A Flexible Combinatorial Auction Algorithm (FCAA) for Multi-Task Collaborative Scheduling of Heterogeneous UAVs

Highlights

- A Flexible Combinatorial Auction Algorithm (FCAA) is proposed, which is designed with a candidate solution generation mechanism and a candidate solution addition mechanism to reduce the number of candidate solutions prior to combinatorial auctions. By calculating the benefits of candidate solutions based on real-time resource prices, the algorithm can dynamically adjust its priorities, thereby breaking the limitation that existing auction algorithms fail to efficiently and flexibly combine heterogeneous UAV resources for multi-task completion.

- Simulations show that the FCAA achieves a scheduling success rate of over 88% (with a maximum solution benefit proportion of 83.9%) in small-scale multi-tasking scenarios and a scheduling success rate of 98% (with a maximum solution benefit proportion of 93%) in multi-tasking scenarios, with significantly better time efficiency and solution quality than traditional algorithms.

- It provides an efficient solution to heterogeneous UAV resource scheduling in scenarios such as emergency rescue and intelligent logistics, addressing the low efficiency of traditional algorithms in large-scale tasks and improving the stability of resource allocation in complex environments.

- Its candidate solution mechanism supports adjusting solution valuations based on practical experience, enabling it to adapt to human–machine collaborative scenarios.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Problem Description and Model Construction

2.1. Resource-Task Modeling

2.2. Task Requirement Constraints

2.3. Design of Evaluation Indicators

2.3.1. Modeling of Search Tasks

2.3.2. Modeling of Delivery Tasks

2.4. Mathematical Model

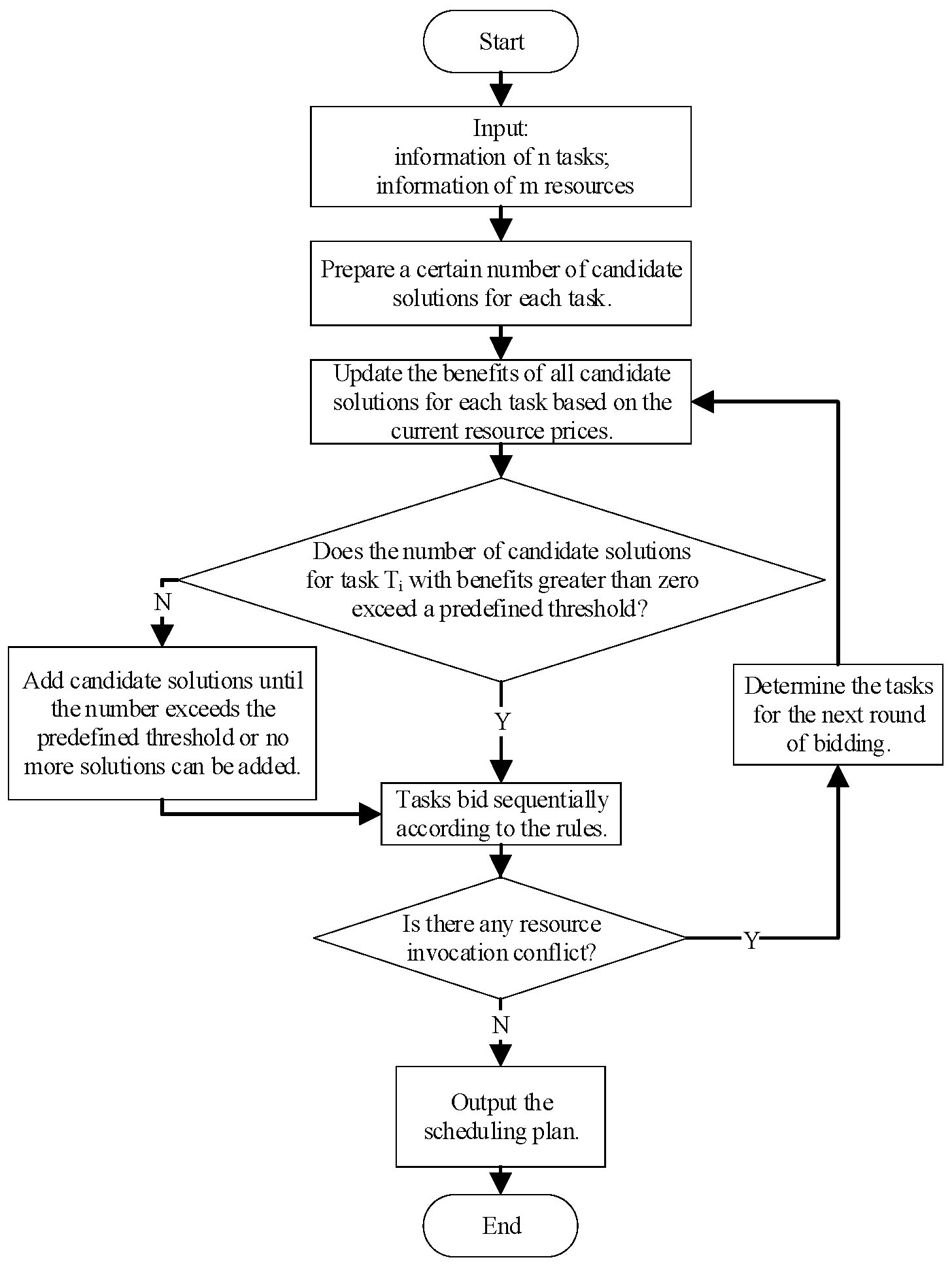

3. Flexible Combinatorial Auction Algorithm

3.1. Auction Algorithm

3.2. FCAA Bidding Mechanism and Execution

| Algorithm 1: First Batch Scheduling Candidate Solutions Generation Algorithm |

| Input: Task i, Resource set R = {R1, R2, …, Rm}, Resource set sorted by descending benefit αi = {Rj(1), Rj(2), …, Rj(m−1), Rj(m)}, Minimum required resources ui, Maximum available resources constraint Rmax, Number of candidate solutions generated per magnitude for independent resources num Output: First batch of scheduling candidate solutions S 1: Initialization: 2: S ← ∅//Initialization of candidate solution set 3: GroupR ← ∅//Initialization of resource group 4: ActiveR ← αi //Available resource pool 5: Base ← ∅//Initialization of candidate solutions 6: RemoveN ← 0 //Initialization of the count of deleted resources 7: GroupR ← αi [1..ui] //Select the first ui resources 8: if |GroupR| > Rmax then 9: return S //No feasible solutions satisfying constraints 10: while ActiveR ≠ ∅ do 11: if ui == 1 then://Independent resource: A single resource can complete the task 12: GroupR ← GroupR ∪ {all independent resources} 13: for g ∈ {1, …, |GroupR|} do 14: S ← S ∪ generate_combinations(GroupR, g, num)//Generate num solutions with g resources based on GroupR 15: ActiveR ← ActiveR\GroupR 16: ui ← update_the_minimum_required_resources(ActiveR) 17: GroupR ← αi [1..ui]//Select the first ui resources as GroupR 18: else if |GroupR| < Rmax + 1 then://The number of resources in GroupR is small. 19: Base ← generate_combinations (GroupR, −1, |GroupR| − 1)//Generate all candidate solutions with |GroupR| − 1 resources from GroupR. 20: S ← S ∪ filter_to_obtain_valid_solutions (Base)//Filter out invalid candidate solutions from Base 21: GroupR ← incorporate_new_resources (ActiveR)//Remove the optimal resource from ActiveR and add it to the end of GroupR. 22: else //The number of resources in GroupR is large. 23: while |GroupR| ≥ Rmax + 1 do 24: GroupR ← GroupR [2..end]//Maintain the total number of resources in GroupR at Rmax. 25: Base ← generate_combinations (GroupR, −1, Rmax)//Generate all candidate solutions with Rmax resources from GroupR 26: S ← S ∪ filter_to_obtain_valid_solutions (Base) 27: RemoveN ← RemoveN + 1 28: GroupR ← incorporate_new_resources (ActiveR)//Remove the optimal resource from ActiveR and add it to the end of GroupR. 29: if RemoveN ≥ ui or αi == ∅ then break 30: end while 31: end if 32: end while 33: return S |

- (i)

- Before initiating the auction algorithm, add a certain number of solutions to the task’s candidate solution library according to predefined rules;

- (ii)

- During the auction process, before task i submits a bid, the algorithm checks the number of solutions in its candidate solution library. If the count is below a predetermined threshold, the algorithm further checks for remaining available solutions. If any exist, add additional solutions to the library until the number of candidate solutions exceeds the threshold or no more solutions can be generated.

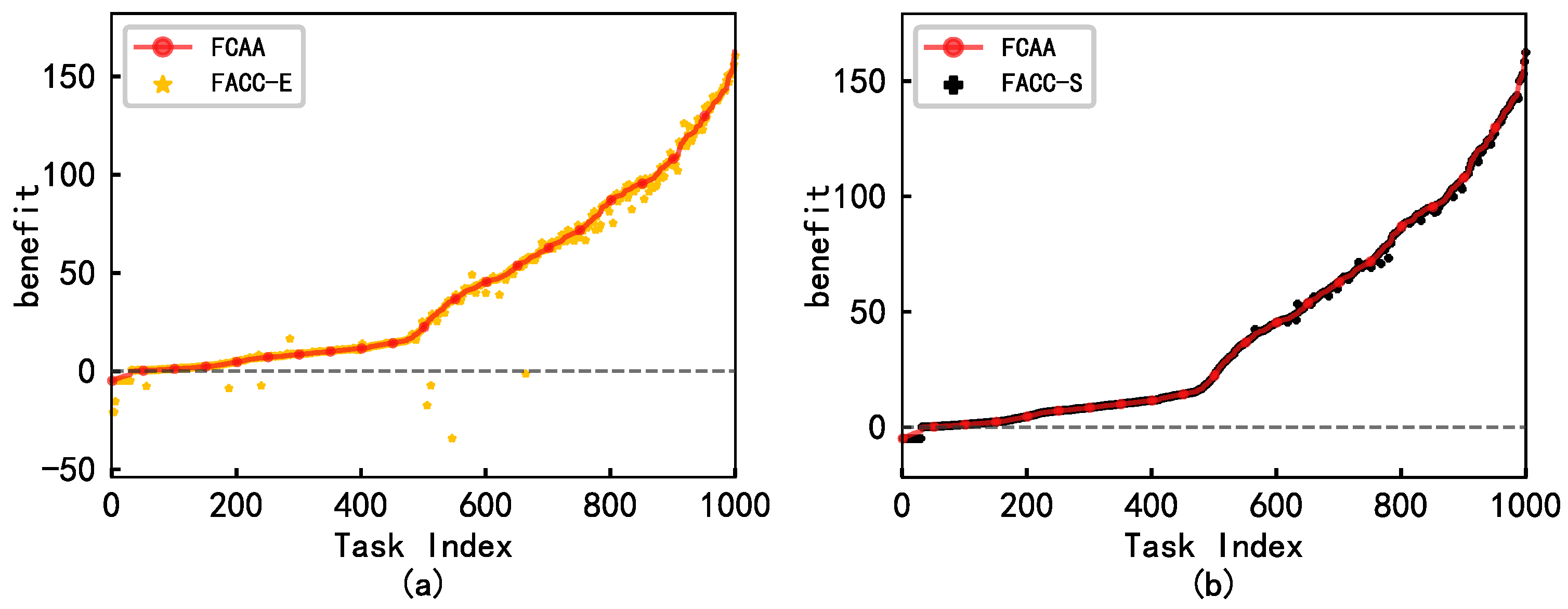

4. Ablation Studies and Simulation

4.1. Ablation Studies

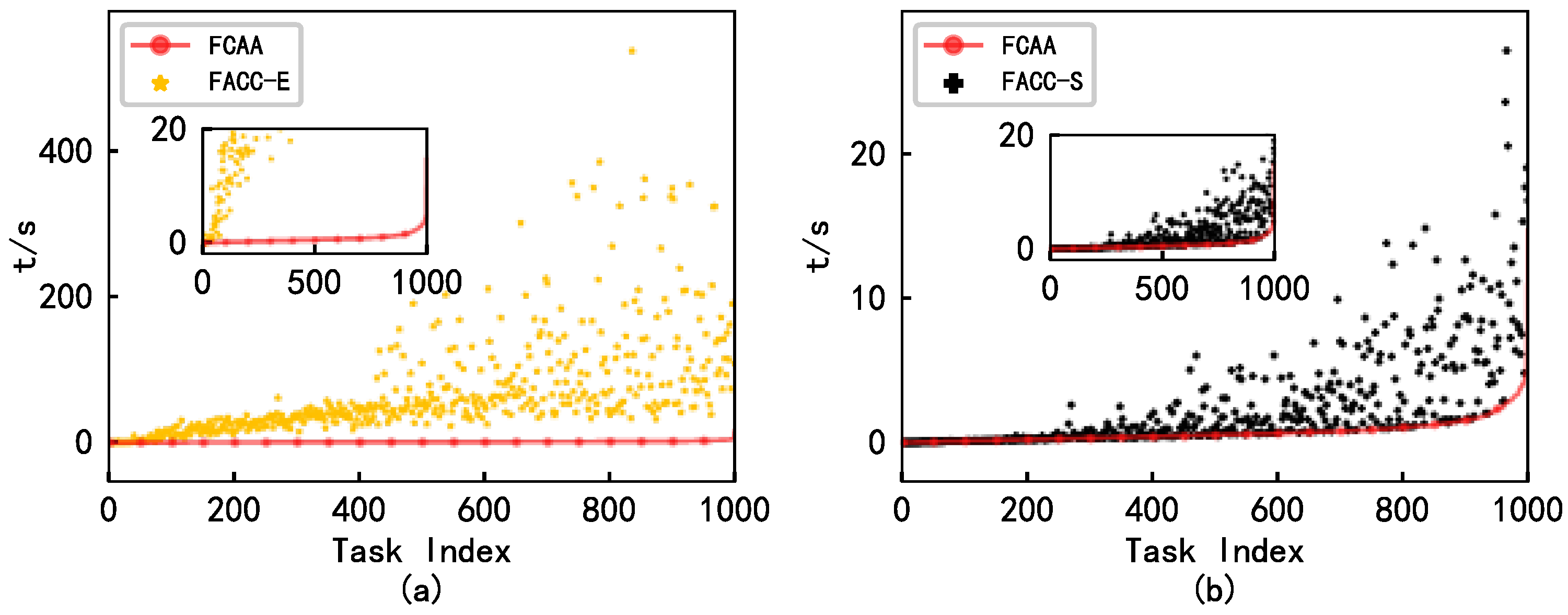

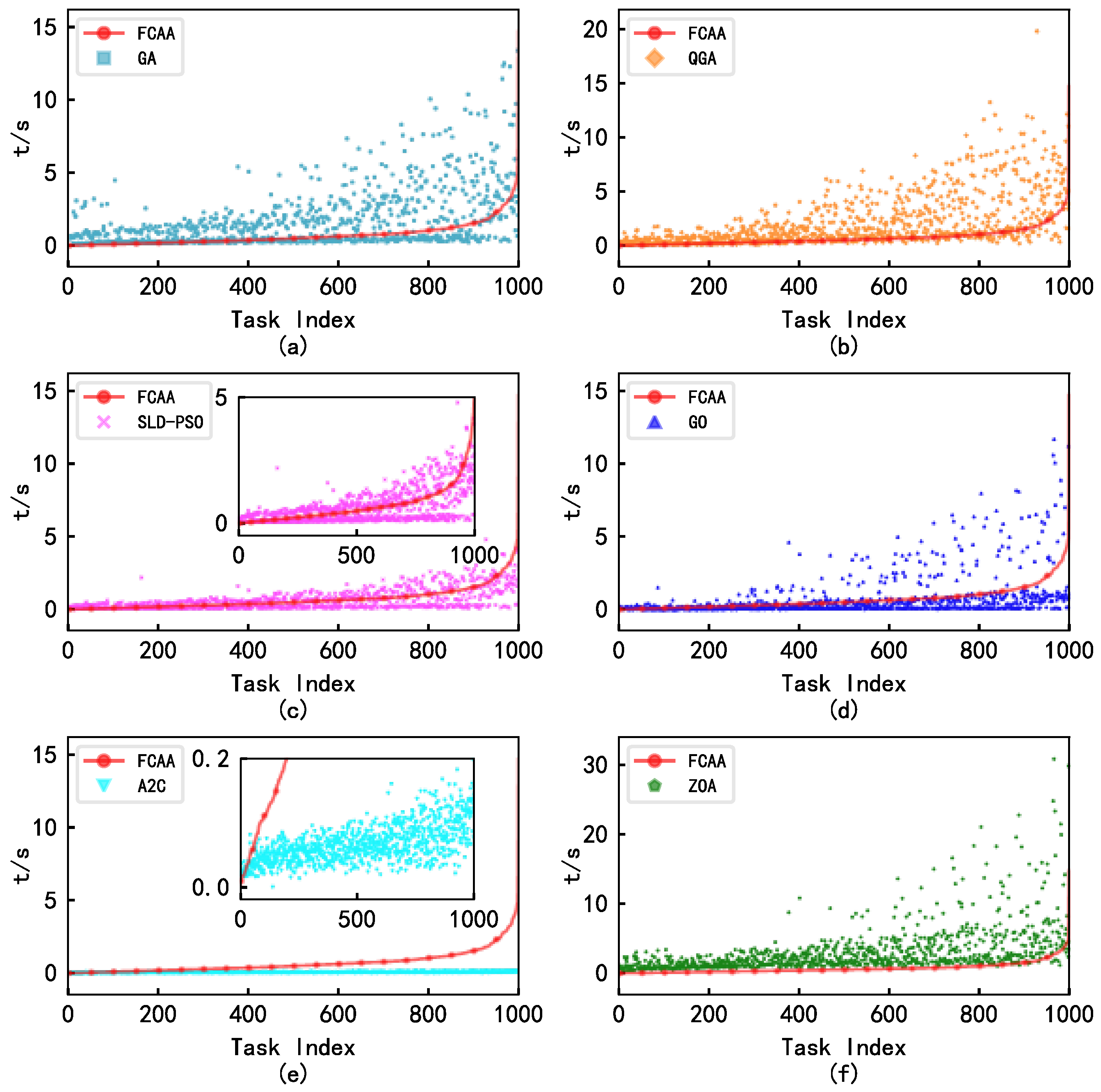

4.2. Small-Scale Multi-Task Resource Scheduling

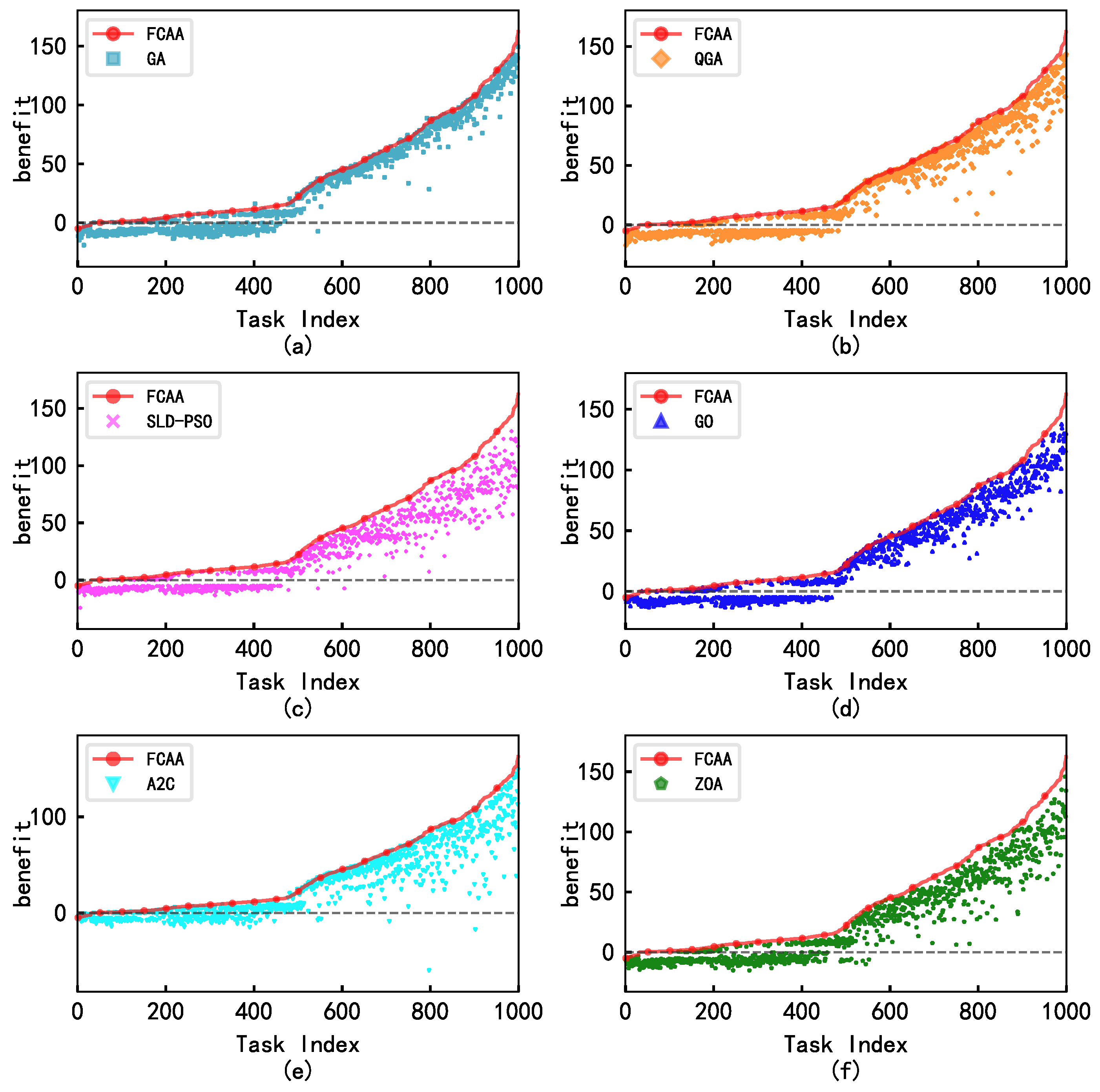

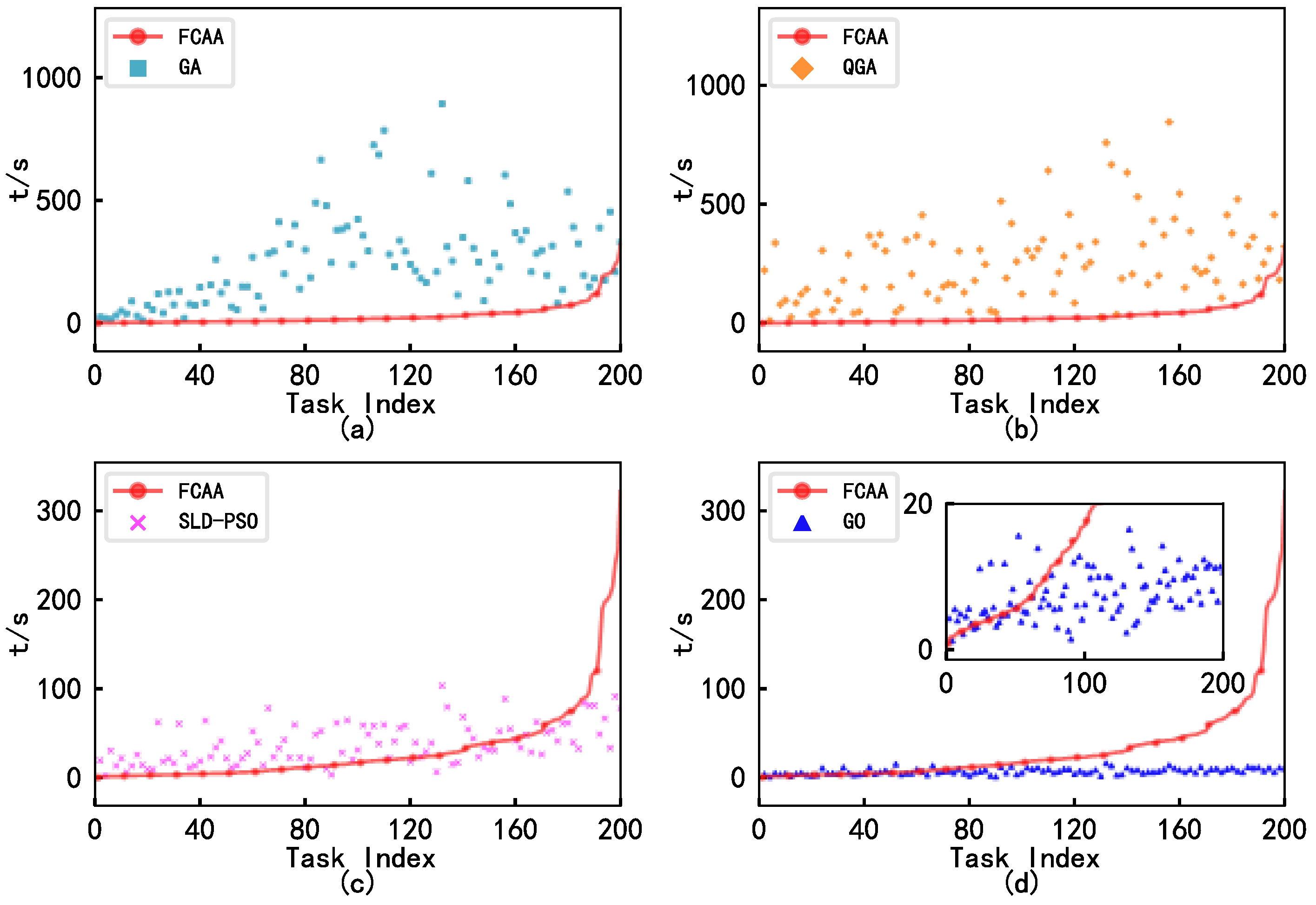

4.3. Multi-Task Resource Scheduling

5. Conclusions

- (i)

- The FCAA achieves higher solution quality and time efficiency when solving simple scheduling problems of this type. In simulations of coordinating resources to complete small-scale scheduling tasks, all heuristic algorithms and reinforcement learning models could successfully handle over 60% of the small-scale task cases, but the FCAA consistently yielded the highest benefit solutions in most cases.

- (ii)

- The FCAA significantly outperforms the compared algorithms in solving complex multi-task scheduling problems. It demonstrates a superior scheduling benefit, a higher scheduling success rate, and greater solution stability.

- (iii)

- The optimization mechanism of the FCAA is better aligned with real-world resource scheduling constraints. By leveraging its candidate solution generation mechanism, the FCAA enables flexible adjustment of solution values and seamless incorporation of practical experience through whitelists and blacklists. This enhances the practical applicability of its solutions, particularly in human–machine collaborative task environments.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alam, M.M.; Moh, S. Joint optimization of trajectory control, task offloading, and resource allocation in air–ground integrated networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 24273–24288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, B.; Shi, Z.; Li, J. A hybrid task allocation approach for multi-UAV systems with complex constraints: A market-based bidding strategy and improved NSGA-III optimization. J. Supercomput. 2025, 81, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhengrong, J.; Faxing, L.; Hangyu, W. Multi-stage attack weapon target allocation method based on defense area analysis. J. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2020, 31, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan’gang, L.; Zheng, Q. A decision support system for satellite layout integrating multi-objective optimization and multi-attribute decision making. J. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2019, 30, 535–544. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.; Shi, C.; Wen, W.; Zhou, J. Multi-Mission Oriented Joint Optimization of Task Assignment and Flight Path Planning for Heterogeneous UAV Cluster. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punnen, A.P. The Traveling Salesman Problem: Applications, Formulations and Variations; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.; Li, L.; Teng, L.; Wen, Y. Multi-UAV reconnaissance task allocation for heterogeneous targets using an opposition-based genetic algorithm with double-chromosome encoding. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2018, 31, 339–350. [Google Scholar]

- Savla, K.; Frazzoli, E.; Bullo, F. Traveling salesperson problems for the Dubins vehicle. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2008, 53, 1378–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floudas, C.A.; Lin, X. Mixed integer linear programming in process scheduling: Modeling, algorithms, and applications. Ann. Oper. Res. 2005, 139, 131–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouwenaars, T.; De Moor, B.; Feron, E.; How, J. Mixed integer programming for multi-vehicle path planning. In Proceedings of the 2001 European Control Conference (ECC), Porto, Portugal, 4–7 September 2001; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; pp. 2603–2608. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Fan, Q. Resource allocation optimization based on mixed integer linear programming in the multi-cloudlet environment. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 24533–24542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, R.J.M.; Maximo, M.R.O.A.; Galvão, R.K.H. Task allocation and trajectory planning for multiple agents in the presence of obstacle and connectivity constraints with mixed-integer linear programming. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2020, 30, 5464–5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jiahao, X. Cooperative task assignment of multi-UAV system. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2020, 33, 2825–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Yu, J.; Ai, X.; Xu, X.; Yang, D. Cooperative multiple task assignment problem with stochastic velocities and time windows for heterogeneous unmanned aerial vehicles using a genetic algorithm. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2018, 76, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gao, X.; Wang, L.; Su, X.; Jin, J.; Liu, X.; Deng, Z. Resilient multi-objective mission planning for UAV formation: A unified framework integrating task pre-and re-assignment. Def. Technol. 2025, 45, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunchong, Z.; Yan’gAng, L.; Zeyang, X.; Yingjie, J.; Kebo, L. Multi-type Task Assignment Algorithm for Heterogeneous UAV Cluster Based on Improved NSGA-II. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Guidance, Navigation and Control, Changsha, China, 9−11 August 2024; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 554–567. [Google Scholar]

- Khosiawan, Y.; Park, Y.; Moon, I.; Nilakantan, J.M.; Nielsen, I. Task scheduling system for UAV operations in indoor environment. Neural Comput. Appl. 2019, 31, 5431–5459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Feng, J.; Pan, F. A distributed task allocation method for multi-UAV systems in communication-constrained environments. Drones 2024, 8, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojovská, E.; Dehghani, M.; Trojovský, P. Zebra optimization algorithm: A new bio-inspired optimization algorithm for solving optimization algorithm. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 49445–49473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Zhou, R.; Huang, P.; Jing, Y.; Liu, G. SLDPSO-TA: Track Assignment Algorithm Based on Social Learning Discrete Particle Swarm Optimization. Electronics 2024, 13, 4571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Gao, H.; Zhan, Z.-H.; Li, J.; Zhang, H. Growth Optimizer: A powerful metaheuristic algorithm for solving continuous and discrete global optimization problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 261, 110206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, R. A distributed task scheduling method based on conflict prediction for ad hoc UAV swarms. Drones 2022, 6, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Liu, H.; Tang, H.; Cai, Q.; Zhang, F.; Han, X. A novel hybrid auction algorithm for multi-UAVs dynamic task assignment. IEEE Access 2019, 8, 86207–86222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, I.; Jewell, K.; Vohra, R. A Simple Model of Coalitional Bidding. Econ. Theory 2002, 19, 435–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.S.; Lim, W.Y.B.; Dai, H.N.; Xiong, Z.; Huang, J.; Niyato, D.; Hua, X.S.; Leung, C.; Miao, C. Joint auction-coalition formation framework for communication-efficient federated learning in UAV-enabled Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 22, 2326–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.L.; Brunet, L.; How, J.P. Consensus-based decentralized auctions for robust task allocation. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2009, 25, 912–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, W.; Shi, G.; Jiang, F.; Chowdhury, M.; Ling, S.H. UAV swarm mission planning in dynamic environment using consensus-based bundle algorithm. Sensors 2020, 20, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhenshi, Z.; Huan, L.; Guohua, W. A Dynamic Task Scheduling Method for Multiple UAVs Based on Contract Net Protocol. Sensors 2022, 22, 4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, T.; Ding, H.; Ping, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Q.; Quek, T.Q. Satellite-Assisted UAV Control: Sensing and Communication Scheduling for Energy Efficient Data Collection. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Wang, L.; Chang, Z.; Xu, L.; Fei, A. Multi-Agent DRL-Based Coded Caching and Resource Allocation in UAV-Assisted Networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yang, R.; Liu, L.; Wu, C. Service placement and trajectory design for heterogeneous tasks in multi-UAV edge computing networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 12, 9360–9371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Xu, C.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Yang, S.; Muntean, G.-M. Reliability-aware optimization of task offloading for uav-assisted edge computing. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2025, 74, 3832–3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, Y.; Gao, H.; Li, K.; Almeida, L.; Tovar, E.; Han, Z. Age of information minimization using multi-agent uavs based on ai-enhanced mean field resource allocation. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 13368–13380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Kuang, M.; Shi, H.; Gao, J. Multi-UAV Cooperative Target Assignment Method Based on Reinforcement Learning. Drones 2024, 8, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kwan, R.S.K. A fuzzy genetic algorithm for driver scheduling. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2003, 147, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Xi, B.; Yi, G.; Zhao, H.; Zhong, J. A multiple heterogeneous UAVs reconnaissance mission planning and re-planning algorithm. J. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2022, 33, 1190–1207. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.; Shen, L.; Zheng, Y. Genetic algorithm based approach for multi-UAV cooperative reconnaissance mission planning problem. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Methodologies for Intelligent Systems, Bari, Italy, 27–29 September 2006; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Ma, J.; Lu, J.; Li, D. Research on Optimal Target Matching of Multiple Projectiles and Multiple Targets. In Proceedings of the Chinese Intelligent Systems Conference, Guiling, China, 26–27 October 2024; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 511–516. [Google Scholar]

- Wellman, M.P.; Osepayshvili, A.; MacKie-Mason, J.K.; Reeves, D. Bidding strategies for simultaneous ascending auctions. BE J. Theor. Econ. 2008, 8, 0000102202193517041461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsekas, D.P. The auction algorithm: A distributed relaxation method for the assignment problem. Ann. Oper. Res. 1988, 14, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutanoglu, E.; David Wu, S. On combinatorial auction and Lagrangean relaxation for distributed resource scheduling. IIE Trans. 1999, 31, 813–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Notation | Description | Type | Range & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rr | UAV-borne radar search capability index | Resource Capability Index | [0, 1]; Larger values indicate stronger UAV capability |

| Ri | UAV-borne infrared search capability index | ||

| Ro | UAV-borne electro-optical search capability index | ||

| Re | UAV-borne electronic signal search capability index | ||

| Rm | UAV-borne magnetometer search capability index | ||

| Ra | UAV-borne search accuracy index | ||

| Rd | UAV-borne comprehensive delivery capability index | ||

| Rai | UAV-borne search anti-interference capability index | ||

| Tr | Radar search capability requirement index for the task | Task Requirement Index | [0, 1]; Larger values indicate higher required by the task |

| Ti | Infrared search capability requirement index for the task | ||

| To | Electro-optical search capability requirement index for the task | ||

| Te | Electronic signal search capability requirement index for the task | ||

| Tm | Magnetometer search capability requirement index for the task | ||

| Ta | Search accuracy requirement index for the task | ||

| Td | Comprehensive delivery capability requirement index for the task | ||

| Tai | Search anti-interference capability requirement index for the task |

| Order of Single Resource Matching Degree | Resource Group | Candidate Solution Generation Rules |

|---|---|---|

| Rj(1),Rj(2), …,Rj(m−1),Rj(m) | Rj(1), Rj(2), …, Rj(u1−1) | All independent resources form the resource group, and a specific number of candidate solutions are, respectively, generated within the order of magnitude from 1 to u1 − 1. |

| Rj(u1) | The resource group cannot complete the task. | |

| Rj(u1), Rj(u2) | The resource group cannot complete the task. | |

| … | … | |

| Rj(u1), Rj(u2), …, Rj(ui) | Generate ui − u1 + 1 solutions, where each solution includes ui − u1 resources. | |

| … | … | |

| Rj(u1), Rj(u2), …, Rj(u1+Rmax) | Generate Rmax + 1 solutions, where each solution includes Rmax resources. | |

| … | … | |

| Rj(ui), …, Rj(ui+ui)/ R(ui+Rmax) | Generate ui + 1/Rmax + 1 solutions, where each solution includes ui/Rmax resources. |

| Order of Single Resource Matching Degree | Resource Group | Candidate Solution Generation Rules |

|---|---|---|

| Rj(u+1),Rj(u+2), …,Rj(m−1),Rj(m) | Rj(u+1) | The resource group cannot complete the task. |

| Rj(u+1), Rj(u+2) | The resource group cannot complete the task. | |

| … | … | |

| Rj(u+1), …, Rj(u+1+ui) | Generate ui + 1 solutions, where each solution includes ui resources. | |

| … | … | |

| Rj(u+1), …, Rj(u+1+Rmax) | Generate Rmax + 1 solutions, where each solution includes Rmax resources. | |

| … | … | |

| Rj(u+1+ui), …, Rj(u+1+2×ui)/Rj(u+1+ui+Rmax) | Generate ui + 1/Rmax + 1 solutions, where each solution includes ui/Rmax resources. |

| Total Number of Simulation Cases | Average Number of Tasks per Case | Average Number of Resources per Case |

|---|---|---|

| 1000 | 2–3 | 53–54 |

| Algorithm | Case Scheduling Success Rate | Task Completion Rate | Average Benefit | Proportion of Maximum Benefit | Average Runtime (t/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCAA | 88.5% | 95.0% | 42.2 | 77.3% | 0.74 |

| FCAA-E | 77.0% | 86.4% | 41.4 | 70.2% | 70.01 |

| FCAA-S | 88.5% | 94.8% | 42.0 | 70.7% | 2.48 |

| Algorithm | Standardized Benefit Data | Normalized Time Data | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Dev. | 95% CI | Mean | Std. Dev. | 95% CI | |

| FCAA | 0.007 | 0.46 | [−0.02, 0.007] | 1.01 | 0.03 | [1.003, 1.005] |

| FCAA-E | 0.087 | 0.79 | [0.04, 0.09] | 110.1 | 93.9 | [104.2, 110.0] |

| FCAA-S | −0.094 | 0.44 | [−0.12, −0.09] | 2.73 | 3.21 | [2.531, 2.730] |

| Item | Actor Network | Critic Network |

|---|---|---|

| Core Structure | Embedding layer + LSTM Encoder/Decoder + glimpse/pointer mechanisms | Embedding layer + LSTM Encoder + glimpse mechanism + fully connected layer |

| Input | Resource-Task-relevant Status (e.g., coordinates, speed) | Resource-Task-relevant Status |

| Output | action log probabilities | State values |

| Update Basis | Advantage evaluated by Critic | Error between actual return and predicted value |

| Algorithm | Core Parameter Category | Parameter Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| GA | Population Size | max(resource_count, 50) |

| Number of Generations | max(resource_count, 30) | |

| Change Rate | 0.4 | |

| Mutation Rate | 0.2 | |

| QGA | Population Size | max(resource_count, 50) |

| Number of Generations | max(resource_count, 30) | |

| Mutation_Rate | 0.1 | |

| Bit_Mutation Rate | 0.01 | |

| SLD-PSO | Population Size | max(resource_count × 0.4, 20) |

| Number of Generations | max(resource_count, 60) | |

| Acceleration Factor c1 | Linearly decreasing (0.9 → 0.15) for individual cognition. | |

| Acceleration Factor c2 | Linearly increasing (0.4 → 0.9) for social learning. | |

| GO | Population_Size | max(resource_count × 2, 40) |

| Maximum Function Evaluations | max(resource_count2, 2000) | |

| Population Division Parameter | 5 | |

| Retention Probability Parameter | 0.001 | |

| Elite Guidance Probability Parameter | 0.3 | |

| ZOA | Population Size | max(resource_count, 50) |

| Number of Generations | max(resource_count, 30) | |

| Defense Strategy Coefficient | 0.01 |

| Algorithm | Case Scheduling Success Rate | Task Completion Rate | Average Benefit | Proportion of Maximum Benefit | Average Runtime (t/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCAA | 88.5% | 95.0% | 42.2 | 83.9% | 0.74 |

| GA | 67.2% | 86.8% | 33.7 | 5.9% | 1.63 |

| QGA | 52.6% | 80.4% | 31.7 | 6.6% | 2.01 |

| SLD-PSO | 46.1% | 76.6% | 24.8 | 0.1% | 0.62 |

| GO | 61.3% | 84.6% | 30.2 | 4.5% | 0.28 |

| A2C | 64.0% | 82.1% | 29.5 | 0.3% | 0.07 |

| ZOA | 52.3% | 79.3% | 26.1 | 4% | 3.10 |

| Algorithm | Standardized Benefit Data | Normalized Time Data | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Dev. | 95% CI | Mean | Std. Dev. | 95% CI | |

| FCAA | 1.03 | 0.23 | [1.01, 1.04] | 10.44 | 9.96 | [9.82, 11.06] |

| GA | −0.13 | 0.66 | [−0.18, −0.09] | 22.6 | 23.81 | [21.12, 24.07] |

| QGA | −0.29 | 0.62 | [−0.33, −0.25] | 26.27 | 22.99 | [24.85, 27.7] |

| A2C | 0.26 | 0.84 | [−0.31, −0.20] | 1.01 | 0.12 | [1.01, 1.03] |

| ZOA | −0.88 | 0.6 | [−0.91, −0.84] | 45.89 | 50.4 | [42.76, 49.01] |

| SLD-PSO | −0.96 | 0.64 | [−1.00, −0.93] | 8.18 | 6.75 | [7.76, 8.6] |

| GO | −0.44 | 0.59 | [−0.48, −0.4] | 9.63 | 16.79 | [8.59, 10.67] |

| Total Number of Simulation Cases | Average Number of Tasks per Case | Average Number of Resources per Case |

|---|---|---|

| 200 | 11–12 | 184–185 |

| Algorithm | Core Parameter Category | Parameter Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| GA | Population Size | max(resource_count, 100) |

| Number of Generations | max(resource_count, 60) | |

| QGA | Population Size | max(resource_count, 100) |

| Number of Generations | max(resource_count, 60) | |

| SLD-PSO | Population Size | max(resource_count × 0.4, 80) |

| Number of Generations | max(resource_count, 150) | |

| GO | Population_Size | max(resource_count × 1.2, 150) |

| Maximum Function Evaluations | max(resource_count2, 8000) |

| Algorithm | Case Scheduling Success Rate | Task Completion Rate | Average Benefit | Proportion of Maximum Benefit | Average Runtime (t/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCAA | 98.0% | 99.2% | 272.4 | 93% | 33.15 |

| GA | 21.0% | 80.75% | 199.0 | 0.5% | 256.82 |

| QGA | 4.5% | 58.94% | 131.4 | 4% | 258.07 |

| SLD-PSO | 5.5% | 59.38% | 117.7 | 1% | 39.18 |

| GO | 6.0% | 61.32% | 123.5 | 1.5% | 7.45 |

| Algorithm | Standardized Benefit Data | Normalized Time Data | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Dev. | 95% CI | Mean | Std. Dev. | 95% CI | |

| FCAA | 1.29 | 0.45 | [1.27, 1.32] | 5.65 | 9.37 | [5.07, 6.23] |

| GA | 0.27 | 0.64 | [0.23, 0.31] | 50.96 | 103.85 | [44.51, 57.4] |

| QGA | −0.33 | 0.6 | [−0.37, −0.29] | 38.9 | 45.4 | [36.08, 41.72] |

| SLD-PSO | −0.65 | 0.44 | [−0.68, −0.62] | 5.69 | 4.33 | [5.42, 5.96] |

| GO | −0.58 | 0.47 | [−0.61, −0.55] | 1.23 | 0.78 | [1.18, 1.27] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, L.; Gong, X.; Zheng, J.; Wang, Y.; Cui, Y. A Flexible Combinatorial Auction Algorithm (FCAA) for Multi-Task Collaborative Scheduling of Heterogeneous UAVs. Drones 2025, 9, 870. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120870

He L, Gong X, Zheng J, Wang Y, Cui Y. A Flexible Combinatorial Auction Algorithm (FCAA) for Multi-Task Collaborative Scheduling of Heterogeneous UAVs. Drones. 2025; 9(12):870. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120870

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Leiming, Xudong Gong, Jiangan Zheng, Yue Wang, and Yunsen Cui. 2025. "A Flexible Combinatorial Auction Algorithm (FCAA) for Multi-Task Collaborative Scheduling of Heterogeneous UAVs" Drones 9, no. 12: 870. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120870

APA StyleHe, L., Gong, X., Zheng, J., Wang, Y., & Cui, Y. (2025). A Flexible Combinatorial Auction Algorithm (FCAA) for Multi-Task Collaborative Scheduling of Heterogeneous UAVs. Drones, 9(12), 870. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120870