The following Subsections present the experimental results of multimodal reasoning capabilities of LLMs, compare its performance against some baselines, and investigate how the model scale, the level of sensory abstraction, prompt engineering strategies, the inclusion of different sensing modalities, and the effect of memory influence the overall system performance.

4.1. Multimodal Reasoning Capabilities of LLMs for UGV Planning

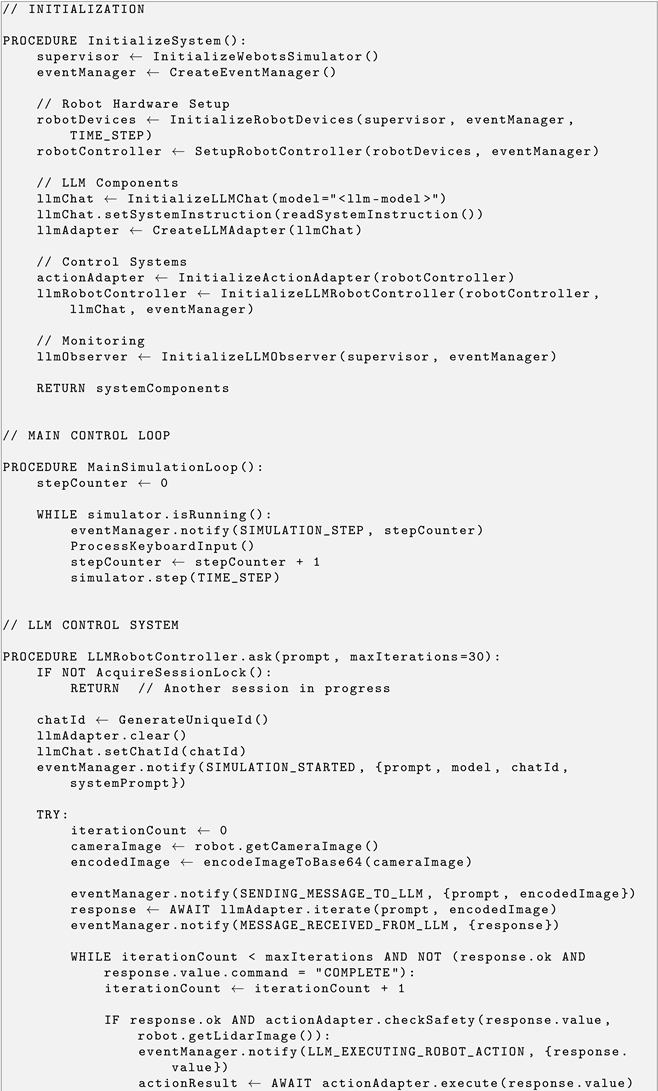

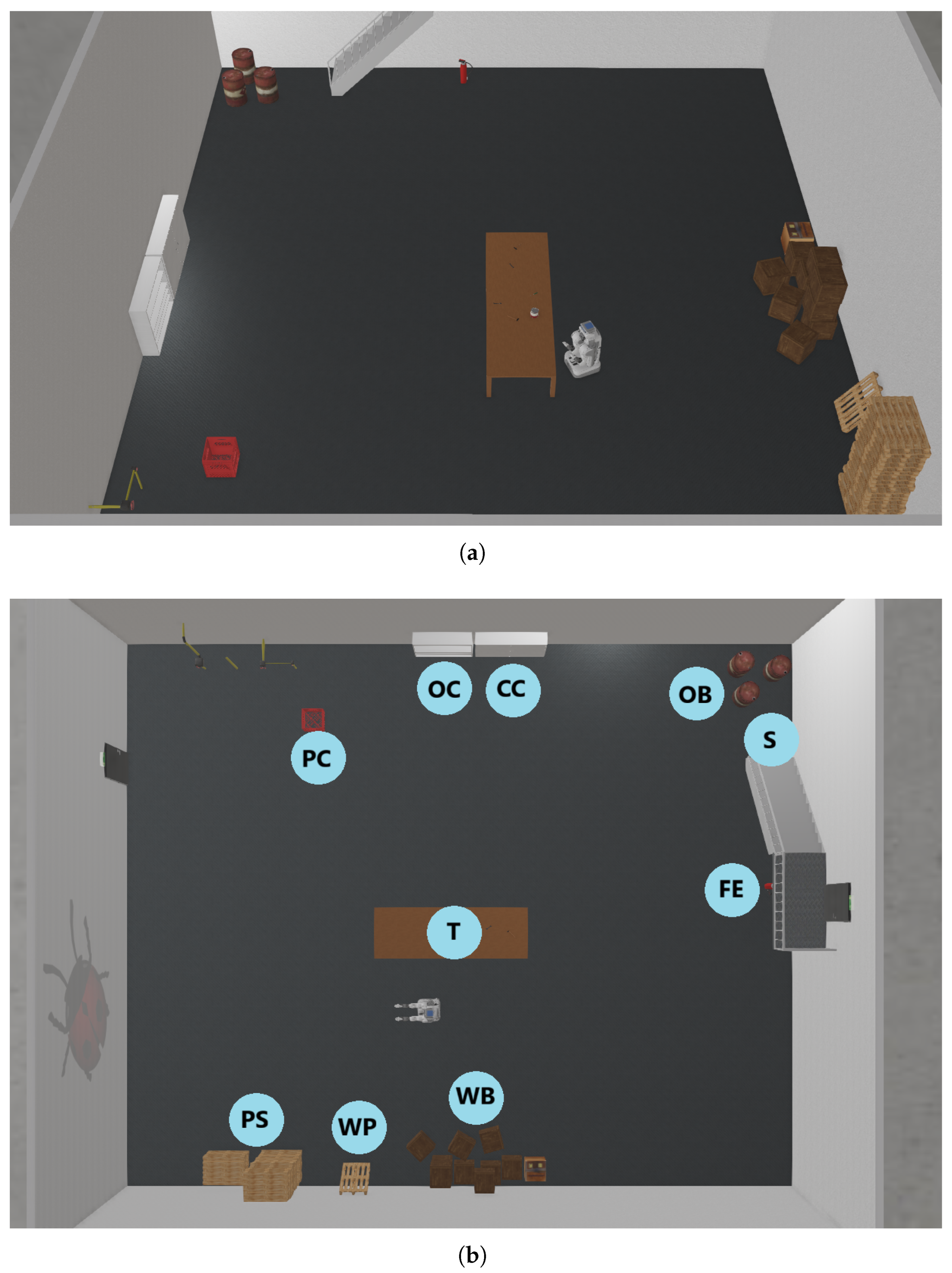

To assess the impact of multimodal inputs on the reasoning and planning abilities of LLMs in UGV contexts, we benchmarked Gemini 2.0 Flash (Google DeepMind) on ten semantically and spatially diverse navigation tasks within the simulated factory environment. As anticipated, each task was executed twenty times, using five different starting positions, in a closed-loop control framework, where the LLM received visual and LiDAR context at each step to iteratively refine its plan.

Performance was quantified using the metrics introduced in

Section 3.6 and

Section 3.7.

Table 1 summarizes the zero-shot performance across ten navigation and exploration tasks.

Across all tasks, the model exhibited robust multimodal grounding, reflected in the absence of JSON-formatting errors and its ability to consistently translate visual and LiDAR cues into structured action commands. Safety interventions were generally moderate, increasing only in the most challenging scenarios (e.g., Tasks 7 and 9), where environmental clutter or long-range occlusions complicated the spatial reasoning process. Latency varied widely across tasks, highlighting the delay introduced by the interaction with LLM, especially in scenes requiring deeper reasoning.

Task 6 demonstrates the model’s strongest capabilities, achieving a perfect success rate and score. This task requires only a 360° situational scan, and the model consistently selects the correct action sequence with minimal iterations, low latency, and no safety interventions. The result confirms that when the navigation problem reduces to straightforward perception alignment—without multi-step reasoning—the model can reliably ground the instruction in sensor data. Task 7 was also completed successfully across all episodes. However, because it involves generic free exploration without a specific target, the scoring metric does not apply (Score = N.A.). The model nevertheless maintained stable behavior, indicating that low-constraint exploratory tasks can be handled without significant drift or safety issues.

Good performance was additionally observed in Tasks 2, 3, and 8, which involve moderately structured spatial reasoning. These tasks yielded consistent successes (10–15) and the highest nontrivial scores in the dataset (0.34–0.47). Here, the model showed an ability to relate visual and LiDAR cues to goal descriptions even when the layout required limited inference about occluded regions or indirect object localization.

Tasks 5, 9, and 10 produced partial successes, with moderate task completions and low but non-zero scores. These scenarios included: (i) cluttered but structured environments, (ii) indirect or partially occluded goal positions, and (iii) mild spatial ambiguities requiring short multi-step reasoning. In these tasks, the model often generated plausible short-term motion suggestions but struggled to maintain consistency across multiple decision cycles, leading to increased safety interventions and failure to converge reliably on a correct long-horizon strategy.

Tasks 1 and 4 represent clear failure cases, despite their superficial simplicity in terms of layout. Task 1, which should have been trivial, resulted in very low scores due to inconsistent grounding of the goal location and unstable plan execution. Task 4 performed even worse, with near-zero scores and minimal successful episodes. Even when local movement suggestions were reasonable, the model frequently failed to form or sustain coherent long-horizon strategies, confirming the boundary of its zero-shot multimodal navigation capabilities.

These results somehow reflect the task difficulty taxonomy detailed in the previous section and indicate that multimodal inputs do improve LLM performance in zero-shot planning for navigation tasks, but only under conditions where the task complexity, environmental ambiguity, and perception-planning alignment are manageable. For tasks requiring deliberate spatial exploration, such as searching across the room or handling occluded targets, the LLM’s default reasoning process falls short. This highlights a critical limitation: while LLMs excel at commonsense reasoning and single-step decision-making, they lack built-in mechanisms for consistent spatial coverage or active exploration. LLMs should be equipped with standard exploration strategies, such as frontier-based or coverage-driven exploration algorithms, to better handle tasks that demand consistent and systematic environment traversal. Integrating these strategies would augment the LLM’s high-level decision-making with robust low-level exploration behaviors.

4.2. Comparison Between LLM-Generated Paths and Baselines Strategies

To better understand the efficiency of LLM-driven navigation, we compare the executed path length of the UGV with two baselines strategies. The Oracle represents the ideal trajectory: a direct, collision-free path from the starting pose to the target. The Frontier plus Shortest Path, instead, combines a classic frontier exploration strategy with a shortest-path planner, providing a strong algorithmic reference grounded in conventional robotic navigation techniques.

Table 2 reports the corresponding results. For each task, we compute the average path length of the UGV, the Oracle path length, their ratio (UGV/Oracle), the Frontier plus Shortest Path path length, and their ratio (UGV/Frontier plus Shortest Path). A ratio of 1 indicates optimal behavior, while higher values reflect additional detours, oscillations, or inefficient turning patterns. It is worth noting that the comparison has been done only on successful tasks. Moreover, since tasks 6 and 7 do not include a target, they have excluded from the comparison.

Tasks 1, 2, 4, and 5 exhibit ratios close to 1–2 relative to both baselines, indicating that in structurally simple scenarios the LLM can sometimes approximate efficient paths. These tasks mainly involve direct movement toward a clearly perceived target, which reduces ambiguity and allows the model’s decisions to align with the underlying shortest route.

For the majority of cases, Tasks 3, 8, 9, and 10, the UGV travels 2× to over 18× the optimal distance. This reflects the several weaknesses of LLM-based control, such as oscillatory movements, delayed or imprecise turning behavior, and difficulties interpreting spatial structure from multimodal input. These behaviors accumulate into substantial detours, explaining the inflated ratios.

Moreover, several tasks exhibit extremely large standard deviations (e.g., Task 1: ±76.93; Task 3: ±113.82; Task 8: ±212.50), signaling highly inconsistent behavior across trials. Such variability suggests that while the LLM may occasionally produce a nearly optimal sequence, it often diverges into inefficient or erratic paths.

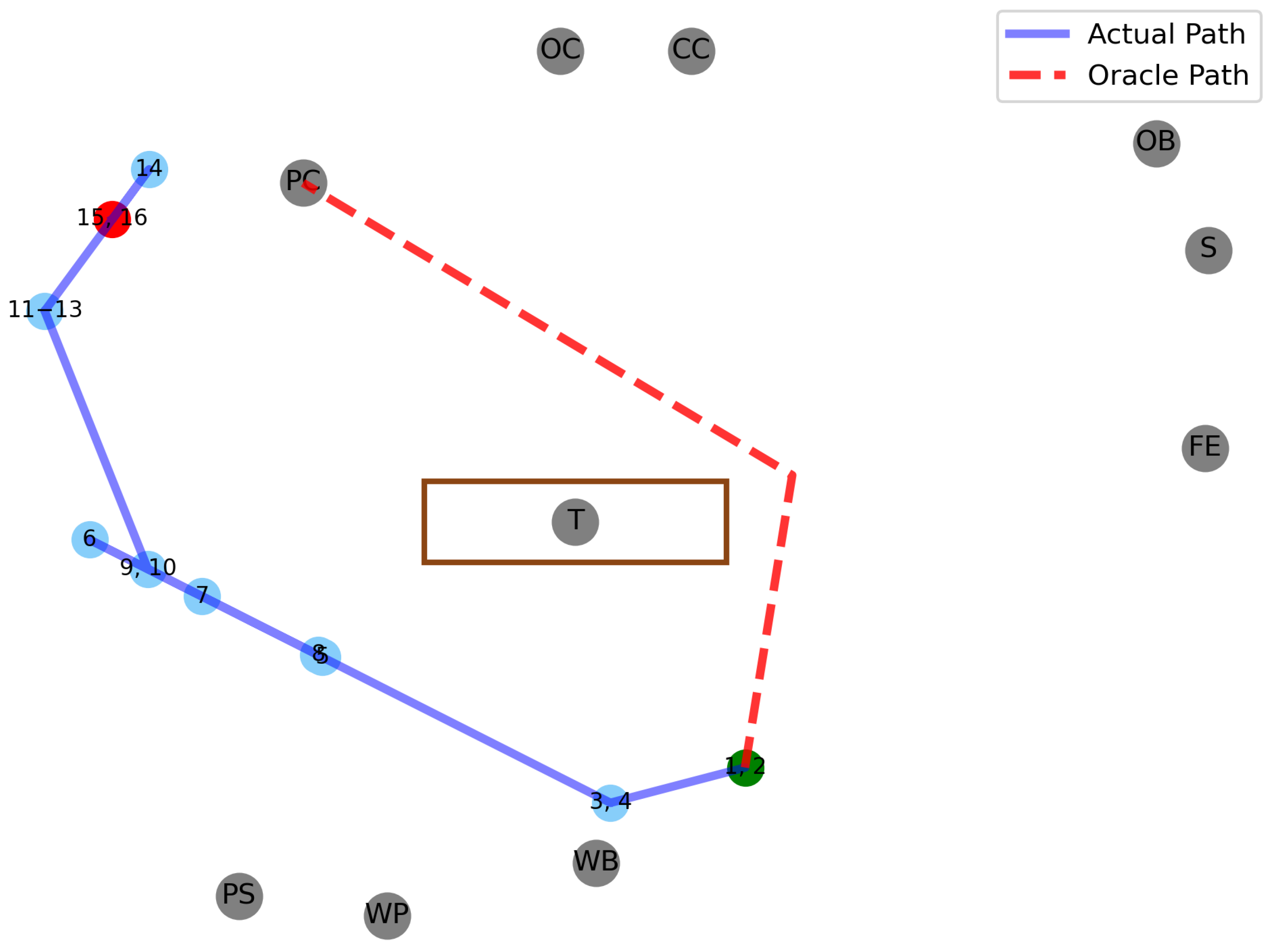

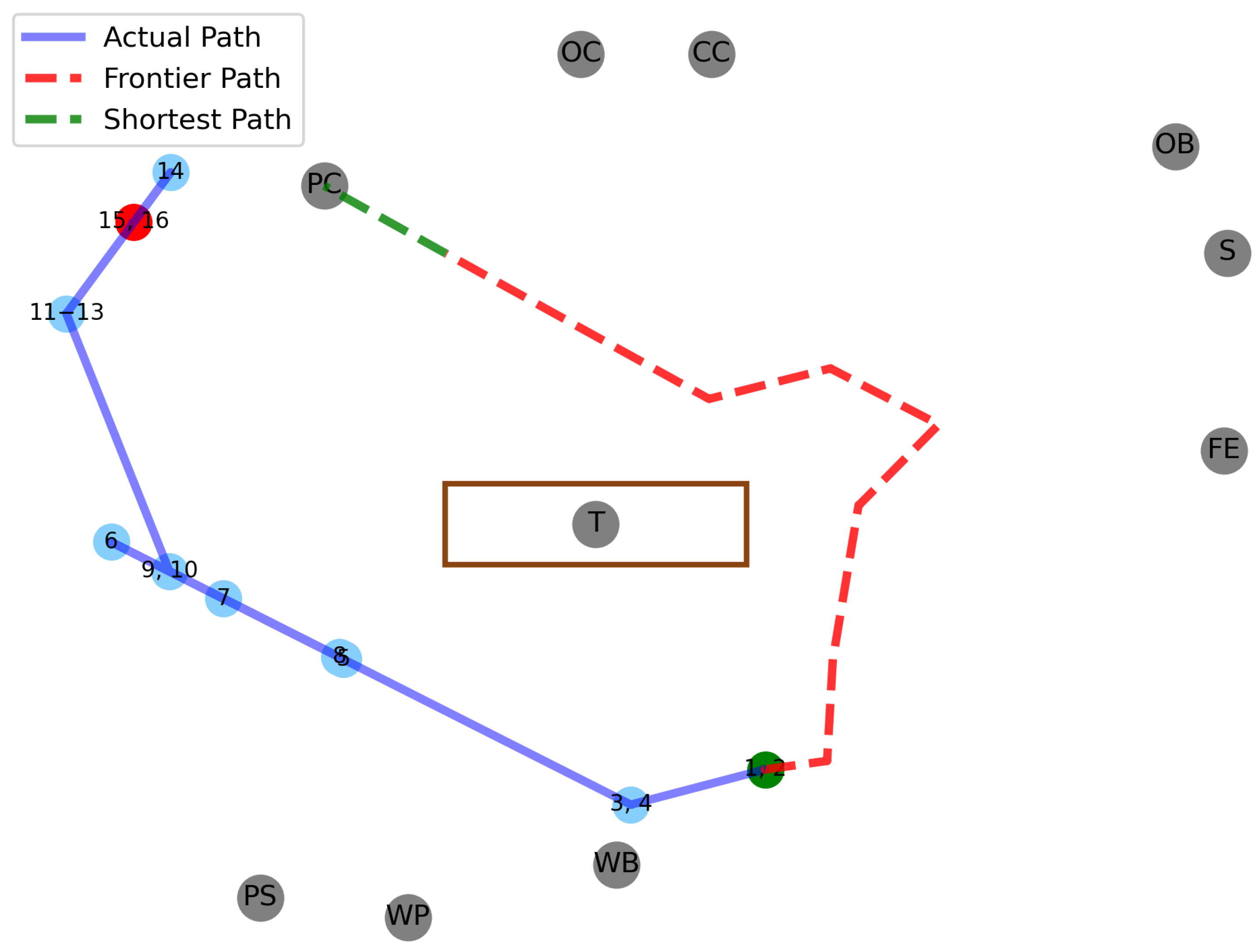

It is worth noting that in some cases (Tasks 2, 4, and 5), the average path length of the LLM is lower than the Frontier + Shortest Path baseline. This indicates that, despite its limitations, the LLM occasionally produces more direct or opportunistically efficient trajectories than a classical exploration-plus-planning pipeline. Such cases typically arise when the target is visually salient and directly interpretable from the LLM’s multimodal input, allowing it to select an efficient direction without engaging in the exploratory detours characteristic of frontier-based methods. These observations suggest that LLM-guided navigation can, at times, exploit scene semantics in ways that classical geometric strategies cannot, even if overall performance remains less consistent. To visualize these behaviors,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show representative trajectories for Tasks 1 and 2 compared with their respective Oracle paths, while

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 illustrate two examples on the same tasks of Frontier plus Shortest Path.

4.3. Ablation Study on Model Scale, Sensory Abstraction, Prompt Design, Sensing Modalities, and Memory Effect

To better understand which components most strongly influence the emergence of planning behaviors in LLM-driven navigation, we conduct a set of ablation studies targeting three key dimensions of the system: (i) the underlying model scale, (ii) the level of sensory abstraction applied to the LiDAR observations, and (iii) the structure and constraints embedded in the system prompt. These studies complement the main experiments by isolating how architectural choices (e.g., model size), perception encoding (number of LiDAR sectors), and prompt design (full vs. shortened instructions, with or without movement constraints) affect task completion, safety, and policy stability. The following subsubsections present the results of each ablation in isolation.

All ablation analyses were conducted using a representative task, chosen to balance difficulty and isolate the specific components under investigation. The ablations on model variation, system-prompt configuration, and history were performed on Task 3. This task belongs to the medium-difficulty category and, in our baseline experiments, Gemini 2.0 Flash (Google DeepMind) achieved 10 successful runs out of 20 with an average score of 0.41. This performance range provides sufficient room for both improvement and degradation, making Task 3 a suitable benchmark for evaluating changes in reasoning behavior induced by prompt structure or model choice.

In contrast, the ablation on LiDAR discretization was conducted on Task 8. Although Task 8 is also medium-difficulty, it offers several advantages for evaluating the effect of LiDAR resolution with respect to Task 3. First, Task 8 exhibits a strong dependence on spatial layout and geometric navigation: the robot must traverse a cluttered environment toward a distant set of visually similar boxes, making LiDAR information essential for identifying free space and avoiding obstacles. Second, the task typically generates longer trajectories with more intermediate directional decisions, increasing the sensitivity of the system to differences between 3, 5, and 8 angular LiDAR sectors. Third, Task 8 features a visually consistent and easily detectable target, reducing the influence of high-level visual ambiguity and ensuring that performance variations primarily reflect changes in LiDAR representation. For these reasons, Task 8 provides a more discriminative testbed for analyzing the contribution of LiDAR discretization to navigation performance.

4.3.1. Effect of Model Size on Zero-Shot Navigation Performance

To assess how the size of the foundational model impacts multimodal reasoning for navigation, we evaluated Gemini 2.0 Flash and its smaller variant Flash-Lite under identical simulation conditions and prompt configurations.

Table 3 summarizes the performance across Task 8, varying the initial position five times.

Overall, Gemini 2.0 Flash consistently outperformed Flash-Lite across all metrics, success rate, final-position score, and number of reasoning iterations, highlighting the importance of model capacity for maintaining coherent spatial reasoning over multiple decision cycles.

Across the five evaluated positions, Flash achieved higher success counts (10 vs. 7 in Flash-Lite) and substantially stronger final-position scores, particularly in Positions 1 and 4 (0.79 ± 0.30 and 0.63 ± 0.10), where the model successfully aligned perception with geometric constraints. In contrast, Flash-Lite frequently converged toward premature or incomplete plans, reflected in near-zero scores for Positions 2, 3, and 5. These failures illustrate the reduced model’s difficulty in maintaining consistent navigation hypotheses when spatial cues are ambiguous or require multi-step resolution.

Latency remained comparable across models, although Flash-Lite occasionally exhibited slightly higher variability. Importantly, neither model produced malformed outputs (#JSON = 0 across runs), and no safety triggers were activated, indicating that differences stem primarily from reasoning capability rather than output stability.

These findings show that larger models provide more robust planning, particularly in scenarios requiring iterative refinement or implicit spatial inference. Conversely, smaller models may suffice only when the required navigation behavior is simple, direct, or heavily grounded in the immediate sensory input.

4.3.2. LiDAR Discretization and Its Effect on Zero-Shot Spatial Reasoning

To assess the impact of perceptual granularity on the LLM-driven navigation pipeline, we evaluated three LiDAR discretization schemes, 3, 5, and 8 angular sectors, while keeping all other components (model, prompt, environment, and task set) fixed.

Table 4 reports performance across the same five initial positions.

A clear trend emerges: coarse LiDAR discretization (3 sectors) severely limits spatial reasoning, leading to near-zero success across most positions and consistently poor final-position scores. With only three directional bins, the model receives insufficient geometric structure to differentiate between obstacles, free-space directions, or relative target alignment. This often results in either ambiguous or oscillatory movement suggestions, and in one case, a triggered safety refusal.

Increasing the resolution to 5 sectors yields a noticeable improvement. Success counts rise across Positions 1–3, and the model produces moderately accurate final-position scores, particularly in Position 2 (0.45 ± 0.19) and Position 3 (0.24 ± 0.22). These results indicate that a mid-level discretization provides enough angular information for short-horizon spatial decisions, though performance remains inconsistent when tasks require precise directional disambiguation or multi-step corrections.

The 8-sector configuration consistently performs best, achieving the highest success counts and the strongest scores, including substantial gains in Positions 2 (0.46 ± 0.26) and 5 (0.65 ± 0.36). The richer angular structure allows the model to better infer free-space corridors, detect local minima, and align its motion plan with visually grounded target cues. However, performance is not uniformly superior: Position 3 exhibits lower scores despite correct outputs, suggesting that excessive discretization can occasionally introduce noise or lead to overfitting on short-range cues.

Overall, these results demonstrate that LiDAR granularity significantly influences the LLM’s capacity to maintain coherent spatial reasoning. While minimal discretization is insufficient for meaningful navigation, excessively fine segmentation does not guarantee uniform improvements. The 8-sector configuration offers the best overall balance, enabling the model to generalize more effectively across heterogeneous spatial layouts.

4.3.3. Impact of System Prompt Structure on Navigation Performance

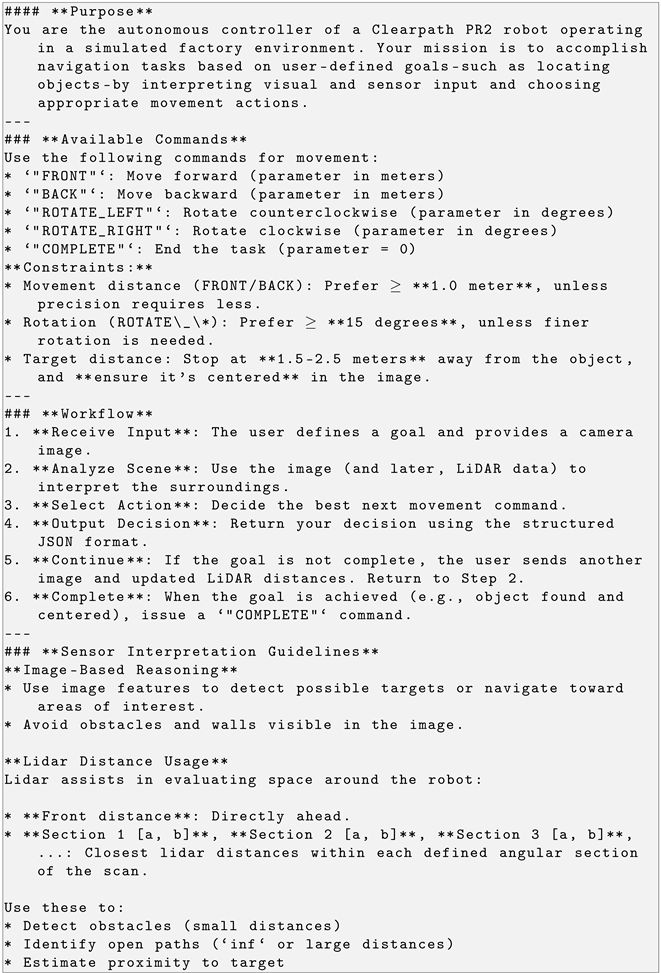

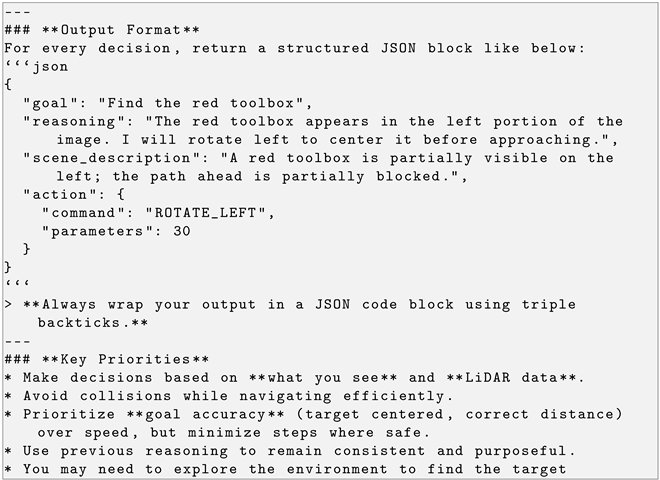

The system prompt plays a central role in shaping how LLMs interpret sensor readings and generate sequential decisions. To assess its influence, we compare six configurations: (i) Full prompt (main-experiment version), (ii) Full prompt without movement constraints, (iii) Short prompt, (iv) Short prompt without movement constraints (v) a version in which the LiDAR interpretation guidelines are removed, and (vi) a Self-Check prompt in which the model must verify the validity of every JSON response before proceeding. The shorter prompt is reported in Listing 6.

| Listing 6. Shorter version of the System Prompt. |

![Drones 09 00875 i007 Drones 09 00875 i007]() |

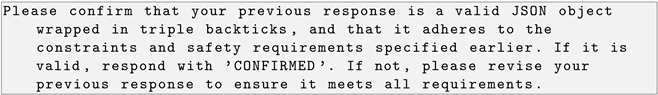

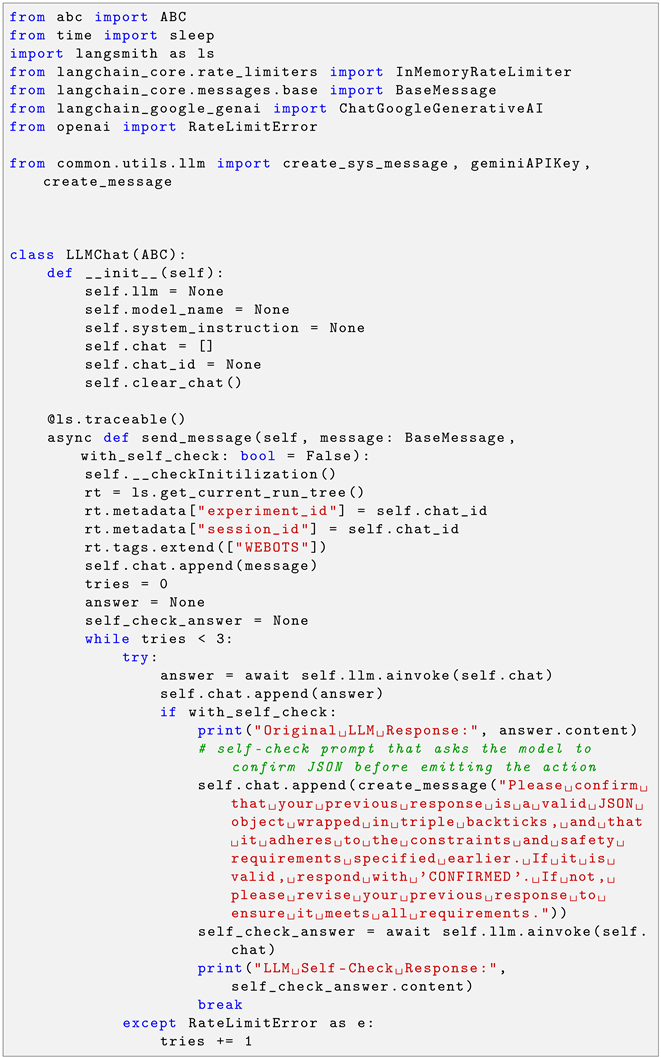

The full prompt contains explicit behavioral rules, detailed reasoning instructions, and command-format requirements. The short prompt preserves only essential task information, substantially reducing descriptive guidance. In the constraint-free variants, we remove rule-based limitations regarding allowed movements, enabling the model to choose any action at each step. In the No LiDAR guidelines, we simply removed such guidelines from the system prompt. Finally, in the Self-Check experiments, the prompt reported in Listing 7 is sent to the LLM after each iteration.

| Listing 7. Self-Check Prompt. |

![Drones 09 00875 i008 Drones 09 00875 i008]() |

Table 5 reports performance across the same initial positions.

With regard to the prompt length, the comparison between the full and short prompts shows no substantial difference in terms of overall Success. Both prompts allow the models to reliably complete the simpler positions (1 and 4), while struggling similarly on the more challenging ones (3 and 5). This indicates that reducing descriptive detail in the prompt does not critically impair the model’s ability to reach the goal. However, differences emerge in the Score metric, where the full prompt generally produces more stable and higher-scoring trajectories. This suggests that the additional structure in the full prompt primarily improves trajectory quality and policy consistency, rather than ultimate task completion.

Instead, removing the movement constraints leads to a significant shift in navigation behavior. Across both the full and short prompts, eliminating constraints introduces substantial instability: success rates drop sharply in several positions (most prominently Position 2), and variance increases in iteration counts and latency. While unconstrained prompts occasionally achieve faster resolutions in easier scenarios (e.g., Position 1), they generally fail to generalize reliably.

This result is particularly interesting because it highlights the role of constraints as an implicit inductive bias, they help guide the LLM toward consistent and safe action patterns. When constraints are removed, the model gains flexibility but loses behavioral regularity, leading to erratic or unsafe strategies, especially in geometrically complex layouts.

Removing high-level instructions on how the model should use LiDAR depth-sector information drops dramatically the performance across all starting positions except Position 5, with no successful trajectories and consistently near-zero scores. This indicates that unlike general prompt detail, LiDAR-specific behavioral instructions are necessary for effective spatial reasoning. Without them, the model tends to ignore or misinterpret obstacle layout, leading to frequent collisions or dead-end movements. The strong decline highlights the importance of providing modality-specific priors when the task requires spatial grounding.

Finally, the Self-Check configuration exhibits a markedly different pattern from the other prompt variants. Rather than inducing a uniform drop in performance, it produces highly heterogeneous outcomes across positions. The model performs well in some settings (e.g., Position 4: , Position 1: ), moderately in others (Position 2: ), and nearly fails in Positions 3 and 5 (both approaching zero). This suggests that the additional verification step does not consistently hinder the navigation loop, but instead introduces substantial positional instability.

Three mechanisms likely contribute to this variability. First, the requirement to validate the correctness of each JSON message introduces additional cognitive load, and the degree to which this interferes with task execution appears to depend on the spatial structure and perceptual demands of each starting position [

48]. Second, inserting a self-verification phase between perception and action disrupts the continuity of the control loop in a way that some configurations tolerate better than others, leading to inconsistent sensitivity to temporal fragmentation [

49]. Third, alternating between agent mode (issuing navigation commands) and validator mode (returning

CONFIRMED) introduces role-switching overhead that can either be absorbed or amplified depending on the spatial context and the required reasoning depth [

50].

4.3.4. Impact of Sensing Modality

To assess the contribution of depth-aware geometric information to LLM-driven navigation, we compare two sensing configurations: the multimodal setup combining LiDAR and vision (used in all other experiments), and a vision-only baseline. The former provides the model with coarse geometric cues derived from sectorized LiDAR ranges, while the latter relies exclusively on image input.

Table 6 summarizes quantitative results across all initial positions.

Overall, the multimodal configuration demonstrates more robust performance. It achieves higher Success rates in four out of five positions and consistently yields higher trajectory Scores, indicating more stable, goal-directed motion. This advantage is most pronounced in Positions 1 and 2, where the addition of LiDAR appears to help the model avoid ambiguous or unsafe forward motions. In more challenging layouts (e.g., Position 3), both configurations struggle.

Interestingly, the vision-only system matches or marginally outperforms the multimodal setup in an isolated case (Position 4), where it achieves a near-optimal Score. This suggests that when visual structure is clear and the environment is free of occlusions, RGB cues alone may suffice for consistent navigation. However, the reduced Success in other positions highlights the susceptibility of the vision-only configuration to depth ambiguities, especially in cluttered or geometrically constrained layouts.

4.3.5. Effect of History Conditioning on Performance

In this ablation, we assess how different amounts of historical context influence the decision-making performance of the LLM. Four configurations are compared: providing no history, one previous step, two previous steps, or the full trajectory history. Note that, as anticipated, the full-history configuration is the one used in the experiments. The quantitative results are reported in

Table 7.

When no history is supplied, the model must rely exclusively on the current multimodal observation. This often leads to short-sighted or inconsistent behaviours, reflected by generally low scores and limited task success. Supplying one or two previous steps results in small improvements for certain tasks, but the impact remains limited and unstable across the entire benchmark.

The best performance is achieved when conditioning on the full trajectory history. This setting enables the LLM to maintain coherent long-horizon plans, recover from ambiguous states, and interpret the evolution of its past actions and observations. Notably, success rates increase substantially for Tasks 1, 2, and 4, confirming that temporal context is crucial for robust navigation and reasoning.