A Method for UAV Path Planning Based on G-MAPONet Reinforcement Learning

Highlights

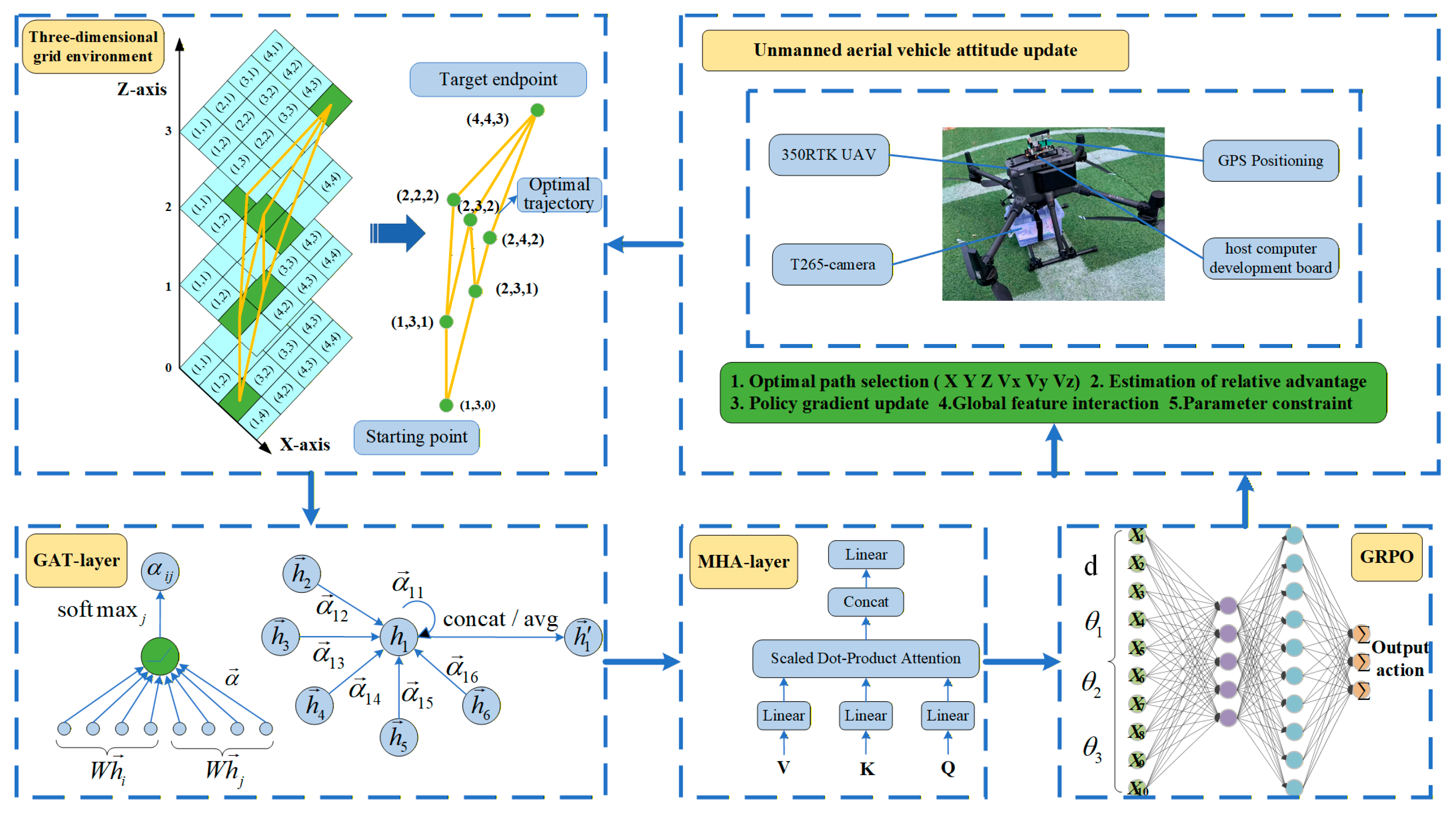

- A hierarchical attention and collaborative framework combining GAT and MHA layers is proposed, which captures dynamic spatiotemporal features and realizes multi-scale path planning, overcoming the limitations of static models and resolving global–local conflicts.

- The GRPO algorithm is applied to optimize UAV path planning strategies, improving convergence speed and policy stability; experiments show that G-MAPONet outperforms traditional and single-attention models in diverse scenarios in terms of convergence, reward, and task completion.

- The proposed framework provides an effective solution for dynamic environmental modeling and multi-scale optimization in UAV path planning, enhancing adaptability to complex environments.

- The integration of hierarchical mechanisms and GRPO offers theoretical and technical references for intelligent trajectory planning in other multi-agent systems or dynamic task scenarios.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Hierarchical attention modeling of dynamic spatiotemporal features: A dual-layer fusion mechanism combining GAT and MHA layers is designed. The dynamic graph model captures time-varying environmental weights, and multi-head computation identifies UAV traversal patterns. Experiments show that this dual-layer mechanism improves convergence efficiency and overcomes the limits of static models.

- (2)

- Hierarchical collaborative mechanism for multi-scale path planning: The framework uses high-level MHA for global guidance and low-level GAT for local optimization. The high-level module generates a trajectory based on terrain trends, while the low-level module enables real-time obstacle avoidance. This design resolves the global–local conflict in single-scale planning.

- (3)

- Objective and constraint modeling: A composite objective function integrates timeliness compliance and energy efficiency. A multi-constraint model includes flight altitude, payload, speed, and delivery time.

- (4)

- Efficient strategy optimization under GRPO: The GRPO algorithm is applied to UAV path planning. By adjusting the trust region to regulate step size, it improves convergence speed and policy stability.

- (5)

- Robustness and generalization across scenarios: Experiments in diverse environments show that G-MAPONet outperforms traditional and single-attention models in convergence, reward, and task completion.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Related Research Content

2.2. G-MAPONet Fusion Algorithm Design

2.2.1. G-MAPONet Model Framework

2.2.2. Model Pseudocode

| Algorithm 1: G-MAPONet |

| Input: Initialize parameters Number of Steps T; State Space Dimension ; Action Space Dimension ; Number of GAT Heads ; Hidden Layer Dimension ; Episode E Output: The Optimized G-MAPONet Model 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 |

2.2.3. Algorithm Inference Process

2.3. GAT Layer Attention Mechanism

| Algorithm 2: GAT |

| Input: Initialize parameters ; Episode E, Grid environment G Output: Optimized GAT model parameter 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 |

2.4. MHA Layer Attention Mechanism

| Algorithm 3: MHA |

| Input: Initialize parameters Output: Attention-Enhanced Sequence Z 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

3. Experiment and Results

3.1. Distribution Route Planning and Design

3.1.1. Objective Function Design

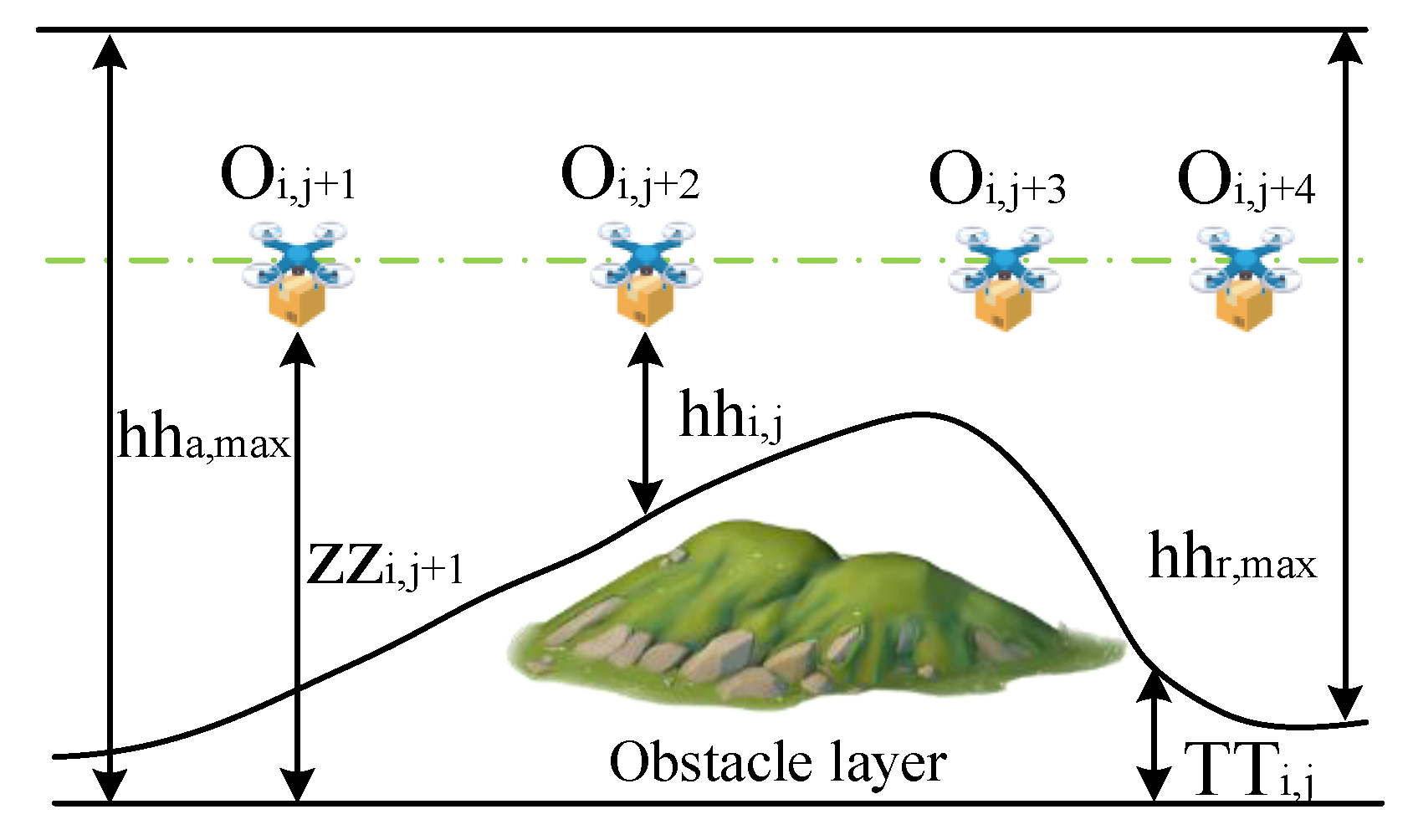

3.1.2. Flight Environment Constraints

Flight Altitude Constraint

UAV Payload Constraint

Speed Constraint

Time Constraint

3.2. Experimental Scenarios

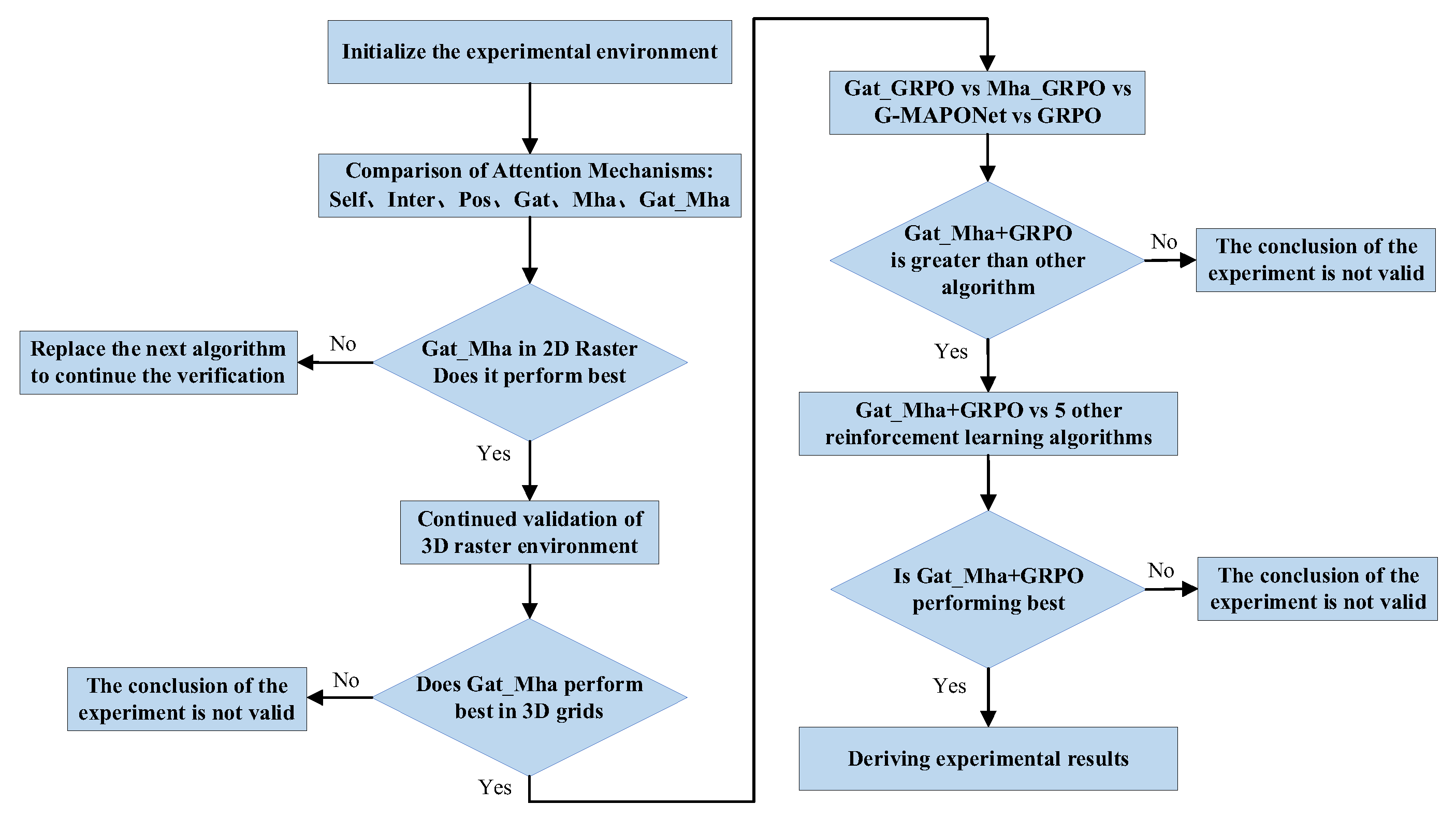

3.2.1. Experimental Procedure

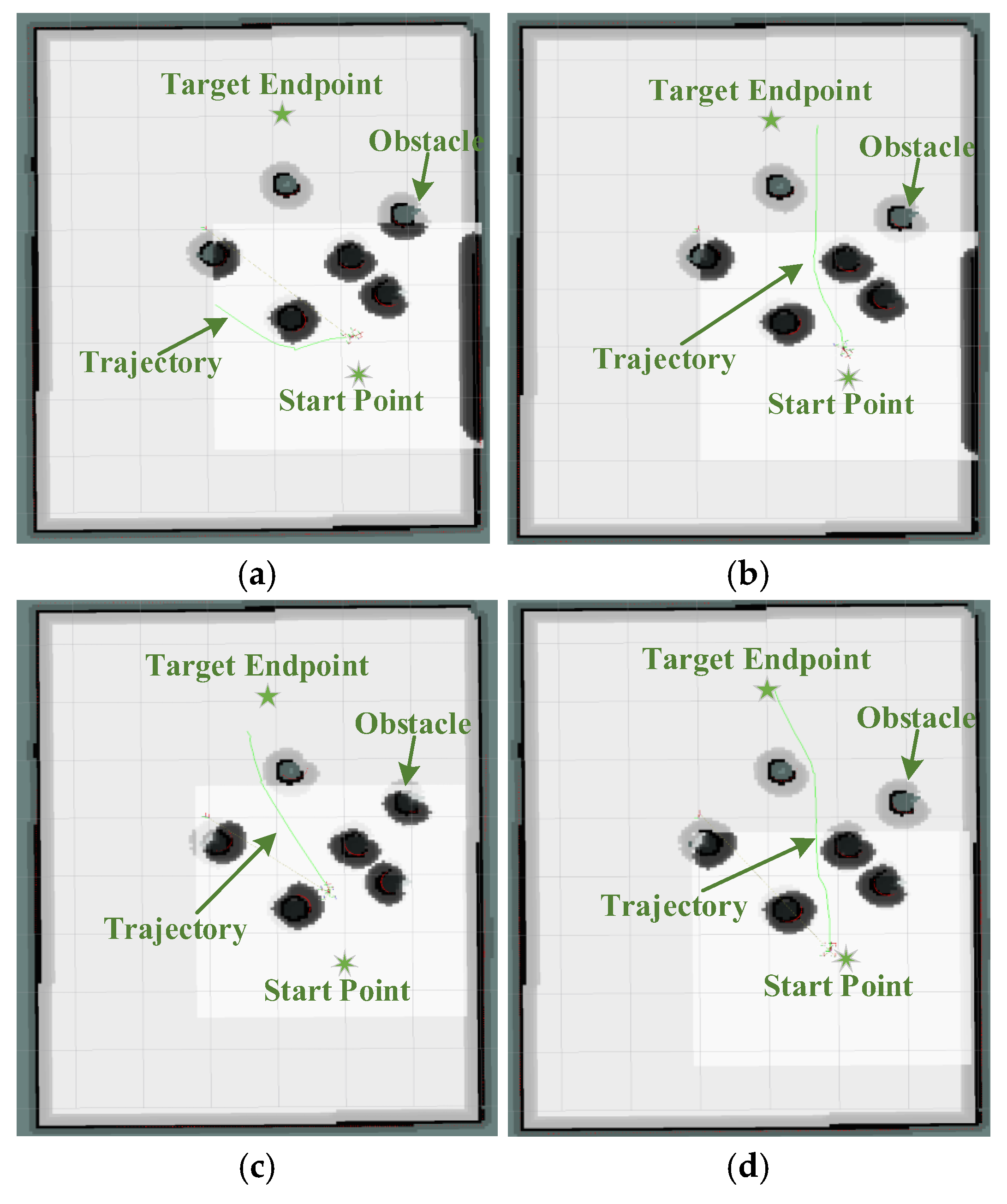

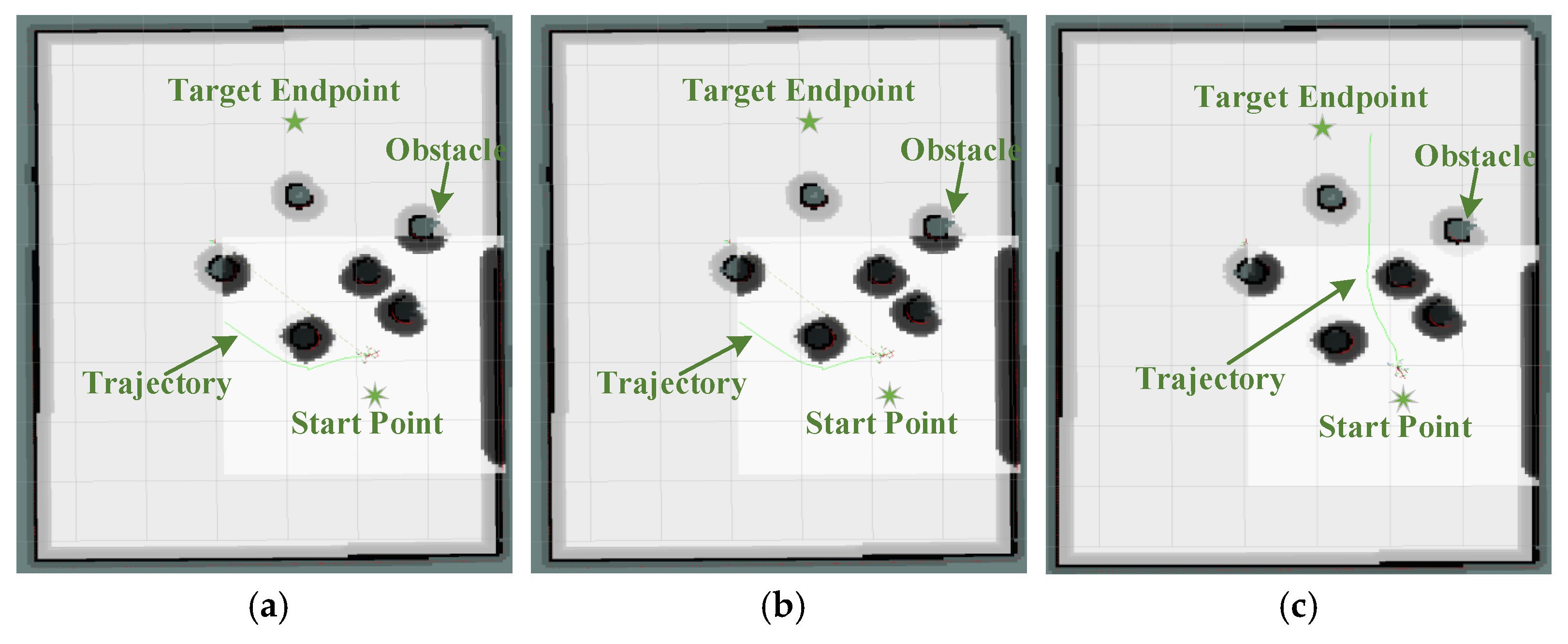

- Experiment 1 assesses both the objective function and constraint conditions of UAV delivery. The flight environment is constructed as a 7 × 7 two-dimensional obstacle map composed of a 7 × 7 grid of cells (each cell representing 100 m), using Matplotlib-3.7 within the PyCharm simulation environment. Several attention mechanisms—Self, Inter, Pos, Gat, Mha, and Gat_Mha—are implemented and compared.

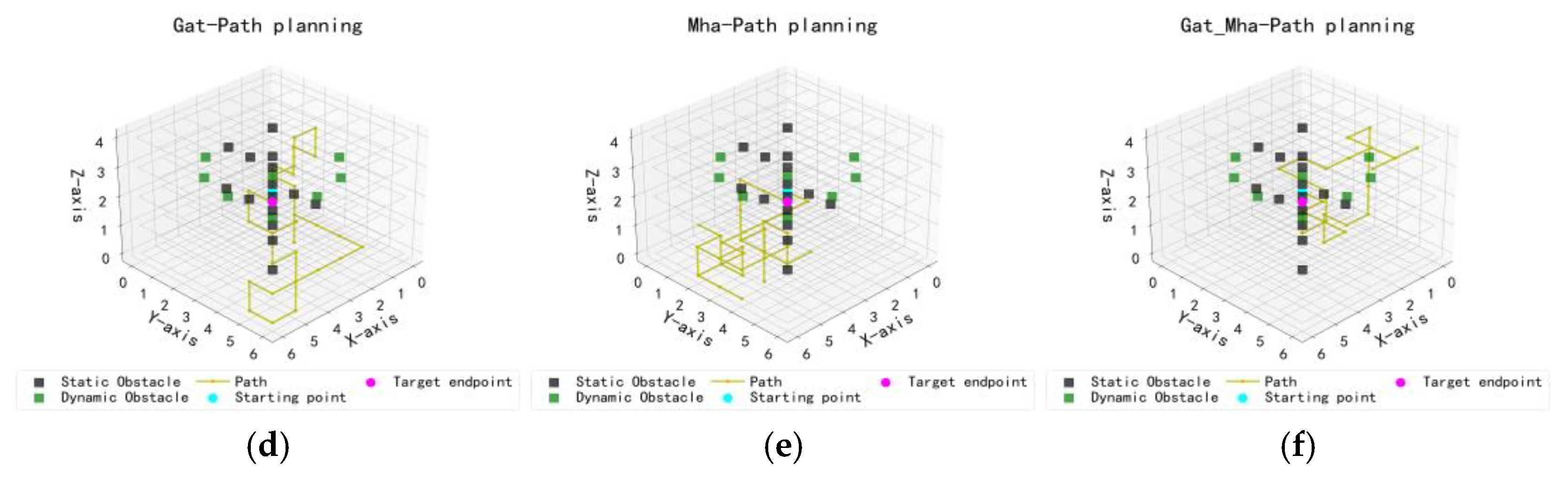

- Experiment 2 extends the environment to a 6 × 6 × 4 three-dimensional grid (each cell representing 100 m) to evaluate the robustness and generalizability of the results from Experiment 1. The same set of attention mechanisms is tested under this more complex spatial configuration to examine performance in higher-dimensional settings.

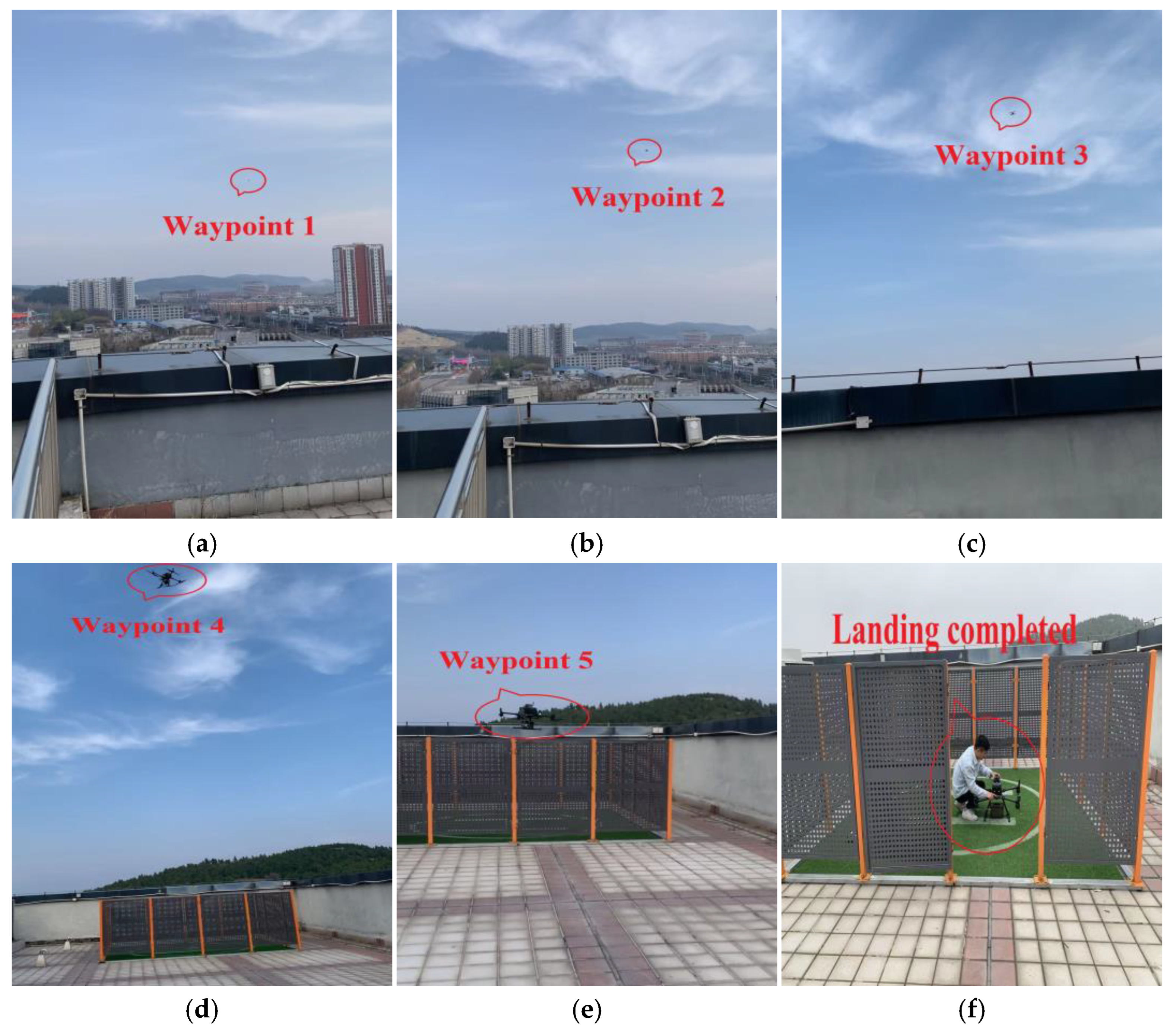

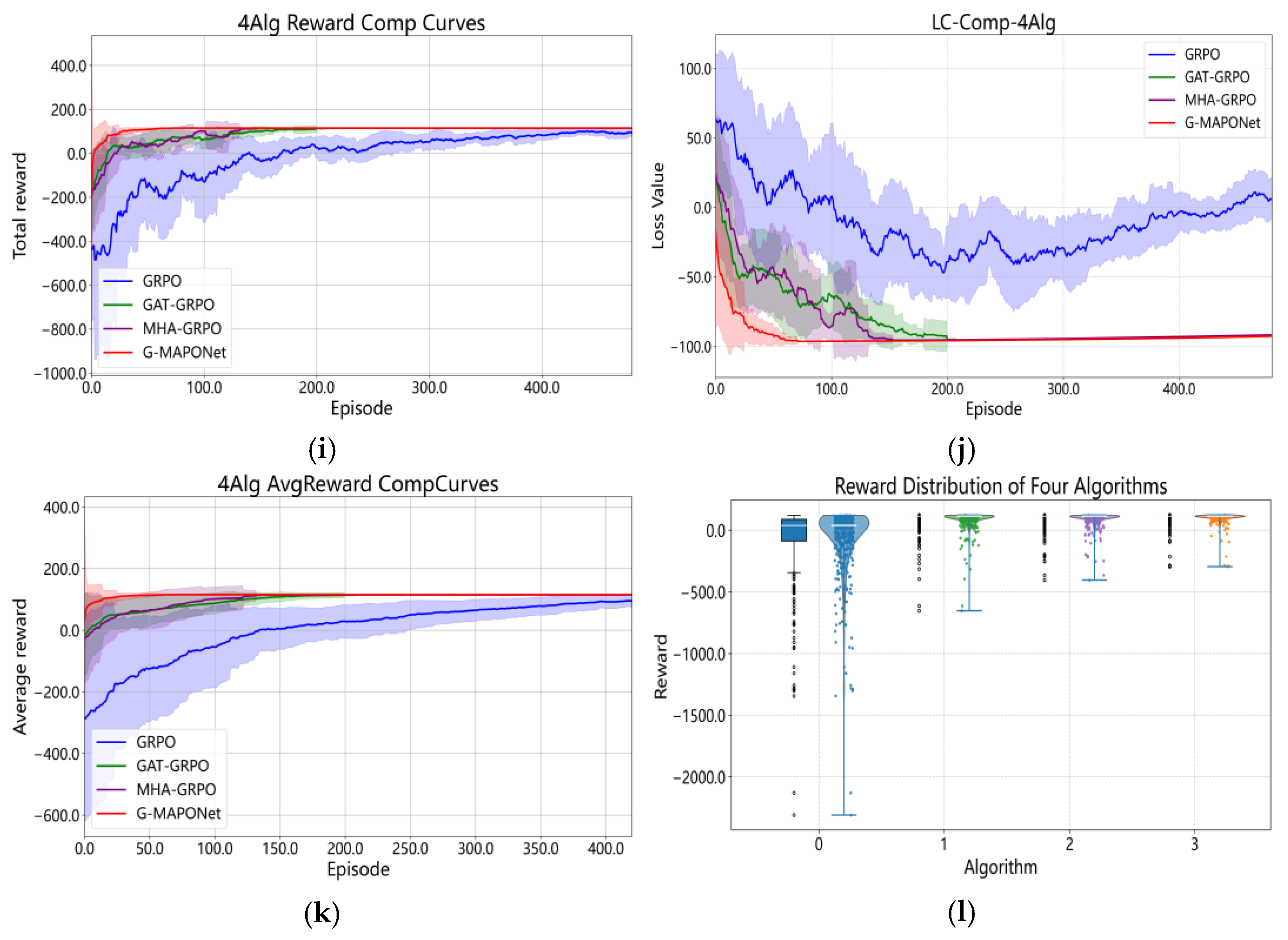

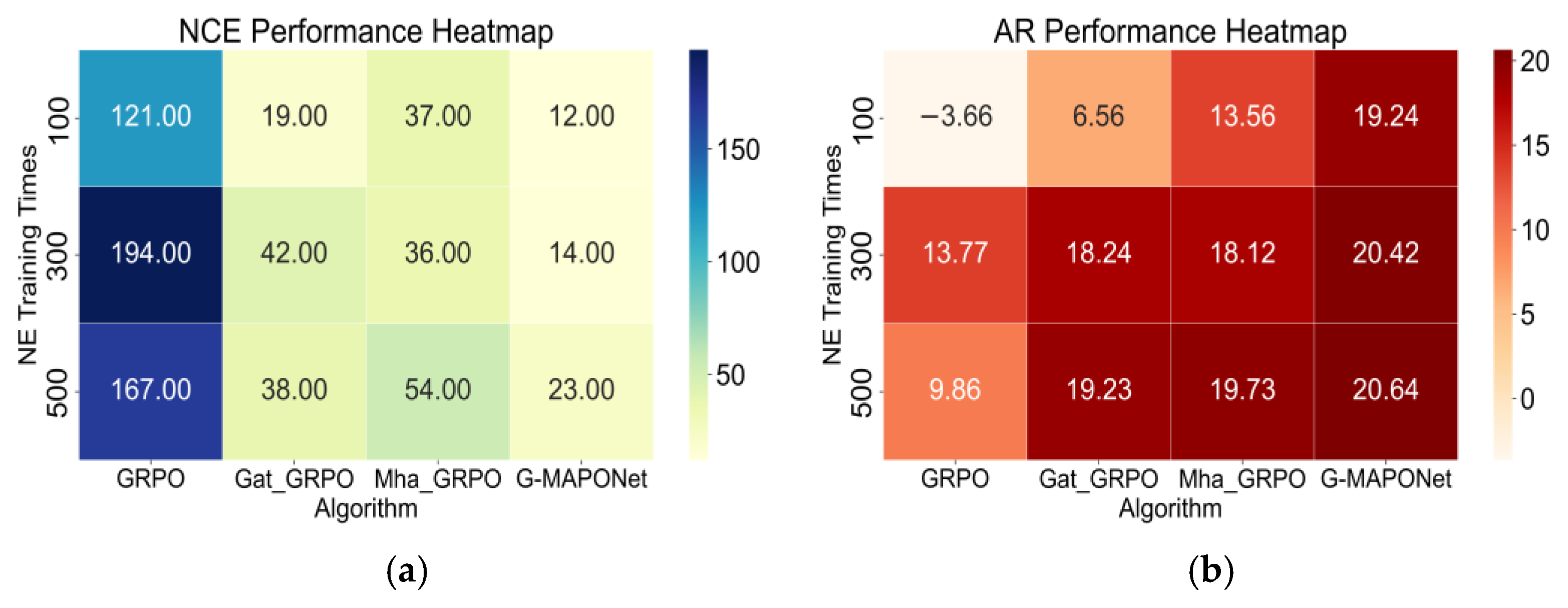

- Experiment 3 conducts real-world flight validation based on the findings from the first two simulation experiments. A 1000 m × 1000 m × 120 m three-dimensional environment is employed, incorporating both the path planning and delivery constraints of UAV logistics. Four configurations are evaluated: the single-layer GRPO algorithm, the dual-layer GRPO-GAT architecture, the dual-layer GRPO-MHA architecture, and the three-layer G-MAPONet architecture.

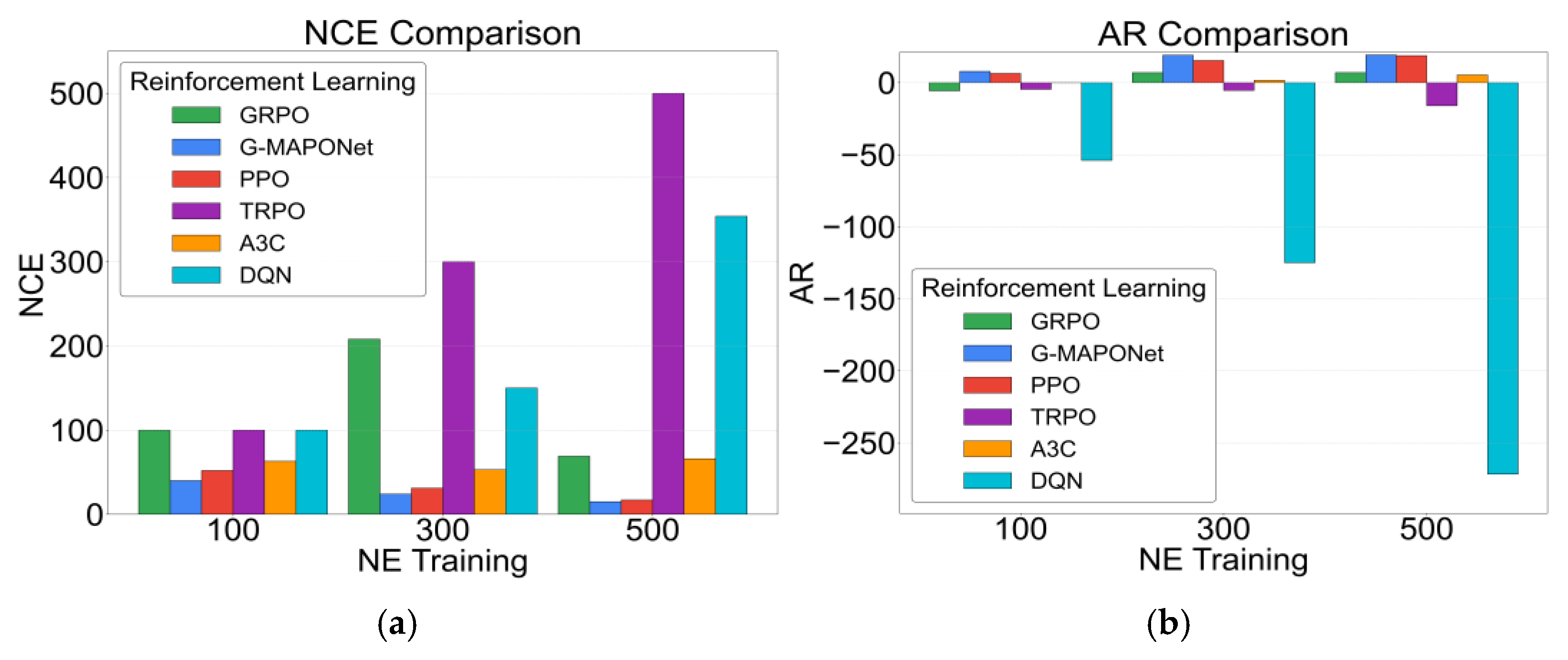

- Experiment 4 evaluates the timeliness and responsiveness of the three-layer G-MAPONet architecture in real-world delivery scenarios. It compares G-MAPONet with other reinforcement learning algorithms—GRPO, PPO, TRPO, A3C, and DQN—under identical experimental conditions.

3.2.2. Simulation Environment

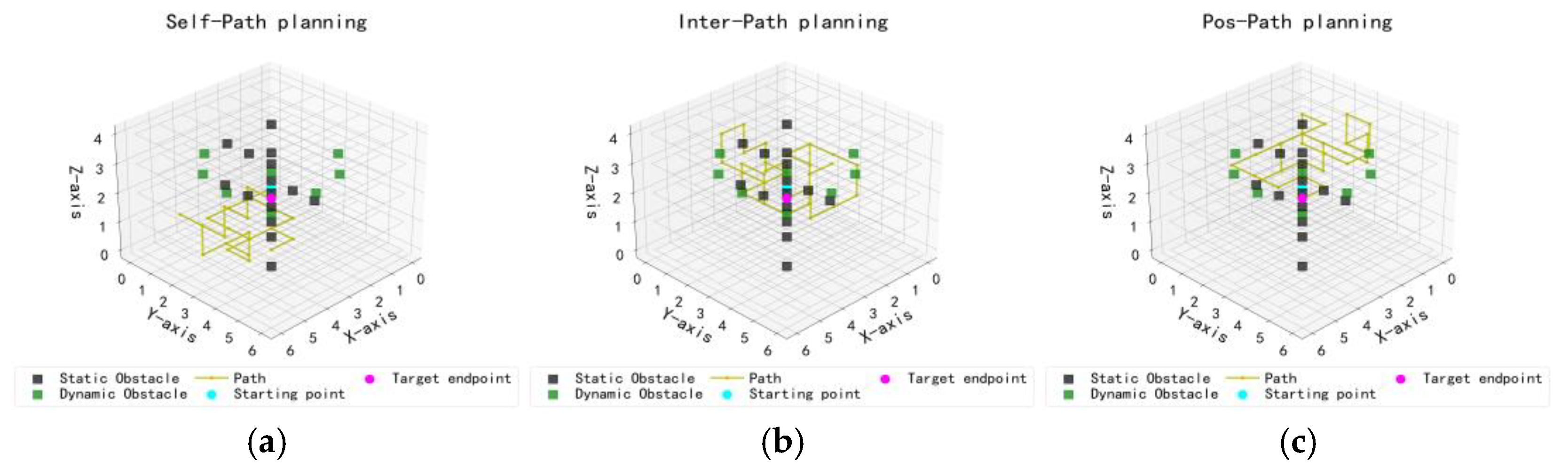

Experiments on Different Attention Mechanisms in 2D Environments

Experiments on Different Attention Mechanisms in 3D Environments

3.2.3. Real Flight Environment

Ablation Study of the G-MAPONet Algorithm

Experiments on Different RL Algorithms

3.3. Comparison Results of Different Attention Mechanisms

3.3.1. Experiments on Different Attention Mechanisms in 2D Training Environments

3.3.2. Experiments on Different Attention Mechanisms in 3D Training

3.4. Comparison Results of Different Reinforcement Learning Algorithms

3.4.1. Ablation Study of the G-MAPONet Algorithm in Training

3.4.2. Experiments on Different RL Algorithms in Training

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Experimental Data in Reinforcement Learning

4.1.1. Discussion on the Ablation Study of the G-MAPONet Algorithm

4.1.2. Discussion on the Results of Different RL Algorithms

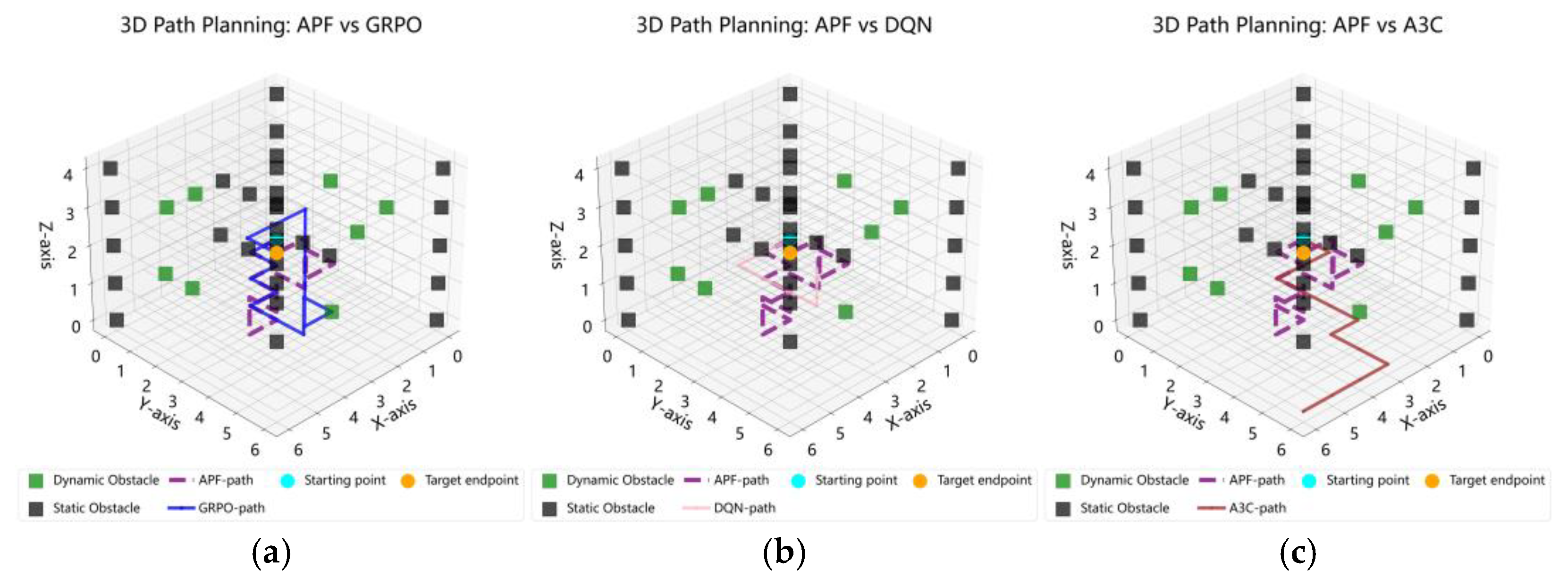

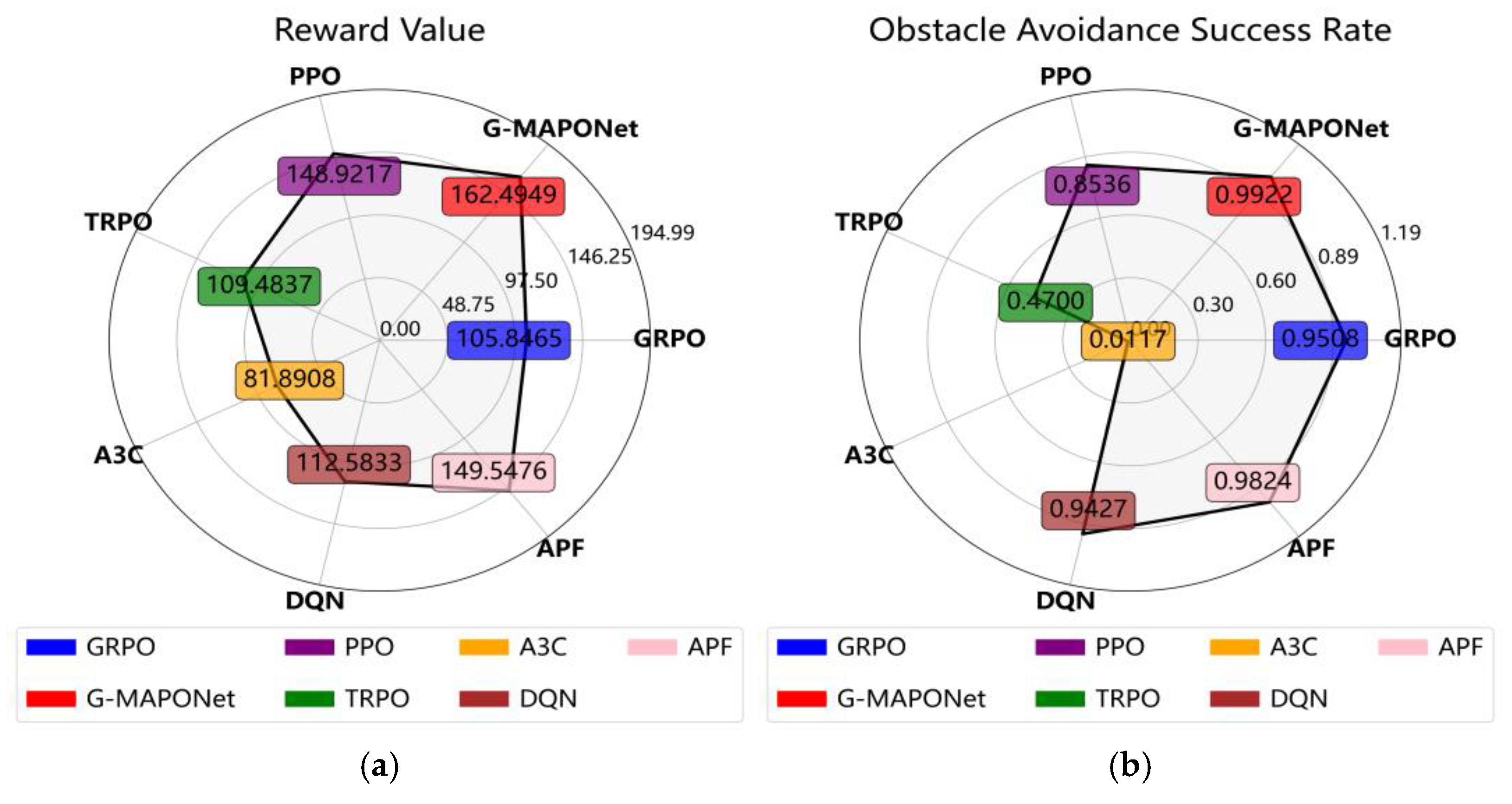

4.2. Comparison of RL Algorithms Under the APF Benchmark Function

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Compared with Self, Inter, Pos, Gat, and Mha attention mechanisms, the fused Gat_Mha mechanism shows superior performance in On-Time Completion Rate and Total Training Convergence Time. Moreover, the Path Planning Task Completion Status is fully achieved, indicating enhanced capabilities in environmental feature modeling and path planning.

- (2)

- When comparing GRPO with the improved Gat_GRPO, Mha_GRPO, and G-MAPONet algorithms, the results show that G-MAPONet achieves the highest performance. Specifically, in terms of NCE, the convergence mean of Gat_GRPO improves by 79.96% over GPRO, Mha_GRPO by 72.84%, and G-MAPONet by 89.70%. In Average Reward (AR), the improved algorithms consistently outperform GPRO across all three training rounds. These results confirm that G-MAPONet offers the best convergence speed and robustness.

- (3)

- Further validation with GRPO, PPO, TRPO, A3C, and DQN reinforcement learning algorithms demonstrates that G-MAPONet significantly reduces the Number of Convergence Epochs (NCE). At NE = 100, 300, and 500, convergence rounds are reduced by 23.08%, 22.58%, and 11.76%, respectively, with an average reduction of 19.14%. In AR performance, G-MAPONet outperforms PPO—the best among the five—by 21.86%, 24.24%, and 2.50% at the same NE values, resulting in an overall improvement of 16.20%. Regarding PPTC, G-MAPONet successfully completes dynamic planning at all NE values, demonstrating excellent stability and generalization. In contrast, PPO, GRPO, and A3C succeed only at NE = 300 and 500, while DQN and TRPO fail in all sessions, highlighting limitations in adaptability and state decoupling.

- (4)

- Finally, the APF heuristic algorithm is added as a baseline. After 500 iterations, the results indicate that the reward values and obstacle avoidance success rate of G-MAPONet are significantly higher than those of other algorithms. Compared with the baseline APF, the reward values are improved by 8.66%, and the obstacle avoidance repetition rate is also enhanced. This further verifies the effectiveness of the improved G-MAPONet algorithm.

- (1)

- Optimizing the algorithm architecture by refining feature modeling and exploring dynamic adaptive fusion strategies between GAT and MHA layers to enhance adaptability to complex environments.

- (2)

- Extending algorithm robustness to unstructured environments with dynamic obstacles.

- (3)

- Developing multi-UAV cooperative planning to improve task allocation and coordination among agents, enhancing group efficiency and safety.

- (4)

- Investigating the theoretical foundation of the GAT-MHA attention mechanism in diverse application scenarios to provide stronger theoretical support for strategy optimization.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| G-MAPONet | Graph Multi-Head Attention Policy Optimization Network |

| PPTC | Path Planning Task Completion Status |

| NCE | Number of Convergence Episodes |

| PPL | Path Planning Length |

| NE | Episode |

| AR | Average Reward |

| GRPO | Group Relative Policy Optimization |

| CVRP | Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| C-SPPO | Centralized-S Proximal Policy Optimization |

| MARL | Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| RRT* | Rapidly Exploring Random Tree Star |

| SARSA | State-Action-Reward-State-Action |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| DQN | Deep Q-Network |

| ACO-DQN-TP | Ant Colony Optimization–Deep Q-Network–Time Parameter |

| PO-WMFDDPG | Partially Observable Weighted Mean Field Reinforcement Learning |

| GAT-RL | Graph Attention Networks–Reinforcement Learning |

| MTCR | Maximum timeliness compliance rate |

| MEC | Minimum energy consumption |

| FRV | Final Reward Value |

| OASR | Obstacle Avoidance Success Rate |

Appendix A

| Parameter | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Attention head weight matrix | |

| Attention score parameter vector | |

| The attention parameter vector of the m-th GAT attention head | |

| Dimension of the hidden layer | |

| Dimension of input features | |

| Total number of attention heads | |

| Number of attention heads | |

| Weight matrix of the m-th attention head in the GAT model | |

| Constant | |

| Initial feature matrix input to GAT | |

| Node | |

| Feature matrix transformed by the m attention head of GAT | |

| In the m-th attention head of GAT, the feature vector of node i after feature transformation | |

| In the m-th attention head of GAT, the feature vector of node j after feature transformation | |

| Attention score between node i and node j under the m-th attention head | |

| The unnormalized attention score between node i and domain node | |

| Normalized attention weight of node i for neighbor node j under the m-th attention head | |

| The new feature representation of node i under the m-th attention head, obtained after weighted aggregation of neighbor features | |

| Number of attention heads in GAT | |

| The final node feature matrix output by the GAT model | |

| Input value of nonlinear feature | |

| Input of the current batch of data | |

| Target value | |

| Regularization coefficient | |

| Loss value of the total batches | |

| Loss values of the current batch data | |

| The set of all parameters learned by the model | |

| Number of heads in the multi-head attention mechanism | |

| Feature dimension of the model | |

| Input feature matrix for each batch | |

| Query matrix | |

| Key matrix | |

| Value matrix | |

| Calculate the dot product of the query matrix and the key matrix | |

| Matrix after multi-head attention concatenation | |

| Model final output feature matrix | |

| Learning rate | |

| Query weight matrix | |

| Key weight matrix | |

| Value weight matrix | |

| Output weight matrix | |

| Noise figure | |

| UAV performs an action at time t | |

| After performing action at time t, the immediate reward obtained by the drone from the environment | |

| Fusing information from different subspaces into the output of multi-head attention | |

| leads to the environment transitioning to the next state | |

| Standard Gaussian distribution | |

| value estimate | |

| Boolean value indicating whether the cyclic task has ended | |

| Termination flag | |

| Measuring the advantage of taking a certain action at time t relative to the average policy | |

| Generalized advantage estimation parameter, with a range of values between (0,1), used to dynamically balance the bias and variance fluctuation range | |

| Advantage function | |

| Mean of A | |

| Standard deviation of A | |

| Updated policy | |

| Importance sampling ratio | |

| State representation in a batch of data | |

| , the action actually executed | |

| Advantage values corresponding to batch data | |

| Objective function of the policy’s expected return | |

| Expectation | |

| Discount factor | |

| Gradient vector | |

| Old policy | |

| New policy | |

| Preset trust region value | |

| Step size backoff coefficient | |

| Immediate reward of the batch data | |

| Target value of the value network for the batch | |

| Next state | |

| Value estimation of the next state by the value network | |

| Termination flag of the batch data | |

| Value network | |

| Batch size | |

| Loss function of the value network | |

| Parameters of the value network | |

| with Respect to Value Network Parameters | |

| Parameters of the old policy network | |

| Logistics distribution center | |

| The k-th node in the delivery path of the i-th UAV | |

| The load of the i-th UAV at the k-th node | |

| of the i-th UAV | |

| Energy consumption coefficient per unit load distance | |

| UAV flight speed | |

| The load at the delivery node j of the i-th UAV | |

| The height of the i-th route flying to the j-th track point relative to sea level | |

| Relative flight altitude | |

| Maximum absolute altitude of flight | |

| Actual flight altitude at the j-th waypoint of the i-th route | |

| Total takeoff weight | |

| Drag coefficient | |

| Maximum limit of total flight thrust | |

| Minimum flying speed | |

| Maximum flight speed | |

| Maximum Flight Time | |

| Height coefficient, range of values (0,1) |

References

- Rascon Enriquez, J.; Castillo-Toledo, B.; Di Gennaro, S.; García-Delgado, L.A. An algorithm for dynamic obstacle avoidance applied to UAVs. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2025, 186, 104907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukkanci, O.; Koberstein, A.; Kara, B.Y. Drones for relief logistics under uncertainty after an earthquake. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 310, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Ng, K.K.H.; Zhang, C.; Chan, Y.Y.; Qin, Y. A multistage stochastic programming approach for drone-supported last-mile humanitarian logistics system planning. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Li, Y.; Qu, G. Integrated dynamic task allocation via event-triggered for tracking ground moving targets by UAVs in urban. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2025, 193, 105061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Liu, W.; Cai, L. Multi-dynamic target coverage tracking control strategy based on multi-UAV collaboration. Control Eng. Pract. 2025, 155, 106170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, T.; Kaśkosz, K. Optimizing drone logistics in complex urban industrial infrastructure. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2025, 140, 104610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Yi, J.; Liu, H. A bi-level planning approach of logistics unmanned aerial vehicle route network. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 141, 108572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualola, H.; Mizouni, R.; Otrok, H.; Singh, S.; Barada, H. A matching game-based crowdsourcing framework for last-mile delivery: Ground-vehicles and Unmanned-Aerial Vehicles. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2023, 213, 103601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshref-Javadi, M.; Hemmati, A.; Winkenbach, M. A truck and drones model for last-mile delivery: A mathematical model and heuristic approach. Appl. Math. Model. 2020, 80, 290–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.; Chai, Q.; Liu, N.; Zheng, W. A multi-objective cat swarm optimization algorithm based on two-archive mechanism for UAV 3-D path planning problem. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 167, 112306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Zhang, D.; He, Q.; Ban, Y.; Zuo, F. A novel multi-objective dung beetle optimizer for Multi-UAV cooperative path planning. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, U.; Varshney, S.; Jain, A.; Maheshwari, S.; Shukla, A. Three Dimensional Path Planning for UAVs in Dynamic Environment using Glow-worm Swarm Optimization. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 133, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.; De, D. RGSO-UAV: Reverse Glowworm Swarm Optimization inspired UAV path-planning in a 3D dynamic environment. Ad. Hoc Netw. 2023, 140, 103068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, N.; Boudjit, S.; Dauphin, G.; Zeadally, S. An obstacle avoidance approach for UAV path planning. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2023, 129, 102815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulares, M.; Barnawi, A. A novel UAV path planning algorithm to search for floating objects on the ocean surface based on object’s trajectory prediction by regression. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2021, 135, 103673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, H.; Faiçal, B.S.; Cardoso E Silva, A.V.; Ueyama, J. Use of UAVs for an efficient capsule distribution and smart path planning for biological pest control. Comput. Electron. Agr. 2020, 173, 105387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; He, X.; Cao, H.; Garg, S.; Kaddoum, G.; Hassan, M.M. AI-based energy-efficient path planning of multiple logistics UAVs in intelligent transportation systems. Comput. Commun. 2023, 207, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Huang, L.; Tian, K. Combinatorial optimization for UAV swarm path planning and task assignment in multi-obstacle battlefield environment. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 171, 112773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gao, X.; Wang, L.; Su, X.; Jin, J.; Liu, X.; Deng, Z. Resilient multi-objective mission planning for UAV formation: A unified framework integrating task pre- and re-assignment. Def. Technol. 2025, 45, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano Macias, J.; Angeloudis, P.; Ochieng, W. Optimal hub selection for rapid medical deliveries using unmanned aerial vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 110, 56–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.I.; Qadir, Z.; Munawar, H.S.; Nayak, S.R.; Budati, A.K.; Verma, K.D.; Prakash, D. UAVs path planning architecture for effective medical emergency response in future networks. Phys. Commun-Amst. 2021, 47, 101337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Yuan, G.; Xue, Y.; He, J.; Wang, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wang, Z. A deep reinforcement learning based distributed multi-UAV dynamic area coverage algorithm for complex environment. Neurocomputing 2024, 595, 127904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, H.; Du, S.; Hua, M.; Zhong, G. C-SPPO: A deep reinforcement learning framework for large-scale dynamic logistics UAV routing problem. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 38, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotee, S.; Kabir, F.; Razzaque, M.A.; Roy, P.; Mamun-Or-Rashid, M.; Hassan, M.R.; Hassan, M.M. Optimizing UAV-UGV coalition operations: A hybrid clustering and multi-agent reinforcement learning approach for path planning in obstructed environment. Ad. Hoc Netw. 2024, 160, 103519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Moon, J. Deep reinforcement learning-based model-free path planning and collision avoidance for UAVs: A soft actor–critic with hindsight experience replay approach. ICT Express 2023, 9, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsoshoara, A.; Lotfi, F.; Mousavi, S.; Afghah, F.; Güvenç, I. Joint path planning and power allocation of a cellular-connected UAV using apprenticeship learning via deep inverse reinforcement learning. Comput. Netw. 2024, 254, 110789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, H.; Hong, J.; Liu, M.; Zhang, C.; Liu, B. 3D UAV path planning in unknown environment: A transfer reinforcement learning method based on low-rank adaption. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Chen, W.; Lu, B.; Xiao, F.; Shen, C.; Zhang, W. An improved BAT algorithm for collaborative dynamic target tracking and path planning of multiple UAV. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 118, 109340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; Gai, W.; Zhong, M.; Zhang, J. A novel reinforcement learning based grey wolf optimizer algorithm for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) path planning. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 89, 106099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Mei, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Liu, J. Collision-free trajectory planning for UAVs based on sequential convex programming. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 152, 109404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Miao, F.; Mei, X. Facilitating Multi-UAVs application for rescue in complex 3D sea wind offshore environment: A scalable Multi-UAVs collaborative path planning method based on improved coatis optimization algorithm. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 324, 120701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, M.F.; Durdu, A.; Sabanci, K. Goal distance-based UAV path planning approach, path optimization and learning-based path estimation: GDRRT, PSO-GDRRT and BiLSTM-PSO-GDRRT. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 137, 110156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.; Khilar, P.M.; Senapati, B.R. A reinforcement learning-based cluster routing scheme with dynamic path planning for mutli-UAV network. Veh. Commun. 2023, 41, 100605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ding, M.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Q.; Shi, G.; Jiang, J. Large-scale UAV swarm path planning based on mean-field reinforcement learning. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 38, 103484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, N.; Jorquera, F.; Torres-Torriti, M.; Cheein, F.A. Model predictive path-following controller for Generalised N-Trailer vehicles with noisy sensors and disturbances. Control Eng. Pract. 2024, 142, 105747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, L.; Hu, M. In-flight fast conflict-free trajectory re-planning considering UAV position uncertainty and energy consumption. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2025, 171, 104988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, S.; Moh, S. Priority-aware task assignment and path planning for efficient and load-balanced multi-UAV operation. Veh. Commun. 2023, 42, 100633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, H.; Guo, R.; Zhou, J.; Zhu, X.; Ji, J.; Miao, Z. Reinforcement learning-based robust formation control for Multi-UAV systems with switching communication topologies. Neurocomputing 2025, 611, 128591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulares, M.; Fehri, A.; Jemni, M. UAV path planning algorithm based on Deep Q-Learning to search for a floating lost target in the ocean. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2024, 179, 104730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Tang, W.; Yang, Z.; Yang, X. Considering both energy effectiveness and flight safety in UAV trajectory planning for intelligent logistics. Veh. Commun. 2025, 52, 100885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Huo, M.; Li, Z.; Yu, Z.; Qi, N. Clustering-based hyper-heuristic algorithm for multi-region coverage path planning of heterogeneous UAVs. Neurocomputing 2024, 610, 128528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Long, X.; Li, Y.; Yan, J.; Li, M.; Chen, C.; Gu, F.; Pu, H.; Luo, J. Adaptive multi-UAV cooperative path planning based on novel rotation artificial potential fields. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 317, 113429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yang, C.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y. Research on 3D layered visibility graph route network model and multi-objective path planning for UAVs in complex urban environments. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 159, 109947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xie, C.; Ma, L.; Yang, L.; Zhang, T. Multi-objective evolutionary algorithm with two balancing mechanisms for heterogeneous UAV swarm path planning. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 173, 112927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Tan, G.; Si, H.; Li, J. DRL-GAT-SA: Deep reinforcement learning for autonomous driving planning based on graph attention networks and simplex architecture. J. Syst. Archit. 2022, 126, 102505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, X.; Tian, J. UAV formation path planning for mountainous forest terrain utilizing an artificial rabbit optimizer incorporating reinforcement learning and thermal conduction search strategies. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Jia, L.; Kuang, M.; Shi, H.; Zhu, J. An End-to-End Solution for Large-Scale Multi-UAV Mission Path Planning. Drones 2025, 9, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.; Shukla, S.; Kumar Singh, A. Trajectory-Prediction Techniques for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2025, 27, 1867–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Algorithm | NE | NCE | AR | PPTC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRPO | 100 | 121 | −3.6564 | × |

| 300 | 194 | 13.7749 | √ | |

| 500 | 167 | 9.8589 | √ | |

| Gat_GRPO | 100 | 19 | 6.5567 | √ |

| 300 | 42 | 18.2423 | √ | |

| 500 | 38 | 19.2321 | √ | |

| Mha_GRPO | 100 | 37 | 13.5614 | √ |

| 300 | 36 | 18.1224 | √ | |

| 500 | 54 | 19.7308 | √ | |

| G-MAPONet | 100 | 12 | 19.2423 | √ |

| 300 | 14 | 20.4214 | √ | |

| 500 | 23 | 20.6417 | √ |

| Algorithm | NE | NCE | AR | PPTC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRPO | 100 | 100 | −5.61 | × |

| 300 | 208 | 6.98 | √ | |

| 500 | 69 | 6.99 | √ | |

| G-MAPONet | 100 | 40 | 7.86 | √ |

| 300 | 24 | 19.12 | √ | |

| 500 | 15 | 19.24 | √ | |

| PPO | 100 | 52 | 6.45 | × |

| 300 | 31 | 15.39 | √ | |

| 500 | 17 | 18.77 | √ | |

| TRPO | 100 | 100 | −4.59 | × |

| 300 | 300 | −5.34 | × | |

| 500 | 500 | −15.96 | × | |

| A3C | 100 | 63 | −0.06 | × |

| 300 | 53 | 1.66 | √ | |

| 500 | 66 | 5.36 | √ | |

| DQN | 100 | 100 | −53.89 | √ |

| 300 | 150 | −124.89 | × | |

| 500 | 354 | −271.69 | √ |

| Attention Method | FRV | OASR |

|---|---|---|

| GRPO | 105.8465 | 0.9508 |

| G-MAPONet | 162.4949 | 0.9922 |

| PPO | 148.9217 | 0.8536 |

| TRPO | 109.4837 | 0.4700 |

| A3C | 81.8908 | 0.0117 |

| DQN | 112.5833 | 0.9427 |

| APF | 149.5476 | 0.9824 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deng, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Hua, M.; Sun, Y. A Method for UAV Path Planning Based on G-MAPONet Reinforcement Learning. Drones 2025, 9, 871. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120871

Deng J, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Hua M, Sun Y. A Method for UAV Path Planning Based on G-MAPONet Reinforcement Learning. Drones. 2025; 9(12):871. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120871

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeng, Jian, Honghai Zhang, Yuetan Zhang, Mingzhuang Hua, and Yaru Sun. 2025. "A Method for UAV Path Planning Based on G-MAPONet Reinforcement Learning" Drones 9, no. 12: 871. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120871

APA StyleDeng, J., Zhang, H., Zhang, Y., Hua, M., & Sun, Y. (2025). A Method for UAV Path Planning Based on G-MAPONet Reinforcement Learning. Drones, 9(12), 871. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120871