1. Introduction

The integration of Internet of Things (IoT) technologies into Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) systems has enabled the creation of networks with enhanced autonomy and scalability. IoT-enabled UAV networks are increasingly essential in areas such as emergency response and logistics. However, with their growing prevalence, ensuring operational security becomes critical, especially in dynamic and distributed environments. In such dynamic, distributed UAV swarms [

1], reintegration of outlier UAVs without a reliable security mechanism can threaten mission continuity and fleet safety [

2]. Common causes of UAV disconnections include issues such as command-and-control (C2) link outages, signal obstructions from terrain or buildings, and hardware failures, all of which increase the risk of key leakage or firmware tampering. Therefore, a robust security mechanism is needed to verify the trustworthiness of returning UAVs, with reintegration difficulty increasing in proportion to the duration of their absence. Centralized key management, which suffers from a single point of failure (SPOF), static policies, and a heavy dependence on real-time connectivity to the Ground Control Station (GCS), fails to meet the time-sensitive needs of these systems [

3].

To address the limitations of centralized key management, blockchain-based decentralized architectures [

4,

5,

6] offer a promising solution. By utilizing consensus mechanisms and an append-only distributed ledger, blockchain enables secure key coordination, decentralized identity verification, and tamper-evident auditability, eliminating reliance on a central authority and overcoming the SPOF issue. Decentralized control mitigates the risk of SPOF by distributing authority and responsibilities, enhancing network resilience and fault tolerance. Furthermore, blockchain’s immutability ensures that all actions related to key management are transparent and auditable, providing verifiable records that prevent unauthorized alterations. The scalability of blockchain also supports dynamic network topologies, making it suitable for decentralized UAV swarms where nodes frequently join and leave. Together, these properties establish a secure and autonomous infrastructure that enhances the integrity, availability, and security of key management in large-scale distributed systems.

Dynamic key management in decentralized UAV swarms can be broadly categorized into interactive [

7,

8,

9] and non-interactive methods [

10,

11]. Interactive schemes rely on multi-round authentication to safeguard against impersonation, but such designs can lead to increased CPU and bandwidth costs, especially when multiple nodes rejoin simultaneously. Additionally, they are vulnerable to delays and packet loss in multi-hop networks and may create bottlenecks at leader nodes or stable peers. On the other hand, non-interactive schemes reduce coordination by allowing nodes to advance their local key states and verify them later through recent ciphertexts or on-chain records. However, these methods often overlook the duration of a node’s absence, leading to inefficiencies in reintegration cost allocation. In both cases, the duration of absence is not directly tied to the reintegration difficulty, which can result in short absences being penalized excessively and long absences receiving insufficient penalties.

In this paper, we introduce the Salted Temporal Key (STK) scheme, a blockchain-based, time-constrained dynamic key update strategy that ties the reintegration cost to the number of missed blocks. STK is non-interactive, enabling efficient reintegration for both short and long outages by dynamically adjusting the verification difficulty in proportion to the outlier duration. The approach achieves a balance between security and operational flexibility, making it particularly suitable for IoT-enabled UAV networks requiring secure and scalable communication. The key innovation is the dynamic adjustment of reintegration difficulty based on outlier duration, ensuring stronger security for long-term outlier nodes while enabling fast reintegration for short-term outliers.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on dynamic keying for UAV swarms,

Section 3 presents the background and problem formulation;

Section 4 details the STK architecture and workflow;

Section 5 analyzes security;

Section 6 reports performance evaluation on reintegration latency, scalability, cross-network adaptability, and resource usage; and

Section 7 concludes.

2. Related Work

This section reviews the literature on dynamic group key management, tracing the architectural evolution from centralized to decentralized and identifying key security challenges.

2.1. Evolution from Centralized to Decentralized Architecture

Traditional key management schemes, such as UAV-KAS proposed in [

12], often rely on a centralized architecture in which key generation and distribution are fully controlled by a single entity, such as the Ground Control Station (GCS) or a designated head node. While such schemes are effective in simpler systems, they suffer from inherent risks like the SPOF and scalability bottlenecks, particularly when the number of UAVs in the swarm grows. A typical example of this is the Group Identifier (GID) generation mechanism used in UAV-KAS, which is vulnerable to these issues. Furthermore, the centralized nature of these schemes presents significant challenges in maintaining real-time communication and security as the UAV network grows, given that all key updates and distribution rely on a central node.

To address these limitations, research has progressively shifted toward decentralized designs. Fully decentralized schemes use blockchains to distribute trust for key management and identity. The threshold key-management system in [

13] strengthens swarm security with multisignatures, while BASUV [

14] combines multiple public key generators with blockchain to provide decentralized UAV identity and certificate management, and it supports dynamic joining and revocation. By contrast, IDBC [

15] organizes nodes into clusters and assigns consensus and block generation to a small set of “cluster heads,” leaving the system partially centralized. This arrangement can create a single point of failure and partition risks.

2.2. Mainstream Decentralized Reintegration Mechanisms

Research on dynamic, fully decentralized key management for UAV swarms generally falls into two paradigms, interactive identity authentication and non-interactive key update, with a focus on the secure reintegration of outlier nodes.

Interactive schemes ensure the legitimacy of reintegrating UAVs through multi-round identity authentication [

8,

16]. These schemes require an outlier node to engage in interactions such as challenge-response or digital signature verification with stable nodes within the swarm. This interactive method prevents impersonation attacks but consumes valuable swarm resources, reducing overall system efficiency. SBP [

7] performs event-driven interactive group rekeying: upon any membership change, the leader broadcasts a single rekey message to all valid members. By contrast, the baseline scheme in the same work, the PKU (an interactive public key unicast) approach, in which the leader maintains pairwise keys and encrypts/transmits per recipient, incurs CPU and bandwidth costs that scale linearly with group size. A blockchain-backed, mutual-healing group key distribution scheme for UAV ad hoc networks (UAANETs) is proposed in [

9]. In this scheme, a Ground Control Station builds a private blockchain to record group keys and member certificates. Under the Longest-Lost-Chain strategy, temporarily isolated UAVs recover missing session keys by interacting with neighboring nodes.

Non-interactive key-update schemes aim to reduce interaction costs through non-interactive key updates, with key Self-Healing mechanisms being a typical example. However, a common limitation in the security models of both Self-Healing and other mainstream dynamic key schemes is that they are event-driven rather than time-driven. For instance, hash-chain-based schemes [

17], while achieving dynamic key derivation, fail to translate the outlier duration into a quantifiable authentication cost. Similarly, hierarchical group key management schemes [

10] improve rekeying efficiency and key freshness but generally overlook how the duration of desynchronization should influence reintegration cost. The trust-based Self-Healing scheme in [

11] exemplifies non-interactive group rekeying: the manager broadcasts polynomial-encoded update material, and legitimate members locally recover, achieving revocation and forward/backward secrecy without per-node handshakes. The location-updating-based Self-Healing scheme in [

18] targets VANETs and embeds location information into group-key computation to let vehicles refresh keys non-interactively from broadcast material. By analogy, UAV swarms with reliable localization can adopt the same broadcast-and-derive paradigm to reduce handshakes under high mobility.

The STK scheme proposed in this paper addresses this gap with a time-driven, noninteractive reintegration process that links verification difficulty to the verifiable disconnection duration. By coupling admission cost to missed consensus cycles and leveraging a decentralized ledger, STK reduces interaction overhead and avoids centralized trust.

3. Background

This section establishes the technical background for the STK framework. It begins by detailing the Proof of Verifiable Functions (PoVF) consensus mechanism [

19], which provides a secure and efficient foundation for the entire scheme. Subsequently, it discusses the security challenges inherent in the reintegration of outlier nodes within dynamic distributed systems, using UAV swarms as a prime example to define the problem STK is designed to solve.

3.1. PoVF Consensus

PoVF stands for Proof of Verifiable Functions, a consensus mechanism that ensures fair and unbiased leader election. Unlike traditional consensus mechanisms that depend on intensive computation (such as PoW), PoVF uses cryptographic primitives to achieve leader selection in a verifiable and unbiased manner. The protocol leverages a combination of Verifiable Random Functions (VRFs) [

20] and Verifiable Delay Functions (VDFs) [

21], which together ensure that leader election is both secure and resistant to manipulation. These cryptographic tools provide a foundation for PoVF’s unique approach to block proposer eligibility and consensus timing, which is explained in more detail in the following sections.

Verifiable Random Functions (VRFs): A VRF is a cryptographic tool that allows a key holder to generate a pseudorandom output that can be publicly verified. In essence, a node uses its secret key and a public seed to compute a random output along with a proof of correctness. This proof enables anyone with the public key to confirm that the output is legitimate, yet it is impossible to predict the output without the secret key. In PoVF, this mechanism is used to select candidates for block production, ensuring the process is both random and resistant to manipulation.

Verifiable Delay Functions (VDFs): A VDF is a function that requires a specific number of sequential steps to compute, but its result can be verified almost instantly. Its defining feature is that the computation cannot be accelerated via parallel processing, thereby enforcing a predictable real-time delay. In PoVF, a VDF imposes a mandatory waiting period after a node is selected by the VRF. This delay prevents adversaries from pre-computing results or gaining an unfair advantage, securing the consensus by proving the block producer waited for the required duration.

3.2. Security Challenges in Time-Sensitive UAV Reintegration

In UAV swarms, intermittent disconnections and outlier events are common due to the highly dynamic network topology. The duration of an outlier UAV plays a critical role in determining whether and how it can safely reenter the swarm. To quantify the difficulty of reintegration for outlier UAVs, we introduce the concept of the consensus cycle in blockchain. A consensus cycle is the fundamental time unit for completing block consensus among the UAVs in the swarm, and it serves as a standard for measuring outlier duration. Outlier duration is measured by the number of consensus cycles missed by the outlier UAV, and outlier events are categorized into three types according to this metric: transient outliers, short-term outliers, and long-term outliers.

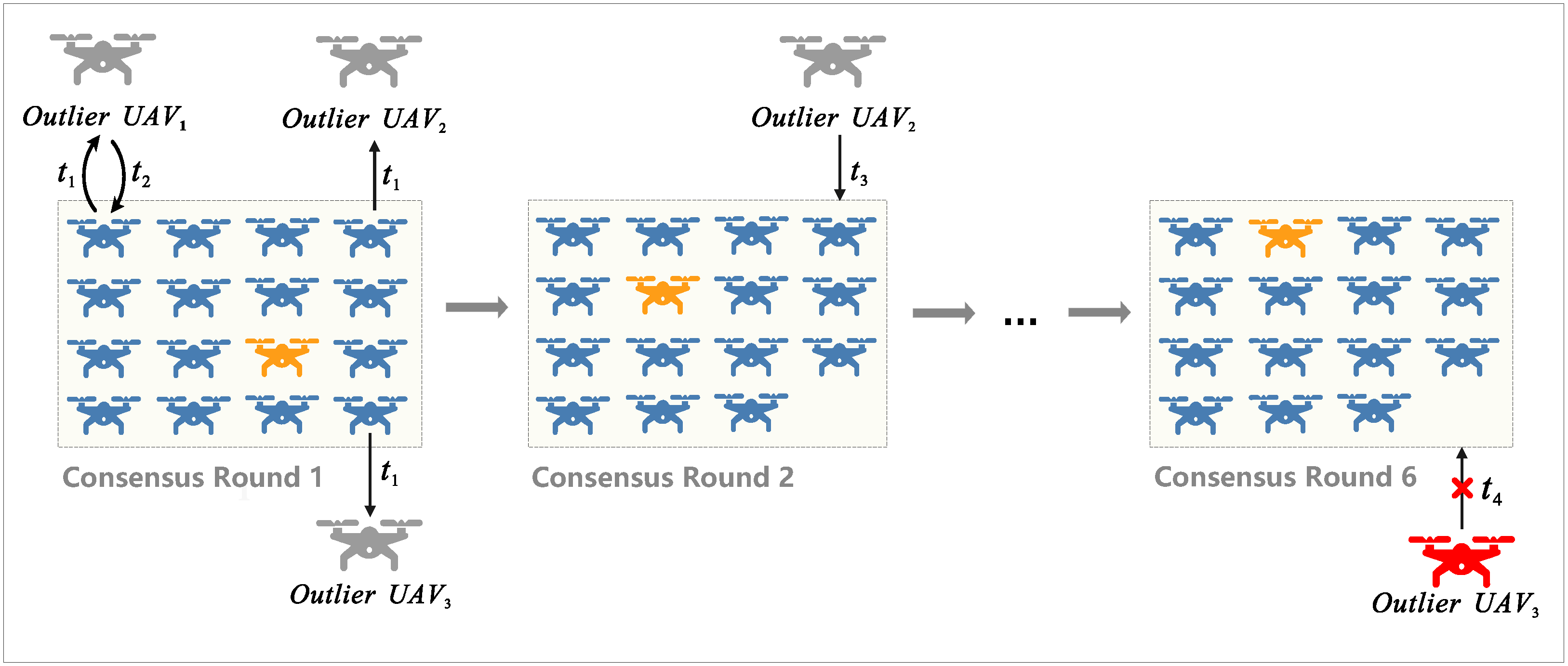

Transient Outliers: A transient outlier denotes a brief disconnection caused by signal jitter or momentary occlusion, during which a UAV temporarily loses contact. Reintegration proceeds automatically upon link restoration. The duration is extremely short, and the security risk to the swarm is negligible. For example, in the first consensus cycle shown in

Figure 1, the behavior of UAV

1 is classified as a transient outlier, with reintegration occurring at minimal verification difficulty.

Short-term Outliers: This category covers disconnections due to external factors such as signal interference, typically lasting from several minutes to tens of minutes. If the UAV returns within the swarm’s predefined tolerance window, its identity remains valid and reintegration is seamless. UAV2 exhibits outlier behavior in the first consensus cycle and successfully reintegrates in the second consensus cycle with minimal verification difficulty.

Long-term Outliers: A long-term outlier occurs when the disconnection duration exceeds the tolerance threshold because of hardware failure, energy depletion, or adversarial capture. Prolonged disconnections increase the risk of data leakage and network attacks. In

Figure 1, UAV

3 exceeds the valid number of consensus cycles for reintegration and is deemed untrustworthy; it is therefore permanently excluded from the swarm to preserve system integrity.

To clarify the technical details discussed in the following sections,

Table 1 summarizes the key notations used throughout this paper, along with their definitions.

4. Architecture

This section introduces the STK scheme, a framework integrating a hierarchical security architecture with a blockchain-orchestrated key lifecycle management scheme. We detail its architectural design and core operational mechanisms, covering distributed key evolution and autonomous recovery. These components build a trustless coordination framework to ensure secure operations in dynamic swarms, effectively addressing the transient UAV failures and time-bound security risks inherent to decentralized networks.

4.1. System Architecture

The proposed STK mechanism utilizes a layered security architecture, which includes three distinct layers: the network transport layer, the consensus layer, and the application layer. Each layer performs critical functions to ensure the secure and efficient operation of the UAV swarm.

In the networking (transport) layer, UAVs form a quasi-static peer-to-peer overlay to ensure stable communication and enable synchronized key updates at each cycle’s start. Membership changes take effect at cycle boundaries, and periodic broadcasts, governed by the interval , enforce secure communication and continuous key synchronization across the swarm.

The consensus layer utilizes the PoVF consensus mechanism, a dynamic election method that selects the consensus UAV (C-UAV). This layer facilitates decentralized decision-making and plays a crucial role in selecting UAVs to perform specific tasks. The PoVF mechanism divides UAVs into two categories based on their roles in each consensus cycle:

Consensus UAV (C-UAV): The C-UAV is selected dynamically via the PoVF consensus mechanism. It is responsible for validating the transaction pool, deriving the per-cycle key-salting parameter , encrypting the block to form , and broadcasting it to the network.

Member UAV: The member UAV decrypts using , then parses from the decrypted block data, updates , and derives the session key ; it then verifies data integrity and uses for secure end-to-end communication.

The application layer includes essential modules for key generation, reintegration, and communication management within the swarm.

Dynamic Key Management Module: In this module, UAVs generate the session key for the current cycle by deriving after recovering , ensuring that all nodes in the swarm synchronize their keys. This module guarantees that the UAVs have a consistent and secure keying system throughout their operations, which is crucial for ensuring secure communications during dynamic swarm activities.

Self-Healing Module: The Self-Healing module provides a solution for temporarily isolated member UAVs to recover and reintegrate into the swarm. When a UAV is temporarily disconnected, the Self-Healing module allows it to restore its keys based on the root key chain, non-interactively enumerating -round candidate parameters and testing the resulting keys against the latest block ciphertext .

Database: The database stores the root key chain used to generate dynamic session keys. It ensures the security and efficiency of the key management process, enabling the system to keep track of the necessary cryptographic materials needed for communication and reintegration.

The STK architecture ensures efficient communication and operation in dynamic UAV swarms. In the consensus layer, the PoVF mechanism ensures fair and unpredictable role assignment, thus maintaining system security and robustness against adversarial attacks. Additionally, the application layer’s dynamic key management and Self-Healing modules play a vital role in securing the communication and enabling the smooth reintegration of temporarily isolated UAVs.

4.2. Dynamic Key Evolution

The STK scheme utilizes a recursive process for dynamic key evolution, where the dynamic key evolves with each consensus cycle, denoted by t. To ensure the effectiveness of this process, (broadcast interval), as a key time parameter within the swarm, controls the duration of each consensus cycle and directly determines the frequency of dynamic key updates within the swarm. By dynamically adjusting , the operational efficiency of the consensus mechanism can be optimized according to task requirements.

At the start of a swarm task, the swarm sets an appropriate value based on the specific needs of the task. In the initialization cycle (), a PoVF-elected C-UAV generates the genesis block, extracts a parameter , and derives the initial session key . All member UAVs then synchronize this initial key.

For each subsequent cycle

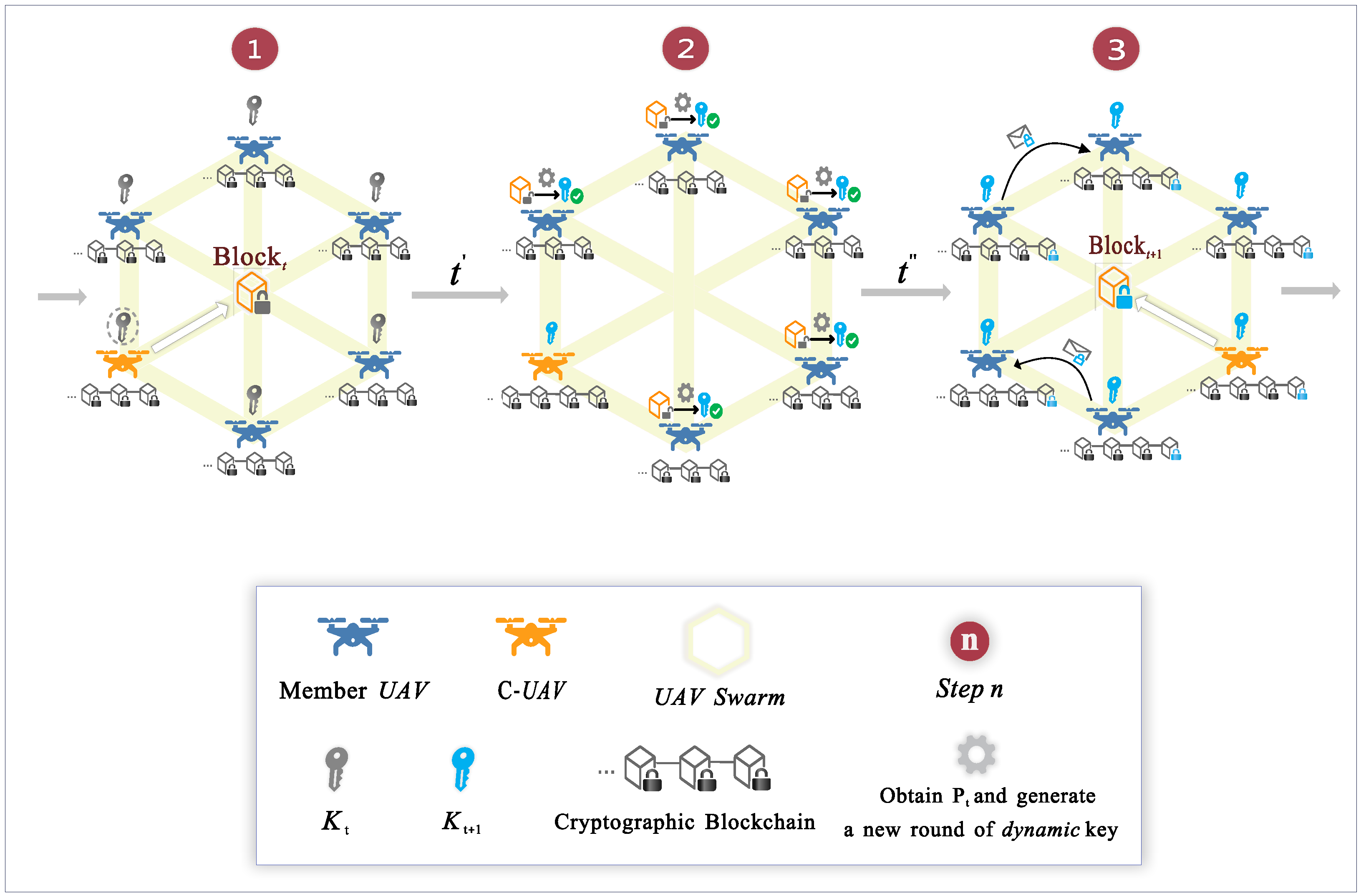

, the process proceeds as shown in

Figure 2:

Step 1: The C-UAV samples a new key-salting parameter and assembles the block payload (containing and operational data). According to the configured broadcast interval , the C-UAV broadcasts a block carrying the ciphertext . The header commitment is used for data integrity verification.

Step 2: Each member UAV receives the ciphertext and attempts to decrypt it using the key . If decryption yields a valid result (), the UAV extracts from and extends its local key chain to . The new session key is then derived as .

Step 3: Once the block is verified and the key is updated, the member UAV uses to securely communicate within the current cycle t.

This recursive process ensures the dynamic update of the communication key, which is defined as

where the key at each cycle

t is derived from the concatenation of all previous parameters

.

4.3. Self-Healing Reintegration

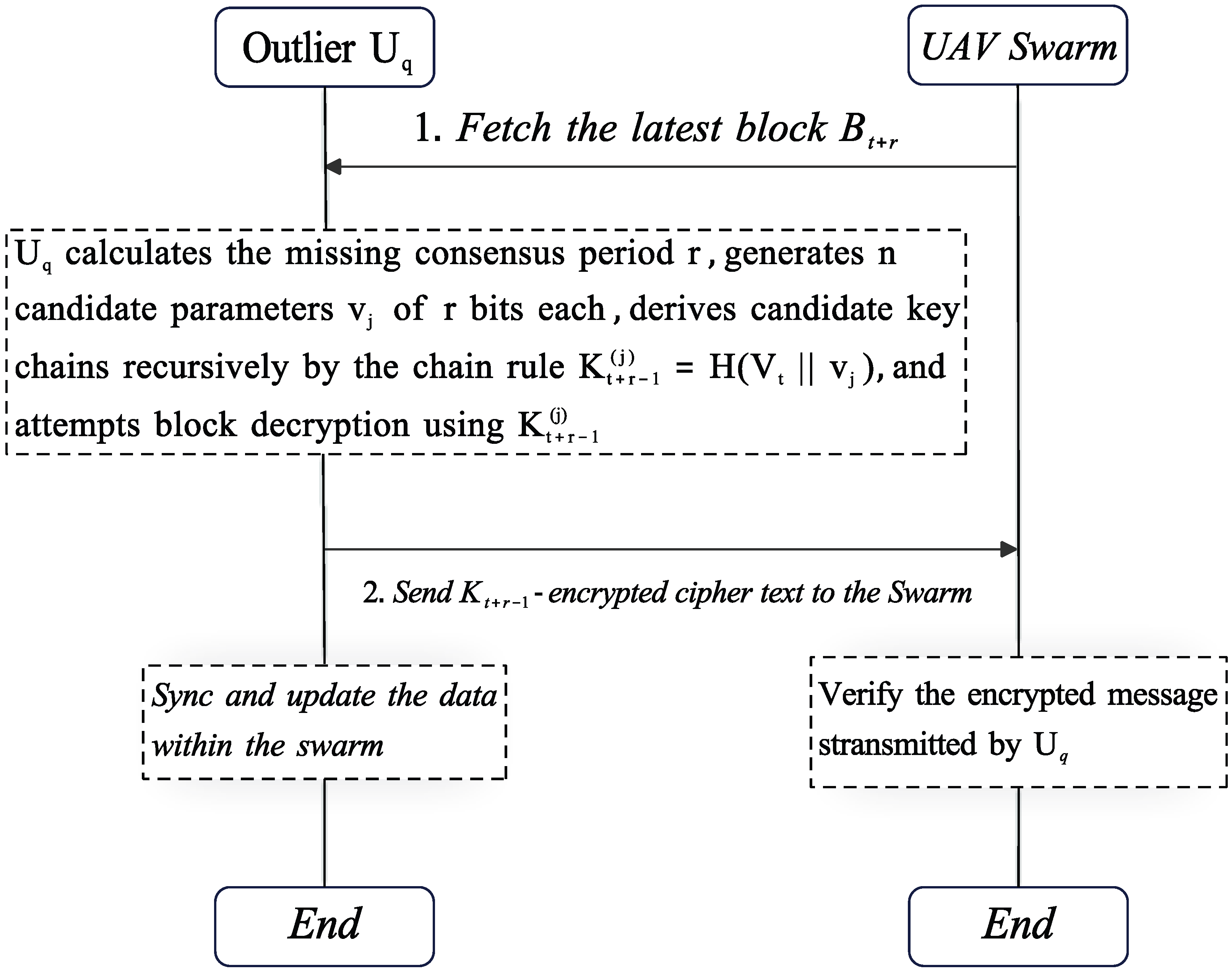

The reintegration process for outlier UAVs leverages the Self-Healing module in STK, as illustrated in

Figure 3. When a UAV

disconnects from the swarm, it records a timestamp

. After missing

r consensus cycles,

approaches the swarm, retrieves the latest block

, and activates the Self-Healing module based on the historical root key chain

stored locally. The number of missed cycles

r is calculated as

where

is the current time,

is the timestamp recorded at the moment of disconnection (retrieved from the database), and

is the consensus cycle interval. The ceiling function ensures that even a partial cycle is counted as a full cycle, accounting for any fractional part of the time difference.

It then generates

n candidate parameter sequences of length

, denoted as

. After that, the historical root key chain

is retrieved from the database and concatenated with each

for chain-based hashing to obtain a set of candidate keys:

then attempts to decrypt the latest block ciphertext:

If

and structurally valid, then

Once the new session key is computed, is considered fully synchronized with the swarm and resumes secure communication. The UAV subsequently synchronizes with the blockchain by retrieving and processing any missed blocks. Only upon complete synchronization of the blockchain state can the UAV be deemed eligible for participation in the next C-UAV election cycle.

5. Security Analysis

This section provides a systematic analysis of the system’s security in two parts. First, in

Section 5.1, a threat model and defense objectives are constructed through informal security analysis. Then, in

Section 5.2, a formal security proof model is established based on cryptographic assumptions.

5.1. Informal Security Analysis

5.1.1. Threat Model

In this framework, adversaries may exploit the authentication mechanisms and dynamic key management procedures of disconnected nodes to launch various attacks, aiming to compromise the system’s security and consistency. The adversarial model assumes the following capabilities:

Communication eavesdropping and parallel attacks:

- -

Adversaries may monitor communication between disconnected UAVs and the swarm, intercepting encrypted data and blocking broadcasts in transit.

- -

Adversaries may simultaneously launch parallel attacks against multiple disconnected UAVs, capturing and stealing the locally stored root key chains and blockchain replicas from the targeted UAVs.

Impersonation and Data Interception: Adversaries can impersonate legitimate UAVs to infiltrate swarm communication channels and intercept encrypted data and blocks.

Computational Resource Limitations: The adversaries’ computational capability increases polynomially, permitting brute-force attempts on the current swarm’s dynamic keys under specific conditions.

Based on these adversarial capabilities, the UAV swarm is exposed to the following potential threat scenarios:

Brute-force Attacks: An adversary

exhaustively searches all possible combinations of dynamic parameters [

22], attempting to recover the target key before expiration within the current key cycle.

Precomputation Attacks:

intercepts the disconnected UAV’s root key chain data, generates candidate keys for the missed rounds, and, upon nearing the swarm, intercepts blocks to perform extensive key matching tests [

23], aiming to identify valid keys.

Replay Attacks: intercepts the disconnected UAV’s root key chain database, generates multiple sets of candidate keys, and uses previously verified keys to decrypt data and blocks in subsequent rounds.

5.1.2. Security Goals

The security objectives of the scheme are to ensure the long-term protection of UAV swarms in open environments through cryptographic guarantees and dynamic mechanisms. Specifically, the scheme provides the following core defensive capabilities:

Resistance to Brute-force Attacks: Adversaries cannot recover historical communication keys by exhaustively enumerating dynamic parameter chains within polynomial time. The probability that succeeds is negligible in the security parameter .

Resistance to Precomputation Attacks: Adversaries cannot precompute valid parameters satisfying . The ’s advantage can be reduced to the hardness of the Second-Preimage Resistance (SPR) problem inherent in cryptographic hash functions.

In addition, the STK scheme effectively mitigates the risk of replay attacks through a cycle-driven key rotation strategy. The system generates a unique key for each consensus cycle and immediately invalidates all previous keys, preventing attackers from reusing expired keys for replay.

5.2. Formal Security Proof

This section formally analyzes the proposed time-window-based dynamic key management scheme, focusing on brute-force and Precomputation attacks. Through the entropy-driven computational infeasibility analysis, we demonstrate that the system can withstand both types of attacks under standard cryptographic assumptions [

24], as detailed below.

5.2.1. Resistance to Brute-Force Attacks

Resistance to brute-force attacks is formally demonstrated through entropy-driven infeasibility analysis, with the primary objective of suppressing

’s real-time computational capabilities by ensuring exponential expansion of the candidate parameter space. After intercepting the root key chain

,

adaptively selects candidate parameter chains

at most

times within polynomial time, where each parameter satisfies

, where

represents a configurable alphabet space or parameter space with a cardinality of 62 for this example. This value is intended to serve as a conservative estimate, with the actual size of

depending on the specific implementation or cryptographic function used. The

then performs real-time hash queries to identify a second-preimage satisfying

The

’s success probability follows a binomial distribution, given by

The size of the candidate space,

, grows exponentially with

r. According to standard cryptographic assumptions [

25], when the number of rounds

r of the dynamic parameter chain grows super-logarithmically with respect to the security parameter

(i.e.,

), the candidate space

expands super-polynomially, while the

’s computational capability

grows only polynomially. We have

Thus, the ’s success probability within polynomial time, , is a negligible function, directly demonstrating the infeasibility of brute-force attacks by the in polynomial time.

5.2.2. Resistance Against Precomputation Attacks

The security proof against Precomputation attacks is based on a reduction to a cryptographic hardness assumption, with the core goal being to explicitly construct a reduction algorithm that binds the ’s advantage to the SPR assumption.

Suppose the

intercepts an isolated UAV and obtains the root key chain

at the moment of isolation. The

attempts to pre-compute a candidate parameter chain.

such that a future candidate key at time

satisfies

and matches the swarm’s actual key over multiple future rounds:

where

denotes the legitimate parameter used by the swarm.

The goal of the is to find, with non-negligible advantage , a value such that the above equation holds.

The security proof can be formulated as follows. The

’s success condition is to construct a value

such that

thereby contradicting the second-preimage resistance (SPR) property of

. This contradiction confirms the system’s security against Precomputation attacks. We formalize this reduction in Algorithm 1 (the Key-Chain SPR Reduction Algorithm), which captures the complete interaction between the challenger and the adversary.

| Algorithm 1 Reduction Algorithm for the SPR Game |

- Require:

Security parameter , threshold , value space , max queries Q - Ensure:

Second preimage or ⊥ - 1:

Challenger Initialization: - 2:

- 3:

- 4:

- 5:

- 6:

Send to - 7:

Adversary Precomputation: - 8:

for to Q do - 9:

- 10:

- 11:

end for - 12:

- 13:

Reduction Verification: - 14:

if then - 15:

return - 16:

else - 17:

return ⊥ - 18:

end if

|

Following the above reduction, the

’s advantage can now be formally bounded. Based on the reduction framework in [

24], it can be derived that if the

has an advantage

in breaking the target system, then there exists an algorithm

that can break the second-preimage resistance (SPR) property of the hash function

with at least the same advantage:

Since collision resistance (e.g., SHA-256) implies second-preimage resistance, it follows from the SPR definition that

which in turn yields

Furthermore, assuming the hash output length satisfies

, the

’s success probability via brute-force search is bounded as

In summary, under both the SPR assumption and the output length constraint, the

’s overall success probability is bounded by

6. Performance Evaluation

Experimental evaluation of the STK scheme employed a dual approach, focusing on practical deployability and large-scale performance.

Real-Platform Deployment: We deployed the complete STK pipeline on multiple Raspberry Pi 3 Model B+ devices integrated into actual UAV airframes, as shown in

Figure 4. Runtime tests confirmed that the full STK pipeline—including key derivation, updates, and reintegration—executes reliably within the device’s computational and memory constraints. It seamlessly coexists with the existing onboard software stack, validating its operational stability and resource efficiency under real-world embedded conditions.

Large-Scale Emulation: To evaluate reintegration performance, scalability, and adaptability in larger, dynamic UAV swarms, we constructed a distributed simulation environment based on an open-source verifiable function blockchain platform. This setup emulated swarms of 50 to 100 nodes using cloud instances on Tencent Cloud, each configured identically to the Raspberry Pi 3 Model B+ devices. This ensured a consistent hardware profile across both real and emulated tests. The environment facilitated a comprehensive evaluation of reintegration latency, scalability, and cross-network adaptability under conditions designed to closely replicate real UAV network behavior.

The hardware and software configurations for both environments are summarized in

Table 2. For comparative analysis, we considered two swarm sizes: a medium swarm with 50 UAVs (SubSwarm-A) and a large swarm with 100 UAVs (SubSwarm-B). To capture latency with high temporal precision, critical events—from the initial detection of an outlier UAV to its final reintegration—were logged using the deployed monitoring tools.

6.1. Reintegration Latency Across Swarm Sizes

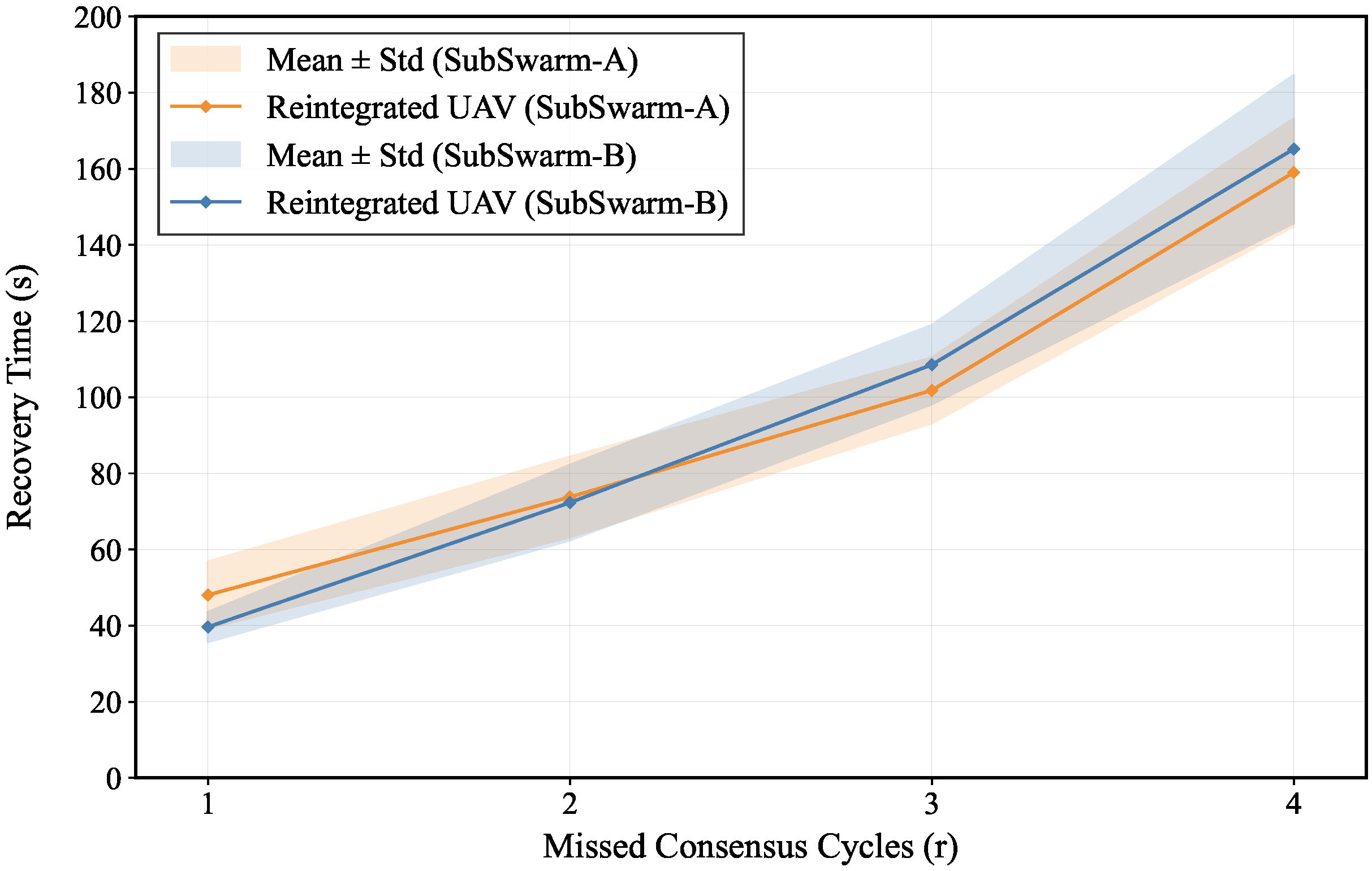

As illustrated in

Figure 5, the reintegration latency exhibits a consistently increasing trend with respect to the number of missed consensus cycles. Specifically, the median reintegration time in SubSwarm-A increased from

at

to

at

, while the median reintegration time in SubSwarm-B increased from

to

over the same range. The corresponding growth rates—

and

, respectively—differed by less than 7%, and their 95% confidence intervals overlapped substantially across all values of

r. These results explicitly confirm that the reintegration latency is essentially decoupled from swarm size, highlighting the scalability and topological neutrality of the proposed protocol.

The primary cause of the observed latency increase can be attributed to the exponential expansion of the candidate key space within the dynamic key chain structure. As r increases, the number of valid key candidates grows from 62 at to approximately at , which significantly increases the computational burden of key matching and leads to longer reintegration times. In parallel, we observed a systematic reduction in temporal variance, consistent with the entropy constraining effect of the candidate pruning mechanism. The reintegration time variance in SubSwarm-A decreased from at to at , an 81.6% reduction. Similarly, the variance in SubSwarm-B dropped from to , a 73.5% decrease. This convergence reflects the narrowing of valid reintegration paths under cumulative entropy constraints and further demonstrates that the reintegration dynamics are primarily governed by the key space structure rather than swarm topology or size.

The observed reintegration latency of outlier UAVs in two swarms of different sizes exhibits an exponential relationship with the number of missed consensus cycles r, independent of the swarm size. This directly reflects the exponential growth of the candidate key space . Outlier UAVs must enumerate a candidate space of size . The difficulty of reintegration is closely related to the number of consensus cycles r missed by the outlier UAVs. As the number of missed consensus cycles increases, the computational cost for reintegration grows exponentially. The exponential expansion of significantly increases the computational difficulty of reintegration, making random guessing of (the session key for consensus cycle t) computationally infeasible. This computational complexity provides a temporal security barrier for outlier UAVs, ensuring the security of the reintegration process, and this security is independent of the swarm size.

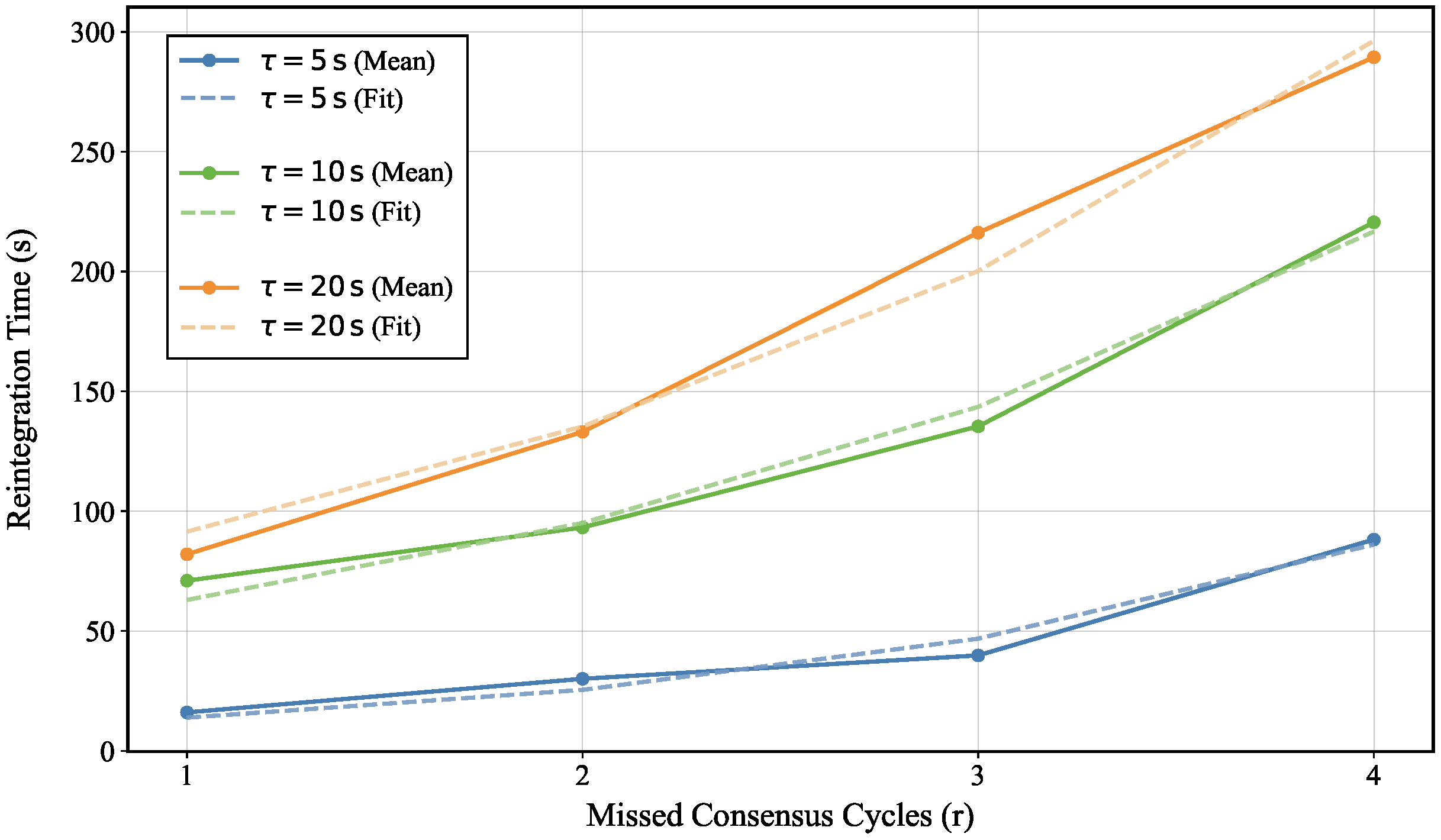

6.2. Configurable STK Reintegration Time

To evaluate the scalability of the STK scheme, we analyzed reintegration latency for fixed swarm sizes over missed consensus cycles (

to 4) under three broadcast intervals (

). As shown in

Figure 6, the reintegration time increases approximately linearly with

r within the tested range. The slopes of the fitted lines indicate that increasing the broadcast interval

exacerbates the growth rate of the latency.

The results across the three configured broadcast intervals demonstrate the STK scheme’s adaptability to various real-world deployment scenarios. These values were selected to address key operational needs: a short interval () for latency-sensitive, coordinated maneuvers; a medium interval () for general surveillance and mobility tasks; and a longer interval () for energy-efficient, wide-area operations where network delays are more significant.

The findings indicate that is a key factor in controlling reintegration latency. Specifically, smaller values reduce delays for low-latency tasks, while larger values enhance robustness for wide-area coordination. By adjusting , the STK scheme effectively isolates UAVs with excessive delays, ensuring reliable communication within the swarm.

Overall, the STK scheme provides a flexible security framework. The tunable broadcast interval allows system operators to optimize the trade-off between reintegration latency and robustness according to specific mission requirements and network conditions. This ensures secure and efficient swarm operation across diverse deployment environments.

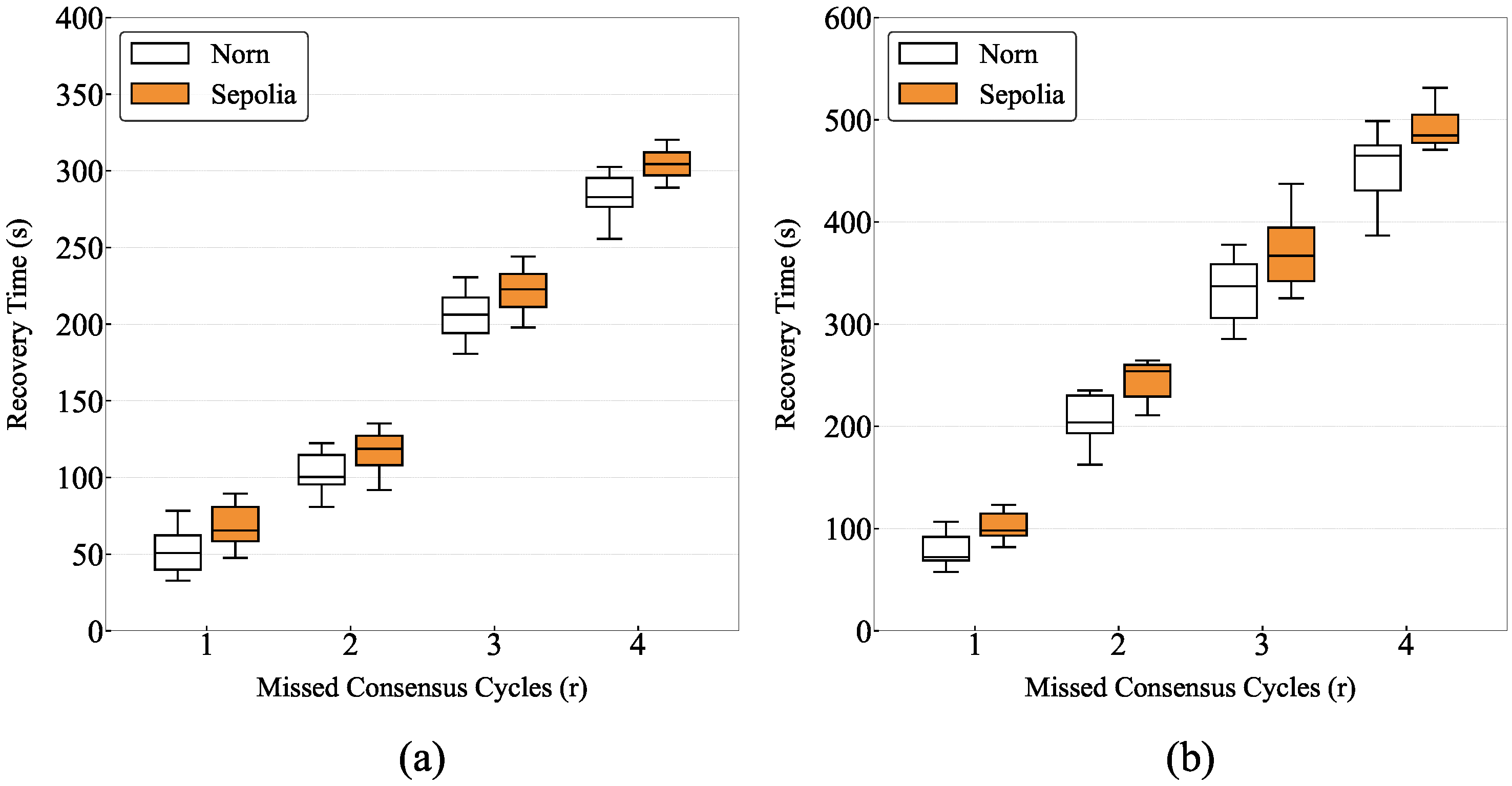

6.3. Cross-Network Adaptability

To validate the scalability of the STK scheme, we conducted experiments on both a PoVF-based private blockchain Norn and the public Sepolia testnet. The system was evaluated under two cycle configurations: 5 blocks per cycle and 10 blocks per cycle. Calibrated to align with the Sepolia testnet (with a 12– consensus cycle), the 5 blocks per cycle configuration yields a salt-update period of approximately , achieved by tuning Norn’s to match Sepolia’s block production rhythm, aiming to handle short-term outlier scenarios. The 10 blocks per cycle configuration, corresponding to , simulates prolonged disconnections.

The results in

Figure 7 demonstrate the adaptability of the STK scheme. The transition from 5 blocks per cycle to 10 blocks per cycle illustrates how the system can be adjusted for different outlier durations by modifying the key update frequency. This flexibility ensures that the STK can dynamically adapt to varying network conditions and operational needs. Whether 5 blocks per cycle or 10 blocks per cycle are chosen for the salt-update iteration period, the computational complexity remains

, ensuring no significant impact on performance or communication overhead, with the computational load staying consistent.

The comparative evaluation on the Norn and Sepolia platforms demonstrates the robustness of STK across heterogeneous infrastructures. Norn’s stable, low-latency environment ensures precise adaptive policies, while on Sepolia, STK maintains consistency under more variable conditions typical of open networks. This highlights STK’s versatility in both stable and dynamic environments.

The experiment demonstrates that STK scales across different communication intervals. The comparison between Norn’s adjustable and Sepolia’s variable block production time covers a broad range of network scenarios, from low-latency to fluctuating, high-latency rhythms. By successfully operating under both short and long cycle configurations, STK proves its security logic scales to accommodate communication variations inherent in real-world UAV deployments.

In summary, the STK scheme proves to be a highly adaptable and scalable solution for UAV swarm security. Deploying STK on platforms such as Sepolia ensures secure and continuous dynamic key management, allowing UAVs to reliably update and synchronize their keys across heterogeneous infrastructures.

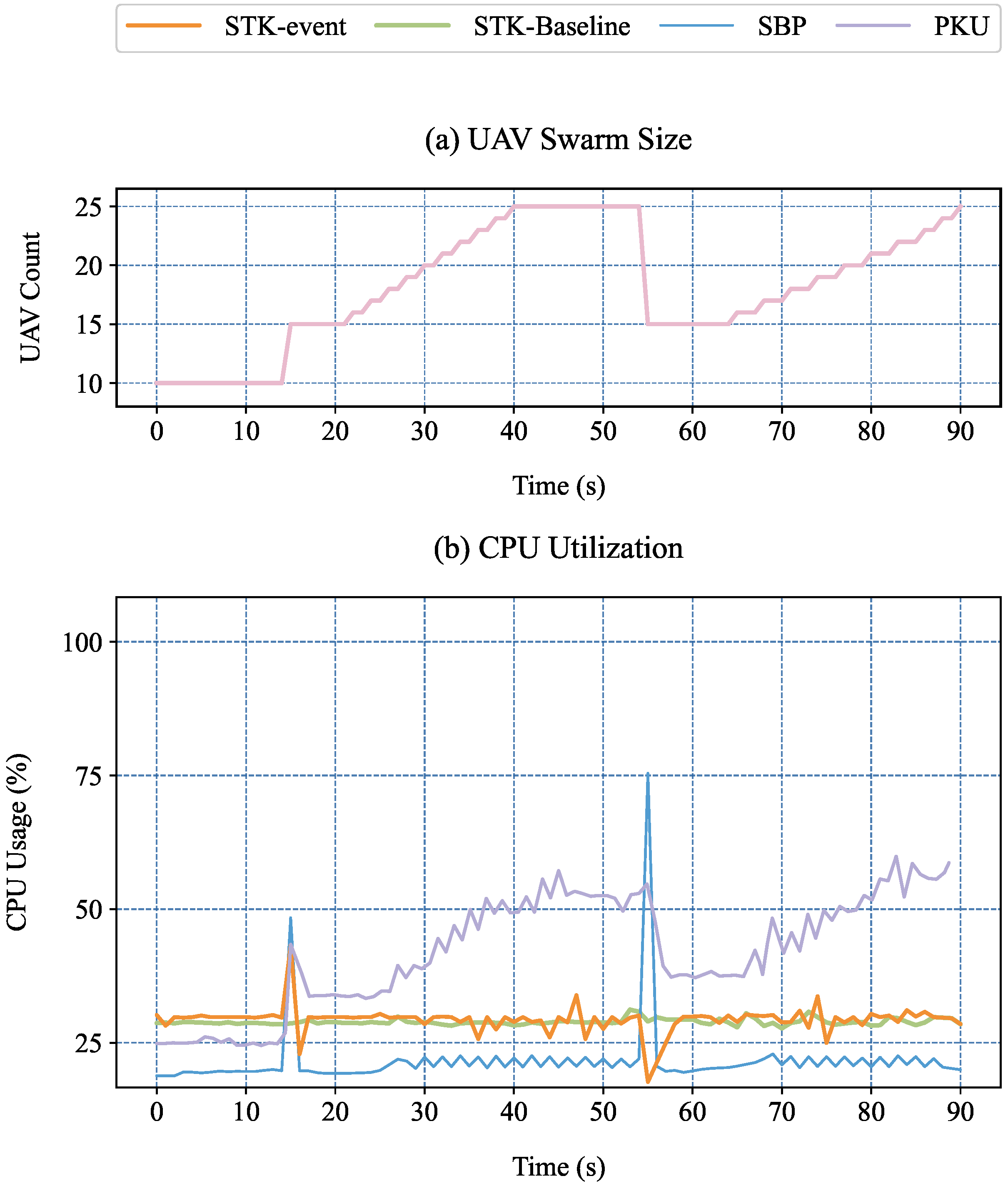

6.4. CPU Resource Utilization Analysis

We compare against SBP and its baseline PKU from [

7]. SBP is a leader-centric broadcast-key protocol that maintains a single symmetric group key and rekeys via a Diffie–Hellman chain using one-to-many broadcasting. PKU is a public key unicast baseline in which the leader maintains pairwise keys with each follower and encrypts/transmits control messages per recipient, incurring linear CPU and bandwidth load at the leader.

In our experiments, we replicate the 90-second scenario described in [

7] using CPU utilization as the sole evaluation metric. The event schedule follows

Table 3: the swarm is stable during 0–15 s; at 15 s, five UAVs join simultaneously; from 25 to 45 s, one UAV joins every 2 s; at 55 s, ten UAVs leave at once; and from 65 to 85 s, one UAV joins every 2 s. To permit a direct comparison with the leaderless STK, the simulator tracks two roles: an STK-baseline node that remains online without participating in events (to detect potential load spillover) and an STK-event node that performs join/leave actions in each phase.

Figure 8a depicts the prescribed swarm sizes, and

Figure 8b presents time series for STK (baseline and event) alongside SBP and PKU. Unlike SBP or PKU, STK does not rely on a centralized leader and therefore avoids concentrating the event load on a single node.

Over the 90 s window, the STK-baseline node remains approximately constant at 28%, with no discernible trend even during sharp membership changes. This indicates that event workload does not spill over to non-participating nodes—an effect that leader-only reporting in [

7] cannot reveal. The STK-event node exhibits short, transient increases at event boundaries during hash-chain derivation and state admission, followed by only mild variation during blockchain synchronization and a prompt return to baseline without a sustained rise.

Overall, STK confines event-related computation to the participating node and maintains a low steady-state load, while SBP/PKU concentrate work on a leader. This design avoids load concentration and reduces CPU and bandwidth overhead under dynamic membership, making STK the more efficient choice for swarm management in dynamic environments.

7. Conclusions

This paper presented Salted Temporal Key (STK), a decentralized key management scheme that addresses a persistent challenge in UAV swarms by enabling secure, non-interactive reintegration of outlier nodes. Its core innovation is leveraging the blockchain’s immutable block sequence as a temporal salt, binding the computational cost of reentry to the disconnection duration, and turning reintegration into a puzzle whose difficulty grows exponentially with the number of missed consensus cycles. Consequently, STK achieves a principled reconciliation of security and operational flexibility, a challenge for static, centralized designs.

Experimental validation, including real-world deployment on Raspberry Pi-based UAVs and large-scale swarm emulation, demonstrates robust, scalable performance with predictable reintegration latency under frequent disconnections. By adjusting the blocks-per-cycle setting and the broadcast interval (), operators can tune the security–latency trade-off, bound recovery time, and isolate nodes with excessive delays. The decentralized design eliminates the single point of failure that bottlenecks traditional systems. Beyond performance, STK simplifies deployment in IoT-enabled environments by decoupling reintegration from interactive handshakes and relying solely on a public, immutable ledger state for verification. This enables easier coordination in intermittently connected swarms and supports scaling to larger fleets and more complex missions.

Despite these strengths, the computation-bound design may introduce non-negligible latency after prolonged outages, and the current model does not distinguish between voluntary and involuntary disconnections. Future work will focus on reducing recovery time for prolonged gaps, integrating context-aware trust to differentiate benign from risky events, and exploring decentralized resource and task-sharing mechanisms to further enhance resilience. Building on the successful real-platform deployment demonstrated in this work, future efforts will include extensive closed-loop flight trials to validate the STK scheme’s performance under complex, dynamic swarm operations such as formation flying and collaborative task execution. Additionally, we will explore decentralized mechanisms to sustain continuous swarm operation during extended disruptions, thereby enhancing resilience in mission-critical environments. Overall, STK offers a time-sensitive, blockchain-driven foundation for securing scalable and efficient communication in dynamic UAV networks, paving the way for fully autonomous and resilient IoT-enabled swarm operations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z. and T.Y.; methodology, Z.Z.; software, Z.Z.; validation, Z.Z., P.W. and T.Y.; formal analysis, Z.Z.; investigation, Z.Z.; resources, Z.Z. and T.Y.; data curation, P.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z.; writing—review and editing, Z.Z. and T.Y.; visualization, Z.Z. and P.W.; supervision, T.Y.; project administration, T.Y.; funding acquisition, T.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant No. U24A20259 and the Sichuan Science and Technology Program under grant No. 2024ZHCG0044.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lian, B.; Koru, A.T.; Xue, W.; Lewis, F.L.; Davoudi, A. Distributed Dynamic Clustering and Consensus in Multiagent Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2024, 69, 6474–6481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mall, P.; Amin, R.; Das, A.K.; Leung, M.T.; Choo, K.K.R. PUF-based authentication and key agreement protocols for IoT, WSNs, and smart grids: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 8205–8228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, X. A blockchain-based access control scheme with multiple attribute authorities for secure cloud data sharing. J. Syst. Archit. 2021, 112, 101854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdinejad, A.; Parizi, R.M.; Dehghantanha, A.; Karimipour, H.; Srivastava, G.; Aledhari, M. Enabling drones in the internet of things with decentralized blockchain-based security. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 6406–6415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.F.A.; Mazhar, T.; Al Shloul, T.; Shahzad, T.; Hu, Y.C.; Mallek, F.; Hamam, H. Applications, challenges, and solutions of unmanned aerial vehicles in smart city using blockchain. Peerj Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Barke, S.; Garg, M.; Gupta, A.; Narwal, B.; Mohapatra, A.K.; Sharma, D.K.; Srivastava, G. A walkthrough of blockchain-based internet of drones architectures. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 34924–34940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Liu, T.; Lui, K.S.; Danilov, C.; Nahrstedt, K. Secure broadcast protocol for unmanned aerial vehicle swarms. In Proceedings of the 2020 29th International Conference on Computer Communications and Networks (ICCCN), Honolulu, HI, USA, 3–6 August 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.; Omote, K. An efficient blockchain-based authentication scheme with transferability. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0310094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Vijayakumar, P.; He, D.; Kumar, N.; Ma, J. Blockchain-based mutual-healing group key distribution scheme in unmanned aerial vehicles ad-hoc network. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 11309–11322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, G.; Chae, K.; Doh, I. Hierarchical blockchain-based group and group key management scheme exploiting unmanned aerial vehicles for urban computing. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 27990–28003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Gu, M.; Yang, B.; Lin, J.; Hong, H.; Kong, M. A secure trust-based key distribution with Self-Healing for internet of things. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 114060–114076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yuan, L.; Feng, Z.S.; Chen, X.; Hang, Z.C. A Lightweight Key Agreement Scheme for UAV Network. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 8th International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC), Chengdu, China, 9–12 December 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 731–735. [Google Scholar]

- Kharjana, M.; Sahana, S.C.; Saha, G. Securing Autonomous UAV Cluster with Blockchain-based Threshold Key Management System utilizing Crypto-asset and Multisignature. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2025, 24, 5765–5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Chang, Z.; Li, H.; Min, G. Basuv: A blockchain-enabled uav authentication scheme for internet of vehicles. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 19, 9055–9069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhafidh, M.; Zaghdoud, N.; Charef, N.; Mnaouer, A.B. Blockchain-Based Key Management Solution for Clustered Flying Ad-Hoc Network. In Proceedings of the 2023 Fifth International Conference on Blockchain Computing and Applications (BCCA), Kuwait, 24–26 October 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Z.; Huang, Q.; Chen, X. A fully dynamic forward-secure group signature from lattice. Cybersecurity 2022, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Ko, D.; Park, S. Block data record-based dynamic encryption key generation method for security between devices in low power wireless communication environment of IoT. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Shi, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, T.; Li, Q.; Han, Z.; Yuan, J. A location-updating based Self-Healing group key management scheme for VANETs. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2025, 24, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Yang, T.; Wang, Y.; Dong, B. PoVF: Empowering decentralized blockchain systems with verifiable function consensus. Comput. Netw. 2025, 259, 111092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Lei, H.; Bao, Z.; Lu, N.; Shi, W.; Chen, B. Verifiable Random Function Schemes Based on SM2 Digital Signature Algorithm and Its Applications for Committee Elections. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2024, 5, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biryukov, A.; Fisch, B.; Herold, G.; Khovratovich, D.; Leurent, G.; Naya-Plasencia, M.; Wesolowski, B. Cryptanalysis of algebraic verifiable delay functions. In Proceedings of the Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 18–22 August 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 457–490. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J.; Wang, T.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Q.; Liew, S.C. Biozero: An efficient and privacy-preserving decentralized biometric authentication protocol on open blockchain. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.17509. [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey, J.; Schneier, B.; Hall, C.; Wagner, D. Secure applications of low-entropy keys. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Information Security, Tatsunokuchi, Japan, 17–19 September 1997; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; pp. 121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, D.J.; Hülsing, A. Decisional second-preimage resistance: When does SPR imply PRE? In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology–ASIACRYPT 2019: 25th International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Kobe, Japan, 8–12 December 2019; Proceedings, Part III 25. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Du, W.; Atallah, M.J. Secure multi-party computation problems and their applications: A review and open problems. In Proceedings of the 2001 Workshop on New Security Paradigms, Cloudcroft, NM, USA, 10–13 September 2001; pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).