Efficacy of Drone-Applied Fungicide Treatments in Control of Sunflower Diseases

Highlights

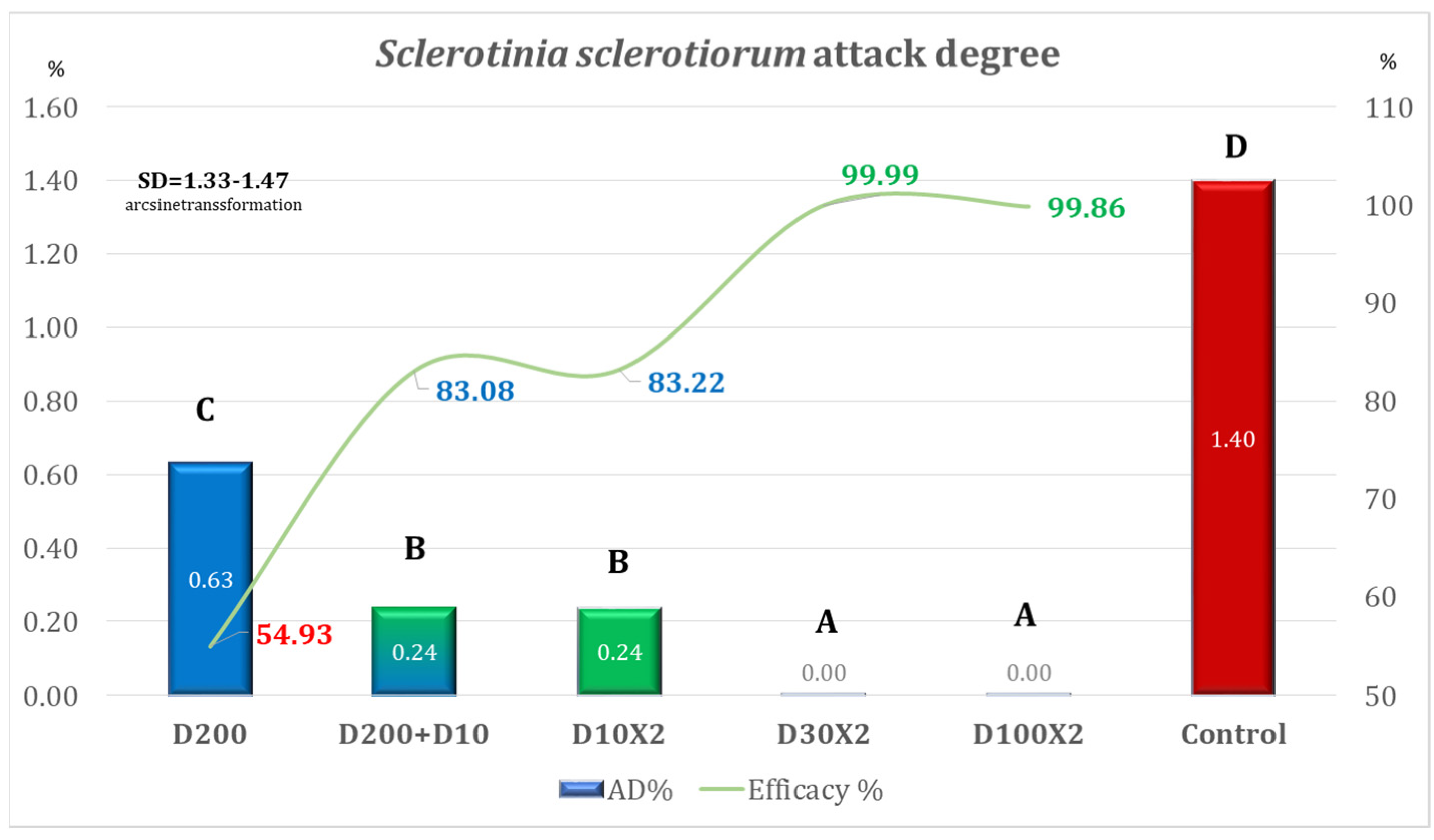

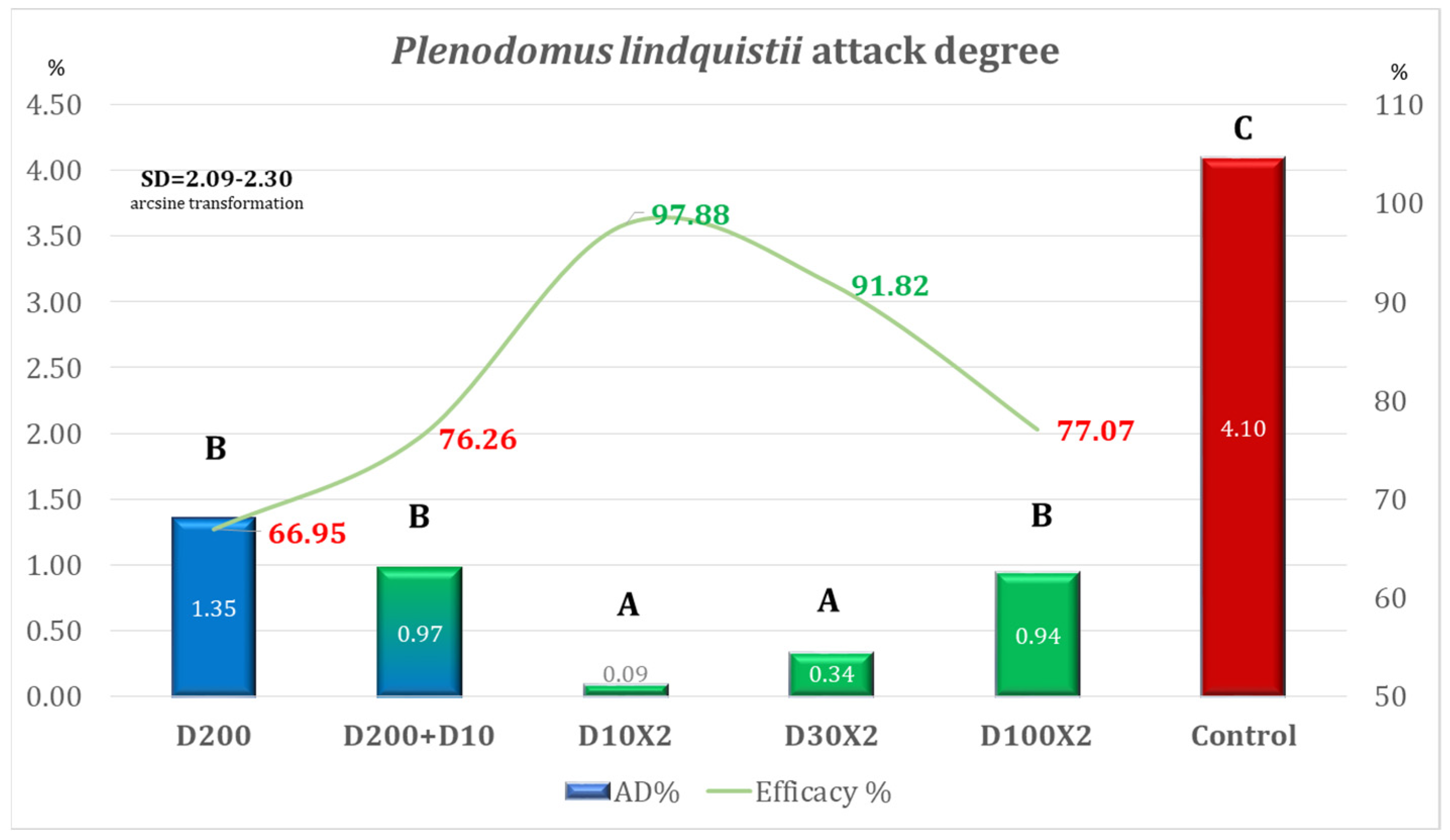

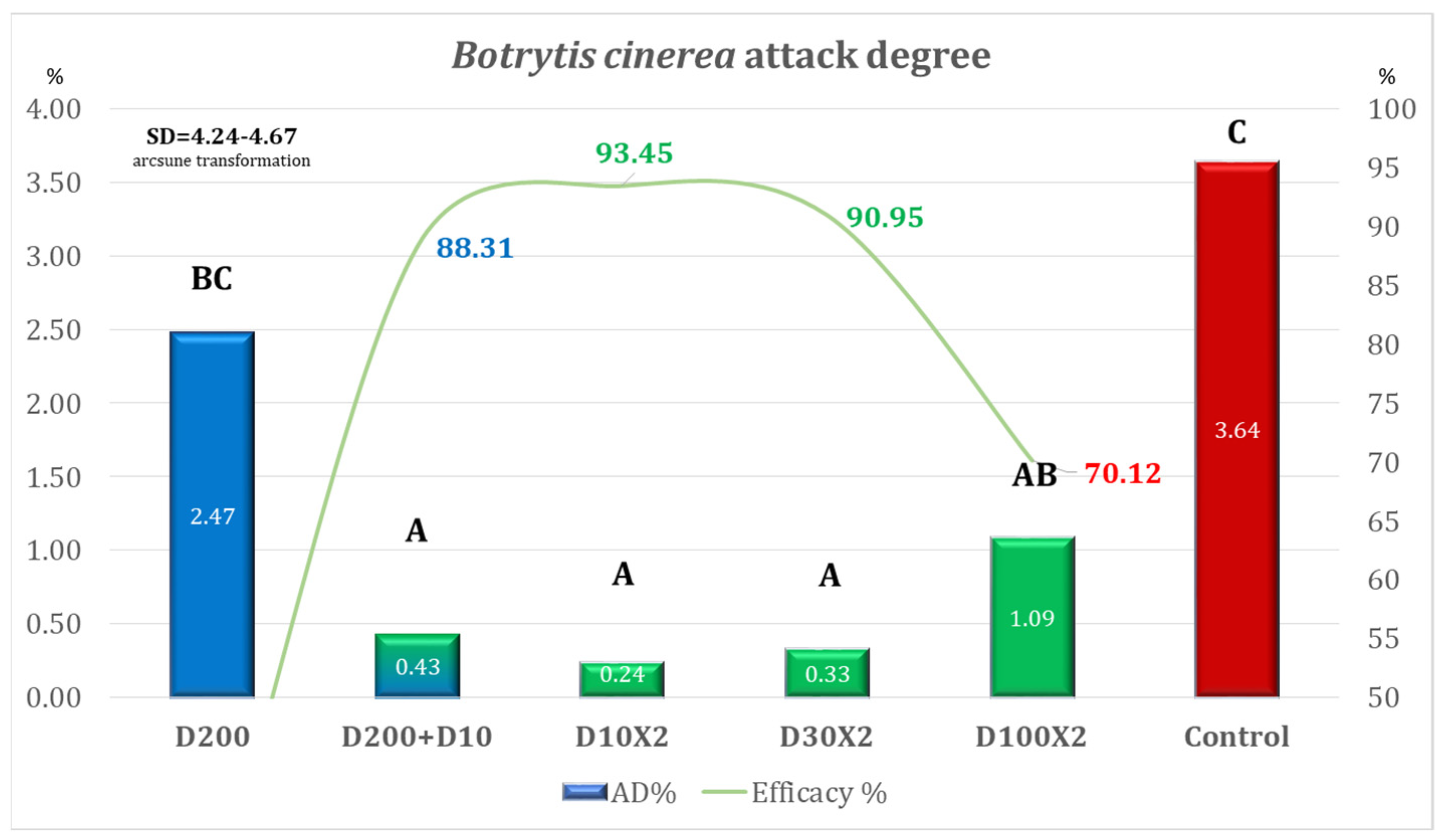

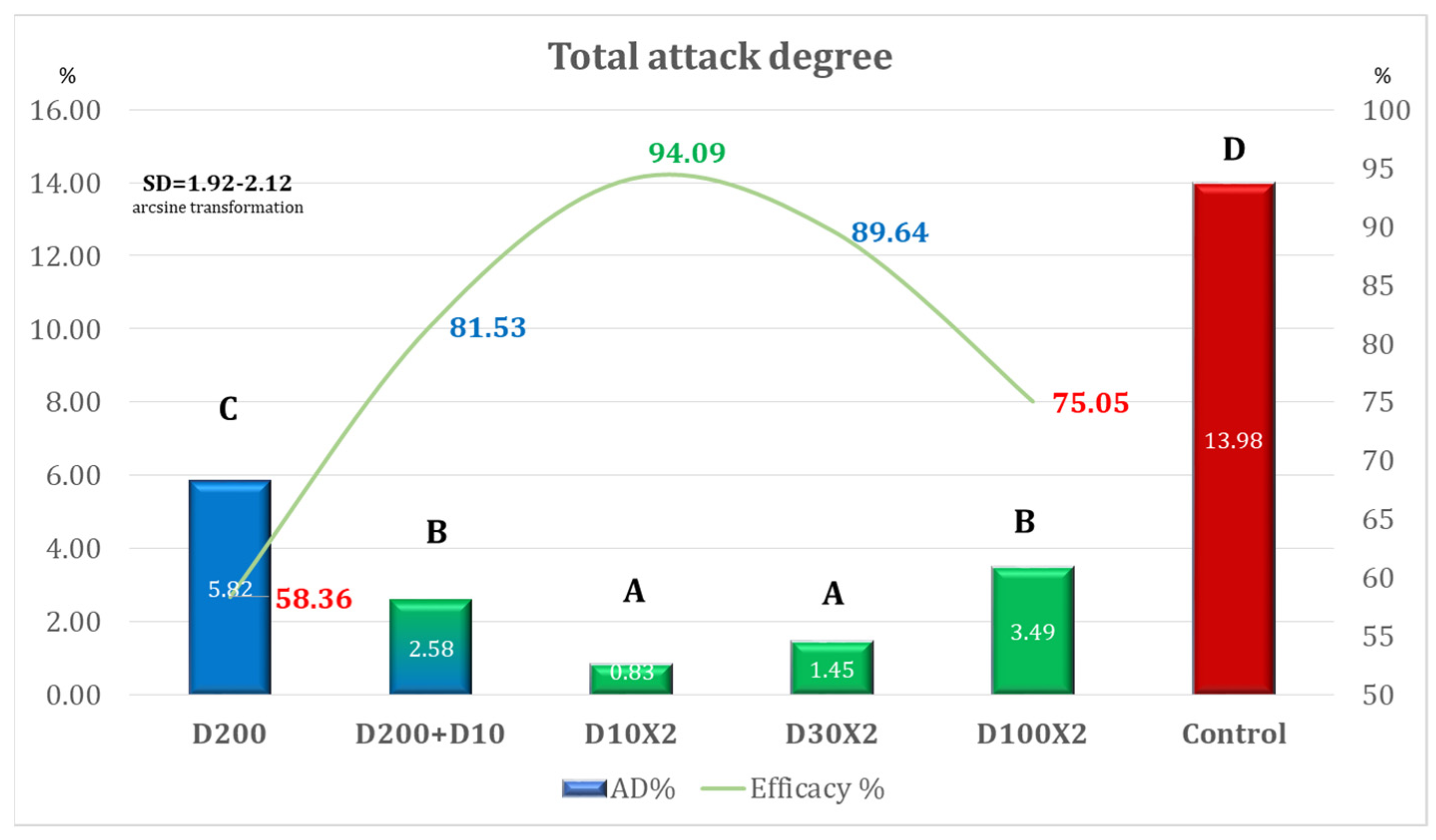

- The use of low (LV) and ultra-low volumes (ULV) in the control of sunflower pathogens shows higher efficiency compared to the application in normal volumes (NV).

- The use of drones in plant protection is a viable alternative with excellent results.

- The increased effectiveness of the treatments, but also the possibility of applying the second treatment to sunflowers, makes our results of genuine interest to farmers and agricultural workers.

- The high efficiency of applying treatments using drones can lead to a reduction in the biological reserve of pathogens, and, why not, through further testing, the amount of pesticides used in agriculture.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Conditions

2.2. Biological Material

2.3. Agriculture Technology Used

2.4. Experimental Design

2.5. Application Equipment Used

3. Results

3.1. After the First Treatment

3.2. After the Second Treatment

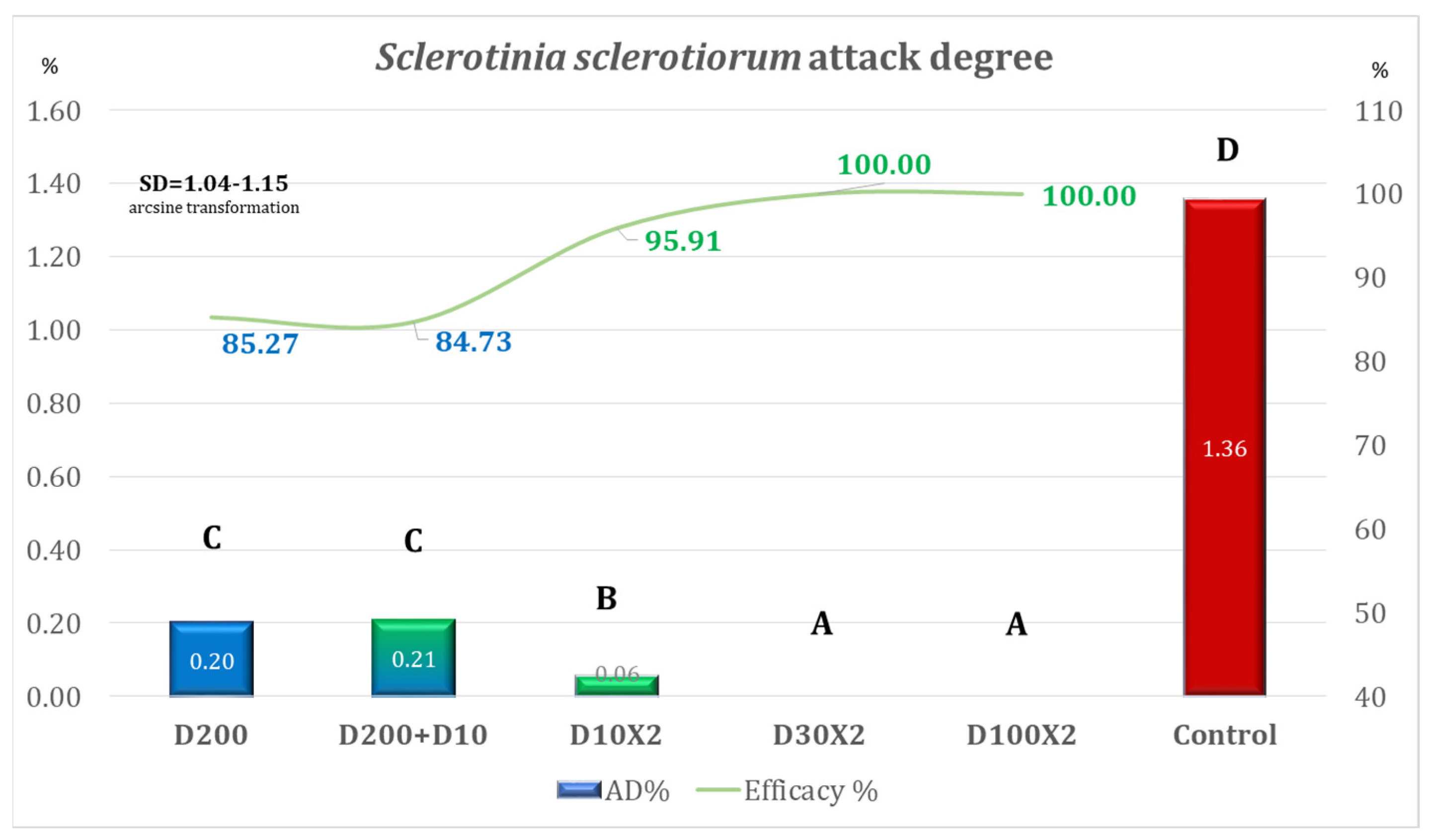

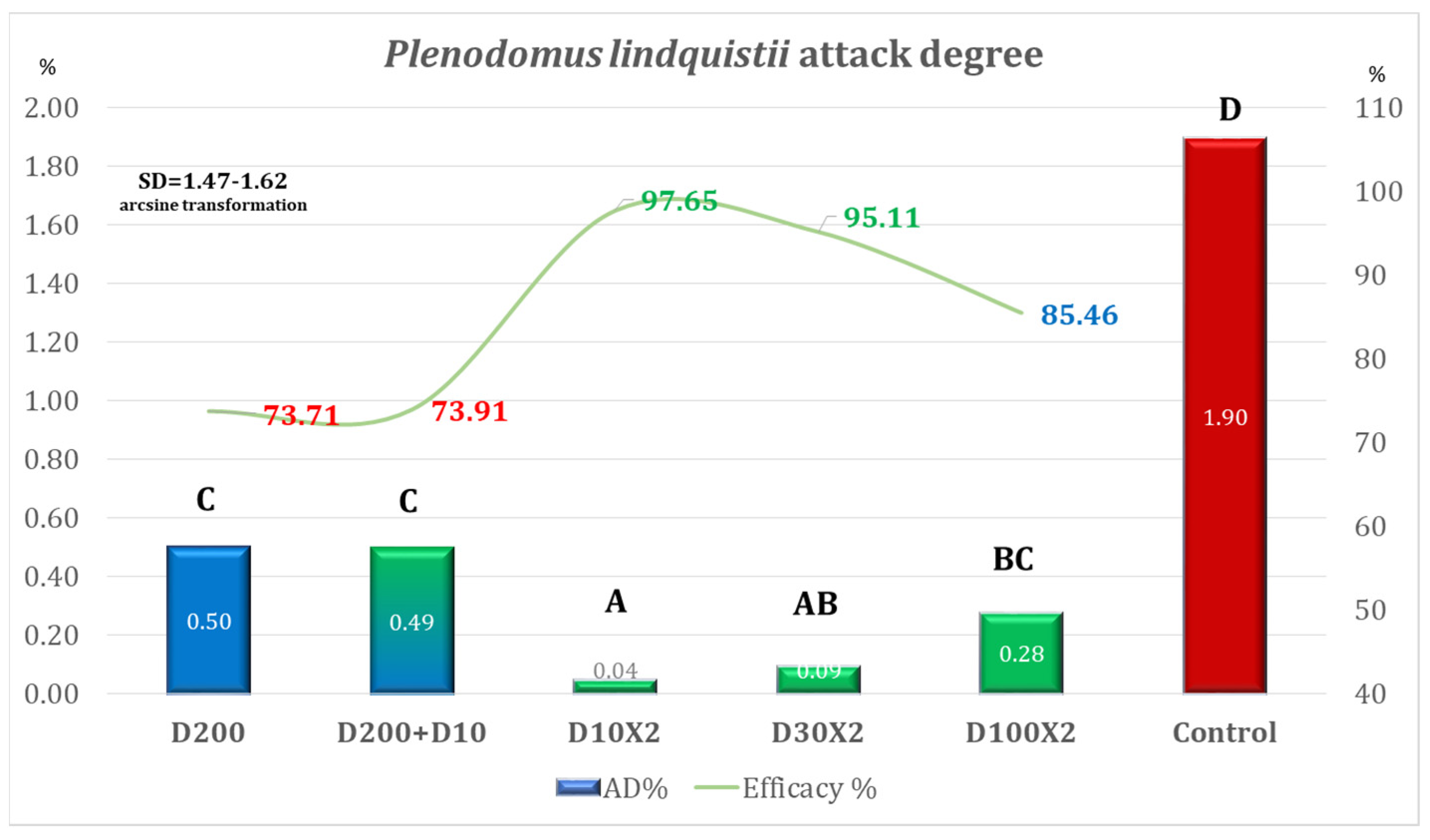

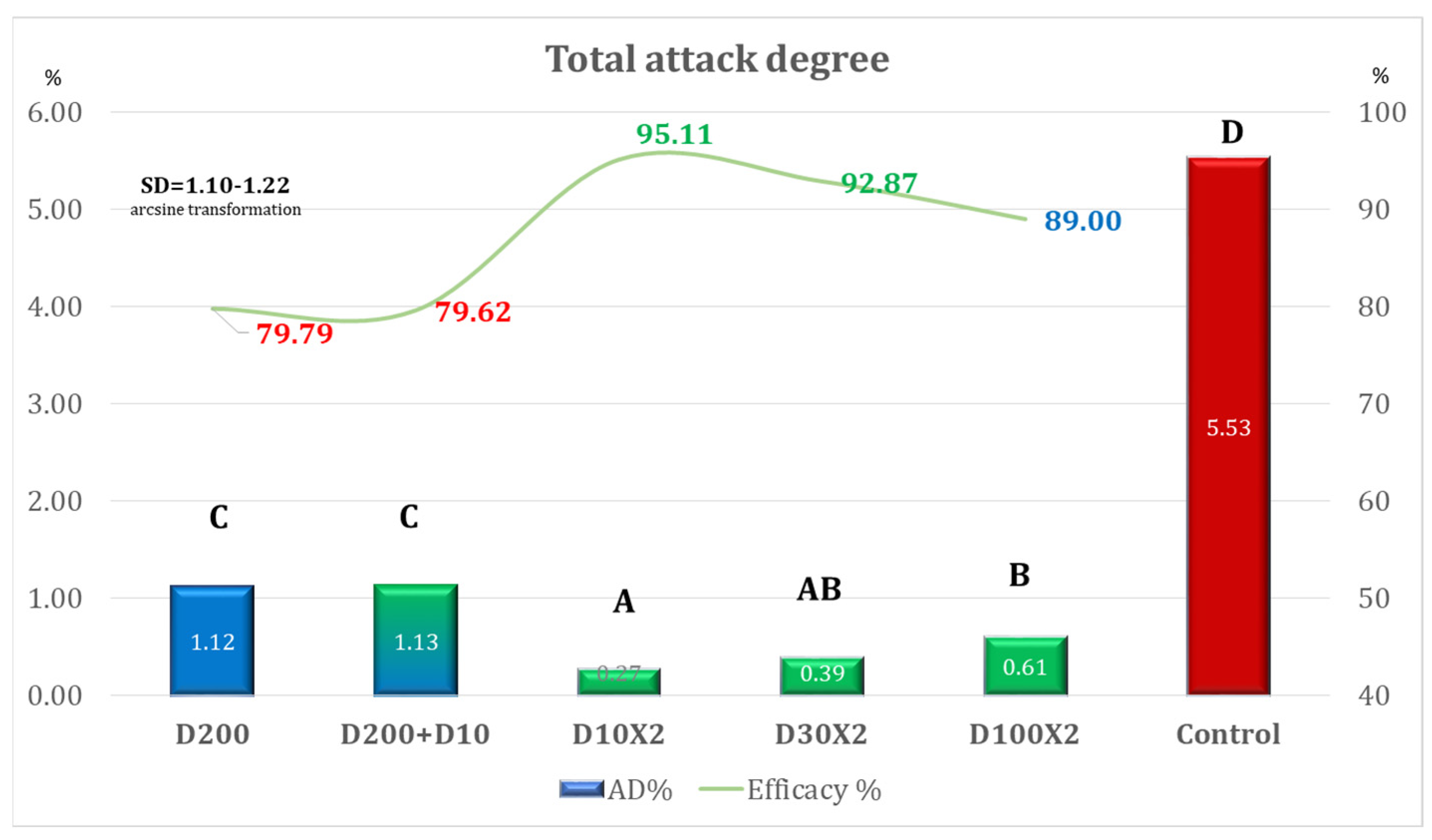

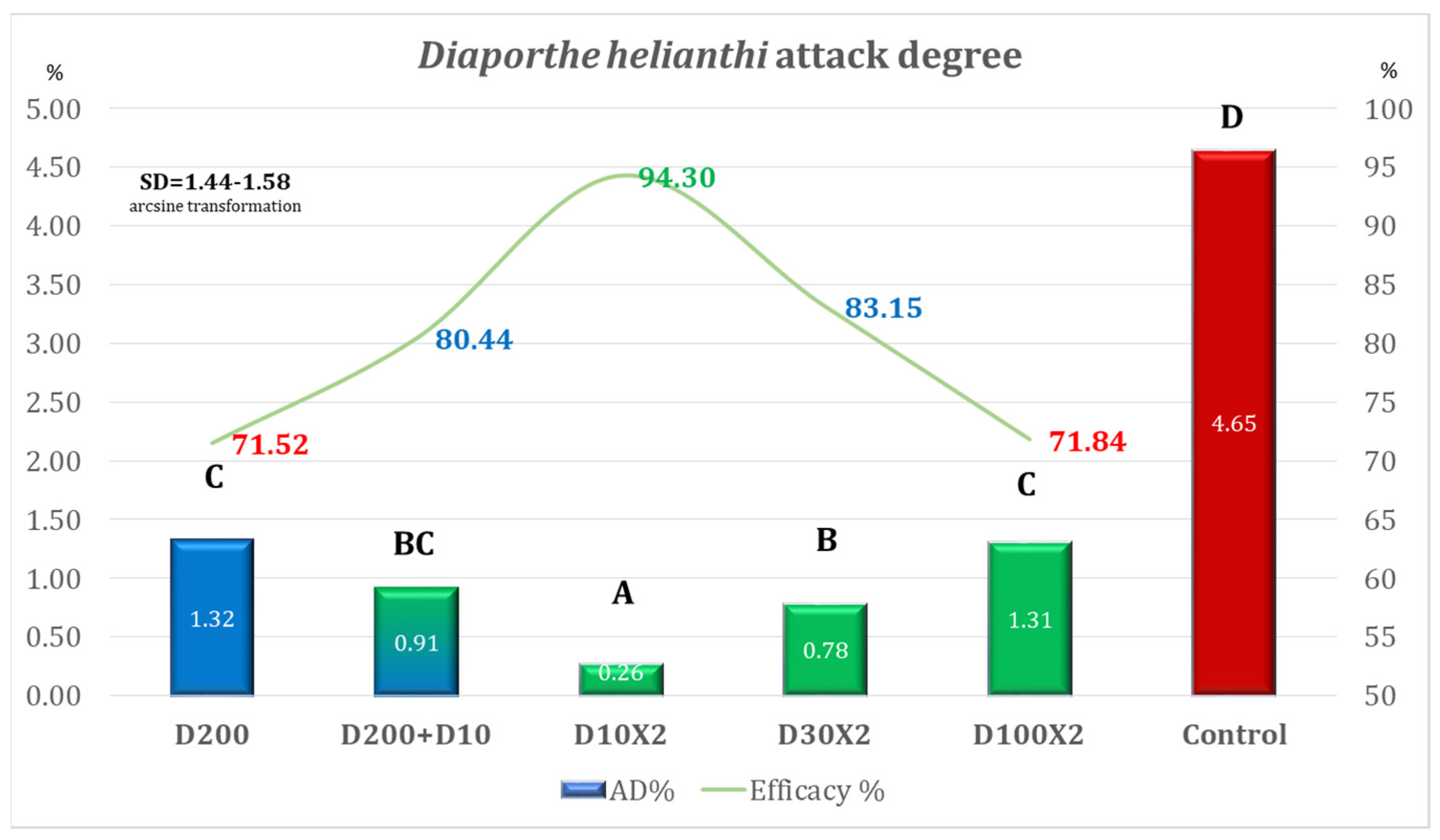

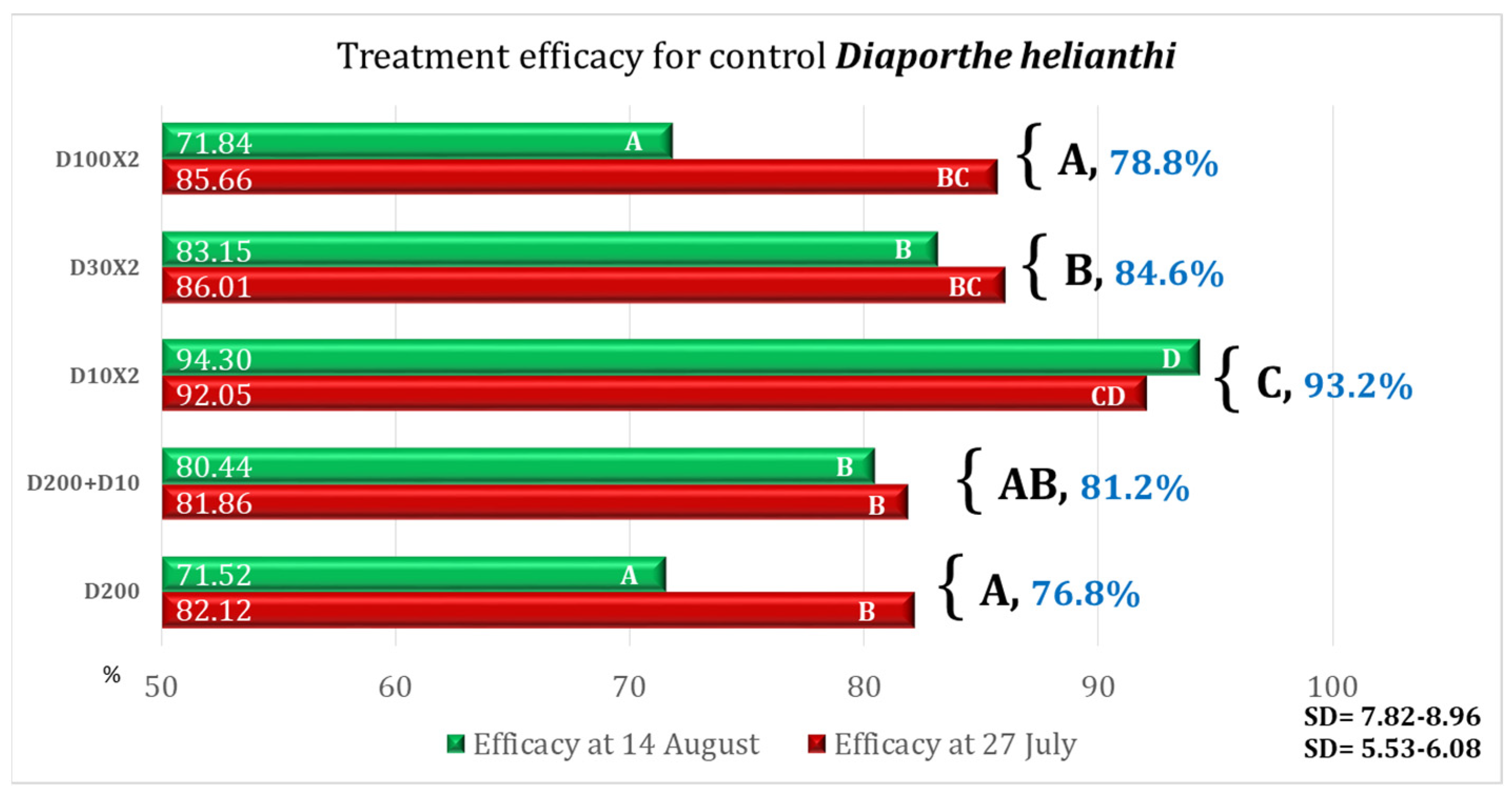

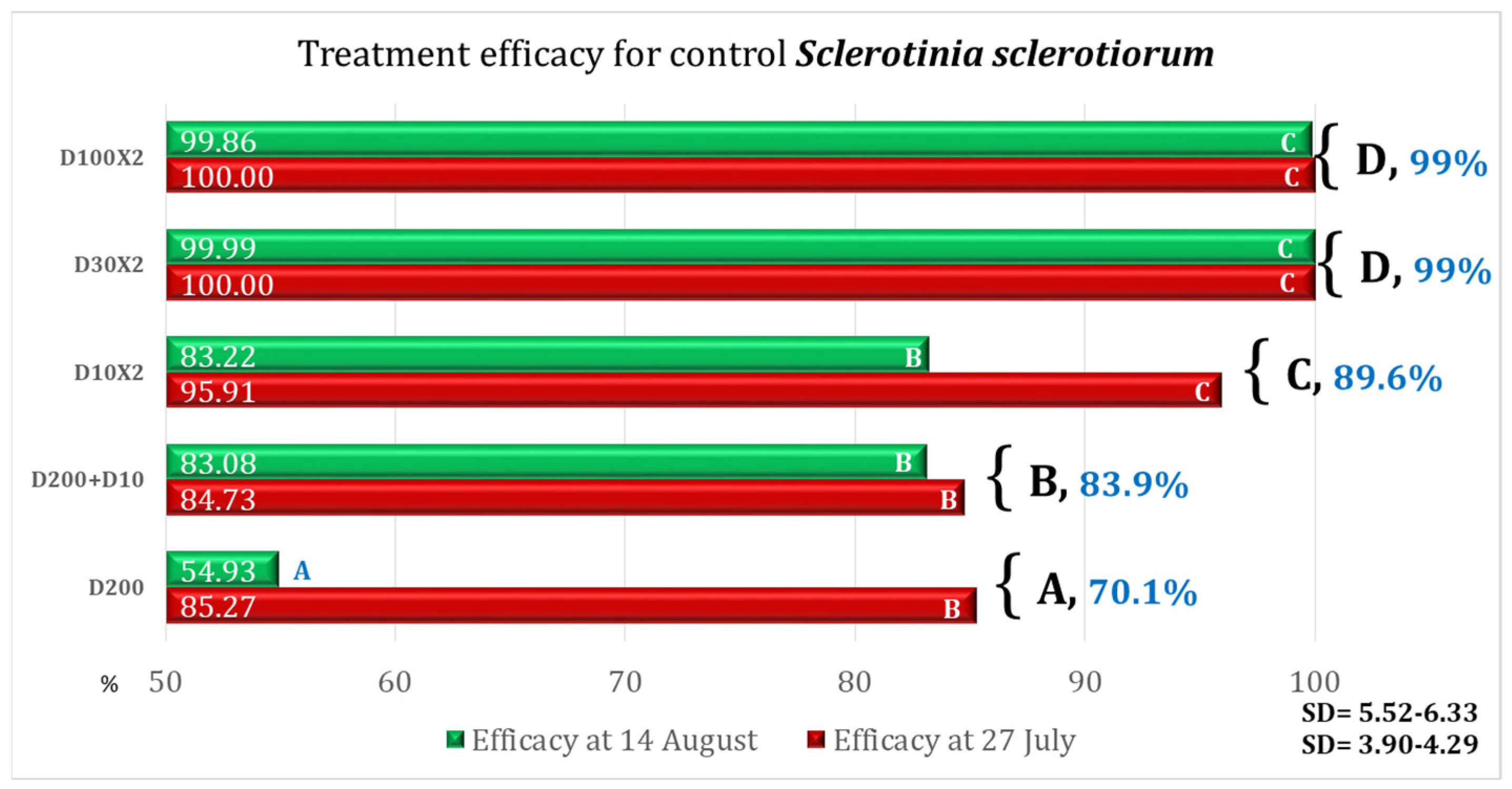

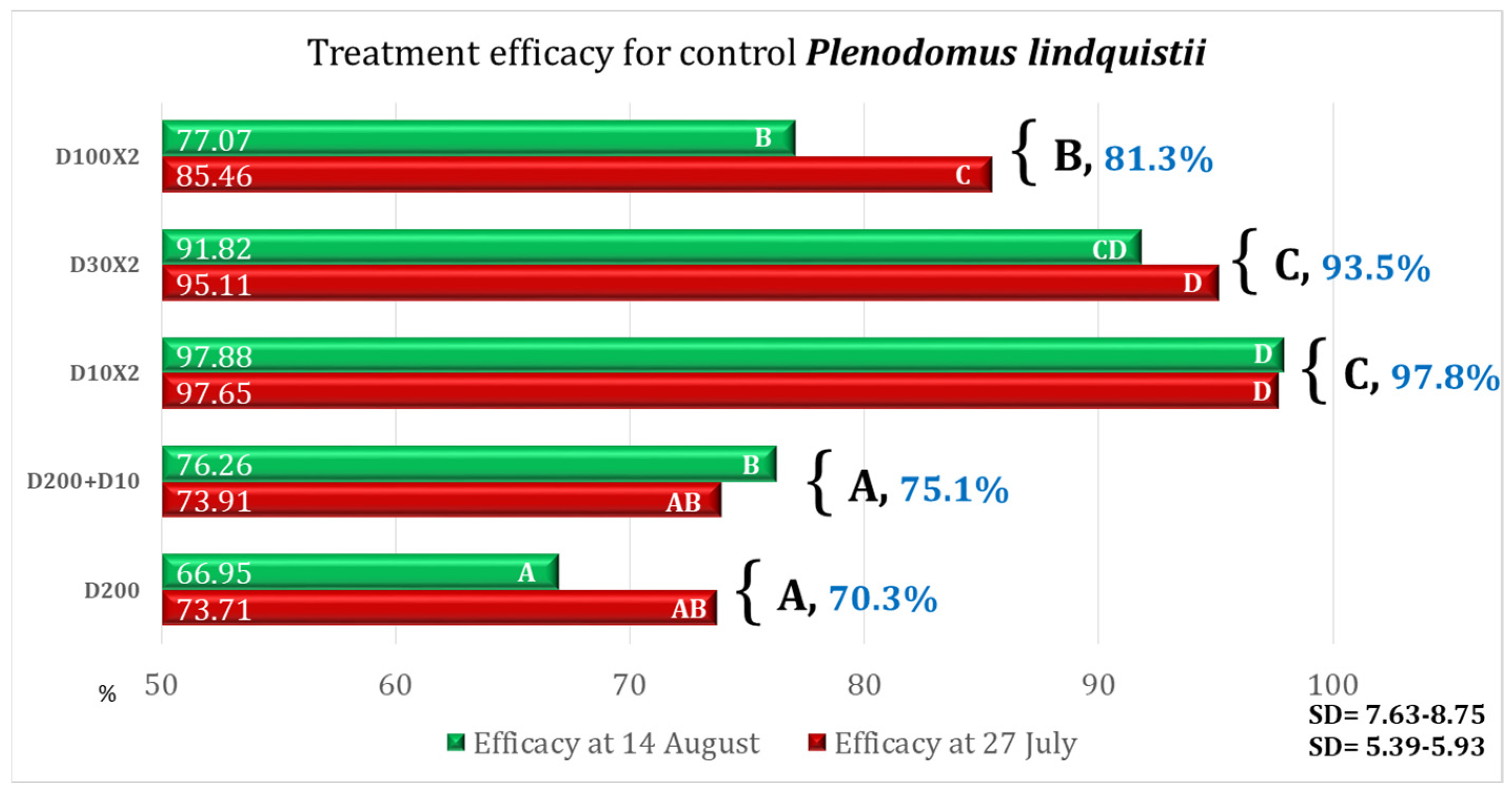

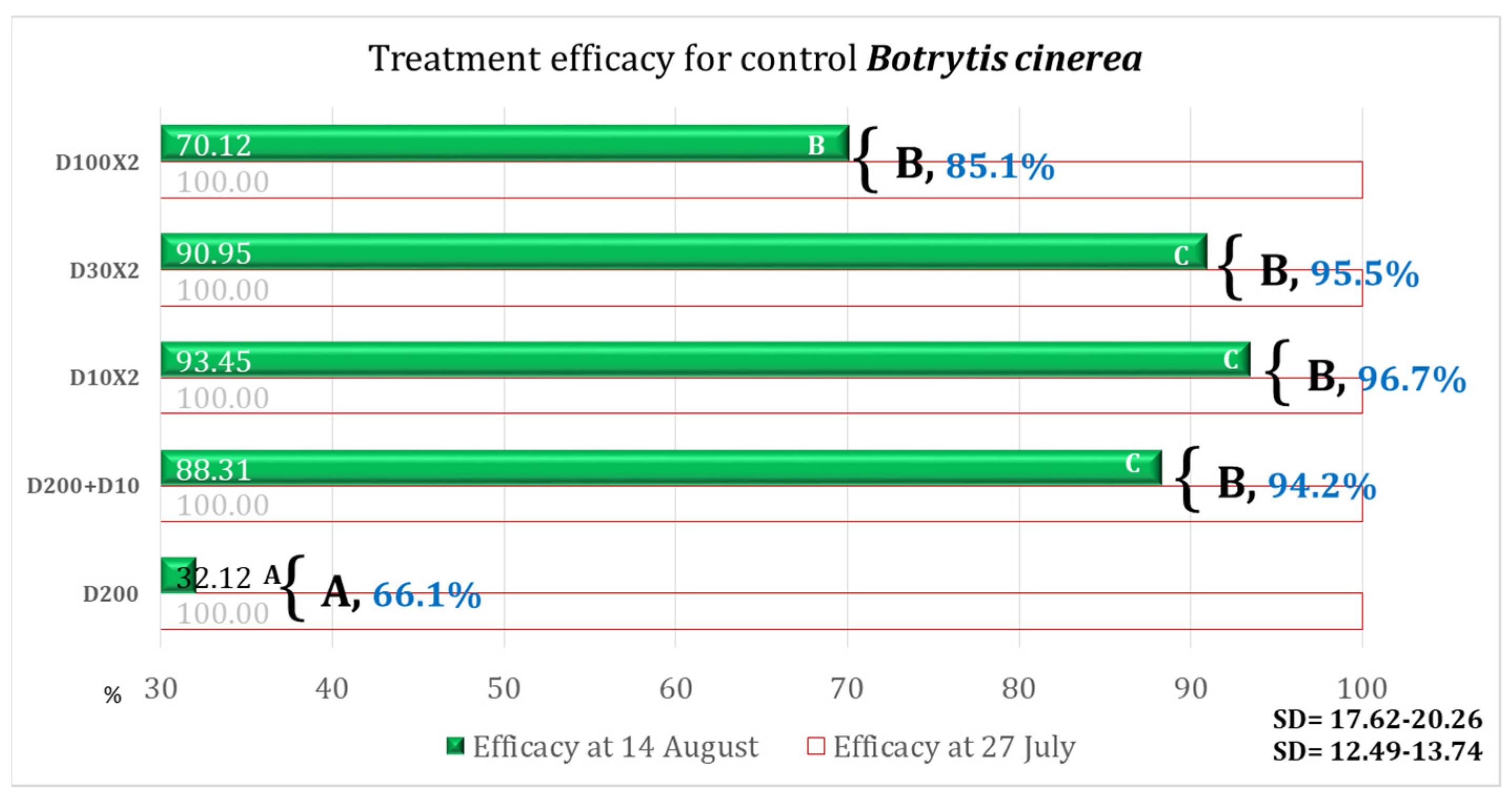

3.3. Treatment Efficacy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cho, Y.; Cho, K.; Shin, C.; Park, J.; Lee, E.-S. An Agricultural Expert Cloud for a Smart Farm. In Future Information Technology, Application, and Service; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.P. Internet of Things for Smart Agriculture: Technologies, Practices and Future Direction. J. Ambient Intell. Smart Environ. 2017, 9, 395–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K. Application of Plant Protection Products by Helicopter in Germany (Legislation, Requirements, Guidelines, Use in Vineyards and Forests, Drift). EPPO Bull. 1996, 26, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuping, F.; Yu, R.; Chenming, H.; Fengbo, Y. Planning of Takeoff/Landing Site Location, Dispatch Route, and Spraying Route for a Pesticide Application Helicopter. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 146, 126814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klauser, F.; Dennis Pauschinger, D. Entrepreneurs of the Air: Sprayer Drones as Mediators of Volumetric Agriculture. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 84, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, D.; Hussin, N.; Shahibi, M.S.; Ahmad, M.; Hashim, H.; Ametefe, D.S. A Systematic Review on the Factors Governing Precision Agriculture Adoption among Small-Scale Farmers. Outlook Agric. 2023, 52, 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C. Integrated Open Geospatial Web Service Enabled Cyber-Physical Information Infrastructure for Precision Agriculture Monitoring. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2015, 111, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, J.; Casalini, F.; Griffin, T.; Antón, J. The digitalisation of agriculture: A literature review and emerging policy issues. In OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantalaki, N.; Souravlas, S.; Roumeliotis, M. Data-Driven Decision Making in Precision Agriculture: The Rise of Big Data in Agricultural Systems. J. Agric. Food Inf. 2019, 20, 344–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, F. Sounding the Alarm for Digital Agriculture: Examining Risks to the Human Rights to Science and Food. Neth. Q. Hum. Rights 2024, 42, 276–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garske, B.; Bau, A.; Ekardt, F. Digitalization and AI in European Agriculture: A Strategy for Achieving Climate and Biodiversity Targets? Sustainability 2021, 13, 4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anam, I.; Arafat, N.; Hafiz, M.S.; Jim, J.R.; Kabir, M.M.; Mridha, M.F. A Systematic Review of UAV and AI Integration for Targeted Disease Detection, Weed Management, and Pest Control in Precision Agriculture. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 9, 100647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y. Satellite- and Drone-Based Remote Sensing of Crops and Soils for Smart Farming—A Review. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 66, 798–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeginis, D.; Kalampokis, E.; Palma, R.; Atkinson, R.; Tarabanis, K. A Semantic Meta-Model for Data Integration and Exploitation in Precision Agriculture and Livestock Farming. Semant. Web 2023, 15, 1165–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachenheim, C.; Fan, L.; Zheng, S. Adoption of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles for Pesticide Application: Role of Social Network, Resource Endowment, and Perceptions. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, A.; Pullanagari, R.; Alani, N.H.S.; Al-Rawi, M.; Fouzia, S.; Berger, B. Drones-of-The-Future in Agriculture 5.0—Automation, Integration, and Optimisation. Agric. Syst. 2025, 231, 104543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafinelli, E. Life of Drone Visuals: Norms, Ethics, and Effects. In Theorising Drones in Visual Culture: Views from the Blue; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 119–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostis, I.; Kotzanikolaou, P.; Douligeris, C. Understanding and Securing the Risks of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Services. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 47955–47995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guebsi, R.; Mami, S.; Chokmani, K. Drones in Precision Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review of Applications, Technologies, and Challenges. Drones 2024, 8, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaeizadeh, A.; Sharifi, I.; Alasty, A.; Ghatrehsamani, S. Agricultural Spraying Drones: A Comprehensive Review. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiz-Rubio, V.; Rovira-Más, F. From Smart Farming towards Agriculture 5.0: A Review on Crop Data Management. Agronomy 2020, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binswanger, H. Agricultural Mechanization. World Bank Res. Obs. 1986, 1, 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, A.; Raza, S. Green Revolution: A Review. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Res. 2018, 3, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lioutas, E.D.; Charatsari, C. Big Data in Agriculture: Does the New Oil Lead to Sustainability? Geoforum 2020, 109, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamata, J.E. Convergence of the Unmanned Aerial Industry. Theor. Econ. Lett. 2017, 7, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, M.N.; Jusoh, M.S.M.; Bakar, B.H.A.; Basri, M.S.H.; Kamal, F.; Ahmad, M.T.; Mail, M.F.; Masarudin, M.F.; Misman, S.N.; Teoh, C.C. Preliminary Study on Pesticide Application in Paddy Field Using Drone Sprayer. Adv. Agric. Food Res. J. 2021, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivezić, A.; Trudić, B.; Stamenković, Z.; Kuzmanović, B.; Perić, S.; Ivošević, B.; Buđen, M.; Petrović, K. Drone-Related Agrotechnologies for Precise Plant Protection in Western Balkans: Applications, Possibilities, and Legal Framework Limitations. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iost Filho, F.H.; Heldens, W.B.; Kong, Z.; de Lange, E.S. Drones: Innovative Technology for Use in Precision Pest Management. J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 113, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berner, B.; Chojnacki, J. Use of Drones in Crop Protection. In Proceedings of the Farm Machinery and Processes Management in Sustainable Agriculture, IX International Scientific Symposium, Lublin, Poland, 22 November 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizhe, Z.; Jie, M.; Wenshen, J.; Hengzhi, Z. Development Prospect of the Plant Protection UAV in China. In Proceedings of the ASABE Annual International Meeting, Spokane, WA, USA, 16–19 July 2017; pp. 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yumnam, C.; Marak, A.B.; Kumar, M.; Khatri, S.; Kumar, S.; Soni, S.; Kabil, K.; Balaji, V.; Sahni, R.K.; Kumar, S.P.; et al. Utilising Drones in Agriculture: A Review on Remote Sensors, Image Processing and Their Application. Mod. Agric. 2025, 3, e70021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- România-Comisia Europeană. agriculture.ec.europa.eu. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/cap-my-country/cap-strategic-plans/romania_ro (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Vang-Pedersen, O. Spraying of apple trees with air mist blower and ultra low volume sprayer with normal and reduced amounts of pesticides. Dan. J. Plant Soil Sci. 1982, 86, 255–295. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, J.; Gaussoin, R.; Eastin, J.; Henry, R.; Kruger, G. Effect of application carrier volume on a conventional sprayer system and an ultra-low volume sprayer. In Proceedings of the 33rd Symposium on Pesticide Formulation and Delivery Systems: “Sustainability: Contributions from Formulation Technology”, Atlanta, GA, USA, 23–25 October 2012; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014; pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Awulu, J.O.; Enokela, J.A.; Shatalis, D.D.; Eng, B. Design and Evaluation of an Electrically Operated Ultra–Low Volume Sprayer. Pac. J. Sci. Technol. 2011, 12, 104–114. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, S.K.; Das Gupta, S.K. Pesticide application skill development series No. 17 International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics. Patancheru 1996, 502, 1113–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitraşcu, A.; Manea, D.; Căsăndroiu, T. The use of dimensional analysis in studying the spraying process through nozzles at phytosanitary treatment machines. INMATEH-Agric. Eng. 2015, 45, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Bán, R.; Kovács, A.; Nisha, N.; Pálinkás, Z.; Zalai, M.; Yousif, A.I.A.; Körösi, K. New and High Virulent Pathotypes of Sunflower Downy Mildew (Plasmopara halstedii) in Seven Countries in Europe. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardare, E.S.; Cristea, S. Researches on the Reaction of Sunflower Hybrids to Fungal Rots Attack. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 208, S108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, A.-M.; Gafencu, A.-M.; Lipșa, F.-D.; Gabur, I.; Ulea, E. A First Report of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum Causing Forsythia Twig Blight in Romania. Plants 2023, 12, 3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, I.; Gurău, L.R. Influence of sowing time on the occurrence of alternaria leaf spot, rust and broomrape on sunflower. Rom. J. Plant Prot. 2023, 16, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draghici, R. Research the influence of treatment plant application on sunflower culture located in sandy soils conditions. Ann. Univ. Craiova—Agric. Mont. Cadastre Ser. 2010, 40, 361–367. [Google Scholar]

- Şerban, M.I.; Florian, V. Health status of some sunflower hybrids during 2019–2021 in Cluj county. Agron. Ser. Sci. Res. 2022, 65, 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Okros, A.; Borcean, A.; Dragoslav, M.V.; Casiana, M.; Nicoleta, B.F. Production evolution for the main agricultural crops from the central Banat area under the influence of the main pathogens and pedoclimatic conditions. Int. Multidiscip. Sci. GeoConf. SGEM 2018, 18, 347–355. [Google Scholar]

- Ulea, E.; Florea, A.M.; Gafencu, A.M.; Lipșa, F.D. Alternaria head rot on sunflower in the NE region of Romania. Agron. Ser. Sci. Res. 2024, 67, 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Gulzar, Y.; Ünal, Z.; Aktaş, H.; Mir, M.S. Harnessing the Power of Transfer Learning in Sunflower Disease Detection: A Comparative Study. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahni, R.K.; Kumar, S.P.; Thorat, D.; Rajwade, Y.; Jyoti, B.; Ranjan, J.; Anand, R. Drone Spraying System for Efficient Agrochemical Application in Precision Agriculture. In Applications of Computer Vision and Drone Technology in Agriculture 4.0; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.P.; Subeesh, A.; Jyoti, B.; Mehta, C.R. Applications of drones in smart agriculture. In Smart Agriculture for Developing Nations: Status, Perspectives and Challenges; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Easy Access Rules for Unmanned Aircraft Systems (Regulations (EU) 2019/947 and 2019/945). EASA. Available online: https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/document-library/easy-access-rules/easy-access-rules-unmanned-aircraft-systems-regulations-eu (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Romanian CAA. www.caa.ro. Available online: https://www.caa.ro/ro/pages/drone (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Satellites and Drones Support in Addressing Sustainability Challenges in Agriculture. Available online: https://monitor-industrial-ecosystems.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2021-05/Leaflet%20Satellites%20and%20drones%20for%20less%20intensive%20farming%20and%20arable%20crops.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- 2022-006-GO DRONE-Optimization of the Application of Phytosanitary Products Through the Combination of Artificial Intelligence and the Use of Drones|EU CAP Network. Europa.eu. Available online: https://eu-cap-network.ec.europa.eu/projects/2022-006-go-drone-optimization-application-phytosanitary-products-through-combination_en (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Debaeke, P.; Estragnat, A.; Reau, R. Influence of Crop Management on Sunflower Stem Canker (Diaporthe helianthi). Agronomie 2003, 23, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debaeke, P.; Moinard, J. Effect of Crop Management on Epidemics of Phomopsis Stem Canker (Diaporthe helianthi) for Susceptible and Tolerant Sunflower Cultivars. Field Crops Res. 2010, 115, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herd, G.W.; Phillips, L. Control of Seed-Borne Sclerotinia sclerotiorum by Fungicidal Treatment of Sunflower Seed. Plant Pathol. 1988, 37, 202–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debaeke, P.; Pérès, A. Influence of Sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) Crop Management on Phoma Black Stem (Phoma macdonaldii Boerema). Crop Prot. 2003, 22, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudchenko, V.; Markovska, O.; Sydiakina, O. Determination of the Effectiveness of Fungicide Protection Systems as a Reserve for Sustainable Sunflower Production in South of Ukraine. Technol. Audit Prod. Reserves 2025, 1, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattarovich, S.B.; Normamadovich, R.U.; Kakhramonovich, K.U.; Mirodilovich, A.M. Fungal diseases of sunflower and measures against them. PalArch’s J. Archaeol. Egypt/Egyptol. 2020, 17, 3268–3279. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, A.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Alami, M.M.; Alrefaei, A.F.; Abbas, Q.; Naqvi, S.A.H.; Rao, M.J.; Mosa, W.F.A.; Abbas, Q.; et al. Drones in Plant Disease Assessment, Efficient Monitoring, and Detection: A Way Forward to Smart Agriculture. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, R.; Catal, C.; Kassahun, A. Plant Disease Detection Using Drones in Precision Agriculture. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 1663–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimani, H.; El Mhamdi, J.; Jilbab, A. Drone-assisted plant disease identification using artificial intelligence: A critical review. Int. J. Comput. Digit. Syst. 2023, 14, 10433–10446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Lan, Y.; Qi, H.; Chen, P.; Hewitt, A.; Han, Y. Field Evaluation of an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Sprayer: Effect of Spray Volume on Deposition and the Control of Pests and Disease in Wheat. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 1546–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jang, H.-R.; Choi, S.; Park, S.; Choi, J.; Choi, H.; Park, S.-W.; An, W.; Hong, S.-W.; Sang, H. Assessment of Fungicide-Based Control of Sheath Blight Using Mobile Spraying Equipment. Front. Agron. 2025, 7, 1687036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, R.M.; Adegas, F.S.; Roggia, S. Drone spraying of fungicides to control Asian soybean rust. J. Agric. Sci. Res. 2025, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Xue, X.; Zhang, S.; Gu, W.; Wang, B. Droplet Deposition and Efficiency of Fungicides Sprayed with Small UAV against Wheat Powdery Mildew. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2018, 11, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Chen, L.; Pan, F.; Deng, Y.; Ding, C.; Liao, M.; Su, X.; Cao, H. Application Method Affects Pesticide Efficiency and Effectiveness in Wheat Fields. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 76, 1256–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, L.d.S.; Grigolo, C.R.; Pertille, R.H.; Modolo, A.J.; Campos, J.R.d.R.; Elias, A.R.; Citadin, I. Aerial Spraying for Downy Mildew Control in Grapevines Using a Remotely Piloted Aircraft. Acta Scientiarum. Agron. 2024, 46, e66613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, B.; Tiwari, P.K.; Verma, S.; Netam, K.; Sahu, B. Evaluation of Nutrient Application and Drones Sprayed Pesticides (Fungicides and Insecticides) on the Disease Severity of Major Diseases of Paddy. Microbiol. Res. J. Int. 2025, 35, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, C.; Wang, G.; Wang, H.; Wu, L.; Song, C.; Hussain, M.; Wang, H.; Lan, Y. Assessing the Efficiency of UAV for Pesticide Application in Disease Management of Peanut Crop. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 4505–4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Vitória, E.L.; Krohling, C.A.; Borges, F.R.P.; Ribeiro, L.F.O.; Ribeiro, M.E.A.; Chen, P.; Lan, Y.; Wang, S.; e Moraes, H.M.F.; Júnior, M.R.F. Efficiency of Fungicide Application an Using an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle and Pneumatic Sprayer for Control of Hemileia vastatrix and Cercospora coffeicola in Mountain Coffee Crops. Agronomy 2023, 13, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaga García, S.N.; Meza Cabrera, W.G.; Painii Cabrera, V.F. Uso de Drones Para El Control de Sigatoka Negra (Mycosphaerella fijiensis) Vinces, Ecuador. ECOAgropecu. Rev. Científica Ecológica Agropecu 2024, 1, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiri, R.; Rizan, N.; Balasundram, S.K.; Shahbazi, A.B.; Abdul-Hamid, H. Application of Digital Technologies for Ensuring Agricultural Productivity. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Pramod Pawar, P.; Kumar Meesala, M.; Kumar Pareek, P.; Reddy Addula, S.; Shwetha, K.S. Smart Agriculture in the Era of Big Data: IoT-Assisted Pest Forecasting and Resource Optimization for Sustainable Farming. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Integrated Intelligence and Communication Systems (ICIICS), Kalaburagi, India, 22–23 November 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Gupta, D.; Joshi, M.; Yadav, K.; Nayak, S.; Kumar, M.; Nayak, K.; Gulaiya, S.; Rajpoot, A.S. Application of Drones Technology in Agriculture: A Modern Approach. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2024, 30, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, F.; Noel, A.S. Perception of Farmers with Reference to Drones for Pesticides Spray at Kurukshetra District of Haryana, India. Asian J. Adv. Agric. Res. 2023, 22, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variant | Equipment | Spraying Rate Volume (L/ha) | Products Used | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D200 | DJI Agras T50 | 200 | Architect 1 L/ha + Turbo 0.6 kg/ha | Simulation of the ground application of one treatment |

| D200 + D10 | 200 (T1) + 10 (T2) | Simulation of the ground application + second treatment ULV | ||

| D10 × 2 | 10 | ULV (2 treatments) | ||

| D30 × 2 | 30 | LV (2 treatments) | ||

| D100 × 2 | 100 | MV (2 treatments) | ||

| Control | - | - | - | No fungicide treatment |

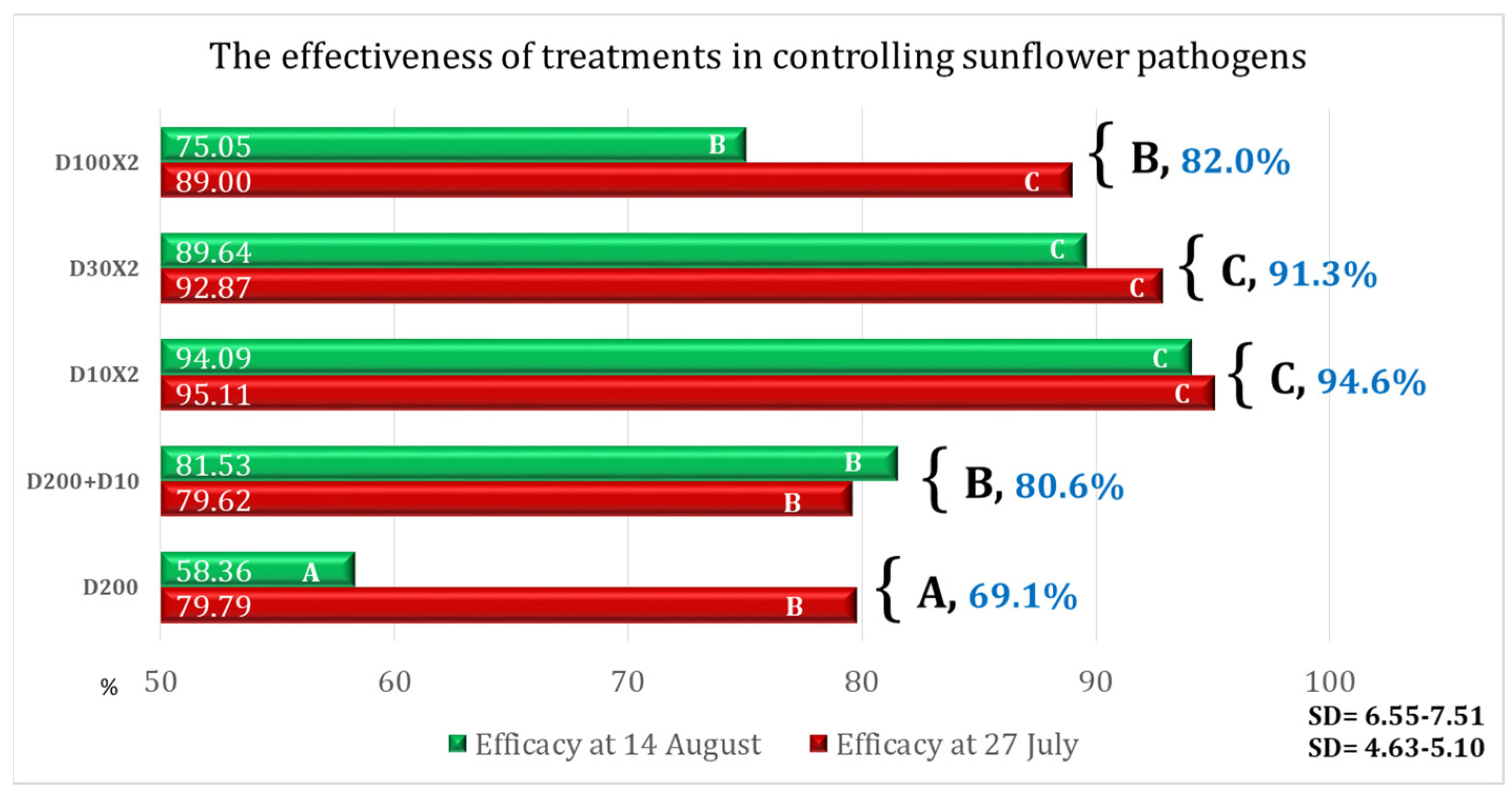

| Variant | AD% | Efficacy% | Time for Application Per ha |

|---|---|---|---|

| D200 | 5.82 | 58.36 | 00 h 12 m 30 s (one application) |

| D200 + D10 | 2.58 | 81.53 | 00 h 15 m 09 s (two applications) |

| D10 × 2 | 0.83 | 94.09 | 00 h 05 m 18 s (two applications) |

| D30 × 2 | 1.45 | 89.64 | 00 h 05 m 18 s (two applications) |

| D100 × 2 | 3.49 | 75.05 | 00 h 12 m 30 s (two applications) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Șerban, M.I.; Grad-Rusu, E.; Florian, T.; Grad, M.; Florian, V.C. Efficacy of Drone-Applied Fungicide Treatments in Control of Sunflower Diseases. Drones 2026, 10, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010033

Șerban MI, Grad-Rusu E, Florian T, Grad M, Florian VC. Efficacy of Drone-Applied Fungicide Treatments in Control of Sunflower Diseases. Drones. 2026; 10(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleȘerban, Mădălina Ioana, Elena Grad-Rusu, Teodora Florian, Marius Grad, and Vasile Constantin Florian. 2026. "Efficacy of Drone-Applied Fungicide Treatments in Control of Sunflower Diseases" Drones 10, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010033

APA StyleȘerban, M. I., Grad-Rusu, E., Florian, T., Grad, M., & Florian, V. C. (2026). Efficacy of Drone-Applied Fungicide Treatments in Control of Sunflower Diseases. Drones, 10(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010033