Conceptual Development of Terminal Airspace Integration Procedures of Large Uncrewed Aircraft Systems at Non-Towered Airports †

Highlights

- Analyzing the interaction of several quantitative measures (e.g., average traffic density, flight time, and flight distance) in different altitude bands provides an initial picture to structure crewed flight behavior at non-towered airports.

- Holding options above the airport traffic pattern may present feasible integration solutions for UAS, but holding altitudes vary significantly based on the airport’s surrounding topography, airspace classes, present aircraft types, and crewed flight behavior.

- A variety of factors influence the development of an internationally harmonized “one size fits all” approach for UAS integration, including advancements related to UAS flight rules, DAA capabilities, and UAS traffic management solutions.

- The development of standards and regulations is crucial to derive “ideal” solutions for the integration of UAS, determining where, when, and how to integrate UAS with crewed traffic in and around traffic patterns of non-towered airports.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- First, how could UAS be procedurally integrated into the terminal airspace of non-towered airports, especially with crewed aircraft in the airport vicinity?

- Second, how might crewed aircraft track history inform UAS flight planning and UAS procedural integration options at non-towered airports?

2. Background: Airborne Integration at Non-Towered Airports

2.1. Current Terminal Airspace Integration Procedures of Crewed Aircraft

2.1.1. Flight Rules and Meteorological Conditions

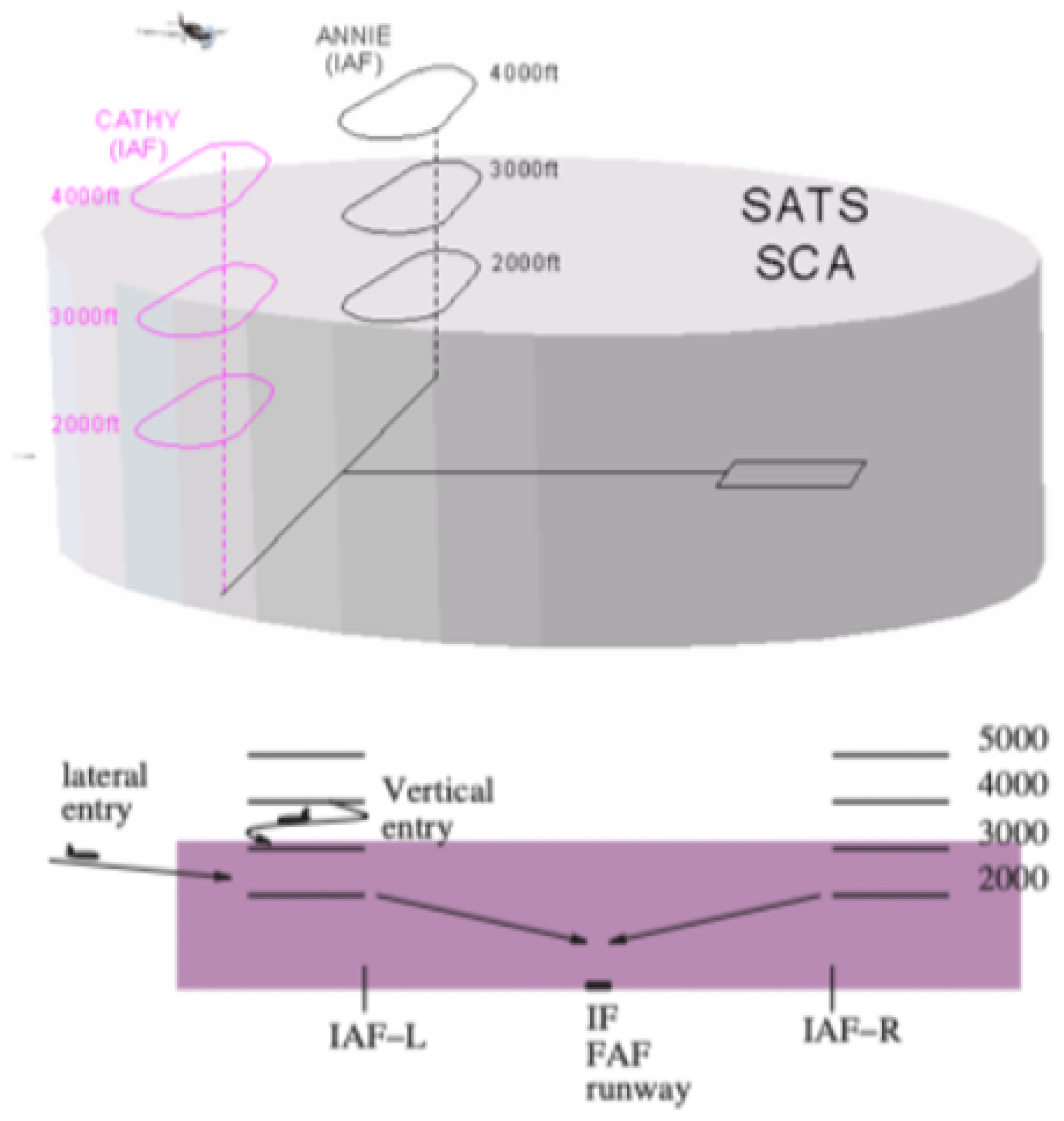

2.1.2. Integration of Crewed Aircraft Under IMC

2.1.3. Integration of Crewed Aircraft Under VMC

2.2. Initial Terminal Airspace Integration Concepts to Enhance Efficiency

2.2.1. High Traffic Volume Operational Concepts

2.2.2. Initial Terminal Airspace Integration Concepts for UAS

2.3. Hurdles for Terminal Airspace Integration of UAS

2.3.1. Landing

2.3.2. See and Avoid

2.3.3. Lost C2 Link

2.4. Theoretical Integration Procedures of UAS

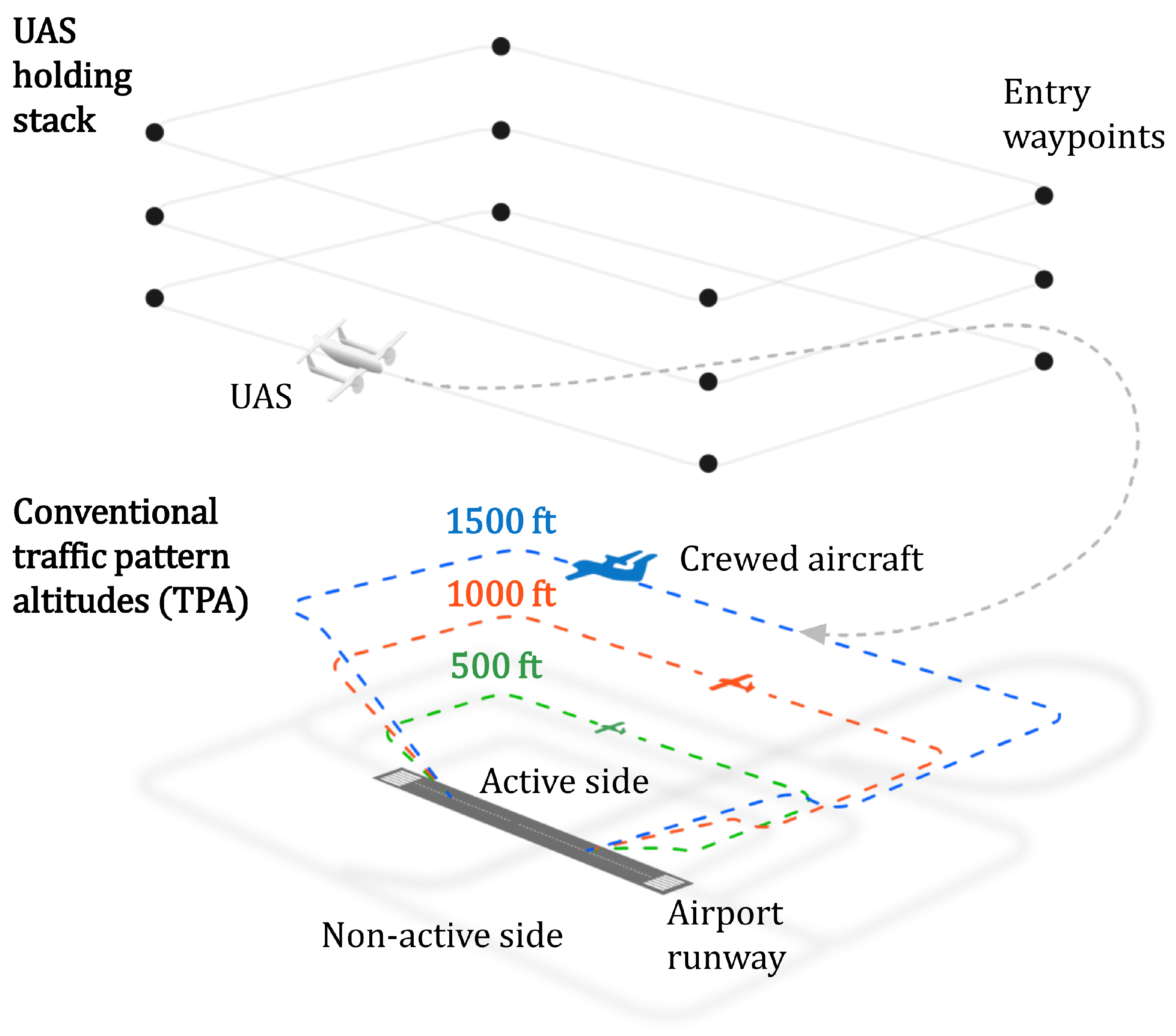

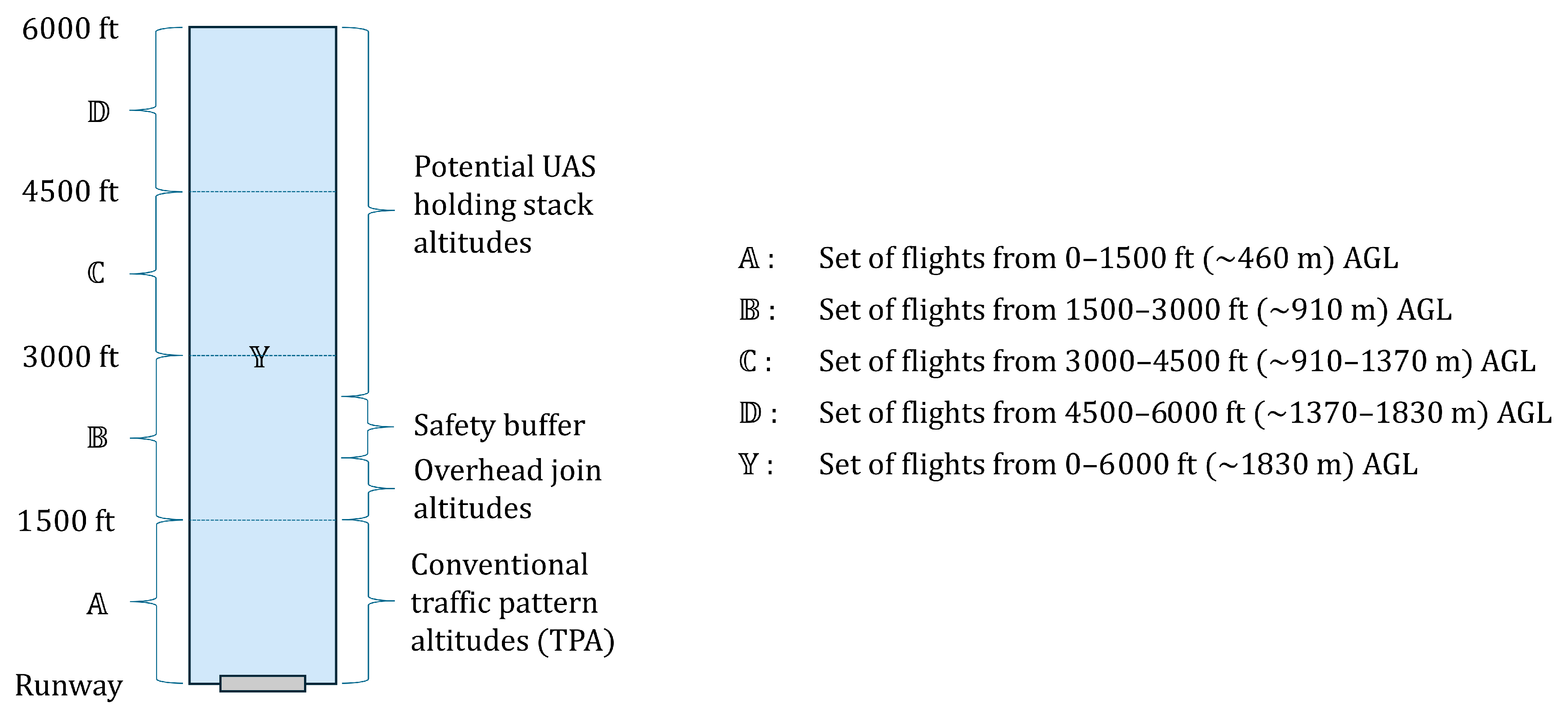

3. UAS Holding Stack Concept and Methodology

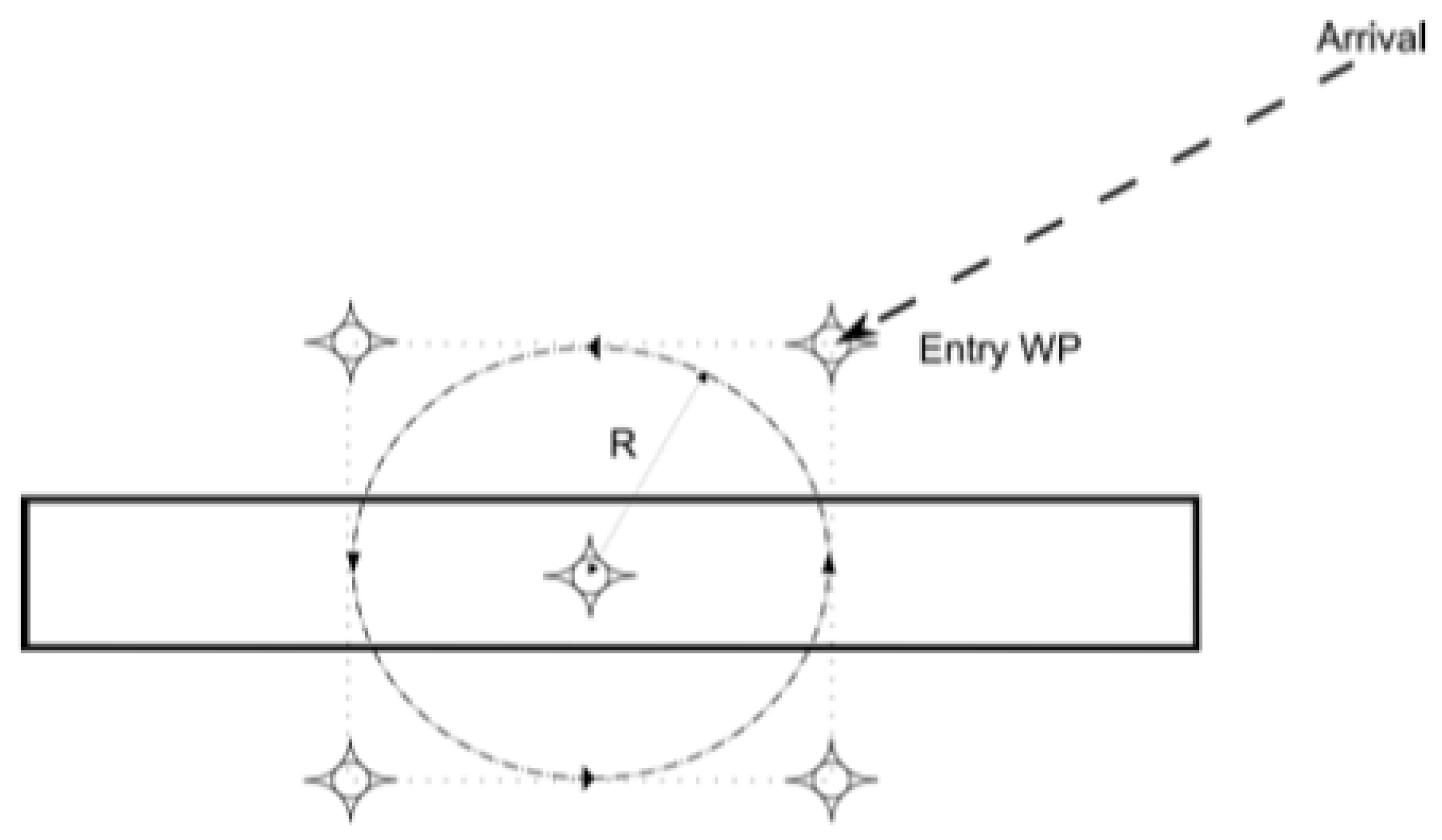

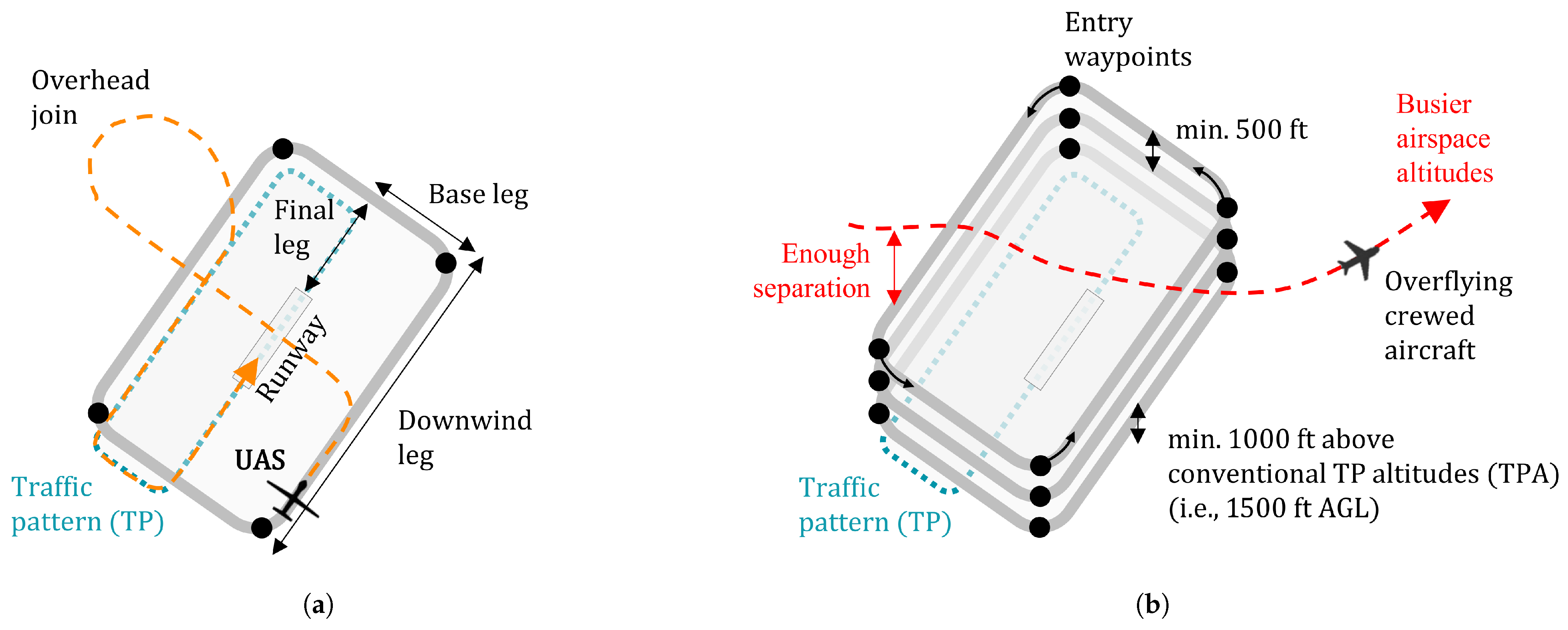

3.1. Terminal Airspace and Procedure Design

- Vertical Distance (VD) from holding into TPA, 1900 ft (∼580 m),

- Assumed Rate of Descent (ROD), 800 ft (∼240 m) per min,

- Assumed indicated airspeed of an aircraft, 90 kn (∼2.78 km per min).

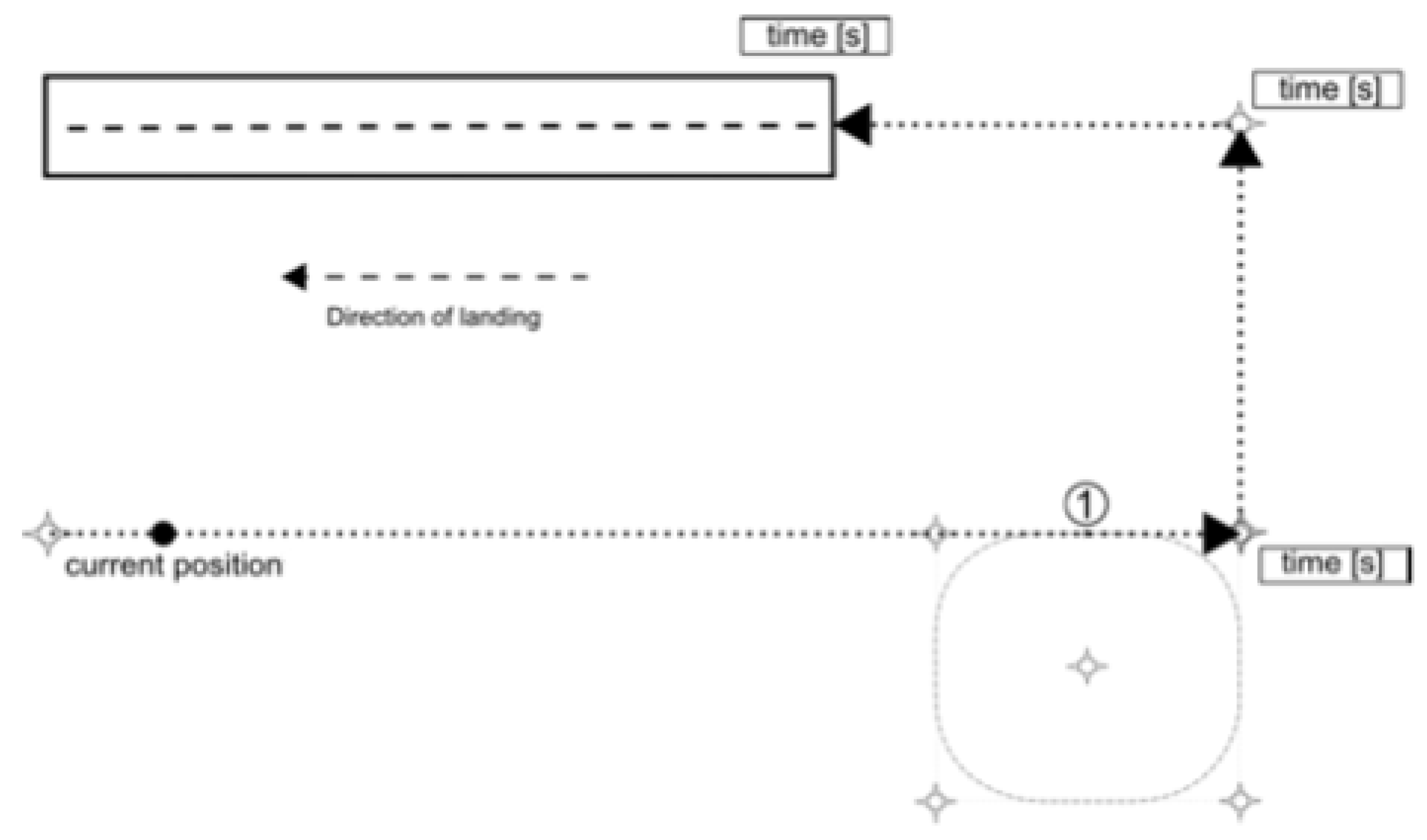

3.2. Conceptual Operating Scheme of UAS Flight Planning at Non-Towered Airports

- Assessment of airspace environment of non-towered airportsThe first step for integrating UAS into non-towered environments is the assessment and spatial definition of the main operating environment (Section 4.1), namely the volume of the airspace that surrounds historically flown TPs, referred to as “TP airspace” in the following.

- Assessment of flight behaviors of airspace usersSecond, after systematically identifying the bounds of where crewed traffic has historically flown the TP (i.e., TP airspace), flight behaviors are assessed using different quantitative measures (Section 4.2).

- Assessment of locations for UAS holding stackThird, after investigating crewed flight metrics and traffic densities, locations in and above the TP airspace are investigated to derive potential UAS holding stack locations, exemplified for different airports of interest (Section 4.3).

4. Analysis of Flight Track Data Around Non-Towered Airports

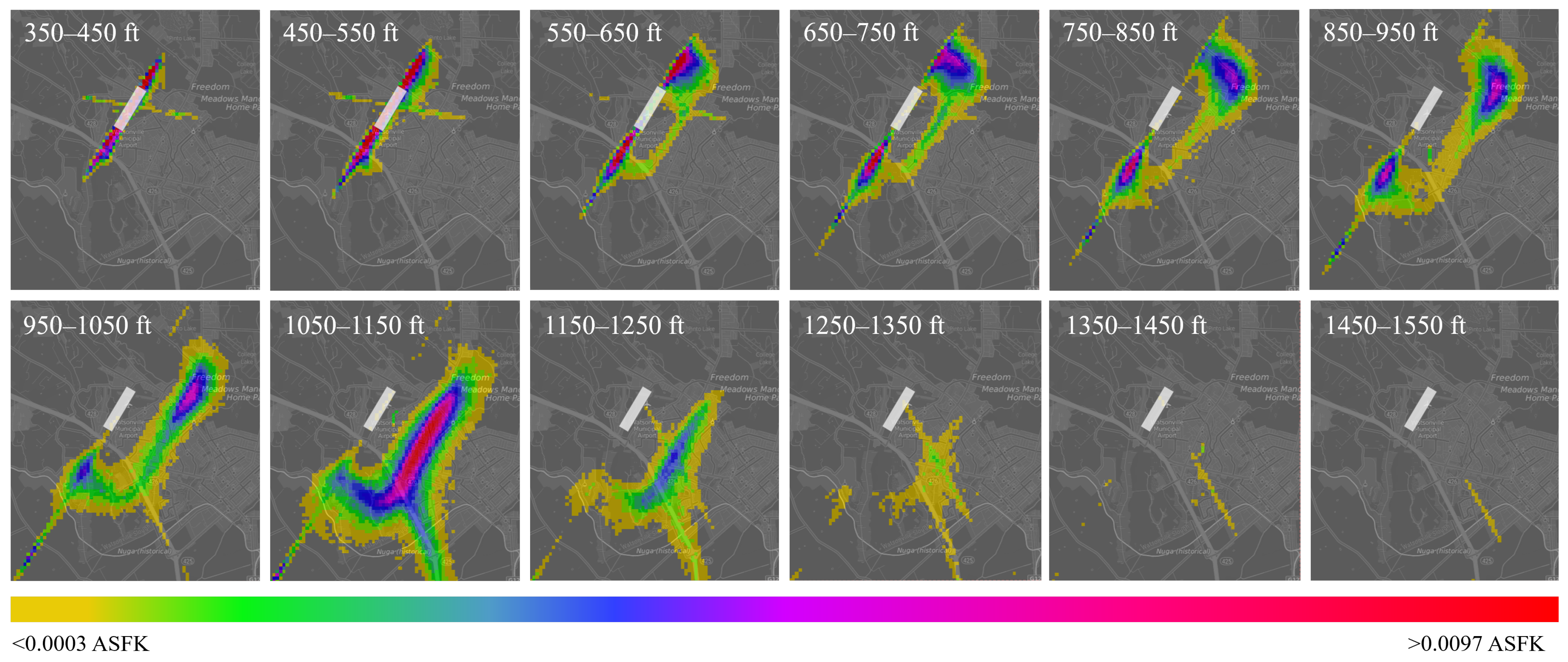

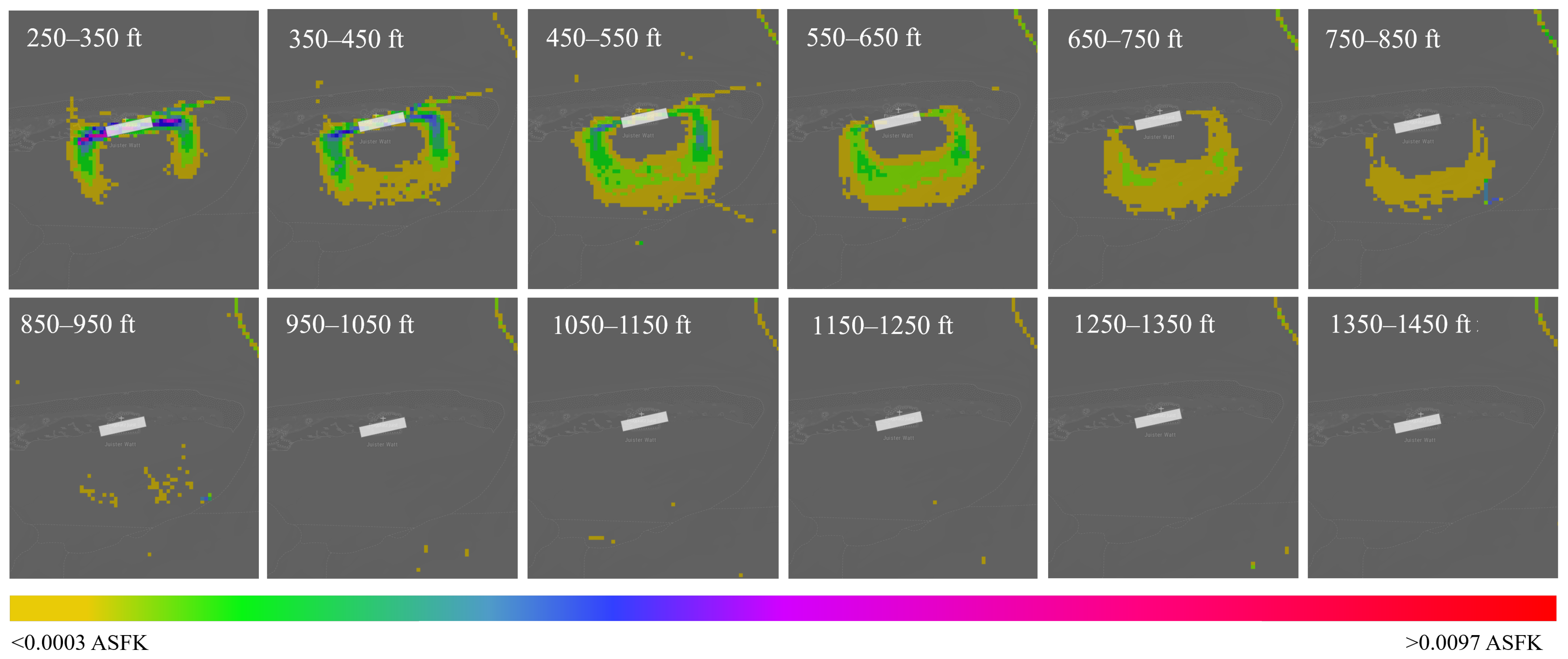

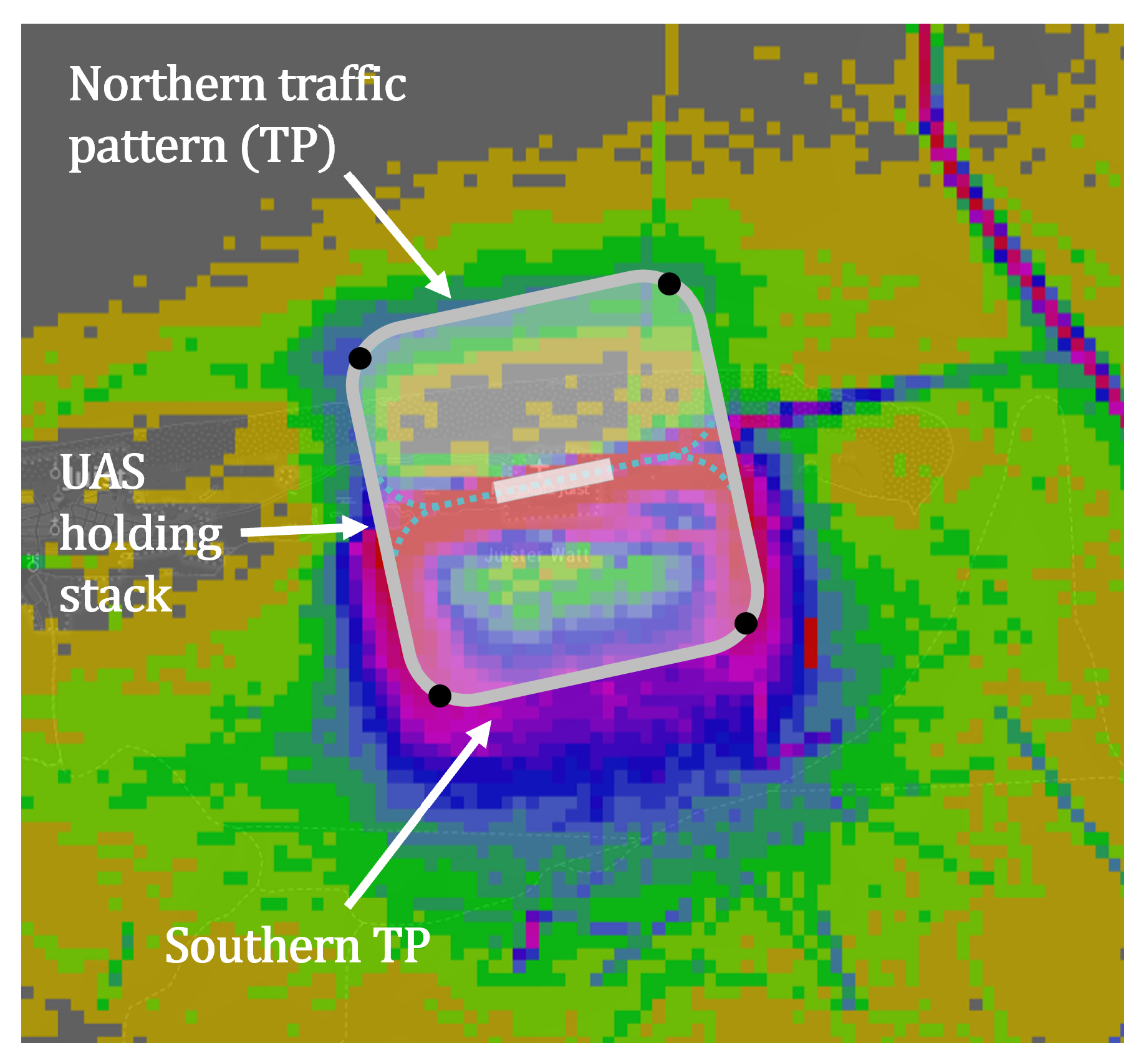

4.1. Assessment of Airspace Environment of Non-Towered Airports

4.1.1. Data Selection

4.1.2. Vertical Bounding of the TP Airspace

- : Flight time spent by flights in the cell over the observation period,

- : Area of the spatial cell , e.g., 0.01 ,

- : Duration of the observation period , e.g., one year .

4.1.3. Horizontal Bounding of the TP Airspace

4.2. Assessment of Flight Behaviors of Airspace Users

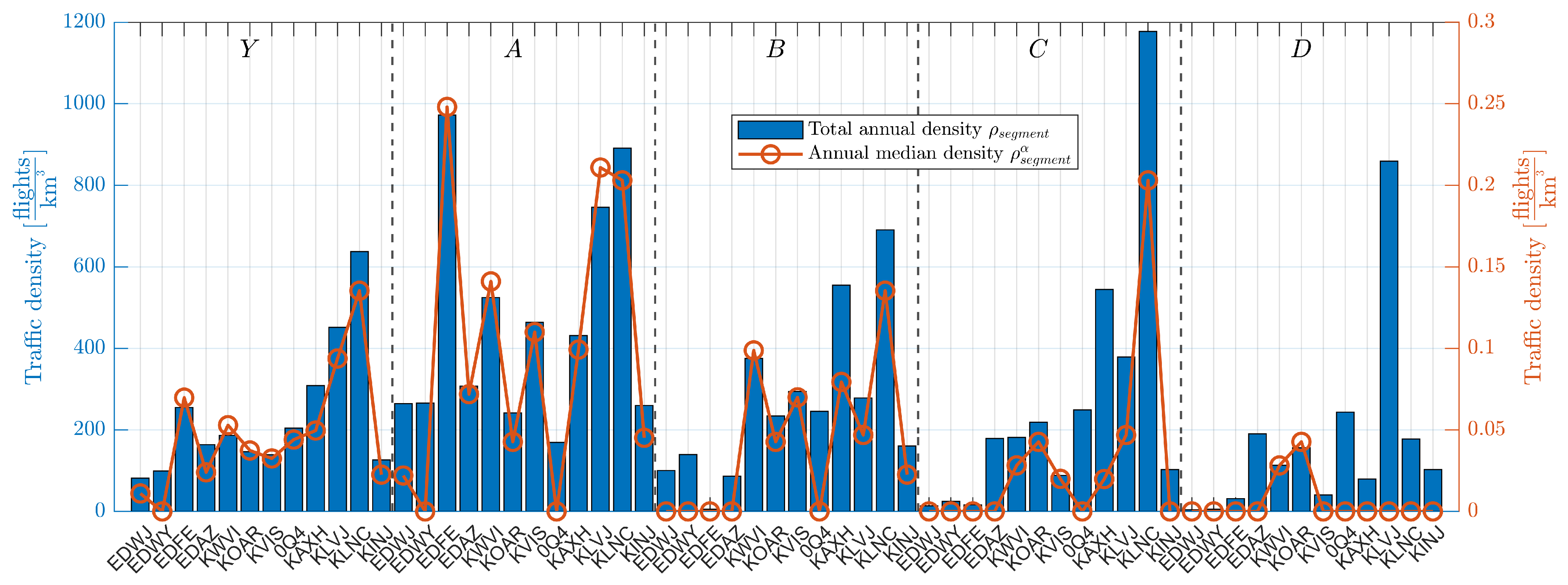

4.2.1. Analysis of Crewed Traffic Shares and Densities in TP Airspace

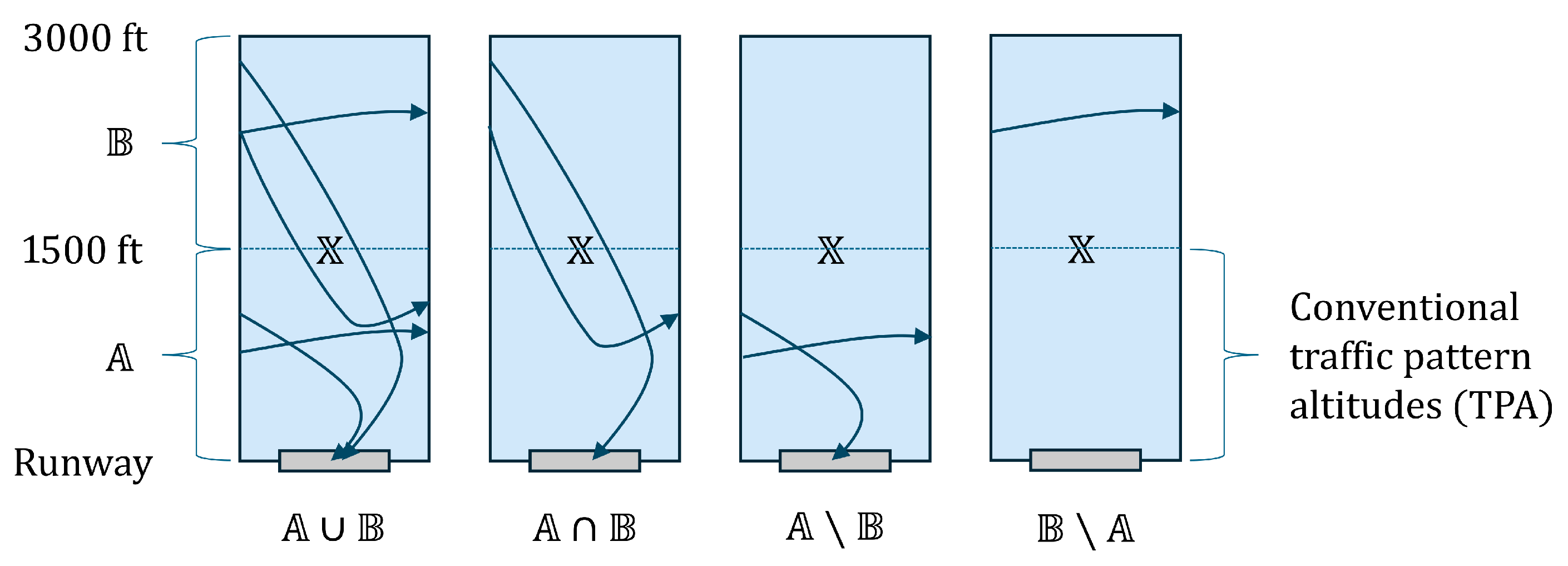

- Set of flights from 0–1500 ft (∼460 m) AGL;

- Set of flights from 1500–3000 ft (∼460–910 m) AGL;

- Set of flights from 0–3000 ft (∼910 m) AGL.

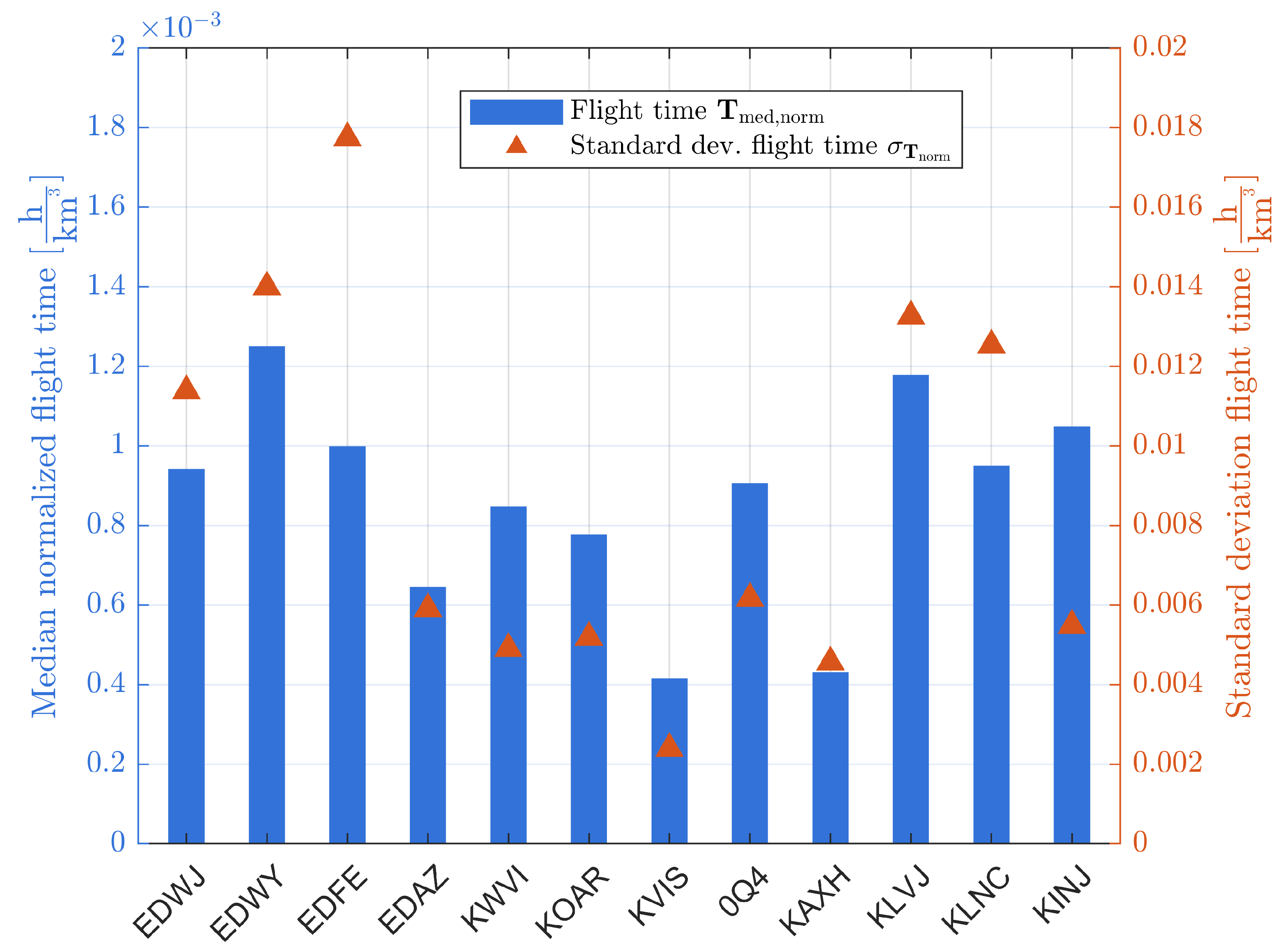

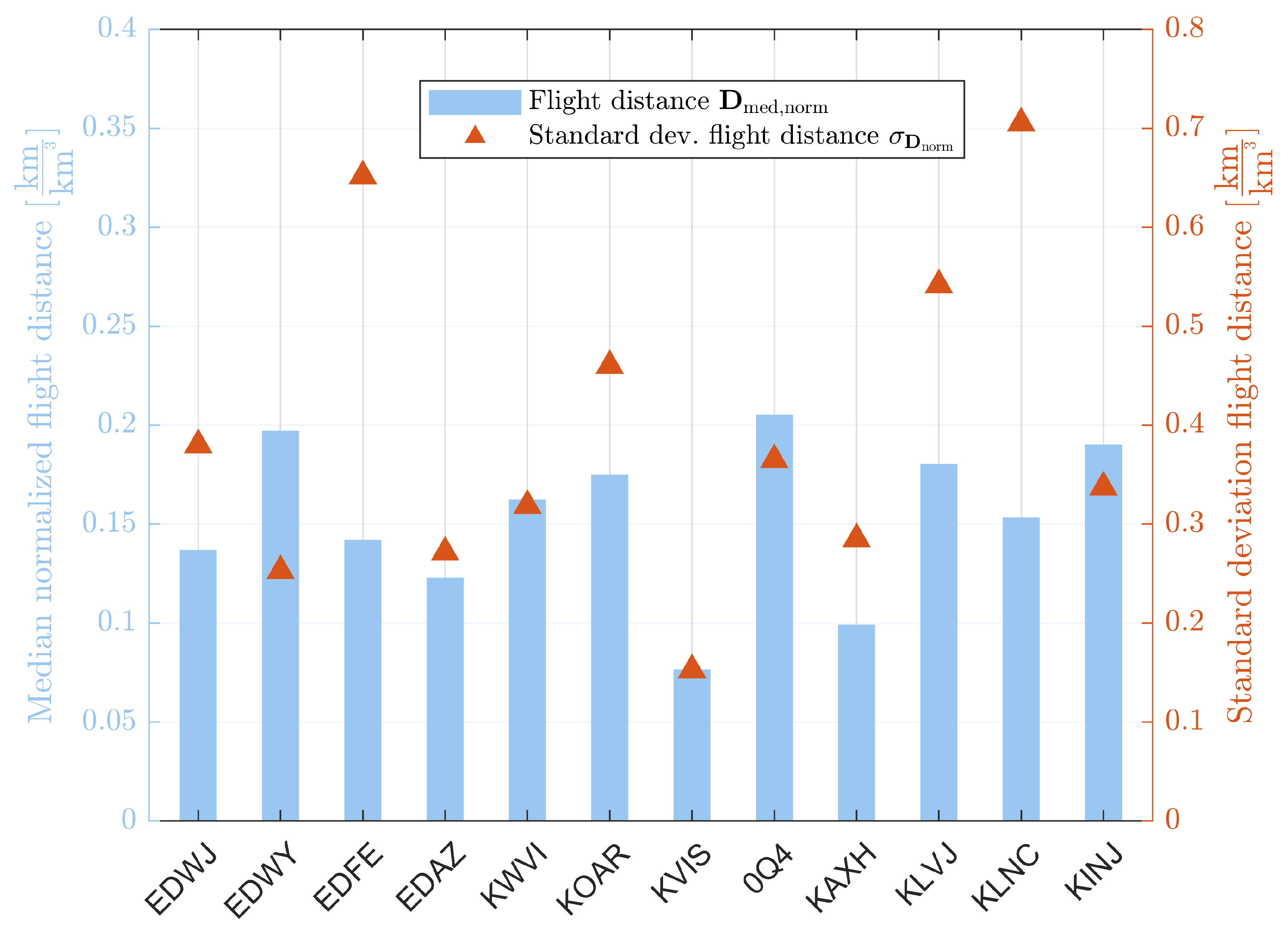

4.2.2. Analysis of Crewed Flight Metrics in TP Airspace

4.3. Assessment of Locations for UAS Holding Stack in and Above TP Airspace

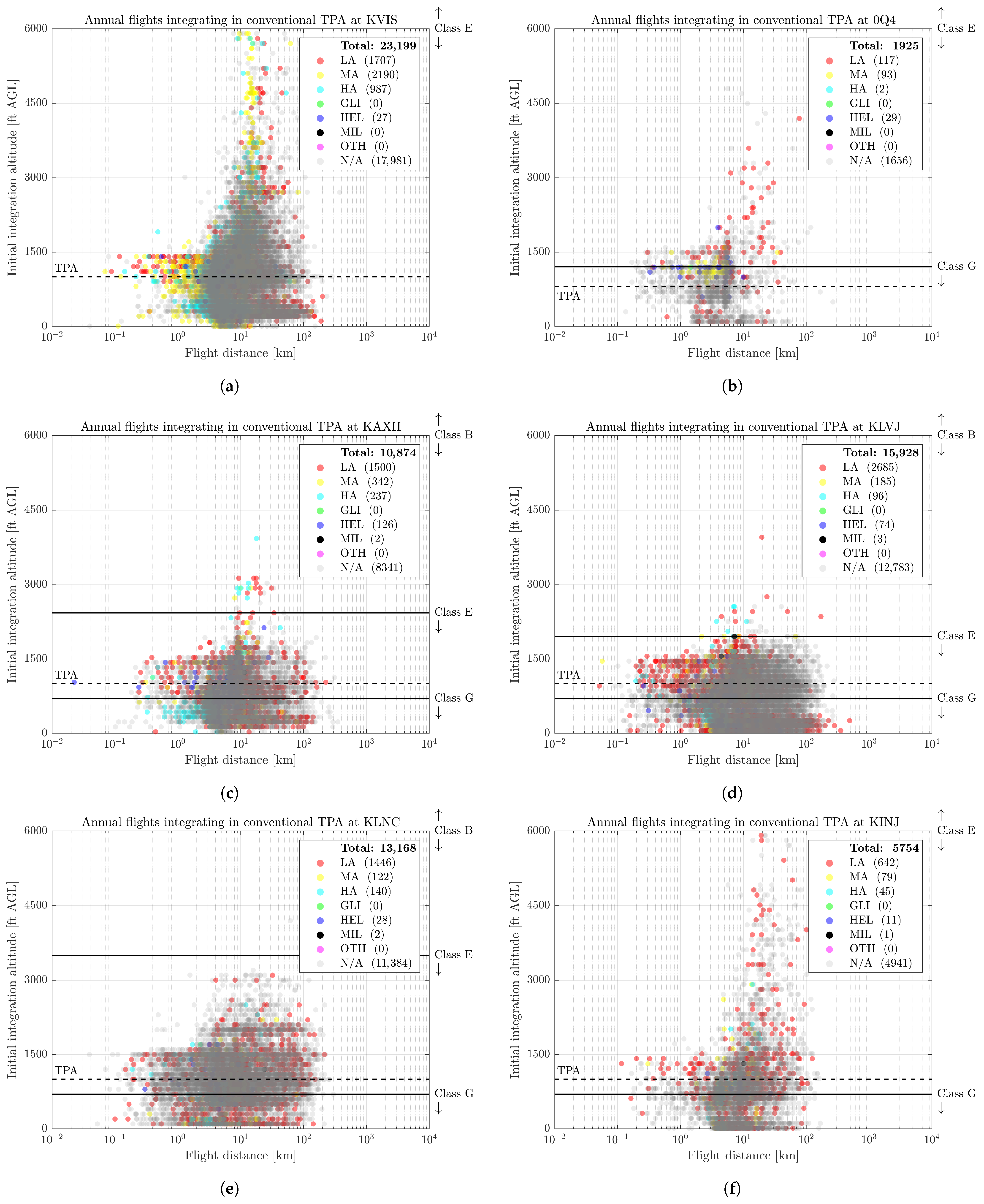

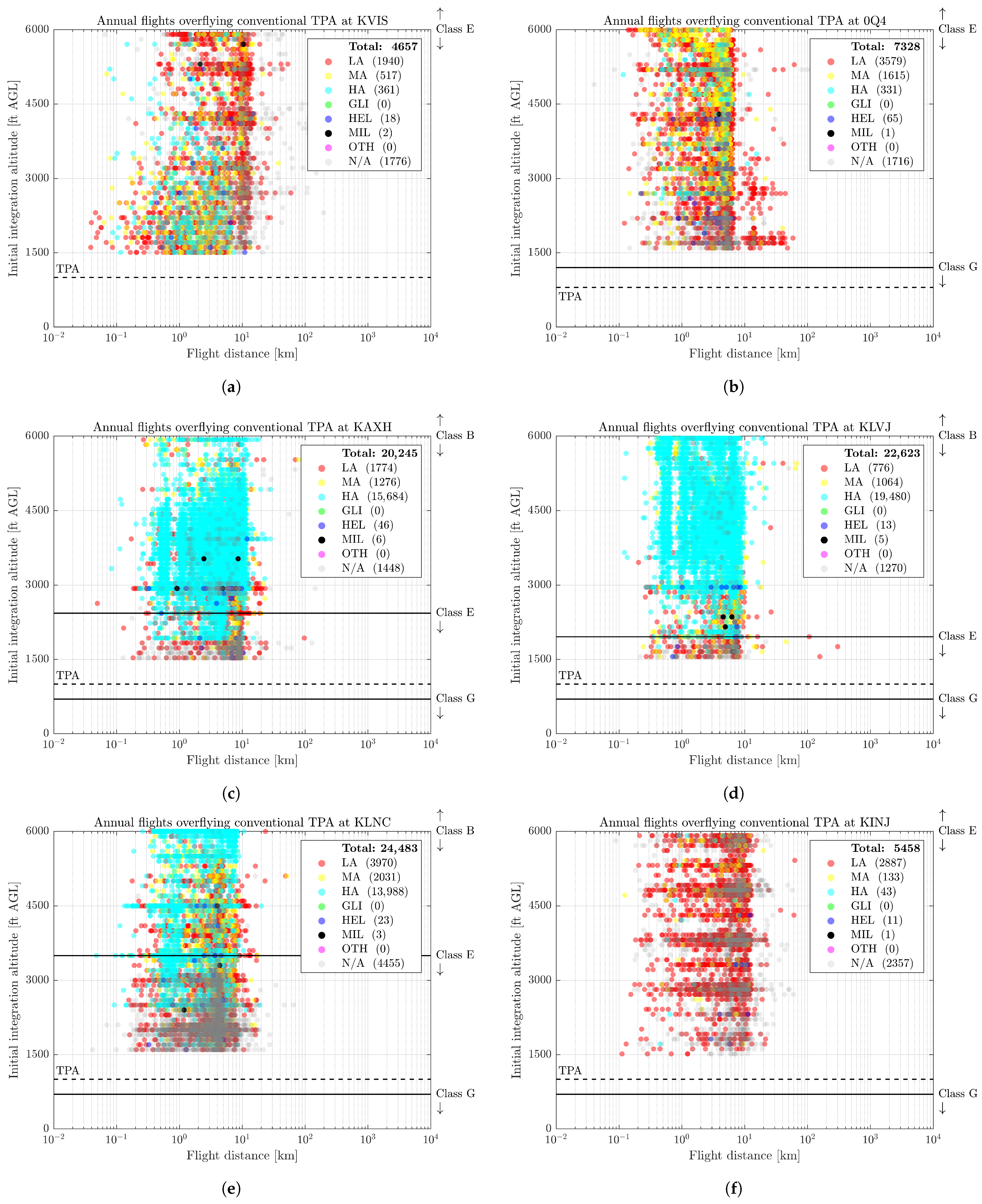

- LA: “Light-weight” civilian fixed-wing aircraft with t MTOW;

- MA: “Medium-weight” civilian fixed-wing aircraft with – t MTOW;

- HA: “Heavy-weight” civilian fixed-wing aircraft with t MTOW;

- GLI: Non-motor-driven civilian fixed-wing aircraft such as gliders;

- HEL: Civilian rotary-wing aircraft such as helicopters;

- MIL: Military fixed-wing and rotary-wing aircraft;

- OTH: Other aircraft such as balloons or gyrocopters;

- N/A: Aircraft with a missing type designator.

- Total annual flights in and above the TP airspace;

- Annual flights integrating into the conventional TPA;

- Annual flights overflying the conventional TPA.

4.4. Determining UAS Behavior for TP Integration

- High variation of crewed aircraft performances: High variations in crewed aircraft types with varying performances across altitude bands make it challenging to predict aircraft intent to determine safe and efficient flight paths for UAS.

- High uncertainty of crewed flight intents: High standard deviations of crewed flight metrics make state-based intent prediction of crewed aircraft more challenging.

- Dense population across altitude bands: A high number of flights across different altitude bands increases the risk of interaction between crewed and uncrewed aircraft. This reduces the number of potential holding stack layers in these altitude bands, making holdings for UAS above the TPA less feasible.

- Long integration distances into the TP: High vertical holding altitudes result in high vertical integration distances for UAS from their holding position into the TP. This could imply that a holding stack next to the TP airspace might be safer and more efficient for individual airports.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACAS | Airborne Collision Avoidance System |

| ADS-B | Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast |

| AGL | Above Ground Level |

| AMM | Airport Management Module |

| ASFK | Average Number of Simultaneous Flights per Square Kilometer |

| ATC | Air Traffic Control |

| ATM | Air Traffic Management |

| ATZ | Aerodrome Traffic Zone |

| C2 | Command and Control |

| CA | Collision Avoidance |

| ConOps | Concept of Operations |

| DAA | Detect and Avoid |

| DAR | Dynamic Airspace Reconfiguration |

| DLR | German Aerospace Center |

| EASA | European Union Aviation Safety Agency |

| eVTOL | electric Vertical Takeoff and Landing |

| FAA | Federal Aviation Administration |

| FAF | Final Approach Fix |

| FL | Flight Level |

| HD | Horizontal Distance |

| IAF | Initial Approach Fix |

| IAP | Instrument Approach Procedure |

| ICAO | International Civil Aviation Organization |

| IF | Intermediate Fix |

| IFR | Instrument Flight Rules |

| IMC | Instrument Meteorological Condition |

| ILS | Instrument Landing System |

| GBSS | Ground-Based Surveillance System |

| LC2L | Lost Command and Control Link |

| MLAT | Multilateration |

| MSL | Mean Sea Level |

| MTOW | Maximum Takeoff Weight |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| RAM | Regional Air Mobility |

| RMZ | Radio Mandatory Zone |

| ROD | Rate of Descent |

| RP | Remote Pilot |

| SATS | Small Aircraft Transportation System |

| SCA | Self-Controlled Area |

| SID | Standard Instrument Departure Route |

| STAR | Standard Terminal Arrival Route |

| TCA | Terminal Control Area |

| TMA | Terminal Maneuvering Area |

| TMZ | Transponder Mandatory Zone |

| TP | Traffic Pattern |

| TPA | Traffic Pattern Altitude |

| UA | Uncrewed Aircraft |

| UAS | Uncrewed Aircraft System |

| US | United States |

| USSP | U-Space Service Provider |

| VD | Vertical Distance |

| VFR | Visual Flight Rules |

| VHF | Very High Frequency |

| VMC | Visual Meteorological Condition |

| VOC | Visual Operating Chart |

| WP | Waypoint |

Appendix A

References

- Andrews, J.; Lara, M.; Yon, R.; Del Rosario, R.; Block, J.; Davis, T.; Hasan, S.; Weingart, D.; Frankel, C.; Spitz, B.; et al. LMI Automated Air Cargo Operations Market Research and Forecast; NASA Contractor Report-20210015228; NASA Ames Research Center: Moffett Field, CA, USA, 2021.

- Sievers, T.F.; Sakakeeny, J.; Dimitrova, N.; Idris, H. Operational integration potential of regional uncrewed aircraft systems into the airspace system. CEAS Aeronaut. J. 2025, 16, 1037–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, R. Regional Air Mobility: Infrastructure Challenges, Passenger and Cargo Market Potential, and Sustainability Strategies for Underserved Airports; NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS) Document ID 20250002542; NASA Langley Research Center: Hampton, VA, USA, 2025.

- Hayashi, M.; Idris, H.; Sakakeeny, J.; Jack, D. PAAV Concept Document; White Paper; NASA Ames Research Center: Moffett Field, CA, USA, 2022.

- Antcliff, K.; Borer, N.; Sartorius, S.; Saleh, P.; Rose, R.; Gariel, M.; Oldham, J.; Courtin, C.; Bradley, M.; Roy, S.; et al. Regional Air Mobility: Leveraging Our National Investments to Energize the American Travel Experience; White Paper; NASA Langley Research Center: Hampton, VA, USA, 2021.

- EUROCONTROL. Trends in Air Traffic—Volume 3. A Place to Stand: Airports in the European Air Network. Available online: https://www.eurocontrol.int/sites/default/files/publication/files/tat3-airports-in-european-air-network.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Bulusu, V.; Idris, H.; Chatterji, G. Analysis of VFR traffic uncertainty and its impact on uncrewed aircraft operational capacity at regional airports. In Proceedings of the AIAA Aviation 2023 Forum, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–16 June 2023; p. 3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMinn, J.D.; Patterson, A.; Gregory, I. Traffic Prediction for Uncommunicative Aircraft in Terminal Airspace: Development Framework and Performance Evaluations. In Proceedings of the 2025 AIAA SCITECH Forum, Orlando, FL, USA, 6–10 January 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, T.F.; Peinecke, N. Navigating the Uncertain: Integrating Uncrewed Aircraft Systems at Airports in Uncontrolled Airspace. In Proceedings of the 2024 Integrated Communications, Navigation and Surveillance Conference (ICNS), Herndon, VA, USA, 23–25 April 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, T.F.; Sakakeeny, J.; Idris, H.; Peinecke, N.; Bulusu, V.; Nagel, E.; Jack, D. A Concept for Procedural Terminal Area Airspace Integration of Large Uncrewed Aircraft Systems at Non-Towered Airports. In Proceedings of the First US-Europe Air Transportation Research & Development Symposium (ATRDS2025), Prague, Czech Republic, 24–27 June 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Certified Category—Civil Drones. Available online: https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/domains/drones-air-mobility/operating-drone/certified-category-civil-drones (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Pilot/Controller Glossary. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/pcg_html/ (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- US Government. 14 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 91.113. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/chapter-I/subchapter-F/part-91/subpart-B/subject-group-ECFRe4c59b5f5506932/section-91.113 (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- DFS Deutsche Flugischerung. Luftfahrthandbuch Deutschland. Available online: https://aip.dfs.de/basicAIP/ (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Airplane Flying Handbook: FAA-H-8083-3C (2024). Available online: https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/handbooks_manuals/aviation/airplane_handbook (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM). Official Guide to Basic Flight Information and ATC Procedures. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/media/AIM-Basic-w-Chg1-and-Chg2-dtd-3-21-24.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2025).

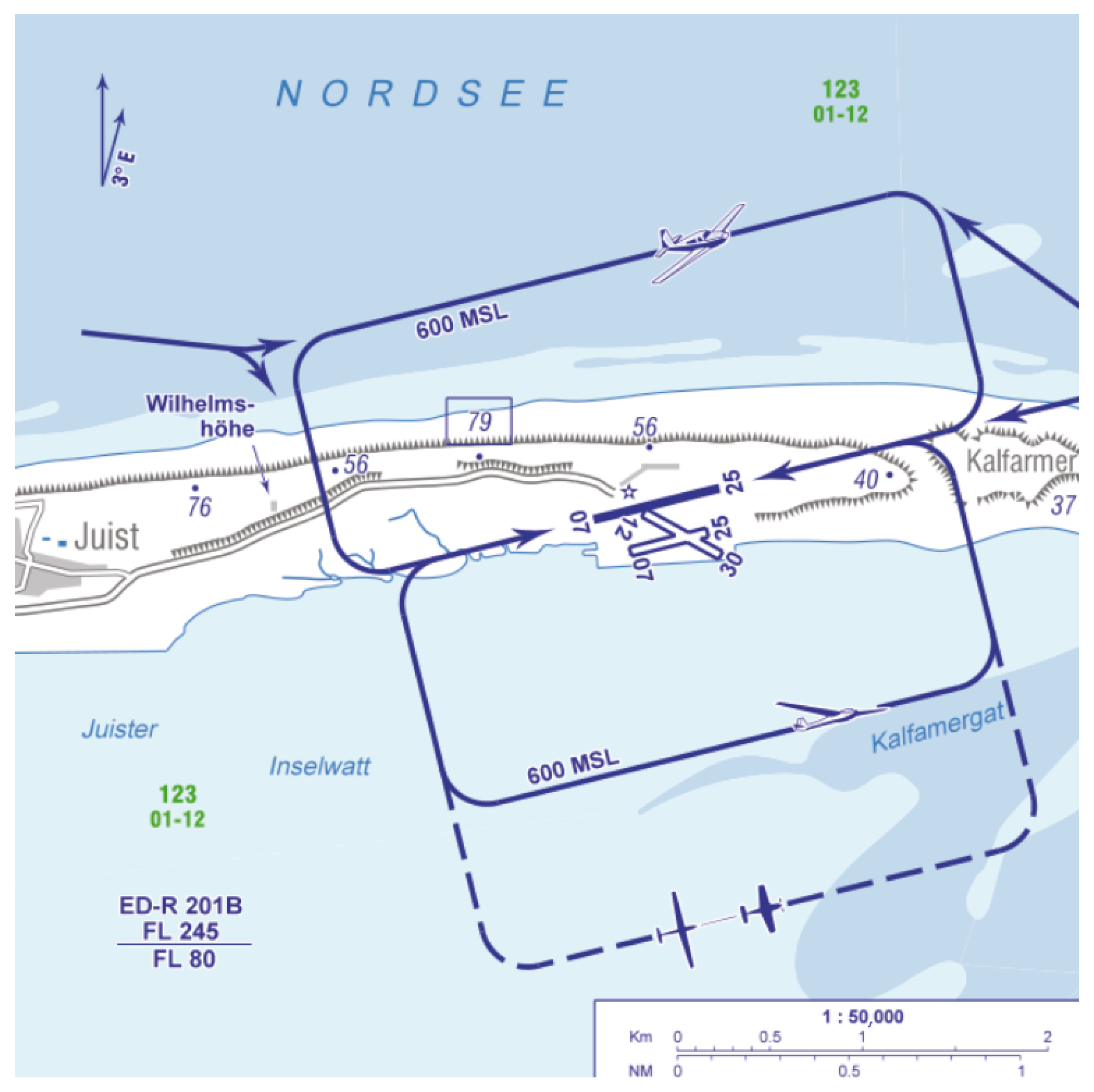

- DFS Deutsche Flugsicherung. Sichtflugkarte/Visual Operating Chart Juist EDWJ. Available online: https://aip.dfs.de/BasicVFR/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Holmes, B.J.; Durham, M.H.; Tarry, S.E. Small aircraft transportation system concept and technologies. J. Aircr. 2004, 41, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viken, S.A.; Brooks, F.M.; Johnson, S.C. Overview of the small aircraft transportation system project four enabling operating capabilities. J. Aircr. 2006, 43, 1602–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, C.A. Hybrid verification of an air traffic operational concept. In Proceedings of the IEEE/NASA Workshop on Leveraging Applications of Formal Methods, Verification, and Validation, Columbia, MD, USA, 23–24 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Consiglio, M.; Williams, D.; Murdoch, J.; Adams, C. SATS HVO concept validation experiment. In Proceedings of the AIAA 5th ATIO and 16th Lighter-Than-Air Systems Technology and Balloon Systems Conferences, Arlington, VA, USA, 26–28 September 2005; p. 7314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (NRC) and Transportation Research Board and Committee. Future Flight: A Review of the Small Aircraft Transportation System Concept. Available online: https://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/sr/sr263.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Geister, D.; Geister, R. Integrating unmanned aircraft efficiently into hub airport approach procedures. J. Navig. 2013, 60, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, E.; Prats, X.; Royo, P.; Delgado, L.; Santamaria, E. UAS pilot support for departure, approach and airfield operations. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 6–13 March 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboubi, Z.; Kochenderfer, M.J. Autonomous Air Traffic Control for Non-Towered Airports. In Proceedings of the 11th USA/Europe Air Traffic Management Research and Development Seminar (ATM2015), Lisbon, Portugal, 23–26 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schwoch, G.; Geister, R.; Geister, D.; Sangermano, V.; Löhr, F.; Fas-Millán, M.; Gómez, M.; Sunil, E.; Reuber, E.; Rocchio, R.; et al. INVIRCAT Final ConOps ’RPAS in the TMA’; Final Report; SESAR Joint Undertaking: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Schwoch, G.; Duca, G.; Ferraiuolo, V.; Filippone, E.; Lanzi, P.; Petersen, C.; Rocchio, R.; Sangermano, V.; Teutsch, J. Preliminary validation results of a novel concept of operations for RPAS integration in TMA and at airports. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, E.; Royo, P.; Delgado, L.; Perez, M.; Barrado, C.; Prats, X. Depart and approach procedures for UAS in a VFR environment. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Applications and Theory of Automation in Command and Control Systems (ATACCS), Barcelona, Spain, 26–27 May 2011; pp. 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Non-Towered Airport Flight Operations. 2023. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/documentlibrary/media/advisory_circular/ac_90-66c.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Garmin. Autonomi. Available online: https://discover.garmin.com/en-US/autonomi/#esp (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- AIN. FAA Accepts Technical Requirements for Reliable Robotics’ Navigation and Autopilot Systems. Available online: https://reliable.co/news (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Rorie, R.C.; Smith, C.L. Detect and Avoid and Collision Avoidance Flight Test Results with ACAS Xr. In Proceedings of the 43rd Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), San Diego, CA, USA, 29–3 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RTCA, Inc. DO-365B—Minimum Operational Performance Standards (MOPS) for Detect and Avoid (DAA) Systems, Minimum Performance Standards for Unmanned Aircraft System; RTCA, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/664 of 22 April 2021 on a Regulatory Framework for the U-Space; Implementing Regulation; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). AMC1 SERA.6005(c) Requirements for Communications, SSR Transponder and Electronic Conspicuity in U-Space Airspace; EASA: Cologne, Germany, 2023.

- German Aerospace Center (DLR). AREA U-Space (Air Space Research Area U-Space). Available online: https://www.dlr.de/en/uc/research-and-transfer/projects-and-missions/area-u-space (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- RTCA, Inc. DO-400 Guidance Material: Standardized Lost C2 Link Procedures for Uncrewed Aircraft Systems; RTCA, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sievers, T.F.; Geister, D.; Schwoch, G.; Peinecke, N.; Schuchardt, B.I.; Volkert, A.; Lieb, J. DLR Blueprint–Initial ConOps of U-Space Flight Rules (UFR). 2024; Blueprint; DLR Institute of Flight Guidance: Braunschweig, Germany, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wing, D.; Lacher, A.; Ryan, W.; Cotton, W.; Stilwell, R.; John, M.; Vajda, P. Digital Flight: A New Cooperative Operating Mode to Complement VFR and IFR; Technical Memorandum (TM); NASA Langley Research Center: Hampton, VA, USA, 2022.

- Clothier, R.A.; Williams, B.P.; Fulton, N.L. Structuring the safety Case for unmanned aircraft system operations in non-segregated airspace. Saf. Sci. 2015, 79, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICAO. ICAO Doc 8186: Aircraft Operations—Volume II Construction of Visual & Instrument Flight Procedures, 16th ed.; ICAO: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, D.; Budd, L.; Ison, S.; Kitching, G. The environmental effects of peak hour air traffic congestion: The case of London Heathrow Airport. In Proceedings of the Research in Transportation Economics, Warsaw, Poland, 18–21 April 2016; Volume 55, pp. 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUROCONTROL. Eurocontrol Manual for Airspace Planning; Eurocontrol: Brussels, Belgium, 2003; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- EUROCONTROL. European Route Network Improvement Plan—Part 1: European Airspace Design Methodology-Guidelines; Eurocontrol: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- SESAR Joint Undertaking. U-space ConOps and Architecture (Edition 4); SESAR Joint Undertaking: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- International Civil Aviation Organization. Annex 2 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation: Rules of the Air, 10th ed.; ICAO: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). 13-01-262: Airport Facility Directory (AFD) Depiction of Traffic Pattern Altitudes. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/flight_info/aeronav/acf/media/Presentations/16-02-RD262_TPAs_Proposed_AIM_guidance_Boll.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Merlin Labs. Merlin-Home. Available online: https://merlinlabs.com/ (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Reliable Robotics Corporation. Reliable Robotics-Company. Available online: https://reliable.co/company (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Flightradar24. Flightradar24: Live Flight Tracker—Real-Time Flight Tracker Map. Available online: https://www.flightradar24.com/ (accessed on 21 June 2023).

- NASA. Sherlock Data Warehouse. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/ames/aviationsystems/sherlock-data-warehouse/ (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Horváth Second Workshop: Interoperability of E-Conspicuity Systems for GA. Available online: https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/downloads/139413/en (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Dahle, O.H.; Rydberg, J.; Dullweber, M.; Peinecke, N.; Bechina, A.A.A. A proposal for a common metric for drone traffic density. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Dubrovnik, Croatia, 21–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Federal Aviation Administration. United States Government Flight Information Publication. Chart Supplement Southwest U.S. 12 JUN 2025; FAA: Washington, DC, USA, 2025.

- National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). § 91.159 VFR Cruising Altitude or Flight Level. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/chapter-I/subchapter-F/part-91/subpart-B/subject-group-ECFR4d5279ba676bedc/section-91.159 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

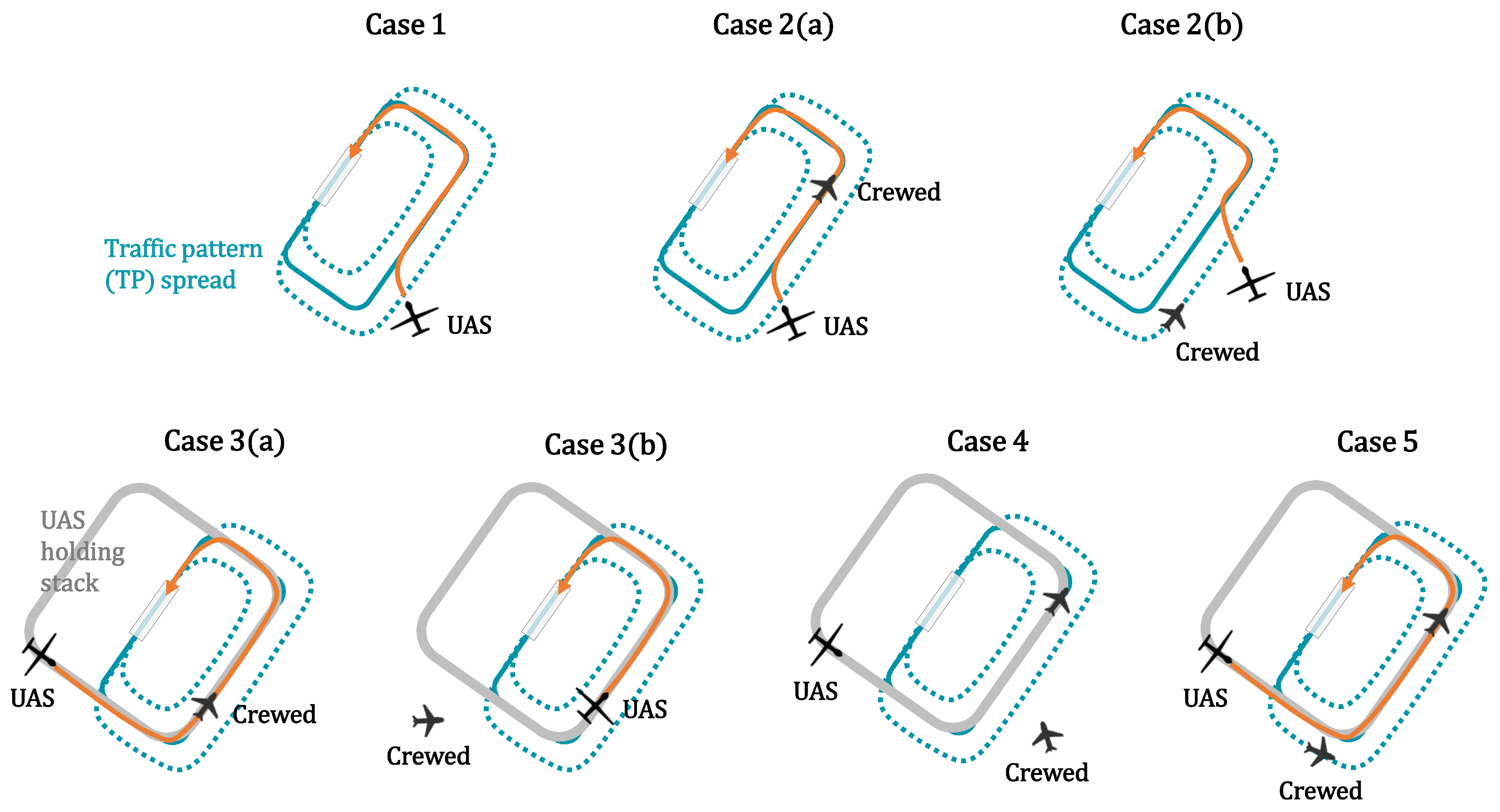

| Scenario | C2 Link | Traffic in Terminal Airspace | Anticipated UAS Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nominal | None | Execute IAP or “visual-like” approach |

| 2 | Nominal | Minimal | Execute “visual-like” approach |

| 3 | Nominal | Saturated | Execute holding maneuver |

| 4 | Lost | None | Execute IAP |

| 5 | Lost | Any | Execute holding maneuver |

| EDWJ | EDWY | EDFE | EDAZ | KWVI | KOAR | KVIS | 0Q4 | KAXH | KLVJ | KLNC | KINJ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (in or ) | [flights] | 7117 | 3495 | 15,719 | 6969 | 21,047 | 8783 | 25,273 | 4475 | 22,464 | 19,113 | 19,661 | 7287 |

| 84.3 | 70.9 | 99.8 | 92.0 | 88.4 | 64.5 | 91.8 | 43.0 | 48.4 | 83.3 | 67.0 | 79.0 | ||

| 32.0 | 37.3 | 0.5 | 26.0 | 63.2 | 62.4 | 58.2 | 62.1 | 62.2 | 31.1 | 51.9 | 48.9 | ||

| (in and ) | [%] | 17.3 | 10.4 | 0.5 | 20.0 | 51.6 | 26.9 | 50.0 | 5.2 | 10.6 | 14.4 | 18.9 | 27.8 |

| (only in ) | 67.6 | 62.3 | 99.4 | 73.8 | 36.8 | 37.6 | 41.8 | 37.8 | 37.8 | 68.9 | 48.1 | 51.2 | |

| (only in ) | 15.1 | 27.3 | 0.1 | 6.2 | 11.6 | 35.5 | 8.2 | 57.0 | 51.6 | 16.7 | 33.0 | 21.0 |

| EDWJ | EDWY | EDFE | EDAZ | KWVI | KOAR | KVIS | 0Q4 | KAXH | KLVJ | KLNC | KINJ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| : | Volume of | [km3] | 45.4 | 18.7 | 32.2 | 41.7 | 70.9 | 46.9 | 100.0 | 22.7 | 50.4 | 42.7 | 29.5 | 44.3 |

| : | per | 156.7 | 187.3 | 487.4 | 167.1 | 296.9 | 187.4 | 252.6 | 197.2 | 445.9 | 447.9 | 665.4 | 164.6 | |

| : | per | 264.3 | 265.7 | 972.6 | 307.6 | 524.9 | 241.8 | 463.7 | 169.7 | 431.7 | 746.5 | 891.2 | 259.9 | |

| : | per | 100.4 | 139.9 | 5.1 | 86.7 | 375.3 | 233.9 | 294.2 | 245.2 | 554.8 | 278.2 | 690.8 | 160.8 | |

| : | per | 25.9 | 16.1 | 2.3 | 30.2 | 153.2 | 50.5 | 126.4 | 10.2 | 47.3 | 64.5 | 125.7 | 45.8 | |

| : | per | 212.5 | 233.6 | 969.2 | 247.2 | 218.5 | 140.9 | 211.0 | 149.3 | 337.0 | 617.6 | 639.9 | 168.4 | |

| : | per | 48.6 | 107.7 | 1.0 | 26.4 | 69.0 | 133.0 | 41.5 | 224.8 | 460.1 | 149.3 | 439.5 | 69.2 | |

- 1 and are half the volume of .

- Note to the table: The color gradient is an indicator for the feasibility of UAS integration, with dark green being the most feasible and white being the least feasible airport; the gray color gradient has no implication. Each row is scaled according to the values in that row.

| EDWJ | EDWY | EDFE | EDAZ | KWVI | KOAR | KVIS | 0Q4 | KAXH | KLVJ | KLNC | KINJ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall norm. flight h | 42.2 | 11.1 | 128.3 | 15.4 | 60.1 | 23.3 | 30.6 | 11.0 | 33.7 | 134.0 | 103.5 | 20.2 | |

| Overall norm. flight km | 1937 | 840 | 6151 | 1296 | 5603 | 2417 | 3090 | 1151 | 3580 | 7317 | 7743 | 2029 | |

| Median flight time | [min] | 2.6 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 3.6 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 3.0 | 1.7 | 2.8 |

| Median norm. flight time | 0.0009 | 0.0013 | 0.0010 | 0.0006 | 0.0008 | 0.0008 | 0.0004 | 0.0009 | 0.0004 | 0.0012 | 0.0009 | 0.0010 | |

| Std. dev. norm. flight time | 0.0114 | 0.0140 | 0.0177 | 0.0059 | 0.0049 | 0.0052 | 0.0024 | 0.0062 | 0.0046 | 0.0133 | 0.0125 | 0.0055 | |

| Median flight dist. | [km] | 6.2 | 3.7 | 4.6 | 5.1 | 11.5 | 8.2 | 7.7 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 7.7 | 4.5 | 8.4 |

| Median norm. flight dist. | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.19 | |

| Std. dev. norm. flight dist. | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.65 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.28 | 0.54 | 0.71 | 0.34 | |

| Median flight speed | [kn] | 78.5 | 85.1 | 76.8 | 102.8 | 103.5 | 121.6 | 99.5 | 122.4 | 124.1 | 82.7 | 87.2 | 97.9 |

| EDWJ | EDWY | EDFE | EDAZ | KWVI | KOAR | KVIS | 0Q4 | KAXH | KLVJ | KLNC | KINJ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| : Volume of | [km3] | 45.4 | 18.7 | 32.2 | 41.7 | 70.9 | 46.9 | 100.0 | 22.7 | 50.4 | 42.7 | 29.5 | 44.3 | |

| : per | 81.3 | 99.3 | 254.8 | 163.5 | 186.4 | 146.9 | 139.2 | 203.9 | 308.9 | 451.7 | 637.1 | 126.6 | ||

| 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.02 | |||

| : per | 264.3 | 265.7 | 972.6 | 307.6 | 524.9 | 241.8 | 463.7 | 169.7 | 431.7 | 746.5 | 891.2 | 259.9 | ||

| 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.05 | |||

| : per | 100.4 | 139.9 | 5.1 | 86.7 | 375.3 | 233.9 | 294.2 | 245.2 | 554.8 | 278.2 | 690.8 | 160.8 | ||

| 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.02 | |||

| : per | 13.6 | 24.3 | 16.0 | 179.1 | 181.1 | 218.6 | 88.1 | 248.9 | 544.5 | 378.8 | 1177.7 | 103.1 | ||

| 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.00 | |||

| : per | 3.9 | 5.1 | 31.5 | 190.6 | 113.3 | 155.8 | 39.9 | 243.7 | 79.2 | 858.8 | 177.9 | 102.9 | ||

| 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

- 1 In this table, annual median densities are based on normalized flight counts over ten airport operating hours from 8:00 AM to 6:00 PM local time. The total annual densities, are based on flight counts over 24 h.

- 2 , , and are a quarter of the volume of and is half the volume of .

- Note to the table: The color gradient is an indicator for the feasibility of UAS integration, with dark green being the most feasible and white being the least feasible airport; the gray color gradient has no implication. Each row is scaled according to the values in that row.

| Juist (EDWJ) | Norderney (EDWY) | Egelsbach (EDFE) | Schoenhagen (EDAZ) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airspace Class | ATC

Separation | ATC

Clearance | |||||

| Class C | IFR to V/IFR | V/IFR | >Class E | >Class E | >Class D | >Class E | |

| Controlled airspace | Class D | IFR to IFR | V/IFR | – | – | Class G to 2500 ft MSL | – |

| Class E | IFR to IFR | IFR | Class G to FL100 | Class G to FL100 | – | Class G to Class C 1 | |

| Uncontrolled airspace | Class G | No | No | Ground to 2500 ft AGL | Ground to 2500 ft AGL | Ground to 1500 ft MSL | Ground to 1000 ft AGL |

| Recommended TPA | 600 ft MSL (592 ft AGL) | 700 ft MSL (694 ft AGL) | 1300 ft MSL (915 ft AGL) | 1000 ft MSL (848 ft AGL) | |||

| Watsonville (KWVI) | Marina (KOAR) | Visalia (KVIS) | Selma (0Q4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airspace Class | ATC Separation | ATC Clearance | |||||

| Class B | V/IFR to V/IFR | V/IFR | – | – | – | – | |

| Class C | IFR to V/IFR | IFR 1 | – | 1500 ft to 4200 ft MSL | – | – | |

| Controlled airspace | Class D | IFR to IFR | IFR 1 | – | – | – | – |

| Class E | IFR to IFR | IFR | Class G to FL180 | Class G to 1500 ft MSL; Class C to FL180 | Ground to FL180 | Class G to FL180 | |

| Uncontrolled airspace | Class G | No | No | Ground to 700 ft AGL | Ground to 700 ft AGL | – | Ground to 1200 ft AGL |

| Recommended TPA | 1163 ft MSL (1000 ft AGL) | 1137 ft MSL (1000 ft AGL) | 1293 ft MSL (1000 ft AGL) | 1105 ft MSL (800 ft AGL) | |||

| Houston SW (KAXH) | Pearland (KLVJ) | Lancaster (KLNC) | Hillsboro (KINJ) | ||||

| Airspace Class | ATC Separation | ATC Clearance | |||||

| Class B | V/IFR to V/IFR | V/IFR | 2500 ft MSL to FL100 | 2000 ft MSL to FL100 | 4000 ft MSL to FL110 | – | |

| Class C | IFR to V/IFR | IFR 1 | – | – | – | – | |

| Controlled airspace | Class D | IFR to IFR | IFR 1 | – | – | – | – |

| Class E | IFR to IFR | IFR | Class G to 2500 ft MSL; Class B to FL180 | Class G to 2000 ft MSL; Class B to FL180 | Class G to 4000 ft MSL; Class B to FL180 | Class G to FL180 | |

| Uncontrolled airspace | Class G | No | No | Ground to 700 ft AGL | Ground to 700 ft AGL | Ground to 700 ft AGL | Ground to 700 ft AGL |

| Recommended TPA | 1070 ft MSL (1000 ft AGL) | 1044 ft MSL (1000 ft AGL) | 1501 ft MSL (1000 ft AGL) | 1686 ft MSL (1000 ft AGL) | |||

| Juist (EDWJ) | Norderney (EDWY) | Egelsbach (EDFE) | Schoenhagen (EDAZ) | Watsonville (KWVI) | Marina (KOAR) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0009 | 0.0013 | 0.0010 | 0.0006 | 0.0006 | 0.0006 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.0114 | 0.0140 | 0.0177 | 0.0059 | 0.0046 | 0.0045 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.14 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.65 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.38 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Annual median densities 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total annual densities | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Potential less busy altitude bands for a holding stack 2 | ft AGL | ft AGL | 2500 ft– 4000 ft AGL | 2500 ft– 3000 ft AGL | No recommendation | No recommendation | |||||||||||||||||||

| Potential number of vertical holding stack layers 3,4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 1 | - | - | |||||||||||||||||||

| Recommended TPA | 600 ft MSL (592 ft AGL) | 700 ft MSL (694 ft AGL) | 1300 ft MSL (915 ft AGL) | 1000 ft MSL (848 ft AGL) | 1163 ft MSL (1000 ft AGL) | 1137 ft MSL (1000 ft AGL) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Vertical distance from lowest holding layer into TPA | ft | ft | ft | ft | - | - | |||||||||||||||||||

| Visalia (KVIS) | Selma (0Q4) | Houston SW (KAXH) | Pearland (KLVJ) | Lancaster (KLNC) | Hillsboro (KINJ) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.0004 | 0.0008 | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | 0.0002 | 0.0007 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.0024 | 0.0049 | 0.0039 | 0.0102 | 0.0094 | 0.0047 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.14 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.16 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.41 | 0.54 | 0.28 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Annual median densities 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total annual densities | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Potential less busy altitude bands for a holding stack 2 | ft AGL | No recommendation | 5500 ft– 6000 ft AGL | No recommendation | No recommendation | ft AGL | |||||||||||||||||||

| Potential number of vertical holding stack layers 3,4 | 2–3 | - | 1 | - | - | 2–3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Recommended TPA | 1293 ft MSL (1000 ft AGL) | 1105 ft MSL (800 ft AGL) | 1070 ft MSL (1000 ft AGL) | 1044 ft MSL (1000 ft AGL) | 1501 ft MSL (1000 ft AGL) | 1686 ft MSL (1000 ft AGL) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Vertical distance from lowest holding layer into TPA | ft | - | ft | - | - | ft | |||||||||||||||||||

- 1 Annual median of daily medians of hourly density.

- 2 Potential altitude bands for UAS holding stack locations are not based on safety thresholds, whereas “ideal” locations would likely be determined based on numerical values and specific thresholds.

- 3 The upper bound of the UAS holding stack is expected to be limited to 6000 ft (∼1830 m) AGL.

- 4 Depends on the vertical space between individual overflying traffic streams.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sievers, T.F.; Sakakeeny, J.; Idris, H.; Peinecke, N.; Bulusu, V.; Nagel, E.; Jack, D. Conceptual Development of Terminal Airspace Integration Procedures of Large Uncrewed Aircraft Systems at Non-Towered Airports. Drones 2025, 9, 858. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120858

Sievers TF, Sakakeeny J, Idris H, Peinecke N, Bulusu V, Nagel E, Jack D. Conceptual Development of Terminal Airspace Integration Procedures of Large Uncrewed Aircraft Systems at Non-Towered Airports. Drones. 2025; 9(12):858. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120858

Chicago/Turabian StyleSievers, Tim Felix, Jordan Sakakeeny, Husni Idris, Niklas Peinecke, Vishwanath Bulusu, Enno Nagel, and Devin Jack. 2025. "Conceptual Development of Terminal Airspace Integration Procedures of Large Uncrewed Aircraft Systems at Non-Towered Airports" Drones 9, no. 12: 858. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120858

APA StyleSievers, T. F., Sakakeeny, J., Idris, H., Peinecke, N., Bulusu, V., Nagel, E., & Jack, D. (2025). Conceptual Development of Terminal Airspace Integration Procedures of Large Uncrewed Aircraft Systems at Non-Towered Airports. Drones, 9(12), 858. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120858