Highlights

- The proposed -NFTSTC exhibits high robustness and fast finite-time convergence under unknown disturbances.

- The results show that it outperforms conventional methods in scenarios involving wind disturbances, collision avoidance under periodic disturbances, and sudden partial propeller damage.

- The proposed -NFTSTC mitigates the trade-off issues inherent in the respective designs of the low-pass filter for adaptive control and the switching gain for nonsingular fast terminal super-twisting sliding mode control.

- The proposed -NFTSTC is a promising technique that enhances the robustness of the quadrotor against disturbances while leveraging its high maneuverability.

Abstract

1. Introduction

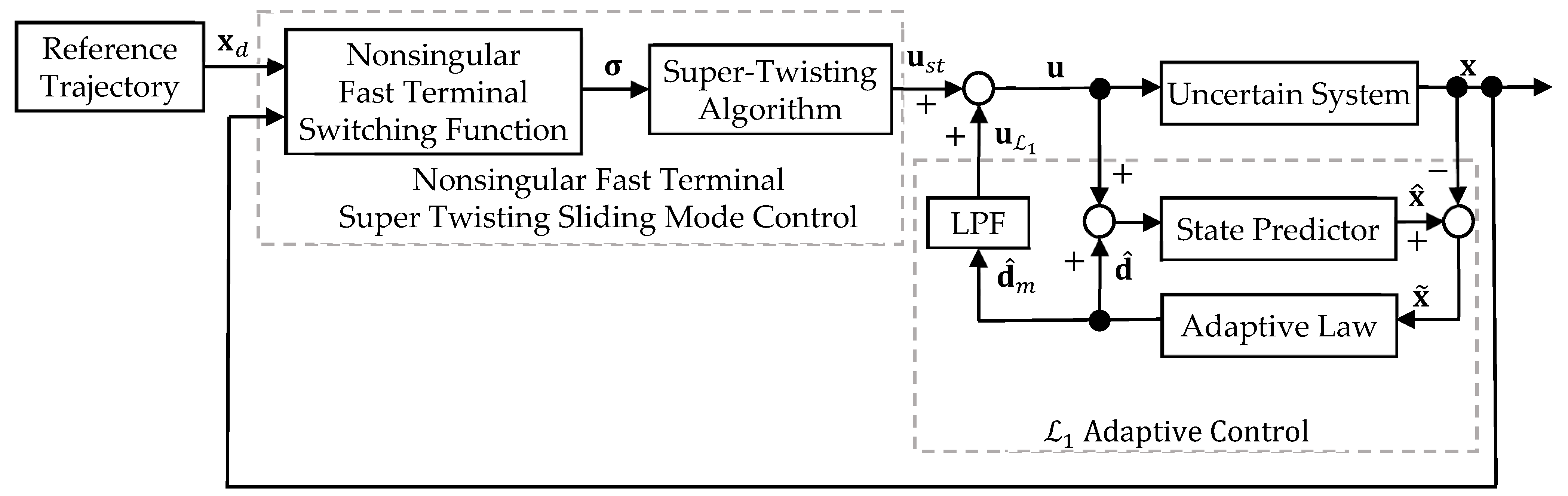

- Complementary effects of adaptive control and NFTSTC in disturbance suppression: adaptive control possesses a structure that compensates for disturbances using a low-pass filter following disturbance estimation. Consequently, while it can suppress low-frequency and high-amplitude disturbances, the issue remains that high-frequency disturbances persist to a certain extent. Conversely, the NFTSTC demonstrates suppression performance based on the super-twisting algorithm against residual disturbances that could not be fully eliminated by adaptive control. As a result, the proposed -NFTSTC achieves complementary disturbance suppression that leverages the characteristics of both methods.

- Mitigation of trade-offs in controller design parameters: The proposed -NFTSTC mitigates the issue of trade-offs in design parameters through the complementary effects in disturbance suppression. First, in the design of the low-pass filter for adaptive control, since the NFTSTC suppresses high-frequency disturbances, it becomes possible to set a conservative bandwidth that prioritizes noise rejection. Furthermore, since most of the disturbances are cancelled by adaptive control, the upper bound of the disturbance that the NFTSTC must handle is reduced, allowing the switching gain to be set to a minimal value. Such measures avoid excessive switching gains in the NFTSTC even in environments where the upper bound of the disturbance is unknown, thereby preventing chattering caused by the high switching gain.

- Improvement of robustness in the reaching mode: Although the NFTSTC possesses robustness during the sliding mode, it lacks robustness against disturbances during the reaching mode. Conversely, since adaptive control performs disturbance suppression across the entire time domain, it can compensate for the vulnerability of the NFTSTC during the reaching mode. Consequently, the proposed -NFTSTC maintains robustness throughout the entire time domain, and since the baseline NFTSTC can focus on tracking control, its fast finite-time convergence performance is fully maximized.

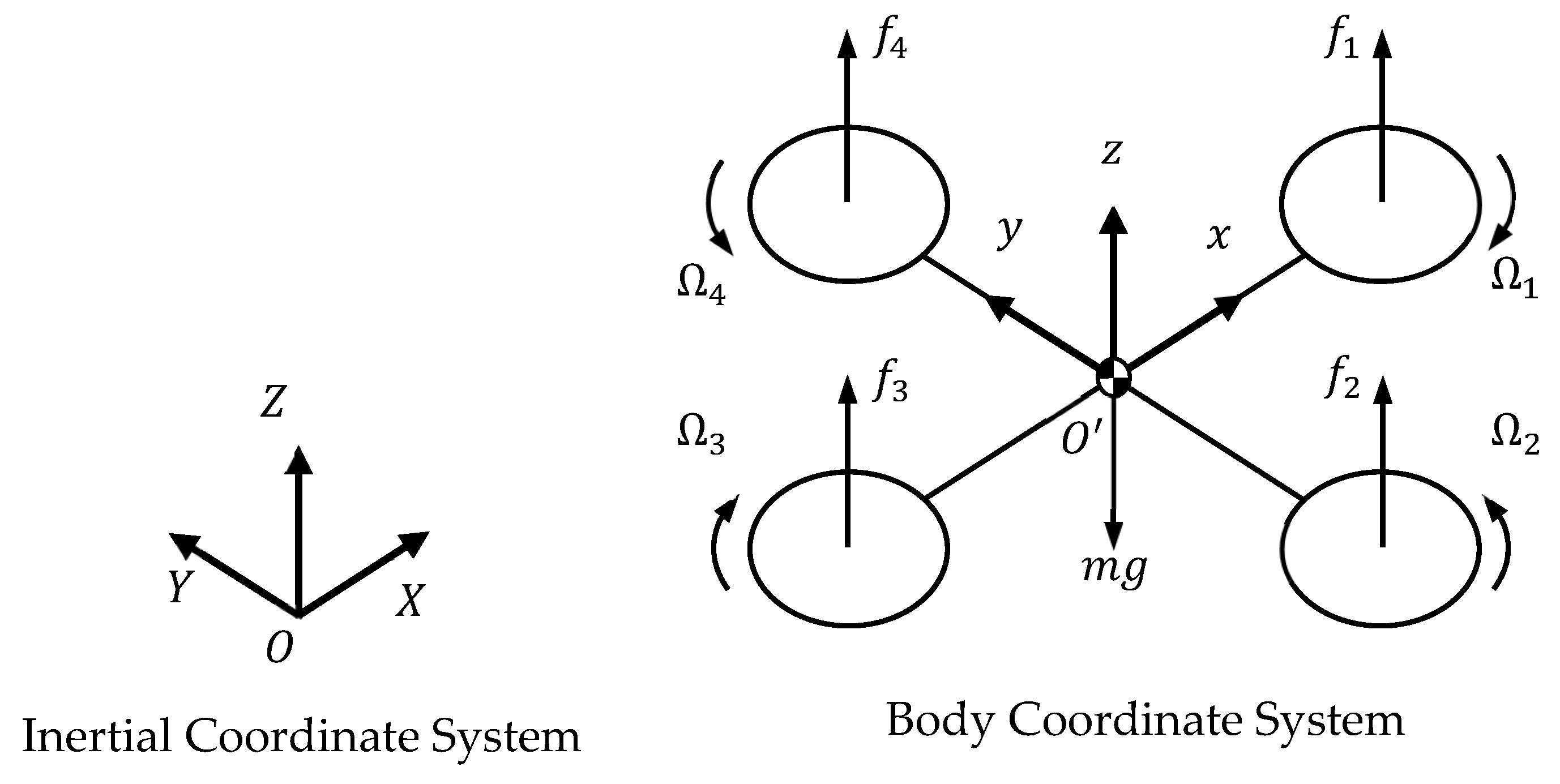

2. Dynamics of the Quadrotor UAV and Feedback Linearization

2.1. Nonlinear Equations of Motion for the Quadrotor UAV

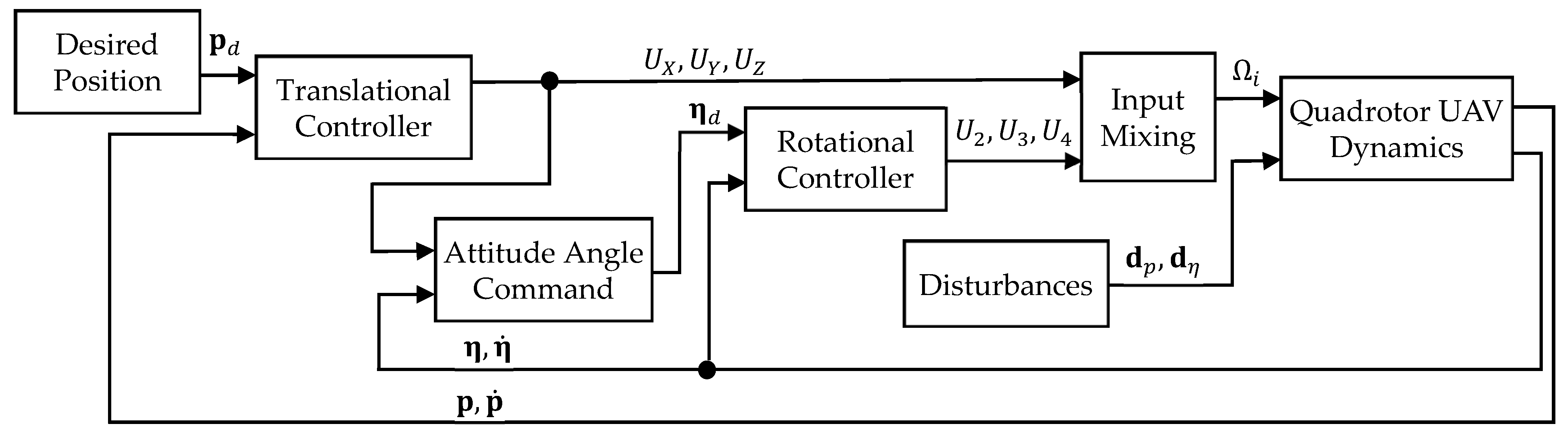

2.2. Feedback Linearization and Control Commands

3. Controller Design

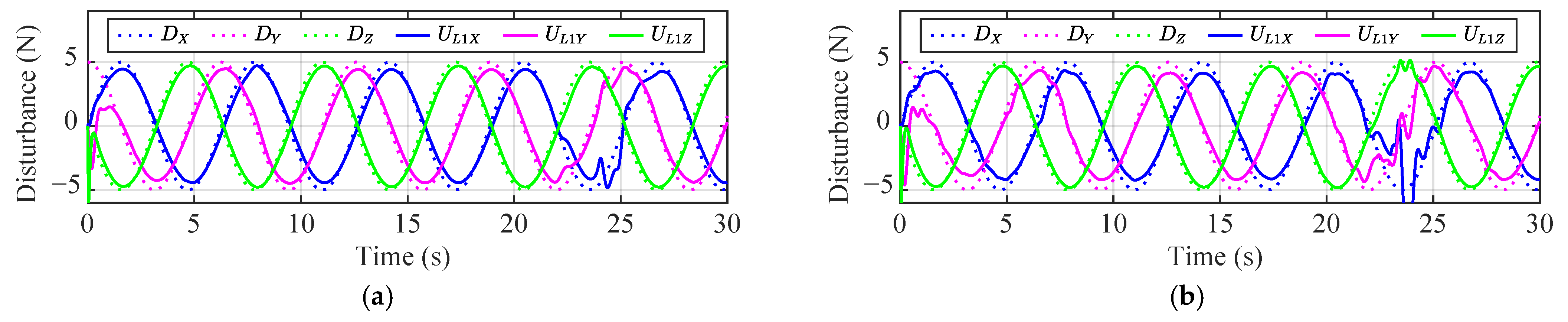

3.1. Adaptive Control

3.2. Nonsingular Fast Terminal Super Twisting Sliding Mode Control

3.3. Stability Analysis

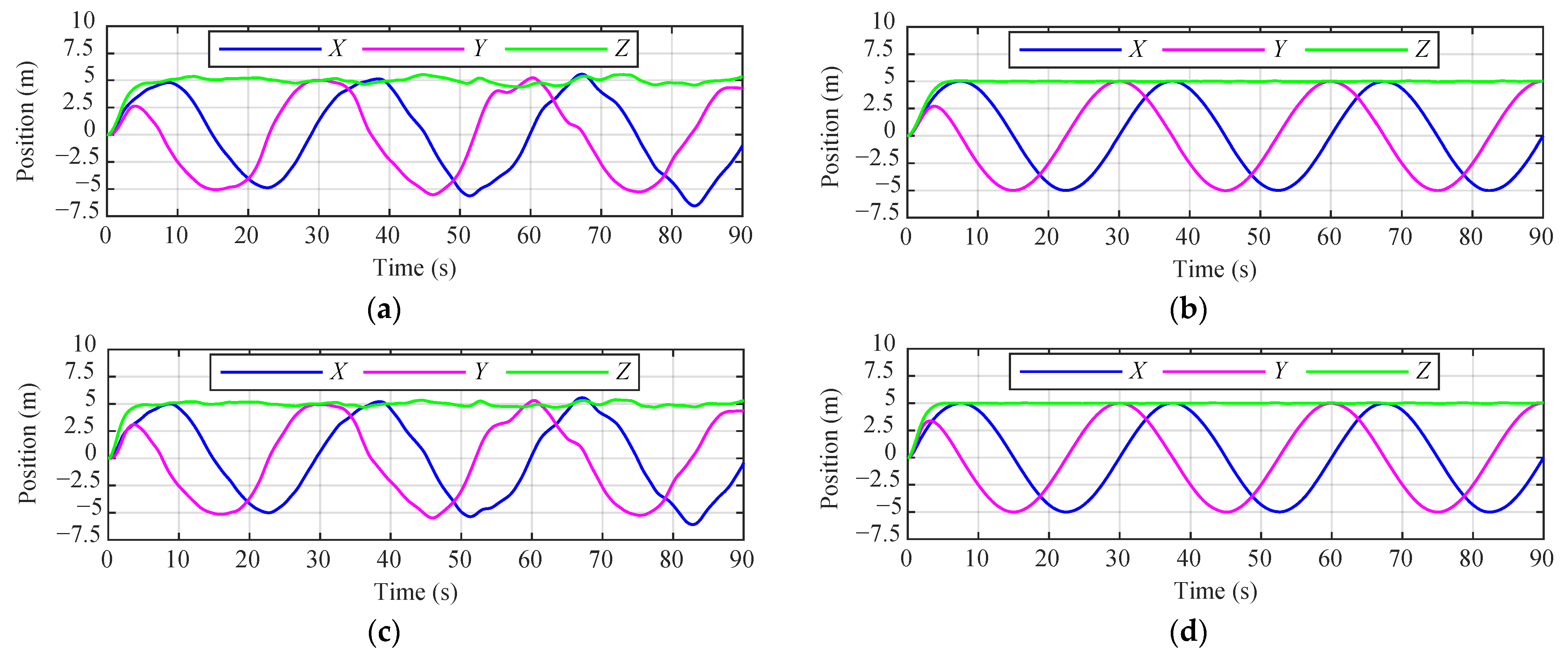

4. Numerical Simulation

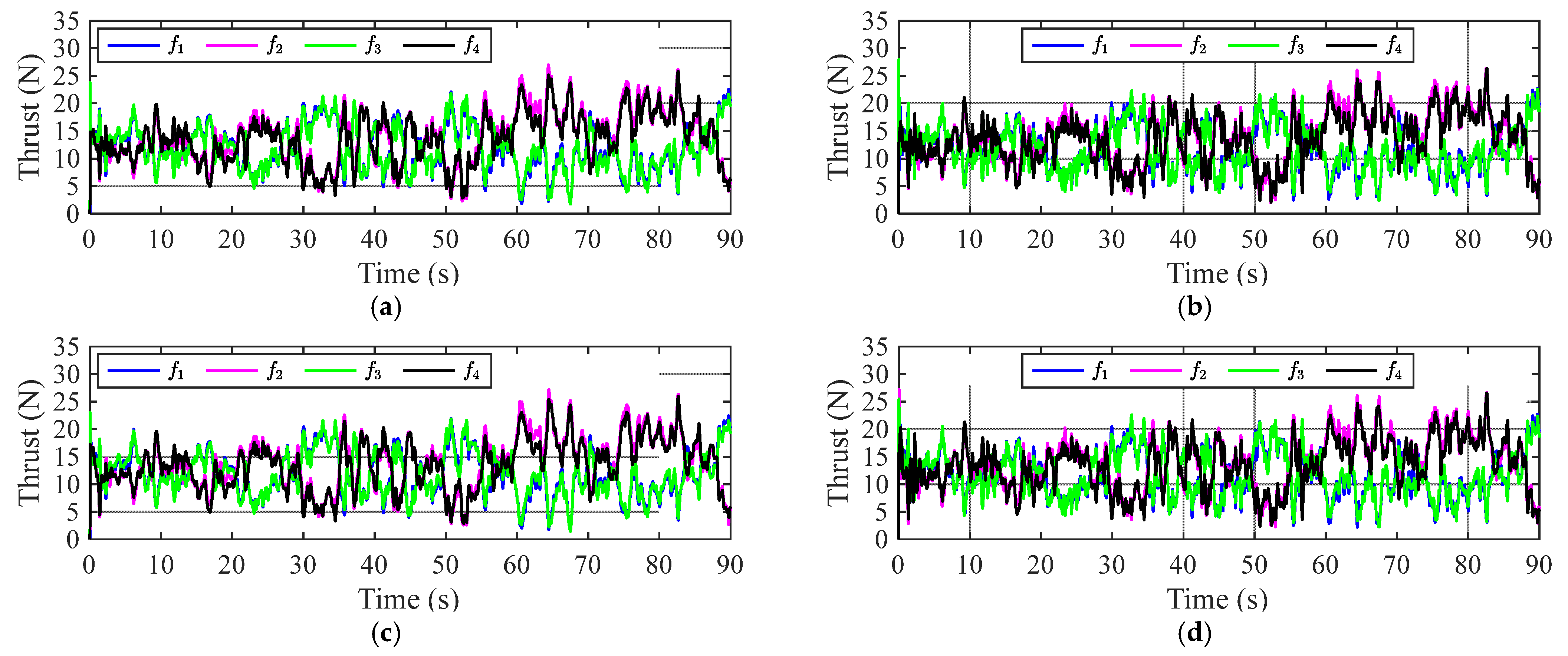

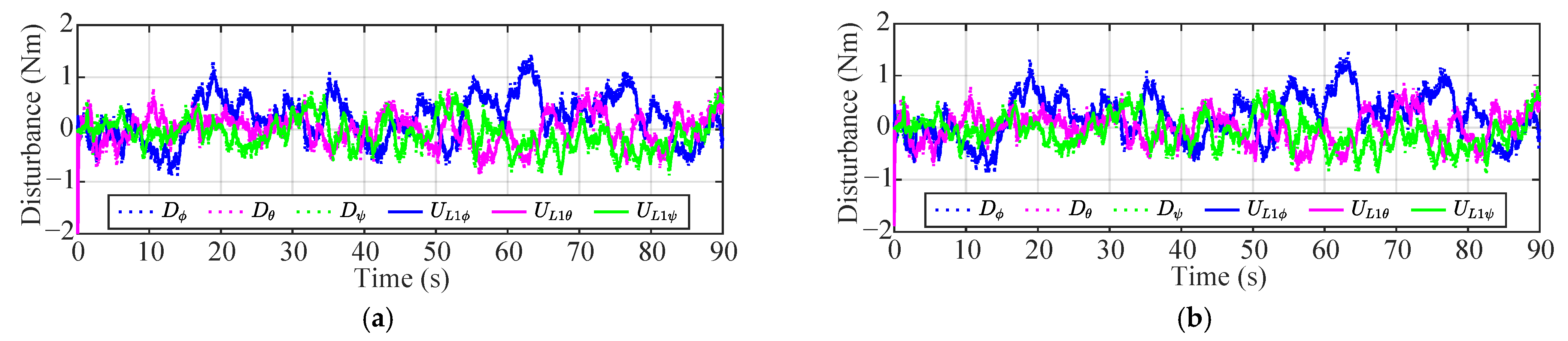

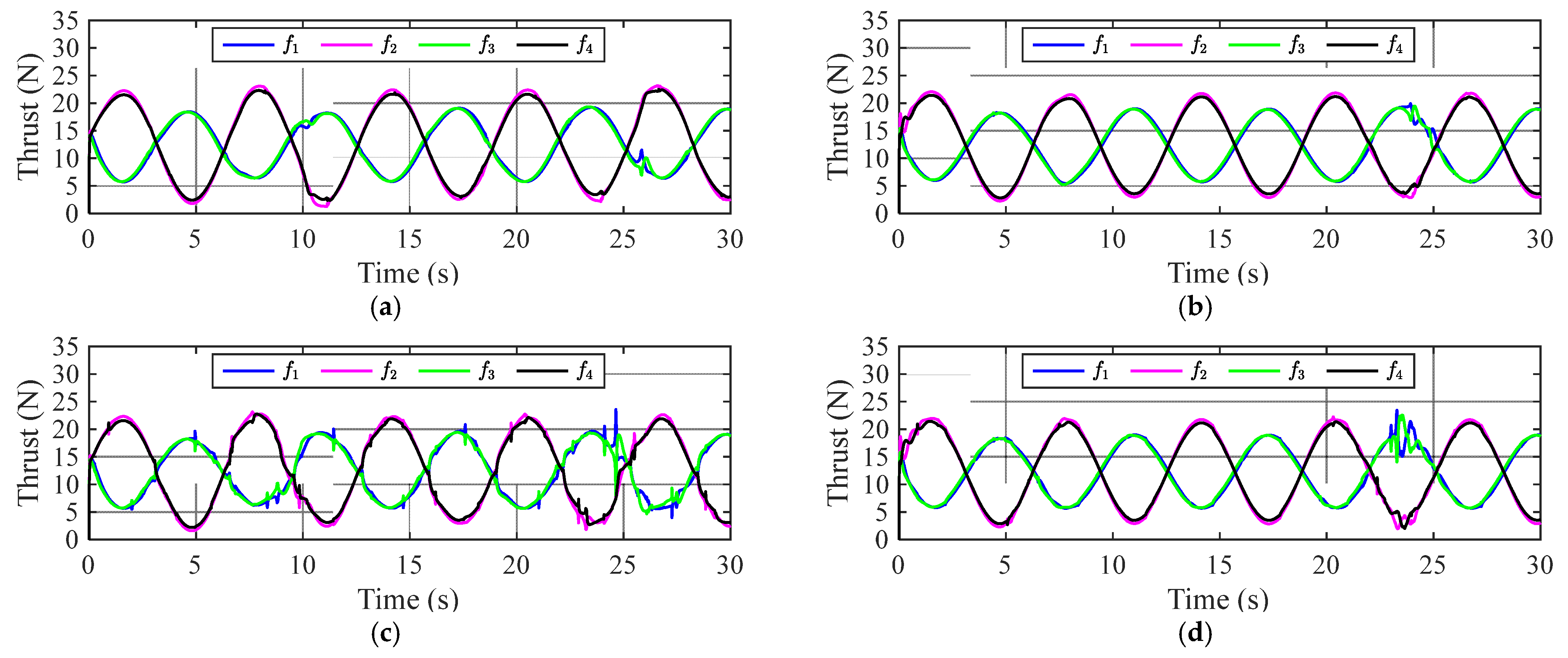

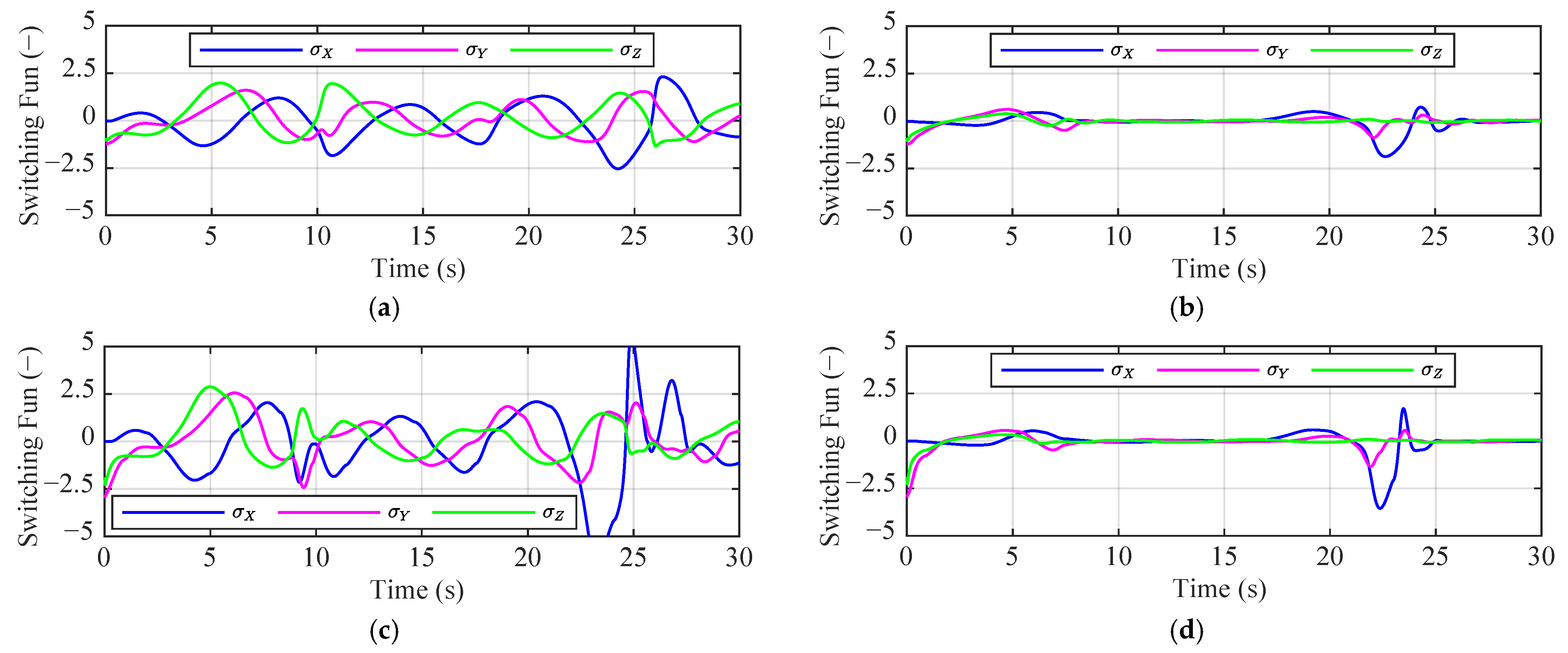

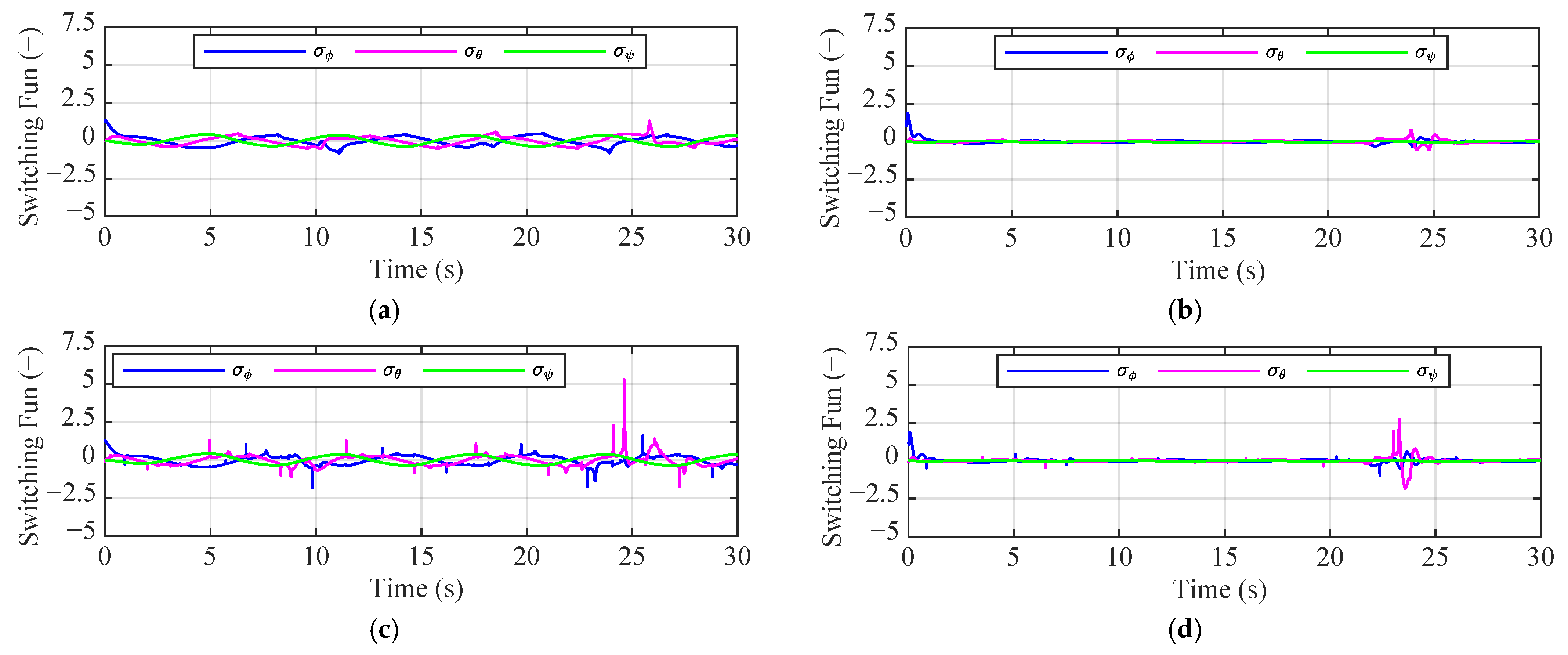

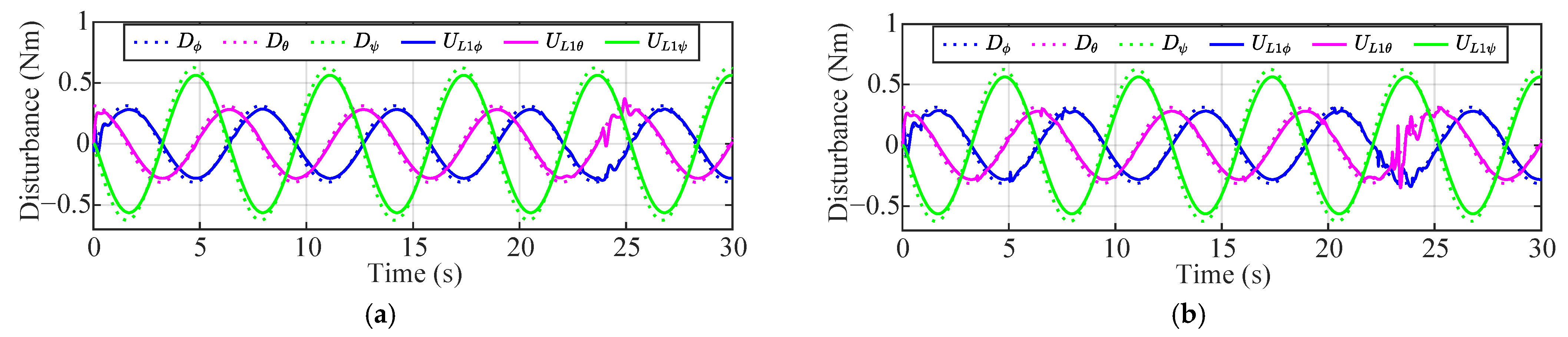

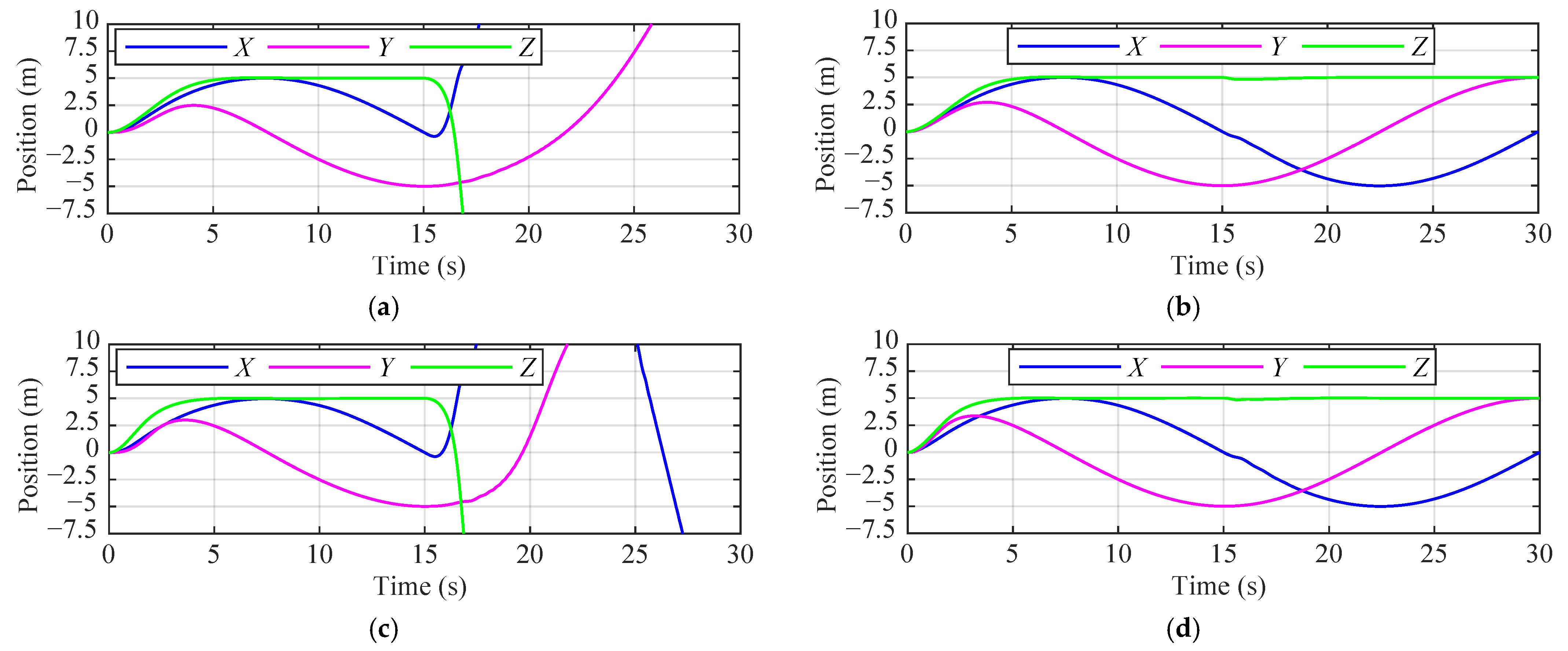

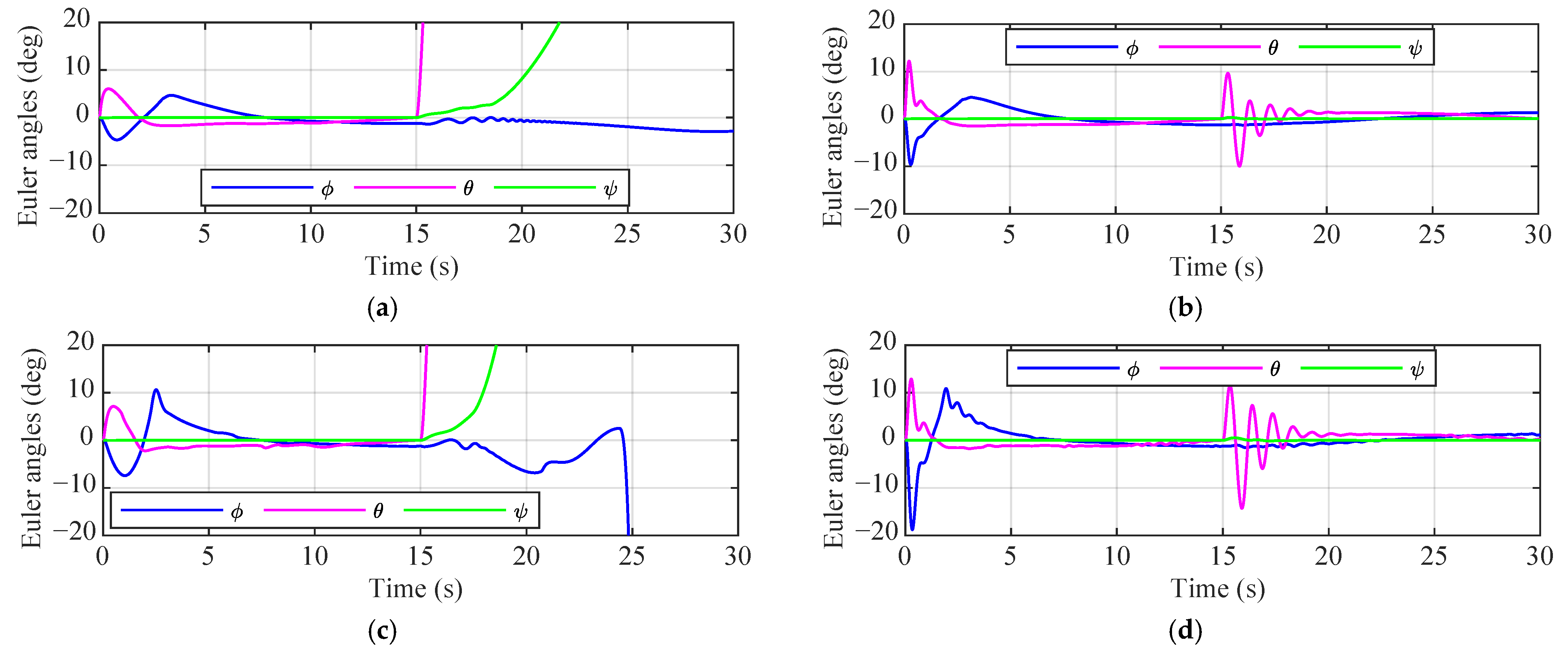

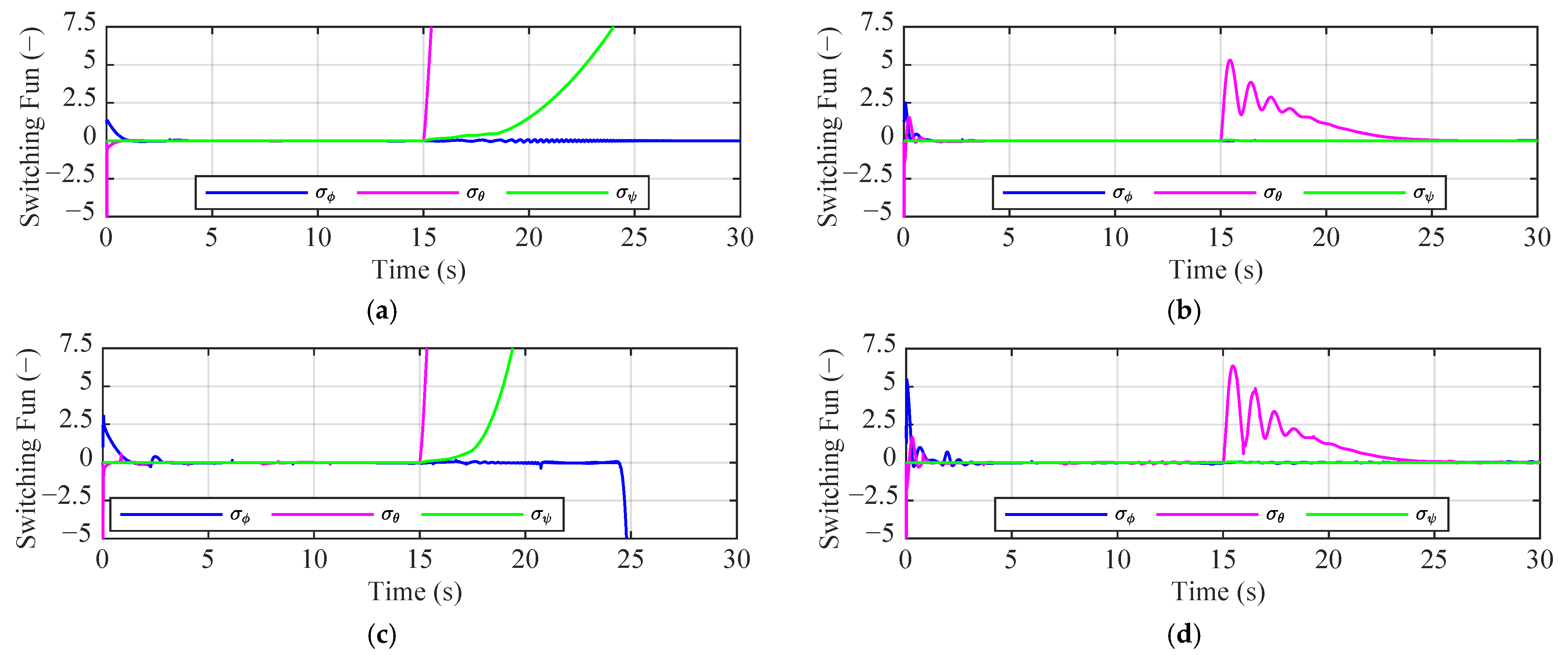

4.1. Scenario 1: External Disturbance

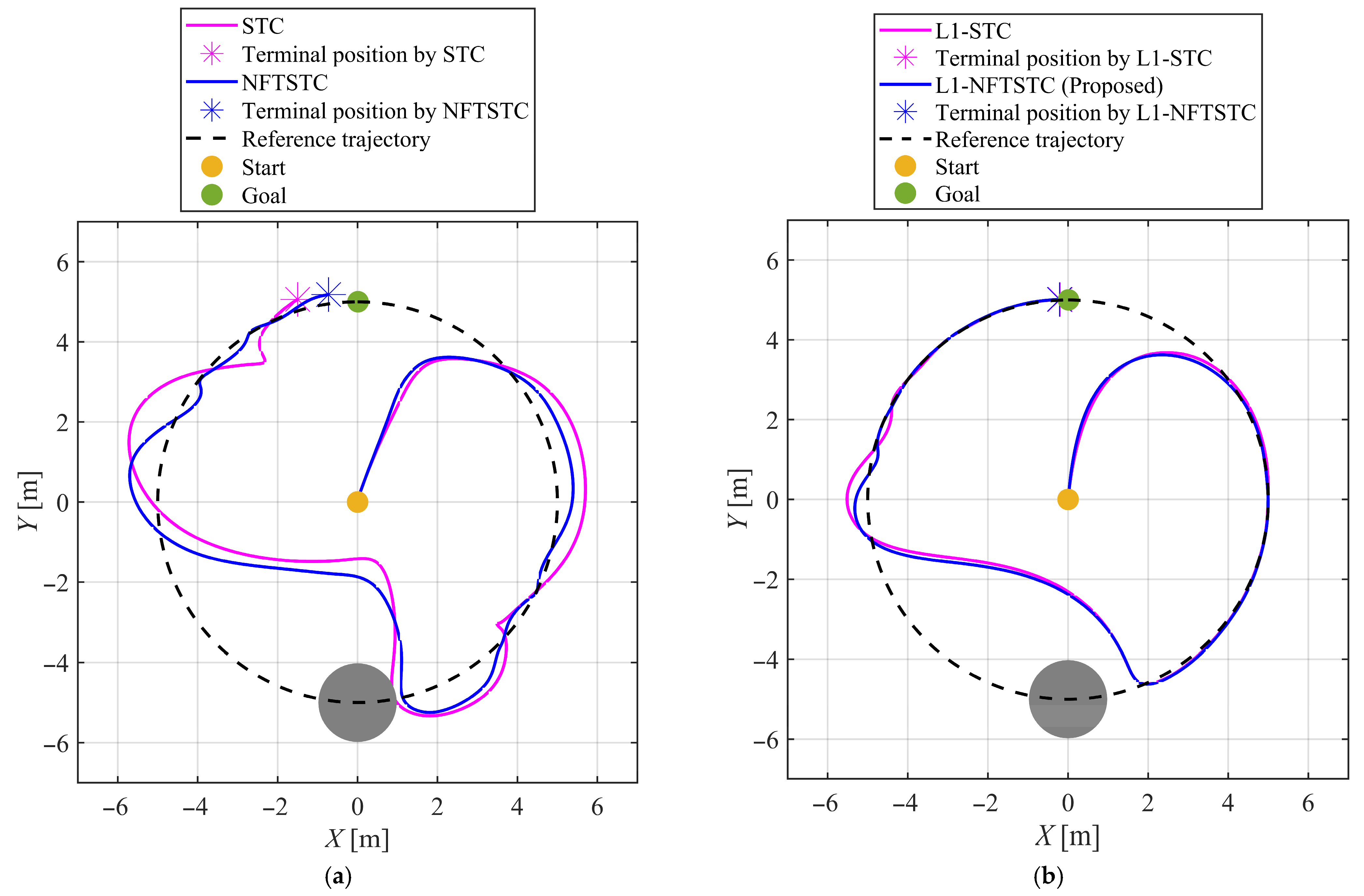

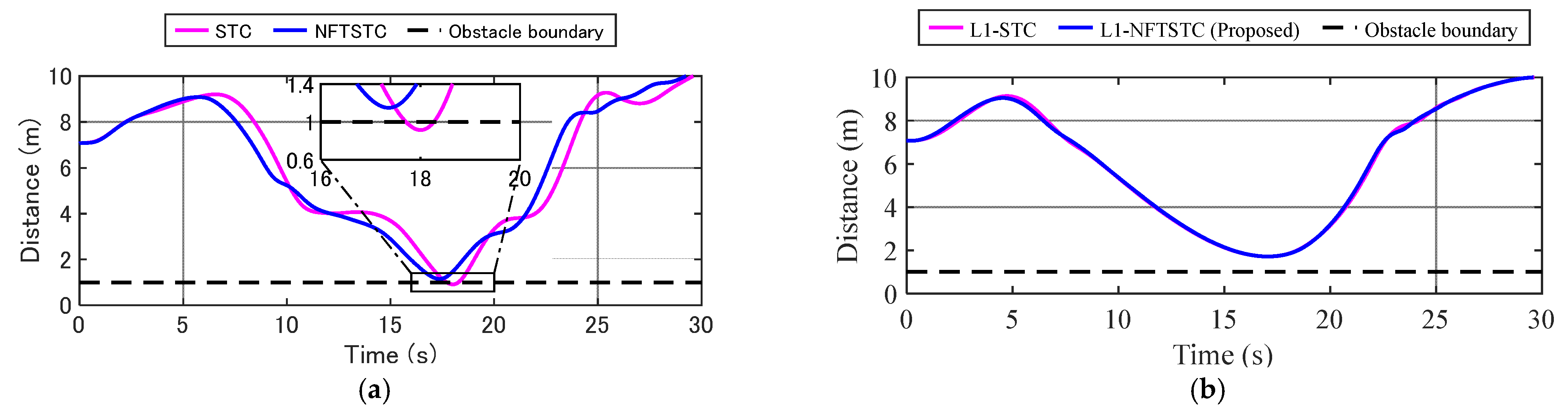

4.2. Scenario 2: Collision Avoidance

4.3. Scenario 3: Propeller Damage

4.4. Discussion on Real-Time Implementation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| PID | Proportional–Integral–Derivative Control |

| LQR | Linear Quadratic Regulator |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| FTC | Finite-Time Control |

| SMC | Sliding Mode Control |

| STC | Super-Twisting (Sliding Mode) Control |

| STA | Super-Twisting Algorithm |

| TSMC | Terminal Sliding Mode Control |

| NFTSMC | Nonsingular Fast Terminal Sliding Mode Control |

| NFTSTC | Nonsingular Fast Terminal Super-Twisting (Sliding Mode) Control |

| MRAC | Model Reference Adaptive Control |

| AC | Adaptive Control |

| -STC | (Adaptive) Super-Twisting (Sliding Mode) Control |

| -NFTSTC | (Adaptive) Nonsingular Fast Terminal Super-Twisting (Sliding Mode) Control |

| ISE | Integral of Squared Error |

| IAE | Integral of Absolute Error |

References

- Gupte, S.; Mohandas, P.I.T.; Conrad, J.M. A survey of quadrotor Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Southeastcon, Orlando, FL, USA, 15–18 March 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenard, N.; Hamel, T.; Eck, L. Control Laws for the Tele Operation of an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Known as an X4-flyer. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Beijing, China, 9–15 October 2006; pp. 3249–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, N.; Bieniawski, S.; Kroo, I.; Vian, J. Control of Multiple UAVs for Persistent Surveillance: Algorithm and Flight Test Results. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2012, 20, 1236–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Liu, P.X.; El Saddik, A. Robust Control of Four-Rotor Unmanned Aerial Vehicle with Disturbance Uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 1563–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmaksoud, S.I.; Mailah, M.; Abdallah, A.M. Control Strategies and Novel Techniques for Autonomous Rotorcraft Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: A Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 195142–195169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Gadsden, S.A.; Wilkerson, S.A. A Comprehensive Survey of Control Strategies for Autonomous Quadrotors. Can. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2020, 43, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, N.; Lynch, A.F. Inner–Outer Loop Control for Quadrotor UAVs with Input and State Constraints. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2016, 24, 1797–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faessler, M.; Falanga, D.; Scaramuzza, D. Thrust Mixing, Saturation, and Body-Rate Control for Accurate Aggressive Quadrotor Flight. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2017, 2, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Kamel, M.; Alexis, K.; Siegwart, R. Model Predictive Control for Micro Aerial Vehicles: A Survey. In Proceedings of the 2021 European Control Conference (ECC), Delft, The Netherlands, 29 June–2 July 2021; pp. 1556–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, T.; Benallegue, A. Backstepping Control for a Quadrotor Helicopter. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Beijing, China, 9–15 October 2006; pp. 3255–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utkin, V.I. Variable structure systems with sliding modes. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1977, 22, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utkin, V.I. Sliding mode control design principles and applications to electric drives. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 1993, 40, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, J.Y.; Gao, W.; Hung, J.C. Variable structure control: A survey. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 1993, 40, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Ozguner, U. Sliding Mode Control of a Quadrotor Helicopter. In Proceedings of the 45th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, San Diego, CA, USA, 13–15 December 2006; pp. 4957–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.; Yang, Y.; Chai, L. Extended State Observer based MPC for a Quadrotor Helicopter Subject to Wind Disturbances. In Proceedings of the 2019 Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Guangzhou, China, 27–30 July 2019; pp. 8206–8211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komiyama, S.; Uchiyama, K.; Masuda, K. Combined Robust Control for Quadrotor UAV Using Model Predictive Control and Super-Twisting Algorithm. Drones 2025, 9, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubagotti, M.; Raimondo, D.M.; Ferrara, A.; Magni, L. Robust Model Predictive Control with Integral Sliding Mode in Continuous-Time Sampled-Data Nonlinear Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2011, 56, 556–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incremona, G.P.; Ferrara, A.; Magni, L. MPC for Robot Manipulators with Integral Sliding Modes Generation. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2017, 22, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, M.; Liang, T. H-Infinity Model Predictive Control of Discrete-Time Constrained Singular Piecewise-Affine Systems with Time Delay. In Proceedings of the 2014 Fourth International Conference on Instrumentation and Measurement, Computer, Communication and Control, Harbin, China, 18–20 September 2014; pp. 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Lu, R.; Zuo, Z.; Li, X. An Overview of Finite/Fixed-Time Control and Its Application in Engineering Systems. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sinica 2022, 9, 2106–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiari, M.; Panahyazdan, A.; Abbasali, E. Finite-Time Control for Satellite Formation Reconfiguration and Maintenance in LEO: A Nonlinear Lyapunov-Based SDDRE Approach. Aerospace 2025, 12, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Han, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, X. Distributed Robust Fast Finite-Time Formation Control of Underactuated ASVs in Presence of Information Interruption. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Feng, Y.; Man, Z. Terminal Sliding Mode Control—An Overview. IEEE Open J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2021, 2, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, Z.; Paplinski, A.P.; Wu, H.R. A robust MIMO terminal sliding mode control scheme for rigid robotic manipulators. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1994, 39, 2464–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, Z.; Yu, X.H. Terminal sliding mode control of MIMO linear systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Fundam. Theory Appl. 1997, 44, 1065–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Man, Z. Fast terminal sliding-mode control design for nonlinear dynamical systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Fundam. Theory Appl. 2002, 49, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jin, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y. RBFNN-based nonsingular fast terminal sliding mode control for piezoelectric stack actuator. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advanced Mechatronic Systems (ICAMechS), Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan, 26–30 November 2024; pp. 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.; Gao, H.; Nasir, A.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C. Adaptive-Neural Finite-Time Sliding Mode Control for Quadrotor Helicopter Attitude Stabilization in Complex Environments. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 61, 1175–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Kim, B.W. A Novel Adaptive Non-Singular Fast Terminal Sliding Mode Control for Direct Yaw Moment Control in 4WID Electric Vehicles. Sensors 2025, 25, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.; Bernstein, D. Finite-time stability of continuous autonomous systems. SIAM J. Control Optim. 2000, 38, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, A.K.; Zheng, Z.; Feroskhan, M. Depth-Independent Augmented Dynamics Visual Servoing of Multirotor. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 61, 5444–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yang, J. Nonsingular fast terminal sliding-mode control for nonlinear dynamical systems. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2011, 21, 1865–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Yang, Y. Adaptive Neural-Network-Based Nonsingular Fast Terminal Sliding Mode Control for a Quadrotor with Dynamic Uncertainty. Drones 2022, 6, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Han, Z.; Wang, J. Super-Twisting Algorithm Backstepping Adaptive Terminal Sliding-Mode Tracking Control of Quadrotor Drones Subjected to Faults and Disturbances. Drones 2025, 9, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Cao, L.; Peng, B.; Wang, L.; Gen, C.; Liu, Y. Adaptive Nonsingular Fast Terminal Sliding Mode Control of Aerial Manipulation Based on Nonlinear Disturbance Observer. Drones 2023, 7, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Liu, W.; Li, L.; Xu, J.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y. Fast Finite-Time Super-Twisting Sliding Mode Control with an Extended State Higher-Order Sliding Mode Observer for UUV Trajectory Tracking. Drones 2024, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levant, A. Sliding order and sliding accuracy in sliding mode control. Int. J. Control 1993, 58, 1247–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiko, I.; Fridman, L. Analysis of chattering in continuous sliding-mode controllers. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2005, 50, 1442–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.A.; Osorio, M. Strict Lyapunov Functions for the Super-Twisting Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2012, 57, 1035–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, T.; Moreno, J.A.; Fridman, L. Variable Gain Super-Twisting Sliding Mode Control. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2012, 57, 2100–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.; Hu, M.; Chung, Y.; You, K. Sliding-Mode Control for Flight Stability of Quadrotor Drone Using Adaptive Super-Twisting Reaching Law. Drones 2023, 7, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ye, H.; Yang, X. Super-Twisting Sliding Mode Control for the Trajectory Tracking of Underactuated USVs with Disturbances. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wu, H.; Cheng, L. Design of terminal sliding mode controller for a quadrotor UAV with disturbance observer. In Proceedings of the 2020 39th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Shenyang, China, 27–29 July 2020; pp. 2072–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Q. Second-order Terminal Sliding Mode Control for Near-space Vehicles Based on Disturbance Observer. In Proceedings of the 2018 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC), Xi’an, China, 30 November–2 December 2018; pp. 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ren, H.; Wang, S.; Fang, Y. Integral Sliding Mode Control for PMSM with Uncertainties and Disturbances via Nonlinear Disturbance Observer. In Proceedings of the 2020 39th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Shenyang, China, 27–29 July 2020; pp. 2055–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Hovakimyan, N. Design and Analysis of a Novel L1 Adaptive Controller, Part I: Control Signal and Asymptotic Stability. In Proceedings of the 2006 American Control Conference, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 14–16 June 2006; pp. 3397–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Hovakimyan, N. Stability Margins of L1 Adaptive Controller: Part II. In Proceedings of the 2007 American Control Conference, New York, NY, USA, 11–13 July 2007; pp. 3931–3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Hovakimyan, N. Design and Analysis of a Novel L1 Adaptive Control Architecture with Guaranteed Transient Performance. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2008, 53, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Hovakimyan, N. L1 Adaptive Output Feedback Controller for Systems of Unknown Dimension. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2008, 53, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Huang, S.; Xiang, C.; Teo, R.; Srigrarom, S.; Leong, W.W.L. AI-based Adaptive Nonlinear MPC for Quadrotors. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Chania, Crete, Greece, 4–7 June 2024; pp. 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, B.; Cheng, X.; Hovakimyan, N.; Cao, C. L1Quad:L1 Adaptive Augmentation of Geometric Control for Agile Quadrotors with Performance Guarantees. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2025, 33, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Miao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; Wang, X.; He, W. L1 Adaptive Control-Based Formation Tracking of Multiple Quadrotors Without Linear Velocity Feedback Under Unknown Disturbances. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 5804–5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz, J.J.; Becerra, V.; Revestido Herrero, E.; Llata, J.R.; Velasco, F.J. L1 Adaptive Control for Marine Structures. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; She, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Wan, L. Research on L1 Adaptive Control of Autonomous Underwater Vehicles with X-Rudder. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, H.; Guo, H. L1 Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Control for Nonlinear Systems Subject to Input Constraint and Multiple Faults. Actuators 2024, 13, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Li, Y.; Yuan, J.; Ai, J.; Dong, Y. Adaptive Control Based on Dynamic Inversion for Morphing Aircraft. Aerospace 2023, 10, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouabdallah, S.; Murrieri, P.; Siegwart, R. Design and control of an indoor micro quadrotor. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA ‘04), New Orleans, LA, USA, 26 April–1 May 2004; pp. 4393–4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Ahn, H.; Chung, Y.; You, K. Quadrotor Position and Attitude Tracking Using Advanced Second-Order Sliding Mode Control for Disturbance. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, M.; Hayat, R.; Zeb, K.; Al-Durra, A.; Ullah, Z. Robust Feedback Linearization Based Disturbance Observer Control of Quadrotor UAV. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 17966–17981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowitz, M.; Stegun, I.A. Handbook of Mathematical Functions: With Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables; Dover: New York, NY, USA, 1972; pp. 556–562. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Defense. Flying Qualities of Piloted Airplanes; U.S. Military Specification MIL-F-8785C; U.S. Department of Defense: Washington, DC, USA, 1980.

- Chiba, S.; Uchiyama, K.; Masuda, K. Guidance Method without Terrain Information for an Exploration Rover. In Proceedings of the 2019 Australian & New Zealand Control Conference (ANZCC), Auckland, New Zealand, 27–29 November 2019; pp. 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Mass of quadrotor | ||

| Rotor and axis distance | ||

| Inertia tensor of quadrotor | ||

| Inertia tensor of rotor | ||

| Lift coefficient of rotor | ||

| Drag coefficient of rotor | ||

| Time constant of rotor | ||

| Sampling time |

| Translation | Rotation | |

|---|---|---|

| ISE | IAE | ISE | IAE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STC | 149.2 | 79.21 | 86.01 | 19.01 |

| NFTSTC | 101.6 | 59.41 | 61.48 | 14.58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Komiyama, S.; Uchiyama, K.; Masuda, K.

Komiyama S, Uchiyama K, Masuda K.

Komiyama, Shunsuke, Kenji Uchiyama, and Kai Masuda.

2025. "

Komiyama, S., Uchiyama, K., & Masuda, K.

(2025).