Abstract

During the past several decades, there have been many reports of sightings of the ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilus principalis), but nobody has managed to obtain a clear photo, which is regarded as the standard form of evidence for documenting birds. A study was conducted in the Pearl River swamp in southeastern Louisiana to test the feasibility of searching for this elusive species and surveying its habitat using a DJI Phantom 3 Professional drone with a 4 K video camera. Drone images are of much higher quality than images that were previously obtained at much greater expense during flights in a Cessna 172. The approach was found to be effective for searching for and inspecting trees that are potential foraging sites for woodpeckers and that might be suitable for nest and roost cavities. Large woodpeckers in flight are identifiable in video footage obtained from an altitude of 40 m, which was found to be sufficient to reliably avoid collisions with trees in the study area.

1. Introduction

The ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) is an exceptionally elusive species that has been thought to be extinct only to be rediscovered several times during the past hundred years [1,2,3]. The most recent rediscovery in Arkansas [4] motivated searches in Florida and Louisiana, where additional sightings were reported [5,6,7], but the issue became controversial when nobody managed to obtain a clear photo, which is regarded as the standard form of evidence for documenting birds. An analysis based on factors related to habitat and behavior suggests that the expected waiting time for obtaining such evidence for the persistence of the ivory-billed woodpecker is several orders of magnitude greater than it would be for a more typical baseline species of comparable rarity [7]. These factors include the wariness of the ivory-billed woodpecker (which is documented in historical accounts), the vastness of its habitats (typically covering several tens of square kilometers), the difficulty of moving along a search path in its habitats (which contain thick vegetation, waterways and flooded areas) and the lack of visibility in a forest (typically limited to a few tens of meters).

During searches that were carried out in the previous decade, attempts to document this species involved strategies such as drifting through appropriate habitat in a kayak, observing from a vantage point that provides a view out over the treetops and deploying autonomous cameras and audio recorders. The feasibility of searching for the ivory-billed woodpecker and surveying its habitat with a drone is explored here. With this approach, it is possible to cover a much larger area per unit time than can be covered by a single person on the ground. A drone provides an unobstructed view when the camera is aimed over the treetops, and the view of the dorsal field marks of a bird in flight is favorable when the camera is aimed downward. By tilting the camera slightly forward from vertical, it may be possible to obtain video footage of a wary bird that flushes as the drone approaches.

One of the potential uses of a drone would be to search for signs of foraging that are consistent with the ivory-billed woodpecker, which has a massive bill that gives it an advantage over other woodpeckers within its range in accessing rich food sources beneath tightly adhered bark [5]. Shortly before a sighting in 2008 that is supported by video evidence [7], several trees that had recently been stripped of bark were discovered in the area. When the leaves are down in winter, a drone could be used to rapidly survey a vast tract of hardwoods for such foraging sites. This approach could be used to assess an area for the presence of the ivory-billed woodpecker prior to beginning a dedicated search effort. A drone is capable of providing detailed images of individual trees, which could reveal foraging patterns that seem to be inconsistent with other woodpeckers and/or are suggestive of the ivory-billed woodpecker, such as the examples appearing in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(Left) Unusual pattern of bark stripping in a photo obtained by James Tanner in 1939 during a study near the last known nest sites of the ivory-billed woodpecker (this photo is in the possession of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service); (Right) A similar foraging pattern appears in a photo that was obtained by the author just to the east of the Pearl River in Mississippi.

2. Materials and Methods

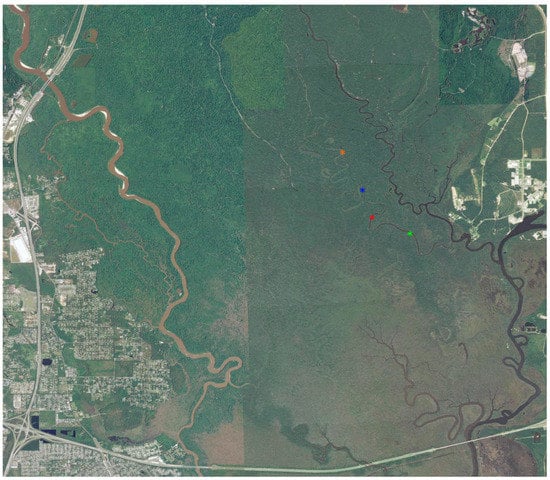

The study involved more than a hundred flights with a DJI Phantom 3 Professional drone, which has a 4K video camera with an f/2.8 lens and a gimbal mount for stability. The DJI GO application [8] was used during manually-controlled flights. The Litchi application [9] was used during autonomous flights, which were done at a cruising speed of 8 m/s. Appearing in Figure 2 is an image of the main study area in the Pearl River swamp in southeastern Louisiana, where sightings of ivory-billed woodpeckers have been reported since the 1990s. Relatively few trees exceed 30 m in this habitat, which has only small variations in elevation, and there are many sites where a drone may be launched and landed that provide access to most of the hardwood zone, which is the preferred foraging habitat of the ivory-billed woodpecker. Additional flights were done in the Choctawhatchee and Apalachicola River swamps in Florida and in the swamp that lies between the Mobile and Tensaw Rivers in Alabama.

Figure 2.

National Agriculture Imagery Program image of the study area in the Pearl River swamp in Louisiana. Asterisks mark the locations of encounters with ivory-billed woodpeckers [7]. Green: first sighting in 2006. Red: six sightings and video evidence obtained along a short segment of English Bayou later in 2006. Orange: first sighting in 2008. Blue: sighting and video evidence obtained later in 2008. North is up. The area shown is 12 km × 12 km.

3. Results

The initial focus of the study was to survey habitat with manually-controlled flights. Images obtained with this approach are of much higher quality than images that were previously obtained (at much greater expense) by the author during flights in a Cessna 172 (at much higher altitudes, without a gimbal to stabilize the camera and with a restricted view from inside the aircraft). The drone image of habitat appearing in Figure 3 shows the bayou where the author had sightings in 2006 and 2008 and dead trees that are potential foraging sites for woodpeckers. Additional drone images of habitat in the main study area appear in Figures S1–S5. Drone images of habitat in the Choctawhatchee and Apalachicola swamps appear in Figures S6–S11. Areas that have been logged are visible in an image of the Mobile-Tensaw swamp in Figure 4, which was obtained from high altitude. The drone images in Figures S12–S14 provide a better view of the impact of logging in that river basin. Appearing in Figure 5 is an example that illustrates how discolored leaves can make it easy to locate a potential foraging tree with a drone during the summer. Appearing in Figures S15–S19 are some of the many possible foraging trees that were discovered during the winter. In part of its range, the ivory-billed woodpecker is known to nest and roost in cypress trees. The drone was used to inspect large cypresses (some that exceed 30 m) appearing in Figure 6, which are part of an extensive grove located in the lower half of the area appearing in Figure 2.

Figure 3.

View of the Pearl River swamp that shows part of English Bayou and dead trees that are potential woodpecker foraging sites.

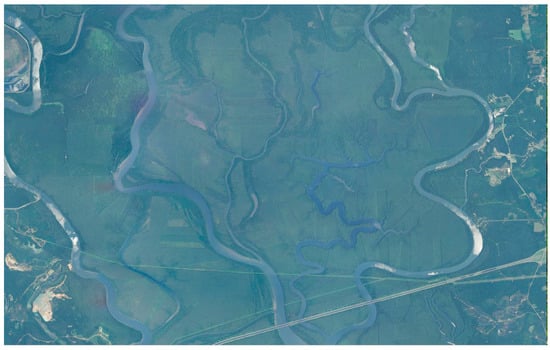

Figure 4.

National Agriculture Imagery Program image of the swamp that lies between the Mobile and Tensaw Rivers in Alabama. There are many rectangular areas that have been logged. North is up. The area shown is 13 km × 10 km.

Figure 5.

A tree with discolored leaves (that had recently been killed by lightning) stands out among the surrounding trees in this image.

Figure 6.

Part of a grove of large cypresses (some that exceed 30 m) that is located to the south of the hardwood zone in the Pearl River Wildlife Management Area.

Most of the manually-controlled flights were done at 120 m in order to optimize transmissions between the controller and the drone. It was found that even large birds are difficult to identify in video footage from that altitude. The Litchi application makes it easy to do flights at lower altitudes along prescribed routes. Factors that were considered in selecting the cruising altitude include the heights of potential obstacles, uncertainties in GPS navigation and the need to resolve field marks in the video. It was found that 40 m is a sufficient cruising altitude to avoid collisions with trees in the main study area while at the same time providing video footage in which large birds are identifiable. Video footage of pileated woodpeckers (Dryocopus pileatus) that was obtained during the study appears in Movies S1 and S2. Those birds are easily identified on the basis of the overall black plumage, small white patches on the dorsal surfaces of the wings and flap style in which the wings are folded closed during the middle of each upstroke. From comparable video footage, it would be easy to identify an ivory-billed woodpecker, which is slightly larger and has prominent white patches that extend along the trailing edges of the dorsal surfaces of the wings.

4. Discussion

The 94 degree lens of the video camera covers a swath that is about 80 m wide from an altitude of 40 m. Four square kilometers of habitat could therefore be covered with ten flights of 5 km, which could be done in about two hours at 8 m/s. On the ground, it can take a few hours to follow a search path for just a few kilometers through the dense vegetation and flooded areas in such habitats. It would take only a few days for a small team of drone operators to search tens of square kilometers for signs of foraging and assess the area for the presence of ivory-billed woodpeckers. When there are indications that ivory-billed woodpeckers are present, dedicating resources to a large number of search missions might eventually pay off with a favorable encounter similar to the ones involving pileated woodpeckers in Movies S1 and S2. In order to fully exploit the capability of a drone for this application, one would need to acquire a permit to fly missions beyond the line of sight over the remote and uninhabited habitats that are appropriate for ivory-billed woodpeckers. Another possible approach would be to launch missions from vantage points that provide views out to long ranges. There are many trees within the main study area that could serve this purpose, including some that have been used as observation platforms [7]. The unobstructed view from 24 m up one of those trees appears in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

View from 24 m up a tree in the Pearl River swamp from which a drone would remain in view out to longer ranges than it would to an operator on the ground.

5. Conclusions

One approach for reducing the expected waiting time for documenting an elusive species is to increase the rate of data acquisition. In habitats that are appropriate for ivory-billed woodpeckers, it is possible to cover a much greater area per unit time with a drone than a person can cover on the ground, and a drone continuously obtains high-quality video footage from a favorable vantage point. A drone also has advantages over other approaches for surveying habitat. A drone can be used to obtain wide views of habitat from 120 m and close-ups from lower altitudes that reveal cavities and signs of foraging. Few trees in lowland swamp forests exceed 30 m, and a cruising altitude of 40 m was found to be safe within the main study area. At that altitude and a cruising speed of 8 m/s, it was found that 4 K video provides sufficient resolution for identifying large woodpeckers.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/2504-446X/2/1/11/s1, Figures S1–S5: Drone images of habitat in the Pearl River swamp in Louisiana, Figures S6–S8: Drone images of habitat in the Choctawhatchee River swamp in Florida, Figures S9–S11: Drone images of habitat in the Apalachicola River swamp in Florida, Figures S12–S14: Drone images of habitat in the swamp that lies between the Mobile and Tensaw Rivers in Alabama, Figures S15–S19: Images of possible foraging trees in the Pearl River swamp in Louisiana, Movies S1 and S2: Video footage of pileated woodpeckers in flight that was obtained from a drone flying at 8 m/s and an altitude of 40 m over the Pearl River swamp (it is best to view these 4 K videos on a computer with a large monitor).

Acknowledgments

The author is a scientist at the Naval Research Laboratory, but the work was privately funded.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Jackson, J.J. In Search of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker; Smithsonian: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, T. The Grail Bird: Hot on the Trail of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: Boston, MA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, G.E. Ivorybill Hunters, the Search for Proof in a Flooded Wilderness; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, J.W.; Lammertink, M.; Luneau, M.D.; Gallagher, T.W.; Harrison, B.R.; Sparling, G.M.; Rosenberg, K.V.; Rohrbaugh, R.W.; Swarthout, E.C.; Wrege, P.H.; et al. Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) persists in Continental North America. Science 2005, 308, 1460–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, G.E.; Mennill, D.J.; Rolek, B.W.; Hicks, T.L.; Swiston, K.A. Evidence suggesting that Ivory-billed Woodpeckers (Campephilus principalis) exist in Florida. Avian Conserv. Ecol. 2006, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.D. Putative audio recordings of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis). J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2011, 129, 1626–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, M.D. Video evidence and other information relevant to the conservation of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis). Heliyon 2017, 3, e00230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.dji.com/goapp (accessed on 24 February 2018).

- Available online: https://flylitchi.com (accessed on 24 February 2018).

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).