Optimized Autonomous Drone Navigation Using Double Deep Q-Learning for Enhanced Real-Time 3D Image Capture

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Context and Justification

1.2. Motivation and Problem Definition

1.3. Objectives of This Study

- Identify a suitable drone for the project equipped with a high-quality monocular RGB camera and programmable via a Software Development Kit (SDK), ensuring the ability to optimize its navigation.

- Design an autonomous navigation system that enables real-time image capture, aimed at covering large outdoor areas while optimizing the drone’s trajectory based on its perception of the environment to fully capture the targets with the shortest possible path, with the consequent battery saving.

- Integrate and validate the 3D mesh generation subsystems with the navigation subsystem, creating a demonstrative prototype that showcases the system’s effectiveness in data capture for subsequent mesh processing.

1.4. Contributions of This Work

2. Related Work

2.1. Autonomous Drone Navigation

2.2. Reconstruction Using Drones

2.3. Reinforcement Learning in Autonomous Navigation

2.3.1. Q-Learning (QL)

2.3.2. Deep Q-Learning Networks (DQNs)

- Experience Replay: Stores the agent’s experiences in a replay memory and updates the neural network using minibatches of these experiences selected randomly. This reduces the correlation between consecutive samples and improves learning efficiency. This improvement is reviewed in more detail at the end of this section.

- Fixed Target Network: Uses a copy of the Q-network that is periodically updated to calculate target values, reducing oscillation and divergence during training.

2.3.3. Double Deep Q-Learning Networks (DDQNs)

2.3.4. Prioritized Experience Replay

3. Materials and Methods

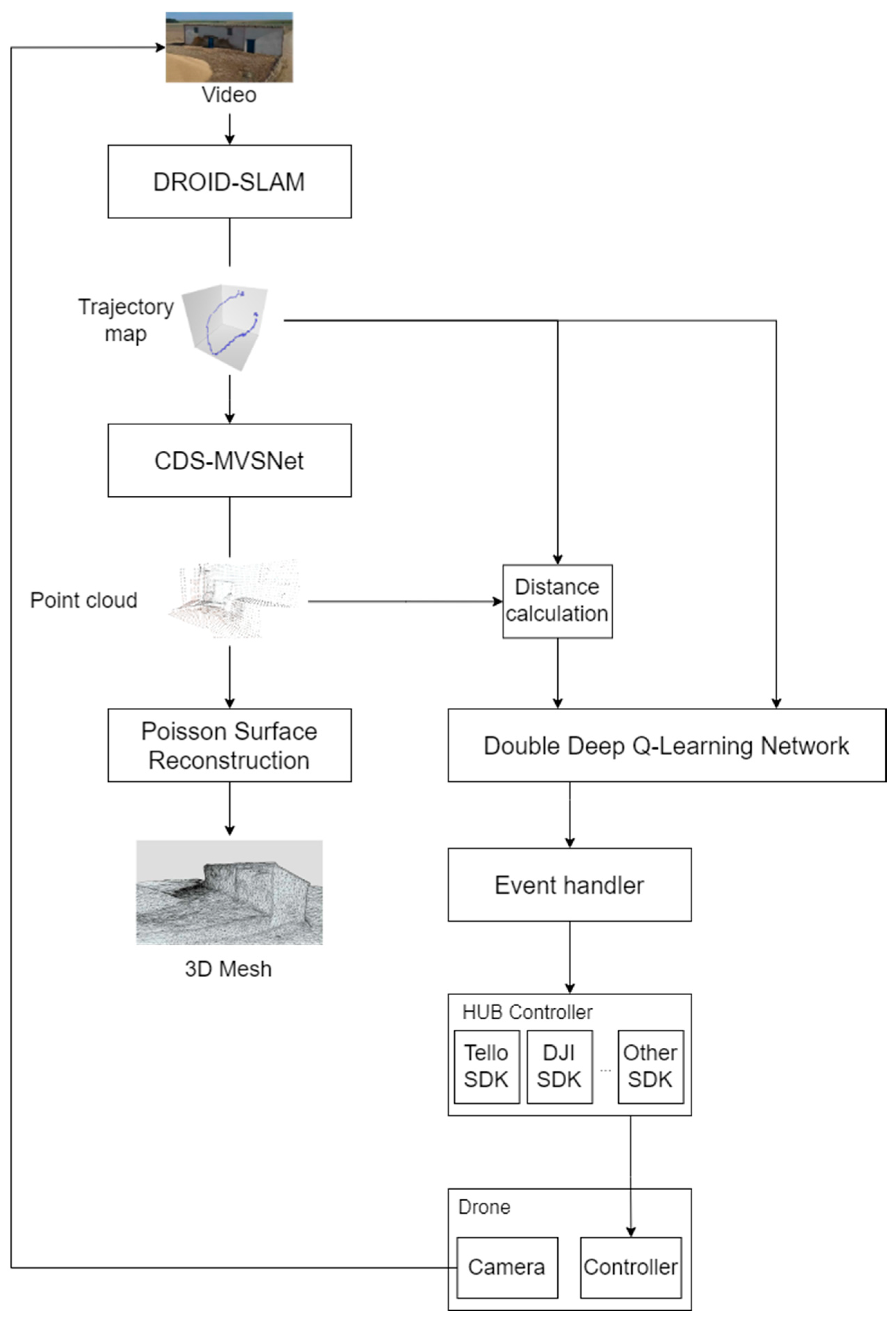

3.1. System Architecture Overview

3.2. Design of the DDQN Algorithm with Prioritized Experience Replay

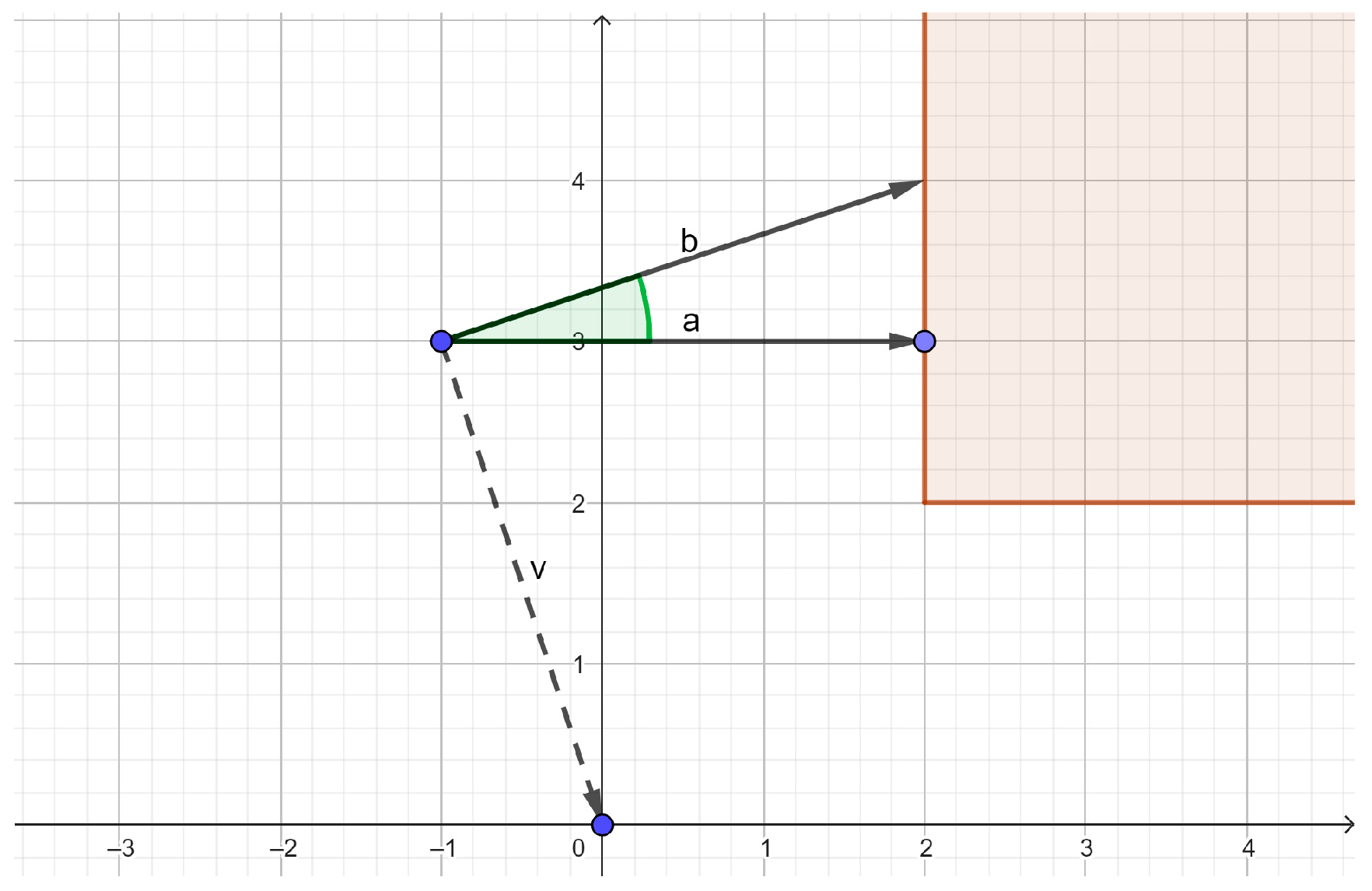

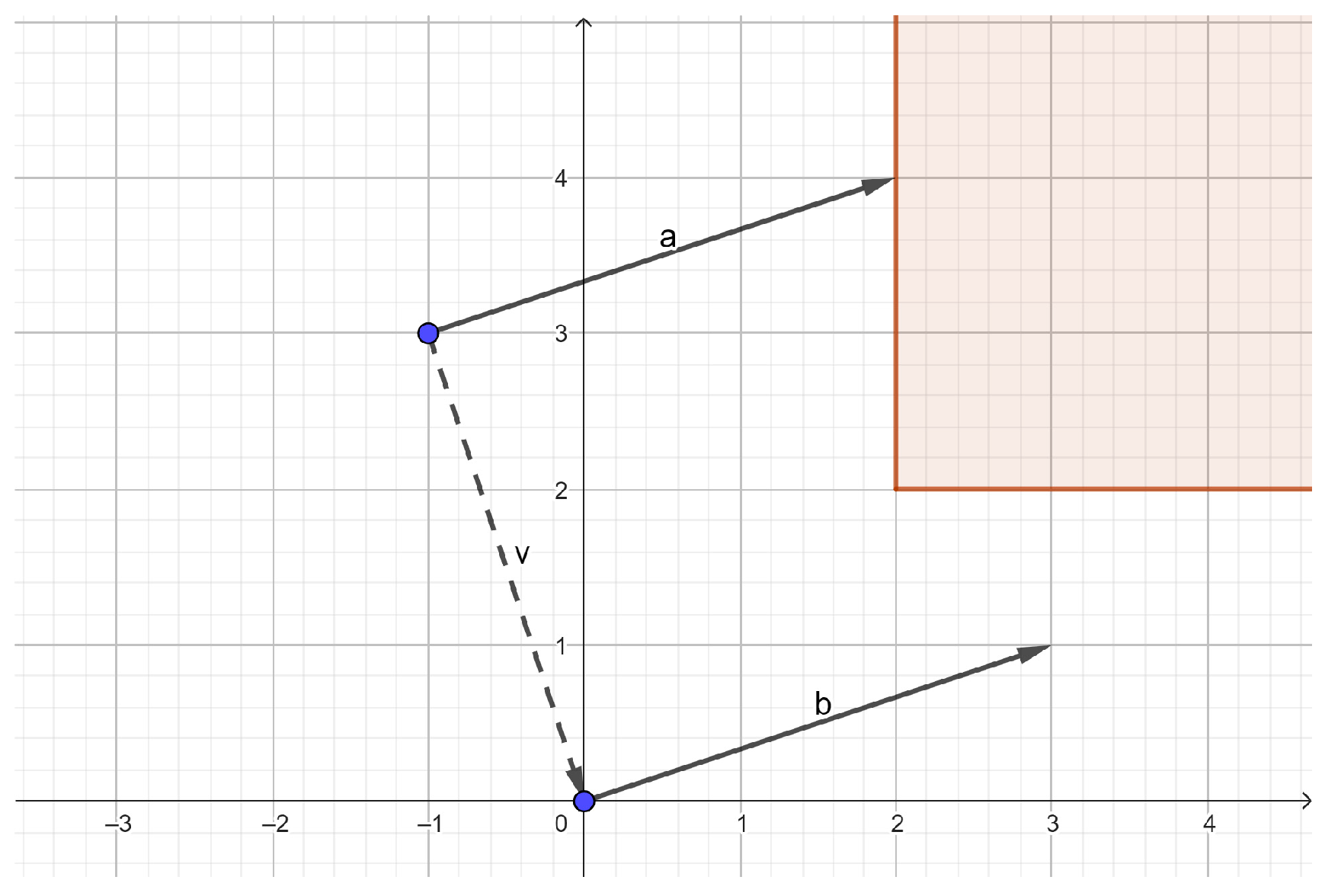

3.2.1. Environment

3.2.2. DDQN Agent

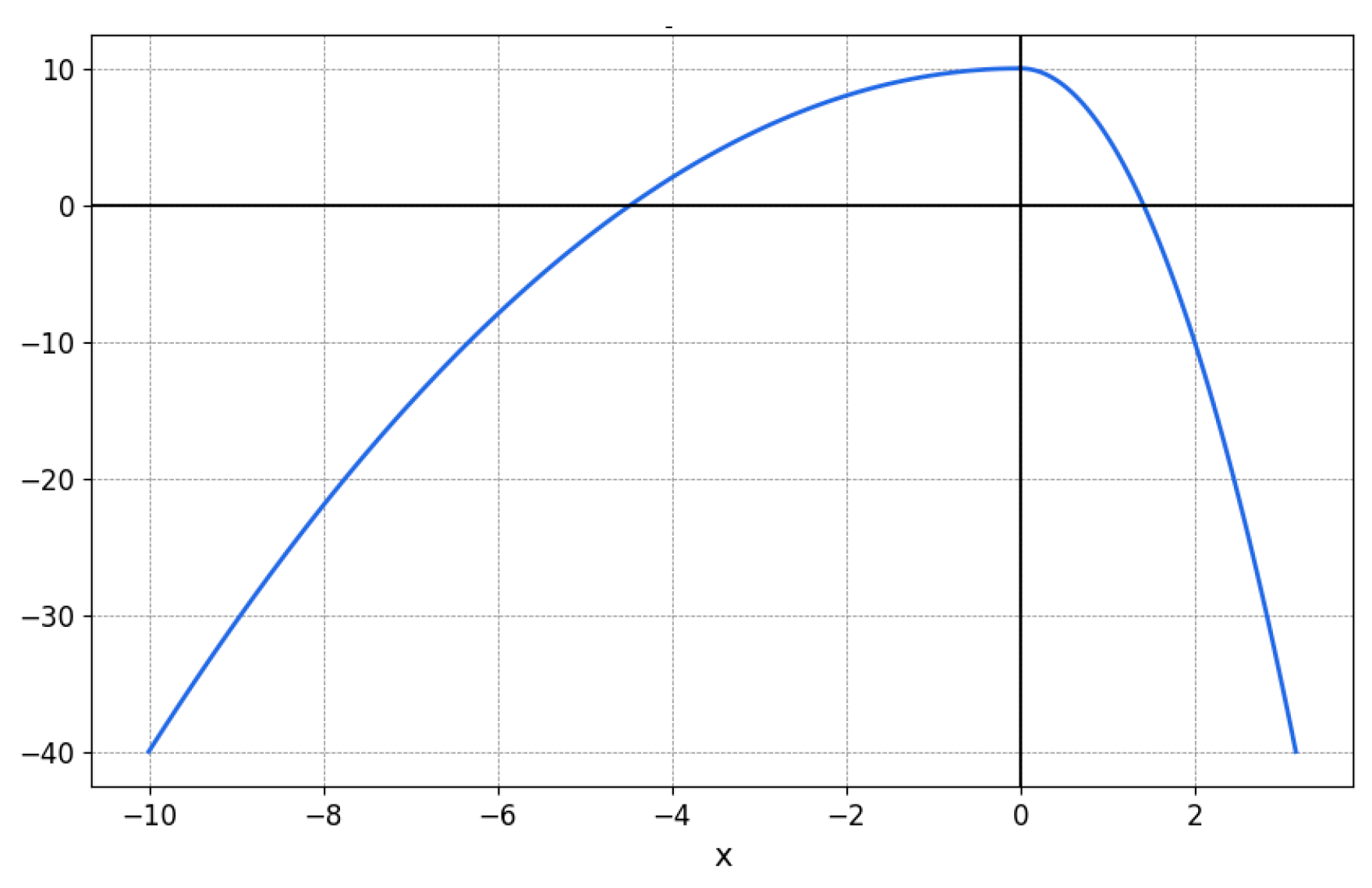

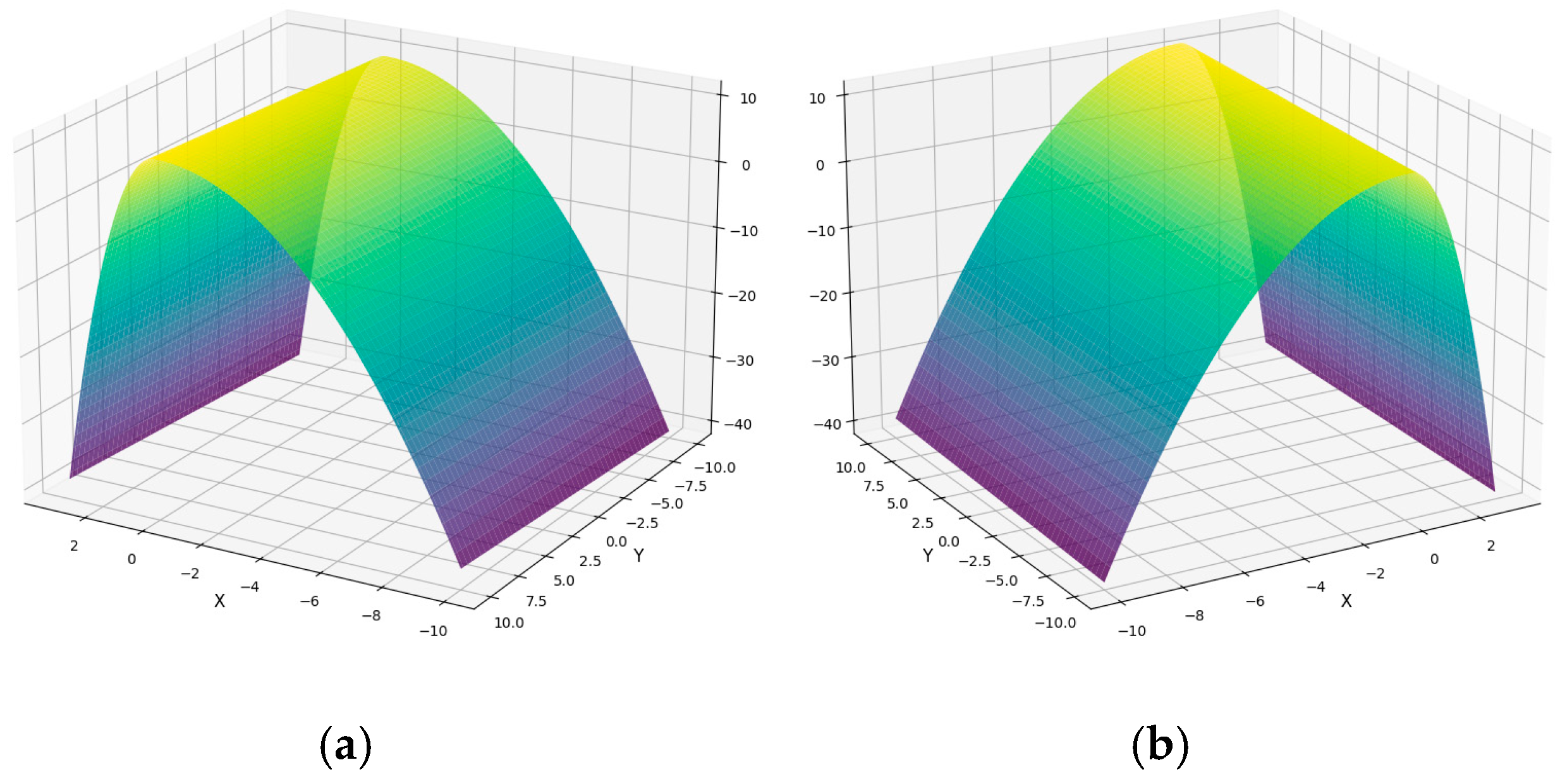

3.2.3. Reward Function

3.2.4. Point Cloud Distance Calculation Model

- -

- is the first quartile (25th percentile) of the dataset.

- -

- is the third quartile (75th percentile) of the dataset.

- -

- represents the interquartile range.

- -

- .

- -

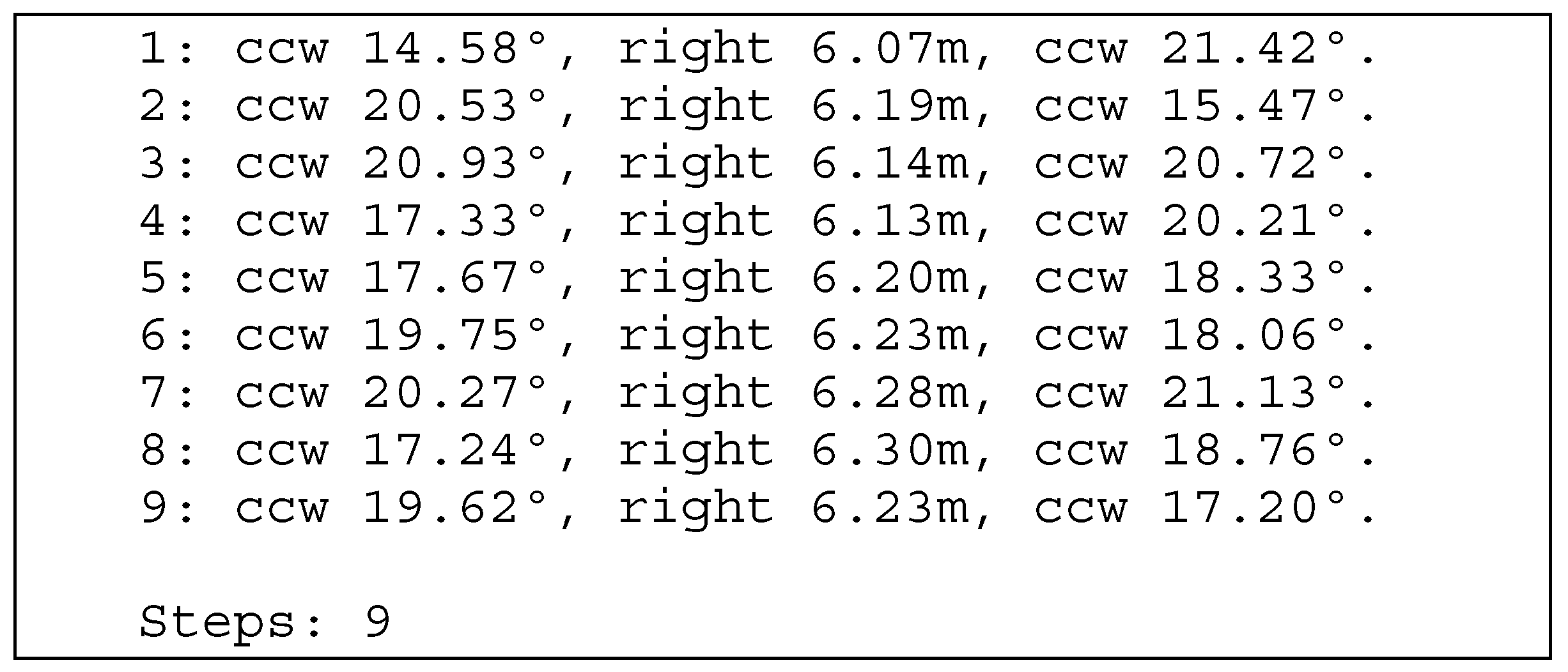

3.2.5. Flight Instructions

Rotation About the Z-Axis

Movement Toward the Desired Position

3.2.6. Training and Flight Algorithm

| Algorithm 1: Double Deep Q-Learning Network with Prioritized Experience Replay training Algorithm |

| Initialize replay memory to capacity . Initialize prioritized sampling mechanism to capacity . Initialize action-value functions and with random weights and . Initialize target network with weights . Initialize the environment. for episode do |

| Initialize randomly the desired distance in the defined range. Choose a random scenario from the set of scenarios. Reset the environment with the chosen scenario. Initialize the state to . for do |

| With probability select a random action . Otherwise select . Execute action in the environment and observe reward and next state . Store the transition in assigning a maximum priority. Set . Sample a minibatch of transitions from using prioritized sampling. for each sampled transition do |

| Set Update the priority of the transition in based on the updated TD-error. |

| end for Perform a gradient descent step on the loss function . Set , where is the exploration decay parameter. Update the target network using the soft update mechanism, defined by: . |

| end for |

| end for |

| Algorithm 2: Flight loop |

| Load the weights of the trained model in a new agent. Initialize the environment. Initialize the desired distance in the defined range. Reset the environment with the flight scenario. Initialize the state to . Save the initial position and the initial Z-rotation, . for do |

| Select an action given by the trained agent. Execute action in polar coordinates. Save the desired position . Generate the movement command from to . Generate the rotation command to refocus on the object. Observe reward and next state . Set . |

| end for |

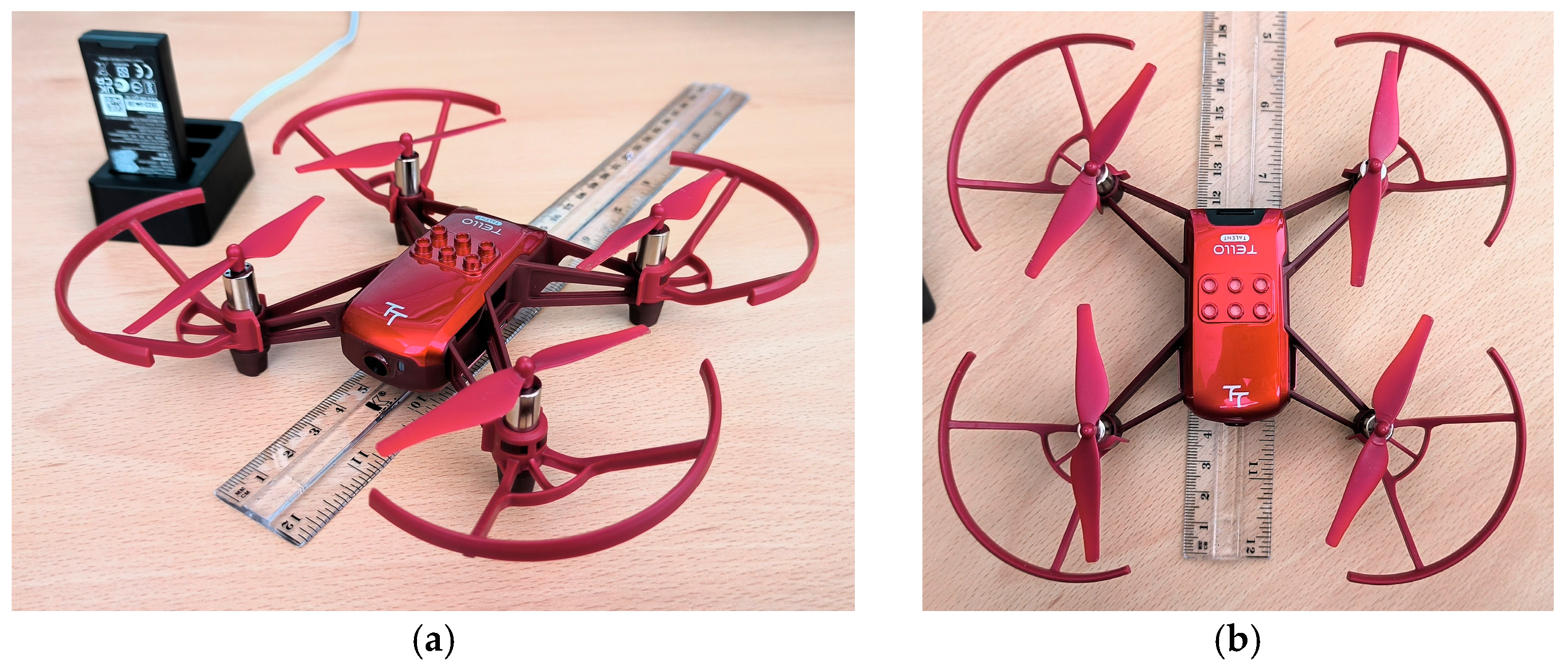

3.3. Drone and Workstation

4. Results

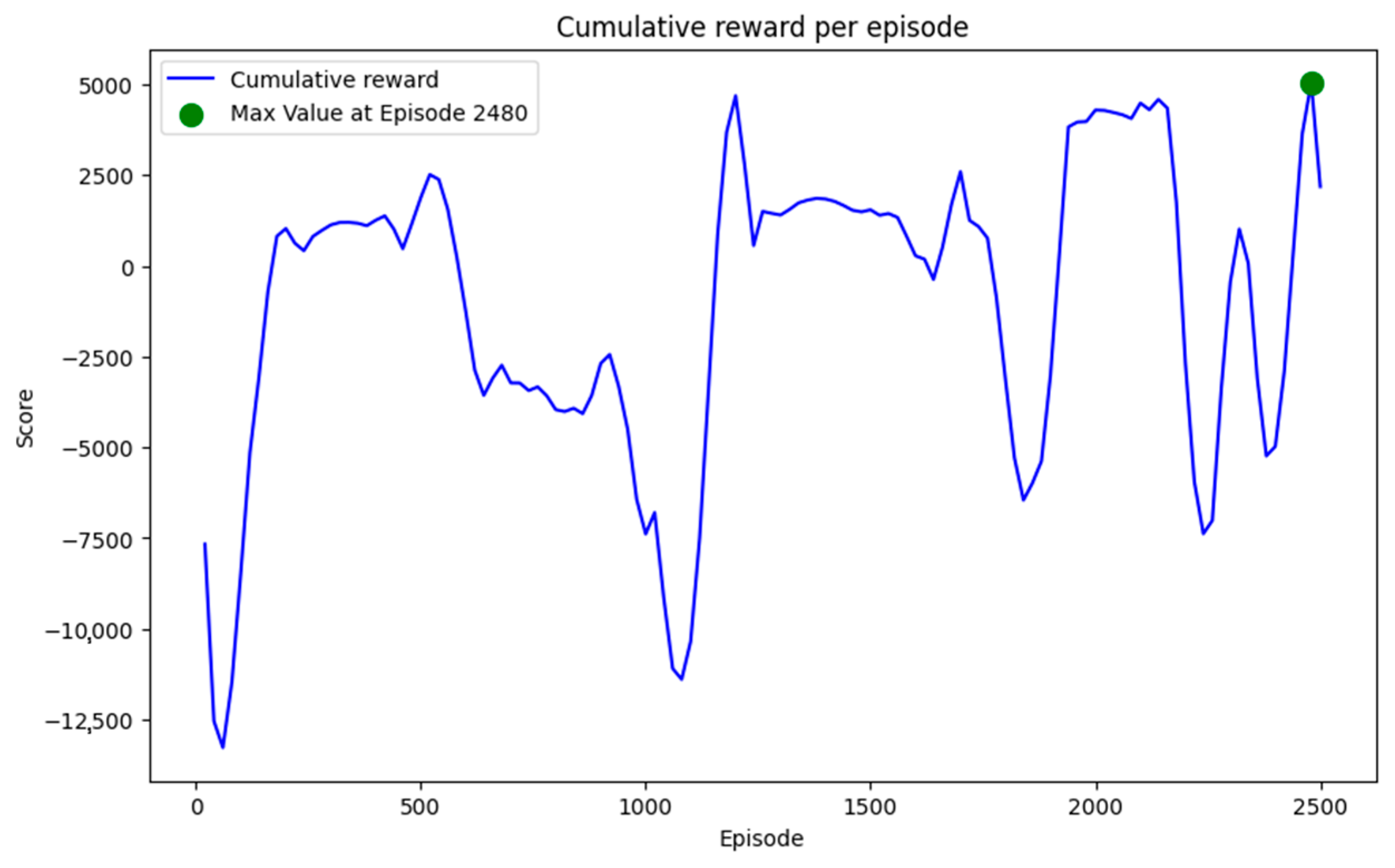

4.1. Training of the DDQN Model

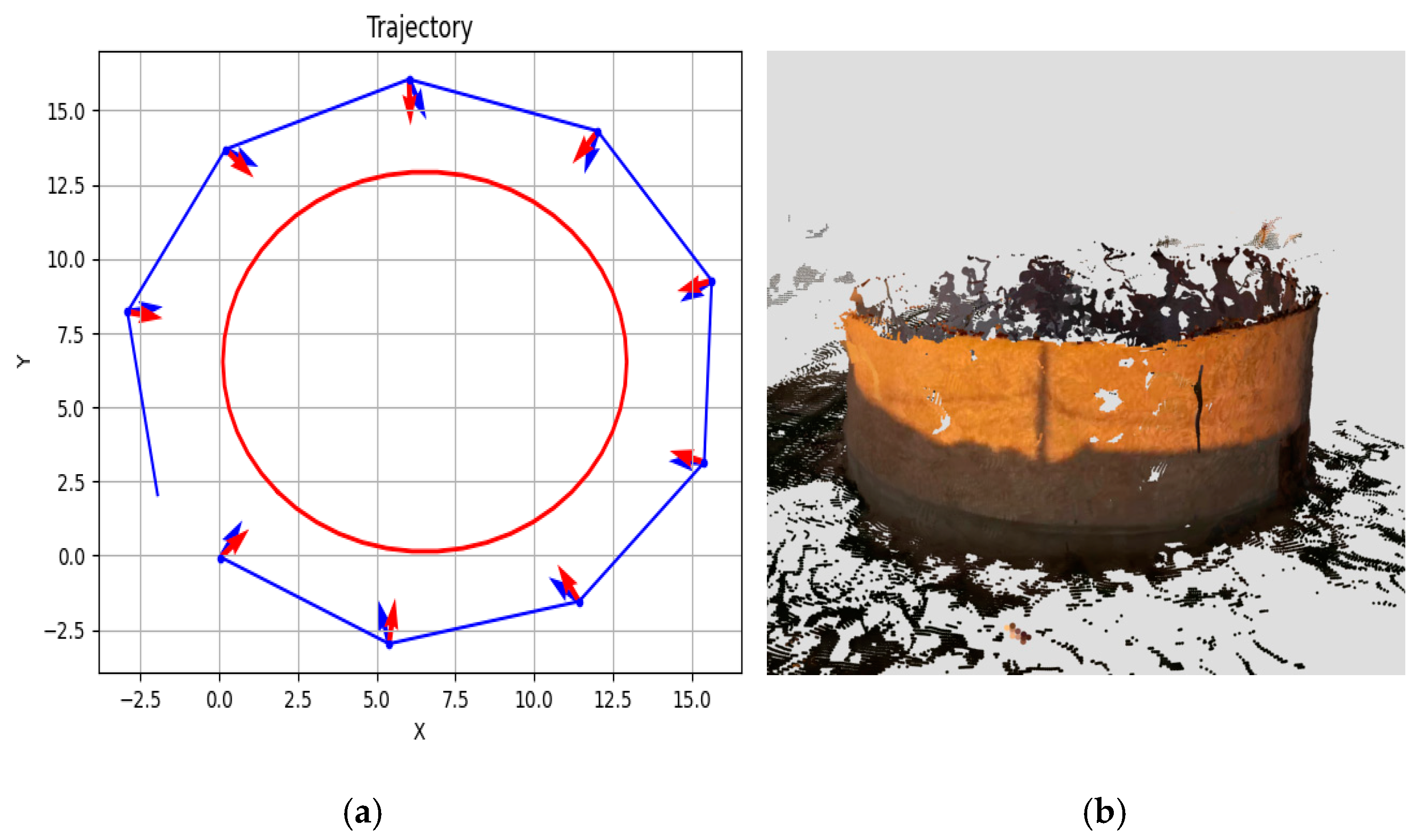

4.2. Generation of Flight Instructions

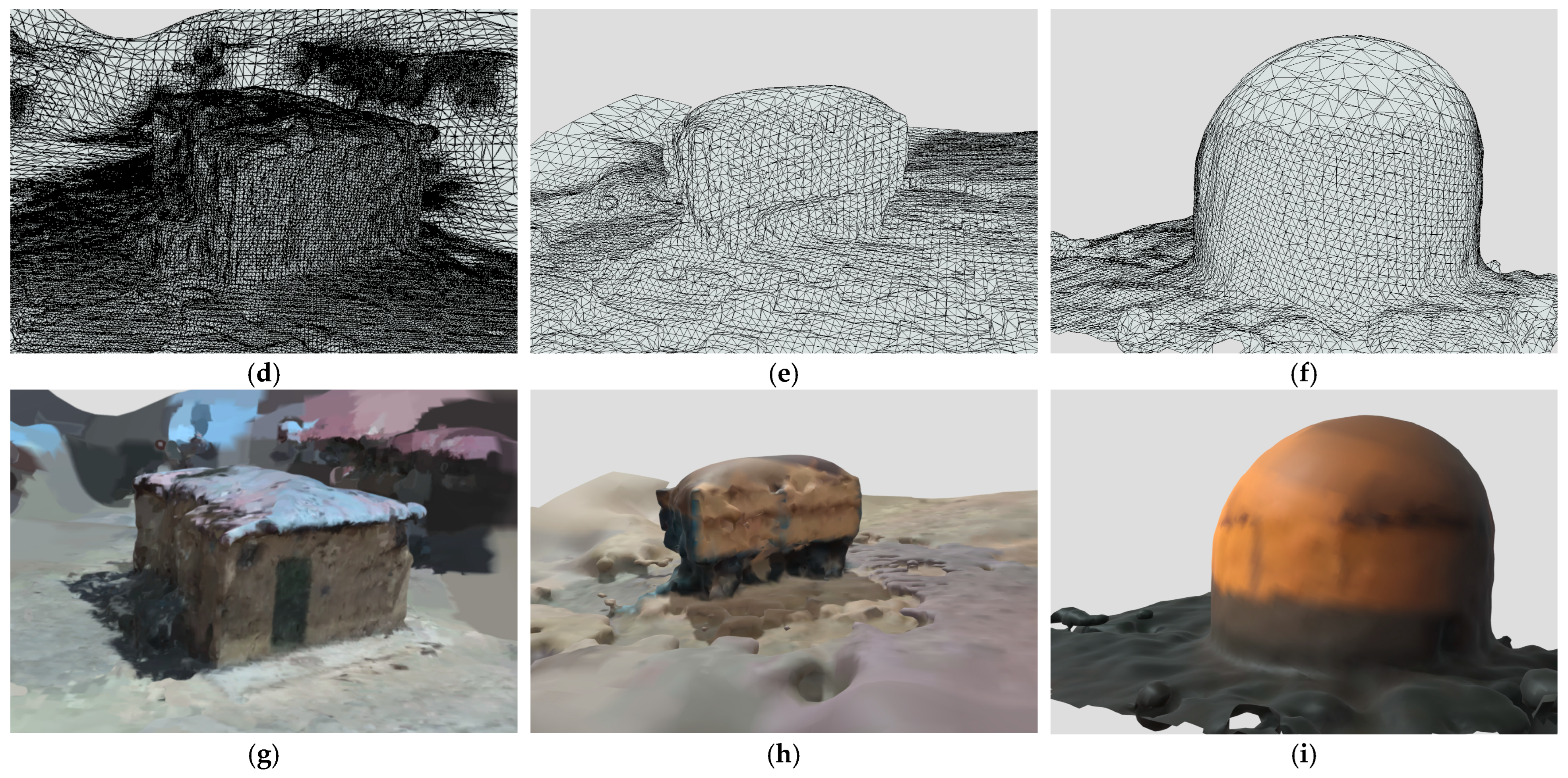

4.3. Automatic Generation of 3D Meshes

5. Discussion

5.1. Automation and Efficiency

5.2. Training Optimization

5.3. Autonomous Decision-Making

5.4. Practical Applications

5.5. Limitations

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- El-Sallabi, H.; Aldosari, A.; Alkaabi, S. UAV path planning in absence of GPS signals. In Proceedings of the Unmanned Systems Technology, Anaheim, CA, USA, 9–13 April 2017; Volume 10195, pp. 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhu, M.; Zou, L.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y. Learning Reward Function with Matching Network for Mapless Navigation. Sensors 2020, 20, 3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, C.-K.; Segor, F. Onboard pattern recognition for autonomous UAV landing. In Proceedings of the Applications of Digital Image Processing XXXV, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–16 August 2012; Volume 8499, pp. 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Said, N.; Gorbachev, Y. An Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Navigation System on the Basis of Pattern Recognition Applications. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. 2020, 55, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Yong, S.P.; Pedrycz, W.; Watada, J. Testing a Vision-Based Autonomous Drone Navigation Model in a Forest Environment. Algorithms 2024, 17, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Mahmoudian, N. Synergistic Reinforcement and Imitation Learning for Vision-driven Autonomous Flight of UAV Along River. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.09332v2. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Ye, Y.; Du, J. Multi-objective reinforcement learning for autonomous drone navigation in urban areas with wind zones. Autom. Constr. 2024, 158, 105253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wubben, J.; Fabra, F.; Calafate, C.T.; Krzeszowski, T.; Marquez-Barja, J.M.; Cano, J.C.; Manzoni, P. Accurate Landing of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Using Ground Pattern Recognition. Electronics 2019, 8, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visockiene, J.S.; Puziene, R.; Stanionis, A.; Tumeliene, E. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles for Photogrammetry: Analysis of Orthophoto Images over the Territory of Lithuania. Int. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2016, 2016, 4141037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; He, T.; Wu, S.; Wang, S.; Dai, B.; Yang, Q.; Lei, Y. Application research of image recognition technology based on CNN in image location of environmental monitoring UAV. EURASIP J. Image Video Process. 2018, 2018, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, P.; Liu, X.; Uzochukwu, B. Fast and Accurate, Convolutional Neural Network Based Approach for Object Detection from UAV. In Proceedings of the IECON 2018—44th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Washington, DC, USA, 21–23 October 2018; pp. 3171–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokkeland, M.; Klausen, K.; Johansen, T.A. Autonomous visual navigation of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle for wind turbine inspection. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems, ICUAS, Denver, CO, USA, 9–12 June 2015; pp. 998–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Cha, Y.J. SDDNet: Real-Time Crack Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 8016–8025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, A.; Kang, D.; Cha, Y.J. Deep learning-based obstacle-avoiding autonomous UAVs with fiducial marker-based localization for structural health monitoring. Struct. Health Monit. 2024, 23, 971–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, J.C.; Rosende, S.B.; Sánchez-Soriano, J. Automatic Real-Time Creation of Three-Dimensional (3D) Representations of Objects, Buildings, or Scenarios Using Drones and Artificial Intelligence Techniques. Drones 2023, 7, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Informe Sobre Las Actuaciones Y Medidas Emprendidas Tras La Erupción Del Volcán De Cumbre Vieja (La Palma), Seis Meses Después Del Inicio De La Emergencia. Available online: https://www.mpr.gob.es/prencom/notas/Documents/2022/060622-informe_palma.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Informe de Incendios Forestales 2022 Informes DGPCE. Available online: https://www.proteccioncivil.es/documents/20121/0/INFORME%20IIFF%202022-FINAL_DICIEMBRE.pdf/a9cf0986-be76-d244-283a-4d3295309fae#:~:text=A%20lo%20largo%20de%202022,superior%20respecto%20a%20a%C3%B1os%20anteriores (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- DJI Terra—Digitaliza el Mundo—DJI. Available online: https://enterprise.dji.com/es/dji-terra (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Jarahizadeh, S.; Salehi, B. A Comparative Analysis of UAV Photogrammetric Software Performance for Forest 3D Modeling: A Case Study Using AgiSoft Photoscan, PIX4DMapper, and DJI Terra. Sensors 2024, 24, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliane, N.; Muñoz, C.Q.G.; Sánchez-Soriano, J. Web and MATLAB-Based Platform for UAV Flight Management and Multispectral Image Processing. Sensors 2022, 22, 4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertas, E.; De-Las-Heras, G.; Fernández-Andrés, J.; Sánchez-Soriano, J. Dataset: Roundabout Aerial Images for Vehicle Detection. Data 2022, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertas, E.; De-Las-heras, G.; Sánchez-Soriano, J.; Fernández-Andrés, J. Dataset: Variable Message Signal Annotated Images for Object Detection. Data 2022, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosende, S.B.; Ghisler, S.; Fernández-Andrés, J.; Sánchez-Soriano, J. Dataset: Traffic Images Captured from UAVs for Use in Training Machine Vision Algorithms for Traffic Management. Data 2022, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosende, S.B.; Fernandez-Andres, J.; Sanchez-Soriano, J. Optimization Algorithm to Reduce Training Time for Deep Learning Computer Vision Algorithms Using Large Image Datasets with Tiny Objects. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 104593–104605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosende, S.B.; Ghisler, S.; Fernández-Andrés, J.; Sánchez-Soriano, J. Implementation of an Edge-Computing Vision System on Reduced-Board Computers Embedded in UAVs for Intelligent Traffic Management. Drones 2023, 7, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, B. Frontier-based approach for autonomous exploration. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Computational Intelligence in Robotics and Automation, CIRA, Monterey, CA, USA, 11 June 1997; pp. 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, P.; Chen, B.; Lu, S.; Meng, X.; Liang, Y. Information-Driven Fast Marching Autonomous Exploration with Aerial Robots. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Du, Z.; Yang, J. Topological Map-Based Autonomous Exploration in Large-Scale Scenes for Unmanned Vehicles. Drones 2024, 8, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.S.; Lad, S.S.; Singh, A.M. Exploring the Use of Deep Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Navigation in Unstructured Environments. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 12, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, C.; Haala, N. Guided by model quality: UAV path planning for complete and precise 3D reconstruction of complex buildings. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 127, 103667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesack, R. Processing in Progress: A Benchmark Analysis of Photogrammetry Applications for Digital Architectural Documentation. Technol. Archit. Des. 2022, 6, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COLMAP 3.11.0.dev0. Documentation. Available online: https://colmap.github.io/index.html (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Photogrammetry Software: Top Choices for All Levels. 3Dnatives. Available online: https://www.3dnatives.com/en/photogrammetry-software-190920194/ (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- YouTube. (106) ContextCapture CONNECT Edition Overview. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y5qoqHIl3fY (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- ZGharineiat; Kurdi, F.T.; Henny, K.; Gray, H.; Jamieson, A.; Reeves, N. Assessment of NavVis VLX and BLK2GO SLAM Scanner Accuracy for Outdoor and Indoor Surveying Tasks. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdi, F.T.; Lewandowicz, E.; Gharineiat, Z.; Shan, J. Accurate Calculation of Upper Biomass Volume of Single Trees Using Matrixial Representation of LiDAR Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, D.; Huang, A.; Maddison, C.J.; Guez, A.; Sifre, L.; Van Den Driessche, G.; Schrittwieser, J.; Antonoglou, I.; Panneershelvam, V.; Lanctot, M.; et al. Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature 2016, 529, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Graves, A.; Antonoglou, I.; Wierstra, D.; Riedmiller, M. Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 1312, arXiv:1312.5602v1. [Google Scholar]

- Azar, A.T.; Koubaa, A.; Ali Mohamed, N.; Ibrahim, H.A.; Ibrahim, Z.F.; Kazim, M.; Ammar, A.; Benjdira, B.; Khamis, A.M.; Hameed, I.A.; et al. Drone Deep Reinforcement Learning: A Review. Electronics 2021, 10, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, C. Double Deep Q Networks. Tackling Maximization Bias in Deep Q-Learning. Towards Data Science. Available online: https://towardsdatascience.com/double-deep-q-networks-905dd8325412 (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Schaul, T.; Quan, J.; Antonoglou, I.; Silver, D.; Deepmind, G. Prioritized Experience Replay. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2–4 May 2016; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About—OpenCV. Available online: https://opencv.org/about/ (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Giang, K.T.; Song, S.; Jo, S. Curvature-guided dynamic scale networks for Multi-view Stereo. In Proceedings of the ICLR 2022—10th International Conference on Learning Representations, Virtual, 4 May 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teed, Z.; Deng, J. DROID-SLAM: Deep Visual SLAM for Monocular, Stereo, and RGB-D Cameras. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 16558–16569. Available online: https://github.com/princeton-vl/DROID-SLAM (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- AliceVision Meshroom—3D Reconstruction Software. Available online: https://alicevision.org/#meshroom (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Zhou, Q.-Y.; Park, J.; Koltun, V. Open3D: A Modern Library for 3D Data Processing. arXiv 1801, arXiv:1801.09847v1. [Google Scholar]

- SDK 3.0 User Guide ROBOMASTER TT 2021. Available online: https://dl.djicdn.com/downloads/RoboMaster+TT/Tello_SDK_3.0_User_Guide_en.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Hodge, V.J.; Hawkins, R.; Alexander, R. Deep reinforcement learning for drone navigation using sensor data. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 2015–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Ho, H.W. Mobile Robot Navigation Based on Noisy N-Step Dueling Double Deep Q-Network and Prioritized Experience Replay. Electronics 2024, 13, 2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinyals, O.; Babuschkin, I.; Czarnecki, W.M.; Mathieu, M.; Dudzik, A.; Chung, J.; Choi, D.H.; Powell, R.; Ewalds, T.; Georgiev, P.; et al. Grandmaster level in StarCraft II using multi-agent reinforcement learning. Nature 2019, 575, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Yuan, B.; Tomizuka, M. Model-free Deep Reinforcement Learning for Urban Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference, Auckland, New Zealand, 27–30 October 2019; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8917306 (accessed on 19 September 2024).

| Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| State Size | 2 | Dimension of the input state, defined by the distance to the current position and the deviation from the desired distance. |

| Action Size | 6 | The number of possible actions, corresponding to adjustments in polar coordinates centered on the closest point of the object. |

| Gamma | 0.95 | Discount factor for future rewards, typically set between 0.9 and 1.0. |

| Epsilon | 1 | Initial exploration probability for random action selection versus policy-based exploitation. |

| Minimum Epsilon | 0.01 | Lower limit for exploration probability. |

| Epsilon Decay | 0.9992 | Rate at which epsilon decreases per episode to gradually reduce exploration. |

| Optimizer | Adam | Optimization algorithm used by the neural network. |

| Learning Rate | 0.001 | Learning rate for the Adam optimizer. |

| Memory Size | 2000 | Maximum number of episodes stored in the replay buffer. |

| Tau | 0.1 | Soft update parameter for the target model. |

| Alpha | 0.6 | Exponent for sample prioritization in experience replay. |

| Component | Details |

|---|---|

| OS | Pop! OS 22.04 LTS x86_64 (Linux family OS) |

| Kernel | 6.0.12 |

| Shell | bash 5.1.16 |

| CPU | Intel i7-6950X (20) @ 4.100GHZ |

| GPU | NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1080 8 GB |

| RAM | 16 GB |

| Network card | TP-LINK TL-WN722N |

| Compilers | gcc-9 y nvcc (CUDA Toolkit 11.3) |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Training Episodes | 2500 |

| Maximum Steps per Episode | 500 |

| Training Time | ~10 h |

| Hardware | Shown in Table 2 |

| Action Space | Discrete (polar coordinates) |

| Reward Function | Distance-based reward |

| Maximum Cumulative Reward Achieved | ~5000 (episode 2480) |

| Scenarios Used | Eight distinct 2D geometric shapes |

| Batch Size (number of experiences used each time it passes through the learning function) | 32 |

| Command | Description | Possible Response |

|---|---|---|

| takeoff | Auto take off | ok/error |

| land | Auto landing | |

| streamon | Turn on the video stream. | |

| streamoff | Turn off the video stream. | |

| up x | Fly upward by x cm. x = 20–500 | ok/error + error status |

| left x | Fly leftward by x cm. x = 20–500 | |

| right x | Fly rightward by x cm. x = 20–500 | |

| cw x | Rotate clockwise by x°. x = 1–360 | |

| ccw x | Rotate counterclockwise by x°. x = 1–360 | |

| speed x | Set the current speed to x cm/s. x = 10–100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Soriano, J.; Rojo-Gala, M.Á.; Pérez-Pérez, G.; Bemposta Rosende, S.; Gordo-Herrera, N. Optimized Autonomous Drone Navigation Using Double Deep Q-Learning for Enhanced Real-Time 3D Image Capture. Drones 2024, 8, 725. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones8120725

Sánchez-Soriano J, Rojo-Gala MÁ, Pérez-Pérez G, Bemposta Rosende S, Gordo-Herrera N. Optimized Autonomous Drone Navigation Using Double Deep Q-Learning for Enhanced Real-Time 3D Image Capture. Drones. 2024; 8(12):725. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones8120725

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Soriano, Javier, Miguel Ángel Rojo-Gala, Guillermo Pérez-Pérez, Sergio Bemposta Rosende, and Natalia Gordo-Herrera. 2024. "Optimized Autonomous Drone Navigation Using Double Deep Q-Learning for Enhanced Real-Time 3D Image Capture" Drones 8, no. 12: 725. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones8120725

APA StyleSánchez-Soriano, J., Rojo-Gala, M. Á., Pérez-Pérez, G., Bemposta Rosende, S., & Gordo-Herrera, N. (2024). Optimized Autonomous Drone Navigation Using Double Deep Q-Learning for Enhanced Real-Time 3D Image Capture. Drones, 8(12), 725. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones8120725