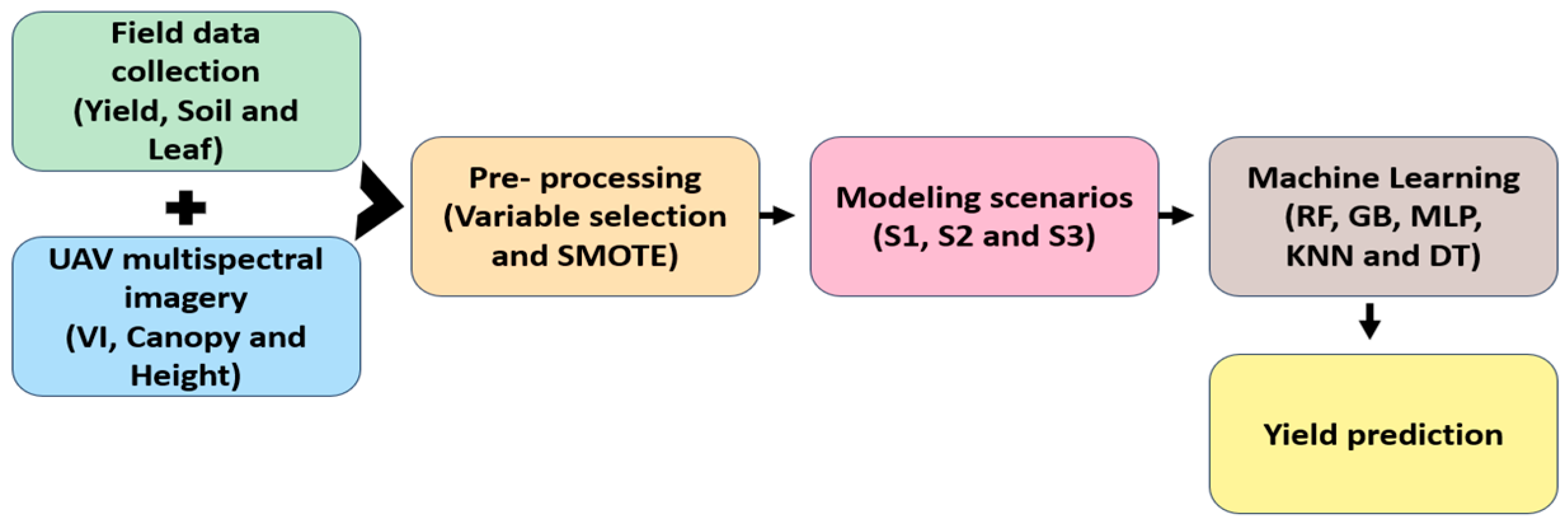

Integration of Field Data and UAV Imagery for Coffee Yield Modeling Using Machine Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

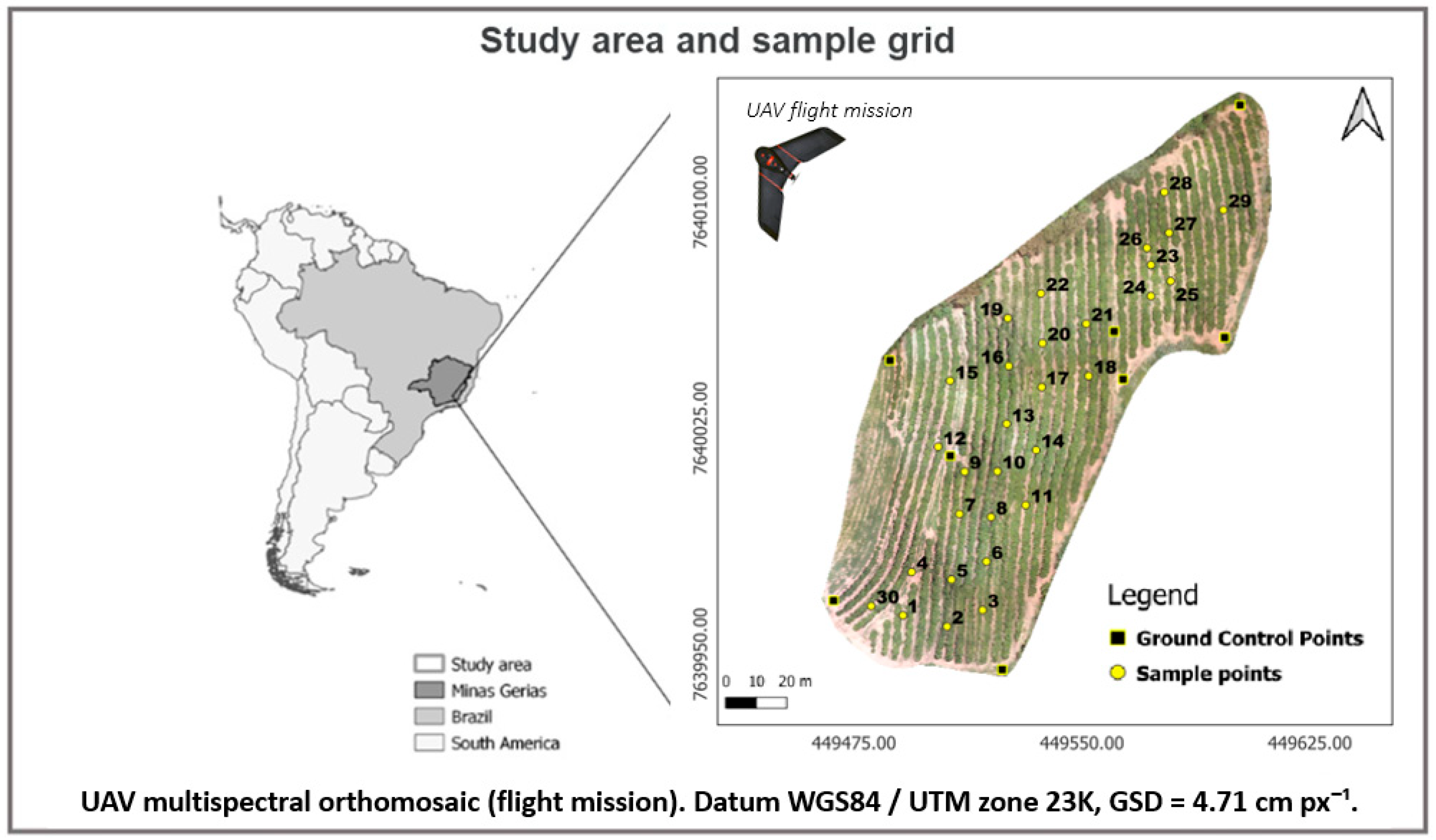

2.1. Characterization of the Study Area, Grid, and Sampling

2.2. Yield

2.3. Soil Moisture

- 2020/2021 season: August 2020 (dry period) and January 2021 (wet period);

- 2021/2022 season: August 2021 (dry period) and January 2022 (wet period).

- = mass of the wet soil sample (g)

- = mass of the dry soil sample (g)

2.4. Water Potential

2.5. Soil Fertility and Leaf Nutrition Analysis

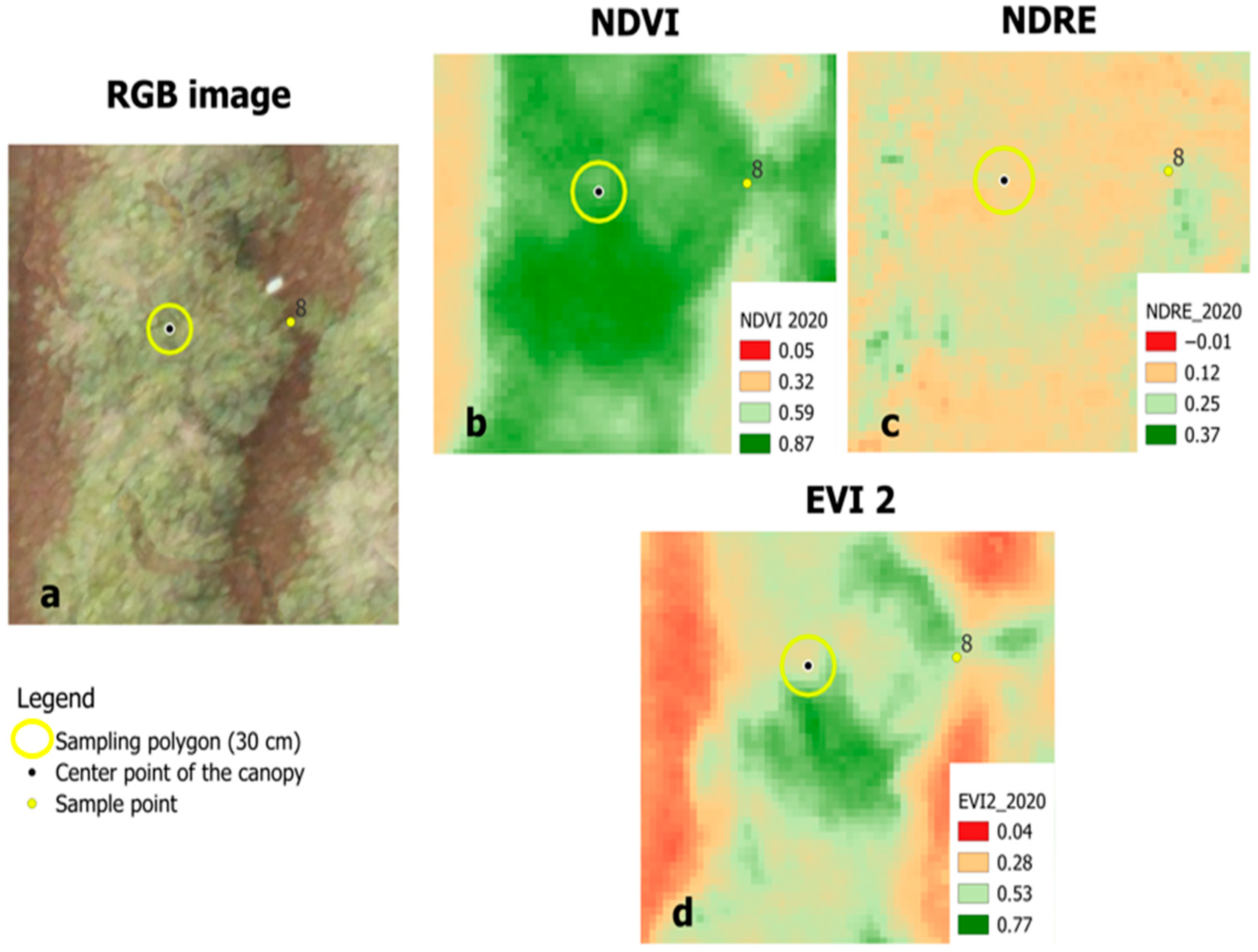

2.6. High Resolution Imagery

- Focal length: 3.98 mm;

- Vertical overlap: 70%;

- Horizontal overlap: 70%;

- Flight altitude: 50 m;

- Ground sampling distance (GSD): 4.71 cm px−1;

- Speed: 12 m/s;

- Estimated flight time: 10 min.

- Green (550 nm ± 40 nm);

- Red (660 nm ± 40 nm);

- RedEdge (735 nm ± 10 nm);

- Near-infrared–NIR (790 nm ± 40 nm);

- RGB (visible band–420–700 nm).

2.6.1. Vegetation Index

2.6.2. Plant Height, Canopy Diameter, and Leaf Area Index of Coffee Plants

- Hi: plant height estimated at sampling point i (m)

- DSM (xi, yi): value of the Digital Surface Model at pixel (xi, yi) (m)

- DTM (xi, yi): value of the Digital Terrain Model at the same pixel (xi, yi) (m)

2.7. Feature Selection

- R = correlation coefficient;

- = values of the independent variables (soil moisture, leaf water potential, soil fertility, leaf nutrient and spectral variables);

- = mean of the independent variables;

- = values of the dependent variable (coffee yield);

- = mean of the dependent variable.

- R = 1 → perfect positive correlation (both variables increase together);

- R > 0 → positive correlation (high values of X tend to be associated with high values of Y);

- R = 0 → no linear correlation (no clear linear relationship between the variables);

- R < 0 → negative correlation (as one variable increases, the other tends to decrease);

- R = −1 → perfect negative correlation (a perfect inverse linear relationship).

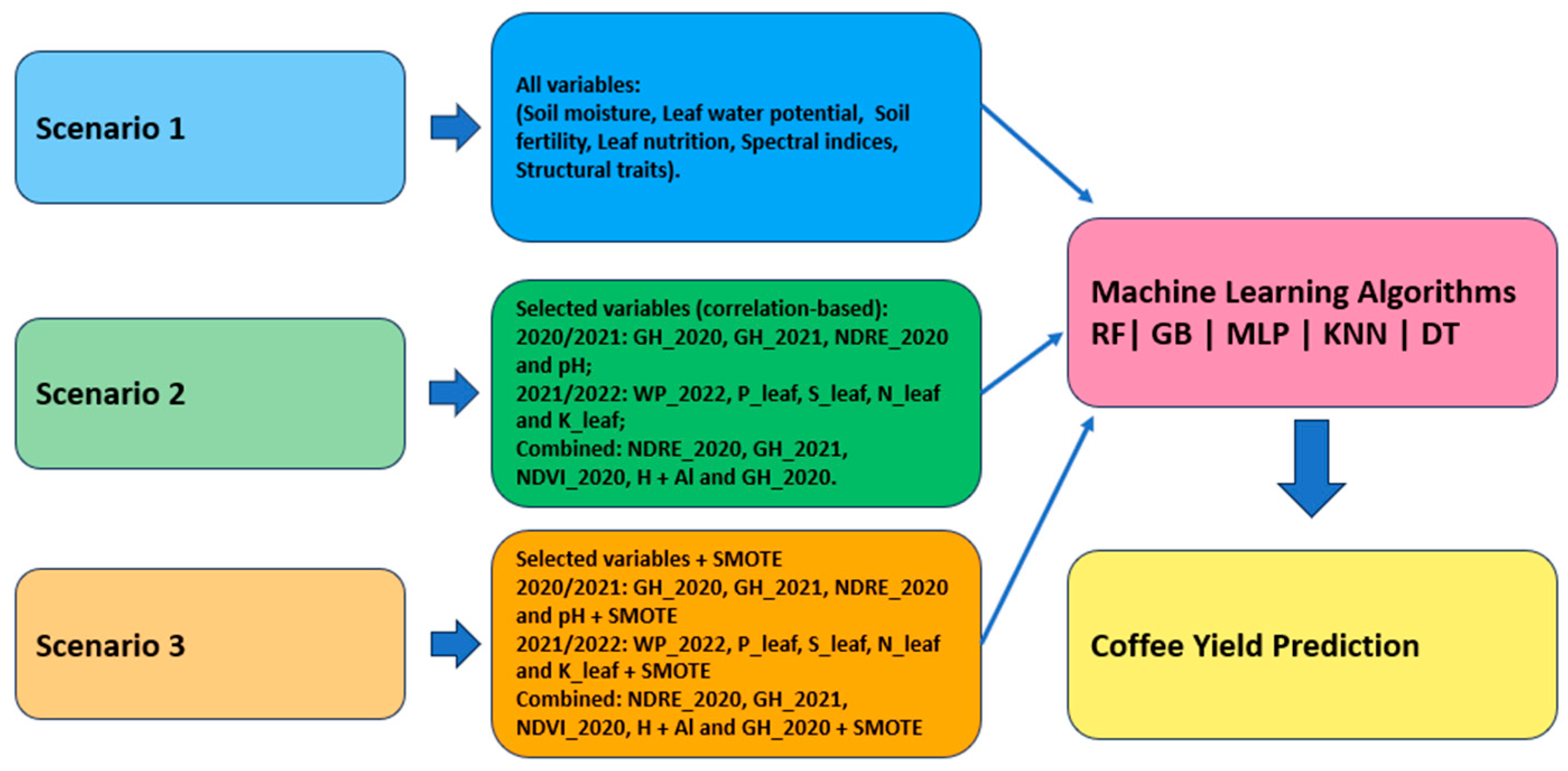

- -

- Dependent variable: yield;

- -

- Independent variables: Soil moisture: GH_2020, GH_2021, Leaf water potential (WP_2021, WP_2022), Soil fertility attributes (pH, P, K, Ca, Mg, MO, H + Al), Leaf nutrition 2021/2022 (N, P, K, Ca, Mg, S, Mn, Zn, B, Cu, Fe), Spectral vegetation indices (NDVI, NDRE, EVI2), Plant height, canopy diameter, leaf area index (LAI);

- -

- Dependent variable: yield;

- -

- Independent variables: For the 2020/2021 season (GH_2020, GH_2021, NDRE_2020, pH), for the 2021/2022 season (WP_2022, P_foliar, S_foliar, N_foliar, K_foliar), for the combined seasons (GH_2020, GH_2021, NDVI_2020, NDRE_2020, H + Al);

- -

- Dependent variable: yield;

- -

- Independent variables: same as those used in Scenario 2, but with the dataset artificially expanded using the SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) method. This approach tripled the number of samples in the dataset to improve model training and reduce overfitting caused by the limited original sample size.

2.8. Validation Prediction Models

2.9. Statistical Analysis of Model Performance

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistic

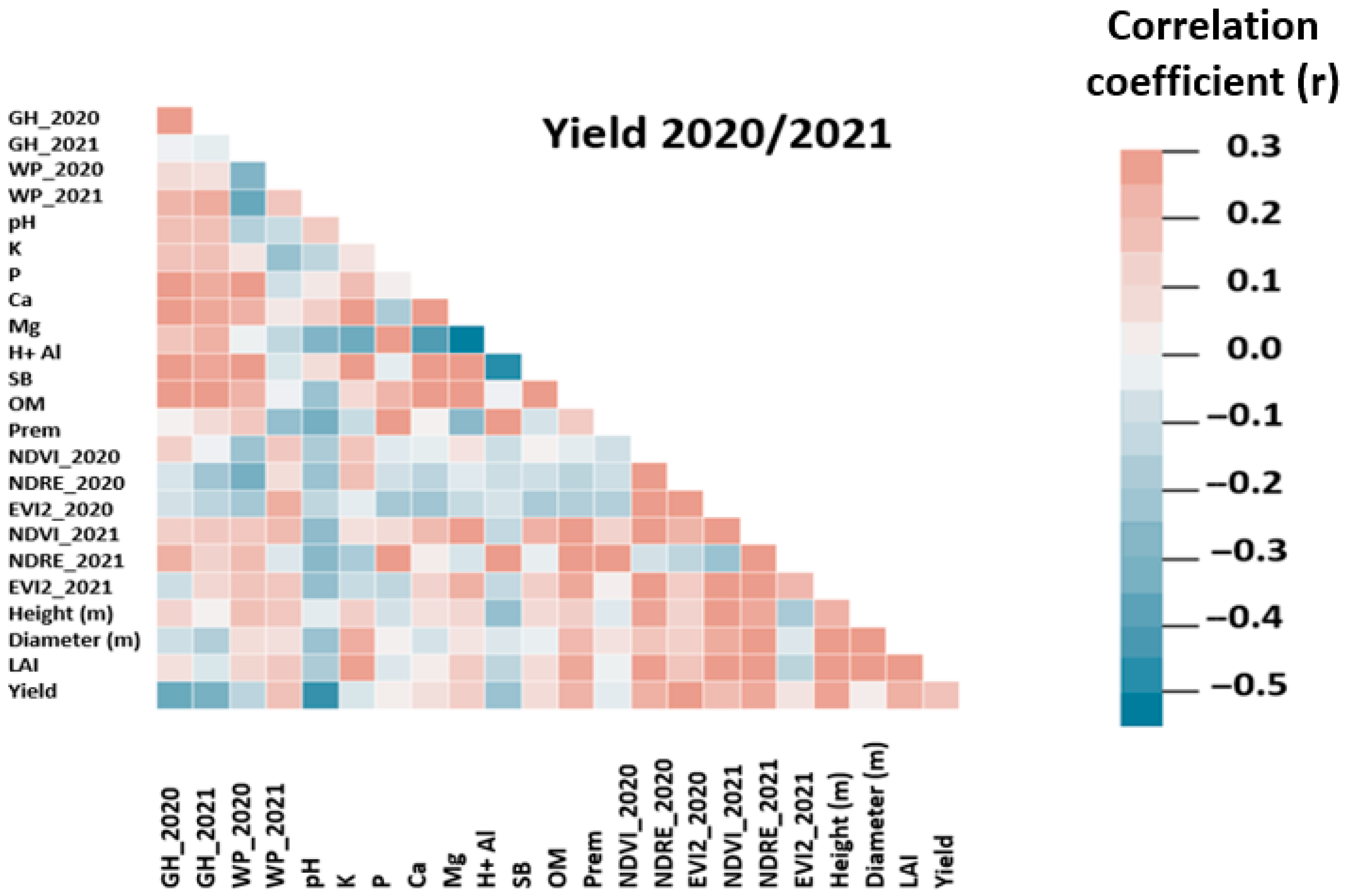

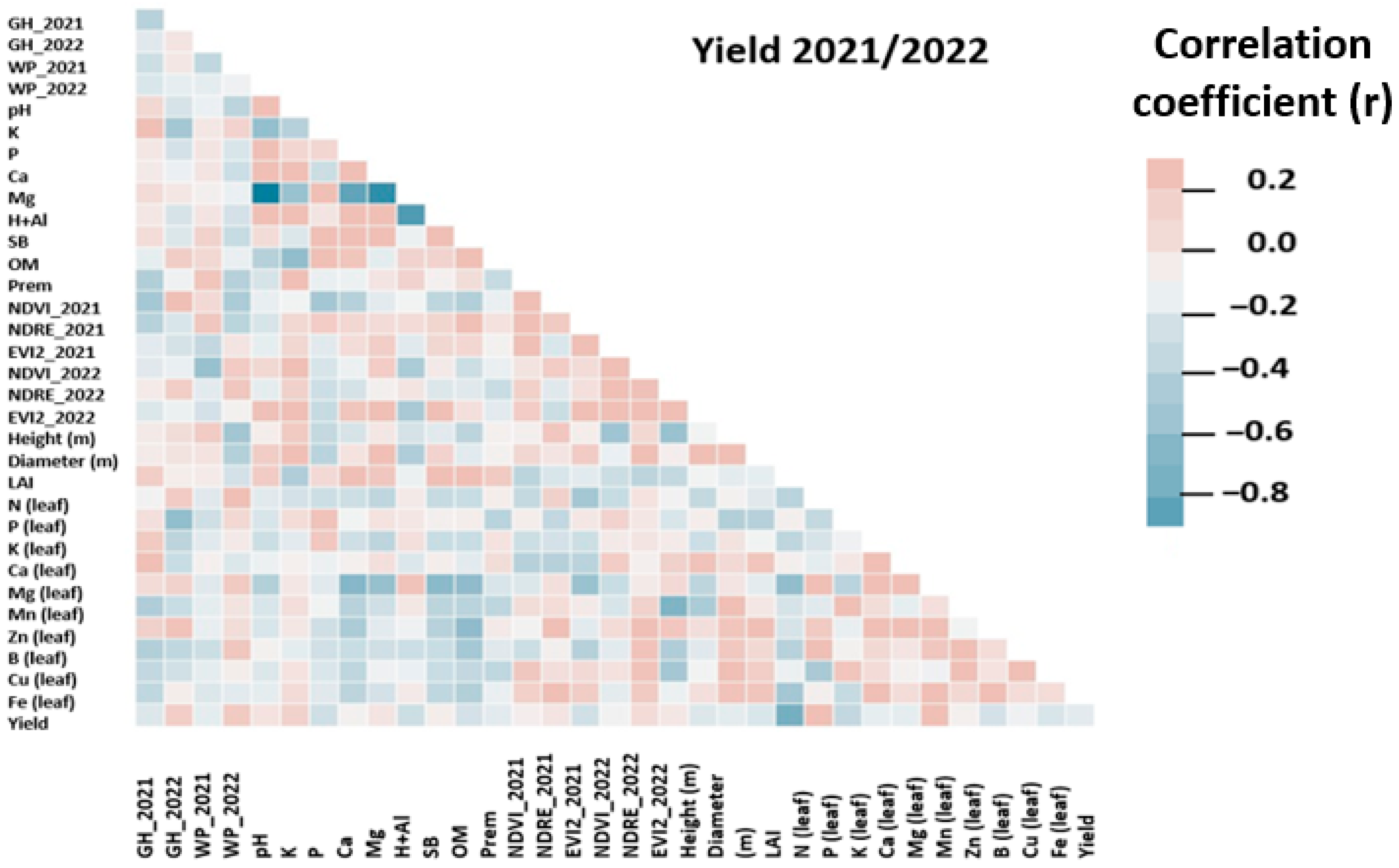

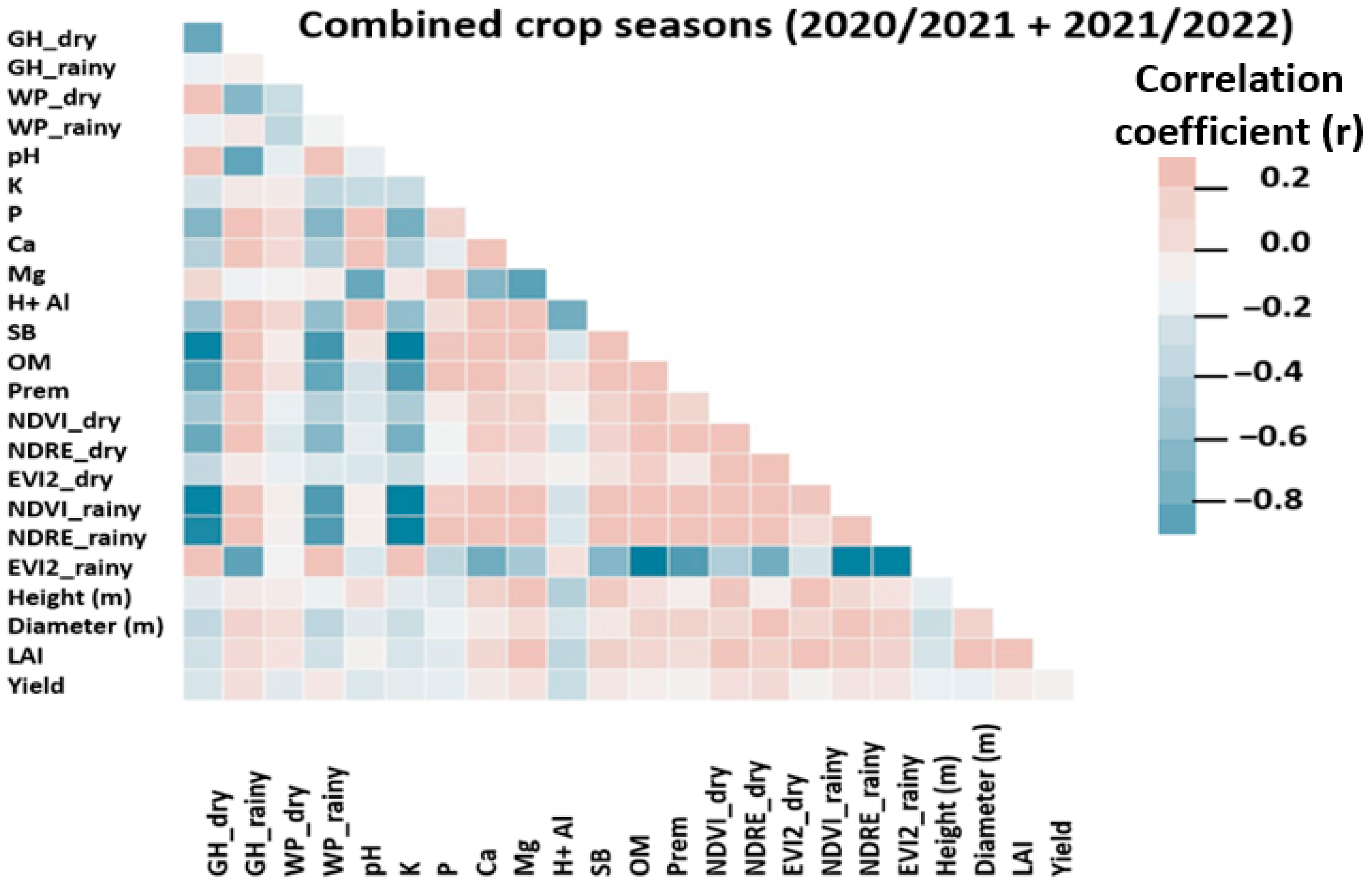

3.2. Correlation Analysis

3.3. Prediction Models

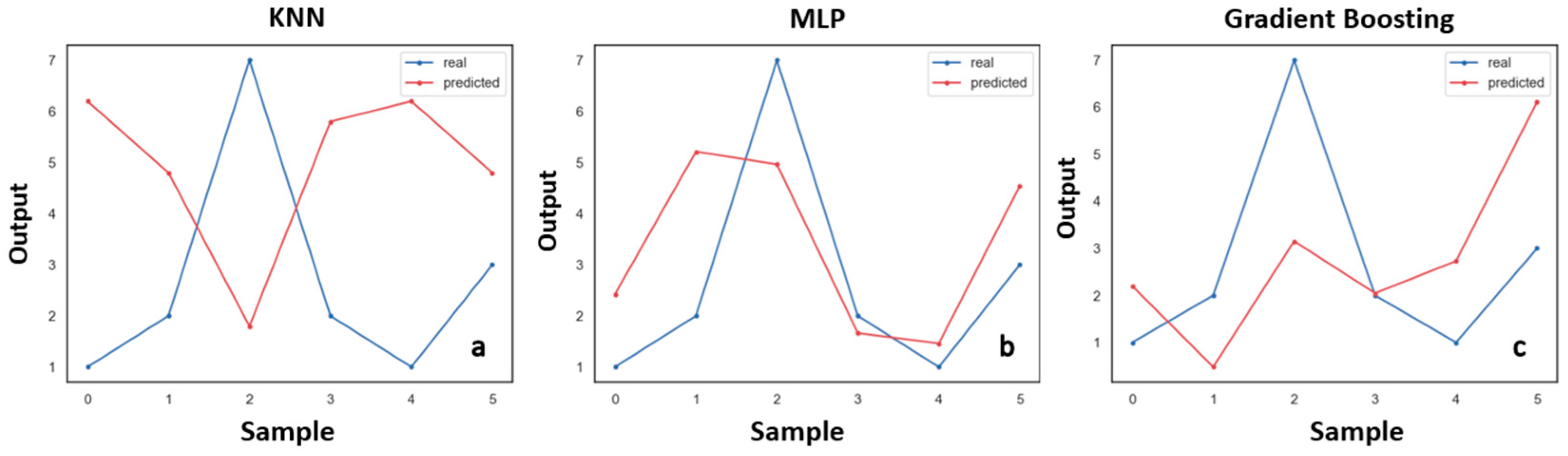

3.3.1. Algorithm Performance for Scenario 1 (Original Dataset)

3.3.2. Algorithm Performance for Scenario 2 (Selected Variables)

3.3.3. Algorithm Performance for Scenario 3 (Selected Variables + SMOTE)

3.3.4. Comparative Analysis of Modeling Scenarios

3.4. Statistical Analysis (ANOVA)

4. Discussion

4.1. Correlation Analysis

4.2. Detailed Discussion of Algorithm Performance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Borrella, I.; Mataix, C.; Carrasco-Gallego, R. Smallholder farmers in the speciality coffee industry: Opportunities, constraints and the businesses that are making it possible. IDS Bull. 2015, 46, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesso, P.P.; Sesso Filho, U.A.; Pereira, L.F.P. Dimensionamento do agronegócio do café no Brasil. Cad. Ciência Tecnol. Brasília 2021, 38, 26901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, A.L.R.; Cabrera, L.C.; Caldarelli, C.E. Cadeia produtiva e mercado cafeeiro no Brasil: Desafios e potencialidades. Rev. Econ. Ens. 2021, 36, 128–145. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, L.d.S.; Amaral, A.M.S.D.; Rezende, T.T.; Putti, F.F.; Góes, B.C. Export behavior of the Brazilian coffee agribusiness and interactions with production elements. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e39210313503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundhe, S.; Sanap, J.; Jadhav, P.; Kalsadkar, V.; Das, C. Forecasting crop yield for sustainable agriculture. Int. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Commun. Technol. 2021, 3, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzman, M.E.; Carmona, F.; Rivas, R.; Niclòs, R. Early assessment of crop yield from remotely sensed water stress and solar radiation data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 145, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whetton, R.; Zhao, Y.; Shaddad, S.; Mouazen, A.M. Nonlinear parametric modelling to study how soil properties affect crop yields and NDVI. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 138, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elavarasan, D.; Vincent, D.R.; Sharma, V.; Zomaya, A.Y.; Srinivasan, K. Forecasting yield by integrating agrarian factors and machine learning models: A survey. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 155, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aono, A.H.; Pimenta, R.J.G.; Francisco, F.R.; DE Souza, A.P.; Lorena, A.C. Machine learning for crop science: Applications and perspectives in maize breeding. Rev. Bras. Milho E Sorgo 2022, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, P.; Allen, R.T.; Endres, M.G. Machine learning for pattern discovery in management research. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 42, 30–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugenio, F.C.; Badin, T.L.; Fernandes, P.; Mallmann, C.L.; Schons, C.; Schuh, M.S.; Pereira, R.S.; Fantinel, R.A.; da Silva, S.D.P. Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (UAVS) and machine learning: A review in the context of forest science. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2021, 42, 8207–8235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Plas, T.L.; Alexander, D.G.; Pocock, M.J. Monitoring protected areas by integrating machine learning, remote sensing and citizen science. Ecol. Solut. Evid. 2025, 6, e70040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, D.; Banday, R.U.Z. Transforming crop management through advanced AI and machine learning: Insights into innovative strategies for sustainable agriculture. AI Comput. Sci. Robot. Technol. 2024, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júnior, C.A.M.d.A.; Martins, G.D.; Xavier, L.C.M.; Vieira, B.S.; Gallis, R.B.d.A.; Junior, E.F.F.; Martins, R.S.; Paes, A.P.B.; Mendonça, R.C.P.; Lima, J.V.D.N. Estimating coffee plant yield based on multispectral images and machine learning models. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martello, M.; Molin, J.P.; Wei, M.C.F.; Filho, R.C.; Nicoletti, J.V.M. Coffee-yield estimation using high-resolution time-series satellite images and machine learning. AgriEngineering 2022, 4, 888–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.S.; Wang, J. Local Field-Scale Winter Wheat Yield Prediction Using VENµS Satellite Imagery and Machine Learning Techniques. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittichotsatsawat, Y.; Tippayawong, N.; Tippayawong, K.Y. Prediction of arabica coffee production using artificial neural network and multiple linear regression techniques. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carielo, M.S.; Prestes, J.A.L.; Marinho, W.A.T. Modelagem preditiva com aprendizagem de máquina para a produção de café dos municípios de Minas Gerais. In Proceedings of the Congresso Brasileiro de Engenharia Agrícola-CONBEA, Online, 8–10 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lorençone, J.A.; DE Oliveira Aparecido, L.E.; Lorençone, P.A. Previsão da produtividade do café com base em dados agroclimáticos e aprendizagem de máquina. Int. J. Environ. Resil. Res. Sci. 2021, 3, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.P.; Corrales, D.C.; Griol, D.; Callejas, Z.; Corrales, J.C. A Non-Destructive Time Series Model for the Estimation of Cherry Coffee Production. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 70, 4725–4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, C.H.; Coelho, R.D.; Costa, J.d.O.; Sentelhas, P.C. Smart Coffee: Machine Learning Techniques for Estimating Arabica Coffee Yield. AgriEngineering 2024, 6, 4925–4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, R.d.O.; Filho, A.C.M.; Santana, L.S.; Martins, M.B.; Sobrinho, R.L.; Zoz, T.; de Oliveira, B.R.; Alwasel, Y.A.; Okla, M.K.; Abdelgawad, H. Models for predicting coffee yield from chemical characteristics of soil and leaves using machine learning. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 5197–5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouadio, L.; Deo, R.C.; Byrareddy, V.; Adamowski, J.F.; Mushtaq, S.; Nguyen, V.P. Artificial intelligence approach for the prediction of Robusta coffee yield using soil fertility properties. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 155, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, B.D.S.; Ferraz, G.A.e.S.; Costa, L.; Ampatzidis, Y.; Vijayakumar, V.; dos Santos, L.M. UAV-based coffee yield prediction utilizing feature selection and deep learning. Smart Agric. Technol. 2021, 1, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; Gonçalves, J.L.M.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorol. Z. 2013, 22, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EMBRAPA. Brazilian Soil Classification System, 5th ed.; Embrapa: Brasília, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, C.H.S.D.; Bartelega, L.; Sera, G.H.; Matiello, J.B.; Almeida, S.R.D.; Santinato, F.; Hotz, A.L. Catálogo de Cultivares de Café Arábica; Embrapa Café: Brasília, Brazil, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Favarin, J.L.; Dourado Neto, D.; García y García, A.; Villa Nova, N.A.; Favarin, M.D.G.G.V. Equations for estimating the coffee leaf area index. Pesqui. Agropecuária Bras. 2002, 37, 769–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazilian Association of Technical Standards (ABNT). Soil Samples Preparation for Compaction and Characterization Tests; ABNT: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2016; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Scholander, P.F.; Bradstreet, E.D.; Hemmingsen, E.A.; Hammel, H.T. Sap pressure in vascular plants. Science 1965, 148, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.M.d.; Lima, E.P.; Coelho, G.; Coelho, M.R.; Coelho, G.S.P. Produtividade, rendimento de grãos e comportamento hídrico foliar em função da época, parcelamento e do método de adubação do cafeeiro Catuaí. Eng. Agrícola 2003, 23, 434–440. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, J.W.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.; Harlan, J. Monitoring the Vernal Advancement of Retrogradation of Natural Vegetation; National Aerospace Spatial Administration: Greenbelt, MD, USA, 1973; 371p.

- Barnes, E.M.; Clarke, T.R.; Richards, S.E.; Colaizzi, P.D.; Haberland, J.; Kostrzewski, M.; Waller, P.; Choi, C.; Riley, E.; Thompson, T.; et al. Coincident detection of crop water stress, nitrogen status and canopy density using ground-based multispectral data. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Precision Agriculture, Bloomington, MN, USA, 16–19 July 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Huete, A.R.; Didan, K.; Miura, T. Development of a two-band enhanced vegetation index without a blue band. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 3833–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.A.D.; Ferraz, G.A.E.S.; Figueiredo, V.C.; Volpato, M.M.L.; Machado, M.L.; Silva, V.A. Evaluation of the Water Conditions in Coffee Plantations Using RPA. AgriEngineering 2022, 5, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.A.S.; Ferraz, G.A.E.S.; Figueiredo, V.C.; Valente, G.F.; Volpato, M.M.L.; Machado, M.L. Soil Moisture Spatial Variability and Water Conditions of Coffee Plantation. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotidis, D.; Abdollahnejad, A.; Surový, P.; Chiteculo, V. Determining tree height and crown diameter from high-resolution UAV imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 2392–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haykin, S. Redes Neurais: Princípios e Prática, 2nd ed.; Bookman: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning internal representations by error propagation. Nature 1986, 323, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fix, E.; Hodges, J.L. Discriminatory Analysis: Nonparametric Discrimination, Consistency Properties; USAF School of Aviation Medicine: Randolph Field, TX, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan, J.R. Induction of decision trees. Mach. Learn. 1986, 1, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, G.A.S.; Silva, F.M.D.; Carvalho, L.C.; Alves, M.D.C.; Franco, B.C. Variabilidade espacial e temporal do fósforo, potássio e da produtividade de uma lavoura cafeeira. Eng. Agrícola 2012, 32, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaMatta, F.M.; Ronchi, C.P.; Maestri, M.; Barros, R.S. Ecophysiology of coffee growth and production. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2007, 19, 485–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.A.; Teodoro, R.E.F.; Melo, B. Productivity and yield of coffee plant under irrigation levels. Pesqui. Agropecuária Bras. 2008, 43, 387–394. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, J.M.; Reinato, R.A.O.; Silva, A.B.d. Modelo matemático para previsão da produtividade do cafeeiro. Rev. Bras. De Eng. Agrícola E Ambient. 2014, 18, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.; García, S.; Herrera, F.; Chawla, N.V. SMOTE for Learning from Imbalanced Data: Progress and Challenges, Marking the 15-year Anniversary. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2018, 61, 863–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, P.; Torgo, L.; Ribeiro, R.P. Revisiting SMOTE: Bias, Variance and Noise in Imbalanced Data Classification. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2020, 53, 843–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelo Luna, D.; Mejía Manzano, J.; Montoya-Bonilla, B.P.; Hoyos García, J. Analysis of the Vegetation Indices NDVI, GNDVI, and NDRE for the Characterization of Coffee Crops (Coffea arabica). Ing. Y Desarro. 2020, 38, 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Group | Unit | Data Source/Method | Sampling Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield | Biophysical | L plant−1 | Semi-mechanized harvest + volumetric method | June 2021 and June 2022 |

| Soil moisture (GH) | Biophysical | % (gravimetric) | Soil sampling (0–20 cm), oven-drying method | Aug. 2020, Jan. 2021, Aug. 2021, Jan. 2022 |

| Leaf water potential (Ψw) | Biophysical | MPa | Scholander pressure chamber | Same as above |

| Soil fertility | Biophysical | Laboratory analysis (pH, P, K, Ca, Mg, etc.) | Apr. 2021 and Apr. 2022 | |

| Leaf nutrient content | Biophysical | g kg−1/mg kg−1 | Laboratory analysis (N, P, K, Ca, Mg, S, etc.) | Jan. 2022 |

| NDVI | Spectral | Calculated from UAV multispectral images | Aug. 2020, Jan. 2021, Aug. 2021, Jan. 2022 | |

| NDRE | Spectral | Same as above | Same as above | |

| EVI2 | Spectral | Same as above | Same as above | |

| Plant height | Spectral | m | DSM–DTM from UAV images | Same as above |

| Canopy diameter | Spectral | m | Manual from orthomosaic (bounding box method) | Same as above |

| Leaf area index (LAI) | Spectral | m2 | Estimated via [28] | Same as above |

| Index | Equations | References |

|---|---|---|

| NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) | [32] | |

| NDRE (Normalized Difference RedEdge) | [33] | |

| EVI2 (Enhanced Vegetation Index 2) | [34] |

| Scenario | Dependent Variable | Independent Variables | Crop Season(s) | Machine Learning Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 Complete Dataset | Yield (L/plant) | All collected variables: - Soil moisture: GH_2020, GH_2021 - Leaf water potential: WP_2021, WP_2022 - Soil fertility: pH, P, K, Ca, Mg, MO, H + Al - Leaf nutrition: N, P, K, Ca, Mg, S, Mn, Zn, B, Cu, Fe - Spectral indices: NDVI, NDRE, EVI2 - Structural traits: plant height, canopy diameter, LAI | 2020/2021 2021/2022 Combined | RF, GB, MLP, KNN, DT |

| Scenario 2 Selected Variables | Yield (L/plant) | Only variables with highest correlation with yield: - 2020/2021: GH_2020, GH_2021, NDRE_2020, pH - 2021/2022: WP_2022, P_leaf, S_leaf, N_leaf, K_leaf - Combined: NDRE_2020, GH_2021, NDVI_2020, H + Al, GH_2020 | 2020/2021 2021/2022 Combined | RF, GB, MLP, KNN, DT |

| Scenario 3 Selected Variables + SMOTE | Yield (L/plant) | Same variables as in Scenario 2, with dataset expanded using SMOTE. Tripled the number of samples from 30 to 90. | 2020/2021 2021/2022 Combined | RF, GB, MLP, KNN, DT |

| Statistic | Yield 2020/2021 | Yield 2021/2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 10.20 | 5.47 |

| Min–Max | 1.00–22.00 | 0.00–22.00 |

| Standard deviation | 4.79 | 5.25 |

| Skewness | 0.43 | 1.12 |

| Variation coefficient (%) | 46.96 | 96.15 |

| Original Dataset | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Models | Season 2020/2021 | Season 2021/2022 | Combined Crop Season (2020/2021 + 2021/2022) | |||||||||

| Training | Test | Training | Test | Training | Test | |||||||

| RMSE | MAPE | RMSE | MAPE | RMSE | MAPE | RMSE | MAPE | RMSE | MAPE | RMSE | MAPE | |

| RF | 4.47 ± 3.62 | - | 6.54 | 3.38 | 8.02 ± 8.12 | 4.50 ±6.11 | 8.59 | - | 5.54 ± 5.60 | - | 11.11 | 0.98 |

| GB | 4.72 ± 3.72 | - | 9.86 | 4.02 | 8.81 ± 9.27 | 4.74 ± 9.61 | 13.66 | - | 5.35 ± 5.75 | - | 11.23 | 1.15 |

| MLP | 5.71 ± 4.06 | - | 5.54 | 3.11 | 9.35 ± 10.62 | 3.97 ± 4.95 | 10.46 | - | 6.42 ± 5.70 | - | 12.41 | 1.53 |

| KNN | 4.45 ± 3.87 | - | 4.21 | 2.51 | 6.71 ± 8.60 | 2.27 ± 2.59 | 12.19 | - | 6.38 ± 5.94 | - | 11.80 | 1.13 |

| DT | 4.96 ± 3.87 | - | 13.06 | 6.16 | 10.30 ± 10.77 | 6.41 ± 15.57 | 15.41 | - | 6.58 ± 7.38 | - | 13.35 | 1.71 |

| Dataset with Selected Variables (Variables with the Highest Correlations with Yield) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Models | Season 2020/2021 (GH_2020, GH_2021, pH and NDRE) | Season 2021/2022 (N, S, P, K Leaf and WP_2022) | Combined (2020/2021 + 2021/2022) (H + Al, NDRE_2020, GH_2020, GH, 2021 and NDVI_2020) | |||||||||

| Training | Test | Training | Test | Training | Test | |||||||

| RMSE | MAPE | RMSE | MAPE | RMSE | MAPE | RMSE | MAPE | RMSE | MAPE | RMSE | MAPE | |

| RF | 5.01 ± 3.73 | - | 2.61 | 1.43 | 6.92 ± 7.89 | - | 9.68 | - | 6.97 ± 7.65 | - | 5.26 | 3.27 |

| GB | 5.73 ± 3.99 | - | 2.66 | 0.89 | 7.52 ± 9.57 | - | 9.14 | - | 7.97 ± 8.86 | - | 5.53 | 2.48 |

| MLP | 4.72 ± 3.52 | - | 1.78 | 0.74 | 11.92 ± 13.45 | - | 15.58 | - | 8.06 ± 6.91 | - | 5.34 | 1.80 |

| KNN | 4.51 ± 3.00 | - | 2.76 | 1.55 | 6.77 ± 7.95 | - | 11.18 | - | 6.30 ± 6.70 | - | 5.26 | 2.26 |

| DT | 6.20 ± 4.92 | - | 3.02 | 0.66 | 8.34 ± 8.12 | - | 15.92 | - | 8.41 ± 9.41 | - | 10.88 | 3.79 |

| Dataset with Selected Variables Using the SMOTE Technique (Tripling the Data Volume) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Models | Season 2020/2021 (GH_2020, GH_2021, pH and NDRE) | Season 2021/2022 (N, S, P, K Leaf and WP_2022) | Combined (2020/2021 + 2021/2022) (H + Al, NDRE_2020, GH_2020, GH, 2021 and NDVI_2020) | |||||||||

| Training | Test | Training | Test | Training | Test | |||||||

| RMSE | MAPE | RMSE | MAPE | RMSE | MAPE | RMSE | MAPE | RMSE | MAPE | RMSE | MAPE | |

| RF | 1.39 ± 2.31 | - | 2.09 | 0.83 | 1.75 ± 2.29 | - | 9.04 | - | 2.69 ± 4.63 | - | 6.89 | 4.41 |

| GB | 1.24 ± 2.49 | - | 2.28 | 0.88 | 0.91 ± 1.99 | - | 12.42 | - | 2.56 ± 4.64 | - | 7.84 | 4.24 |

| MLP | 1.72 ± 2.41 | - | 2.82 | 1.77 | 2.29 ± 2.11 | - | 13.11 | - | 3.34 ± 4.06 | - | 5.61 | 2.26 |

| KNN | 1.74 ± 2.23 | - | 5.14 | 2.90 | 3.15 ± 4.12 | - | 17.64 | - | 3.32 ± 4.97 | - | 5.49 | 2.88 |

| DT | 0.90 ± 2.67 | - | 3.14 | 0.67 | 1.06 ± 3.86 | - | 10.53 | - | 2.15 ± 5.98 | - | 11.31 | 6.37 |

| Scenario | Season | Type of Comparison | Significant Differences (p < 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 2020/2021 | Within-season |

|

| 3 | 2021/2022 | Within-season |

|

| 3 | Combined | Within-season |

|

| 1 | 2020/2021 × 2021/200 | Cross-season |

|

| 1 | 2021/2022 × Combined | Cross-season |

|

| 2 | 2020/2021 × Combined | Cross-season |

|

| 2 | 2021/2022 × Combined | Cross-season |

|

| 3 | 2020/2021 × 2021/2022 | Cross-season |

|

| 3 | 2020/2021 × Combined | Cross-season |

|

| 3 | 2021/2022 × Combined | Cross-season |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, S.A.d.S.; Ferraz, G.A.e.S.; Figueiredo, V.C.; Volpato, M.M.L.; Ferreira, D.D.; Machado, M.L.; Borges, F.E.d.M.; Conti, L. Integration of Field Data and UAV Imagery for Coffee Yield Modeling Using Machine Learning. Drones 2025, 9, 717. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9100717

Silva SAdS, Ferraz GAeS, Figueiredo VC, Volpato MML, Ferreira DD, Machado ML, Borges FEdM, Conti L. Integration of Field Data and UAV Imagery for Coffee Yield Modeling Using Machine Learning. Drones. 2025; 9(10):717. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9100717

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Sthéfany Airane dos Santos, Gabriel Araújo e Silva Ferraz, Vanessa Castro Figueiredo, Margarete Marin Lordelo Volpato, Danton Diego Ferreira, Marley Lamounier Machado, Fernando Elias de Melo Borges, and Leonardo Conti. 2025. "Integration of Field Data and UAV Imagery for Coffee Yield Modeling Using Machine Learning" Drones 9, no. 10: 717. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9100717

APA StyleSilva, S. A. d. S., Ferraz, G. A. e. S., Figueiredo, V. C., Volpato, M. M. L., Ferreira, D. D., Machado, M. L., Borges, F. E. d. M., & Conti, L. (2025). Integration of Field Data and UAV Imagery for Coffee Yield Modeling Using Machine Learning. Drones, 9(10), 717. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9100717