Task Planning and Optimization for Multi-Region Multi-UAV Cooperative Inspection

Highlights

- A new multi-region multi-UAV task and path planning model is proposed: the multiple traveling salesmen with neighborhoods problem (MTSPN) model, which integrates the multiple traveling salesmen problem (MTSP) with the traveling salesmen problem with neighborhoods (TSPN).

- A novel decoupled multi-region multi-UAV task and path planning framework has been designed: firstly, the KMGA algorithm—combining K-Means++ algorithm with the genetic algorithm—computes the sequence of task regions to be inspected for each UAV. Subsequently, a multi-neighborhood iterative dynamic programming (MNIDP) algorithm is proposed to solve the multi-neighborhood path planning problem for each UAV.

- This work provides a new multi-UAV task and path planning model, which is solved based on the concept of decoupling.

- The proposed KMGA-MNIDP composite planning strategy could effectively address the multi-region multi-UAV task and path planning problems.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A model addressing multi-region multi-UAV mission and path planning problems is proposed, which is decomposed into two subproblems: MTSP and MNPP (a TSPN variant targeting optimal paths to visit all neighborhoods per preset sequence). This modeling approach effectively decouples the solution process, avoiding the computational complexity associated with direct coupled solutions.

- (2)

- A K-Means++ genetic algorithm (KMGA) combining K-Means clustering with genetic algorithms is proposed. It addresses the downside of MTSPN that only focuses on the path cost (ignoring UAV collision avoidance) and the inability of existing heuristic algorithms to solve these shortcomings.

- (3)

- A multi-neighborhood iterative dynamic programming (MNIDP) algorithm based on dynamic programming principles is proposed. It achieves shorter path lengths compared to baseline methods when solving the MNPP problem.

- (4)

- A series of comparative simulations are conducted. The simulation results demonstrated that the proposed composite decoupling planning framework can effectively enhance the inspection efficiency of multi-region multi-UAV operations in transmission lines.

2. Problem Description

2.1. Description of MTSP

2.2. Description of MNPP

- (1)

- Simplicity of computation: For convex neighborhoods, it is simple to calculate the optimal path points of the UAVs. This scenario can typically be transformed into a more straightforward geometric problem rather than a complex optimization problem, which greatly reduces computational complexity.

- (2)

- Theoretical solvability: This assumption enables many classical optimization algorithms which are initially designed for the standard TSP or MTSP and could be adapted for addressing the MTSPN.

- (3)

- Easy to model: It is straightforward and intuitive to represent the neighborhoods via convex polygons such as circles, ellipses, and squares, facilitating the rapid construction of test instances and verification of algorithm performance.

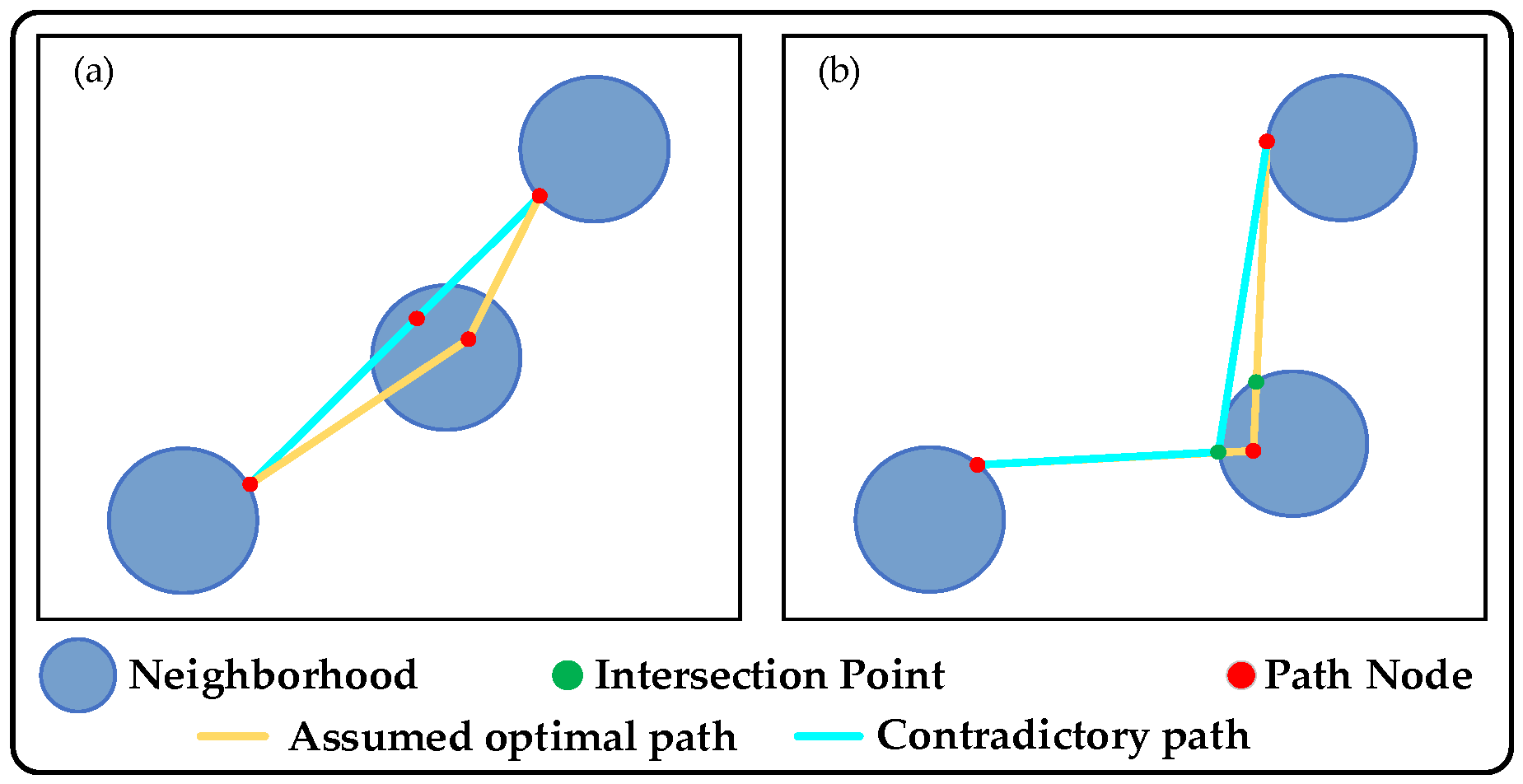

2.3. Construction of MTSPN Model

3. K-Means++ Genetic Algorithm

3.1. K-Means++ Clustering Algorithm

- (1)

- Randomly select the first centroid c1 from the dataset.

- (2)

- For each subsequent centroid ck (k = 2, …, K), the selection probability for each unselected point is computed, and the next centroid ck is then sampled proportionally to P(xi):where xi and xj are the i th and j th data points, cselected is the selected centroid, and d (xi, cselected) is the minimum distance from xi to any existing centroid.

3.2. The Implementation of Genetic Algorithm

- (1)

- Randomly select starting node i.

- (2)

- Find unvisited node j minimizing the distance:where C denotes unvisited nodes and dij is the distance between node i and node j.

- (3)

- Update current node: i←j.

- (4)

- Repeat steps 2–3 until all nodes are visited.

- (1)

- Selection Operator: The roulette wheel algorithm is employed as the selection operator, and a dynamic factor α is incorporated to prevent the algorithm from falling into the local optimal solution. The improved probability p(ci) of each chromosome that is selected is as follows:

- (2)

- Crossover Operator: The partially matched crossover method.

- (3)

- Mutation Operator: The bit flip operation. In order to reduce the mutation probability of high-quality chromosomes and increase the probability of the low-quality chromosomes, this paper employs the adaptive mutation probability pm proposed in previous research:where pm0 is the basic mutation probability, f is a simplified expression of f(ci), and fmax, fmin, and favg are the maximum, the minimum, and average values of the fitness of the chromosomes in the population, respectively.

| Algorithm 1 A K-Means++ Genetic Algorithm for solving MTSP |

| 1: Input: the locations of n cities: data, the number of salesmen: m, the UAV parking place: origin |

| 2: procedure K-Means++ Cluster (data, n) |

| 3: center1 = random (data) 4: initialize rest m − 1 center |

| 5: repeat |

| 6: assign center for ci and gain cluster cli |

| 7: centeri = mean (data(ci)) for cli |

| 8: end repeat until maximum iterations |

| 9: end procedure |

| 10: for cli |

| 11: select the start point |

| 13: procedure GA (data(cli)) |

| 14: initialize population |

| 15: repeat |

| 16: calculate fitness of each chromosome |

| 17: selection, crossover and mutation |

| 18: end repeat until maximum iterations |

| 19: end procedure |

| 20: Output: solution of MTSP |

4. Multi-Neighborhoods Iterative Dynamic Programming

4.1. Dynamic Programming for MNPP

- (1)

- State Definition: The state dp(i, k) represents the optimal cost (or key metric) for the path from the starting neighborhood i to neighborhood k.

- (2)

- State Transition Equation: The equation dp(i, k) = min{dp(i, k) + cost(j, k)} (or a variant thereof) systematically builds the solution for larger paths by combining the solutions of smaller overlapping sub-paths.

- (3)

- Initialization: The base cases are defined, such as dp(i, k) = 0, for the path from any neighborhood to itself.

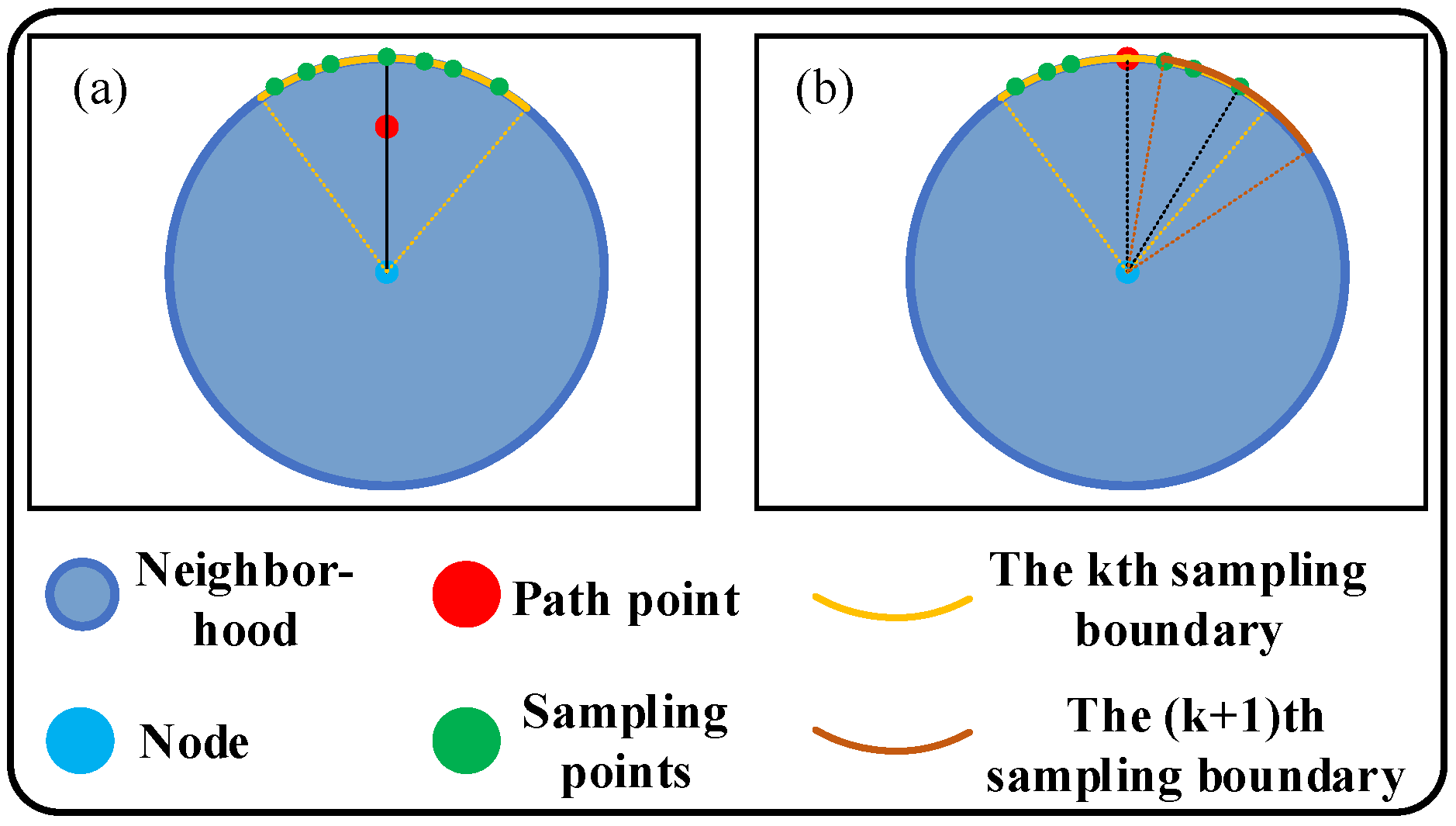

4.2. Multi-Neighborhood Iterative Dynamic Programming

| Algorithm 2 Multi-Neighborhood Iterative Dynamic Programming Algorithm for Solving MNPP |

| 1: Input: the locations of a nodes with known node order: loc, the radius of the region: r, the maximum iterations: itemax |

| 2: procedure iterative dynamic programming |

| 3: initialize the path node pi(0) of each neighborhood Ni |

| 4: discretize the neighborhoods and gain |

| 5: for i = 1: a do |

| 6: if the connection between pi−1 and pi+1 crosses Ni |

| 7: pi(0) = midpoint of the in-neighborhood part of the connection |

| 8: end if |

| 9: |

| 10: end for |

| 11: while the iteration number k < itemax do |

| 12: for i = 1: a do |

| 13: if the connection between pi−1 and pi+1 crosses Ni |

| 14: pi(k+1) = midpoint of the in-neighborhood part of the connection |

| 15: end if |

| 16: sample the area of a specified size around pi and obtain a set of sampling points ; then add pi(k) to |

| 17: |

| 18: end for |

| 19: end while |

| 20: end procedure |

| 21: Output: solution of MNPP |

5. Results of the Simulations

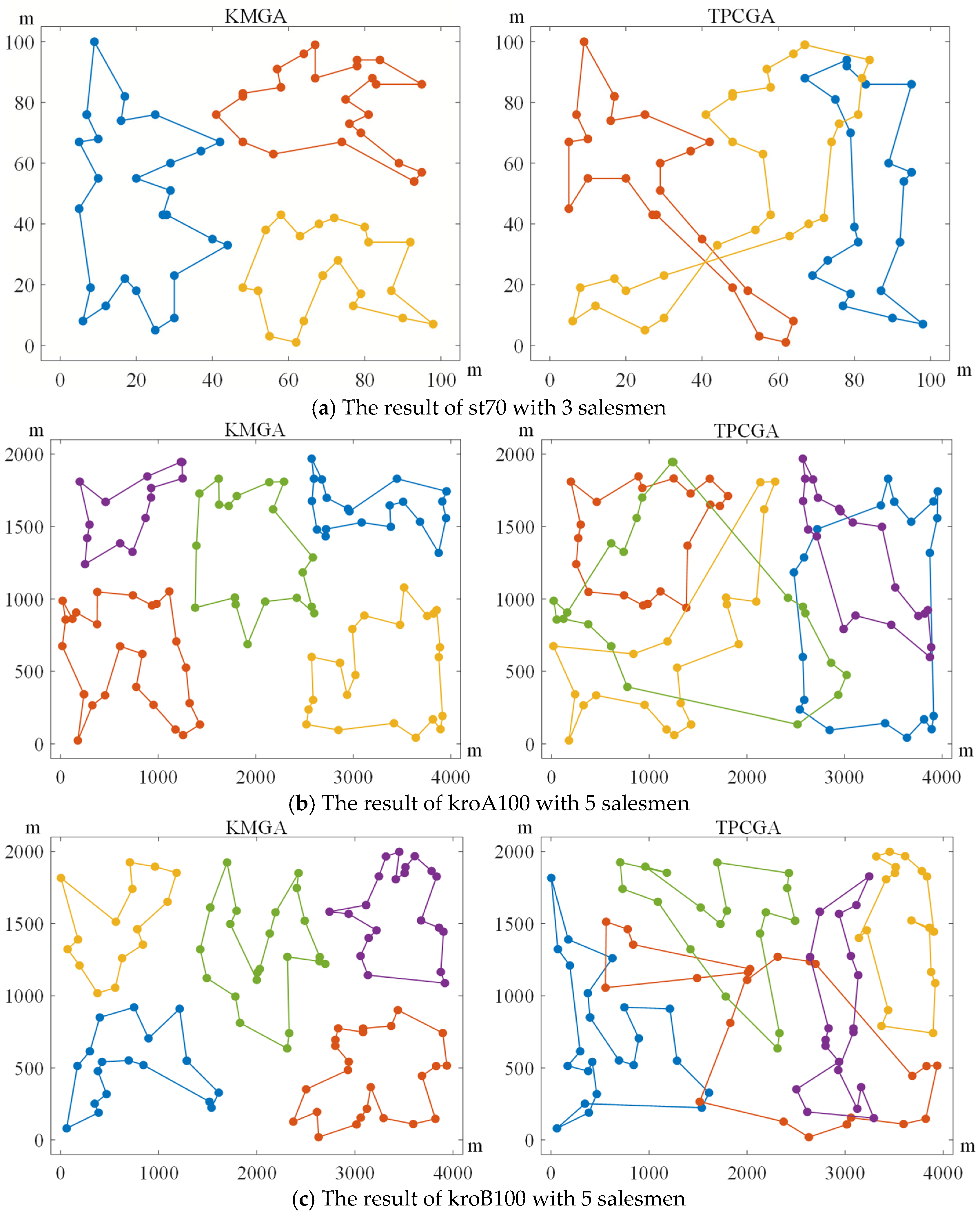

5.1. The Comparative Simulations of the MTSP

5.2. The Simluations of the MNPP

5.2.1. The MNPP Simulations with Different Neighborhood Radius Values

5.2.2. The Comparative Simulations of the MNPP

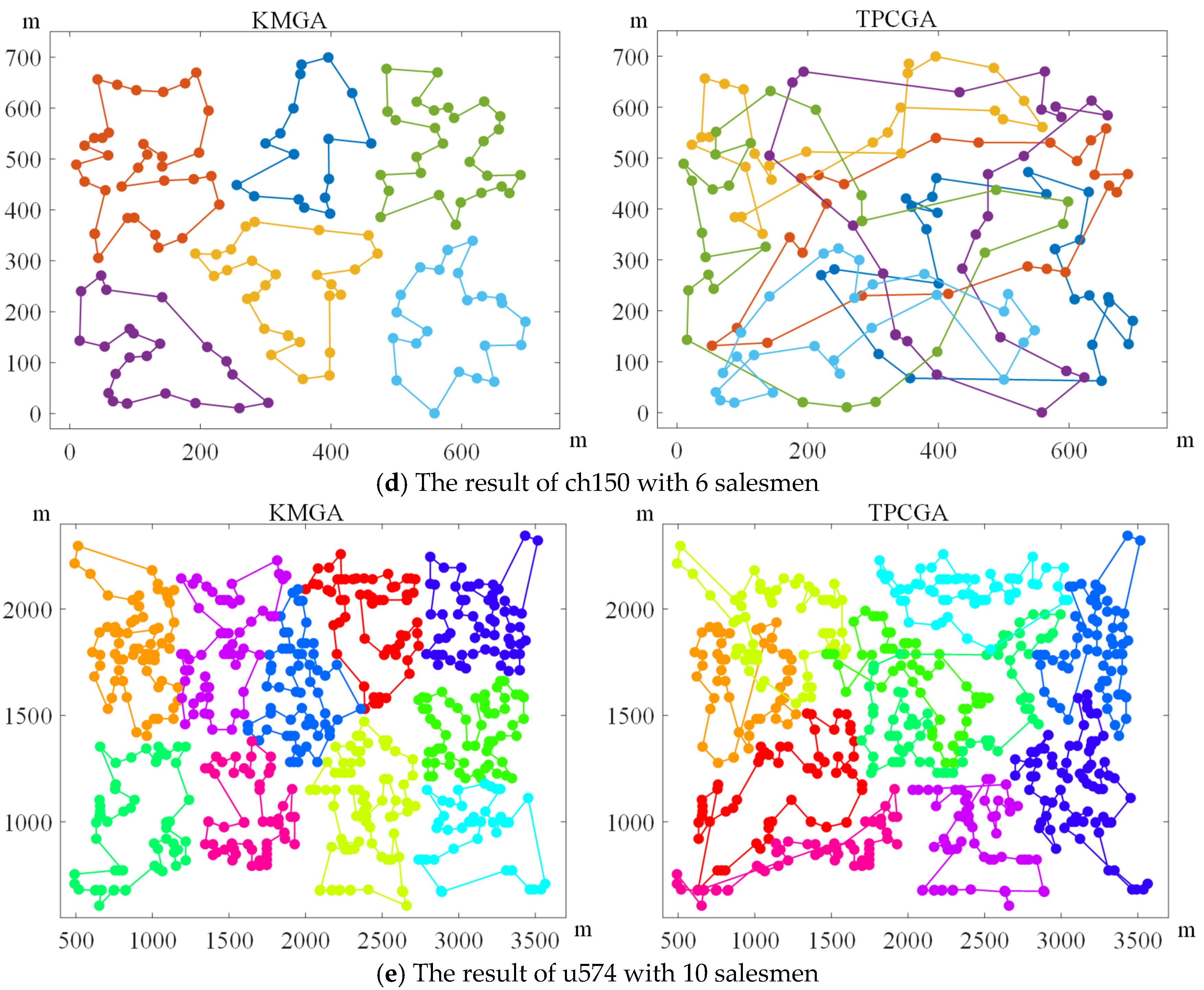

5.3. The Comparative Simulations of the MTSPN

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The swarm of UAVs sometimes comprise heterogeneous UAVs and the task allocation for such swarms must incorporate this heterogeneity as a consideration to ensure feasible mission execution. However, the homogeneity assumption of the MTSPN fails to accommodate this scenario. Therefore, efficiently solving the unbalanced and dynamic cooperative assignment between multiple UAVs and multiple regions is a challenge that needs further exploration [33].

- (2)

- The improvements of the KMGA will be made by optimizing the K-Means++ clustering criteria and introducing load balancing constraints into the clustering objective function. This approach achieves the goal of ensuring that the task loads among drones are essentially equal.

- (3)

- The KMGA and MNIDP algorithm proposed in this paper will be deployed on physical UAVs, and the effectiveness and performance of the algorithms will be demonstrated through physical experiments.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, C.; Liu, J.; Shen, X.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Leon, J.I. Multi-Objective Energy Management Strategy for Distribution Network With Distributed Renewable Based on Learning-Driven Model Predictive Control. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2025, 16, 4968–4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Liu, G.; Liu, J.; Gao, Y.; Leon, J.I. Fixed-Time Sliding Mode Control for NPC Converters With Improved Disturbance Rejection Performance. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 4476–4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, G.; Zhang, J.; Leon, J.I.; Wu, L.; Franquelo, L.G. Finite-Time Sliding Mode Control for NPC Converters With Enhanced Disturbance Compensation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2025, 72, 1822–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakirci, M. Enhancing air pollution mapping with autonomous UAV networks for extended coverage and consistency. Atmos. Res. 2024, 306, 107480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Guo, X. Prescribed-Time Cooperative Guidance Law for Multi-UAV with Intermittent Communication. Drones 2024, 8, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Ouyang, H.; Huang, W.; Li, S.; Zhang, C.; Ding, W.; Zhan, Z. An adaptive heuristic algorithm with a collaborative search framework for multi-UAV inspection planning. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 174, 112969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusell, R.A. Technical Note—An Effective Heuristic for the M-Tour Traveling Salesman Problem with Some Side Conditions. Oper. Res. 1977, 25, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatout, M.S.; Rezoug, A.; Rezoug, A.; Baizid, K.; Iqbal, J. Optimisation of fuzzy logic quadrotor attitude controller—Particle swarm, cuckoo search and BAT algorithms. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2021, 53, 883–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Wang, D. An Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm for Multiple Travelling Salesman Problem. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Innovative Computing, Information and Control-Volume I (ICICIC’06), Beijing, China, 30 August–1 September 2006; pp. 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, A.E.; Ragsdale, C.T. A new approach to solving the multiple traveling salesperson problem using genetic algorithms. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 175, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, X.; Dong, Y.; Xie, J.; Xie, G.; Xu, X. A novel state transition simulated annealing algorithm for the multiple traveling salesmen problem. J. Supercomput. 2021, 77, 11827–11852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jia, Z.; Ai, X.; Yang, D.; Yu, J. A modified two-part wolf pack search algorithm for the multiple traveling salesmen problem. Appl. Soft Comput. 2017, 61, 714–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Lu, H.; Xiang, L.; Shen, Q. Fuzzy C-means Clustering Based Partheno-genetic Algorithm for Solving MMTSP. Comput. Sci. 2020, 47, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modares, A.; Somhom, S.; Enkawa, T. A self-organizing neural network approach for multiple traveling salesman and vehicle routing problems. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 1999, 6, 591–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Yi, Z.; Tang, H. A columnar competitive model for solving multi-traveling salesman problem. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2007, 31, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacholder, E.; Han, J.; Mann, R.C. A neural network algorithm for the multiple traveling salesmen problem. Biol. Cybern. 1989, 61, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.; Tsai, M.; Chen, W. A study of feature-mapped approach to the multiple travelling salesmen problem. IEEE Int. Symp. Circuits Syst. 1991, 3, 1589–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, S.; Xydeas, C.; Mahmood, A.; Ahmed, S.; Ratyal, N.I.; Iqbal, J. Efficient optimization techniques for resource allocation in UAVs mission framework. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sun, C.; Shao, X.; Zhao, W. A descent method for the Dubins traveling salesman problem with neighborhoods. Front. Inf. Technol. Electron. Eng. 2021, 22, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Lin, Z.; Huang, W.; Yan, B. Technical development and future prospects of cooperative terminal guidance based on knowledge graph analysis: A review. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A 2025, 26, 605–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentilini, I.; Margot, F.; Shimada, K. The travelling salesman problem with neighbourhoods: MINLP solution. Optim. Methods Softw. 2013, 28, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicencio, K.; Davis, B.; Gentilini, I. Multi-goal path planning based on the generalized Traveling Salesman Problem with neighborhoods. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Chicago, IL, USA, 14–18 September 2014; pp. 2985–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckerová, J.; Váňa, P.; Faigl, J. Combinatorial lower bounds for the Generalized Traveling Salesman Problem with Neighborhoods. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 258, 125185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, B.; Chen, J.; Xu, D.; Chen, Y. Hybrid encoding based differential evolution algorithms for Dubins traveling salesman problem with neighborhood. Control. Theory Appl. 2014, 31, 941–954. [Google Scholar]

- Obermeyer, K. Path planning for a UAV performing reconnaissance of static ground targets in terrain. In Proceedings of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, Chigaco, IL, USA, 10–13 August 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermeyer, K.; Oberlin, P.; Darbha, S. Sampling-based roadmap methods for a visual reconnaissance UAV*. In Proceedings of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2–5 August 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Hung, J.Y. Optimal path planning for an autonomous robot-trailer system. In Proceedings of the IECON 2012-38th Annual Conference on IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Montreal, QC, Canada, 25–28 October 2012; pp. 2762–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Wei, N.; Walteros, J.L. An Exact Approach for Solving Pickup-and-Delivery Traveling Salesman Problems with Neighborhoods. Transp. Sci. 2023, 57, 1560–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A. A Submodular Optimization Approach to the Metric Traveling Salesman Problem with Neighborhoods. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 58th Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Nice, France, 11–13 December 2019; pp. 3383–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathinam, S.; Sengupta, R.; Darbha, S. A Resource Allocation Algorithm for Multivehicle Systems with Nonholonomic Constraints. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2007, 4, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerto, J.; Valverde, C. The Hampered Travelling Salesman problem with Neighborhoods. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 188, 109889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, B. Combining Max pooling-Laplacian theory and k-means clustering for novel camouflage pattern design. Front. Neurorobot. 2022, 16, 1041101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lv, M.; Ru, L.; Lu, B.; Hu, S.; Chang, X. Multi-UAV Unbalanced Targets Coordinated Dynamic Task Allocation in Phases. Aerospace 2022, 9, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hyperparameters | Value |

|---|---|

| population size | 80 |

| crossover rate | 0.8 |

| mutation rate | 0.1 |

| number of generations | 500 |

| Instances | Algorithms | Avg Minimum Distance Between Paths/(m) |

|---|---|---|

| st70 | TPCGA | 0.0000 |

| proposed KMGA | 4.7361 | |

| kroA100 | TPCGA | 0.0000 |

| proposed KMGA | 176.0775 | |

| kroB100 | TPCGA | 0.0000 |

| proposed KMGA | 169.2482 | |

| ch150 | TPCGA | 0.0000 |

| proposed KMGA | 34.2482 | |

| u574 | TPCGA | 0.0000 |

| proposed KMGA | 25.3728 |

| Instances | Algorithms | Avg Length/(m) | Std of Length/(m) | Avg Time/(s) | Std of Time/(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| st70 | TPCGA | 782.4375 | 50.9492 | 5.0385 | 0.0414 |

| proposed KMGA | 704.6701 | 1.9412 | 4.6021 | 0.3582 | |

| kroA100 | TPCGA | 31,951.8122 | 2234.0800 | 6.9428 | 0.2599 |

| proposed KMGA | 22,596.9524 | 29.8465 | 6.7638 | 0.5185 | |

| kroB100 | TPCGA | 31,698.9087 | 2478.1988 | 6.9603 | 0.2139 |

| proposed KMGA | 23,411.2550 | 47.4002 | 6.6826 | 0.3617 | |

| ch150 | TPCGA | 12,007.4536 | 572.2721 | 9.8412 | 0.3986 |

| proposed KMGA | 6990.8464 | 23.7484 | 9.5706 | 0.6076 | |

| u574 | TPCGA | 44,886.1364 | 210.5891 | 49.2606 | 5.0860 |

| proposed KMGA | 40,664.4786 | 211.9389 | 48.5646 | 3.1721 |

| Instances | Levene Stat of Length | p Value of Length | Levene Stat of Time | p Value of Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| st70 | 52.9823 | 0.0000 | 23.6946 | 0.0000 |

| kroA100 | 37.7687 | 0.0000 | 6.1574 | 0.0176 |

| kroB100 | 35.6870 | 0.0000 | 6.2327 | 0.0170 |

| ch150 | 29.5864 | 0.0000 | 0.2653 | 0.6095 |

| u574 | 0.1127 | 0.7389 | 6.0579 | 0.0185 |

| Instances | t Stat of Length | p Value of Length | t Stat of Time | p Value of Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| st70 | −7.4650 | 0.0000 | −5.9303 | 0.0000 |

| kroA100 | −18.2506 | 0.0000 | −1.3454 | 0.1893 |

| kroB100 | −14.5745 | 0.0000 | −2.8801 | 0.0072 |

| ch150 | −38.1778 | 0.0000 | −1.6230 | 0.1129 |

| u574 | −61.5910 | 0.0000 | −0.5062 | 0.6162 |

| Instances | Radius/(m) | Avg Length/(m) | Std of Length/(m) | Avg Time/(s) | Std of Time/(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 neighborhoods | 4.0 | 610.9333 | 0.0743 | 6.8520 | 0.0868 |

| 5.5 | 567.8601 | 0.1397 | 6.2867 | 0.0743 | |

| 7.0 | 533.2458 | 0.1316 | 5.4650 | 0.1126 | |

| 8.0 | 514.9898 | 0.3989 | 4.7537 | 0.1416 | |

| 70 neighborhoods | 4.0 | 1270.3026 | 0.1187 | 11.6093 | 0.0836 |

| 5.5 | 1190.1203 | 0.2427 | 10.2489 | 0.2192 | |

| 7.0 | 1120.8434 | 0.2144 | 9.6732 | 0.2013 | |

| 8.0 | 1080.9589 | 0.2503 | 8.7461 | 0.0784 |

| Instances | Levene Stat of Length | p Value of Length | Levene Stat of Time | p Value of Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 neighborhoods | 1.4234 | 0.2456 | 0.5804 | 0.6303 |

| 70 neighborhoods | 1.9191 | 0.1369 | 3.8043 | 0.0149 |

| Instances | f Stat of Length | p Value of Length | f Stat of Time | p Value of Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 neighborhoods | 496,124.8202 | 0.0000 | 1037.7262 | 0.0000 |

| 70 neighborhoods | 2,130,763.2091 | 0.0000 | 2805.3236 | 0.0000 |

| Instances | Approaches | Average Path Length/(m) | Standard Deviation of Path Length/(m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 neighborhoods | Node-Connection | 571.7623 | 4.3812 |

| RGA | 556.5171 | 6.2885 | |

| Proposed MNIDP | 429.0575 | 2.9024 | |

| 60 neighborhoods | Node-Connection | 1196.5320 | 13.9907 |

| RGA | 1178.2461 | 14.4318 | |

| Proposed MNIDP | 931.0527 | 15.7290 | |

| 90 neighborhoods | Node-Connection | 1892.9093 | 15.3603 |

| RGA | 1880.4838 | 19.6851 | |

| Proposed MNIDP | 1537.5530 | 17.8415 |

| Instances | Levene Stat | p Value of Levene | f Stat | p Value of ANOVA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 neighborhoods | 5.7546 | 0.0053 | 8319.7989 | 0.0000 |

| 60 neighborhoods | 0.1951 | 0.8233 | 1923.8444 | 0.0000 |

| 90 neighborhoods | 0.4061 | 0.6682 | 2461.6840 | 0.0000 |

| Instances | Approaches | Average Path Length/(m) | Standard Deviation of Path Length/(m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 70 neighborhoods | Node-Connection | 3749.1103 | 0.3126 |

| RGA | 3687.4058 | 11.8996 | |

| Proposed MNIDP | 3449.0536 | 4.7858 | |

| 100 neighborhoods | Node-Connection | 4453.0670 | 20.9587 |

| RGA | 4376.8528 | 28.1452 | |

| Proposed MNIDP | 3989.5648 | 22.4328 | |

| 150 neighborhoods | Node-Connection | 5594.3614 | 19.4487 |

| RGA | 5512.0835 | 17.2291 | |

| Proposed MNIDP | 4956.2008 | 21.5898 |

| Instances | Levene Stat | p Value of Levene | f Stat | p Value of ANOVA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70 neighborhoods | 8.3543 | 0.0007 | 36,474.7105 | 0.0000 |

| 100 neighborhoods | 0.3862 | 0.6814 | 2029.8185 | 0.0000 |

| 150 neighborhoods | 0.8182 | 0.8182 | 6018.7891 | 0.0000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiong, Y.; Tian, H.; Tang, J.; Jin, J.; Shen, X. Task Planning and Optimization for Multi-Region Multi-UAV Cooperative Inspection. Drones 2025, 9, 762. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9110762

Xiong Y, Tian H, Tang J, Jin J, Shen X. Task Planning and Optimization for Multi-Region Multi-UAV Cooperative Inspection. Drones. 2025; 9(11):762. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9110762

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiong, Yangyilei, Haoyu Tian, Jianing Tang, Jie Jin, and Xiaoning Shen. 2025. "Task Planning and Optimization for Multi-Region Multi-UAV Cooperative Inspection" Drones 9, no. 11: 762. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9110762

APA StyleXiong, Y., Tian, H., Tang, J., Jin, J., & Shen, X. (2025). Task Planning and Optimization for Multi-Region Multi-UAV Cooperative Inspection. Drones, 9(11), 762. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9110762