Mo | V | Si | P | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O2 | 90MnCrV8 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| D2 | X153CrMoV12 | 1.6 | 12.0 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| D3 | X210Cr13 | 2.2 | 12.5 | 0.7 | - | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| AISI | Carbide Size | AQ-0 | AQ-1 | AQ-2 | AQ-3 | AQ-4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D2 | Large | 3.5 ± 1.3 | 3.4 ± 1.5 | 2.7 ± 1.5 | 2.5 ± 1.1 | 2.6 ± 1.2 |

| Small | 0.89 ± 0.29 | 0.80 ± 0.31 | 0.75 ± 0.39 | 0.79 ± 0.32 | 0.81 ± 0.49 | |

| D3 | Large | 3.9 ± 1.4 | 3.7 ± 1.5 | 3.5 ± 1.2 | 3.0 ± 1.1 | 2.9 ± 0.8 |

| Small | 1.04 ± 0.70 | 1.05 ± 0.65 | 0.95 ± 0.33 | 0.85 ± 0.27 | 0.78 ± 0.25 |

| Property | AISI D2 | AISI D3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQ-0 | AQ-2 | AQ-4 | AQ-0 | AQ-2 | AQ-4 | |

| Vickers hardness [HV1] | 236 ± 4 | 660 ± 25 | 697 ± 15 | 229 ± 10 | 652 ± 9 | 675 ± 16 |

| Estimated yield strength [MPa] 1 | 661 | 1848 | 1952 | 641 | 1826 | 1890 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghio, E.; Felci, M.; Garziera, R. Effects of Multiple Quenching Treatments on Microstructure and Hardness of O2, D2, and D3 Tool Steels. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 395. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120395

Ghio E, Felci M, Garziera R. Effects of Multiple Quenching Treatments on Microstructure and Hardness of O2, D2, and D3 Tool Steels. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2025; 9(12):395. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120395

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhio, Emanuele, Matteo Felci, and Rinaldo Garziera. 2025. "Effects of Multiple Quenching Treatments on Microstructure and Hardness of O2, D2, and D3 Tool Steels" Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 9, no. 12: 395. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120395

APA StyleGhio, E., Felci, M., & Garziera, R. (2025). Effects of Multiple Quenching Treatments on Microstructure and Hardness of O2, D2, and D3 Tool Steels. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 9(12), 395. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120395